![]()

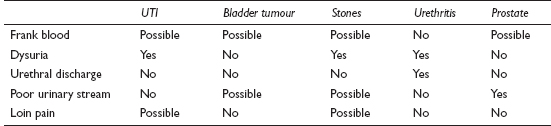

Bright red blood in the urine causes instant alarm in a patient, and usually generates an emergency appointment or an out-of-hours call. Blood may also be picked up by dipstick testing or MSU during the assessment of some other problem or in a routine medical. This is often less frightening even when disclosed to the patient, but should prompt full investigation.

![]()

COMMON

UTI

UTI

bladder tumour

bladder tumour

renal/ureteric stones

renal/ureteric stones

urethritis

urethritis

prostatic hypertrophy/carcinoma of prostate

prostatic hypertrophy/carcinoma of prostate

OCCASIONAL

jogging and hard exercise

jogging and hard exercise

renal carcinoma

renal carcinoma

chronic interstitial cystitis

chronic interstitial cystitis

anticoagulant therapy

anticoagulant therapy

nephritis/glomerulonephritis

nephritis/glomerulonephritis

RARE

renal tuberculosis

renal tuberculosis

polycystic kidney disease

polycystic kidney disease

blood dyscrasias: thrombocytopenia, haemophilia, sickle-cell disease

blood dyscrasias: thrombocytopenia, haemophilia, sickle-cell disease

infective endocarditis

infective endocarditis

schistosomiasis (common abroad)

schistosomiasis (common abroad)

trauma

trauma

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU, FBC, U&E, ACR/PCR.

POSSIBLE: PSA, ultrasound, plain abdominal X-ray, IVU, cystoscopy.

SMALL PRINT: urethral swab, CT scan, urine cytology, renal biopsy, angiography.

Urinalysis: pus cells and nitrite in UTI. Pus cells alone in urethritis, TB and bladder tumour. Presence of protein suggests renal disease.

Urinalysis: pus cells and nitrite in UTI. Pus cells alone in urethritis, TB and bladder tumour. Presence of protein suggests renal disease.

Urine microscopy and culture to establish pathogen in infection. May show casts in renal disease.

Urine microscopy and culture to establish pathogen in infection. May show casts in renal disease.

FBC and U&E help establish basic renal function and any associated anaemia or leucocytosis; consider PSA – usually elevated in prostatic carcinoma.

FBC and U&E help establish basic renal function and any associated anaemia or leucocytosis; consider PSA – usually elevated in prostatic carcinoma.

ACR/PCR: to quantify any proteinuria.

ACR/PCR: to quantify any proteinuria.

Urethral swabs if urethritis (best done at GUM clinic).

Urethral swabs if urethritis (best done at GUM clinic).

If painless haematuria, ultrasound may show renal tumour or polycystic kidneys; CT may be more useful.

If painless haematuria, ultrasound may show renal tumour or polycystic kidneys; CT may be more useful.

IVU is investigation of choice if renal/ureteric stones are suspected (when pain is present); plain abdominal X-ray useful when attack has settled (reveals 90% of stones). IVU also required if ultrasound, abdominal X-ray and cystoscopy are all negative.

IVU is investigation of choice if renal/ureteric stones are suspected (when pain is present); plain abdominal X-ray useful when attack has settled (reveals 90% of stones). IVU also required if ultrasound, abdominal X-ray and cystoscopy are all negative.

Specialist investigations include cystoscopy, urinary cytology, renal biopsy and angiography.

Specialist investigations include cystoscopy, urinary cytology, renal biopsy and angiography.

Microscopic haematuria in an asymptomatic menstruating woman can be ignored temporarily; repeat the urinalysis at mid-cycle.

Microscopic haematuria in an asymptomatic menstruating woman can be ignored temporarily; repeat the urinalysis at mid-cycle.

Remember that there are other less common causes of spurious haematuria – sometimes the blood may be coming from the rectum or vagina. Assess each case carefully and be prepared to rethink if symptoms persist but urological investigations prove negative.

Remember that there are other less common causes of spurious haematuria – sometimes the blood may be coming from the rectum or vagina. Assess each case carefully and be prepared to rethink if symptoms persist but urological investigations prove negative.

