Part Six

Presentation of the

Plan of Capital

Roger Establet

Why reflect on the plan of Capital? Is it not a work that immediately imposes its articulations? It seems enough, therefore, to read its table of contents. But Capital is a difficult work to read, being new both in its concepts and in their organization. It is predictable, then, that the difficulties the reader initially meets with should arise from this novelty of Capital:

– Either he refers the structure of Capital to structures he is already familiar with, and whose relations with Marx’s thought he knows in the mode of prejudice. He will thus read on the covers of the respective volumes: ‘Book One: The Process of Production of Capital’, ‘Book Three: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole’. He can thus assume a Hegelian order. This is the main source of misdirection, as we shall show.

– Or, ‘impatient to come to a conclusion, eager to know the connection between general principles and the immediate questions that have aroused their passions’ (Marx to Maurice La Châtre, 18 March 1872; Capital, Vol. 1, p. 104), he looks for what Marx has to say on the current themes of ‘modern’ disciplines (sociology, political economy), whose proximity with Capital he knows in advance, i.e., in the mode of prejudice. Imposing the order of his preoccupations on the order of his reading, he will go ‘from model to model’, and here again, despite appearances, it is the novelty of Marx’s work that he will lose sight of, since the sciences that determine the order of his preoccupations are new only in not having been born sooner.

It is two passages from Marx himself, therefore, that we shall invoke to prepare a reading of Capital ordered according to its real linkages and breaks. The first of these is to be found in Capital Volume Three, p. 117. And inasmuch as this text has given rise to readings that are difficult to connect with the work itself, we shall compare it with another passage, drawn from the 1857 Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Grundrisse, pp. 99–100).

1. The text of Capital, Volume Three and its difficulties

Here is the text in question:

In Volume One we investigated the phenomena exhibited by the process of capitalist production, taken by itself, i.e. the immediate production process, in which connection all secondary influences external to this process were left out of account. But this immediate production process does not exhaust the life cycle of capital. In the world as it actually is, it is supplemented by the process of circulation, and this formed our object of investigation in the second volume. Here we showed, particularly in Part Three, where we considered the circulation process as it mediates the process of social reproduction, that the capitalist production process, taken as a whole, is a unity of the production and circulation processes. It cannot be the purpose of the present, third volume simply to make general reflections on this unity. Our concern is rather to discover and present the concrete forms which grow out of the process of capital’s movement considered as a whole. In their actual movement, capitals confront one another in certain concrete forms, and, in relation to these, both the shape capital assumes in the immediate production process and its shape in the process of circulation appear merely as particular movements. The configurations of capital, as developed in this volume, thus approach step by step the form in which they appear on the surface of society, [we might say,]1 in the action of different capitals on one another, i.e., in competition, and in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production themselves.

Despite its apparent clarity, due essentially to the fact that it follows the three-part division of Capital itself, this text is far from suppressing all difficulty. The expression ‘on the surface of society, we might say’ (and so we might say otherwise, which means that we should, if there were not great difficulty in moving from a convenient metaphor to the rigorous concept), indicates very well the objective obstacles that Marx himself encountered in presenting scientifically his own scientific procedure. In fact, this text allows at least two readings that cannot seriously account for the order that Marx actually followed.

a) First inadequate reading

In proceeding from Volume One to Volume Three, we move from the abstract to the real. This interpretation was put forward first of all by Sombart and Schmidt (according to Engels’s critical summary of their theory in his supplement to Volume Three of Capital, pp. 1031–3), the law of value that forms the object of Volume One being for them a ‘logical fact’ or a ‘necessary fiction’.2 In this case, Volume Three would appear as the study of concrete economic processes, meaning real ones, by means of this ‘logical fact’ or ‘necessary fiction’. This interpretation of the plan of Capital can only base itself on the text cited above, on condition that the following terms are emphasized:

In Volume One we investigated the phenomena exhibited by the process of capitalist production, taken by itself, i.e., the immediate production process, in which connection all secondary influences external to this process were left out of account. But this immediate production process does not exhaust the life cycle of capital. In the world as it actually is, it is supplemented by the process of circulation, and this formed our object of investigation in the second volume. Here we showed, particularly in Part Three, where we considered the circulation process as it mediates the process of social reproduction, that the capitalist production process, taken as a whole, is a unity of the production and circulation processes. It cannot be the purpose of the present, third volume simply to make general reflections on this unity. Our concern is rather to discover and present the concrete forms which grow out of the process of capital’s movement considered as a whole. In their actual movement, capitals confront one another in certain concrete forms, and, in relation to these, both the shape capital assumes in the immediate production process and its shape in the process of circulation appear merely as particular movements. The configurations of capital, as developed in this volume, thus approach step by step the form in which they appear on the surface of society, [we might say,] in the action of different capitals on one another, i.e., in competition, and in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production themselves.

The first and second volumes, therefore (though the second rather less than the first) would be no more than a set of abstractions necessary for investigating the real: what American sociologists call ‘operational concepts’, econometricians call ‘models’, and Max Weber calls ‘ideal types’.3 These abstractions, which we may understand as provisional schematizations of the real, only acquire their validity inasmuch as they make it possible to illuminate the concept, i.e., the real that they schematize. It goes without saying that an ideal type, model or operational concept is never directly manifested as such in the real, and that the movement of validation consists precisely in noting the differentials of the real in relation to the schema (which makes possible the construction of a second schema, or a fine-tuning of the first one).

Applied to Capital, this interpretation is confirmed by a certain number of facts:

The law of value does not apply directly: there is a discrepancy between value (schema, abstract) and price (concrete, reality), and a discrepancy likewise between rate of surplus-value (abstract, schema) and rate of profit (concrete, reality). Now, the place of schemas in Capital is certainly Volume One, and that of discrepancies Volume Three. Thus, Volume One is indeed the place of the abstract, and Volume Three the book of the real, with Capital as a whole being a movement of ‘progressive approximation’ from the abstract towards the real.

A conception of this kind presupposes an unacceptable empiricist theory of science, which in the present case would amount to introducing into Capital an unintelligible caesura: tying a theoretical production to a reality in this way, in fact, is complete fantasy. To provide the theory of these discrepancies, it is not enough to note discrepancies between the reality whose theory is being produced and the initial theoretical results.4 Theory follows a completely ‘logical’ order, which is the order of construction of the laws of its object. The concepts of rate of surplus-value and rate of profit are fundamentally of the same type: they are theoretical productions. And they can only be distinguished within this production on the basis of theoretical relations: it is necessary first of all to elaborate the category of surplus-value in order to elaborate the category of profit, but the latter has a richer content, as it presupposes a relation with other concepts as well as that of surplus-value.

