Nervous System Disorders

Stephanie L. Merhar, Cameron W. Thomas

Central nervous system (CNS) disorders are important causes of neonatal mortality and both short-term and long-term morbidity. The CNS can be injured as a result of asphyxia, hemorrhage, trauma, hypoglycemia, or direct cytotoxicity. The etiology of CNS injury is often multifactorial and includes perinatal complications, postnatal hemodynamic instability, and developmental abnormalities that may be genetic and/or environmental. Predisposing factors for brain injury include chronic and acute maternal illness resulting in uteroplacental dysfunction, intrauterine infection, macrosomia/dystocia, malpresentation, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction. Acute and often unavoidable emergencies during the delivery process may result in mechanical and hypoxic-ischemic brain injury.

The Cranium

Stephanie L. Merhar, Cameron W. Thomas

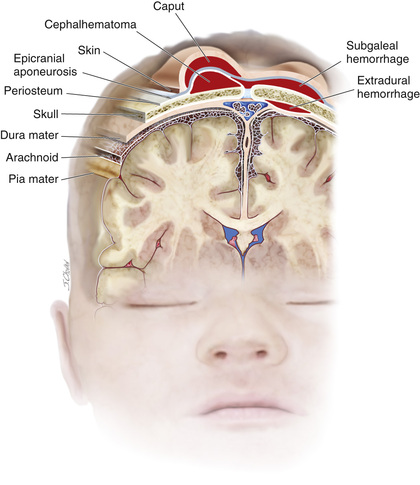

Erythema, abrasions, ecchymoses, and subcutaneous fat necrosis of facial or scalp soft tissues may be noted after a normal delivery or after forceps or vacuum-assisted deliveries. The location depends on the area of contact with the pelvic bones or application of the forceps. Traumatic hemorrhage may involve any layer of the scalp as well as intracranial contents (Fig. 120.1 ).

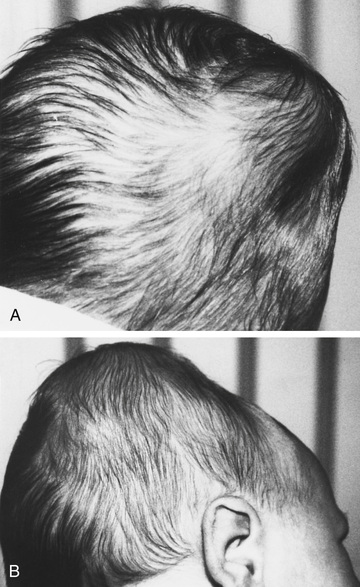

Caput succedaneum is a diffuse, sometimes ecchymotic, edematous swelling of the soft tissues of the scalp involving the area presenting during vertex delivery. It may extend across the midline and across suture lines. The edema disappears within the 1st few days of life. Molding of the head and overriding of the parietal bones are frequently associated with caput succedaneum and become more evident after the caput has receded; they disappear during the 1st few weeks of life. Rarely, a hemorrhagic caput may result in shock and require blood transfusion. Analogous swelling, discoloration, and distortion of the face are seen in face presentations. No specific treatment is needed, but if extensive ecchymoses are present, hyperbilirubinemia may develop.

Cephalohematoma is a subperiosteal hemorrhage and thus always limited to the surface of one cranial bone (Fig. 120.2 ). Cephalohematomas occur in 1–2% of live births. No discoloration of the overlying scalp occurs, and swelling is not usually visible for several hours after birth because subperiosteal bleeding is a slow process. The lesion becomes a firm, tense mass with a palpable rim localized over one area of the skull. Most cephalohematomas are resorbed within 2 wk to 3 mo, depending on their size. They may begin to calcify by the end of the 2nd wk. A few remain for years as bony protuberances and are detectable on radiographs as widening of the diploic space; cystlike defects may persist for months or years. An underlying skull fracture, usually linear and not depressed, may be associated with 10–25% of cases. A sensation of central depression suggesting but not indicative of an underlying fracture or bony defect is usually encountered on palpation of the organized rim of a cephalohematoma. Cephalohematomas require no treatment, although phototherapy may be necessary to treat hyperbilirubinemia. Infection of the hematoma is a very rare complication.

A subgaleal hemorrhage is a collection of blood beneath the aponeurosis that covers the scalp and serves as the insertion for the occipitofrontalis muscle (see Fig. 120.1 ). Bleeding can be very extensive into this large potential space and may even dissect into subcutaneous tissues of the neck. There is often an association with vacuum-assisted delivery. The mechanism of injury is most likely secondary to rupture of emissary veins connecting the dural sinuses within the skull and the superficial veins of the scalp. Subgaleal hemorrhages are sometimes associated with skull fractures, suture diastasis, and fragmentation of the superior margin of the parietal bone. Extensive subgaleal bleeding is occasionally secondary to a hereditary coagulopathy (hemophilia ). A subgaleal hemorrhage manifests as a fluctuant mass that straddles cranial sutures or fontanels that increases in size after birth. Some patients have a consumptive coagulopathy from massive blood loss. Patients should be monitored for hypotension, anemia, and hyperbilirubinemia. These lesions typically resolve over 2-3 wk.

Fractures of the skull may be caused by pressure from forceps or the maternal pelvis or by accidental falls after birth. Linear fractures, the most common, cause no symptoms and require no treatment. Linear fractures should be followed up to demonstrate healing and to detect the possible complication of a leptomeningeal cyst. Depressed fractures indent the calvaria similar to dents in a Ping-Pong ball. They are generally a complication of forceps delivery or fetal compression. Affected infants may be asymptomatic unless they have associated intracranial injury; it is advisable to elevate severe depressions to prevent cortical injury from sustained pressure. Although some may elevate spontaneously, some require treatment. Use of a breast pump or vacuum extractor may obviate the need for neurosurgical intervention. Suspected skull fractures should be evaluated with CT (3D reconstruction may be helpful) to confirm fracture and rule out associated intracranial injury.

Subconjunctival and retinal hemorrhages are frequent; petechiae of the skin of the head and neck are also common. All are probably secondary to a sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure during passage of the chest through the birth canal. Parents should be assured that these hemorrhages are temporary and the result of normal events of delivery. The lesions resolve rapidly within the 1st 2 wk of life.

Traumatic, Epidural, Subdural, and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Stephanie L. Merhar, Cameron W. Thomas

Traumatic epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid hemorrhage is especially likely when the fetal head is large in proportion to the size of the mother's pelvic outlet, with prolonged labor, in breech or precipitous deliveries, or as a result of mechanical assistance with delivery. Massive subdural hemorrhage , often associated with tears in the tentorium cerebelli or less frequently in the falx cerebri, is rare but is encountered more often in full-term than in premature infants. Patients with massive hemorrhage caused by tears of the tentorium or falx cerebri rapidly deteriorate and may die soon after birth. Most subdural and epidural hemorrhages resolve without intervention. Consultation with a neurosurgeon is recommended. Asymptomatic subdural hemorrhage may be noted within 48 hr of birth after vaginal or cesarean delivery. These are typically small hemorrhages, especially common in the posterior fossa, discovered incidentally in term infants imaged in the neonatal period and usually of no clinical significance. The diagnosis of large subdural hemorrhage may be delayed until the chronic subdural fluid volume expands and produces macrocephaly, frontal bossing, a bulging fontanel, anemia, and sometimes seizures. CT scan and MRI are useful imaging techniques to confirm these diagnoses. Symptomatic subdural hemorrhage in term infants can be treated by a neurosurgical evacuation of the subdural fluid collection by a needle placed through the lateral margin of the anterior fontanel. In addition to birth trauma, child abuse must be suspected in all infants with subdural effusion after the immediate neonatal period. Most asymptomatic subdural hemorrhages following labor should resolve by 4 wk of age.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is often clinically silent in the neonate. Anastomoses between the penetrating leptomeningeal arteries or the bridging veins are the most likely source of the bleeding. Most affected infants have no clinical symptoms, but the subarachnoid hemorrhage may be detected because of an elevated number of red blood cells in a lumbar puncture sample. Some infants experience short, benign seizures, which tend to occur on the 2nd day of life. Rarely, an infant has a catastrophic hemorrhage and dies. There are usually no neurologic abnormalities during the acute episode or on follow-up. Significant neurologic findings should suggest an arteriovenous malformation, which can best be detected on CT or MRI.

