Chapter 4

Rotary Pumps

The rotary pump is used primarily as a source of fluid power in hydraulic systems. It is widely used in machine-tool, aircraft, automotive, press, transmission, and mobile-equipment applications.

A set of symbols has been established for pumps and other hydraulic components, approved by the American National Standard Institute, Inc., and known as ANS Graphic Symbols. These symbols are an aid to the circuit designer and to the maintenance personnel who might be checking out a hydraulic system. In the photos of each pump shown in this chapter will be the ANS Graphic Symbol for that pump.

Principles of Operation

The rotary pump continuously scoops the fluid from the pump chamber, whereas the centrifugal pump imparts velocity to the stream of fluid. The rotary pump is a positive-displacement pump with a circular motion; the centrifugal pump is a nonpositive-displacement pump.

Rotary pumps are classified with respect to the impelling element as follows:

• Gear-type

• Vane-type

• Piston-type pumps

Gear-Type Pumps

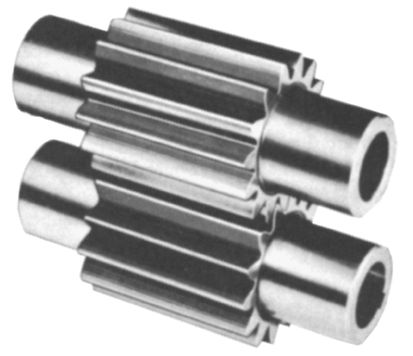

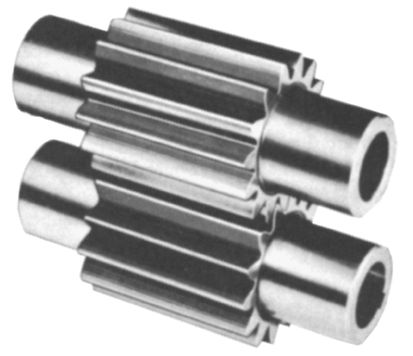

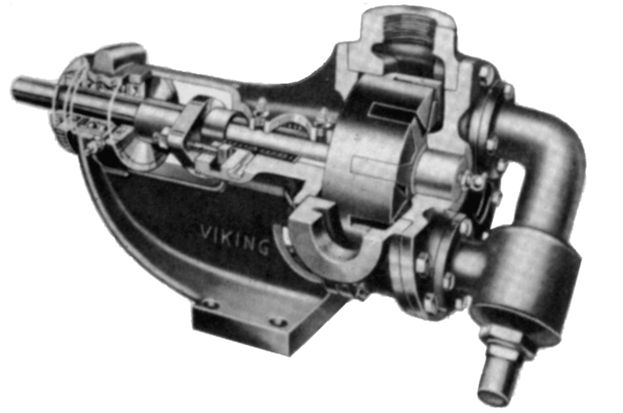

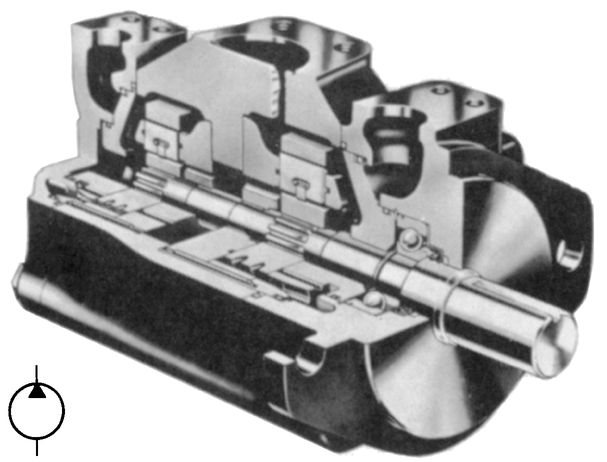

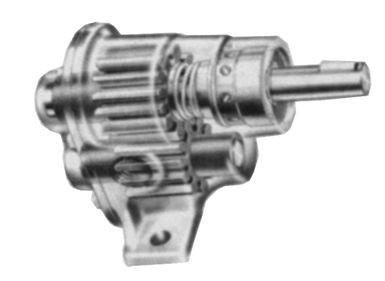

The gear-type pump is a power-driven unit having two or more intermeshing gears or lobed members enclosed in a suitably shaped housing (see

Figure 4-1). Gear-type pumps are positive-delivery pumps, and their delivery rate can be changed only by changing the speed at which the pump shaft revolves. The efficiency of a gear-type pump is determined largely by the accuracy with which the component parts are machined and fitted.

Gear pumps are available in a wide range of ratings, from less than 1 gallon per minute (gpm) to more than 100 gpm and for pressures from less than 100 psi to more than 3000 psi.

In

Figure 4-2 the two gears fit closely inside the housing. The hydraulic oil is carried around the periphery of the two gears, and it is then forced through the outlet port by the meshing of the two gears at their point of tangency. The gear-type pump is also classified as to the type of gears used:

• Spur-gear

• Helical-gear

• Herringbone-gear

• Special-gear such as the Gerotor principle

Figure 4-2 Movement of a liquid through a gear-type hydraulic pump: (A) liquid entering the pump; (B) liquid being carried between the teeth of the gears; and (C) liquid being forced into the discharge line.

Spur-Gear

Two types of spur-gear rotary pumps are used:

• The external type

• The internal type

In operation of the external type of gear pump, vacuum spaces form as each pair of meshing teeth separates, and atmospheric pressure forces the liquid inward to fill the spaces. The liquid filling the space between two adjacent teeth follows along with them. This happens as they revolve and it is forced outward through the discharge opening. That is because the meshing of the teeth during rotation forms a seal that separates the admission and discharge portions of the secondary chamber (see

Figure 4-2).

In operation of the internal-gear type of rotary pump, power is applied to the rotor and transferred to the idler gear with which it meshes. As the teeth come out of mesh, an increase in volume creates a partial vacuum. Liquid is forced into this space by atmospheric pressure and remains between the teeth of the rotor and idler until the teeth mesh to force the liquid from these spaces and out of the pump. The internal-gear type of rotary pump shown in

Figure 4-3 and

Figure 4-4 possesses only two moving parts: the precision-cut rotor and idler gears. As shown in the cross-sectional view of the pump, the teeth of the internal gear and idler gear separate at the suction port and mesh again at the discharge port.

Shaft rotation will determine which port is suction and which port is discharge. A look at

Figure 4-3 will show how rotation determines which port is which. As the pumping elements (gears) come out of mesh, point

A, liquid is drawn into the suction port; as the gears come into mesh, point

B, the liquid is forced out the discharge port. Reversing the rotation reverses the flow through the pump. When determining shaft rotation, always look from the shaft end of the pump. Unless otherwise specified, rotation is assumed clockwise (CW), which makes the suction port on the right side of the pump.

Internal and external gear-shaped elements are combined in the Gerotor mechanism (see

Figure 4-5). In the Gerotor mechanism, the tooth form of the inner Gerotor is generated from the tooth form of the outer Gerotor, so that each tooth of the inner Gerotor is in sliding contact with the outer Gerotor at all times, providing continuous fluid-tight engagement. As the teeth disengage, the space between them increases in size, creating a partial vacuum into which the liquid flows from the suction port to which the enlarging tooth space is exposed. When the chamber reaches its maximum volume, it is exposed to the discharge port. As the chamber diminishes in size because of meshing of the teeth, the liquid is forced from the pump. The various parts of the Gerotor pump are shown in

Figure 4-6.

