The Fetus

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

The major emphasis in fetal medicine involves (1) assessment of fetal growth and maturity, (2) evaluation of fetal well-being or distress, (3) assessment of the effects of maternal disease on the fetus, (4) evaluation of the effects of drugs administered to the mother on the fetus, and (5) identification and when possible treatment of fetal disease or anomalies.

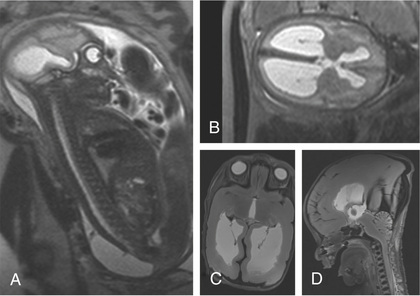

One of the most important tools used to access fetal well-being is ultrasonography (ultrasound, US); it is both safe and reasonably accurate. Indications for antenatal US include estimation of gestational age (unknown dates, discrepancy between uterine size and dates, or suspected growth restriction), assessment of amniotic fluid volume, estimation of fetal weight and growth, determination of the location of the placenta and the number and position of fetuses, and identification of congenital anomalies. Fetal MRI is a more advanced imaging method that is thought to be safe to the fetus and neonate and is used for more advanced diagnostic and therapeutic planning (Fig. 115.1 ).

Fetal Growth and Maturity

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

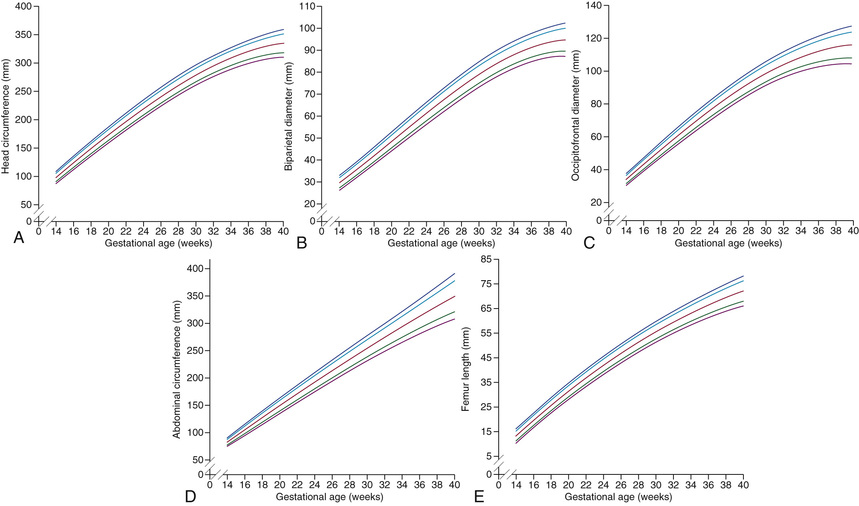

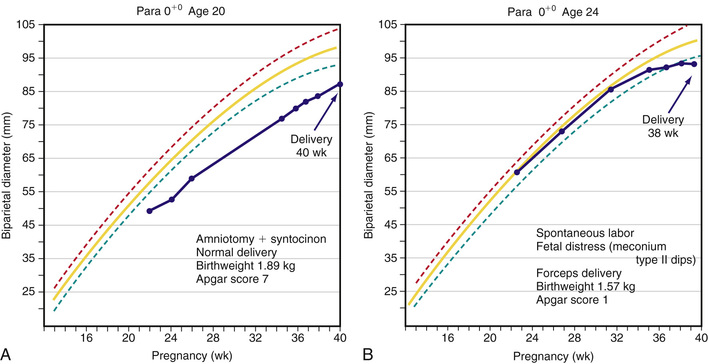

Fetal growth can be assessed by US as early as 6-8 wk of gestation by measurement of the crown-rump length. Accurate determination of gestational age can be achieved through the 1st half of pregnancy; however, first-trimester assessment by crown-rump length measurement is the most effective method of pregnancy dating. In the second trimester and beyond, a combination of biometric measures (i.e., biparietal diameter, head and abdominal circumference, femoral diaphysis length) is used for gestational age and growth assessment (Fig. 115.2 ). If a single US examination is performed, the most information can be obtained with a scan at 18-20 wk, when both gestational age and fetal anatomy can be evaluated. Serial scans assessing fetal growth are performed when risk factors for fetal growth restriction (FGR) are present. Two patterns of FGR have been identified: symmetric FGR, typically present early in pregnancy, and asymmetric FGR, typically occurring later in gestation. The most widely accepted definition of FGR in the United States is an estimated fetal weight (EFW) of less than the 10th percentile (Fig. 115.3 ). Some aspects of human fetal growth and development are summarized in Chapter 20 .

Fetal maturity and dating

are usually assessed by last menstrual period (LMP), assisted reproductive technology (ART)–derived gestational age, or US assessments. Dating by LMP assumes an accurate recall of the 1st day of LMP, a menstrual cycle that lasted 28 days, and ovulation occurring on the 14th day of the cycle, which would place the estimated delivery date (EDD)

280 days after LMP. Inaccuracies with any of these parameters can lead to an incorrectly assigned gestational age if the LMP is used for dating. Dating by ART is the most accurate method for assigning gestational age with EDD occurring 266 days after conception (when egg is fertilized by sperm). When US is used for dating, the most accurate assessment of gestational age is by first-trimester (≤ wk) US measurement of crown-rump length, which is accurate to within 5-7 days. In contrast, US dating in the second trimester is accurate to 10-14 days, and third trimester is only accurate to 21-30 days. Dating of a pregnancy is critical to determine when delivery should occur, if growth is appropriate during the pregnancy, and when testing and interventions should be offered. The earliest assessment of pregnancy dating should be used throughout the pregnancy unless methodologies used later in pregnancy are significantly different.

wk) US measurement of crown-rump length, which is accurate to within 5-7 days. In contrast, US dating in the second trimester is accurate to 10-14 days, and third trimester is only accurate to 21-30 days. Dating of a pregnancy is critical to determine when delivery should occur, if growth is appropriate during the pregnancy, and when testing and interventions should be offered. The earliest assessment of pregnancy dating should be used throughout the pregnancy unless methodologies used later in pregnancy are significantly different.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fetal growth restriction, ACOG practice bulletin no 134. Obstet Gynecol . 2013;121:1122–1133.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Method for estimating due date, ACOG committee opinion no 611. Obstet Gynecol . 2014;124:863–866.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Ultrasound in pregnancy, ACOG practice bulletin no 175. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;128:e241–e256.

Griffiths PD, Bradburn M, Campbell MJ, et al. Use of MRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities in utero (MERIDIAN): a multi-centre, prospective cohort study. Lancet . 2017;389:538–546.

Grimes DA. When to deliver a stunted fetus. Lancet . 2004;364:483–484.

Lee ACC, Katz J, Blencowe H, et al. National and regional estimates of term and preterm babies born small for gestational age in 138 low-income and middle-income countries in 2010. Lancet . 2013;1:e26–e36.

Nielsen BW, Scott RC. Brain abnormalities in fetuses: in-utero MRI versus ultrasound. Lancet . 2017;389:483–484.

Ott WJ. Intrauterine growth restriction and doppler ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med . 2000;19:661–665.

Papageorghiou AT, Ohyma EO, Altman DG, et al. International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the fetal growth longitudinal study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project. Lancet . 2014;384:869–878.

Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, et al. Association between MRI exposure during pregnancy and fetal childhood outcomes. JAMA . 2016;316(9):952–961.

Romero R, Deter R. Should serial fetal biometry be used in all pregnancies? Lancet . 2015;386:2038–2040.

Simchen MJ, Toi A, Bona M, et al. Fetal hepatic calcifications: prenatal diagnosis and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2002;187(6):1617–1622.