Intracranial-Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Periventricular Leukomalacia

Stephanie L. Merhar, Cameron W. Thomas

Etiology

Intracranial hemorrhage in preterm infants usually develops spontaneously. Less frequently, it may be caused by trauma or asphyxia, and rarely, it occurs from a primary hemorrhagic disturbance or congenital cerebrovascular anomaly. Intracranial hemorrhage often involves the ventricles (intraventricular hemorrhage, IVH ) of premature infants delivered spontaneously without apparent trauma. The IVH in premature infants is usually not present at birth but may develop during the 1st week of life. Primary hemorrhagic disturbances and vascular malformations are rare and usually give rise to subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage. In utero hemorrhage associated with maternal idiopathic or, more often, fetal alloimmune thrombocytopenia may appear as severe cerebral hemorrhage or as a porencephalic cyst after resolution of a fetal cortical hemorrhage. Intracranial bleeding may be associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation, isoimmune thrombocytopenia, and neonatal vitamin K deficiency, especially in infants born to mothers receiving phenobarbital or phenytoin.

Epidemiology

The overall incidence of IVH has decreased over the past decades as a result of improved perinatal care, increased use of antenatal corticosteroids, surfactant to treat respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and possibly prophylactic indomethacin. It continues to be an important cause of morbidity in preterm infants, as approximately 30% of premature infants <1,500 g have IVH. The risk is inversely related to gestational age and birthweight; 7% of infants weighing 1,001-1,500 g have a severe IVH (grade III or IV), compared to 14% of infants weighing 751-1,000 g and 24% of infants ≤750 g. In 3% of infants <1,000 g, periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) develops.

Pathogenesis

The major neuropathologic lesions associated with very-low-birthweight (VLBW) infants are IVH and PVL. IVH in premature infants occurs in the gelatinous subependymal germinal matrix . This periventricular area is the site of origin for embryonal neurons and fetal glial cells, which migrate outwardly to the cortex. Immature blood vessels in this highly vascular region of the developing brain combined with poor tissue vascular support predispose premature infants to hemorrhage. The germinal matrix involutes as the infant approaches full-term gestation, and the tissue's vascular integrity improves; therefore IVH is much less common in the term infant. The cerebellum also contains a germinal matrix and is susceptible to hemorrhagic injury. Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction , previously known as grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage , often develops after a large IVH because of venous congestion. Predisposing factors for IVH include prematurity, RDS, hypoxia-ischemia, exaggerated fluctuations in cerebral blood flow (hypotensive injury, hypervolemia, hypertension), reperfusion injury of damaged vessels, reduced vascular integrity, increased venous pressure (pneumothorax, venous thrombus), or thrombocytopenia.

Understanding of the pathogenesis of PVL is evolving, and it appears to involve both intrauterine and postnatal events. A complex interaction exists between the development of the cerebral vasculature and the regulation of cerebral blood flow (both of which depend on gestational age), disturbances in the oligodendrocyte precursors required for myelination, and maternal/fetal infection and inflammation. Postnatal hypoxia or hypotension, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) with its resultant inflammation, and severe neonatal infection may all result in white matter injury. PVL is characterized by focal necrotic lesions in the periventricular white matter and/or more diffuse white matter damage. Destructive focal necrotic lesions resulting from massive cell death are less common in the modern era. Instead, diffuse injury leading to abnormal maturation of neurons and glia is more frequently seen. The risk for PVL increases in infants with severe IVH or ventriculomegaly. Infants with PVL are at higher risk of cerebral palsy because of injury to the corticospinal tracts that descend through the periventricular white matter.

Clinical Manifestations

Most infants with IVH , including some with moderate to severe hemorrhages, have no initial clinical signs (silent IVH). Some premature infants in whom severe IVH develops may have acute deterioration on the 2nd or 3rd day of life (catastrophic presentation). Hypotension, apnea, pallor, stupor or coma, seizures, decreased muscle tone, metabolic acidosis, shock, and decreased hematocrit (or failure of hematocrit to increase after transfusion) may be the first clinical indications. A saltatory progression may evolve over several hours to days and manifest as intermittent or progressive alterations of levels of consciousness, abnormalities of tone and movement, respiratory signs, and eventually other features of the acute catastrophic IVH. Rarely, IVH may manifest at birth or even prenatally; 50% of cases are diagnosed within the 1st day of life, and up to 75% within the 1st 3 days. A small percentage of infants have late hemorrhage, between days 14 and 30. IVH as a primary event is rare after the 1st mo of life.

PVL is usually clinically asymptomatic until the neurologic sequelae of white matter damage become apparent in later infancy as spasticity and/or motor deficits. PVL may be present at birth but usually occurs later, when the echodense phase is seen on ultrasound (3-10 days of life), followed by the typical echolucent/cystic phase (14-20 days).

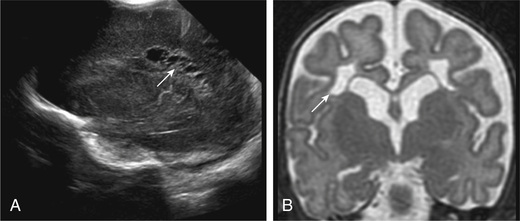

The severity of hemorrhage is defined by the location and degree of bleeding and ventricular dilation on cranial imaging. In a grade I hemorrhage, bleeding is isolated to the subependymal area. In grade II hemorrhage, there is bleeding within the ventricle without evidence of ventricular dilation. Grade III hemorrhage is IVH with ventricular dilation. In grade IV hemorrhage, there is intraventricular and parenchymal hemorrhage (Fig. 120.3 ). Another grading system describes 3 levels of increasing severity of IVH detected on ultrasound: In grade I, bleeding is confined to the germinal matrix–subependymal region or to <10% of the ventricle (approximately 35% of IVH cases); grade II is defined as intraventricular bleeding with 10–50% filling of the ventricle (40% of IVH cases); and in grade III , >50% of the ventricle is involved, with dilated ventricles (Fig. 120.3 ). Ventriculomegaly is defined as mild (0.5-1 cm dilation), moderate (1.0-1.5 cm dilation), or severe (>1.5 cm dilation).

Diagnosis

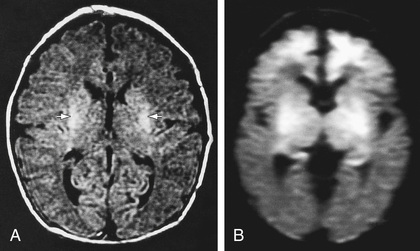

Intracranial hemorrhage is suspected on the basis of history, clinical manifestations, and knowledge of the birthweight-specific risks for IVH . Associated clinical signs of IVH are typically nonspecific or absent; therefore, it is recommended that premature infants <32 wk of gestation be evaluated with routine real-time cranial ultrasonography (US) through the anterior fontanel to screen for IVH. Infants <1,000 g are at highest risk and should undergo cranial US within the 1st 3-7 days of age, when approximately 75% of lesions will be detectable. US is the preferred imaging technique for screening because it is noninvasive, portable, reproducible, and sensitive and specific for detection of IVH. All at-risk infants should undergo follow-up US at 36-40 wk postmenstrual age to evaluate adequately for PVL, as cystic changes related to perinatal injury may not be visible for up to 1 mo. In one study, 29% of low-birthweight (LBW) infants who later experienced cerebral palsy did not have radiographic evidence of PVL until after 28 days of age. US also detects the precystic and cystic symmetric lesions of PVL and the asymmetric intraparenchymal echogenic lesions of cortical hemorrhagic infarction (Fig. 120.4 ). Cranial US may be useful in monitoring delayed development of cortical atrophy, porencephaly, and the severity, progression, or regression of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus.

Approximately 3–5% of VLBW infants develop posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH) . If the initial US findings are abnormal, additional interval US studies are indicated to monitor for the development of hydrocephalus and potential need for ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion.

IVH represents only 1 facet of brain injury in the term or preterm infant. MRI is a more sensitive tool for evaluation of white matter abnormalities and cerebellar injury and may be more predictive of adverse long-term outcome.

