The artists of the New York School were stylistically diverse, but they shared an interest in developing a new form of abstraction and using it to create art with a strong emotional and expressive impact on the beholder. Many of the artists were inspired by the Surrealist ideal that art should come from the unconscious mind.

Leading the way toward this new art—Abstract Expressionism—were Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko. Although they all largely left figuration behind, each of these artists began as a figurative artist, and each learned a great deal from that experience. In turn, we, as viewers, learn a great deal about the application of reductionist approaches to art by observing how each of these painters forged a path from figuration to abstraction in a distinctive, and often selective, manner.

The art critic Clement Greenberg divided the Abstract Expressionist painters into two groups (1961, 1962): the gestural painters de Kooning and Pollock, and the color-field painters Rothko, Morris Louis, and Barnett Newman. However, as the art historian Robert Rosenblum points out, this distinction is less important than the artists’ common pursuit of the sublime (1961).

The gestural painters were highly investigative in their art and in their abandonment of figuration, much as Piet Mondrian was. In that sense, de Kooning and Pollock were also reductionists. But unlike Mondrian or the color-field painters, de Kooning and Pollock, whose end products are often quite complex, combined their reduction of figuration with a rich painterly background.

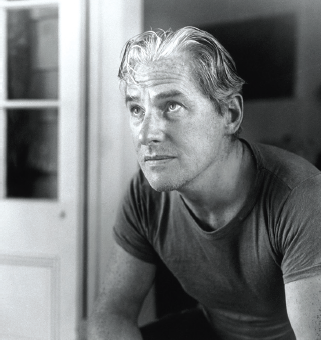

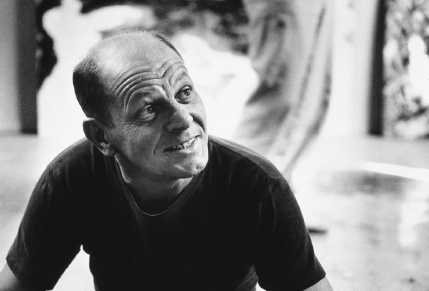

Willem de Kooning (

fig. 7.1) was born in Holland in 1904 and settled in the United States in 1926. He received his early artistic training during eight years at the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts and Techniques. Thus, unlike the other founders of the New York School, he brought a modern European sensibility to the American scene.

7.1 Willem de Kooning (1904–1997)

© Tony Vaccaro / Archive Photos / Getty Images

7.2 Willem de Kooning, Seated Woman, 1940

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

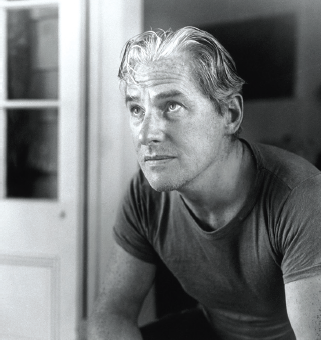

In 1940 de Kooning began painting figurative forms, mostly of women, that combined both Expressionist and abstract tendencies, as evident in

Seated Woman (

fig. 7.2). In the late 1940s and early 1950s his work became more abstract, and he reduced the female figure—an enduring focus of his artistic imagination—to abstract geometric forms, as in

Pink Angels (

fig. 7.3).

7.3 Willem de Kooning, Pink Angels, c. 1945, Oil and charcoal on canvas, 52 x 40 in. (132.1 x 101.6 cm)

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Two of de Kooning’s paintings were of seminal importance in this period:

Excavation (

fig. 7.4) and

Woman I (

fig. 7.5).

Excavation, painted in 1950, is generally considered one of the most important paintings of the twentieth century. Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan (2004), biographers of de Kooning, say that he was caught up in the excitement of the American century and felt he needed to seize the day. They write:

Excavation was first and foremost an excavation of desire. The body was always turning up in the paint, evocatively, but could never be held for long in the eye: the flesh could never be entirely possessed. Any more settled description of the body would have diminished the sensation of physical movement, such as the caress of the hand or a leap of the heart, that was also a vital part of desire.

