Japanese Naval Air Power Destroyed

In the first six months of the Pacific War, naval air power spearheaded the offensive operations undertaken by Japan. In the early hours of 7 December 1941, the first wave of aircraft from Admiral Nagumo’s strike force streaked toward the green hills of Oahu.1 By ten o’clock that morning, as the second wave departed the skies over Pearl Harbor, the American battle line at Ford Island had been shattered, and the aircraft at Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows airfields and those at Kaneohe Naval Air Station lay in shambles. Historians will endlessly debate the wisdom or folly of Nagumo’s decision not to follow up with a third attack, given that the two American carriers based at Pearl Harbor were at sea and that the oil storage tanks and submarine force at Pearl were left virtually unscathed. Yet there is little doubt that these targets could have been destroyed by Nagumo’s force. And, for our purposes in this study, the important issue is not the strategic decisions involved but the dramatic demonstration of naval air power with which Japan was able to open the war.

A few days later and 7,000 miles westward, Japanese naval air power delivered a stunning blow at sea by sinking the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse off the coast of Malaya in the opening days of the war. Because it followed aerial assault tactics that the navy had perfected in the years prior to hostilities and because it was the dramatic land-based counterpart to the carrier-based destruction of the American battle line at Pearl Harbor, it is worth pausing to reflect on the nature of this outstanding success by Japanese naval air units.2

As noted earlier, the Kanoya Air Group had become the navy’s crack land-based torpedo force. Immediately upon learning of the arrival of the Repulse and Prince of Wales at Singapore, the navy had rushed the Kanoya’s twenty-six G4M1 bombers to join the Genzan and Mihoro naval air groups of the Twenty-second Air Flotilla stationed near Saigon since October. The Twenty-second was already a solid outfit, its bomber crews having trained and fought together for several years, though their experience had largely been bombing land targets in China rather than ships at sea. Against the two British ships, the navy planned to use both bombs and torpedoes. Conforming to standard navy doctrine, the attack would open with a high-level bombing attack. The Japanese did not expect to sink either ship with this tactic, because the bombers carried no armor-piercing bombs of the type used to destroy the Arizona, all of them having been allocated to the Hawai’i operation.3 Rather, the purpose of the bombing attack was to smash the upper works of the enemy ships and to distract the gun crews from the approaching torpedo bombers that were to deliver the coup de grâce.

The original plan had called for simultaneous attacks by all three air groups. But the groups were given a “search-and-attack” mission in which the elements of each group flew on independent search arcs assigned to them, and they did not all receive information concerning the position of the enemy fleet at once. For these reasons, they arrived over it at different times. Once in position, however, the aircrews conducted their attacks with skill, discipline, and determination despite the furious antiaircraft defense put up by the two warships. No special instructions had been given to the aircrews upon taking off; they simply followed the tactics in which they had trained. The horizontal bombers of each squadron came in at a height of about 1,500 meters (5,000 feet) and dropped their bombs in a close triangular pattern. The torpedo bombers came in at right angles to their targets, launching their torpedoes at about 900–1,800 meters (1,000–2,000 yards) from the ships and about 30 meters (100 feet) above the water. While the horizontal bombers of the Mihoro and Genzan air groups scored some hits, it was the devastating torpedo assaults by the Kanoya Air Group that finished off both British ships.4 The last of the air groups to locate the British fleet, the Kanoya aircrews had arrived on the scene after six hours of continuous flying and had been within five minutes of having to return to base because of fuel limitations. But neither these conditions nor the loss of three bombers to British defensive fire in any way lessened the efficiency of the Japanese attack. The captain of the Repulse, who survived the sinking, later attested, “The enemy attacks were without doubt magnificently carried out and pressed well home. The high level bombers kept tight formation and appeared not to jink.”5

The sinking of the Repulse and Prince of Wales marked the first time in the history of naval warfare that capital ships under way were sunk by an attack carried out exclusively by aircraft. It convinced even those in the Japanese naval high command who had scoffed that the battleships sunk a few days before at Pearl Harbor had been “sitting ducks” for aerial attack. It was argued at the time—and has been argued again in the more than half a century since—that the contest was hardly equal, since the British ships had been without air cover. But one of the Japanese torpedo squadron commanders insisted after the war that air protection would have made little difference. For one thing, he insisted, Japanese navy training for attacks on surface units had always assumed heavy fighter defense, and, for another, the obsolescent Brewster Buffaloes, the only fighters available to the British, would have been quickly destroyed.6

The morale and skill of these Japanese aircrews give credit to his statement. These are assets that are usually best honed by constant and rigorous training, something the three Japanese air groups, particularly the Kanoya, had in abundance. With the onset of actual combat operations, when there is often very little time for training, the precise aim and timing of air attack units begin to fall off. The Repulse and Prince of Wales went down under the bombs and torpedoes of aviators whose skills were at their peak.7

AT THE CUTTING EDGE OF WAR

Air Power in the Japanese Conquest of Southeast Asia

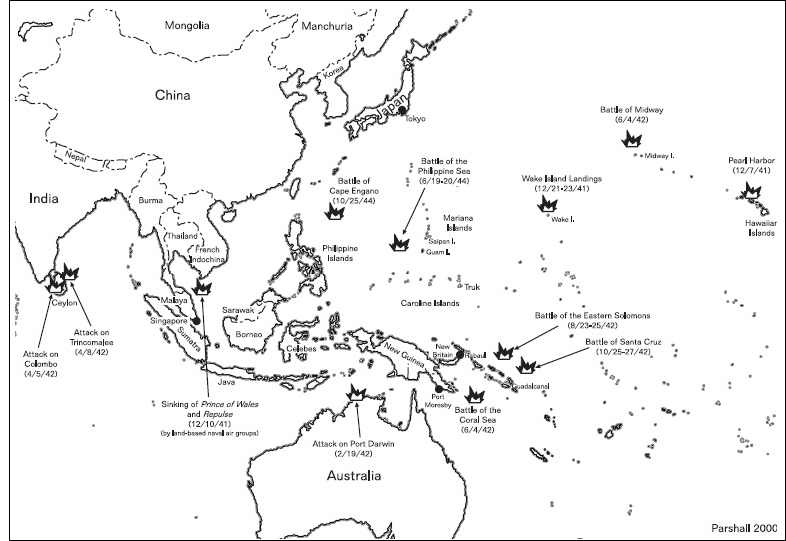

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, salutary lessons in the destructive capacities of naval air power were also delivered by Japanese naval air units.8 (Map 7-1.) Early on the afternoon of 8 December (7 December east of the International Date Line), after a harrowing delay caused by fog over the airfields on Taiwan, G3M and G4M bombers of the Kanoya, Takao, and First air groups, accompanied by Zero fighters of the Third and Tainan air groups, lifted off to attack American air bases in the Philippines. Completely surprising the enemy, the Japanese formations destroyed much of the American heavy bomber force at Clark Field and had shot up fighter aircraft at Iba and Del Carmen. These opening raids, employing the strafing tactics perfected in China, seriously reduced Allied air power as a significant factor in the western Pacific for the next six months of the war. To the south, on Mindanao, fighter and bomber aircraft from the Ryūjō attacked the naval base at Davao. One of the most spectacular Japanese operations was accomplished some weeks later when twenty-four Zero fighters of the Tainan Air Group based on Taiwan were dispatched on a mass nonstop flight of 1,200 nautical miles to occupy the airfield at Jolo Island at the southern end of the Sulu Sea, an unprecedented mission for single-seat fighters and proof of the amazing reach of the Zero.