Stock SJ, Bricker L, Norman JE. Immediate versus deferred delivery of the preterm baby with suspected fetal compromise for improving outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2012;(7) [CD008968].

Fetal Distress

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

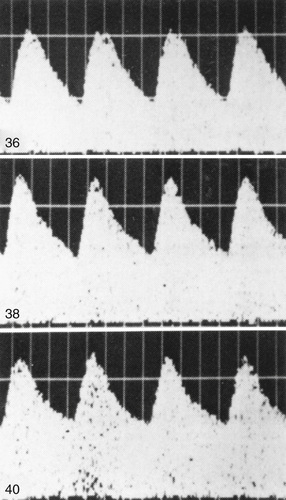

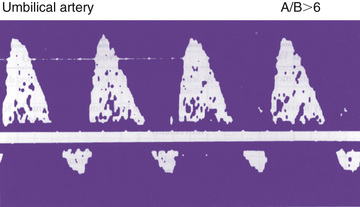

Fetal compromise may occur during the antepartum or intrapartum period. It may be asymptomatic in the antenatal period but is often suspected by maternal perception of decreased fetal movement. Antepartum fetal surveillance is warranted for women at increased risk for fetal death, including those with a history of stillbirth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), oligohydramnios or polyhydramnios, multiple gestation, rhesus sensitization, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus or other chronic maternal disease, decreased fetal movement, preterm labor, preterm rupture of membranes (PROM), and postterm pregnancy. The predominant cause of antepartum fetal distress is uteroplacental insufficiency, which may manifest clinically as IUGR, fetal hypoxia, increased vascular resistance in fetal blood vessels (Figs. 115.4 and 115.5 ), and, when severe, mixed respiratory and metabolic (lactic) acidosis. The goal of antepartum fetal surveillance is to identify the fetus at risk of stillbirth such that appropriate interventions (i.e., delivery vs optimization of underlying maternal medical condition) can be implemented to allow for a healthy live-born infant. Table 115.1 lists methods for assessing fetal well-being.

Table 115.1

Fetal Diagnosis and Assessment

| METHOD | COMMENT(S) AND INDICATION(S) |

|---|---|

| IMAGING | |

| Ultrasound (real-time) | Biometry (growth), anomaly detection, number of fetuses, sites of calcification |

| Biophysical profile | |

| Amniotic fluid volume, hydrops | |

| Ultrasound (Doppler) | Velocimetry (blood flow velocity) |

| Detection of increased vascular resistance in the umbilical artery secondary to placental insufficiency | |

| Detection of fetal anemia (MCA Doppler) | |

| MRI | Defining of lesions before fetal surgery |

| Better delineation of fetal CNS anatomy | |

| FLUID ANALYSIS | |

| Amniocentesis | Karyotype or microarray (cytogenetics), biochemical enzyme analysis, molecular genetic DNA diagnosis, or α-fetoprotein determination |

| Bacterial culture, pathogen antigen, or genome detection (PCR) | |

| Cordocentesis (percutaneous umbilical blood sampling) | Detection of blood type, anemia, hemoglobinopathies, thrombocytopenia, polycythemia, acidosis, hypoxia, thrombocytopenia, IgM antibody response to infection |

| Rapid karyotyping and molecular DNA genetic diagnosis | |

| Fetal therapy (see Table 115.5 ) | |

| FETAL TISSUE ANALYSIS | |

| Chorionic villus biopsy | Cytogenetic and molecular DNA analysis, enzyme assays |

| Circulating fetal DNA | Noninvasive molecular DNA genetic analysis including microarray analysis and chromosome number (screening method) |

| MATERNAL SERUM α-FETOPROTEIN CONCENTRATION | |

| Elevated | Twins, neural tube defects (anencephaly, spina bifida), intestinal atresia, hepatitis, nephrosis, fetal demise, incorrect gestational age |

| Reduced | Trisomies, aneuploidy |

| MATERNAL CERVIX | |

| Fetal fibronectin | Indicates possible risk of preterm birth |

| Transvaginal cervical length | Short length suggests possible risk of preterm birth |

| Bacterial culture | Identifies risk of neonatal infection (group B streptococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis ) |

| Amniotic fluid | Determination of premature rupture of membranes (PROM) |

| ANTEPARTUM BIOPHYSICAL MONITORING | |

| Nonstress test | Fetal distress; hypoxia |

| Biophysical profile and modified biophysical profile | Fetal distress; hypoxia |

| Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring | See Fig. 115.6 |

The most common noninvasive tests are the nonstress test (NST ) and the biophysical profile (BPP ). The NST monitors the presence of fetal heart rate (FHR ) accelerations that follow fetal movement. A reactive (normal) NST result demonstrates 2 FHR accelerations of at least 15 beats/min above the baseline FHR lasting 15 sec during 20 min of monitoring. A nonreactive NST result suggests possible fetal compromise and requires further assessment with a BPP. Although the NST has a low false-negative rate, it does have a high false-positive rate, which is often remedied by the BPP. The full BPP assesses fetal breathing, body movement, tone, NST, and amniotic fluid volume. It effectively combines acute and chronic indicators of fetal well-being, which improves the predictive value of abnormal testing (Table 115.2 ). A score of 2 or 0 is given for each observation. A total score of 8-10 is reassuring; a score of 6 is equivocal, and retesting should be done in 12-24 hr; and a score of 4 or less warrants immediate evaluation and possible delivery. The BPP has good negative predictive value. The modified BPP consists of the combination of an US estimate of amniotic fluid volume (the amniotic fluid index) and the NST. When results of both are normal, fetal compromise is very unlikely. Signs of progressive compromise seen on Doppler US include reduced, absent, or reversed diastolic waveform velocity in the fetal aorta or umbilical artery (see Fig. 115.5 and Table 115.1 ). The umbilical vein and ductus venosus waveforms are also used to assess the degree of fetal compromise. Fetuses at highest risk of stillbirth often have combinations of abnormalities, such as growth restriction, oligohydramnios, reversed diastolic Doppler umbilical artery blood flow velocity, and a low BPP.

Table 115.2

| BIOPHYSICAL VARIABLE | NORMAL SCORE (2) | ABNORMAL SCORE (0) |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal breathing movements (FBMs) | At least 1 episode of FBM of at least 30 sec duration in 30 min observation | Absence of FBM or no episode ≥30 sec in 30 min |

| Gross body movement | At least 3 discrete body/limb movements in 30 min (episodes of active continuous movement considered a single movement) | 2 or fewer episodes of body/limb movements in 30 min |

| Fetal tone |

At least 1 episode of active extension with return to flexion of fetal limb(s) or trunk Opening and closing of hand considered evidence of normal tone |

Either slow extension with return to partial flexion or movement of limb in full extension or absence of fetal movement with the hand held in complete or partial deflection |

| Reactive fetal heart rate (FHR) | At least 2 episodes of FHR acceleration of ≥15 beats/min and at least 15 sec in duration associated with fetal movement in 30 min | Less than 2 episodes of acceleration of FHR or acceleration of <15 beats/min in 30 min |

| Quantitative amniotic fluid (AF) volume* | At least 1 pocket of AF that measures at least 2 cm in 2 perpendicular planes | Either no AF pockets or a pocket <2 cm in 2 perpendicular planes |

* Modification of the criteria for reduced amniotic fluid from <1 cm to <2 cm would seem reasonable. Ultrasound is used for biophysical assessment of the fetus.

From Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams JD, editors: Maternal-fetal medicine: principles and practice, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders.

