In the electric age, when our central nervous system is technologically extended to involve us in the whole of mankind and to incorporate the whole of mankind in us, we necessarily participate, in depth, in the consequences of our every action. It is no longer possible to adopt the aloof and dissociated role of the literate Westerner. … As electrically contracted, the globe is no more than a village.

MARSHALL MCLUHAN, Understanding Media

The world of the future might be like Japan is today—superflat. Society, customs, art, culture: all are extremely two-dimensional. It is particularly apparent in the arts that this sensibility has been flowing steadily beneath the surface of Japanese history. Today the sensibility is most present in Japanese games and anime, which have become powerful parts of world culture. One way to imagine superflatness is to think of the moment when, in creating a desktop graphic for your computer, you merge a number of distinct layers into one. … The feeling I get is a sense of reality that is very nearly a physical sensation.

MURAKAMI TAKASHI, “The Superflat Manifesto”1

Is the world round or flat in the age of new media? Is it closer to the “global village” envisioned by the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan in 1964 or the “superflat” Japan described by the Japanese artist Murakami Takashi in 2000? This chapter investigates how discourses of globalization function in the digital era by turning to the remarkably popular phenomenon of Japanese horror films in the 1990s and 2000s (a renaissance commonly referred to collectively as “J-Horror”) and their American remakes. I will argue that these extraordinary interchanges between East and West at the levels of genre, culture, and economics demand that we rethink what characterizes “dominant” and “subaltern” global media flows. In other words, I want to suggest that the networks established between these Japanese and American horror films present us with a haunted-house version of McLuhan’s global village, one where Murakami’s superflat Japan stages globalization as an unsettled and unsettling confrontation between histories and technologies, past and present, remembering and forgetting. At the crux of this confrontation stands surrealism, functioning within globalization’s mediated unconscious.

Discussions of cinema in the age of new media have focused increasingly on issues of globalization, an umbrella term that tends to incorporate trends often more accurately described as transnational or international.2 Still, the existence of computerized, digitized means of production and distribution have altered our conventional sense of “world cinema”—our awareness of it and desire for it—even if many of the obstacles to making and seeing films from off the beaten path (whether geographically or aesthetically) remain firmly in place or have grown even more daunting in the digital era, at least in the theatrical context.3 At this point most scholars agree that globalization is synonymous with neither cultural standardization nor cultural diversification in any absolute sense. Instead, concepts such as “dominant global flows” and “subaltern contra-flows”4 emerge to describe a worldwide media economy that is becoming “more diverse through standardization and more standardized through diversification.”5

According to Arjun Appadurai, the key to defining what makes globalization “strikingly new” in the past century or so is “a technological explosion, largely in the domain of transportation and information, that makes the interactions of a print-dominated world seem as hardwon and as easily erased as the print revolution made earlier forms of cultural traffic appear.”6 For Appadurai the centrality of media such as cinema, television, and computers to the new global cultural economy demands that we shift our understanding of globalization from standard center-periphery models, where concepts such as Americanization have explained how the center dominates the periphery, to a more “disjunctive” sense of globalization. In disjunctive globalization, global flows move in multiple, uneven, and idiosyncratic directions simultaneously, not just from the center to the periphery. “The complexity of the current global economy,” concludes Appadurai, “has to do with certain fundamental disjunctures between economy, culture, and politics that we have only begun to theorize.”7

What does the case of J-Horror films such as Ring (Nakata Hideo, 1998),8 Kairo (Kurosawa Kiyoshi, 2001), Honogurai mizu no soko kara (Nakata Hideo, 2002), Ju-On (Shimizu Takashi, 2003), and Chakushin ari (Miike Takashi, 2004), along with their respective American remakes The Ring (Gore Verbinski, 2002), Pulse (Jim Sonzero, 2006), Dark Water (Walter Salles, 2005), The Grudge (Takashi Shimizu, 2004), and One Missed Call (Eric Valette, 2008), have to tell us about this new global terrain? In this chapter I will limit my discussion to Nakata’s Ring and Verbinski’s The Ring, but I believe many of my observations can be extended to the other J-Horror films as well, including the many sequels, prequels, and offshoots attached to them.

A RING OF MEDIATED GLOBALIZATION

Ring, based on a 1991 novel of the same name by Suzuki Koji and adapted for the screen by Takahashi Hiroshi, tells the story of a curse originating with a murdered girl named Sadako (Inou Rie). From beyond the grave Sadako wreaks revenge on the world for her death by channeling her fearsome psychic powers into disturbing, mysterious images transmitted first by television and then by videotape. These images will kill whoever watches them precisely one week after first seeing them, unless the viewer succeeds in expanding the curse’s “ring” by copying the deadly videotape and exposing a new victim to Sadako’s images. The film follows the efforts of the reporter Asakawa (Matsushima Nanako) and her psychically gifted ex-husband, Ryuji (Sanada Hiroyuki), to interpret the images on the videotape. Understanding Sadako’s images is a matter of life and death, as they have both been exposed to the curse along with their young son, Yoichi (Otaka Rikiya).

The film begins with a sequence that immediately locates viewers within the discursive realm of mediated globalization. Ring’s first images present a dark sea that disintegrates into televisual static before resolving into the broadcast of a Japanese baseball game. By juxtaposing the sea, Japan’s ancient natural barrier to global trade, with television, a modern media platform for globalization and an example of Japan’s worldwide success in the electronics industry, Ring establishes the connections and the tensions between modern and premodern, domestic and global that will haunt the entire film. The fact that the televisual signal takes shape as a game of Japanese baseball locates these connections and tensions specifically within global coordinates designated by Japan and the United States. Baseball, America’s “national pastime,” first appeared in Japan in the 1870s and has since become a significant example of the cultural and economic ties linking the two countries, with players and business passing between Japan and America in both directions.9

The two Japanese teenagers Masami (Sato Hitomi) and Tomoko (Takeuchi Yuko) do not watch the game with any sort of focused attention, but the mise-en-scène suggests that they do not need to: the global flows that characterize Japanese baseball have already spilled onto their clothing and surroundings. American brand names such as Pro-Keds, Ritz, and Planters can be detected among the Japanese dolls, books, and magazines that fill Tomoko’s home, adding to the impression generated by the televised baseball game that the mediated terrain we have entered is globalized; it is marked by cultural disjunctures enabled by media technology, where there are no definitive means to distinguish the purely Japanese from the purely American. When Masami tells Tomoko about a legend she has heard that involves a cursed videotape, an ominous phone call, and then death for the viewer one week later, Tomoko admits that she watched a strange videotape herself almost exactly one week before. When the phone rings, its piercing tones terrify both girls—is it the enactment of the curse?

The caller turns out to be Tomoko’s mother, telling her daughter that the baseball game she is attending has gone into extra innings so she will be late coming home. The relief the two girls feel when they learn the caller’s identity does not entirely reassure the viewer, because we already feel caught in a claustrophobic media web. Is the game on television the same one Tomoko’s mother attends? Is the legend of the cursed videotape told by Masami the same one experienced by Tomoko? Can the phone that carries Tomoko’s mother’s voice also carry the power of the curse? In each case a technological medium (television, videotape, telephone) offers the promise of shared experience while simultaneously conveying the threat of suffocation and infection. Indeed, soon after Tomoko hangs up the phone, the television in the adjoining room switches on to the baseball game of its own accord, making the sounds and images that should comfort us through their familiarity and their association with Tomoko’s mother seem uncanny.10 Even though Tomoko then turns off the television, it is ultimately the television that turns off Tomoko; something unseen emerges from the television to claim her, and her dying scream is captured in a frozen, black-and-white image that resembles a photographic negative (fig. 3.1).11

The conversion of Tomoko into a kind of photograph completes the equation suggested throughout the entire opening sequence: death = becoming mediated. The photograph, like the television, videotape, and telephone, exceeds its everyday function as communicator between people over time and space. These media, all so central to processes of globalization, establish a deadly “ring” of mediation that consumes people rather than connects them. The ring tightens the world around media users, instead of expanding it, to the point where finally there is no more media user; there is only the media itself. In this ring of mediation McLuhan’s global village comes to life in nightmare form: the technologies that promise to erase boundaries between people scattered across the globe fulfill their promise—only too much so. It is not just the boundaries that are erased but the people themselves as well.

