Poisoning

Jillian L. Theobald, Mark A. Kostic

Poisoning is the leading cause of injury-related death in the United States, surpassing that from motor vehicle crashes. Most these deaths are unintentional (i.e., not suicide). In adolescents, poisoning is the 3rd leading cause of injury-related death. Of the >2 million human poisoning exposures reported annually to the National Poison Data Systems (NPDS) of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC), approximately 50% occur in children <6 yr old, with the highest number of exposures occurring in 1 and 2 yr olds. Almost all these exposures are unintentional and reflect the propensity for young children to put virtually anything in their mouth. Fortunately, children <6 yr old account for <2% of all poisoning fatalities reported to NPDS.

More than 90% of toxic exposures in children occur in the home, and most involve a single substance. Ingestion accounts for the majority of exposures, with a minority occurring by the dermal, inhalational, and ophthalmic routes. Approximately 40% of cases involve nondrug substances, such as cosmetics, personal care items, cleaning solutions, plants, and foreign bodies. Pharmaceutical preparations account for the remainder of exposures, and analgesics, topical preparations, vitamins, and antihistamines are the most commonly reported categories.

The majority of poisoning exposures in children <6 yr old can be managed without direct medical intervention beyond a call to the regional poison control center (PCC) . This is because the product involved is not inherently toxic or the quantity of the material is not sufficient to produce clinically relevant toxic effects. However, a number of substances can be highly toxic to toddlers in small doses (Table 77.1 ). In 2015, carbon monoxide (CO), batteries, and analgesics (mainly opioids) were the leading causes of poison-related fatalities in young children (<6 yr). In addition, stimulants/street drugs, cardiovascular (CV) drugs, and aliphatic hydrocarbons were significant causes of mortality.

Table 77.1

| SUBSTANCE | TOXICITY |

|---|---|

| Aliphatic hydrocarbons (e.g., gasoline, kerosene, lamp oil) | Acute lung injury |

| Antimalarials (chloroquine, quinine) | Seizures, dysrhythmias |

| Benzocaine | Methemoglobinemia |

| β-Adrenergic receptor blockers † | Bradycardia, hypotension |

| Calcium channel blockers | Bradycardia, hypotension, hyperglycemia |

| Camphor | Seizures |

| Caustics (pH <2 or >12) | Airway, esophageal and gastric burns |

| Clonidine | Lethargy, bradycardia, hypotension |

| Diphenoxylate and atropine (Lomotil) | CNS depression, respiratory depression |

| Hypoglycemics, oral (sulfonylureas and meglitinides) | Hypoglycemia, seizures |

| Laundry detergent packets (pods) | Airway issues, respiratory distress, altered mental status |

| Lindane | Seizures |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Hypertension followed by delayed cardiovascular collapse |

| Methyl salicylate | Tachypnea, metabolic acidosis, seizures |

| Opioids (especially methadone, buprenorphine) | CNS depression, respiratory depression |

| Organophosphate pesticides | Cholinergic crisis |

| Phenothiazines (especially chlorpromazine, thioridazine) | Seizures, dysrhythmias |

| Theophylline | Seizures, dysrhythmias |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | CNS depression, seizures, dysrhythmias, hypotension |

* ”Small dose” typically implies 1 or 2 pills or 5 mL.

† Lipid-soluble β-blockers (e.g., propranolol) are more toxic than water-soluble β-blockers (e.g., atenolol).

CNS, Central nervous system.

Poison prevention education should be an integral part of all well-child visits, starting at the 6 mo visit. Counseling parents and other caregivers about potential poisoning risks, poison-proofing a child's environment, and actions in the event of an ingestion diminishes the likelihood of serious morbidity or mortality. Poison prevention education materials are available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and regional PCCs. Through a U.S. network of PCCs, anyone at any time can contact a regional poison center by calling the toll-free number 1-800-222-1222 . Parents should be encouraged to share this number with grandparents, relatives, babysitters, and any other caregivers.

Product safety measures, poison prevention education, early recognition of exposures, and around-the-clock access to regionally based PCCs all contribute to the favorable exposure outcomes in young children. Poisoning exposures in children 6-12 yr are much less common, involving only approximately 10% of all reported pediatric exposures. A 2nd peak in pediatric exposures occurs in adolescence. Exposures in the adolescent age-group are primarily intentional (suicide or abuse or misuse of substances) and thus often result in more severe toxicity (see Chapter 140 ). Families should be informed and given anticipatory guidance that nonprescription and prescription medications, and even household products (e.g., inhalants), are common sources of adolescent exposures. Although adolescents (age 13-19 yr) account for only about 12% of exposures, they constituted a much larger proportion of deaths. Of the 90 poison-related pediatric deaths in 2015 reported to NPDS, 58 were adolescents (5% of all fatalities called in to poison centers). Pediatricians should be aware of the signs of drug abuse or suicidal ideation in adolescents and should aggressively intervene (see Chapter 40 ).

Prevention

Deaths caused by unintentional poisoning among younger children have decreased dramatically over the past 2 decades, particularly among children <5 yr old. In 1970, when the U.S. Poison Packaging Prevention Act was passed, 226 poisoning deaths of children <5 yr old occurred, compared with only 24 in 2015. Poisoning prevention demonstrates the effectiveness of passive strategies, including the use of child-resistant packaging and limited doses per container. Difficulty using child-resistant containers by adults is an important cause of poisoning in young children today. In 18.5% of households in which poisoning occurred in children <5 yr old, the child-resistant closure was replaced, and 65% of the packaging used did not work properly. Almost 20% of ingestions occur from drugs belonging to grandparents, who have difficulty using traditional child-resistant containers and often put their medications in pill organizers that are not childproof.

Even though there has been success in preventing poisoning in young children, there has been a remarkable rise in adolescent poison-related death over the past 20 years. This has mirrored the increasing rate of antidepressant prescriptions written by healthcare providers and the epidemic increase in opioid-related fatalities.

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

The initial approach to the patient with a witnessed or suspected poisoning should be no different than that in any other sick child, starting with stabilization and rapid assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation (pulse, blood pressure), and mental state, including Glasgow Coma Scale score and laryngeal reflexes (see Chapters 80 and 81 ). In any patient with altered mental status, a serum dextrose concentration should be obtained early, and naloxone administration should be considered. A targeted history and physical examination serves as the foundation for a thoughtful differential diagnosis, which can then be further refined through laboratory testing and other diagnostic studies.

History

Obtaining an accurate problem-oriented history is of paramount importance. Intentional poisonings (suicide attempts, drug abuse/misuse) are typically more severe than unintentional, exploratory ingestions. In patients without a witnessed exposure, historical features such as age of the child (toddler or adolescent), acute onset of symptoms without prodrome, multisystem organ dysfunction, or high levels of household stress should suggest a possible diagnosis of poisoning. In patients with a witnessed exposure, determining exactly what the child was exposed to and the circumstances surrounding the exposure is crucial to initiating directed therapy quickly. For household and workplace products, names (brand, generic, chemical) and specific ingredients, along with their concentrations, can often be obtained from the labels. PCC specialists can also help to identify possible ingredients and review the potential toxicities of each component. Poison center specialists can also help identify pills based on markings, shape, and color. If referred to the hospital for evaluation, parents should be instructed to bring the products, pills, and/or containers with them to assist with identifying and quantifying the exposure. If a child is found with an unknown pill, a list of all medications in the child's environment, including medications that grandparents, parents, siblings, caregivers, or other visitors might have brought into the house, must be obtained. In the case of an unknown exposure, clarifying where the child was found (e.g., garage, kitchen, laundry room, bathroom, backyard, workplace) can help to generate a list of potential toxins.

Next, it is important to clarify the timing of the ingestion and to obtain some estimate of how much of the substance was ingested. It is better to overestimate the amount ingested to prepare for the worst-case scenario. Counting pills or measuring the remaining volume of a liquid ingested can sometimes be useful in generating estimates. For inhalational, ocular, or dermal exposures, the concentration of the agent and the length of contact time with the material should be determined, if possible.

Symptoms

Obtaining a description of symptoms experienced after ingestion, including their timing of onset relative to the time of ingestion and their progression, can generate a list of potential toxins and help anticipate the severity of the ingestion. Coupled with physical exam findings, reported symptoms assist practitioners in identifying toxidromes, or recognized poisoning syndromes, suggestive of toxicity from specific substances or classes of substances (Tables 77.2 to 77.4 ).