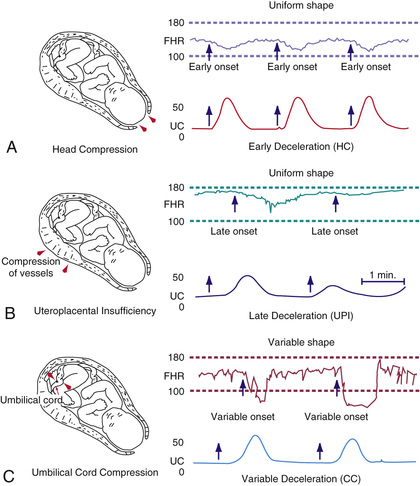

Fetal compromise during labor may be detected by monitoring the FHR, uterine pressure, and fetal scalp blood pH (Fig. 115.6 ). Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring detects abnormal cardiac patterns by instruments that compute the beat-to-beat FHR from a fetal electrocardiographic signal. Signals are derived either from an electrode attached to the fetal presenting part, from an ultrasonic transducer placed on the maternal abdominal wall to detect continuous ultrasonic waves reflected from the contractions of the fetal heart, or from a phonotransducer placed on the mother's abdomen. Uterine contractions are recorded from an intrauterine pressure catheter or from an external tocotransducer applied to the maternal abdominal wall overlying the uterus. FHR patterns show various characteristics, some of which suggest fetal compromise. The baseline FHR is determined over 10 min devoid of accelerations or decelerations. Over the course of pregnancy, the normal baseline FHR gradually decreases from approximately 155 beats/min in early pregnancy to 135 beats/min at term. The normal range throughout pregnancy is 110-160 beats/min. Tachycardia (>160 beats/min) is associated with early fetal hypoxia, maternal fever, maternal hyperthyroidism, maternal β-sympathomimetic drug or atropine therapy, fetal anemia, infection, and some fetal arrhythmias. Arrhythmias do not generally occur with congenital heart disease and may resolve spontaneously at birth. Fetal bradycardia (<110 beats/min) may be normal (e.g., 105-110 beats/min) but may occur with fetal hypoxia, placental transfer of local anesthetic agents and β-adrenergic blocking agents, and occasionally, heart block with or without congenital heart disease.

Normally, the baseline FHR is variable as a result of opposing forces from the fetal sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Variability is classified as follows: absence of variability, if an amplitude change is undetectable; minimal variability, if amplitude range is ≤5 beats/min; moderate variability, if amplitude range is 6-25 beats/min; and marked variability, if amplitude range is >25 beats/min. Variability may be decreased or lost with fetal hypoxemia or the placental transfer of drugs such as atropine, diazepam, promethazine, magnesium sulfate, and most sedative and narcotic agents. Prematurity, the sleep state, and fetal tachycardia may also diminish beat-to-beat variability.

Accelerations or decelerations of the FHR in response to or independent of uterine contractions may also be monitored (see Fig. 115.6 ). An acceleration is an abrupt increase in FHR of ≥15 beats/min in ≥15 sec. The presence of accelerations or moderate variability reliably predicts the absence of fetal metabolic acidemia. However, their absence does not reliably predict fetal acidemia or hypoxemia. Early decelerations are a physiologic vagal response to uterine contractions, with resultant fetal head compression, and represent a repetitive pattern of gradual decrease and return of the FHR that is coincidental with the uterine contraction (Table 115.3 ). Variable decelerations are associated with umbilical cord compression and are characterized by a V or U shaped pattern, are abrupt in onset and resolution, and may occur with or without uterine contractions.

Table 115.3

Characteristics of Decelerations of Fetal Heart Rate (FHR)

From Macones GA, Hankins GDV, Spong CY, et al: The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines, Obstet Gynecol 112:661–666, 2008.

Late decelerations are associated with fetal hypoxemia and are characterized by onset after a uterine contraction is well established and persists into the interval following resolution of the contraction. The late deceleration pattern is usually associated with maternal hypotension or excessive uterine activity, but it may be a response to any maternal, placental, umbilical cord, or fetal factor that limits effective oxygenation of the fetus. The significance of late decelerations varies according to the underlying clinical context. They are most likely to be associated with true fetal hypoxemia/acidemia when they are recurrent and occur in conjunction with decreased or absent variability. Late decelerations represent a compensatory, chemoreceptor-mediated response to fetal hypoxemia. The transient decrease in FHR serves to increase ventricular preload during the peak of hypoxemia (i.e., at the crest of a uterine contraction). If fetal acidemia progresses, late decelerations may become less pronounced or absent, indicating severe hypoxic depression of myocardial function. Prompt delivery is indicated if late decelerations are unresponsive to oxygen supplementation, hydration, discontinuation of labor stimulation, and position changes. Approximately 10–15% of term fetuses have terminal (just before delivery) FHR decelerations that are usually benign if they last <10 min before delivery.

A 3-tier system has been developed by a panel of experts for interpretation of FHR tracings (Table 115.4 ). Category I tracings are normal and are strongly predictive of normal fetal acid-base status at the time of the observation. Category II tracings are not predictive of abnormal fetal status, but there is insufficient evidence to categorize them as category I or III; therefore further evaluation, surveillance, and reevaluation are indicated. Category III tracings are abnormal and predictive of abnormal fetal acid-base status at the time of observation. Category III tracings require prompt evaluation and efforts to resolve expeditiously the abnormal FHR as previously discussed for late decelerations.

Table 115.4

Three-Tier Fetal Heart Rate (FHR) Interpretation System

Adapted from Macones GA, Hankins GDV, Spong CY, et al: The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines, Obstet Gynecol 112:661–666, 2008.

Umbilical cord blood samples obtained at delivery are useful to document fetal acid-base status. Although the exact cord blood pH value that defines significant fetal acidemia is unknown, an umbilical artery pH <7.0 has been associated with greater need for resuscitation and a higher incidence of respiratory, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and neurologic complications. Nonetheless, in many cases, even when a low pH is detected, newborn infants are neurologically normal.

Bibliography

Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2006;(3) [CD006066].

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol . 2009;114:192–202.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antepartum fetal surveillance, ACOG practice bulletin no 145. Obstet Gynecol . 2014;124:182–192.

Cahill AG, Caughey AB, Roehl KA, et al. Terminal fetal heart decelerations and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol . 2013;122:1070–1076.

Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al. Predictive accuracy of serial transvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA . 2017;317(10):1047–1056.

Macones GA, Hankins GDV, Spong CY, et al. The 2008 national institute of child health and human development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines. Obstet Gynecol . 2008;112:661–666.

Pathak S, Lees C. Ultrasound structural fetal anomaly screening: an update. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2009;94:F384–F390.

Maternal Disease and the Fetus

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

Infectious Diseases

See Table 114.3 in Chapter 114 for a list of common maternal infectious diseases that impact the fetus and newborn.

Almost any maternal infection with severe systemic manifestations may result in miscarriage, stillbirth, or premature labor. Whether these results are a consequence of infection of the fetus or are secondary to maternal illness is not always clear. Another important factor to consider when dealing with infectious diseases in pregnancy is the timing of infection. In general, infections that occur earlier in the pregnancy (first or second trimester) are more likely to result in miscarriage or problems with organogenesis, such as the neuromigrational abnormalities seen in newborns with congenital CMV infections.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common congenital infection, affecting 0.2–2.2% of all neonates (see Chapter 282 ). Perinatal transmission can occur at any time during the pregnancy; however, the most devastating sequelae occur with first-trimester infection. After a primary infection, 12–18% of neonates will have signs and symptoms at birth, and as many as 25% can develop long-term complications. The most common complication is congenital hearing loss . Severely affected infants have an associated 30% mortality, and 65–80% of survivors develop severe neurologic morbidity. A mother with a history of CMV may experience reactivation of the disease or may be infected with a different strain of the virus and transmit the infection to the fetus. Currently, there are no well-studied or validated antenatal therapies targeted toward decreasing disease severity or preventing congenital infection in the setting of primary maternal CMV infection. Preliminary data from some studies have demonstrated promise with drugs such as valganciclovir and CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin, but confirmatory data are lacking. For this reason, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not recommend antenatal therapy for congenital CMV infection outside of an established research protocol.