So where is cinema in this ring of mediation? Is Ring simply another example in a long line of films stretching from cinema’s beginnings to its present that express technophobia toward rival media while consolidating film’s own status as a medium to be trusted?12 I believe the intertextual and international language of the horror genre functions to implicate cinema within this haunted ring of mediation rather than to exonerate it. If Ring’s opening sequence teems with images that wed mediation to globalization, particularly in relation to Japan and America, then its generic references weave another layer in this tapestry of images. The themes of curses and ghosts reach back to Japanese folklore, as well as to a rich Japanese cinematic tradition that includes films such as Ugetsu monogatari (Ugetsu, Mizoguchi Kenji, 1953), Tokaido Yotsuya kaidan (Ghost Story of Yotsuya, Nakagawa Nobuo, 1959), Kwaidan (Kobayashi Masaki, 1964), and Onibaba (Shindo Kaneto, 1964).13 At the same time, the trope of a haunted television is familiar from North American horror films such as Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982), the threatening telephone call from When a Stranger Calls (Fred Walton, 1979) and Scream (Wes Craven, 1996), and the “living” videotape from Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983).14 Indeed, my interviews with Nakata Hideo and Takahashi Hiroshi (which I will return to throughout this chapter) reveal an extraordinarily diverse array of films and directors that influenced their work on Ring: The Haunting (Robert Wise, 1963), The Innocents (Jack Clayton, 1961), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1983), Sergei Eisenstein, Joseph Losey, Nakagawa Nobuo, and Luis Buñuel.15 In short, Ring presents cinema alongside the photograph, television, telephone, and videotape as media haunted by globalization.

In terms of the particular globalization effects that Murakami dubs “superflatness,” where a number of different cultural layers are merged into one and the rest of the world comes to resemble Japan more and more, Ring and its American remake together provide a vividly “superflat” global portrait: a simultaneously “Japanized” America and “Americanized” Japan that belongs to both nations but is not fully locatable in either. If globalization’s disjunctures emanate largely from media technologies, then the mediated networks between these films could connect a series of images that exceed the conscious intentions of their Japanese or American filmmakers. Appadurai reminds us of how difficult it is to map globalization’s disjunctures, especially since the coordinates of center and periphery no longer anchor us as they used to. He points out how one symptom of globalization is that “the past is now not a land to return to in a simple politics of memory. It has become a synchronic warehouse of cultural scenarios.”16

The mediated unconscious is one way to imagine these conditions of globalization: media technologies crisscross at such rapid speeds, in such unpredictable directions, that images once consciously relegated to the particular past of a specific nation now materialize as the unconscious visual present of another nation, or between nations. These images belong to the domain of globalized mediation, where histories, aesthetics, and politics may take shape visually as an expression of a mediated unconscious. Murakami’s superflatness, like the mediated unconscious, is an attempt to map globalization in new ways, with new cultural coordinates. But both models, like McLuhan’s global village before them, risk collapse into an ahistorical fantasy realm where new technology is fetishized and political conflict is minimized. One vital aspect of Murakami’s project that resists such collapse comes into focus when it is juxtaposed with the mediated unconscious: its kinship with surrealism. In a major 2005 exhibition of postwar Japanese popular culture (anime, manga, film, television, toys, figurines) as/through contemporary Japanese art curated by Murakami, history comes to the fore with the aid of surrealism in order to expand the superflat project. By turning to this exhibition, entitled Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture (held at the Japan Society Gallery in New York), we move toward a theoretical framework that can situate the mediated globalization of Ring and its remake alongside surrealism and history.

THE LITTLE BOY OF HISTORY

In the exhibition catalog Murakami calls Little Boy the third and final chapter in his “Superflat Trilogy,” a series of exhibitions and accompanying publications commencing with Superflat in 2000 and continuing with Coloriage in 2002. According to Murakami, the superflat project grew out of a desire to define postwar Japanese art and culture: “Postwar Japan was given life and nurtured by America. We were shown that the true meaning of life is meaninglessness, and were taught to live without thought. Our society and hierarchies were dismantled. We were forced into a system that does not produce ‘adults.’ The collapse of the bubble economy was the predetermined outcome of a poker game only America could win. Father America is now beginning to withdraw, and its child, Japan, is beginning to develop on its own.”17

In this passage from the Little Boy catalog, where Murakami quotes his own 1999 essay “Greetings, You Are Alive: Tokyo Pop Manifesto,” he suggests that one way to interpret the term little boy is as a metaphor for postwar Japan, with America as a father figure. But, of course, “little boy” also calls to mind the codename for the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945—a connotation highlighted by the exhibition’s use of “exploding” in its subtitle.

As one becomes more fully acquainted with the exhibition, “little boy” and “exploding subculture” take on additional meanings. The opening plate in Little Boy’s catalog is a photograph of the Japanese surrealist artist Okamoto Taro posing in front of his gigantic sculpture Tower of the Sun (1969), the centerpiece of the 1970 World’s Fair (Expo ’70) held in Osaka. The text that accompanies this photograph, in both Japanese and English, is a signature phrase of Okamoto’s: “Art is explosion!”18 Murakami’s decision to foreground Okamoto in this way, as a sort of guiding spirit who presides over Little Boy, underlines how the exhibition’s context takes shape at the crossroads of globalization (the World’s Fair), surrealism (Okamoto), and history (the “explosion” of art inseparable from World War II’s atomic explosions).

Another “little boy” who stands at this crossroads is the otaku, a diehard fan (almost always male) devoted to Japanese anime, manga, and other “lower” forms of Japanese popular culture. The culture of the otaku is the “subculture” referred to in Little Boy’s subtitle, and a conversation between Murakami and two experts on the otaku phenomenon, Okada Toshio and Morikawa Kaichirō, is included in the catalog.19 Although opinions vary widely on exactly how to define otaku and what stands inside and outside this subculture, one might say that generally otaku has undergone a transformation from a largely negative designation to a somewhat positive, even respectable one. The negativity encompasses connotations of social ineptitude, regressive immaturity, and nonproductivity, while the positive aspects touch on authentic art, international influence, commercial success, and cultural power. Murakami’s art is itself an important example of how the materials of formerly denigrated otaku culture can be reworked as critically and financially successful contemporary art—even if Murakami describes himself as having “failed to become an otaku.”20

The lucrative export business and international acclaim generated by Japanese anime, manga, video games, and other popular culture objects, including horror films (to the point where many Western fans proudly identify themselves as otaku), figures centrally in Japan’s transition from economic superpower to “cultural superpower” in the recessionary 1990s.21 In fact, the bursting of the Japanese bubble economy in the early 1990s has been understood as “epochal,”22 as a moment when “the image of Japan, built up over decades, as a nation of unending economic expansion” crumbles so seriously that what is signaled socially and culturally may be nothing less than “the long-deferred end of the postwar.”23 Certainly this is how Murakami sees the “superflat” context of his own work, if we recall how he traces his project to an era marked by “the collapse of the bubble economy,” as well as the ascension of “Japanese games and anime, which have become powerful parts of world culture.”24 In other words, Murakami’s superflat project materializes at a time when Japan’s long postwar, with its emphasis on economic growth as a guarantee of an endless present that affords precious little opportunity to reflect on the wartime past, gives way to a prolonged economic downturn that challenges Japan to rethink its relation to the past, present, and future under the banner of globalization.

