CHAPTER 12

Put the Pedal to the Metal

The weakness of wage growth has continued to be a surprise to policymakers. At a press conference following the rate increase decision at the FOMC meeting on June 13, 2018, Fed chairman Jay Powell said, “We had anticipated, and many people have anticipated that wages—that in a world where we’re hearing lots and lots about labor shortages—everywhere we go now, we hear about labor shortages, but where is the wage reaction? So, it’s a bit of a puzzle. I wouldn’t say it’s a mystery, but it’s a bit of a puzzle. And one of the things is, you will see pretty much people who want to get jobs—not everybody—but people who want to get jobs, many of them will be able to get jobs. You will see wages go up.”1

Hope springs eternal. The projections from the September 2018 meeting showed that the FOMC members thought that the long-run value for unemployment, its natural rate, is in the range of 4.0–4.6 percent.2 With the unemployment rate at 3.7 percent there surely, according to the FOMC, should have been roaring wage pressure, and fear of a wage explosion is one of the main reasons the Fed raised rates. The fact that there is little sign of wage growth picking up is neither a puzzle nor a mystery. The FOMC appears to have underestimated the amount of labor market slack.

Policymakers at the start of 2019 seem just as out of touch with what is going on outside the big cities as they were as the Great Recession was nearing. Too few of them have much idea that the NAIRU has likely fallen and or know why wage growth isn’t skyrocketing. I recall having the same discussions at the MPC in June 2008. The FOMC raised rates based on no data. As I showed in chapter 5, the puzzle is largely solved; elevated levels of underemployment continue to push down on wages. Turning points are hard to call. Downside risks abound.

I went to talk to the Guardian editorial board and when we were done they presented me with the original of the cartoon in figure 12.1 that appeared on December 11, 2008. A “leaving do” is a farewell party, which I didn’t have when I left the Bank of England. I voted to cut rates at every meeting from October 2007 through my last meeting in May 2008. Mervyn King was glad to see the back of me.

The economics of walking about suggests that economies are ticking along, although at a relatively slow pace. The United States looks to be the best of them. The concern is that a trade war may slow global trade. The introduction of tariffs in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in the 1930s led to retaliation and disastrous consequences. Some progress has been made between Canada, the United States, and Mexico in the signing of the USMCA, which updates NAFTA. Progress was also apparently made at the G20 summit in Argentina when Trump and Xi agreed to a trade war ceasefire with a deal to suspend new trade tariffs. Trump will leave tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese imports at 10 percent at the beginning of the new year, agreeing to not raise them to 25 percent “at this time,” the White House said in a statement. “China will agree to purchase a not yet agreed upon, but very substantial, amount of agricultural, energy, industrial, and other product from the United States to reduce the trade imbalance between our two countries,” it said. “China has agreed to start purchasing agricultural product from our farmers immediately.”3 At the start of 2019 trade discussions between the United States and China were continuing.

The New York Times has reported that even the White House’s own analysis from the President’s Council of Economic Advisers has found that tariffs will hurt growth, as officials continue to insist otherwise!4 You couldn’t make this up. Then Larry Kudlow, Donald Trump’s chief economic advisor, accused Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau of undermining the United States and its allies with comments he made at the G7 summit. Peter Navarro, a trade advisor to President Donald Trump, said, “There’s a special place in hell for any foreign leader that engages in bad faith diplomacy with President Donald J. Trump and then tries to stab him in the back on the way out the door.” Analogously, in February 2019 European Council President Donald Tusk warned of a “special place in hell” for those who pushed for Brexit “without even a sketch of a plan.”5

Figure 12.1. “David Blanchflower to step down from Bank of England next year.” This cartoon by the famous British political/economic cartoonist Kipper Williams appeared in the Guardian on December 11, 2008, just after I announced I would not be looking to renew my three-year term. For the uninitiated a “leaving do” is British slang for a farewell party. In the end I voted to cut rates at every meeting from October 2007 through March 2009, mostly alone, and after that, once the bank rate hit 0.5 percent, I voted for asset purchases in April and May 2009 of £125 billion, so I was the cutter in chief! I did not have a leaving do; I was offered one but declined. I wanted to get out of there as soon as I could. Prime Minister Gordon Brown rang me later and apologized for appointing me “to that awful job.” Source: Kipper Williams, The Guardian, December 11, 2008.

Trump imposed tariffs such that every foreign company that sends steel and aluminum to the United States, including Canadian firms, would be forced to pay a 25 percent tariff on steel and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum.6 Canada and other allies such as the UK apparently are national security threats to the United States. Then Trump imposed tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods, prompting a swift response from the Chinese and kicked off an unpredictable trade war. Farmers have been complaining that they are being hurt irreparably by the imposition of tariffs in retaliation for the tariffs being imposed on China and our allies. More than half of America’s soybean exports go to China. The Trump administration is now proposing to employ $12 billion in emergency funds from the Department of Agriculture to subsidize losses of U.S. farmers resulting from the imposition of retaliatory tariffs, specifically on soybeans, pork, sorghum, corn, wheat, cotton, and dairy products, just to name a few. The administration is employing the Depression-era facility called the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), which was established to fund payments to farmers as part of a three-part program that includes direct assistance, the purchase of surplus agricultural products, and trade promotion of agricultural products.7 U.S. exports of soybean to China were down 98 percent in 2018.8

Tariffs have already hurt Harley-Davidson’s earnings; tariffs are expected to cost them $45–55 million in 2018. General Motors says commodity inflation pushed their costs up $300 million in its latest quarter from a year ago. Whirlpool says its costs will rise about $350 million in 2018. Coca-Cola hiked up prices in response to an increase in costs from freight to the metal used in Coke cans. Ford estimates that the tariffs will cost an estimated $500–600 million in 2018.9 Oh, what a mess. Trade wars loom.

Some of the boost to the economy from the tax cuts implemented by the GOP will likely be negated by the slowing of the economy from the new tariffs. How much remains unclear. It is notable that the tax cuts are widely unpopular, which is why Republicans did not run on them in the November 2018 midterm elections. A poll from Monmouth University found 34 percent of adults approve of the tax cut now, a slide from January when adults were about evenly split between approving and disapproving.10 In June 2018 in a POLITICO/Morning Consult poll, 37 percent of registered voters said they supported the tax-cut law, down from 44 percent in an April poll.11

U.S. GDP growth for 2018 Q2 came in at a frisky 4.1 percent annualized versus an upwardly revised 2.2 percent in Q1. Newt Gingrich argued that President Trump “has once again achieved the impossible.”12 Trump claimed that “Americans are enjoying the best economy ever.” Josh Boak and Christopher Rugaber from the AP noted that was not true: “His boast of record achievements on the economy and jobs ignores the Roaring Twenties, the war-time boom in the 1940s, the 1990s expansion and other times when unemployment was lower than now, economic growth was higher than now, or brisk productivity made the U.S. the world’s economic powerhouse.”13

The advance estimate data release for GDP growth in 2018 Q3 was published on October 29, 2018, just before the midterm elections on November 6, and it was good, but lower at 3.5 percent annualized rate. The U.S. economy is expected to slow from here. In its January 2019 World Economic Outlook Update the IMF estimated growth of 2.9 percent in 2018 and forecast 2.5 percent in 2019 and 1.8 percent in 2020.

Turning back now to the UK, Brexit has consistently ranked at or near the top of the list of the risks identified in the Deloitte survey of UK chief financial officers. In the Bank of England’s own quarterly Decision Makers’ Panel, around 40 percent of firms consistently identify Brexit as a major source of uncertainty, with less than 20 percent viewing it as unimportant. The MPC has called Brexit the biggest downside risk to the UK economy.