Some food pigments, beetroot and certain drugs (e.g. nitrofurantoin) can colour the urine red – confirm haematuria with urinalysis to save the patient unnecessary tests.

Some food pigments, beetroot and certain drugs (e.g. nitrofurantoin) can colour the urine red – confirm haematuria with urinalysis to save the patient unnecessary tests.

Painless frank haematuria is an ominous sign indicating possible malignancy.

Painless frank haematuria is an ominous sign indicating possible malignancy.

Beware of recent onset of recurrent cystitis with haematuria in the elderly. The underlying cause may be a bladder tumour, especially if the haematuria (micro- or macroscopic) does not settle with treatment of the infection.

Beware of recent onset of recurrent cystitis with haematuria in the elderly. The underlying cause may be a bladder tumour, especially if the haematuria (micro- or macroscopic) does not settle with treatment of the infection.

Renal tumours can sometimes present with renal colic, as blood clots in the ureters mimic the effects of stones. A useful clue is that the bleeding may precede the pain.

Renal tumours can sometimes present with renal colic, as blood clots in the ureters mimic the effects of stones. A useful clue is that the bleeding may precede the pain.

Haematuria requires emergency admission if there is significant blood loss or clot retention.

Haematuria requires emergency admission if there is significant blood loss or clot retention.

![]()

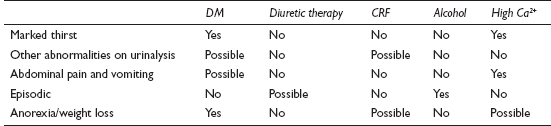

Polyuria is a highly subjective symptom and one which presents rather less often than urinary frequency (which is dealt with separately, see p. 416). Most of the causes of polyuria listed here are also, by implication, causes of polydipsia – the only causes of true polydipsia not included are those due to dehydration.

![]()

COMMON

diabetes mellitus (DM)

diabetes mellitus (DM)

diuretic therapy

diuretic therapy

chronic renal failure (CRF)

chronic renal failure (CRF)

hypercalcaemia (e.g. osteoporosis treatment, multiple bony metastases, hyperparathyroidism)

hypercalcaemia (e.g. osteoporosis treatment, multiple bony metastases, hyperparathyroidism)

alcohol

alcohol

OCCASIONAL

potassium depletion: chronic diarrhoea, diuretics, primary hyperaldosteronism

potassium depletion: chronic diarrhoea, diuretics, primary hyperaldosteronism

relief of chronic urinary obstruction

relief of chronic urinary obstruction

drugs: lithium carbonate, demeclocycline, amphotericin B, glibenclamide, gentamicin

drugs: lithium carbonate, demeclocycline, amphotericin B, glibenclamide, gentamicin

cranial diabetes insipidus (hypothalamo-pituitary tumour, skull trauma, sarcoidosis or histiocytosis X)

cranial diabetes insipidus (hypothalamo-pituitary tumour, skull trauma, sarcoidosis or histiocytosis X)

Cushing’s disease from excessive corticosteroid doses and ACTH-secreting bronchial carcinoma

Cushing’s disease from excessive corticosteroid doses and ACTH-secreting bronchial carcinoma

sickle-cell anaemia

sickle-cell anaemia

early chronic pyelonephritis

early chronic pyelonephritis

RARE

psychogenic polydipsia (compulsive water drinking)

psychogenic polydipsia (compulsive water drinking)

supraventricular tachycardia

supraventricular tachycardia

DIDMOAD syndrome (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, deafness: autosomal recessive)

DIDMOAD syndrome (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, deafness: autosomal recessive)

familial cranial diabetes insipidus (autosomal dominant inheritance)

familial cranial diabetes insipidus (autosomal dominant inheritance)

familial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (males only: X-linked recessive)

familial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (males only: X-linked recessive)

Fanconi syndrome

Fanconi syndrome

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, fasting glucose or HbA1c.

POSSIBLE: FBC, U&E, serum calcium.

SMALL PRINT: blood film, further specialist investigations (see below).

Urinalysis: glucose and possible ketones in diabetes; possible haematuria and proteinuria with renal problems; specific gravity very low in diabetes insipidus and psychogenic polydipsia.