Figure 4-3 Basic parts and principle of operation of the internal type of spur-gear rotary pump.

(Courtesy Viking Pump Division)

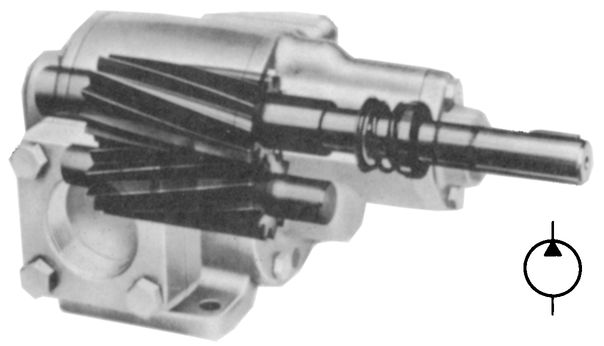

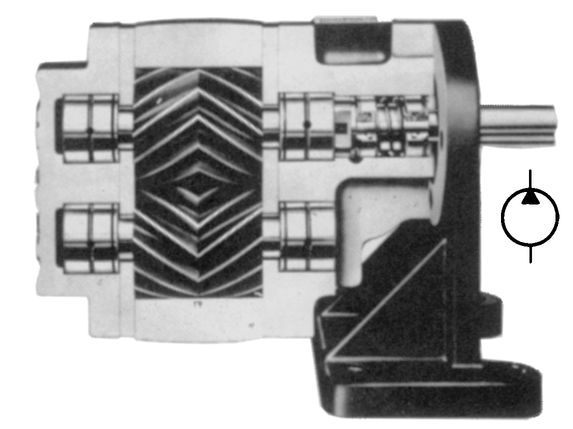

Helical-Gear

Figure 4-7 shows a rotary pump with helical gears. This pump is adaptable to jobs such as pressure lubrication, hydraulic service, fuel supply, or general transfer work pumping clean liquids. This pump is self-priming and operates in either direction. The rotary pump (see

Figure 4-8) is adapted to applications where a quiet and compact unit is required (such as a hydraulic lift or elevator application).

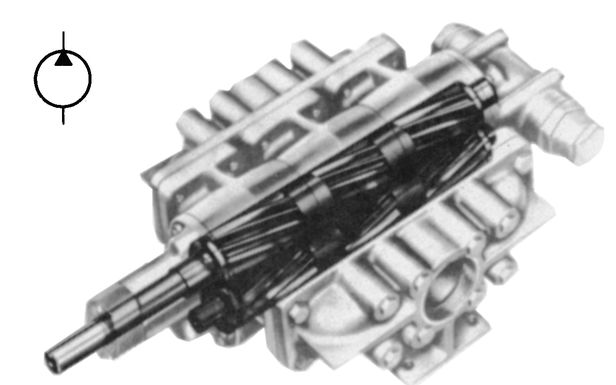

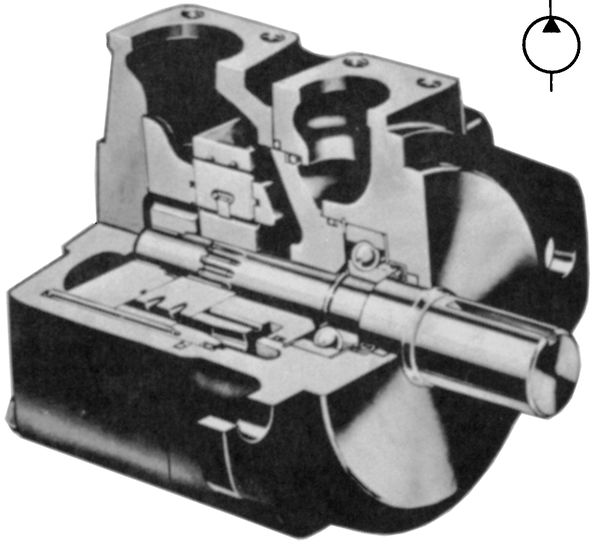

Herringbone-Gear

A rotary pump with herringbone gears is shown in

Figure 4-9. This is also a quiet and compact unit.

Vane-Type Pumps

In the rotary vane-type pump (see

Figure 4-10), operation is also based on the principle of increasing the size of the cavity to form a vacuum, allowing the space to fill with fluid, and then forcing the fluid out of the pump under pressure by diminishing the volume.

Figure 4-4 Cross section of an internal-type spur-gear rotary pump.

(Courtesy Viking Pump Division)

Figure 4-5 Schematic of the Gerotor mechanism.

(Courtesy Double A Products Co.)

Figure 4-6 Basic parts of a Gerotor pump.

(Courtesy Double A Products Co.)

Figure 4-7 A rotary gear-type pump with helical gears. This pump is adapted to jobs such as pressure lubrication, hydraulic service, fuel supply, or general transfer work pumping clean liquids.

The sliding vanes or blades fit into the slots in the rotor. Ahead of the slots and in the direction of rotation, grooves admit the liquid being pumped by the vanes. This moves them outward with a force or locking pressure that varies directly with the pressure against which the pump is operating. The grooves also serve to break the vacuum on the admission side. The operating cycle and the alternate action of centrifugal force and hydraulic pressure hold the vanes in contact with the casing, as shown in

Figure 4-11.

Figure 4-8 A rotary gear-type pump with helical gears adapted to applications requiring a quiet and compact unit, such as a hydraulic lift or elevator application.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-9 Sectional view of a rotary gear-type pump with herringbone gears.

(Courtesy Brown & Sharpe Mfg. Co.)

Figure 4-11 Operating principle of a rotary vane-type pump. The alternate actions of centrifugal force and hydraulic pressure keep the vanes in firm contact with the walls of the casing.

Vane-type pumps are available as:

Figure 4-12 Cutaway view of a high-speed high-pressure single-stage vane-type pump. This pump can operate at speeds to 2700 rpm and pressure to 2500 psl.

(Courtesy Sperry Vickers, Div. of Sperry Rand Corp.)

The double-stage vane-type pump may consist of two single-stage pumps. They would be mounted end to end on a single shaft. A combination vane-type pump is also available. It may be two pumps mounted on a common shaft. The larger pump may be pumping at low pressure, and the smaller pump may be delivering at high pressure. This type of pump may be called a “hi-low” pump.

