The Prevalence and Importance of War

As we have seen, many recent popular and academic views of precivilized warfare agree that it was a trivial and insubstantial activity. Proponents of primitive war and the pacified past claim or imply that peaceful societies were common, fighting was infrequent, and active participation in combat was limited among nonstate peoples until they either evolved into or made contact with states and civilizations.

If these views are correct, they should be supported by broad surveys of ethnographic and archaeological evidence. Ethnographic data should indicate that nonstate societies were commonly pacifistic, resorted to combat much less frequently than did ancient or modern states, and mobilized little of their potential manpower for the warfare they did conduct. In the more thoroughly studied regions, archaeology should recover very little evidence of violent conflicts before the development of indigenous states or the intrusion of foreign states. As we shall see, on the contrary, the available evidence shows that peaceful societies have been very rare, that warfare was extremely frequent in nonstate societies, and that tribal societies often mobilized for combat very high percentages of their total manpower.

Before proceeding with any ethnographic survey, we must review some terms that are used by anthropologists in roughly classifying the size and complexity of societies. These terms include bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states, and civilized or urban states. They loosely describe the population size and the economic and political complexity of various societies.

Bands are small, politically autonomous groups of twenty to fifty people with an informal headman. They usually consist of a few related extended families who reside or move together. Typically, bands are hunter-gatherers or foragers. Several such micro-bands usually congregate for a few weeks each year into a macro-band of several hundred people for ceremonies, festivities, courting and marriage arrangements, and the exchange of goods. Such macro-bands usually speak a distinct dialect and are sometimes referred to as dialect tribes. The classic examples of societies with band organization are the Eskimo of the central Arctic, the Paiutes of the American Great Basin, and the Aborigines of central Australia.

The term tribe covers a multitude of social and political organizations. Tribes generally incorporate a few thousand people into a single social organization via pan-tribal associations. These associations are usually kin groups that trace descent to a common hypothetical or mythological ancestor. But nonkin associations, such as age-grades (groups of young men who were initiated together) and sodalities (voluntary nonkin associations such as dance societies, clubs, etc.), can also integrate a tribe. Tribes are collections of such associations or kin groups that unite for war. While tribal leaders may be called big men or chiefs, they are not formal full-time political officials, and they usually exercise influence rather than what we would call power. In most cases, there is no central political organization except informal councils of “elders” or local chiefs. Foraging, pastoral, and agricultural economies are all found among tribes. Tribes are so various in their features that it is difficult to list classic cases, but the Indian tribes of the Plains, the southwestern Pueblos, and the Masai of East Africa are familiar examples.

Chiefdoms are organizations that unite many thousands or tens of thousands of people under formal, full-time political leadership. The populace of a chiefdom is usually divided into hereditary ranks or incipient social classes, often consisting of no more than a small chiefly or noble class and a large body of commoners. Both the means of production and economic surpluses are concentrated under the control of the chief, who redistributes them. A central political structure integrates many local communities. This central body may consist of a council of chiefs, but in most cases a single head chief controls a hierarchy of lesser chiefs. Accession to chiefship is hereditary, permanent, and justified on religious or magical grounds. But a chief, unlike a king, does not have the power to coerce people into obedience physically; instead, he must rely on magical and economic powers to enforce his dictates. Some typical examples, ranging from weak to strong chiefdoms, include some Pacific Northwest Coast tribes, many Polynesian societies, early medieval Scottish clans, and some traditional petty kingdoms in central Africa.

States are also political organizations that incorporate many tens or hundreds of thousands of people from numerous communities into a single territorial unit. They have a central government empowered to collect taxes, draft labor for public works or war, decree laws, and physically enforce those laws. Essentially, states are class-stratified political units that maintain a “monopoly of deadly force”—a monopoly institutionalized as permanent police and military forces. Civilized states are simply those with cities and some form of record keeping (usually writing). Since few people in the world today are not citizens of some state, examples are unnecessary.

