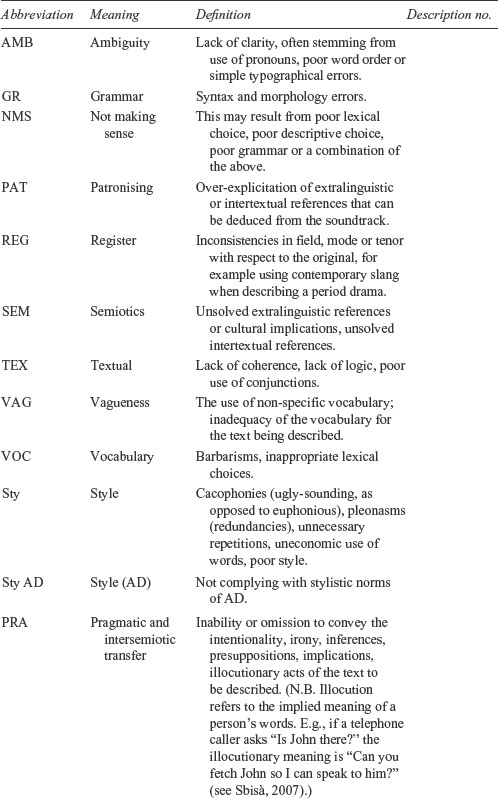

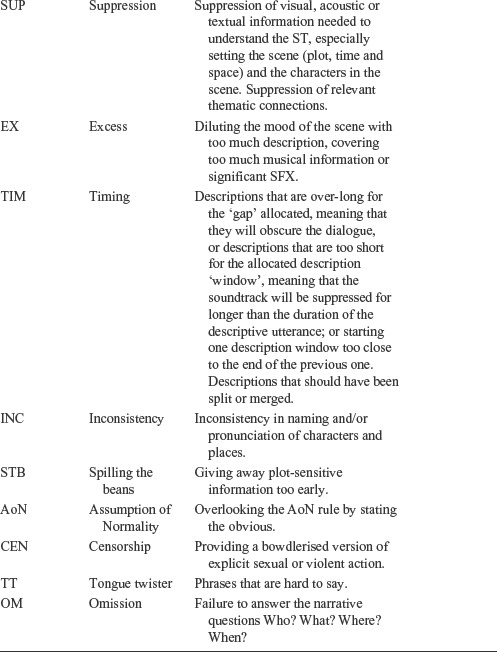

Table 6.1 Marking checklist

This chapter is more didactic as the book moves away from the theoretical and towards the practical. Having discussed what to say and the words with which you say it, the chapter looks at ways to create your script both for screen AD and for live settings such as theatre. In a commercial setting, recording is expensive. It is cheaper to spend time ensuring that the script is accurate, well presented and easy to read to than to risk necessitating retakes. In live scenarios where there is no possibility of retakes, a clear and easy-to-read script is arguably more important. Common scripting errors are listed in section 6.4, giving you a framework against which to check scripts. The process of script development is outlined for both live and recorded AD as is the process followed by an AD user who is attending a live performance.

Commercial AD units create script templates using bespoke software, currently available from two main providers: Starfish Technologies and Softel (Swift Adept). Licences for both packages can be expensive, but there is also freely accessible software such as LiveDescribe and YouDescribe that can be downloaded from the internet (see 6.2.4).

