Cultural Issues in Pediatric Care

Lee M. Pachter

Pediatricians live and work in a multicultural world. Among the world's 7 billion people residing in over 200 countries, more than 6,000 languages are spoken. As the global population becomes more mobile, population diversity increases in all countries. In the United States, sources of ethnic and cultural diversity come from indigenous cultural groups such as Native Americans and Alaskan and Hawaiian natives, groups from U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico, recent immigrant groups, those whose heritage originates from the African diaspora, as well as others whose families and communities migrated to the United States from Europe and Asia generations ago but who have retained cultural identification. U.S. census estimates suggest that in 2016, almost 40% of the U.S. population self-identified as belonging to a racial/ethnic group other than non-Hispanic white. Recent immigrants comprise 13.5% of the U.S. population, but if U.S.-born children of these immigrants are included, 27% of the population are either new immigrants or first-generation Americans. Immigrants from China and India account for the largest groups coming to the United States, followed by those from Mexico. This national and international diversity allows for a heterogeneity of experience that enriches the lives of everyone. Much of this diversity is based on varied cultural orientation.

What Is Culture?

The concept of culture does not refer exclusively to racial and ethnic categorizations. A common definition of cultural group is a collective that shares common heritage, worldviews, beliefs, values, attitudes, behaviors, practices, and identity . Cultural groups can be based on identities such as gender orientation (gay/lesbian, bisexual, transgender), age (teen culture), being deaf or hearing impaired (deaf culture), and having neurodevelopmental differences (neurodiversity; neurotypical and neuroatypical). All these groups to a certain extent share common worldviews, attitudes, beliefs, values, practices, and identities.

Medical professionals can also be considered as belonging to a specific cultural group. Those who identify with the culture of medicine share common theories of well-being and disease, acceptance of the biomedical and biopsychosocial models of health, and common practices and rituals. As with other cultural groups, physicians and other healthcare professionals have a distinct language and share a common history, the same preparatory courses that must be mastered for entrance into training for the profession (a rite of passage). Medical professionals subscribe to common norms in medical practice. Young physicians learn a new way to describe health and illness that requires a new common vocabulary and an accepted structure for communicating a patient's history. These common beliefs, orientations, and practices are often not shared by those outside medicine. Therefore, any clinical interaction between a healthcare provider and a patient can be a potential cross-cultural interaction —between the culture of medicine and the culture of the patient—regardless of the race or ethnicity of the participants. A culturally informed and sensitized approach to clinical communication is a fundamental skill required of all medical professionals, regardless of the demographic makeup of one's patient population.

Culture and Identity

We are all members of multiple cultural groups. Our identification or affiliation with different groups is not fixed or unchangeable. With whom we self-identify may depend on specific situations and contexts and may change over time. A gay Latino physician may feel, at different times and in different situations, greatest affinity as a member of Latino culture, a member of the culture of medicine, a minority in the United States, or a gay man. An immigrant from India may initially feel great connection with her Indian culture and heritage, which may wane during periods of assimilation into American cultural life, then increase again in later life. Culturally informed clinicians should never assume that they know or understand the cultural identity of a person based solely on perception of ethnic, racial, or other group affiliation.

Intracultural Variability

There can be significantly different beliefs, values, and behaviors among members of the same cultural group. Often, there is as much variability within cultures as there is between cultures. The sources of this variability include differences in personal psychology and philosophy, family beliefs and practices, social context, and other demographic differences, as well as acculturation , defined as the changes in beliefs and practices resulting from continuous interactions with another culture. The literature on acculturation and health outcomes shows varied effects of cultural change on health and well-being. These differences are in part caused by overly simplistic ways of measuring acculturation in public health and health services research. The use of proxies, such as generational status (recent immigration, first generation) and socioeconomic status, as measures of acculturation does not allow for an understanding of the complex behavioral changes that occur during shifts in cultural orientation. Often, acculturation is seen as a linear process where individuals move from unacculturated to acculturated or assimilated into the host culture. This simplistic view does not take into account the reality that acculturation is bidimensional : the degree to which an individual continues to identify with her original cultural identity, and the degree to which the host cultural orientation is adopted. These are separate and independent processes. One can become bicultural (adopting the host culture while retaining aspects of the original culture), assimilated (host culture is adopted, but original culture is not retained), separated (original cultural orientation is retained, but host culture is not greatly adopted), or marginalized (does not adopt host culture and does not retain original culture). These variations in the acculturation process are determined not only by the individual going through the cultural change process but also by the degree of acceptance of diversity in the host culture. In theory, individuals who best adapt to the multicultural society are those who are bicultural , since they retain the strengths and assets of their heritage culture while being able to positively adjust to host cultural norms. Likewise, members of the majority culture who are able to take a bicultural perspective will have relative advantage in the multicultural society. This type of perspective is a foundation of cultural awareness and culturally informed practice.

