CHAPTER 1

BUILDING A VERBAL-VISUAL ARCHITECTURE

The RCAF’s New World Mestizo/a Art

Again, there was no nada—no cultura that we could identify with. Nothing to identify with and no teachers, and no interest by other professors. So it was kind of like being in the middle of the desert again. There was nothing there. Chicano art didn’t exist.

Esteban Villa,

interview, January 7, 2004

In 1975, Luis González created Hasta La Victoria Siempre, c/s (Until Victory, Always), a silkscreen poster based on a photograph of José Montoya, his Royal Chicano Air Force colleague and an art professor at California State University, Sacramento (CSUS).1 The photograph was taken by Luis’s brother, Hector, who recalled that when he “worked with José in his Barrio Art Program . . . he would always ask me to document the farmworkers movement” (Hector González, e-mail to author, September 7, 2011). On the day the photograph was taken, Hector González and José Montoya were in Yuba City, California, assisting a strike for the United Farm Workers (UFW) union. Taking several shots of Montoya and the workers who walked out of the fields, Hector González captured Montoya in a militant pose, one hand holding a large UFW flag and the other holding a bullhorn. Luis González transferred the photograph onto a poster and constructed a background made up of two phrases, “viva la huelga” and “viva la manana” (mañana). The phrases, which mean “long live the strike” and “long live tomorrow,” run into each other, building the environment in which Montoya stands. In contrast with the background, Luis González rendered Montoya in a red block of color that monumentalizes him, but also abstracts him into a heroic idea—or a call for sustained political action based on the historical resolve of the farmworker movement.

In relation to Montoya’s epic stature in the poster, the huelga eagle on the flag he holds is constructed out of the slogans that create the background. Such sayings were part of the verbal-visual architecture of the Chicano movement because, like the poster, they transformed the space in which Chicanos/as lived, worked, and moved into a shared political vision for the future. Hung on barrio walls, adhered to windows and doors of buildings, RCAF art announced the farmworkers’ strike as it was demanded, as it was performed into being, and as it gave voice to long-felt injustices (Pérez-Torres 2006, 115).

But while the farmworkers’ strike shapes the landscape of González’s poster, it also aligns with an international call for third world liberation. The poster’s title, Hasta La Victoria Siempre, c/s, echoes the song “Hasta Siempre, Comandante” (1965), written by Cuban songwriter Carlos Puebla in response to Che Guevara’s parting words to Cuba when he left the country to participate in revolutionary efforts in Congo and Bolivia (Chomsky 2010, 121). Built into the verbal-visual architecture of González’s poster is an awareness of the Chicano/a farmworking experience as a global one. The slogan “viva la huelga” (long live the strike) narrativizes Chicano/a consciousness-raising; it visually and verbally communicates the story of the farmworkers’ strike as the spreading of international ideas in the physical and mental landscape of the Chicano movement. Fusing with the poster’s call to live for tomorrow, the slogan creates a utopic space of ideas for Chicanos/as, one that led to critical theories on race and ethnicity in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

But how did Luis González arrive in the space of a poster in which he constructed a verbal and visual fusion of UFW slogans, international politics, and future possibilities? In this chapter, I approach this question by exploring the RCAF’s construction of a Chicano/a verbal-visual architecture through the signs, symbols, and words they absorbed, articulated, and reproduced over time. Chicano/a expressions of power and solidarity in the 1960s and 1970s were conveyed through the concept of Aztlán, or a homeland within the nation. “Chicano/a artists,” Guisela Latorre (2008) writes, “took to the streets not to search for Aztlán, but instead to re-create it with the aid of the public mural” (146; emphasis in original). Along with murals, Chicano/a artists visualized Aztlán in posters as a decolonial idea based on the location of an ancient, native land with which Chicanos/as could ancestrally identify and claim their rights to US citizenship. Aztlán was also a new idea for Chicanos/as because it proposed a different way of being Mexican American in the United States—as a united sociopolitical body.

RCAF members were on the front lines of producing Aztlán in Sacramento in the late 1960s and 1970s because their art literally remapped the built environment for Chicanos/as. But they also transformed the abstract spaces of US history through the ideas imbued in their work. RCAF art charted Chicano/a history and culture along a south-to-north trajectory, confronting and converging with an east-to-west ordering of the world that was (and is) central to the dominant cultural narrative of the nation. In doing so, RCAF artists redressed representations of Mexican America that had been defined for them—from nineteenth-century literature and press, to characterizations in twentieth-century media and popular culture.2 Generating a vocabulary to talk about Chicanismo—Chicano/a identity, language, history, and culture—in decolonial terms, the RCAF produced what Patssi Valdez calls an “image vocabulary,” a term she used following her decade of artistic collaboration with Asco, a foundational Chicano/a art collective in Los Angeles in the 1970s (Romo 1999, 25).

I move in and out of a linear sequence of history to track the origins of the RCAF’s “image vocabulary” because their art builds on multiple political, cultural, and artistic encounters, irrespective of historical periodization. This means that as I analyze RCAF art, I refer to larger contexts as well as personal reflections of the art makers before and during the Chicano movement. The 1960s and 1970s witnessed a “rejuvenated jolt of ethnic and racial consciousness,” writes Rafael Pérez-Torres (2006, 116), which spread across the nation and engaged international political movements. It provided a language that the RCAF honed once their lives coincided in Sacramento. But prior to the RCAF’s founding, members experienced other worlds through military service during the Vietnam War and the Korean War. These encounters extended their political consciousness, connecting the farmworkers’ strike to earlier calls for sociopolitical change. College enrollment in different cities and at different times also shaped their exposure to racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity in the United States, which in turn influenced their artwork. The RCAF encountered transnational ideas that never stopped—before or after conquest and colonization, and particularly with regard to the arts.

Founding members of the RCAF who were a generation older than many Chicano/a activists in the 1960s and 1970s underwent a politicization process before 1965, the date proposed as the beginning of Chicano/a art by Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (CARA), a retrospective exhibition in the 1990s that framed Chicano/a art as taking place between 1965 and 1985. While they were not the only older members in the RCAF, Esteban Villa and José Montoya entered California State University, Sacramento, under different circumstances than the majority of members. Montoya enrolled as a graduate student in the Mexican American Education Project (MAEP) at CSUS, and Villa became the program’s art consultant. Shortly thereafter, they became university professors. While they were impacted by university policies that transformed student demographics in the 1960s and 1970s, they were affected differently by institutional measures aimed at inclusion. This is an important detail in the RCAF’s formation because the collective comprised men and women who had varied encounters with war, labor unionization, and civil rights activism that coalesced into a uniquely structured Chicano/a art collective.

The RCAF’s verbal-visual architecture was part of a larger poetics of protest and imagery infused with liberationist thought and politics. Accordingly, I explore overlapping articulations of empowerment that erected verbal-visual architectures for all underrepresented Americans. For example, many Chicano/a artists were politically aligned with the work of Native American and African American artists; but these alliances are not well known beyond the artists who forged them. Part of the work of this chapter is to broach connections between international and US artists of color that occurred throughout the twentieth century and in critical mass during the 1960s and 1970s.

I use the idea of a “truly New World mestizo/a art” (Gaspar de Alba 1998, 41) as the foundation for the verbal-visual architecture that the RCAF created during the 1960s and 1970s and in dialogue with mainstream culture and dominant art world traditions. Alicia Gaspar de Alba uses the phrase to talk about Chicano/a art as an ongoing syncretic process in addition to being a historical period of art as it was presented in the CARA exhibition. Aware of its political edge and potential for controversy, Gaspar de Alba’s notion of a New World mestizo/a art appropriates the experience of conquest and racial mixture from dominant cultural narratives in the United States and Mexico to speak back to power. This was precisely what Chicano/a artists were doing in the 1960s and 1970s when they reconfigured the mixtures the term implies.

Chicano/a art draws on “New World” mestizaje, a concept of racial miscegenation in Mexico, but one that begins before Spanish conquest and also because of it, through indigenous, European, and African cultural mixtures. Chicano/a artists claimed precolonial indigeneity alongside the colonial origins of Afro-Chicanidad in their art as part of their liberation from historical and contemporary oppressions. Through the study of pre-Columbian texts and imagery, colonial art histories, and, most importantly, through conversation, many Chicano/a artists learned just “how ‘black’ the New World really was” prior to twenty-first century scholarly “discoveries” of being Black in Latin America (Gates 2011, 1–4). Exposure to the art of the 1910 Mexican Revolution as well as to US government–sponsored art of the 1930s and 1940s was also an important building block for New World mestizo/a art that RCAF members and other artists of color used to express common struggles in their contemporary moment.