Support for Brexit appears to be hemorrhaging in the UK. A poll taken by Sky Data in July 2018 found that fully two-thirds of the public—including a majority of Leave voters—think the outcome of Brexit negotiations will be bad for Britain.14 Most people would like to see a referendum asking for voters to choose between the deal suggested by the government, no deal, and remaining in the EU. Seventy-eight percent of respondents said they thought the government was doing a bad job negotiating Brexit. Thirty-one percent said they thought Brexit would be good for them personally compared with 42 percent saying it would be bad. Fifty-two percent said it would be bad for the economy while 35 percent said it would be good. Reports that the government is stockpiling food and medicines in case of a no-deal Brexit likely haven’t helped. The Washington Post reported on the difficulty British farmers are having finding British applicants to pick crops—out of 10,000 applicants, two were British.15

I was on Bloomberg TV on November 27, 2018, with Bloomberg’s Stephanie Flanders talking about the release that was expected any time from the Bank of England on its evaluation of the economic consequences of an abrupt Brexit. While we were live the news of the analysis came over the wires. It was shocking, showing that in the worst-case, “disorderly” apocalyptic scenario the bank expected that output would fall around 8 percent, the unemployment rate would rise to 7.5 percent, and house prices would drop 30 percent by the end of 2023.16 In addition, under the disorderly scenario, the pound would fall 25 percent and be close to dollar parity, inflation would rise because of the reduction in supply, and net migration would decline to around minus 100,000. In response the bank argued that the MPC would respond by raising the bank rate from the current 0.75 percent to 5.5 percent.

My immediate reaction was, “When they talk about a huge drop in output and the Bank of England is going to raise rates to 5 percent MPC members will be thinking about a huge drop in output, which might well not be an argument to raise rates.”17 That would make matters much worse for ordinary people. I would be voting for rate cuts in those circumstances. Even Paul Krugman tweeted that the analysis made no sense: “I’m anti-Brexit, and have no doubt that it will make Britain poorer. And the BoE could be right about the magnitude. But they’ve really gone pretty far out on a limb here.”

The Brexiters soon turned on Governor Carney. Jacob Rees-Mogg said that Carney, whom he had dubbed the “high priest of project fear,” was a “second-tier Canadian politician” who “failed” to get a job at home. Carney spent the next few days trying to defend the Bank of England’s independence. I have some sympathy with ex-MPC member Andrew Sentance’s view that “the Bank of England is undermining its credibility and independence by giving such prominence to these extreme scenarios and forecasts.” Too much belief in models and too little common sense. Another disaster for the Bank of England. A week is a long time in economics.

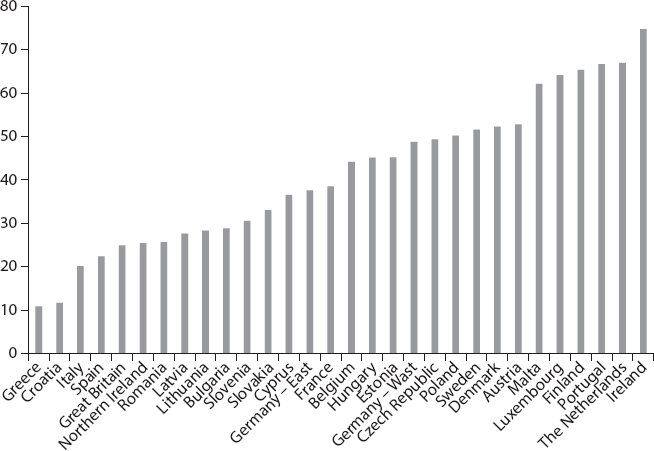

The latest polling in the United States on the direction the country is going is summarized by Real Clear Politics (RCP).18 At the beginning of February 2019 RCP reported that the average of the last twelve polls showed that 33.5 percent of Americans said the country was headed in the right direction versus 58.8 percent opposed. A Eurobarometer survey asked respondents in EU countries in November 2017 whether they thought their country was going in the right direction, the wrong direction, or neither. The proportion saying in the right direction was as reported in figure 12.2. Over two-thirds of respondents are supportive in Portugal, while Greece (20.1%), Croatia (8.9%), Italy (10.7%), and Spain (15.8%) are least likely to report that way (May 2018 unemployment rates are in parentheses). Only a quarter in the UK thought positively about the economy at the end of 2017.

Figure 12.2. Percent saying the country is going in the right direction, EU28, 2017

The question is, how far away is a recession? George Magnus pointed out that the current expansion in the United States, from the last trough in activity in June 2009, has now overtaken the expansion from February 1961 to December 1969 to be the second longest ever.19 Assuming it keeps going until June 2019, which it may not, it will become the longest recovery ever, overtaking the 120-month expansion from 1991 to 2001. The average length of the twelve expansions since 1945, Magnus notes, has been 58.4 months and in the three cycles since 1991 the average was 95 months. The prospect of the economy slowing before the November 2020 presidential election, in my view, is likely better than 60/40: recoveries do not go on forever.20 U.S. recoveries usually end because the Federal Reserve raises rates too soon, as they have continued to do in 2018.

We need to ask ourselves what now, given that central banks have fewer arrows in their economic quivers than they had when the Great Recession hit? In 2008 interest rates were around 5 percent and there was room to cut them to zero and even below. Right now central banks do not have that much room to maneuver. Congress is unlikely to act swiftly in the face of any downturn, and similarly in the UK, which is preoccupied with Brexit. The risks look to be to the downside. The left-behinds look set to continue to be left behind. Nobody has apologized for messing up.

Don’t Let Things Drift

Tom Clark and Anthony Heath (2014) in their impressive and fascinating book documented who had been hurt and how by the Great Recession. The modern world, they argue, has been hit by an economic tornado that was not quite 1933; there has been no General Strike and no Jarrow March.21 The fifty Brexit supporters marching from Sunderland to London in 2019, led by Nigel Farage, who left after a few miles, don’t count. The book’s theme is that the deep societal problems laid bare by the recession—problems of anxiety and isolation—were always more structural than cyclical. A rich country, they argue, should be perfectly able to endure getting a bit poorer during a passing downturn. The UK, they suggest, and I agree, didn’t run into all the dislocation they uncovered because the crisis suddenly created frailty in downtrodden communities. It simply exposed underlying problems with deep roots in the long decades before, when inequality had run out of control. Clark and Heath also note that what happened post-recession had deep roots in the past, which has broad applicability across advanced countries: “It would be going too far to claim that all the real damage was done before the recession and was merely revealed by the downturn: we have seen that the purely recessionary surge in unemployment had profound and unhappy consequences for well-being. But the wider mood of anxiety that defines those hard times undoubtedly has deeper roots” (2014, 221–22).

As I noted in my review of their book, its theme is that “the deep societal problems laid bare by the recession—problems of anxiety and isolation—were always more structural than cyclical. A rich country, they argue, should be perfectly able to endure getting a bit poorer, during a passing downturn. The UK, they argue, and I agree, didn’t run into all the dislocation they uncovered because the crisis suddenly created frailty in downtrodden communities. It simply exposed underlying problems with deep roots in the long decades before, when inequality had run out of control” (2015a, 579). Flickers of “depressionary social psychology,” Clark and Heath argue, applied in the 1930s when cigarettes and cinema tickets were about the only goods with rising sales. They noted that during the Great Recession Britons developed a taste for more sugary and fattier foods. Shoppers switched to supermarket brands, drinking less in the pub and cooking with leftovers, doing more home cooking, more mending of clothes instead of buying new ones, and growing their own vegetables. Clark and Heath also provided evidence that people substituted processed foods for fruit and vegetables, resulting in a decrease in the nutritional quality of calories consumed.22

Clark and Heath (2014) warn that we should not underestimate the damage that hard times can do because there can be an enduring cost to letting things drift. Jobs, they argue, are at the heart of resolving hard times. These are harsh times, indeed. But they didn’t have to be.

Le Pen, Brexit, and Trump provided alternative narratives for those who were left behind by economic change. They were told it wasn’t their fault. These were the people who were bypassed by the march of progress, globalization, and technology. The elites told them they were ignorant, racist bigots. They needed to get with the program and to get with gay marriage and affirmative action and Black Lives Matter. Arguments in the United States over LGBTQ bathrooms were the last straw. Everyone in their town thought Hillary Clinton was a crook.

