BLISTERS (VESICLES AND BULLAE)

![]()

The GP overview

Blisters are skin swellings containing free fluid. Up to 5 mm they are called vesicles, larger than 5 mm they are called bullae. The fluid can be lymph, serum, extracellular fluid or blood. Some conditions cause both kinds of blister, but others mainly one or other type. Pustules are dealt with elsewhere (see p. 403).

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

trauma: skin friction, burns (thermal and chemical), insect bites

trauma: skin friction, burns (thermal and chemical), insect bites

herpes simplex

herpes simplex

herpes zoster

herpes zoster

childhood viruses: hand, foot and mouth disease, chickenpox

childhood viruses: hand, foot and mouth disease, chickenpox

eczema (pompholyx and other acute eczemas)

eczema (pompholyx and other acute eczemas)

OCCASIONAL

pemphigus and pemphigoid

pemphigus and pemphigoid

dermatitis herpetiformis

dermatitis herpetiformis

secondary to leg oedema (various causes)

secondary to leg oedema (various causes)

bullous impetigo

bullous impetigo

drug reactions, e.g. ACE inhibitors, penicillamine, barbiturates

drug reactions, e.g. ACE inhibitors, penicillamine, barbiturates

erythema multiforme

erythema multiforme

RARE

pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis

pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis

porphyria

porphyria

toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s syndrome)

toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s syndrome)

epidermolysis bullosa

epidermolysis bullosa

allergic vasculitis

allergic vasculitis

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

There are unlikely to be any investigations that will prove useful in primary care. Usually, the problem is either self-limiting or the cause obvious; in obscure cases, referral may result in skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis. Patch testing may also be useful to identify possible allergens in contact dermatitis, especially if occupational.

TOP TIPS

Herpes zoster involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve will affect the eye in about 50% of cases. The likelihood is increased if there are blisters on the side of the nose. Ensure that the patient knows to seek help urgently if the eye becomes red or painful, or there is blurring of vision.

Herpes zoster involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve will affect the eye in about 50% of cases. The likelihood is increased if there are blisters on the side of the nose. Ensure that the patient knows to seek help urgently if the eye becomes red or painful, or there is blurring of vision.

In uncomplicated herpes zoster, explain the natural history of the condition to the patient, resolving any worries (old wives’ tales abound) and warning about the possibility of post-herpetic neuralgia.

In uncomplicated herpes zoster, explain the natural history of the condition to the patient, resolving any worries (old wives’ tales abound) and warning about the possibility of post-herpetic neuralgia.

Follow up unexplained rashes. The bullae of pemphigoid, for example, may be preceded by itching, erythema and urticaria by several weeks.

Follow up unexplained rashes. The bullae of pemphigoid, for example, may be preceded by itching, erythema and urticaria by several weeks.

Herpes simplex and varicella zoster infections can become severe and disseminated in the immunosuppressed: admit. Similarly, herpes simplex can result in a serious reaction (Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption) in patients with atopic eczema.

Herpes simplex and varicella zoster infections can become severe and disseminated in the immunosuppressed: admit. Similarly, herpes simplex can result in a serious reaction (Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption) in patients with atopic eczema.

Pregnant women with chickenpox are at significant risk of severe varicella pneumonia; there are also risks to the foetus. Follow the detailed guidance in the ‘Green Book’ (Immunisation against Infectious Disease, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office) when dealing with pregnant women who have been in contact with chickenpox.

Pregnant women with chickenpox are at significant risk of severe varicella pneumonia; there are also risks to the foetus. Follow the detailed guidance in the ‘Green Book’ (Immunisation against Infectious Disease, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office) when dealing with pregnant women who have been in contact with chickenpox.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (scalded skin syndrome) can develop rapidly in infants and children, causing serious illness. Admit urgently if you suspect this diagnosis.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (scalded skin syndrome) can develop rapidly in infants and children, causing serious illness. Admit urgently if you suspect this diagnosis.

Pemphigus is a serious condition affecting a younger age group (usually middle-aged) than pemphigoid. Inpatient care is usually required.

Pemphigus is a serious condition affecting a younger age group (usually middle-aged) than pemphigoid. Inpatient care is usually required.

ERYTHEMA

![]()

The GP overview

Erythema is a reddening of the skin due to persistent dilation of superficial blood vessels, and can be local or generalised. It is distinguished from flushing (see p. 197) by its permanence: flushing is transient.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

cellulitis

cellulitis

gout

gout

burns: thermal, chemical, sunburn

burns: thermal, chemical, sunburn

toxic erythema: drugs (e.g. antibiotics, NSAIDs), bacteria (e.g. scarlet fever), viruses (e.g. measles, slapped cheek syndrome)

toxic erythema: drugs (e.g. antibiotics, NSAIDs), bacteria (e.g. scarlet fever), viruses (e.g. measles, slapped cheek syndrome)

rosacea

rosacea

OCCASIONAL

palmar erythema, e.g. pregnancy, liver disease, thyrotoxicosis

palmar erythema, e.g. pregnancy, liver disease, thyrotoxicosis

phototoxic reaction to drugs, e.g. phenothiazines, tetracyclines, diuretics

phototoxic reaction to drugs, e.g. phenothiazines, tetracyclines, diuretics

‘deck-chair legs’ (prolonged immobility)