The term primitive, when used in its usual sense in anthropology, merely refers to a technological condition—that of using preindustrial or preliterate technology. In social terms, primitive refers to societies that are not urban or literate. Precisely such societies are the traditional subject matter of anthropology. But because the word has negative connotations in everyday speech, primitive has fallen out of favor. It has been erratically replaced by a number of inelegant neologisms such as preliterate or nonliterate, prestate or nonstate, preindustrial and small-scale. The term tribal societies usually encompasses bands, tribes, and weak chiefdoms but excludes strong chiefdoms and states. In the broadest sense, all these terms refer to societies that are simpler in technology and some aspects of social organization—and usually smaller in size—than societies that have produced historical records. Primarily for stylistic variety, all these terms are used interchangeably here.

According to the most extreme views, war is an inherent feature of human existence, a constant curse of all social life, or (in the guise of real war) a perversion of human sociability created by the centralized political structures of states and civilizations. In fact, cross-cultural research on warfare has established that although some societies that did not engage in war or did so extremely rarely, the overwhelming majority of known societies (90 to 95 percent) have been involved in this activity.

Three independent cross-cultural surveys of representative samples of recent tribal and state societies from around the world have tabulated data on armed conflict, all giving very consistent results. In one sample of fifty societies, only five were found to have engaged “infrequently or never” in any type of offensive or defensive warfare.1 Four of these groups had recently been driven by warfare into isolated refuges, and this isolation protected them from further conflict. Such groups might more accurately be classified as defeated refugees than as pacifists. One California Indian tribe, the Monachi of the Sierra Nevada, apparently did occasionally go to war, but only very rarely. The results of this particular survey indicate that 90 percent of the cultures in the sample unequivocally engaged in warfare and that the remaining 10 percent were not total strangers to violent conflict.

In another larger cross-cultural study of politics and conflict, twelve of a sample of ninety societies (13 percent) were found to engage in warfare “rarely or never.”2 Six of these twelve were tribal or ethnic minorities that had long been subject to the peaceful administration of modern nation-states—for example, the Gonds of India and the Lapps of Scandinavia. Three were agricultural tribes living in geographically isolated circumstances, such as the Tikopia islanders of Polynesia (who were defeated refugees) and the Cayapa tribe of Ecuador.3 The final three were nomadic hunter-gatherers of the equatorial jungles and arctic tundra: the Mbuti Pygmies of Zaire, the Semang of Malaysia, and the Copper Eskimo of arctic Canada. Most of these peaceful societies were recently defeated refugees living in isolation, lived under a “king’s peace” enforced by a modern state, or both. The real exceptions, representing only 5 percent of the sample, were some small bands of nomadic hunter-gatherers and a few isolated horticultural tribes.

In a study of western North American Indian tribes and bands, again only 13 percent of the 157 groups surveyed were recorded as “never or rarely” raiding or having been raided—meaning, in this case, more than once a year.4 Of these 21 relatively peaceable groups, 14 gave other evidence of having conducted or resisted occasional raids, presumably only once every few years. This leaves only 7 truly peaceful societies (4.5 percent of the sample) that apparently did not participate in any type of warfare or raiding. All these were very small nomadic bands residing in the driest, most isolated regions of the Columbia Plateau and the Great Basin.5 Again, we find the most peaceful groups living in areas with extremely low population densities, isolated by distance and hard country from other groups.

Even highly nomadic, geographically isolated hunter-gatherers with low population densities are not universally peaceable. For example, many Australian Aboriginal foragers, including those living in deserts, were inveterate raiders.6 The seeming peacefulness of such small hunter-gatherer groups may therefore be more a consequence of the tiny size of their social units and the large scale implied by our normal definition of warfare than of any real pacifism on their part. Under circumstances where the sovereign social and political unit is a nuclear or slightly extended family band of from four to twenty-five people, even with a sex ratio unbalanced in favor of males, no more than a handful of adult males (the only potential “warriors”) are available. When such a small group of men commits violence against another band or family, even if faced in open combat by all the men of the other group, this activity is not called war but is usually referred to as feuding, vendetta, or just murder.