Culturally Informed Care

Physicians and patients bring to their interactions diverse orientations from multiple cultural systems. These different belief systems and practices could have significant implications for the delivery of healthcare (Table 11.1 ). Consequently, physician cultural awareness, sensitivity, and humility is critical to successful patient–provider interaction.

Table 11.1

The culturally informed physician (1) attempts to understand and respect the beliefs, values, attitudes, and lifestyles of patients; (2) understands that health and illness are influenced by ethnic and cultural orientation, religious and spiritual beliefs, and linguistic considerations; (3) has insight into own cultural biases and does not see cultural issues as something that only affects the patient; (4) is sensitive to how differences in power and privilege may affect the quality of the clinical encounter; (5) recognizes that in addition to the physiologic aspects of disease, the culturally and psychologically constructed meaning of illness and health is a central clinical issue; and (6) is sensitive to intragroup variations in beliefs and practices and avoids stereotyping based on any group affiliation. These core components of culturally-informed care are important for interactions with all patients, regardless of race or ethnicity. Culturally sensitive clinical care is essentially generally sensitive clinical care.

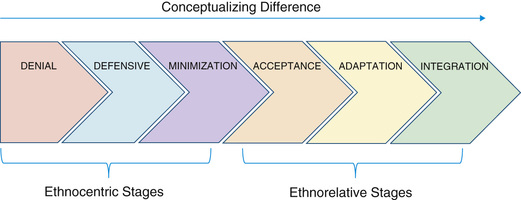

Becoming culturally informed is a developmental process. Fig. 11.1 displays a framework that includes a continuum of perceptions and orientations to cultural awareness. Individuals in the denial stage perceive their own cultural orientation as the true one, with other cultures either undifferentiated or unnoticed. In the defensive stage, other cultures are acknowledged but regarded as inferior to one's own culture. The minimization stage is characterized by beliefs that fundamental similarities among people outweigh any differences, and downplays the role of culture as a source of human variation. The idea that one should be “color blind” is an example of a common belief of individuals in the minimization stage.

As one moves to the acceptance stage, cultural differences are acknowledged. Further expansion and understanding lead to adaptation , where one not only acknowledges differences but can shift frames of reference and have a level of comfort outside one's own cultural frame. This eventually leads to further comfort with different worldviews seen at the integration stage, where individuals respect cultural differences and can comfortably interact across cultures, even incorporating aspects of different cultural orientations into their own.

Understanding Culture in the Context of Healthcare

Cultural orientation is just one of many different perspectives that individuals draw on as they make health and healthcare decisions. Individual psychology, past experiences, religious and spiritual views, social position, socioeconomic status, and family norms all can contribute to a person's health beliefs and practices. These beliefs and practices can also change over time and may be expressed differently in different situations and circumstances. Because of the significant variability in health beliefs and behaviors seen among members of the same cultural group, an approach to cultural competency that emphasizes a knowledge set of specific cultural health practices in different cultural groups could lead to false assumptions and stereotyping. Knowledge is important, but it only goes so far. Instead, an approach that focuses on the healthcare provider acquiring skills and attitudes relating to open and effective communication styles is a preferable approach to culturally effective and informed care. Such an approach does not rely on rote knowledge of facts that may change depending on time, place, and individuals. Instead, it provides a skills toolbox that can be used in all circumstances. The following skills can lead to a culturally informed approach to care:

- 1. Don't assume. Presupposing that a particular patient may have certain beliefs, or may act in a particular way based on their cultural group affiliation, could lead to incorrect assumptions. Sources of intracultural diversity are varied.

- 2. Practice humility. Cultural humility has been described by Hook et al. (2013) as “the ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity.” Cultural humility goes beyond cultural competency in that it requires the clinician to self-reflect and acknowledge that one's own cultural orientation enters into any transaction with a patient (see Chapter 2.1 ).

Cultural humility aims to fix power imbalances between the dominant (hospital-medical) culture and the patient. It recognizes the value of the patient's culture and incorporates the patient's life experiences and understanding outside the scope of the provider; it creates a collaboration and a partnership.