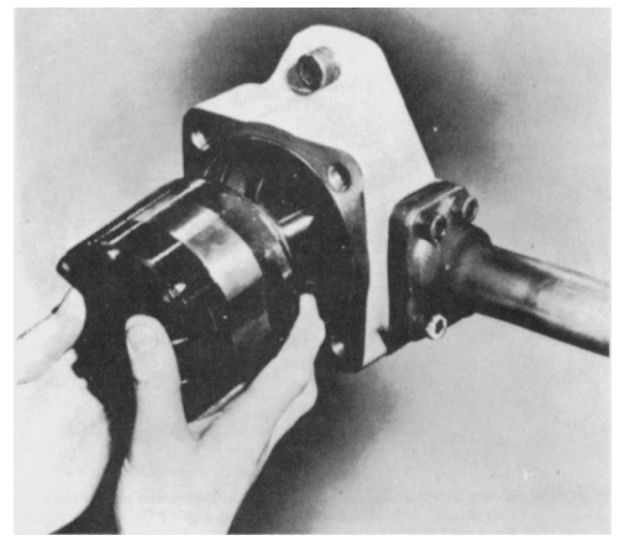

In the pumps shown in

Figure 4-12 and

Figure 4-13, the wearing parts are contained in replaceable cartridges (see

Figure 4-14). Since the pumping cartridges within each pump series are interchangeable, the pump capacities can be modified quickly in the field.

Figure 4-13 Cutaway view of a high-speed high-pressure double-stage vane-type pump. This pump can operate at speeds to 2700 rpm and pressures at 2500 psl.

(Courtesy Sperry Vickers, Div. of Sperry Rand Corp.)

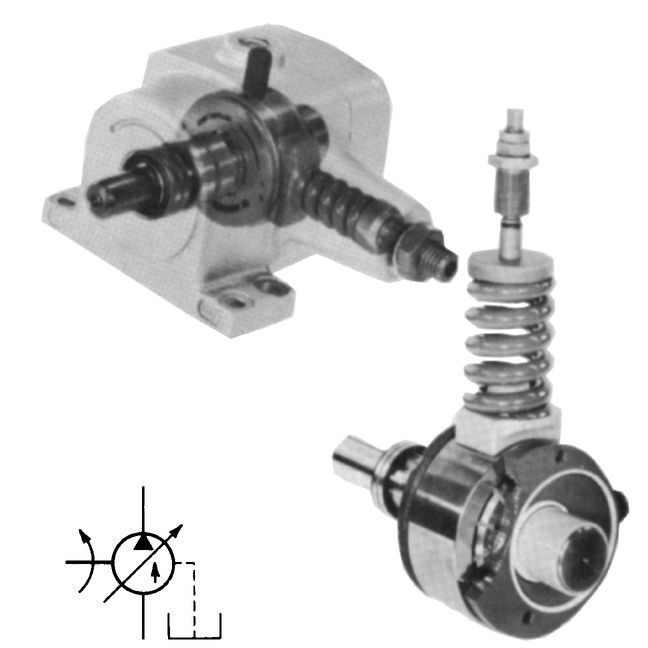

In the

variable-volume vane-type pump (see

Figure 4-15), a pressure compensator is used to control maximum system pressure. Pump displacement is changed automatically to supply the exact rate of flow required by the system. If the pump displacement changes, system pressure remains nearly constant at the value selected by the compensator setting.

If the hydraulic system does not require flow, the pressure ring of the pump is at a nearly neutral position, supplying only leakage losses at the set pressure. If full-capacity pump delivery is required, the pressure drops sufficiently to cause the compensator spring to stroke the pressure ring to full-flow position. Any flow rate from zero to maximum is automatically delivered to the system to match the circuit demands precisely, by the balance of reaction pressure and compensator spring force. This reduces horsepower consumption as flow rate is reduced. Bypassing of pressure oil does not occur and excess heat is not generated, which are important factors in the efficiency of the circuit.

Figure 4-14 A replaceable pump cartridge.

(Courtesy Sperry Vickers, Div. of Sperry Rand Corp.)

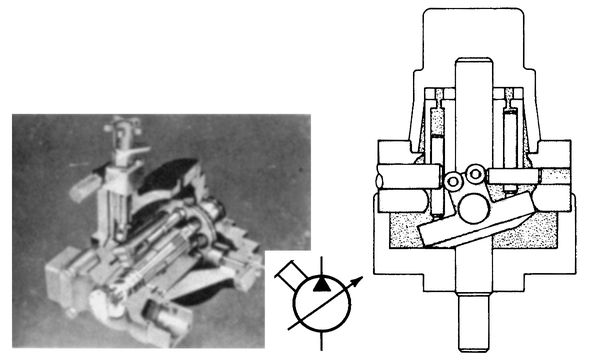

Piston-Type Pumps

Rotary piston-type pumps are either radial or axial in design. Each of these pumps may be designed for either constant displacement or variable displacement.

The pistons are arranged around a rotor hub in the radial pump (see

Figure 4-16). In the

Figure 4-16, the side block is at the right-hand side of the centerline of the cylinder barrel. Reciprocating motion is imparted to the pistons, so that those pistons passing over the lower port of the pintle deliver oil to that port, while the pistons passing over the upper port are filling with oil. The delivery of the pump can be controlled accurately from zero to maximum capacity, because the piston and movement of the slide block can be controlled accurately.

In the axial piston-type pump, the pistons are arranged parallel to the shaft of the pump rotor. The driving means of the pump rotates the cylinder barrel. The axial reciprocation of the pumping pistons that are confined in the cylinder is caused by the shoe retainer, which is spring-loaded toward the cam plate. The piston stroke and the quantity of oil delivered are limited by the angle of the cam plate (see

Figure 4-17).

Figure 4-15 A variable-volume vane-type pump with spring-type pressure compensator.

(Courtesy Continental Hydraulics)

A mechanism is used to change the angle of the cam plate in the variable-volume pump. The mechanism may be a hand wheel, a pressure-compensating control, or a stem control that actuates a free-swing hanger attached to the cam plate for changing the angle of the cam plate.

Construction

To ensure dependable, long-life operation, rotary pumps are of heavy-duty construction throughout. Fluid power components that can perform satisfactorily at higher operating pressures are needed to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for faster, more positive-acting original equipment.

Figure 4-16 Sectional view of a variable-delivery radial piston-type pump.

(Courtesy Oilgear Company)

Figure 4-17 Cross-sectional view of a constant-displacement axial piston-type pump.

(Courtesy Abex Corp., Denison Division)

Gear-Type Pumps

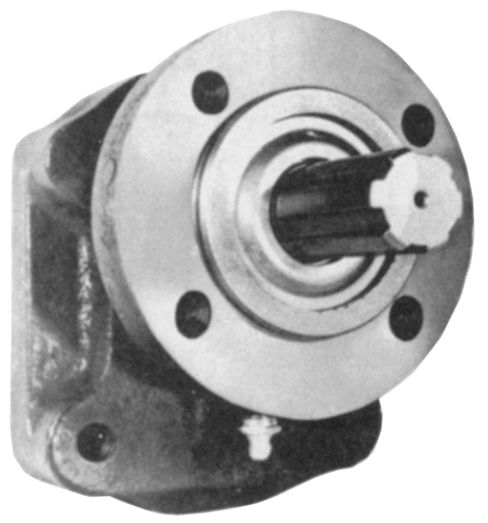

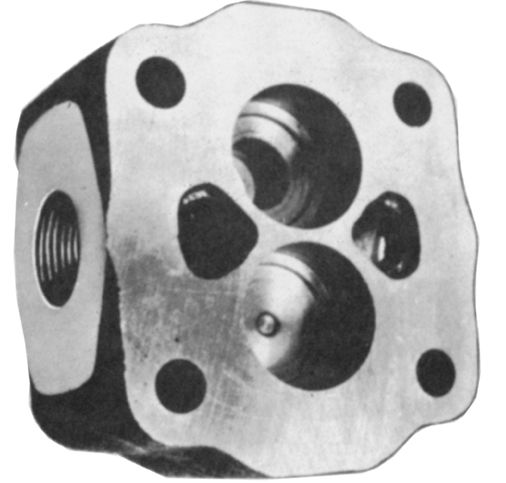

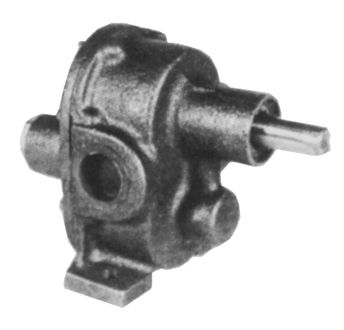

Heavy-duty gear-type pumps are able to withstand rugged operating conditions, are simple in construction, and are economical in cost and maintenance (see