Prognosis

The degree of IVH and presence of PVL are strongly linked to survival and neurodevelopmental impairment (Tables 120.1 and 120.2 ). For infants with birthweight <1,000 g, the incidence of severe neurologic impairment (defined as Bayley Scales of Infant Development II mental developmental index <70, psychomotor development index <70, cerebral palsy, blindness, or deafness) after IVH is highest with grade IV hemorrhage and lower birthweight. PVL, cystic PVL, and progressive hydrocephalus requiring shunt insertion are each independently associated with a poorer prognosis (Table 120.3 ). Current data suggest that outcomes for infants with grade III/IV intraventricular hemorrhage may be improving, with rates of cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental impairment closer to 30–40% at age 2 yr.

Table 120.1

Short-Term Outcome of Germinal Matrix–Intraventricular Hemorrhage as a Function of Severity of Hemorrhage and Birthweight*

| SEVERITY OF HEMORRHAGE | DEATHS IN FIRST 14 DAYSc | PVD (SURVIVORS >14 DAYS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <750 g (n = 75) | 751-1500 g (n = 173) | <750 g (n = 56) | 751-1500 g (n = 165) | |

| Grade I | 3/24 (12) | 0/80 (0) | 1/21 (5) | 3/80 (4) |

| Grade II | 5/21 (24) | 1/44 (2) | 1/16 (6) | 6/43 (14) |

| Grade III | 6/19 (32) | 2/26 (8) | 10/13 (77) | 18/24 (75) |

| Grade III and apparent PHI | 5/11 (45) | 5/23 (22) | 5/6 (83) | 12/18 (66) |

* Values are n (%). Deaths occurring later in the neonatal period are not shown; the total mortality rates (early and late deaths) are approximately 50–100% greater for each grade of hemorrhage and birthweight than those shown in the table for early deaths alone.

PHI, Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction; PVD, progressive ventricular dilation.

Data from Murphy BP, Inder TE, Rooks V, Taylor GA, et al. Posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the premature infant: natural history and predictors of outcome, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 87:F37–F41, 2002.

Adapted from Inder TE, Perlman JM, Volpe JJ: Preterm intraventricular hemorrhage/posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. In Volpe's neurology of the newborn, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 24-15).

Table 120.2

| SEVERITY OF HEMORRHAGEb | INCIDENCE OF DEFINITE NEUROLOGIC SEQUELAE † (%) |

|---|---|

| Grade I | 15 |

| Grade II | 25 |

| Grade III | 50 |

| Grade III and apparent PVI | 75 |

* Data are derived from reports published since 2002 and include personal published and unpublished cases. Mean values (to nearest 5%); considerable variability among studies was apparent, especially for the severe lesions.

† Definite neurologic sequelae included principally cerebral palsy or mental retardation, or both.

PVI, Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction.

Adapted From Inder TE, Perlman JM, Volpe JJ: Preterm intraventricular hemorrhage/posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. In Volpe's neurology of the newborn, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 24-16).

Table 120.3

From Neil JJ, Volpe JJ: Encephalopathy of prematurity: clinical-neurological features, diagnosis, imaging, prognosis, therapy. In Volpe's neurology of the newborn, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 16-6).

Most infants with IVH and acute ventricular distention do not have PHH . Only 10–15% of LBW neonates with IVH develop PHH, which may initially present without clinical signs (enlarging head circumference, lethargy, a bulging fontanel or widely split sutures, apnea, and bradycardia). In infants in whom symptomatic hydrocephalus develops, clinical signs may be delayed 2-4 wk despite progressive ventricular distention and compression and thinning of the cerebral cortex. Many infants with PHH have spontaneous regression; only 3–5% of VLBW infants with PHH ultimately require shunt insertion. Those infants who require shunt insertion for PHH have lower cognitive and psychomotor performance at 18-22 mo.

Prevention

Improved perinatal care is imperative to minimize traumatic brain injury and decrease the risk of preterm delivery. The incidence of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage may be reduced by judicious management of cephalopelvic disproportion and operative (forceps, vacuum) delivery. Fetal or neonatal hemorrhage caused by maternal idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura or alloimmune thrombocytopenia may be reduced by maternal treatment with corticosteroids, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), fetal platelet transfusion, or cesarean birth. Meticulous care of the LBW infant's respiratory status and fluid-electrolyte management—avoidance of acidosis, hypocarbia, hypoxia, hypotension, wide fluctuations in neonatal blood pressure or PCO 2 (and secondarily fluctuation in cerebral perfusion pressure), and pneumothorax—are important factors that may affect the risk for development of IVH and PVL.

A single course of antenatal corticosteroids is recommended in pregnancies 24-37 wk of gestation that are at risk for preterm delivery. Antenatal steroids decrease the risk of death, grades III and IV intraventricular hemorrhage, and PVL in the neonate. The prophylactic administration of low-dose indomethacin (0.1 mg/kg/day for 3 days) to VLBW preterm infants reduces the incidence of severe IVH.

Treatment

Although no treatment is available for IVH that has occurred, it may be associated with other complications that require therapy. Seizures should be treated with anticonvulsant drugs. Anemia and coagulopathy require transfusion with packed red blood cells or fresh-frozen plasma. Shock and acidosis are treated with fluid resuscitation.

Insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is the preferred method to treat progressive and symptomatic PHH . Some infants require temporary cerebrospinal fluid diversion before a permanent shunt can be safety inserted. Diuretics and acetazolamide are not effective. Ventricular taps or reservoirs and externalized ventricular drains are potential temporizing interventions, although there is an associated risk of infection and puncture porencephaly from injury to the surrounding parenchyma. A ventriculosubgaleal shunt inserted from the ventricle into a surgically created subgaleal pocket provides a closed system for constant ventricular decompression without these additional risk factors. Decompression is regulated by the pressure gradient between the ventricle and the subgaleal pocket.

Bibliography

Alderliesten T, Lemmers PMA, Smarius JJM, et al. Cerebral oxygenation, extraction, and autoregulation in very preterm infants who develop peri-intraventricular hemorrhage. J Pediatr . 2013;162:698–704.

Armstrong-Wells J, Johnston SC, Wu YW, et al. Prevalence and predictors of perinatal hemorrhagic stroke: results from the kaiser pediatric stroke study. Pediatrics . 2009;123:823–828.

Back SA. Brain injury in the preterm infant: new horizons for pathogenesis and prevention. Pediat Neurol . 2015;53:185–192.

Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: mechanism of disease. Pediatr Res . 2010;67:1–8.

Bassan H, Limperopoulos C, Visconti K, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in survivors of periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics . 2007;120:785–792.

Bolisetty S, Dhawan A, Abdel-Latif M, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage and neurodevelopmental outcomes in extreme preterm infants. Pediatrics . 2014;133:55–62.

Broitman E, Ambalavanan N, Higgins RD, et al. Clinical data predict neurodevelopmental outcome better than head ultrasound in extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr . 2007;151:500–505.

Brouwer A, Groenendaal F, Van Haastert IL, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of preterm infants with severe intraventricular hemorrhage and therapy for post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. J Pediatr . 2008;152:648–654.

Chau V, Brant R, Poskitt KJ, et al. Postnatal infection is associated with widespread abnormalities of brain development in premature newborns. Pediatr Res . 2012;71:274–279.

De Vries LS, Groenendaal F, Liem KD, et al. Treatment thresholds for intervention in posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2018; 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314206 [Epub ahead of print].

Fowlie PW, Davis PG, McGuire W. Prophylactic intravenous indomethacin for preventing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2010;(7) [CD000174].

Gano D, Ho ML, Partridge JC, et al. Antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate is associated with reduced cerebellar hemorrhage in preterm newborns. J Pediatr . 2016;178:68–74.

Hintz SR, Barnes PD, Bulas D, et al. Neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental outcome in extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics . 2015;135:e32–e42.

Rooks VJ, Eaton JP, Ruess L, et al. Prevalence and evolution of intracranial hemorrhage in asymptomatic term infants. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2008;29:1082–1089.