For the next two months Japanese naval aircraft raced out in front of Japanese landings in Malaya, the Philippines, and the Netherlands East Indies, blasting Allied military and naval facilities, crippling Allied naval units, and shooting up the remnants of Allied air defenses, composed too often of planes that were inferior in both performance and numbers and flown by pilots whose combat doctrine was not equal to their courage. It was during these early months of the war that the myth of the near invincibility of the Zero was born in the minds of Allied pilots. Trying vainly to match the Zero turn for turn and finding themselves in the aerial environment where the A6M performed best—relatively low-speed low-altitude dogfighting—they found themselves at the mercy of Japanese navy pilots who jinked about the tropical skies, flaunting their acrobatic skills like rapiers.9

Map 7-1. Major Japanese naval aviation operations during the Pacific War, 1941–1944

This equation would change dramatically within a year, but in these first chaotic months of the war, the fighter pilots of the Japanese navy flew and fought in unchallenged triumph in advance of the near-unchecked progress of their nation’s ships and men. By February 1942, Malaya was gone, Singapore on the verge of surrender, and Java the only major Allied foothold left in the East Indies. Then it too fell to the Japanese in early March. The Japanese carrier force then launched a series of offensive operations that were unrivaled in their speed, force, and technical excellence until the American fast carrier operations of 1944–45. On 19 February, Admiral Nagumo’s four carriers slipped through the Banda Sea, and joining forces with land-based bombers that had advanced to Kendari in the southern Celebes, their aircraft struck at Darwin on the Australian north coast. At that port, their destruction of ships, aircraft, airfields, and valuable stores damaged a vital link in the lifeline between Australia and the dwindling Allied position in Southeast Asia.

From the East Indies, Nagumo’s force, now five carriers, bolstered by a number of battleships and cruisers, burst into the Indian Ocean in April 1942 with the twin objectives of sinking the British Eastern Fleet and annihilating British air forces on the western shores of the Bay of Bengal. While Nagumo failed to achieve either objective, aerial assaults in April against British naval units, naval bases, and shipping achieved major success. Under relentless attack by Nagumo’s carrier attack aircraft, principally Aichi D3A1 dive bombers, the Royal Navy lost one carrier, two heavy cruisers, and two destroyers. A separate sortie by a force centered around the carrier Ryūjō sank various transports and merchant vessels in the Bay of Bengal. The total cost of these operations to the Japanese was seventeen aircraft.

Through the early spring of 1942, therefore, Japanese naval air power, like a sword of finely tempered steel, had slashed away everything that stood in its way. In the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Japanese land- and carrier-based air groups, equipped with superior aircraft, manned by experienced, highly trained, and motivated aircrews, and directed by a well-coordinated strategy, had surprised, outfought, and outflown the ragtag collection of Allied air units, which had been inferior in everything but bravery. An American intelligence report midway through the war had this to say about Japanese naval aircrews in early 1942:

They were seasoned and experienced products of a thorough training program extending over several years. They were a distinct credit to the Navy’s long preparation for the Pacific War. Aggressive and resourceful, they knew the capabilities and advantages of their own aircraft and they flew them with skill and daring. They were quick to change their methods to meet new situations and to counter successfully the changes, modifications, and designs of Allied aircraft. They were alert and quick to take advantage of any evident weaknesses. Disabled aircraft, jammed or disabled guns and stragglers were sure to receive their concentrated fire.10

Source: Fukui, Shashin Nihon kaigun zen kantei shi, 1:331.

Japanese naval air forces suffered only slightly in these engagements, but it is a telling commentary on Japanese training policies and the consequently limited number of aircrews that even these light losses had already begun to impair the combat-effectiveness of certain Japanese naval air groups.11

THE BATTLES OF CORAL SEA AND MIDWAY, MAY–JUNE 1942

Then, in May, in the Coral Sea, Japanese naval air forces met their match. The opposing strategies and operations that led to the Japanese reverse do not concern us here and, in any case, have been covered in other studies. But what is clear is that by the time of the Battle of the Coral Sea, American carrier pilots had begun to learn how to deal with the combat methods of their enemy. While Japanese aerial assault tactics against warships continued to prove their worth, as demonstrated by the destruction of the carrier Lexington, American carrier fighter pilots took the measure of the Zero and learned how to fight it on their own terms—diving hit-and-run attacks from a superior altitude rather than the tail-chasing dogfights that were a Japanese specialty. The result was that the Japanese lost about sixty-nine planes and ninety pilots and other aircrews in addition to the light carrier Shōhō. The casualties among aviators from the fleet carrier Zuikaku were such that the ship was left with insufficient aircrews to participate in the subsequent epochal conflict at Midway a month later, since replacements took months to train.12

At Midway, of course, the scale of combat, the stakes, and the consequences were far greater.13 While there were multiple causes of the Japanese defeat, Japanese failures in intelligence and aerial reconnaissance prior to the engagement were critical. In the techniques of aerial combat, the United States Navy’s fighter pilots now fought their Japanese counterparts on a basis of equality, and sometimes superiority. Using new tactics, such as the Thach Weave, which exploited the weaknesses of the Zero, they began to hold their own against that vaunted aircraft.14

Again, I pass over the details and strategic context of battle to focus on the operational, tactical, and organizational implications of Midway for Japanese naval air power. First, it must be said that the nature of the Japanese defeat in that encounter has been frequently misunderstood. In strategic terms, there is little doubt that it was a momentous reversal in the tide of Japanese conquest in the Pacific, but it was not the “Battle that Doomed Japan.” In material terms, the destruction of four fleet carriers—the Akagi, Kaga, Soryū, and Hiryū—was, of course, a stunning loss, but other carrier hulls were on the slipways or being completed. One estimate is that the navy lost some 228 aircraft at Midway,15 but at this point in the war the navy was not suffering severe shortfalls in aircraft production.

Nor is it apparent that the defeat caused catastrophic losses to trained aircrews, the most precious element in Japanese naval aviation. Some generalized accounts of the battle imply that most of the Japanese aircrews participating in the battle were killed, and the conventional wisdom is that Midway therefore spelled the end of the navy’s highly trained carrier pilots. For years it was hard to dispute these conclusions, in part because surviving aircrews had been so scattered among the remaining warships after the battle that it had been impossible to make an accurate head count, and in part because the navy had taken such extreme measures to conceal the scale of its defeat from the Japanese public in the months and years following the battle.16

But careful sifting of the evidence in recent years has shown that in fact only about 110 Japanese fliers died at Midway (most of them from the Hiryū), no more than a quarter of the carrier aircrews the navy had at the start of the battle. American aircrew losses were actually greater than those of the Japanese, if Marine Corps aviators from Midway Island itself are included in the tally.17 Surprisingly, moreover, the morale of Japanese pilots seems to have been higher than ever after the battle. They were unimpressed by the combat skills of their American adversaries, and the superiority of their own skills seemed confirmed by the fact that they had crippled an American carrier. Nor did Japanese aircrew performance fall off sharply after Midway. In interviews after the war, Japanese navy men contended that the high quality of the navy’s air arm continued through at least the fall of 1942. In fact, the really serious aviation personnel losses at Midway were those of skilled aircraft maintenance crews, who accounted for perhaps twenty-six hundred of the three thousand shipboard personnel who went down with the four carriers.18

Four critical operational lessons were brought home to the Japanese navy after Midway. The first was the importance of a carrier fleet completely shaped for carrier war—that is, a fleet capable of operating independently and providing for its own air defense. Yamamoto attempted this force structure after the battle by his creation of the Third Fleet, centered on two fleet carriers, the Shōkaku and Zuikaku, for offensive missions and a light carrier, the Zuihō, for fleet air defense. Yet the Third Fleet represented a doctrinal compromise between the age of carrier warfare and traditional battleship doctrine. While its force structure was built around the carriers, its purpose was to contribute to the decisive surface engagement by controlling the air space over the projected battle area. It would be several years before the navy absorbed this lesson of Midway completely and formed a carrier force shaped purely by the needs of an air campaign.19

Second, in following current doctrine, the First Air Fleet’s concentration of carriers had proved disastrous. Expecting a straightforward attack against American base facilities on Midway and ignorant of the proximity of American carriers, the Japanese had no time to disperse their carriers before they were struck by American carrier aircraft. Three of the four Japanese fleet carriers involved in the operation were lost immediately. The Hiryū, the fourth carrier, which was separated from the others, was so badly damaged that she went down the day after she was struck. After Midway, Japanese carrier doctrine turned back to the compromise between concentration and dispersal. The navy’s surviving and newly commissioned carriers were now concentrated in divisions of three carriers each, but with each division widely separated from the others.20

