Enemy Invaders

Did you ever have a cut that took a long time to heal? The skin around the cut probably looked red and even felt a little warm. And when you picked part of the scab off—admit it, that's what everyone does—some yellowish pus oozed out. Yuck! An infection.

If you're a healthy person, your cuts usually heal without a problem. So, what went wrong this time? “Germs” got into the cut, and your body's defense system didn't fight them off fast enough. That's the simple, plain- English explanation. Scientifically, it's more complicated.

First, you need to know that trillions of microscopic bacteria (germs to you and microorganisms to scientists) live on your skin, in your mouth, in your gastrointestinal tract, and in other areas inside your body. Most of them cause no harm, and in fact actually help you maintain good health. Some of these bacteria hitch a ride into our bodies by living in the foods we eat. For example, some yogurts contain “live cultures” of bacteria called Lactobacilli that live in your gastrointestinal tract and aid digestion. Other harmless bacteria help you by just multiplying so much that they don't leave room for harmful microorganisms to survive.

A Word About Bacteria

Not all bacteria are harmful. Many are even helpful.

That's why some yogurts you eat are made with “live cultures” of Lactobacilli, which aid digestion.

Second, you're protected because your body's immune system works 24/7 to keep harmful bacteria, viruses, and other disease-causing invaders (“pathogens”) from multiplying and causing problems.

Here are the basic facts about those germs living inside you:

Q: What exactly is a microorganism?1

A: A living thing that is so tiny that it can be seen only with a microscope. Bacteria and viruses are microorganisms. They are also called microbes.

Q: Are there other types of infection-causing microorganisms?2

A: Yes, fungi (plural of fungus), which are microscopic plants, and protozoa, which are microscopic single-celled organisms. If you bake bread, you probably use yeast—that's a fungus. If you've ever had athlete's foot, you can blame it on a fungus, tinea pedis. If you travel abroad, you probably know about the protozoa, Plasmodium falciparum, which causes malaria in people who are bitten by an Anopheles mosquito, the species that transmits the disease.

Q: What do bacteria look like?2

A: Bacteria consist of only one cell, but they exist in colonies containing numerous bacterial cells. They reproduce by growing and then dividing into two. Bacteria are in three shapes: balls (“cocci”; for example, Streptococci, the cause of strep throat), rods (“bacilli,” such as Escherichia coli, a common cause of urinary infections), and spirals (for example, spirochetes, most notably Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease).

Q: What do viruses look like?1,2

A: Viruses are much smaller than bacteria. They're not even cells. They consist of molecules of DNA or RNA, which contain the virus' genetic code, all held together by a thin coating of protein. Most viruses are shaped like rods or spheres. They can't divide and reproduce. Instead, viruses act by getting inside the normal cells in the body and taking them over. Then the DNA or RNA of the virus causes the host cell to make copies of the virus. You've probably heard of the influenza virus, which causes flu, and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, and almost everyone is personally familiar with rhinoviruses, which cause the common cold.

Q: What's more dangerous, bacteria or viruses?1

A: Although both bacteria and viruses can be deadly, serious viral infections are more dangerous because they're more difficult to treat. Most—but not all—bacterial infections can be cured by readily available bacteria-killing drugs (antibiotics) that travel in the bloodstream to reach the infected areas. (In Chapter 3, you'll read about some bacteria that are especially deadly because they are resistant to antibiotics.) In contrast, viruses live inside cells, so it's hard for drugs to reach them. That's why it's been so difficult for scientists to develop effective antiviral medicines. Fortunately, vaccines are available to prevent some, but not all, viral diseases. For example, people with AIDS, caused by the HIV, must take many powerful drugs to control their disease. But as yet, medication has not been able to cure the disease, and no effective vaccines have been developed to prevent it.1

Q: Can antibiotics help people with AIDS and other virus infections?

A: Remember, viruses live inside your cells, where antibiotics can't get to them. So an illness caused by a virus absolutely should not be treated with antibiotics. However, many people with AIDS and other severe viral illnesses often develop concurrent (that is, developing at the same time) bacterial infections that antibiotics can help to control.1

Q: Then why do doctors sometimes prescribe antibiotics for people who just have a bad cough or cold?

A: Most doctors know that they shouldn't prescribe antibiotics for otherwise healthy people who have a new-onset (“acute”) cold, bronchitis, or sinusitis (an “upper respiratory tract infection”). That's different from a long-term (chronic) infection. But even when doctors explain that antibiotics won't help some infections, patients often pressure them to prescribe antibiotics, and doctors give in to keep patients happy. Studies show that concurrent bacterial infections occur in only a very small proportion of people who develop acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. So skip the antibiotics when you have a cold, unless you have related medical problems.3

Antibiotics

Antibiotics don't work against viral infections.