For decades in Europe, the art of painting had fluctuated between classical reserve and Expressionist impulses, between the rational and the irrational. In particular, it seesawed between Cubism and Surrealism. In de Kooning’s circle, Cubism represented not only a certain way of organizing space but also a responsibility to make a well-constructed picture. De Kooning was keenly aware of his European heritage, and as a painter he was sensitive to the accomplishments of both the Cubists and the Surrealists. The Cubists represented a tradition that went back to Cézanne, while the Surrealists found their authority in private dreams rather than adherence to the past.

In Excavation, de Kooning achieved a magisterial synthesis of these two modern claims on truth. His powerful, poised style integrated the rigorous detachment of Cubist structure with the personal drive and spontaneity of Surrealism. Few paintings in the history of art convey such respect for history, order, and tradition while celebrating the spontaneity of the moment. Moreover, as Pepe Karmel has pointed out (personal communication), in Excavation de Kooning has multiplied and repeated shapes so that they form a consistent, all-over pattern of texture, abolishing the distinction between figure and ground that we see in Pink Angels.

De Kooning gave the synthesis of Cubism and Surrealism a strong American character.

Excavation is brash and pulsating: with the possible exception of Mondrian’s

Broadway Boogie Woogie (

fig. 6.8), no other painting conveys with comparable force the jazzy syncopation of the city. The rhythmic lines lead the viewer’s eye through the painting at different speeds, with the constant stop-start, quick turn, and sudden open spaces of the hooking stroke and the passing glimpses of figurative forms. Color slips beguilingly across our eyes and is lost.

Excavation is a personal improvisation on the great abstract way of modern life in New York City.

7.4 Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In his second important painting of the early 1950s,

Woman I (

fig. 7.5), de Kooning went in a new figurative direction, depicting a vampish, buxom woman embedded in abstraction.

Woman I is clearly designed to be a contemporary American woman, with her toothy smile, high heels, and yellow dress; she is apparently based, at least in part, on Marilyn Monroe (Gray 1984; also see Stevens and Swan 2005).

Woman 1 caused a sensation that, according to the art historian Werner Spies (2011, 8:68), could only be compared to the scandal surrounding Manet’s

Olympia, a painting that challenged the social standards of his time by presenting not an idealized woman, but a sexually available woman who confronts the viewer directly.

7.5 Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950–1952

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Woman I is considered to this day to be one of the most anxiety-producing and disturbing images of a woman in the history of art. In this painting de Kooning, who was reared by an abusive mother, creates an image that captures the divergent dimensions of the eternal woman: fertility, motherhood, aggressive sexual power, and savagery. She is at once a primitive earth mother and a femme fatale. With this image, marked by fanglike teeth and huge eyes that echo the shape of her enormous breasts, de Kooning gave birth to a new synthesis of the female.

7.6 The first known female sculpture, the Venus of Hohle Fels, circa 35,000 B.C.

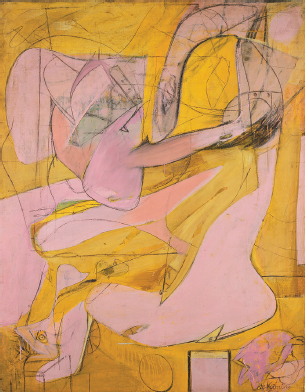

It is interesting to compare

Woman I to the oldest surviving example of a fertility sculpture (

fig. 7.6) and to Klimt’s modern view of female eroticism (

fig. 7.7). The Venus of Hohle Fels, thought to be a fertility goddess, was carved in about 35,000

B.C.E. from a mammoth tusk. She is faceless, and she represents a rather crude exaggeration of the female figure: her vulva, breasts, and belly are pronounced, suggesting a strong connection to fertility and pregnancy. We see some of these exaggerated elements in

Woman I, but the Venus of Hohle Fels lacks the aggression and savagery of the de Kooning painting.