Third, the battle forced the Japanese navy to rethink the composition of its carrier air groups. The emphasis on attack over fighter aircraft had meant that there had been inadequate numbers of the latter both for combat air patrol and as escort for carrier air strikes. For that reason, the complement of fighter aircraft for Japanese fleet carriers was significantly increased. Since the major objective of Japanese naval air power was to destroy the combat-effectiveness of enemy carriers, great efforts were made to improve the accuracy of Japanese bombing operations and to increase the number of dive bombers at the expense of reconnaissance planes and torpedo bombers.21

Fourth, the navy was forced to rethink not only the design and construction of its carriers to provide greater protection for carrier flight decks, aircraft hangars, and fuel storage areas, but also the processes and procedures for refueling and rearming aircraft. The former was attempted in the design of the Taihō-class carriers and the latter by post-Midway deck evolutions. Hangar-deck fueling and ammunition loading were forbidden, and all refueling and reloading were now to be carried out on the flight deck and in the shortest possible time. All wooden structures were eliminated, and soap-solution fire-extinguishing systems were made standard equipment in Japanese carriers following the Midway debacle.22

ATTRITION IN THE SOUTHWESTERN PACIFIC, 1942–1943

Yet if the Japanese navy had suffered stunning reverses at sea, its position ashore on the southwestern rim of the Pacific seemed eminently advantageous. Rabaul, situated on the eastern end of New Britain, was captured in late January 1942. That April, exploiting the strategic position of Rabaul, the navy sent in the newly formed Twenty-fifth Air Flotilla, which included both the Fourth Air Group, with its squadron of G4M bombers, and the Tainan Air Group, one of the best fighter units in the Japanese naval air service. The Japanese soon extended their control over New Britain and New Ireland, along the coast of eastern New Guinea (and could and should have easily seized Port Moresby on the southeastern coast), before moving down to the northern Solomon Islands. These occupations gave them complete air and naval control over the Bismarck Archipelago and thus provided a springboard for further advances toward Australia or, conversely, a potential barrier ranged on interior lines against Allied counteroffensives toward Southeast Asia. In the spring and early summer of 1942, Japanese naval air power in the southwestern Pacific was at its zenith. Not only was it strategically positioned; its qualitative and quantitative superiority in aircraft and personnel was never again so great. In May 1942, operating from bases at Rabaul and advance fields in Papua New Guinea and in the Solomons, the Twenty-fifth Air Flotilla concentrated its operations over eastern New Guinea in support of the belated attempt to take Port Moresby, an effort that initiated the air war in the southwestern Pacific.

Photo. 7-2. Mitsubishi G4M bombers of the Misawa Air Group over Rabaul Harbor, 28 September 1942

Source: Kōkūshō Kankōkai, Kaigun no tsubasa, 2:91.

But in a strategic oversight of major consequence, the Japanese had done little to capitalize on their advantageous position in the southwestern Pacific by strengthening it. For the next five months, while Japanese naval air forces ranged far into the Pacific and Indian oceans, not a single full-service air base was established south of Rabaul. Then, in the summer of 1942, to protect the flank of the U.S. Australia lifeline, the United States took the initiative in the region, by landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Solomons. These moves set off a six-month struggle for the Solomons that would eventually not only grind down Japanese surface forces but also lead to the destruction of the remainder of the navy’s first-line land-based air groups.23 Slow to recognize the new American threat to Rabaul and the Bismarcks barrier, the navy now redirected the operations of the Rabaul air forces to Guadalcanal in order to neutralize American defenses on the island and to isolate its garrison.24

Yet early in the Solomons air campaign, a critical problem faced by the Rabaul base air force, as it tried to throw in more units to face the growing numbers of American aircraft, was the fact it had too few airfields from which to operate. This could have been rectified even at this point if the navy had been able to dispatch adequate construction resources to the area. But base construction had never been a long suit in the Japanese navy, and the few construction units that existed worked with picks, shovels, and wicker baskets rather than the modern equipment—bulldozers, steam shovels, and metal matting—that could quickly turn a patch of jungle into an airstrip.25 The immediate consequence of this inability to build air bases rapidly was that in the initial critical weeks of the Solomons air campaign, the navy was hampered in the effective use of all the air power it had drawn down from other theaters in Southeast Asia and the southwestern Pacific. It simply had too few places to put it.

Thus, while the American toehold on Guadalcanal and its abandoned Japanese airstrip was still precarious, the Rabaul base air force was unable to get the decisive upper hand in the air campaign. Although on paper it soon had more than enough aircraft to do so, only the Japanese bases at Rabaul on New Britain and Kavieng on New Ireland could accommodate the additional air units that had been flown in, and these bases were far to the northwest of the air combat theater. The advance airfields that the navy did manage to carve out from the jungles between the Bismarcks and the American base at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal were used mainly as refueling stops, and then only when these airfields were sufficiently supplied. Buin, Buka, Kahili, and Shortland Island were eventually developed for offensive operations, but the airfields at Munda and Vila were mostly dirt strips for emergency uses. (Map 7-2.) By the time the navy was able to commit additional base construction resources to the central Solomons, particularly toward the establishment of a major base at Munda, it was too late to save the air campaign, particularly since Japanese air units at Rabaul and Kavieng had to battle U.S. Army and Australian air units operating out of northern Australia and Papua New Guinea.26

Now, in the early autumn of 1942, the Japanese navy made another critical miscalculation. Instead of throwing in both the major surface and air elements of the Combined Fleet to augment the available land-based forces of the Eleventh Air Fleet and to crush the American advance position in the southwestern Pacific at the outset, the navy sent in only its best land-based air units, and those in piecemeal fashion. It soon became apparent, however, that the navy had underestimated American air strength in the Solomons area. In order to deal with the enemy seizure of Guadalcanal, the navy was eventually forced to throw in most of the assets of the Eleventh Air Fleet, which were strung across the length and breadth of Southeast Asia. From the Indian Ocean front the navy pulled in the Twenty-first Air Flotilla; from the East Indies front facing northern Australia, elements of the Twenty-third Air Flotilla were diverted to the Solomons; and from the Marshall Islands far to the east came both flying boats and fighters. The medium bombers of the newly constituted Twenty-sixth Air Flotilla—comprising the veteran Kisarazu Air Group and the recently formed Misawa Air Group—were also brought in to reinforce the Japanese position in the Solomons. All these units were eventually consumed in the ferocious combat with increasingly powerful air units of the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Army Air Forces. By the end of 1942, Guadalcanal had become what an American commander on the scene called a “sink hole” for Japanese naval aviation.27 Moreover, in the navy’s effort to shore up its position in the Solomons, huge gaps were opened in other sectors of Japan’s air defense perimeter, from the Indian Ocean to the central Pacific.28

Map 7-2. The Solomon Islands air combat theater, 1942–1943

Out at sea, two carrier air battles that were an integral part of the struggle for the Solomons—the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in August and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in late October—resulted in the decimation of the last of the navy’s core of elite carrier aircrews. At the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the navy lost the carrier Ryūjō and sixty-one airmen. At the Battle of Santa Cruz, the Japanese suffered the greatest single loss of carrier aircrews to date, 148 aviators. Indeed, the death ride of the carrier air groups at Santa Cruz can be said to mark the demise of the prewar carrier air cadres. Of the aircrews who were lost in that Japanese Pyrrhic victory, twenty-three were section leaders or above or squadron commanders, including Murata Shigeharu, the famed torpedo plane pilot.29 Thus, in four great carrier battles in the first year of the war, Coral Sea, Midway, Eastern Solomons, and Santa Cruz, it is estimated that the Japanese lost a total of 409 carrier airmen, the navy’s best—more than half of the 765 who had participated in the Pearl Harbor operation.30 The Americans too had suffered heavily in these engagements, and for that reason it was nearly two years before another carrier duel was waged in the Pacific.