Noninfectious Diseases (see Table 114.2 )

Maternal diabetes increases the risk for neonatal hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, respiratory distress syndrome and other respiratory problems, feeding difficulties, polycythemia, macrosomia, growth restriction, myocardial dysfunction, jaundice, and congenital malformations (see Chapter 127.1 ). There is an increased risk of uteroplacental insufficiency, polyhydramnios, and fetal demise in poorly controlled diabetic mothers. Preeclampsia-eclampsia , chronic hypertension , and chronic renal disease can result in IUGR, prematurity, and fetal death, all probably caused by diminished uteroplacental perfusion.

Uncontrolled maternal hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism is responsible for relative infertility, spontaneous abortion, premature labor, and fetal death. Hypothyroidism in pregnant women (even if mild or asymptomatic) can adversely affect neurodevelopment of the child, especially if the newborn is found to have congenital hypothyroidism.

Maternal immunologic diseases such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, and Graves disease, all of which are mediated by immunoglobulin G autoantibodies that can cross the placenta, frequently cause transient illness in the newborn. Maternal autoantibodies to the folate receptor are associated with neural tube defects (NTDs ), whereas maternal immunologic sensitization to fetal antigens may be associated with neonatal alloimmune hepatitis and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT ).

Untreated metabolic disorders such as maternal phenylketonuria (PKU) results in miscarriage, congenital cardiac malformations, and injury to the brain of a nonphenylketonuric heterozygous fetus. Women whose PKU is well controlled before conception can avoid these complications and have a normal newborn.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pregestational diabetes mellitus, ACOG practice bulletin no 60. Obstet Gynecol . 2005;105:675–685.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gestational diabetes mellitus, ACOG ACOG practice bulletin no 137. Obstet Gynecol . 2013;122:406–416.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Thyroid disease in pregnancy, ACOG practice bulletin no 148. Obstet Gynecol . 2015;125:996–1005.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cytomegalovirus, parvovirus b19, varicella-zoster, and toxoplasmosis in pregnancy, ACOG practice bulletin no 151. Obstet Gynecol . 2015;125:1510–1525.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of women with phenylketonuria, ACOG committee opinion no 636. Obstet Gynecol . 2015;125:1548–1550.

Chambers C. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and congenital malformations. BMJ . 2009;339:703–704.

Lockshin M, Salmon J, Erkan D. Pregnancy and rheumatic diseases. Creasy RK, Resnik R. Maternal-fetal medicine: principles and practice . ed 7. Saunders: Philadelphia; 2014.

Louik C, Lin A, Weler MM, et al. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med . 2007;356:2675–2682.

Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet . 2016;387:999–1010.

Waller DR, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, et al. Prepregnancy obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med . 2007;161:745–750.

Medication and Teratogen Exposure

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

When an infant or child has a congenital malformation or is developmentally delayed, the parents often wrongly blame themselves and attribute the child's problems to events that occurred during pregnancy. Because benign infections occur, and several nonteratogenic drugs are often taken during many pregnancies, the pediatrician must evaluate the presumed viral infections and the drugs ingested to help parents understand their child's birth defect. The causes of approximately 40% of congenital malformations are unknown. Although only relatively few agents are recognized to be teratogenic in humans, new agents continue to be identified. An excellent internet-based resource known as Reprotox (reprotox.org ) provides comprehensive and routinely updated summaries on drugs and other potentially teratogenic agents in pregnancy. Overall, only 10% of anomalies are caused by recognizable teratogens (see Chapter 128 ). The time of exposure that is most likely to cause injury is usually during organogenesis at <60 days of gestation. Specific agents produce predictable lesions. Some agents have a dose or threshold effect, below which no alterations in growth, function, or structure occur. Genetic variables such as the presence of specific enzymes may metabolize a benign agent into a more toxic, teratogenic form (e.g., phenytoin conversion to its epoxide). In many circumstances the same agent and dose may not consistently produce the lesion.

Reduced enzyme activity of the folate methylation pathway, particularly the formation of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, may be responsible for NTDs or other birth defects. The common thermolabile mutation of 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase may be one of the enzymes responsible. Folate supplementation for all pregnant women (by direct fortification of cereal grains, which is mandatory in the United States), and oral folic acid tablets taken during organogenesis may overcome this genetic enzyme defect, thus reducing the incidence of NTDs and perhaps other birth defects.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies drugs into 5 pregnancy risk categories. Category A drugs pose no risk on the basis of evidence from controlled human studies. For category B drugs, either no risk has been shown in animal studies but no adequate studies have been done in humans, or some risk has been shown in animal studies but these results are not confirmed by human studies. For category C drugs, either definite risk has been shown in animal studies but no adequate human studies have been performed, or no data are available from either animal or human studies. Category D includes drugs with some risk but with a benefit that may exceed that risk for the treated life-threatening condition, such as streptomycin for tuberculosis. Category X is for drugs that are contraindicated in pregnancy on the basis of animal and human evidence and for which the risk exceeds the benefits.

The use of medications or herbal remedies during pregnancy is potentially harmful to the fetus. Consumption of medications occurs during the majority of pregnancies. The average mother has taken 4 drugs other than vitamins or iron during pregnancy. Almost 40% of pregnant women receive a drug for which human safety during pregnancy has not been established (category C pregnancy risk). Moreover, many women are exposed to potential reproductive toxins, such as occupational, environmental, or household chemicals, including solvents, pesticides, and hair products. The effects of drugs taken by the mother vary considerably, especially in relation to the time in pregnancy when they are taken and the fetal genotype for drug-metabolizing enzymes.

Miscarriage or congenital malformations result from the maternal ingestion of teratogenic drugs during the period of organogenesis. Maternal medications taken later, particularly during the last few weeks of gestation or during labor, tend to affect the function of specific organs or enzyme systems, and these adversely affect the neonate rather than the fetus (Tables 115.5 and 115.6 ). The effects of drugs may be evident immediately in the delivery room or later in the neonatal period, or they may be delayed even longer. The administration of diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy, for instance, increased the risk for vaginal adenocarcinoma in female offspring in the 2nd or 3rd decade of life.

Table 115.5

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; CNS, central nervous system; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; LBW, low birthweight; VACTERAL, vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal, arterial, limb.

Table 115.6

Agents Acting on Pregnant Women That May Adversely Affect the Newborn Infant*

* See also Table 115.5 .

CNS, Central nervous system; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Often the risk of controlling maternal disease must be balanced with the risk of possible complications in the fetus. Most women with epilepsy have normal fetuses. Nonetheless, several commonly used antiepileptic drugs are associated with congenital malformations. Infants exposed to valproic acid may have multiple anomalies, including NTDs, hypospadias, facial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and limb defects. In addition, they have lower developmental index scores than unexposed infants and infants exposed to other common antiepileptic drugs.

Moderate or high alcohol intake (≥7 drinks/wk or ≥3 drinks on multiple occasions) is a risk for fetal alcohol syndrome . The exposed fetuses are at risk for growth failure, central nervous system abnormalities, cognitive defects, and behavioral problems. It must be emphasized, however, that there is no known dose-response threshold for fetal alcohol exposure; therefore pregnant women should be counseled toward complete abstinence. Smoking during pregnancy is associated with IUGR and facial clefts.