Figure 4-18). High volumetric efficiency of gear-type pumps depends on maintaining complete sealing of all gear tooth contact surfaces. All gear surfaces are precision finished, and each pair is matched carefully.

Figure 4-18 Cutaway view showing parts of a single fluid-power pump.

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

Gear-type pumps are made with fewer working parts than many other types of pumps. Gear housings are available with tapered thread, SAE split flange or straight thread fittings, and with no porting, or left- and/or right-hand side porting (see

Figure 4-19). The pumps are used to handle all kinds of liquids over a wide range of capacities and pressures. Viscosities cover the range from gasoline, water, all petroleum products, paint, white lead, and molasses. They are generally made of the following materials:

• Standard fitted—Case is cast iron, internal working parts to suit individual manufacturer’s design.

• All iron—All parts of the pump in direct contact with the liquid are made of iron or ferrous metal.

• Bronze fitted—Iron casing with bronze pumping elements.

• All bronze—All parts in direct contact with liquid are made of bronze.

• Corrosive-resisting—All parts in contact with liquid are of materials offering maximum resistance to corrosion.

Figure 4-19 Housing for a gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

Table 4-1 indicates the kind of construction generally used, based on the liquid to be pumped. If there were a hot liquid to be pumped, it would be best to consult with the engineering department of the particular company before making a selection.

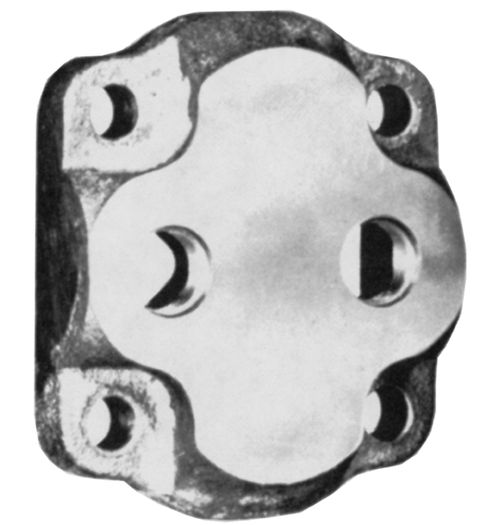

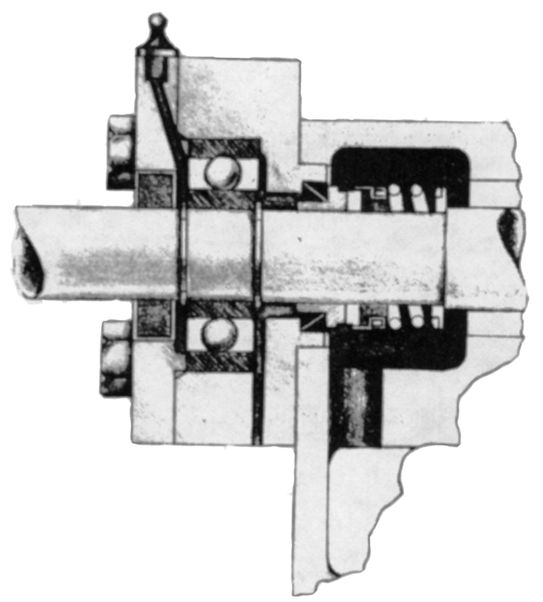

End covers for fluid power pumps are usually specified and coded. These details are important in specifying and ordering parts. The

shaft-end cover (see

Figure 4-20) may be furnished in either flange or pad mounting, and the

port-end cover (see

Figure 4-21) may be provided either with no porting or with end porting arrangements.

Figure 4-20 A four-bolt shaft-end cover for a gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

Figure 4-21 A port-end cover for a gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

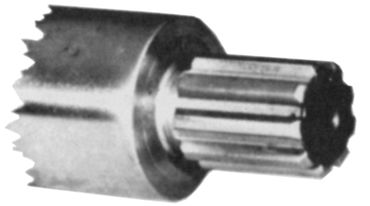

The

drive shafts (see

Figure 4-22) are also specified and ordered by code number. They may be either splined or straight-keyed shafts.

Figure 4-22 Straight-splined drive shaft for a gear-type pump

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

A

bearing carrier (see

Figure 4-23) is used on tandem pumps and motors. It is positioned between adjacent pumps or motors. The bearing carrier is also available with tapered thread,

SAE thread, and straight-thread fittings, and either with no porting or with leftand /or right-hand side porting.

Figure 4-23 A bearing carrier which is placed between the two adjacent pumps in a tandem gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Commercial Shearing, Inc.)

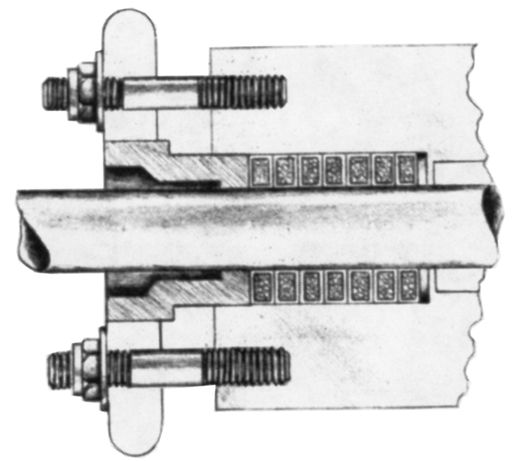

Some rotary gear-type pumps for general-purpose applications use a packed box for the shaft seal (see

Figure 4-24). The packing gland should be adjusted to permit slight seepage for best performance. A

mechanical seal (see

Figure 4-25) uses less power than the packed box, has longer service life under proper conditions, and does not require adjustment. Special mechanical seals, such as

Teflon (500°F and corrosion resistant), can be supplied for special conditions.

In the rotary pump, a

steam chest (see

Figure 4-26), located between the casing and the outboard bearing, effectively transfers heat to both the pump and the packing. It can be used with hot water, steam, and heat transfer oil; or it can be used as a cooling chamber. The steam chest is ideal for transferring thick, viscous liquids (such as asphalt mixes, creosote, refined sugars, corn starch, and so on).