Thus many small-band societies that are regarded by ethnologists as not engaging in warfare instead evidence very high homicide rates.7 For example, the Kung San (or Bushmen) of the Kalahari Desert are viewed as a very peaceful society; indeed, one popular ethnography on them was titled The Harmless People. However, their homicide rate from 1920 to 1955 was four times that of the United States and twenty to eighty times that of major industrial nations during the 1950s and 1960s. Before local establishment of the Bechuanaland/Botswana police, the Kung also conducted small-scale raids and prolonged feuds between bands and against Tswana herders intruding from the east. The Copper Eskimo, who appear as a peaceful society in the cross-cultural surveys just discussed, also experienced a high level of feuding and homicide before the Royal Canadian Mounted Police suppressed it. Moreover, in one Copper Eskimo camp of fifteen families first contacted early in this century, every adult male had been involved in a homicide. Other Eskimo of the high arctic who were organized into small bands also fit this pattern. Based on figures from different sources, the murder rate for the Netsilik Eskimo, even after the Mounties had suppressed interband feuding, exceeds that of the United States by four times and that of modern European states by some fifteen to forty times. At the other end of the New World, the isolated Yaghan “canoe nomads” of Tierra del Fuego, whose only sovereign political unit was the “biological family,” had a murder rate in the late nineteenth century “10 times as high as that of the United States.”8 Thus armed conflict between social units does not necessarily disappear at the lowest levels of social integration; often it is just terminologically disguised as feuding or homicide.

Both Richard Lee and Marvin Harris, defending the pacifistic nature of Kung and other simple societies compared with our own, decry the “semantic deception” that disguises the “true” homicide rates of modern states by ignoring the murders inflicted during wars.9 Let us undertake such a comparison for one simple society, the Gebusi of New Guinea. Calculations show that the United States military would have had to kill nearly the whole population of South Vietnam during its nine-year involvement there, in addition to its internal homicide rate, to equal the homicide rate of the Gebusi.10 As their ethnographer Bruce Knauft notes, “Only the most extreme instances of modern mass slaughter would equal or surpass the Gebusi homicide rate over a period of several decades.”11 There is, then, an equal semantic deception involved in manufacturing peaceful societies out of violent ones by refusing to characterize as war their only possible form of intergroup violence, merely because of the small size of the contending social units.

If many of the “peaceful” hunter-gatherer bands did in reality engage in armed conflict, were any of them genuine pacifists? Perhaps the most striking case of peaceful hunters involves the Polar Eskimo of northwestern Greenland.12 In the early nineteenth century, they consisted of a small band of some 200 people whose circumstances seemed ideally suited to a postapocalyptic science-fiction plot or perhaps a heartless social science experiment. Their icy isolation had been so complete for so long that they were unaware that any other people existed in the world until they were contacted in 1819 by a European explorer. This tiny society, whose members eked a precarious livelihood from a frozen desert, not surprisingly avoided all feuds and armed conflicts, although murder was not unknown.13 When other Eskimo from Canada and southwestern Greenland reached them after hearing of their existence from Europeans, relations with these strangers and with the Europeans they encountered were always quite amicable. The Polar Eskimo thus provide a counterexample to the recent theory that contact with Western civilization and its material goods inevitably turns peaceful tribesmen into Hobbesian berserkers.

There are a few other examples of peaceful hunter-gatherers.14 The Mbuti Pygmies and Semang of the tropical forests of central Africa and Malaysia seem to have completely eschewed any form of violent conflict and can legitimately be regarded as pacifistic. However, the Pygmy foragers were in fact politically subordinate to and economically dependent on the farmers who surrounded them (Chapter 9). Although they frequently engaged in nonlethal violence involving weapons, the last small “wild” band of Aborigines in the western Australian desert, the Mardudjara, never (at least while ethnographers were present) permitted such fighting to escalate into killing. Although they possessed shields and specialized fighting weapons, the Mardudjara had no words in their language for feuds or warfare. The Great Basin Shoshone and Paiute bands mentioned earlier apparently never attacked others and were themselves attacked only very rarely; most just fled rather than trying to defend themselves. But these few peaceful groups are exceptional. The cross-cultural samples indicate that the vast majority of other hunter-gatherer groups did engage in warfare and that there is nothing inherently peaceful about hunting-gathering or band society.15

