Do you ever wonder why you bother with annual performance appraisals because you seem to be saying the exact same thing year after year? Have you wondered why your team don’t quite do what was agreed, even when you feel you made things absolutely clear? Are you frequently confused by the behaviour displayed by key personnel? Have you ever spent a small fortune recruiting the best and the brightest talent you can find, only to be disappointed with a lack of transformation, growth or new ideas they bring? Are you frustrated by the lack of execution in the business? Is there a constant discrepancy between what is supposed to get done and what actually gets done? Are you confused at the inconsistency of performance or output in your business? If so, you’re not alone.

We have been taught that success is the ultimate prize – the final destination. All our life we’ve been encouraged to play by the rules, get a good education and march relentlessly up the corporate ladder. We work hard, put in long hours, and if we are lucky, smart or both we ‘arrive’. But during it all performance seems erratic. We recruit expensive talent to unlock performance but it doesn’t always work. We incentivize, we coax, we remind and we threaten but performance remains hit and miss. We hire performance gurus and consultants to unlock the secrets but still nothing much changes.

Even when we know that something isn’t working we stick to the same course, because often we just don’t know what else to try. If we look at the banking crisis for example, there is now a mountain of robust evidence that proves that the bonus culture is toxic (Ariely, 2008, 2010). It doesn’t work and it caused or at least massively contributed to the biggest financial collapse since the Great Depression, and yet as soon as the dust settles it’s ‘business as usual’ for banking. To paraphrase Einstein, we are insane – blindly doing the same thing and expecting a different result. As a consequence there are many well-informed individuals who believe that the next financial crisis is just around the corner (Taleb, 2007; Martin, 2011).

The purpose of doing anything is to generate better results: better results for yourself, your team, your family or better results for your organization. If we want to generate better business performance, physical performance, relationship performance or academic performance, we need to make the right behavioural choices. So it all starts with behaviour. This is why large sections of society, be they business, education, health or crime prevention, put so much emphasis on behaviour (and correcting behaviour) because we believe that behaviour determines the results we get in life.

As a result, the 20th century has been completely preoccupied with behaviour. If performance and results are not as good as we hoped, then behaviour is almost always considered the ‘problem’ that needs fixing. This seems like a logical argument; after all, what we do determines the results we get. But if results are still inconsistent and performance is still erratic then something is clearly missing from our understanding of what drives behaviour in the first place.

In working with global CEOs and leaders since 1996 one thing that has become very apparent is that most executives can perform really well sometimes, but being brilliant every day is much more difficult. In sport this is often referred to as a ‘loss of form’. As Sergio Garcia and many other sportsmen and women have discovered, this loss of form is thought to be something of a mystery. It is accepted as a normal cyclical part of elevated performance that just has to be tolerated because it can’t be controlled. And certainly if we don’t know how we are producing our brilliance, then delivering it day in day out, week in week out is obviously going to be elusive, maybe even impossible.

If we only focus on behaviour we will experience a variance in the results and we may never know why. Achieving sustainable, consistently brilliant results therefore requires a much more sophisticated approach. It requires us to look underneath the behaviours to what is really driving them, namely what we think, what we feel and the amount of energy we have at any given time. And that’s what the previous three chapters have focused on.

In unpacking all the levels of the human system of physiology (‘Be younger’), emotions and feelings (‘Be healthier and happier’) and thinking (‘Be smarter’) and exploring how they interact, we can begin to appreciate why performance and results are often so difficult to predict and why they seem so arbitrary and mysterious.

These insights also allow us to make sense of some of the more unfortunate business phenomena and their inherent dysfunction.

The boss who demands results

A client of mine, let’s call him Trevor, was the head of an international business unit in an organization going through a period of significant change. An internal reorganization meant that Trevor was now reporting to a new boss, we’ll call him George. George was a very seasoned, widely respected main board member of a well-known multinational organization. George’s own role had recently been extended to give him greater accountability for a much larger piece of the business. An emergency meeting was scheduled between George and his new extended team of senior executives to review the budgets that each executive, including Trevor, had submitted to him the week before. Trevor was expecting to hear George’s views on how they were going to improve the performance and some directional statements about how George saw his expanded remit and what that would mean for each member of the executive team.

It was clear from the outset that the team was in for a rocky ride. George arrived with a face like thunder. He slung the budget documents back to each of the executives like a teacher returning failed term papers to poorly performing students. Virtually everyone in the room got an ‘F’. The boss then proceeded to dissect each person’s numbers in front of the rest of the team, picking holes in the cost base, ridiculing the margins and attacking what he saw as a lack of ambition or ability in the sales projections. After a gut-wrenching hour of George extracting all manner of bullets from the spreadsheets and firing them at virtually everyone in the room George said:

Frankly your performance is useless. We pay you folks an awful lot of money to deliver results and your numbers are a mess, they don’t add up and they are just not good enough. You all need to redo the work and come back to me with a number that I can take to the board at the end of the month. I don’t care how you do it, I just want you to improve the numbers. You’ve got a week.

Unfortunately such leadership behaviour is not unusual. Leaders are accountable for delivering results, and this relentless pressure often results in aggressive behaviour and an excessive focus on financial data to the exclusion of all else. Sadly, similar exchanges between leaders and their teams occur thousands of times a day in corporate meeting rooms around the world.

The coach who doesn’t coach

I encountered the exact same phenomenon in the world of sport. A Premiership footballer I know was taken aside by the first-team coach during pre-season training. He was told, ‘OK, what I need from you this season is more goals. Your main priority is to score more often and I want you to focus on that.’ When the player asked, not unreasonably, if the coach had any views on how he might actually score more goals the coach replied: ‘It doesn’t matter how you score them so long as you do.’

The coach worked every day with the team on various moves on the pitch, set-pieces and tactics; collectively they worked hard on fitness and there was a good camaraderie in the squad. But the sum total of the input to the striker on an individual basis was that single conversation. The player was so disappointed by the lack of sophistication in seeking to actually help him become a better player that he started to fear that he would not develop as a player at the club.

The above examples are typical of the approach many companies and their leaders take to the issue of performance. Whilst there may be a preoccupation with results there is very little discussion, support or coaching about how the required results might be achieved. Asking for better performance, or even demanding better performance, will not necessarily deliver better performance. That is only possible when we appreciate the elements that contribute to elevated performance and systematically bring those elements under conscious control.

Performance appraisal

Most managers have already realized that changing people’s behaviour is not easy and that people do not necessarily do the right thing even when they are told what the right thing is – a reality that becomes painfully apparent when they do their team members’ annual ‘performance review’. The conversation typically focuses on their direct reports’ behaviour and fluxes between what the employees did in the previous year that was good and what they did that was not so good. The manager then encourages his/her reports to do more of the former and less of the latter. There is an assumption that this conversation will actually be helpful. Often it makes little difference. The reason that performance reviews often have limited impact is that the way employees react after the review is not based on whether they know what is expected of them; it is based on what they think and feel about what has been said in the review and what is expected of them.

For many companies the performance appraisal process is nothing short of a debacle. I remember speaking to one client who reported that her annual appraisal had been conducted as an informal chat between the courses of the in-flight meal on a business trip to Europe. She was shocked to hear, at the end of the flight, that her appraisal process had been completed successfully. She was unaware that it had even started.

Even the slightly better examples, where the boss had taken the trouble to gather 360° feedback, often ended up being a discouraging review of what the employee had not done well over the past 12 months. If anything was said about what they had done well, it was normally glossed over and the focus returned to what needed to be done differently, ie what new behaviours were required to improve performance.

Unfortunately, most leaders attempt to improve performance by focusing on what someone is doing wrong and what behaviour needs to change. But we already know that making someone change their behaviour is very difficult and behaviour change is rarely sustained (Buckingham and Coffman, 1999). In addition, as we’ll explore in more detail later in this chapter, correcting the wrong behaviour never produces success, it only stops failure. So the obsession with behaviour seems a little misguided!

In order to ensure that the results are delivered, leaders will often try to enforce certain behaviours by way of authority or micro-management. It is, of course, possible to get people to do what we want them to do while we are standing over them and checking up on them. But what happens when we leave? Chances are our people will do what they want to do and may even do the exact opposite of what we want just to annoy us!

Obsession with results

In modern business and life in general, results, particularly financial results, are the primary measure of worth. This obsession has created several unintended consequences born of the ethos that no achievement or advancement is ever enough.