An

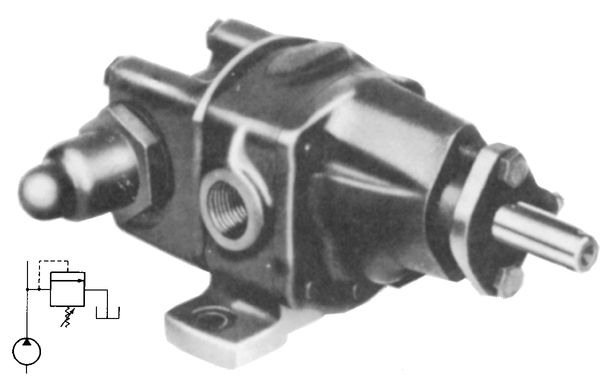

adjustable relief valve (see

Figure 4-27) in the pump faceplate eliminates outside piping and protects the pump from excessive outlet line pressure; it also permits the operator to close the discharge line without stopping the pump, under standard operating conditions. Various spring sizes are available to provide adjustments over the full operating range of the pump from 30 to 100 psi.

Figure 4-24 Packing for a rotary gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Many mounting styles are available for convenience in mounting rotary pumps (see

Figure 4-28). Bedplates and mounting brackets are available to permit the coupling of pumps and motors for complete motor-driven units (see

Figure 4-29). The rotary gear-type pumps also may be mounted in various other styles, including the

foot-mounted (see

Figure 4-30) and the

end-bell mounted (see

Figure 4-31) pumps.

As mentioned, the rotary gear-type pumps are simple in design, and have fewer working parts, than the rotary vane-type and piston-type pumps.

Figure 4-32 shows the names of the various parts of a typical gear-type pump and parts list.

Vane-Type Pumps

Figure 4-33 shows the design principle of hydraulic balance. Bearing loads resulting from pressure are eliminated, and the only radial loads are imposed by the drive itself. Communication holes in the rotor direct pressure from spaces behind the vanes to their lower edges. The outside edges of the vanes are machined to a bevel, holding them in continuous hydraulic balance, except for the pre-selected area of the intra-vane ends.

Figure 4-25 Mechanical seal for a rotary gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Piston-Type Pumps

The

radial piston-type pump (see

Figure 4-34) is a rugged and compact high-pressure pump. The walls of the pistons are tapered to a thin-edged section capable of expanding against the cylinder wall as pressure is applied. The higher the pressure, the tighter the seal becomes, to increase the efficiency of high-pressure systems. Positive-acting check valves properly port the suction and discharge oil for each piston. The suction check valves are positively seated by the quick action of the piston.

Figure 4-35 shows sectional views of a radial piston-type pump.

Figure 4-26 A steam chest used on a rotary pump for steam and hot-water applications.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-27 An adjustable relief valve protects the rotary gear-type pump from excessive outlet line pressure.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-28 Mounting styles available for Roper rotary pumps.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-36 shows a cutaway view of a variable-volume

axial piston-type pump. The pistons operate against an inclinable cam or hanger (see inset). The pump delivery is in direct proportion to the tilt of the hanger that is tilted either manually or automatically by means of various types of controls

Figure 4-29 Bedplates and mounting brackets permit coupling of pumps and motors for complete motor-driven units.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-30 Foot-mounted rotary gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Figure 4-31 End-bell mounted rotary gear-type pump.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

Installation and Operation

Many of the installation, operation, and maintenance principles that apply to centrifugal pumps can also be applied to rotary pumps. Since rotary pumps are commonly much smaller than centrifugal pumps, the foundation that is required is usually smaller, but the requirements are similar.

Alignment

Correct alignment is required for successful operation of the pump. A flexible coupling cannot compensate for incorrect alignment. If the rotary pumping unit is aligned accurately, the flexible coupling can then serve its purpose—to prevent the transmission of end thrust from one machine to another and to compensate for slight changes in alignment that may occur during normal operation.

Each pumping unit should be aligned accurately at the factory before it is shipped. After the unit is assembled, it is aligned by placing the base plate on a surface plate and then leveling the machined pads. Shims are inserted beneath the feet of both the pump and the driver to obtain correct alignment.

In many instances, the manufacturer cannot assume full responsibility for proper mechanical operation, because the base plates are not rigid. This means that the unit must be aligned correctly after it is erected on the foundation. The unit is usually supported on the foundation by wedges placed near the foundation bolts. The wedges underneath the base plate are adjusted, until a spirit level placed on the pads indicates that the pump shaft is level.

Figure 4-33 Design principle of hydraulic balance in the rotary vane-type pump (left). The lighter-colored area is the inlet, and the darkershaded area is the outlet—rotation is clockwise. The design of the vane is shown at right.

(Courtesy Sperry Vickers, Div. of Sperry Rand Corp.)

Figure 4-34 A radial piston-type pump.

(Courtesy Rexnard, Inc., Hydraulic Component Div.)

Figure 4-35 Sectional views of a radial piston-type pump.

(Courtesy Rexnard, Inc., Hydraulic Component Div.)

Figure 4-36 Cutaway view of a variable-volume axial piston-type pump (left) and Inclinable cam or hanger (right) that is tilted to control pump’s delivery.

(Courtesy Roper Pump Company)

The alignment should be checked and corrected to align the coupling half of the driver with the coupling half of the pump. The shafts can be aligned by means of a straightedge and thickness gage (see

Figure 4-37). The clearances between the coupling halves should be set so that they cannot strike, rub, or exert end thrust on either the pump or the driver.

Before placing the unit in operation, oil should be added to the coupling. The alignment should be checked again after the piping to the pump has been installed, because the units are often sprung or moved out of position when the flange bolts are tightened, especially if the flanges were not squared before tightening.

Figure 4-37 Method of aligning coupling by means of a straightedge and wedge.

To prevent a strain or pull on the pump, extreme care should be exercised to support the inlet and discharge piping properly. Improper support of the piping frequently causes misalignment, heated bearings, wear, and vibration.

Drives for Rotary Gear Pumps

Depending on the power and speed requirements, the pump and power source may be directly coupled or driven through a gear reduction. Speed reduction can also be achieved with V belts or and chain-and-sprocket. The latter puts radial load on the pump drive shaft. Therefore, precautions should be taken to ensure that the pump is built to withstand the conditions set up by the drive. Improper alignment and excess radial loads can cause a pump to wear out rapidly.

Power for Driving Pumps

The manufacturer of the pump can provide complete information on power sources for rotary gear pumps. Following, though, are some tips.

Electric motors are probably the most common drive for rotary pumps. Manufacturers’ catalogs show proper horsepower requirements for a given set of conditions. If the power requirements are somewhere between a smaller and a larger motor, opt for the larger. An electric motor can be momentarily overloaded without serious consequences, but continuous duty under overload conditions will burn it out.

Installation conditions will indicate the type of motor to select. An open motor is fine where conditions are dry and clean. Where there is a moisture possibility, select a motor that guards against this. If flammable liquids are used, then an enclosed, explosion-proof motor must be selected.

Most communities have laws as to conditions of installation. It would be prudent to check these out before selecting a motor.

Internal combustion engines are used where there is no electricity, or where portability is required.