It was the fault of immigrants, job-killing regulations, Muslims, trade deals, TPP, NAFTA, and the EPA. The mainstream media, what Rush Limbaugh calls the “drive-by media,” and their fake news were culpable. It was the European Union’s, China’s, and Mexico’s fault and especially it was immigrants who were rapists, robbers, thugs, and different. Building the wall was a great way of sticking it in the face of Hillary and her liberal entourage. It was about sovereignty in the UK, taking back power from Europe, but mostly it was about blaming everyone else for the hurt that was deep inside. Making America Great Again meant bringing back high-paying union jobs to coal and steel towns. Trump supporters hadn’t been abroad and had no inclination to change that. Most had no idea where Paris was even if they were told it wasn’t Paris, Texas.

The left-behinds resented being thought of as stupid. Populism was a way out. It meant they could shift the blame. They love it that Trump irritates the left. They dislike outsiders. They hate it that the left, according to Bill O’Reilly and Fox News, has been trying to abolish Christmas and make everyone say “happy holidays.” Political correctness is anathema to rural America. Trump told them that Obama was a Kenyan-born Muslim and an illegitimate black president, and they believed him and many still do. They believe in creationism and never went to the Harvard Natural History Museum, which in the entrance says if you believe in creationism don’t enter. They built their own $100 million replica of Noah’s ark in Kentucky instead.23 Trump gave flyover America a chance to get their own back on the exam-taking classes. That made them feel better. This was deeply cultural.

Refugees who might turn into terrorists at the drop of a hat represented a growing threat, even though the chances of an American being killed by a terrorist over the last decade were lower than being hit by a falling piano. It also turned out that the probability of being killed by a refugee terrorist was less than that of being killed by a shark, an asteroid, an earthquake, or a tornado; choking on food; or being stung by hornets, wasps, or bees.24

Brexit meant bringing back prosperity to declining coal, steel, and seaside towns. Boris Johnson, who became UK foreign secretary and recently resigned over Theresa May’s Chequers Brexit plan, complained about EU laws that determined the power of vacuum cleaners and what shape bananas had to be; he said such policies were “crazy.”25 Sovereignty meant that you could have any shape banana you want. Brexit was about holding your head up and not being beholden to others. Many yearn for the days of empire and long-lost glories.

I keep asking myself how Trump and the Brexiters could promise so much with so little chance of delivering. There was no chance on God’s green earth that a wall was going to be built along the entire southern border. There was even less chance that Mexico was going to pay a dime toward it. As Eugene Robinson noted, “The idea of a 2,000-mile, 30-foot-high, ‘big, beautiful’ wall along the entire border was always more of a revenge fantasy than an actual proposal.”26 Republican congressmen and senators representing districts along the border oppose the wall. Representative Will Hurd (R-Texas), whose district includes 820 miles along the Mexican border, actively opposes its construction.

There was no way Donald Trump was going to pay off the debt in four or was it eight years? There was zero chance they were ever going to “lock her up.” I was struck by the details of an ABC/Washington Post poll taken on April 17–20, 2017, that asked: “Do you (regret supporting Trump) or do you (think that supporting Trump was the right thing to do) in that election?” Only 2 percent said they regretted supporting Trump. Seventy-seven percent of Republicans said that Trump is in touch with the concerns of most people in the United States today; 65 percent of Republican voters said that he had done better than they expected in his first 100 days; and 80 percent said he had “done a great deal.”27 Trump was right when he said he could walk down Fifth Avenue and shoot someone and wouldn’t lose support. He changed the narrative.

I realized on reading this survey that it didn’t matter to his supporters if Trump was unable to create lots of jobs or build a wall. It didn’t matter that he didn’t have a plan to beat ISIS. The swamp wasn’t going to drain and wouldn’t go away readily but DJT was on the job. All would be forgiven as it was clear he had tried but it was all the fault of the Democrats, the drive-by media, and the elites. There are plenty of excuses. It doesn’t matter that Trump hadn’t managed to pass any of the ten pieces of legislation he had promised he would pass in his first one hundred days. This was all about not feeling stupid. Now there were plenty of people to blame—the left-wing fake media and the demonstrators who were all paid by George Soros despite there being no evidence to support such a contention.

In July 2018 nearly nine out of ten Republicans supported Trump. In a new article Montagnes, Peskowita, and McCrain (forthcoming) argue that people who identify as Republican may stop doing so if they disapprove of Trump. There seems to be some evidence in support of this thesis. There has been a decline of around 4 percentage points in GOP identification since the 2016 election in various polls from 28–29 percent of voters identifying as Republican to 25–26 percent.

Polling from NBC/Marris in July 2018 indicated that three key battleground states are worried about Trump’s prospects of reelection in 2020. In Michigan, which Trump won by 11,000 votes, 36 percent of voters approve of Trump’s job performance while 54 percent disapprove. In Wisconsin, which Trump won by 23,000 votes, 3 percent approve with 52 percent disapproving. In Minnesota, which Trump narrowly lost by 1.5 percentage points, his rating is 3 percent for, 51 percent against.28

It didn’t matter that there was no £350 million a week to distribute to the NHS as the Brexiters claimed. The fact that the post-Brexit economy wasn’t working well was the fault of the “Remoaners.” It was the unreasonable behavior of the rest of the EU, especially Spain, which wanted to take Gibraltar if Brexit happened, just as the Argentinians—the Argies—tried to snatch the Falklands.29 Ex-leader of the Tory Party Lord Michael Howard suggested that Prime Minister May should send out an armada: “Thirty-five years ago, this week, another woman prime minister sent a taskforce halfway across the world to defend the freedom of another small group of British people against another Spanish-speaking country, and I’m absolutely certain that our current prime minister will show the same resolve in standing by the people of Gibraltar.” And Defence Secretary Sir Michael Fallon said the UK was prepared to go “all the way” to keep the Rock out of Spain’s clutches.30 Good Lord.

A YouGov poll taken in the UK on January 16, 2019, asked, “If there were a referendum today on whether or not the UK should remain a member of the EU, how would you vote?” Fifty-six percent said remain, 44 percent said leave. They were also asked, “Thinking about Brexit, would you now support or oppose a public vote on Britain’s future relationship with the rest of the European Union?” Fifty-six percent supported and 43 percent opposed.

We Were Never All in This Together

On October 6, 2009, then Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne gave a speech to the Tory Party Conference outlining what austerity would look like. Seven months later he was chancellor and the cuts began. His broken promises still haunt me. Seven times in that speech he claimed, “We are all in this together”: “I want my children to think that our generation paid off its debts, valued its savers, rewarded responsibility, invested in their future. And because I want it for my children, I want it for your children too. I want it for everyone’s children. Because we are all in this together.”31 We weren’t by a long shot.

At his 2010 spending review Chancellor Osborne insisted that those with the broadest shoulders should bear the greatest burden. The combined impact of direct tax and cash transfer changes was mostly regressive, moving income from poorer households to those who were better-off. After 2010–11, real spending on pensioners rose, for example, but it fell for children.

On April 19, 2017, George Osborne, the architect of austerity, accepted the job as editor of the Evening Standard and announced he would not stand as an MP in the June 2017 election. My friend, the always excellent Polly Toynbee, made clear what his legacy is:

Even as he said “all in it together” he cast the cruelest cuts on those with least. He set about denigrating disabled people as no other Tory government had done before, sending out stories of cheats running marathons to cover blatant, knowing cruelty…. Devious, malevolent and apparently indifferent to the consequences for millions of lives, Osborne has deliberately laid waste to the social security system. But far worse, he has demolished trust in it, undermining the idea that the state should support the weak, subsidize low-earners in housing they can afford or care for the sick. The fabric could be restored by future governments of good will but rebuilding lost public trust will be far harder.32

“All in it together” was a con.