Roze E, Van Braeckel KNJA, van der Veere CH, et al. Functional outcome at school age of preterm infants with periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics . 2009;123:1493–1500.

Sarkar S, Shankaran S, Barks J, et al. Outcome of preterm infants with transient cystic perventricular leukomalacia on serial cranial imaging up to term equivalent age. J Pediatr . 2018;195:59–65.

Sirgiovanni I, Avignone S, Groppo M, et al. Intracranial haemorrhage: an incidental finding at magnetic resonance imaging in a cohort of late preterm and term infants. Pediatr Radiol . 2014;44(3):289–296.

Vincer MJ, Allen AC, Joseph KS, et al. Increasing prevalence of cerebral palsy among very preterm infants: a population-based study. Pediatrics . 2006;118:e1621–e1626.

Whitby EH, Griffiths PD, Rutter S, et al. Frequency and natural history of subdural haemorrhages in babies and relation to obstetric factors. Lancet . 2003;362:846–851.

Whitelaw A, Lee-Kelland R. Repeated lumbar or ventricular punctures in newborns with intraventricular hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;(1) [CD000216].

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

Cameron W. Thomas, Stephanie L. Merhar

Hypoxemia , a decreased arterial concentration of oxygen, frequently results in hypoxia , or decreased oxygenation to cells or organs. Ischemia refers to blood flow to cells or organs that is inadequate to maintain physiologic function. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a leading cause of neonatal brain injury, morbidity, and mortality globally. In the developed world, incidence is estimated at 1-8 per 1,000 live births, and in the developing world, estimates are as high as 26 per 1,000.

Approximately 20–30% of infants with HIE (depending on the severity) die in the neonatal period, and 33–50% of survivors are left with permanent neurodevelopmental abnormalities (cerebral palsy, decreased IQ, learning/cognitive impairment). The greatest risk of adverse outcome is seen in infants with severe fetal acidosis (pH <6.7) (90% death/impairment) and a base deficit >25 mmol/L (72% mortality). Multiorgan failure and insult can occur (Table 120.4 ).

Table 120.4

Etiology

Most neonatal encephalopathy and seizure, in the absence of major congenital malformations or metabolic or genetic syndromes, appear to be caused by perinatal events. Brain MRI or autopsy findings in full-term neonates with encephalopathy demonstrate that 80% have acute injuries, <1% have prenatal injuries, and 3% have non–hypoxic-ischemic diagnoses. Fetal hypoxia may be caused by various disorders in the mother, including: (1) inadequate oxygenation of maternal blood from hypoventilation during anesthesia, cyanotic heart disease, respiratory failure, or carbon monoxide poisoning; (2) low maternal blood pressure from acute blood loss, spinal anesthesia, or compression of the vena cava and aorta by the gravid uterus; (3) inadequate relaxation of the uterus to permit placental filling as a result of uterine tetany caused by the administration of excessive oxytocin; (4) premature separation of the placenta; (5) impedance to the circulation of blood through the umbilical cord as a result of compression or knotting of the cord; and (6) placental insufficiency from maternal infections, exposures, diabetes, toxemia or postmaturity.

Placental insufficiency often remains undetected on clinical assessment. Intrauterine growth restriction may develop in chronically hypoxic fetuses without the traditional signs of fetal distress. Doppler umbilical waveform velocimetry (demonstrating increased fetal vascular resistance) and cordocentesis (demonstrating fetal hypoxia and lactic acidosis) identify a chronically hypoxic infant (see Chapter 115 ). Uterine contractions may further reduce umbilical oxygenation, depressing the fetal cardiovascular system and CNS and resulting in low Apgar scores and respiratory depression at birth.

After birth, hypoxia may be caused by (1) failure of oxygenation as a result of severe forms of cyanotic congenital heart disease or severe pulmonary disease; (2) severe anemia (severe hemorrhage, hemolytic disease); (3) shock severe enough to interfere with the transport of oxygen to vital organs from overwhelming sepsis, massive blood loss, and intracranial or adrenal hemorrhage; or (4) failure to breathe after birth because of in utero CNS injury or drug-induced suppression.

Pathophysiology and Pathology

The topography of cerebral injury typically correlates with areas of decreased cerebral blood flow and areas of relatively higher metabolic demand, although regional vulnerabilities are impacted by gestational age and severity of insult (Table 120.5 ). After an episode of hypoxia and ischemia, anaerobic metabolism occurs and generates increased amounts of lactate and inorganic phosphates. Excitatory and toxic amino acids, particularly glutamate, accumulate in the damaged tissue. prompting overactivation of N -methyl-D -aspartate (NMDA), amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA), and kainate receptors. This receptor overactivation increases cellular permeability to sodium and calcium ions. Because of inadequate intracellular energy, normal sodium and calcium homeostasis is lost, and intracellular accumulation of these ions results in cytotoxic edema and neuronal death. Intracellular calcium accumulation may also result in apoptotic cell death. Concurrent with the excitotoxic cascade, there is also increased production of damaging free radicals and nitric oxide in these tissues. The initial circulatory response of the fetus is increased shunting through the ductus venosus, ductus arteriosus, and foramen ovale, with transient maintenance of perfusion of the brain, heart, and adrenals in preference to the lungs, liver, kidneys, and intestine. Thus, serum laboratory evidence of injury to these organs may be present in more severe cases.

Table 120.5

Topography of Brain Injury in Term Infants With Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy and Clinical Correlates

| AREA OF INJURY | LOCATION OF INJURY | CLINICAL CORRELATES | LONG-TERM SEQUELAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective neuronal necrosis | Entire neuraxis, deep cortical area, brainstem and pontosubicular |

Stupor or coma Seizures Hypotonia Oculomotor abnormalities Suck/swallow abnormalities |

Cognitive delay Cerebral palsy Dystonia Seizure disorder Ataxia Bulbar and pseudobulbar palsy |

| Parasagittal injury |

Cortex and subcortical white matter Parasagittal regions, especially posterior |

Proximal-limb weakness Upper extremities affected > lower extremities |

Spastic quadriparesis Cognitive delay Visual and auditory processing difficulty |

| Focal ischemic necrosis |

Cortex and subcortical white matter Vascular injury (usually middle cerebral artery distribution) |

Unilateral findings Seizures common and typically focal |

Hemiparesis Seizures Cognitive delays |

| Periventricular injury | Injury to motor tracts, especially lower extremity |

Bilateral and symmetric weakness in lower extremities More common in preterm infants |

Spastic diplegia |

Adapted from Volpe JJ, editor: Neurology of the newborn , ed 4, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders.

The pathology of hypoxia-ischemia outside the CNS depends on the affected organ and the severity of the injury. Early congestion, fluid leak from increased capillary permeability, and endothelial cell swelling may lead to signs of coagulation necrosis and cell death. Congestion and petechiae are seen in the pericardium, pleura, thymus, heart, adrenals, and meninges. Prolonged intrauterine hypoxia may result in inadequate perfusion of the periventricular white matter, resulting in PVL. Pulmonary arteriole smooth muscle hyperplasia may develop, which predisposes the infant to pulmonary hypertension (see Chapter 122.9 ). If fetal distress produces gasping, amniotic fluid contents (meconium, squames, lanugo) may be aspirated into the trachea or lungs with subsequent complications, including pulmonary hypertension and pneumothoraces.

Clinical Manifestations

Intrauterine growth restriction with increased vascular resistance may be an indication of chronic fetal hypoxia before the peripartum period. During labor, the fetal heart rate slows and beat-to-beat variability declines. Continuous heart rate recording may reveal a variable or late deceleration pattern (see Chapter 115 , Fig. 115.4 ). Particularly in infants near term, these signs should lead to the administration of high concentrations of oxygen to the mother and consideration of immediate delivery to avoid fetal death and CNS damage.