Table 77.2

Selected Historical and Physical Findings in Poisoning

| SIGN | TOXIN |

|---|---|

| ODOR | |

| Bitter almonds | Cyanide |

| Acetone | Isopropyl alcohol, methanol, paraldehyde, salicylates |

| Rotten eggs | Hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, methyl mercaptans (additive to natural gas) |

| Wintergreen | Methyl salicylate |

| Garlic | Arsenic, thallium, organophosphates, selenium |

| OCULAR SIGNS | |

| Miosis | Opioids (except propoxyphene, meperidine, and pentazocine), organophosphates and other cholinergics, clonidine, phenothiazines, sedative-hypnotics, olanzapine |

| Mydriasis | Anticholinergics (e.g., antihistamines, TCAs, atropine), sympathomimetics (cocaine, amphetamines, PCP), post–anoxic encephalopathy, opiate withdrawal, cathinones, MDMA |

| Nystagmus | Anticonvulsants, sedative-hypnotics, alcohols, PCP, ketamine, dextromethorphan |

| Lacrimation | Organophosphates, irritant gas or vapors |

| Retinal hyperemia | Methanol |

| CUTANEOUS SIGNS | |

| Diaphoresis | Cholinergics (organophosphates), sympathomimetics, withdrawal syndromes |

| Alopecia | Thallium, arsenic |

| Erythema | Boric acid, elemental mercury, cyanide, carbon monoxide, disulfiram, scombroid, anticholinergics, vancomycin |

| Cyanosis (unresponsive to oxygen) | Methemoglobinemia (e.g., benzocaine, dapsone, nitrites, phenazopyridine), amiodarone, silver |

| ORAL SIGNS | |

| Salivation | Organophosphates, salicylates, corrosives, ketamine, PCP, strychnine |

| Oral burns | Corrosives, oxalate-containing plants |

| Gum lines | Lead, mercury, arsenic, bismuth |

| GASTROINTESTINAL SIGNS | |

| Diarrhea | Antimicrobials, arsenic, iron, boric acid, cholinergics, colchicine, opioid withdrawal |

| Hematemesis | Arsenic, iron, caustics, NSAIDs, salicylates |

| Constipation | Lead |

| CARDIAC SIGNS | |

| Tachycardia | Sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, methylxanthines (theophylline, caffeine), salicylates, cellular asphyxiants (cyanide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide), withdrawal (ethanol, sedatives, clonidine, opioids), serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, MDMA, cathinones |

| Bradycardia | β-Blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, clonidine, organophosphates, opioids, sedative-hypnotics |

| Hypertension | Sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, clonidine withdrawal |

| Hypotension | β-Blockers, calcium channel blockers, cyclic antidepressants, iron, antipsychotics, barbiturates, clonidine, opioids, arsenic, amatoxin mushrooms, cellular asphyxiants (cyanide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide), snake envenomation |

| RESPIRATORY SIGNS | |

| Depressed respirations | Opioids, sedative-hypnotics, alcohol, clonidine, barbiturates |

| Tachypnea | Salicylates, sympathomimetics, caffeine, metabolic acidosis, carbon monoxide, hydrocarbon aspiration |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM SIGNS | |

| Ataxia | Alcohols, anticonvulsants, sedative-hypnotics, lithium, dextromethorphan, carbon monoxide, inhalants |

| Coma | Opioids, sedative-hypnotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, ethanol, anticholinergics, clonidine, GHB, alcohols, salicylates, barbiturates |

| Seizures | Sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, antidepressants (especially TCAs, bupropion, venlafaxine), cholinergics (organophosphates), isoniazid, camphor, lindane, salicylates, lead, nicotine, tramadol, water hemlock, withdrawal |

| Delirium/psychosis | Sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, LSD, PCP, hallucinogens, lithium, dextromethorphan, steroids, withdrawal, MDMA, cathinones |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Lead, arsenic, mercury, organophosphates, nicotine |

GHB, γ-Hydroxybutyrate; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy); NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; PCP, phencyclidine; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 77.3

Recognizable Poison Syndromes (“Toxidromes”)

| TOXIDROME | SIGNS | POSSIBLE TOXINS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Signs | Mental Status | Pupils | Skin | Bowel Sounds | Other | ||

| Sympathomimetic | Hypertension, tachycardia, hyperthermia | Agitation, psychosis, delirium, violence | Dilated | Diaphoretic | Normal to increased | Amphetamines, cocaine, PCP, bath salts (cathinones), ADHD medication | |

| Anticholinergic | Hypertension, tachycardia, hyperthermia | Agitated, delirium, coma, seizures | Dilated | Dry, hot | Diminished | Ileus urinary retention | Antihistamines, TCAs, atropine, jimsonweed |

| Cholinergic | Bradycardia, BP, and temp typically normal | Confusion, coma, fasciculations | Small | Diaphoretic | Hyperactive | Diarrhea, urination, bronchorrhea, bronchospasm, emesis, lacrimation, salivation | Organophosphates (insecticides, nerve agents), carbamates (physostigmine, neostigmine, pyridostigmine) Alzheimer medications, myasthenia treatments |

| Opioids | Respiratory depression bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia | Depression, coma, euphoria | Pinpoint | Normal | Normal to decreased | Methadone, buprenorphine, morphine, oxycodone, heroin, etc. | |

| Sedative-hypnotics | Respiratory depression, HR normal to decreased, BP normal to decreased, temp normal to decreased | Somnolence, coma | Small or normal | Normal | Normal | Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, ethanol | |

| Serotonin syndrome (similar findings with neuroleptic malignant syndrome) | Hyperthermia, tachycardia, hypertension or hypotension (autonomic instability) | Agitation, confusion, coma | Dilated | Diaphoretic | Increased | Neuromuscular hyperexcitability: clonus, hyperreflexia (lower > upper extremities) | SSRIs, lithium, MAOIs, linezolid, tramadol, meperidine, dextromethorphan |

| Salicylates | Tachypnea, hyperpnea, tachycardia, hyperthermia | Agitation, confusion, coma | Normal | Diaphoretic | Normal | Nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, ABGs with primary respiratory alkalosis and primary metabolic acidosis; tinnitus or difficulty hearing | Aspirin and aspirin-containing products, methyl salicylate |

| Withdrawal (sedative-hypnotic) | Tachycardia, tachypnea, hyperthermia | Agitation, tremor, seizure, hallucinosis, delirium tremens | Dilated | Diaphoretic | Increased | Lack of access to ethanol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB, or excessive use of flumazenil | |

| Withdrawal (opioid) | Tachycardia | Restlessness, anxiety | Dilated | diaphoretic | Hyperactive | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Lack of access to opioids or excessive use of naloxone |

ABGs, Arterial blood gases; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BP, blood pressure; GHB, γ-hydroxybutyrate; HR, heart rate; MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; PCP, phencyclidine; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; temp, temperature; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 77.4

| TOXIDROME | SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|---|

| α1 -Adrenergic receptor antagonists | CNS depression, tachycardia, miosis | Chlorpromazine, quetiapine, clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone |

| α2 -Adrenergic receptor agonist | CNS depression, bradycardia, hypertension (early), hypotension (late), miosis | Clonidine, oxymetazoline, tetrahydrozoline, tizanidine, dexmedetomidine |

| Clonus/myoclonus | CNS depression, myoclonic jerks, clonus, hyperreflexia | Carisoprodol, lithium, serotonergic agents, bismuth, organic lead, organic mercury, serotonin or neuroleptic malignant syndrome |

| Sodium channel blockers | CNS toxicity, wide QRS | Cyclic antidepressants and structurally related agents, propoxyphene, quinidine/quinine, amantadine, antihistamines, bupropion, cocaine |

| Potassium channel blockers | CNS toxicity, long QT interval | Antipsychotics, methadone, phenothiazines |

| Cathinones, synthetic cannabinoids | Hyperthermia, tachycardia, delirium, agitation, mydriases | See Chapter 140 . |

CNS, Central nervous system.

From Ruha AM, Levine M: Central nervous system toxicity. Emerg Med Clin North Am 32(1):205–221, 2014, p 208.

Past Medical and Developmental History

Underlying diseases can make a child more susceptible to the effects of a toxin. Concurrent drug therapy can also increase toxicity because certain drugs may interact with the toxin. A history of psychiatric illness can make patients more prone to substance abuse, misuse, intentional ingestions, and polypharmacy complications. Pregnancy is a common precipitating factor in adolescent suicide attempts and can influence both evaluation of the patient and subsequent treatment. A developmental history is important to ensure that the exposure history provided is appropriate for the child's developmental stage (e.g., report of 6 mo old picking up a large container of laundry detergent and drinking it should indicate urgent need for treatment, or indicate a severe condition, or “red flag”).