‘deck-chair legs’ (prolonged immobility)

erythema multiforme (various causes)

erythema multiforme (various causes)

systemic lupus erythematosus (erythematous, photosensitive butterfly rash)

systemic lupus erythematosus (erythematous, photosensitive butterfly rash)

erythema ab igne (reticulate pattern)

erythema ab igne (reticulate pattern)

RARE

fixed drug eruption

fixed drug eruption

livedo reticularis: connective tissue disease

livedo reticularis: connective tissue disease

seroconversion rash of HIV

seroconversion rash of HIV

erythema nodosum: sarcoidosis, streptococci, tuberculosis, drugs

erythema nodosum: sarcoidosis, streptococci, tuberculosis, drugs

erythema induratum (Bazin’s disease: tuberculosis)

erythema induratum (Bazin’s disease: tuberculosis)

erythema chronicum migrans: Lyme disease

erythema chronicum migrans: Lyme disease

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: uric acid (if possible gout).

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, LFT, TFT.

SMALL PRINT: autoimmune studies, serology, CXR, ASO titre.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in significant infection; Hb may be reduced (normochromic normocytic) in connective tissue disorder.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in significant infection; Hb may be reduced (normochromic normocytic) in connective tissue disorder.

Autoimmune studies: if connective tissue disorder a possibility.

Autoimmune studies: if connective tissue disorder a possibility.

Serology: may help if suspect infective cause for erythema multiforme; also useful in assessing immune status in a pregnant woman exposed to slapped cheek syndrome, and in diagnosis of HIV infection and Lyme disease.

Serology: may help if suspect infective cause for erythema multiforme; also useful in assessing immune status in a pregnant woman exposed to slapped cheek syndrome, and in diagnosis of HIV infection and Lyme disease.

Uric acid: to confirm clinical suspicion of gout (when attack has subsided) especially if considering allopurinol.

Uric acid: to confirm clinical suspicion of gout (when attack has subsided) especially if considering allopurinol.

LFT, TFT: if palmar erythema present in non-pregnant patient – to detect alcohol excess or hyperthyroidism.

LFT, TFT: if palmar erythema present in non-pregnant patient – to detect alcohol excess or hyperthyroidism.

Other investigations for erythema nodosum: if a non-drug cause is possible, investigations likely to include CXR (for TB, sarcoidosis) and ASO titre (for streptococcal infection).

Other investigations for erythema nodosum: if a non-drug cause is possible, investigations likely to include CXR (for TB, sarcoidosis) and ASO titre (for streptococcal infection).

TOP TIPS

Toxic erythema caused by drugs tends to be itchy; if due to infection, it does not irritate but is accompanied by fever.

Toxic erythema caused by drugs tends to be itchy; if due to infection, it does not irritate but is accompanied by fever.

Remember that there is often a delay before a drug causes toxic erythema – therefore, symptoms may only appear after a course of treatment (especially antibiotics) has been completed.

Remember that there is often a delay before a drug causes toxic erythema – therefore, symptoms may only appear after a course of treatment (especially antibiotics) has been completed.

‘Deck-chair legs’ is erythema of the lower legs, sometimes with oedema and blistering, in the immobile. It tends to be mistakenly diagnosed as persistent or recurrent cellulitis.

‘Deck-chair legs’ is erythema of the lower legs, sometimes with oedema and blistering, in the immobile. It tends to be mistakenly diagnosed as persistent or recurrent cellulitis.

A violent local erythema, rapidly darkening and blistering and recurring at the same site, suggests a fixed drug eruption.

A violent local erythema, rapidly darkening and blistering and recurring at the same site, suggests a fixed drug eruption.

Erythema nodosum and multiforme may be caused by significant disease, including, very occasionally, malignancy. If the patient is generally unwell or has other significant symptoms, investigate urgently or refer.

Erythema nodosum and multiforme may be caused by significant disease, including, very occasionally, malignancy. If the patient is generally unwell or has other significant symptoms, investigate urgently or refer.

Take a travel history: Lyme disease is endemic in forested areas. If not diagnosed and treated early, it can have significant complications.

Take a travel history: Lyme disease is endemic in forested areas. If not diagnosed and treated early, it can have significant complications.

Erythema multiforme with blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes is Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Though rare, it is a very serious illness requiring urgent hospital treatment.

Erythema multiforme with blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes is Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Though rare, it is a very serious illness requiring urgent hospital treatment.

Enquire about joint symptoms: many causes of erythema (e.g. erythema multiforme, butterfly rash, livedo reticularis) are linked to a connective tissue isorder.

Enquire about joint symptoms: many causes of erythema (e.g. erythema multiforme, butterfly rash, livedo reticularis) are linked to a connective tissue isorder.

Remember to take a drug history, including over-the-counter medications. This may reveal the underlying cause in toxic erythema, erythema nodosum and multiforme, and phototoxicity.