The fusion of eroticism and aggression appears later in Western art. We see it clearly in Gustav Klimt’s seductive, beautiful

Judith, painted in 1901 (

fig. 7.7). Klimt portrays the Jewish heroine fondling Holofernes’ head in a postcoital trance, having first plied the Assyrian general with drink, seduced him, and then decapitated him in order to save her people from the siege he had laid upon them. In his overall body of work, Klimt shows that women, like men, experience a range of sexual emotions, from eroticism to aggression, and illustrates that these emotions are often fused. Despite their differences, both

Judith and

Woman I display considerable sexual power, and remarkably, each woman is depicted showing her teeth.

7.7 Gustav Klimt, Judith, 1901

© Belvedere, Vienna

Today, brain scientists are examining the fusion of aggression and sex that Klimt and de Kooning depicted. In his studies of the neurobiology of emotional behavior, David Anderson at the California Institute of Technology has found some of the biological underpinnings of these conflicting emotional states (

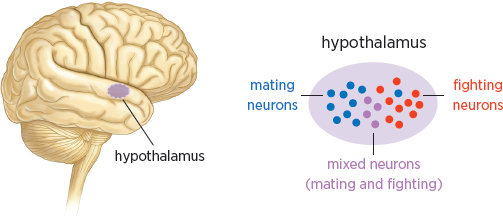

fig. 7.8).

We have seen that the region of our brain known as the amygdala orchestrates emotion and that it communicates with the hypothalamus, the region that houses the nerve cells that control instinctive behavior such as parenting, feeding, mating, fear, and fighting (

chapter 3,

fig. 3.5). Anderson found a nucleus, or cluster of neurons, within the hypothalamus that contains two distinct populations of neurons: one that regulates aggression and one that regulates mating (

fig. 7.8). About 20 percent of the neurons located on the border between the two populations can be active during either mating or aggression. This suggests that the brain circuits regulating these two behaviors are intimately linked.

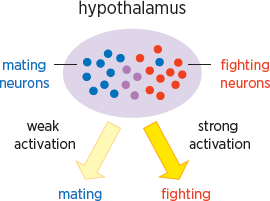

How can two mutually exclusive behaviors—mating and fighting—be mediated by the same population of neurons? Anderson found that the difference hinges on the intensity of the stimulus applied. Weak sensory stimulation, such as foreplay, activates mating, whereas stronger stimulation, such as danger, activates aggression.

In 1952 Meyer Schapiro paid a visit to de Kooning’s studio, where he says he found the artist distraught over Woman I. De Kooning had abandoned the painting after having worked on it for a year and a half. When he pulled it out from under the couch and showed it to Schapiro, the art historian admired it greatly and discussed it in a wide-ranging way that made de Kooning aware of its power. De Kooning concluded not only that the picture was finished but also that it was a masterpiece (Solomon 1994). Peter Schjeldahl, an art critic at The New Yorker who considered de Kooning the greatest American painter and, after Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, the greatest of all twentieth-century artists, referred to Shapiro’s visit as “history’s luckiest studio visit” (Zilczer 2014).

Some art critics, including Greenberg, who thought de Kooning had reached new heights with

Excavation believed that the artist had betrayed abstraction by reverting to a figurative form in

Woman I. In fact, de Kooning was unique among the New York School painters in moving freely from figuration to abstract reductionism and back again, often incorporating both techniques into a single painting. By the 1970s, however, most of de Kooning’s work was fully abstract.

7.8 The hypothalamus contains two groups of contiguous neurons, one group that regulates aggression (fighting) and one that regulates mating. Some neurons at the borders of the two populations (mixed neurons) can activate either behavior (based on data from Anderson 2012).

7.9 The intensity of a stimulus determines which neurons are activated and the resulting behavior of the animal.

While some art critics thought Woman I revealed a misogynist perspective, others, including Spies, saw it and de Kooning’s other paintings of women in the 1950s as representing the archetypal woman: at once primitive, exotic, procreative, and aggressive. For these reasons, Woman I can be considered a visual metaphor for the Abstract Expressionists’ goal of creating a new world from the chaos and destruction of the old.