We can draw from this critique a lesson that is important despite being negative: the empiricist distinction abstract/real cannot teach us anything about the order of Capital. And, if it is very crudely correct to say that more phenomena readily detectable in capitalist reality can be recognized in Volume Three than in Volume One, this is a matter of the results of the method, not of its structure. Besides, this statement is only very crudely correct: taken as acquired knowledge, it would lead to neglecting the theory of working-class struggles over the working day, a phenomenon readily detectable in historical reality, which can be found right at the start of Volume One. And finally, it leads to the arbitrary editing of Le Capital by Maximilien Rubel (in the Pléiade collection), which relegates these texts to the end of this volume, thus reducing them to the minor theoretical role of concrete illustration (by reality) of abstract schemas.

b) Second inadequate reading

In proceeding from Volume One to Volume Two, we move from the micro-economic to the macro-economic, i.e., from abstract models of the really simple to abstract models of the really complex (this being the theory championed by Maurice Godelier in a very important article: ‘Les Structures de la méthode du Capital de Karl Marx’, Économie et Politique, June 1960).5

In this interpretation of the plan of Capital, the previous opposition abstract/real ceases to be explanatory, since it is present in each of the volumes according to the following schema:

| Volume One Volume Two, Parts One and Two | Volume Two, Part Two Volume Three | |

| Reality | The firm | The set of firms |

| Theory | Model of the firm | Model of the whole |

Inasmuch as this reading uses the notion of model with greater rigour than the previous one, it is still less adequate to its object. (Any reading of Capital risks being all the less adequate, according to its greater use of the empirical and totally inadequate concept of model). Its strange result, in fact, is that the theory no longer has an autonomous procedure of its own, but is presented as a succession of schemas whose order is imposed by reality itself. Very fortunately, reality lends itself to theory, since it is possible to discern in it a simple real (the firm) with which one can begin, and a complex real (the real set of firms) with which one must end up.

Strictly speaking, to reject this conception of the plan of Capital, it is enough: a) to compare it with the passage in the 1857 Introduction in which Marx, in order to define his method, makes a complete distinction between the real process and the process of thought (Grundrisse, pp. 101–2); b) to bring to light its fundamental presupposition, i.e. the de facto existence, which cannot be accounted for, of a pre-established harmony between the reality and the theory. However, it is true that the text of Capital Volume Three can justify this reading, on condition that the following elements are emphasized:

In Volume One we investigated the phenomena exhibited by the process of capitalist production, taken by itself, i.e., the immediate production process, in which connection all secondary influences external to this process were left out of account. But this immediate production process does not exhaust the life cycle of capital. In the world as it actually is, it is supplemented by the process of circulation, and this formed our object of investigation in the second volume. Here we showed, particularly in Part Three, where we considered the circulation process as it mediates the process of social reproduction, that the capitalist production process, taken as a whole, is a unity of the production and circulation processes. It cannot be the purpose of the present, third volume simply to make general reflections on this unity. Our concern is rather to discover and present the concrete forms which grow out of the process of capital’s movement considered as a whole. In their actual movement, capitals confront one another in certain concrete forms, and, in relation to these, both the shape capital assumes in the immediate production process and its shape in the process of circulation appear merely as particular movements. The configurations of capital, as developed in this volume, thus approach step by step the form in which they appear on the surface of society, [we might say,] in the action of different capitals on one another, i.e., in competition, and in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production themselves.

Godelier’s reading is thus a possible one. We should add that, if we keep to the elements of the real process as successively used in Capital, this receives an approximate confirmation from the process of thought. In fact, Volume One only takes its examples from the isolated firm (except for, and this is very important, the theory of wages and the theory of the industrial reserve army), whereas Volume Three brings in all capitalists, the stock exchange, banks, etc. Let us provisionally maintain the concept of example: it is clear that a theory selects its examples as a function of its own theoretical needs, which cannot be determined by the elements of the real process, playing the role of examples. And let us assume that we are dealing, by way of the example of Volume One, with the isolated firm. What Godelier does not explain is:

1) The theoretical reasons why this should be so, unless we suppose that the isolated firm is both – but by what chance? – both the really simple and the theoretically simple. Which leads us to:

2) That Marx only uses those aspects of the isolated firm that he requires for the thought process at the level of Volume One. For, if the real movement of a concrete firm over a definite period had to be conceived, not only would it be necessary to draw on Capital as a whole, but also to elaborate new concepts on the basis of those that Capital provides.

And if this explanation cannot be offered, there are two reasons for this, which we shall briefly explain. First of all, the object of Volume One is not the firm: and then, if one wants at any cost to preserve the notion of model in speaking of the relationship of thought to reality in Capital, this would be in a sense close to that defined by mathematicians, not that used by econometricians: in other words, its sense has to be reversed.

What Volume One deals with is in no way the firm, but a theoretically defined object, i.e., ‘a fraction of the social capital that has acquired independence and been endowed with individual life’ (Capital, Vol. 2, p. 427). If, therefore, this fraction of the social capital has to acquire independence, this means that it is not equivalent to the real firm, which everyone knows is sufficiently independent not to need to wait for Marx to acquire this property. It is rather a question of theoretical endowment, or the result of a theoretical division of a theoretical object thus endowed with a theoretical independence. We shall seek to give a theoretical explanation of this operation.

There remains the ‘model’. To speak of a model in relation to the firm is not to explain the structure of Capital, it is rather to give a pedagogy (one possible pedagogy) of Volume One. Here is why. Let us assume that the theory had been able to explain the fact that the object that it gives itself is indeed ‘a fraction of the social capital that has acquired independence’, i.e. that the definition and laws of this had been established. It would then be possible for a pedagogue to turn to the real process and speak more or less as follows: ‘You know X … Please ignore his personal tastes and political leanings. You know that he has made a good deal of money. Please ignore his talent as a speculator, and assume for the hypothesis the absence of crises, price rises, in other words assume that all the other conditions (except for the one that I shall utter in a theoretical form) are equal. We consider X at the moment when, possessing a certain sum of money, he converts this into means of production. I could just as well have taken the example of Y or Z. Now, in these conditions, which the theory has just defined for you, and in these conditions alone, you can give yourselves an idea of what in reality corresponds to the object whose concept we are in the process of producing. Let us therefore leave X to his business affairs and return to our object, as it is this we are concerned with and not X.’

What therefore is a model? Either it is a schema of the real, and then it has no validity except in a pseudo-science, with no other concern than to make itself an approximate representation of the real, so as to be able to subject this to certain practical manipulations. For, anyone who says schema says dissection, anyone who says dissection says principle of dissection, and whoever says principle of dissection is either giving a theory of this, and essentially doing without schemas, or else is not doing theory and resting content with schemas, his real satisfactions being elsewhere. Such is the function of any practice of the ‘model’ in ordinary econometrics. Either a model is the image of the theoretical object that can be sketched in reality by subjecting it to the preconditions of the theory: such is more or less6 the concept of the mathematicians. And if one wants at all costs to use this in speaking of Capital, one would have to say: the individual firm is one possible model of the object whose theory is given in Volume 1. But on no account can one say: the object of Volume 1 is the model of the firm. We have therefore established, I believe:

1) What exactly are the examples at each of the stages of Capital. (They are models. They have a pedagogic purpose.)

2) That it is only possible to understand the order of the stages on the basis of characteristics of examples. (Capital is not a succession of models.)

Conclusion

The legacy of this problematic text consists in the misdirections about the structure of Capital that it can allow. We shall examine below the exact extent to which this text is responsible for these misdirections on the part of its readers. What we do know right away, despite this, is:

– that the order of Capital is in every respect a theoretical order: there is not a progress from the abstract to the real, nor from the simple real to the complex real;

– that the schema/reality relation does not explain either the order of Capital or of each of its stages;

– that if the order is in every respect theoretical, it can only be a function of the formal concept of its object;

– that since the object of Capital is a definite mode of production, the order of Capital must essentially be a function of the formal concept of mode of production.