Remember to take a drug history, including over-the-counter medications. This may reveal the underlying cause in toxic erythema, erythema nodosum and multiforme, and phototoxicity.

Remember that parvovirus can cause serious problems in pregnancy – check serology in women with suggestive symptoms, or exposure to a case.

Remember that parvovirus can cause serious problems in pregnancy – check serology in women with suggestive symptoms, or exposure to a case.

MACULES

![]()

The GP overview

A macule is a flat, demarcated, abnormally coloured area of skin of any size. It may be red (e.g. drug eruption), dark red (e.g. purpura), brown (e.g. a flat mole) or white (e.g. pityriasis versicolor). Purpura is described elsewhere (see p. 400). There is some crossover between erythema (see p. 390) and red macules.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

drug reaction/allergy

drug reaction/allergy

flat mole (junctional naevus)

flat mole (junctional naevus)

non-specific viral exanthem

non-specific viral exanthem

sun-induced freckles (including solar lentigines)

sun-induced freckles (including solar lentigines)

chloasma

chloasma

OCCASIONAL

measles and rubella

measles and rubella

post-inflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation

post-inflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation

café au lait spot (creamy brown) and Mongolian spot (brown or slate-grey)

café au lait spot (creamy brown) and Mongolian spot (brown or slate-grey)

Berloque dermatitis (brown: chemical photosensitisation, e.g. bergamot oil)

Berloque dermatitis (brown: chemical photosensitisation, e.g. bergamot oil)

depigmentation: vitiligo, pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba

depigmentation: vitiligo, pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba

RARE

infections: macular syphilide, tuberculoid leprosy, typhoid (rose spots in 40%)

infections: macular syphilide, tuberculoid leprosy, typhoid (rose spots in 40%)

Albright’s syndrome

Albright’s syndrome

neurofibromatosis (associated with more than six café au lait spots)

neurofibromatosis (associated with more than six café au lait spots)

pathological freckles: Hutchinson’s freckle, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

pathological freckles: Hutchinson’s freckle, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

naevus anaemicus (permanent vasoconstriction due to neurovascular abnormality)

naevus anaemicus (permanent vasoconstriction due to neurovascular abnormality)

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

There are very few relevant investigations to consider and they would be required only exceptionally, as the diagnosis is usually clinical: skin scrapings for mycology or fluorescence under Wood’s light may help in the diagnosis of pityriasis versicolor; acute and convalescent serum samples may confirm rubella; serology for syphilis may be appropriate with an unusual macular rash; and very occasionally, a skin biopsy may be required to clinch an obscure diagnosis.

TOP TIPS

A drug eruption can take 2 weeks to appear from the time of the first dose – so don’t be misled by the fact that a course of antibiotics may have been completed some days before the related drug rash develops.

A drug eruption can take 2 weeks to appear from the time of the first dose – so don’t be misled by the fact that a course of antibiotics may have been completed some days before the related drug rash develops.

Pityriasis versicolor may be misdiagnosed as vitiligo. If in doubt, take scrapings for mycology or examine under Wood’s light.

Pityriasis versicolor may be misdiagnosed as vitiligo. If in doubt, take scrapings for mycology or examine under Wood’s light.

Odd lines of hyperpigmentation on the sides of the neck are likely to be Berloque dermatitis – a photosensitive rash caused by oil of bergamot, present in perfumes.

Odd lines of hyperpigmentation on the sides of the neck are likely to be Berloque dermatitis – a photosensitive rash caused by oil of bergamot, present in perfumes.

Hutchinson’s freckle is a giant, variegated freckle, seen in elderly sun-exposed skin. There is a high risk of malignant change, so refer.

Hutchinson’s freckle is a giant, variegated freckle, seen in elderly sun-exposed skin. There is a high risk of malignant change, so refer.

Rubella is rare, but may become commoner as a result of media coverage of ‘immunisation scares’. Establish whether or not a young woman presenting with a rubella-type rash is pregnant – if she is, confirm her rubella status.

Rubella is rare, but may become commoner as a result of media coverage of ‘immunisation scares’. Establish whether or not a young woman presenting with a rubella-type rash is pregnant – if she is, confirm her rubella status.

A child with very many freckles on and around the lips may have Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. This is associated with small bowel polyposis.

A child with very many freckles on and around the lips may have Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. This is associated with small bowel polyposis.

Vitiligo tends to have a poor prognosis in Caucasians, especially if it is widespread and affecting lips and extremities.

Vitiligo tends to have a poor prognosis in Caucasians, especially if it is widespread and affecting lips and extremities.

