Attack of the Super Bugs!

Horror stories always get people's attention. Who could resist reading sensational news reports like “Invasion of the Super Bugs—Antibiotics Don't Help!” Pretty scary, right? Unfortunately, it's true. New strains of bacteria that ordinary antibiotics can't kill are spreading rapidly throughout the world, leaving critically ill and dying people in their wake. Like Superman, these “super bugs” often seem to be invulnerable. That's why medical researchers are urgently searching for the equivalent of Kryptonite to stop super bugs in their tracks.

What happened to create these super bugs? Where are they found? How can I avoid them? Keep reading for more on the latest developments.

WHAT'S A SUPER BUG?

Doctors have a wide assortment of antibiotic drugs that they can use to treat people who develop infections. But sometimes an antibiotic that has always worked for a certain type of bacterial infection suddenly stops working in patient after patient. That means the bacteria have changed (“mutated”) in some way that makes them resistant to the antibiotic. This problem is known as antibiotic resistance. Usually—but not always—switching to another antibiotic will help to cure the infection.

Not all antibiotic-resistant bacteria are super bugs. Bacteria that rate this title are resistant not just to one or two antibiotics, but to almost every strong antibiotic currently available, including methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin, and amoxicillin.1 That leaves doctors with only one or two super powerful antibiotics to try. Even when those antibiotics work, it can take weeks or months to produce any improvement, during which time super bugs often cause major complications or even death.

What's an Antibiotic?

Antibiotics are drugs that kill or limit the growth of infection-causing bacteria. Before antibiotics were developed, people very often died from infections. When penicillin, the first antibiotic, became available commercially in 1938, people called it a wonder drug because now infections could be cured. Since then, medical researchers have developed many other antibiotic drugs.

It's important to have a wide variety of antibiotics because some types of antibiotics are more effective against certain types of bacteria. Your doctor must determine what type of bacteria you have to prescribe an antibiotic that will be most effective.

Unlike antiseptics that kill germs on cups, glasses, doorknobs, and other surfaces (including your skin), antibiotics kill germs that live in your bloodstream. Antiseptics can be used frequently, but antibiotics are very powerful drugs that should be used only when absolutely necessary.

Antibiotics still save many lives, but overuse of antibiotics is costing some lives. That's mostly because antibiotics have been prescribed too frequently over time. For years, doctors prescribed penicillin for common ailments—sore throats, chest colds, and coughs—even though antibiotics don't work for these virus infections. Doctors know better now, but people who are sick enough to visit a doctor often demand “something” to help them feel better fast. If that something is an unneeded antibiotic, taking it may have the unfortunate result that bacteria in your body will develop resistance to the effects of that antibiotic. Then if you get an infection that really does require antibiotic treatment, you may find that the drug won't work for you anymore. I hope it won't be a super bug infection.

Antibiotics Don't Work for a Cold

Did you know that antibiotics don't work to cure the common cold? That's because colds are caused by viruses not by bacteria. Antibiotics don't kill viruses. Doctors know this, but sometimes they give in when sneezing patients demand a prescription for antibiotics because “maybe there's a chance it will help.” Please don't take that foolish chance!

MEET THE SUPER BUGS

The following are the three most common super bugs:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE)

- Clostridium difficile (“C. diff”)

MRSA was the first super bug infection to make news headlines. Back in the 1970s, doctors were alarmed to encounter patients dying from seemingly ordinary “Staph” infections that couldn't be controlled with any of the penicillin-like antibiotics known as beta-lactams, including penicillin, amoxicillin, oxacillin, methicillin, and others.2

MRSA is an especially dangerous category of Staph, not just because of antibiotic resistance but because MRSA can spread rapidly throughout the body, causing life-threatening harm to numerous organs.3 Antibiotics such as vancomycin and rifampin often work to control MRSA in hospitalized patients.4 When other antibiotics fail to work, newer antibiotics such as linezolid, daptomycin, and tigecycline are now being used for MRSA.5

Almost everyone has S. aureus on their skin and in their nostrils. Although it usually isn't harmful, Staph can cause common skin infections such as boils and abscesses that are easy to treat.6 But especially in hospitalized patients who have had surgery or medical procedures, Staph can lead to potentially fatal antibiotic-resistant infections in surgical incisions, heart valves, and places where tubes have been inserted into the body.