Which is why, provisionally abandoning the difficult text that we have been commenting on against its grain, we shall now turn to a section of the 1857 Introduction (Grundrisse, pp. 99–100), whose purpose is precisely to define the formal concept of mode of production.

2. Let us now consider the text of the 1857 Introduction (Grundrisse, pp. 99–100)

Chapter 1. Marx’s Own Presentation of Capital

As is well known, Marx’s 1857 Introduction is a text in which he anticipates the results of Capital, but which he decided against publishing, perhaps for fear that his anticipations would be taken for results, and held to be fully elaborated and demonstrated. In other words, this text must be read with precaution, but also, inasmuch as it anticipates the object of Capital, it allows us to anticipate the structure of this, which is the very objective of the presentation of a plan.

Here is the text that interests us:

The conclusion we reach is not that production, distribution, exchange and consumption are identical, but that they all form the members of a totality, distinctions within a unity. Production predominates not only over itself, in the antithetical definition of production, but over the other movements as well. The process always returns to production to begin anew. That exchange and consumption cannot be predominant is self-evident. Likewise, distribution as distribution of products; while as distribution of the agents of production it is itself a moment of production. A definite production thus determines a definite consumption, distribution and exchange as well as definite relations between these different moments. Admittedly, however, in its one-sided form, production is itself determined by the other moments. For example if the market, i.e., the sphere of exchange, expands, then production grows in quantity and the divisions between its different branches become deeper … Mutual interaction takes place between the different moments. This is the case with every organic whole.

For our purpose here, this text requires the following remarks:

1) It establishes that every mode of production (a ‘reasoned abstraction’ or formal concept of the object of political economy) is a complex structure of distinct elements in which one is dominant (on the concept of a complex structure in dominance, cf. Louis Althusser, ‘On the Materialist Dialectic’, For Marx). The dominant here is production.

According to the passage cited here, this dominant has two modalities: on the one hand, the mode of production is the actual unity of all the distinct elements, being defined here in a broad sense as the entirety of economic practice; on the other hand, the production process in the restricted sense, i.e., as process of transformation of what is either given by nature or already worked into a finished product responding to a definite social need, is, within this unity, the determining element in the last instance.

2) If this is indeed the formal concept of every mode of production, the study of a definite mode of production must therefore begin with the study of the determinant system (mode of production as production process in the restricted sense, or what Marx calls in Capital Volume Three the immediate process, as commented on above), and can only be completed with the theory of the unity of the determinant and the determined, i.e., the theory of the mode of production in the broad sense, or, to be more precise, in its full sense.

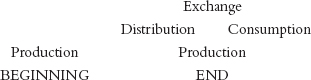

3) The beginning and the end as determined in this way follow the following schema:

The stages are as follows. It is necessary to escape from the theory of determined elements of the structure, into what is specific about them in relation to the process of immediate production, and inasmuch as they exert on this a reciprocal determination.

We have to note that this methodological schema fits Capital (almost) perfectly.

Beginning: theory of the capitalist mode of production in the restricted sense, or theory of the immediate process of capitalist production, Volume

One.

End: theory of the unity of the different elements of the structure, or theory of the capitalist mode of production in the full sense, Volume Three.

The intermediate stages are reduced here to a single one: study of circulation in its specificity, then in its unity with the process of production in the restricted sense. That is the object of Volume Two. This lack of fit is clearly a problem, to which we shall return.

4) But if this is an important problem, it should not hide from us another one. If a correspondence is possible between the order of Capital and the concept of mode of production as defined in the 1857 Introduction, this is simply because that formal concept is an anticipation of the results of the scientific study in Capital of a definite mode of production. The text of the 1857 Introduction, therefore, has only a pedagogic priority over the structure of Capital. If it makes it possible to get an overall view of this structure that is not completely mistaken, it is not sufficient to found this or present it completely.

5) The text of the 1857 Introduction does not provide a foundation for the organization of Capital.

The text that we have commented on begins with the words: ‘The conclusion we reach …’ It is presented, in other words, as the result of a theoretical work. This theoretical work is of a quite particular kind: a long line of argument. Marx started, in fact, from a result of classical political economy, which he subjected to a tight critique (production = nature; distribution = society; exchange, consumption = individuality). Contrary to this contention, Marx establishes that the distinctions between these categories are all located within a single ensemble (the social, which is a rather vague concept). And he shows at the same time that their differentiation is possible only within a single field. Finally, he establishes the dominance of this unity over the two categories previously defined. The reasoning is therefore a critical examination of a thesis whose rectification is conducted by appealing to a wide knowledge of economic problems on the part of the reader. The theoretical effort, of which the text cited is the result, is thus constructed not according to a scientific order, but according to the laws of traditional rhetoric. The ‘self-evident’, in ‘That exchange and consumption cannot be predominant is self-evident. Likewise, distribution as distribution of products’, indeed proves that Marx’s true reasons, and thus the real theoretical effort, lie elsewhere: quite precisely, in Capital. Thus one very important aspect of Capital must consist in the scientific validation of its own organization, which is only justified here in the mode of learned rhetorical discussion.

6) The text of the 1857 Introduction does not allow the organization of Capital to be completely presented.

If the form of exposition is not entirely rigorous, or has only a limited rigour, it necessarily follows that its result – the definition of the formal concept of mode of production – can be only approximate. Hence the recourse to metaphor: ‘This is the case with every organic whole’, which certainly indicates the result to which Capital is supposed to lead, but does not make it possible to know this.

Conclusion

This text, as presented, and with the limits necessarily imposed on a pedagogic introduction, is more suited to dissolving major errors than to the establishment of truths, and gives us the following warnings:

1) The organization of Capital is not that of a procedure going from the particular to the global, or from the abstract to the real, but one that goes from determinant to determined, through to the full system of determination.

2) The organization of Capital cannot be entirely linear: the metaphor of the circle and the examples that validate it are sufficient to show that, in order to produce the theory of the determinant in a system of reciprocal determinations, this minimum in the way of a theory of determined elements is necessary so as to permit either a provisional understanding of these, or to cancel their efficacy.

3) That the two above warnings can only gain a rigorous meaning in Capital itself.

Chapter 2. The Articulations of Capital

We thus have to turn to Capital itself. The point is clearly not to produce a summary, if only to show that such a summary can conform to the order defined by the text of the 1857 Introduction. In other words, we assume that the theoretical content of Capital is already known, and that as far as this content is concern, we are completely dependent on all the explanations elaborated in the present work. We simply propose to mark clearly the major breaks in Capital, to explain the logical linkage that these imply, in brief, to determine the theoretical function of the parts in the structure of Capital. We have chosen not to let ourselves be blinded by the overly clear articulation of Capital into three Books or Volumes, and these in turn into Parts, since our intention is not to rehearse this but to explain it.

Let us define, without justifying them, three major articulations that we shall call for convenience of exposition, and in order of logical importance, ‘Articulation I’, ‘Articulation II’ and ‘Articulation III’.7

We may say right away, in order to justify our order of exposition, that if Articulation I and Articulation III present few problems; if, in other words, it is easy to elucidate the theoretical function of the elements that they partition, the same is not the case with Articulation II. In fact, not only is its theoretical significance rather unclear, but also, the exact position of the place of the break that enables us to establish it is open to debate.