De Kooning’s work was enthusiastically supported by Rosenberg, who saw the canvas as an arena for action. From his perspective, the Abstract Expressionism of the New York School represented a rupture, a discontinuity in modern art. Greenberg, on the other hand, saw Woman I as one of the most advanced paintings of the time, in part because de Kooning had invested it with the power of sculptural contours derived from the human form. Greenberg therefore saw Woman I as part of a great tradition of craftsmanship that includes artists like da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Ingres, and Picasso (Zilczer 2014).

Under the influence of Chaim Soutine (1893–1943), a Russian-born Jewish Expressionist painter who worked in Paris, de Kooning began to add texture to his abstract paintings, giving the surfaces a richer material appearance and a sculptural quality that evokes a tactile sensibility in the beholder. This tactile quality, which is evident in

Woman I and even more so in later paintings such as

Two Trees on Mary Street . . . Amen! (

fig. 7.10) and

Untitled X (

fig. 7.11), creates an additional source of light, a glow that comes from within the painting. It also illustrates the particular emphasis that abstract art places on texture as well as color. The art historian Arthur Danto (2001) quotes de Kooning as saying—following Titian—that “flesh was the reason oil paint was developed.”

Despite the abstract nature of these paintings, de Kooning later insisted that he was not interested in “abstracting”—taking things out and reducing his paintings to form, line, or color. Rather, he often painted in what appeared to others to be an abstract form because the reduction of figuration allowed him to put more emotional and conceptual components into the painting: anger, pain, love, his ideas about space.

7.10 Willem de Kooning, Two Trees on Mary Street . . . Amen!, 1975

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

De Kooning also created a new compositional device, a variation on the action painting first developed by Pollock. As is evident in the white streaks in

Untitled X (

fig. 7.11), de Kooning varied the “visual” speed of his brush, thus masterfully leading the eye first at one speed and then another. All of these devices are devoid of figurative elements, but they are richly evocative, encouraging the viewer’s eye and mind to explore the surface of the canvas, to feel its textures, and to engage in the provocative play of foreground and background.

7.11 Willem de Kooning, Untitled X, 1976

© 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In evaluating the

viewer’s response to texture in art, art historians have often underestimated the brain’s ability to coordinate the information it receives from different senses. Vision and touch are particularly interrelated, as we have seen. Bernard Berenson was perhaps the first art historian to argue that “the essential in the art of painting [is] . . . to stimulate our consciousness of tactile values” and thus to appeal through texture and edges to our tactile imagination as strongly as the actual three-dimensional object being depicted would (Berenson 1909). He goes on to say that the reduced elements of form—volume, bulk, and texture—are principal elements of our aesthetic enjoyment of art. Berenson was referring to the creation of tactile sensibility through illusions, such as shading and foreshortening. When we view a painting by de Kooning or Soutine, however, our visual sensations are translated into sensations of touch, pressure, and grasp by the three-dimensional surface of the paint itself (see also Hinojosa 2009). Thus abstraction of a visual element, combined with its tactile appeal, can enrich our aesthetic response even further.

De Kooning, more than any other American artist of the twentieth century, altered the vocabulary of painting and even the notion of what painting is about (Spies 2010). But because he never completely abandoned figuration, it was Pollock who, according even to de Kooning, “really broke the ice.” Pollock proved to be, by far, the strongest personality of his generation. As de Kooning put it: “Every so often, a painter has to destroy painting. Cézanne did it. Picasso did it with cubism. Then Pollock did it. He busted our idea of a picture all to hell. Then there could be new paintings again” (Galenson 2009).