The deep underlying causes of helplessness and hopelessness have not been addressed. Isolated people in fractured communities are susceptible to messages of hope. It is clear, though, as Case and Deaton (2017b) argue, that Americans are dying deaths of despair. They conclude that “the story is rooted in the labor market.” In private communication Angus Deaton told me, “We didn’t originally think so, but it really does look like the deteriorating labor market is the key, or at least one of them.” Austerity along with attempts to balance budgets and cut entitlements in a recession made matters worse.

Trust and the Spreading of Hate

It is clear that trust, particularly in institutions, is waning, and there is a special distrust of elites.

Recall, of course, that the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles imposed on Germany after World War I led to a right-wing populist uprising that brought Hitler to power. In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes warned in 1920 of the consequences of the hardship that was being imposed.

Economic privation proceeds by easy stages, and so long as men suffer it patiently the outside world cares very little. Physical efficiency and resistance to disease slowly diminish, but life proceeds somehow, until the limit of human endurance is reached at last and counsels of despair and madness stir the sufferers from the lethargy which precedes the crisis. The man shakes himself, and the bonds of custom are loosed. The power of ideas is sovereign, and he listens to whatever instruction of hope, illusion, or revenge is carried to them in the air…. But who can say how much is endurable, or in what direction men will seek at last to escape from their misfortunes? (1920, 250–51)

As Robert Putnam in his insightful book Bowling Alone revealed, there has been “a steady withering of America’s community bonds.” The more integrated we are with our communities, Putnam noted, the less likely we are to experience colds, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, depression, and premature death of all sorts (2000, 327).

Social cohesion matters for health. Socially isolated people are more likely to smoke, drink, overeat, and engage in other health-damaging behaviors. As a rough rule of thumb, Putnam notes, if you belong to no groups but decide to join one, you cut your risk of dying over the next year in half (2000, 331). Social support, Putnam notes, also lessens depression.

Beginning in the late 1960s, Putnam and his coauthors write in Better Together, Americans began to “join less, trust less, give less, vote less and schmooze less” (2003, 4). They go on to note that the more neighbors who know one another by name, the fewer crimes a neighborhood as a whole will suffer. A child born in a state whose residents volunteer, vote, and spend time with friends is less likely to be born underweight, less likely to drop out of school, and less likely to kill or be killed than the same child—no richer or poorer—born in another state whose residents do not (2003, 269). Social ties bind. Putnam notes that the longer a kid lives in a bad neighborhood the worse the effects (2015, 217). We need to restore trust.

The European Social Survey shows that there has been a big decline in the UK in the proportion of people who meet socially with friends, relatives, or work colleagues at least once a week. This is down from 71 percent in 2002 to 61 percent in 2014.33 In both the UK and the United States what Clark and Heath (2014) call the “gradual evolution of disadvantage” has taken place; the weak were hit more than the strong. In part as a matter of choice, politicians imposed austerity that hurt those at the bottom of the income distribution. I really can’t see any other purpose; shrinking the state would inevitably hurt the poor. As I said in my review of their book in 2015, “The worst crisis in our lives is far from over; the concern is that things are soon going to get worse. These are certainly unusual times and harsh times. Something is deeply wrong. People are struggling to make ends meet. Politicians are making it harder for them. The discourse must change” (2015a, 582).

A cohesive society is one where citizens have confidence in others and public institutions. Today, trust is on the slide. Trust may affect economic performance, and policies can affect trust and well-being.34 In the 1972 U.S. General Social Survey (GSS) around half of respondents said that “most people can be trusted.” By 2016 only a third concurred. The OECD’s “Society at a Glance” (OECD 2016) reports on trust in others by country. About 36 percent of interviewees expressed interpersonal trust. In Nordic countries over 60 percent of interviewees trust each other compared to less than 13 percent in Chile, Mexico, and Turkey. The UK and the United States are in the middle of the pack, with Germany higher and France lower.

An AP-GfK poll conducted in October 2013 found that Americans are suspicious of each other in everyday encounters.35 Less than one-third expressed a lot of trust in clerks who swipe their credit cards, drivers on the road, or people they meet when traveling. Pew found that 19 percent of Millennials say most people can be trusted, compared with 31 percent of Gen Xers, 37 percent of Silents, and 40 percent of Boomers.36 Just half of Americans (52%) say they trust all or most of their neighbors, while a similar share (48%) say they trust some or none of their neighbors, according to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey. Americans today are less likely to spend social evenings with their neighbors than in the past. In 1974, 61 percent of Americans said they would spend a social evening with someone in their neighborhood at least once a month, while 39 percent said they would do so less than once a month or not at all, according to the GSS. In 2014, fewer than half (46%) said they spend social evenings with their neighbors at least monthly, compared with 54 percent who do not.37

Trust in U.S. institutions slumped during Trump’s first year in office.38 According to the 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, trust in the United States has suffered the largest-ever-recorded drop in the survey’s history among the general population. Trust among the general population fell nine points to 43 percent, placing it in the lower quarter of the 28-country Trust Index. Trust among the informed public in the United States imploded, plunging 23 points to 45 percent, making it now the lowest of the 28 countries surveyed, below Russia and South Africa. The collapse of trust in the United States is driven by a staggering lack of faith in government, which fell 14 points to 33 percent among the general population, and 30 points to 33 percent among the informed public. The remaining institutions of business, media, and NGOs also experienced declines of 10 to 20 points. Richard Edelman, president and CEO of Edelman, said, “The root cause of this fall is the lack of objective facts and rational discourse.”39

The finding of a decline in trust within the United States follows a report by Gallup that showed median approval of U.S. leadership across 134 countries fell from 48 to 30 percent in 2017.40 Big losses of 10 percentage points or more occurred in 65 countries, including many U.S. allies. Portugal, Belgium, Norway, and Canada led the worldwide declines with approval dropping by at least 40 percentage points. In the UK only 33 percent approved of the performance of the leadership of the United States; the comparable values in other countries were 25 percent in France, 22 percent in Germany, and 20 percent in Canada.

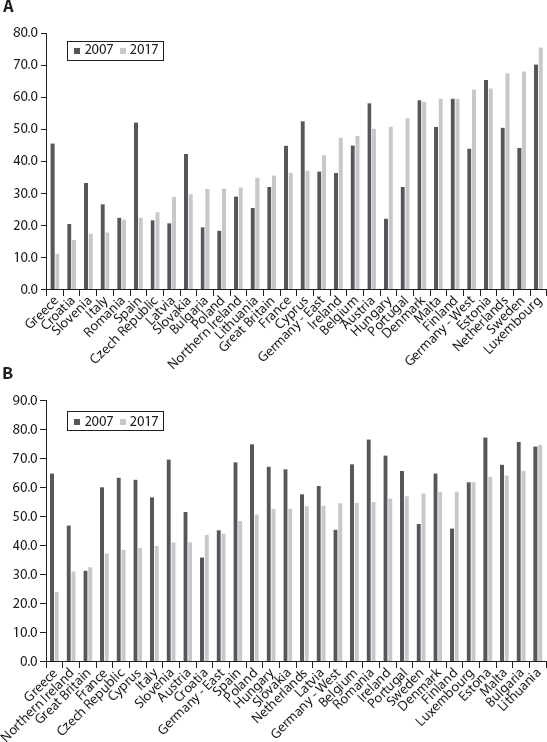

In a Eurobarometer survey taken in November 2017, respondents were asked, “We would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions—national government and the European Union. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?” The results by country are set out in figure 12.3A for the two years (2007 and 2017) for views on trust of national government, ranked by 2017 levels, which show big falls in Greece, Spain, and France and rises elsewhere, including Portugal and Hungary. Figure 12.3B does the same for trust of the European Union; there are big falls in most countries. In the UK trust in the EU was low in both years, while Northern Ireland shows a fall from 2007 to 2017.