Articulation I is the ensemble of two theoretical elements (Parts One and Two of Volume One, on the one hand; the rest of Capital, on the other), determined by a break that runs between Parts Two and Three of Volume One.

Articulation II is the ensemble of two theoretical elements (Volumes One and Two on the one hand, Volume Three on the other) determined by a break that runs between Volume Two and Volume Three (we shall modify the exact place of this break further on).

Articulation III is the ensemble of two theoretical elements (Volume One on the one hand, Volume Two on the other), determined by a break situated between Volume One and Volume Two.

A) The study of Articulation I

It is necessary, in fact, to isolate Parts One and Two of Capital Volume One completely, inasmuch as they fulfil a determining function for the thought process that occupies the entire work: it is these two Parts that see the theoretical transformation accomplished to which Marx subjects the ordinary discourse about capitalism (or bourgeois society, industrial society, our society, as you will), as well as the discourses of ordinary economists, transforming this ideological discourse into a scientific problem. This presupposes, as Louis Althusser has established (in For Marx):

– the formulation of the problem;

– the definition of the site of the problem;

– the determination of the structure of its ‘positing’, i.e., of the concepts required by its formulation.

We do not mean that the thought process of Capital as a whole is completely formulated here, situated and structured in a virtual mode, rather that the transformation of Generalities I about ‘our society’ by Generalities II, which is conducted in these first two Parts, irreversibly determines the process of production of Generalities III.8

Let us rapidly demonstrate this. In the first two Parts, Marx follows a logical procedure of the same structure, which include the following steps:

– First stage: Marx starts from a nominal definition (capitalist society as an ‘immense collection of commodities’, p. 125), and of surplus-value as M′ = M + ΔM (p. 251), a definition which is self-evident and whose constituent elements are borrowed from the sphere of circulation.

– Second stage: Marx subjects this nominal definition to the test of analysis and formulation, at the same level as that at which they were stated, i.e., in the sphere of circulation. The result of this test is the noting of a contradiction, not in the sense in which we speak of primary and secondary contradictions, as properties of the object whose theory is produced, but in the sense that the formulation, at the level at which it is defined, can only state about its object relations that are unintelligible and impossible to coordinate. In other words, inasmuch as these relations cannot remain unintelligible and impossible to coordinate, the self-evident is transformed into a problem.

– Third stage: We shall define this in a moment.

– Fourth stage: So as to make the contradictory relations he has already formulated intelligible, and coordinate them, Marx establishes the necessity of shifting the site of the problem: the two concepts of average social labour and of labour-power as a commodity that produces value by its consumption have no other theoretical function than to demonstrate the necessity of this shift. In fact, if they indicate the site of the solution, they cannot at this level be the solution, since, in the theoretical form in which they are introduced, they can only be very problematic. This shift can be stated as follows: in order to posit scientifically the problem formulated at the level of the circulation sphere, it has to be posited within the sphere in which the concept of average social labour and the concept of labour-power can be completely elaborated, i.e. the sphere of production. In order to resolve the problem, therefore, the full concept of this sphere has first to be elaborated.

So as to be able to proceed quite rigorously from the second to the fourth stage, it was necessary to produce the theory of the conditions of possibility of the formulation as such, i.e., of money – in such a way that it could not be held responsible for the contradictions whose formulation it makes possible, and thus for the place of their solution; and in such a way, also, that it is itself subject to the contradictions whose statement it permits. The theory of money thus appears as the decisive stage in this theoretical shifting of the problem (the fundamental theoretical operation of the first two Parts), since it demonstrates that not only the objects subject to circulation, but also the formal condition of the circulation sphere and thus the entirety of laws governing this sphere, are subject to conditions of possibility whose theory it is impossible to produce at the level of circulation itself.

It is now possible to explain the theoretical foundation of Articulation I, i.e., to define the exact measure – extent and limits – within which the first two Parts of Capital possess a determining function, relative to the thought process as a whole. This thought process is determined by the first two Parts because these give to its object its first scientific form – or again, give its object in its first scientific form – by the transformation they accomplish of empirical facts into a problem possessing a rigorous formulation and a definite place. Moreover, this process of transformation is conducted in such conditions that it determines an initial structure of the solution procedure. It establishes between two spheres, in fact, the necessity of a connection as well as a relation of determination. By so doing, the thought process receives an initial theoretical objective (thinking the connection) as well as a general indication concerning its procedure (producing first the theory of the determinant, then the theory of the determined). What is founded in this way is the general structure of Articulation III.

It results from this study, however, that the determinant function of Parts One and Two, relative to the thought process as a whole, is strictly limited. In fact, Articulation III, of which these first two Parts define the general structure, is a minor theoretical articulation. The articulation that Marx recognizes as fundamental in all the texts we have commented is Articulation II. Yet this articulation is not defined at all by Parts One and Two: we seek in vain, in these two Parts, for the problematics of the simple and the complex, the individual and the global, the abstract and the real, by way of which Marx and his commentators have sought to found Articulation II. This means that, if these first two Parts determine the thought process of Capital as a whole, this determination is problematic, since it does not directly determine either the whole content of the process, nor even its overall structure. In other words, if the first two Parts do play a key role in relation to the whole of Capital, this is not because they contain in embryo, in a virtual mode, its full problematic. It is only in the course of resolving the problem, which receives its general structure (Articulation III) in the two first Parts, that the problematic of Articulation II could be produced. We can therefore define the exact limits within which the first two Parts are decisive for Capital as a whole. This decisive role is indirectly decisive, or is decisive only in the last instance: if the problematic of Articulation II depends on the problem posed in Parts One and Two, inasmuch as the formulation, its place and its structure are determined by (or have as their theoretical condition of possibility) the solution of the problem that receives its formulation in Parts One and Two, it is in no way the development of this. Nothing can more clearly distinguish the organization of Capital from the Hegelian order, of which the Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit gives the best definition: ‘But the goal is as necessarily fixed for knowledge as the serial progression; it is the point where knowledge no longer needs to go beyond itself, where knowledge finds itself, where Notion corresponds to object and object to Notion’ (para. 80). This definition in turn implies that no knowledge would be possible if the end were not already contained in the initial non-knowledge, and from the first recognition of this non-knowledge: ‘if it was not and did not want to be in itself and for itself near us from the start’ (ibid.). And so, while sense-certainty determines not only the whole of the Phenomenology of Spirit, but above all the configuration of this totality, i.e., the order of figures in this configuration, Parts One and Two of Capital, while they do determine the whole thought process, do not determine its totality or complete structure. This is because determination does not have the same meaning for Hegel and Marx. With Hegel, it is origin that is primary; with Marx, it is beginning. And while origin determines by prefiguring, a decisive beginning can only determine an initial configuration, on which all others depend, inasmuch as these are united to the former by a theoretical connection, partially decided by this, but without dependence ever being able to signify repetition, thus without our having the right to ignore that any new configuration is indeed a new one.

