Recurrent hip area pain in an adult

![]()

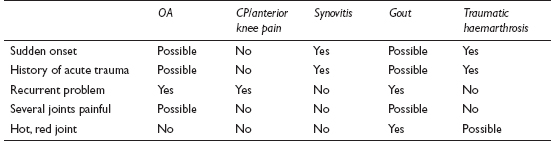

This is a very common problem in primary care. Usually, there are few physical signs, although occasionally a genuine monoarthritis with all the classical signs of inflammation will present. Overall, the most likely aetiological factor is trauma, though other conditions may already affect a joint. In the elderly, an exacerbation of osteoarthritis is common; this condition may also cause multiple joint pain. The knee is probably the single most frequently affected joint.

![]()

COMMON

acute exacerbation of osteoarthritis (OA)

acute exacerbation of osteoarthritis (OA)

traumatic synovitis

traumatic synovitis

gout/pseudogout

gout/pseudogout

chondromalacia patellae (CP) and other anterior knee pain syndromes

chondromalacia patellae (CP) and other anterior knee pain syndromes

traumatic haemarthrosis (e.g. after cruciate ligament injury)

traumatic haemarthrosis (e.g. after cruciate ligament injury)

OCCASIONAL

fracture

fracture

Reiter’s disease

Reiter’s disease

psoriatic arthritis

psoriatic arthritis

rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

patellar tendinitis, Osgood–Schlatter’s disease

patellar tendinitis, Osgood–Schlatter’s disease

RARE

septic arthritis (SA)

septic arthritis (SA)

haemophilia

haemophilia

local tropical infections (e.g. Madura foot (mycetoma pedis), filariasis)

local tropical infections (e.g. Madura foot (mycetoma pedis), filariasis)

malignancy (usually secondary)

malignancy (usually secondary)

avascular necrosis

avascular necrosis

recurrent joint subluxation

recurrent joint subluxation

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, uric acid, X-ray, joint aspiration (in monoarthritis of large joint).

SMALL PRINT: rheumatoid factor, clotting studies/factor VIII assay, arthroscopy.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in infection, systemic inflammatory conditions; Hb may be reduced in the latter.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in infection, systemic inflammatory conditions; Hb may be reduced in the latter.

Uric acid: once attack has subsided, useful to add weight to clinical diagnosis of gout (especially if considering treatment with allopurinol).

Uric acid: once attack has subsided, useful to add weight to clinical diagnosis of gout (especially if considering treatment with allopurinol).

Rheumatoid factor may be useful if symptoms suggest possible RA.

Rheumatoid factor may be useful if symptoms suggest possible RA.

X-ray: essential if fracture suspected. May also reveal OA, avascular necrosis, malignancy and help to distinguish between RA and psoriatic arthritis.

X-ray: essential if fracture suspected. May also reveal OA, avascular necrosis, malignancy and help to distinguish between RA and psoriatic arthritis.

Sterile aspiration of joint fluid: to look for pus (septic arthritis), blood (haemarthrosis) and crystals (gout/pseudogout).

Sterile aspiration of joint fluid: to look for pus (septic arthritis), blood (haemarthrosis) and crystals (gout/pseudogout).

Clotting studies/factor VIII assay: if haemophilia a possibility.

Clotting studies/factor VIII assay: if haemophilia a possibility.

Arthroscopy: may be required urgently in secondary care if trauma has resulted in a haemarthrosis.

Arthroscopy: may be required urgently in secondary care if trauma has resulted in a haemarthrosis.

Autoimmune blood tests can be misleading in possible arthritis. The diagnosis should be clinical; blood testing simply adds weight and prognostic information to the clinical assessment. Positive tests can be found in normal patients – beware of inappropriately labelling an insignificant problem as a significant arthritis on the basis of a blood test.

Autoimmune blood tests can be misleading in possible arthritis. The diagnosis should be clinical; blood testing simply adds weight and prognostic information to the clinical assessment. Positive tests can be found in normal patients – beware of inappropriately labelling an insignificant problem as a significant arthritis on the basis of a blood test.

Gout is very painful, will limit movement and may cause a slight fever. Septic arthritis gives a similar picture but with marked restriction of movement and, usually, a high fever. If in doubt, arrange urgent assessment.

Gout is very painful, will limit movement and may cause a slight fever. Septic arthritis gives a similar picture but with marked restriction of movement and, usually, a high fever. If in doubt, arrange urgent assessment.

In obscure cases, question and examine the patient carefully. For example, in Reiter’s disease, symptoms of urethritis or conjunctivitis may have been minimal or forgotten; in psoriatic arthritis, there may only be insignificant skin lesions.

In obscure cases, question and examine the patient carefully. For example, in Reiter’s disease, symptoms of urethritis or conjunctivitis may have been minimal or forgotten; in psoriatic arthritis, there may only be insignificant skin lesions.

If one joint is red, very hot, intensely painful with marked limitation of movement and systemic illness, septic arthritis must be excluded: admit.

If one joint is red, very hot, intensely painful with marked limitation of movement and systemic illness, septic arthritis must be excluded: admit.

Haemarthrosis usually develops rapidly after trauma and indicates significant damage requiring immediate referral; effusion due to synovitis usually takes a day or longer to accumulate and is less urgent.

Haemarthrosis usually develops rapidly after trauma and indicates significant damage requiring immediate referral; effusion due to synovitis usually takes a day or longer to accumulate and is less urgent.

Septic arthritis is notoriously easy to miss in a patient with coexisting RA. The systemic signs may be absent and the diagnosis may mistakenly be viewed as a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis.

Septic arthritis is notoriously easy to miss in a patient with coexisting RA. The systemic signs may be absent and the diagnosis may mistakenly be viewed as a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis.

A young adult male with a monoarthritis of the knee not caused by trauma is likely to have Reiter’s disease.

A young adult male with a monoarthritis of the knee not caused by trauma is likely to have Reiter’s disease.

![]()

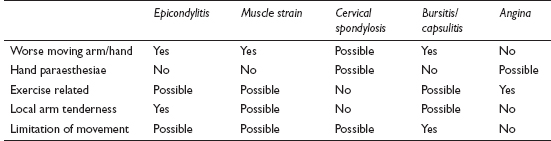

Arm pain is a common presentation with a wide differential. Many generalised disorders, such as arthritis, neuropathy and polymyalgia, cause widespread symptoms, which may involve the arm – these are not considered here. Instead, this section concentrates on pain specific to the arm, or pain characteristically referred to the arm.

![]()

COMMON

simple muscular strain

simple muscular strain

epicondylitis (tennis or golfer’s elbow)

epicondylitis (tennis or golfer’s elbow)

subacromial bursitis/capsulitis

subacromial bursitis/capsulitis

cervical spondylosis

cervical spondylosis

angina

angina

OCCASIONAL

bicipital tendonitis

bicipital tendonitis

acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint pain

acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint pain

acute calcific tendonitis

acute calcific tendonitis

de Quervain’s tenosynovitis

de Quervain’s tenosynovitis

carpal tunnel (CT) syndrome

carpal tunnel (CT) syndrome

cervical rib

cervical rib

brachial and ulnar neuritis (including post-herpetic pain)

brachial and ulnar neuritis (including post-herpetic pain)

cervical and thoracic disc prolapse

cervical and thoracic disc prolapse

RARE

GORD

GORD

malignancy: local bone cancer, spinal cord, spine and lung

malignancy: local bone cancer, spinal cord, spine and lung

subclavian aneurysm

subclavian aneurysm

multiple sclerosis

multiple sclerosis

syphilitic aortitis

syphilitic aortitis

thoracic outlet syndrome

thoracic outlet syndrome

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, TFT, ECG/secondary care cardiac investigations, nerve conduction studies, chest and neck X-ray.

SMALL PRINT: other X-rays/bone scan, MRI scan, lumbar puncture, syphilis serology.

FBC, ESR/CRP: may be anaemia and raised ESR/CRP in inflammatory or malignant conditions.

FBC, ESR/CRP: may be anaemia and raised ESR/CRP in inflammatory or malignant conditions.

TFT: myxoedema and carpal tunnel syndrome significantly associated.

TFT: myxoedema and carpal tunnel syndrome significantly associated.

Neck X-ray sometimes useful to confirm diagnosis of cervical spondylosis and assess its severity – but cervical spondylosis on X-ray does not correlate well with symptoms and may just be an incidental finding.