The consequence of too few advance air bases in the Solomon Islands was that the Japanese navy—there were few Japanese army air units in the southwestern Pacific until the last stage of the Solomons air combat—was obliged to fight an air campaign of attrition at long range, whereas the American enemy based his aircraft literally at the front. The distance between Rabaul and Guadalcanal was 565 nautical miles, some 60 miles further than the distance the Zero fighters on Taiwan had been called upon to fly to the Philippines at the opening of the war. At the time that the navy swept into the Solomons in the spring of 1942, the Combined Fleet had considered the construction of an air base between Rabaul and Guadalcanal, but by the time the Americans arrived, only an emergency air field on Buka Island, north of Bougainville, had been built. Thus, the fighter pilots of the elite Tainan Air Group had to fly three hours to the combat theater, endure the sudden and violent pressures of no more than fifteen minutes of air combat over Guadalcanal, followed by a three-hour return flight home with the possibility of an emergency landing at Buka. (Only the Model 21 version of the A6M, the workhorse of the navy in the first year of the war, could fly all the way to Guadalcanal. The succeeding model, the 32, could not, since its larger engine and added magazines forced a sacrifice in fuel capacity and thus a reduction in tactical radius.) These exhausting operations of more than six hours and 1,000 miles quickly took their physical toll on the fighter pilots who survived the fierce air combat over Guadalcanal and thus accelerated the erosion of the tactical efficiency of the Japanese air campaign. In strategic terms, the failure to establish locally controlled, self-sufficient air bases at the front meant that the navy was unable to provide flexible, responsive air support to Japanese ground and surface forces on or near Guadalcanal, which had come under increasing attack by the Allied enemy. Tactically, it prevented the use of single-engined, land-based bombers whose operational range, with ordnance, did not permit them the round trip from Rabaul to Guadalcanal and back.31

Another difficulty faced by Japanese aircrews in the Solomon Islands air campaign was the slender chance for recovery if their planes were downed or crippled. For the most part, if American aircraft were shot down and their crews able to bail out, they could generally count on parachuting into friendly territory. There was at least a fair possibility, moreover, that they could be picked up by American PBYs detailed for search-and-rescue duty. For Japanese pilots who ran into trouble over the Solomons, the prospects were far more ominous. To begin with, land-based Zero units, unlike their carrier counterparts, were not equipped with radio receivers or transmitters. Their pilots, considering them unreliable and too heavy to justify their installation, chose instead to rely on hand signals. Not only did this arrangement sometimes have serious consequences in combat, it also clearly made it difficult to locate and rescue any pilot who might have crash-landed.32 Most of the Solomon Islands was hostile territory, and while the navy’s flying boats, submarines, destroyers, and patrol craft were always on the lookout for downed aviators, air-sea rescue was far less organized than in the American armed forces. Finally, of course, the Japanese military ethos did not permit capture, and for Japanese pilots, crashing one’s aircraft into an enemy ship, aircraft, or ground facility was preferable to the disgrace of being made prisoner. Such circumstances added to the mounting Japanese attrition rates in the air war over the Solomons.33

Thus, as serious as were the casualties among experienced Japanese navy fliers at the Coral Sea and Midway, it was the air combat over the Solomons that, by the summer of 1943, finally destroyed the combat-effectiveness of Japanese naval aviation as it had developed before the war. The losses suffered by the Tainan Air Group, which included the greatest number of the navy’s fighter aces, among them the famed Sakai Saburō, exemplified this situation. By the time it was ordered back to Japan in November 1942, the Tainan Air Group had been reduced to twenty pilots and ground crew.34

But losses among aircrews did not constitute the only attrition suffered by Japanese naval aviation personnel in the air campaign in the southwestern Pacific. Okumiya Masatake, in the 1930s a pilot aboard the Ryūjō, and in 1943 a lieutenant commander and air staff officer of the Second Carrier Division supporting the air defense of Rabaul, years later recalled his somber impression of the dreadful deterioration of the morale and teamwork of the staffs of the land-based air flotillas (the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth) assigned to defend the base. Exhausted by overwork, drained constantly of officers for combat aircrews, the land-based air staffs in the southwestern Pacific began to disintegrate by late 1943. The capabilities of the air base maintenance personnel also began to shrink severely under the appalling conditions of heat, humidity, poor food, worse medical treatment, and twelve- to twenty-hour workdays, seven days a week. While the navy’s high command attempted to give some attention to the increasingly intractable problem of aircrew attrition, it never came to grips with the increasing enfeeblement of its forward base staff and ground crews.35

The Japanese naval air units also lost the intelligence war in the Solomon Islands air campaign. The Allied intelligence net, composed in varying proportions of radar, communications intelligence, aerial reconnaissance, and ground observation, effectively covered New Britain and the Solomons. For that reason, most offensive operations by Japanese naval air units were reported ahead of time to Allied air forces. Radar and Allied traffic analysis of Japanese radio communications provided some of the information, and the reconnaissance of Allied B-17s and Catalinas, scouting Japanese naval air bases, made more air intelligence available. Particularly harmful to the Japanese cause, however, was the information on their air operations provided by Australian coast-watchers scattered throughout the islands. These observers were often able to radio intelligence to American fighter units several hours in advance of a raid. The Japanese navy had few such assets.36

Under the increasing attrition of the navy’s fighter units, the escort doctrine for Japanese bombers began to unravel. As was described in chapter 5, under the doctrine developed during the China War, the navy’s fighter pilots assigned to escort duty for bomber formations generally flew indirect cover. Usually taking station above the bombers, the fighters were relatively free to maneuver, and if enemy interceptors were encountered, even at a distance, the fighters were free to pursue them. Early in the Guadalcanal air campaign the navy’s land-based fighter groups employed this method. But a recurring problem, the same one that had occurred in the China air war, was that this too often left the bombers uncovered. As the number of Allied fighters increased and the losses of Japanese bombers mounted, the navy’s fighter groups were obliged to switch to close-in, direct cover tactics (chokuen sentō). But this tactic put a heavy psychological burden on the fighter escorts, since it was mostly passive and allowed few pilot victories. Moreover, the pilots involved in such a mission did not always carry out their assignments to the letter, through either muddled instructions of the escort leader, misunderstanding of his orders by his subordinate pilots, or simply inadequate flying and combat skills on the part of these pilots, any one of which causes could leave the bombing force unescorted and without cover. Indeed, all of these elements seem to have played a part in the destruction of Admiral Yamamoto’s G4M in 1943.37

I come now to the two most important reasons for the collapse of the Japanese navy’s air campaign over the Solomon Islands: the growing qualitative disparity between Japanese and American aircrews, and the appearance of Allied aircraft superior in performance to the Zero. At its higher levels, the Japanese naval air service was slow to grasp these new realities. Certainly little was done to exploit incoming intelligence concerning new U.S. air technology and tactics. On their part, American forces did this very quickly. Information concerning Japanese fighter aircraft and tactics was disseminated rapidly and widely. As we have seen, even as early as the Battle of the Coral Sea, American fighter pilots flying F4F Wildcats had begun to take the measure of the Zero, and information about the aircraft was widely disseminated throughout the combat theater.38

Salient among the lessons learned by American fighter pilots was the imperative of not letting the Zero fight in its preferred environment: the relatively low-altitude low-speed dogfight. In Southeast Asia early in the conflict many an Allied airman had learned to his cost that the Zero’s maneuverability and the skill of Japanese pilots in exploiting it in tactics like the hineri-komi maneuver gave the Japanese a deadly advantage under these conditions. One American recalled the seeming chaos of a Japanese fighter formation that came on like a swarm, using random maneuvers to entice their opponents into acrobatic duels, a potentially fatal course for any American pilot who tried to follow them.39 But the advent of second-generation American fighters with their superior speed, climb, and high-altitude performance, and the appearance of American pilots wise to the strengths and weaknesses of their opponents, came to marginalize the maneuverability of the Zero and the predilections of the pilots who flew it.40 Pilots in the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Army Air Forces began to use their combat skills in the cockpits of larger, faster, stronger aircraft: the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, the Vought F4U Corsair, and the Grumman F6F Hellcat. American emphasis on individual gunnery, deflection shooting, the new “finger four” flight formations, and tactics like the Thach Weave began to have a telling effect in air combat.41 Against these aircraft, and the techniques and tactics of the American pilots who flew them, the famed nimbleness of the Zero was often of little avail, although on those increasingly rare occasions when it fought on its own terms, it still was a deadly opponent.