B) The study of Articulation III

The relative theoretical function of the two parts partitioned by the break of Articulation III can be stated as a relation of complementarity. This is how Marx presents it in Part One of Volume Three, which we already commented at the start: ‘In Volume One we investigated the phenomena exhibited by the process of capitalist production, taken by itself, i.e. the immediate production process … [I]t is supplemented by the process of circulation, and this formed our object of investigation in the second volume.’ In order for a relation of complementarity to be possible, it is necessary for the two theoretical elements to have as their objective the solution of one and the same problem concerning the same theoretical object. This is precisely the case. The sole problem, whose solution is not complete until the end of the first two Volumes, is the problem posed in Parts One and Two of Volume One, i.e., the correlative questions of value and surplus-value. The theoretical object whose laws Volumes One and Two construct, so as to completely resolve this problem, is that of ‘a fraction of the total social capital that has acquired independence’ (Volume Two, p. 427), i.e., any object that can be given a nominal formulation as given on p. 255 of Volume One: any object whose movement is inscribed in the sphere of circulation, defined by the law of general equivalence of exchanges, such as M′ = M + ΔM, is a fraction of the social capital ‘that has acquired independence and been endowed with individual life’. In formal terms, the concept of fraction is a consequence of the definition: according to the logical laws of the formulation, whose place is the sphere of circulation, the social capital is nothing other and nothing more than the sum of its fractions (‘the social capital considered as a whole’ has no assignable meaning at this theoretical level). The concept of an acquired ‘individual life’ only signals, again at this theoretical level, the difference between the theoretical object and any concrete model that might be drawn from it, the least observation on a real individual capital being sufficient to prove that the real autonomy of the latter is completely relative.9 The complementarity between the two theoretical elements partitioned by Articulation III thus has a theoretical foundation, since Volumes One and Two produce all the laws of one and the same object as the solution to the problem of Parts One and Two of Volume One. The only problem that this concept of complementarity does not resolve is that of the theoretical status of Part Three of Volume Two: the theoretical object whose laws this Part produces, by introducing new concepts and a new problematic, is a new object. Since the concept of complementarity has proved sufficiently rigorous to define the unity of what it is that partitions Articulation III, we shall provisionally abstract from Part Three of Volume Two, which would compromise this unity and its concept.

If the unity of what divides Articulation III must be thought as a relation of complementarity, this does not mean that the two theoretical elements here are placed on the same level. The order of exposition, as transition from Volume One to Volume Two, assumes a theoretical hierarchy between the two elements. This can be stated as follows: none of the theoretical laws elaborated in Volume Two could be established and demonstrated without the entirety of laws elaborated in Volume One. This is not a real reciprocity, despite certain appearances to which we shall return. The full demonstration of this point can only be given by study of the production of the laws of the object in Volume One. At this point, we can give the following double proof of this: on the one hand, it has been established in the first two Parts that only production could account for the general law of circulation and the particular law of the circulation of capital; on the other hand, if all the new laws of the object produced by Volume Two are considered, laws that can all be reduced to three cycles imposed by circulation on production itself, it can readily be verified that all the concepts that serve to formulate these laws have been defined without exception, including the concept of cycle itself, in Volume One. This amounts to saying that the laws of production determine the laws of circulation. And that is not all. As Marx demonstrates in Chapters 4 and 5 of Volume Two, the complementarity between the laws of production and the laws of circulation is determined by the laws of production.10 It would be possible from this standpoint to conveniently resolve the problem of Part Three of this volume. By establishing that the process of reproduction of the social capital, taken as a whole, determines the unity of the production process and the process of circulation, does Marx not generalize the demonstration established in Chapters 4 and 5 of the first Part of Volume Two? Yet this is not an adequate solution. In Part Three of Volume Two, in fact, it is no longer a matter of three cycles and the unity of these three cycles: Marx thus considers this problem to have been resolved, as it indeed is by the laws of the process of production. The theory of the complementarity of the laws produced by Volume One and Volume Two is already completely formulated. Besides, in Part Three, the object and the problems change. In whatever sense one may take this term, the relation between Part Three and the rest of Volume Two is not one of repetition.

Articulation III, therefore, defines an order of unambiguous determination between two complementary theoretical elements. However, the new laws produced by Volume Two are not simply added to the previous laws: they modify them. The general modality of this modification, of which Part Two of Volume Two, ‘The Turnover of Capital’, draws the most important consequences, may be conceived as the substitution of a structural time with complex periodicity for one of simple periodicity. It would then be contradictory to maintain between two sets of laws both a relationship of unambiguous determination and a series of reciprocal modification, even localized. It is true that the good dialectical (Hegelian) conscience of our human sciences would easily extract itself from this false step, by imputing the logical contradiction to the contradictions of the object, transforming a logical confusion into dialectical method, where the dialectic receives the definition of a confused discourse about confusion, the assertion of the reciprocal determination of everything by everything.11 However, the modifications of determinant laws by determined laws have a completely different rigour for Marx. If the determinant laws can be determined by the laws that they determine, this is because the relations that they establish have defined limits of validity, and define the limits within which they can be determined. The modifications of determinant laws by determined laws, no matter how important they may be in constructing a concrete model, are all effected within these limits. The necessity of constantly preserving money-capital, instead of converting it totally into means of production, imposes a new determination on the law of expanded reproduction, within limits that the law itself has fixed; it in no way transforms the law itself. Thus the text of the 1857 Introduction – ‘A definite production thus determines a definite consumption, distribution and exchange as well as definite relations between these different moments [bestimmte Verhältnisse dieser verschiedenen Momente zueinander]. Admittedly, however, in its one-sided form, production is itself determined by the other moments.’ – receives in Capital its rigorous demonstration and formulation.

The theoretical foundation of Articulation III being thus defined, and the relative function of the theoretical elements that this articulation partitions being fixed, we can now proceed to study the articulations of the determining theoretical elements, i.e., of Volume One.

C) The study of the articulations of Volume One

Volume One elaborates the determining laws of the ‘fraction of social capital that has been endowed with individual life’, by situating it in ‘a sphere’, that of production. Despite the immediate concrete meaning of this concept, and despite the immediate concrete meaning of the opposition between circulation and production, Marx produces the scientific concept of this, adequate not only for the theoretical study of a mode of production that he undertakes here, but that of any mode of production. The fundamental concept necessary for defining scientifically the theoretical field of the study is the concept of ‘labour process’, whose essential elements are defined at the start of the study (Volume One, Part Three, Chapter 8), but many other elements are only introduced when they are necessary for establishing the laws of the specific object of Volume One, which does not prevent them from being logically of the same type: these are the Generalities I of Volume One. As Étienne Balibar has devoted a major essay in the present book to the definition of concepts of this type, I shall assume that their meaning is already familiar. If we leave aside Part Eight of Volume One, on ‘So-Called Primitive Accumulation’, which poses particular problems, we can distinguish in Volume 1 two sub-articulations, which we shall call Sub-articulation A and Sub-articulation B, and which partition the text as follows:

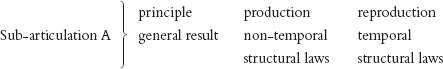

Sub-articulation A, by its break, distinguishes between the ensemble constituted by Parts Three to Six, on the one hand, and that constituted by Part Seven on the other.