Neck X-ray sometimes useful to confirm diagnosis of cervical spondylosis and assess its severity – but cervical spondylosis on X-ray does not correlate well with symptoms and may just be an incidental finding.

ECG/secondary care cardiac investigations: to pursue possible diagnosis of angina.

ECG/secondary care cardiac investigations: to pursue possible diagnosis of angina.

Nerve conduction studies: will help confirm nerve entrapment (e.g. carpal tunnel).

Nerve conduction studies: will help confirm nerve entrapment (e.g. carpal tunnel).

CXR: for apical tumour.

CXR: for apical tumour.

Other X-rays/bone scans: if bony tumour (especially secondaries) suspected. Calcium deposits may be seen in acute calcific tendonitis.

Other X-rays/bone scans: if bony tumour (especially secondaries) suspected. Calcium deposits may be seen in acute calcific tendonitis.

MRI scan, lumbar puncture: if MS suspected; scanning may also be helpful to visualise possible cord lesion (all likely to be arranged after specialist referral).

MRI scan, lumbar puncture: if MS suspected; scanning may also be helpful to visualise possible cord lesion (all likely to be arranged after specialist referral).

Syphilis serology: in the rare case of possible syphilis.

Syphilis serology: in the rare case of possible syphilis.

It is tempting to view arm pain as a welcome ‘quickie’; in fact, a careful history is important to exclude the more unusual serious pathologies and the examination should usually serve only to confirm an already formulated diagnosis.

It is tempting to view arm pain as a welcome ‘quickie’; in fact, a careful history is important to exclude the more unusual serious pathologies and the examination should usually serve only to confirm an already formulated diagnosis.

Patients with arm pain – especially if it is accompanied by intermittent paraesthesiae – are often inappropriately concerned that the diagnosis may be angina or a stroke. Make sure these fears are properly explored.

Patients with arm pain – especially if it is accompanied by intermittent paraesthesiae – are often inappropriately concerned that the diagnosis may be angina or a stroke. Make sure these fears are properly explored.

The natural history of many of the more common problems (e.g. subacromial bursitis, epicondylitis) can be quite prolonged. Making this clear from the outset helps maintain the patient’s trust in you if the symptoms do take some time to settle.

The natural history of many of the more common problems (e.g. subacromial bursitis, epicondylitis) can be quite prolonged. Making this clear from the outset helps maintain the patient’s trust in you if the symptoms do take some time to settle.

Getting the patient to indicate the site of pain is a useful ploy in shoulder discomfort. Diffuse pain is typical of capsulitis and subacromial bursitis, whereas, with sternoclavicular or acromioclavicular joint problems, or bicipital tendonitis, the area is more likely to be very localised.

Getting the patient to indicate the site of pain is a useful ploy in shoulder discomfort. Diffuse pain is typical of capsulitis and subacromial bursitis, whereas, with sternoclavicular or acromioclavicular joint problems, or bicipital tendonitis, the area is more likely to be very localised.

Beware of persistent paraesthesiae with arm pain, especially if the patient also complains of arm or hand weakness; either there is serious nerve compression or some other significant neurological pathology.

Beware of persistent paraesthesiae with arm pain, especially if the patient also complains of arm or hand weakness; either there is serious nerve compression or some other significant neurological pathology.

Angina may present only with arm pain. Enquire carefully to establish the pattern of the pain.

Angina may present only with arm pain. Enquire carefully to establish the pattern of the pain.

Apical lung tumour (Pancoast tumour) may cause severe arm pain long before any signs are evident. Investigate smokers with unexplained arm pain.

Apical lung tumour (Pancoast tumour) may cause severe arm pain long before any signs are evident. Investigate smokers with unexplained arm pain.

Consider the other less common diagnoses if the pain is severe and persistent, the diagnosis is not obvious from the history and the patient displays unrestricted arm movements.

Consider the other less common diagnoses if the pain is severe and persistent, the diagnosis is not obvious from the history and the patient displays unrestricted arm movements.

![]()

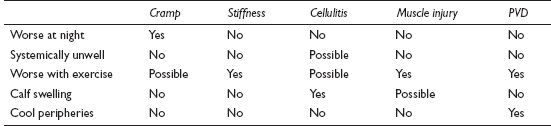

Calf pain is usually innocent, except when accompanied by swelling. It is often caused by cramp, which is especially common in the elderly. In this group it can cause significant distress, through the havoc wreaked on sleep. Some of the less likely diagnoses, such as peripheral vascular disease, have important implications, so careful assessment is necessary.

![]()

COMMON

idiopathic (simple) cramp (including night cramps)

idiopathic (simple) cramp (including night cramps)

muscle stiffness (unaccustomed exercise)

muscle stiffness (unaccustomed exercise)

cellulitis

cellulitis

peripheral vascular disease (PVD; intermittent claudication)

peripheral vascular disease (PVD; intermittent claudication)

muscle injury (e.g. strain)

muscle injury (e.g. strain)

OCCASIONAL

referred back pain (L4 and 5)

referred back pain (L4 and 5)

referred knee pain (arthropathy, infection)

referred knee pain (arthropathy, infection)

alcoholic or diabetic neuropathy

alcoholic or diabetic neuropathy

cramps caused by underlying hypocalcaemia or electrolyte imbalance

cramps caused by underlying hypocalcaemia or electrolyte imbalance

ruptured Baker’s cyst

ruptured Baker’s cyst

deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

thrombophlebitis

thrombophlebitis

RARE

motor neurone disease

motor neurone disease

multiple sclerosis

multiple sclerosis

muscle enzyme deficiency

muscle enzyme deficiency

psychological: muscle tension

psychological: muscle tension

lead and strychnine poisoning

lead and strychnine poisoning

ruptured Achilles tendon

ruptured Achilles tendon

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, WCC, ESR/CRP, U&E, LFT, blood glucose or HbA1c, D-dimer.

SMALL PRINT: ultrasound, venogram, angiography.

Urinalysis: check specific gravity, glucose and protein (over and under-hydration, diabetes, renal failure as occasional causes of ‘simple’ cramp).

Urinalysis: check specific gravity, glucose and protein (over and under-hydration, diabetes, renal failure as occasional causes of ‘simple’ cramp).

WCC and ESR/CRP: both raised in infection. ESR/CRP raised in arthropathy.

WCC and ESR/CRP: both raised in infection. ESR/CRP raised in arthropathy.

U&E and calcium: check renal function and electrolyte imbalance (e.g. from diuretics; hypocalcaemia).

U&E and calcium: check renal function and electrolyte imbalance (e.g. from diuretics; hypocalcaemia).

LFT and blood glucose or HbA1c: if suspect alcoholism or diabetes resulting in a neuropathy.

LFT and blood glucose or HbA1c: if suspect alcoholism or diabetes resulting in a neuropathy.

D-dimer (usually in hospital): a raised level suggests a DVT, but is not conclusive.

D-dimer (usually in hospital): a raised level suggests a DVT, but is not conclusive.

Consider referring urgently for ultrasound of lower limb veins with or without venography if DVT suspected.

Consider referring urgently for ultrasound of lower limb veins with or without venography if DVT suspected.

Angiography will be arranged by the specialist if peripheral vascular disease is suspected.

Angiography will be arranged by the specialist if peripheral vascular disease is suspected.

Save the patient unnecessary investigation and possible anticoagulation by taking a careful history. A muscle tear and a DVT can both produce calf swelling and warmth. The former, though, is preceded by a dramatic and sudden pain in the calf, sometimes described as being like a kick or a gunshot.

Save the patient unnecessary investigation and possible anticoagulation by taking a careful history. A muscle tear and a DVT can both produce calf swelling and warmth. The former, though, is preceded by a dramatic and sudden pain in the calf, sometimes described as being like a kick or a gunshot.

It can be difficult to distinguish a simple muscle strain from claudication. Muscular pains tend to produce discomfort as soon as the patient stands; claudication usually starts after the patient has walked a predictable distance.

It can be difficult to distinguish a simple muscle strain from claudication. Muscular pains tend to produce discomfort as soon as the patient stands; claudication usually starts after the patient has walked a predictable distance.

Patients with superficial phlebitis will fear the more serious DVT. Explain the difference to them.

Patients with superficial phlebitis will fear the more serious DVT. Explain the difference to them.

Do not overlook Achilles rupture. The presentation may sometimes be less dramatic than you would expect.