Serious antibiotic-resistant Staph infections are also on the increase in healthy, nonhospitalized people—especially children and sometimes with fatal results.7 Young athletes such as football players and wrestlers can also contract MRSA from close skin-to-skin contact with other athletes who don't realize that pimples or boils on their skin are infected with Staph.8

VRE, the second super bug, was initially detected in the late 1980s. Because many types of Staph bacteria had become resistant to methicillin, doctors increased their use of a different type of antibiotic, vancomycin. Unfortunately, bacterial resistance to vancomycin soon developed, this time in enterococci bacteria such as Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis, which are commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract and, in women, the genital tract.9 Soon some Staph bacteria also developed vancomycin resistance.

Enterococci usually cause little problem in healthy people. But as with MRSA, hospitalized patients are more susceptible to the VRE super bug. Despite the risk of resistance, intravenously administered vancomycin is still the most useful antibiotic for many of these infections. However, even when the drug works initially, enterococci bacteria may develop vancomycin resistance during treatment.10

C. diff is another common type of bacteria that we all have in our intestinal tract. C. diff usually lives peacefully along with many good intestinal bacteria that stimulate the immune system and help to control harmful bacteria. When you take an antibiotic to kill bacteria that are causing an infection, sometimes these good bacteria are killed along with the bad ones. Without good bacteria to control it, C. diff quickly multiplies, releasing harmful substances called toxins.11 This leads to production of cells that eat away the lining of the colon, causing severe diarrhea and colitis (inflammation of the colon).12

People infected with C. diff excrete spores containing the bacteria in their feces. Hand sanitizers don't kill these spores, so frequent handwashing is the best protection against spread of C. diff. It's also important to thoroughly clean all surfaces in an infected patient's room, because any surface that comes in contact with even a tiny spot of fecal matter can provide a way for C. diff spores to be transferred to people who touch that surface.13 Another way to prevent contact with fecal spores is using disposable rectal thermometers for infected patients, rather than the electronic thermometers that are reused for many patients.14

Studies show that 90 percent of C. diff infections occur in people who recently took antibiotics for non-C. diff infections. Elderly hospitalized patients are the most frequent victims.15 For people who develop C. diff infections while they're taking antibiotics for a non-C. diff infection, stopping antibiotic treatment frequently helps to cure the C. diff infection.

Many C. diff infections can be treated with the antibiotics such as metronidazole or vancomycin, but C. diff resistance is rapidly increasing.16 This qualifies C. diff for super bug status.

Q: Why do we call these bacteria super bugs?

A: They're called super bugs primarily because the media gave them that name. But their super strength in resisting strong antibiotics definitely merits the super bug title.

Q: There are lots of different antibiotics. Why can't doctors find some that work against super bugs?

A: Although their names might suggest that they are resistant to only one antibiotic—for example, methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant (VRE)—these super bugs are resistant to most antibiotics. At first, doctors feared that they had run out of antibiotics to try. Today, thanks to recently developed drugs, we do have some added antibiotic options. Because of this, super bugs are now commonly referred to as “multidrug-resistant pathogens” (MDRPs).

Q: Does that mean super bug infections are curable now?

A: Infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria produce the same kind of symptoms as do easily treatable infections with other bacteria. The difference is that doctors have markedly fewer antibiotic choices for fighting these super bugs. Even when one of the newer antibiotics seems to work, the super bug may soon develop resistance to it, giving time to the infection to spread and cause damage. There are many successful cures, but also many uncontrollable super bug infections that end in death.

Q: Why do super bugs become resistant to antibiotics?

