Spinal Cord Injuries in Children

Mark R. Proctor

See also Chapter 729 .

Compared with adults, spine and spinal cord injuries are rare in children, particularly young children, because of both anatomic differences and etiologies of injury. The main mechanisms of injury to the spine are motor vehicle crashes, falls, sports, and violence, which affect young children less often (see Chapter 82 ).

Several anatomic differences affect the pediatric spine. The head of a young child is larger relative to body mass than in adults, and the neck muscles are still underdeveloped, which places the fulcrum of movement higher in the spine. Therefore, children <9 yr old have a higher percentage of injuries in the upper cervical spine than older children and adults. The spine of a small child also is very mobile, with pliable bones and ligaments, so fractures of the spine are exceedingly rare. However, this increased mobility is not always a positive feature. Transfer of energy leading to spinal distortion may not affect the structural integrity of the bones and ligaments of the spine but can still lead to significant injuries of the spinal cord. This phenomenon of spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities (SCIWORA) is more common in children than adults. The term is relatively outdated, since almost all injuries are detectable by MRI, but is still clinically useful when referring to spinal cord injuries evaluated by plain radiographs or CT. There seem to be 2 distinct forms of SCIWORA. The infantile form involves severe injury of the cervical or thoracic spinal cord; these patients have a poor chance of complete recovery. In older children and adolescents, SCIWORA is more likely to be a less severe injury, with a high likelihood of complete recovery over time. The adolescent form, also called transient neurapraxia , is assumed to be a spinal cord concussion or mild contusion, as opposed to the severe spinal cord injury related to the mobility of the spine in small children.

Although the mechanisms of spinal cord injury in children include birth trauma, falls, and child abuse, the major cause of morbidity and mortality across all ages remains motor vehicle injuries . Adolescents incur spinal cord injuries with epidemiology similar to that of adults, including significant male predominance and a high likelihood of fracture dislocations of the lower cervical spine or thoracolumbar region. In infants and children <5 yr old, fractures and mechanical disruption of spinal elements are more likely to occur in the upper cervical spine between the occiput and C3, for the reasons previously discussed.

Clinical Manifestations

One in 3 patients with significant trauma to the spine and spinal cord will have a concomitant severe head injury, which makes early diagnosis challenging. For these patients, clinical evaluation may be difficult. Patients with a potential spine injury need to be maintained in a protective environment, such as a collar, until the spine can be cleared by clinical and/or radiographic means. A careful neurologic examination is necessary for infants with suspected spinal cord injuries. Complete spinal cord injury will lead to spinal shock with early areflexia (see Chapter 729 ). Severe cervical spinal cord (C-spine) injuries will usually lead to paradoxical respiration in patients who are breathing spontaneously. Paradoxical respiration occurs when the diaphragm, which is innervated by the phrenic nerves with contributions from C3, C4, and C5, is functioning normally, but the intercostal musculature innervated by the thoracic spinal cord is paralyzed. In this situation, inspiration fails to expand of the chest wall but distends the abdomen. Other complications during the acute (2-48 hr) phase include autonomic dysfunction (brady- and tachyarrhythmias, orthostatic hypotension, hypertension), temperature instability, thromboembolism, dysphagia, and bowel/bladder dysfunction.

The mildest injury to the spinal cord is transient quadriparesis evident for seconds or minutes with complete recovery in 24 hr. This injury follows a concussion of the cord and is most frequently seen in adolescent athletes. If their imaging is normal, these children can generally return to normal activities after a period of rest from days to weeks, depending on the initial severity, similar to cerebral concussion management.