Like Aztlán, a “New World mestizo/a art” is old and new because it allows for intergenerational influences between artists of different eras, nationalities, and races. It reveals a much older transnational art history that accounts for important encounters between Mexican, African American, indigenous, and Chicano/a artists before, during, and after the twentieth century. While economic changes and wars, as well as foreign and domestic policies, created opportunities for transnational artistic exposures, such opportunities occurred on the ground—in colleges and art schools, amidst the painting and witnessing of murals, through the production of underground newspapers and posters, in the assembly and publication of vanguard anthologies, and within student-led, collective forums for discussions on art and identity.

Wetbacks and Dominos: A Split Existence in the Absence of Chicano/a Art

When Esteban Villa arrived at the California College of the Arts in Oakland, California, in 1955, his exposure to leading trends in American art broadened his worldview.3 But the institutional atmosphere in which the trends were shaped created new frustrations for him. Eva Cockcroft, John Pitman Weber, and James Cockcroft (1998, 19) claim that before the 1960s and 1970s explosion of community murals in the United States, “much of the avant-garde felt a need to expand the ever-shrinking audience for visual art and to regain a sense of relevant interaction with society.” Yet a central taboo remained regarding “the insertion of social content into an artwork” (21). Certainly, the historical avant-garde movements, including the Dadaists and Surrealists, were interested in changing social reality; but this dimension of avant-garde practice was discouraged or avoided in art schools in the 1950s (20). A division between political activism and artistic trends created what Cockcroft, Weber, and Cockcroft deem a “split existence” for artists who attempted a critical distance from politics in their artwork but were politically active in their lives (21).

To some extent, Chicano/a art was part of a broader rediscovery of the older avant-garde movements, both in terms of their social dimension and their fusion of mediums. Ironically, the term “avant-garde” directly applied to Asco and their street performances in the 1970s, which merged elements of theater, visual art, and political protest. Asco’s guerilla-style art responded to the fact that “Chicanos accounted for less than 1 percent of the University of California’s total student population [and] suffered the highest death rate of all US military personnel” in the Vietnam War (Chavoya 2000, 241). Asco’s street performances also occurred in the aftermath of violent clashes between Los Angeles police and the Chicano Moratorium activists who organized a series of protests in response to the disproportionate death toll of Chicano GIs (241). Asco remained absent from US art history until the early twenty-first century because of enduring institutional beliefs that avant-garde art is meant to change the art world and not social reality (264).

Amid the Vietnam War, urban crises, and social alienation, American artists of color were called to the front lines of image production in the 1960s and 1970s; but, as Marcos Sanchez-Tranquilino (1993, 92–93) writes, US museums, galleries, and universities maintained an assumption that “Mexicans (like other ethnic minorities in the United States) could not produce fine art or a fine art culture.” This assumption eclipsed the economic reality that access to art school and professional training had everything to do with class background and nothing to do with talent or ability (91–92). In the 1970s, for example, Asco was informed by a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that “Chicanos made graffiti not art, hence their absence from the gallery walls” (Noriega 2010). In other words, Chon Noriega remarks, “‘Chicano art’ was a categorical impossibility.”

Nearly two decades before Asco’s street performances, Esteban Villa entered the California College of the Arts (CCA) as a “categorical impossibility.” Villa was among a cohort of Chicano students from working-class backgrounds with military service in the Korean War. Having served from 1949 to 1953 in the US Army’s transportation department, he used the GI Bill to attend CCA. He arrived at art school a year after the implementation of “Operation Wetback,” a derogatory slur for Mexicans and Mexican Americans used as the name of an immigration policy that deported large numbers of Mexicans and Mexican Americans more for ideological and politicized reasons than for economic ones. (Urquijo-Ruiz 2004, 64).

A year prior to Villa’s enrollment at CCA, the United States became increasingly involved in the escalating Indochina Wars. President Eisenhower used “domino theory” to characterize the Vietnamese independence movement as “a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly” (Willbanks 2013, 49).4 It was in the midst of these two terms for domestic and foreign people of color—wetbacks and dominos—that Villa, a Korean War veteran, began to study vanguard styles such as Abstraction, Minimalism, Pop, and Conceptual art, while also becoming estranged from the CCA’s avant-garde ideology and practices (Cockcroft, Weber, and Cockcroft 1998, 20).

A child of farmworkers, Villa spent his adolescence working in the agricultural fields of California’s San Joaquin valley. His sense of alienation at CCA felt eerily similar to what he experienced growing up in Bakersfield, California, where he recalls feeling “hungry for art.” Comparing his hometown to “a desert,” Villa elaborated that “it’s a metaphor for the lack of art and culture. I didn’t have it inside my house.” He assumed CCA would provide the opportunity to grow as an artist in relation to the social context under which he enrolled in school; but he quickly discovered that the curriculum did not reflect any aspect of his experiences. In fact, Villa left CCA after one year, returning in 1958: “I went in there in 1955 as a freshman. . . . And then I dropped out for one year out of college” (Esteban Villa, interview, January 7, 2004).

While Villa did not directly relate his departure to the school’s lack of socially relevant curriculum, he alluded to it when he recalled meeting José Montoya once he returned to CCA. Montoya transferred to CCA from San Diego City College in 1958, and Villa mused, “There was only two Mexicans on the whole campus—me and José. A gang! They said, ‘Oh my God, there’s two of them now.’” Aside from befriending Montoya, Villa found that not much else had changed: “Again, there was no nada—no cultura that we could identify with. Nothing to identify with and no teachers, and no interest by the other professors. So it was kind of like being in the middle of the desert again. There was nothing there. Chicano art didn’t exist” (Esteban Villa, interview, January 7, 2004). Comparing the scarcity of educational opportunities for farmworkers in Bakersfield to the Eurocentric focus of the academy—ironically, the symbol of all such opportunities—Villa poignantly conveyed that his desire for education was infused with a budding labor and class consciousness alongside a growing interest in his cultural and racial-ethnic identity.

After José Montoya transferred to the California College of the Arts, following junior college and his four-year service in the US Navy during the Korean War, he decided to pursue fine art as his interest shifted away from commercial art.5 At CCA Montoya, like Villa, encountered Pop Art, Minimalism, and other avant-garde styles, but he was impressed by the old guard, the instructors who lingered at the art school teaching craft, a term that was dropped from the college’s name in 2003. The college was a former center for crafts learning, and many of its instructors “were from the old German school of design, the Bauhaus,” Montoya recalled. “They revered crafts and making things” (ASU Hispanic Research Center 2013). A German school of design, architecture, and applied arts, the Bauhaus operated in Germany from 1919 to 1932 and philosophically centered on three main principles: “harmony, balance, and rhythm. And after that,” Montoya added, “there were six elements: line, color, value, space, texture, and form” (ASU Hispanic Research Center 2013).

Bauhaus principles resonated in Montoya’s Hispano heritage. Originally from New Mexico, Montoya embodied a mixture of Spanish, Mexican, Pueblo, and other Native American ancestry. On a break from art school, Montoya went on a trip to New Mexico with his father to visit his aunts, whom he recalled “were very Pueblo Indian, more than Spanish” (ASU Hispanic Research Center 2013). He answered their questions about his classes and spoke of the Bauhaus principles. His aunts informed him of the principles’ similarities with the philosophy of Pueblo Indians. Montoya’s reverence for his Hispano heritage colored his experience of Bauhaus concepts at CCA because of the symmetry proposed between the natural world and the built environment. His fusion of Pueblo and Bauhaus philosophies suggests an origin point for his Chicano artistic worldview in the late 1950s.

But while Montoya contemplated the similarities between European and Native American art traditions, he was disappointed by the absence of Mexican and pre-Columbian art in CCA’s curriculum. “Along the way,” Montoya recalled, “we discovered fine arts and discovered Mexican art. But not in the schools.” Frustrated by this absence, Montoya and Villa asked their instructors “why they went so quickly on the three Mexican muralists—Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros—[when] we knew there was more. We knew that there was pre-Columbian art. We were definitely aware of that by the time we started, but we never got any of that in school or got any training.” They challenged their teachers “to acknowledge that there was an incredible cultural treasure waiting for us, or there for us, to tap into.” Montoya surmised, “It was simply Western art was the thing—American art and European art. Everything else was viewed more anthropologically, archeologically—put down [and] the reason was really clear: it was an imposition on Western art” (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004). Montoya and Villa confronted the “idea of a ‘universal’ culture” in their art classes, or, as Eva Cockcroft and Holly Barnet-Sanchez (1993, 9) explain, a single idea of beauty and order. Montoya’s statement that “everything else was viewed more anthropologically, archeologically” reveals how pre-Columbian artworks were treated as exemplars of an ancient past, while Mexican muralism was glossed but not studied. The consequence of assigning pre-Columbian and Mexican art histories to the fields of anthropology and archeology, Lucy Lippard (2000, 12) writes, is that it “freeze[s] non-Western cultures in an anthropological present or an archeological past that denies their heirs a modern identity or political reality on an equal basis with Euro-Americans.”