Social History

Understanding the child's social environment helps to identify potential sources of exposures (caregivers, visitors, grandparents, recent parties or social gatherings) and social circumstances (new baby, parent's illness, financial stress) that might have contributed to the ingestion (suicide or unintentional). Unfortunately, some poisonings occur in the setting of serious neglect or intentional abuse.

Physical Examination

A targeted physical examination is important to identifying the potential toxin and assessing the severity of the exposure. Initial efforts should be directed toward assessing and stabilizing the airway, breathing, circulation, and mental status. Once the airway is secure and the patient is stable from a cardiopulmonary standpoint, a more extensive physical exam can help to identify characteristic findings of specific toxins or classes of toxins.

In the poisoned patient, key features of the physical exam are vital signs, mental status, pupils (size, reactivity), nystagmus, skin, bowel sounds, and muscle tone. These findings might suggest a toxidrome, which can then guide the differential diagnosis and management.

Laboratory Evaluation

A basic chemistry panel (electrolytes, renal function, glucose) is necessary for all poisoned or potentially poisoned patients. Any patient with acidosis (low serum bicarbonate level on serum chemistry panel) must have an anion gap calculated because of the more specific differential diagnoses associated with an elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis (Table 77.5 ). Patients with a known overdose of acetaminophen should have liver transaminases (ALT, AST) assessed, as well as an international normalized ratio (INR). A serum creatinine kinase level is indicated on any patient with a prolonged “down time” to evaluate for rhabdomyolysis . Serum osmolality is only helpful as a surrogate marker for a toxic alcohol exposure if a serum concentration of the alcohol cannot be obtained in a reasonable time frame. A urine pregnancy test is mandatory for all postpubertal female patients. Based on the clinical presentation and the presumed poison, additional lab tests may also be helpful. Acetaminophen is a widely available medication and a commonly detected co-ingestant with the potential for severe toxicity. There is an effective antidote to acetaminophen poisoning that is time dependent. Given that patients might initially be asymptomatic and might not report or be aware of acetaminophen ingestion, an acetaminophen level should be checked in all patients who present after an intentional exposure or ingestion.

For select intoxications (e.g., salicylates, some anticonvulsants, acetaminophen, iron, digoxin, methanol, ethanol, lithium, ethylene glycol, theophylline, CO, lead), quantitative blood concentrations are integral to confirming the diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan. However, for most exposures, quantitative measurement is not readily available and is not likely to alter management. All intoxicant levels must be interpreted in conjunction with the history. For example, a methanol level of 20 mg/dL 1 hr after ingestion may be nontoxic, whereas a similar level 24 hr after ingestion implies a significant poisoning. In general, patients with multiple or chronic exposures to a drug or other chemical will be more symptomatic at lower drug levels than those with a single exposure.

Both the rapid urine drug-of-abuse screens and the more comprehensive drug screens vary widely in their ability to detect toxins and generally add little information to the clinical assessment. This is particularly true if the agent is known and the patient's symptoms are consistent with that agent. If a drug screen is ordered, it is important to know that the components screened for, and the lower limits of detection, vary from laboratory to laboratory. In addition, the interpretation of most drug screens is hampered by many false-positive and false-negative results. Many opiate toxicology screens poorly detect hydrocodone, and do not detect the fully synthetic opioids at all (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl). Several common benzodiazepines may not be detected, as may not synthetic cannabinoids or “bath salts.” The amphetamine screen, on the other hand, is typically overly sensitive and often is triggered by prescription amphetamines and some over-the-counter cold preparations. As such, the urine drug-of-abuse screen is typically of limited utility for medical clearance, but may serve a useful function for psychiatrists in their evaluation of the adolescent patient. Besides its psychiatric usefulness, urine drug-of-abuse screens are potentially helpful in patients with altered mental status of unknown etiology, persistent unexplained tachycardia, and acute myocardial ischemia or stroke at a young age. These screens can also be useful in the assessment of a neglected or abused child. Consultation with a medical toxicologist can be helpful in interpreting drug screens and directing which specific drug levels or other lab analyses might aid in patient management.

In the case of a neglected or allegedly abused child, a positive toxicology screen can add substantial weight to a claim of abuse or neglect. In these cases and any case with medicolegal implications, any positive screen mus t be confirmed with gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy, which is considered the gold standard measurement for legal purposes.

Additional Diagnostic Testing

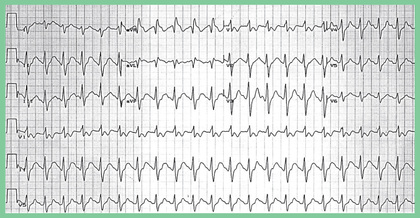

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a quick and noninvasive bedside test that can yield important clues to diagnosis and prognosis. Particular attention should be paid to the ECG intervals (Table 77.6 ). A widened QRS interval, putting the patient at risk for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, suggests blockade of fast sodium channels. A widened QTc interval suggests effects at the potassium rectifier channels and portends a risk of torsades de pointes (polymorphic ventricular tachycardia).

Chest radiography may reveal signs of pneumonitis (e.g., hydrocarbon aspiration), noncardiogenic pulmonary edema (e.g., salicylate toxicity), or a foreign body. Abdominal radiography is most helpful in screening for the presence of lead paint chips or other foreign bodies. It may detect a bezoar (concretion), demonstrate radiopaque tablets, or reveal drug packets in a “body packer.” Further diagnostic testing is based on the differential diagnosis and pattern of presentation.

Principles of Management

The principles of management of the poisoned patient are supportive care, decontamination, directed therapy (antidotes, ILE), and enhanced elimination. Few patients meet criteria for all these interventions, although clinicians should consider each option in every poisoned patient so as not to miss a potentially lifesaving intervention. Antidotes are available for relatively few poisons (Tables 77.7 and 77.8 ), thus emphasizing the importance of meticulous supportive care and close clinical monitoring.

Table 77.7

Common Antidotes for Poisoning

| POISON | ANTIDOTE | DOSAGE | ROUTE | ADVERSE EFFECTS, WARNINGS, COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | N -Acetylcysteine (Mucomyst) | 140 mg/kg loading, followed by 70 mg/kg q4h | PO | Vomiting (patient-tailored regimens are the norm) |

| N -Acetylcysteine (Acetadote) | 150 mg/kg over 1 hr, followed by 50 mg/kg over 4 hr, followed by 100 mg/kg over 16 hr | IV |

Anaphylactoid reactions (most commonly seen with loading dose) (Higher doses of the infusion are often recommended depending on acetaminophen level or degree of injury) |

|

| Anticholinergics | Physostigmine | 0.02 mg/kg over 5 min; may repeat q5-10 min to 2 mg max | IV/IM |

Bradycardia, seizures, bronchospasm Note: Do not use if conduction delays on ECG. |

| Benzodiazepines | Flumazenil | 0.2 mg over 30 sec; if response is inadequate, repeat q1min to 1 mg max | IV |

Agitation, seizures from precipitated withdrawal (doses over 1 mg) Do not use for unknown or polypharmacy ingestions. |

| β-Blockers | Glucagon | 0.15 mg/kg bolus followed by infusion of 0.05-0.15 mg/kg/hr | IV | Vomiting, relative lack of efficacy |

| Calcium channel blockers | Insulin | 1 unit/kg bolus followed by infusion of 0.5-1 unit/kg/hr | IV |

Hypoglycemia Follow serum potassium and glucose closely. |

| Calcium salts | Dose depends on the specific calcium salt | IV | ||

| Carbon monoxide | Oxygen | 100% FIO 2 by non-rebreather mask (or ET if intubated) | Inhalation | Some patients may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen (see text). |

| Cyanide | Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit) | 70 mg/kg (adults: 5 g) given over 15 min | IV | Flushing/erythema, nausea, rash, chromaturia, hypertension, headache |

| Digitalis | Digoxin-specific Fab antibodies (Digibind, DigiFab) |

1 vial binds 0.6 mg of digitalis glycoside; #vials = digitalis level × weight in kg/100 |

IV | Allergic reactions (rare), return of condition being treated with digitalis glycoside |

| Ethylene glycol, methanol | Fomepizole | 15 mg/kg load; 10 mg/kg q12h × 4 doses; 15 mg/kg q12h until ethylene glycol level is <20 mg/dL | IV |