I do not wish to refer to this recessionary era as “post-postwar,” with its suggestion that World War II and its aftermath are somehow transcended during this time; in fact, as J. Victor Koschmann observes, “deeply rooted in the culture of Japan’s recession of the 1990s are insistent issues of Japanese war responsibility and compensation. … In the course of the decade, significant connections have emerged between issues of war guilt and the question of Japanese nationalism.”25 Indeed, the global success of Japanese popular culture, “as one of the few bright spots in the nation’s bleak economic landscape since the 1990s,” has resulted in domestic political use of “the emergent image of ‘cool’ Japan abroad in order to boost the sagging national self-confidence.”26 The Japanese right has sought to capitalize on this circumstance in a number of ways, including advocating less “masochistic” portrayals of wartime Japanese history. The history textbook revision efforts associated with noted manga creator Kobayashi Yoshinori, “honorary director” of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform, have been incisively summarized by Marilyn Ivy: “only by justifying the war—and by sharing out atrocity under erasure—can Japan revivify its moribund national body.” Ivy points out how this textbook revision strategy depends on the logic of “no worse than,” where Japanese war crimes are “no worse than” those committed by other nations and therefore “the fact that monstrosity is shared, that it is international, should pay for its erasure: we are not monsters.”27

At some level Murakami seems to sense the nationalist dangers produced at this intersection of Japan’s economic fall and cultural rise—the globalized intersection where his superflat project resides. He concludes his summary of the “Superflat Trilogy” in the Little Boy catalog with words that seem designed to counter, or at least provide an alternative to, the kind of conservative history textbook reform underwritten by Kobayashi: “We are deformed monsters. We were discriminated against as ‘less than human’ in the eyes of the ‘humans’ of the West. … The Superflat project is our ‘Monster Manifesto,’ and now more than ever, we must pride ourselves on our art, the work of monsters. … Only by knowing the meaning of history can we sense that we are alive now.”28 Murakami’s formulations are not free from nationalist sentiment, nor do Little Boy’s accounts of World War II ever really move beyond Japanese atomic victimhood. But by embracing “monstrosity” rather than denying it, Murakami opens a window for negotiating “the meaning of history” that Kobayashi closes. Chief among the elements passing through this open window is surrealism.

EXPLOSIVE SURREALISM

To return to where Little Boy begins: Okamoto’s phrase “Art is explosion!” was made famous when the surrealist artist appeared in a popular Japanese television commercial for Hitachi Maxell videocassettes. The catalog description of Little Boy’s opening plate dedicated to Okamoto (an entry edited by Murakami) draws attention to this fact, as well as to how Okamoto’s artistic sensibility was formed during the years he spent in France (1928–40) as an associate of the surrealists and related figures, including Georges Bataille.29 This is not the first time surrealism has been on Murakami’s mind, as one of his own series of paintings produced in 1999 bears the title PO + KU Surrealism.30 By beginning with Okamoto, Little Boy foregrounds the junctures of surrealism and electronic media, of Japanese art and Japanese commerce, of globalization and history. These are the same junctures crucial for understanding Nakata’s Ring, Verbinski’s The Ring, and the forces of mediated globalization that traverse the two films.

Indeed, there are certain ways in which the cursed videocassettes of Ring, imprinted with Sadako’s surrealist-style series of discontinuous images that document a monstrous crime committed in the past, perform a nightmare version not only of McLuhan’s global village but also of Okamoto’s Hitachi Maxell videocassettes. In Ring the “explosion” of “art” crystallized by surrealist-style images transmitted by videotape means that a haunted past has come to claim lives in the present. By having its curse recorded and played on videotape, Ring also allegorically suggests that the electronic products that epitomized Japan’s economic strength in the 1980s, such as televisions, VCRs, and videocassettes, no longer “work” in the recessionary 1990s. What used to bring prosperity now brings death; what used to safeguard a never-ending present now insists on returning to a repressed past.

Again, I am not suggesting that Nakata and Takahashi consciously intended to present the media technologies that saturate Ring as signs of the contemporary recession or a revisiting of the wartime past. But the film’s fascination with media indicates powerful connections to globalization’s mediated unconscious. For Takahashi one of Ring’s influences was his own earlier experience with what we might call in retrospect an instance of the mediated unconscious:

World War II is very important to me, even though I did not live through it myself. In the 1960s, my generation watched a lot of special-effects-filled Japanese TV dramas that were made by people who experienced the war. These TV programs were not pro-war or anti-war, but the things that the people who made them saw during the war were reflected in the programs themselves, often in quite horrifying ways. These programs were science fiction, like The Outer Limits. But while watching them, you could still feel a sense of guilt about the war behind them. And that feeling is quite important when it comes to making horror films.31

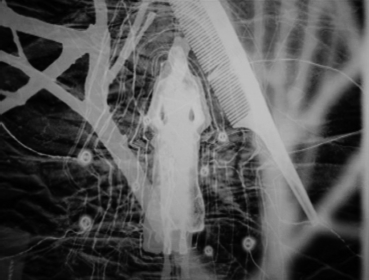

Takahashi’s associations with television as a conduit between the trauma of the past and the life of the present gains a striking analogue in Ring through Sadako’s deadly videotaped images, which always appear on television screens or monitors.32 Television’s role as a passageway connecting past and present becomes terrifyingly literalized during the film’s climax, as Sadako lurches out of the TV screen to kill Ryuji in his apartment (fig. 3.2). Although Sadako’s images begin as surrealist-style abstractions, they are eventually translated as clues that help uncover her hidden murder many years earlier. And in the end these images are transformed into a manifestation of Sadako herself—equal parts ghostly and material, recorded videotape and live television, then and now.

It is important to recognize how Ring connects the “then” of World War II to the “now” of Japan’s 1990s recession. For Takahashi memories of World War II, like Sadako herself, came through the television. Another traumatic televisual image that makes its way onto Sadako’s videotape in allegorical form is the figure of Miyazaki Tsutomu. When Miyazaki was arrested in 1989 and convicted for kidnapping, murdering, and partially devouring four young girls, TV footage depicted him pointing to the site where he committed his crimes, with a white jacket over his head to conceal his identity. The image of a pointing, hooded figure also appears on Sadako’s videotape (fig. 3.3), an intentional allusion on the part of Takahashi and Nakata that gains additional force when one considers Miyazaki’s title in the Japanese news media as “The Otaku Murderer.” In addition to the corpses of the girls he killed, police discovered thousands of videotapes in Miyazaki’s possession associated with the otaku subculture, namely “his collection of anime and horror films.”33

As Nakata explains:

Takahashi and I spent a night going over a detailed description of each shot [on Sadako’s videotape], and he recalled some weird images from manga as well as of the child killer Miyazaki, who was … my age. When he was taken to the crime scene, he was asked where he killed the girls. He pointed to the ground, like this [gesturing with one arm outstretched], and on his head was a white jacket. It was not exactly the same in the film, but that image itself impressed me and Takahashi when we were watching the news. It was … an eerie, haunting image.34

Takahashi concurs: “My generation was very much influenced by the horrible case of Miyazaki Tsutomu. … That crime, for my generation, had a deep impact.”35 The generation-defining aspect of Miyazaki’s crimes for both Takahashi (born in 1959) and Nakata (born in 1961) places Miyazaki alongside the recession, even though his arrest predates the bursting of the bubble economy. The fact that Miyazaki’s presence finds its way into Ring nearly ten years later supports this connection, as does Takahashi’s belief that, at least in retrospect, Miyazaki must be understood in conjunction with the traumatic national events of 1995 (also the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II) that helped make J-Horror possible commercially:

The crucial year for J-Horror was 1995. Up until then we were not having much success producing these films. But after 1995 everything went more smoothly. 1995 was the year of the Kōbe earthquake and of the Aum Shinrikyō sarin gas subway attacks in Tokyo. So for us 1995 is a very memorable year in terrible ways. … The J-Horror group [Takahashi, Nakata, director Kurosawa Kiyoshi, director Tsuruta Norio, and screenwriter Konaka Chiaki] already understood that the world was changing in the 1980s, with Miyazaki and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Then there was the dissolution of Nikkatsu Studios in 1993 or so. But after Aum especially, Japanese people had to face a new reality, where impossible things can become very possible. Even Japanese film studios, who do not tend to accept change, had to face this.36

To summarize: Miyazaki’s identity as “The Otaku Murderer” has, over time, made him a generational icon for Japan’s recessionary era—the disturbing face of Japan’s transition from economic to cultural (otaku-linked) superpower. When Takahashi maps Miyazaki onto events coinciding with the heart of the recession (the Kōbe earthquake, Aum Shinrikyō)37 and massive changes in the Japanese film industry (the collapse of Nikkatsu, the birth of J-Horror),38 he maps the relations that combine to forge a “new reality” for Japan. And it is this map that can be glimpsed in the images on Sadako’s videotape.