In estimating the size of an engine for a job, it is necessary to allow a reasonable safety factor. A gasoline engine should not be operated continuously at its maximum capacity, but should have a 20 percent to 25 percent allowance for losses caused by atmospheric conditions and wear, to ensure a reasonable engine life. Added torque will be needed for starting and for abnormal application conditions. This means that, according to present practice of power ratings, a gas engine should be selected with twice the rating of an electric motor for the same job. For best performance, an engine should not be operated at less than 30 percent of its top-rated speed.

Power take-offs are commonly used on equipment where the pump is part of the unit, and the required speed, power, and control can be made available.

Piping

The general requirements for installation of piping are similar to those for centrifugal pumps. Sufficient static negative lift (static head) should be provided on the inlet line, in addition to the vapor pressure, to prevent vaporization of the liquid inside the pump when highly volatile liquids (butane, propane, hot oils, and so on) are being pumped. The discharge piping should be extended upward through a riser that is approximately five times the pipe diameter (see

Figure 4-38). This prevents gas or air pockets in the pump and acts as a seal in high-vacuum service. A valve at the top of the riser can be used as a vent when starting the pump. A bypass line with a relief valve can be installed to protect the pump from excessive pressure caused by increased pipe friction in cold weather, and from accidental closing of the valve in the discharge line. The relief valve should be set not more than 10 percent higher than the maximum pump discharge pressure.

Figure 4-38 Incorrect (left) and correct (right) methods of installing discharge piping.

If steam jackets are necessary, the inlet is located at the top and the outlet at the bottom. On water jackets, the inlet is at the bottom and the outlet is at the top. Valves should be installed in the inlet lines to regulate the quantity of fluid to the jackets.

Direction of Rotation

The direction of rotation of a pump is usually indicated by an arrow on the body of the pump. This varies with the type of pump. For example, in a double-helix gear-type pump, the direction of rotation is counterclockwise when standing at and facing the shaft extension end.

Rotation of internal-gear roller bearing pumps can be reversed by removing the outside bearing cover and stuffing box. Then the small plug in the side plate casting is transferred to the opposite side. These small plugs (one plug in each side plate) should be on the discharge side, to induce circulation through the bearings to the inlet, and to maintain inlet pressure on the stuffing box and ends of the drive shafts.

For another example, a pump operating on the internal-gear principle has the following instructions for determining direction of rotation:

• In determining the desired direction of rotation, the observer should stand at the shaft end of the pump.

• Note that the balancing groove in the shoe should be located on the inlet side.

• If a change in direction of rotation is desired, it is necessary only to remove the cover. Then, remove both the upper and lower shoes, turn them end for end to place the grooves on the new inlet side, and reassemble the pump.

Another model built by the same pump manufacturer is listed as an “automatic-reversing” pump. Regardless of the direction of shaft rotation and without the use of check valves, a unidirectional flow is maintained.

The instructions for determining the direction of rotation for a helical-gear type of rotary pump are as follows. To determine the direction of rotation, stand at the driving end, facing the pump. If the shaft revolves in a left-hand to right-hand direction, its rotation is

clockwise; if the shaft revolves in a right-hand to left-hand direction, its rotation is

counterclockwise. As shown in the

Figure 4-39, a change in direction of rotation of the pump drive shaft reverses the direction of flow of the liquid, causing the inlet and discharge openings to be reversed.

Figure 4-39 Flow of liquids and direction of rotation in rotary gear-type pumps.

Motors usually rotate in a counterclockwise direction. The direction of rotation for a motor is determined from a position at the end of the motor that couples to the pump.

As indicated in the foregoing examples, the direction of rotation for the various types of pumps should be obtained from the manufacturers’ instructions. Some types of rotary pumps are reversible and some types are nonreversible.

Starting and Operating the Pump

Before starting the pump, it should be primed. Then, the prime mover should be checked for proper direction of rotation. Pressure or vacuum should be checked on the inlet side, and pressure should be checked on the outlet side, to determine whether they conform to specifications and whether the pump can deliver full capacity without overloading the driver.

Operation should be started at a reduced load, gradually increasing to maximum service conditions. Pumps with external bearings may require occasional lubrication or soft grease for the bearings. If grease fittings are not furnished on pumps with internal bearings, lubrication is not necessary.

Practical Installation

Gear pumps are simple and rugged in construction. A minimum number of moving parts ensures longer service life and lower maintenance cost. Their design criteria are for high flow at moderate pressures. Gear pumps are self-priming and excellent for viscous liquids. All fluids must be free of abrasives such as sand, silt, and wettable powders.

Suction

For best performance, the pump should be installed as near the liquid source as possible.

Figure 4-40 shows proper piping arrangement of gear pumps and the location of other equipment for safe operation of the unit. Excessive pipe lengths and elbows create fluid losses that detract from the overall efficiency of the pump. It is recommended in good practice that the total suction lift (sum of static and dynamic lift) should not exceed 15 feet. Intake porting should never be reduced for piping convenience. Reducing the porting on any given size unit will starve the pump and cause cavitations which will result in a form of internal erosion. Line strainers are recommended for use on the suction side of installations (see

Figure 4-41).

Discharge

Since gear pumps are positive displacement, care must be taken with the use of restrictive devices (such as gate valves) in the discharge line for purpose of throttling. Accidental closing of the discharge line can cause extreme overpressure, which may result in serious damage to the pump or motor. If the discharge line throttling is necessary, selection of the pump with a built-in relief valve should be considered.

Figure 4-40 Installation of a gear pump.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Types of Gear Pumps

Cast-iron rotary gear pumps are ideal for pumping oils and other self-lubricating liquids.

Figure 4-42 shows one of a number of models available.

Figure 4-43 shows bronze rotary gear pumps with self-lubricating carbon bearings and relief valve. High-grade brass castings machined to close tolerances are used for maximum pumping efficiency. A stainless steel shaft is provided for proper corrosion resistance.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Figure 4-43 (A) Bronze rotary gear pump, model BB series. (B) Bronze rotary gear pump, model S&V series.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

The stainless steel rotary gear pump has a stainless steel body, cover, and shaft (see

Figure 4-44). It also has polyphenylene sulfide rotary gears with a Viton dripless mechanical shaft seal. Oil-less carbon graphite bushings and self-lubricating, sealed ball bearings minimize maintenance and provide long time trouble free service.

Gear pumps are well suited for pumping viscous liquids if the following rules are observed:

• Pump speed (rpm) must be reduced. Use

Table 4-2 as a guide.

• Suction and discharge lines must be increased by at least one pipe size, or better, two pipe sizes, over the size of the pump parts.

• Horsepower of the motor must be increased over whatever power rating would be required for pumping water under the same pressure and flow.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

| Viscosity in SSU | Recommended Speed (rpm) |

|---|

| 50 | 1725 |

| 500 | 1500 |

| 1000 | 1300 |

| 5000 | 1000 |

| 10,000 | 600 |

| 50,000 | 400 |

| 100,000 | 200 |

Table 4-3 shows the percent in increase in horsepower for pumping viscous liquids.

Pressure Relief Valve

On pumps that are supplied with built-in relief valves such as shown in

Figure 4-45, the valve may be adjusted and used to temporarily prevent pump and motor damage that can occur when the discharge line is closed off.

Figure 4-45 Rotary gear pump with built-in relief valve.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

This relief valve is not set at the factory. Extended operation under shut-off conditions could cause overheating and damage the pump.