Infuse slowly over 30 min. If fomepizole is not available, can treat with oral ethanol (80 proof) |

| Iron | Deferoxamine | Infusion of 5-15 mg/kg/hr (max: 6 g/24 hr) | IV | Hypotension (minimized by avoiding rapid infusion rates) |

| Isoniazid (INH) | Pyridoxine |

Empirical dosing: 70 mg/kg (max dose = 5 g) If ingested dose is known: 1 g per gram of INH |

IV | May also be used for Gyromitra mushroom ingestions |

| Lead and other heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, inorganic mercury) | BAL (dimercaprol) | 3-5 mg/kg/dose q4h, for the 1st day; subsequent dosing depends on the toxin | Deep IM |

Local injection site pain and sterile abscess, vomiting, fever, salivation, nephrotoxicity Caution: prepared in peanut oil; contraindicated in patients with peanut allergy |

| Calcium disodium EDTA | 35-50 mg/kg/day × 5 days; may be given as a continuous infusion or 2 divided doses/day | IV | Vomiting, fever, hypertension, arthralgias, allergic reactions, local inflammation, nephrotoxicity (maintain adequate hydration; follow UA and renal function) | |

| Dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer, DMSA, Chemet) | 10 mg/kg/dose q8h × 5 days, then 10 mg/kg q12h × 14 days | PO | Vomiting, hepatic transaminase elevation, rash | |

| Methemoglobinemia | Methylene blue, 1% solution | 0.1-0.2 mL/kg (1-2 mg/kg) over 5-10 min; may be repeated q30-60 min | IV | Vomiting, headache, dizziness, blue discoloration of urine |

| Opioids | Naloxone |

1 mg if patient not likely to be addicted. 0.04-0.4 mg if possibly addicted; repeated as needed; may need continuous infusion |

IV, intranasal, IO, IM, nebulized |

Acute withdrawal symptoms if given to addicted patients May also be useful for clonidine ingestions (typically at higher doses) |

| Organophosphates | Atropine | 0.05-0.1 mg/kg repeated q5-10 min as needed | IV/ET | Tachycardia, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention |

| Pralidoxime (2-PAM) | 25-50 mg/kg over 5-10 min (max: 200 mg/min); can be repeated after 1-2 hr, then q10-12h as needed | IV/IM | Nausea, dizziness, headache, tachycardia, muscle rigidity, bronchospasm (rapid administration) | |

| Salicylates | Sodium bicarbonate | Bolus 1-2 mEq/kg followed by continuous infusion | IV |

Follow potassium closely and replace as necessary. Goal urine pH: 7.5-8.0 |

| Sulfonylureas | Octreotide and dextrose | 1-2 µg/kg/dose (adults 50-100 µg) q6-8h | IV/SC | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Sodium bicarbonate | Bolus 1-2 mEq/kg; repeated bolus dosing as needed to keep QRS <110 msec | IV | Indications: QRS widening (≥110 msec), hemodynamic instability; follow potassium. |

BAL, British antilewisite; DMSA, dimercaptosuccinic acid; ECG, electrocardiogram; FIO 2 , fraction of inspired oxygen; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; ET, endotracheal tube; IO, intraosseous; max, maximum; UA, urinalysis.

Table 77.8

Poison control center personnel are specifically trained to provide expertise in the management of poisoning exposures. Parents should be instructed to call the poison control center (1-800-222-1222 ) for any concerning exposure. PCC specialists can assist parents in assessing the potential toxicity and severity of the exposure. They can further determine which children can be safely monitored at home and which children should be referred to the emergency department for further evaluation and care. Although up to one third of calls to PCCs involve hospitalized patients, and 90% of all calls for exposures in children <6 yr old are managed at home. The AAPCC has generated consensus statements for out-of-hospital management of common ingestions (e.g., acetaminophen, iron, calcium channel blockers) that serve to guide poison center recommendations.

Supportive Care

Careful attention is paid first to the “ABCs” of airway, breathing, and circulation; there should be a low threshold to aggressively manage the airway of a poisoned patient because of the patient's propensity to quickly become comatose. In fact, endotracheal intubation is often the only significant intervention needed in many poisoned patients. An important caveat is the tachypneic patient with a clear lung examination and normal oxygen saturation. This should alert the clinician to the likelihood that the patient is compensating for an acidemia. Paralyzing such a patient and underventilating might prove fatal. If intubation is absolutely necessary for airway protection or a tiring patient, a good rule of thumb is to match the ventilatory settings to the patient's preintubation minute ventilation.

Hypotensive patients often are not hypovolemic but are poisoned, and aggressive fluid resuscitation may lead to fluid overload. If hypotension persists after 1 or 2 standard boluses of crystalloid, infusion of a direct-acting vasopressor, such as norepinephrine or epinephrine, is preferred. Dysrhythmias are managed in the standard manner, except for those caused by agents that block fast sodium channels of the heart, for which boluses of sodium bicarbonate are given.

Seizures should primarily be managed with agents that potentiate the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) complex, such as benzodiazepines or barbiturates. The goal of supportive therapy is to support the patient's vital functions until the patient can eliminate the toxin. Patients with an elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) should be aggressively hydrated with crystalloid, with a goal urine output of 1-2 mL/kg/hr and close monitoring of CPK trend.

Decontamination

The majority of poisonings in children are from ingestion, although exposures can also occur by inhalational, dermal, and ocular routes. The goal of decontamination is to minimize absorption of the toxic substance. The specific method employed depends on the properties of the toxin itself and the route of exposure. Regardless of the decontamination method used, the efficacy of the intervention decreases with increasing time since exposure. Decontamination should not be routinely employed for every poisoned patient. Instead, careful decisions regarding the utility of decontamination should be made for each patient and should include consideration of the toxicity and pharmacologic properties of the exposure, route of the exposure, time since the exposure, and risks vs benefits of the decontamination method.

Dermal and ocular decontamination begins with removal of any contaminated clothing and particulate matter, followed by flushing of the affected area with tepid water or normal saline (NS). Treating clinicians should wear proper protective gear when performing irrigation. Flushing for a minimum of 10-20 min is recommended for most exposures, although some chemicals (e.g., alkaline corrosives) require much longer periods of flushing. Dermal decontamination, especially after exposure to adherent or lipophilic (e.g., organophosphates) agents, should include thorough cleansing with soap and water. Water should not be used for decontamination after exposure to highly reactive agents, such as elemental sodium, phosphorus, calcium oxide, and titanium tetrachloride. After an inhalational exposure, decontamination involves moving the patient to fresh air and administering supplemental oxygen if indicated.

Gastrointestinal (GI) decontamination strategies are most likely to be effective in the 1 or 2 hours after an acute ingestion . GI absorption may be delayed after ingestion of agents that slow GI motility (anticholinergic medications, opioids), massive amounts of pills, sustained-release (SR) preparations, and agents that can form pharmacologic bezoars (e.g., enteric-coated salicylates). GI decontamination more than 2 hr after ingestion may be considered in patients who ingest toxic substances with these properties. However, even rapid institution of GI decontamination with activated charcoal will, at best, bind only approximately 30% of the ingested substance. GI decontamination should never supplant excellent supportive care and should not be employed in an unstable or persistently vomiting patient. Described methods of GI decontamination include induced emesis with ipecac, gastric lavage, cathartics, activated charcoal, and whole-bowel irrigation (WBI). Of these, only activated charcoal and WBI are of potential benefit.

Syrup of Ipecac

Syrup of ipecac contains 2 emetic alkaloids that work in both the central nervous system (CNS) and locally in the GI tract to produce vomiting. Many studies have failed to document a significant clinical impact from the use of ipecac and have documented multiple adverse events from its use. The AAP, the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT), and the AAPCC have all published statements in favor of abandoning the use of ipecac.

Gastric Lavage

Gastric lavage involves placing a large tube orally into the stomach to aspirate contents, followed by flushing with aliquots of fluid, usually water or NS. Although gastric lavage was used routinely for many years, objective data do not document or support clinically relevant efficacy. This is particularly true in children, in whom only small-bore tubes can be used. Lavage is time-consuming and painful and can induce bradycardia through a vagal response to tube placement. It can delay administration of more definitive treatment (activated charcoal) and under the best circumstances, only removes a fraction of gastric contents. Thus, in most clinical scenarios, the use of gastric lavage is no longer recommended.