The absence of an equal basis for Chicano/a identity with that of Euro-Americans only partly addresses the fallout from institutional absences and academic segregations. Chicano/a art did not happen in isolation, but neither did Anglo American, or any American, art history. While early twentieth-century Mexican muralism influenced Chicano/a visual culture in the 1960s and 1970s, so did US federal art programs of the 1930s and 1940s and the Anglo American and African American artists who worked as part of an avant-garde of popular art. As Pop Art and other leading trends affected Esteban Villa’s artistic practices, and Bauhaus principles aligned with José Montoya’s New Mexican heritage, New Deal muralism deeply impacted a generation of Chicano/a artists in the 1960s and 1970s.

African American artists were also influenced by New Deal muralism and the Mexican mural movement before it, further bolstering Montoya’s claim that he “knew there was more” to US art history than the Eurocentric tradition. African American artists attended art schools like the California Labor School in San Francisco, founded in 1942 and accredited under the GI Bill in 1945 (Ott 2014, 893). The California Labor School offered numerous classes in visual art and, according to John Ott, it complemented technical training with courses on black history and culture, many of which were instructed by African American trade unionists (909). Previous decades of populist, labor-oriented, and multiracial art practices culminated in the 1960s and 1970s, when the community mural movement began amid civil rights mobilizations. Chicano/a and African American artists in the 1960s and 1970s were drawing on the same historical, political, and artistic precursors.

“We knew there was more”: An Art Historical Afro-Chicanidad

The verbal-visual architecture built by artists of color in the 1960s and 1970s was created on preexisting foundations of populist art and transnational encounters, proposing an aesthetic history of Afro-Chicanidad. African American artist William Walker mentions his awareness of New Deal muralism in his reflections on the Wall of Respect, the first community mural created in Chicago by the Organization for Black American Culture, AfriCOBRA, and local residents in 1967. Painted in Chicago’s South Side at Forty-Third and Langley Streets, the Wall of Respect incorporated portraits of black heroes from music, literature, sports, politics, and literature. Cockcroft, Weber, and Cockcroft (1998, 1–3) write that the mural proclaimed that “black people have the right to define black culture and black history for themselves.” For William Walker, the experience of painting the Wall was one “he had been waiting for” and his “chance to address his people directly in paint” (Cockcroft, Weber, Cockcroft 1998, 5). Walker also referred to the Wall as a “rebirth of public art,” revealing that he was aware of the public mural program implemented in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP). Creating murals in post offices, public schools, and public buildings across the United States, artists performed a national service under the federal program (Barnett 1984, 408). Numerous community centers were also established between 1935 and 1943 to provide arts training and exhibition space for working- and middle-class communities (408). Through WPA funding, African American artists like Charles White and Charles Alston helped establish community art centers in black neighborhoods, White at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, and Alston at the Harlem Community Art Center in New York (Schreiber 2008, 4, 33). Although WPA-era murals were federally funded, William Walker perceived the 1960s and 1970s community mural movement as the next wave of a progressive public art tradition.

New Deal murals and the concurrent creation of community art centers were also inspired by an earlier period of state-sponsored muralism in Mexico. American artists encountered what Guisela Latorre (2008, 10) calls “a politicized modernist vocabulary” in the Mexican murals that followed the 1910 Mexican Revolution.6 The Mexican government’s public art projects provided a model for the Roosevelt administration’s implementation of comprehensive economic relief during the Great Depression (Barnett 1984, 408).7 The three Mexican muralists—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—whom José Montoya mentions were briefly discussed in his classes, were commissioned in the 1930s to create murals in the United States and worked with American artists. Ben Shahn, for example, assisted Rivera on the Rockefeller Center mural that was destroyed in 1933 due to its depiction of Vladimir Lenin (Hurlburt 1989). In 1936, Siqueiros instructed a political arts workshop in New York City during the St. Regis Gallery’s contemporary art exhibition. Jackson Pollock also participated, assisting on floats for the May Day parade. Orozco lived in the United States from 1927 to 1934, creating murals like Prometheus in 1930 at Pomona College in Claremont, California, and The Epic of American Civilization, painted at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, between 1932 and 1934.

In the spring 1969 issue of El Grito: A Journal of Contemporary Mexican-American Thought, a Chicano/a studies journal founded at UC Berkeley, José Montoya published several of his works, prefacing the collection with an artist statement that takes the form of a poem. Calling out to his parents and art school friends as being the reasons why he paints, in the fourth stanza Montoya (1969) writes, “I paint because I love Orozco and Shahn. / I paint to destroy Orozco and Shahn.” In the building up and tearing down of canonical artists and the national art histories that he encountered in school, Montoya expressed his desire for the formation of Chicano/a art. While the connection he poses with Orozco is expected, Montoya’s association with Shahn is not. But perhaps it should be expected, since Shahn’s exaltations of the American worker were part of Montoya’s education at CCA, revealing an artistic convergence in his development as a Chicano artist. Shahn is one of the canonical American artists who did not abandon figuration or social content during the postwar period, despite the establishment’s shift to Abstract Expressionism. Serving as director for the graphic design division of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, Shahn produced union posters like For Full Employment After the War, Register, Vote (1944). In the image, better known as Welders, Shahn uses the illusion of large scale to heroize two workers, a technique that John Ott (2014, 900) claims produces a certain visual dignity.

Paralleling the influence of Shahn on Montoya, Mexican muralists were also well known to African American artists in the 1930s and 1940s. Charles Alston was deeply impacted by the work of Orozco and Rivera, meeting the two artists when they created murals in New York City (Coleman 2000, 15, 17–18). African American artist Hale Woodruff apprenticed with Rivera in 1936, learning mural techniques and traveling to Cuernavaca to continue studying murals, where he observed how the “Mexican mural movement focused on the resistive spirit” (Coleman 2000, 16). While most African American artists encountered the Mexican muralists and their work in the United States, Rebecca M. Schreiber (2008) tracks African American artists in exile during the 1940s, particularly Elizabeth Catlett, who went to Mexico in 1946 along with Charles White to work with the Taller de Gráfica Popular. The workshop of popular graphics was a political art collective that produced affordable art for ordinary Mexicans (Schreiber 2008, 38). Inspired by the workshop’s portfolio of posters Estampas de la Revolución Mexicana (1946), a series of portraits of revolutionary leaders and heroic scenes from the 1910 revolution, Catlett created The Negro Woman, a series in which she presented a visual history of heroic African American women of the antebellum and postbellum US South (Schreiber 2008, 40–41). The influence of the Taller de Gráfica Popular on Catlett’s artistic philosophy cannot be overemphasized, but the point of this abridged history of collaboration between African American and Mexican artists in the 1930s and 1940s concerns definitions of transnationalism in art history. Artists of color never were (or are) “simply contained by the nation,” but, as Schreiber writes, circulate across national boundaries, fusing aesthetic ideas and creating art that does not value “political borders as their ultimate horizon” (xix, xii–xiii).