Cultural competency is an approach that typically focuses on the patient's culture, whereas cultural humility acknowledges that both physicians and patients have cultural orientations, and that a successful relationship requires give and take among those differing perspectives. It also includes an understanding that differences in social power, which are inherent in the physician–patient relationship, need to be understood and addressed so that open communication can occur.

- 3. Understand privilege. Members of the majority culture have certain privileges and benefits that are often unrecognized and unacknowledged. For example, they can have high expectations that they will be positively represented in media such as movies and television. Compared with minority groups, those in the majority culture have less chance of being followed by security guards at stores, or having their bags checked. They have a greater chance of having a positive reception in a new neighborhood, or of finding food in the supermarket that is consistent with one's heritage. These privileges typically go unnoticed by members of the majority culture, but their absence is painfully recognized by members of nonmajority cultural groups. The culturally informed physician should try to be mindful of these privileges, and how they may influence the interaction between physicians and patients.

- 4.

Be inquisitive.

Because of the significant amount of intracultural diversity of beliefs and practices, the only way to know a particular patient's approach to issues concerning health and illness is through direct and effective communication. Asking about the patient's/family's perspective in an inquisitive and respectful manner will usually be met with open and honest responses, as long as the patient does not feel looked down on and the questions are asked in genuine interest. Obtaining a health beliefs history

is an effective way of understanding clinical issues from the patient's and family's perspective (Table 11.2

). The health beliefs history gathers information on the patient's views on the identification of health problems, causes, susceptibility, signs and symptoms, concerns, treatment, and expectations. Responses gathered from the health beliefs history can be helpful in guiding care plans and health education interventions.

- 5. Be flexible. As members of the culture of medicine, clinicians have been educated and acculturated to the biomedical model as the optimal approach to health and illness. Patients and families may have health beliefs and practices that do not fully fit the biomedical model. Traditional beliefs and practices may be used in tandem with biomedical approaches. An individual's approach to health rarely is exclusively biomedical or traditional, and often a combination of multiple approaches. The health beliefs history provides clinicians with information regarding the nonbiomedical beliefs and practices that may be held by the patient. Culturally informed physicians should be flexible and find ways of integrating nonharmful traditional beliefs and practices into the medical care plan to make that plan fit the patient's needs and worldview. This will likely result in better adherence to treatment and prevention.

Obtaining a health beliefs history for a child with asthma, for example, may reveal that the family uses an alternative remedy when the symptoms first occur. If the symptoms do not resolve after giving the remedy, the family administers standard medical care. In this case, if the alternative remedy is safe and has no significant likelihood of causing adverse effects, the culturally informed physician might say, “I'm not sure if the remedy you're using is helpful or not, but I can say that if used as directed, it's not likely to be harmful. So if you think it may work, feel free to try it. But instead of waiting to give the prescription medicine until after you see if the remedy works, why don't you give it at the same time you give the remedy? Maybe they’ll work well together.” This approach shows respect for the family-held beliefs and practices while increasing timely adherence to the biomedical therapy.

At times, an alternative therapy the patient is using may be contraindicated or may have adverse effects. In this case it is advisable to recommend against the therapy, but whenever possible, one should attempt to replace the therapy with another, safer, culturally acceptable treatment. If a parent is giving a child tea containing harmful ingredients to treat a cold, the culturally informed physician could recommend stopping the practice and explain the concerns, but then recommend replacing the harmful tea with something safer that fits the family's cultural belief system, such as a weak herbal tea with no harmful ingredients. This requires an awareness and background knowledge of the cultural belief system, but this approach increases the chances that the family will follow through on the recommendation and feel that their beliefs are respected.

Awareness-Assessment-Negotiation Model

Providing care in the multicultural context can be challenging, but it offers opportunities for creativity and can result in improved long-term physician–patient relationships, which will ultimately improve the quality and outcomes of healthcare. Culturally informed care combines knowledge with effective communication skills, an open attitude, and the qualities of flexibility and humility.

The culturally informed physician should first become aware of common health beliefs and practices of patients in the practice. Reading literature on the particular groups could increase awareness, but with the caution that such information may be outdated (cultural beliefs and practices change over time) and not specific to the local context. The best approach to becoming aware of specific health beliefs and practices is to ask—enter into conversations with patients, families, and community members. One might say, “I've heard that there are ways of treating this illness [or staying healthy] that people believe work, but doctors don't know about. Sometimes they're recommended by grandparents or others in your community. They may be effective. Have you heard of any of these?” This approach shows genuine interest and openness, is not based on presumptions, and does not ask about behaviors or practices, only if the patient has heard of these practices. If the question elicits a positive response, the conversation can then continue, including asking whether the patient has personally tried any of the therapies, under what circumstances, and if they thought it was helpful. This approach shows respect for the patient as an individual and avoids stereotyping all members of a particular group as having a uniform set of cultural beliefs and practices.