Chronic heroin (opioid) use throughout pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fetal growth restriction, placental abruption, stillbirth, preterm birth, and intrauterine passage of meconium. Opiates readily cross the placenta; therefore these effects are postulated to be related to cyclic fetal opiate withdrawal. Furthermore, the lifestyle issues surrounding opioid abuse, including lack of or late entry into prenatal care, place the mother at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Therefore, opioid maintenance therapy with either methadone or buprenorphine is recommended for opioid-dependent pregnant women to prevent complications of illicit opioid use and narcotic withdrawal, encourage prenatal care and drug treatment, reduce criminal activity, and avoid risks to the patient of associating with a drug culture.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) occurs in the setting of opioid maintenance treatment or illicit drug use; thus opiate maintenance therapy is not preventive in this regard. Methadone is considered first-line therapy for treatment of opioid dependence in pregnancy; buprenorphine is an acceptable alternative in the appropriately selected patient. There is no established, dose-response relationship between methadone or buprenorphine and risk/severity of NAS, so the lowest effective dose to eliminate maternal cravings/withdrawal is recommended. Methadone is associated with a lower birthweight than buprenorphine. Both medications have a similar rate of NAS requiring treatment (approximately 50%); however, the use of antenatal buprenorphine has been associated with significantly lower dosages of morphine to treat NAS and significantly shorter NAS-related hospital stays than methadone. For these reasons, buprenorphine may be preferred under certain circumstances.

The specific mechanism of action is known or postulated for very few teratogens. Warfarin , a vitamin K antagonist used for anticoagulation, prevents the carboxylation of γ-carboxyglutamic acid, which is a component of osteocalcin and other vitamin K–dependent bone proteins. The teratogenic effect of warfarin on developing cartilage, especially nasal cartilage, appears to be avoided if the pregnant woman's anticoagulation treatment is switched from warfarin to heparin for the period between weeks 6 and 12 of gestation. However, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is maintained with exposure throughout pregnancy. For these reasons, low-molecular-weight heparin is the preferred anticoagulant when treating pregnant women.

Hypothyroidism in the fetus may be caused by maternal ingestion of an excessive amount of iodide or propylthiouracil; each interferes with the conversion of inorganic to organic iodides. Furthermore, there is an interaction between genetic factors and susceptibility to certain drugs or environmental toxins. Phenytoin teratogenesis, for example, may be mediated by genetic differences in the enzymatic production of epoxide metabolites. Polymorphisms of genes encoding enzymes that metabolize the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke influence the growth-restricting effects of smoking on the fetus.

Recognition of teratogenic potential from a variety of sources offers the opportunity to prevent related birth defects. If a pregnant woman is informed of the potentially harmful effects of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs on her unborn infant, she may be motivated to avoid consumption of these substances during pregnancy. A woman with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus may significantly decrease her risk for having a child with birth defects by achieving good control of her disease before conception. Lastly, in view of the limits of current knowledge regarding the fetal effects of maternal medication use, drugs and herbal agents should only be prescribed during pregnancy after carefully weighing the maternal benefit against the risk of fetal harm.

Bibliography

Ackerman JP, Riggins T, Black MM. A review of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure among school-aged children. Pediatrics . 2010;125:554–565.

Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med . 2007;356:2684–2692.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Committee opinion no 524. Obstet Gynecol . 2012;119:1070.

Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2004;191:398–407.

Bromley RL, Weston J, Marson AG. Maternal use of antiepileptic agents during pregnancy and major congenital malformations in children. JAMA . 2017;318(17):1700–1701.

Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, et al. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2011;204:314.e1–314.e11.

Bullo M, Tschumi S, Bucher BS, et al. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists. Hypertension . 2012;60:444–450.

Christensen J, Gronbørg TK, Sørensen MJ, et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA . 2013;309:1696–1702.

Cummings C, Stewart M, Stevenson M, et al. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to lamotrigine, sodium valproate and carbamazepine. Arch Dis Child . 2011;96:643–647.

DeMarini DM, Preston RJ. Smoking while pregnant: transplacental mutagenesis of the fetus by tobacco smoke. JAMA . 2005;293:1264–1265.

De-Regil LM, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Dowswell T, et al. Effects of safety and periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2010;(10) [CD007950].

De-Regil LM, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Dowswell T, et al. Effects of safety and periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2010;(10) [CD007950].

Djokanovic N, Klieger-Grossman C, Pupco A, et al. Safety of infliximab use during pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol . 2011;32:93–97.

Dubnov-Raz G, Juurlink DN, Fogelman R, et al. Antenatal use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and QT interval prolongation in newborns. Pediatrics . 2008;122:e710–e715.

Edison RJ, Muenke M. Mechanistic and epidemiologic considerations in the evaluation of adverse birth outcomes following gestational exposure to statins. Am J Med Genet A . 2004;131A:287–298.

El Marroun H, Jaddoe VWV, Hudziak JJ, et al. Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, fetal growth, and risk of adverse birth outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2012;69:706–714.

Foulds N, Walpole I, Elmslie F, et al. Carbimazole embryopathy: an emerging phenotype. Am J Med Genet A . 2005;132:130–135.

Gill SK, O'Brien L, Einarson TR, et al. The safety of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol . 2009;104:1541–1545.

Graham JM Jr, Edwards MJ, Edwards MJ. Teratogen update: gestational effects of maternal hyperthermia due to febrile illnesses and resultant patterns of defects in humans. Teratology . 1998;58:209–221.

Hernández-Díaz S, Smith CR, Shen A, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology . 2012;78:1692–1699.

Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Mathews TJ, et al. Impact of folic acid fortification of the US food supply on the occurrence of neural tube defects. JAMA . 2001;285:2981–2986.

Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med . 2010;363:2320–2331.

Jones KJ, Lacro RV, Johnson KA, et al. Pattern of malformations in the children of women treated with carbamazepine during pregnancy. N Engl J Med . 1989;320:1661–1666.

Julsgaard M, Christensen LA, Gibson PR, et al. Concentrations of adalimumab and infliximab in mothers and newborns and effects on infection. Gastroenterology . 2016;151(1):110–119.

Kaufman RH, Adam E, Hatch EE, et al. Continued follow-up of pregnancy outcomes in diethylstilbestrol-exposed offspring. Obstet Gynecol . 2000;96:483–489.

Khattak S, K-Moghtader G, McMartin K, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to organic solvents: a prospective controlled study. JAMA . 1999;281:1106–1109.

Koren G, Nordeng H. SSRIs and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. BMJ . 2012;344:d7642.

Koren G, Pastuszak A, Ito S. Drugs in pregnancy. N Engl J Med . 1998;338:1128–1137.

Lammer EJ, Chen CT, Hoar RM, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med . 1985;313:837–841.

Lund N, Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2009;163:949–954.

Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, et al. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:2528–2534.

Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:1507–1605.

Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Hviid A. Newer-generation antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major birth defects. JAMA . 2011;305:1996–2002.

Moran LR, Almeida PG, Worden S, et al. Intrauterine baclofen exposure: a multidisciplinary approach. Pediatrics . 2004;114:e267–e269.

Moretti ME, Bar-Oz B, Fried S, et al. Maternal hyperthermia and the risk for neural tube defects in offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology . 2005;16:216–219.

Nadebaum C, Anderson VA, Vajda F, et al. Language skills of school-aged children prenatally exposed to antiepileptic drugs. Neurology . 2011;76:719–726.

Oei J, Abdel-Latif ME, Clark R, et al. Short-term outcomes of mothers and infants exposed to antenatal amphetamines. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2010;95:F36–F41.

Patorno E, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac malformations. N Engl J Med . 2017;376(23):2245–2254.

Persson M, Cnattingius S, Villamor E, et al. Risk of major congenital malformations in relation to maternal overweight and obesity severity: cohort study 1.2 million singletons. BMJ . 2017;357:2563.