To regulate the relief valve, remove the cap covering the valve adjustment screw. Turning the adjustment screw in will increase the pressure setting. Turning the adjustment screw out will reduce the pressure setting.

The relief valve must always be on the discharge side of the pump. The valve assembly can be removed and reversed on the pump cover to accommodate this. If operation calls for prolonged closing-off of the discharge line while the pump is running, then a full-line bypass relief valve should be permanently placed in the discharge line with a return line to the supply screw.

Rotary Pump Troubleshooting

Rotary pumps, like centrifugal pumps, normally require little attention while they are running. However, most troubles can be avoided if they are given only a small amount of care, rather than no attention at all. Some of the more frequent causes of trouble are indicated here.

No Liquid Delivered

The following steps should be taken if no liquid is delivered:

1. Stop pump immediately.

2. If pump is not primed, prime according to instructions.

3. Lift may be too high. Check this factor with a vacuum gage on the inlet. If the lift is too high, lower the position of the pump and increase the size of the inlet pipe; check the inlet line for air leaks.

4. Check for wrong direction of rotation.

Insufficient Liquid Delivered

One of the following causes may result in delivery of insufficient liquid:

• Air leak in the inlet line or through the stuffing box. Oil and tighten the stuffing-box gland. Paint the inlet pipe joints with shellac.

• Speed too slow. The rpm should be checked. The driver may be overloaded, or the cause may be low voltage or low steam pressure.

• Lift may be too high. Check with a vacuum gage. Small fractions in some liquids vaporize easily and occupy a portion of the pump displacement.

• Excess lift for hot liquids.

• Pump may be worn.

• Foot valve may not be deep enough (not required on many pumps).

• Foot valve may be either too small or obstructed.

• Piping is improperly installed, permitting air or gas to pocket inside the pump.

• Mechanical defects, such as defective packing or damaged pump.

Pump Delivers for a Short Period, Then Quits

This problem may be a result of one of the following causes:

• Leak in the inlet.

• End of the inlet valve is not deep enough.

• Air or gas in the liquid.

• Supply is exhausted.

• Vaporization of the liquid in the inlet line. Check this with the vacuum gage to be sure that the pressure in the pump is greater than the vapor pressure of the liquid.

• Air or gas pockets in the inlet line.

• Pump is cut by presence of sand or other abrasives in the liquid.

Rapid Wear

Some of the causes of rapid wear in a pump are the following:

• Grit or dirt in the liquid that is being pumped. A fine-mesh strainer or filter can be installed in the inlet line.

• Pipe strain on the pump casing causes the working parts to bind. The pipe connections can be released and the alignment checked to determine whether this factor is a cause of rapid wear.

• Pump operating against excessive pressure.

• Corrosion roughens surfaces.

• Pump runs dry or with insufficient liquid.

Pump Requires Too Much Power

Too much power required to operate the pump may be caused by the following:

• Speed too fast.

• Liquid either heavier or more viscous than water.

• Mechanical defects, such as a bent shaft, binding of the rotating element, stuffing boxes too tight, misalignment caused by improper connections to the pipelines, or installation on the foundation in such a way that the base is sprung.

• Misalignment of the coupling (direct-connected units).

Noisy Operation

The causes of noisy operation may be the following:

• Insufficient supply, which may be because of liquid vaporizing in the pump. This may be corrected by lowering the pump and by increasing the size of the inlet pipe.

• Air leaks in the inlet pipe, causing a crackling noise in the pump.

• Air or gas pockets in the inlet.

• A pump that is out of alignment, causing metallic contact between the rotors and the casing.

• Operating against excessive pressure.

• Coupling out of balance.

Calculations

In nearly all installations, it is important to calculate the size of pump, horsepower, lift, head, total load, and so on. This is important in determining whether the system is operating with maximum efficiency.

Correct Size of Pump

It is always important to determine whether the pump is too large or too small for the job—either before or after it has been installed.

Problem

In a given installation, a pump is required that can fill an 8000-gallon tank in two hours. What size pump is required?

Solution

Since the capacity of a pump is rated in gallons per minute (gpm), the 8000 gallons in two hours that is required can be reduced to gpm as follows:

If the rated capacity of a given pump indicates that the pump can deliver 70 gpm at 450 rpm, and since the capacity of a pump is nearly proportional to its speed, the rpm required to deliver 66 2/3 gallons of water per minute can be determined as follows:

Therefore, if the pump is rated to deliver 70 gpm at 450 rpm, it should be capable of delivering 66 2/3 gpm at 428.6 rpm, which is within the rated capacity of the pump.

Friction of Water in Pipes

The values for loss of head caused by friction can be obtained from Chapter 3. The values in

Table 3-3 are based on 15-year-old wrought-iron or cast-iron pipe when pumping clear soft water. The following coefficients can be used to determine the friction in pipes for various lengths of service:

• New, smooth pipe—0.71

• 10-year-old pipe—0.84

• 15-year-old pipe—1.00

• 20-year-old pipe—1.22

Friction Loss in Rubber Hose

The friction loss in smooth bore rubber hose is about the same as corresponding sizes of steel pipe.

Table 4-4 shows the loss in pounds per 100 feet of hose.

Table 4-4 Loss in Pounds per 100 Feet of Smooth Bore Rubber Hose

Dynamic Column or Total Load

The

dynamic column or

total load must be calculated before the horsepower required to drive the pump can be calculated. The dynamic column (often referred to as

total load) consists of the

dynamic lift plus the

dynamic head (see

Figure 4-46).

Figure 4-46 The dynamic or total column for a pumping unit.

Dynamic Lift

The dynamic lift (in an installation) consists of static lift and frictional resistance in the entire length of inlet piping from the water level to the intake opening of the pump. To determine the static lift, measure the vertical distance from the water level in the well to the center point of the inlet opening of the pump. The frictional loss is then added to the static lift, which gives the dynamic lift.

As an example, a delivery of 70 gpm is required from a pump located 10 feet (static lift) above the level of the water in the well. The horizontal distance is 40 feet, and new 2-inch pipe with two 2-inch elbows is to be used.

The friction loss for 70 gpm through 100 feet of 15-year-old pipe is 18.4 feet (from

Table 3-3). Since new pipe is to be used, multiply 18.4 feet (loss in 15-year-old pipe) by the coefficient 0.71 for new, smooth pipe. Thus, 13.064 feet (18.4 × 0.71) is the friction loss. The total length of the inlet line (including elbows which have been converted to equivalent feet of straight pipe) is:

Vertical pipe: 10 feet

Horizontal pipe: 40 feet

Elbows (equivalent to straight pipe): 16 feet

Total: 66 feet

Since the values in the table for friction loss are based on 100 feet, multiply 13.06 (loss in new pipe) by 0.66 (feet in inlet line ÷ 100). Thus, 8.62 feet (13.06 × 0.66) is the total loss caused by friction of water in the pipe.

Therefore, dynamic lift (static lift + frictional resistance in inlet pipe) is equal to 18.62 feet (10.0 feet + 8.62 feet). It should be noted that, in this example, the dynamic lift is less than 25 feet. If the calculated dynamic lift were more than 25 feet, either the pump must be lowered or a larger pipe is necessary to reduce the frictional resistance to flow, which may bring the dynamic lift to a value within the 25-foot limit.