A cold is a viral infection, so don't ask your doctor to prescribe an antibiotic when you have a cold.

YOU'VE BEEN COLONIZED!

In earlier times when explorers arrived on distant shores, they often faced challenges such as harsh climate, illness, or famine. But explorers can be a hardy bunch, and soon their colonies started growing and expanding. Bacterial infections actually start in a similar way.

The first stage of infection is called colonization, during which bacteria find a way into the body (a “portal of entry”) and attach themselves to cells (for example, the skin cells around your cut) or to tissues (such as the urinary tract, the digestive tract, or the respiratory tract). If the initial barrage of infection-fighting leukocytes doesn't kill the first bacterial “settlers,” they continue to grow and multiply into increasingly larger colonies.6 The time taken is called the incubation period.

Depending on the type of bacteria and the area that's colonized, it could take days, weeks, or even months before the spreading infection causes any symptoms. With your cut, you had classic symptoms of inflammation: redness, heat, swelling, and pain. Other types of infection could cause fever, nausea, muscle aches, sneezing, or coughing, to name just a few possible symptoms.

At the point when symptoms appear, you no longer have a simple infection; you now have an infectious disease that could possibly spread to other areas of your body. It's definitely time to see a doctor for an examination, perhaps some tests, and most likely, an antibiotic prescription.

It's Greek—or Latin—to Me!7

Trying to wrap your tongue around the names of bacteria and viruses can be a challenge. Understanding the names is even more difficult. After all, most of them come from Greek and Latin words and from personal names of people who first identified the pathogens.

The following clues should help:

- Most names have two parts: a genus (the kind of pathogen) and a species (appearance) name. For example, Escherichia coli (better known as E. coli). The term Escherichia honors Theodor Escherich, who identified this bacterium. Coli comes from colon, the large intestine; coli means “of the colon.”

- Some names are formed by combining two or more Latin or Greek words into one compound name. For example, Rhodospirillum rubrum. Rhodo is derived from the Greek word rhodun meaning rose; spirillum is from the Greek word spira meaning spiral; and rubrum is Latin word meaning red.

- Why are all the names of bacteria printed in italics, but not all virus names? Well…that's just the way it's always been done.8

WHY ME?

You eat nutritious foods. You do plenty of exercise. You sleep well. You are the picture of good health. So why did you suddenly get an infection from a simple cut? As Shakespeare might have answered, “Let me count the ways!” There are plenty!1,9

- First, you have to encounter a pathogen. The most common way that happens is through your skin, when someone touches you or you touch someone or something, and bacteria is passed on to you. Before you have a chance to wash off the bacteria, you may touch your mouth, nose, or eyes, which provides an entry point for the bacteria.

- Maybe someone standing close to you coughs or sneezes and bacteria fly directly into your eyes, nose, or mouth, or onto your hands.

- Do you have a new love interest? More than 500 kinds of bacteria live in people's mouths. Perhaps one of them got passed along while you were kissing. During sexual intercourse, you may have been exposed to the herpes simplex virus (herpes type 1 causes mouth sores and herpes type 2 causes genital sores). If you had unprotected sex, there's also a risk of transmission of gonorrhea bacteria or HIV.

Clean Your Hands!

Your mouth, nose, and eyes are good entry point for bacteria to get into your body. That's why you need to wash or sanitize your hands often.

If bacteria get on your hands—as often happens—and you don't wash them, guess where those bacteria end up when you put your fingers in your mouth, or touch your nose, or rub your eyes? They end up in your respiratory system, your circulatory system, and internal organs very quickly!

- Perhaps you didn't keep your hamburger on the barbecue grill long enough to kill harmful bacteria. Several hours after eating, you started to feel nauseated.

- Another possibility is you're visiting a friend in a city far from home or you're sightseeing in a foreign country. Although you've developed immunity to many pathogens common in your geographic area, you're now exposed to new pathogens to which you're more susceptible.

- Did you consider the season or the altitude? Some bacteria and viruses thrive in certain climates and locations. That could increase your risk of infection.

- Were you hiking in the woods? Check yourself for ticks. A tiny deer tick can transmit bacteria causing Lyme disease. Mosquitoes can also transmit pathogens.

- What about emotional factors? Are you under stress at work? Did a good friend die recently? Are you feeling depressed? Stress and emotional upsets can lower your immunity.