Do not overlook Achilles rupture. The presentation may sometimes be less dramatic than you would expect.

Children rarely present with cramp (though it is common): avoid labelling as ‘growing pains’ unless serious causes are excluded.

Children rarely present with cramp (though it is common): avoid labelling as ‘growing pains’ unless serious causes are excluded.

Consider investigating the adult patient with recent onset of apparently simple cramps if associated with general malaise (these will be in the minority).

Consider investigating the adult patient with recent onset of apparently simple cramps if associated with general malaise (these will be in the minority).

Claudication accompanied by nocturnal pain in the ball of the foot suggests critical ischaemia – refer urgently.

Claudication accompanied by nocturnal pain in the ball of the foot suggests critical ischaemia – refer urgently.

Homans’s sign is positive in virtually all painful conditions of the calf. It is not diagnostic of DVT.

Homans’s sign is positive in virtually all painful conditions of the calf. It is not diagnostic of DVT.

![]()

Pain in the foot is difficult for patients to ignore and so will often present with a relatively short history. Local causes predominate, but remember to think further afield: referral through S1 (lateral border of the foot) and L5 (dorsum of the foot to the big toe) nerve roots may occur. Ankle pain is not considered here.

![]()

COMMON

gout

gout

verruca

verruca

bunion/hallux valgus

bunion/hallux valgus

infected ingrowing toenail (IGTN)

infected ingrowing toenail (IGTN)

plantar fasciitis

plantar fasciitis

OCCASIONAL

Morton’s neuroma

Morton’s neuroma

metatarsalgia

metatarsalgia

arthritis (osteo and rheumatoid)

arthritis (osteo and rheumatoid)

Achilles tendonitis/bursitis

Achilles tendonitis/bursitis

oedema

oedema

foreign body

foreign body

RARE

march fracture

march fracture

Sever’s disease (apophysitis of the calcaneus), usually a problem of adolescence

Sever’s disease (apophysitis of the calcaneus), usually a problem of adolescence

osteochondritis: navicular = Köhler’s disease; head of second or third metatarsal = Freiberg’s disease

osteochondritis: navicular = Köhler’s disease; head of second or third metatarsal = Freiberg’s disease

osteomyelitis and septic arthritis

osteomyelitis and septic arthritis

erythromelalgia and painful polyneuropathy

erythromelalgia and painful polyneuropathy

ischaemia

ischaemia

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, FBC, ESR/CRP, rheumatoid factor, uric acid, X-ray.

SMALL PRINT: bone scan, angiography.

NOTE: if the cause is oedema, this will need investigating in its own right (see Swollen ankles, p. 312).

Urinalysis may reveal glycosuria in previously undiagnosed diabetic with neuropathy (suspicion of neuropathy may in itself require further investigations).

Urinalysis may reveal glycosuria in previously undiagnosed diabetic with neuropathy (suspicion of neuropathy may in itself require further investigations).

FBC/ESR/CRP: raised WCC and ESR/CRP in infection and severe inflammation.

FBC/ESR/CRP: raised WCC and ESR/CRP in infection and severe inflammation.

Rheumatoid factor: of prognostic help if foot pain is part of clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid factor: of prognostic help if foot pain is part of clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Uric acid: if gout suspected, especially with recurrent attacks and if considering prophylaxis.

Uric acid: if gout suspected, especially with recurrent attacks and if considering prophylaxis.

X-ray useful if suspect possible arthritis, osteomyelitis, march fracture, osteochondritis, radio-opaque foreign body. If clinical suspicion high and X-ray unhelpful, bone scan may be more useful.

X-ray useful if suspect possible arthritis, osteomyelitis, march fracture, osteochondritis, radio-opaque foreign body. If clinical suspicion high and X-ray unhelpful, bone scan may be more useful.

Angiography: if ischaemic foot with rest pain.

Angiography: if ischaemic foot with rest pain.

The vast majority of causes are obvious from the history or from a cursory examination. The harder you have to think, the more likely that there may be an obscure cause requiring investigation.

The vast majority of causes are obvious from the history or from a cursory examination. The harder you have to think, the more likely that there may be an obscure cause requiring investigation.

It can be difficult to distinguish gout from a severely inflamed bunion. With gout, the patient may have had previous episodes, the onset tends to be sudden, the joint is extremely tender and joint movements are very limited.

It can be difficult to distinguish gout from a severely inflamed bunion. With gout, the patient may have had previous episodes, the onset tends to be sudden, the joint is extremely tender and joint movements are very limited.

Important pointers can be picked up in the history, especially for some of the less common causes. Thus, Morton’s neuroma causes a sharp pain often radiating to the third and fourth toes, relieved by removing the shoe; plantar fasciitis is described as ‘walking on a pebble’, especially after resting; and a march fracture results in a pain which initially comes on predictably with exercise and which then becomes continuous, with local bony tenderness and possibly a lump.

Important pointers can be picked up in the history, especially for some of the less common causes. Thus, Morton’s neuroma causes a sharp pain often radiating to the third and fourth toes, relieved by removing the shoe; plantar fasciitis is described as ‘walking on a pebble’, especially after resting; and a march fracture results in a pain which initially comes on predictably with exercise and which then becomes continuous, with local bony tenderness and possibly a lump.

If a known arteriopath complains of pain in the ball of the foot disturbing sleep then the diagnosis is probably critical ischaemia. Refer urgently.

If a known arteriopath complains of pain in the ball of the foot disturbing sleep then the diagnosis is probably critical ischaemia. Refer urgently.

Fever and systemic illness with localised extreme bone pain and signs of local infection is acute osteomyelitis or septic arthritis until proved otherwise. Admit.

Fever and systemic illness with localised extreme bone pain and signs of local infection is acute osteomyelitis or septic arthritis until proved otherwise. Admit.

Pain with no obvious signs – particularly tenderness – in the foot suggests ischaemia, neuropathy or an L5/S1 nerve root lesion.

Pain with no obvious signs – particularly tenderness – in the foot suggests ischaemia, neuropathy or an L5/S1 nerve root lesion.

If no cause is evident but the patient has very localised sole tenderness away from the heel, consider a foreign body.

If no cause is evident but the patient has very localised sole tenderness away from the heel, consider a foreign body.

![]()

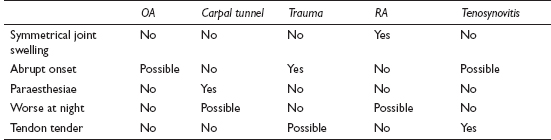

This may be the presenting problem but just as often it is a ‘while I’m here’ symptom. The differential diagnosis is quite wide but ‘arthritis’ is often uppermost in the patient’s mind. A brief history and focused examination should provide the correct diagnosis quite rapidly in most cases.

![]()

COMMON

osteoarthritis (especially the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers)

osteoarthritis (especially the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers)

carpal tunnel syndrome

carpal tunnel syndrome

trauma (e.g. sprain, scaphoid fracture)

trauma (e.g. sprain, scaphoid fracture)

rheumatoid (or other inflammatory) arthritis

rheumatoid (or other inflammatory) arthritis

tenosynovitis

tenosynovitis

OCCASIONAL

ganglion

ganglion

gout

gout

Raynaud’s disease or syndrome

Raynaud’s disease or syndrome

infection (e.g. paronychia, pulp space)

infection (e.g. paronychia, pulp space)

work-related upper limb disorder (WRULD)

work-related upper limb disorder (WRULD)

trigger thumb or finger

trigger thumb or finger

other nerve entrapment, e.g. ulnar nerve, cervical root pain

other nerve entrapment, e.g. ulnar nerve, cervical root pain

complex regional pain syndrome

complex regional pain syndrome

RARE

infected eczema (common, but rarely presents with pain)

infected eczema (common, but rarely presents with pain)

writer’s cramp

writer’s cramp

peripheral neuropathy

peripheral neuropathy

Dupuytren’s contracture (usually painless)

Dupuytren’s contracture (usually painless)

diabetic arthropathy

diabetic arthropathy

osteomyelitis

osteomyelitis

Kienböck’s disease (avascular necrosis of the lunate)

Kienböck’s disease (avascular necrosis of the lunate)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: X-ray, FBC, ESR/CRP, rheumatoid factor, uric acid.

SMALL PRINT: blood screen for underlying causes in peripheral neuropathy or Raynaud’s syndrome, if clinically indicated.