Dynamic Head

In an installation, the dynamic head consists of the static head plus the frictional resistance in the entire discharge line, including elbows, to the point of discharge. The static head is determined by measuring the vertical distance from the center point of the pump outlet to the discharge water level.

As an example, a pump with a capacity of 70 gpm is used to force water through a vertical pipe that is 30 feet (static head) in length and a horizontal pipe that is 108 feet in length (2-inch new pipe with three elbows).

The friction loss at 70 gpm through 100 feet of 15-year-old 2-inch pipe is 18.4 feet (from

Table 3-3). Since the coefficient for new pipe is 0.71, the friction loss is 13.064 feet (18

.4 × 0

.71). The friction loss in the total length of the discharge line is:

Total discharge line (30 + 108): 138 feet

Equivalent for three elbows: 24 feet

Total: 162 feet

Since values in

Table 3-3 are based on 100 feet of pipe, multiply 13.06 (loss in new pipe) by 1

.62(162 ÷ 100). Thus, 21.16 feet (13

.06 × 1

.62), is the total loss due to friction in the pipe.

Therefore, dynamic head (static head + friction resistance in the discharge pipe) is equal to 51.16 feet (30 feet + 21.16 feet).

After the dynamic lift (13 feet) and the dynamic head (51 feet) for the pump used in the two previous examples have been calculated, the dynamic column (total column) can be calculated as follows:

dynamic column = dynamic lift + dynamic head

Substituting,

dynamic or total column = 13 + 51 = 64 feet

Since the pressure, in pounds per square inch, of a column of water is equal to head (in feet) times 0.433, the pressure in psi for the previous example is equivalent to the dynamic column (or total column) times 0.433. Thus, 27.7 psi (64 feet × 0

.433) is the pressure of the column of water (

Table 4-5 and

Table 4-6).

Table 4-5 Converting Head of Water (feet) to Pressure (psi)

Also, the head, in feet, of a column of water is equivalent to the pressure, in psi, times 2.31. Therefore 27.7 psi (64 feet ÷ 2.31) is the pressure of the column of water. This value is identical to the result in the previous paragraph.

Table 4-6 Converting Pressure (psi) to Head of Water (feet)

Horsepower Required

The power required to raise a given quantity of water to a given elevation is the

actual horsepower, rather than

theoretical horsepower. That is, the actual horsepower is equivalent to the theoretical horsepower, plus the additional power required for overcoming frictional resistance and inefficiency of the pump. Theoretical horsepower (

hp) can be determined by the following formulas:

or

in which:

gpm is gallons per minute

8 1/3 is the approximate weight of one gallon of water in pounds

62.4 is the weight of 1 cubic foot of water at room temperature

d.c. is dynamic column

To obtain the actual horsepower, the theoretical horsepower can be divided by the efficiency

E of the pumping unit, expressed as a decimal. Thus, the formula can be changed to:

Problem

What is the actual horsepower required to drive a pump that is required to pump 200 gpm against a combined static lift and static head (static column) of 50 feet, if the pump efficiency is 57 percent and the 4-inch pipeline consisting of three 90-degree elbows is 200 feet in length?

Solution

The friction loss per 100 feet of 4-inch pipe discharging 200 gpm is 4.4 feet; therefore, for 200 feet of pipe, the loss is 8.8 feet (2 × 4

.4). The friction loss in one 90-degree elbow is 16 feet; or 48 feet (3 × 16 feet) for three 90-degree elbows. Therefore, the dynamic column is:

d.c. = 50 + 8.8 + 48 + 106.8 feet

Substituting in the formula for actual horsepower:

Summary

The rotary pump is used widely in machine-tool, aircraft, automotive, press, transmission, and mobile-equipment applications. It is a primary source of fluid power in hydraulic systems (see

Figure 4-47).

The rotary pump continuously scoops the fluid from the pump chamber. It is a positive-displacement pump with a rotary motion.

Rotary pumps are classified with respect to the impelling element as gear-type, vane-type, and piston-type pumps. The gear-type pump is classified as to the type of gears used as: spur-gear, helical-gear, and herringbone-gear types of pumps. The two types of spur-gear rotary pumps are the external and internal types.

Rotary vane-type pumps are available as single-stage and double-stage pumps and as constant-volume and variable-volume pumps. In the variable-volume vane-type pump, a pressure compensator is used to control maximum system pressure.

Rotary piston-type pumps are either radial or axial in design. Each pump may be designed for either constant displacement or variable displacement.

Rotary pumps are of heavy-duty construction throughout. These pumps and components can perform satisfactorily at high operating pressures.

The direction of rotation for a rotary pump is usually indicated by an arrow on the body of the pump. The manufacturer’s directions should be followed in determining the direction of rotation for a rotary pump.

A newly installed pump should be operated at a reduced load, gradually increasing to maximum service conditions. Rotary pumps normally require little attention while they are operating. However, most troubles can be avoided if pumps are given only a minimum amount of care, rather than no attention at all.

The size of pump, lift, head, total load, horsepower, and so on, should be calculated for most pump installations. This is important in determining whether the pump is too large or too small—before or after it has been installed.

The dynamic column (total column) must be calculated before the horsepower required to drive the pump can be calculated. The dynamic column is the total of the dynamic lift (static lift + frictional resistance in the inlet piping) and the dynamic head (static head + frictional resistance in the outlet piping) or: dynamic column = dynamic lift + dynamic head

The pressure, in psi, of a column of water is equal to the dynamic column times 0.433. Also, the head, in feet, of a column of water is equal to pressure (in psi) times 2.31.

The theoretical horsepower, plus the additional horsepower required to overcome frictional resistance and inefficiency, is equal to the actual horsepower required to raise a given quantity of water to a given elevation. The formulas for theoretical horsepower are as follows:

or

Actual horsepower can be determined by dividing the theoretical horsepower by the efficiency

E of the pumping unit as follows:

Review Questions

1. How does the basic principle of the rotary pump differ from that of the centrifugal pump?

2. What are the three types of rotary pumps?

3. List three types of gears used in gear-type rotary pumps.

4. What two designs are used for rotary piston-type pumps?

5. How is the direction of rotation indicated on a rotary pump?

6. What is meant by dynamic column or total load with respect to delivery capacity of a pump?

7. Where is the rotary pump used?

8. What does ANS represent?

9. What type of displacement does the rotary pump utilize?

10. Describe the Gerotor’s operation.

11. What is the main favorable feature of a herringbone gear pump?

12. How is the maximum system pressure controlled in a variable-volume vane-type pump?

13. Where is the pintle located in a variable delivery radial piston-type pump?

14. What type of construction is utilized in making a pump to move barium chloride?

15. Why is a steam chest used on a rotary pump utilized in steam and hot water pumping?

16. Are rotary pumps smaller or larger than centrifugal pumps?

17. Can a flexible coupling compensate for incorrect alignment between the pump and its driver?

18. What is the most common drive for rotary pumps?

19. What causes noisy operation of a rotary pump?

20. How do you obtain the actual horsepower needed to raise a given quantity of water to a given elevation?