Single-Dose Activated Charcoal

Activated charcoal is a potentially useful method of GI decontamination. Charcoal is “activated” by heating to extreme temperatures, creating an extensive network of pores that provides a very large adsorptive surface area that many (but not all) toxins will bind to, preventing absorption from the GI tract. Charged molecules (i.e., heavy metals, lithium, iron) and liquids do not bind well to activated charcoal (Table 77.9 ). Charcoal is most likely to be effective when given within 1 hr of ingestion. Administration should also be avoided after ingestion of a caustic substance, as it can impede subsequent endoscopic evaluation. A repeat dose of activated charcoal may be warranted in the cases of ingestion of an extended-release product or, more frequently, with a significant salicylate poisoning as a result of its delayed and erratic absorption pattern.

The dose of activated charcoal, with or without sorbitol, is 1 g/kg in children or 50-100 g in adolescents and adults. Before administering charcoal, one must ensure that the patient's airway is intact or protected and that the patient has a benign abdominal examination. In the awake, uncooperative adolescent or child who refuses to drink the activated charcoal, there is little utility and potential morbidity associated with forcing activated charcoal down a nasogastric (NG) tube, and such practice should be avoided. In young children, practitioners can attempt to improve palatability by adding flavorings (chocolate or cherry syrup) or giving the mixture over ice cream. Approximately 20% of children vomit after receiving a dose of charcoal, emphasizing the importance of an intact airway and avoiding administration of charcoal after ingestion of substances that are particularly toxic when aspirated (e.g., hydrocarbons). If charcoal is given through a gastric tube in an intubated patient, placement of the tube should be carefully confirmed before activated charcoal is given. Instillation of charcoal directly into the lungs can have disastrous effects. Constipation is another common side effect of activated charcoal, and in rare cases, bowel perforation has been reported.

Cathartics (sorbitol, magnesium sulfate, magnesium citrate) have been used in conjunction with activated charcoal to prevent constipation and accelerate evacuation of the charcoal-toxin complex. There are no data demonstrating their value and numerous reports of adverse effects from cathartics, such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

Whole-Bowel Irrigation

Whole-bowel irrigation (WBI) involves instilling large volumes (35 mL/kg/hr in children or 1-2 L/hr in adolescents) of a polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (e.g., GoLYTELY) to “wash out” the entire GI tract. This technique may have some success for the ingestion of SR preparations, substances not well adsorbed by charcoal (e.g., lithium, iron), transdermal patches, foreign bodies, and drug packets. In children, WBI is most frequently administered to decontaminate the gut of a child whose abdominal radiograph demonstrates multiple lead paint chips. Careful attention should be paid to assessment of the airway and abdominal exam before initiating WBI. WBI should never be given to a patient with signs of obstruction or ileus or with a compromised airway. Given the rate of administration and volume needed to flush the system, WBI is typically administered by NG tube. WBI is continued until the rectal effluent is clear. If the WBI is for a child with ingested paint chips, the end-point will be clearing of the chips from the bowel based on repeat radiographs. Complications of WBI include vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal distention. Bezoar formation might respond to WBI but may also require endoscopy or surgery.

Directed Therapy

Antidotal Therapy

Antidotes are available for relatively few toxins (Tables 77.7 and 77.8 ), but early and appropriate use of an antidote is a key element in managing the poisoned patient.

Intralipid Emulsion Therapy

Intralipid emulsion (ILE) therapy is a potentially lifesaving intervention. ILE therapy sequesters fat-soluble drugs, decreasing their impact at target organs. It also enhances cardiac function by supplying an alternative energy source to a depressed myocardium and acting on calcium channels in the heart, increasing myocardial calcium and thus cardiac function. Intralipid is most effective as a reversal agent for toxicity from inadvertent intravenous (IV) injection of bupivacaine. Using the same 20% Intralipid used for total parenteral nutrition (TPN), a bolus dose of 1.5 mL/kg is given over 3 min, followed by an infusion of 0.25 mL/kg/min until recovery or until a total of 10 mL/kg has been infused. Lipophilic drugs, those in which the logarithm of the coefficient describing the partition between 2 solvents (hydrophobic phase and hydrophilic phase) is >2, have the most potential to be bound by ILE. These include, but are not limited to, calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem), bupropion, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Enhanced Elimination

Enhancing elimination results in increased clearance of a poison that has already been absorbed. It is only useful for a few toxins and in these cases is a potentially lifesaving intervention. Methods of enhanced elimination include urinary alkalinization, hemodialysis, and multidose activated charcoal.

Urinary Alkalinization

Urinary alkalinization enhances the elimination of drugs that are weak acids by forming charged molecules, which then become trapped in the renal tubules. Charged molecules, being polar and hydrophilic, do not easily cross cellular membranes, thus they remain in the renal tubules and are excreted. Urinary alkalinization is accomplished by a continuous infusion of sodium bicarbonate–containing IV fluids, with a goal urine pH of 7.5-8. Alkalinization of the urine is most useful in managing salicylate and methotrexate toxicity. Complications of urinary alkalinization include electrolyte derangements (e.g., hypokalemia, hypocalcemia), fluid overload, and excessive serum alkalinization. Serum pH should be closely monitored and not exceed a pH >7.55. Patients typically unable to tolerate the volumes required for alkalinization are those with heart failure, kidney failure, pulmonary edema, or cerebral edema.

Hemodialysis

Few drugs or toxins are removed by dialysis in amounts sufficient to justify the risks and difficulty of dialysis. Toxins amenable to dialysis have the following properties: low volume of distribution (<1 L/kg) with a high degree of water solubility, low molecular weight, and low degree of protein binding. Hemodialysis may be useful for toxicity from methanol, ethylene glycol, salicylates, theophylline, bromide, lithium, and valproic acid. Hemodialysis is also used to correct severe electrolyte disturbances and acid-base derangements resulting from the ingestion (e.g., severe metformin-associated lactic acidosis).

Multidose Activated Charcoal

Whereas single-dose activated charcoal is used as a method of decontamination, multidose activated charcoal (MDAC ) can help to enhance the elimination of certain toxins. MDAC is typically given as 0.5 g/kg every 4-6 hr (for 4 doses). MDAC enhances elimination by 2 proposed mechanisms: interruption of enterohepatic recirculation and “GI dialysis.” The concept of GI dialysis involves using the intestinal mucosa as a dialysis membrane and pulling toxins from the bloodstream back into the intraluminal space, where they are adsorbed to the charcoal. The AACT/European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists position statement recommends MDAC in managing significant ingestions of carbamazepine, dapsone, phenobarbital, quinine, and theophylline. As with single-dose activated charcoal, contraindications to use of MDAC include an unprotected airway and a concerning abdominal examination (e.g., ileus, distention, peritoneal signs). Thus the airway and abdominal exam should be assessed before each dose. A cathartic (e.g., sorbitol) may be given with the 1st dose, but it should not be used with subsequent doses because of the risk of dehydration and electrolyte derangements. Although MDAC reduces the serum level of an intoxicant quicker than without MDAC, it has not been shown to have a significant impact on outcome.

Select Compounds in Pediatric Poisoning

See other chapters for herbal medicines (Chapter 78 ), drugs of abuse (Chapter 140 ), and environmental health hazards (Chapters 735-741 ).

Pharmaceuticals

Analgesics

Acetaminophen.

Acetaminophen (APAP) is the most widely used analgesic and antipyretic in pediatrics, available in multiple formulations, strengths, and combinations. Consequently, APAP is commonly available in the home, where it can be unintentionally ingested by young children, taken in an intentional overdose by adolescents and adults, or inappropriately dosed in all ages. In the United States, APAP toxicity remains the most common cause of acute liver failure and is the leading cause of intentional poisoning death.

Pathophysiology.

APAP toxicity results from the formation of a highly reactive intermediate metabolite, N -acetyl-p -benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). In therapeutic use, only a small percentage of a dose (approximately 5%) is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2E1 to NAPQI, which is then immediately joined with glutathione to form a nontoxic mercapturic acid conjugate. In overdose, glutathione stores are overwhelmed, and free NAPQI is able to combine with hepatic macromolecules to produce hepatocellular necrosis. The single acute toxic dose of APAP is generally considered to be >200 mg/kg in children and >7.5-10 g in adolescents and adults. Repeated administration of APAP at supratherapeutic doses (>90 mg/kg/day for consecutive days) can lead to hepatic injury or failure in some children, especially in the setting of fever, dehydration, poor nutrition, and other conditions that serve to reduce glutathione stores.