A: Bacteria can change in several ways that reduce or totally eliminate their susceptibility to antibiotics. One way is a genetic “accident” (a mutation), similar to what causes some babies to be born with an abnormal heart or even six fingers on each hand. For bacteria, gene mutations can make the mutant bacteria unusually resistant to antibiotics.

Another cause of bacterial resistance is more common than mutations. Consider this: What if you take an antibiotic to treat an MRSA infection and it kills all of the dangerous bacteria, except for one single bacterium (bacterium is the singular form of bacteria). That one super-strong bacterium survives and multiplies, making more super-strong bacteria. All of the weaker bacteria have been killed, but now you have many, many super-strong bacteria that are likely to be resistant to the original antibiotic (and to other antibiotics as well).

SUPER BUGS LOVE HOSPITALS

Remember the old joke about banks:

Harry: “Why do people rob banks?”

Larry: “Because that's where the money is.”

It's the same for super bugs. Why do hospitals have so many super bugs? Because that's where the sick people with infections are.

There are three reasons why MRSA, VRE, and C. diff have made hospitals their favorite home:

- A majority of hospitalized patients are given antibiotics, which increases the chance that “good” bacteria will be killed, while “bad” bacteria like C. difficile will survive and be passed on to other patients.

- People who are sick enough to need hospitalization often have weakened immune systems that can't fight infections, so they're more likely to catch any super bug that comes their way.

- Many healthcare workers don't wash their hands well enough or often enough. That means super bugs living anywhere in a hospital may be quickly transmitted from patient to patient, either on healthcare workers' hands or patients' bed rails, other surfaces in the patients' rooms, food trays, medical equipment, and more.

Studies show that transmission of MRSA, VRE, and C. difficile from one patient to another occurs mostly via the hands of healthcare workers. I have conducted observational studies of handwashing in numerous hospitals around the country, so I know for sure that healthcare workers wash or sanitize their hands less than 50 percent of the time.

ARE THERE ANY SAFE HOSPITALS?

When hospitals hire me to help improve their infection control, I always focus on ways to ensure that all healthcare workers and patients consistently wash and disinfect their hands. That can make a big difference!

But I know it's impossible to completely prevent super bug infections, especially in larger hospitals and in intensive care units (ICUs) where a high percentage of patients are gravely ill or very elderly. You may hear that you have a lower risk of super bug infections at most smaller hospitals and children's hospitals where patients are less likely to be severely ill, there's no guarantee. But keep in mind that the number of super bug infections is increasing, so hospital size may not be as important as we once believed. That's the reason you need to be on your guard to make sure healthcare workers wash their hands.

The TV Camera Was on But They Still Didn't Wash!

When I first began doing research and published my first article, many TV stations wanted to interview me about my method of having patients remind healthcare workers to wash their hands. I learned very quickly that the media usually adds a “twist” to the story, in addition to the ordinary facts.

So there I was in an intensive care unit with a national TV reporter questioning me about my research. Toward the end of the interview, he asked me to demonstrate the correct way people should wash their hands, while he continued to comment. An important note: I was amazed that the reporter made it very clear to me that he needed to stand on a certain side of the sink, because he wanted to be filmed only on his “good side.” That did seem a little strange, but I still thought the interview went well.

On the night the report was scheduled for broadcast, I gathered my family around the TV with me to view my 15 minutes of fame. To my surprise, as soon as I began speaking to the reporter, two round clicking clocks appeared on the screen above me. One clock was set for 15 seconds, which is the recommended amount of time people need to wash their hands. The other clock started ticking whenever the screen showed a healthcare worker either begin to wash her hands or fail to wash in a situation where she should have. Yes, unbeknownst to me, someone from the TV station had used a hidden camera to record what all the ICU healthcare workers were doing.

You could say it's wrong not to disclose this secret filming, and that would be valid. But the real issue is that everyone taking care of the patients in the ICU could see that a TV reporter was filming an interview about hand hygiene. You might think everyone would be sure to do the correct thing. Well, much to our embarrassment, the film showed that in addition to those who did not wash at all, most healthcare workers who did wash their hands never did it for the full 15 seconds.