For Chicana/o artists who formed pivotal collectives in the 1960s and 1970s, murals created by Mexican muralists in Northern California exemplify what Emory Elliot (2007, 10) calls the “fluid transnational cultural borderlands” in which “many people of color lived.” Located in a gallery at the San Francisco Art Institute, Diego Rivera’s The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931) presents Rivera’s back to viewers as he sits atop scaffolding while other artists erect a large portrait of a worker. The central panel is flanked by scenes of workers building, designing, and servicing a modern city’s infrastructure. RCAF artist Stan Padilla received his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969 and his MFA in 1971 (Stan Padilla, conversation with author, January 12, 2016). Likewise, Patricia Rodriguez, who studied with Esteban Villa and José Montoya at CSUS for an MFA she earned in 1975, received her BFA from the Art Institute in 1972 (Mesa-Bains 1991, 138). Both artists would have encountered Rivera’s mural on a daily basis. A visual exaltation of the working class, Rivera’s mural expresses a political perspective that was not lost on Padilla or Rodriguez, both of whom formulated community-based arts practices while training at an elite art school. Despite the different circumstances under which they were at the San Francisco Art Institute (they were students and Rivera was a celebrated muralist), Padilla and Rodriguez identified with the mural’s anti-elitist message.8

Chicana artist Irene Pérez also recounts meeting Emmy Lou Packard, an American artist who worked with Rivera on another San Francisco mural. Pérez cofounded Las Mujeres Muralistas with Patricia Rodriguez and several other women in San Francisco during the 1970s. Pérez recalls that Packard “painted the mural at Coit Tower” and that she “was very helpful. We consulted with her, and she told us a lot about the technical stuff and about working together as a group. It was exciting to have a historical connection with somebody who worked with Rivera” (Ochoa 2003, 41). Political ideas ingrained in Mexican revolutionary art circulated across geopolitical borders. Pérez’s reflections on Packard and Rivera exemplify a continuous, transnational American art history across the twentieth century, but only when the periphery of US art history is moved to the center of the field. A move such as this is crucial for clarifying transnationalism in art as a conversation, or web of influence, that never really stops. Typically, art history posits transnational influences in Latin American art in relation to power,9 but larger political contexts and economic changes, like the Mexican Revolution, the Great Depression, and New Deal legislation, catalyzed intimate and unaccounted-for meetings between artists across race, ethnicity, nationality, class, and gender—irrespective of epoch.

Transnational artistic influences do not stay in their place or remain fixed in a historical period. Instead, they build upon each other, verbally and visually. They spread by word of mouth, through shared memories of intergenerational conversations, and in looking at murals of an earlier era located in art school galleries or Art Deco towers. When Stan Padilla, Patricia Rodriguez, and Irene Pérez’s encounters with Rivera’s murals are recognized as important moments in American art history, US murals of Mexican descent and their politicized modernist vocabulary are not muted until a “special juncture” occurs due to larger economic and political interests (Latorre 2008, 10; Goldman 1994, 268). Rather, these encounters are ongoing “political and cultural centers of contact and exchange,” mixing and fusing in the borderlands of national art histories (Elliot 2007, 10).

New World Mestizo/a Art

Chicano/a art began as a fusion of “mainstream as well as experimental pan-American genres and styles,” writes Alicia Gaspar de Alba (1998, 41), adding that it draws on “Mexican, Euro-American, Native American, and Chicano/a popular culture” to produce “a truly New World mestizo/a art.” These artistic borderlands also include African American artists who blended multiple contents, forms, and ideas to express their sociopolitical realities throughout the twentieth century. But New World mestizo/a art is “not technically a value in the same sense that freedom or individualism are values,” Gaspar de Alba cautions, reminding us that it is not an aesthetic version of US exceptionalism, a value system that elides conquest, rape, enslavement, and spiritual and cultural subjugations. Rather, it revalues racial and cultural mixtures as an artistic process, encompassing the transnational diasporas that spread imageries and cultures along with conquered and displaced peoples (Gaspar de Alba 1998, 41).10 Through an ongoing process, New World mestizo/a art is never resolved or finished; rather, it is always absorbing and transforming because it is in dialogue with the history of social reality and the history of its construction.

New World mestizo/a art as an aesthetic process and as a history of the construction of Chicano/a social reality is foregrounded in RCAF artists Luis González and Ricardo Favela’s 1976 poster Cortés Nos Chingó In A Big Way The Hüey.11 Available for viewing on Calisphere, the poster visually engages pre-Columbian mixtures as it presents Luis González’s verse “Cortés Poem.”12 González’s poem is inlaid within an indigenous pattern reminiscent of papel picado, an artisanal craft from Mexico in which intricate designs are cut into delicate paper. The papel picado motif highlights the poster’s formal construction.

Upon closer examination, the elaborate design is actually the huelga eagle, the United Farm Workers emblem (Jackson 2009, 91). In the context of the poster, the eagle simultaneously functions as a reference to the farmworkers’ movement and an allegory for the founding of the Aztec city-state of Tenochtitlan. The color spectrum in the poster’s background, with blue and green edges on the left and right sides merging in the center, evokes a color field where land and water meet, underscoring the poster’s reference to the founding of Tenochtitlan. As the colors join and turn yellow, the poster visualizes the “points of convergence” that set the stage for the poem (Romo 2001). González and Favela’s attention to the color spectrum and design suggests that they were thinking about the poster as poetic space, using serigraphy not only as a tool to announce events and to disseminate information, but as a platform to articulate decolonial ideas.

The formal details of González and Favela’s poster also reveal the discourse in which they and other Chicano/a artists remapped the world beyond colonial histories. Many of these decolonial conversations took place in foundational Chicano/a literary spaces, including journals like El Grito at UC Berkeley as well as early anthologies of transnational poetry and prose published during the Chicano movement. In fact, the lack of Chicano/a publication space for literature, art, and history was one of the reasons Luis González printed “Cortés Poem” on a silkscreen poster. That method “offered him the ability to self-publish,” Terezita Romo (1993, 2) writes, adding that “his chances for publication from a mainstream publisher were slim because of his Chicano subject matter and bilingual text.”

In 1972, El Teatro Campesino founder Luis Valdez intervened on the absence of Chicano/a literary space when he published Aztlán: An Anthology of Mexican American Literature. He reinforced the importance of indigenous ancestry to Chicano/a identity by proposing the term “Indigenous America,” rooting the term in pre-Columbian cultural mixtures that occurred through successions of indigenous civilizations before European contact (Valdez 1972, xiv). “This was not a new world at all,” Valdez writes. “Tula, Teotihuacan, Monte Alban, Uxmal, Chichen Itzá, Mexico-Tenochtitlan were all great centers of learning, having shared the wisdom of thousands of generations” (xvii). Before the Spanish, Valdez adds, “there were the Toltecs, Mixtecs, Totonacs, Zapotecs, Aztecs, and hundreds of other tribes. They too were creators of this very old new world” (xvii). Indigenous cultural convergences, evident in the fusion and diffusion of deities like Quetzalcoatl in art and architecture over regions and centuries of Mesoamerica, reveal a proclivity for precolonial mixtures.

Assembling a literary anthology that includes excerpts from the Popul Vuh, Aztec songs, nineteenth-century journal entries, letters from the Mexican-American War, border ballads known as corridos, and political manifestos written during the Chicano movement, Valdez introduces the anthology by claiming that it rejects “efforts to make us disappear into the white melting pot. . . . Some of us are dark as zapote, but we are casually labeled Caucasian. We are, to begin with, Mestizos—a powerful blend of Indigenous America with European-Arabian Spain, usually recognizable for the natural bronze tone” (xiv). Evoking the color-coded language of José Vasconcelos’s “La Raza Cósmica” (1925), which proposed a modern identity for Mexicans through Mexico’s racial mixtures, Valdez defines the darkness of the mestizo/a as native to the flora of the Western Hemisphere. He does so to counter “melting pot ideology,” or what Gaspar de Alba (1998, 40) describes as “historical and cultural amnesia” in hegemonic US culture that disremembers wars and the annexations of territories and privileges a popular culture in which “Chicanos/as were seen and learned themselves as ‘immigrants or the children of immigrants in a new land.’”

Luis Valdez was part of the RCAF’s milieu in the 1960s and 1970s, and the concepts he put forward were echoed by RCAF artists in posters like Cortés Nos Chingó In A Big Way The Hüey, which fuses indigenous and colonial symbols with contemporary political emblems irrespective of geopolitical borders. While the term “Indigenous America” is problematic from a twenty-first-century perspective of race and ethnicity because it reduces Native American identities, cultures, and colonial oppressions during Spanish, English, and US colonization, in the term’s historical moment it was an enunciation of a decolonial consciousness. “Indigenous America” expressed a tactical subjectivity by redefining the concept of the “New World” to mean something else for the ancestors of the native peoples it was forced upon (Sandoval 2000). It expressed the shared concerns of Chicanos/as and Native Americans, who worked together in the 1960s and 1970s on related issues (Pérez-Torres 2006, 16). These coalitions developed because, as Rafael Pérez-Torres writes, the “discourse of mestizaje” allowed Chicano/a artists to see their “shared colonial as well as racial history” with “Native Americans and other indigenous groups across the Americas” (16).