The software programs may vary in specifics, but tend to work along similar lines. The scripting software has a dedicated window allowing you to view the source programme at the same time as the window in which you write your script. Using timecode, you create a new scripting ‘box’ within the scripting ‘window’ for each AD utterance that you are about to write. All the elements can be moved around your desktop and resized as you wish. It can be a good idea to full-screen the source programme the first time you watch, so that you do not overlook any fine details. Near the viewing window the timecode is prominently displayed in hours: minutes: seconds: frames. Hitting a specific function key as the video runs will automatically open a new scripting ‘box’ capturing the timecode at that instant, which will be displayed in the scripting window. This is your ‘In time’, i.e. when your new AD utterance begins. At this point, one technique is to type what you want to say, then speak it aloud while running the source programme beneath it, checking the accuracy and duration of what you have written. Then hit a specific function key that will capture the ‘Out time’. The ‘Out time’ will also be displayed. Some people prefer to delay the writing part and simply create a skeleton of blank ‘boxes’, creating a new one at each ‘gap’ in the soundtrack ready for the AD script to be added later, once the whole ST has been watched. Precision is needed, although both In and Out times can be amended manually later on, by over-typing or by repeating the ‘enter time In/Out process’. Another key will allow you to advance or rewind the source programme by one or two seconds, to save you having to run through again from the beginning. In the more sophisticated, commercial programs you can also configure the software to select which key to use for this. Hitting the ‘Out time’ will automatically create a new ‘box’ below the first one and in this way your AD script will develop. However, as the new ‘box’ will have an ‘In time’ that has been automatically generated it is unlikely to be in the right place and you will almost certainly need to change it. Pressing the ‘In time’ key again will overwrite the previous ‘In time’. Beware: this is easily done by accident!

The software will also automatically calculate the duration of the ‘window’ or ‘box’ you have created and the duration between this and the previous utterance, and will flag up an error message if you are trying to create two utterances too close together. In the early days, when you are learning description, it is good to take note of the automatic warnings. You can rectify the problem by changing the timecode so as to alter the place where you have inserted your description. Later you may choose to disregard some of the warnings, although this can be dangerous if you are not in a position to understand why you are doing so. The minimum duration between descriptions can also be set in the preferences menu. Usually a minimum of at least one second is recommended, as the software can also fade down the volume level of the source programme, allowing the description to be heard more clearly over the top; two sudden dips close together have the consequence of the background soundtrack disappearing, then popping back up, only to be quickly reduced again, creating a stuttering effect, which is not a pleasant listening experience. The level of the fade dictates the extent to which the soundtrack is suppressed, while the shape of the fade determines whether it is gentle or abrupt, at the beginning and end. The more gentle the fade, the smoother the listening experience will be, but you may prefer an abrupt fade so as to allow a particular sound effect to be heard, especially if your description is ‘tight’, i.e. will only just fit into the time allocated. If necessary you can resolve this by editing your script to make the word use more economical. Where two descriptions are too close together you may want to merge them into a single ‘box’. Usually a combination of keystrokes will achieve this, preserving the In time of the first ‘box’ and the Out time of the second. Alternatively, if you need to hear a bit of dialogue or SFX in the middle of your utterance, you may choose to split your utterance into two separate boxes (again, a function key may split a description into two at the position of your cursor).

You will have gathered by now that timecode plays a critical role in tying your description to the source programme. Ultimately, timecode is used to lock your recorded description to the source programme, so that the AD will always be broadcast in the right place. Occasionally, a broadcaster will re-edit its programme – perhaps to remove a contentious scene or a rude word if a programme is rescheduled to be broadcast before the watershed. In the UK this is set at 9pm. Material deemed to be harmful to children may not be shown before this time, or after 5.30am. Ofcom deems such material to include violence, graphic or distressing imagery and swearing. AD of this content type will be discussed in Chapter 11. It is vital that the programme provider advises the describer of any programme edits, otherwise there will be a danger that all the recorded description that comes after the edit point will come in the wrong place.

The software will also calculate automatically the duration of your description, meaning both what you have written and the duration of your description ‘box’ (the gap between the ‘In time’ and the ‘Out time’). It will alert you if there is a problem, for example if you have written more words than the software calculates will fit in between the two timecodes you have entered, or not enough. Obviously, how much you can fit in will depend on how fast you are speaking. In the preferences section of commercial software packages you can specify your reading speed in words per minute (WPM).