Urinalysis: glucose and possible ketones in diabetes; possible haematuria and proteinuria with renal problems; specific gravity very low in diabetes insipidus and psychogenic polydipsia.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: to confirm diabetes mellitus.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: to confirm diabetes mellitus.

FBC: normochromic anaemia in CRF; film for sickle-cell anaemia.

FBC: normochromic anaemia in CRF; film for sickle-cell anaemia.

U&E: to detect potassium deficiency and abnormalities suggesting CRF.

U&E: to detect potassium deficiency and abnormalities suggesting CRF.

Serum calcium: elevated in hypercalcaemia.

Serum calcium: elevated in hypercalcaemia.

Further specialist investigations: many of the aforementioned ‘causes’ will need further investigation in secondary care to establish underlying aetiology (e.g. ultrasound and renal biopsy in CRF, water deprivation test for diabetes insipidus, CT scan if possible pituitary lesion, and so on).

Further specialist investigations: many of the aforementioned ‘causes’ will need further investigation in secondary care to establish underlying aetiology (e.g. ultrasound and renal biopsy in CRF, water deprivation test for diabetes insipidus, CT scan if possible pituitary lesion, and so on).

Take time to clarify the symptoms. It is essential to differentiate polyuria from frequency, as the causes are very different.

Take time to clarify the symptoms. It is essential to differentiate polyuria from frequency, as the causes are very different.

Remember alcohol as a possible cause, especially in young males. Patients can be surprisingly slow to make quite obvious connections.

Remember alcohol as a possible cause, especially in young males. Patients can be surprisingly slow to make quite obvious connections.

Refer for more detailed investigation if the symptoms are clear-cut and baseline tests draw a blank.

Refer for more detailed investigation if the symptoms are clear-cut and baseline tests draw a blank.

Diabetes mellitus is not the only cause of polyuria with thirst. If urinalysis is negative for sugar, consider diabetes insipidus or hypercalcaemia.

Diabetes mellitus is not the only cause of polyuria with thirst. If urinalysis is negative for sugar, consider diabetes insipidus or hypercalcaemia.

Weight loss and cough in a smoker with polyuria suggests a possible ACTH-secreting tumour. Arrange an urgent CXR.

Weight loss and cough in a smoker with polyuria suggests a possible ACTH-secreting tumour. Arrange an urgent CXR.

If urinalysis reveals glucose and ketones in a known or new diabetic, arrange for urgent assessment with a view to admission for stabilisation.

If urinalysis reveals glucose and ketones in a known or new diabetic, arrange for urgent assessment with a view to admission for stabilisation.

Renal disease is likely in patients with polydipsia who have blood and protein on urinalysis.

Renal disease is likely in patients with polydipsia who have blood and protein on urinalysis.

![]()

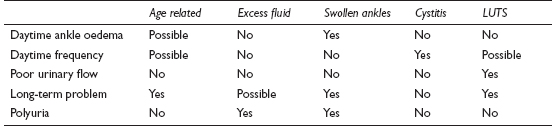

This means an increased frequency of micturition, and is usually associated with the passage of small amounts of urine. It is not the same as increased production of urine (see Excessive urination, p. 413). It is a commonly presented problem, affecting women far more often than men: the average GP will deal with around 60 cases of cystitis (the main cause) each year. Terminology can be confusing – we now use ‘LUTS’ for what we used to describe as ‘prostatism’.

![]()

COMMON

infective cystitis

infective cystitis

anxiety

anxiety

overactive bladder syndrome

overactive bladder syndrome

bladder calculus

bladder calculus

lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men

lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men

OCCASIONAL

interstitial cystitis (non-infective)

interstitial cystitis (non-infective)

prostatitis

prostatitis

pregnancy

pregnancy

ureteric calculus (in lower third of ureter precipitates reflex frequency)

ureteric calculus (in lower third of ureter precipitates reflex frequency)

urethritis, pyelonephritis

urethritis, pyelonephritis

iatrogenic (e.g. diuretics)

iatrogenic (e.g. diuretics)

bladder neck hypertrophy

bladder neck hypertrophy

‘habit frequency’

‘habit frequency’