At delivery, the presence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid indicates that fetal distress may have occurred. At birth, affected infants may have neurologic impairment and may fail to breathe spontaneously. Pallor, cyanosis, apnea, a slow heart rate, and unresponsiveness to stimulation are also nonspecific initial signs of potential HIE. During the ensuing hours, infants may be hypotonic, may change from a hypotonic to a hypertonic state, or their tone may appear normal (Tables 120.6 and 120.7 ). Cerebral edema may develop during the next 24 hr and result in profound brainstem depression. During this time, seizure activity may occur; it may be severe and refractory to typical doses of anticonvulsants. Although most often a result of the HIE, seizures in asphyxiated newborns may also be caused by vascular events (hemorrhage, arterial ischemic stroke, or sinus venous thrombosis), metabolic derangements (hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia), CNS infection, and cerebral dysgenesis or genetic disorders (nonketotic hyperglycinemia, vitamin-dependent epilepsies, channelopathies). Conditions that result in neuromuscular weakness and poor respiratory effort may also result secondarily in neonatal hypoxic brain injury and seizure. Such conditions might include congenital myopathies, congenital myotonic dystrophy, or spinal muscular atrophy.

Table 120.6

Poor Predictive Variables for Death/Disability After Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

Table 120.7

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy in Term Infants

| SIGNS | STAGE 1 | STAGE 2 | STAGE 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of consciousness | Hyperalert | Lethargic | Stuporous, coma |

| Muscle tone | Normal | Hypotonic | Flaccid |

| Posture | Normal | Flexion | Decerebrate |

| Tendon reflexes/clonus | Hyperactive | Hyperactive | Absent |

| Myoclonus | Present | Present | Absent |

| Moro reflex | Strong | Weak | Absent |

| Pupils | Mydriasis | Miosis | Unequal, poor light reflex |

| Seizures | None | Common | Decerebration |

| Electroencephalographic findings | Normal | Low voltage changing to seizure activity | Burst suppression to isoelectric |

| Duration | <24 hr if progresses; otherwise, may remain normal | 24 hr to 14 days | Days to weeks |

| Outcome | Good | Variable | Death, severe deficits |

Adapted from Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS: Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress: a clinical and electroencephalographic study, Arch Neurol 33:696–705, 1976.Copyright 1976, American Medical Association.

In addition to CNS dysfunction, systemic organ dysfunction is noted in up to 80% of affected neonates. Myocardial dysfunction and cardiogenic shock, persistent pulmonary hypertension, RDS, gastrointestinal perforation, and acute kidney and liver injury are associated with perinatal asphyxia secondary to inadequate perfusion (see Table 120.4 ).

The severity of neonatal encephalopathy depends on the duration and timing of injury. A clinical grading score first proposed by Sarnat continues to be a useful tool. Symptoms develop over days, making it important to perform serial neurologic examinations (see Tables 120.6 and 120.7 ). During the initial hours after an insult, infants have a depressed level of consciousness. Periodic breathing with apnea or bradycardia is present, but cranial nerve functions are often spared, with intact pupillary response and spontaneous eye movement. Seizures are common with extensive injury. Hypotonia is also common as an early manifestation of HIE, but it should be distinguished from other causes by history and serial examination.

Diagnosis

MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality for detecting hypoxic brain injury in the neonate. Although such injury can be detected at various times and with varying pulse sequences, diffusion-weighted sequences obtained in the 1st 3-5 days following a presumed sentinel event are optimal for identifying acute injury. (Figs. 120.5 to 120.8 and Table 120.8 ). Where MRI is unavailable or prevented by clinical instability, CT scans may be helpful in ruling out focal hemorrhagic lesions or large arterial ischemic strokes. Loss of gray-white differentiation and injury to the basal ganglia in more severe HIE can be detected on CT by experienced readers, but CT often misses subtler forms of neonatal hypoxic brain injury. US has limited utility in evaluation of hypoxic injury in the term infant, but it too can be useful for excluding hemorrhagic lesions. Because of factors of size and clinical stability, US is the initial preferred (and sometimes only feasible) modality in evaluation of the preterm infant.

Table 120.8

Major Aspects of MRI in Diagnosis of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy in the Term Infant

FLAIR, Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T1W and T2W, T1- and T2-weighted images.

From Volpe JJ, editor: Neurology of the newborn, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Elsevier (Table 9-16).

Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography (aEEG) may help to determine which infants are at highest risk for developmental sequelae of neonatal brain injury (Tables 120.9 and 120.10 ). The aEEG background voltage ranges, signal patterns, and rates of normalization, as assessed at various points in the 1st hours and days of life, can provide valuable prognostic information, with positive predictive value of 85% and negative predictive value of 91–96% for infants who will have adverse neurodevelopmental outcome. Unfortunately, even with recent improvements in technology, aEEG still has difficulty detecting seizures, particularly those that are brief or originate far from the electrodes. Sensitivity of aEEG for seizure detection, when used by a typical reader, is <50%. For this reason, conventional EEG montage with concurrent video of the patient are preferred for seizure monitoring.

Table 120.9

Value of Electroencephalography in Assessment of Asphyxiated Term Infants

aEEG, Amplitude-integrated encephalography; BSP, burst-suppression pattern; CLV, continuous low voltage; FT, flat trace.

From Inder TE, Volpe JJ: Hypoxic-ischemic injury in the term infant: clinical-neurological features, diagnosis, imaging, prognosis, therapy. In Volpe's neurology of the newborn, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 20-28).

Table 120.10

Electroencephalographic Patterns of Prognostic Significance in Asphyxiated Term Infants*

| ASSOCIATED WITH FAVORABLE OUTCOME |

| ASSOCIATED WITH UNFAVORABLE OUTCOME |

* Associations with favorable or unfavorable outcome are generally ≥90%, but the clinical context must be considered.

From Inder TE, Volpe JJ: Hypoxic-ischemic injury in the term infant: clinical-neurological features, diagnosis, imaging, prognosis, therapy. In Volpe's neurology of the newborn, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 20-26).

Treatment

Therapeutic hypothermia , whether head cooling or systemic cooling (by servo-control to a core rectal or esophageal temperature of 33.5°C [92.3°F] within the 1st 6 hr after birth and maintained for 72 hr), has been shown in various trials to reduce mortality and major neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 mo of age. Infants treated with systemic hypothermia have a lower incidence of cortical neuronal injury on MRI, suggesting systemic hypothermia may result in more uniform cooling of the brain and deeper CNS structures than selective head cooling. The therapeutic effect of hypothermia likely results from decreased secondary neuronal injury achieved by reducing rates of apoptosis and production of mediators known to be neurotoxic, including extracellular glutamate, free radicals, nitric oxide, and lactate. There is also benefit in seizure reduction. The therapeutic benefit of hypothermia noted at 18-22 mo of age is maintained later in childhood. Once established, hypothermia may not alter the prognostic findings on MRI.

Numerous studies seeking ways to extend the benefits of therapeutic hypothermia have been attempted. Assessment of deeper or longer cooling failed to show benefit in short-term outcomes, although longer-term developmental outcomes of that trial are not yet published. Investigations into extending the therapeutic time window of hypothermia initiation beyond 6 hr or offering hypothermia to preterm infants are ongoing.

In addition to extending the benefit of therapeutic hypothermia, there is great interest in augmenting its benefit through other means. High-dose erythropoietin given as an adjunct to therapeutic hypothermia shows some promise in decreasing MRI indicators of brain injury and short-term motor outcomes. Further study as well as longitudinal follow-up of the study cohort is warranted to confirm these findings.

Complications of induced hypothermia include thrombocytopenia (usually without bleeding), reduced heart rate, and subcutaneous fat necrosis (sometimes with associated hypercalcemia) as well as the potential for overcooling and the cold injury syndrome. The latter is usually avoided with a servo-controlled cooling system. Therapeutic hypothermia may theoretically alter drug metabolism, prolong the QT interval, and affect the interpretation of blood gases. In clinical practice, these concerns have not been observed.

For treating seizures associated with HIE, phenobarbital , the historical first-line drug for neonatal seizures, continues to be used in many instances. It is typically given by intravenous loading dose (20 mg/kg). Additional doses of 5-10 mg/kg (up to 40-50 mg/kg total) may be needed. Phenobarbital levels should be monitored 24 hr after the loading dose has been given and maintenance therapy (5 mg/kg/24 hr) begun. Therapeutic phenobarbital levels are 20-40 µg/mL. Animal models demonstrate decreased neurodevelopmental impact of hypoxic brain injury in animals that received a high-dose prophylactic injection of phenobarbital before onset of therapeutic hypothermia. Whether this benefit translates to humans is controversial.