In the next chapter we will see how important it is to be able to vary your pace, so you may need to override the default settings for WPM. Emma Rodero (2012) has explored speech rates in radio news because ‘radio is the art of communicating meaning at first hearing’ (Rodero, 2012: 391). She cites Pimsleur et al. (1977), who recorded a delivery rate of between 160 and 190 WPM for English and French radio news broadcasters, although ‘in Spanish radio news . . . a high speech rate, of around 200 wpm, is used on all national radio stations’ (Rodero, 2012: 393). Studies show that word comprehension by the listener seriously declines only at speeds over 250 WPM (Foulke, 1968). More recently, Uglova and Shevchenko (2005) noted that televised speech in US news programmes is approximately 200 WPM, although, as we have seen, speech comprehension is enhanced by access to the visuals, so radio provides a better analogy. In 2007 Anja Moos and Jürgen Trouvain showed that blind people could comprehend synthesised speech at much faster levels than sighted people, with comprehension declining only above speeds of 17 syllables per second (s/s), as compared with 9 s/s for their sighted peers. Given that there are, on average, 1.5 syllables per word, this equates to 680 WPM for blind people, as compared with 360 WPM for their sighted peers, although the authors point out that ‘It is unclear how temporally compressed natural speech can be understood by the two groups’ (Moos and Trouvain, 2007: 667). Snyder (2005) advises that description should be delivered at 160 WPM. However, there is a danger of speaking too slowly. Rodero points out: ‘A presentation that unfolds at a slow pace can lead to it being difficult to maintain attention effectively (Berlyne, 1960) and can result in weakened comprehension (Mastropieri et al., 1999), because an increase in the flow of information can raise attention and learning (LaBarbera and MacLachlan, 1979).’ Rather than aiming for a specific speed, let your pace be dictated by the pace of the scene you are describing.

It should be obvious that writing too much is a problem: either your description risks being clipped or cut short by the automatic software because the microphone ceases to be live as soon as the ‘Out time’ is reached; or your speech rate will need to be so fast that it becomes incomprehensible. Less obviously, for screen AD it is also problematic to write too little for any given duration. This is because it leads to the volume of the soundtrack being unnecessarily suppressed beyond your descriptive utterance, leading to a frustrating listening experience. This can be corrected if necessary by reducing the ‘Out time’ after the recording. In live AD, you should avoid leaving the microphone ‘open’ when you are not speaking, as it adversely affects the sound in the user’s headset and may pick up extraneous sounds such as coughing or paper rustling. A microphone opened too early is likely to pick up the describer’s in-breath, although the change in ambient sound may have a positive effect of cuing the user to attend to the AD. The describer must speak as soon as the microphone is fully open, if the user is to have that expectation satisfied. A checklist for common recording errors is included below (see section 6.4).

To check whether or not your description will fit within the duration and position you have allocated, commercial software has a ‘rehearse’ mode. This will automatically restart the programme a certain number of seconds before the ‘In time’ and play only that portion of the programme until the entered ‘Out time’. Again, the amount of cue programme you hear (pre-roll) before the ‘In time’ can be set in the preferences window, as can the length of time it continues beyond the ‘Out time’ (post-roll). It may be tempting to make the pre-roll very short, in order to save time. However, the person who will read your script will benefit from hearing a longer passage of cue programme so that they deliver the script with the appropriate pace and inflection. You may need to experiment, but five to ten seconds is probably enough. Rehearse mode also triggers a feature otherwise available only in record mode, namely a visible countdown to the ‘In time’. It is usually both numerical and graphic, showing a green thermometer that shrinks, turning red as the seconds tick away, the ‘In time’ is reached and the microphone (in record mode only) automatically becomes live. The specific description ‘box’ will be highlighted and centred within the script window to help you quickly find the right place in your script. A description ‘box’ that contains a very long utterance is likely to hide some of the text, requiring you to scroll down within it. If this is the case, split the box into two or more as necessary, with either no fade or a continuous fade level from one box to the next.