Pacifistic societies also occur (if uncommonly) at every level of social and economic complexity. Truly peaceful agriculturalists appear to be somewhat less common than pacifistic hunter-gatherers. In the cross-cultural samples discussed earlier, almost all the peaceful agricultural groups could be characterized as defeated refugees, ethnic minorities long administered by states, or tribes previously pacified by the police or by paramilitary organs of colonial or national states.16 Low-density, nomadic hunter-gatherers, with their few (and portable) possessions, large territories, and few fixed resources or constructed facilities, had the option of fleeing conflict and raiding parties. At best, the only thing they would lose by such flight was their composure. But with their small territories, relatively numerous possessions, immobile and labor-expensive houses, food stores, and fields, sedentary farmers or hunter-gatherers who attempted to flee trouble could lose everything and thereupon risk starvation. Farmers and sedentary hunter-gatherers had little alternative but to meet force with force or, after injury, to discourage further depredations by taking revenge. Groups that depended on very localized, essential resources—such as desert springs, patches of fertile soil, good pastures, or fishing stations—had to defend these or face severe privation. Even nomadic pastoralists in extensive grasslands had to defend their herds, wherever they might be. For obvious reasons, then, agriculturalists, pastoralists, and less nomadic foragers have seldom been entirely peaceful. But such pacifistic farmers have occasionally appeared.

The best-known peaceful agriculturalists are the Semai of Malaysia, who strictly tabooed any form of violence (although their homicide rate was numerically significant).17 Their reaction to any use of force involved “passivity or flight.” Interestingly, they were recruited as counterinsurgency scout troops by the British during the Communist insurgency in Malaya in the 1950s. The Semai recruits were profoundly shocked to discover that as soldiers they were expected to kill other men. But after the guerrillas killed some of their kinsmen, they became very enthusiastic warriors. One Semai veteran recalled, “We killed, killed, killed. The Malays would stop and go through people’s pockets and take their watches and money. We did not think of watches or money. We thought only of killing. Wah, truly we were drunk with blood.” However, when the Semai scouts were demobilized and returned to their villages, they quietly resumed their nonviolent life-style. The low density of population, shifting settlement, and abundances of unused land probably allowed the Semai, unlike many other farmers, the option of flight from violent threats.18 But their strong moral distaste for violence was undoubtedly important in maintaining their peacefulness.

Peaceful societies even exist among industrial states. For example, neither Sweden nor Switzerland has engaged in warfare for nearly two centuries; their homicide rates are among the lowest in the world. Like many peaceful tribal societies, Switzerland is to some degree geographically isolated behind its mountains. Sweden was once home to the legendarily belligerent Vikings and remained one of the most warlike societies in Europe until the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, Sweden has fought no wars since 1815. Both nations traditionally maintain modern military forces; indeed, every Swiss male between the ages of twenty and fifty is a military reservist, while Sweden is one of the world’s leading arms exporters. But they and a few other nations in Asia and South America offer testimony that there is nothing inherently warlike about states.

Thus pacifistic societies seem to have existed at every level of social organization, but they are extremely rare and seem to require special circumstances. The examples of Sweden and the Semai demonstrate that societies can change from pacifistic to warlike, or vice versa, within a few generations or, (as with the Semai) within the lifetime of an individual. As these examples and the case of the Polar Eskimo establish, the idea that violent conflicts between groups is an inevitable consequence of being human or of social life itself is simply wrong. Still, the overwhelming majority of known societies have made war. Therefore, while it is not inevitable, war is universally common and usual.