THE DOCTOR WILL SEE YOU NOW9,10

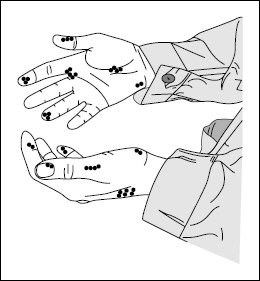

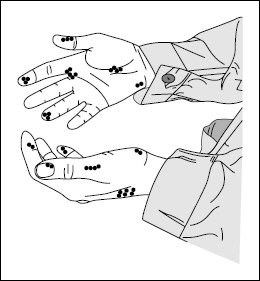

One more thing. Didn't you have a doctor's appointment last week for your yearly physical examination? Doctors' offices are loaded with bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens because so many sick people are there spreading their germs around. Not to mention germs on the doctor's examining table, the stethoscope, thermometer, blood pressure cuff, and other equipment, and on the doctor, too. The longer you stayed in the office waiting room—and possibly reading old magazines that have passed through many patients' hands—the greater was your risk of picking up an infection. Look at the doctor's hands below and on the next page and you'll see what I mean.

If a doctor's office presents so many infection risks, just imagine what might happen in a hospital. You'll find out in the next chapter, but first read Deborah Shaw's story about what actually did happen to her father when he developed a healthcare-associated infection.

Deborah Shaw's Story: The Last 3½ Days in the Life of My Father, Gene Shaw

I wish I had known what to do to save my father. He was admitted to the hospital on midday Wednesday, November 10, 2004, suffering from a severe blood infection (sepsis) that was due to leukemia. Less than 24 hours later, after being given intravenous antibiotics and a blood transfusion, he was walking around again, joking, and entertaining visitors.

However, by Friday, he was noticeably tired and coughing. Doctors were not alarmed by his cough. I was. By 7 p.m. that night my father was also alarmed, because he knew what it felt like to have pneumonia—he had a bout of it that spring. Also, along with his bad cough, he had pain in his shoulder blade. That often occurs from a lung infection.

We had the nurse contact the on-call doctor repeatedly, but the doctor refused to come in to the hospital. By 2:30 a.m. Saturday morning, I had given up, after pleading, threatening, and cajoling the Nursing Supervisor. Nothing helped. We were watching my father die.

Finally, the regular doctors and nurses came in on Monday, but they could not work fast enough to reverse the damage that occurred over the weekend. My father, just barely 73 years old, was dead by 1 p.m. Tuesday, only 3½ days after our first plea for help, 2½ days of which we relied on weekend and night-shift personnel. Those doctors, nurses, and the hospital had completely failed us.

Some healthcare-associated infections are not preventable, even when the hospital staff and family members do everything possible. Mr. Shaw's leukemia weakened his fighting cells, so bacteria in his blood weren't killed and continued to multiply—that's what sepsis means. Sepsis is very difficult to treat. The death rate is very high, especially when the patient's disease-fighting cells aren't helping, as happened with Mr. Shaw. When the bacteria spread to his lungs, he developed the pneumonia that caused his death.

Was the hospital responsible for Mr. Shaw's infection? Did they do everything to prevent his death? You might argue that they did fail him by not responding over the weekend in a timely manner. But you can also argue that his immune system just could not provide support for him to survive, even if the staff had responded earlier.

So what could Deborah Shaw have done differently? In Chapter 5, you will learn what your rights are as a patient or as someone helping a patient (an advocate) and how to take matters such as this into your own hands. For example, you or your advocate can request what's known as a “rapid response call,” which immediately summons a Medical Emergency Team of critical care doctors to the patient's bedside. Most patients don't know about this, but now you do. It is your right to request a rapid response, when necessary.

Although the outcome may not have been different for Mr. Shaw even if Deborah had known this technique, at least the guilt of not knowing how to get help or to be heard would not be part of her grieving process.

Doctor's hands showing germ areas (black dots).

(WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare.10)

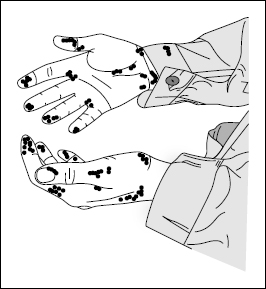

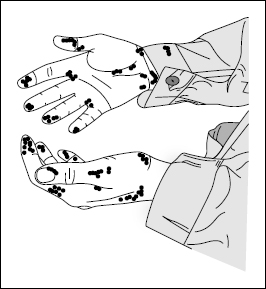

Same doctor's hands showing how bacterial contamination increases with time during patient contact.

(WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare.10)