RARE

pelvic space-occupying lesion, e.g. fibroid, ovarian cyst, carcinoma

pelvic space-occupying lesion, e.g. fibroid, ovarian cyst, carcinoma

secondary to pelvic inflammation: PID, appendicitis, diverticulitis, adjacent tumour

secondary to pelvic inflammation: PID, appendicitis, diverticulitis, adjacent tumour

bladder tumour (benign or malignant)

bladder tumour (benign or malignant)

post-radiotherapy fibrosis (testicular, ovarian and prostatic cancer)

post-radiotherapy fibrosis (testicular, ovarian and prostatic cancer)

tuberculous cystitis/renal TB

tuberculous cystitis/renal TB

fibrosis secondary to chronic sepsis from long-term catheter drainage

fibrosis secondary to chronic sepsis from long-term catheter drainage

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU, urinary frequency volume chart.

POSSIBLE: urethral swab, PSA, uroflowmetry, urodynamic studies, plain abdominal X-ray, IVU, cystoscopy, CA-125.

SMALL PRINT: pelvic ultrasound, U&E, pregnancy test and three EMUs for TB.

Urinalysis: protein, nitrites, leucocytes and possible haematuria in infection; possible stone or tumour if blood alone.

Urinalysis: protein, nitrites, leucocytes and possible haematuria in infection; possible stone or tumour if blood alone.

MSU: microscopy may show abnormal epithelial cells, blood, pus and help identify pathogen in infection.

MSU: microscopy may show abnormal epithelial cells, blood, pus and help identify pathogen in infection.

Urinary frequency volume chart – may be useful in men with LUTS.

Urinary frequency volume chart – may be useful in men with LUTS.

Swab any urethral discharge present for Chlamydia and gonorrhoea.

Swab any urethral discharge present for Chlamydia and gonorrhoea.

CA-125 – may be useful if ovarian cancer suspected.

CA-125 – may be useful if ovarian cancer suspected.

EMU: for pregnancy test; also three EMUs to check for TB if suspected (e.g. sterile pyuria).

EMU: for pregnancy test; also three EMUs to check for TB if suspected (e.g. sterile pyuria).

U&E: check if assessment suggests chronic sepsis or outflow obstruction.

U&E: check if assessment suggests chronic sepsis or outflow obstruction.

PSA: consider this if LUTS in male.

PSA: consider this if LUTS in male.

Specialist tests include: uroflowmetry (for LUTS, urodynamic studies (for unstable bladder), IVU and cystoscopy (for stones and tumours) and ultrasound (for pelvic masses or if CA-125 elevated).

Specialist tests include: uroflowmetry (for LUTS, urodynamic studies (for unstable bladder), IVU and cystoscopy (for stones and tumours) and ultrasound (for pelvic masses or if CA-125 elevated).

Frequency due to anxiety is typically long term, worse with stress and cold weather, and is associated with a normal urinalysis.

Frequency due to anxiety is typically long term, worse with stress and cold weather, and is associated with a normal urinalysis.

It is reasonable to make an empirical diagnosis of overactive bladder syndrome in a non-pregnant female with frequency in whom CA-125, pelvic examination and urinalysis are entirely normal.

It is reasonable to make an empirical diagnosis of overactive bladder syndrome in a non-pregnant female with frequency in whom CA-125, pelvic examination and urinalysis are entirely normal.

An unrecognised pregnancy may present with frequency: ask about periods, and do a pregnancy test if a period has been missed.

An unrecognised pregnancy may present with frequency: ask about periods, and do a pregnancy test if a period has been missed.

In the elderly, a bladder tumour may present as cystitis. If a new, recurring problem, or haematuria attributed to the cystitis does not settle with antibiotics, consider referral.

In the elderly, a bladder tumour may present as cystitis. If a new, recurring problem, or haematuria attributed to the cystitis does not settle with antibiotics, consider referral.

Do not ignore sterile pyuria on the MSU: possible causes include urethritis and TB.

Do not ignore sterile pyuria on the MSU: possible causes include urethritis and TB.

The adult patient with frequency who has persistent microscopic haematuria but no other abnormalities on urinalysis may have a stone or tumour. Refer.

The adult patient with frequency who has persistent microscopic haematuria but no other abnormalities on urinalysis may have a stone or tumour. Refer.

Appendicitis can cause mild frequency and pyuria. Do not be misled by the urinalysis into an inappropriate diagnosis of UTI: act according to the clinical findings.