But the Zero was not the only navy aircraft whose design and construction made it a growing liability. The Aichi D3A (“Val”) dive bomber, which had caused such havoc in the Indian Ocean in the spring of 1942, by late fall of that year was but a slow-moving and weakly protected target for enemy fighters, and the Nakajima B5N (“Kate”), the terror of Pearl Harbor, was not much better. The aircrews of the Mitsubishi G3M (“Nell”) and G4M (“Betty”) bombers that had ranged so far over Chinese skies and Southeast Asian waters now found that their planes too often became fiery deathtraps under the guns of American aircraft with heavier armament, greater armor, and better climbing and diving speeds.

Undoubtedly, however, it was less the inferiority of aircraft than the severe drop-off in the quality of aircrews that accounted for the mounting Japanese losses in the Solomons campaign.42 Certainly a leading cause of the navy’s defeat in the Solomons air campaign was its inability to replace aircrews effectively and in sufficient numbers. There was no regular system of rotation of individual personnel, as in the American air services. Instead, veteran air groups were simply used up, through death, wounds, disease, or physical exhaustion, to be replaced by new units that over time were increasingly composed of aircrews of less training and skill. Moreover, even if there could have been individual rotation, as operations became extended there were never enough reserves to permit the rotation back to Japan of those who had been longest in combat. “They won’t let you go home unless you die” (shinanakute wa kaeshite moraenai) became a common and bitter phrase among Japanese navy pilots in the southwestern Pacific. For this reason, combat fatigue was a contributing cause of the continuing high attrition rate among older pilots.43

Compounding the effect of the attrition rate on the combat-effectiveness of Japanese air units was the problem of insufficiently trained personnel. While there were plenty of younger pilots to replace those who were older and highly skilled but who had succumbed to combat or combat fatigue, they lacked the necessary skills and experience. Thrown into combat without these qualities, they were lost more rapidly, and the relationship between inadequate training and attrition became a downward-spiraling vicious circle.44

In the autumn of 1942 the American intelligence report quoted earlier provided a blunt summary of the extent to which the overall competence and combat proficiency of Japanese naval aircrews had deteriorated. The report asserted that the inexperienced crews

made glaring tactical mistakes, unnecessarily exposed themselves to gunfire, got separated and lost mutual support, and at times seemed completely bewildered. Both bomber and fighter pilots ceased to display the aggressiveness that marked their earlier combat. Bombers ceased to penetrate to their target in the face of heavy fire, as they had formerly done; they jettisoned their bombs, attacked outlying destroyers, gave up attempts on massed transports in the center of a formation. Fighters broke off their attacks on Allied heavy and medium bombers before getting within effective range, and often showed a marked distaste for close-in combat with Allied fighters.45

One effect of the deterioration of air combat skills and experience was the disintegration of the cohesion of Japanese tactical formations, particularly the three-man shōtai. I mentioned in the previous chapter the empathy that was said to exist in the immediate prewar years between pilots who constantly trained together, a “sixth sense” that supposedly allowed them to think and act together in combat when not actually in communication by sight or voice. But by the end of 1942 this extrasensory pilot-to-pilot communication was gone, if it had indeed existed, and the tactical formations it supposedly had held together began to fall apart.

Directly related to this decline in combat capability was the vulnerability of Japanese aircraft. Throughout the war, novice American pilots also made mistakes in combat, but on many occasions the sturdy construction of their aircraft (plus armor and self-sealing tanks) allowed them to survive and fight again, and more skillfully, another day. All too often, the first mistake of a Japanese novice was his last.46

Even when the navy was able to pull an air group out of operations for training in a rear area, the shrinking nucleus of capable, combat-tested pilots to conduct that training meant a sharp drop-off in its effectiveness. This situation affected both carrier- and land-based air groups. During the Solomons air campaign, carrier aircrews were land-based at Rabaul and the Solomons on several occasions to augment land-based air groups, most notably during operations “I” and “RO” (see below). The losses they suffered simply served to cause further deterioration in the quality of what should have been the navy’s best aircrews—the carrier pilots of the fleet.

With Guadalcanal in their hands, the Allies stepped up air attacks on Japanese positions in the northern Solomons, in eastern New Guinea, and on the defense barrier that the Japanese were trying desperately to establish along the Bismarck Archipelago. The growth of Allied aerial might and the waning ability of Japan’s air forces in the southwestern Pacific to respond to its attacks were dramatically evident in the slaughter, by American land-based bombers and fighters, of Japanese warships and transports attempting to transit the Bismarck Sea in March 1943. Determined to hold back further enemy blows by counter air offensives against American shipping and advance bases in the southwestern Pacific, Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku, commander of the Combined Fleet, took personal command at Rabaul of Operation “I.” This counteroffensive, directed first against Guadalcanal and then against Allied positions in eastern New Guinea, assembled both land-based air groups and carrier-based aircraft of the Third Fleet brought in from Truk. Together they should have numbered about 700 aircraft, but such was the poor state of the operational maintenance of the navy’s aircraft at this point in the war that only 350 could be mustered.47 Still, the raids collectively comprised the biggest air operations since the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Yet once again, despite the ferocity of the attacks, the operation was worn down by Allied air superiority, and the results were far less than Yamamoto believed at the time, especially in comparison with the heavy losses in aircraft (over fifty), which the Japanese navy could no longer afford. Worst of all, the inroads of American intelligence into the navy’s plans for air operations were shockingly demonstrated by the aerial ambush of Admiral Yamamoto, whose aircraft was shot down while making an inspection tour of the front lines upon the conclusion of Operation “I.” Okumiya Masatake, who attended the study conference at Rabaul that evaluated the operation, later recalled the general sense of gloom that attended the conference and the belief that American aircraft were now regularly matching and exceeding Japanese aircraft in performance as well as in numbers.48

Up until mid-1943, Rabaul was the main base for Japanese aerial offensives in the southwestern Pacific. In the autumn of that year, Allied air forces, led by American heavy bombers—B-17s and B-24s—turned such relentless assaults against Rabaul that, far from remaining a springboard for the southward expansion of Japanese air power, it became a stronghold under siege. Determined to hold on to the base as the linchpin of the Bismarcks barrier, Admiral Yamamoto’s successor, Adm. Koga Mineichi, attempted to keep Rabaul supplied with sufficient fighter aircraft, but these were successively destroyed in the futile defense of the redoubt. Thus, in the words of a recent study, the Japanese air defense of Rabaul and its three airfields became a “giant aerial meat grinder” that devoured both fighter aircraft and what was left of the navy’s best fighter pilots.49

In early November, in a reprise of Yamamoto’s ill-fated Operation “I,” Koga concentrated at Rabaul all the available land-based aircraft of the Eleventh Air Fleet, along with the entire aircraft strength (approximately one hundred planes) of the three carriers (Zuikaku, Shōkaku, and Zuihō) of the Third Fleet at Truk for attacks on the U.S. carrier forces harassing Rabaul. At the start of this Operation “RO,” Koga had on hand approximately 365 aircraft. By the time it had ended, he had lost over two hundred aircraft, both to the air defenses of the American task group and to the American aircraft over Rabaul, without having caused significant damage to the besiegers.50 So severely did “RO” reduce the pool of competent carrier pilots in the Combined Fleet that Koga could not put up any air defense of Tarawa in the Gilberts when the United States Marines stormed ashore on 20 November.