The World is Not Enough may be the title of a James Bond movie but this notion is also deeply embedded into our personal and professional lives and it goes a long way in explaining our obsession with performance and results. As Mike Iddon – Finance Director for Tesco UK and one of the most perceptive FDs in the FTSE – explains in his case study at www.coherence-book.com, this ‘not enough’ mindset can have serious negative consequences on teams and the business:

[Delivering] bad news creates a drop in energy levels. I felt it too. I was almost taking the blame for any missed figures myself. With new framing, we delivered a more positive contribution and could start to figure out why the numbers were as they were. This has an effect on the energy levels in the team, but it also changed the belief structure. People had previously lived with a ‘not enough’ mindset; their emotional state was very much aligned with the day-to-day performance of the business. A change in this perspective helped us towards a goal of more self-belief.

As Mike and many of us experience on a day-to-day basis, we have to get more, we have to be more. There is now a relentless, restless drive for more, bigger, better, higher, faster, stronger; this pervades many lives and many businesses. Growth is the goal, and volume, size and scale are the main markers of greatness. Quality, value and meaning are subordinate. Bigger is better and the bar is set higher and higher. Cheaper is rarely challenged as a commercial target. If we are not delivering cheaper, bigger, more for less, we are not performing well enough, are somehow deficient or ‘not enough’.

The first thought on waking up for many busy executives is: ‘I didn’t get enough sleep.’ This is replaced by other thoughts and feelings of insufficiency: ‘there aren’t enough hours in the day’; ‘I am not earning enough money or being paid enough’; or ‘my career is not progressing fast enough.’ A common fear of many is that they will be ‘found out’ and they are ‘not good enough, smart enough or able enough’ to do the job they are doing (Brown, 2013).

The mindset of ‘lack’ may relate to a leader’s team or organization: ‘I can’t find good enough people’; ‘my team isn’t skilled enough’; or ‘this organization isn’t ambitious enough.’ The thinking may relate to customers: ‘there aren’t enough customers’; or ‘the customers aren’t loyal enough.’ Even people we might think of as very successful often aren’t satisfied. A very successful businessperson might frequently think their business should be more profitable, or growing more quickly and earning more money.

Business can, particularly in tough economic times, become a grown-up version of musical chairs. Executives can become very focused on securing their slice of limited resources. So everyone keeps busy doing their thing, wondering when the music might stop and if they will need to shove others out the way to ensure their corporate survival and provide for their families. The rules of the game have changed, which now means that leaders often fight to get to the top, cling on there for a few years while they ‘build their stash’, only to be fired when they can’t deliver the excessive promises they themselves had almost been encouraged to make in order to secure the position in the first place.

Because the pecuniary prize of reaching the C-suite is now so great it can, even in the most saintly organizations, foster a culture of greed and aggression as well as an erosion in humanity.

For example, I recently spoke to a very senior executive who had given 20 years’ loyal service to one company and had created a world-leading business unit in her area. Unfortunately she refused to play the politics that were rife at the top of this particular organization, as they are in many companies. So when a new boss was appointed over her, she shared her thoughts about him with him after being encouraged to do so in a poorly facilitated ‘team away-day’. A couple of weeks later she was summoned to the boss’s office, informed she was surplus to requirements and told she would be escorted from the building.

When she asked if she could go back to her office to ‘get her things’, she was told she could not. When she asked what she should say when her PA called her to ask where she was, her boss said she should ‘not answer the phone’. In fact the boss said: ‘We want your phone too.’ And, the group HR Director sat with the boss throughout this entire exchange and said nothing.

When we hear such stories we wonder what has happened to the humanity of the people dishing out such news. We seem to have created a system that is set up to promote aggressiveness and hubris instead of teamwork and elevated collective performance. There is little doubt that our overt obsession with results has fuelled this ‘never enough’ mentality which in turn has contributed to the erosion of humanity and the creation of a culture of greed and entitlement so often experienced in modern business and society as a whole (Rowland, 2012).

And the really disheartening part to all this is that the ‘not enough’ mindset actually renders the results irrelevant, because no matter how great the growth or how amazing the like-for-like results – they will never be enough. Plus, to make matters worse, our obsession with results doesn’t actually work! Our singular focus on behaviour and results isn’t actually improving behaviour and results. In fact it’s often making them worse. The only way to deliver a sustainable improvement in results is to have a much deeper understanding of the real drivers of performance and what impairs it.

In 1908 two scientists called conducted a series of experiments with ‘dancing mice’ (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908). They put mice under pressure and assessed how well they performed. This was achieved by heating the floor of their cage (hence ‘dancing mice’) to see how this affected their ability to perform. Yerkes and Dodson were able to demonstrate a clear and definitive relationship between pressure and performance that has stood the test of time. Since then, this relationship has also been verified for people, computers, complex systems and corporations – as well as mice.

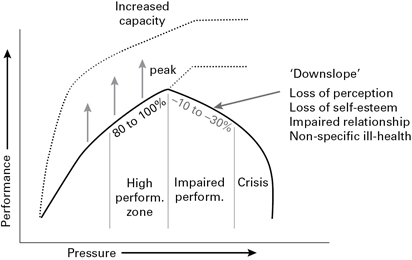

This is not really surprising, and when asked to describe the relationship between pressure and performance most people can accurately describe how one affects the other. Most people know that pressure improves performance up to a point and then impairs it (Figure 5.1), and yet few managers, leaders or organizations apply these lessons to their own lives, teams or companies.

FIGURE 5.1 Pressure–performance curve

We all need some pressure or ‘stress’ in our lives in order to perform well. This is why many of us work well to deadlines. This is the healthy ‘upslope’ of the performance curve and it is often referred to as ‘good stress’. However, if we become overloaded with an increasing number of tasks, conflicting deadlines and escalating pressure, eventually we will ‘peak’ and find our limit. The top of the performance curve or ‘peak’ forms an apex because most of us can pinpoint when we are working at our peak. This is our ‘peak performance’ and represents the physical limits to how much we can do in one day.

So if we’re working flat out at or near our peak and somebody asks us to do an additional task, our performance cannot improve any further. All that happens is the pressure increases and performance declines.

When we are overloaded, (or we overload others), performance doesn’t plateau, it actually gets worse. We might think our performance is tracking upward along the first dotted line in Figure 5.1 but it’s not. We have crossed a threshold and entered what we call the ‘downslope’. In the early days of impaired performance we may not even notice that we are starting to underperform, partly because the gap between what we intend to do and what we are actually doing is small. In fact most people don’t know that their performance has become impaired until they are a significant way down the downslope.

Of course, once we realize there’s a gap between our actual performance and our expected performance that often makes us feel dreadful and pushes us further down the downslope.

Getting the balance right

Underperformance in any organization is due either to insufficient pressure or, much more commonly, too much pressure. Unfortunately the commonest organizational response to poor performance is to ‘flog it harder’, ie increase the pressure and demand even more by putting more pressure into the system or onto the person. This approach simply exacerbates the problem and drives the individual or team towards failure even faster.

It is therefore vital that we all understand where we are on the performance curve and how to get the balance right, for both ourselves and our people. Too much pressure results in impaired performance and too little pressure results in sub-optimal performance. Most people in organizations live their life on the downslope because there is too much pressure in the system.

Part of the problem is that in business we demand, ‘110 per cent or 120 per cent effort’. People who make such demands are simply revealing how little they know about performance. It’s not possible to deliver a 120 per cent effort and such exhortations ultimately do nothing but perpetuate the ‘not enough’ mentality.

Any athlete will tell us that it is impossible to perform continuously at 100 per cent. Most elite athletes work on the healthy side of the performance curve at 80–85 per cent of maximum capacity. This is what enables them to raise their game for competition. Leaders, senior executives and teams need to be doing the same – leaving some spare capacity for a crisis or a busy time of year.