How frequent are primitive wars, and do nonstate societies engage in warfare less frequently than states or civilized societies? These questions are related to the question of how intense primitive warfare is. Again turning to cross-cultural research, we find That many of the myths about primitive war are untrue.

The three cross-cultural surveys mentioned earlier also include data on the frequency of warfare. All these studies show that warfare has been extremely frequent among primitive societies.19 In the sample of fifty societies, 66 percent of the nonstates were continuously (meaning every year) at war, whereas only 40 percent of the states were at war this frequently. In this survey, warfare was therefore found to be less frequent in state societies. The larger sample of ninety societies, however, indicated that the frequency of war increased somewhat with greater political complexity; 77 percent of the states were at war once a year, whereas 62 percent of tribes and chiefdoms were this war prone. Nevertheless, 70 to 90 percent of bands, tribes, and chiefdoms went to war at least once every five years, as did 86 percent of the states. All these figures support yet another survey, which found that about 75 percent of all prestate societies went to war “at least once every two years before they were pacified or incorporated by more dominant societies” and that warfare was no more frequent “in complex societies than in simple band or tribal societies.” In the sample of U.S. western Indian tribes, which consisted wholly of nonstate societies, 86 percent were raiding or resisting raids undertaken more than once each year. And such high frequencies of fighting were not peculiar to North America.20 For example, during a five-and-a-half-month period, the Dugum Dani tribesmen of New Guinea were observed to participate in seven full battles and nine raids. One Yanomamo village in South America was raided twenty-five times over a fifteen-month period. These independent surveys show that the great majority of non-state societies were at war at least once every few years and many times each generation. Obviously, frequent, even continuous, warfare is as characteristic of tribal societies as of states.

The high frequencies of prestate warfare contrast with those of even the most aggressive ancient and modern civilized states. The early Roman Republic (510–121 B.C.) initiated a war or was attacked only about once every twenty years. During the late Republic and early Empire (118 B.C.-A.D. 211), wars started about once every six or seven years, most being civil wars and provincial revolts.21 Only a few of these later Roman wars involved any general mobilization of resources, and all were fought by the state’s small (relative to the size of the population), long-service, professional forces supported by normal taxation, localized food levies, and plunder. In other words, most inhabitants of the Roman Empire were rarely directly involved in warfare and most experienced the Pax Romana unmolested over many generations.

Historic data on the period from 1800 to 1945 suggest that the average modern nation-state goes to war approximately once in a generation.22 Taking into account the duration of these wars, the average modern nation-state was at war only about one year in every five during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Even the most bellicose, such as Great Britain, Spain, and Russia, were never at war every year or continuously (although nineteenth-century Britain comes close). Compare these with the figures from the ethnographic samples of nonstate societies discussed earlier: 65 percent at war continuously; 77 percent at war once every five years and 55 percent at war every year; 87 percent fighting more than once a year; 75 percent at war once every two years. The primitive world was certainly not more peaceful than the modern one. The only reasonable conclusion is that wars are actually more frequent in nonstate societies than they are in state societies—especially modern nations.

The informal and voluntary mobilization for war supposedly characteristic of tribal societies is often cited as evidence of the lack of importance and effectiveness of primitive versus civilized war. The idea is that if war really represented an important activity, instead of just a sport or dangerous pastime, these primitive societies would muster all of their strength.