In another report published by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Dunatchik and coauthors found (2016) that 61 percent of people in the UK living on low incomes didn’t trust politicians to tell the truth versus 50 percent of the higher-income group. When asked if “public officials don’t much care about what people like me think,” 39 percent of the low-income group said they “strongly agree” versus 19 percent of the high-income group. In response to the question “People like me don’t have any say in what the government does,” 38 percent of the low-income group strongly agreed versus 22 percent of the high-income group. As Guardian columnist Rafael Behr has noted: “Britain is strangled by barbed-wire fences of class, region, wealth, faith, age, the urban, the rural, Leavers and Remainers.”41

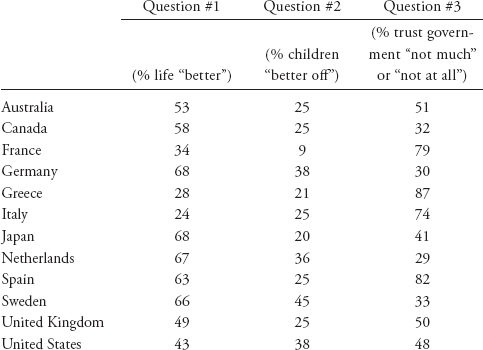

In its 2017 Global Attitudes Survey, Pew asked respondents in thirty-eight countries, developed and developing, about their well-being and their trust in their government.42 The data are available for download. I am particularly interested in the responses to three questions:

Figure 12.3. (A) Percentage of those who trust their national government. (B) Percentage of those who trust the European Union.

Question #1: “In general, would you say life in (survey country) today is better, worse, or about the same as it was fifty years ago for people like you?”

Question #2: “When children today in (survey country) grow up, do you think they will be better off or worse off financially than their parents—better off; worse off; or the same?”

Question #3: “How much do you trust the national government to do what is right for (survey country)—a lot, somewhat, not much, or not at all?”

Below I report the percentages saying “better” to question #1; “better off” to question #2; and “not much” or “not at all” to question #3, with respondents who said “don’t know” or who refused to answer excluded from the calculations, for twelve advanced countries.

It is apparent that in countries that were hit hard by the recession, for example, France, Greece, and Italy especially, more than two-thirds say that people “like you” are no better-off in 2017 than they were in 1967. More than half said that in the UK and the United States. The majority of respondents in every country don’t believe that children will be as well off as their parents. Perhaps not surprisingly, trust in government is low when people are hurting and many have lost hope for the future of their kids.

It takes time to change the culture and rebuild communities. Putnam, Feldstein, and Cohen (2003) are right that we are better together. Now is the moment to try to rebuild our social capital. It is time to stop the breaking apart. Putnam (2015, 228) notes that it took several decades for economic malaise to undermine family structures. It will take decades to reconstruct them. Heckman and coauthors (2009), for example, have noted that investments in early childhood education convey high rates of return of 7–10 percent. It is hard to see what arguments there are against it.

In private communication, the always brilliant and insightful Robert Putnam told me, “The long-term crisis of the older manufacturing communities has undermined community morale and fractured old assumptions about self-worth…. These are people deeply anxious and angry about the decay of their communities not just upset that they personally lost their job…. Isolated people (isolated older white less educated guys, especially) in socially isolated or fragmented communities are much more vulnerable to Trumpism.”

Going forward we are going to have to build ties that bind. Trust has to be rebuilt. Hate has to go. As a first step something has to be done about inequality and the overall sense of unfairness that is in the air. Too many people have been left behind. Little has changed, and these problems are going to persist going forward especially as Trump and Brexit fail to deliver on their promises. A storm of fury may well be on the horizon. I see little sign that any of this is going to change any time soon or that anything will be done to right these wrongs.

The lies need to be challenged. The BBC’s Emily Maitlis distilled the challenge when she demolished Sean Spicer, the former White House press secretary, with a simple description of the lies he told about the crowds on the mall at Donald Trump’s inauguration: “You joked about it when you presented the Emmy awards. But it wasn’t a joke. It was the start of the most corrosive culture. You played with the truth. You led us down a dangerous path. You have corrupted discourse for the entire world by going along with these lies.”43 Richard Wolfe is right. The lies need to stop.44 The guilty plea of Michael Cohen where he implicated the president in campaign finance illegalities and the conviction of Paul Manafort on the same day, August 21, 2018, look like important turning points. The Democrats have gained chairmanships of vital House committees and consequently subpoena power. It doesn’t look, from thirty thousand feet, that peace and harmony are about to break out.

Green Eggs and Ham: Pitchforks to the Ready

Thorstein Veblen in his 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class made it very clear that the rich care about what he called conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption means spending money on luxury goods and services to display economic power. The poor notice. Sir Philip Green bought British Home Stores (BHS), which I remember from my childhood as a rather rundown department store, in 2000 for £200 million. It didn’t perform well, and he sold it for £1 and eventually it closed with the loss of 11,000 jobs. Despite the deficit of £571 million in the BHS pension scheme, Green and his family collected £586 million in dividends, rental payments, and interest on loans during their fifteen-year ownership. In 2016, he bought his third yacht, named Lionheart, for £100 million. The people surely notice the fat cats. And still nobody has taken his knighthood away, although there was a vote in the House of Commons recently to do just that; they did eventually strip Fred Goodwin, of RBS “fame,” of his in 2012.45 Ordinary people are aware that different rules appear to apply to them. The man (or woman) on the Clapham omnibus just doesn’t understand. Nor should he.

I recall listening to billionaire John Cauldwell, who is the cofounder of mobile phone UK retailer Phone 4U, being interviewed on BBC HARDtalk on April 2, 2015 (downloadable from iTunes), about his motivations to get rich. He said he was motivated to make enough money to take care of his family; it was about financial security. Then it became about wealth and he wanted to get higher on the Times rich list. That lasted for three or four years. Then he thought about fulfilling the two parts of his childhood mission, which were to be wealthy and to be philanthropic. Phone 4U was worth £1.5 billion when he sold it in 2006 because he worried, rightly, there was a UK recession coming. “It’s nice to be a winner,” he said. It took him eight months to sell his first twenty-six phones. At one time he was, and he may well still be, the highest income tax payer in the UK. He was concerned, though, about the poor. “You cannot have a society where the rich are so stunningly rich, unbelievably rich and the poor are starving on the street. You can’t have that,” Cauldwell argued. When pushed, he agreed with the memo that Nick Hanauer, venture capitalist and billionaire, wrote to “My fellow zillionaires.”

If we don’t do something to fix the glaring inequities in this economy, the pitchforks are going to come for us. No society can sustain this kind of rising inequality. In fact, there is no example in human history where wealth accumulated like this and the pitchforks didn’t eventually come out. You show me a highly unequal society, and I will show you a police state. Or an uprising. There are no counterexamples. None. It’s not if, it’s when.46

Today Cauldwell is a major philanthropist. This again is very personal. He is a major contributor to the Great Ormond Street children’s hospital in London that saved the life of my youngest daughter when she was a baby. Their motto is “the child first and always.” Close to home. Bless him.

Great Ormond Street had, perhaps, an even more famous donor, J. M. Barrie. Although he and his wife were childless, Barrie loved children and had supported Great Ormond Street Hospital for many years. In 1929 Barrie was approached to sit on a committee to help buy some land so that the hospital could build a much-needed new wing. Barrie declined to serve on the committee but said that he “hoped to find another way to help.” Two months later, the hospital board was stunned to learn that Sir James had handed over all his rights to Peter Pan. At a Guildhall dinner later that year Barrie, as host, claimed that Peter Pan had been a patient in Great Ormond Street Hospital and that “it was he who put me up to the little thing I did for the hospital.”

On April 12, 2012, the Dartmouth Medical School changed its name to the Audrey and Theodore Geisel School of Medicine. Theodore Geisel was a Dartmouth graduate of the class of 1925. During his time as a student at Dartmouth he adopted a pen name, “Dr. Seuss.” My kids grew up reading The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham and One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish and other such wonders. I even met a lady once in Hanover at a dinner party who knew Geisel and when she was a kid went with her parents to buy his new book in the Dartmouth bookstore and saw she was one of the characters. Gobsmacked apparently.