NODULES

![]()

The GP overview

Skin nodules are larger than papules – more than 5 mm diameter. However, their depth is more significant clinically than their width. Some are free within the dermis; others are fixed to skin above or subcutaneous tissue below. The causes are various; the patient is usually concerned about the cosmetic appearance or malignant potential.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

sebaceous cyst

sebaceous cyst

lipoma

lipoma

basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

warts

warts

xanthoma

xanthoma

OCCASIONAL

dermatofibroma (histiocytoma)

dermatofibroma (histiocytoma)

squamous cell carcinoma

squamous cell carcinoma

nodulocystic acne

nodulocystic acne

kerato-acanthoma

kerato-acanthoma

gouty tophi

gouty tophi

chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis

chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis

rheumatoid nodules and Heberden’s nodes

rheumatoid nodules and Heberden’s nodes

pyogenic granuloma

pyogenic granuloma

RARE

malignant melanoma (becoming more common in the UK)

malignant melanoma (becoming more common in the UK)

vasculitic: erythema nodosum, nodular vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa

vasculitic: erythema nodosum, nodular vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa

atypical infections (e.g. leprosy, treponema, lupus vulgaris, fish tank and swimming pool granuloma, actinomycosis)

atypical infections (e.g. leprosy, treponema, lupus vulgaris, fish tank and swimming pool granuloma, actinomycosis)

lymphoma and metastatic secondary carcinoma

lymphoma and metastatic secondary carcinoma

sarcoidosis

sarcoidosis

pretibial myxoedema

pretibial myxoedema

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: none (skin biopsy or cytology if doubt about the lesion or clinical diagnosis of possible carcinoma).

POSSIBLE: lipid profile, FBC, ESR/CRP, urate, rheumatoid factor, urinalysis.

SMALL PRINT: TFT, Kveim test, further investigations guided by clinical picture (see below).

Excision biopsy is the definitive investigation for achieving a diagnosis; cytology from skin scrapings can be used to diagnose BCC.

Excision biopsy is the definitive investigation for achieving a diagnosis; cytology from skin scrapings can be used to diagnose BCC.

Lipid profile: xanthomata require a full lipid profile to define the underlying hyperlipidaemia.

Lipid profile: xanthomata require a full lipid profile to define the underlying hyperlipidaemia.

Urinalysis: if suspect inflammatory or vasculitic skin lumps, as may reveal proteinuria if associated with systemic and renal disorders.

Urinalysis: if suspect inflammatory or vasculitic skin lumps, as may reveal proteinuria if associated with systemic and renal disorders.

FBC and ESR/CRP: ESR/CRP raised in inflammatory disorders and malignancy; may also reveal anaemia of chronic disease or malignancy (including lymphoma).

FBC and ESR/CRP: ESR/CRP raised in inflammatory disorders and malignancy; may also reveal anaemia of chronic disease or malignancy (including lymphoma).

Check urate if gouty tophi are clinically likely.

Check urate if gouty tophi are clinically likely.

Rheumatoid factor: nodules are usually associated with positive rheumatoid factor.

Rheumatoid factor: nodules are usually associated with positive rheumatoid factor.

TFT: to diagnose Graves’s disease with pretibial myxoedema.

TFT: to diagnose Graves’s disease with pretibial myxoedema.

Kveim test: may contribute to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Kveim test: may contribute to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Further investigations according to clinical picture: some lesions, such as erythema nodosum, may require further investigation to establish the underlying cause; histological confirmation of skin secondaries may similarly require further assessment, although the overall condition of the patient may mean this is a futile exercise.

Further investigations according to clinical picture: some lesions, such as erythema nodosum, may require further investigation to establish the underlying cause; histological confirmation of skin secondaries may similarly require further assessment, although the overall condition of the patient may mean this is a futile exercise.

TOP TIPS

Look at the lesion under the magnifying glass – this may reveal suspicious signs such as ulceration or a rolled, pearly edge.

Look at the lesion under the magnifying glass – this may reveal suspicious signs such as ulceration or a rolled, pearly edge.

In uncertain cases which do not require urgent attention, record your findings carefully (including precise dimensions) and review in a month or two.

In uncertain cases which do not require urgent attention, record your findings carefully (including precise dimensions) and review in a month or two.

Stoical patients may underestimate the significance of a suspicious lesion, particularly if you discover it during a routine examination – if you are referring them for biopsy, impress upon them the need to attend their appointment.

Stoical patients may underestimate the significance of a suspicious lesion, particularly if you discover it during a routine examination – if you are referring them for biopsy, impress upon them the need to attend their appointment.

Establish the patient’s concern, which will usually centre on worries about cosmetic appearance or cancer. This will result in a more functional consultation and a more satisfied patient.

Establish the patient’s concern, which will usually centre on worries about cosmetic appearance or cancer. This will result in a more functional consultation and a more satisfied patient.

Night sweats and itching with skin nodules raises the suspicion of lymphoma. Examine lymph nodes, liver and spleen carefully.

Night sweats and itching with skin nodules raises the suspicion of lymphoma. Examine lymph nodes, liver and spleen carefully.

The elderly patient complaining of a lesion in a sun-exposed area which ‘just won’t heal’ may well have a squamous or basal cell carcinoma.

The elderly patient complaining of a lesion in a sun-exposed area which ‘just won’t heal’ may well have a squamous or basal cell carcinoma.

The appearance of a nodule in a mole is highly significant and requires referral.

The appearance of a nodule in a mole is highly significant and requires referral.

A patient with nodulocystic acne requires referral to a dermatologist for possible treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid.

A patient with nodulocystic acne requires referral to a dermatologist for possible treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid.