Meanwhile, the Allied air assault on Rabaul, now based on Allied airfields in the Solomons and eastern New Guinea, continued apace. By the end of January 1944, after the loss of some 250 aircraft in an attempt to defend it, Rabaul was finished as an effective air base, and the coup-de-grâce to the navy’s air power in the southwestern Pacific was delivered in February, when an American carrier task force destroyed the navy’s remaining air reserves on Truk, far to the rear of Rabaul. After this disaster, Admiral Koga ordered Rabaul abandoned, the majority of the remaining naval air units flying out on 20 February, leaving only a few aircraft to conduct aerial guerrilla warfare against the Americans storming up from the Solomons. Yet the enemy chose not to expend the men and materiel to take this once most formidable Japanese base from its enfeebled garrison. Bypassed but frequently bombed, Rabaul was left to wither on the vine.51

THE END OF CONVENTIONAL JAPANESE CARRIER AVIATION, 1943–1944

By the beginning of 1944, then, the land-based element of Japanese naval air power in the southwestern Pacific had been shredded. Yet on paper it would seem that by the late spring of 1944 the Japanese navy, through desperate efforts, had been able to build its air power back up to nearly the levels at which it had opened the Pacific War. True, the majority of the carriers with which Japan had opened the war had been sunk, and the few remaining prewar aircrews had been thrown into the furnace of combat in the central Pacific and consumed by early 1944. But wartime construction added new carriers to the fleet, the navy rushed new aircrews through its training programs, and the General Staff established a new carrier command, which attempted to match the new tempo and scale of carrier warfare being waged by the enemy. The navy’s First Mobile Fleet was organized on 1 March 1944, supposedly similar in concept to the United States Navy’s task forces now operating in the Pacific. Now acting as the central battle force of the Japanese navy, it was built around its nine carriers, including the new heavily armored Taiho. On their decks were crowded new, more powerful and more sophisticated aircraft types, including the Nakajima B6N torpedo bomber and the Yokosuka D4Y1, the fastest dive bomber of World War II.

In theory, therefore, the First Mobile Fleet was the second most powerful carrier force in the world. But in fact, shortages in every required element of this Japanese task force made it a feeble reflection of the original concept (see below). Of these deficiencies, none was worse than that of its air groups, which were filled with young pilots shockingly ill prepared for battle. Before the war, the average length of the navy’s pilot training had been three and a quarter years, and the rigor of that training was discussed in chapter 2. By late 1944, every U.S. Navy pilot had undergone over two years of training. By June of the same year, the Japanese pilots who manned the air groups of the First Mobile Fleet had an average of only six months of training, and some had only two or three months. In the urgency of the time, as their instructors struggled to teach the tyros just to fly and shoot, the fine points of fighter combat were cast aside. Navigational training ceased altogether, and pilots were simply instructed to follow their leaders into action. But those leaders themselves were now correspondingly less experienced and prone to make mistakes unthinkable for their predecessors in 1941–42.52

This deplorable condition of air training was aggravated by a number of other elements. One was the fact that the new aircraft types—such as the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden fighter, the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei carrier bomber, and the Nakajima B6N torpedo bomber—were far more demanding of pilot skills than their predecessors. In the hands of inexperienced pilots they became deathtraps, as demonstrated by the increasing number of fatal accidents in the navy’s air units. Because of unanticipated technical delays in equipping the navy’s air groups with these latest aircraft, there was little time to train inexperienced aircrews in either their great combat potential or their dangerous quirks.53 By 1944, moreover, the fuel problem, always tight for the Japanese navy and only temporarily relieved by the conquest of Southeast Asian oil fields, had really begun to bite. Aviation gas being in short supply meant that training and practice had to be sharply curtailed. There was even a shortage of airfields for training. Tawi-tawi, at the extreme end of the Sulu Archipelago, chosen by the First Mobile Fleet as its advance base, did not have an airfield, and the fleet’s carrier pilots, apparently unable to use the carrier decks for training and practice, were inactive before the last great battle in which they were to take part.54

Despite these deficiencies, the Japanese navy remained confident of its ability to launch a smashing aerial offensive against the United States Navy’s Task Force 58 when it approached the Marianas as part of the American offensive to break through Japan’s defensive barrier in the central Pacific. In the plan for the navy’s “A” operation, the main force to be used would be its shore-based air units rushed to the Marianas—Guam, Saipan, Tinian, and Rota—from which they were to launch mass attacks to cripple the American carriers. The land-based air assault units would be followed by attacks by the carrier aircraft of the First Mobile Fleet. Supposedly, with a 200-mile advantage in range over their American counterparts, the Japanese carriers would remain at a secure distance from enemy retaliation. The Japanese carrier aircraft could thus strike the enemy carriers, land on island bases in the Marianas, refuel, and launch a second attack on the enemy before returning to their own carriers.55

So it was planned. But the resulting Battle of the Philippine Sea, 19 June 1944, the last great carrier encounter of the Pacific War, turned into an air disaster that demonstrated the dramatic decline in Japanese naval air power since the glory days early in the war. The specific moves of the campaign lie beyond our concerns. Suffice it to say that American carrier fighters obliterated the Japanese land bases before their air groups could get into the fight, and Admiral Ozawa and the First Mobile Fleet plunged into his assault on the American carriers without the promised land support. In the ensuing Japanese attacks, the slaughter of Ozawa’s carrier air groups was so great—and, by American standards, so easy—that it became known by the victors as the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

The reasons for the debacle were twofold. On the American side, beyond the question of numerical superiority, which was significant, there were a number of spectacular advances: first, radar and its contribution to long-range interception of enemy air attacks; second, faster, more powerful, more rugged aircraft than ever before; third, the improvement in tactical formations for carrier battle; fourth, the superb performance of the combat information centers on all the major fleet units; and fifth and above all, the aggressiveness and cool professionalism of the superbly trained American aviators.

The Japanese side presented an exact opposite, particularly in the performance of its aircrew. The Japanese pilots orbited ineffectively around the American carriers at a distance of 100 miles at the start, losing the one chance they had for victory: a quick, violent strike regardless of loss. Many of the fighter pilots seemed content to stay out of the action entirely. In contrast to the outstanding discipline of the Kanoya Air Group bombing crews when they destroyed the Repulse and Prince of Wales off Malaya in December 1941, the Japanese dive and torpedo bombers at the Philippine Sea failed to keep their formations and, separating, lost all chance of coordinated attack. The aim of the Japanese carrier pilots was so off the mark that one American aviator declared contemptuously after the slaughter that they “couldn’t hit an elephant if it was tied down.”56

In his masterful history, Samuel Eliot Morison provided a more magnanimous verdict, though one no less devastating in its appraisal of the fundamental cause of the Japanese defeat:

Ozawa may be said to have conducted his fleet well. The Japanese plane searches kept him fairly in touch with the movements of Task Force 58 for twenty-four hours or more before Spruance knew where he was. [He] avoided the usual (and always disastrous) Japanese strategy of feint and parry; he kept his inferior force together and gave battle at a distance that prevented his enemy from striking back immediately. His handling of the fueling problem, in view of the shortage of oil and scarcity of tankers, was masterly. But all this availed him naught because his air groups were so ill-trained. Ozawa had fine ships and good planes, but his aviators were weak-winged through inexperience, and land-based air failed him completely.57

When the battle was over, in addition to the destruction of a large number of its land-based air groups, the Japanese navy had lost its last carrier air groups and had failed either to damage Task Force 58 or to halt the American drive through the Marianas.

The utter Japanese defeat at the Battle of the Philippine Sea marks the chronological terminus of my discussion of Japanese naval air power in World War II. After it was over, the Japanese navy never again launched a significant effort to contest the American hegemony of the skies over the Pacific. By war’s end, save for the old Hōshō, all of her once proud carrier forces either lay at the bottom of the grand abysses of the Pacific or were careened, abandoned, and useless in the shallower waters of Japanese home ports.58 (Photo. 7-3.) The last desperate effort by Japanese naval air units to stem the Allied tide in the western Pacific, the organization of the “special attack” (tokkō) corps—the kamikaze units, as they are best known in the West—was largely directed toward American surface units. In any event, the suicide tactic was simply not contemplated as a significant element in prewar air combat doctrine in the Japanese navy and therefore has little relevance to the scope of this work. At war’s end, there were approximately fifty-nine hundred aircraft left on the navy’s homeland airfields, but with little fuel to fly them and a dwindling number of pilots who could fly them more than one way. Within months, as the occupation forces began dismantling what was left of Japan’s military machine, even these machines had been turned by American bulldozers into hundreds of acres of crumpled wings, propellerless engines, and overturned fuselages.59 (Photo. 7-4.)

