The Profits and Losses of Primitive War

In war, various possessions, representing wealth and the means of production, can be seized or destroyed to benefit attackers and harm defenders. Even from the corpses of the vanquished, the victors can extract gains and inflict losses on their foes. Both civilized and uncivilized adversaries experience the spoils and horrors of war in ways that extend far beyond the numbers of dead, wounded, and missing.

In Tahiti, a victorious warrior, given the opportunity, would pound his vanquished foe’s corpse flat with his heavy war club, cut a slit through the well-crushed victim, and don him as a trophy poncho.1 This custom was extreme only to the extent that most tribal warriors were seldom so surreal in their mutilations or so unselective in their choice of trophies from the bodies of their dead enemies. There are both anthropological and archaeological reasons for discussing this type of behavior in the context of costs and gains.

People in many cultures believe that improper treatment of a corpse can adversely affect the fate of the soul or spirit it once housed. For such people, deeply felt injuries could be inflicted on them by mutilation of their dead. Trophies such as scalps and heads were often included among the spoils of war because they were important tokens for reckoning male status or were thought to enhance a warrior’s spiritual power. The gains from such trophies could include elevation to manhood and the right to marry, higher status, greater favor from gods and spirits, increased spiritual power, and general well-being. In certain systems of belief, then, these gruesome practices inflicted real costs and exacted real benefits. From an archaeological perspective, mutilated skeletons provide compelling evidence of prehistoric war, since few societies would mutilate their own dead. These pathetic remains are among the most enduring effects of war.

By far the most common and widely distributed war trophy was the head or skull of an enemy. The custom of taking heads is recorded from many cultures in New Guinea, Oceania, North America, South America, Africa, and ancient western Europe.2 The popularity of this practice is probably explained by the obvious fact that the head is the most individual part of the body. For warriors the world over, the prestige or spiritual power accruing to the victor depended on the personal qualities and reputations of his victims. More than any other body part, the head of a vanquished foe was an unequivocal token of the individual that had been overcome. Such trophies were so representative of the individual from whom they were taken that victors often spoke to their trophy heads by name, reviling and exulting over them. For example, an early missionary in New Zealand heard a Maori warrior taunting the preserved head of an enemy chief in the following fashion:

You wanted to run away, did you? but my meri [war club] overtook you: and after you were cooked, you made food for my mouth. And where is your father? he is cooked:—and where is your brother? he is eaten:—and where is your wife? there she sits, a wife for me:—and where are your children? there they are, with loads on their backs, carrying food, as my slaves.3

In Maori warfare, decapitation marked the beginning, not the end, of a vanquished warrior’s humiliation.

The taking of trophy heads certainly occurred prehistorically in several areas of the world.4 The 7,500-year-old caches of trophy heads found in Ofnet Cave in Germany have already been mentioned in earlier chapters. Several headless skeletons with cut-marks on their neck vertabrae indicating decapitation were recovered from a late prehistoric site in Illinois. Prehistoric chiefdoms in Central and South America left depictions of warriors taking and displaying trophy heads, as well as the heads themselves.

The native North American custom of taking scalps is well known, although historical revisionists have popularized the notion that Indians only learned scalping from Europeans. Undoubtedly, the “scalp bounties” offered by some colonial authorities did much to encourage scalping and helped spread the custom to a few tribes that had previously disdained the practice (such as the Apaches) or that instead took the whole head as a trophy (such as the Iroquois). Nevertheless, the custom of scalping enemy dead was observed at first contact among tribes ranging from New England to California and from parts of the subarctic down to northern Mexico.5 Scalps and scalping were embedded in the myth and rituals of so many tribes that the custom’s indigenous roots in North America are beyond serious question. For example, among the Pueblos of the Southwest, “warriors’ societies” or “scalp societies” performed important ceremonial, social, and military functions; membership in them was restricted to men who had taken an enemy scalp. By contrast, the custom was unknown in ancient, medieval, and early modern Europe, where the preferred trophies were usually whole heads. Here again, archaeological evidence provides the decisive and unequivocal proof. Because the skin of the scalp is so thin, removing it from the skull leaves characteristic cut-marks on the cranial bones; such cut-marks have been found frequently on pre-Columbian skulls from many regions of Norm America.6 Indians were plainly the scalpers, and it was from them that the colonists learned the custom. However, it was the—civilized” Europeans who turned human scalps into an item of commerce.