You should type your script paying attention to punctuation and capitalisation so as to ensure that it will be easy to read because, as pointed out in Chapter 1, it may need to be read by someone other than yourself. Although you may create your own idiosyncratic punctuation using dashes and ellipses to indicate the length of a pause, these markings may not mean much to somebody else. As the voice talent may also be unfamiliar with the source programme it may be useful to include pronunciation advice, particularly for character names or locations. There may be an in-house phonetic system you can use, or you may need to develop your own showing where the stress falls and how certain phonemes are pronounced. It is important that, however you show it, the pronunciation is consistent with the way a name is pronounced in the film. The phonetically written name is best either inserted in square brackets next to the actual name or used throughout instead of the correct spelling of the name, so as to avoid breaking the flow of the delivery. It may be tempting to take typing shortcuts such as leaving out capitalisations or the full stops in an abbreviation such as US. This is not a problem if the context is clear. However, you need to ensure that the reader does not say ‘us’, i.e. the first person plural, by mistake. Although they would probably soon realise their error, it might cause them to hesitate or stumble and, as a result, their recording time might increase in order to retake the phrase or sentence. Recording fluency is also why verbal cues can be helpful in addition to relying on the timecode ‘thermometer’. Often one of the function keys can be allocated to a cue font which will ensure that the text of the AD utterance is visually distinctive from the cue. It also prevents the cue being included in the word count, which might lead to your utterance apparently exceeding the WPM rate you have set in the preferences. As pointed out in Chapter 5, you are writing words to be spoken, so contractions that are common in conversation are encouraged – for example: ‘he’s’ rather than ‘he is’ – and should be written that way, with an apostrophe. If necessary, you can write your script in any word-processing package and then copy and paste it into the relevant ‘boxes’. Frequent use of the ‘save’ command is recommended. By the end of the process, your AD script will be available as an .esf file. This can be converted to an .rtf file and exported complete with timecode information, if desired.

6.2.5 Freely available software

In order to increase the amount of AD content available and accessible to users, the Inclusive Media and Design Centre at Canada’s Ryerson University has developed a free software package, LiveDescribe. According to its website, LiveDescribe is a ‘stand-alone application that allows amateur audio describers to edit audio descriptions for blind audiences’. It is a Windows-based application that can be downloaded for free. One word of caution: the software automatically identifies ‘gaps’ in the soundtrack where AD can be inserted. It is preferable to identify your own gaps, as the ‘gap’ may be inappropriate. Piety (2004) suggests that utterances ‘are strung together to fill the space between dialogue’ – but just because there is a ‘gap’ does not mean that you have to fill it.

Another free facility is called You Describe (youdescribe.org). It has been created by the Smith-Kettlewell Video Description Research and Development Center (VDRDC) at the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in San Francisco, California, with the aim of encouraging the general public to create audio-described content (or described video content, to use the American term) for YouTube. If you watch any of the videos described by this method you will notice that the image is simply paused for the duration of the description. This means that the description is not integrated with the soundtrack and the describer is always required to post-describe. Although this acceptable for the purpose for which it was designed, it is a major limitation if you wish to master the art of AD. This ‘pause for description’ method is similar to that used in the production of the early typhlofilms (films for the blind) which were produced for the blind by Andrzej Woch in Poland in the 1990s (Jankowska, 2015) before current AD norms were adopted. Apart from the danger of destroying any sense of presence and increasing the total duration of a film, this method also prevents blind and sighted audiences from being able to attend the same screening.

In the UK, describers working in the theatre until recently would always be given a paper script to which they would add their description in pencil (so it could easily be amended if necessary). In order to accommodate this, ideally, scripts were printed double-spaced and on one side of the page only. Even so, in scenes with lots of action but little dialogue describers would need to add in large arrows pointing to the back of the facing page or wherever there was enough space to write a description, or include the AD on a separate sheet of paper. Care had to be taken not to create too much extraneous noise from rustling pieces of paper while delivering the AD. Although stage directions in the script may seem to supply the narrative part of the AD text, treat them with caution. It is rare that a director follows the stage directions to the letter, and very unlikely that the directions will fit the timing available for your utterance. The tenor of the words is unlikely to fit the vivid style of your AD script and they will contain bland, generic verbs such as ‘enter’ and ‘exit’. Stage directions are unreliable as to the What and generally lacking as to the How of the visual information.