REFLECTIONS ON THE DESTRUCTION OF JAPANESE NAVAL AIR POWER

The grand causes of Japan’s catastrophic collapse have been illuminated by a number of magisterial works on World War II. In addition, the late David Evans and I dealt more specifically with the nation’s defeat at sea in the last chapter of our volume on the prewar Japanese navy. I now sharpen my focus on the causes of the destruction of Japanese naval air power, 1942–44. While the reasons are multiple, a few general categories stand out: first, the failure of the navy to anticipate the kind of air combat it would be obliged to wage; second, once in the new kind of air war, the failure to make the right decisions to deal with its realities; and third, the inability of Japanese industry and technology to support Japanese naval aviation against the emerging numerical and qualitative superiority of American air power.

Photo. 7-3. The carrier Amagi capsized in Kure Harbor, 8 October 1945

Source: Fukui, Shashin Nihon kaigun zen kantei shi, 1:336.

In prewar Japanese strategic-planning documents there were numerous references to the necessity to prepare for a war of attrition against the United States. But in addition to underestimating the ability of the United States to force the pace of attrition, the Japanese navy’s strategy to wage such a war was based on a disregard of the fundamental reality of the Pacific. The navy’s plans called for the creation of a great chain of island air bases that would form a defensive barrier around the nation’s empire of conquest in the central and southwestern Pacific against any American counteroffensives to retake it. Shifting the navy’s long-range bombers from one to another of these “unsinkable carriers,” as Yamamoto had viewed them, the navy had believed that it could launch preemptive attacks against any enemy advance.60 Here, the navy clearly misjudged the vast distances over which it would have to fight. The distances between Japanese bases throughout the western and southwestern Pacific proved too great even for the longest reach of its land-based aircraft, and thus it proved impossible to provide the flexible defense that Yamamoto had envisioned. And thus, one by one, without substantial help from the nearest air garrisons, the navy’s air bases fell before the American amphibious tidal wave.

Source: Mikesh, Broken Wings of the Samurai.

The unrealistic quality of the navy’s plans for winning an extended war is also apparent in its personnel policies and aircraft design priorities. The creation of a small but elite pool of naval aviators with no substantial reserve to back it up, nor any training program in place with which to do so, speaks of the mistaken assumption of a short, victorious conflict. That assumption is confirmed by the design and production of aircraft that provided scant means to protect the personnel who flew and fought in them and thus did nothing to preserve that precious elite once the air war of attrition began.

I have touched upon the navy’s failure to create adequate reserves of trained aircrews at several points in these pages. With half of the naval air arm insufficiently trained at the opening of the Pacific War, it was difficult to fill the needs of front-line air groups with fully qualified personnel as its elite formations were steadily ground down. By stripping the carrier air groups of both capable leadership and the best pilots, the land-based groups were kept reasonably combat-ready into the spring of 1943. But by that time land-based aircrews had themselves been decimated, with no effective on-site training reserve to replace combat losses. The consequences of these training policies were ultimately fatal. Once the navy recognized that it was far better to have lots of competent pilots than a handful of outstanding ones, it was too late. The terrible shredding in combat of the navy’s top air units, the ever-increasing need for their replacement, and the decreasing time and fuel available for adequate training to provide such replacement had by late 1943 left the navy with little but the greenest trainees, who were quickly sacrificed in the fire of combat.61

American air personnel policies before and during the Pacific War stood in sharp contrast. The American emphasis on training far greater numbers of aviators, albeit at a somewhat lower standard of performance, the assignment of training units aboard aircraft carriers, and the provision of aircraft that offered aircrews greater lifesaving protection gave American aviators an overwhelming advantage in air combat by the end of 1942. In sum, as Fuchida Mitsuo and Okumiya Masatake concluded in their account of the Battle of Midway, the Japanese naval air service “failed to realize that aerial warfare is a battle of attrition and that a strictly limited number of even the most skillful pilots could not possibly win out over an unlimited number of able pilots.”62

It has been commonplace in Western accounts to view the Japanese tradition as indifferent to the expenditure of human life in battle. Specifically, it has been argued that the Japanese navy undervalued the lives of its few precious aviators. Yet there were elements complicating this picture. One must understand that the pilots themselves, embracing a Bushido ethos, did not want armor and self-sealing fuel tanks on their aircraft, since such additions seemed to imply a selfish concern for their own survival. There was also an intangible, that of the stoicism and gaman (perseverance) that pervaded Japanese society. Japanese were simply ready to put up with combat conditions that in the West would have been considered intolerable.63

As we have seen, the navy pursued aircraft designs in which safety factors—armor, self-sealing gas tanks, structural integrity—that might have saved the lives of pilots were sacrificed for greater performance, speed, and maneuverability. Once the harsh lessons of the China and Pacific wars had been absorbed, the inability of the navy to provide armor and self-sealing tanks was due to a combination of bureaucratic inflexibility and a weak industrial infrastructure rather than to any opposition to these features in themselves.

Of course, as Eric Bergerud reminds us, the devastating attrition rate for the navy’s aircrews was also due to “operational”—that is, noncombat—losses that affected Japanese and Allied aircrews alike. Erratic and often violent weather, unfamiliar and often mountainous terrain, navigational mistakes over the ocean, primitive and often bomb-damaged runways, aircraft fatigue, pilot error, and mechanical failures—omnipresent dangers that confronted the Allies as well—took a horrendous toll of Japanese aircraft and aircrews. But for Japanese aircrews the 1,000-mile round trip from Rabaul to Guadalcanal and back posed far greater risks of dangerous weather and navigational error than their enemy counterparts based at Henderson Field and other American bases in the Solomons.64 Moreover, the Japanese navy, while it made every effort to rescue downed pilots, never developed anything like the Allied system of sea rescue.65 Although the naval air service actively rotated pilots early in the war, after the major pilot losses at Guadalcanal the rotation system began to break down.

Moreover, it was not just the decline in the quality of aircrews that accelerated the erosion of Japanese naval air power in the Pacific. Heavy losses in trained ground crews also weakened the navy’s air groups. I have said that the most significant personnel losses at Midway occurred not in fighter cockpits but among trained maintenance personnel who went down with the four carriers. Similarly, the loss of skilled ground crews, often abandoned to their fates when the navy evacuated remaining aircrews from islands under siege, substantially weakened the land-based air groups.66

In the southwestern Pacific, the problem of distance was more strictly logistical. Wastage—not just through combat but through accident, the wearing out of equipment, corrosion due to humidity and salt air, and obsolescence of equipment—is an inherent problem of naval air war. To keep aircraft combat-ready requires reasonably effective logistical services. But in the grinding Solomons air campaign the Japanese naval air arm simply lost the battle of maintenance and supply. Failure to supply land-based air groups with sufficient aircraft early in this stage of the Pacific War meant that they went into battle with forces that were too slender, and for that reason accomplished little and missed favorable opportunities at the outset of the campaign. Later, the extreme distances between the homeland and the fighting front made it difficult to make up for these missed opportunities. Rabaul, the main base from which the naval air service waged the campaign, was some 2,400 miles from the Japanese homeland. This distance proved a hindrance to a steady and continuing supply and maintenance of front-line land-based air units because of weaknesses in the navy’s logistical system. Central to the problem was the fact that the navy’s air arm seems to have had no smoothly functioning system of ferrying heavier replacement aircraft—twin-engined bombers and flying boats—to Pacific combat theaters. It was obliged to detail combat aircrews back to Japan to pick up replacement aircraft and stage them through island bases to front-line units. Fighters and smaller aircraft were initially crated and sent to combat zones by cargo vessels or carriers, though later they too were flown out, usually from Truk.67 As the number of skilled pilots decreased, green pilots often crashed the aircraft they were ferrying, further reducing the number of planes available.