If we put too much pressure on ourselves or our team then our performance will tail off until eventually we can’t perform at all. Often this can happen when there is just too much on someone’s plate and too many equally important competing priorities. As a result one of the most productive leadership interventions is to narrow the focus by clarifying and simplifying everything. Warwick Brady, the COO of Europe’s leading airline easyJet, used this approach to transform easyJet’s performance and improve employee morale. EasyJet is Europe’s leading airline, operating on over 600 routes across 30 countries and serving around 59 million passengers annually. The company employs over 8,000 people, including 2,000 pilots and 4,500 cabin crew, and has a fleet of over 200 aircraft and as Warwick explains:

Day-to-day delivery was poor, customer service was low and the business was struggling to control costs. This all culminated in a collapse of performance in summer 2010. The number of easyJet planes arriving on time dropped to around 40 per cent. Gatwick Airport published the league table of airline on time performance (OTP) and easyJet came out below Air Zimbabwe – a fact shared with the wider world when Ryanair, a main competitor, used it as a headline in a national newspaper advertisement… The company was not in good shape. I stepped into the COO role in October 2010. What I found was a team of people who had worked really hard for three to four years with little to show for it. For many it had become embarrassing to work for easyJet – performance was poor and everyone knew it… I had a lot to sort out. Despite the apparent scale of the turnaround required, I decided we needed to really focus and fix just one thing: OTP. We needed to keep safety where it was, but essentially we had to fix OTP, that’s it, nothing else. The only way to achieve that goal was to work together as a team on that single focus… It worked. Within six months, we had stabilized the operation… Within 12 months we had not only fixed the problem, we had become number one in the industry for OTP. We had fixed the core. Our customers could trust that we would get them to their destination on time. Our crews could trust that they would be able to get home on time after their shifts. Today my top team is predominantly made up of the same people as it was back in the dark days. We went from being the worst-performing airline to being the best. Now the team is well respected and operating like a well-oiled machine. All of this was down to the singular focus on OTP and our teamwork.

Having achieved such a dramatic turnaround in performance, his team have gone further still by implementing a step-change to their meeting process, focus and discipline. This included reviewing all non-critical projects and literally stopping work to enable other projects to really succeed. Getting executives to stop doing things was quite a performance breakthrough. Warwick explains how that was achieved in his case study detailed at www.coherence-book.com. Chris Hope, Warwick’s Head of Operational Strategy, also provides details of how the team moved beyond an operational focus to implement better quality governance within the team.

When it comes to performance there really is no need to overcomplicate the agenda. When a leader reduces the pressure the performance will often improve immediately without any other intervention being required. Therefore one of the most important responsibilities of a leader is to keep it simple and keep it clear. Getting the balance of pressure right is absolutely crucial for any leaders who are interested in increasing their own, their team and their organization’s results.

Living on the downslope

What happens to many individuals and teams is that they slip onto the downslope and don’t even realize they are on the wrong side of the performance curve. In fact many leaders don’t notice anything is wrong until things reach a crisis point.

This inability to step in early enough is particularly dramatic in healthcare systems, where we often chart the downward progress of an individual and wait until their health has collapsed before we intervene. Intervening after things have imploded or failed is much harder and more expensive, and the patient takes a lot longer to recover. It would be much wiser to intervene at the beginning of the downslope when things are more easily reversed. This highlights a fundamental principle – if we want to get things working properly, early detection of underperformance or ‘loss of form’ is crucial. If action is only taken once the system has failed then it will be extremely costly and recovery may even be impossible.

The more perceptive we are, the sooner impaired performance will become apparent and the sooner we are able to step in and reverse the trend. Without that expanded perception and awareness of the performance curve we will simply drive harder and shout louder, which often brings about the very thing we are trying to avoid. When we ramp up the pressure we simply accelerate and accentuate the loss of form, which can in turn create real performance and safety problems. If left unchecked, the highly pressurized individual will slide all the way down the downslope toward serious health issues and breakdown. So if we don’t want to keel over at our desks, have a heart attack or stroke and we don’t want any of our team to suffer the same fate, then we must appreciate the signs and signals of the performance curve and remove pressure instead of adding to it.

There are several key signs and signals that can tell us if we, or our people, have been tipped from peak performance into the downslope. The first is loss of perception. Most people don’t even realize they’re on the downslope. In fact when challenged they normally deny there is anything wrong. They just don’t see their predicament. Remember the bank CEO I referred to in Chapter 3, who refused to believe there was anything wrong with his ability to foresee the financial crisis and lost his job as a result. The reality was that a number of economists told the G7 leaders that the financial tsunami was coming but leaders in the industry either didn’t understand or didn’t want to believe it (Lewis, 2010).

There are also valid and relevant neuroscientific reasons why there is a loss of perception, as discussed in the previous chapter. When we are under pressure, the physiological signals generated in our body – particularly from our heart – create an incoherent signal that causes a DIY lobotomy. Unfortunately, without access to our frontal lobes and the full depth and breadth of our own intelligence and cognitive ability, our perceptual awareness is seriously impaired. In addition to a loss of perception there is often a loss of self-esteem and irritability, and all this can lead to impaired relationships.

Another tell-tale sign of the downslope is non-specific ill health. People on the downslope may wonder if they should ‘go to a doctor’. Unfortunately doctors are trained to spot pathology and the early detection of dysfunction or instability before pathology occurs is not really part of their training. As a result the doctor will often dismiss the symptoms because there is nothing ‘specifically’ wrong.

Actually it is these non-specific things that doctors should all be paying much more attention to. These are the early warning signs of a destabilized system and the precursors for major disease and ill-health. When things are just mildly dysfunctional and we’re not quite sure what is wrong that’s exactly when we should be paying the most attention, because these are the early and highly reversible signs of poor performance and ill-health.

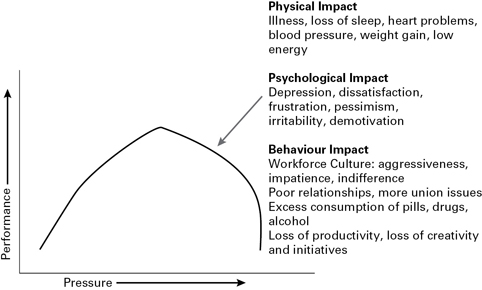

Left unchecked, more obvious psychological issues such as depression, dissatisfaction, frustration, pessimism, agitation and demotivation start to occur. These create behavioural problems in the workforce, poor relationships at work, excessive union issues, reduced productivity, impaired or absent creativity, increased aggressiveness, impatience or indifference. Ultimately the non-specific health issues such as low energy, poor sleep and weight gain will give way to more obvious conditions such as heart problems, high blood pressure and infections. The increased consumption of pills and alcohol is also a clue that we are on the downslope.

In addition to the impairment of individual performance and health, there are organizational costs to being on the downslope. At the team level, poor system health would be indicated by poor interpersonal dynamics and frequent ego battles. At the business unit level, poor health could be indicated by an unhelpful culture. At an organizational level, it would manifest itself as tribal behaviour and turf wars (Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.2 Individual impact of excess pressure

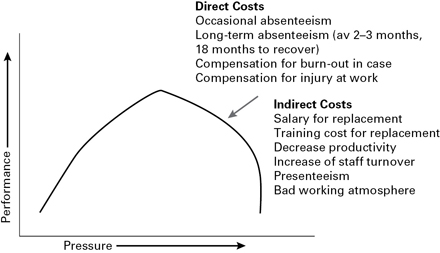

Absenteeism is likely to rise because people are demotivated. This can drift into long-term absenteeism and ultimately increased compensation claims against the business for ill-health or injuries at work. Such activity also has indirect costs in terms of salary replacement and increased head count required to cover the absence. Staff engagement can be stubbornly resistant to change leading to perpetually sub-optimal performance (Figure 5.3).

FIGURE 5.3 Organizational impact of excess pressure

If we want to increase our own or our organization’s performance we will need to increase our own and other people’s capacity. This can only be done effectively from the healthy side of the performance curve.

The Enlightened Leadership model unpacked

Having introduced the Enlightened Leadership model in Chapter 1, it’s now time to unpack it in much more detail because it is this model that explains why we are not getting the results we want, despite our very best efforts.

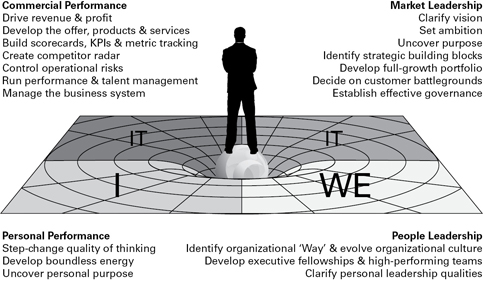

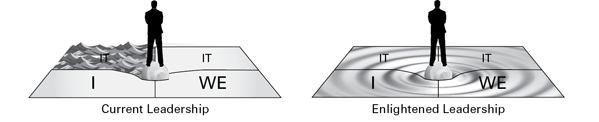

Adapted from Wilber’s ‘all quadrants all levels’ (AQAL) model (Wilber, 2001), which seeks to map how the world and the individuals in it really work, the Enlightened Leadership (Figure 5.4) model focused exclusively on how business and the people within business work.