These days it is more common to be given an electronic script and to read the description from a laptop or a tablet. It is useful to write the AD in a contrasting font so as to make it stand out from the dialogue and the stage directions. It is advisable not to reduce the full script to a series of short cues, as this limits the opportunity to insert your description at a different point if a change in the actor’s delivery necessitates this by altering the position of the ‘gaps’. The way the script is punctuated can help you to anticipate the likely location of the next suitable pause. The disadvantage of reading a script from a tablet is that the glow from the screen may distract members of the audience or the actors, depending on the location of the description point; the advantage of generating an electronic AD script is that it is silent to use, more legible and can be easily shared with and read by another describer in the event of accident or illness. An added advantage for a touring or long-running production is that the script can be easily updated as the production evolves and, potentially, shared with other describers. In live events such as festivals there may be no script; however, it may be useful to make notes of, for example, performers’ names or short descriptive phrases, or even just verbs that have come to you while watching a rehearsal, otherwise you will need to completely improvise your description. While this can heighten the immediacy of your delivery, it may in turn limit your ability to find appropriate places to insert AD. It also risks repetition and lack of succinctness as you struggle to find the right words to express what you want to say. Whereas the position and duration of ‘gaps’ in recorded material will not change, for live AD you must write your script with the awareness that they almost certainly will. This means that it is safer to begin an utterance with the most important information, leaving details of less important information such as physical appearance, for example, until the end. In this way, if the ‘gap’ shortens you will be able to stop speaking without depriving your audience of critical information. Rather than ‘the King, resplendent in a blue gown, is carried in by his retinue’ you might say ‘the King’s carried in by his retinue, resplendent in a blue gown’. In the worst-case scenario you might just have time to say ‘the King’. This will be enough to indicate his arrival, although it may not explain the huffing and puffing sounds made by his servants.

The script for a live performance is generally prepared using a video of the production. This may be taken from the show-relay monitor, used by the performers to watch what is happening on stage. In some theatres in the UK, describers struggle to access a video recording of the production. In this situation you are urged to do all you can to encourage the company or the producer or theatre manager to provide you with one or, at the very least, allow you to record your own. The relationship between describers and theatres in the UK tends to be very informal. However, the ADA can supply a model contract which specifies the right of access to a video. Frequently, the video is of poor quality, shot in lighting levels that are either too low to be able to see the action clearly or so high that they bleach out the picture, making it hard to decipher fine details such as facial expression. In any case, you are encouraged to prepare a draft script and then set up a ‘dry run’.

Ana Marzà Ibañez (2010: 150) sensibly notes that in the absence of a clear, unequivocal standard for AD, students of AD need help in evaluating their work. She argues that ‘By self-evaluating their descriptions from the very first moment, the students learn to systematize their choices . . . ’. Table 6.1 is Marzà Ibañez’s checklist, which has been augmented with other scripting faults commonly encountered.

6.5.1 Exercises using software

1 Find out about speech-rate comprehension either in your native language or the native language of your target audience.

2 If you have access to AD software, use it to complete the skeleton script you prepared at the end of Chapter 3. Alternatively, script a short clip of another film of your choice, paying attention to accurate ‘In’ and ‘Out’ times and offering pronunciation advice where necessary. Swap scripts with a partner or colleague and offer a critical review, pointing out any places that caused you confusion and discussing any contentious points pertaining to the description’s content. You may wish to refer to the list of common scripting faults in Table 6.1.

If you have no access to software, do exercise 2 above using pencil and paper or a normal word-processing package. Develop your own cuing system, to compensate for lack of timecode. If you still feel unready to write your own script in English, transcribe an existing AD. Be prepared to alter it if necessary, and to argue your case for doing so.

1 What are the pros and cons of working with software?

2 What are the pros and cons of using a paper script versus reading it from a laptop or tablet?

3 What are the pros and cons of LiveDescribe versus YouDescribe versus commercial AD software?

The way in which a script is developed may vary from one organisation to another. However, the following lists will help you recognise the processes that need to happen, even if the order/personnel changes.