X-ray: may show a fracture in trauma, joint erosions in RA, the typical features of OA, and sclerosis or collapse of the lunate in Kienböck’s disease.

X-ray: may show a fracture in trauma, joint erosions in RA, the typical features of OA, and sclerosis or collapse of the lunate in Kienböck’s disease.

FBC: Hb may be reduced in inflammatory arthritis; WCC raised in infection.

FBC: Hb may be reduced in inflammatory arthritis; WCC raised in infection.

ESR/CRP: raised in infective and inflammatory conditions.

ESR/CRP: raised in infective and inflammatory conditions.

Rheumatoid factor: may support a clinical diagnosis of RA.

Rheumatoid factor: may support a clinical diagnosis of RA.

Uric acid: an elevated level (post episode) supports a diagnosis of gout.

Uric acid: an elevated level (post episode) supports a diagnosis of gout.

OA of the fingers can be relatively abrupt in onset and inflammatory in appearance compared with OA at other sites.

OA of the fingers can be relatively abrupt in onset and inflammatory in appearance compared with OA at other sites.

Explore the patient’s occupation – this will provide valuable information regarding the possible cause and effect of the problem.

Explore the patient’s occupation – this will provide valuable information regarding the possible cause and effect of the problem.

Simply asking the patient to point to the site of the pain can help distinguish two of the most commonly confused differentials: OA of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb and de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. In the former the pain is relatively localised to the base of the thumb; in the latter the discomfort – and certainly the tenderness – is more diffuse.

Simply asking the patient to point to the site of the pain can help distinguish two of the most commonly confused differentials: OA of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb and de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. In the former the pain is relatively localised to the base of the thumb; in the latter the discomfort – and certainly the tenderness – is more diffuse.

Pain from a ganglion can precede the appearance of the ganglion itself – or the ganglion may be fairly subtle, only appearing on wrist flexion.

Pain from a ganglion can precede the appearance of the ganglion itself – or the ganglion may be fairly subtle, only appearing on wrist flexion.

Remember that RA is a clinical diagnosis – don’t rely on blood tests. Early referral minimises the risk of long-term joint damage.

Remember that RA is a clinical diagnosis – don’t rely on blood tests. Early referral minimises the risk of long-term joint damage.

If in doubt over tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox after a fall on the outstretched hand, refer for A&E assessment – a missed scaphoid fracture can cause long-term problems.

If in doubt over tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox after a fall on the outstretched hand, refer for A&E assessment – a missed scaphoid fracture can cause long-term problems.

Do not underestimate pulp space infection – this can cause serious complications such as osteomyelitis or bacterial tenosynovitis. It may need IV antibiotics or incision and drainage.

Do not underestimate pulp space infection – this can cause serious complications such as osteomyelitis or bacterial tenosynovitis. It may need IV antibiotics or incision and drainage.

Thenar wasting suggests significant compression in carpal tunnel syndrome – refer.

Thenar wasting suggests significant compression in carpal tunnel syndrome – refer.

![]()

Chronic leg ulcer is a major problem in the UK, costing the National Health Service up to £600m per annum. It is reckoned that nearly 1% of the population may be affected by leg ulceration at some time during their lives. Recurrence is common. The vast majority have a vascular underlying cause.

![]()

COMMON

venous disease: 70–80% of leg ulcers

venous disease: 70–80% of leg ulcers

peripheral arterial disease: about 15% of leg ulcers

peripheral arterial disease: about 15% of leg ulcers

associated with systemic disease – diabetes (5% of ulcer patients), rheumatoid arthritis (8%), vasculitis

associated with systemic disease – diabetes (5% of ulcer patients), rheumatoid arthritis (8%), vasculitis

gross oedema due to systemic causes, e.g. CCF, renal disease, osteoarthritis, severe obesity, prolonged immobility from any cause

gross oedema due to systemic causes, e.g. CCF, renal disease, osteoarthritis, severe obesity, prolonged immobility from any cause

chronic infection, e.g. after trauma, insect bite

chronic infection, e.g. after trauma, insect bite

OCCASIONAL

drug misuse

drug misuse

after primary herpes zoster

after primary herpes zoster

primary malignancy – squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, malignant change in an existing ulcer

primary malignancy – squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, malignant change in an existing ulcer

secondary malignancy – metastases

secondary malignancy – metastases

RARE

tropical infections

tropical infections

AIDS

AIDS

tuberculosis

tuberculosis

systemic drug reaction

systemic drug reaction

factitious – self-inflicted (Munchausen’s, personality disorder)

factitious – self-inflicted (Munchausen’s, personality disorder)

![]()

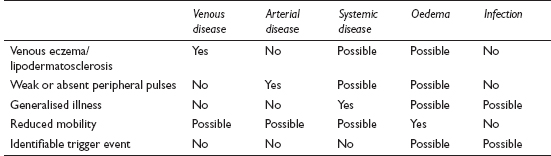

NOTE: In practice it is very difficult indeed to separate the causes of leg ulcers through clinical examination alone. This is a guide to likely causes only.

![]()

LIKELY: FBC, ESR/CRP, TSH, LFTs, U&E, fasting glucose or HbA1c and RA factor, ABPI.

POSSIBLE: swabs for bacteriology, cardiovascular assessment if appropriate.

SMALL PRINT: Duplex ultrasound.

FBC, ESR/CRP, CRP, TSH, LFTs, U&E, fasting glucose or HbA1c and RA factor as a basic screen for systemic causes and background disease.

FBC, ESR/CRP, CRP, TSH, LFTs, U&E, fasting glucose or HbA1c and RA factor as a basic screen for systemic causes and background disease.

Swabs for bacteriology are only useful if there is clinical evidence of viable tissue infection, e.g. cellulitis.

Swabs for bacteriology are only useful if there is clinical evidence of viable tissue infection, e.g. cellulitis.

Full cardiovascular assessment if any suspicion of arterial insufficiency.

Full cardiovascular assessment if any suspicion of arterial insufficiency.

Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) in both legs by handheld Doppler. Sensitivity of up to 95%; if less than 0.8 assume arterial disease is present. Limited usefulness in patients with microvascular disease, e.g. RA, DM, systemic vasculitis; may cause spuriously high ABPI.

Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) in both legs by handheld Doppler. Sensitivity of up to 95%; if less than 0.8 assume arterial disease is present. Limited usefulness in patients with microvascular disease, e.g. RA, DM, systemic vasculitis; may cause spuriously high ABPI.

Specialist: Duplex ultrasound is the investigation of choice to assess arterial and venous insufficiency.

Specialist: Duplex ultrasound is the investigation of choice to assess arterial and venous insufficiency.

Be systematic in the clinical notes: describe the edge (e.g. rolled, punched-out), base (e.g. sloughy, necrotic, granulating), location, morphology (may help detect rarer causes), and surface area (serial measurements of surface area of an ulcer are a good index of healing).

Be systematic in the clinical notes: describe the edge (e.g. rolled, punched-out), base (e.g. sloughy, necrotic, granulating), location, morphology (may help detect rarer causes), and surface area (serial measurements of surface area of an ulcer are a good index of healing).

Palpation of peripheral pulses is not a reliable guide to arterial sufficiency. Use the ABPI.

Palpation of peripheral pulses is not a reliable guide to arterial sufficiency. Use the ABPI.

Lipodermatosclerosis is a red or brown patch of skin on the lower leg, usually on the medial side, just above the ankle. This and venous eczema are indications of superficial venous valve failure, even in the absence of varicose veins. They may represent disease amenable to surgery, so refer for a vascular opinion.

Lipodermatosclerosis is a red or brown patch of skin on the lower leg, usually on the medial side, just above the ankle. This and venous eczema are indications of superficial venous valve failure, even in the absence of varicose veins. They may represent disease amenable to surgery, so refer for a vascular opinion.

Deep ulcers involving deep fascia, tendon, periosteum or bone may well have an arterial component.

Deep ulcers involving deep fascia, tendon, periosteum or bone may well have an arterial component.

Mixed ulcer aetiology may confuse the clinical picture and make treatment choices harder. Refer for a specialist opinion if in any doubt.

Mixed ulcer aetiology may confuse the clinical picture and make treatment choices harder. Refer for a specialist opinion if in any doubt.

More than 50% of leg ulcer patients are sensitive to one or more allergens, including lanolin, topical antibiotics, cetyl stearyl alcohols, balsam of Peru and parabens. These may contribute to non-healing and cause discomfort to the patient. Refer the patient for patch testing if dermatitis is associated with a leg ulcer.