FIGURE 5.4 The Enlightened Leadership model

Like the AQAL model, the Enlightened Leadership model describes how there are three perennial perspectives that a leader can take, and they are present in every moment of every day. The third-person perspective is the objective, rational world of ‘IT’, ie what ‘IT’ is that we need to do to make this business work. The second-person perspective refers to the interpersonal world of ‘WE’, ie how ‘WE’ relate to each other in a way that impacts how the business performs. And finally the first-person perspective is the subjective inner world of ‘I’, ie what ‘I’ think and feel about the business and the people that impacts how well the business works.

In order to make the model more business and commercially relevant we simply rotated Wilber’s AQAL model anti-clockwise and placed the individual at the centre, looking forward into their rational objective world. By doing so, leaders can immediately see their business landscape depicted in a practical and powerful intellectual framework that can help them better understand the breadth of the challenges they face.

The simple reality of modern business is that we stand in the centre of our own life looking forward, and the reason we are not getting the results we want despite our best efforts is because we rarely see what’s behind us (‘I’ and ‘WE’). Instead we are predominantly focused on the ‘IT’ – especially the short-term ‘IT’, which takes up anywhere between 80 and 95 per cent of our time. And unless we realize that our efforts in the rational, objective world are built on ‘I’ (physiology, emotions, feelings and thoughts) and that the success of what we want to build requires our connectivity at the interpersonal ‘WE’, then there is no solid foundation on which to build outstanding effectiveness in the solid, rational world.

As I write this in 2013, the game of business is set up to demand almost exclusive attention on the short-term ‘IT’ in the drive for quarterly results and shareholder value. Leaders may, if time permits, also focus intermittently on strategic issues. And while many may appreciate the importance of ‘WE’, understanding the relevance of culture, values and relationships and doing something effective about them are often two very different things.

And as for ‘I’, very few leaders spend any time thinking about their own awareness or their own individual development, the quality of their own thinking or their energy levels. And virtually no one ever thinks about their physiology, other than to notice they are exhausted. These perspectives are rarely discussed in business; they are almost never taught in business schools and hardly ever appear in management and leadership journals. And yet, at Complete Coherence we believe that it is the long-term ‘IT’, the interpersonal ‘WE’ and the ‘I’ that hold the key to business transformation and rewriting the rules of business.

To be an Enlightened Leader we have to be aware of and develop in all four quadrants simultaneously. We must cultivate our self-awareness; we have to develop much better interpersonal skills and we need to build the business for today and tomorrow. There are very few leaders who are outstanding in all four quadrants. The handful of truly world-class leaders are characterized by their ability to move effortlessly between, and be coherent across, all of the following four quadrants.

Personal performance: the subjective, inner world of ‘I’

If I was to summarize virtually all leadership books into one phrase it would be: ‘Be yourself.’ Whilst it is true that the leadership journey starts with ‘I’, it is also true that most leaders have not studied and do not have a detailed understanding of what ‘I’ or the self really is. So whilst leaders might understand intellectually the notion of authenticity, very few, through lack of time or inclination, spend any time reflecting on the ‘I’ quadrant or thinking about who the person is that is turning up each day to do the doing.

As I said earlier, this isn’t that surprising considering that leaders are almost entirely focused on looking forward and they rarely look back over their left shoulder to the inner personal world of ‘I’. Leaders are therefore encouraged to be themselves but given no time or intellectual framework to even consider who they are and what really makes them tick.

Much of what we have covered so far – physiology, emotion, feeling and thinking – seeks to provide that necessary intellectual framework so as to foster a much more sophisticated appreciation of what’s really driving leadership behaviour and personal performance in the ‘I’ quadrant.

People leadership: the interpersonal world of ‘WE’

Behind the leader’s right shoulder is the interpersonal world of ‘WE’ – which will be discussed in greater detail in the next chapter. Obviously, successful leadership requires followership, so how a leader interacts with others is critical.

People interactions occur at three levels of scale for every leader – one-to-all, one-to-many and one-to-one. At the highest level the leader is the single biggest determinant of organizational values and culture (one-to-all.) The leader’s impact (or otherwise) is then determined by their ability to work effectively through the executive teams around them (one-to-many). The ability to build and bind teams together is therefore critical to organizational success, yet working their way up through the commercial, financial, operational, marketing or legal ‘ranks’ doesn’t necessarily train a leader in the ability to build and bind teams successfully. It is often simply assumed that a leader can do this, will work it out or it’s left to chance. Finally, a leader’s ability to develop and nurture productive relationships with staff and stakeholders is also vital (one-to-one). How a leader shows up with every person they encounter determines their personal leadership brand and influence. Most leaders have not spent much time thinking about their own personal leadership qualities, their personal brand or how genuinely influential they are.

Both ‘I’ and ‘WE’ are aspects of reality that are not usually that visible. Most business leaders don’t consider the invisible internal aspects of ‘I’ and don’t think that much about ‘WE’ because they are fully committed to the visible, external and objective world of ‘IT’ – the business. So despite many leaders claiming that ‘people are our most important asset’ they focus most of their time and attention on operations and finance.

I asked a CEO recently: ‘If people are your most important asset why don’t you spend most of your time with your Human Resource Director (HRD)?’ ‘Well,’ he responded, ‘Because the guy is an idiot!’ This is a classic example of actions speaking louder than words. If that same CEO thought his Finance Director or his COO was an idiot they wouldn’t survive five minutes because finance and operations are seen as absolutely vital to success. The fact that he thought his HRD was an idiot and the guy still had a job demonstrated very clearly just how important he really considered the people agenda to be.

When we interviewed Nick Warren, one of the boldest and most innovative HR specialists in mining and Head of Development for First Quantum Minerals Ltd, he explained what’s really possible when people leadership is considered important. First, Quantum Minerals is an established and rapidly growing mining and metals company producing copper, nickel, gold, zinc and platinum group metals across several mines worldwide, and as Nick explains:

We’ve really committed to people development in a practical way. We wanted it to become a normal part of our culture. A few years ago we started a graduate programme, which is not unusual in itself, but the real reason we did it was to give people-management responsibility to every manager in the organization. Each manager now has at least one graduate that they need to develop. While the graduates come with academic qualifications, they need to be developed and the managers take up that responsibility. Initially there was some resistance, but the managers soon saw the benefits of developing talent within their team and it has resulted in managers not just developing their graduates but other employees as well. In this way, we’re building a culture of people development.

Market leadership: the future world of ‘IT’

Driving an international business is very complex and intensely pressurized, so most leaders spend their time looking forward and only forward. Our top right quadrant, or front, forward-facing right, is the long-term ‘IT’ (see Figure 5.4). Here the leader is focused on ‘what’ ‘IT’ is that needs to be done, and the emphasis is on the future and how to create the future. Even though business leaders the world over know that the long-term picture is important, few get out of the ‘weeds’ of the day-to-day so they can focus on the other three quadrants. However, the greatest businesses spend just as much time building the future as they do managing the present.

As I already mentioned in Chapter 1, most businesses struggle to build their own future because they have not clearly differentiated the key concepts in the top right quadrant. In the absence of detailed training in strategic thinking, many companies outsource this to a strategy house that then delivers some detailed market analysis and some commercial options. As a result, the internal strategic thinking capability in many organizations remains underdeveloped or largely absent. The lack of high-quality strategic thinking or a strategic development process has a knock-on effect impairing growth and innovation. Insufficient detail on the scale of the ambition can make it very difficult for the CEO to make effective calls at pace, especially when those speedy decisions require a sense of urgency to be injected into the organization. The absence of an effectively articulated purpose can set in stone intractably low levels of employee engagement. A poorly defined vision confuses the customer and adds to the low engagement levels internally. Finally, massively inefficient governance dramatically slows down decision making and burns a huge amount of executive time in laborious meetings that don’t take the organizational performance forward.