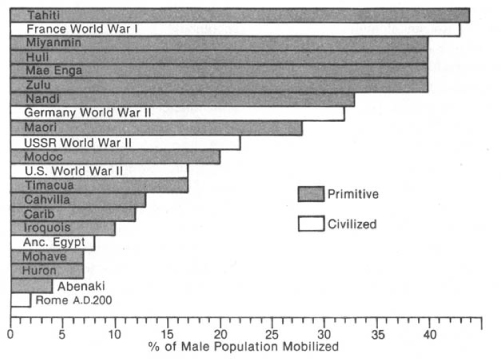

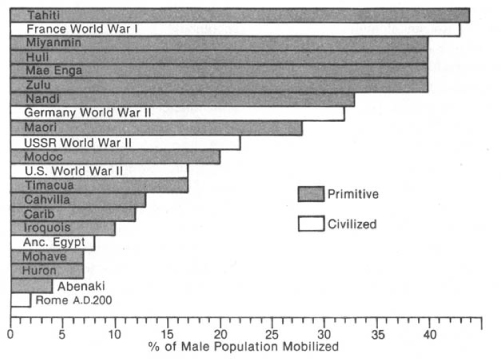

Figure 2.1 shows some selected information on the size of war parties or armies in relation to the male populations of the social units from which they were drawn. While in most nonstate societies every male over the age of thirteen or fourteen is a potential warrior, not all of them participate in any particular war, battle, or raid. In general, tribal military formations are “all-volunteer” and usually muster proportions of their potential manpower similar to those achieved in the volunteer armed forces of states. Although modern conscript armies during active warfare generally represent a high percentage of the male population, on many occasions nonstate societies mobilize a higher proportion of their manpower. In World War II, neither the Soviet Union nor the United States, despite the tremendous power of coercion enjoyed by modern states, managed during the whole war to mobilize any greater proportion of its manpower than have some tribes and chiefdoms.

The reasons why mobilization cannot be complete are essentially the same for any society. Many males are too young, too old, too ill, or temperamentally unsuited to endure the stresses of combat. Because the sexual division of labor in most societies trains men and women to be proficient in different tasks, a society’s economy may not be sustained if it is denuded of men to hunt, tend stock, clear gardens, or do whatever other essential work lies on the male side of the division. Although women may be able to take over some of these tasks, training and developing skill at them take time. It may be very unwise to focus all of a group’s manpower at one point on a border or beyond it, leaving women, children, and property vulnerable to attack from another quarter.

Figure 2.1 Percentages of male populations mobilized for combat by various tribes, ancient states, and modern nations (see Appendix, Table 2.1).

Women have very rarely engaged in combat, but have often played auxiliary roles in mobilization and logistics.23 Before hostilities commenced, they might shame cowards, taunt the hesitant, and participate in dances of incitement. Among some groups, women have accompanied war parties to carry weapons and food. During combat, they might serve as a cheering section, supply first aid, or collect spent enemy missiles to resupply their own warriors. In some cases, either by choice or by necessity (such as when the enemy breached their fortifications), some women might actually fight. For example, female warriors were apparently not unusual in northern South America. In general, though, women’s role has been to maintain the home front, tend gardens and stock, and nurse the wounded. While war may be everyone’s business, it has usually been men’s work.

In civilized war, ancient and modern, tremendous manpower (and woman-power) is required just to equip and supply military formations. The higher “warrior” proportions of modern wartime states in Figure 2.1 disguise the fact that only a fraction of the men mobilized actually engaged in combat.24 In Napoleon’s armies, at any given time, only about 58 to 77 percent of his soldiers were “effectives.” The rest were convalescing, in training, garrison troops, or members of support units. During World War II, only about 40 percent of American servicemen served in combat units. The others were involved in administration, logistical support, and training; and an even smaller percentage carried a rifle, sailed on a warship, or flew in a warplane. The “tooth to tail” ratio between combat and support troops was 1:14 for the U.S. Army in Vietnam and is now about 1:11. This diminution in the proportion of actual combatants in armies means That no modern state army can or does engage all of its mobilized manpower. These proportions reflect the huge geographic scale of modern military operations and the heavy, complex technology involved. Of course, every person mobilized is lost to the home economy and peaceful pursuits, but the fact remains that very few of them actually engage in combat. By contrast, in ancient armies and primitive war parties, almost every participant was an effective. If mobilization figures are modified to reflect the higher proportion of noncombatants in modern armed forces, the mobilization for combat of tribal societies would compare even more favorably with those of modern states. This finding also implies that males in nonstate societies are far more likely to face combat than is the average male citizen of a modern nation. By the measure of manpower mobilization, then, war is no less important to tribes than to nations.