The unwell middle-aged or elderly patient who develops bizarre and widespread skin nodules over a period of a few weeks probably has an underlying carcinoma.

The unwell middle-aged or elderly patient who develops bizarre and widespread skin nodules over a period of a few weeks probably has an underlying carcinoma.

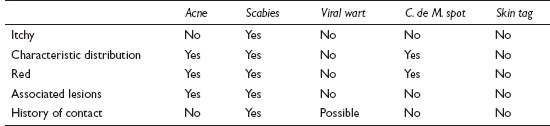

PAPULES

![]()

The GP overview

Papules are solid, circumscribed skin elevations up to 5 mm in diameter. If they are larger, they are called nodules – these are dealt with elsewhere (see p. 395). (Clearly, many nodules start life as a papule; to avoid confusion, if they are generally ‘nodular’ by the time they present to the GP, then they are dealt with in that section, and not repeated here.) They are usually round but the shape, and the colour, may vary. They may be transitional lesions, e.g. becoming vesicular, or about to ulcerate.

NOTE: there are more causes of papules than can be listed here. This is a sensible selection.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

acne

acne

scabies

scabies

viral wart and molluscum contagiosum

viral wart and molluscum contagiosum

Campbell de Morgan spot

Campbell de Morgan spot

skin tag

skin tag

OCCASIONAL

viral illness

viral illness

milia

milia

insect bites

insect bites

early seborrhoeic wart

early seborrhoeic wart

xanthomata

xanthomata

guttate psoriasis

guttate psoriasis

pityriasis lichenoides chronica, lichen planus

pityriasis lichenoides chronica, lichen planus

prickly heat

prickly heat

keratosis pilaris

keratosis pilaris

RARE

malignant melanoma, early basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma

malignant melanoma, early basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma

Darier’s disease

Darier’s disease

acanthosis nigricans

acanthosis nigricans

pseudoxanthoma elasticum

pseudoxanthoma elasticum

tuberous sclerosis

tuberous sclerosis

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

In practice, very few investigations are needed with this presentation: a lipid screen is required in the presence of xanthomata; genital warts require referral for screening for other STDs; thorough investigation may be needed in the very rare case where underlying malignancy is possible (e.g. acanthosis nigricans); and obscure rashes or solitary papules may occasionally require excision biopsy for a definitive diagnosis.

TOP TIPS

Bear in mind that skin cancer is usually uppermost in the patient’s mind, especially in subacute or chronic cases – so provide appropriate reassurance.

Bear in mind that skin cancer is usually uppermost in the patient’s mind, especially in subacute or chronic cases – so provide appropriate reassurance.

In obscure solitary lesions, record clinical findings carefully and arrange to review in due course.

In obscure solitary lesions, record clinical findings carefully and arrange to review in due course.

Itchy, asymmetrical grouped papules are likely to be insect bites, although the patient may take some convincing!

Itchy, asymmetrical grouped papules are likely to be insect bites, although the patient may take some convincing!

An enlarging dark blue or blue-black papule may be a malignant melanoma, blue naevus or Kaposi’s sarcoma. Refer for urgent opinion.

An enlarging dark blue or blue-black papule may be a malignant melanoma, blue naevus or Kaposi’s sarcoma. Refer for urgent opinion.

Brown, skin-coloured papules crowded around the nose of a child may be tuberous sclerosis. This can be associated with serious systemic pathology so refer for expert opinion.

Brown, skin-coloured papules crowded around the nose of a child may be tuberous sclerosis. This can be associated with serious systemic pathology so refer for expert opinion.

An intensely itchy papular rash which is worse at night and has no other obvious cause is likely to be scabies, even if scabetic burrows are not evident – treat on suspicion.

An intensely itchy papular rash which is worse at night and has no other obvious cause is likely to be scabies, even if scabetic burrows are not evident – treat on suspicion.

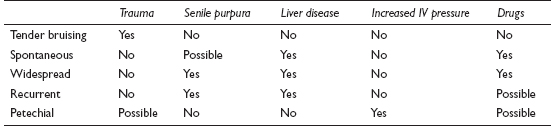

PURPURA AND PETECHIAE

![]()

The GP overview

Purpura are reddish-purple lesions which do not blanch with pressure. When less than 1 cm in diameter, they are called petechiae; if larger, they are known as ecchymoses. The problem often presents as ‘bruising easily’ – a common ‘while I’m here’ complaint in primary care. Most cases are normal, with causative minor trauma simply being forgotten or unnoticed.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

trauma

trauma

senile purpura

senile purpura

liver disease (especially alcoholic cirrhosis)

liver disease (especially alcoholic cirrhosis)

increased intravascular pressure, e.g. coughing, vomiting, gravitational

increased intravascular pressure, e.g. coughing, vomiting, gravitational

drugs, e.g. steroids, warfarin, aspirin

drugs, e.g. steroids, warfarin, aspirin

OCCASIONAL

vasculitis, e.g. Henoch–Schönlein purpura, connective tissue disorders

vasculitis, e.g. Henoch–Schönlein purpura, connective tissue disorders

thrombocytopenia, e.g. idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP), bone marrow damage (e.g. lymphoma, leukaemia, cytotoxics), aplastic anaemia