Sub-articulation B, by its break, distinguishes Part Three from the ensemble constituted by Parts Four, Five and Six. These elements already bear a title in Capital, so that we can write:

Sub-articulation A: production of surplus-value/accumulation of capital;

Sub-articulation B: production of absolute surplus-value/production of relative surplus-value.

As we see, Marx’s names are chosen as a function of the theoretical results elaborated, since the concepts that serve as names only have a meaning as categories of the capitalist mode of production. Thus they cannot explain the mode of elaboration of these results. Since what we have to deal with here is this elaboration, we shall name the theoretical elements partitioned by the two sub-articulations on the basis of the concept that defines the theoretical field of Volume One as a whole, i.e., the labour process in general. We then obtain the following headings:

Sub-articulation A: study of the capitalist labour process/study of the reproduction of the conditions of this process;

Sub-articulation B: study of the capitalist relations of production/study of the capitalist organization of the productive forces.

These simple descriptions, which we shall explain, are sufficient to show that what Engels writes in the 1885 Preface to Volume Two, i.e. that the novelty of Capital, its scientific character, does not consist in some new assertions about capitalist society, but essentially in the scientific process of their production.

Sub-articulation A partitions the study of the capitalist production process, i.e., the production of the fundamental laws of each ‘fraction of the social capital endowed with individual life’, according to a theoretical necessity that holds for any mode of production; every mode of production must reproduce its own preconditions. This means that the production process must reproduce not only its elements (object, means, worker), but also the double combination of its elements that defines it as a specific relation of production and a specific system of productive forces. As a consequence, Sub-articulation A defines a relation of unambiguous determination between its theoretical elements, such that the complete elaboration of the laws of its reproduction presupposes the complete elaboration of the structures of the production process, without there being true reciprocity; and a relation of complementarity, such that the theory of the capitalist labour process can only be the whole of the laws governing production and reproduction.

The theoretical complement of the laws of reproduction in relation to the laws of production consists in the elaboration of the specific structural time of the capitalist labour process. In fact, in elaborating the laws of production, time, as quantitative time of the working day and as quantitative measurement of labour, is conceived only as an element of the structure. In the laws of reproduction, it appears as one of the laws of the structure itself. The concept of this time is determined by the following characteristics: it is simultaneously a time with simple periodicity, such that the order of repetition and succession of its phases obeys a single principle, and an irreversible time, such that the order of its phases cannot be reversed without becoming unintelligible. Both simple accumulation and accumulation on an expanded scale are subject to the first precondition, but only expanded accumulation, characteristic of the capitalist labour process, is subject to two preconditions. This time is not added by Marx as a new ‘parameter’, to use the language of models, or a new ‘dimension’, to use the language of fashion; its concept is produced on the basis of the laws of the structure: to be precise, on the basis of the relation between surplusvalue and capital, on the one hand, and of the specific organization of the production forces, on the other. Once this concept is produced, it modifies the relations previously established by subjecting them to new preconditions, and particularly making possible the elaboration of a fundamental tendential law: the law of the transformation of the organic composition of capital (law of the decline in variable capital in relation to constant capital).

The theoretical foundations of Sub-articulation A are thus fully explained. We need however to dispel an ambiguity that risks arising on account of the closeness between our formulation:

and a formulation of the ‘synchrony/diachrony’ kind, whose general lack of pertinence in the exposition of Marx’s concepts has been shown by Althusser.12 It is easy to verify this lack of pertinence in the particular case: on the one hand, whereas the synchrony/diachrony pair implies, in its ordinary use, a distinction between structure and temporality, synchrony being sufficient to define the structure, and diachrony only responsible for what becomes of the structure when immersed in time, it is clear from what we have just shown that the non-temporal structural laws and the temporal structural laws are equally and on the same basis laws of the structure, which is the object of Volume One, and that consequently, as elements of the theory of the complexity of a complex totality, they are for the same reason synchronic.13 On the other hand, and correlatively, the ‘synchrony/diachrony’ opposition presupposes a simple and empty time that offers itself to whatever seeks to immerse its structures in it, to see what happens to them, without requiring any other elaboration than the drawing of a line on a sheet of paper. This is in no way the case in Volume One, and for good reason: from the moment that a temporal law is conceived as structural, it is necessary to produce the concept of its time, and to define the structure of the time on this basis.

Study of Sub-articulation B

This sub-articulation is one of the most evident in Capital, since it depends on two well-known concepts of Marxism: relations of production/productive forces. The theoretical object of Volume One, in fact, has to be subjected to this distinction, by posing the following problem: what combinations have to be effected between the elements of any labour process for it to be both the production of a defined object responding to a definite human need and a process of valorization of capital? In the two parts determined by Subarticulation B, the elements of the combination are the same, i.e., object of labour, means of labour, direct worker and non-worker. Between the two sides, it is the relations by which the combination is effected that change: in the first part, the fundamental relation is that of property, while in the second it is that of possession. It is not hard to foresee that there is a relation of complementarity between the first and second parts of Sub-articulation B. We also know that this relation between productive forces and relations of production, despite being reciprocal, presupposes a principal determination: the productive forces. Now, at this point this relation only muddies things: what Marx begins his exposition with are the relations of production. It is certainly possible to say that if the full cause is equal to the complete effect, then it is appropriate to note first of all the complete effect, in order then to investigate its cause: the ratio cognoscendi following the reverse order to the ratio essendi – as is frequently the case. But this relation would not illuminate in any way the complementarity of the laws partitioned according to Sub-articulation B, since the object of Volume One and the object that the famous texts on the relations between productive forces and relations of production discuss are not the same: these famous texts, despite being vague or general or pedagogic, assert laws of evolution of economic history that turn out, when these famous texts are more precise, to be simply a contribution to the scientific study of laws of coexistence between different modes of production, and of transition from one mode of production to another.14 The relation that exists between productive forces and relations of production is one thing when it is a question of stating the laws of transition from one mode of production to another, an autonomous theoretical domain of Marxist theory. The relation that exists between relations of production and productive forces, when it is a question of establishing the laws of a specific mode of production as a particular labour process, i.e., essentially the definition of this mode of production, which is the object of Volume One, is something else, another autonomous domain of theory, and theoretically prior. The relation that links productive forces and relations of production within the theoretical domain of the famous texts, and that which links them within the theoretical domain of Volume One, may very well have no connection. We must therefore take account of this possibility (i.e., forget the famous texts) in order to think the connection between the two theoretical elements determined by Sub-articulation B. To rigorously define the complementarity between the stated laws of the capitalist labour process as a particular relation of production, on the one hand, and as a particular system of organization of the productive forces, on the other, we shall study the linkage between the two parts.

The first part simply states the scientific definition of the capitalist production process and the laws that result from this definition. For any labour process, whatever it may be from the standpoint of any other relations (in particular the organization of the productive forces), to be defined as capitalist, i.e., producing surplus-value, it is necessary and sufficient that:

1) the synthesis of elements is effected there by purchase and sale: thus, the property relation is determinant;

2) The operator of this synthesis is the non-worker;

3) The non-worker buys from the direct worker, at its value, not his labour but his labour-power.