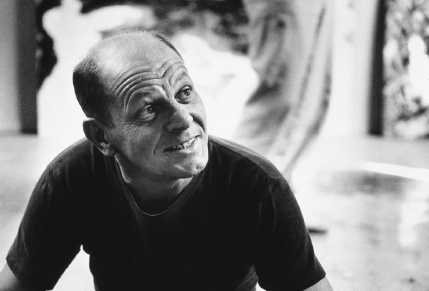

Jackson Pollock (

fig. 7.12) was born in Cody, Wyoming, in 1912. In 1930 he moved to New York City to live with his brother Charles, who was an artist. Pollock soon started to work with Thomas Hart Benton, a leading American regionalist painter who was also his brother’s art teacher.

Early in his career Pollock, like Rothko and de Kooning, painted Expressionist figures. Under Benton’s influence, his early style featured swirling patterns that bear some resemblance to Turner (

fig. 7.13; also see

fig. 5.3). But in 1939 Pollock encountered Picasso’s work at an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Picasso’s artistic experiments with Cubism stimulated Pollock to start experimenting on his own. In this effort he was also influenced by the Spanish Surrealist painter and sculptor Joan Miró and by the Mexican painter Diego Rivera.

By 1940 Pollock had moved to abstract painting, with only residual figurative elements. This is evident in

The Tea Cup (

fig. 7.14), a painting that abandons perspective and balances figuration and abstraction. The beauty and intrigue of

The Tea Cup likely stems from the fact that the painting is laden with meaningful symbols (which require top-down visual processing) that also relate meaningfully to each other. The painting is textured, but it has flat areas of color and looping black lines.

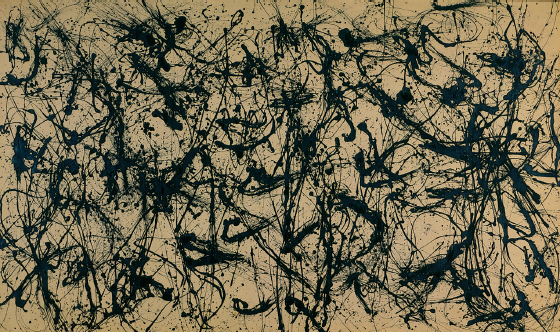

Having achieved considerable recognition with these abstract works, Pollock went on between 1947 and 1950 to develop a new method of painting, one that revolutionized abstract art. He took the canvas off the wall and put it on the floor. In doing this, he was following the lead of Native American Indian sand painters in the Southwest, whose traditional works he had become familiar with during his boyhood in Wyoming (Shlain 1993). Abandoning both figuration and the conventional method of painting, Pollack developed a new reductive approach. He poured and dripped paint onto the canvas using not only brushes but also sticks—drawing in space, so to speak. In addition, he moved around the canvas so as to be able to work on every part of it. Finally, Pollock stopped applying names to his paintings and now just gave them numbers, so that the beholders would be free to form their own opinion of the work of art without being biased by the title of the work. This radical approach, which focused on the act of painting, was appropriately called

action painting (

figs. 7.15,

7.16).

7.12 Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) at his Springs studio in East Hampton, New York State, August 23, 1953

© Tony Vaccaro/ Archive Photos / Getty Images

7.13 Jackson Pollock, Going West, 1934–35

© 2016 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The term “action painting,” introduced by Rosenberg (1952), conveys the process of creation. Pollock argued that the act of painting has a life of its own, and he tried to let it come through. “On the floor,” he stated, “I am more at ease, I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and be literally ‘in’ the painting” (Karmel 2002). Pollock’s action paintings are dynamic and visually complex, and his execution of them required great expenditures of energy.

7.14 Jackson Pollock, The Tea Cup, 1946

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

At first glance, it may be difficult to discern reductive elements in Pollock’s extremely complex action paintings, but he in fact made two important reductionist advances. First, he abandoned traditional composition: his works do not have any points of emphasis or identifiable parts. They lack a central motif and encourage our peripheral vision. As a result, our eyes are constantly on the move: our gaze cannot settle or focus on the canvas. This is why we perceive action paintings as vital and dynamic. Second, Pollock’s action paintings introduced what Greenberg referred to as a “crisis” in easel painting: “The easel painting, the movable picture hung on a wall, is a unique product of the West, with no real counterpart elsewhere. . . . The easel picture subordinates decorative to dramatic effect. It cuts the illusion of a box-like cavity into the wall behind it, and within this, as a unity, it organizes three-dimensional semblances” (Greenberg 1948).