According to Nakata, Takahashi came up with a “genius” formulation that guided them in the visual realization of Sadako’s images: “We should try to make images like those in a blind person’s dream.” But even though Nakata and Takahashi discussed their desire before filming to steer clear of images that might seem too obviously “surrealist,” Nakata admits, “Actually, a blind man’s dream and surrealist artists’ paintings and movies are kind of similar things.”39 In both Ring and Little Boy the specter of history touches on the intertwined legacies of World War II, surrealism, and the recession. The art historian Sawaragi Noi develops one strand of these legacies in his contribution to the Little Boy catalog, an essay that claims contemporary Japanese Neo Pop art like Murakami’s, with its foundations in postwar Japanese popular culture, affords an invaluable opportunity to reassess the connections between Japanese art and World War II. For Sawaragi, Japanese Neo Pop “has re-imagined Japan’s gravely distorted history, which the nation chose to embrace at the very beginning of its postwar life by repressing memories of violence and averting its eyes from reality.” Even if Murakami’s generation of artists vacillate “between the desire to escape from historical self-withdrawal and to revert to it,” Sawaragi asserts that Japanese Neo Pop’s fascination with postwar Japanese popular culture demonstrates an engagement with World War II missing (or erased) from more canonical Japanese art.40

For example, Sawaragi finds Japanese Neo Pop’s embrace of World War II–themed anime, model kits, television programs, and films such as Gojira (Godzilla, Honda Ishiro, 1954) in stark opposition to Japan’s continuing reluctance to exhibit “war paintings” dating from World War II by a number of important Japanese artists. These war paintings depict Japanese military campaigns for propaganda purposes and were commissioned by the Japanese government during the war. Although these paintings were confiscated by U.S. authorities at the war’s end, they were returned to Japan in 1970 as an “indefinite loan” and have yet to be exhibited together as a whole for the public. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, at which the collection of 153 surviving war paintings is deposited, usually displays only three at any one time in its gallery.41 As Sawaragi concludes, “an important chapter of Japanese modern art history thus remains unwritten.”42

Among the prominent artists who made war paintings was the surrealist pioneer Fukuzawa Ichiro. Prior to obliging the government’s request for war paintings, Fukuzawa, along with the surrealist poet-critic Takiguchi Shūzō, was arrested in 1941 “under suspicion of collaboration with international communism.”43 After undergoing several months of criminal investigation and detention, Fukuzawa and Takiguchi were released but remained under surveillance. Fukuzawa was forced to recant publicly his ties to surrealism;44 later, he began work on war paintings. Not surprisingly, Fukuzawa’s attitude toward his war paintings was deeply ambivalent; one pupil “recalls that Fukuzawa kept his war paintings down in the cellar in order to avoid looking at them.”45 After the war Fukuzawa helped found a left-wing artists’ group, Nihon Bijutsukai (Japan Artists’ Association), that in 1947 accused the nonsurrealist artist Fujita Tsuguharu of war crimes for his war paintings. As a result Fujita left Japan in 1949 and lived the rest of his life in exile.46 The Fujita incident, when juxtaposed with Fukuzawa’s own persecution by the government before the war and contribution to war paintings during it, helps to indicate the painful reasons why the intersections between surrealism and World War II have remained in the shadows of postwar Japan for so long: surrealism’s relation to the war has never been settled. In the context of postwar Japan, surrealism will always be haunted by World War II.

In this light Murakami and Japanese Neo Pop can be read as mobilizing surrealism to capitalize (however unconsciously or incompletely) on this haunting, to restore evaded memories of World War II by looking toward an art movement already freighted with its own unresolved sense of war responsibility. Ring must be seen in the same light. Indeed, Suzuki’s source novel locates the origins of its deadly curse in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Sadako’s mother, Shizuko, first manifests her own supernatural abilities in 1946, when she dives into the sea to recover the statue of a Buddhist ascetic and mystic dumped into the ocean by American occupation forces. According to a friend of Shizuko’s, it is only after this incident that Shizuko begins experiencing “searing pains in her head, accompanied by visions of things she’d never seen before flashing across her mind’s eye.”47 Shizuko’s visions predict the future, but it is her daughter Sadako’s images drawn from the past that lend these “visions of things” inherited from her mother the intensified potency of a lethal curse.48

Nakata and Takahashi omit this episode from their film, but Takahashi explains how World War II informed his personal sense of horror that he brought to his work on Ring: “Two things are especially important. One is an event that is similar to the Holocaust where Japanese soldiers in China, since called the ‘731 troops,’ performed scientific experiments on Chinese and Russian prisoners. That was very horrifying to learn about, even though it was not officially admitted. The second is the fact that Japan lost the war. But also the huge air raid on Tokyo and the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”49 Indeed, Takahashi’s previous collaboration with Nakata on the horror film Joyūrei (Ghost Actress, also known as Don’t Look Up, 1996) includes an important plot strand involving World War II that prefigures certain aspects of Ring. In Ghost Actress a film being shot in the present is set in the Japanese countryside during World War II. The shooting of this film within the film becomes haunted when old film footage from a cursed production is accidentally spliced in with the new footage, resulting in disorder and death on the set. Just as the curse in Ghost Actress transmits itself from old film to new film, so, too, does the curse in Ring travel from past to present via videotape and television. The haunted vortex between past and present contains World War II explicitly in Ghost Actress, while it remains implicit in Ring. Still, the atmosphere of dread created by a hidden, violent past hanging over a cursed present and delivered by media technology runs continuously between the two films. In fact, early on in Ring a coworker mentions to Asakawa the case of “a star who killed herself, and people saw her ghost on TV”—a case, in other words, that melds the curses of Ghost Actress and Ring.

The language for the past generated by Sadako’s images in Ring is both surrealist and cinematic. In fact, when Suzuki summarizes the series of discontinuous sounds and images included on the cursed videotape, he breaks them down into a kind of sequence analysis of a surrealist film, with twelve “scenes” of varying duration that can be labeled either “real” or “abstract.”50 In this sense Suzuki’s novel already gestures toward cinematic surrealism to describe its cursed images from the past. Nakata and Takahashi will complete the circle by bringing Sadako’s surrealist images to cinematic life. In many ways the images in this sequence are the heart of the film. Nakata explains:

I worked with my director of photography on making it hard to tell which direction the light was coming from in that sequence. I wanted the light to look flat, so distinctions between dark and light should be kind of vague. And of course we tweaked the quality of the images, because we shot on 35 mm and then worked again and again to lose the color digitally, and at the end we copied the images onto VHS a few times to degrade them. After we spent more than 24 hours on it, the images still had some color in them. So the producer Takashige Ichise came to me and said, “This is not good enough. We should do it again.” And I agreed. A lot of time, perhaps even 48 hours, was put into that sequence.51

Nakata first presents Sadako’s images as seven discontinuous scenes:

1. From below, we observe a man’s face peering down into a well as clouds pass by above him (fig. 3.4).

2. A woman brushes her hair in an oval mirror; an identical mirror appears and disappears quickly on the opposite side of the frame, offering us a glimpse of a white-robed figure with long black hair (Sadako); the original mirror returns, with the woman turning to the right as if to look for the now absent Sadako.

3. An assortment of written Japanese characters swim around a page, sometimes jostling each other and spelling out eruption.

4. A group of people stumble and crawl along the ground, some moving forward and others backward.

5. A hooded figure points to the left, the sea behind him (fig. 3.3).

6. An extreme close-up of an eye with the written character sada (“chaste”) appearing in its pupil; the eye blinks twice (fig. 3.5).