The “Indian Chicano” Idea at D-Q U

The idea of a New World mestizo/a art was made real through the building of institutional spaces for learning about “Indigenous America”—a history in which the RCAF was directly involved. In 1971, Chicano/a and Native American students and professors helped found D-Q University in Northern California, roughly an hour from San Francisco and near the campus of UC Davis (Land of Two 1971). Abandoned by the US Army in 1967, the land was taken over by the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and then slated for acquisition by UC Davis (“DQU Is Granted Site” 1971). Native American students, many of whom were enrolled at UC Davis, occupied the land after they learned that their efforts to obtain the land to start a college named Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University were going to be bypassed (“Indians Seize Base” 1972). On the heels of the occupation of Alcatraz by Red Power activists in 1969, the student occupation of the 640-acre parcel led to the “Indian-Chicano” college in 1971, announced in the inaugural issue of the D-Q University newspaper as a school founded on the need for intellectual space: “Our Indian and Chicano people possess a great deal in common in racial heritage, our cultural traditions, [and] life values [that] differ from the dominant society” (Land of Two 1971). Named after “Deganawidah, the founder of the Iroquois Confederacy, and Quetzalcoatl, Toltec leader, statesman, and deity from central Mexico” (Goldman and Ybarra-Frausto 1985, 38), the university newspaper presents its text in English and Spanish following a frontpage headline that proclaims: “INDIAN-CHICANO.” The headline is complemented by a symbol of a bird that merges a Native American thunderbird with the Aztec eagle to visually reinforce the “Indian-Chicano nature of the institution” (“Dedication of Two Flags” 1971).

RCAF artists taught courses at D-Q University. José Montoya and Esteban Villa’s 1971 Chicano Art class is listed in the university newspaper along with classes named The Indian in Literature, Southwest Religion and Philosophy, and Social Welfare in America, the latter described as an “inquiry into the social welfare system of America as it relates to Indians and Chicanos” (Land of Two 1971). Carlos Jackson (2009, 91) writes that to help raise funds for the school, Luis González designed Announcement Poster for DQU Benefit (n.d.), a print in which he visualized “ethnic unity through printing the labels ‘Chicano/Indian,’ as if they were interchangeable or one.” González’s poster can be seen on Calisphere, and viewers will note that he did not use a slash between “Chicano” and “Indian” in the text.13 Instead, he presented “Chicano Indian” without any division or bridge—similar to Luis Valdez’s presentation of “Indigenous America.” While this may seem a belabored point, the thought put into a hyphen or a slash, or their absence, reflects deliberate choices in the visual representations of complex concepts of identity through textual abridgements. The slash evolved in the late twentieth century as an important signifier in critical race studies and the intersections of gender and sexuality on racial and ethnic designations. The slash is often debated for its lack of inclusivity, and other signs have been introduced to encompass people who do not identify with heteronormative gender and sexuality norms. Yet Luis González saw no need for a slash or hyphen, in the same way that Luis Valdez writes of no divisions between “Indigenous America.” No dividing or bridging line is used, because the emergent unity was not about sameness—or the conflation of colonial histories for Chicanos/as and Native Americans—but rather about the unification of similar calls for self-determination in the 1960s and 1970s civil rights era.

Parallel calls for self-determination were also presented in the name of D-Q U’s newspaper, the Land of Two, a space where Chicanos/as and Native Americans pursued “a lineage to a pre-Columbian past beyond mere biology” and “insisted that political legitimacy—and even psychic well-being—rested upon the reclamation of what they proposed was a still vibrant indigenous cultural heritage” (Oropeza 2005, 84). The psychological fallout from borders, or a literal slash between the histories of native peoples, is a major theme of Luis González’s “Cortés Poem” in the poster Cortés Nos Chingó In A Big Way The Hüey. While the color spectrum and design of the poster account for precolonial and contemporary political mixtures as formal elements, the poem communicates the destruction of indigenous knowledge from the Spanish conquest to the present-day barrio. The poem moves through a historical succession of Spanish, French, US, and internal “conquests” that compose Mexican history. González writes,

Cortés nos chingó in a big way

españa nos chingó in Spanish

francia nos chingó with music

los estados unidos nos chingó un chingote

santa ana nos chingó like a genuine chinguista

porfy nos chingó for a long time

y nosotros nos chingamos

i swear!!!

In eight short lines, González describes the history of colonial destruction but also alludes to the construction of a hybrid Mexican culture out of which Chicano/a artists created a New World mestizo/a art.

González’s elaborate conjugation of the verb “chingar,” for example, responds to Octavio Paz’s meditation on the cultural implications of “chingar” in The Labyrinth of Solitude (1961), illuminating the intellectual dialogue in which Chicano/a artists were engaged. Creating a linguistic map of the verb, Paz (1985, 75–76) accounts for different but related meanings of “chingar” in Latin America. Finding that the word is closely associated in indigenous cultures with making alcoholic drinks—or the residue of the fermenting process—Paz adds that in “Spain chingar means to drink a great deal, to get drunk” (76). While not named, Chicanos/as are implicated in Paz’s definitions of “chingar” through the position he takes on Pachucos/as, a generation of Mexican Americans in the 1930s and 1940s who innovated a uniquely syncretic culture of fashion, language, and ethos known as la pachucada or pachuquismo. In “The Pachuco and Other Extremes,” an essay published as the first chapter of The Labyrinth of Solitude, Paz’s description of Pachucos/as echoes the semantic development of “chingar” because he perceives them to be the residue of Mexican culture. As “a tangle of contradictions, an enigma,” Pachucos/as, Paz claims, were a fragmentation of an authentic self: “Even his very name is enigmatic: pachuco, a word of uncertain derivation, saying nothing and saying everything” (1985, 14). Paz’s reduction of Pachucos/as as strange and meaningless paralleled their portrayal in US media as political subversives and a threat to the nation-state during World War II. Between Paz’s rejection and the denunciation in US popular culture, Pachucos/as were pushed beyond the bounds of citizenship and a common humanity.

In “Cortés Poem,” Luis González impersonates Paz’s definitions of “chingar,” locating the destructive forces of conquest in his barrio, as epochal battles turn into minuscule quarrels in the everyday lives of Chicanos/as. González writes,

maybe if gloria stops hassling maría

and josefina quits messing around with josé

whose carnal héctor is gonna put ramón’s luces out

y tal vez if jorge makes up with carlota

maybe things wouldn’t be so bad

but you know how it is . . .

González critiques the consequences of colonial subjugation in the minutiae of barrio life; but he does so sardonically to maneuver against Paz’s characterization of Pachucos/as and their Chicano/a descendants.

In fact, in the poem’s conclusion, González performs the stereotype that Paz crafts for Pachucos/as. Imitating his elaborate conjugation of “chingar,” González uses “the polyglossia characteristic of Chicano linguistic expression” to poke fun at Paz’s hermetic thesis on the disintegration of Mexican culture in Chicano/a communities (Pérez-Torres 2006, 90). González writes,

while manny’s cousin got jumped by chuy and tavo

after the dance where chris got shot in the earlobe

by one of the garcías who was really trying to get

paula’s little sister for spreading chismes

about how unreasonable and hot tempered the garcías are, man . . .

que tiempo tan chingado,

excuse me please,

i’m gonna go look for ricardo

to watch me kick

clint eastwood’s honky ass!

If, as Paz writes, “chingar also implies the idea of failure” and “always contains the idea of aggression” (1985, 76), González’s poem tactically fails as he laments the drunken barrio brawls but ultimately becomes sidetracked by his nature, or digresses into aggression. Arriving at internal conquest, González proves Paz’s definitions of the verb, satirizing his essentialist claims of Mexican identity.

Further, by ending on the lines, “i’m gonna go look for ricardo / to watch me kick / clint eastwood’s honky ass!” González extends Paz’s disdain for Pachucos/as to the portrayal of Mexicans in US popular film. González’s desire to fight Eastwood in front of an audience, or in front of Ricardo, is funny because it is futile; but in its irony, the poem destabilizes stereotypes of Mexico and Mexicans in the Western imagination (Lipsitz 2001, 73). Significantly, it is the poster’s form—the color spectrum and UFW-Aztec eagle—that signals the irony because it visually challenges essentialist claims of national identity. Through color and design mixtures, González and Favela articulate the “organic theories” that Karen Mary Davalos (2001, 11–12) ascribes to mestizaje and diaspora as aesthetic tools of fusion and diffusion in Chicano/a art.