More than 50% of leg ulcer patients are sensitive to one or more allergens, including lanolin, topical antibiotics, cetyl stearyl alcohols, balsam of Peru and parabens. These may contribute to non-healing and cause discomfort to the patient. Refer the patient for patch testing if dermatitis is associated with a leg ulcer.

Topical antibiotics do not contribute to healing and are frequent sensitisers – avoid using them.

Topical antibiotics do not contribute to healing and are frequent sensitisers – avoid using them.

Pain from an ulcer is most frequently associated with an arterial aetiology.

Pain from an ulcer is most frequently associated with an arterial aetiology.

Refer for biopsy if the ulcer has an atypical appearance or distribution, or fails to heal within 12 weeks of treatment. Beware neoplastic change in an existing ulcer. This is rare, but not to be missed.

Refer for biopsy if the ulcer has an atypical appearance or distribution, or fails to heal within 12 weeks of treatment. Beware neoplastic change in an existing ulcer. This is rare, but not to be missed.

Compression bandaging is dangerous in diabetes and arterial insufficiency. Do not prescribe it until they are ruled out. If in doubt about ABPI, refer for a vascular opinion.

Compression bandaging is dangerous in diabetes and arterial insufficiency. Do not prescribe it until they are ruled out. If in doubt about ABPI, refer for a vascular opinion.

![]()

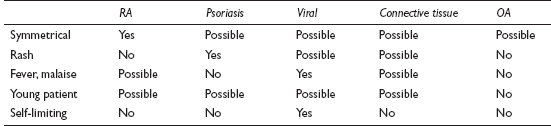

The range of causes of multiple joint pain spans acute, chronic and chronic relapsing conditions. In the elderly, the commonest problem is multiple osteoarthritis; in middle age, inflammatory conditions predominate; and in the young, systemic conditions are more likely.

![]()

COMMON

rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

psoriatic arthropathy

psoriatic arthropathy

viral polyarthritis, e.g. hepatitis, rubella

viral polyarthritis, e.g. hepatitis, rubella

connective tissue diseases, e.g. SLE, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, giant cell arteritis

connective tissue diseases, e.g. SLE, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, giant cell arteritis

multiple osteoarthritis (OA)

multiple osteoarthritis (OA)

OCCASIONAL

the spondoarthritides: ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s disease, enteropathic arthritis, Behçet’s syndrome, juvenile chronic arthritis

the spondoarthritides: ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s disease, enteropathic arthritis, Behçet’s syndrome, juvenile chronic arthritis

Henoch–Schönlein syndrome

Henoch–Schönlein syndrome

malignancy (usually secondary)

malignancy (usually secondary)

iatrogenic: corticosteroid therapy, isoniazid, hydralazine

iatrogenic: corticosteroid therapy, isoniazid, hydralazine

hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (due to lung cancer)

hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (due to lung cancer)

sarcoidosis

sarcoidosis

RARE

sickle-cell crisis

sickle-cell crisis

amyloidosis

amyloidosis

rheumatic fever

rheumatic fever

atypical systemic infections, e.g. Lyme disease, Weil’s disease, brucellosis, syphilis (secondary)

atypical systemic infections, e.g. Lyme disease, Weil’s disease, brucellosis, syphilis (secondary)

decompression sickness (the bends)

decompression sickness (the bends)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: FBC, ESR/CRP, autoantibodies.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, U&E, HLA-B27, joint X-rays, synovial fluid aspiration.

SMALL PRINT: blood film, serology, creatine phosphokinase, CXR, bone scan, Kveim test.

FBC, ESR/CRP, blood film: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in acute inflammation and infection. Anaemia of chronic disease may be seen, and blood film will reveal sickle cell.

FBC, ESR/CRP, blood film: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in acute inflammation and infection. Anaemia of chronic disease may be seen, and blood film will reveal sickle cell.

Autoantibodies: rheumatoid factor is positive in most cases of RA, but is also positive in many autoimmune diseases and chronic infections; antinuclear factor is positive in 90% of cases of SLE but a similar result is obtained in 30% of cases of RA and also in many other diseases.

Autoantibodies: rheumatoid factor is positive in most cases of RA, but is also positive in many autoimmune diseases and chronic infections; antinuclear factor is positive in 90% of cases of SLE but a similar result is obtained in 30% of cases of RA and also in many other diseases.

Urinalysis: may reveal proteinuria or haematuria if there is renal involvement in connective tissue disease.

Urinalysis: may reveal proteinuria or haematuria if there is renal involvement in connective tissue disease.

U&E: to check for renal failure via renal involvement in multisystem connective tissue disease.

U&E: to check for renal failure via renal involvement in multisystem connective tissue disease.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

Serology: may be useful to diagnose viral, or atypical systemic, infections. ASO titres, if rising, suggest recent streptococcal infection (e.g. in rheumatic fever).

Serology: may be useful to diagnose viral, or atypical systemic, infections. ASO titres, if rising, suggest recent streptococcal infection (e.g. in rheumatic fever).

Creatine phosphokinase: elevated in polymyositis.

Creatine phosphokinase: elevated in polymyositis.

Joint X-rays: hand X-rays may show characteristic features helping to distinguish between RA and psoriatic arthritis; pelvic and lumbar spine X-rays may show the typical changes of ankylosing spondylitis (if negative, and clinical suspicion high, a bone scan may be helpful); X-rays of affected joints may confirm clinical diagnosis of OA.

Joint X-rays: hand X-rays may show characteristic features helping to distinguish between RA and psoriatic arthritis; pelvic and lumbar spine X-rays may show the typical changes of ankylosing spondylitis (if negative, and clinical suspicion high, a bone scan may be helpful); X-rays of affected joints may confirm clinical diagnosis of OA.

CXR: may reveal lung malignancy.

CXR: may reveal lung malignancy.

Synovial fluid analysis: helps distinguish inflammatory from infective and crystal arthropathies.

Synovial fluid analysis: helps distinguish inflammatory from infective and crystal arthropathies.

Sarcoidosis: Kveim test may help confirm diagnosis.

Sarcoidosis: Kveim test may help confirm diagnosis.

The connective tissue diseases can all affect almost every organ system. Take a full history so as not to miss a clue or complication.

The connective tissue diseases can all affect almost every organ system. Take a full history so as not to miss a clue or complication.

Check the skin as this may contribute to the diagnosis (e.g. scaly rash in psoriasis, butterfly rash in SLE, thickening of skin in sclerosis and heliotrope rash in dermatomyositis).

Check the skin as this may contribute to the diagnosis (e.g. scaly rash in psoriasis, butterfly rash in SLE, thickening of skin in sclerosis and heliotrope rash in dermatomyositis).

Don’t overvalue autoimmune blood tests. Most diagnoses of arthritis are clinical, blood tests simply providing confirmatory or prognostic information.

Don’t overvalue autoimmune blood tests. Most diagnoses of arthritis are clinical, blood tests simply providing confirmatory or prognostic information.

Suspect Reiter’s syndrome in a young male with an inflammatory oligoarthritis of the lower limbs.

Suspect Reiter’s syndrome in a young male with an inflammatory oligoarthritis of the lower limbs.

An insidious onset of symmetrical polyarthritis in the 30–50 age range, with early morning stiffness, pain and swelling of hands and feet, suggests RA.

An insidious onset of symmetrical polyarthritis in the 30–50 age range, with early morning stiffness, pain and swelling of hands and feet, suggests RA.

Pain in the wrists and ankles of a middle-aged or elderly smoker with clubbing and chest symptoms strongly suggests hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy caused by underlying lung cancer.

Pain in the wrists and ankles of a middle-aged or elderly smoker with clubbing and chest symptoms strongly suggests hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy caused by underlying lung cancer.

Don’t overlook the patient’s occupation as this may be relevant in certain cases: for example, in vets and farm workers, brucellosis and Weil’s disease are possible infective causes.

Don’t overlook the patient’s occupation as this may be relevant in certain cases: for example, in vets and farm workers, brucellosis and Weil’s disease are possible infective causes.