For refractory seizures, there is a high degree of variability regarding choice of 2nd agent. Historically, phenytoin (20 mg/kg loading dose) or lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg) have been preferred, currently the use of levetiracetam is preferred (at times even as a first-line agent) as the most used second-line agent. Early reports of administration of levetiracetam in the neonate used low doses, but subsequent pharmacokinetic data suggest that due to the higher volume of distribution created by higher relative body water content in neonates, loading doses should be higher than in older children or adults. Suggested appropriate loading doses may be closer to 60 mg/kg. In addition to levetiracetam and phenytoin, other second- or third-line agents commonly used include midazolam, topiramate, and lidocaine. Pyridoxine should also be attempted, particularly in ongoing refractory seizures with highly abnormal EEG background.

Status epilepticus, multifocal seizures, and multiple anticonvulsant medications during therapeutic hypothermia are associated with a poor prognosis.

Additional therapy for infants with HIE includes supportive care directed at management of organ system dysfunction. Hyperthermia has been associated with impaired neurodevelopment and should be prevented, particularly in the interval between initial resuscitation and initiation of hypothermia. Careful attention to ventilatory status and adequate oxygenation, blood pressure, hemodynamic status, acid-base balance, and possible infection is important. Secondary hypoxia or hypotension from complications of HIE must be prevented. Aggressive treatment of seizures is critical and may necessitate continuous EEG monitoring. In addition, hyperoxia, hypocarbia, and hypoglycemia are associated with poor outcomes, so careful attention to resuscitation, ventilation, and blood glucose homeostasis is essential.

Prognosis

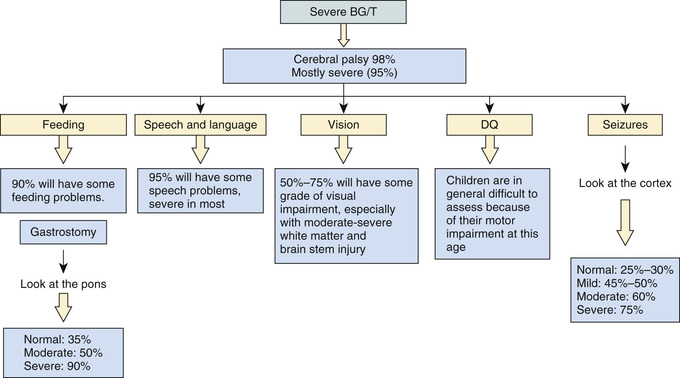

The outcome of HIE, which correlates with the timing and severity of the insult, ranges from complete recovery to death. The prognosis varies depending on the severity of the insult and the treatment. Infants with initial cord or initial blood pH <6.7 have a 90% risk for death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 mo of age. In addition, infants with Apgar scores of 0-3 at 5 min, high base deficit (>20-25 mmol/L), decerebrate posture, severe basal ganglia/thalamic (BG/T) lesions (Fig. 120.9 ; see also Fig. 120.6 ), persistence of severe HIE by clinical examination at 72 hr, and lack of spontaneous activity are also at increased risk for death or impairment. These predictor variables can be combined to determine a score that helps with prognosis (see Table 120.6 ). Infants with the highest risk are likely to die or have severe disability despite aggressive treatment, including hypothermia. Those with intermediate scores are likely to benefit from treatment. In general, severe encephalopathy, characterized by flaccid coma, apnea, absence of oculocephalic reflexes, and refractory seizures, is associated with a poor prognosis (see Table 120.7 ). Apgar scores alone can also be associated with subsequent risk of neurodevelopmental impairment. At 10 min, each point decrease in Apgar score increases odds of death or disability by 45%. Death or disability occurs in 76–82% of infants with Apgar scores of 0-2 at 10 min. Absence of spontaneous respirations at 20 min of age and persistence of abnormal neurologic signs at 2 wk of age also predict death or severe cognitive and motor deficits.

The combined use of early conventional EEG or aEEG and MRI offers additional insight in predicting outcome in term infants with HIE (see Table 120.10 ). EEG or aEEG background characteristics such as pattern, voltage, reactivity, state change, and evolution after acute injury are important predictors of outcome. MRI markers include location of injury, identification of injury by certain pulse sequences, measurement of diffusivity and/or fractional anisotropy, and presence of abnormal metabolite ratios on MR spectroscopy, and all have shown correlation with outcome. There is also growing interest in quantitative measures (volumetric analysis, diffusion tensor imaging) of MRI as potential predictors of outcome. Severe BG/T lesions with abnormal signal in the posterior limb of the internal capsule is highly predictive of the poorest cognitive and motor prognosis (see Fig. 120.9 ). Normal MRI and EEG findings are associated with a good recovery.

Microcephaly and poor head growth during the 1st year of life also correlate with injury to the basal ganglia and white matter and adverse developmental outcome at 12 mo. All survivors of moderate to severe encephalopathy require comprehensive high-risk medical and developmental follow-up. Early identification of neurodevelopmental problems allows prompt referral for developmental, rehabilitative, and neurologic early intervention services so that the best possible outcomes can be achieved.

Brain death after neonatal HIE is diagnosed from the clinical findings of coma unresponsive to pain, auditory, or visual stimulation; apnea with PCO 2 rising from 40 to >60 mm Hg without ventilatory support; and absence of brainstem reflexes (pupillary, oculocephalic, oculovestibular, corneal, gag, sucking) (see Chapter 86 ). These findings must occur in the absence of hypothermia, hypotension, and elevations of depressant drugs (phenobarbital), which may take days to weeks to be metabolized and cleared completely from the blood. An absence of cerebral blood flow on radionuclide scans and of electrical activity on EEG (electrocerebral silence) is inconsistently observed in clinically brain-dead neonatal infants. Persistence of the clinical criteria for 24 hr in term infants predicts brain death in most asphyxiated newborns. There is no agreement on brain death criteria in preterm infants. Because of inconsistencies and difficulties in applying standard criteria, no universal agreement has been reached regarding the definition of neonatal brain death. Consideration of withdrawal of life support should include discussions with the family, the healthcare team, and, if there is disagreement, an ethics committee. The best interest of the infant involves judgments about the benefits and harm of continuing therapy or avoiding ongoing futile therapy.

Bibliography

Ahmad KA, Desai SJ, Bennett MM, et al. Changing antiepileptic drug use for seizures in US neonatal intensive care units from 2005 to 2014. J Perinatol . 2017;37:296–300.

Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Predicting outcomes of neonates diagnosed with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics . 2006;118:2084–2093.

Avasiloaiei A, Dimitriu C, Moscalu M, et al. High-dose phenobarbital or erythropoietin for the treatment of perinatal asphyxia in term newborns. Pediatr Int . 2013;55:589–593.

Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edward AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med . 2009;361:1349–1358.

Barks JD, Liu YQ, Shangguan Y, et al. Phenobarbital augments hypothermic neuroprotection. Pediatr Res . 2010;67:532–537.

Chau V, Poskitt KJ, Sargent MA, et al. Comparison of computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans on the third day of life in term newborns with neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics . 2009;123:319–326.

Corbo ET, Bartnik-Olson BL, Machado S, et al. The effect of whole-body cooling on brain metabolism following perinatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. Pediatr Res . 2012;71:85–92.

Davis AS, Hintz SR, Van Meurs KP, et al. Seizures in extremely low birth weight infants are associated with adverse outcome. J Pediatr . 2010;157:720–725.

De Vries LS, Groenendaal F. Patterns of neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. Neuroradiology . 2010;52:555–566.

Douglas-Escobar M, Weiss MD. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review for the clinician. JAMA Pediatr . 2015;169:397–403.

Glass HC, Nash KB, Bonifacio SL, et al. Seizures and magnetic resonance imaging-detected brain injury in newborns cooled for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2011;159:731–735.

Guillet R, Edwards AD, Thoresen M, et al. Seven- to eight-year follow-up of the CoolCap trial of head cooling for neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatr Res . 2012;71:205–209.

Hagberg H, Edwards AD. Groenendall F: perinatal brain damage: the term infant. Neurobiol Dis . 2016;92:102–112.