Less common trophies taken by tribes in various areas of the world included hands, genitals, teeth, and the long bones of the arms or legs.7 These long bones were made into flutes in South America and New Zealand. Several chiefdoms in Colombia kept the entire skins of dead enemies. Often the women who accompanied their men to the battlefield flayed the victims. One group even stuffed these trophy skins, modeled the features of the victims in wax on their skulls, placed weapons in their hands, and set the reassembled trophy “in places of honor on special benches and tables within their households.”8

The symbolic significance of trophies varied enormously from one culture to another. In some, they merely provided a tangible numerical measure of a warrior’s prowess. In others, they possessed magic powers that strengthened their possessor or transferred the victim’s spirit to the victor’s benefit. They might be necessary paraphernalia for rituals honoring deities, initiating youths, or cleansing their taker of the spiritual pollution of homicide. These items might degrade the victim, injure his afterlife, or enrage his survivors, as was the intention of the Paez of Colombia, who displayed the trophy penises of their enemies in order to “shame the foe.” Body-part trophies have meant some combination or all of these things to various societies. As is so often the case in an ethnographic survey, a fundamentally similar behavior pattern displayed by many diverse groups conveys a huge range of meanings to its exhibitors.

Even if no trophies were taken, mutilations were commonly inflicted on victims’ corpses—eyes removed, bellies slit, genitals severed, features defaced, and so on—with a similar variety of significances.9 For example, the Zulus of South Africa slit a victim’s belly to release his spirit, thereby saving the killer from pollution and insanity. To express their contempt for the social group of an enemy, the Mae Enga of New Guinea mutilated his corpse by stuffing his severed penis in his mouth or, in the heat of battle, chopping him to pieces with axes. Different Plains tribes mutilated their foes’ corpses in characteristic ways as a kind of “signature”: the Sioux by cutting throats, the Cheyenne by slashing arms, the Arapaho splitting noses, and so on (Plate 2). In the aftermath of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Indian women used marrow-cracking mallets to pound the faces of dead soldiers into pulp. Perhaps the most common mutilation was “overkill,” which involved shooting so many arrows into an enemy’s body that he looked like a “human pin-cushion.” In these cases, the disfigurements expressed hatred for the enemy and were meant to enrage surviving foes.

Similar mutilations practiced on the bodies of the victims at Crow Creek in 1325, at the Larson site in 1785, and at Little Bighorn in 1876 show that the Plains’ traditions of mutilation and scalp taking persisted for over 500 years.10 Over 11,000 years ago, overkill with arrows was practiced by the enemies of the victims buried in the Gebel Sahaba cemetery in Egypt. Several adult skeletons—male and female—bore evidence of having been shot with between fifteen and twenty-five arrows. Another type of overkill involving ax blows was found on the Mesolithic trophy skulls at Ofnet, dating to 7,500 years ago. Several skulls had between four and seven ax holes, any one of which would have sufficed to cause death. Identical multiple ax traumas were found on the skulls of the Talheim Neolithic victims, dating to 7,000 years ago.

Of course, mutilation and body-part trophy taking have hardly disappeared from modern civilized warfare.11 The Third Colorado Cavalry, recruited from the dregs of Denver’s populace, took scalps from the Cheyenne they massacred at Sand Creek in 1864 and displayed these immediately after the action to general acclaim in Denver. The human-hide lampshades produced at Nazi death camps are perhaps the modern era’s preeminent symbol of evil. During the relentless fighting in the Pacific theater of World War II, Japanese mutilated Allied dead, and Americans soldiers extracted gold teeth as well as other trophies from the bodies of their enemies. Marine veteran E. B. Sledge, in a harrowing memoir of that war, compared such behaviors to scalping and felt that they were motivated by a savage mutual hatred and thirst for revenge. Both sides in the Vietnam War occasionally mutilated enemy corpses, and there are accounts of American and Australian soldiers keeping Vietnamese ears as trophies. The impulse toward such behavior clearly has not disappeared in civilized warfare, even though it is no longer morally or legally acceptable.