Any child with a history of acute ingestion of >200 mg/kg (unusual in children <6 yr) or with an acute intentional ingestion of any amount should be referred to a healthcare facility for clinical assessment and measurement of a serum APAP level.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

Classically, 4 general stages of APAP toxicity have been described (Table 77.10 ). The initial signs are nonspecific (i.e., nausea and vomiting) and may not be present. Thus the diagnosis of APAP toxicity cannot be based on clinical symptoms alone, but instead requires consideration of the combination of the patient's history, symptoms, and laboratory findings.

Table 77.10

If a toxic ingestion is suspected, a serum APAP level should be measured 4 hr after the reported time of ingestion. For patients who present to medical care more than 4 hr after ingestion, a stat APAP level should be obtained. APAP levels obtained <4 hr after ingestion, unless “nondetectable,” are difficult to interpret and cannot be used to estimate the potential for toxicity. Other important baseline lab tests include hepatic transaminases, renal function tests, and coagulation parameters.

Treatment.

When considering the treatment of a patient poisoned or potentially poisoned with APAP, and after assessment of the ABCs, it is helpful to place the patient into one of the following four categories.

1 Prophylactic.

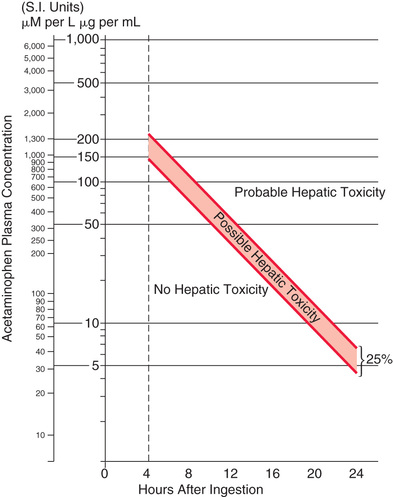

By definition, these patients have a normal aspartate transaminase (AST). If the APAP level is known and the ingestion is within 24 hr of the level being drawn, treatment decisions are based on where the level falls on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram (Fig. 77.1 ). Any patient with a serum APAP level in the possible or probable hepatotoxicity range per the nomogram should be treated with N -acetylcysteine (NAC). This nomogram is only intended for use in patients who present within 24 hr of a single acute APAP ingestion with a known time of ingestion. If treatment is recommended, they should receive NAC as either oral Mucomyst or IV Acetadote for 24 or 21 hr, respectively. Repeat AST and APAP concentration drawn toward the end of that interval should be obtained. If the AST remains normal and the APAP becomes nondetectable, treatment may be discontinued. If the AST becomes elevated, the patient moves into the next category of treatment (injury). If APAP is still present, treatment should be continued until the level is nondetectable. In the case of a patient with a documented APAP level, normal AST, and an unknown time of ingestion, treatment should ensue until the level is nondetectable, with normal transaminases.

The importance of instituting therapy with either IV or oral NAC no later than 8 hr from the time of ingestion cannot be overemphasized. No patient, regardless of the size of the ingestion, who receives NAC within 8 hr of overdose should die from liver failure. The longer from the 8 hr mark the initiation of therapy is delayed, the greater the risk of acute liver failure. Any patient presenting close to or beyond the 8 hr mark after an APAP overdose should be empirically started on NAC pending laboratory results.

2 Hepatic Injury.

These patients are exhibiting evidence of hepatocellular necrosis, manifested first as elevated liver transaminases (usually AST first, then alanine transaminase [ALT]), followed by a rise in the INR. Any patient in this category requires therapy with NAC (IV or oral). When to discontinue therapy in the clinically well patient remains controversial, but in general the transaminases and INR have peaked and fallen significantly “toward” normal (they do not need to be normal). Most patients' liver enzymes will peak 3 or 4 days after their ingestion.

3 Acute Liver Failure.

The King's College criteria are used to determine which patients should be referred for consideration of liver transplant. These criteria include acidemia (serum pH <7.3) after adequate fluid resuscitation, coagulopathy (INR >6), renal dysfunction (creatinine >3.4 mg/dL), and grade III or IV hepatic encephalopathy (see Chapter 391 ). A serum lactic acid >3 mmol/L (after IV fluids) adds to both sensitivity and specificity of the criteria to predict death without liver transplant. The degree of transaminase elevation does not factor in to this decision-making process.

4 Repeated Supratherapeutic Ingestion.

APAP is particularly prone to unintentional overdose through the ingestion of multiple medications containing the drug or simply because people assume it to be safe at any dose. Ingestion of amounts significantly greater than the recommended daily dose for several days or more puts one at risk for liver injury. Because the Rumack-Matthew nomogram is not helpful in this scenario, a conservative approach is taken. In the asymptomatic patient, if the AST is normal and the APAP is <10 µg/mL, no therapy is indicated. A normal AST and an elevated APAP warrants NAC dosing for at least long enough for the drug to metabolize while the AST remains normal. An elevated AST puts the patient in the “hepatic injury” category previously described. A patient presenting with symptoms (i.e., right upper quadrant pain, vomiting, jaundice) should be empirically started on NAC pending lab results.

NAC is available in oral and IV forms, and both are considered equally efficacious (see Table 77.7 for the dosing regimens of the oral vs IV form). The IV form is used in patients with intractable vomiting, those with evidence of hepatic failure, and pregnant patients. Oral NAC has an unpleasant taste and smell and can be mixed in soft drink or fruit juice or given by NG tube to improve tolerability of the oral regimen. Administration of IV NAC (as a standard 3% solution to avoid administering excess free water, typically in 5% dextrose), especially the initial loading dose, is associated in some patients with the development of anaphylactoid reactions (non–immunoglobulin E mediated). These reactions are typically managed by stopping the infusion; treating with diphenhydramine, albuterol, and/or epinephrine as indicated; and restarting the infusion at a slower rate once symptoms have resolved. IV NAC is also associated with mild elevation in measured INR (range: 1.2-1.5) because of laboratory interference. IV dosing, however, delivers less medication to the liver compared with the oral regimen. As a result, many toxicologists now recommend higher doses of the IV formulation in patients with large overdoses. Transaminases, synthetic function, and renal function should be followed daily while the patient is being treated with NAC. Patients with worsening hepatic function or clinical status might benefit from more frequent lab monitoring. A patient-tailored approach is now the norm for when to stop NAC therapy, for deciding whom to refer for transplantation evaluation, and often for the dose of IV NAC in patients with either very high APAP levels or signs of injury. Consultation with the regional PCC and medical toxicologist can help streamline the care of these patients, ultimately shortening their length of stay with potentially improved outcomes.

Salicylates.

The incidence of salicylate poisoning in young children has declined dramatically since APAP and ibuprofen replaced aspirin as the most commonly used analgesics and antipyretics in pediatrics. However, salicylates remain widely available, not only in aspirin-containing products but also in antidiarrheal medications, topical agents (e.g., keratolytics, sports creams), oil of wintergreen, and some herbal products. Oil of wintergreen contains 5 g of salicylate in 1 teaspoon (5 mL), meaning ingestion of very small volumes of this product has the potential to cause severe toxicity.

Pathophysiology.

Salicylates lead to toxicity by interacting with a wide array of physiologic processes, including direct stimulation of the respiratory center, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, inhibition of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and stimulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. The acute toxic dose of salicylates is generally considered to be >150 mg/kg. More significant toxicity is seen after ingestions of >300 mg/kg, and severe, potentially fatal, toxicity is described after ingestions of >500 mg/kg.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

Salicylate ingestions are classified as acute or chronic, and acute toxicity is much more common in pediatric patients. Early signs of acute salicylism include nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and tinnitus. Moderate salicylate toxicity can manifest as tachypnea and hyperpnea, tachycardia, and altered mental status. The tachycardia largely results from marked insensible losses from vomiting, tachypnea, diaphoresis, and uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Thus, careful attention should be paid to volume status and early volume resuscitation in the significantly poisoned patient. Signs of severe salicylate toxicity include mild hyperthermia, coma, and seizures. Chronic salicylism can have a more insidious presentation, and patients can show marked toxicity (e.g. altered mental status, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, acidemia) at significantly lower salicylate levels than in acute toxicity.

Classically, laboratory values from a patient poisoned with salicylates reveal a primary respiratory alkalosis and a primary, elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis. Early in the course of acute salicylism, respiratory alkalosis dominates and the patient is alkalemic. As the respiratory stimulation diminishes, the patient will move toward acidemia. Hyperglycemia (early) and hypoglycemia (late) have been described. Abnormal coagulation studies and acute kidney injury may be seen but are not common.