The Third Root of New World Mestizo/a Art: Black in Latin America, circa 1972

Luis Valdez introduced the term “Indigenous America” in his anthology to politically align Chicanos/as and Native Americans through a decolonial vision of the Western Hemisphere. He also extended the decolonial vision to Africans, gesturing to Afro-Chicanidad in 1972 in his reference to racial mixtures between Africans, Europeans, and indigenous peoples as the ancestral roots of Chicanos/as. The introduction to Valdez’s anthology, then, is a record of the milieu in which Chicano/a and African American artists created a decolonial language through visual art, alternative press, and literary publications.

Addressing the colonial moment in which Chicano/a and African American histories became intertwined, Luis Valdez (1972, xiv–xv) writes that “there were more black men in Mexico than white” by 1531, a decade after conquest. When “Negroes were brought in as slaves,” Valdez adds, “they soon intermarried and ‘disappeared,’” resulting in “an incredible mestizaje, a true melting pot. Whites with Indios produced mestizos. Indios with blacks produced zambos. Blacks with whites produced mulattoes. Pardos, cambujos, tercernones, salta atrases. . . . Miscegenation went joyously wild, creating the many shapes, sizes, and hues of La Raza. But the predominant strain of the mestizaje remained Indio” (xv). While Valdez claims African heritage for Chicanos/as, he uses the term “Negroes,” spelled in English and connoting a different history for African Americans in the United States that is related to, but distinct from, the Spanish version of the word. While the Spanish word, “negros,” was pervasive throughout the slave trade that followed European conquests in 1492 and 1521, “Negroes” in the United States developed as a preferred or self-chosen term among African Americans in the early twentieth century and was called into question by African American civil rights leaders in the 1950s and 1960s. Using US terminology alongside colonial designations, Valdez also upholds the emphasis on indigeneity in José Vasconcelos’s “La Raza Cósmica,” the treatise that formulated a modern Mexican nationality but elided African heritage. Yet Valdez intends all of these meanings and contradictions in the cultural borderlands of Chicano/a identity formation. Like Luis González’s “Cortés Poem,” in which González challenges Octavio Paz’s intellectual treatise on Pachucos/as and calls out Clint Eastwood for the stereotypical portrayals of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in his films, Valdez is in a messy dialogue with the colonial histories and contemporary realities of two nations.

Nevertheless, Luis Valdez romanticizes miscegenation as the principal process of Mexican mestizaje, which he deems “the true melting pot.” Racial mixture in relationship to slavery in Latin America was not a “joyously wild” process; rather, it was one that was meticulously categorized and ordered, evident in the terms Valdez lists for mixed-race peoples, or “zambos,” “mulattoes,” “pardos,” et cetera, which were visualized in colonial casta paintings. A New World art, casta paintings tracked and categorized the racial mixtures of people in the colonial era (Katzew 2004, 5). The tracking of New World racial mixtures was primarily done for the benefit of Europeans, particularly Spaniards, who experienced Nueva España through the circulation of such paintings. In the New World, casta paintings supported the subjugation of mixed-race people, especially those with African heritage.14 In fact, as Valdez writes that Africans intermarried and then “disappeared,” he signals the simultaneous acknowledgement and denial of blackness in Chicano/a communities as well as in Mexico that continues today.15

But in 1972, and despite its insufficiency, Valdez gestures to the African root of Mexican history to buttress the African American and Chicano/a political alliances that were occurring in the US civil rights era. Publications like Valdez’s anthology were largely doing in the 1960s and 1970s what scholars in the twenty-first century do (and undo) to national histories using hemispheric and decolonial lenses. The history of graphics in the 1960s and 1970s underground press illuminates a continuous intervention on US and Mexican national histories. Like The Land of Two, D-Q U’s newspaper that politically aligned Chicanos/as and Native Americans, the alternative press disseminated sociopolitical alliances between Chicanos/as and African Americans, evincing their interactions and influences on each other (Pulido 2006, 3). Black Panther Party members were aware of Brown Berets because they read about them in the Black Panther newspaper, which covered issues facing Chicano/a communities, particularly in urban areas (Pulido 2006, 167). A principal space for the circulation of prose, art, and commentary on the oppression of African Americans, the newspaper launched in 1968, sharing space with the Brown Berets and announcing a Panther-Beret alliance to its national readership (Ogbar 2006, 257).

In 1969, for example, the Black Panther Party offered Los Siete de la Raza, a Chicano/a and Latino/a activist-artist group in San Francisco, one side of its weekly paper (Davalos 2008, 40).16 Chicana artist and Los Siete member Yolanda López worked with Emory Douglas, the Black Panther Party’s Minister of Culture and principal image maker, on the Black Panther (41). López was influenced by Douglas’s “new visual vocabulary,” Karen Mary Davalos writes, which visually inspired the newspaper’s readers to reject “images of the complacent slave, the illiterate good-for-nothing, the savage brute, and the minstrel” (42). Alternatively, Davalos contends, Douglas “visualized the qualities of Huey P. Newton and Eldridge Cleaver, intellectual and strong black men of power, and offered them for African Americans as a source of self-determination” (42). Agreeing with Douglas that “images function to raise revolutionary consciousness,” López “repeatedly borrowed the Black Power fist” but modified it to convey themes of hope and not only of political resistance (41). For the 1969 cover of the alternative newspaper ¡Basta Ya!, López altered the raised fist, opening it and extending the hand “to the sky, holding a broken chain” (47–48).

In tandem with the Black Panther newspaper, El Grito del Norte was founded in 1968 to disseminate news of Reies López Tijerina’s Alianza Federal de las Mercedes in New Mexico. Reporting on Alianza’s demonstrations and courtroom battles over land rights, the newspaper also covered Black Power and the American Indian Movement alongside international mobilizations (Vasquez 2006, xiii). Toward a New World mestizo/a art, artists of color fashioned a verbal-visual vocabulary in alternative press that imagined a broad-based community of disenfranchised peoples (Pérez-Torres 2006, 90).

The Royal Chicano Air Force also gestured to an Afro-Chicanidad in their posters. In 1977, RCAF artists Juan Cervantes and Luis González created Announcement Poster for the Committee to Abolish Prison Slavery, which can be viewed on Calisphere.17 Focusing on the shared legacies of colonial oppression for Chicanos/as and African Americans, the poster shows two hands rising up from the bottom of the image as chains frame the entire composition. The artists included text from the US Constitution’s Thirteenth Amendment and a quote from the Emancipation Proclamation. The combination of imagery and text conveys that the poster’s call for justice and liberation was very much in dialogue with the tenets of the nation.

Direct engagement with the democratic principles and legal documents of the United States was a well-worn tactic for artists of color by the time Juan Cervantes and Luis González “pulled” their poster. Following the creation of the Wall of Respect in 1967 in Chicago, William Walker and other artists reproduced the “Wall” concept in murals in Chicago and Detroit, including the Wall of Truth (1969) across the street from the Wall of Respect.18 Over the title of the Wall of Truth, a panel was hung with the inscription, “We the People / Of this community / Claim this building in order / To preserve what is ours” (Cockcroft, Weber, and Cockcroft 1998, 7). The caption appropriates the patriotic refrain of the US Pledge of Allegiance, situating the mural’s reclamation of public space within verbal codes of citizenship to morally critique the absence of these rights for African Americans.