THE BUGS KEEP SPREADING

Cases of multidrug-resistant infection are steadily increasing everywhere in the United States and around the world, so it's hard for patients in any hospital to avoid exposure to super bugs. For example, in the early 1990s, there was only a 20–25 percent chance that a healthcare-associated Staphylococcus infection would be methicillin resistant. Today, there's a 60 percent chance that a similar Staph infection would be resistant. The most recent statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that 94,380 patients developed invasive MRSA infections in the United Sates in 2005; 18,850 of these patients died.17

Increasing outbreaks have also occurred with VRE infections, which have gone from a less than 1 percent chance of being antibiotic resistant in 1997 to an almost 30 percent chance in 2003. And for C. diff, the numbers have doubled from about 40 cases per 100,000 patients in the U.S. population in the 1990s to 84 cases per 100,000 in 2005. A study in England reported C. diff infection as the primary cause of death for 499 people in 1999, rising to 3,393 in 2006.18

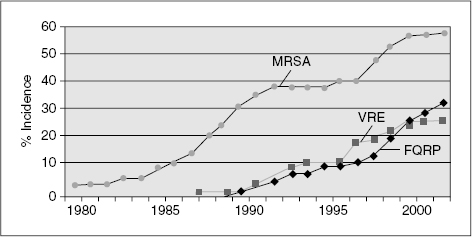

MRSA, VRE, and C. diff are the most common super bugs. They're the ones you're most likely to hear about on TV and read about in newspapers and on the Internet. But these days, almost every month brings a report of new antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Look at the chart on page 33, which shows the steady increase in MRSA and VRE infections. You'll also notice a new super bug category, Pseudomonas, which first showed up around 1989. More recently in 2009, doctors reported a newer antibiotic-resistant bug, New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, named after the city in which a Swedish tourist contracted the first case.19 As this indicates, infections are moving from country to country, so don't be surprised if next week's news headlines include yet another new super bug warning.

This chart shows the increase in rates of resistance for three bacteria that are of concern to public health officials; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (FQRP). These data were collected from hospital intensive care units that participate in the National Nosocomial Infections Surveilance System, a component of the CDC. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Q: Are some patients more likely to get an infection with multidrug-resistant bacteria?

A: Yes, super bug infections occur more often in people whose immune system defenses are weakened due to AIDS, cancer chemotherapy, recent surgery, and other medical conditions. Risk of infection is also higher for people using urinary catheters or ventilators and for those who have longer hospitalizations or require treatment in an intensive care unit.

Q: Why is there a high risk of infection in an intensive care unit? Aren't doctors and nurses especially careful there?

A: Patients in the ICU are very sick, which means they're more likely to have been infected with resistant bacteria before they went into the ICU. The more patients in the ICU at one time, the greater is the risk that an infected person's bacteria will be transmitted to other ICU patients. Although the sickest patients are in the ICU, multidrug-resistant bacteria are currently found in increasing numbers in non-ICU patients.

Q: Don't hospitals know which patients are infected, so those patients can be kept away from others?

A: Many people are colonized with bacteria on their skin or in their body, even if those bacteria haven't caused an infection yet. Although there are no signs of infection, people who are colonized can still transmit the bacteria to others. There lies the problem that prevents hospitals from finding out which patients are infected at the time they're admitted to the hospital.

Pennsylvania and a few other states have passed laws that require all patients to have bacterial cultures performed when they're admitted to the hospital as a check for multidrug-resistant infections. This makes it easier to take precautions that may decrease the risk of other patients becoming infected. Several studies in Europe, particularly research done in the Netherlands, have shown that this “search and destroy” approach can significantly decrease the incidence of super bug infections.20

Before you are admitted to a hospital, find out whether bacterial cultures are routinely performed on admission. If not, the most important thing you can do is to insist that doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers always wash or sanitize their hands before and after they have contact with you.

HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF IN THE HOSPITAL

It's frightening to think of everything that can go wrong when you are hospitalized. The purpose of this book is not to scare you, but instead to help you to protect yourself from infections and treatment errors, so you won't feel so frightened. There's nothing complicated about it, honestly! Here are some simple tips to remember:

- First, and most important, I'll repeat: Ask all healthcare workers to wash or sanitize their hands before they have contact with you.

- Make sure you practice what we call interventional patient hygiene, a fancy way to define bathing. This means that you control the bacteria that are on your skin by keeping your body clean. You decrease the possibility of super bugs getting into your system at the site of your surgical incision, or during insertion of an intravenous line, or when you are touched by healthcare workers, or when you come in contact with objects in your hospital room.

- Take precautions at bath time. Make sure you have a bath each day using prepackaged towels, preferably ones that have been treated with chlorhexidine to kill bacteria. Hospitals should provide these for you. Do not allow yourself to be washed using a basin and towels. Basin water can be a source of bacteria. If you're told the safer technique isn't used, refuse the bath and ask a friend or family member to bring you a supply of pre- packaged towels and help you with bathing.

- Finally, if you are in the Intensive Care Unit, or if you are unable to help yourself after surgery, be sure to have a family member or friend with you to act as an “advocate” who will request the care and precautions you need.

As you've read, there are numerous ways that improper use of antibiotics can contribute to a continued increase in the creation of super bugs. But you, the patient, can help to break this chain of transmission.

Q: Many people are routinely given antibiotics before or after surgery to prevent infections. Is this safe? Or is it dangerous overuse of antibiotics that could create resistant bacteria?

A: If your doctor says you need antibiotics before surgery (this is called surgical prophylaxis), the first thing you should do is to ask21:

- Is there any another treatment option instead of antibiotic use?

- Is presurgery antibiotic treatment the proven approach to preventing infections for the kind of surgery I'm having?

- Are you using an antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum for this purpose? That means choosing a drug that kills only the bacteria that are expected to be present and not a drug that kills a large selection of bacteria. Limiting the targets limits the risk of creating antibiotic resistance.

- When will the antibiotic be administered? Antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis usually should not be given for more than 24 hours. In most cases, postoperative doses are not required.

- Remember if you do not get answers or are told don't worry, find another surgeon.

Q: What should be done if I get an infection during my hospitalization?

A: First, doctors should be sure that it's a bacterial infection and not a viral or fungal infection before any antibiodics are given to you. Viral illnesses such as acute bronchitis should never be treated with antibiotics. Here's what to look for17:

- The key is to identify the pathogen—that is, for the doctor to take a tissue or fluid sample and send it to the laboratory for a culture that will reveal what kind of bacteria are present and which antibiotics they are most susceptible to.

- If your symptoms are easily identified as a bacterial infection, your doctor may decide to start antibiotic treatment before culture results are in. This is known as empiric therapy. It's important to receive empiric therapy that targets the pathogens that have been detected recently in your hospital and in the local area, or are the most frequently found bacteria for the body site of your surgery. Most hospitals have a “local biogram” that provides this information.

- When culture results come in, the empiric antibiotic should be replaced, if necessary, with the antibiotic that best matches your antimicrobial susceptibility test results. The doctor should select an antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum for the type of bacteria that was identified. This is known as definitive therapy.

While you're still hospitalized, be sure the antibiotic is given to you as often as the doctor has directed. If you know you should be taking a pill twice a day, and the nurse has not arrived with one of your doses, let the nurses know and have them check your chart to see when the last pill was administered. You must complete the recommended days of treatment. Do not skip a dosage or stop taking the antibiotic, even if you feel better. That can lead to growth of resistant bacteria.

Q. When should antibiotic treatment be stopped?17

A: If cultures that were taken when you were showing signs of infection come back negative and your symptoms suggest that infection is unlikely. When you have finished the antibiotic treatment and the infection is considered cured.