7.15 Jackson Pollock, Composition #16, 1948

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

7.16 Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Greenberg went on to argue that the essence of easel painting was first compromised by Picasso and Alfred Sisley and that artists like Pollock continued on the path to destroy it. “Since Mondrian,” wrote Greenberg, “no one has driven the easel picture quite so far away from itself.” The dissolution of pictorial images into sheer texture—into apparently pure sensation—through an accumulation of repetition seemed to Greenberg to speak to something profound in contemporary sensibility.

Pollock himself saw drip painting as a reductionist approach to art. In abandoning figuration, he felt that he had removed constraints on his unconscious and the creative process. As Freud had pointed out years earlier, the language of the unconscious is governed by “primary process” thinking, which differs from the secondary process thinking of the conscious mind in having no sense of time or space and in readily accepting contradictions and irrationality. Thus, in reducing conscious form to an unconsciously motivated drip-painting technique, Pollock showed remarkable inventiveness and originality. As part of a 1998 retrospective of Pollock’s work held by the Museum of Modern Art, Kirk Varnedoe, a curator of the event, wrote: “Pollock has been admired as a great eliminator . . . . But, like the best of modern art, it also has tremendous generative, and regenerative, power” (Varnedoe 1999, 245).

Pollock seems to have grasped intuitively that the visual brain is a pattern-recognition device. It specializes in extracting meaningful patterns from the input it receives, even when that input is extremely noisy. This psychological phenomenon is referred to as pareidolia, in which a vague, random stimulus is perceived as significant. Da Vinci writes of this capability in his notebooks:

If you look at any walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones, if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and various groups of hills. You will also be able to see divers combats and figures in quick movement, and strange expressions of faces, and outlandish costumes, and an infinite number of things which you can then reduce into separate and well-conceived forms. (Da Vinci 1923)

Thus Pollock’s

work speaks to a profound question: How do we impose order on randomness? This is a question that Kahneman and Tversky explored extensively in their collaborative work (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Tversky and Kahneman 1992), which led to a Nobel Prize in economics for Kahneman in 2002 (Tversky died in 1996). They showed that when confronted with a choice that has low probability—approaching randomness—our top-down cognitive processes impose order on the choice so as to decrease the uncertainty. This is what the beholder of an action painting often does—looks for a pattern in random splatters of paint.

Pollock’s intelligence is often described as an intelligence of the body. His first dealer, Betty Parsons, speaks of him in the following terms:

How hard Jackson could work, and with such grace! I watched him and he was like a dancer. He had the canvas on the floor with cans of paint around the edges that had sticks in them, which he’d seize and—swish and swish again. There was such rhythm in his movement. . . . [His compositions] were so complex, yet he never went overboard—always in perfect balance. . . . The best things in the great painters happen when the artist gets lost . . . something else takes over. When Jackson would get lost, I think the unconscious took over and that’s marvelous. (Potter 1985)

By superimposing one layer of paint on another and by applying thick paint squeezed from a tube to his canvas, Pollock succeeded in creating a tactile sensation (

fig. 7.16). This sense of texture is heightened by interweaving and overlapping lines of color. In later paintings he also created texture through the use of

impasto, a technique that consists of applying thick paint with a brush or a paint knife. Because Pollock’s brushwork is so agitated, his technique of applying thick impasto over textured surfaces creates an almost three-dimensional, sculptural quality, a technique introduced into art by Vincent van Gogh. In his essay “American Action Painters,” Rosenberg wrote that Pollock, by turning painting into a series of actions, had “eliminated the separation between art and life.”