It is traditional for Dartmouth freshmen returning from their trips in the New Hampshire wilderness to stay overnight at our Moosilauke Ravine Lodge in the White Mountains and to be served green eggs and ham for breakfast in honor of Dr. Seuss. Nice. The Geisels, the most important philanthropists in Dartmouth’s history, were generous donors to the school during Theodore Geisel’s lifetime and made significant provision for the college in their estate plans, reflecting the wealth generated by the beloved stories of Dr. Seuss (over 3.5 million hardback books sold in 2015 alone).47 Dartmouth now has the Geisel School of Medicine.

Forbes reported that Theodore Geisel is the eighth-highest-earning deceased celebrity with earnings of $16 million in 2017 after Prince (7), Tom Petty (6), Bob Marley (5), Elvis Presley (4), Charles Schulz (3), Arnold Palmer (2), and Michael Jackson (1).48 Where are the other great, living philanthropists besides Bill and Melinda Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Warren Bufiett? And now John Cauldwell.

Pitchforks to the ready. Relative things matter. The left-behinds who struggled noticed the elites were doing fine. Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2017) argued that “an economy that fails to deliver growth for half of its population for an entire generation is bound to generate discontent with the status quo and a rejection of establishment politics.” In a new international study called “Risks That Matter” the OECD (2019) found that in the twenty-one countries they studied, on average two-thirds of respondents picked “yes” or “definitely yes” when asked, “Should the government tax the rich more than they currently do, in order to support the poor?” In the United States 63 percent said “yes” or “definitely yes” compared with 62 percent in France, 69 percent in Canada, 73 percent in Italy, and 77 percent in Germany.

It would make sense to encourage philanthropy. It’s time to do something about income and wealth inequality. Doing something about the cumulative disadvantage we are observing is in the rich’s interests as Cauldwell realized. The haves need to help the have-nots and the left-behinds as they did in years gone by. The question is, how?

It Is Time to Put the Pedal to the Metal and Get the Job Market Humming Again

Now is the time to be all in this together. First, we need to get to full employment and fast, wherever that is. It is time to keep priming the pumps. That would raise wages and lift spirits markedly.

Pulling back as the Fed did by raising rates was an error. There is nothing in the data that suggests they should do this. The world is different post-2008, and most policymakers still haven’t realized that and are living in the past when unions were powerful and there was no Internet; no iPhones; no iPads; no Netflix; and little or no globalization.

My son lives in Texas near an Amazon facility. He was in a swimming pool with his buddies one Saturday afternoon and ordered an inflatable pong table, as one does. (Don’t ask, it’s a beer-drinking game.) He called me up and said, “Dad, I love America. Guess how long it took for it to be delivered? Forty-five minutes.” The world has changed, although maybe not for the better. The inflatable table lasted a couple of hours before it burst.

There is still a lot of slack in the U.S. labor market, which is why wage growth is well below what it was in the past at equivalent rates. The same applies in other countries including the UK and Germany, which also have unemployment rates below 5 percent. We need to encourage people to work by boosting labor demand and labor supply will follow. Inflation is a problem of a bygone age.

Beveridge showed it is possible for unemployment to surprise and go really low without bad consequences. That would ensure workers are standing by waiting for job offers. There is nothing to fear except fear itself. That would push up wages and get the economy humming again. Once that has been achieved we can move on to address other problems. It is unclear when that would be but, as the saying goes, “I don’t know how to define pornography but when I see it I will know.” This will especially help people at the low end.

Having the economy cranking, and on fire, which hasn’t happened in our lifetimes, with firms searching for workers, would allow those who have been pushed lower down the occupational pyramid to make better use of their skills. Young people with degrees who were forced to take jobs done previously by those with high school education could move to graduate-level jobs. It would allow the underemployed to get more hours. It would allow workers to move from part-time jobs they were pushed into to full-time jobs, which would increase their happiness. It would allow the unemployed to get jobs and increase their happiness and that of everyone else. It would make being out of the labor force less attractive as the alternative of holding a job that paid more. This would be great for workers. Hard to see what is stopping it.

The move to defined contribution plans from defined benefit plans hurt workers in a recession. The value of their savings fell, hence many put off retiring. If they had been receiving defined benefit plans their payments would have been protected. Folks with defined contribution plans have no reason to retire; there is no compulsory retirement age for faculty, who are on defined contribution plans where I work. I have no intention of retiring any time soon. I still like my students!

To do this would require further monetary and fiscal stimuli. It would mean that central banks such as the Fed would have to stop raising rates and possibly turn them negative, although it is yet to be established that that is even feasible. This could well mean more quantitative easing. The idea that the ECB should stop doing quantitative easing when the unemployment rates in the Eurozone are high and underemployment remains high makes no sense. Japan is the precedent.

Central bankers have focused like a laser beam on nonexistent inflation, which was a story of the 1970s when unions were stronger. We know that even if inflation gets to 5 percent or so it isn’t hard to stop it from going higher by raising rates. The problem is what to do in deflationary periods such as we saw post-recession. Shiller (1997) shows that people tend to dislike unemployment more than inflation. In work with David Bell and coauthors (Blanchflower et al. 2014), we showed that a 1-percentage-point rise in unemployment lowered well-being five times more than the equivalent rise in inflation. Joblessness hurts.

Moving to full employment would boost wages, which is its main point, and hence boost living standards. In the UK on March 9, 2017, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimated that median earnings will be no higher in 2022 than they were in 2007, before the financial crisis. Paul Johnson, the IFS’s director, said that almost a decade on the prospects for income and earnings growth remained weak: “what really matters to people is what is happening to their incomes. Income and earnings growth over the next few years still look like being weak. On current forecasts, average earnings will be no higher in 2022 than they were in 2007. Fifteen years without a pay rise. I’m rather lost for superlatives. This is completely unprecedented.49

Second, an obvious way to boost labor demand is to increase infrastructure spending in the United States and the UK, which would create jobs although it is not obvious for whom and where. The big hang-up with the size of the debt makes no sense as every nation has both assets and liabilities. Plus, in 2018 and beyond money can be borrowed very cheaply. It matters mostly what the debt is used for, rather than its size. We also know that countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios can grow and the 90 percent rule has been debunked by Thomas Herndon. Consumption bad, investment good. There are many worthwhile projects that can be started, not least roads and bridges and public transportation. It is time to get commuting times down which, if it does nothing else, would increase happiness. It would also raise GDP of course.

The United States’ crumbling infrastructure needs to get fixed, but the talk of a big infrastructure package has disappeared from the political radar screen. It is time for a new, New Deal. It’s time to put America back to work. The unemployment rate of construction workers in the United States is still relatively high, at 5.4 percent. Private construction spending only returned to its pre-recession levels in 2014 and is up only 5.9 percent in nominal terms since its pre-recession high in February 2006.50 Public construction in April 2018 was at broadly the same level it was at its pre-recession peak in November 2007. So, there is capacity for a construction burst to make up for the bust. An infrastructure plan may well be something the Democrat-controlled House and Donald Trump could agree upon in 2019.

Construction contracts can emphasize job creation. The federal government can move some of its own operations to deprived areas and set up enterprise zones to make it cheap for firms to move there. It makes sense to provide workers with incentives to work. A further issue is to provide incentives for firms to use labor over capital. The reason that technology has replaced jobs is that it has a relatively low price. It is time to give firms incentives to hire and train workers, to invest in human capital, rather than in machines. The practicalities of how you could do this are not simple. One way that has been found that is labor intensive is to encourage refurbishment of old properties rather than build new, which is more capital intensive.