This set of conditions defines capitalist relations of production, as a relationship between capital and wage-labour; and it makes it possible to conceive surplus-value on the basis of its formative elements, to differentiate two functional elements within capital, and to establish the limits of the relation that connects surplus-value and working-day. This being established, what is the problem (unresolved at this level) that necessitates the examination of a new combination between the same elements? This is not a problem of historical order: it is not a question of investigating, even summarily, the origin of the elements combined here; and so it is not a matter of establishing a causal sequence in which machines would play the role of causes. The unresolved problem is of the same type as that which has just been resolved: defining the capitalist production process on the basis of the structures that make it conceivable. The problem is as follows: how is it possible to define, between the non-worker and the direct worker, a relation that is both one of exploitation (surplus labour as surplus-value) and of freedom (purchase and sale of labour-power)? The object of the second part of Sub-articulation B is to resolve this problem, by showing how a different combination of the same elements is necessary in order to define the capitalist production process. This new combination concerns the technical division of labour, or a certain organization of the productive forces: the fundamental category is that of possession, which connotes separation.15 It allows the following solution to be elaborated: capitalist production relations presuppose a technical organization in which the direct labourer is no longer the possessor of the means of production, and is therefore separated from them. It is a labour process in which the subject of production is not the isolated producer but the collective worker, and in which the technologically regulatory element is no longer the direct worker but the ensemble of means of labour. As a result of this, the problem of freedom and exploitation is resolved: from the moment that the productive forces of a society are organized according to this structure, the worker can only usefully spend his labour-power if he sells this, since it can only be useful on the double condition of being associated with other forces, and of being exercised in the particular conditions of the process (the means of labour). Only the capitalist can effect this synthesis, as owner of the conditions of labour (object and means of labour).16

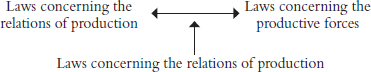

We are now in a position to determine the relative function of the two theoretical elements partitioned by Sub-articulation b. Their object is the same: to define an immediate production process as capitalist. Their result is as follows: it is the unity of the laws concerning the relations of production and the productive forces that allows an immediate labour process to be defined as a capitalist mode of production. It is on the basis of the theoretical function of definition, and of this function alone, that it is possible to conceive simultaneously the unity of the two ensembles of law and the anteriority of one ensemble over the other. The unity of the two ensembles is such that the first set is not completely intelligible without the second, as we have shown. This complementarity can be stated as follows: the capitalist mode of production, as immediate labour process, is the complex structural unity resulting from the unity of two sets of structural laws. It is the relative importance of the unity of the two sets in the theoretical elaboration that determines the priority of one set in relation to the other. In other words, the capitalist mode of production is only definable as the unity of the laws concerning relations of production and productive forces, a unity that can only be defined, in its specific form, on the basis of laws concerning the relations of production.

This can be summed up in the following schema:

We thus establish at the same time, and without contradiction, a relation of complementarity and an order of unambiguous determination between the two parts of Sub-articulation B. This can readily be shown by the whole passage in Part Four in which Marx explains that the forms of technical division characteristic of the labour process under examination are determined by their situation in a structure determined by the relations of production, and whose general theoretical significance is perfectly defined in the text of Volume Three, Chapter 23:

In so far as the work of the capitalist does not arise from the production process simply as a capitalist process, i.e., does not come to an end with capital itself; in so far as it is not confined to the function of exploiting the labour of others; in so far therefore as it arises from the form of labour as social labour, from the combination and cooperation of many to a common result, it is just as independent of capital as is this form, itself, once it has bursts its capitalist shell. To say that this labour, as capitalist labour, is necessarily the function of the capitalist means nothing more than that the vulgus cannot conceive that forms developed in the womb of the capitalist mode of production may be separated and liberated from their antithetical capitalist character (p. 511).

This means that, in order for this to be conceived, the forms developed in the womb of the capitalist mode of production, as unity of relations of production and a socialized organization of the productive forces, have to be defined on the basis of what it is in the capitalist system that gives them ‘their antithetical character’, i.e., the relations of production. There would be no better way to define the theoretical function of Sub-articulation B.

The problem of Part Eight: ‘So-Called Primitive Accumulation’

It may seem surprising that we have not taken any account, in this study of the articulations of Volume One, of one of the most famous texts, ‘So-Called Primitive Accumulation’. This is not because we ignore its importance, rather that the importance of this text pertains to a different theoretical level. The definition of the capitalist mode of production, in fact, i.e., the set of laws governing it as immediate production process, would already be completely accomplished without this text. This is what is presupposed, moreover, by Part Seven, inasmuch as its (autonomous) function consists in transforming the results of Volume One into a scientific problem for another sector of the theory. In fact, by establishing, on the basis of the results of Volume One, not the history but the genealogy of the main elements of the structure, it proposes a well-formulated problem for the theory of transition from one mode of production to another, in particular from the feudal mode of production to the capitalist one. And it should be clearly emphasized that this well-formulated problem does not take the place of this theory; indeed, to take ‘So-Called Primitive Accumulation’ as the theory of the transition to capitalism would amount to conceiving it along the following lines: an autonomous development of the elements followed by their union into a structure. To use one of Pierre Vilar’s17 methodological distinctions: ‘So-Called Primitive Accumulation’ limits itself to presenting the main signs of the phenomenon whose laws the theory of the transition from one mode of production to another is to elaborate, on the basis of the determinism. Since the object of Capital is not to elaborate this theory, despite laying certain foundations for it, we can understand why this Part of Volume One can be put in brackets when it is a matter of establishing and explaining the logical articulations of Capital.

D) The study of Articulation II

The study that we still have to undertake, that of Articulation II,18 is by far the most delicate, as was shown by the text in Volume Three that basically bears on it. We shall try now to bring to the problems it poses a solution that can make no other claim than to propose elements for discussion on a difficult point.

1) New examination of the difficulties raised by Articulation II

In the light of the previous results, we can more clearly formulate the problems posed by Articulation II, i.e., pose them not just by way of a text bearing on them, as we did in explaining the passage in Volume Three, but on the basis of what we already know about the organization of Capital.

The first order of difficulties bears on the unfinished character of Volume Three, an essential theoretical element of Articulation II. These difficulties seem to us minor; they would only be major, or even insoluble, if the incomplete character of Volume Three compromised its coherence. But that is not the case. Volume Three is highly structured, with two clearly distinct parts, the first of these elaborating the laws of the rate of profit (Parts One to Three), and the second elaborating the laws of the distribution of profit (Parts Four to Seven). Now, there is no structure without a principle of organization, either implicit or explicit: it follows from this that if we wanted to know how and why Volume Three was left unfinished (which is not our object here), it would be no help to imagine the continuation of it, as long as the principle of organization of Volume Three has not been defined (which is our object). So, provided that this principle is made clear, we will have defined what makes Volume Three a finished text even though unfinished, and to define its theoretical functioning in Articulation II.

It is clearly the principle that poses major problems. This principle is not explicit in the passages where Marx seeks to present it, either because, as in Volume Three, his presentation lends itself to ambiguities, or because, as in the 1857 Introduction, it cannot be clarified theoretically. One thing however is certain: on the one hand, this principle exists, and on the other hand, it can only be stated in specifically Marxian terms. Before attempting this presentation, we shall reconsider, in the light of the results obtained by studying the earlier volumes, the difficulties proposed by these two texts.