Quality focus on all these areas of market leadership can create ‘clear blue water’ between your business and your competitors. So despite there probably being more competitive advantage to be had in the upper right quadrant than the upper left, many leaders find it immensely difficult to stay focused on anything other than the immediate and the short term. This problem is exacerbated by the volatile market conditions that create uncertainty and more insecurity.

Commercial performance: the here and now world of ‘IT’

This quadrant is concerned only with the short-term ‘IT’ of money, profit, costs, product, service, marketing, business model, performance management systems, like-for-like sales comparisons and success metrics. The short-term ‘IT’ is purely focused on today and the quarter-by-quarter battle. We’ve talked to over 450 global CEOs and it’s clear they spend most of their waking hours consumed by thoughts of ‘what’ ‘IT’ is that needs to be done now.

Short-term results are absolutely critical, not just for an individual career but because if leaders don’t deliver today then they won’t get permission to even explore the potential that lies dormant in the other three quadrants. The irony of this scenario is that the big commercial wins are virtually all to be found in those other three quadrants. It is, after all, difficult to outperform the competition just by having a tighter grip on the day-to-day metrics. But getting really tight cost control, driving down suppliers and squeezing the operation for maximum efficiency, measured via a myriad operational metrics, KPIs and ‘steering wheels’, is the standard combination a CEO employs to try and deliver shareholder returns.

While such a grip will always be necessary in the absence of activity in the other quadrants, it often creates a dry business seeking to grind out a result. Such organizations are often not that exciting to be part of, and over the long term morale suffers, talent becomes increasingly difficult to attract and keep, leading positions are eroded and eminence is lost.

Leaders need to focus on building a business system that works independently of their own efforts. If they do not free themselves from the day-to-day operational focus, then they are probably just managing the business, not leading it. So the challenge for most leaders is getting out of the tyranny of ‘today’. The simple reality is that until leaders start to make themselves redundant in that top left-hand quadrant it is very difficult to effectively lead the business.

Enlightened Leadership only really emerges when leaders operate coherently in all four quadrants (Figure 5.5).

FIGURE 5.5 Current incoherent leadership vs coherent Enlightened Leadership

Making the transition from managing the business to genuinely leading the business by not managing it is a very difficult step for most leaders. The comfort zone for many is to continue to focus on task and driving the short-term result. Management is mainly about the top left-hand quadrant whereas leadership is really about the other three quadrants. Management is about doing, whereas leadership is more about being. And who you are being often comes down to maturity. It will therefore come as little surprise that one of the key lines of development for an Enlightened Leader is maturity. Research has shown that leadership maturity can predict the ability to drive organizational transformation (Rooke and Torbert, 2005). There are a number of academics who have written and researched adult maturity and they have identified a number of stages of adult development. However, like so many of the insights shared in this book, adult development theory has until recently largely remained in the ivory towers of academia and has not made the transition into the places where those insights could really make a difference.

One of the most widely used descriptions of adult development, which we explored in detail in Chapter 4, is Ken Wilber’s ‘integral frame’, which describes the 10-stage evolution of the self. Other academics such as Susanne Cook-Greuter, Robert Kegan, Bill Torbert and Elliot Jacques have also all described different aspects of adult development. The research of each of these academics has something very useful to offer leadership development and yet it is surprising how few HR directors or leadership ‘experts’ have even heard of, let alone studied, their work.

Kegan, for example, provides some very valuable insights on the relationship between subject (the world of ‘I’) and object (the world of ‘IT’) and how this impacts the way we create our own destiny.

Of all the academics involved in this area Cook-Greuter, who has spent 45 years researching ego maturity, offers some extremely valuable insights into how this plays out in organizations. Her work provides a useful theoretical explanation for boardroom battles, the ‘political manoeuvring’ that so often occurs at the top of organizations and can distract leaders from building a great company and delivering results. It explains why leaders keep coming up with the same set of answers to the same set of problems. Specifically, her work adds real value and deepens our understanding of Wilber’s description by providing greater differentiation of the transpersonal level by defining three additional stages of development within this level. These additional distinctions go right to the heart of the leadership debate and why so many leaders struggle with the VUCA challenge.

Bill Torbert explores adult maturity from the perspective of what drives action (called Action Logic) in a business setting. His descriptions of how the various stages play out in business are perhaps the most immediately recognizable to leaders. Torbert and Cook-Greuter have collaborated extensively in bringing this incredibly insightful topic into the business domain. The labels Torbert uses to describe the levels of maturity, especially the three critical ones identified as being the ‘centre of gravity’ for most businesses, are a little more accessible than Cook-Greuter’s descriptors.

We will largely use Torbert’s labels with some minor modifications to try and make the key levels more comprehensible. Torbert identifies the three key levels seen in business as Expert, Achiever and Individualist.

Maturity theory is a slowly emerging but profoundly insightful and practical framework for understanding much of the dysfunction within modern business (Table 5.1). As I said in the previous chapter, when leaders understand the characteristics and behaviours associated with each level of adult maturity and how that manifests in business, they are often immediately able to identify the maturity level of the other people in their team. As a result the maturity frame can often shine a light on why their team isn’t working well or why it may be stuck and, perhaps most importantly, what to do about it.

TABLE 5.1 The levels of leadership maturity

|

Descriptor |

Level |

|

10. Unitive |

Post-Post-Conventional |

|

9. Magician |

Post-Conventional |

|

8. Integrator |

Post-Conventional |

|

7. Individualist |

Post-Conventional |

|

6. Achiever |

Conventional |

|

5. Expert |

Conventional |

|

4. Conformist |

Conventional |

|

3. Self-serving |

Pre-Conventional |

|

2. Impulsive |

Pre-Conventional |

|

1. Undifferentiated |

Pre-Conventional |

The majority of academics writing about adult maturity largely agree that the most important step-change waiting to occur in the development of leaders globally is the leap from the ‘conventional perspective’ to the ‘post-conventional perspective’. Leaders who approach the world from a conventional perspective, which according to Torbert is at least 68 per cent of all leaders (Rooke and Torbert, 2005), are focused on knowledge. In contrast post-conventional leaders are starting to differentiate and understand the critical difference between knowledge and wisdom (Kaipa and Radjou, 2013). I don’t just mean this as an intellectual distinction but in terms of how it plays out for their organization and their organization’s role in the world.

Torbert described how the conventional-level leaders have been promoted up through the ranks by being very proficient in a particular set of skills, but this proficiency did not automatically equip them to lead a business. And considering that the vast majority of learning and development (L and D) in any business is predominantly focused on the L with no real D, these individuals find themselves in ‘over their heads’ (Kegan and Lahey, 2009). And that is not good for either the individual or the business.

Conventional leaders like to know more and do more. As they move up the three levels of conventional thinking they develop an increasing ability to differentiate, and this is a sign of their development. They like to predict, measure and explain the world. This enables them to see ahead and they also like to look back in time to discover patterns, rules and laws at play. They notice more and appreciate more pieces of the puzzle, and this is what enables them to succeed.

In contrast to conventional leaders post-conventional leaders like to strip away illusions and see a deeper reality. As they move up the three levels of post-conventional thinking they develop an increasing ability to integrate the knowledge and wisdom they have accumulated, which is in and of itself a sign of their development. They prefer to approach issues without a preconceived idea of the answer. They take a much more holistic dynamic-system approach and like to see deep within, around and beneath the issue rather than just examining the preceding context and the future possibilities. They are particularly keen to flush out hidden assumptions in thinking and explore the interplay between breadth and depth.

Many leaders have had no reason to focus on their own vertical development as most have achieved a certain degree of success without doing so. However, more and more realize they can’t continue to succeed in a VUCA world just by doing what they have always done. An increasing number of leaders are therefore starting to ‘wake up’ to the possibility that they need to consider their own development as central not only to their personal success but to their business success too.

Whilst the various developmental academics may look at their subject from different perspectives with different nuances, what they all agree on is that most leaders in business operate from ‘Achiever’ or below. There are clearly leaders who have a more expansive perspective and greater maturity, but the current ‘centre of gravity’ or collective ‘central tendency’ (Cook-Greuter, 2004), is that some 85 per cent of current leadership, is hovering between Level 5 and Level 6 (Table 5.1) (Rooke and Torbert, 2005). And the effects of that are being painfully felt in the world today. For example, one of the main reasons that the world is still in financial turmoil is because of the predominance of non-enlightened thinking at Level 6 or below. This may also be one of the main reasons why leaders are struggling to grow their business in any other way but by mergers and acquisitions (Martin, 2011). And it’s probably at least partially to blame for the worrying number of exhausted executives who are keeling over at their desks, or who are on to their second or third marriage.