Third, it is time to do something about changing attitudes and making them more positive. Blinder and Richards (2016) found that preferences for reduced migration in the UK have been softening in recent years. Grigorieff, Roth, and Ubfal (2016) conducted a set of experiments that suggest intriguing possibilities. First, they used a large representative cross-country experiment to show that when people are told the share of immigrants in their country, they become less likely to state that there are too many of them. Then, they conducted two online experiments in the United States, where they provided half of the participants with five statistics about immigration before evaluating their attitude toward immigrants with self-reported and behavioral measures.

This more comprehensive intervention improves people’s attitude toward existing immigrants, although it does not change people’s policy preferences regarding immigration. Republicans become more willing to increase legal immigration after receiving the information treatment. Finally, they measured the same self-reported policy preferences, attitudes, and beliefs in a four-week follow-up, and they show that the treatment effects persist. Specifically, these results suggest that targeting individuals with the most negative views on immigration would be the most effective way of changing people’s attitudes toward immigrants.

The thirty-fourth British Social Attitudes Survey published in 2016 found that attitudes toward austerity were changing. After seven years of government austerity, public opinion showed signs of moving back in favor of wanting more tax and spend and greater redistribution of income. For the first time since the financial crash of 2007–8, more people (48%) wanted taxation increased to allow greater spending than wanted tax and spend levels to stay as they were (44%). More people (42%) agreed than disagreed (28%) that government should redistribute income from the better-off to those who are less well off. Shortly before the financial crisis fewer people supported redistribution than opposed it (34% and 38%, respectively, in 2006). The survey also found that attitudes toward benefit recipients were starting to soften and people particularly favored prioritizing spending on disabled people.

However, while these represent notable changes as compared with recent years, they still only represent a partial move back to an earlier mood. The 48 percent of people who now want more taxation and spending is greater than a joint-record low of 32 percent in 2010 but still lower than the rates of 63 percent in 1998 and 65 percent in 1991. People’s top priorities for more spending remain as they have always been: health and education. Around 8 in 10 think the government should spend more or much more on health care (83%); 7 in 10 on education (71%); and 6 in 10 on the police (57%). Over time the proportion in the British Social Attitudes Surveys who say most dole claimants are “fiddling” has dropped from 35 percent in 2014 to 22 percent in 2016—its lowest level since the question was first asked on the survey in 1986. They also found the proportion of people (21%) that agree that most social security claimants do not deserve help is at a record low, down from 32 percent in 2014. It seems people are less supportive of austerity than they were. There is hope.

Fourth, it is time to subsidize childcare for working moms and dads. This could be done by making childcare costs fully tax deductible, which would encourage work, or states could offer subsidies. My friend who owns a child-care center would be delighted!

Fifth, mobility in the United States has halved in half a century. So, measures to help people move would make sense, especially from the states that are struggling. My kids moved to Texas, South Carolina, and Massachusetts to find work once they graduated from college because that is where the jobs are. Countries that have low mobility like Spain and Greece have high unemployment rates. Help needs to be given to young people to move out of their parents’ basements and strike out on their own. Doing so would likely involve helping young people deal with their staggeringly high levels of student debt. Making student loans fully tax deductible would make a lot of sense. Encouraging mobility would be a start; tax subsidies for moving make sense.

By December 2017 the UK, over the preceding year, was the slowest-growing country in the EU. In part, the decline in net migration was because of the fall in the pound, which lowered the relative attractiveness of working in the UK, and the slowing economy as a result of the Leave vote meant there were fewer opportunities. In addition, the UK has become a less welcoming place. “These changes suggest that Brexit is likely to be a factor in people’s decision to move to or from the UK,” said Nicola White from the Office for National Statistics.51 Research by Portes and Forte (2017) suggested that as a result of Brexit continued lower net migration from the EU over the coming years will be negative for GDP per capita.

It is time to encourage migration, especially for young people so they can move out of their parents’ basements. States are already trying their own schemes. The state of Vermont recently announced a plan to encourage freelancers to move to the state and offered a subsidy of $10,000.52

Sixth, another obvious possibility is to use the tax code to reduce income and wealth inequality. It would make sense that it would encourage work, so raising the threshold below which you pay tax would help. Another obvious possibility would be to lower tax rates on those who make less than the median income. It would also make sense to remove the cap on social security, which makes no sense. Contributions should just rise as a fixed or even a rising proportion of income. It would make sense for a millionaire to pay at least the same proportion as his or her secretary and for a billionaire to pay a higher proportion than a millionaire. I am a great believer in providing incentives to work. It is inappropriate to subsidize indolence.

Finally, it is time to look at ways of encouraging and giving incentives for work to those at the bottom. There has also been talk of Universal Basic Income (UBI) whereby the federal government would provide each adult below a certain income level with a specific amount of money each year. It acts as a negative income tax. In a new Gallup poll taken in February 2018 an astonishing 48 percent of Americans support this idea. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won a surprise primary election in New York and called for a universal jobs guarantee, under which the federal government would provide a job for every American. This has support from Bernie Sanders. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) has introduced legislation that would see a three-year pilot project set up to guarantee jobs in fifteen regions of high unemployment. Among the bill’s co-sponsors is Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), who tweeted in support of the policy in April. The premise, as Laura Paddison notes, is that everyone should be entitled to a good job, one that pays at least $15 an hour and comes with health and other benefits.53 These would potentially improve the lot of ordinary working folk, but unless there is a major move to the left these plans have little chance of being implemented.

We will have to wait until 2019 to find out whether Finland’s UBI experiment worked.54 Personally I would pilot studies to work out whether they are cost-effective. There may be better ways to lift living standards at the low end. Nobel Economics Laureate Jim Heckman and Jeff Smith (2000) examined the Job Training Partnership Act, which was a well-meaning attempt to help disadvantaged youths, and found that it had a negative impact on the earnings of disadvantaged males and zero impact on the earnings of disadvantaged females, and the program was closed. We need to invest in programs that work rather than waste money on programs that don’t. That would likely mean lots of testing and piloting programs. What is generally clear is that what works in one place, say, Cleveland, may not work in Denver. Fifteen dollars an hour is very different in New York City than it is in New Orleans. I was always told that the federal minimum wage didn’t bind north of the Mason-Dixon line. North of that line, including in New Hampshire, McDonald’s sets the wage.

When I was first employed as a young lecturer in London the trade union had been fighting for a “part-timers charter” for lecturers who worked up to thirty hours a week. The union managed to negotiate that these additional rights would be given to every lecturer who worked more than sixteen hours a week, which the majority did. The next day after the agreement was signed the employer cut everyone’s hours to below sixteen. The following day the agreement was scrapped.

What if Brexit and Trump Don’t Deliver?

A big question is, what happens if Brexit and Trump don’t deliver? So much has been promised and disappointment is in the air.

Will the pandemic spread, as the flu pandemic did in World War I, or will it be slowed by macroeconomic failure or boosted by macro success? What if Macron can’t turn the French economy around as Hollande, Sarkozy, and Mitterrand were unable to do? What happens if the American, French, and British economies slow? Maybe the riots will no longer be silent? Le Pen isn’t going away. Will the move to right-wing populism expand into other EU countries? Will the markets turn on Jeremy Corbyn if he becomes prime minister? A YouGov poll of 3,380 UK adults on June 7, 2018, found that 46 percent of respondents said that they expected Brexit to go badly and it has; 27 percent said they thought it would go well and it hasn’t.55

Brexit negotiations are going badly, and there is growing talk of a second referendum after 700,000 demonstrated peacefully in London. In the period since the Brexit vote in 2016 the UK has slipped from being the fastest-growing country in the EU to the slowest. A forecast by the EU Commission at the end of 2018 was for the UK and Italy to be the slowest-growing countries in the EU28 in 2019. The EU forecast was 1.7 percent in 2017; 1.3 percent in 2018; and 1.2 percent in 2019 and 2020.56 The official forecaster in the UK Office for Budget Responsibility had broadly similar weak GDP forecasts for these four years: 1.75, 1.3, 1.6, and 1.4 percent.57

On December 4, 2018, the UK government lost three votes in the House of Commons that held it in contempt of Parliament for not releasing the full legal briefings it had received on Brexit.58 In a second blow the European Court of Justice ruled on December 10, 2018, that the UK can unilaterally revoke Article 50, arguing that a member state “cannot be forced to leave the European Union against its will.” Later the same day, in what the Financial Times called a “humiliating setback,” Prime Minister May canceled the Brexit vote, which she was inevitably going to lose.59 The pound fell sharply on the news to an eighteen-month low of $1.2559, down 1 percent, and even more against the euro, to €1.1061, down 1.36 percent on the day. Yields on gilts also fell and the UK-focused FTSE 250 was down 2 percent on the day.