7. An exterior shot of a well in a forest (fig. 3.6).

A number of striking parallels unite Sadako’s images with those of the most famous surrealist film, Buñuel and Dalí’s Un chien andalou. The notorious opening sequence of Un chien andalou (described more fully in chapter 2), where a woman’s eye is slit by a razor after a man witnesses a passing cloud “slicing” the moon, echoes throughout this sequence in Ring. Similarities include not just the shared visual elements of eyes and clouds but the associational connections between images based on graphic matching (rather than conventional narrative logic): Un chien andalou’s series of rhyming shapes and movements of the razor across the man’s thumb, the cloud across the moon, and the razor across the eye recur in Ring’s rhyming circular shapes of the well and the mirror (scenes 1 and 2) and the eye and the well (scenes 6 and 7). In addition the rhyme between the movements of the written Japanese characters as they “crawl” across the page (scene 3) and the people as they crawl along the ground (scene 4) recalls the ants crawling out of a wound in a hand featured in Un chien andalou (and a visual motif in Dalí’s paintings as well).

The resemblances between the two films are not entirely accidental. Takahashi names Buñuel alongside Fritz Lang as “the directors who I was influenced by the most,”52 and Nakata acknowledges that prior to filming Ring, “I actually watched Un chien andalou a few times, so there could have been some kind of influence there.” He adds, “We all knew that [the influence of surrealism] was inevitable. For example, there was that shot of a huge eye [in Ring]. … Of course, a filmgoer would say, ‘OK, here’s a Luis Buñuel sequence.’ But actually, Takahashi and I tried our best to avoid that kind of surrealistic feeling. But because you cannot rationalize each shot on the videotape in the beginning, what does each image mean? They’re very weird, impressionistic, and surrealistic images.”53

What Nakata refers to as the “inevitable” influence of surrealism on Ring, despite attempts to sidestep it, certainly informs similarities between the surrealist structure of Sadako’s images and those of Un chien andalou. But this is not enough to call Ring a surrealist film in the same way we call Un chien andalou a surrealist film. Ring is still essentially a narrative film and Un chien andalou a nonnarrative one, even if the increased emphasis on narrative explanation in Verbinski’s The Ring points toward some significant departures from Hollywood narrative conventions in Ring (and J-Horror in general). As Takahashi explains concerning his adaptation of Ring to the screen, “The huge difference between the novel and the film is that the novel is a detective story. To make the film less of a detective story, I made [Ryuji] a psychic so that he doesn’t need to be as much of a detective. Like Eisenstein, I don’t want to focus on explaining the narrative details. If I just followed the detective story, that would require a lot of narrative explanation.” In relation to Eisenstein, Takahashi adds, “One of the models for J-Horror is to shoot things that are both probable and supernatural. It’s not as interesting if the subject matter is only realistic or only fantastic. To combine the two in a way that has the most impact, it is very effective to use a disjunctive method, the way Eisenstein did.”54

Takahashi’s application of Eisenstein’s disjunctions might finally be closer to Buñuel than to Eisenstein himself, but still, it is hard to imagine Takahashi or Nakata speaking about Ring the way Buñuel spoke about his collaboration with Dalí. For Buñuel, as we will recall, Un chien andalou’s images are “as mysterious to the two collaborators as to the spectator” and “NOTHING … SYMBOLIZES ANYTHING.”55 By the end of Ring the overall mystery presented by Sadako’s images has been deciphered, and we know, for the most part, what each image symbolizes. Even before Sadako’s images have been investigated, dissected, and translated into narrative meaning, the “blinking” mirrors of scene 2 (as they appear and disappear) and the blinking eye of scene 6 provide a visual bridge between the sequence’s first two scenes and last two scenes in such a manner (forming a “ring” around the sequence as a whole) that a prevailing sense of order emerges. This is not to say that Un chien andalou is pure disorder—indeed, it is quite typical of surrealism in that it depends on references to a number of recognizable narrative conventions and genres, even if it ultimately parodies, critiques, or subverts them—but its investment in “answers” is far less pronounced than Ring’s, as my analysis in chapter 2 demonstrates.

The surrealist aspects of Ring, however, are not limited to the “film-within-a-film” constituted by Sadako’s images. Sadako’s ghost, which becomes more and more corporeal as the film unfolds, moves in twisted, erratic spasms that unmistakably evoke the grotesque body movements made famous by ankoku butoh (dance of utter darkness), an avant-garde Japanese dance form originating with Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo. Indeed, Nakata cast an actress trained in this dance form to play Sadako. Ankoku butoh, often shortened to simply butoh, was first performed in 1959 and remains influential to this day.56 But Hijikata’s most active period was during the 1960s, when his surrealist-associated inspirations included Antonin Artaud and Takiguchi Shūzō, and butoh “tried to distort, warp, and torture the body in order to keep the self in a constant state of fragmentation.”57 At the climax of Ring, when Sadako emerges from the well and crawls through the television screen, her unnerving movements recall those of butoh performance, and her appearance bears an uncanny resemblance to Hijikata himself in the 1960s.58

Sadako’s body, through the aid of subtle visual effects (Nakata filmed backward movement by the actress and then presented it as forward motion), simulates the painful, often spastic gestures of butoh, where themes of bodily metamorphosis depend on shocking embodiments of violence, deformity, and disease. As Sadako metamorphoses from the mediated to the corporeal, from a ghost in the past to a body in the present, she gives shape to the twin legacies of surrealism and globalization I have argued for as profoundly intertwined in Ring’s expression of the mediated unconscious. To understand Sadako’s monstrosity, one must ultimately reckon with her as a media virus—a virus neither wholly Japanese nor wholly American but shared between Nakata’s Ring and Verbinski’s The Ring in such a way that surrealist vocabularies of assaultive and assaulted vision enable us to see a superflat global village mediated by the horrors of history. To see Sadako more fully in this light, we must observe what becomes of her in Hollywood.

THE RING BETWEEN JAPAN AND AMERICA

Of course, the very existence of Gore Verbinski’s The Ring, the American remake of Nakata’s Ring, extends the intertextual and transnational network of mediated globalization established by Nakata’s film.59 But the fact that Verbinski and his screenwriter, Ehren Kruger, choose to follow Nakata and Takahashi so closely in many important respects gives the remake an enhanced sense of mediated uncanniness, as if it were the ghost of a ghost created by globalization. For example, even before the film begins, the production company logo of DreamWorks Pictures flickers with the televisual static effect familiar from Nakata’s film, minus the logo’s traditional color scheme and theme music. The result is that the DreamWorks logo, with its iconic American connotations attached to production partner Steven Spielberg, shows signs that it has become possessed by a Japanese media infection—which, of course, it has. The Ring reveals America imitating Japan, in effect turning the tables on the conventional, defensive stereotype that Japan’s technological success depends on copying America’s innovations, not originating its own. But then again, in the uneven logic of globalized economics, DreamWorks can afford to risk a playful acknowledgment of this debt to Japan; it is they who bought American distribution rights to Nakata’s film on DVD, even bestowing the artificially “Japanized” title Ringu on Nakata’s film, so that for most American audiences it is the DreamWorks logo that precedes both versions of Ring. In this manner DreamWorks stakes a claim to “owning” the franchise in both its Japanese and American variations. This is a claim bolstered by the absence of Nakata and Takahashi’s names from the credits of The Ring, as well as by the decision to employ Nakata as the director of The Ring Two (2005), a Hollywood sequel to Verbinski’s remake again produced by DreamWorks.

But determining “ownership” of the Ring phenomenon becomes a slippery business when one moves from economic to cultural and historical concerns. We have already seen how Ring reached out to at least as many American film traditions as Japanese ones and how the transnational influences of globalization and surrealism shaped the film. Turning to The Ring necessitates consideration once again of globalization’s mediated unconscious, but from a different vantage point. In Ring the mediated unconscious could be detected in images that resonate with Japan’s experiences of World War II and the recessionary 1990s refracted through surrealism. In The Ring this template transforms so that the mediated unconscious breaks through in images linked to America’s experiences with the atomic bombing of Japan during World War II.60 Once again, I am not claiming that The Ring is consciously designed as an atomic allegory for World War II. I am arguing that the technologized global flows that brought this American remake of a Japanese horror film into existence had to incorporate and update, by unconscious necessity, precisely those histories, aesthetics, and politics I discussed in relation to Ring’s exploration of the mediated unconscious. So perhaps it is not surprising to learn that between Ring and The Ring, between Japan and America, we can also find surrealism—a context I will return to later in the chapter.