The most extreme mutilation inflicted on dead enemies is cannibalism. Anthropologists usually make a distinction between ritual and culinary cannibalism Ritual cannibalism, which is the more common type, involves the consumption of only a portion of a corps (sometimes after it has been reduced to ashes) for magical purposes. Culinary, or gastronomic, cannibalism consists of eating human meat as food. Some scholars also distinguish starvation cannibalism, which may occur in famine conditions, from the culinary type. Since culinary cannibalism is strongly tabooed by many cultures, it has been a favorite propaganda accusation against unfriendly neighbors or distant strangers. Anthropological views of this phenomenon stretch from the neo-Hobbesian acceptance of almost all such accusations in the nineteenth century to the recent neo-Rousseauian denial that culinary cannibalism ever existed anywhere, except briefly under conditions of extreme starvation.12 Certainly, it appears that many of the societies accused of culinary cannibalism either were being slandered by their enemies or, at most, practiced ritual cannibalism.

The diversity of opinion concerning the existence of culinary cannibalism exists because most anthropologists have had to rely primarily on the testimony of interested witnesses, such as missionaries, colonial administrators, and native propagandists. That wholesale consumption of humans would necessarily leave forensic circumstantial evidence for the archaeologist—in the form of human bones treated in the same fashion as the bones of nonhuman food mammals—seems to have escaped most students of cannibalism; archaeologists, with a few exceptions, have ignored the problem.13 However, there do seem to be some well-attested and self-admitted ethnographic instances of culinary cannibalism (or at least ritual cannibalism on such a large scale that it is indistinguishable from the former). Many of these cases are also supported by archaeological evidence.14

Many tribes and chiefdoms in southern Central America and northeastern South America reputedly consumed large numbers of their dead foes and captives.15 Notwithstanding some kind of magical or religious justification for cannibalism, several of these groups seemed to have positively relished human flesh. One record reports that a Colombian chief and his retinue consumed the bodies of 100 enemies in a single day following a victory. In another chiefdom, war captives were kept in special enclosures and fattened before consumption. Many of these groups smoked or otherwise preserved human meat to be eaten later. The Ancerma of western Colombia reportedly lighted their gold mines with lamps fueled by human fat and sold captives to their neighbors for use as food.

Enemy corpses and captives were eaten on a similar scale in a few places in Oceania.16 On Fiji, one chief kept a tally of the number of bodies he had consumed by placing a stone for each victim in a line behind his house; the line stretched nearly 200 meters and contained 872 stones. Maori war parties supplemented their logistics and extended their campaigns by consuming enemy bodies and captives taken in battle. Several groups in New Guinea admitted to having conducted raids motived by the desire for human flesh. In many of these Oceanian cases, consistent archaeological data support the ethnographic descriptions.

Culinary cannibalism was often attributed to West African tribes. But as with similar accusations elsewhere in the world, most cases proved to be exaggerations of ritual cannibalism or misinterpretations of customs that had nothing to do with cannibalism, such as preserving enemy skulls as war trophies or sharpening the front teeth for aesthetic or erotic purposes. Still, some tribes in the eastern Congo seem to have consumed the bodies of those killed in battle. Indeed, some Belgian colonial officers resigned themselves to tolerating the practice, even going so far as to claim it was useful and hygienic. None of the usual reasons for skepticism about these Congolese accounts are present, since they were recorded only in confidential diaries or in letters to discreet intimates (because the cannibal tribes were military allies of the Belgians).17

Other instances of culinary cannibalism have been documented by archaeology in places where, according to ethnographic sources, it was supposedly absent. In the American Southwest, for example, twenty-five sites containing cannibalized human remains have been found.18 These assemblages of disarticulated human bones share a number of features: butchering cut-marks, skulls broken, long bones smashed for marrow extraction, bones burned or otherwise cooked, and disposal with other “kitchen” refuse. At these sites, the treatment of the human bones suspected to represent the remains of cannibal consumption are comparable in almost every respect with the remains of nonhuman food animals. Almost all these occurrences are dated to Pueblo II and III times (A.D. 900–1300), which were periods when droughts appear to have been frequent. The intensively studied remains from Mancos show various pathologies indicative of nutritional deficiencies. Cannibalism in the prehistoric Southwest involved too thorough a consumption of bodies to be merely ritual; instances seem to be too common to represent simple survival cannibalism, and yet they seem to occur when other foods might well have been scarce. Given the very fragmentary condition of the skeletons and the numerous traumas inflicted on them in the course of their consumption, it is usually difficult to tell whether violence accompanied the victims’ deaths. At one site, the rib of one victim had a projectile point embedded in it; at several sites, the cannibalism and some destruction of structures seem to have been contemporaneous. No one analyzing these bones has uncovered any evidence that the victims died nonviolently, and most analysts accept these cases as indications of intergroup violence.