With regard to prehistory, nothing comparable to the surveys of historical and ethnographic societies cited earlier exists as yet. Any attempts to survey 2 million years of human prehistory for evidence of violence and armed conflict face several daunting difficulties. The first is that most regions of the world are poorly known archaeologically—the rare exceptions being Europe (especially the west), the Near East, and parts of the United States. The most unequivocal evidence of armed conflict consists of human skeletons with weapon traumas (especially, embedded bone or stone projectile points) and fortifications. However, humans have buried their dead for only the past 150,000 years or so; before this, the human remains that have been found were often disturbed and fragmented by scavengers and natural forces. Even during the past 150,000 years, many prehistoric peoples disposed of their dead in ways—for example, cremation and exposure—that left no remains for anthropologists to study. Only among some peoples—those for whom the use of stone- and bone-tipped weapons (which can survive embedded in or closely associated with human skeletons) was commonplace—is it easy to distinguish accidental traumas from those inflicted by humans. The use of these weapons occurred only during the past 40,000 years, and in many regions perishable wooden and bamboo spears and projectiles continued to be used until modern times. Until humans began living in permanent villages, fortifications would have not repaid the labor required to construct them (Chapter 3). But humans seem to have become sufficiently sedentary only during the past 14,000 years, and permanent villages are common in most regions only after the adoption of farming (8000 B.C. at the earliest). Thus it is possible to document prehistoric warfare reliably only within the past 20,000 to 30,000 years and in a only a few areas of the world. Granting these limitations, what does the archaeological evidence say about the peacefulness of prehistoric peoples?

Some authors have claimed that the evidence of homicide is as old as humanity—or at least as old as the genus Homo (that is, over 1 million years).25 But many of the traumas found on early hominid skeletons have been proved by subsequent investigation to have had nonhomicidal causes or cannot be distinguished from accidental traumas of a similar character.26 For instance, the paired “spear wounds” found on some South African Australopithicine skulls are now recognized as punctures created by leopard canines as the predator carried these luckless ancestors of ours, gripping their heads in its teeth. As another example, Neanderthals seem to have been especially accident prone, compared with the modern humans who followed them. Neanderthals’ bones evidence many injuries and breakages (one study determined that 40 percent of them had suffered head injuries). Which, if any, of these injuries were caused by human violence cannot be determined. Since the heavy musculature and robust bones of Neanderthals imply that their way of life was much more strenuous and physically demanding than that of more recent humans, it seems probable that most of the traumas in question were accidental. Why they so often “forgot to duck” remains a mystery, however.

Whenever modern humans appear on the scene, definitive evidence of homicidal violence becomes more common, given a sufficient sample of burials.27 Several of the rare burials of earliest modern humans in central and western Europe, dating from 34,000 to 24,000 years ago, show evidence of violent death. At Grimaldi in Italy, a projectile point was embedded in the spinal column of a child’s skeleton dating to the Aurignacian (the culture of the earliest modern humans in Europe, ca. 36,000 to 27,000 years ago). One Aurignacian skull from southern France may have been scalped; it has cut-marks on its frontal (forehead). Evidence from the celebrated Upper Palaeolithic cemeteries of Czechoslovakia, dating between 35,000 and 24,000 years ago, implies—either by direct evidence of weapons traumas, especially cranial fractures on adult males, or by the improbability of alternative explanations for mass burials of men, women, and children—that violent conflicts and deaths were common. In the Nile Valley of Egypt, the earliest evidence of death by homicide is a male burial, dated to about 20,000 years ago, with stone projectile points in the skeleton’s abdominal region and another point embedded in its upper arm (a wound that had partially healed before his death). The one earlier human skeleton found in Egypt bears no evidence of violence, but the next more recent human remains there are rife with evidence of homicide.