Take Your Antibiotic as Directed!

DO take your antibiotic as directed

DO finish all of your antibiotic

DO NOT skip a dose of your antibiotic

DO NOT take antibiotics for viral infections

DO NOT save your antibiotics for another time

DO NOT take another person's antibiotics

Q: What should I do if my infection symptoms get worse, despite antibiotic treatment?

A: Ask your doctor to consult with an infectious diseases expert. If there are no experts in your hospital, ask your doctors to arrange for an outside consult. If he/she refuses this would be a time for you or your advocate to request a rapid response as discussed in Chapter 1. You could have an antibiotic-resistant infection, so getting expert advice on which antibiotic or other treatment to use could save you from major complications or even death.

Q: What should I do if I think I'm developing an infection after I'm home from the hospital?

A: As you've read before, bacterial colonization can take considerable time to turn into actual infection. With super bugs, symptoms of infection typically develop while a patient is still hospitalized. But in some cases, symptoms may appear weeks or even months after hospitalization. If that happens to you, be sure to tell your doctor that you have been hospitalized recently and whether you have received antibiotic therapy.

Q: What infection symptoms should I look for?

A: Whether you're in the hospital or back at home, you could have an infection if you're experiencing chills or fever, unexpected pain, drainage or pus oozing from a wound site, or increased inflammation of a surgical incision. If any of these symptoms occur, call your doctor immediately, especially if you have recently been discharged from a hospital.

WHEN MRSA STRIKES

This chapter is full of facts about dangerous super bug infections. To me, what really brings these facts to life are the many stories I hear from people who have generously shared their stories like Carrie Simon who has “been there” and lived to tell the tale. Here's the story in Carrie's own words:

Why didn't anyone tell me about MRSA? My name is Carrie Simon. I had never heard of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) before I was infected with it. This is quite surprising, because I have been in and out of hospitals for most of my adult life. My story begins when I was 17 and was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease, cancer of the lymphatic system (a rare lymphoma). That was 33 years ago. Here I am today: a wife, a mother of three teenage daughters, and a teacher. And on top of that, I am actively involved in my continuing survival!

The long-term effects of radiation treatment have given me severe medical problems, including cardiac disease that affects the valves of my heart … I was under the care of experts in the long-term effects of cancer survivorship … who put me in contact with a cardiologist at a large academic medical center in a major city. I felt very good about the care that I would receive.

After listening to that doctor's best advice, I underwent an aortic valve replacement and tricuspid and mitral valve repairs. As we all expected, the surgery went very well, but a few days later … my pain gradually began to increase instead of decrease. Neither the nursing staff nor the resident physicians recognized the significance of my symptoms. Only after about 36 hours of an unexplainable deterioration in my condition, and the onset of near-fatal atrial fibrillation, did the hospital staff respond appropriately…. I was rushed from the step-down unit back to the intensive care unit.

I clearly remember the painful day when the infectious disease doctor told me that he thought I had contracted a life-threatening antibiotic-resistant MRSA infection that was ravaging my body…. As a result, I underwent five additional surgeries during which a cardiac surgeon debrided my sternum (that is, scraped away infected tissue from my breastbone) and disinfected my chest wound.

I remained hospitalized for more than 2 months. During that time, I sank into a deep depression. My family arranged for a psychiatrist to visit me each day, but nothing could change the reality of my situation. My oldest daughter was in her first year of college in New York, my other two children were in school in Connecticut, and I was in a hospital in Boston. My children were terrified, and I was helpless.

We did not know whether treatment with intravenous vancomycin (an antibiotic) would work. I vomited from that therapy every day. In addition, I experienced drainage complications as result of the current surgeries and past radiation therapy, so the days just dragged on.