Appendicitis can cause mild frequency and pyuria. Do not be misled by the urinalysis into an inappropriate diagnosis of UTI: act according to the clinical findings.

UTI in infancy is a major cause of renal failure. Manage according to NICE guidance.

UTI in infancy is a major cause of renal failure. Manage according to NICE guidance.

![]()

Incontinence is involuntary micturition. It is not a common presenting symptom, embarrassment tending to inhibit patients, but it is often mentioned as a ‘while I’m here’ or noted by the doctor, typically because of the characteristic odour when visiting an elderly patient. It may present more frequently in the future as the problem receives more publicity and patients realise that help is available. The population prevalence in women is around 10%, but is probably much higher in older age groups.

![]()

COMMON

stress incontinence (with or without prolapse)

stress incontinence (with or without prolapse)

infective cystitis

infective cystitis

overactive bladder syndrome: idiopathic or secondary to other problems, e.g. CVA, dementia, Parkinson’s disease

overactive bladder syndrome: idiopathic or secondary to other problems, e.g. CVA, dementia, Parkinson’s disease

chronic outflow obstruction, e.g. prostatic enlargement, bladder neck stenosis, urethral stenosis

chronic outflow obstruction, e.g. prostatic enlargement, bladder neck stenosis, urethral stenosis

after prostatectomy (usually temporary)

after prostatectomy (usually temporary)

OCCASIONAL

chronic UTI

chronic UTI

interstitial cystitis

interstitial cystitis

bladder stone or tumour

bladder stone or tumour

after abdomino-pelvic surgery and radiotherapy

after abdomino-pelvic surgery and radiotherapy

fistula: vesicovaginal/uterine, ureterovaginal (surgery and malignancy)

fistula: vesicovaginal/uterine, ureterovaginal (surgery and malignancy)

polyuria (any cause, e.g. diabetes, diuretics – particularly if compounded by immobility in the elderly)

polyuria (any cause, e.g. diabetes, diuretics – particularly if compounded by immobility in the elderly)

RARE

after pelvic fracture (direct sphincter damage with or without neurological damage)

after pelvic fracture (direct sphincter damage with or without neurological damage)

congenital abnormalities: short urethra, wide urethra, epispadias, ectopic ureter

congenital abnormalities: short urethra, wide urethra, epispadias, ectopic ureter

sensory neuropathy, e.g. diabetes and syphilis

sensory neuropathy, e.g. diabetes and syphilis

multiple sclerosis, syringomyelia

multiple sclerosis, syringomyelia

paraplegia, cauda equina lesion

paraplegia, cauda equina lesion

psychogenic

psychogenic

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU.

POSSIBLE: PSA, U&E, ultrasound, IVU, urodynamic studies, uroflowmetry.

SMALL PRINT: fasting sugar or HbA1c blood sugar, syphilis serology, cystoscopy, neurological investigations.

Urinalysis: to test for infection and diabetes.

Urinalysis: to test for infection and diabetes.

MSU: to confirm infection and guide antibiotic treatment.

MSU: to confirm infection and guide antibiotic treatment.

Fasting sugar or HbA1c and syphilis serology: if diabetes or syphilis a possible cause of neuropathy.

Fasting sugar or HbA1c and syphilis serology: if diabetes or syphilis a possible cause of neuropathy.

PSA: consider this if LUTS or prostatic enlargement on examination.

PSA: consider this if LUTS or prostatic enlargement on examination.

U&E: to assess renal function in chronic outflow obstruction.

U&E: to assess renal function in chronic outflow obstruction.

Ultrasound good for assessing renal size non-invasively: may suggest outflow obstruction or chronic infection.

Ultrasound good for assessing renal size non-invasively: may suggest outflow obstruction or chronic infection.

IVU best for looking for renal scarring of chronic UTI, structural anomalies and demonstrating residual urine; may also reveal site of outflow obstruction and fistulae.

IVU best for looking for renal scarring of chronic UTI, structural anomalies and demonstrating residual urine; may also reveal site of outflow obstruction and fistulae.

Specialist investigations may include: urodynamic studies (helpful to distinguish between urge and stress incontinence), uroflowmetry (prostatism), cystoscopy (may reveal cause of outflow obstruction, stone or tumour) and neurological investigations (e.g. imaging of spinal cord).