In a brilliant study of postwar Japanese visual culture, Akira Mizuta Lippit traces how “the atomic radiation that ended the war in Japan unleashed an excess visuality that threatened the material and conceptual dimensions of human interiority and exteriority.” Lippit is not the only one to suggest that “since 1945, the destruction of visual order by the atomic light and force has haunted Japanese visual culture,” but his original syntheses of technologies as diverse as X-rays and atomic radiation with films as varied as Teshigahara Hiroshi’s Suna no onna (Woman in the Dunes, 1964) and Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Cure (1997) lends their intersections a new level of complexity.61 Lippit’s notion of “excess visuality” and its disruption of borders between the visible and the invisible, like my own sense of the mediated unconscious, provides tools for investigating how cinema captures and expresses the impact of different technologies by means of its optical surfaces rather than only its explicit narratives or implicit themes. In my analysis that follows, I will investigate manifestations of excess visuality in The Ring as a bridge to the film’s interface with the mediated unconscious. As we will see, it is not only Japanese visual culture that has been haunted by the atomic bomb.62 That said, any attempt to neatly disentangle purely Japanese from purely American cinematic engagements with the atomic bomb is as futile as explaining the destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in exclusively Japanese or exclusively American terms.63 Even a cursory glance at the history of the most popular and durable cinematic icon of the atomic bombings, Gojira/Godzilla, discloses a powerful shared legacy between (and beyond) the two nations.64 But the case of Ring and The Ring presents this exchange with a new set of coordinates, where the forces of globalization and surrealism chart the shared histories of World War II in novel ways.

The Ring is set in America’s Pacific Northwest, where the newspaper reporter Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts) struggles to penetrate the mystery of the videotaped curse of Samara (Daveigh Chase) after her niece falls victim to it. Keller’s investigation takes her from Seattle to two remote areas of Washington State, Shelter Mountain and Moesko Island. Each new revelation about the curse’s origins comes at the expense of time ticking away for Rachel herself; her psychic son, Aidan (David Dorfman); and her ex, Noah (Martin Henderson), all of whom have only seven days left to live after watching Samara’s videotape. When Rachel learns that Samara was the child of Anna Morgan (Shannon Cochran) and Richard Morgan (Brian Cox), a couple whose happiness as successful horse breeders was offset by their inability to conceive, she hopes that uncovering this family’s secret history can counteract the curse. But in the end she discovers that Samara’s death sentence can only be avoided by copying her videotape and showing it to a new victim. This knowledge comes in time to save herself and Aidan but not Noah.

When Rachel plays Samara’s videotape for the first time, something extraordinary happens at the level of visuality in The Ring. In a film almost completely devoid of bright sunshine, a blazing sunset suddenly washes over the cabin where Rachel prepares to play the tape, drenching the location in such intensely bright light that the red leaves on a nearby tree seem to burn under the illumination (fig. 3.7). The light pierces the cabin’s interior, bathing the scene of Rachel’s viewing in a fiery crimson glow. When the videotape ends, the sun has set and the overcast sky returns. Only now, it is raining.

In this sequence, like several others in The Ring, the ghosts haunting the film are not limited to Samara or Sadako but extend to those technological and historical substrates that conjoin Ring and The Ring. Here, through the circulation of visuality I have described as globalization’s mediated unconscious, the scorching light that momentarily consumes the cabin evokes an atomic blast. In these images the atomic bomb meets the TV and the VCR as technological agents of globalization, just as Japan in 1945 meets present-day America as intertwined historical moments. This connotation may not have been intended by Verbinski, but it is there nonetheless, in the images themselves and in the contexts that ground them. It is revealing that the tree selected to “burn” in this sequence is a red Japanese maple, an image that gains significance later as a tree on fire glimpsed on Samara’s videotape, and then as an etching literally burned into a wall through Samara’s psychic power. The tree’s identity as a red Japanese maple is never mentioned in the film itself, but new media’s contribution to global flows means that it is not only botanists who will eventually catch the reference.

THE RING ONLINE

On websites devoted to the Ring phenomenon in all its forms, production details such as the red Japanese maple are eagerly communicated and discussed by fans and filmmakers alike. I am not suggesting that such websites articulate the same kinds of theoretical and historical claims I am making here, but their in-depth devotion to issues concerning each film’s production, the narrative significance of particular images, and comparisons between the Japanese and American versions of the Ring phenomenon certainly provide an impressive set of tools that certain viewers might use to interpret the films along similar lines. These tools come in a variety of forms, such as articles, reviews, interviews, and online discussions involving viewers all over the world. The sheer diversity of these forms and the mountain of information they present is often difficult to organize in the manner of a streamlined argument, but the information itself is remarkably detailed and easily navigated. For example, in an article on the production of The Ring included on the website Curse of the Ring, we learn that

the primary exception to the film’s subdued color scheme was a fiery red Japanese maple seen in the cursed video and acting almost as a signpost along the way. “The tree is a focal point of the movie. It kind of unifies the different elements—everything always seems to come back to that tree,” offers [production designer Tom] Duffield.… The red maple was also one of the designer’s homages to the story’s Japanese origins. Others that might be picked out include an American version of a sliding luminous door, and a Japanese wall hanging seen at the Morgan ranch.65

Granted, there are a number of analytic steps separating the presentation of this information from a reckoning with the mediated unconscious. But the fact remains that this article, as part of a website produced by, geared toward, and accessible to everyday (albeit English-speaking and Internet-savvy) viewers the world over, raises concerns like the visual significance of the red Japanese maple, its status as a “focal point” of the film, and its presence as one of a series of images that connect the film’s Japanese and American dimensions. How exactly viewers might use such information is difficult to determine, but one possibility is that they could return to The Ring with new eyes.66 How might knowledge about the red Japanese maple guide viewers toward the atomic connotations of the film’s related imagery of burning and scarring? Could the website help viewers establish a sort of connective tissue between images like the red Japanese maple aflame, Rachel’s arm scarred from the burning touch of Samara’s ghost, and the rain that falls so often in the film (recalling the black rain of atomic fallout, a connotation heightened when the rain pours down following the “atomic” sunset)? Or might viewers abandon such readings after the website classifies the burning tree as an “abstract” image, distinct from the “concrete” images on the videotape that can be explained as tangible emblems belonging to the film’s story arc?67 In either case, the website can only be regarded as one element among many others that might factor in matters of spectatorship—it cannot stand alone in relation to these questions.

Still, the very existence of Curse of the Ring and the ambitious range of its engagements with the entire Ring phenomenon is rather exceptional, since ultimately very few films inspire this kind of detailed online analysis. Then there is the plot of The Ring, which is about the very kind of technological deconstruction of an analog medium that viewers are invited to perform themselves through the website. Rachel uses techniques that we associate with the digital era (searching the Internet, freezing and printing images, taking digital photographs) to decipher the videotape’s images, while the website is built around the desire of viewers to participate in a similar sort of process—using new media to decipher the film’s images. This unusual sort of mirroring between the film and the website thrusts the website forward when considering issues of spectatorship, so even if the website refrains from engaging the history of World War II explicitly, its treatment of history merits further exploration.