My family and friends helped me through this crisis. All the while I was in Boston, I was never alone. My husband, parents, cousin, and friends were there with me. They were my constant companions, but more importantly, they were my advocates. Thrust into a life-threatening challenge, my husband began to research this “mysterious” infectious disease. Many of the hospital physicians were loathe to communicate about it with me, but it was obvious that I was not the only patient with an MRSA infection in the cardiac intensive care unit.

As a practicing attorney, my husband used his research skills to learn all he could about MRSA and how it had quietly developed into an epidemic problem in U.S. hospitals. How could this infection, which was affecting so many cardiac patients at a nationally recognized teaching hospital, not have been the subject of our preoperative discussions? How could the medical staff, including highly acclaimed cardiac fellows, have been so unaware of the obvious signs of that infection that developed? Those questions undermined our confidence in a hospital that we had carefully chosen as the place to minimize the risks that surgery entailed for me as a Hodgkin's disease survivor.

After I had been hospitalized for 9 weeks, my condition had improved. Although my doctors did not think that I was ready to leave, I could not stand it there any longer. I was still depressed, and I was unable to eat because of nausea caused by the antibiotic therapy. I insisted that I be allowed to go home.

After I returned home, my emotional state gradually improved, and I began to eat again. I received medical care from visiting nurses, and my husband was in charge of administering 6 additional weeks of intravenous vancomycin. My health gradually improved, too, but the emotional scars have taken their toll on my family, my friends, and me.

As a Hodgkin's disease survivor, I know that I will need to be hospitalized from time to time to deal with the long-term effects of my illness. Since my cardiac surgery and the subsequent MRSA complications that I experienced 2 years ago, I have been hospitalized 4 times: once for breast cancer, twice for unexplained bleeding in my gastrointestinal system, and once to have a pacemaker implanted. Each time I entered the hospital, I was terrified that I would contract a MRSA infection again. Thankfully, I was fortunate each of those times.

Carrie Simon's memorable story paints a vivid picture of how devastating super bug infections can be. But on the positive side, she also reveals how a patient and family and friends can play an active part in demanding the attention and care that's vitally needed. The checklist at the end of the chapter is a quick reminder of easy steps you can take to help yourself or a loved one who is hospitalized.

WE WILL REACH OUR GOAL!

My work over the past 6 years involves collecting data from hospitals across the United States from which I determine their hand hygiene “compliance rate” every month. By compliance, I mean: Do healthcare workers actually wash or sanitize their hands every time hand hygiene is required? The bad news is that the average compliance rate in intensive care units is only 26 percent. In non-ICU units, compliance averages 37 percent. The good news is that when hospitals educate their patients to ask healthcare workers to wash and sanitize their hands, we've found that hand hygiene compliance increases to 37 percent in the ICU and 51 percent in non-ICU units.22 That's still not great, but it's definitely an improvement. The more patients who start asking healthcare professionals to wash their hands, the closer we'll get to our goal of 100 percent hand hygiene compliance.

Did you know that if you are a patient in an intensive care unit, all the healthcare workers involved in your care will have a total of 144 times when they should perform hand hygiene during each 24 hour period? That's 6 times every hour. If you are in a non-ICU room, the total would be 72 times every 24 hours. With so many chances to forget during a busy day caring for patients, it's no wonder that nurses' and doctors' hand hygiene rates are so low.

So if you wind up in a hospital bed, start counting and start asking. Healthcare workers need your help!

Remember, when hospitalized …

- When hospitalized, make sure you have a daily bath.

- Tell all healthcare workers and visitors to wash or sanitize their hands.

- Tell your doctor if you have recently been: hospitalized, admitted to a nursing home, exposed to or treated for MRSA, or currently have an infection (for example, urinary tract).

- Identify an advocate and understand the use of “rapid response.”

- Discuss informed consent and ask your surgeon about infection rates and antibiotics.

- Check your skin around an IV for any redness or swelling.

- Urinary catheters should only be used when necessary, not for convenience.

- After discharge, check your wound site for any redness, swelling, or drainage, if you have pain.

© MMI, Inc. 2004, Ardmore, PA; www.hhreports.com