Serial serum salicylate levels should be closely monitored (every 2-4 hr initially) until they are consistently downtrending. Salicylate absorption in overdose is unpredictable and erratic, especially with an enteric-coated product, and levels can rapidly increase into the highly toxic range, even many hours after the ingestion. The Done nomogram is of poor value and should not be used. Serum and urine pH and electrolytes should be followed closely. An APAP level should be checked in any patient who intentionally overdoses on salicylates, because APAP is a common co-ingestant, and people often confuse or combine their nonprescription analgesic medications. Salicylate toxicity can cause a noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, especially in chronic overdose; consequently, a chest radiograph is recommended in any patient in respiratory distress.

Treatment.

For the patient who presents soon after an acute ingestion, initial treatment should include gastric decontamination with activated charcoal. Salicylate pills occasionally form bezoars, which should be suspected if serum salicylate concentrations continue to rise many hours after ingestion or are persistently elevated despite appropriate management. Gastric decontamination is typically not useful after chronic exposure.

Initial therapy focuses on aggressive volume resuscitation and prompt initiation of sodium bicarbonate therapy in the symptomatic patient, even before obtaining serum salicylate levels. Therapeutic salicylate levels are 10-20 mg/dL, and levels >25 or 30 mg/dL warrant treatment.

The primary mode of therapy for salicylate toxicity is urinary alkalinization . Urinary alkalinization enhances the elimination of salicylates by converting salicylate to its ionized form, “trapping” it in the renal tubules, thus enhancing elimination. In addition, maintaining an alkalemic serum pH decreases CNS penetration of salicylates because charged particles are less able to cross the blood-brain barrier. Alkalinization is achieved by administration of a sodium bicarbonate infusion at approximately 2 times maintenance fluid rates. The goals of therapy include a urine pH of 7.5-8, a serum pH of 7.45-7.55, and decreasing serum salicylate levels. In general, in the presence of an acidosis, an aspirin-poisoned patient's status can be directly related to the patient's serum pH: the lower the pH, the greater the relative amount of salicylate in the uncharged, nonpolar form and the greater the penetration of the blood-brain barrier by the drug. Careful attention should also be paid to serial potassium levels in any patient on a bicarbonate infusion, since potassium will be driven intracellularly and hypokalemia impairs alkalinization of the urine. For these reasons, potassium is often added to the bicarbonate drip. Repeat doses of charcoal may be beneficial because of the often delayed and erratic absorption of aspirin. Parenteral glucose should be provided to any salicylate-poisoned patients with altered mental status because they may have CNS hypoglycemia (i.e., neuroglycopenia) not seen in a peripheral serum glucose test.

In patients with severe toxicity, hemodialysis may be required. Indications for dialysis include severe acid-base abnormalities (specifically severe acidosis and acidemia), a rising salicylate level (despite adequate decontamination and properly alkalinized urine), pulmonary edema, cerebral edema, seizures, and renal failure. Serum salicylate concentrations alone are not a clear indicator of the need for dialysis and should always be interpreted along with the clinical status of the patient.

Ibuprofen and Other Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs).

Ibuprofen and other NSAIDs are often involved in unintentional and intentional overdoses because of their widespread availability and common use as analgesics and antipyretics. Fortunately, serious effects after acute NSAID overdose are rare because of their wide therapeutic index.

Pathophysiology.

NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis by reversibly inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), the primary enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of prostaglandins. In therapeutic use, side effects include GI irritation, reduced renal blood flow, and platelet dysfunction. To minimize these side effects, NSAID analogs have been developed that are more specific for the inducible form of COX (the COX-2 isoform) than the constitutive form, COX-1. However, overdose of the more selective COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib [Celebrex]) is treated the same as overdose of nonspecific COX inhibitors (e.g., ibuprofen) because at higher doses, COX-2–selective agents lose their COX inhibitory selectivity.

Ibuprofen, the primary NSAID used in pediatrics, is well tolerated, even in overdose. In children, acute doses of <200 mg/kg rarely cause toxicity, but ingestions of >400 mg/kg can produce more serious effects, including altered mental status and metabolic acidosis.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

Symptoms usually develop within 4-6 hr of ingestion and resolve within 24 hr. If toxicity does develop, it is typically manifested as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Although GI bleeding and ulcers have been described with chronic use, they are rare in the setting of acute ingestion. After massive ingestions, patients can develop marked CNS depression, anion gap metabolic acidosis, renal insufficiency, and (rarely) respiratory depression. Seizures have also been described, especially after overdose of mefenamic acid. Specific drug levels are not readily available, nor do they inform management decisions. Renal function studies, acid-base balance, complete blood count (CBC), and coagulation parameters should be monitored after very large ingestions. Co-ingestants, especially APAP, should be ruled out after any intentional ingestion.

Treatment.

Supportive care, including use of antiemetics and acid blockade as indicated, is the primary therapy for NSAID toxicity. Decontamination with activated charcoal should be considered if a patient presents within 1-2 hr of a potentially toxic ingestion. There is no specific antidote for this class of drugs. Given the high degree of protein binding and excretion pattern of NSAIDs, none of the modalities used to enhance elimination is particularly useful in managing these overdoses. Unlike in patients with salicylate toxicity, urinary alkalinization is not helpful for NSAID toxicity. Patients who develop significant clinical signs of toxicity should be admitted to the hospital for ongoing supportive care and monitoring. Patients who remain asymptomatic for 4-6 hr after ingestion may be considered medically cleared.

Prescription Opioids.

Opioids are a frequently abused class of medications in both IV and oral forms. The opioid epidemic gripping the United States and other countries is discussed in Chapter 140 . Two specific oral opioids, buprenorphine and methadone, merit mention because of potential life-threatening toxicity in toddlers with ingestion of even 1 pill. Both agents are used in managing opioid dependence, although buprenorphine is the drug of choice. Methadone is also widely used in the treatment of chronic pain, meaning multiday prescriptions can be filled. Both drugs are readily available for illicit purchase and potential abuse. Both drugs are of great potential toxicity to a toddler, especially buprenorphine because of its long half-life and high potency.

Pathophysiology.

Methadone is a lipophilic synthetic opioid with potent agonist effects at µ-opioid receptors, leading to both its desired analgesic effects and undesired side effects, including sedation, respiratory depression, and impaired GI motility. Methadone is thought to cause QTc interval prolongation through interactions with the human ether-a-go-go–related gene (hERG)-encoded potassium rectifier channel. Its duration of effect for pain control averages only about 8 hr, whereas the dangerous side effects can occur up to 24 hr from the last dose and longer after overdose. Methadone has an average half-life >25 hr, which may be extended to >50 hr in overdose.

Suboxone is a combination of buprenorphine, a potent opioid with partial agonism at µ-opioid receptors and weak antagonism at κ-opioid receptors, and naloxone. Naloxone has poor oral bioavailability but is included in the formulation to discourage diversion for IV use, during which it can precipitate withdrawal. Suboxone is formulated for buccal or sublingual administration; consequently, toddlers can absorb significant amounts of drug even by sucking on a tablet. Buprenorphine has an average half-life of 37 hr.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

In children, methadone and buprenorphine ingestions can manifest with the classic opioid toxidrome of respiratory depression, sedation, and miosis. Signs of more severe toxicity can include bradycardia, hypotension, and hypothermia. Even in therapeutic use, methadone is associated with a prolonged QTc interval and risk of torsades de pointes. Accordingly, an ECG should be part of the initial evaluation after ingestion of methadone or any unknown opioid. Neither drug is detected on routine urine opiate screens, although some centers have added a separate urine methadone screen. Levels of both drugs can be measured, although this is rarely done clinically and is seldom helpful in the acute setting. An exception may be in the cases involving concerns about neglect or abuse, at which point urine for gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy, the legal gold standard, should be sent to confirm and document the presence of the drug.

Treatment.

Patients with significant respiratory depression or CNS depression should be treated with the opioid antidote naloxone (see Table 77.7 ). In pediatric patients who are not chronically taking opioids, the full reversal dose of 1-2 mg should be used. In contrast, opioid-dependent patients should be treated with smaller initial doses (0.04-0.4 mg), which can then be repeated as needed to achieve the desired clinical response, avoiding abrupt induction of withdrawal. Because the half-life of methadone and buprenorphine is much longer than that of naloxone, patients can require multiple doses of naloxone. These patients may benefit from a continuous infusion of naloxone, typically started at two thirds of the reversal dose per hour and titrated to maintain an adequate respiratory rate and level of consciousness. Patients who have ingested methadone should be placed on a cardiac monitor and have serial ECGs to monitor for the development of a prolonged QTc interval. If a patient does develop a prolonged QTc, management includes close cardiac monitoring, repletion of electrolytes (potassium, calcium, and magnesium), and having a defibrillator readily available should the patient develop torsades de pointes.