Specialist investigations may include: urodynamic studies (helpful to distinguish between urge and stress incontinence), uroflowmetry (prostatism), cystoscopy (may reveal cause of outflow obstruction, stone or tumour) and neurological investigations (e.g. imaging of spinal cord).

Incontinence has many causes, but can often be broadly categorised into one of three groups: stress incontinence (e.g. with coughing), urge incontinence (‘when I’ve got to go, I’ve got to go’) and continuous, like water over the edge of a dam (e.g. through a vesicovaginal fistula, or in overflow from a chronically distended bladder).

Incontinence has many causes, but can often be broadly categorised into one of three groups: stress incontinence (e.g. with coughing), urge incontinence (‘when I’ve got to go, I’ve got to go’) and continuous, like water over the edge of a dam (e.g. through a vesicovaginal fistula, or in overflow from a chronically distended bladder).

The aetiology may be multifactorial, particularly in the elderly. Mobility, vision, distance to the toilet and ongoing medication may all be relevant.

The aetiology may be multifactorial, particularly in the elderly. Mobility, vision, distance to the toilet and ongoing medication may all be relevant.

Overactive bladder syndrome and stress incontinence can be difficult to distinguish. The latter rarely causes nocturnal incontinence, while it may be a feature of overactive bladder syndrome. If in doubt, refer for urodynamic studies.

Overactive bladder syndrome and stress incontinence can be difficult to distinguish. The latter rarely causes nocturnal incontinence, while it may be a feature of overactive bladder syndrome. If in doubt, refer for urodynamic studies.

Adopt a sympathetic approach. Incontinence can have a devastating impact on self-esteem and seriously affect a patient’s social and sexual functioning.

Adopt a sympathetic approach. Incontinence can have a devastating impact on self-esteem and seriously affect a patient’s social and sexual functioning.

Incontinence with saddle anaesthesia and leg weakness suggests a cauda equina lesion. This is a neurological emergency: refer urgently.

Incontinence with saddle anaesthesia and leg weakness suggests a cauda equina lesion. This is a neurological emergency: refer urgently.

Continuous incontinence suggests significant pathology, such as a fistula, chronic outflow obstruction or a neurological problem.

Continuous incontinence suggests significant pathology, such as a fistula, chronic outflow obstruction or a neurological problem.

Never empty the huge bladder of chronic retention in one go. This can cause bleeding and renal complications. Admit for catheterisation and controlled release.

Never empty the huge bladder of chronic retention in one go. This can cause bleeding and renal complications. Admit for catheterisation and controlled release.

Adult-onset nocturnal enuresis suggests chronic retention.

Adult-onset nocturnal enuresis suggests chronic retention.

![]()

Nocturia may present in isolation or it may be a manifestation of other urinary disturbances such as polyuria or frequency. Surprisingly, in older age groups, it is as common in women as men. Occasional nocturia is, of course, quite normal – the symptom should only be viewed as pathological when it causes disruption or distress.

![]()

COMMON

age related (in part caused by a reduction in bladder capacity)

age related (in part caused by a reduction in bladder capacity)

excess fluid at bed time (especially alcohol)

excess fluid at bed time (especially alcohol)

any cause of swollen ankles (the recumbent posture redistributes the fluid load at night) – see Swollen ankles, p. 312

any cause of swollen ankles (the recumbent posture redistributes the fluid load at night) – see Swollen ankles, p. 312

cystitis

cystitis

LUTS

LUTS

OCCASIONAL

overactive bladder syndrome

overactive bladder syndrome

lower urinary tract obstruction (other than prostate problems)

lower urinary tract obstruction (other than prostate problems)

any other cause of urinary frequency (see Frequency, p. 416)

any other cause of urinary frequency (see Frequency, p. 416)

diabetes mellitus

diabetes mellitus

any other cause of polyuria (see Excessive urination, p. 413)

any other cause of polyuria (see Excessive urination, p. 413)

sleep apnoea (causes overproduction of urine)

sleep apnoea (causes overproduction of urine)

RARE

anxiety

anxiety

drug side effect (rare because drugs likely to cause a diuresis are usually taken in the morning)

drug side effect (rare because drugs likely to cause a diuresis are usually taken in the morning)

diabetes insipidus

diabetes insipidus

![]()

![]()

NOTE: urinary frequency, polyuria, or swollen ankles as ‘causes’ of nocturia will need investigating in their own right – see the relevant sections for more details on each of these topics.