Hagberg H, Mallard C, Rousset CI, et al. Mitochondria: hub of injury responses in the developing brain. Lancet Neurol . 2014;13:217–232.

Kapadia VS, Chalak LF, DuPont TL, et al. Perinatal asphyxia with hyperoxemia within the first hour of life is associated with moderate to severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2013;163:949–954.

Laptook AR, Shankaran S, Ambalavanan N, et al. Outcome of term infants using apgar scores at 10 minutes following hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics . 2009;124:1619–1626.

Laptook AR, Shankaran S, Tyson JE, et al. Effect of therapeutic hypothermia initiated after 6 hours of age on death or disability among newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;318(16):1550–1560.

Maitre NL, Smolinsky C, Slaughter JC, et al. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes after exposure to phenobarbital and levetiracetam for the treatment of neonatal seizures. J Perinatol . 2013;33:841–846.

Martinez-Biarge M, Diez-Sebastian J, Kapellou O, et al. Predicting motor outcome and death in term hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neurology . 2011;76:2055–2061.

Merhar SL, Schibler KR, Sherwin CM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of levetiracetam in neonates with seizures. J Pediatr . 2011;159:152–154 e153.

Murray DM, Boylan GB, Ryan CA, et al. Early EEG findings in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy predict outcomes at 2 years. Pediatrics . 2009;124:e459–e467.

Nakagawa TA, Ashwal S, Mathur M, et al. Clinical report. Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 task force recommendations. Pediatrics . 2011;128(3):e720–e740.

Natarajan G, Shankaran S, Saha S, et al. Antecedents and outcomes of abnormal cranial imaging in moderately preterm infants. J Pediatr . 2018 [Epub ahead of print; PMID] 29395186.

Pappas A, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, et al. Hypocarbia and adverse outcome in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2011;158:752–758.

Rennie JM, Chorley G, Boylan GB, et al. Non-expert use of the cerebral function monitor for neonatal seizure detection. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2004;F37–F40.

Sabir H, Jary S, Tooley J, et al. Increased inspired oxygen in the first hours of life is associated with adverse outcome in newborns treated for perinatal asphyxia with therapeutic hypothermia. J Pediatr . 2012;161:409–416.

Sarkar S, Barks JD, Bapuraj JR, et al. Does phenobarbital improve the effectiveness of therapeutic hypothermia in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy? J Perinatol . 2012;32:15–20.

Selewski DT, Jordan BK, Askenzai DJ, et al. Acute kidney injury in asphyxiated newborns treated with therapeutic hypothermia. J Pediatr . 2013;162:725–729.

Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkran RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med . 2005;353:1574–1584.

Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2014;312:2629–2639.

Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Tyson JE, et al. Evolution of encephalopathy during whole body hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2012;160:567–572.

Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, et al. Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med . 2012;366(22):2085–2092.

Shellhaas RA, Chang T, Tsuchida T, et al. The American clinical neurophysiology Society's guideline on continuous electroencephalography monitoring in neonates. J Clin Neurophysiol . 2011;28:611–617.

Shellhaas RA, Soaita AI, Clancy RR. Sensitivity of amplitude-integrated electroencephalography for neonatal seizure detection. Pediatrics . 2007;120:770–777.

Skranes JH, Løhaugen G, Schumacher EM, et al. Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography improves the identification of infants with encephalopathy for therapeutic hypothermia and predicts neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. J Pediatr . 2017;187:34–42.

Srinivasakumar P, Zampel J, Wallendorf M, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: electrographic seizures and magnetic resonance imaging evidence of injury. J Pediatr . 2013;163:465–470.

Strohm B, Hobson A, Brocklehurst P, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis after moderate therapeutic hypothermia in neonates. Pediatrics . 2011;128:e450–e452.

Tam EWY, Haeusslein LA, Bonifacio SL, et al. Hypoglycemia is associated with increased risk for brain injury and adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates at risk for encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2012;161:88–93.

Thoresen M, Hellstrom-Westas L, Liu X, et al. Effect of hypothermia on amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram in infants with asphyxia. Pediatrics . 2010;126(1):e131–e139.

Venkatesan C, Young S, Schapiro M, et al. Levetiracetam for the treatment of seizures in neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Child Neurol . 2017;32:210–214.

Walsh BH, Neil J, Morey J, et al. The frequency and severity of magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in infants with mild neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr . 2017;187:26–33.

Weeke LC, Groenendaal F, Mudigonda K, et al. A novel magnetic resonance imaging score predicts neurodevelopmental outcome after perinatal asphyxia and therapeutic hypothermia. J Pediatr . 2018;192:33–40.

Weeke LC, Groenendaal F, Toet MC, et al. The aetiology of neonatal seizures and the diagnostic contribution of neonatal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2015;57:248–256.

Wu YW, Mathur AM, Chang T, et al. High-dose erythropoietin and hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a phase II trial. Pediatrics . 2016;137.

Spine and Spinal Cord

Cameron W. Thomas, Stephanie L. Merhar

See also Chapter 729 .

Injury to the spine/spinal cord during birth is rare but can be devastating. Strong traction exerted when the spine is hyperextended or when the direction of pull is lateral, or forceful longitudinal traction on the trunk while the head is still firmly engaged in the pelvis, especially when combined with flexion and torsion of the vertical axis, may produce fracture and separation of the vertebrae. Such injuries are most likely to occur when difficulty is encountered in delivering the shoulders in cephalic presentations and the head in breech presentations. The injury occurs most often at the level of the 4th cervical vertebra with cephalic presentations and the lower cervical–upper thoracic vertebrae with breech presentations. Transection of the cord may occur with or without vertebral fractures; hemorrhage and edema may produce neurologic signs that are indistinguishable from those of transection, except that they may not be permanent. Areflexia, loss of sensation, and complete paralysis of voluntary motion occur below the level of injury, although the persistence of a withdrawal reflex mediated through spinal centers distal to the area of injury is frequently misinterpreted as representing voluntary motion.

If the injury is severe, the infant, who from birth may be in poor condition because of respiratory depression, shock, or hypothermia, may deteriorate rapidly to death within several hours before any neurologic signs are obvious. Alternatively, the course may be protracted, with symptoms and signs appearing at birth or later in the 1st wk; Horner syndrome, immobility, flaccidity, and associated brachial plexus injuries may not be recognized for several days. Constipation may also be present. Some infants survive for prolonged periods, their initial flaccidity, immobility, and areflexia being replaced after several weeks or months by rigid flexion of the extremities, increased muscle tone, and spasms. Apnea on day 1 and poor motor recovery by 3 mo are poor prognostic signs.

The differential diagnosis of neonatal spine/spinal cord injury includes amyotonia congenita and myelodysplasia associated with spina bifida occulta, spinal muscular atrophy (type 0), spinal vascular malformations (e.g., arteriovenous malformation causing hemorrhage or stroke), and congenital structural anomalies (syringomyelia, hemangioblastoma). US or MRI confirms the diagnosis. Treatment of the survivors is supportive, including home ventilation; patients often remain permanently disabled. When a fracture or dislocation is causing spinal compression, the prognosis is related to the time elapsed before the compression is relieved.

Bibliography

Coulter DM, Zhou H, Rorke-Adams LB. Catastrophic intrauterine spinal cord injury caused by an arteriovenous malformation. J Perinatol . 2007;27:186–189.

D'Amico A, Mercuri E, Tiziano FD, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2011;6:71.

Mercuri E, Bertini E, Iannaccone ST. Childhood spinal muscular atrophy: controversies and challenges. Lancet Neurol . 2012;11:443–452.

Mills JF, Dargaville PA, Coleman LT, et al. Upper cervical spinal cord injury in neonates: the use of magnetic resonance imaging. J Pediatr . 2001;138:105–108.

Peripheral Nerve Injuries

Cameron W. Thomas, Stephanie L. Merhar

See also Chapter 731 .

Brachial Palsy

Brachial plexus injury is a common problem, with an incidence of 0.6-4.6 per 1,000 live births. Injury to the brachial plexus may cause paralysis of the upper part of the arm with or without paralysis of the forearm or hand or, more often, paralysis of the entire arm. These injuries occur in macrosomic infants and when lateral traction is exerted on the head and neck during delivery of the shoulder in a vertex presentation, when the arms are extended over the head in a breech presentation, or when excessive traction is placed on the shoulders. Approximately 45% of brachial plexus injuries are associated with shoulder dystocia.