One section of Curse of the Ring covers the topic of the “factual basis of The Ring.”68 Here, users of the website can read an illustrated article on Fukurai Tomokichi, a Japanese psychology professor who published a book in 1913 that was later expanded and translated into English as Clairvoyance and Thoughtography (1931). In this book Fukurai reports on his experiments with a number of mediums between 1910 and 1928, leading him to conclude “that clairvoyance is a fact, and that thoughtography [the ability to imprint thoughts on a photographic surface through psychic means] is also a fact.”69 Fukurai’s evidence of clairvoyance comes from mediums who can “read” letters on hidden sheets of paper controlled by the professor, while his claims for thoughtography rest with mediums who can imprint their “thoughts” directly on photographic plates, without the aid of a camera. The website does not pass any judgment on the scientific worth of these experiments, but it does point out that two of Fukurai’s subjects are named Shizuko and Sadako. Like the character of Sadako’s mother in Suzuki’s novel and Nakata’s film who bears the same first name, Fukurai’s Shizuko commits suicide after she is accused of fraud for her demonstrations of clairvoyance. What the website does not mention is that Fukurai’s Sadako also bears some striking resemblances to her fictional counterpart, although she is in no way related to Shizuko. According to Fukurai, Sadako manifests multiple personalities, including one who calls himself a “long-nosed goblin.”70 In novel and film one of the messages embedded on Sadako’s videotape is “frolic in brine, goblins be thine,” a reference to the centrality of water to her origins. Fukurai’s Sadako also exhibits some talent in thoughtography, which of course takes on much greater proportions in the film through the cursed videotape. The Ring dispenses with any substantial account of Samara’s mother as clairvoyant, but it extends significantly Samara’s abilities in thoughtography. Again, the website’s inclusion of Fukurai offers information that could aid viewers in anchoring the film’s representation of thoughtography to history, even if it is not directly tied to the history of World War II (in fact, the website’s section on the factual basis for En no Ozunu, the Buddhist ascetic whose statue ignites Shizuko’s psychic powers in Suzuki’s novel, fails to mention the context of the American occupation that I described earlier in this chapter).71 But there are other, indirect routes to this history that the website evokes implicitly. Through a link to a related website, Curse of the Ring offers galleries of Samara’s videotape and prevideotape instances of thoughtography, all of which appear briefly in The Ring. What one already senses while watching the film is only strengthened by perusing these images online: that behind thoughtography stands surrealism.

FROM THOUGHTOGRAPHY TO RAYOGRAPHY

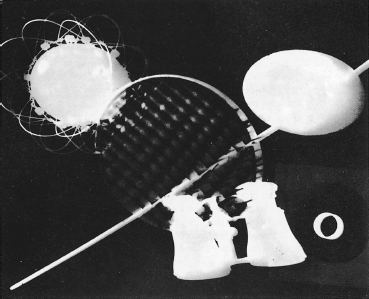

Curse of the Ring links to a website called Inteferon’s Viral Vestibule, which describes itself as “a gift to the fans of Sadamara. It does not pretend to be a comprehensive Ring site—instead the emphasis is on analysis aids such as movie graphics and technical info.”72 The use of the term “Sadamara” to refer to both Sadako and Samara reinforces the organizational premise of Curse of the Ring: that Ring and The Ring are so deeply intertwined that analysis of one necessitates consultation of the other. Among the “analysis aids” offered by Inteferon’s Viral Vestibule is an image gallery entitled “X-ray images,” which collects the examples of thoughtography created by Samara in The Ring prior to the cursed videotape. In the film these images are glimpsed briefly when Noah reads through the medical records of Anna Morgan and Samara at the psychiatric hospital where Samara once stayed. On the website the images can be studied as a series of thumbnails side by side, each of which can be magnified by clicking on it. Even though each image comes with a makeshift title coined by the website that ostensibly describes the objects one sees in them (“rocking horse waves,” “needles doll mask”), the titles do not fully capture the strangeness of the images, nor does the classification of “X-ray” really suit them.73 A better term would be rayograph.

Rayographs were the name the artist and photographer Man Ray, a close associate of the Surrealist Group, gave to images he created through a process he described as “cameraless” photography.74 Rayographs were constructed by placing objects directly on photosensitive paper, exposing the paper and the objects to the light for a few seconds, and then completing developing as one would with conventional photographs. The results were images simultaneously concrete and dreamlike, where the outlines of recognizable objects gave way to slightly distorted, stark white silhouettes that contrasted sharply against a black background. They were photographic but not photorealistic. In short, they were surrealistic.

Although Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky) made his first rayographs in late 1921 or early 1922, their significance came both earlier and later. By 1921 the American Man Ray had moved to Paris and become deeply involved with the Dadaists there. According to Man Ray, the first person to observe his rayographs was the leading Dadaist Tristan Tzara, who was very enthusiastic and told him that the rayographs were “far superior to similar attempts … made a few years ago by Christian Schad, an early Dadaist.”75 The fact that Man Ray discovered rayography when and how he did, alongside Dada and well before André Breton brought surrealism into official existence in 1924, has led a number of art historians to distance Man Ray from surrealism.76 I disagree with this view and would argue instead, as Rosalind Krauss has done, that Man Ray’s work not only constitutes some of surrealist photography’s most important achievements but that photography itself has for too long remained “the great unknown, undervalued aspect of surrealist practice” instead of being recognized as “the great production of the movement.”77 I would amend Krauss only by adding that cinema has received even less attention than photography in most studies of surrealism and that it is cinema, in conjunction with photography, that deserves a place at the heart of surrealism’s accomplishments.

It is difficult, however, to claim that Man Ray’s own films are the equal of his photography when it comes to surrealist power. Man Ray himself admits that making films never excited him the way his photographs and other artwork did, that he “had no desire to become a successful director.”78 In fact, Man Ray’s preference for photography over cinema prefigures strikingly the stance of Roland Barthes that I described in chapter 1: “A book, a painting, a sculpture, a drawing, a photograph, and any concrete object are always at one’s disposition, to be appreciated or ignored, whereas a spectacle before an assemblage insists on the general attention, limited to its period of presentation.… I prefer the permanent immobility of a static work which allows me to make my deductions at my leisure, without being distracted by attending circumstances.”79

For Man Ray, as for Barthes, this preference did not translate into an aversion to watching films or to mining the surrealist territory between photography and cinema. Since Man Ray welcomed technological innovations in film, from sound to color to 3-D, and “even hoped for the addition of the sensations of warmth, cold, taste, and smell,” one can imagine him embracing the capabilities of a website to provide a “photographic” experience of “cinema.”80 But he never could have imagined how The Ring, with the aid of the Internet, would refigure rayography as thoughtography.

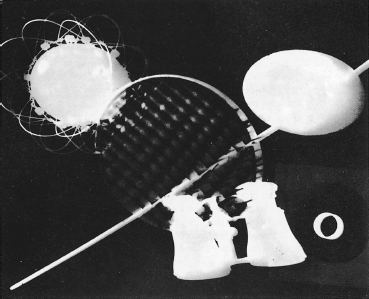

Verbinski has said that one of the qualities that drew him to The Ring was its mixture of high-culture and low-culture characteristics: “It’s a simple premise but not exactly a ‘studio picture.’ I think that is what interested DreamWorks as well. It’s both pulp and avant-garde.”81 This awareness of the film’s intersections with the avant-garde may not have extended to deliberately orchestrated citations of surrealism, but there is no doubt that when The Ring wades into avant-garde terrain, the specter of surrealism almost always materializes in some shape or form. Samara’s thoughtography is a prime example. When Noah flips through Samara’s medical records, he discovers a file containing several sheets of film that he holds up to the light to study (they also reappear later on an old videotape where Samara is interviewed by a doctor at the hospital who conducts thoughtography experiments with her). What we see on these sheets of film—distorted white silhouettes of objects staged against black backgrounds—often looks remarkably similar to rayographs. Indeed, the gallery of Samara’s thoughtography displayed in Inteferon’s Viral Vestibule includes one image, dubbed “Comb Tree Woman,” that closely resembles one of Man Ray’s first published rayographs, an untitled image that also prominently features a comb (figs. 3.8, 3.9).82 “Comb Tree Woman” is not one of the four thoughtographs Noah inspects in The Ring, but it is one of several additional thoughtographs included in a compilation of deleted footage available on the DVD of The Ring. Another one of these deleted thoughtographs, “Hairbrush,” bears a strong similarity to one of Man Ray’s most famous images, the sculpture entitled Cadeau (Gift, 1921), which takes the shape of an iron outfitted with a row of upturned nails for “teeth.”83 Like Gift, “Hairbrush” confronts its audience by transforming a mundane household object, emphasizing the rows of bristles as “teeth” facing directly, menacingly outward.