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU, urinary frequency volume chart.

POSSIBLE: blood sugar, PSA.

SMALL PRINT: cystoscopy, urodynamic studies, IVP/ultrasound, water deprivation test.

Urinalysis: protein, nitrites, leucocytes and possible haematuria in infection; glucose in diabetes; specific gravity very low in diabetes insipidus.

Urinalysis: protein, nitrites, leucocytes and possible haematuria in infection; glucose in diabetes; specific gravity very low in diabetes insipidus.

MSU: to confirm infection and identify pathogen.

MSU: to confirm infection and identify pathogen.

Urinary frequency volume chart – to help distinguish nocturnal polyuria (increased urine production at night) from reduced bladder storage capacity.

Urinary frequency volume chart – to help distinguish nocturnal polyuria (increased urine production at night) from reduced bladder storage capacity.

Blood sugar: to confirm diabetes mellitus.

Blood sugar: to confirm diabetes mellitus.

PSA: pros and cons of this test may be discussed if assessment raises the possibility of prostate cancer.

PSA: pros and cons of this test may be discussed if assessment raises the possibility of prostate cancer.

Specialist tests include: cystoscopy and IVU/ultrasound (for lower urinary tract obstruction), urodynamic studies (for unstable bladder) and water deprivation test (for diabetes insipidus).

Specialist tests include: cystoscopy and IVU/ultrasound (for lower urinary tract obstruction), urodynamic studies (for unstable bladder) and water deprivation test (for diabetes insipidus).

In the elderly, the cause is often multifactorial.

In the elderly, the cause is often multifactorial.

The effects – such as disturbed sleep, a disrupted household, exhaustion and occasional incontinence – may be more important to the patient than the specific diagnosis.

The effects – such as disturbed sleep, a disrupted household, exhaustion and occasional incontinence – may be more important to the patient than the specific diagnosis.

Swollen ankles – of any aetiology – are frequently overlooked as an underlying cause.

Swollen ankles – of any aetiology – are frequently overlooked as an underlying cause.

Nocturia may just be a manifestation (albeit the most distressing) of polyuria or urinary frequency. Focus your approach on the underlying problem.

Nocturia may just be a manifestation (albeit the most distressing) of polyuria or urinary frequency. Focus your approach on the underlying problem.

Exclude diabetes – but remember that it is not the only cause of polyuria, nocturia and thirst.

Exclude diabetes – but remember that it is not the only cause of polyuria, nocturia and thirst.

A habitual ‘nightcap’ may be the cause of nocturia – and may be a pointer to an underlying alcohol problem, especially in solitary elderly males.

A habitual ‘nightcap’ may be the cause of nocturia – and may be a pointer to an underlying alcohol problem, especially in solitary elderly males.

![]()

Retention is failure to empty the bladder completely. The acute form characteristically affects men, presents urgently and requires immediate catheterisation or hospitalisation. Chronic retention may produce few symptoms and may only be discovered during palpation of the abdomen.

![]()

COMMON

prostatic hypertrophy: benign, rarely carcinoma

prostatic hypertrophy: benign, rarely carcinoma

anticholinergic drugs: bladder stabilisers and tricyclic antidepressants

anticholinergic drugs: bladder stabilisers and tricyclic antidepressants

constipation

constipation

bladder neck obstruction/urethral stricture

bladder neck obstruction/urethral stricture

UTI (including prostatitis and prostatic abscess)

UTI (including prostatitis and prostatic abscess)

OCCASIONAL

urethral calculus

urethral calculus

‘holding on’ (leads to prostatic congestion)

‘holding on’ (leads to prostatic congestion)

pelvic mass: retroverted, gravid uterus or fibroid uterus

pelvic mass: retroverted, gravid uterus or fibroid uterus

acute genital herpes (via local inflammation and interference with neurological control of detrusor reflex arc)

acute genital herpes (via local inflammation and interference with neurological control of detrusor reflex arc)

clot retention (e.g. after bleed from tumour or post-TURP bleed)

clot retention (e.g. after bleed from tumour or post-TURP bleed)

balanoposthitis in children (if very painful)

balanoposthitis in children (if very painful)

RARE

neurological: MS, syphilis, spinal cord compression

neurological: MS, syphilis, spinal cord compression

pedunculated bladder tumour

pedunculated bladder tumour

traumatic rupture of urethra

traumatic rupture of urethra

foreign body inserted into anterior urethra

foreign body inserted into anterior urethra

phimosis

phimosis

psychological

psychological

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU.