![]()

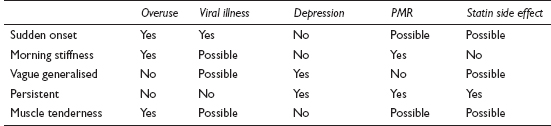

This symptom has a multitude of causes. A careful history is required to distinguish between muscle and joint pain, and between muscle pain and weakness. In some of the underlying pathologies, these symptoms may coexist. Cramp, causing very transient muscle pain, is covered elsewhere (see Calf pain, p. 288).

![]()

COMMON

overuse (including strain injury)

overuse (including strain injury)

acute viral illness

acute viral illness

depression

depression

polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR)

polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR)

side effects of statins (myalgia much more common than myositis)

side effects of statins (myalgia much more common than myositis)

OCCASIONAL

vitamin D deficiency

vitamin D deficiency

referred joint pain (e.g. from hip to thigh, neck to shoulder, shoulder to arm)

referred joint pain (e.g. from hip to thigh, neck to shoulder, shoulder to arm)

fibromyalgia

fibromyalgia

chronic fatigue syndrome

chronic fatigue syndrome

connective tissue disease, e.g. RA, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), scleroderma

connective tissue disease, e.g. RA, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), scleroderma

peripheral vascular disease: intermittent claudication

peripheral vascular disease: intermittent claudication

neuropathy: diabetic, alcoholic

neuropathy: diabetic, alcoholic

Bornholm disease (epidemic myalgia, devil’s grip)

Bornholm disease (epidemic myalgia, devil’s grip)

hypothyroidism

hypothyroidism

drugs: statins, clofibrate, street drug withdrawal, chemotherapy, lithium, cimetidine

drugs: statins, clofibrate, street drug withdrawal, chemotherapy, lithium, cimetidine

RARE

polymyositis (usually more weakness than pain)

polymyositis (usually more weakness than pain)

adult and childhood dermatomyositis

adult and childhood dermatomyositis

underlying malignancy

underlying malignancy

porphyria

porphyria

Guillain–Barré syndrome and poliomyelitis

Guillain–Barré syndrome and poliomyelitis

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: FBC, ESR/CRP.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, autoimmune blood tests, TFT, LFT, blood sugar or HbA1c, creatine phosphokinase (CPK), vitamin D levels.

SMALL PRINT: joint and chest X-rays; in secondary care, angiography, electromyography, muscle biopsy, lumbar puncture, urinary porphyrins.

Urinalysis: glycosuria in undiagnosed diabetes.

Urinalysis: glycosuria in undiagnosed diabetes.

FBC and ESR/CRP: Hb may be depressed in connective tissue disease and PMR. WCC and ESR/CRP raised in any inflammatory disorder (ESR more useful than CRP in PMR); MCV elevated in hypothyroidism and alcohol abuse.

FBC and ESR/CRP: Hb may be depressed in connective tissue disease and PMR. WCC and ESR/CRP raised in any inflammatory disorder (ESR more useful than CRP in PMR); MCV elevated in hypothyroidism and alcohol abuse.

Autoimmune blood tests: may be helpful if connective tissue disorder suspected.

Autoimmune blood tests: may be helpful if connective tissue disorder suspected.

TFT: will confirm hypothyroidism.

TFT: will confirm hypothyroidism.

Blood sugar or HbA1c, LFT: the former to confirm diabetes; the latter may help in confirming an alcohol problem. Both may cause a neuropathy resulting in muscle pain.

Blood sugar or HbA1c, LFT: the former to confirm diabetes; the latter may help in confirming an alcohol problem. Both may cause a neuropathy resulting in muscle pain.

CPK: raised in acute inflammatory and viral myopathies.

CPK: raised in acute inflammatory and viral myopathies.

Vitamin D levels: vitamin D deficiency is increasingly being recognised and may present with muscle pain and/or weakness.

Vitamin D levels: vitamin D deficiency is increasingly being recognised and may present with muscle pain and/or weakness.

Joint X-rays: if referred pain from primary joint pathology suspected.

Joint X-rays: if referred pain from primary joint pathology suspected.

Angiography: for peripheral vascular disease.

Angiography: for peripheral vascular disease.

Electromyography and muscle biopsy (both in secondary care): to confirm diagnosis of polymyositis or dermatomyositis.

Electromyography and muscle biopsy (both in secondary care): to confirm diagnosis of polymyositis or dermatomyositis.

Lumbar puncture: to examine CSF in hospital in suspected Guillain–Barré syndrome or poliomyelitis.

Lumbar puncture: to examine CSF in hospital in suspected Guillain–Barré syndrome or poliomyelitis.

Urinary porphyrins: to exclude porphyria.

Urinary porphyrins: to exclude porphyria.

Other investigations for suspected underlying malignancy, e.g. CXR.

Other investigations for suspected underlying malignancy, e.g. CXR.

In polysymptomatic patients with muscle pain but no objective signs and normal blood tests, consider fibromyalgia, depression and chronic fatigue (Note: these problems may coexist).

In polysymptomatic patients with muscle pain but no objective signs and normal blood tests, consider fibromyalgia, depression and chronic fatigue (Note: these problems may coexist).

The diagnosis of PMR is clinched by a trial of prednisolone (20 mg/day). In PMR, this treatment should lead to total resolution of symptoms within a few days.

The diagnosis of PMR is clinched by a trial of prednisolone (20 mg/day). In PMR, this treatment should lead to total resolution of symptoms within a few days.

Muscle pain is more likely to be associated with significant pathology in the very young and old than the middle-aged, when psychological causes and overuse are the most likely.

Muscle pain is more likely to be associated with significant pathology in the very young and old than the middle-aged, when psychological causes and overuse are the most likely.

Always remember PMR in the older patient complaining of aching pain and stiffness in the hip and shoulder girdle muscles which is worse in the mornings.

Always remember PMR in the older patient complaining of aching pain and stiffness in the hip and shoulder girdle muscles which is worse in the mornings.

If considering PMR, or initiating treatment in this condition, enquire after symptoms of temporal arteritis. About 30% of patients develop this complication, and are at risk of blindness.

If considering PMR, or initiating treatment in this condition, enquire after symptoms of temporal arteritis. About 30% of patients develop this complication, and are at risk of blindness.

Muscle pain with significant and progressive weakness (e.g. difficulty climbing stairs or getting out of a chair) suggests polymyositis, hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency or malignancy.

Muscle pain with significant and progressive weakness (e.g. difficulty climbing stairs or getting out of a chair) suggests polymyositis, hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency or malignancy.

Significant underlying disease (e.g. PMR, polymyositis, dermatomyositis or connective tissue disease) is likely if there is an arthritis associated with the muscle pain.

Significant underlying disease (e.g. PMR, polymyositis, dermatomyositis or connective tissue disease) is likely if there is an arthritis associated with the muscle pain.

![]()

Hip area pain is a common presentation in the middle-aged and elderly, and the patient will often attribute it to osteoarthritis. This diagnosis may well be correct, although the differential is wide – besides, the patient’s view of what actually constitutes the ‘hip’ may be at odds with the anatomical truth. The differential for the child with hip pain is very different – see Limp in a child, p. 209.

![]()

COMMON

muscular/ligamentous strain

muscular/ligamentous strain

osteoarthritis

osteoarthritis

trochanteric bursitis

trochanteric bursitis

referred from back

referred from back

meralgia paraesthetica

meralgia paraesthetica

OCCASIONAL

inflammatory arthritis

inflammatory arthritis

avascular necrosis

avascular necrosis

hernia

hernia

complications of a total hip replacement, e.g. loosening, infection

complications of a total hip replacement, e.g. loosening, infection

spinal stenosis

spinal stenosis

iliotibial band syndrome

iliotibial band syndrome

acetabular labral tear

acetabular labral tear

RARE

impacted fracture

impacted fracture

dislocation

dislocation

bony pathology, e.g. secondaries, Paget’s

bony pathology, e.g. secondaries, Paget’s

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: X-ray.

POSSIBLE: FBC, CRP, autoantibodies, HLA-B27, alkaline phosphatase, urinalysis.

SMALL PRINT: arthroscopy, bone scan, lumbar spine MRI (all in hospital).

X-ray: may show evidence of osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, fracture, dislocation, hip replacement loosening and bony pathology. Spinal X-ray may reveal spinal pathology as a cause.

X-ray: may show evidence of osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, fracture, dislocation, hip replacement loosening and bony pathology. Spinal X-ray may reveal spinal pathology as a cause.

FBC, CRP: CRP may be elevated and Hb reduced in inflammatory arthritis. CRP and WCC raised in infection of joint prosthesis.