The information obtained should be seen only as common ways that members of a community may interpret health-related issues. Assuming that all members subscribe to similar beliefs and practices would be incorrect and potentially damaging by promoting stereotypes. Since the unit of measurement in clinical care is the individual patient and family, clinicians must assess to what extent a specific patient may act on these general beliefs and under what circumstances. The health beliefs history can help the physician become aware of the specific beliefs and practices that a patient holds, and allow one to tailor the care to the individual patient.

Once the patient's explanatory model is elicited and understood, the clinician should be able to assess the congruity of this model and the biomedical model, finding similarities. Then the process of negotiating can occur. Integrating patient-held approaches to health with evidence-based biomedical standards of care will help place care within the lifestyle and worldview of patients, leading to increased adherence to medical care plans, better physician–patient communication, enhanced long-term therapeutic relationship, and improved patient (and physician) satisfaction.

Culture-Specific Beliefs

Robert M. Kliegman

Cultural group-specific practices that affect health-seeking behaviors are noted in Tables 11.3 and 11.4 .

Table 11.3

Cultural Values* Relevant to Health and Health-Seeking Behavior

| CULTURAL GROUP | RELEVANT CULTURAL NORMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of Norm | Consequences of Failure to Appreciate | |

| Latino | Fatalismo: Fate is predetermined, reducing belief in the importance of screening and prevention. | Less preventive screening |

| Simpática: Politeness/kindness in the face of adversity—expectation that the physician should be polite and pleasant, not detached. | Nonadherence to therapy, failure to make follow-up visits | |

| Personalismo: Expectation of developing a warm, personal relationship with the clinician, including introductory touching. | Refusal to divulge important parts of medical history, dissatisfaction with treatment | |

| Respeto: Deferential behavior on the basis of age, social stature, and economic position, including reluctance to ask questions. | Mistaking a deferential nod of the head/not asking questions for understanding; anger at not receiving due signs of respect | |

| Familismo: Needs of the extended family outrank those of the individual, and thus family may need to be consulted in medical decision-making. | Unnecessary conflict, inability to reach a decision | |

| Muslim | Fasting during the holy month of Ramadan: fasting from sunrise to sundown, beginning during the teen years. Women are exempted during pregnancy, lactation, and menstruation, and there are exemptions for illness, but an exemption may be associated with a sense of personal failure. | Inappropriate therapy; will not take medicines during daytime misinterpreted as noncompliance; misdiagnosed |

| Modesty: Women's body, including hair, body, arms, and legs, not to be seen by men other than in immediate family. Female chaperone and/or husband must be present during exam, and only that part of the body being examined should be uncovered. | Deep personal outrage, seeking alternative care | |

| Touch: Forbidden to touch members of the opposite sex other than close family. Even a handshake may be inappropriate. | Patient discomfort, seeking care elsewhere | |

| After death , body belongs to God. Postmortem examination will not be permitted unless required by law; family may wish to perform after-death care. | Unnecessary intensification of grief and loss | |

| Cleanliness essential before prayer. Individual must perform ritual ablutions before prayer, especially elimination of urine and stool. Nurse may need to assist in cleaning if patient is incapable. | Affront to religious beliefs | |

| God's will: God causes all to happen for a reason, and only God can bring about healing. | Allopathic medicine will be rejected if it conflicts with religious beliefs, family may not seek healthcare. | |

| Patriarchal , extended family. Older male typically is head of household, and family may defer to him for decision-making. | Child's mother or even both parents may not be able to make decisions about child's care; emergency decisions may require additional time. | |

| Halal (permitted) vs haram (forbidden) foods and medications. Foods and medicine containing alcohol (some cough and cold syrups) or pork (some gelatin-coated pills) are not permitted. | Refusal of medication, religious effrontery | |

| Native American | Nature provides the spiritual, emotional, physical, social, and biologic means for human life; by caring for the earth, Native Americans will be provided for. Harmonious living is important. | Spiritual living is required of Native Americans; if treatments do not reflect this view, they are likely not to be followed. |