In Erb-Duchenne paralysis the injury is limited to the 5th and 6th cervical nerves. The infant loses the power to abduct the arm from the shoulder, rotate the arm externally, and supinate the forearm. The characteristic position consists of adduction and internal rotation of the arm with pronation of the forearm. Power to extend the forearm is retained, but the biceps reflex is absent; the Moro reflex is absent on the affected side (Fig. 120.10 ). The outer aspect of the arm may have some sensory impairment. Power in the forearm and hand grasps is preserved unless the lower part of the plexus is also injured; the presence of hand grasp is a favorable prognostic sign. When the injury includes the phrenic nerve, alteration in diaphragmatic excursion may be observed with US, fluoroscopy, or as asymmetric elevation of the diaphragm on chest radiograph.

Klumpke paralysis is a rare form of brachial palsy in which injury to the 7th and 8th cervical nerves and the 1st thoracic nerve produces a paralyzed hand and ipsilateral ptosis and miosis (Horner syndrome ) if the sympathetic fibers of the 1st thoracic root are also injured. Mild cases may not be detected immediately after birth. Differentiation must be made from cerebral injury; from fracture, dislocation, or epiphyseal separation of the humerus; and from fracture of the clavicle. MRI demonstrates nerve root rupture or avulsion.

Most patients have full recovery. If the paralysis was a result of edema and hemorrhage around the nerve fibers, function should return within a few months; if it resulted from laceration, permanent damage may result. Involvement of the deltoid is usually the most serious problem and may result in shoulder drop secondary to muscle atrophy. In general, paralysis of the upper part of the arm has a better prognosis than paralysis of the lower part.

Treatment consists of initial conservative management with monthly follow-up and a decision for surgical intervention by 3 mo if function has not improved. Partial immobilization and appropriate positioning are used to prevent the development of contractures. In upper arm paralysis, the arm should be abducted 90 degrees with external rotation at the shoulder, full supination of the forearm, and slight extension at the wrist with the palm turned toward the face. This position may be achieved with a brace or splint during the 1st 1-2 wk. Immobilization should be intermittent throughout the day while the infant is asleep and between feedings. In lower arm or hand paralysis, the wrist should be splinted in a neutral position and padding placed in the fist. When the entire arm is paralyzed, the same treatment principles should be followed. Gentle massage and range-of-motion exercises may be started by 7-10 days of age. Infants should be closely monitored with active and passive corrective exercises. If the paralysis persists without improvement for 3 mo, neuroplasty, neurolysis, end-to-end anastomosis, and nerve grafting offer hope for partial recovery.

The type of treatment and the prognosis depend on the mechanism of injury and the number of nerve roots involved. The mildest injury to a peripheral nerve (neurapraxia ) is caused by edema and heals spontaneously within a few weeks. Axonotmesis is more severe and is a consequence of nerve fiber disruption with an intact myelin sheath; function usually returns in a few months. Total disruption of nerves (neurotmesis ) or root avulsion is the most severe, especially if it involves C5-T1; microsurgical repair may be indicated. Fortunately, most (75%) injuries are at the root level C5-C6, involve neurapraxia and axonotmesis, and should heal spontaneously. Botulism toxin may be used to treat biceps-triceps co-contractions.

Phrenic Nerve Paralysis

Phrenic nerve injury (3rd, 4th, 5th cervical nerves) with diaphragmatic paralysis must be considered when cyanosis and irregular and labored respirations develop. Such injuries, usually unilateral, are associated with ipsilateral upper brachial plexus palsies in 75% of cases. Because breathing is thoracic in type, the abdomen does not bulge with inspiration. Breath sounds are diminished on the affected side. The thrust of the diaphragm, which may often be felt just under the costal margin on the normal side, is absent on the affected side. The diagnosis is established by US or fluoroscopic examination, which reveals elevation of the diaphragm on the paralyzed side and seesaw movements of the 2 sides of the diaphragm during respiration. It may also be apparent on chest or abdominal radiograph.

Infants with phrenic nerve injury should be placed on the involved side and given oxygen if necessary. Some may benefit from pressure introduced by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to expand the paralyzed hemidiaphragm. In extreme cases, mechanical ventilation cannot be avoided. Initially, intravenous feedings may be needed; later, progressive gavage or oral feeding may be started, depending on the infant's condition. Pulmonary infections are a serious complication. If the infant fails to demonstrate spontaneous recovery in 1-2 mo, surgical plication of the diaphragm may be indicated.

Facial Nerve Palsy

Facial palsy is usually a peripheral paralysis that results from pressure over the facial nerve in utero, during labor, or from forceps use during delivery. Rarely, it may result from nuclear agenesis of the facial nerve.

Peripheral facial paralysis is flaccid and, when complete, involves the entire side of the face, including the forehead. When the infant cries, movement occurs only on the nonparalyzed side of the face, and the mouth is drawn to that side. On the affected side the forehead is smooth, the eye cannot be closed, the nasolabial fold is absent, and the corner of the mouth droops. Central facial paralysis spares the forehead (e.g., forehead wrinkles will still be apparent on the affected side) because the nucleus that innervates the upper face has overlapping dual innervation by corticobulbar fibers originating in bilateral cerebral hemispheres. The infant with central facial paralysis usually has other manifestations of intracranial injury, most often 6th nerve palsy from the proximity of the 6th and 7th cranial nerve nuclei in the brainstem. Prognosis depends on whether the nerve was injured by pressure or the nerve fibers were torn; improvement occurs within a few weeks in the former case. Care of the exposed eye is essential. Neuroplasty may be indicated when the paralysis is persistent. Facial palsy may be confused with absence of the depressor muscles of the mouth, which is a benign problem or with variants of Möbius syndrome.

Other peripheral nerves are seldom injured in utero or at birth except when they are involved in fractures or hemorrhage.

Bibliography

Bauer AS, Lucas JF, Heyrani N, et al. Ultrasound screening for posterior shoulder dislocation in infants with persistent brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2017;99(9):778–783.

Brown T, Cupido C, Scarfone H, et al. Developmental apraxia arising from neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Neurology . 2000;55:24–30.

Hoeksma AF, Wolf H, Oei SL. Obstetrical brachial plexus injuries: incidence, natural course and shoulder contracture. Clin Rehabil . 2000;14:523–526.

Jemec B, Grobbelaar AO, Harrison DH. The abnormal nucleus as a cause of congenital facial palsy. Arch Dis Child . 2000;83:256–258.

Murty VS, Ram KD. Phrenic nerve palsy: a rare cause of respiratory distress in newborn. J Pediatr Neurosci . 2012;7:225–227.

Noetzel MJ, Wolpaw JR. Emerging concepts in the pathophysiology of recovery from neonatal brachial plexus injury. Neurology . 2000;55:5–6.

Ridgeway E, Valicenti-McDermott M, Kornhaber L, et al. Effects from birth brachial plexus injury and postural control. J Pediatr . 2013;162:1065–1067.

Stamrood CA, Blok CA, van der Zee DC. Et. al: neonatal phrenic nerve injury due to traumatic delivery. J Perinat Med . 2009;37:293–296.

Strombeck C, Krumlinde-Sundholm L. Forrsberg h: functional outcome at 5 years in children with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy with and without microsurgical reconstruction. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2000;42:148–157.

Van der Holst M, Steenbeek D, Pondaag W, et al. Neonatal brachial plexus palsy in children aged 0 to 2.5 years: parent-perceived family impact, quality of life, and upper extremity functioning. Pediatr Neurol . 2016;62:34–42.

Verzijl H, van der Zwaag B, Lammens M. Et. al: the neuropathology of hereditary congenital facial palsy vs moebius syndrome. Neurology . 2005;64:649–653.

Yang LJS. Neonatal brachial plexus palsy: management and prognostic factors. Semin Perinatol . 2014;38:222–234.

Zuarez-Easton S, Zafran N, Garmi G, et al. Risk factors for persistent disability in children and obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Perinatol . 2017;37:167–171.