FBC, CRP: CRP may be elevated and Hb reduced in inflammatory arthritis. CRP and WCC raised in infection of joint prosthesis.

Autoantibodies: for clues about the aetiology of inflammatory arthritis.

Autoantibodies: for clues about the aetiology of inflammatory arthritis.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

Alkaline phosphatase: raised in Paget’s disease.

Alkaline phosphatase: raised in Paget’s disease.

Urinalysis: may reveal proteinuria or haematuria if there is renal involvement in inflammatory arthritis.

Urinalysis: may reveal proteinuria or haematuria if there is renal involvement in inflammatory arthritis.

Arthroscopy: diagnostic and potentially therapeutic in labral tear.

Arthroscopy: diagnostic and potentially therapeutic in labral tear.

Bone scan: may reveal bony secondaries.

Bone scan: may reveal bony secondaries.

Lumbar spine MRI: for evidence of spinal stenosis; might reveal other causes of pain referred from spine.

Lumbar spine MRI: for evidence of spinal stenosis; might reveal other causes of pain referred from spine.

Check what the patient means by ‘hip’. Most don’t realise that the hip joint is actually in the groin.

Check what the patient means by ‘hip’. Most don’t realise that the hip joint is actually in the groin.

An X-ray may not be necessary, even if the clinical picture suggests hip arthritis – but the patient may well expect one, so ensure it is at least discussed.

An X-ray may not be necessary, even if the clinical picture suggests hip arthritis – but the patient may well expect one, so ensure it is at least discussed.

Examine the patient standing up – this may reveal a hernia as the cause.

Examine the patient standing up – this may reveal a hernia as the cause.

Localised lateral pain aggravated by lying on the affected side is likely to be caused by trochanteric bursitis.

Localised lateral pain aggravated by lying on the affected side is likely to be caused by trochanteric bursitis.

Remember the possibility of loosening or infection in joint replacements.

Remember the possibility of loosening or infection in joint replacements.

Consider avascular necrosis if a patient on long-term steroids develops severe hip pain.

Consider avascular necrosis if a patient on long-term steroids develops severe hip pain.

Beware that the elderly can sometimes remain weight bearing – albeit with pain and a limp – after an impacted hip fracture.

Beware that the elderly can sometimes remain weight bearing – albeit with pain and a limp – after an impacted hip fracture.

Significant depression may aggravate or result from hip arthritis pain – consider a trial of antidepressants.

Significant depression may aggravate or result from hip arthritis pain – consider a trial of antidepressants.

![]()

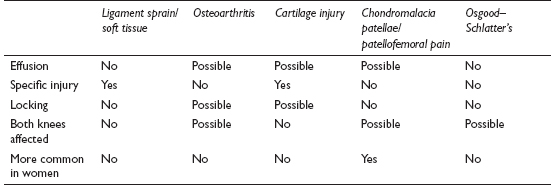

Recurrent knee pain is a very common presentation with a wide differential. Classification of causes isn’t helped by changing and confusing nomenclature. As ever in general practice, a careful history and examination will provide useful clues – but management will often be dictated more by degree of disability and the patient’s wishes than by making a precise diagnosis.

![]()

COMMON

ligament sprain/minor soft tissue injury

ligament sprain/minor soft tissue injury

osteoarthritis

osteoarthritis

cartilage injury

cartilage injury

chondromalacia patellae/patellofemoral pain

chondromalacia patellae/patellofemoral pain

Osgood–Schlatter’s disease

Osgood–Schlatter’s disease

OCCASIONAL

recurrent monoarthritis, e.g. gout, pseudogout, Reiter’s

recurrent monoarthritis, e.g. gout, pseudogout, Reiter’s

as part of polyarthritis, e.g. rheumatoid, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis

as part of polyarthritis, e.g. rheumatoid, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis

iliotibial tract syndrome

iliotibial tract syndrome

bursitis

bursitis

referred from hip or back

referred from hip or back

ligament rupture

ligament rupture

patellar tendonitis

patellar tendonitis

Baker’s cyst

Baker’s cyst

loose body

loose body

bone disease, e.g. Paget’s

bone disease, e.g. Paget’s

recurrent dislocation of the patella

recurrent dislocation of the patella

medial shelf syndrome

medial shelf syndrome

osteochondritis dissecans

osteochondritis dissecans

RARE

haemochromatosis

haemochromatosis

recurrent haemarthroses, e.g. coagulation disorder

recurrent haemarthroses, e.g. coagulation disorder

osteosarcoma

osteosarcoma

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: X-ray.

POSSIBLE: FBC, CRP, uric acid, MRI, autoantibodies.

SMALL PRINT: HLA-B27, joint aspiration, hip or back investigations if referred pain suspected, alkaline phosphatase, serum ferritin, coagulation screen.

X-ray: may give clues to many of the possible causes, or confirmatory evidence when clinical suspicion is high – for example, with osteoarthritis, bony loose body, Paget’s, osteochondritis dissecans.

X-ray: may give clues to many of the possible causes, or confirmatory evidence when clinical suspicion is high – for example, with osteoarthritis, bony loose body, Paget’s, osteochondritis dissecans.

FBC, CRP: CRP elevated and Hb may be reduced in inflammatory polyarthritis.

FBC, CRP: CRP elevated and Hb may be reduced in inflammatory polyarthritis.

Uric acid: typically elevated in gout.

Uric acid: typically elevated in gout.

MRI: useful to assess soft tissue such as cartilage, especially if surgery is being considered.

MRI: useful to assess soft tissue such as cartilage, especially if surgery is being considered.

Autoantibodies: if inflammatory polyarthritis suspected.

Autoantibodies: if inflammatory polyarthritis suspected.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

HLA-B27: a high prevalence in spondoarthritides.

Joint aspiration: may be diagnostically useful if an effusion is present – for example, revealing positively birefringent crystals in pseudogout. In practice, usually performed after specialist referral.

Joint aspiration: may be diagnostically useful if an effusion is present – for example, revealing positively birefringent crystals in pseudogout. In practice, usually performed after specialist referral.

Hip or back investigations: appropriate radiology may be necessary if it is thought the knee pain is referred from these areas.

Hip or back investigations: appropriate radiology may be necessary if it is thought the knee pain is referred from these areas.

Alkaline phosphatase: elevated in Paget’s.

Alkaline phosphatase: elevated in Paget’s.

Serum ferritin: elevated in haemochromatosis.

Serum ferritin: elevated in haemochromatosis.

Coagulation screen: if coagulopathy suspected.

Coagulation screen: if coagulopathy suspected.

Patients place great value on X-rays whereas, in practice, they may contribute little to management of straightforward recurrent knee pain. To prevent an unsatisfactory outcome, consider proactively broaching the fact that an X-ray may be unnecessary.

Patients place great value on X-rays whereas, in practice, they may contribute little to management of straightforward recurrent knee pain. To prevent an unsatisfactory outcome, consider proactively broaching the fact that an X-ray may be unnecessary.

Insisting that the patient accurately localises the pain – if possible – may usefully limit the diagnostic possibilities.

Insisting that the patient accurately localises the pain – if possible – may usefully limit the diagnostic possibilities.

‘Straightforward’ osteoarthritis can become quite suddenly more painful, often for no obvious reason – exacerbations and remissions are part of the natural history of the disease.

‘Straightforward’ osteoarthritis can become quite suddenly more painful, often for no obvious reason – exacerbations and remissions are part of the natural history of the disease.

Keen sports people often present with recurrent knee pain and are unlikely to indulge in the GP’s time-honoured ‘wait and see’ approach. Earlier investigation or intervention may prove necessary.

Keen sports people often present with recurrent knee pain and are unlikely to indulge in the GP’s time-honoured ‘wait and see’ approach. Earlier investigation or intervention may prove necessary.

Do not forget that knee pain may be referred – if the cause isn’t immediately apparent, examine the hip, especially in children.

Do not forget that knee pain may be referred – if the cause isn’t immediately apparent, examine the hip, especially in children.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is quite easily missed in casualty in the acute stage. It may only present later with an unstable knee.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is quite easily missed in casualty in the acute stage. It may only present later with an unstable knee.

Osteosarcomas are rare – but most commonly occur near the knee. Beware of unexplained constant, increasing pain waking the patient at night. Swelling and inflammation will only appear later.