Ramos E, St-André M, Rey E, et al. Duration of antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations. Br J Psych . 2008;192:344–350.

Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisahvili L, et al. Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication. JAMA Psychiatry . 2013;70:436–443.

Seligman NS, Almario CV, Hayes EJ, et al. Relationship between maternal methadone dose at delivery and neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr . 2010;157:428–433.

Seo GH, Kim TH, Chung JH. Antithyroid drugs and congenital malformations: a nationwide Korean cohort study. Ann Intern Med . 2018;168(6):405–413.

Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Vollset SE, et al. Mid-pregnancy cotinine and risks of orofacial clefts and neural tube defects. J Pediatr . 2009;154:17–19.

Simon A, Warszawski J, Kariyawasam D, et al. Association of prenatal and postnatal exposure to lopinavir-ritonavir and adrenal dysfunction among uninfected infants of HIV-infected mothers. JAMA . 2011;306:70–78.

Stephansson O, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and infant mortality. JAMA . 2013;309:48–54.

Sujan AC, Rickert ME, Öberg S, et al. Associations of maternal antidepressant use during the first trimester of pregnancy with preterm birth, small for gestational age, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. JAMA . 2017;217(15):1553–1562.

Tomson T, Battino D. Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs: state of the art. Curr Opin Neurol . 2005;18:135–140.

Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol . 2018;17(6):530–538.

Vento M, Aytes AP, Ledo A, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil during pregnancy: some words of caution. Pediatrics . 2008;122:184–185.

Radiation

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

See also Chapter 736 .

Accidental exposure of a pregnant woman to radiation is a common cause for anxiety about whether her fetus will have genetic abnormalities or birth defects. It is unlikely that exposure to diagnostic radiation will cause gene mutations; no increase in genetic abnormalities has been identified in the offspring exposed as unborn fetuses to the atomic bomb explosions in Japan in 1945.

A more realistic concern is whether the exposed human fetus will show birth defects or a higher incidence of malignancy. The background fetal radiation exposure in a given pregnancy is approximately 0.1 rad. The estimated radiation dose for most radiographs is <0.1 rad and for most CT scans <5 rad (maximum recommended radiation exposure in pregnancy). Imaging studies with high radiation exposure (e.g., CT scans) can be modified to ensure that radiation doses are kept as low as possible. Thus, single diagnostic studies do not result in radiation doses high enough to affect the embryo or fetus. Pregnancy termination should not be recommended only on the basis of diagnostic radiation exposure. Most of the evidence suggests that usual fetal radiation exposure does not increase the risk of childhood leukemia and other cancers; although some sources suggest that a 1-2 rad fetal radiation exposure may confer a 1.5-2–fold increased risk of childhood leukemia, which has a background risk of 1 in 3,000. Before implantation (0-2 wk postconception), radiation doses of 5-10 rad may result in miscarriage. At 2-8 wk gestation, doses in excess of 20 rad have been associated with congenital anomalies and fetal growth restriction. Severe intellectual disabilities can occur with exposures of ≥25 rad before 25 wk gestation. The available data suggest no harmful fetal effect of diagnostic MRI or US, which do not involve radiation.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and lactation, ACOG committee opinion no 656. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;127:e75–e80.

Brent RL. Saving lives and changing family histories: appropriate counseling of pregnant women and men and women of reproductive age, concerning the risk of diagnostic radiation exposures during and before pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2009;200:4–24.

Intrauterine Diagnosis of Fetal Disease

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

See Table 115.1 and Chapter 115.2 .

Diagnostic procedures are used to identify fetal diseases when direct fetal treatment is possible, to better direct neonatal care, when a decision is made to deliver a viable but premature infant to avoid intrauterine fetal demise, or when pregnancy termination is being considered. Fetal assessment is also indicated in a broader context when the family, medical, or reproductive history of the mother suggests the presence of a high-risk pregnancy or a high-risk fetus (see Chapters 114 and 115.3 ).

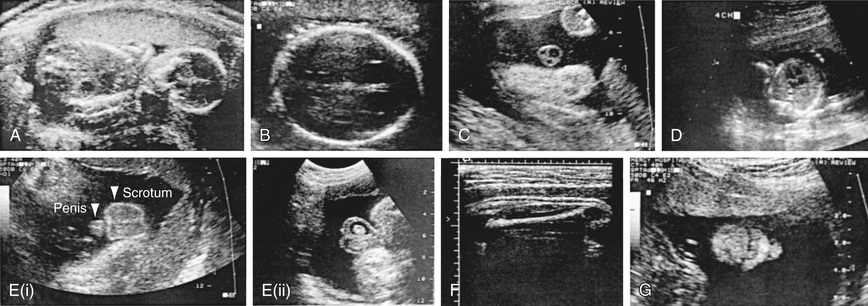

Various methods are used for identifying fetal disease (see Table 115.1 ). Fetal US imaging may detect fetal growth abnormalities (by previously outlined biometric measurements) or fetal malformations (Fig. 115.7 ). Serial determinations of growth velocity and the head-to-abdomen circumference ratio enhance the ability to detect IUGR. Real-time US may identify placental abnormalities (abruptio placentae, placenta previa) and fetal anomalies such as hydrocephalus, NTDs, duodenal atresia, diaphragmatic hernia, renal agenesis, bladder outlet obstruction, congenital heart disease, limb abnormalities, sacrococcygeal teratoma, cystic hygroma, omphalocele, gastroschisis, and hydrops (Table 115.7 ).

Table 115.7

Significance of Fetal Ultrasonographic Anatomic Findings

| PRENATAL OBSERVATION | DEFINITION | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | SIGNIFICANCE | POSTNATAL EVALUATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilated cerebral ventricles | Ventriculomegaly ≥10 mm |

Hydrocephalus Hydranencephaly Dandy-Walker cyst Agenesis of corpus callosum Volume loss |

Transient isolated ventriculomegaly is common and usually benign. Persistent or progressive ventriculomegaly is more worrisome. Identify associated cranial and extracranial anomalies. |

Serial head US or MRI Evaluate for extracranial anomalies. |

| Choroid plexus cysts |

Size ~10 mm: unilateral or bilateral 1–3% incidence |

Abnormal karyotype (trisomy 18, 21) Increased risk if AMA |

Often isolated, benign; resolves by 24-28 wk. Fetus should be examined for other organ anomalies; if additional anomalies present, amniocentesis should be performed for karyotype. |

Head US Examine for extracranial anomalies; karyotype if indicated. |

| Nuchal fold thickening | ≥6 mm at 15-20 wk |

Cystic hygroma trisomy 21, 18 Turner syndrome (XO) Other genetic syndromes Normal (~25%) |

~50% of affected fetuses have chromosome abnormalities. Amniocentesis for karyotype needed. |

Evaluate for multiple organ malformations; karyotype if indicated. |

| Dilated renal pelvis |

Pyelectasis ≥4 to 10 mm 0.6–1% incidence |

Normal variant Uteropelvic junction obstruction Vesicoureteral reflux Posterior ureteral valves Entopic ureterocele Large-volume nonobstruction |

Often “physiologic” and transient Reflux is common. If dilation is >10 mm or associated with caliectasis, pathologic cause should be considered. If large bladder present, posterior urethral valves and megacystis–microcolon hypoperistalsis syndrome should be considered. |

Repeat ultrasonography on day 5 and at 1 mo; voiding cystourethrogram, prophylactic antibiotics |

| Echogenic bowel | 0.6% incidence | CF, meconium peritonitis, trisomy 21 or 18, other chromosomal abnormalities cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, GI obstruction, intrauterine bleeding (fetal swallowing of blood) |

Often normal Consider CF, aneuploidy, and TORCH. |

Sweat chloride and DNA testing Karyotype Surgery for obstruction Evaluation for TORCH |

| Stomach appearance | Small or absent or with double bubble |

Upper GI obstruction (esophageal atresia) Double bubble signifies duodenal atresia Aneuploidy Polyhydramnios Stomach in chest signifies diaphragmatic hernia |

Must also consider neurologic disorders that reduce swallowing. >30% with double bubble have trisomy 21. |

Chromosomes; kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph if indicated; upper GI series; neurologic evaluation |

CF, Cystic fibrosis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; GI, gastrointestinal; TORCH, toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, CMV, herpes simplex syndrome; US, ultrasound.