thrombocytopenia, e.g. idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP), bone marrow damage (e.g. lymphoma, leukaemia, cytotoxics), aplastic anaemia

renal failure

renal failure

infective endocarditis

infective endocarditis

RARE

paraproteinaemias, e.g. cryoglobulinaemia

paraproteinaemias, e.g. cryoglobulinaemia

inherited clotting disorders, e.g. haemophilia, Christmas disease, von Willebrand’s disease

inherited clotting disorders, e.g. haemophilia, Christmas disease, von Willebrand’s disease

infections, e.g. meningococcal septicaemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever

infections, e.g. meningococcal septicaemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever

vitamin C and K deficiency

vitamin C and K deficiency

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

congenital vessel wall abnormalities, e.g. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

congenital vessel wall abnormalities, e.g. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: FBC, ESR/CRP, INR (if on warfarin).

POSSIBLE: LFT, U&E, coagulation screen, plasma electrophoresis.

SMALL PRINT: autoimmune testing, further hospital investigations (see below).

FBC, ESR/CRP: FBC may reveal thrombocytopenia or evidence of blood dyscrasia. ESR/CRP and WCC may be raised in blood dyscrasia, connective tissue disorder and infection.

FBC, ESR/CRP: FBC may reveal thrombocytopenia or evidence of blood dyscrasia. ESR/CRP and WCC may be raised in blood dyscrasia, connective tissue disorder and infection.

LFT, U&E: for underlying liver or renal disease.

LFT, U&E: for underlying liver or renal disease.

INR: if on warfarin.

INR: if on warfarin.

Autoimmune testing: if possible connective tissue disease causing vasculitis.

Autoimmune testing: if possible connective tissue disease causing vasculitis.

Coagulation screen: to test haemostatic function, e.g. bleeding time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time.

Coagulation screen: to test haemostatic function, e.g. bleeding time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time.

Plasma electrophoresis: for hypergammaglobulinaemia, paraproteinaemia and cryoglobulinaemia.

Plasma electrophoresis: for hypergammaglobulinaemia, paraproteinaemia and cryoglobulinaemia.

Further investigations (usually secondary care): to investigate underlying cause, e.g. skin biopsy to confirm vasculitis, bone marrow biopsy if possible marrow infiltrate.

Further investigations (usually secondary care): to investigate underlying cause, e.g. skin biopsy to confirm vasculitis, bone marrow biopsy if possible marrow infiltrate.

TOP TIPS

Multiple bruises of varying ages on the legs of young children who are otherwise well and have no other stigmata of clotting disorder or abuse are likely to be non-pathological.

Multiple bruises of varying ages on the legs of young children who are otherwise well and have no other stigmata of clotting disorder or abuse are likely to be non-pathological.

Senile purpura should be easy to diagnose from the history and examination. Reassurance, rather than investigation, is required.

Senile purpura should be easy to diagnose from the history and examination. Reassurance, rather than investigation, is required.

A few petechiae on or around the eyelids of a well child can be caused by vigorous coughing or vomiting. If the history is clear, explain the cause to the parents – but emphasise that the appearance of an identical rash elsewhere requires urgent attention.

A few petechiae on or around the eyelids of a well child can be caused by vigorous coughing or vomiting. If the history is clear, explain the cause to the parents – but emphasise that the appearance of an identical rash elsewhere requires urgent attention.

The distribution of purpura can give useful clues to the diagnosis. On the legs, platelet disorders, paraproteinaemias, Henoch–Schönlein purpura or meningococcal septicaemia are likely; lesions on the fingers and toes indicate vasculitis; and senile and steroid purpura tend to affect the back of the hands and arms.

The distribution of purpura can give useful clues to the diagnosis. On the legs, platelet disorders, paraproteinaemias, Henoch–Schönlein purpura or meningococcal septicaemia are likely; lesions on the fingers and toes indicate vasculitis; and senile and steroid purpura tend to affect the back of the hands and arms.

Purpura caused by vasculitis tend to be raised palpably above the skin.

Purpura caused by vasculitis tend to be raised palpably above the skin.

Remember that the rash of meningococcal septicaemia can appear before a child is obviously systemically unwell. If there is any suspicion that this might be the diagnosis, give parenteral penicillin and admit immediately.

Remember that the rash of meningococcal septicaemia can appear before a child is obviously systemically unwell. If there is any suspicion that this might be the diagnosis, give parenteral penicillin and admit immediately.

The absence of a family history does not exclude a significant inherited bleeding disorder: these disorders can arise spontaneously.

The absence of a family history does not exclude a significant inherited bleeding disorder: these disorders can arise spontaneously.

Take very seriously the pale patient with purpura: a bone marrow problem is likely. Arrange an urgent FBC or admit.

Take very seriously the pale patient with purpura: a bone marrow problem is likely. Arrange an urgent FBC or admit.

Always do a full surface examination of a child with bruising, not forgetting the anogenital area. Keep non-accidental injury in mind.