We need to evolve. We need vertical development. And we need new ways to lead business that will work now and into the future. We need Enlightened Leadership.

Building the future through Enlightened Leadership

In a VUCA world, the challenge of the future can make even the biggest multi-national obsolete in a matter of years. In his case study at www.coherence-book.com, Thras Moraitis, probably one of the most perceptive and sophisticated executives I have ever worked with, talks about Enlightened Leadership and the need for momentum. Reflecting on his time as Head of Strategy for Xstrata – one of the world’s largest mining and metals companies, operating in more than 20 countries and employing more than 70,000 people globally – Thras suggests that momentum is one of the critical components in building a successful organization. He adds:

Conviction is crucial, because it creates momentum. Organizations of all types need momentum. Someone said to me once about my career: ‘Tread water long enough and eventually you sink.’ The same applies to organizations. You may feel you are doing well and making money, but if you’re not creating momentum in the direction of your conviction then eventually the organization ossifies. You need to keep the momentum, not just for the organization itself, but also for the people working there, so that they feel they’re going somewhere.

In order to future-proof organizations it is vital that companies accurately differentiate five key pieces of corporate thinking within the top right-hand quadrant of the Enlightened Leadership model (Figure 5.4):

- Vision.

- Ambition.

- Purpose.

- Strategy.

- Governance.

Many organizations confuse vision with strategy, ambition with purpose, and very few possess the high-quality governance processes required to handle the complexity they are facing. Without mergers and acquisitions businesses struggle to grow. In addition to being unsure how to grow, many organizations are either unclear what their true purpose is – why they do what they do – or it is poorly articulated. There may be some detailed thinking around strategy but it is often imprecise and it is rarely connected to a full spectrum growth agenda. As I said earlier, few organizations have a clear sense of the future battlegrounds where they will engage their customers more effectively than their competitors and can execute their strategy, and most have not yet developed high-quality governance. Building clear, high-quality answers in all these areas at every level of the organization can set the stage for sustained success well into the future.

We believe that many of the problems that occur in business occur because of poor differentiation of the very concepts that organizations are wrestling with. This can be especially critical following an acquisition, as CFO Shaun Usmar found out at Xstrata Nickel. In his case study at www.coherence-book.com, he explains:

In one recent acquisition the first thing we had to do was to make sure we were all working off the same basic information. People had varied information sources and would use similar terminology, but would mean different things. This resulted in some people double or triple counting things and that leads to poor decisions. We had to spend time as a senior team getting rid of the noise that can be created by people questioning data. That process took a couple of years in the mid-2000s, but it ended up being a crucial step to our future success.

I see this all the time in the work we do with multinationals. For example, we met with an executive board that had been struggling with employee engagement for two years. Within the board it was apparent that there were very different views about what engagement even was, let alone why it was important, how to measure it effectively and, of course, how to increase it. Remember, evolution is only really possible when we can accurately differentiate between one idea or concept and another, and it is a vital precursor for integration and ultimately growth.

When differentiation is poor the business will struggle to evolve. In order to effectively create a prosperous future, elevate performance and deliver results year in year out, a business needs to have universally understood clarity around its key business terms. It may sound like semantics but clarity around these terms is critical because it influences decision making (or lack thereof), productivity and results. When everyone has the same understanding of the terms so often used in business, then it becomes much easier to increase organizational efficiency and effectiveness.

Vision and ambition

When an executive team is asked where their business is going, the most immediate response is: ‘Oh we’ve done all that, vision, strategy and purpose stuff.’ In fairness, the best companies have clarified some of their directional strategic bets, but many have not. Few have linked their strategic bets to a clearly articulated vision of what the world might look like if the strategy was fully delivered. And even fewer understand the difference between ambition and purpose.

For example, in the mining sector Rio Tinto’s vision is: ‘to be the leading global mining and metals company’ (Rio Tinto, 2013). Unfortunately their competitor Anglo American says virtually the same: ‘Our aim is to be the leading global mining company’ (Anglo American, 2013a). A third mining company BHP Billiton states that: ‘We are a leading global resources company’ (BHP Billiton, 2013). None of these are visions. They are all extremely unimaginative ambition statements and they are virtually identical to each other.

When we look at the same three companies’ statements about their corporate purpose they are again equally indistinguishable. Anglo says: ‘We are committed to delivering operational excellence in a safe and responsible way, adding value for investors, employees, governments and the communities in which we operate’ (Anglo American, 2013b). Rio says: ‘Our core objective is to maximize total shareholder return by sustainably finding, developing, mining and processing natural resources’ (Rio Tinto, 2012), and BHP says: ‘Our corporate objective is to create long-term value through the discovery, development and conversion of natural resources, and the provision of innovative customer- and market-focused solutions’ (BHP Billiton, 2010). The Anglo statement is a statement of strategic intent with some hint at purpose. It is not a strategy or an ambition or a fully-fledged statement of purpose or vision. The Rio statement is part purpose (why they exist, ie for ‘shareholder return’) and part a description of what they do, which is not a strategy, ambition, vision or purpose. The BHP ‘purpose’ is likewise a statement of what they do, not why they do it (their purpose).

Vision

Just to clarify, vision is a picture of the future desired destination or what the world will look and feel like as a result of our corporate efforts. It’s not necessarily a fully achievable state but describes our aspiration or dream.

Ambition

Ambition on the other hand is a rational (head) statement about the size, scale, reach, market share or capitalization of the business in the future. Ambition describes how big we want to be (it’s a numbers thing), the level of profitability, the number of offices, geographic footprint, EBITDA etc.

Purpose

Many of the businesses I have encountered since 1996 have been somewhat unclear about the concept of organizational purpose. I recently had a FTSE board member tell me that he did not see the purpose of having a purpose! In contrast, a multinational business reached out to us for help with their purpose saying: ‘We know what we do, how we do it and where we are going in the future; what we are unsure of is why we do it.’ They were also aware enough to know that the answer to the ‘why’ question was not ‘shareholder return’.

A good organizational purpose is an emotional (heart) statement that is able to drive engagement and unlock discretionary effort. It can help define why an employee works for us rather than our competitors. It is the boiled-down essence of employer brand and our employer (not employee) value proposition. In defining our organizational purpose, it can help to differentiate it slightly for the key stakeholders of the business such as customers, employees and shareholder/city analysts.

Purpose is the beating heart of our business; it drives the business forward and draws customers to us. When Apple started, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak believed that technology was not just for business and that it should be beautiful and perfect – inside and out. Their ‘why’ was around creating elegant, intuitive and beautiful products that made life easier and more fun. Their guiding ‘why’ is the reason people queue down the street to get their latest Apple product and are happy to pay significantly more than competitor products to get it. Customers buy into the ‘why’ and people buy Apple because Apple exists to make beautiful things (Sinek, 2011).

Strategy

Virtually every company has done significant thinking around its strategy; however an awful lot of what is included in a company’s ‘strategy document’ is not actually strategy. Our strategy is how we’re going to get to the destination described by the vision and ambition. It describes how we’re going to achieve our purpose.

One of the common failures in strategic thinking is a lack of differentiation in organizational strategy. For example, many organizations suggest that a key aspect of their strategy is that they are going to become customer-centric. Such statements may be correct but they do not distinguish that company from its competitors. What is required is to identify the unique thing about our approach to customers that sets us apart from others. What is it about the way we treat and deal with customers that gives us a competitive advantage and sets us on a different path, providing us with a distinct direction?

Normally it is the combination of a number of strategic ‘building blocks’ that when coherently integrated provides that advantage. One strategic building block may give us a small edge. When that is combined with the second, third, fourth and fifth building blocks we can create ‘clear blue water’ between our company and our competitors. We create market leadership. Despite some truly brilliant analytic work done by the various big ‘strategy houses’, it is interesting to witness the struggle most organizations have in defining a differentiated strategy. Much of this is down to insufficient training in how to think strategically. Many executives are very skilled in operational thinking, but creating difference, setting the business apart – that is a completely separate ability. There are a number of ways to develop much better strategic thinking. Focusing on the differentiated strategic building blocks that will give us an advantage, as outlined above, is one way.