Another unexpected case comes from the Early Neolithic (3000–4000 B.C.) of southern France.19 Several concentrations of disarticulated human bones were found at Fontébregoua Cave, showing all of the characteristics noted for the American Southwest cases. Several other plausible cases in Europe date to the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. Thus, except perhaps for material from Oceania, the best documented and most unequivocal archaeological evidence of culinary cannibalism comes from two areas—southern France and the American Southwest—never suspected of the practice on historical or ethnographic grounds. Perhaps this very absence of suspicion impelled the archaeologists working there to be exceptionally thorough in their documentation and arguments.

Finally, there is the celebrated controversy over cannibalism in the Aztec empire, which Marvin Harris refers to as the only “cannibal state.” The argument of some cultural materialists is that the primary goal of Aztec warfare was to capture enemy soldiers for sacrifice and cannibal consumption because densely populated central Mexico had few other sources of animal protein.20 Their critics claim variously that Aztec warfare was motivated only by a religious desire to capture victims for sacrifice to the gods, that cannibalism was only of the ritual variety and made an insignificant contribution to the that, or that other sources of sufficient protein did exist. There can be little doubt that the Aztecs annually sacrificed large numbers of war captives in their great temples and that parts of these victims’ bodies were eaten. There were even special recipes for human stews. But the number of such victims, even if they had been completely consumed (which they were not), would not have yielded much protein for such a large population. And if obtaining meat was the object of Aztec warfare, why were only sacrificed captives eaten, and not the bodies of enemies killed on the battlefield? Archaeological excavation of the central temple complex in Mexico City has uncovered ample evidence of human sacrifice but none yet of cannibalism—perhaps because the temple precincts were not where the bodies were consumed.21 Even if future excavations should turn up abundant evidence of cannibalism, the debate will probably continue, since it principally concerns the motive for Aztec warfare: Did the Aztecs go to war because they were obeying the dictates of their religion to capture victims for sacrifice or because they needed meat?

Both sides this debate seem to have ignored the fact that during the century before Cortés, the Aztecs created their great conquest empire by using a very familiar form of warfare leading eventually to the seizure of land and subjugation of enemy societies as tributaries. The most useful spoils the Aztec empire gained by war were an enlarged territory and more taxpayers. As Barry Isaac concludes, the capture of sacrificial victims was “secondary or even incidental” to the political and economic goals of the Aztec ruling elite—however important it may have been to the prestige of the individual Aztec soldier.22

Ritual consumption of parts of a foe’s body was very widely distributed, if not exactly common. The parts consumed included brains, hearts, livers, bits of flesh, an the ashes from various parts mixed with a beverage.23 The purposes given are highly various, but common ones include to humiliate the enemy, to absorb his courage or spirit, to take spiritual as well as corporeal revenge. For example, Zulu warriors drank a soup made from selected “powerful” parts (penis, rectum, right forearm, breastbone, and so on) of a victim as a “strengthening” for battle. In the Solomon Islands, warriors drank blood from the severed head of raid victims to increase their spiritual power, or mana. Many groups in the Americas ate the hearts of slain enemies to absorb the latters’ courage or to achieve an extended form of revenge. The frequency with which similar practices have been reported around the world is evidence that, while hardly the norm, ritual consumption of some part of enemy corpses was by no means rare in prestate warfare.

The case of Polynesians of the Marquesas Islands offers a warning that distinctions among ritual, culinary, and starvation cannibalism may sometimes reflect only the difference between the natives’ distorted memories and the more objective circumstantial evidence recovered by archaeology. According to the accounts given by Marquesans to missionaries and ethnographers, they ate only small pieces of enemy flesh or merely mixed the juices from these pieces in other food, and did so purely for revenge. In ethnographic terms, the Marquesans would then be classified as ritual cannibals. But archaeological data from several Marquesan sites indicate that the scale of cannibalism was large and that its practice increased as certain other sources of animal protein declined and the human population expanded.24 This evidence strongly suggests that, rather than being consumed in token quantities for ritualistic purposes, human meat was replacing overexploited and disappearing sea mammals, birds, and sea turtles in the Marquesan that. In this case at least, the lines between starvation, ritual, and culinary cannibalism seem indistinct.

It is clear, then, that the consumption of enemies corpses has occurred in the warfare of several tribes and chiefdoms. Yet, to paraphrase Harris, victorious states may have ruthlessly exploited the vanquished, but, with the exception of the Aztecs, they have never actually consumed them.