Always do a full surface examination of a child with bruising, not forgetting the anogenital area. Keep non-accidental injury in mind.

Never give an IM injection if a serious bleeding disorder is suspected.

Never give an IM injection if a serious bleeding disorder is suspected.

PUSTULES

![]()

The GP overview

Pustules are raised lesions less than 0.5 cm in diameter containing a yellow fluid. They signify infection to most people, and will often present in an urgent appointment, as they are likely to have appeared suddenly. Patients will often expect antibiotic treatment. This will not always be necessary, so be prepared to offer a clear explanation and an appropriate alternative.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

impetigo

impetigo

other staphylococcal infections, e.g. early boils, folliculitis, sycosis barbae

other staphylococcal infections, e.g. early boils, folliculitis, sycosis barbae

herpes simplex and zoster

herpes simplex and zoster

acne vulgaris

acne vulgaris

rosacea

rosacea

OCCASIONAL

perioral dermatitis

perioral dermatitis

hidradenitis suppurativa (axillae and groins)

hidradenitis suppurativa (axillae and groins)

candidiasis (satellite vesicopustules around moist eroded patch)

candidiasis (satellite vesicopustules around moist eroded patch)

pustular psoriasis (palmar and plantar commoner than generalised pustular psoriasis of von Zumbusch)

pustular psoriasis (palmar and plantar commoner than generalised pustular psoriasis of von Zumbusch)

RARE

dermatitis herpetiformis

dermatitis herpetiformis

Behçet’s syndrome

Behçet’s syndrome

viral: cowpox and orf (Note: chickenpox is vesicular, not pustular)

viral: cowpox and orf (Note: chickenpox is vesicular, not pustular)

hot tub folliculitis (superficial Pseudomonas infection)

hot tub folliculitis (superficial Pseudomonas infection)

drug induced

drug induced

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

There are very few investigations likely to prove useful or necessary in primary care. The presence of widespread or recurrent candidal or staphylococcal lesions might necessitate a urinalysis or blood sugar to exclude diabetes; a swab of pus may help confirm a clinically suspected infective agent; and in very obscure cases, a skin biopsy might prove helpful.

TOP TIPS

Take time to explain to the patient the nature of the problem in recurrent staphylococcal infections. Exclude diabetes, check carrier sites and reassure that the patient’s ‘hygiene’ is not in question. A prolonged course of antibiotics may be helpful.

Take time to explain to the patient the nature of the problem in recurrent staphylococcal infections. Exclude diabetes, check carrier sites and reassure that the patient’s ‘hygiene’ is not in question. A prolonged course of antibiotics may be helpful.

Check self-treatment in rosacea and perioral dermatitis. Treatment with OTC topical steroids will exacerbate the problem. Warn the patient that the condition may worsen before it improves on withdrawal of this inappropriate treatment.

Check self-treatment in rosacea and perioral dermatitis. Treatment with OTC topical steroids will exacerbate the problem. Warn the patient that the condition may worsen before it improves on withdrawal of this inappropriate treatment.

Papules and pustules around the mouth and eyes, often with a halo of pallor around the lip margin, are caused by perioral dermatitis. Treat with antibiotics, not topical steroids.

Papules and pustules around the mouth and eyes, often with a halo of pallor around the lip margin, are caused by perioral dermatitis. Treat with antibiotics, not topical steroids.

Widespread, severe and recurrent staphylococcal lesions suggest diabetes or possible immunosuppression.

Widespread, severe and recurrent staphylococcal lesions suggest diabetes or possible immunosuppression.

Localised pustular psoriasis can be very resistant to standard treatments, so have a low threshold for referral. The very rare generalised form can make the patient dangerously ill: admit urgently.

Localised pustular psoriasis can be very resistant to standard treatments, so have a low threshold for referral. The very rare generalised form can make the patient dangerously ill: admit urgently.

Remember that herpes simplex or zoster infections in the immunocompromised can become disseminated and severe.

Remember that herpes simplex or zoster infections in the immunocompromised can become disseminated and severe.

Ocular problems in rosacea can be complicated and troublesome: refer to an ophthalmologist.

Ocular problems in rosacea can be complicated and troublesome: refer to an ophthalmologist.

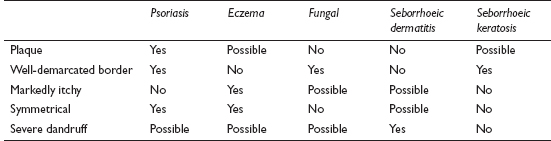

SCALES AND PLAQUES

![]()

The GP overview

Skin scales represent an abnormally fast piling up of keratinised epithelium. Scales and plaques are common at all ages and have a variety of causes. The presentation will centre on cosmetic appearance, itching, fears about serious disease or a combination of these.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

psoriasis

psoriasis

eczema (in all its various forms)

eczema (in all its various forms)

fungal infections (e.g. scalp, body, feet)

fungal infections (e.g. scalp, body, feet)

seborrhoeic dermatitis

seborrhoeic dermatitis

seborrhoeic keratosis

seborrhoeic keratosis

OCCASIONAL

lichen simplex

lichen simplex

lichen planus (usually scaly only on legs)

lichen planus (usually scaly only on legs)

solar keratosis

solar keratosis

pityriasis versicolor and rosea

pityriasis versicolor and rosea

juvenile plantar dermatosis

juvenile plantar dermatosis

guttate psoriasis (scaly papules)

guttate psoriasis (scaly papules)