Another way to develop strategic thinking is to understand how to create a completely new game, or what has been called a ‘blue ocean strategy’ (Kim and Mauborgne, 2005) where a business innovates into areas where there are no competitors. A blue ocean strategy is about innovating customer value and creating a new demand where there is no one currently operating. Companies like Sony, Apple and many of the social media giants have successfully adopted blue ocean strategies. This approach is very different to the more familiar red ocean strategy, where businesses are effectively fighting it out in a competitive ‘blood bath’, slashing prices and aggressively managing margins.

Finally, a third option would be to unpack ways of creating the future, and here there are a number of specific innovation techniques that can be brought to bear on developing a winning strategy (Christensen, 1997).

Governance

Corporate governance is a much talked about topic, particularly in light of corporate finance scandals and the recent banking crisis. Just before the millennium a corporate landscape of readily available cash and low interest rates fuelled a rapid escalation of tech firm stock prices. The prevailing mindset was that of a ‘quick buck’. This contributed not only to the dot com crash of 2000 but also to a rash of corporate financing scandals such as WorldCom, Enron and Tyco. As a response to all this failure of governance the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) was introduced in 2002 in an attempt to significantly beef up corporate governance and stop financial misreporting driven by greed-fuelled executive excess. Sadly SOX failed to stop the next wave of governance malpractice and just eight years later we witnessed an even more spectacular greed-fuelled failure in the corporate world, driven by banking excesses. Some authors have suggested that we have still not learnt the lessons of 2008 and a catastrophic governance failure could happen a third time in the very near future (Martin, 2011).

In our experience most multinationals see corporate governance as a set of regulatory compliance committees and practices. Most claim that they have very sophisticated governance mechanisms in place. In fairness, they often do have robust compliance processes. But compliance or operational oversight must be differentiated from effective corporate governance. True corporate governance requires a series of detailed and robust mechanisms and processes that then drive much greater organizational efficiency, improve the quality of decision making on the complex issues, and identify and enforce precise accountabilities and greater strategic and operational alignment. How that can be achieved will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

Enlightened Leadership requires discipline in all the above areas – vision, ambition, purpose, strategy and governance. But each needs addressing separately. Once we gain clarity around these key business principles, we can turn our attention to the types of behaviour that consistently elevate performance across the business.

Performance-driving behaviours

Over the last three decades, the popularity of leadership competency models or behavioural frameworks has grown to the point where virtually every organization has its own framework. Given the impact that leaders have on the organization, and specifically what these leaders actually do and the behaviour they exhibit, this makes good sense. However, despite investing huge amounts of time and money on the quest to find and develop better leaders, many organizations have been severely disappointed at the lack of results this approach has delivered. Many experts believe that the assumptions behind competency models are problematic (Hollenbeck, McCall and Silzer, 2006). Indeed, recent research suggests that many experts in the field believe leadership competencies are deeply flawed, which certainly raises questions as to their practical and commercial relevance (Cockerill, Schroder and Hunt, 1993).

So where does this leave organizations that are understandably keen to proactively develop the behaviours of the leaders they so desperately need? Thankfully, there has been a significant amount of academic research into identifying the behaviours that drive organizational results, and well-developed methods for applying this are available (Schroder, 1989; Cockerill, 1989a, 1989b).

The behaviours that really matter

Effective leadership clearly requires a focus on leadership behaviour, but the primary challenge is to know what behaviour to focus on. There are thousands of potential behaviours a leader could demonstrate that could improve commercial performance, but which behaviours really matter? Which behaviours drive performance improvement? Which behaviours are genuinely commercially relevant?

Harry Schroder from the University of Florida and Tony Cockerill from the London School of Economics have identified an approach that avoids all the problems with competency frameworks (Cockerill, 1989a; Cockerill, Schroder and Hunt, 1993). This was because they started with the right question: namely, what behaviours will leaders need to use to deliver high performance in a complex and dynamic environment? They then studied businesses that were experiencing a huge number of unpredictable changes (large and small), ie dynamic environments, as well as organizations that were experiencing many different types of changes, ie complex environments, so as to pinpoint the behaviours that really matter and their practical applications.

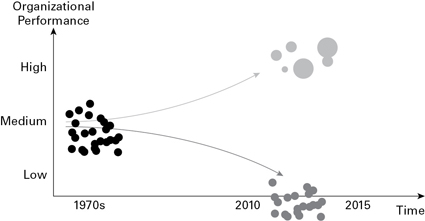

In contrast to the business world of the 1970s, where things did not change that much and were relatively predictable, in the modern VUCA world organizations can be split between those that have found a way to thrive and those that have not (Figure 5.6).

FIGURE 5.6 The impact of a VUCA world on corporate performance

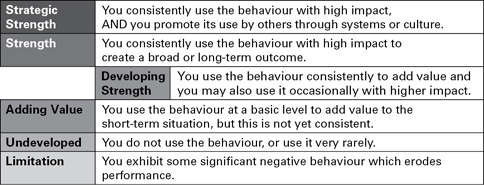

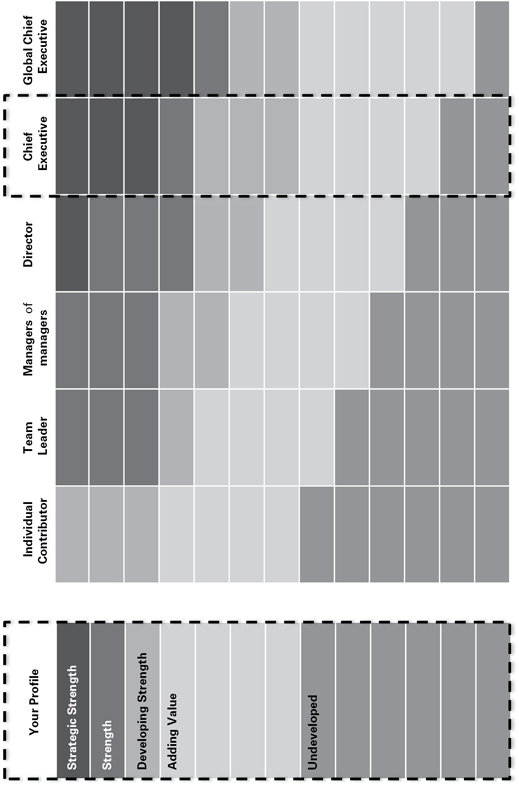

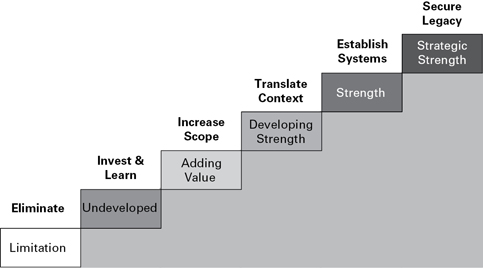

Schroder and Cockerill’s research (Schroder, 1989; Cockerill, 1989b) found that when they studied people from initial idea through to successful implementation there were 12 key leadership behaviours that determine organizational success. All leaders must convert ideas into profitable action. The only difference between success and failure is how proficient each leader is within each of the 12 behaviours. In other words there are five levels of competency within each behaviour, ranging from a ‘Limitation’ to a ‘Strategic Strength’. The more successful, senior and influential a leader is the more behaviours he or she exhibits as a ‘Strength’ or ‘Strategic Strength’.

At Complete Coherence we therefore profile leaders using the Leadership Behaviour Profile (LBP-360), which provides leaders with an accurate insight into individual and team behavioural strengths. This provides us with a map for further development so that individuals and teams can become much more efficient and productive.

This profile will assess an individual across the 12 performance-driving behaviours and illuminate what level of competency that individual currently demonstrates for each behaviour (Figure 5.7). If a behaviour is identified as a ‘Limitation’, then the leader inhibits the behaviour in a way that is eroding business performance. If a behaviour is identified as ‘Undeveloped’, the leader either doesn’t currently use the behaviour or uses it very rarely. Most leaders will have one or two ‘Undeveloped’ behaviours. If a behaviour is identified as ‘Adding Value’, then the leader is already using that behaviour at a basic level to add value to the business, but not consistently. Most leaders have three or four behaviours that are ‘Adding Value’.