Besides lives, property and means of production are lost in wars. In this regard, prestate warfare differs not a whit from its civilized counterpart—invaders the world over have commonly plundered portable food stores, livestock, and valuables; burned houses and crops; destroyed fences and field systems.25 Plunder of food stores and gardens was very widespread practice in the Americas, Polynesia, New Guinea, and Africa and could leave an enemy facing starvation. When livestock was plundered, it was usually the species that—whatever its practical functions—symbolized or represented wealth: horses among the Plains tribes; pigs in highland New Guinea; camels among the Bedouin; cattle among East Africa tribesmen and among the ancient Germans and Celts of Europe. Often what could not be carried away was destroyed. When the Nuer of the Sudan raided Dinka villages, besides stealing cattle, they destroyed grain stores and standing crops; severe famine could result. In New Guinea, Tahiti, and the Marquesas, invaders would even girdle or chop down the nut and wild fruit trees in an enemy’s territory. In a typical Mae Enga interclan war, about 5 to 10 percent of the total housing of either side was destroyed. Mae Enga houses were substantial productions, so the destruction of so many represented a severe blow. Very valuable and difficult-to-replace canoes would be smashed or burned by raiders on the Pacific Northwest Coast and in Polynesia. The destruction of villages and gardens was so thorough in the Cauca Valley of Colombia that warfare there was described as “a fight for annihilation, carried out by every available means.” Such looting and vandalism commonly rendered the afflicted territory temporarily uninhabitable.

In civilized wars, because modern states have larger territories, redundant transportion networks, and a broad margin of productivity above the bare subsistence level, years of destruction and blockade may be necessary to reduce one to starvation. But, as previously noted, prestate societies, had small territories and much slimmer margins of productivity. Primitive social units could be reduced to a famine footing by the consequences of a few days of raiding or even of a single surprise attack. Because the infrastructure and logistics of small-scale societies were more vulnerable to looting and destruction, the use of these methods was almost universal in primitive warfare. And the economic injuries inflicted tended to be more deeply felt and slower to heal.

Looting and vandalism are difficult to document archaeologically. For example, looted goods cannot be distinguished from similar items acquired by peaceful means. A burned dwelling leaves a very obvious archaeological signature, but vandalism is not suspected unless the destruction is accompanied by other evidence of violence. Despite these limitations, archaeologists have uncovered many examples of war-related destruction of settlements from the best-studied regions of the world.

The massacre of their inhabitants and burning of prehistoric villages along the Missouri River in South Dakota have been mentioned in a previous chapter. In some regions of the American Southwest, the violent destruction of prehistoric settlements is well documented and during some periods was even common.26 These instances of destruction are often correlated in time and space with the fortification or relocation of settlements to more defensible positions and sometimes with evidence of cannibalism. For example, the large pueblo at Sand Canyon in Colorado, although protected by a defensive wall, was almost entirely burned; artifacts in the rooms had been deliberately smashed; and bodies of some victims were left lying on the floors. After this catastrophe in the late thirteenth century, the pueblo was never reoccupied. The pueblo of Kuaua in New Mexico was plundered and destroyed around 1400, and the site was abandoned about that time and not reoccupied until seventy-five years later. In addition to the stormed and burned British Neolithic causewayed camps mentioned in Chapter 1, a number of similarly destroyed settlements have been found in western Europe and the Nea East, dating to the later Neolithic, Copper, and Bronze Ages.27

In the early days of World War II, Britain’s air minister refused to let the Royal Air Force bomb German arms factories because they were private property. Obviously, prestate warriors had much more in common with General Sherman than this English ninny.28 Except in geographical scale, tribal warfare could be and often was total war in every modern sense. Like states and empires, smaller societies can make a desolation and call it peace.

One of the most persistent myths about primitive warfare is that it did not change boundaries because it was not motivated by territorial demand. This whole question has become muddied by the propensity of “idealists” to transmute intentions or causes into effects—that is, if warriors said that they were not fighting for land or booty, then the spoils that accrued to them must be insubstantial and irrelevant. The idealists’ opponents, the “materialists,” make exactly the reverse mistake: they claim that because economic benefits were gained by victorious warriors, these gains must be what they were really fighting for, despite their declarations to the contrary. This amounts to mistaking an effect for a cause. Of course, few tribal groups ever admitted they were fighting for territory (the Mae Enga were a rare exception to this rule). Like modern and ancient states, they invariably claimed to be fighting to avenge or redress various wrongs: murders, broken trade or marriage contracts, abduction of women, poaching, or theft. But the victors nevertheless acquired more territory or choice resources with striking regularity, albeit (like the British Empire) “in a fit of absent-mindedness.”