RARE

malignancy: Bowen’s disease and mycosis fungoides (cutaneous T-cell lymphoma)

malignancy: Bowen’s disease and mycosis fungoides (cutaneous T-cell lymphoma)

drug induced (e.g. β-blockers and carbamazepine)

drug induced (e.g. β-blockers and carbamazepine)

ichthyosis (various forms)

ichthyosis (various forms)

keratoderma blenorrhagica (part of Reiter’s syndrome)

keratoderma blenorrhagica (part of Reiter’s syndrome)

pityriasis lichenoides chronica

pityriasis lichenoides chronica

secondary syphilis

secondary syphilis

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: Wood’s light, skin scrapings/hair samples, patch testing.

SMALL PRINT: skin biopsy, syphilis serology, FBC, ESR/CRP, fasting glucose or HbA1c.

Green fluorescence under UV (Wood’s) light is diagnostic of microsporum fungal infection.

Green fluorescence under UV (Wood’s) light is diagnostic of microsporum fungal infection.

Skin scrapings and hair samples for mycology: will help differentiate fungal infections from similar rashes.

Skin scrapings and hair samples for mycology: will help differentiate fungal infections from similar rashes.

Skin biopsy: may be the only way to achieve a firm diagnosis in obscure rashes, and is essential if malignancy suspected.

Skin biopsy: may be the only way to achieve a firm diagnosis in obscure rashes, and is essential if malignancy suspected.

Patch testing: to establish the likely allergen in allergic contact eczema.

Patch testing: to establish the likely allergen in allergic contact eczema.

Syphilis serology: if justified by clinical features or obscure pattern.

Syphilis serology: if justified by clinical features or obscure pattern.

FBC and ESR/CRP: may suggest significant underlying disease (e.g. T-cell lymphoma); ESR/CRP also elevated in Reiter’s disease.

FBC and ESR/CRP: may suggest significant underlying disease (e.g. T-cell lymphoma); ESR/CRP also elevated in Reiter’s disease.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: check for diabetes in recurrent fungal infections.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: check for diabetes in recurrent fungal infections.

TOP TIPS

To help distinguish between fungal and eczematous rashes, look at the symmetry and edges of the lesions. Fungal rashes are usually asymmetrical with a scaly, raised edge.

To help distinguish between fungal and eczematous rashes, look at the symmetry and edges of the lesions. Fungal rashes are usually asymmetrical with a scaly, raised edge.

In the presence of a fungal rash, look for infection elsewhere (e.g. groins and feet) and treat both areas, otherwise the problem is likely to recur.

In the presence of a fungal rash, look for infection elsewhere (e.g. groins and feet) and treat both areas, otherwise the problem is likely to recur.

In uncertain cases, explain to the patient that the real diagnosis may only become apparent as the rash develops (the typical example being the herald patch of pityriasis rosea looking like initially tinea corporis) – invite the patient to return for reassessment if your initial treatment proves unsuccessful.

In uncertain cases, explain to the patient that the real diagnosis may only become apparent as the rash develops (the typical example being the herald patch of pityriasis rosea looking like initially tinea corporis) – invite the patient to return for reassessment if your initial treatment proves unsuccessful.

A symmetrical, glazed, scaly and fissured rash on the soles of a trainer-loving child or adolescent is juvenile plantar dermatosis.

A symmetrical, glazed, scaly and fissured rash on the soles of a trainer-loving child or adolescent is juvenile plantar dermatosis.

Eight per cent of people with psoriasis will have arthropathy, which is usually also associated with nail changes. Check the nails and ask about joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis.

Eight per cent of people with psoriasis will have arthropathy, which is usually also associated with nail changes. Check the nails and ask about joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis.

Erythroderma – universal redness and scaling caused, rarely, by psoriasis, eczema, mycosis fungoides and drug eruptions – renders the patient systemically unwell. Urgent inpatient treatment is required.

Erythroderma – universal redness and scaling caused, rarely, by psoriasis, eczema, mycosis fungoides and drug eruptions – renders the patient systemically unwell. Urgent inpatient treatment is required.

A solitary, well-defined, slowly growing scaly plaque on the face, hands or legs of the middle-aged or elderly patient is probably Bowen’s disease – but it can easily be mistaken for an isolated patch of eczema or psoriasis.

A solitary, well-defined, slowly growing scaly plaque on the face, hands or legs of the middle-aged or elderly patient is probably Bowen’s disease – but it can easily be mistaken for an isolated patch of eczema or psoriasis.

If a pityriasis rosea-like rash extends to the palms and soles, with fever, malaise, sore throat and lymphadenopathy, consider secondary syphilis.

If a pityriasis rosea-like rash extends to the palms and soles, with fever, malaise, sore throat and lymphadenopathy, consider secondary syphilis.