FIGURE 5.7 Level of competency within each behaviour

© Complete Coherence Ltd

If a behaviour is identified as a ‘Strength’, then the leader is consistently using that behaviour in the business to great effect. The leader is making a considerable impact on the long-term outcome of the business through that behaviour. A sub-category of ‘Strength’ is ‘Developing Strength’, which indicates that the leader is using the behaviour consistently to add value but is not yet using it consistently to create a significant impact in the business. Most leaders have four or five ‘Strengths’ or ‘Developing Strengths’.

Finally a behaviour is identified as a ‘Strategic Strength’ if the leader is consistently using the behaviour with high impact and is baking that behavioural strength into the business through the coaching of other people, implementation of systems or cultural change. It is possible, by comparing a leader’s behaviours to a global benchmark, to separate directors from CEOs and global CEOs by the number of ‘Strategic Strengths’ that a leader exhibits in their business.

By identifying the current proficiency within these key behaviours, a leader and his or her executive team are able to home in, individually and collectively, on specific areas for development. Instead of wasting valuable time and money on blanket ‘leadership training’ or ‘professional development’ programmes, these insights effectively provide a very tight brief for leadership coaching with the sole aim of elevating behaviours that are currently ‘Adding Value’ to ‘Strengths’, and where appropriate ‘Strengths’ to ‘Strategic Strengths’. Massive improvements in individual and team performance are therefore possible with relatively minimal effort.

The 12 performance-driving behaviours

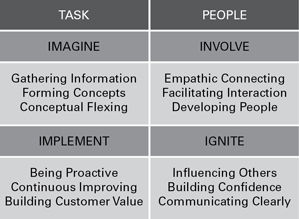

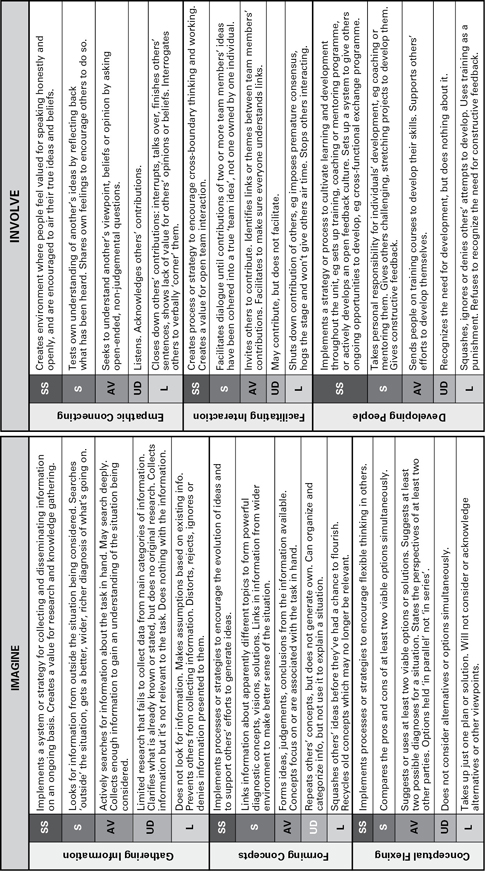

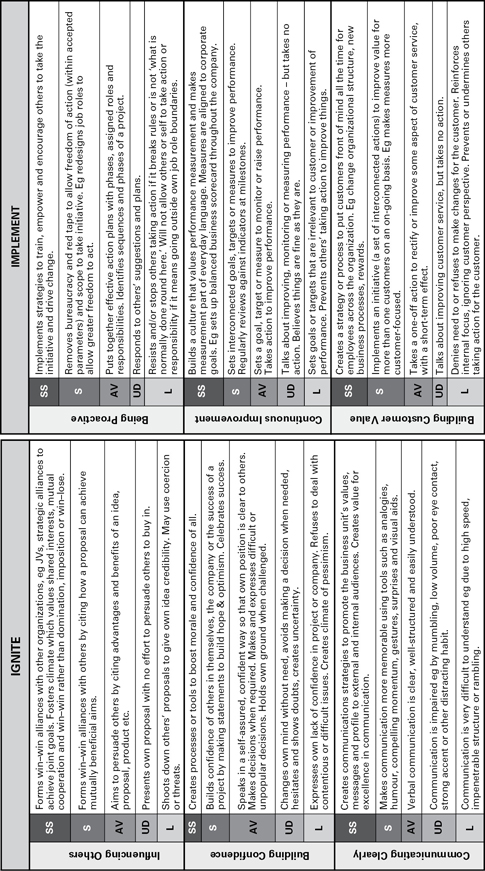

The 12 behaviours that Schroder and Cockerill’s research identified can be organized into four distinct sequential clusters with three behaviours in each, as illustrated by Figures 5.8 and 5.9.

FIGURE 5.8 The four performance-enhancing behavioural clusters

FIGURE 5.9 Varience of output within Imagine and Involve

First behavioural cluster: Imagine

The Imagine cluster describes all the behaviours that leaders need to do in order to gather together all the facts and information they will need to progress an idea or complete a task successfully. There are three behaviours that are critical in the imagine step:

- Gathering information: how well does the individual seek out the information they need to move the task forward?

- Forming concepts: how well is the individual able to marshal the ideas and information gathered into a workable commercial concept?

- Conceptual flexing: how well is the individual able to develop multiple ideas and not become overly stuck on one?

Second behavioural cluster: Involve

Once someone has completed the Imagine step and developed some workable concepts, the individual must involve others and engage them in the process or task. There are three behaviours that are critical in the Involve step:

- Empathic connecting: how well does the individual really listen to other people’s perspectives and get their ‘buy in’ to the concept in question?

- Facilitating interaction: how well does the individual support and facilitate genuine interaction and build a coherent team idea?

- Developing people: how able is the individual to support the development of other people so as to ensure success?

Third behavioural cluster: Ignite

Once the concept has been developed and others are engaged and able to deliver it, other people need to be inspired to get into action. There are three behaviours that are critical in the Ignite step:

- Influencing others: how well does the individual influence and engage the other people necessary for success?

- Building confidence: how well does the individual inspire and build confidence in the idea or task, and in themselves and others?

- Communicating clearly: how clearly does the individual communicate with other people involved in the idea or task?

Fourth behavioural cluster: Implement

Once everyone is on board with the idea or task the final stage is implementation. There are three behaviours that are critical in the Implementation stage:

- Being proactive: how proactive is the individual in making things happen?

- Continuously improving: how focused is the individual on continuously improving or fine-tuning the idea or task to ensure elevated business performance?

- Building customer value: how focused is the individual on building customer value around the idea or task?

More detail regarding the variance of output within the 12 behaviours can be seen in Figures 5.9 and 5.10

FIGURE 5.10 Variance of output withing Ignite and Implement

It is worth pointing out that in the original research Schroder and Cockerill only identified 11 behaviours. The model, often known as the High Performance Managerial Competencies framework (HPMC), is the most widely used basis for leadership behavioural assessment globally. However, there was so much push-back from corporations about the lack of customer focus that they added a 12th behaviour focused on customer value, even though their opinion was that customer value is a mindset not behaviour.

This research enables us to focus only on these 12 behaviours, because these are the ones that really make a commercial difference and have the capacity to transform results. Plus this research has been independently validated in several separate studies (Figure 5.11), including Ohio State Leadership Studies (Stogdill and Coons, 1957), Harvard, Michigan (Katz, MacCoby and Morse, 1950), Princeton Strategy Research, the Transformational Leadership Study (Bass, 1999), Florida Council on Education Management (FCEM) Competency Research (Croghan and Lake, 1984) as well as Professor Richard Boyatzis’ Study for the American Management Association (1982).

FIGURE 5.11 Identification of leadership behaviour framework

When fully present at the ‘Strength’ or ‘Strategic Strength’ level, these behaviours will provide a competitive advantage in that they enable leaders, teams and organizations to perform at outstanding levels in a VUCA world.

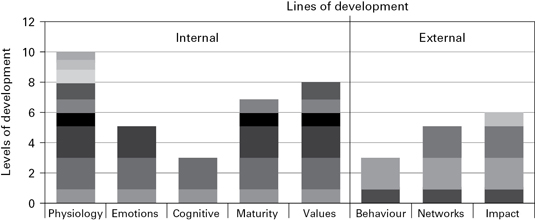

This framework allows us to assess individuals and teams and to identify strengths and weakness within both. Using the global benchmark in Figure 5.12, which is based on data from 55,000 executives, we can identify areas for improvement across a team so that individually and collectively the capacity of the team can develop.

FIGURE 5.12 The leadership behaviour global benchmark