Once the vote on Brexit was pulled by the government, a sufficient number of Tory Brexiters opposed to the deal wrote to Sir Graham Brady, the chairman of the 1922 Committee, to trigger a vote of no confidence against Theresa May. In a last-ditch attempt to win, Number 10 Downing Street suggested that May would stand down before the next election. I was watching CNN the morning of the confidence vote, which went live to Prime Minister’s Questions from the House of Commons for a good twenty minutes. At the end anchor Alisyn Camerota described what we had all been watching as “something out of Monty Python,” which seems to be how the world now sees the Brexit debacle. May won the vote narrowly, but her position has been weakened, and it remains unclear if she will survive through the end of 2019, as there is no chance her Brexit plan can become law. The next day the prime minister went back to the EU Commission to try to get further concessions and, as expected, came home empty-handed. It was unclear why, after two and a half years of negotiating, she thought she could get more in an evening. The Sun’s colorful headline on her return was “EU Leaders Tell PM to Get Stuffed.” After two failed attempts to get May’s deal through Parliament, less than two weeks before the UK was meant to leave the EU at the end of March 2019, Speaker John Bercow announced that he would not allow a third vote on the withdrawal agreement without substantial changes. Bercow’s decision was based on an official parliamentary rule book that was first published by Thomas Erskine May in 1844 that says you can’t keep voting on the same bill hoping you will get a different result. Brexit is going to be delayed. Chaos reigns.

The OECD in its forecast from November 2018 has GDP growth in the UK at 1.3 percent in 2018; 1.4 percent in 2019; and 1.1 percent in 2020. Its forecasts for Germany (1.9%, 1.8%, and 1.6%) and Italy (1.0%, 0.9%, and 0.9%) look optimistic as there are signs both are headed to recession in early 2019. According to the U.S. Census Bureau the median sales price of new homes sold in the United States fell in October 2018 to $309,700, down 3.1 percent from a year earlier and the lowest since February 2017. The Great Recession started in the U.S. housing market.

The problem is that the many populist promises were just pie in the sky and totally impractical. The Brexiters appear to have had no plan at all on what Brexit would look like. During the French Revolution, eventually the wine ran out. It was never going to be possible in France for Marine Le Pen to lower the retirement age to 60; the markets wouldn’t allow it. The beautiful wall was never going to be built and Mexico was never going to pay for it. The GOP had no plans ready for repealing and replacing Obamacare as they didn’t think Trump was going to win. Now the Tory party in the UK is fighting with itself like ferrets in a sack over soft or hard or no Brexit. The fact that the government has admitted that it is stockpiling food and medicines in case of a no-deal Brexit in 2019 doesn’t augur well for the future, or indeed for support of such an action among the electorate.

The big rise in bank stocks after Macron won in the first round of the French presidential election gave a hint of what would have happened if Le Pen and Mélenchon were going to be fighting out the second round. Le Pen offered broadly popular programs to help her core voters. Early retirement at age 60 was obviously unaffordable as people live longer. This is an indicator of the scale of what could happen in UK markets if there is a disorderly Brexit disaster. It would likely result in a cataclysmic global fall in markets.60 It gives an indicator of what would have happened if Le Pen had won.

The markets would have inevitably responded badly and dropped sharply. As Clinton advisor James Carville famously said, “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” He also coined the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid.” Thankfully markets stop politicians from doing dumb stuff.

Boosting growth is especially helpful for those at the bottom. The problem, though, is how exactly will that help West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania? How will it help the left-behinds in Wakefield, Blackpool, Toledo, or the Pas de Calais? Coal isn’t coming back. Steel and talc aren’t going to return, and the tourists aren’t going to return to English seaside towns, so something else needs to. The march of technology continues. Trump has declared, “We are taking care of our miners,” despite absolutely no evidence to support such a claim. The tariffs have hurt Trump’s core supporters, hence the need for a $12 billion bailout that has not gone down well with the GOP. Senator Ron Johnson (R-WI), whom I met once and had a perfectly sensible conversation with, declared, “This is becoming more and more a soviet-type economy here.”61

Capital is cheap relative to the price of labor. So, changing the relative price of labor can help raise the demand for good jobs. This can be done by providing incentives for firms to hire people rather than invest in capital. That is the change in the tax code that is needed. It would make sense to lower the relative price of labor. Tax reform that gives incentives for individuals to work also makes sense; earned income tax credits seem to work. Reforms need to be business friendly, because workers benefit generally from a firm’s increased ability to pay. But they see no necessity to pay. That needs to change, and firms must be given incentives to share their profits with workers. It may take shaming them into it, but that’s ok. Financial incentives work.

The tax code can swing into action here to reward work for those at the low end. One way would be to provide large earned income tax credits. The idea is to reward work. Plus raising the tax threshold at the bottom can help. For many who don’t pay taxes, a negative income tax would help to lift their earnings. The tax code should be used to lower after-tax inequality. Lowering inequality seems a good idea. As Levitsky and Ziblatt have noted, though, “Adopting policies to address social and economic inequality is, of course, politically difficult—in part because of the polarization (and resulting gridlock) such policies seek to address” (2018, 229).

All hands to the pump. It’s time to take a chance. Borrow to invest, especially in people in the country’s future. The New Deal worked. Spending trillions on rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure is a really good idea. There seems to be no chance that is going to happen, but it should. Austerity needs to become a long-ago nightmare.

The concern may be that in the long run it will not be possible to Make America Great Again for the less educated. Settlers arrived in the United States and obtained vast amounts of wealth. There were economic rents to be shared, and less-educated Americans obtained living standards for themselves that were simply not replicated by similar workers in Europe and beyond. The onset of global competition may mean that world has gone forever. It may not be possible to lift the living standards of Trump supporters back to where they were half a century ago. The UK and France will not be able to restore empire and share the spoils of monopoly power as they did a century ago.

There was never going to be lots of money after Brexit to fund the NHS. In June 2018 Prime Minister May once again was talking about using a Brexit dividend to fund the NHS although there is none. No post-Brexit paradise. No deal with the EU that doesn’t allow for free movement of capital, services, goods, and people. You can’t eat sovereignty. No repeal of Obamacare. No draining of the swamp. No return of steel or coal jobs. No wall. Dreamland. Your Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid were never safe, and the middle class was never going to get big tax cuts. The lobbyists were always going to ensure the tax cuts mostly went to business and rich donors. There has been no action on guns even after all the school shootings, even when the vast majority of Americans supported such moves. Trump promised there would be, but the NRA stopped all that. Inequality is going to rise, not fall, despite what was promised on the campaign trail. Wages haven’t risen much and show little sign of getting going. The blame game has already begun.

William Beveridge, once again, in Full Employment in a Free Society, argued that full employment “means having always more vacant jobs than unemployed men, not slightly fewer jobs. It means that the jobs are at fair wages, of such a kind and so located that the unemployed men can reasonably be expected to take them” ([1944] 1960, 18). The same applies to unemployed women these days too. Fair wages for all would be good.

We were never all in this together and it is time we were. We are better together. People are hurting. The worry is that policymakers have not learned from their mistakes, but now they have little firepower to deal with the onset of the next economic crisis. The whole world wants a good job. Gizza job.