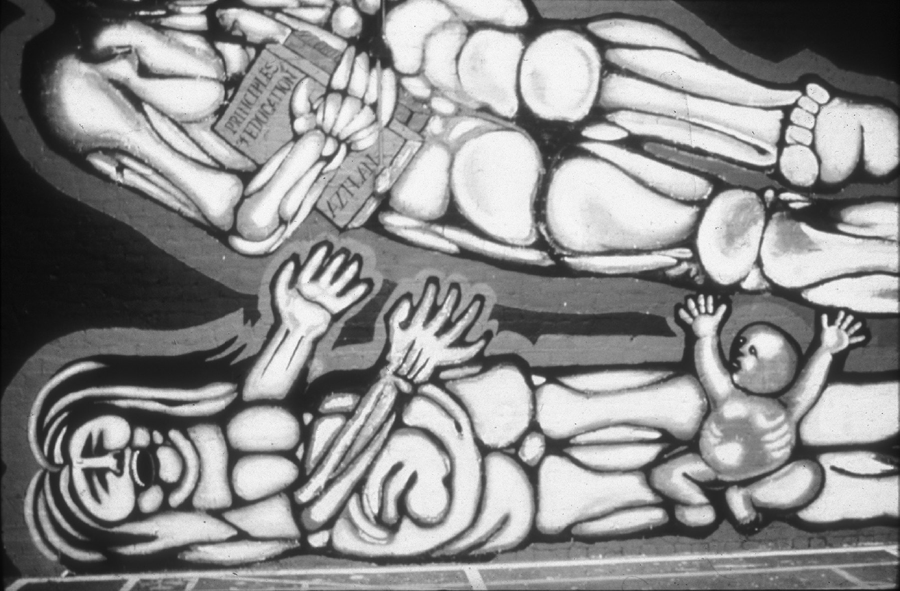

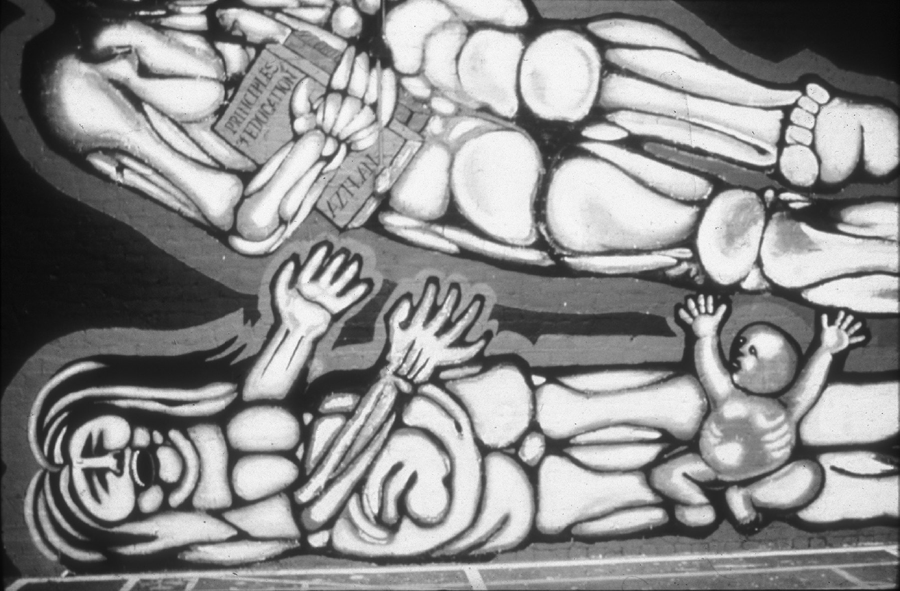

Resonating with the Wall of Truth’s political use of the doctrine of citizenship, Juan Cervantes and Luis González used chains and hands in their poster to reference colonial slavery in a contemporary critique of mass incarceration. But the RCAF artists depicted the hands as skeletal, which not only signals the history of colonial slavery in the Western Hemisphere, but also references la calavera in Chicano/a visual culture. La calavera, also known as a calaca, is a skeletal figure adapted from the work of nineteenth-century Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada, who popularized caricatures of skeletons to satirize Mexico’s ruling classes during the Porfiriato. Skeletal hands and chains were readable images for artists of color and their communities in the 1960s and 1970s since the “Black Power fist” was a central icon of the Black Panther Party; its use in RCAF artwork signaled solidarity with the Panthers’ “political coalition building against racism, material inequality, and US imperialism” (Davalos 2008, 41).

Cervantes and González altered the Black Power fist by opening both hands as they rise up from the bottom of the poster. Creating New World mestizo/a art, Cervantes and González did not efface the connotation of the iconic chains and skeleton, or invent whole new meanings; rather, they drew upon the colonial meanings of the chains of slavery and Posada’s critique of social decadence via la calavera, remixing their meaning through the intertextuality of the images. “Racialization is a relational process,” or, as Laura Pulido (2006, 4) explains, “the status and meanings associated with one group are contingent upon those of another.” Cervantes and González extracted the historical connotations of the images to expose connections between late twentieth-century abolition movements, the classes who economically profit from slavery, and the colonial histories of African enslavement in the United States and Mexico.

Moreover, the use of skeletal hands in the poster renders race ambiguous while maintaining an unambiguous moral position for a diverse audience. The poster, after all, was an announcement for a committee to abolish prison slavery in Berkeley, California, suggesting that membership was wide-ranging and centered on a common cause and not racial identity. The body that Cervantes and González reference through skeletal hands is aesthetically a mestizo/a one, revealing that they were thinking about mestizaje as a process for the fusion and diffusion of Chicano/a intellectual ideas. Mestizo/a bodies in Chicano/a art, Rafael Pérez-Torres (2006, 3) claims, “destabilize the unity and coherence integral to racial and gender hierarchies [that] seek to naturalize unequal relations of power.” Absent of color and skeletal, the mestizo/a hands undo the chains of race as well as the colonial identities that are based on notions of purity (3). Cervantes and González visualized an alternative understanding of race that historically was produced by colonial order, like casta paintings; but they revalued racial mixture as a process that Pérez-Torres contends “leads to a third state or condition” (3). The third state elicited by the poster united viewers politically and morally, as the skeletal hands emphasize racial valence, not only as an articulation of colonial impact but as one of aesthetic process. If, as Pérez-Torres argues, it “is the body that serves as the site of tenuous, complex, and conflicted change,” mestizaje “becomes more than a powerful metaphor signaling cultural hybridity. It roots cultural production and change in the physical memory of injustice and inhuman exploitation, of desire and transforming love” (4). Combining the accessibility of poster making “with ‘insider’ signs and symbols based on common folk forms,” Cervantes and González’s poster was made in the cultural borderlands of Chicanidad as it envisions the abolishment of contemporary prison slavery (Lipsitz 2001, 83).

Split Existence Part II: Chicano/a Artists before Chicano/a Art

The Royal Chicano Air Force’s New World mestizo/a art involved a reconceptualization of mestizaje as a formal and intellectual tool for Chicano/a art. Absorbing precolonial and colonial fusions of races and cultures, Chicano/a art reconfigured contemporary symbols and texts of nation-states. But before the Chicano movement and the RCAF’s founding, the idea of a hybrid system of representation for Mexican Americans had been nonexistent in José Montoya and Esteban Villa’s classes at the California College of the Arts (CCA). Montoya’s memories of “why we didn’t hear about” pre-Columbian art or Mexican muralism in the 1950s linger in the twenty-first century, even as college art programs implement concepts and techniques that were initiated by artists of color in the 1960s and 1970s. Institutional investment in “European or Western ideas” sets standards for quality and achievement, “while everything else, from the thought of Confucius to Peruvian portrait vases, was second-rate, too exotic, or ‘primitive’” (Cockcroft and Barnet-Sanchez 1993, 9). The notion that art is not universal but predicated on colonial legacies persists in standards of “quality” that are assumed to transcend socioeconomic and political forces. Yet in actuality, standards of quality uphold a circular logic about what constitutes good art, and “according to this lofty view,” Lucy Lippard (2000, 7) contends, “racism has nothing to do with art; Quality will prevail; so-called minorities just haven’t got it yet.” José Montoya and Esteban Villa’s artistic alienation at CCA led them to seek connections outside of school. Fortunately, “what was good about art school in those days,” Montoya recalled, “was that there were a lot of political causes.”

Montoya was “astounded in Berkeley to be going to parties, to be invited, because we could bring guitars and entertain.” Along with Villa and a small circle of Chicano classmates, Montoya attended parties “that were really leftist [and] Marxist,” an experience that he further described as the “start of us considering the power of the collective.” He added,

The whole notion of existentialism was rampant, and it seemed to encompass all of our simple actions of being Chicanos—dressing the way we did, acting the way we did, and fighting the way we did. Drinking and carousing bereft of rhyme or reason. La locura impressed our professors. They were studying us as models of existentialism. We didn’t even know what the hell the word meant. . . . [At] fundraisers for [the] Fair Play for Cuba Committee . . . we had to sit and say, “Well we just came from fighting the Commies in Korea. Now we’re learning that there was more to it than what we were told.” We were lied to in Korea so badly that they still don’t want to talk about that war. So we became politicized, and that had a big psychic development . . . for us in terms of delving into the different political ways of seeing the world. (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004)

Montoya conveys the impact that college enrollment and political gatherings had on him and Chicano student veterans who were laying a transnational and intellectual groundwork for 1960s and 1970s Chicano/a art. Encounters with international political movements, particularly the tenets of the Cuban Revolution, shaped Montoya’s ideas about “the power of the collective” that later influenced the RCAF’s collective theory and praxis.

Moreover, Montoya’s “psychic development” outside the academy was very much in dialogue with the academy, a tension that would also manifest in the RCAF. Mentioning “la locura,” a shorthand version of the RCAF slogan “locura lo cura,” or “craziness cures,” Montoya contextualized this earlier period of “delving into the different political ways of seeing the world”; this strategy for surviving academia as a Chicano/a would become more visible in the 1970s, when the number of Chicanos/as increased on college campuses during the Vietnam War, amid civil rights mobilizations that coincided with federal and state policies aimed at making universities more accessible to underrepresented populations.