Osteosarcomas are rare – but most commonly occur near the knee. Beware of unexplained constant, increasing pain waking the patient at night. Swelling and inflammation will only appear later.

![]()

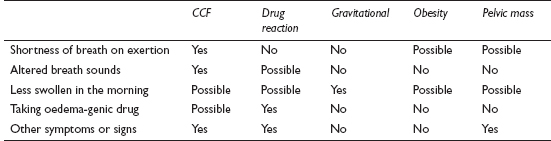

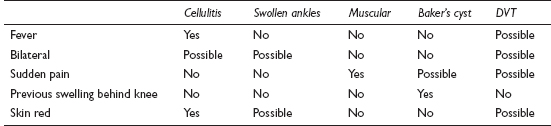

This is one of the commonest presenting complaints in the elderly and, in this age group, may be linked to recurrent falls. As a result, it is frequently the reason for a home visit request. In younger age groups, it is much rarer, but much more likely to signify serious pathology.

![]()

COMMON

congestive cardiac failure (CCF)

congestive cardiac failure (CCF)

drug reaction – especially calcium antagonists

drug reaction – especially calcium antagonists

gravitational (venous insufficiency, often with poor mobility)

gravitational (venous insufficiency, often with poor mobility)

obesity

obesity

pelvic mass (including pregnancy)

pelvic mass (including pregnancy)

OCCASIONAL

cirrhosis

cirrhosis

premenstrual syndrome

premenstrual syndrome

anaemia

anaemia

renal: acute or chronic nephritis, nephrotic syndrome

renal: acute or chronic nephritis, nephrotic syndrome

protein-losing enteropathy, e.g. coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease

protein-losing enteropathy, e.g. coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease

RARE

malnutrition

malnutrition

inferior vena cava thrombosis

inferior vena cava thrombosis

filariasis

filariasis

Milroy’s disease (hereditary lymphoedema)

Milroy’s disease (hereditary lymphoedema)

ancylostomiasis (hookworm)

ancylostomiasis (hookworm)

angioneurotic oedema

angioneurotic oedema

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, FBC, U&E, LFT.

POSSIBLE: TFT.

SMALL PRINT: CXR, pelvic ultrasound, further investigation of underlying cause.

Urinalysis: for proteinuria.

Urinalysis: for proteinuria.

FBC: look for anaemia of chronic disorder, raised MCV (alcohol abuse).

FBC: look for anaemia of chronic disorder, raised MCV (alcohol abuse).

U&E: will reveal underlying renal failure; sodium low in CCF and cirrhosis.

U&E: will reveal underlying renal failure; sodium low in CCF and cirrhosis.

LFT: may reveal hypoproteinaemia (e.g. in cirrhosis, protein-losing enteropathy and nephrotic syndrome).

LFT: may reveal hypoproteinaemia (e.g. in cirrhosis, protein-losing enteropathy and nephrotic syndrome).

CXR: pulmonary oedema and pleural effusion in CCF.

CXR: pulmonary oedema and pleural effusion in CCF.

Pelvic ultrasound: for pelvic mass.

Pelvic ultrasound: for pelvic mass.

Further investigation of underlying cause: this might involve ECG, BNP and echocardiography (CCF), CT scan (pelvic mass), renal biopsy (nephritis) and bowel investigations (enteropathy).

Further investigation of underlying cause: this might involve ECG, BNP and echocardiography (CCF), CT scan (pelvic mass), renal biopsy (nephritis) and bowel investigations (enteropathy).

In the elderly, the cause is often multifactorial, with immobility playing a major role.

In the elderly, the cause is often multifactorial, with immobility playing a major role.

Proper assessment can take time: consider spreading the work over a couple of consultations, using the intervening time to arrange and assess investigations.

Proper assessment can take time: consider spreading the work over a couple of consultations, using the intervening time to arrange and assess investigations.

Ankle swelling is usually symmetrical, though venous insufficiency in particular can affect one side much more than the other. But if only one ankle is swollen, consider deep vein thrombosis, a ruptured Baker’s cyst or cellulitis.

Ankle swelling is usually symmetrical, though venous insufficiency in particular can affect one side much more than the other. But if only one ankle is swollen, consider deep vein thrombosis, a ruptured Baker’s cyst or cellulitis.

Don’t forget that many drugs (such as calcium antagonists and NSAIDs) can cause marked ankle swelling.

Don’t forget that many drugs (such as calcium antagonists and NSAIDs) can cause marked ankle swelling.

If no cause is obvious in an elderly person, examine the abdomen and also consider a rectal examination.

If no cause is obvious in an elderly person, examine the abdomen and also consider a rectal examination.

The younger the patient, the greater the chance of significant pathology – especially renal.

The younger the patient, the greater the chance of significant pathology – especially renal.

Marked swelling of recent and sudden onset is likely to be significant regardless of age.

Marked swelling of recent and sudden onset is likely to be significant regardless of age.

![]()

Such has been the publicity about ‘economy class syndrome’ that this presentation – and the closely related symptom, ‘calf pain’ (see p. 288) – has become quite common. The worry the patient has about a possible DVT can prove quite ‘infectious’, with the GP anxious not to miss this significant problem. In most cases, a careful history, backed up by appropriate examination, should reveal the true cause.

![]()

COMMON

cellulitis

cellulitis

most causes of swollen ankles (see p. 312)

most causes of swollen ankles (see p. 312)

muscle strain/rupture (especially rupture of plantaris tendon)

muscle strain/rupture (especially rupture of plantaris tendon)

ruptured Baker’s cyst

ruptured Baker’s cyst

DVT

DVT

OCCASIONAL

ruptured Achilles tendon

ruptured Achilles tendon

varicose eczema

varicose eczema

phlebitis

phlebitis

RARE

muscle herniation through fascia (especially tibialis anterior)

muscle herniation through fascia (especially tibialis anterior)

muscular neoplasm

muscular neoplasm

pseudohypertrophy (as in muscular dystrophy)

pseudohypertrophy (as in muscular dystrophy)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none (unless sent to hospital).

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP and other investigations for swollen ankles (see p. 312); usually in hospital – D-dimer, ultrasound, venography.

SMALL PRINT: (in hospital) radio-iodine labelled fibrinogen uptake test.

FBC, ESR/CRP: elevated white cell count and ESR/CRP in cellulitis.

FBC, ESR/CRP: elevated white cell count and ESR/CRP in cellulitis.

D-dimer: raised level suggests DVT but is not conclusive.

D-dimer: raised level suggests DVT but is not conclusive.

Ultrasound: may help diagnose DVT and useful in confirming ruptured Baker’s cyst as the cause.

Ultrasound: may help diagnose DVT and useful in confirming ruptured Baker’s cyst as the cause.

Venography, radio-iodine labelled fibrinogen uptake test: hospital test which may be used to confirm DVT.

Venography, radio-iodine labelled fibrinogen uptake test: hospital test which may be used to confirm DVT.

The swelling resulting from a muscle rupture can be impressive – but a typical history with pain (described as ‘Like being shot in the calf’) preceding the swelling should clinch the correct diagnosis.

The swelling resulting from a muscle rupture can be impressive – but a typical history with pain (described as ‘Like being shot in the calf’) preceding the swelling should clinch the correct diagnosis.

Varicose eczema is often misdiagnosed as cellulitis. Clues are that it is commonly bilateral, itches more than hurts and is not accompanied by fever.

Varicose eczema is often misdiagnosed as cellulitis. Clues are that it is commonly bilateral, itches more than hurts and is not accompanied by fever.

Anxiety about possible DVT may cloud the presentation: careful questioning may reveal that swelling is, in fact, long-standing and/or bilateral, making DVT very unlikely.

Anxiety about possible DVT may cloud the presentation: careful questioning may reveal that swelling is, in fact, long-standing and/or bilateral, making DVT very unlikely.

Patients with unexplained DVT are three to four times more likely than controls to have an underlying malignancy – so, once the DVT has been dealt with, consider appropriate investigation.

Patients with unexplained DVT are three to four times more likely than controls to have an underlying malignancy – so, once the DVT has been dealt with, consider appropriate investigation.

In high-risk patients – such as those who have just returned from a long haul flight – your index of suspicion for DVT should be raised.

In high-risk patients – such as those who have just returned from a long haul flight – your index of suspicion for DVT should be raised.

When the history suggests muscular rupture, ensure that the Achilles tendon is intact.

When the history suggests muscular rupture, ensure that the Achilles tendon is intact.