Indeed, several cross-cultural surveys of preindustrial societies found that losses and gains of territory were a very frequent result of warfare.29 One study concluded that the victors “almost always take land or other resources from the defeated.” In another study, almost half of the societies surveyed had gained or lost territory through warfare. In some cases, societies lost land to one enemy while gaining it from another. Over 75 percent of the wars of the Mae Enga of New Guinea ended with the victors appropriating part or all of their enemy’s territory.30 In other words, territorial change was a very common outcome of primitive wars.

Two wars fought by the Wappo hunter-gatherers of California illustrate both the intentional and the unintentional territorial windfalls resulting from tribal warfare.31 Six village communities of the Southern Pomo occupied a portion of the Alexander Valley (now renowned for its wine) along the Russian River, but their upstream neighbors were a village community of tough Wappo (whose name is an Anglo corruption of the Spanish guapo, meaning, in this case, “brave”). About 1830, some Pomo made the mistake of stealing an acorn cache from a Wappo oak grove. The Wappo immediately retaliated with two raids, killing a large number of Pomo and burning the offending village. All of the Pomo from the six Alexander Valley villages fled to other Pomo settlements downstream. The headman of the Pomo village cluster later exchanged gifts with his Wappo counterpart and settled the dispute. The Pomo were then invited to reoccupy their villages, but they refused. These changes at least temporarily widened the distance between the nearest Russian River Valley Wappo and Pomo villages from one to about ten miles. In the few years remaining before their decimation by disease and war with Mexican settlers, the Wappo occupied two of the six abandoned Pomo villages and had begun seasonally exploiting much of the relinquished area.

More than twenty years earlier, another group of Wappo had established themselves, by unknown means, in Pomo territory farther north on a small creek flowing into Clear Lake. These Wappo were dissatisfied because a delectable minnow spawned from the lake up a Pomo-held creek whose lower course ran only a few yards from their own minnowless stream. After digging a canal to divert the waters of the Pomo’s creek into their own, the Wappo dammed the latter, apparently hoping by these activities to force the spawning fish to use their stream. With this provocation, their Pomo neighbors determined to fight, and a battle broke out along the course of the deputed creek. After some losses, the Wappo were driven back to their still-minnowless creek.

In both cases, as was typical in aboriginal California, disputes over food resources precipitated the fighting. In one case, the Wappo were merely fighting to defend their rights to enjoy the produce of a particular acorn grove, but the fierceness of their response (and probably previous conflicts) convinced the Pomo to put some unoccupied territory between themselves and their fractious neighbors. The depopulated area was then exploited and slowly settled by the victors. This pattern of abandoning territory out of fear in order to widen a buffer zone, followed by gradually intensified use of the zone by the victors, illustrates the most common mechanism by which primitive warfare expanded and contracted the domains of prestate societies. In the Clear Lake case, the Wappo were obviously attempting to take control, if not actual possession, of a desirable stream and were driven back. Had the Wappo been victorious in the Clear Lake fight, the creek would undoubtedly have been added to the Wappo domain of exploitation. In neither case were the combatants fighting over land per se; rather they were fighting over spatially fixed resources.