Positioning la locura as a way of dealing with student and faculty gatherings, Montoya suggests the concept was a social maneuver for evading the essentialization of his identity because it maintained assumptions of who he was on the surface (Noriega 2001, 2). Montoya’s claims about “our simple actions of being Chicanos—dressing the way we did, acting the way we did, and fighting the way we did” are replete with subterfuge, since each gesture was not so simple; such performances created a way of being social at parties in Berkeley by providing a protective layer for the war veteran and first-generation college student as he navigated the pressures he felt between the university and his working-class, racial-ethnic, and cultural background. Suspicious of the intellectual terms by which he and other Chicano veteran students were characterized, Montoya quips, “We didn’t even know what the hell the word meant” when he felt they were being studied as “models of existentialism.” Distancing himself from the world of higher education in his recollection, Montoya reveals that “drinking and carousing bereft of rhyme or reason” was a screen identity that kept his humanity intact as he pursued an art degree.

Yet by using “locura” to describe his socializing as “bereft of rhyme or reason,” Montoya also alludes to the melancholy he felt during this period of consciousness-raising. Attending fund-raisers for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, Montoya’s growing international awareness was difficult and, perhaps, painful, since he felt implicated by his lack of third world consciousness during his service as a US sailor in the Korean War. Introductions to political ideologies like communism from a liberationist perspective of the Americas completely contradicted the mainstream patriotic messages he received about “fighting Commies in Korea.” Montoya had joined the navy in 1951 with a specific plan—to use the GI Bill and go to art school so he could “become a cartoonist. That was my big dream” (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004). Using military service as a means to an end, Montoya did not anticipate his role in fighting against the liberation of oppressed people and in defense of US imperialism. “Drinking and carousing bereft of rhyme or reason” suggests that Montoya felt he had been had.

Montoya’s complex recollection, which uses humor to reveal the pain and pleasure involved in early consciousness-raising, was an archetypal experience for first-generation Chicano/a college students in the late 1960s and 1970s. Echoing Montoya’s memories of the CCA and parties in Berkeley, RCAF artists Luis González and Ricardo Favela created Royal Order of the Jalapeño (n.d.), a silkscreen poster designed as a certificate on which one’s name can be added along with the date. Viewable on Calisphere, the poster is an ironic diploma because it works both with and against the institutional process of degree conferment.19 Within a border of orange and black lines wrapped in green vines and an airplane flying over three jalapeño peppers, the certificate reads,

BE IT KNOWN THAT THE CHICANO NAMED HERE. . . . . . . . HAVING COMPLETED. . . . . . . . YEARS OF HIGHER EDUCATION AT. . . . . . . . AND HAVING MAINTAINED A CREDIBLE AMOUNT OF LOCURA WITHIN HIS OR HER BI=CULTURAL SYSTEM:

Y POR HABER SOBREVIVIDO LOS OBSTÁCULOS ACADÉMICOS CONTRA NUESTRA CULTURA CHICANA CON SALSA Y CON SAFOS: IS HEREBY CONFERRED THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE JALAPEÑO ON THIS DATE. . . . . . . .

CHICANO STUDIES AWARD #TÚ(2)

The poster performs the “locura” strategy, which Montoya had performed at parties in Berkeley decades before the poster was made, suggesting that his experience was not unique. Rather, it was the first of many strategies to come for a Chicano/a student body. With a font imitating computer type, the poster awards Chicano/a students for completing their education while maintaining their “bicultural locura despite years in institutions of higher education” (Lipsitz 2001, 75). Through linguistic code-switches, the certificate recognizes a bittersweet accomplishment that a university diploma could not.

Speaking into Being: The Formation of a Chicano/a Artist Identity

Wordplays and code-switches were a central element in building the verbal-visual architecture of Chicano/a identity in the 1960s and 1970s. The formation of a collective consciousness was a process of naming, or redefining and inventing words to express abbreviated concepts of intersecting affiliations. Deciding what to call oneself and the group to which one belonged was an important moment in 1968 when Esteban Villa founded the Mexican American Liberation Art Front (MALA-F) with René Yañez, Manuel Hernández-Trujillo, and José Montoya’s younger brother, Malaquias, in Oakland, California. The name of the art collective was infused with an amusing bilingual code-switch, as the acronym “MALA-F” translates in English to “the bad F.”

But the designation of a self and group identity was also an evolutionary process, exemplified by the use of “Mexican American” in the MALA-F’s name. Members “chose ‘Mexican American’ instead of ‘Chicano,’” Terezita Romo (2011, 42) writes, “reflecting the transitional nature of the early years of the Chicano movement as activism shifted toward a new political identity.” By 1965, “Chicano” emerged amongst a growing populace of Mexican Americans as a self-designation and as a tool for “liberating the US Mexican community from de facto internal colonization” (Sanchez-Tranquilino 1993, 88). “Calling oneself ‘Chicano,’” Marcos Sanchez-Tranquilino asserts, diverged from the “assimilationist generations of Mexican Americans” and undermined the dominant cultural narrative of the melting pot (88).

When Esteban Villa and José Montoya graduated from the California College of the Arts, in 1961 and 1962 respectively, they were not yet “Chicano” artists in name. Villa went to work as a high school art teacher in Linden, California, and Montoya taught high school art in Wheatland, California. Both men became active in the National Farm Workers Association (later renamed the United Farm Workers) that César Chávez and Dolores Huerta founded in 1962. During summer breaks, they took road trips together, including one to Mexico in 1964, visiting workshops and homes of the Mexican muralists.20 In the summer of 1965, they returned to the California College of the Arts in the San Francisco Bay Area on professional development scholarships (Esteban Villa, interview, January 7, 2004).

Thus, “there were many years” between Montoya and Villa “leaving the Bay Area and the beginning of the Chicano Art Movement,” RCAF member Juan Carrillo writes. The interim years included the assassinations of President Kennedy in 1963 and Malcolm X in 1965. Those years also saw increasing US involvement in the Vietnam War and the development of a national dialogue about it, and not only amongst white college students but within communities of color. “For us,” Carrillo explains, “the deaths of black and brown soldiers at rates beyond our populations touched on issues of poverty, education, and racism. These newly rising forums included artists. Imagine seeing El Teatro Campesino performing in urban settings, educating the public on the lives of farmworkers and the interrelationships of their poverty to the structure of agriculture and agribusiness.” El Teatro Campesino “tied all that to the roles of law enforcement, the business community, race, and education,” in performances for Chicano/a audiences. But El Teatro Campesino was “not alone,” Carrillo adds: “The San Francisco Mime Troupe did the same. The Free Speech Movement did the same. The rising role of black students on Southern campuses demonstrated the power of students and educators in raising issues.” For José Montoya, Esteban Villa, Juan Carrillo, and other Chicano/a students, the early 1960s established a multipronged pathway to “articulations of decolonial constructs of Mexican American identity” (Juan Carrillo, email to author, February 7, 2015). From African American student mobilizations in the South, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1960 and the Freedom Riders in 1961, to California-based mobilizations, such as the Free Speech Movement in 1964 and the advent of El Teatro Campesino in 1965, the MALA-F artists built upon a broad base of political efforts in 1968 to articulate a Chicano/a identity.

In regard to the verbalization of Chicano/a identity, Juan Carrillo’s comments touch on El Teatro Campesino’s performances of actos for farmworker and allied audiences, revealing that the process of naming was also performative. Quite literally, calling oneself Chicano/a was a speech act. Certainly, the farmworkers’ theater performed into being a political cognizance amongst disenfranchised farmworkers; but the troupe also performed on college campuses, and many troupe members were aware of multiple theater traditions. Growing up in a farmworking family in Delano, California, Luis Valdez studied theater at San Jose State University, learning the works of German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht as well as Russian agitprop theater, both of which influenced political theater in the United States during the early twentieth century (Huerta 1982; Bagby 1967). Training with the San Francisco Mime Troupe for a year before joining the farmworkers’ movement, Valdez worked with other El Teatro Campesino members to create actos, or improvised performances that were staged in farm fields during the march from Delano to Sacramento to sustain the strikers and educate them on UFW efforts (Rosales 1997, 138; Bagby 1967, 77).21 Actos synthesized Mexican and European theater traditions, marking another convergence of east-to-west and south-to-north trajectories for a New World mestizo/a art.