Significant spinal cord injury in the cervical region is characterized by: flaccid quadriparesis, loss of sphincter function, and a sensory level corresponding to the level of injury. An injury at the high cervical level (C1-C2) can cause respiratory arrest and death in the absence of ventilatory support. Injuries in the thoracic region are generally the result of fracture dislocations. They may produce paraplegia when at T10 or above, or the conus medullaris syndrome if at the T12-L1 level. This includes a loss of urinary and rectal sphincter control, flaccid weakness, and sensory disturbances of the legs. A central cord lesion may result from contusion and hemorrhage in the center of the spinal cord. It typically involves the upper extremities to a greater degree than the legs, because the motor fibers to the cervical and thoracic region are more centrally located in the spinal cord. There are lower motor neuron signs in the upper extremities and upper motor neuron signs in the legs, bladder dysfunction, and loss of sensation caudal to the lesion. There may be considerable recovery, particularly in the lower extremities, although sequelae are common (see Chapter 729 ).

Clearing the Cervical Spine in Children

The management of children following major trauma is challenging. For older children, the clearance is similar to a lucid adult, and the NEXUS (National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study) criteria are appropriate (see Chapter 82 , Table 82.5 ). Clearing the cervical spine in younger and uncooperative children involves similar issues as in adults with an altered level of consciousness. Small children generally have a difficult-to-assess physical examination, and it is difficult to determine if they have cervical pain. Plain radiography remains a mainstay for assessing the spine because it is easy to obtain. There has been increasing emphasis on MRI for evaluation of potential C-spine instability, but in small children MRI requires sedation and in most centers the presence of an anesthesiologist (Fig. 83.1 ). CT scan is another important study with high sensitivity and specificity, but the risk of radiation exposure must be considered.

Treatment

The cervical spine should be immobilized in the field by the emergency medical technicians. In cases of acute spinal cord injury, weak data suggest the acute infusion of a bolus of high-dose (30 mg/kg) methylprednisolone, followed by a 23 hr infusion (5.4 mg/kg/hr). The data for this treatment are controversial and have not been tested specifically in children; many centers no longer use it routinely . Maintenance of euvolemia and normotension are very important, and vasopressors might be needed if the sympathetic nervous system has been compromised.

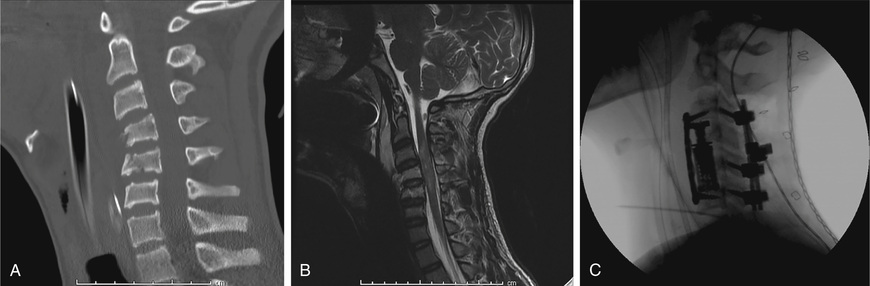

Surgical management of spinal injuries must be tailored to the patient's age but can be a crucial step in management. Any compression of the spinal cord must be surgically relieved to afford the best chance of a favorable outcome. In addition, spinal cord injury can be worsened by instability, so surgical stabilization can prevent further injury (Fig. 83.2 ). In general, younger children have a higher healing capacity for bones and ligaments, and external immobilization might be considered for injuries that require surgery in older children and adults. However, some injuries are highly unstable and always require surgery. Occipitocervical dislocation is one such highly unstable injury, and early surgery with fusion from the occiput to C2 or C3 should be performed, even in very young children. Fixation of the subaxial spine must be tailored to the size of the pedicles and other osseous structures of the developing axial skeleton.

Prevention

The most important aspect of the care of spinal cord injuries in children is injury prevention. Use of appropriate child restraints in automobiles is the most important precaution. In older children and adolescents, rules against “spear tackling” in American football and the Feet First, First Time aimed at adolescents diving into swimming pools and natural water areas are important ways to help prevent severe cervical spinal cord injuries. Safe driving practices, such as using safety belts, avoiding distracted driving, and following the speed limit, can have substantial beneficial effects on injury rates.