1 Watch the ST.

2 Write the script.

3 Write Check – have your script checked by another describer.

4 Record the script (or have it recorded by another voice).

5 Rec. Check – check the recording (see Chapter 7 and Table 7.1).

1 Watch the play and take notes on costumes, characters, sets and visual style.

2 Write the AI (see Chapter 12).

3 Write the script.

4 Dry run, with feedback from at least one other describer, plus ideally an AD user.

5 Adjust the script/AI as necessary.

6 Deliver the AD at the live performance.

7 Gather audience feedback, either directly or via front-of-house staff. Make a note for future performances.

6.7.3 The process for the AD user at live events

1 Book tickets. In the UK, theatres often offer price concessions to people with disabilities: generally tickets are half price or, if you are visually impaired, a free ticket may be provided for a sighted companion. It is important to state that you will be listening to the AD, so that the theatre applies the concession and sends you the AI in advance. You should also ask whether or not there will be a touch tour (see Chapter 3) and book to attend it, if required. This is also the time to state any other requirements you may have, such as seat preference and, if you are intending to bring a guide dog, whether or not you would like the dog to be looked after during the performance. Some theatres are happy for the dog to accompany you into the auditorium, although some performances may not be suitable because, for example, they feature gun shots and smoke effects.

2 Arrive in good time for the touch tour.

3 Collect your headset (some theatres require you to leave a deposit) if these are not distributed at the end of the touch tour. Headset designs can vary, so ask for a short lesson in how it works, if necessary. Most headsets have two channels – one that receives the AD and one that enhances the volume to the show relay. The best headsets allow you to vary the volume of each channel independently. There may be an opportunity to test out your headset to ensure that it is working properly. Ask if there is a system to attract an usher’s attention if your headset stops working.

4 Take your seat in the auditorium in good time before the AI begins (usually 15 minutes before curtain up).

5 Enjoy the show!

6 Return the headset at the end of the performance, and pass on any feedback about the AD to the theatre ushers or the theatre’s Head of Access. Find out if the theatre has an access mailing list that it can keep you informed of future described performances.

This chapter has shown that, in both screen and live AD, attention must be paid to the way a script is laid out. Consideration must be given to ease of reading, especially if the writer and reader of the AD are not the same person. Timecode facilitates script creation and synchrony in screen AD. In live AD, scripts must be prepared with some built-in flexibility. The process for creating a script was explained, and a checklist was provided to help spot common scripting errors. The standard sequence of events for those attending an AD performance was outlined.

Foulke, Emerson (1968). ‘Listening comprehension as a function of word rate’. Journal of Communication 18, no. 3: 198–206.

Jankowska, Anna (2015). Translating audio description scripts: translation as a new strategy of creating audio description, trans. Anna Mrzyglodzka and Anna Chociej. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

LiveDescribe (n.d.). Retrieved from https://imdc.ca/ourprojects/livedescribe [accessed 23.09.15].

Marzà Ibañez, A, (2010). ‘Evaluation criteria and film narrative: a frame to teaching relevance in audio description’. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 18, no. 3: 143–153.

Moos, Anja, and Jürgen Trouvain (2007). ‘Comprehension of ultra-fast speech – blind vs. “normally hearing” persons’. In Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, vol. 1, pp. 677–680. Retrieved from retrieved from: http://www.icphs2007.de/conference/Papers/1186/1186.pdf.

Piety, P. (2004). ‘The language system of audio description: an investigation as a discursive process’. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 98, no. 8: 453–469.

Pimsleur, P., Hancock, C. and Furey, P. (1977). ‘Speech rate and listening comprehension’. In M. K. Burt, H. C. Dulay, and M. Finocchiaro (eds) Viewpoints on English as a second language, New York: Regents, pp. 27–34.

Rodero, Emma (2012). ‘A comparative analysis of speech rate and perception in radio bulletins’. Text & Talk 32–3: 391–411.

Sbisà, Marina (2007). ‘How to read Austin’, Pragmatics 17, no. 3: 461.

Snyder, Joel (2005). ‘Audio description: the visual made verbal’. Vision 2005 – Proceedings of the International Congress, 4–7 April 2005, London. International Congress Series, vol. 1282, pp. 935–939. Elsevier.

Uglova, Natalia, and Tatiana Shevchenko (2005). ‘Not so fast please: temporal features in TV speech’. Paper presented at the meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Vancouver, BC.

YouDescribe. http://youdescribe.org.