Given the potential for clinically significant and prolonged toxicity, any toddler who has ingested methadone, even if asymptomatic, should be admitted to the hospital for at least 24 hr of monitoring. Some experts advocate a similar approach to management of buprenorphine ingestions, even in the asymptomatic patient. All such cases should be discussed with a PCC or medical toxicologist before determining disposition.

Cardiovascular Medications

β-Adrenergic Receptor Blockers.

β-Blockers competitively inhibit the action of catecholamines at the β-adrenergic receptor. Therapeutically, β-blockers are used for a variety of conditions, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, tachydysrhythmias, anxiety disorders, migraines, essential tremor, and hyperthyroidism. Because of its lipophilicity and blockade of fast sodium channels, propranolol is considered to be the most toxic member of the β-blocker class. Overdoses of water-soluble β-blockers (e.g., atenolol) are associated with milder symptoms.

Pathophysiology.

In overdose, β-blockers decrease chronotropy and inotropy in addition to slowing conduction through atrioventricular nodal tissue. Clinically, these effects are manifested as bradycardia, hypotension, and heart block. Patients with reactive airways disease can experience bronchospasm as a result of blockade of β2 -mediated bronchodilation. β2 -Blockers interfere with glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, which can sometimes lead to hypoglycemia, especially in patients with poor glycogen stores (e.g., toddlers).

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

Toxicity typically develops within 6 hr of ingestion, although it may be delayed after ingestion of sotalol or slow-release (SR) preparations. The most common features of severe poisoning are bradycardia and hypotension. Lipophilic agents, including propranolol, can enter the CNS and cause altered mental status, coma, and seizures. Overdose of β-blockers with membrane-stabilizing properties (e.g., propranolol) can cause QRS interval widening and ventricular dysrhythmias.

Evaluation after β-blocker overdose should include an ECG, frequent reassessments of hemodynamic status, and blood glucose. Serum levels of β-blockers are not readily available for routine clinical use and are not useful in management of the poisoned patient.

Treatment.

In addition to supportive care and GI decontamination as indicated, glucagon is theoretically the preferred antidote of choice for β-blocker toxicity (see Table 77.7 ). Glucagon stimulates adenyl cyclase and increases levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) independent of the β-receptor. Glucagon is typically given as a bolus and, if this is effective, followed by a continuous infusion. In practice, glucagon is often only marginally effective, limited by its proemetic effects, especially at the high doses typically required. Other potentially useful interventions include calcium, vasopressors, and high-dose insulin. Seizures are managed with benzodiazepines, and QRS widening should be treated with sodium bicarbonate. Children who ingest 1 or 2 water-soluble β-blockers are unlikely to develop toxicity and can typically be discharged to home if they remain asymptomatic over a 6 hr observation period. Children who ingest SR products, highly lipid-soluble agents, and sotalol can require longer periods of observation before safe discharge. Any symptomatic child should be admitted for ongoing monitoring and directed therapy.

Calcium Channel Blockers.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are used for a variety of therapeutic indications and have the potential to cause severe toxicity, even after exploratory ingestions. Specific agents include verapamil, diltiazem, and the dihydropyridines (e.g., amlodipine, nifedipine). Of these, diltiazem and verapamil are the most dangerous in overdose because of their higher lipophilicity and direct cardiac suppressant effects.

Pathophysiology.

CCBs antagonize L -type calcium channels, inhibiting calcium influx into myocardial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Verapamil works primarily by slowing inotropy and chronotropy and has no effect on systemic vascular resistance (SVR). Diltiazem has effects both on the heart and the peripheral vasculature. The dihydropyridines exclusively diminish SVR. Verapamil and diltiazem can significantly diminish myocardial contractility and conduction, with diltiazem also lowering SVR. By contrast, dihydropyridines will decrease the SVR, leading to vasodilation and reflex tachycardia, although this receptor selectivity may be lost after a large overdose. Because the same L -type calcium channels blocked by CCBs are also on the pancreatic islet cells, any patient significantly poisoned with a CCB usually is hyperglycemic.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

The onset of symptoms typically is soon after ingestion, although it may be delayed with ingestions of SR products. Overdoses of CCBs lead to hypotension, accompanied by bradycardia, normal heart rate, or even tachycardia, depending on the agent. A common feature of CCB overdose is the patient exhibiting profound hypotension with preserved consciousness.

Initial evaluation should include an ECG, continuous and careful hemodynamic monitoring, and rapid measurement of serum glucose levels. Both the absolute degree of hyperglycemia and the percentage increase in serum glucose have been correlated with the severity of CCB toxicity in adults. The development of hyperglycemia can even precede the development of hemodynamic instability. Blood levels of CCBs are not readily available and are not useful in guiding therapy.

Treatment.

Once initial supportive care has been instituted, GI decontamination should begin with activated charcoal as appropriate. WBI may be beneficial in a stable patient after ingestion of an SR product. Calcium channel blockade in the smooth muscles of the GI tract can lead to greatly diminished motility; thus any form of GI decontamination should be undertaken with careful attention to serial abdominal tests.

Calcium salts, administered through a peripheral IV line as calcium gluconate or a central line as calcium chloride, help to overcome blocked calcium channels. High-dose insulin euglycemia therapy is considered the antidote of choice for CCB toxicity. An initial bolus of 1 unit/kg of regular insulin is followed by an infusion at 0.5-1 unit/kg/hr (see Table 77.7 ). The main mechanism of high-dose insulin euglycemia is to improve the metabolic efficiency of a poisoned heart that is in need of carbohydrates for energy (instead of the usual free fatty acids), but has minimal circulating insulin. Blood glucose levels should be closely monitored, and supplemental glucose may be given to maintain euglycemia, although this is rarely necessary in the severely poisoned patient.

Additional therapies include judicious IV fluid boluses and vasopressors (often in very high doses). Cardiac pacing is rarely of value. Lipid emulsion therapy (discussed earlier) is a potentially lifesaving intervention, especially for patients poisoned with the more lipid-soluble CCBs, verapamil and diltiazem. In extreme cases an intraaortic balloon pump or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) are potential rescue devices. Given the potential for profound and sometimes delayed toxicity in toddlers after ingestion of 1 or 2 CCB tablets, hospital admission and 12-24 hr of monitoring for all of these patients is strongly recommended.

Clonidine.

Although originally intended for use as an antihypertensive, the number of clonidine prescriptions in the pediatric population has greatly increased because of its reported efficacy in the management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), tic disorders, and other behavioral disorders. With this increased use has come a significant rise in pediatric ingestions and therapeutic misadventures. Clonidine is available in pill and transdermal patch forms.

Pathophysiology.

Clonidine, along with the closely related agent guanfacine , is a centrally acting α2 -adrenergic receptor agonist with a very narrow therapeutic index. Agonism at central α2 receptors decreases sympathetic outflow, producing lethargy, bradycardia, hypotension, and apnea. Toxicity can develop after ingestion of only 1 pill or after sucking on or swallowing a discarded transdermal patch. Even a “used” transdermal patch might contain as much as one-third to one-half the original amount of drug.

Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations.

The most common clinical manifestations of clonidine toxicity are lethargy, miosis, and bradycardia. Hypotension, respiratory depression, and apnea may be seen in severe cases. Very early after ingestion, patients may be hypertensive in the setting of agonism at peripheral α-receptors and resulting vasoconstriction. Symptoms develop relatively soon after ingestion and typically resolve within 24 hr. Serum clonidine concentrations are not readily available and are of no clinical value in the acute setting. Although signs of clinical toxicity are common after clonidine overdose, death from clonidine alone is extremely unusual.

Treatment.

Given the potential for significant toxicity, most young children warrant referral to a healthcare facility for evaluation after unintentional ingestions of clonidine. Gastric decontamination is usually of minimal value because of the small quantities ingested and the rapid onset of serious symptoms. Aggressive supportive care is imperative and is the cornerstone of management. Naloxone, often in high doses, has shown variable efficacy in treating clonidine toxicity. Other potentially useful therapies include atropine, IV fluid boluses, and vasopressors. Symptomatic children should be admitted to the hospital for close cardiovascular and neurologic monitoring. Also, in a patient receiving chronic clonidine or guanfacine therapy, rapid discontinuation of the drug, or even missing 1 or 2 doses, could lead to potentially dangerous elevations in blood pressure.

Digoxin.