Real-time US also facilitates performance of needle-guided procedures (i.e. cordocentesis) and the BPP by imaging fetal breathing, body movements, tone, and amniotic fluid volume (see Table 115.2 ). Doppler velocimetry assesses fetal arterial blood flow (vascular resistance) (see Figs. 115.4 and 115.5 ). Fetal MRI is used to better define abnormalities detected on US and to help with prognostication (see Fig. 115.1 ).

Amniocentesis , the transabdominal withdrawal of amniotic fluid during pregnancy for diagnostic purposes (see Table 115.1 ), is a common obstetric procedure. It is frequently performed to evaluate for infection. It is also done for genetic indications, usually between the 15th and 20th wk of gestation, with results available as soon as 24-48 hr for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing and 2-3 wk for microarray testing. The most common indication for genetic amniocentesis is advanced maternal age ; the risk for chromosome abnormality at term at age 21 yr is 1 : 525, vs 1 : 6 at age 49 yr. ACOG recommends that all pregnant women be offered amniocentesis to evaluate further for an underlying genetic condition such as Down syndrome. Analysis of amniotic fluid may also help in identifying NTDs (elevation of α-fetoprotein [AFP] and presence of acetylcholinesterase). Additionally, families with a known genetic syndrome may be offered prenatal genetic testing from amniotic fluid or amniocytes obtained via amniocentesis or CVS.

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) is performed in the first trimester, either transvaginally or transabdominally. The sample obtained is placental in origin, which can sometimes be problematic because aneuploidy may be present in the placenta and not the fetus, a condition known as confined placental mosaicism , which can give a false-positive rate as high as 3%. Furthermore, CVS may be associated with a slightly higher risk of fetal loss than amniocentesis.

Amniocentesis can be carried out with little discomfort to the mother. Procedure-related complications are relatively rare, and many can be avoided by using a US-guided approach. These risks include direct damage to the fetus, placental puncture and bleeding with secondary damage to the fetus, stimulation of uterine contraction and premature labor, chorioamnionitis, maternal sensitization to fetal blood, and pregnancy loss. Best available data indicate that the pregnancy loss rate associated with amniocentesis is 1 : 500-900 procedures. Amniocentesis is not recommended before 14 wk of gestation because this has been associated with a higher risk of pregnancy loss, ruptured membranes, and clubfoot.

Cordocentesis , or percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS), is used to diagnose fetal hematologic abnormalities, genetic disorders, infections, and fetal acidosis (see Table 115.1 ). Under direct US visualization, a long needle is passed into the umbilical vein at its entrance to the placenta or in a free loop of cord. Transfusion or administration of drugs can be performed through the umbilical vein (Table 115.8 ). The predominant indication for this procedure is for confirmation of fetal anemia (in Rh isoimmunization) or thrombocytopenia (NAIT), with subsequent transfusion of packed red blood cells or platelets into the umbilical venous circulation.

Table 115.8

| DISORDER | POSSIBLE TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| HEMATOLOGIC | |

| Anemia with hydrops (erythroblastosis fetalis) | Cordocentesis of umbilical vein with packed red blood cell transfusion |

| Isoimmune thrombocytopenia | Umbilical vein platelet transfusion, maternal IVIG |

| Autoimmune thrombocytopenia (ITP) | Maternal steroids and IVIG |

| METABOLIC/ENDOCRINE | |

| Maternal phenylketonuria (PKU) | Phenylalanine restriction |

| Fetal galactosemia | Galactose-free diet (?) |

| Multiple carboxylase deficiency | Biotin if responsive |

| Methylmalonic acidemia | Vitamin B12 if responsive |

| 21-Hydroxylase deficiency | Dexamethasone if female fetus |

| Maternal diabetes mellitus | Tight insulin control during pregnancy, labor, and delivery |

| Fetal goiter | Maternal hyperthyroidism—maternal propylthiouracil |

| Fetal hypothyroidism—intraamniotic thyroxine | |

| Bartter syndrome | Maternal indomethacin may prevent nephrocalcinosis and postnatal sodium losses |

| FETAL DISTRESS | |

| Hypoxia | Maternal oxygen, position changes |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | Improve macronutrients and micronutrients if deficient, smoking cessation, treatment of maternal disease, antenatal fetal surveillance |

| Oligohydramnios, premature rupture of membranes with variable deceleration | Antenatal fetal surveillance |

| Approach dependent on etiology | |

| Amnioinfusion (intrapartum) | |

| Polyhydramnios | Antenatal fetal surveillance |

| Approach dependent on etiology | |

| Amnioreduction if indicated, | |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | Maternal digoxin,* flecainide, procainamide, amiodarone, quinidine |

| Lupus anticoagulant | Maternal aspirin and heparin |

| Meconium-stained fluid | Amnioinfusion |

| Congenital heart block | Dexamethasone, pacemaker (with hydrops) |

| Premature labor | Magnesium sulfate, nifedipine, indomethacin with antenatal corticosteroids (betamethasone) |

| RESPIRATORY | |

| Pulmonary immaturity | Betamethasone |

| Bilateral chylothorax—pleural effusions | Thoracentesis, pleuroamniotic shunt |

| CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES † | |

| Neural tube defects | Folate, vitamins (prevention); fetal surgery ‡ |

| Posterior urethral valves, urethral atresia (lower urinary tract obstruction) | Percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunt |

| Cystic adenomatoid malformation (with hydrops) | Pleuroamniotic shunt or resection ‡ |

| Fetal neck masses | Secure an airway with EXIT procedure ‡ |

| INFECTIOUS DISEASE | |

| Group B streptococcus colonization | Ampicillin, penicillin |

| Chorioamnionitis | Antibiotics and delivery |

| Toxoplasmosis | Spiramycin, pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, folic acid |

| Syphilis | Penicillin |

| Tuberculosis | Antituberculosis drugs |

| Lyme disease | Penicillin, ceftriaxone |

| Parvovirus | Intrauterine red blood cell transfusion for hydrops, severe anemia |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Azithromycin |

| HIV-AIDS | Maternal and neonatal antiretroviral therapy (see Chapter 302 ) |

| Cytomegalovirus | No approved prenatal treatments |

| OTHER | |

| Nonimmune hydrops (anemia) | Umbilical vein packed red blood cell transfusion |

| Narcotic abstinence (withdrawal) | Maternal methadone maintenance |

| Sacrococcygeal teratoma (with hydrops) | In utero resection or catheter-directed vessel obliteration |

| Cardiac rhabdomyoma | Maternal sirolimus |

| Intrapericardial teratoma | Fetal surgery |

| CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing | Proof of concept in previable in vitro fertilized human embryos |

| Twin-twin transfusion syndrome | Repeated amniocentesis, yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser photocoagulation of shared vessels |

| Twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) syndrome | Cord occlusion, radiofrequency ablation |

| Multifetal gestation | Selective reduction |

| Neonatal hemochromatosis | Maternal IVIG |

| Aortic stenosis | In utero valvuloplasty |

* Drug of choice (may require percutaneous umbilical cord sampling and umbilical vein administration if hydrops is present). Most drug therapy is given to the mother, with subsequent placental passage to the fetus.