But supply means more than just the availability of additional aircraft. Air war requires constant maintenance and repair, and the number of serviceable aircraft available to an air unit at any given time will greatly depend on the level of maintenance available to keep the aircraft flying. Here the Japanese naval air service fell down badly. While each air group was staffed with its own maintenance personnel, they were capable of undertaking only routine maintenance and simple repairs. Major or more complicated repairs proved difficult, in large part because of the trouble of dispatching skilled technicians from rear-area repair facilities and of sending damaged aircraft and equipment back to those same facilities. Moreover, just as with flight personnel, the average quality of ground crew deteriorated over time, thus lowering the serviceability rate and further compounding the problem of maintaining adequate numbers of aircraft and crews.68

Constant maintenance also requires a steady flow of supplies, particularly spare parts. For the first year of the Pacific War the production of parts, engines, weapons, and radios for the navy’s air groups was more than adequate.69 The problem of aviation ordnance was serious, however. Production of aircraft armament at the outset of hostilities was generally 80–90 percent of orders and use, depending on the type of weapon. Though the navy had more than adequate stocks of bombs, on the eve of the war it had on hand only 10–30 percent of anticipated needs in 20-millimeter aircraft cannon shells and Type 91 aerial torpedoes. Through crash conversion of industrial facilities from production of surface naval ordnance to the needs of naval air units, interruption of the flow of aviation ordnance to those units was prevented after the opening of hostilities.70

But as the naval air arm’s area of operations expanded in the first six months of the war and distances between the Japanese islands and the Pacific combat theaters greatly increased, the transportation of ordnance and supplies became a major problem, particularly in situations of urgent need. Then the naval air service began to pay the price for its extremely limited air transport capacity. Not only were there too few transport aircraft available, but there was also a limited number of air transport personnel with sufficient skill to undertake efficient transport loading and to prevent breakage and wastage en route to the combat theater. For that reason, most bombs, torpedoes, ammunition, and fuel were supplied to each land-based air group by maritime transport, but since this means was quite limited even before the destruction of the Japanese transport fleet by the American submarine campaign, the allocation of supplies to advance air bases increasingly became a matter of severe prioritization.71

It was only in the area of aviation fuels that the Japanese naval air service felt no problem in supply until 1944. During 1942 the amount of oil from the Netherlands East Indies was greater than anticipated, as the facilities damaged or destroyed in the conquest of the Dutch oil fields were quickly repaired. Moreover, the American submarine campaign against the tanker routes from the Indies to the Japanese homeland had not yet begun to make serious inroads in supply. But if the supply of aviation fuels was greater than anticipated, so was consumption. At the outbreak of the war, the navy had believed that it had stocks adequate for two years of combat. But the great carrier battles of 1942 and the grinding air campaign in the southwestern Pacific had devoured an enormous amount of aviation fuel, and the reduction in stocks that had occurred by the end of 1943 was compounded by the death grip that the Allies began to apply to Japanese tanker transportation by 1944. By the latter part of that year the navy’s aviation fuel situation had become so desperate that it began investigating the possibility of extracting aviation fuel from pine roots.72

Linked to the question of transport and supply was the paucity of advance air bases, which in turn was created by the navy’s inadequate civil-engineering capacity, a matter touched upon earlier. In the spring of 1942 the advances of the Japanese army and navy simply outran the ability of the primitively equipped construction units to build an adequate network of new bases quickly. For the most part, the navy’s land-based air groups were obliged to use Allied airfields captured in the first several months of the war. But these were few in relation to the numbers of aircraft needed to conduct the offensive operations that might have continued to keep Allied forces off balance. In contrast, the ability of the United States Navy’s “Sea-Bees” to create airstrips almost overnight gave Allied air forces a devastatingly longer reach.

The origin of nearly all of these dilemmas for the Japanese naval air arm can be traced back to the navy’s assumption that it would fight a short, decisive war. In such a conflict, few of these problems would have been critical. As it was, the extended conflict that Japanese naval aviation found itself obliged it to fight exhausted its airmen, destroyed its best aircraft, and overtaxed its facilities and resources.

If the catalogue of failures to anticipate the nature of an air war in the Pacific was fundamental to the navy’s defeat in that conflict, so too were the collective demonstrations of the navy’s inability or unwillingness to make the necessary changes once the war had begun. The first of these changes should have been recognition, at the very top of the naval high command, that the first six months—indeed, the first month—of the Pacific War had proven beyond doubt the dominance of air power over the big-gun capital ship. Such a clear-headed recognition should have resulted in an early decision to abandon the concept of the great and supposedly decisive gun duel at sea and, flowing from that decision, a decisive step to reorder the basic force structure of the Japanese navy.

In a thunderclap, the Japanese navy itself had brought such a realization and such a decision to the United States Navy in the opening hours of the war. At Pearl Harbor the obsolescent American battle line had been critically disabled, thus freeing the United States Navy from its reliance on the capital ship and from whatever lingering faith it might have had in its preeminence. Air power, both land- and carrier-based, became the focus of innovative American tactical thinking and the recipient of a major portion of American industrial output.

In contrast, the Japanese navy was slow to give up its prewar big-gun/big-ship convictions. On the eve of the Pacific War, with the great increase in the performance of aircraft, air power advocates in the Japanese navy like Inoue Shigeyoshi had argued that aviation was now the dominant arm in naval warfare, and in the first few months of the conflict it was air power that scored the most dramatic and crushing victories. These should have been enough to guarantee that the locus of naval decision had indeed changed. Yet the Japanese navy’s high command had been reluctant to discard its conviction that the battleship was the supreme arbiter at sea and that aviation’s subsidiary role was to support the battle line. The Battle of Midway demonstrates this reluctance. On the one hand, after the loss of its four carriers, Yamamoto recalled the strike force, despite the fact that it included some of the world’s most formidable battleships. This reluctance to wager his capital ships against the two remaining American carriers in daylight seems to have been Yamamoto’s homage to air power. On the other hand, in the navy’s major reorganization of its fleets after Midway, only the Third Fleet was to be a carrier force, and the purpose of that fleet was to provide protective cover over the battle line.73

In other words, while the Japanese navy’s recognition of the tremendous power of aviation may have been deepened after Midway, it did not go much beyond the decision to create superior air power. To be fair, this failure to act upon the realities of the air power revolution stemmed from the fact that it was beyond the nation’s industrial capacity to produce adequate numbers of both warships and aircraft. One can argue with twenty-twenty hindsight that a bold decision should have been made to limit warship construction severely and go flat out for air power, particularly the production of heavy land-based bombers. But because ships were also badly needed, this proved impossible.74

The durability of the grip of the big-gun/big-ship orthodoxy on Japanese naval thinking far into the Pacific conflict had another unfortunate consequence: the failure to give airmen substantial authority over the strategy and conduct of the navy’s air war.75 One must remember that in no other navy, not even the United States Navy, were land-based air elements so much an element of naval power. A look at the administrative organization of the Combined Fleet (Fig. 6-6) shows how clearly its land-based air groups were integrated into it. Yet, as was mentioned earlier in these pages, few qualified aviators had high-ranking positions within either the Combined Fleet or the navy’s high command in Tokyo (the General Staff, the Navy Ministry, or any of the navy’s semiautonomous bureaus and departments). Yamamoto Isoroku was the single most important exception, but his orientation toward air power was far less radical than that of Inoue Shigeyoshi, who was not a qualified aviator and whose influence was far smaller. Thus, throughout the war most of the navy’s decisions concerning air operations were made by men whose experience and viewpoint had to do with capital ships, not with air power.76

One can think of a number of instances in which having airmen in command might have made a difference in decision making. One was the failure of Admiral Nagumo to authorize a third strike against Pearl Harbor that would have had the fuel storage tanks as a prime objective. Had the senior aviators in Nagumo’s command been able to persuade their nonaviator commander to launch a final attack on this objective, the results might well have caused a military setback to the United States far beyond the crippling of the aging capital ships of the Pacific Fleet.77

It seems hardly possible that airmen in command positions in Tokyo would have been as neglectful of the health and morale of the navy’s front-line land-based air units in the southwestern Pacific and the necessity to work out a rotation system for individual airmen that would have permitted new and inexperienced personnel to be gradually integrated with veteran aircrews. Japanese naval aviators may have brought their own prejudices and misperceptions to the air war, but they were infinitely more aware of the realities of aerial combat than the naval brass in Tokyo—mostly trained in surface warfare—who directed the air strategy from afar.78