| Passive forbearance: Right of the individual to choose his or her path. Another family member cannot intervene. | Mother's failure to intervene in a child's behavior and/or use of noncoercive disciplinary techniques may be mistaken for neglect. | |

| Natural unfolding of the individual. Parents further the development of their children by limiting direct interventions and viewing their natural unfolding. | Many pediatric preventive practices will run counter to this philosophy. | |

| Talking circle format to decision-making. Interactive learning format including diverse tribal members. | Lecturing, excluding the views of elders, is likely to result in advice that will be disregarded. | |

| African-American | Great heterogeneity in beliefs and culture among African-Americans. | Risk of stereotyping and/or making assumptions that do not apply to a specific patient or family. |

| Extended family and variations in family size and childcare arrangements are common; matriarchal decision-making regarding healthcare. | Advice/instructions given only to the parent and not to others involved in health decision-making may not be effective. | |

| Parenting style often involves stricter adherence to rules than seen in some other cultures. | Advice regarding discipline may be disregarded if it is inconsistent with perceived norms; other parenting styles may not be effective. | |

| History-based widespread mistrust of medical profession and strong orientation toward culturally specific alternative/complementary medicine. | In patient noncompliance, physicians will be consulted as a last resort. | |

| Greater orientation toward others; the role of an individual is emphasized as it relates to others within a social network. | Compliance may be difficult if the needs of 1 individual are stressed above the needs of the group. | |

| Spirituality/religiosity important; church attendance central in most African American families. | Loss of opportunity to work with the church as an ally in healthcare | |

| East and Southeast Asian | Long history of Eastern medicines (e.g., Chinese medicine) as well as more localized medical traditions. | May engage with multiple health systems (Western biomedical and traditional) for treatment of symptoms and diseases |

| Extended families and care networks. Grandparents may provide day-to-day care for children while parents work outside of the home. | Parents may not be the only individuals a physician needs to communicate with in regard to symptoms, follow-through on treatments, and preventive behaviors. | |

| Sexually conservative. Strong taboos for premarital sexual relationships, especially for women. | Adolescents may be reluctant to talk about issues of sexuality, pregnancy, and birth control with physicians. Recent immigrants or native populations may have less knowledge regarding pregnancy prevention, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV. | |

| Infant/child feeding practices may overemphasize infant's or child's need to eat a certain amount of food to stay “healthy.” | Guidelines for child nutrition and feeding practices may not be followed out of concern for child's well-being. | |

| Saving face. This is a complex value whereby an individual may lose prestige or respect of a 3rd party when a 2nd individual makes negative or contradictory statements. | Avoid statements that are potentially value laden or imply a criticism of an individual. Use statements such as, “We have now found that it is better to …,” rather than criticizing a practice. | |

* Adherence to these or other beliefs will vary among members of a cultural group based on nation of origin, specific religious sect, degree of acculturation, age of patient, etc.

Table 11.4

Examples of Disease Beliefs and Health Practices in Select Cultures

| CULTURAL GROUP | BELIEF OR PRACTICE |

|---|---|

| Latino | Use of traditional medicines (nopales, or cooked prickly pear cactus, as a hypoglycemic agent) along with allopathic medicine. |

| Recognition of disorders not recognized in Western allopathic medicine (empacho , in which food adheres to the intestines or stomach), which are treated with folk remedies but also brought to the pediatrician. | |

| Cultural interpretation of disease (caida de mollera or “fallen fontanel”) as a cultural interpretation of severe dehydration in infants. | |

| Muslim | Female genital mutilation: practiced in some Muslim countries; the majority do not practice it, and it is not a direct teaching of the Koran. |

| Koranic faith healers: use verses from the Koran, holy water, and specific foods to bring about recovery. | |

| Native American | Traditional “interpreters” or “healers” interpret signs and answers to prayers. Their advice may be sought in addition or instead of allopathic medicine. |

| Dreams are believed to provide guidance; messages in the dream will be followed. | |

| East and Southeast Asian |

Concepts of “hot” and “cold,” whereby a combination of hot and cold foods and other substances (e.g., coffee, alcohol) combine to cause illness. One important aspect is that Western medicines are considered “hot” by Vietnamese, and therefore nonadherence may occur if it is perceived that too much of a medicine will make their child's body “hot.” Note: Hot and cold do not refer to temperatures but are a typology of different foods; for example, fish is hot and ginger is cold. Foods, teas, and herbs are also important forms of medicine because they provide balance between hot and cold. |