† Detailed fetal ultrasonography is needed to detect other anomalies; karyotype is also indicated.

‡ EXIT permits surgery and other procedures.

EXIT, Ex utero intrapartum treatment; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin; (?), possible but not proved efficacy.

Aneuploidy screening is offered to pregnant women in the first trimester or at midgestation to evaluate the risk for common aneuploidies such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and congenital malformations (e.g., abdominal wall or neural tube defects) known to cause elevations of various markers. A combination of these biochemical markers (including AFP, inhibin A, estriol, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, β–human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]) and US increases the positive predictive value (PPV) of these screening tests. Fetal DNA in maternal plasma and fetal cells circulating in maternal blood are potential noninvasive sources of material for prenatal genetic testing. This testing, however, is not diagnostic, and a positive test requires either amniocentesis or postnatal analysis to confirm the diagnosis. Nonetheless, fetal karyotyping by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma is another screening test that is very sensitive for the detection of Down syndrome, with a higher PPV than any other prenatal screening test for Down syndrome. Currently, however, the use of this technology is only advocated in pregnancies deemed at high risk for aneuploidy.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy, ACOG committee opinion no 640. Obstet Gynecol . 2015;126:e31–e37.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Microarrays and next-generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology, ACOG committee opinion no 682. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;128:e262–e268.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Prenatal diagnostic testing for genetic disorders, ACOG practice bulletin no 162. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;127:e108–e122.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for fetal aneuploidy, Practice bulletin no 163. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;127:e123–e137.

Barnes BT, Jelin AC, Gaur L, et al. Maternal sirolimus therapy for fetal cardiac rhabdomyomas. N Engl J Med . 2018;378(19):1844–1846.

Bianchi DW. From prenatal genomic diagnosis to fetal personalized medicine: progress and challenges. Nat Med . 2012;18:1041–1051.

Devaney SA, Palomaki GE, Scott JA, et al. Noninvasive fetal sex determination using cell-free fetal DNA. JAMA . 2011;306:627–636.

Fan HC, Gu W, Wanf J, et al. Non-invasive prenatal measurement of the fetal genome. Nature . 2012;489:326–332.

Freud LR, Tworetzky W. Fetal interventions for congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2016;28:156–162.

Ismaili K, Avni FE, Wissing KM, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of infants with mild and moderate fetal pyelectasis: validation of neonatal ultrasound as a screening tool to detect significant nephrouropathies. J Pediatr . 2004;144:759–765.

The Lancet. Genome editing: science, ethics, and public engagement. Lancet . 2017;390:625.

Morris RK, Malin GL, Quinlan-Jones E, et al. Percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunting versus conservative management for fetal lower urinary tract obstruction (PLUTO): a randomized trial. Lancet . 2013;382:1496–1506.

Nicolaides KH, Wright D, Poon C, et al. First-trimester contingent screening for trisomy 21 by biomarkers and maternal blood cell-free DNA testing. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol . 2013;42:41–50.

Norton ME, Jacobsson B, Swamy GK, et al. Cell-free DNA analysis for noninvasive examination of trisomy. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(17):1589–1597.

Reddy UM, Page GP, Saade GR, et al. Karyotype versus microarray testing for genetic abnormalities after stillbirth. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:2185–2193.

Rychik J, Khalek N, Gaynor JW, et al. Fetal intrapericardial teratoma: natural history and management including successful in utero surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2016;215(6):780e1–780e7.

Snyder MW, Simmons LE, Kitzman JO, et al. Copy number variation and false positive prenatal aneuploidy screening results. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(17):1639–1645.

Stenhouse EJ, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, et al. First trimester combined ultrasound and biochemical screening for Down syndrome in routine clinical practice. Prenat Diagn . 2004;24:774–780.

Talkowski ME, Ordulu Z, Pillalamarri V, et al. Clinical diagnosis by whole-genome sequencing of a prenatal sample. N Engl J Med . 2012;376:2226–2232.

Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:2175–2184.

Treatment and Prevention of Fetal Disease

Kristen R. Suhrie, Sammy M. Tabbah

See also Chapter 116 .

Management of a fetal disease depends on coordinated advances in diagnostic accuracy and knowledge of the disease's natural history; an understanding of fetal nutrition, pharmacology, immunology, and pathophysiology; the availability of specific active drugs that cross the placenta; and therapeutic procedures. Progress in providing specific treatments for accurately diagnosed diseases has improved with the advent of real-time ultrasonography, amniocentesis, and cordocentesis (see Tables 115.1 and 115.8 ).

The incidence of sensitization of Rh-negative women by Rh-positive fetuses has been reduced by prophylactic administration of Rh(D) immunoglobulin to mothers early in pregnancy and after each delivery or abortion, thus reducing the frequency of hemolytic disease in their subsequent offspring. Fetal erythroblastosis (see Chapter 124.2 ) may be accurately detected by fetal Doppler assessment of the peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery and treated with intrauterine transfusions of packed Rh-negative blood cells via the intraperitoneal or, more often, intraumbilical vein approach.

Pharmacologic approaches to fetal immaturity mostly revolve around the administration of antenatal corticosteroids to the mother to promote fetal production of surfactant with a resultant decrease in the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (see Chapter 122.3 ). Tocolytic agents have been demonstrated to prolong pregnancy to allow the administration of antenatal corticosteroids (48 hr); however, there is no proven benefit beyond this timeframe. Maternal administration of magnesium sulfate for fetal/neonatal neuroprotection is recommended in pregnancies deemed to be at risk of imminent delivery before 32 wk gestation in light of evidence demonstrating a reduction in frequency of cerebral palsy compared to those who did not receive this treatment.

Management of definitively diagnosed fetal genetic disease or congenital anomalies consists of multidisciplinary parental counseling. Rarely, high-dose vitamin therapy for a responsive inborn error of metabolism (e.g., biotin-dependent disorders) or fetal transfusion (with red blood cells or platelets) may be indicated. Fetal surgery is well-established treatment for certain conditions but remains a largely experimental approach to therapy for other conditions and is available only in a few, highly specialized perinatal centers (see Table 115.8 and Chapter 116 ). The nature of the defect and its consequences must be considered, as well as ethical implications for the fetus and the parents. Termination of pregnancy is also an option that should be discussed during the initial phases of counseling.

Folic acid supplementation decreases the incidence and recurrence of NTDs. Because the neural tube closes within the 1st 28 days of conception, periconceptional supplementation is needed for prevention. It is recommended that women without a prior history of a NTD ingest 400 µg/day of folic acid throughout their reproductive years. Women with a history of a prior pregnancy complicated by an NTD or a first-degree relative with an NTD should have preconceptional counseling and should ingest 4 mg/day of supplemental folic acid beginning at least 1 mo before conception. Fortification of cereal grain flour with folic acid is established policy in the United States and some other countries. The optimal concentration of folic acid in enriched grains is somewhat controversial. The incidence of NTD in the United States and other countries has decreased significantly since these public health initiatives were implemented. Use of some antiepileptic drugs (valproate, carbamazepine) during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of NTD. Women taking these medications should ingest 1-5 mg of folic acid daily in the preconception period.

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Neural tube defects, ACOG practice bulletin no 44. Obstet Gynecol . 2003;102:203–213.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection, ACOG committee opinion no 455. Obstet Gynecol . 2010;115:669–671.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Maternal–fetal intervention and fetal care centers, ACOG committee opinion no 501. Obstet Gynecol . 2011;118:405–410.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation, ACOG committee opinion no 677. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;128:e187–e194.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of preterm labor, ACOG practice bulletin no 171. Obstet Gynecol . 2016;128:e155–e164.