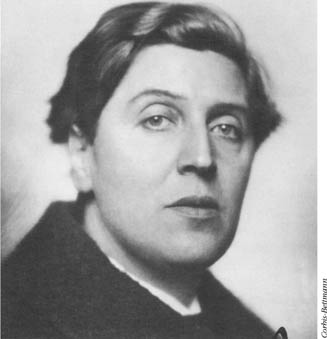

Alban Berg has emerged from minority status to be viewed

as one of the most important composers of the century.

Austrian composer Alban Berg, his teacher Arnold SCHOENBERG, and fellow pupil Anton WEBERN were responsible for the development of atonal and later 12-tone music in the early decades of the 20th century. The three are collectively known as the Second Viennese School, and are frequently labelled Expressionist. Berg, however, was much more willing to compromise with tradition; he looked back nostalgically to the tonal past.

Berg was born on February 9, 1885, into a highly cultured Viennese family. At the turn of the century, the Austrian capital was undergoing a period of intense ferment, its complacency and conservatism challenged in almost every category. The psychoanalytical theories of Freud, the angst-ridden portraits of Egon Schiele, and the sexually daring dramas of Arthur Schnitzler and Frank Wedekind provided a stimulating if unsettling environment for a young musician like Berg.

In 1904, Berg responded to an advertisement placed by Schoenberg, who was looking for pupils. Even though Berg had written only a few amateurish songs, Schoenberg was impressed enough to take him on, even waiving his first year’s tuition fees. Schoenberg’s faith in his new pupil paid off. Not only was Berg able to follow his teacher’s revolutionary experiments in atonality but was soon able to initiate his own.

The String Quartet (1910) showed Berg to be an innovative figure in his own right. It was, however, the brief Altenberg Songs (1913) that marked the full assertion of his distinctive and lyrical version of atonality. Schoenberg did not react favourably: the songs were the first works Berg had written without Schoenberg’s supervision, and Schoenberg may well have felt that Berg was staking a premature claim to artistic freedom. The older man gave an unsympathetic reading of two of the songs in a concert he conducted in 1913, and thereby played into the hands of a hostile audience whose disruptions brought the concert to a halt.

Although Berg remained fiercely loyal to his former teacher, he remained true to his own creative voice. The subsequent prewar works—the Four Pieces for Clarinet and Piano (1913) and Three Orchestral Pieces (1914)—reveal him struggling to impose traditional classical forms on atonal content. The latter work, in particular, reveals the extent of Berg’s debt to Mahler. It shows him combining the last stages of tonality with the 12-tone method.

Berg’s first great work was the opera Wozzeck. In May 1914, Berg attended the Vienna premiere of Georg Büchner’s bleak, expressionistic drama Woyzeck (Berg used a spelling based on a poorly transcribed manuscript), which for over 70 years had remained unperformed. The play’s searing indictment of military brutality, its revolutionary statement of society’s role in determining the individual’s actions, and, above all, its raw anarchic energy seemed perfectly in tune with a time of mounting cultural, political, and social turbulence. The plot, which Berg followed closely, is stark: a humble, poverty-stricken soldier submits to an army doctor’s callous medical experiments in order to feed his family, brutally kills his lover, Marie, when he discovers her infidelity, and finally drowns himself.

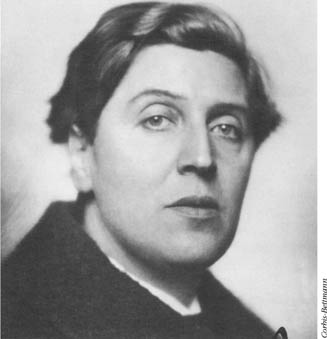

Alban Berg has emerged from minority status to be viewed

as one of the most important composers of the century.

Berg’s determination to turn the play into an opera was thwarted by the outbreak of World War I, when he endured three years of harsh military service. It was not until 1917 that Berg was finally able to begin work on Wozzeck, but now with an energy fired by his own feelings of bitterness and alienation due to the war.

Berg’s largely dissonant score captures the nightmarish intensity of the play, but the music also provides moments of lyricism, such as Marie’s lullaby. Berg’s tendency to combine the old with the new is here particularly clear, juxtaposing tonal and atonal, café music with strident dissonance, speech with song. The extraordinary richness of Wozzeck–s sound-world, however, conceals a rigorous structure, based on traditional musical forms, such as the rondo and the fugue, while the use of leitmotifs (a recurring musical theme in an opera that symbolises a character, place, or object) provides more overt cohesion.

With the financial assistance of Mahler’s widow, Alma, Wozzeck had its first performance in 1925, at the Berlin Staatsoper. It was a popular and critical success, bringing Berg international recognition. The opera was banned, however, by the Nazis in Germany, in 1933, as part of their clampdown on “degenerate music.”

Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern spent the 1920s moving away from Expressionist atonality toward the highly structured 12-tone “serialism.” While Berg’s work in this style was no less systematic than that of Schoenberg and Webern, his methods and his results were once again rather different. His first important work in this innovative mode was the virtuoso Lyric Suite (1925), which was given a successful performance by the renowned Kolisch Quartet. But the masterpieces of this final period are the opera Lulu and the Violin Concerto.

For Lulu, Berg once again turned to a controversial work of German literature—in this case Wedekind’s two “Lulu” plays (Der Erdgeist, 1895, and Der Büchse der Pandora, 1904). The plays’ sexually frank subject-matter—the rise and fall of a femme fatale and her final brutal murder at the hands of Jack the Ripper—raised the lid on the corruption and hypocrisy of turn-of-the-century European society. It was considered so shocking that Wedekind’s work was banned in Germany from 1905 to 1918. The plays had haunted Berg since he had first seen them in a private production in 1905.

The labyrinthine plot meant that, even more than in Wozzeck, Berg paid meticulous attention to the opera’s formal design, reintroducing the patchwork of small musical forms, or “numbers”—duets, interludes, canzonettas, and so on—used in classical opera. Berg completed the short score in 1934, but he abandoned work on the full (orchestrated) score in April 1935, when the death of Alma Mahler’s 18-year-old daughter moved him to write a violin concerto in her memory. The Violin Concerto, which Berg completed rapidly, reveals more clearly than any other work the way in which Berg straddles both traditional and avant-garde compositional techniques, using serial composition to write in a quasi-tonal manner.

Berg’s requiem for Alma Mahler’s daughter also proved to be his own. In August 1935, he fell victim to a painful infection in his back and died four months later, on Christmas Eve. Berg’s widow refused to release material from the unfinished orchestration for Lulu’s third act, and the first full performance could only be given after her death, in a version conducted by Pierre BOULEZ at the Paris Opéra in February 1979. The piece gained its rightful place as one of the masterpieces of 20th-century opera.

Berg’s strong ties with the past led him to find a way in which past and present could fuse, and tonality and serialism could coexist. More than 60 years since his death, Berg’s contribution is only now being appreciated, and his compromising stance may emerge as the most important influence on music of the 21st century.

Richard Trombley

SEE ALSO:

CHAMBER MUSIC; EXPRESSIONISM IN MUSIC; OPERA; SERIALISM.

Carrier, Mosco. Alban Berg: The Man and the Work

(New York: Holmes & Meier, 1977);

Headlam, Dave. The Music of Alban Berg

(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996);

Perle, George. The Operas of Alban Berg

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1980–84).

Altenberg Songs; Lulu; Lyric Suite;

Violin Concerto; Wozzeck.