The passage of Volume Three already examined can lend itself to a reading that we have not yet envisaged, because it has not captured the attention of commentators despite having actually guided their reading: i.e. that Articulation II leads us from study of the real structure to study of the appearances of the structure, on the Hegelian model of ‘in itself’/‘for itself’. This reading can draw on the following terms:

In Volume One we investigated the phenomena exhibited by the process of capitalist production, taken by itself [für sich genommen], i.e., the immediate production process […]. The configurations of capital, as developed in this volume, thus approach step by step the form in which they appear on the surface of society […] (p. 117).

We showed in fact, how Volumes One and Two constitute a ‘concrete of thought’ sufficient in itself, and defining the fundamental structures of the capitalist mode of production. Now, Volume Three contains a large number of fundamental passages tending to explain the ‘illusions’ that the agents of production harbour about the structure itself, as a function of their place in the structure. The set of objective laws of Volume Three has no other function than to establish the places in the structure of the illusioned-illusionists, so as to determine the truth or otherwise of their illusions.19 If, however, this reading is inadequate, because it does not account for the fact that the laws of the tendential fall in the rate of profit or of the division of profit are manifestly laws of the structure, new ones, then the possibility of this has to be explained; that is, to determine how the problematic of Articulation II is bound up with the illusions ‘of the ordinary agents of production themselves’.

Determining exactly the new character of the laws of Volume Three, and the object whose laws these are, is the second problem that has to be resolved in order to display the organizing principle of Volume Three. Certainly, the 1857 Introduction can give us an idea of this new object: by moving from Volumes One and Two to Volume Three, we move from the study of the elements of a complex structure, as they reciprocally determine one another, to the laws of the structure itself, as a complete system of determinations. As a consequence of this, whereas the theory in Volumes One and Two can be limited to stating the laws of a ‘fraction of the social capital endowed with individual life’, it must now establish the laws of the social capital considered as a whole. Volume Three will establish new laws, since, as everyone knows, the whole is other than and more than the sum of its parts. Since Durkheim, this knowledge is known as Gestalt-theorie, the mode in which every human science envisages its object. This does not mean that the anticipations of the 1857 Introduction are necessarily a prejudgement, it simply means that its terms are far too vague for defining its terms. It may well be a question of the Whole, but what kind of Whole? It would be very risky not to elucidate the question of the specificity of this Whole, and fall back into the error of microeconomics and macroeconomics that would render one of the fundamental laws established by Volume Three unintelligible, the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit, which implies first of all a relation of the whole to the part that is of the order of a sum. Thus, let SC be the social capital, with V/C its organic composition; and let Fc1, Fc2, Fc3 … Fcn be its fractions ‘endowed with individual life’, with  the respective organic compositions. It is clear that, since

the respective organic compositions. It is clear that, since

SC = Fc1 + Fc2 + Fc3 + … Fcn,

then

Consequently, if we can state for each fraction of the social capital a tendential law concerning the relation  , this will be true by the same token, by simple addition, of the social capital as a whole. Now, this is one of the elements in the elaboration of the law of the rate of profit. As we see, the connection between Volumes One and Two on the one hand, and Volume Three on the other, is not based either on the homology of the part and the whole (the laws of Volume Three are new ones), nor on a qualitative leap without any other determination from the components to the ‘organic totality’.

, this will be true by the same token, by simple addition, of the social capital as a whole. Now, this is one of the elements in the elaboration of the law of the rate of profit. As we see, the connection between Volumes One and Two on the one hand, and Volume Three on the other, is not based either on the homology of the part and the whole (the laws of Volume Three are new ones), nor on a qualitative leap without any other determination from the components to the ‘organic totality’.

Explaining Articulation II, then, means seeking to give a Marxist account of a relation that may be stated, on first analysis, and certainly in an inadequate way, as the relation of the in-itself to the for-itself and as the relation of the elements to the totality. Now, these considerations, together with the problems encountered in connection with Volume Two, are sufficient to authorize a shift in the place of the articulation, in relation to the organization of Capital into volumes. The exact place where the object of Marx’s study changes without our yet knowing why, moving from the laws of the fractions ‘endowed with individual life’ to what can be provisionally stated as study of the laws of the ‘interlinking’ of capitals or of the social capital considered as a whole, is not the start of Volume Three, but rather Part Three of Volume Two:

What we were dealing with in both Parts One and Two,20 however, was always no more than an individual capital, the movement of an autonomous part of the social capital.

However, the circuits of individual capitals are interlinked, they presuppose one another and condition one another, and it is precisely by being interlinked in this way that they constitute the movement of the total social capital (‘Introduction’ to Part Three of Volume Two, p. 429).

Hence, in the text of Volume Three, the special place accorded to this Part (‘particularly in Part Three’, p. 117) and the care that Marx takes in presenting the relation that connects Volume Three to the ‘unity’ established in this part. Marx declares here that the objective of Volume Three is not ‘to expand in generalities about this unity’. What other objective could he have, other than to continue to produce its concept, i.e., the laws? We propose therefore to study Articulation II, making the following division:

Volume One, Parts One and Two of Volume Two/Part Three of Volume Two, Volume Three.

2) The method of solution

If there is a determinable connection between the two elements divided by Articulation II, it should be easy to note. Clearly, Marx does not give a theory of the ‘whole’, of the ‘interlinking’ of ‘capital considered as a whole’, simply for the pleasure of adding the ‘dimension’ of totality to his earlier studies. The necessity of new laws can only be based on the insufficiency of the old ones, not for exhausting the real process, but for being laws in the complete sense. There must exist in Volumes One and Two a theoretical field that is not elaborated but exactly measured, one that the thought process needs, at this level, to neutralize in order to construct the laws of its object. There must consequently exist in Volumes One and Two this minimum of theory, in a form that is consequently problematic and still ideological, of the scientific object of Volume Three. This minimum of theory must, on the one hand, provisionally take its place, and, on the other hand, prove its theoretical necessity. It is this theoretical field, not elaborated but exactly measured, that we shall investigate in Volumes One and Two.

The non-elaborated field of Volumes One and Two, which determines within these volumes the necessity of Part Three of Volume Two and of Volume Three, bears a name which does not yield its cognition, but does circumscribe its recognition: a name that denotes here in relief the empty connection of a new theoretical field: that of competition. We shall now show, from two passages, what this concept permits not to be thought, and what it denotes as having to be thought, at the level of Volumes One and Two.

Here are the two passages:

Volume One, Part Three, Chapter 10:

But looking at these things as a whole, it is evident that this does not depend either on will, either good or bad, of the individual capitalist. Under free competition, immanent laws of capitalist production confront the individual capitalist as a coercive force external to him (p. 381).

Volume One, Part Seven, Chapter 24:

Moreover, the development of capitalist production makes it necessary constantly to increase the amount of capital laid out in a given industrial undertaking, and competition subordinates every individual capitalist to the immanent laws of capitalist production, as external and coercive laws (p. 739).

Let us briefly situate these texts: the first of them brings to an end the examination of the relationship between working-day and profit, in the form of language borrowed from the capitalist; the second is situated between the general presentation of the principles of reproduction (transformation of surplus-value into capital) and the study of its forms.