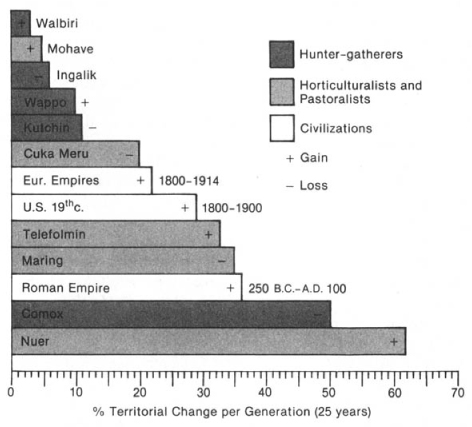

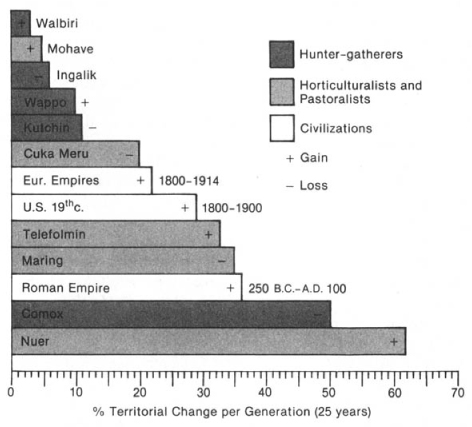

As Figure 7.1 shows, the scale of such territorial gains and losses could be very significant—about 5 to 10 percent per generation in some instances involving hunter-gatherers. This would be equivalent to the United States losing or gaining California, Oregon, and half of Washington every twenty-five years. The rates of expansion and contraction among agriculturalists and pastoralists tended to be even higher. In one New Guinea case, the Telefolmin tribe more than tripled its territory in less than a century by means of ruthless warfare and virtual annihilation of the tribe’s enemies. By relentlessly raiding its Dinka neighbors, rather than by pursuing any conscious campaign or plan, the Nuer tribe of the Sudan expanded its domain from 8,700 to 35,000 square miles in just seventy years. Comparable examples of territorial acquisition and loss as an effect of warfare are recorded from every major ethnographic region of the world.32 These primitive rates of territorial change are proportionately similar to the extraordinary expansion rates of European empires and the United States during the nineteenth century, or of the growth of the Roman Empire. In this sense, tribal warfare against other prestate societies appears to have been just as effective as civilized war at moving boundaries and rewarding victors with vital territory appropriated from the losers.

Figure 7.1 Relative territorial gains and losses per generation for various soceities (see Appendix, Table 7.1).

Given the aversion of modern archaeology to the idea of migration and colonization (let alone conquest), the problem of documenting such processes in prehistory is difficult. One archaeologist who has given considerable thought to this problem, Slavomil Vend, admits that annihilation or forced migration would be manifested in the archaeological record only by the “peaceful existence of winners on the territory of the losers.”33 He gives as an example the victory of the Germanic Marcomanni over the Celtic Boii (from whom the region became known as Bohemia), recorded by Roman historians. Archaeologically, this event is evidenced only by the expansion of Germanic settlements and cemeteries into regions previously inhabited by Celts. An additional difficulty, as we have seen in the ethnographic cases, is that many violent territorial exchanges involve social units that are nearly identical in culture and physique. Prehistory is replete with examples of very distinctive cultures (sometimes associated with distinct human physical types) expanding at the expense of others, but determining whether these expansions were accomplished violently or peacefully is usually no simple task. Several regions of the world offer evidence that at least some prehistoric colonizations or abandonments of regions were accompanied by considerable violence.34 These most visible prehistoric cultural expansions, which involve the movement of a frontier, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

As we have seen, even in situations where no territory exchanges hands, active hostilities along a border can lead to development of a no-man’s-land, as settlements nearest an enemy move or disperse to escape the effects of persistent raiding. Such buffer zones have been reported from Africa, North America, South America, and Oceania.35 As in the Wappo-Pomo case, encroachment on these zones by the stronger, more land-hungry, or more aggressive adversary was a common mechanism by which tribal warfare led to the exhange of territory, even in the absence of any clear design. The width of these no-man’s-lands varied with population density.36 High-density economies could afford to concede only a small amount of land to such low-intensity use and had a limited capacity to settle elsewhere refugees who fled such zones. Moreover, the higher the settlement density, the more eyes there were to watch for raids, the more rapid the communication of alarms became, and the more quickly local forces and allies could respond to incursions. Thus no-man’s-lands tended to shrink with increasing human density because they became more costly economically to create and because the security belt they provided was less necessary.

Where population density was high, these buffer zones were measured in hundreds of meters, as in highland New Guinea. Where density was lower, their width stretched to tens of kilometers, as in the more lightly populated areas of the Americas or in the dry savannas of Africa. Although such buffer zones could function ecologically as game and timber preserves, they were risky to use even for hunting and woodcutting because small isolated parties or individuals could easily be ambushed in them.

Whatever their stated purposes in going to war, tribal groups, like civilized ones, were not averse to accepting the spoils of war—which usually included valuable goods and often land. Andrew Vayda, one of anthropology’s most distinguished students of primitive warfare, decries the obscurantism of certain distinguished social scientists who (in contrasting primitive and civilized war) ignore the essential similarities—”as, for example, the fact that both types of warfare can result in territorial conquests and the redistribution of population.”37