The human skeletons found in a Late Palaeolithic cemetery at Gebel Sahaba in Egyptian Nubia, dating about 12,000 to 14,000 years ago, show that warfare there was very common and particularly brutal.28 Over 40 percent of the fifty-nine men, women, and children buried in this cemetery had stone projectile points intimately associated with or embedded in their skeletons. Several adults had multiple wounds (as many as twenty), and the wounds found on children were all in the head or neck—that is, execution shots. The excavator, Fred Wendorf, estimates that more than half the people buried there had died violently. He also notes that homicidal violence at Gebel Sahaba was not a once-in-a-lifetime event, since many of the adults showed healed parry fractures of their forearm bones—a common trauma on victims of violence—and because the cemetery had obviously been used over several generations. The Gebel Sahaba burials offer graphic testimony that prehistoric hunter-gatherers could be as ruthlessly violent as any of their more recent counterparts and that prehistoric warfare continued for long periods of time.

In western Europe (and more poorly known North Africa), ample evidence of violent death has been found among the remains of the final hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period (ca. 10,000 to 5,000 years ago).29 One of the most gruesome instances is provided by Ofnet Cave in Germany, where two caches of “trophy” skulls were found, arranged “like eggs in a basket,” comprising the disembodied heads of thirty-four men, women, and children, most with multiple holes knocked through their skulls by stone axes. Indeed, some archaeologists, impressed by the abundant evidence of homicide in the European Mesolithic, date the beginnings of “real” war to this period.

Indications of conflict, as reflected by violent death and the earliest fortifications, become especially pervasive in western Europe during the ensuing Neolithic period (the era of the first farmers, ca. 7,000 to 4,000 years ago, depending on the region).30 Some archaeologists have argued that real warfare begins only when hunters become farmers. This mistaken point of view does have some especially grim support in the remains of Neolithic mass killings at Talheim in Germany (ca. 5000 B.C.) and Roaix in southeastern France (ca. 2000 B.C.). At Talheim, the bodies of eighteen adults and sixteen children had been thrown into a large pit; the intact skulls show that the victims had been killed by blows from at least six different axes.31 More than 100 persons of all ages and both sexes, often with arrowpoints embedded in their bones, received a hasty and simultaneous burial at Roaix. The villages of the first farmers in many regions of western Europe were fortified with ditches and palisades. Several of these early enclosures in Britain, after being extensively excavated, yielded clear evidence of having been attacked, stormed, and burned by bow-wielding enemies. The early agricultural tribes and petty chiefdoms of Neolithic Europe were anything but peaceful.

Interestingly, the historically blood-soaked Near East has yielded little evidence of violent conflict during the Early Neolithic.32 Although extensive and elaborate fortifications were erected during this period at Jericho, they became common in the Near East only in the later Neolithic and in the Bronze Age.

When we turn to the United States—specifically to those areas that have been subject to intensive archaeological scrutiny and where large samples of human burials have been excavated, such as the Southwest, California, the Pacific Northwest Coast, and the Mississippi drainage—violent deaths are at least in evidence and, in some periods, were extremely common.33 Fortifications were constructed at various times and in various regions by prehistoric farmers in the Mississippi drainage and in the Southwest, as well as by the prehistoric sedentary hunter-gatherers of the Northwest Coast.34 As with the best-studied regions of the prehistoric Old World, the prehistoric New World was also a place where the dogs of war were seldom on a leash.

In each of these regions, the indications are that warfare was relatively rare during some periods; nothing suggests, however, that prehistoric nonstate societies were significantly and universally more peaceful than those described ethnographically. The archaeological evidence indicates instead that homicide has been practiced since the appearance of modern humankind and that warfare is documented in the archaeological record of the past 10,000 years in every well-studied region. In the chapters that follow, it will become clear that archaeological evidence strongly supports ethnographic accounts concerning the conduct, consequences, and causes of prestate warfare.

There is simply no proof that warfare in small-scale societies was a rarer or less serious undertaking than among civilized societies. In general, warfare in prestate societies was both frequent and important. If anything, peace was a scarcer commodity for members of bands, tribes, and chiefdoms than for the average citizen of a civilized state.