POSSIBLE: U&E, PSA, ultrasound, IVU, cystoscopy.

SMALL PRINT: neurological investigations, prostatic biopsy, urethrography (all hospital-based investigations).

Urinalysis of any urine available may confirm a UTI as the cause; may also reveal microscopic haematuria if a stone or bladder tumour.

Urinalysis of any urine available may confirm a UTI as the cause; may also reveal microscopic haematuria if a stone or bladder tumour.

MSU: will confirm infective agent in UTI.

MSU: will confirm infective agent in UTI.

U&E: renal failure may follow chronic retention.

U&E: renal failure may follow chronic retention.

PSA may be worth considering if preceding symptoms of prostatism or abnormal prostate on examination.

PSA may be worth considering if preceding symptoms of prostatism or abnormal prostate on examination.

Specialist tests may include: renal ultrasound (reveals obstruction and pelvic masses), IVU (may reveal site of obstruction and will provide information about renal function), cystoscopy (may be diagnostic and therapeutic for stones, stricture, bladder outflow obstruction and bladder tumour), neurological investigations (e.g. spinal cord imaging if cord lesion suspected), prostatic biopsy (if suspicious area of prostate palpable) and urethrography (for stricture).

Specialist tests may include: renal ultrasound (reveals obstruction and pelvic masses), IVU (may reveal site of obstruction and will provide information about renal function), cystoscopy (may be diagnostic and therapeutic for stones, stricture, bladder outflow obstruction and bladder tumour), neurological investigations (e.g. spinal cord imaging if cord lesion suspected), prostatic biopsy (if suspicious area of prostate palpable) and urethrography (for stricture).

Do not overlook faecal impaction in the elderly patient as a cause of urinary retention.

Do not overlook faecal impaction in the elderly patient as a cause of urinary retention.

‘First-aid’ relief of retention when the cause is a painful perineal condition (e.g. balanoposthitis, herpes simplex or UTI) may be achieved by encouraging the patient to urinate while immersed in a warm bath.

‘First-aid’ relief of retention when the cause is a painful perineal condition (e.g. balanoposthitis, herpes simplex or UTI) may be achieved by encouraging the patient to urinate while immersed in a warm bath.

Anuria can be mistaken for retention. A straightforward clinical assessment should differentiate the two conditions.

Anuria can be mistaken for retention. A straightforward clinical assessment should differentiate the two conditions.

A history suggesting a disc prolapse with urinary retention indicates possible cord compression – admit immediately.

A history suggesting a disc prolapse with urinary retention indicates possible cord compression – admit immediately.

Sudden stoppage of urine with a pain like a blow to the bladder and passage of a few drops of blood is pathognomic of urethral calculus.

Sudden stoppage of urine with a pain like a blow to the bladder and passage of a few drops of blood is pathognomic of urethral calculus.

Beware of any drugs with anticholinergic side effects in patients with a history of outflow obstruction – they may precipitate acute retention.

Beware of any drugs with anticholinergic side effects in patients with a history of outflow obstruction – they may precipitate acute retention.

Avoid catheterisation when sepsis is likely (e.g. possible UTI) – instrumentation may result in septicaemia. Instead, admit to hospital for catheterisation under appropriate antibiotic cover.

Avoid catheterisation when sepsis is likely (e.g. possible UTI) – instrumentation may result in septicaemia. Instead, admit to hospital for catheterisation under appropriate antibiotic cover.

Do not catheterise the patient with chronic retention; admit for controlled drainage. Sudden decompression can result in haematuria and renal complications.

Do not catheterise the patient with chronic retention; admit for controlled drainage. Sudden decompression can result in haematuria and renal complications.