Figure 3.9 Man Ray, untitled rayograph: comb, straight razor blade, needle and other forms (1922). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Gelatin silver print. 22.4 × 17.5 cm (813/16 × 67/8 in.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.294). Copy Photograph © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image copyright © Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image Source: Art Resource, New York. © 2013 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

The new media platforms connected to The Ring, whether the DVD or the website, highlight particular affinities with Man Ray’s work, but the thoughtography featured in the film itself still evokes enough visual aspects of rayography for surrealism to hang heavily in the air surrounding Samara. The fact that The Ring refers to Samara’s images not as thoughtography but as “projected thermography” pushes these images toward a conjuncture between surrealism’s rayography and World War II’s atomic radiation. Thermography, a method for measuring heat emissions from the body by capturing them photographically, is a term that unites the film’s images of thoughtography with those reminiscent of the atomic bombings. As I mentioned earlier, Samara’s ghost burns Rachel’s arm, and Samara herself burns an etching of the red Japanese maple into the wood of the Morgan family barn, where she lives temporarily. Anna and Samara’s first psychologist, Dr. Grasnik (Jane Alexander), speaks to Rachel about how “Anna said she’d been seeing things, horrible things, like they’d been burned inside her. That it only happened around Samara, that the girl put them there.” And when Rachel returns to the cabin at Shelter Mountain near the end of the film as the curse threatens to overtake her, she reminds Noah that seven days earlier, “the sun came through the leaves and lit them up like it was on fire. Right at sunset. Right when I watched the tape.”

One of Samara’s thoughtographs, or projected thermographs, shows this tree, the red Japanese maple, in silhouette. Her cursed videotape shows it again; only this time it is on fire. The film suggests that this tree’s significance pertains to its status as one of the last things Samara sees before a desperate Anna chokes her and pushes her into a well at Shelter Mountain. This is the same well on top of which the cabin in which Rachel first watches the tape was constructed—this is where Samara died. It is the film’s “ground zero,” a label whose atomic connotations are underlined visually when a spilled set of marbles collect as if drawn by magnetism, or radiation, to the very spot in the cabin beneath which the well is buried. In this manner the visual images of the burning red Japanese maple move beyond their strictly “narrative” function and into the realm of history, mapped by the mediated unconscious.

On the occasion of a 1963 retrospective exhibition, Man Ray described his rayographs in this way: “Like the undisturbed ashes of an object consumed by flames, these images are oxidized residues fixed by light and chemical elements of an experience.”84 Man Ray’s description seems haunted by the atomic bomb, even if the rayographs he refers to were created prior to 1945. The image of atomic shadows, those horrifying burns left behind on pavement and buildings when human bodies were incinerated by the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, seem apparent in his words, even if they are only implied unintentionally. It is also important to note that Man Ray continued making rayographs later in his career. The only rayograph included as an illustration in his 1963 autobiography, Self Portrait, was one he created in 1946. Among the objects used in this particular rayograph is a wire basket whose silhouette is uncannily reminiscent of Niels Bohr’s popular “planetary model” of the atom, with a dense central nucleus composed of protons and neutrons surrounded by rings of circling electrons (fig. 3.10).85 A deliberate atomic reference? Probably not, especially if we take Man Ray at his word when he insists that objects were selected for his rayographs, at least initially, by “taking whatever objects came to hand.”86 Nor is there any attempt in Man Ray’s rayographs to tell a story the way there is in Samara’s though-tographs, where most objects are meant to be “translated” as symbols of Samara’s own experiences. But the overlapping of rayography and thoughtography made possible by The Ring in its globalized, mediated dimensions gives Man Ray’s images, like Verbinski’s, a visuality that precedes and exceeds them.

Man Ray’s account of creating rayographs by randomly choosing objects close at hand is a variation on Breton’s surrealist practice of automatic writing. Indeed, Breton’s landmark accomplishment in automatic writing, the book Les champs magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields) he coauthored with Philippe Soupault in 1920, was later designated by Breton (in retrospect) as the first surrealist text. It is this book that Man Ray nods to in the title of his first published collection of rayography, Delicious Fields (1922). This is not the first or last time Man Ray and Breton would inspire each other. In Surrealism and Painting (1928), an influential book expanded in later editions but originally composed largely of earlier writings published in the journal La révolution surréaliste, Breton praises Man Ray for how he has “applied himself vigorously to the task of stripping [photography] of its positive nature, of forcing it to abandon its arrogant air and pretentious claims.” Breton continues: “The photographic print, considered in isolation, is certainly permeated with an emotive value that makes it a supremely precious article of exchange (and when will all the books that are worth anything stop being illustrated with drawings and appear only with photographs?); nevertheless, despite the fact that it is endowed with a special power of suggestion, it is not in the final analysis the faithful image that we aim to retain of something that will soon be gone forever.”87

What Breton sees as the promise of photography, in the context of Man Ray’s work, is the surrealist potential of the photographic image later articulated in strikingly similar terms by André Bazin, as I discussed in chapter r. the surrealist photograph’s power stems from but also reaches beyond its “faithful” reproduction of the world. Breton would put into practice his preference for photographs over drawings in his own books Nadja (1928) and L’amour fou (1937). In the first case he employed Man Ray’s assistant, Jacques-André Boiffard, and in the second Brassaï and Man Ray himself. But as Breton’s comments in Surrealism and Painting suggest, he is both impressed by and wary of photography.88 As befits a champion of automatism in surrealist artistic production, he is drawn to photography’s “emotive value” and “special power of suggestion” but distrustful of photography’s “arrogant air and pretentious claims” that seem inherent in its “positive nature”—its assumption that it can somehow authentically reproduce the world it records. This ambivalence toward photography does not prevent Breton from stating, in an earlier article, that automatic writing is “nothing less than thought photography.”89 Breton’s formulation of automatic writing as thought photography, when considered alongside the intersections between thoughtography, rayography, and thermography presented in The Ring, brings us nearly full circle. We can now return to where we began, with the place of The Ring in a superflat global village.

COMPLETING THE RING

Samara’s thoughtographs literalize Breton’s sense of automatic writing as a form of thought photography. In a videotaped interview a psychologist asks Samara how she made the thoughtographs. She replies, “I don’t make them. I see them. Then they just are.” For Breton automatism is “one of surrealism’s two great directions.… Any form of expression in which automatism does not at least advance under cover runs a grave risk of moving out of the surrealist orbit.” The second “great direction” of surrealism Breton mentions beside automatism turns out to be not so great after all: “The other road available to surrealism to reach its objective … trompe l’oeil … has been proved by experience to be far less reliable and even presents very real risks of the traveler losing his way altogether.”90 Breton’s elevation of automatism above trompe l’oeil replays his double-edged characterization of photography in Surrealism and Painting as valuable in its “special power of suggestion” (photography’s good automatism) but suspicious in its “positive nature” (photography’s bad automatism). A similar distinction will be voiced by Bazin in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” when he differentiates between a “true realism” that uncovers reality’s hidden essence and the “pseudorealism” of trompe l’oeil illusionism that merely imitates reality’s surface appearances. For Bazin, as I explained in chapter 1, surrealist photography holds a privileged place in his argument because of its ability to wed “true realism” and “pseudorealism,” to produce “an hallucination that is also a fact.” Bazin does not mention Man Ray by name, but it is likely he has Man Ray in mind when he notes how the surrealists “looked to the photographic plate to provide them with their monstrosities.”91

Bazin’s use of the term monstrosities is worth pausing over. By turning to surrealist photography, he suggests that there is something monstrous in the photographic image inseparable from its revelatory potential, its ability to present “the objective world…in all its virginal purity to my attention and consequently to my love.”92 Surrealist photography’s factual hallucination is both revelatory and monstrous. It enables us to see in a new way, but that new vision passes through the monstrous, as well as the redemptive. What would Bazin have made of those peculiar photographs at the heart of both Ring and The Ring, the ones that show people who have been exposed to the cursed videotape as deformed and distorted? (fig. 3.11). These are photographs that “know” something the people pictured inside them do not: that something about them has changed since watching the videotape, something invisible to the naked eye but visible in a photograph. And this “something” is both revelatory and monstrous. It is a surreality.