The Endocrine System

Nicole M. Sheanon, Louis J. Muglia

Endocrine emergencies in the newborn period are uncommon, but prompt identification and proper treatment are vital to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Pituitary dwarfism (growth hormone deficiency) is not usually apparent at birth, although male infants with panhypopituitarism may have neonatal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and micropenis. Conversely, primordial dwarfism manifests as in utero growth failure that continues postnatally, with length and weight suggestive of prematurity when born after a normal gestational period; otherwise, physical appearance is normal.

Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common preventable causes of developmental disability. Congenital screening followed by thyroid hormone replacement treatment started within 30 days after birth can normalize cognitive development in children with congenital hypothyroidism. Congenital hypothyroidism occurs in approximately 1/2,000 infants worldwide (see Chapter 581 ). Because most infants with congenital hypothyroidism are asymptomatic at birth, all states screen for it. Even though screening is standard in many countries, millions of infants born throughout the world are not screened for congenital hypothyroidism. Thyroid deficiency may also be apparent at birth in genetically determined cretinism and infants of mothers with hyperthyroidism during pregnancy treated with antithyroid medications (PTU). Infants with trisomy 21 have a higher incidence of congenital hypothyroidism and should be screened in the newborn period. Constipation, prolonged jaundice, goiter, lethargy, umbilical hernia, macroglossia, hypotonia with delayed reflexes, mottled skin, or cold extremities should suggest severe chronic hypothyroidism. Levothyroxine is the treatment of choice, with the goal of rapid normalization of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, thyrotropin) and free thyroxine (T4 ) to achieve the best outcome. Thyroid hormone treatment is aimed to maintain total thyroxine or free thyroxine in the upper half of the normal range during the 1st 3 yr after birth. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital thyroid hormone deficiency improve intellectual outcome and are facilitated by screening of all newborn infants for this deficiency. Newborn screening, with early referral to a pediatric endocrinologist for abnormal results, has improved early diagnosis and treatment of congenital hypothyroidism and improved intellectual outcome.

Transient hypothyroxinemia of prematurity is most common in ill and very premature infants. These infants have low thyroxine levels but normal levels of serum thyrotropin and other tests of the pituitary-hypothalamic axis indicating that they are probably chemically euthyroid. Trials of thyroid hormone replacement have reported no difference in developmental outcomes or other morbidities. Current practice is to follow thyroxine until levels normalize. Transient hyperthyroidism may occur at birth in infants of mothers with established or cured hyperthyroidism (e.g., Graves disease with positive TSH receptor–stimulating antibodies). See Chapter 584 for details on diagnosis and treatment.

Transient hypoparathyroidism may manifest as tetany or seizure of the newborn due to hypocalcemia and is associated with low levels of parathyroid hormone and hyperphosphatemia. Testing for DiGeorge syndrome should be considered. (see Chapter 589 ).

Subcutaneous fat necrosis can cause hypercalcemia and can occur after a traumatic birth. On examination, firm purple nodules can be appreciated on the trunk or extremities. An infant with hypercalcemia presents with irritability, vomiting, increased tone, poor weight gain, and constipation. Other causes of hypercalcemia in the newborn period are iatrogenic (excess calcium or vitamin D), maternal hypoparathyroidism, Williams syndrome, parathyroid hyperplasia, and idiopathic.

The adrenal glands are subject to numerous disturbances, which may become apparent and require lifesaving treatment during the neonatal period. Acute adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal failure are uncommon in the neonatal period. Risk factors include vaginal delivery, macrosomia, and fetal acidemia. The clinical presentation is often mild, with spontaneous regression. In neonates with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, an evaluation of cortisol production is required (high-dose ACTH stimulation test), and, if insufficient, treatment with glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids is indicated. Differentiation of unilateral adrenal hemorrhage from neuroblastoma is important. All patients should have sonographic and clinical follow-up to ensure resolution.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is suggested by vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, shock, ambiguous genitalia, or clitoral enlargement. Some infants have ambiguous genitalia and hypertension. In an infant with ambiguous genitalia, both pelvic and adrenal ultrasound can be performed to aid in diagnosis. An adrenal ultrasound showing bilateral, enlarged, coiled or cerebriform pattern is specific for CAH. Diagnosis is confirmed with an elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone level for gestational age. Because the condition is genetically determined, newborn siblings of patients with the salt-losing variety of adrenocortical hyperplasia should be closely observed for manifestations of adrenal insufficiency. Newborn screening and early diagnosis and therapy for this disorder may prevent severe salt wasting and adverse outcomes. Congenitally hypoplastic adrenal glands may also give rise to adrenal insufficiency during the 1st few wk of life (DAX1 mutation).

Disorders of sexual development can present in the newborn period with ambiguous or atypical genitalia, including bilateral cryptorchidism, hypospadias, micropenis, hypoplastic scrotum, or clitoromegaly. More than 20 genes have been associated with disorders of sexual development. The initial management should involve a multidisciplinary team (endocrinology, urology, genetics, and neonatology) and open communication with the family. Sex assignment and naming of the infant should be delayed until appropriate testing is completed. For more about disorders of sexual development, see Chapter 606 .

Female infants with webbing of the neck, lymphedema, hypoplasia of the nipples, cutis laxa, low hairline at the nape of the neck, low-set ears, high-arched palate, deformities of the nails, cubitus valgus, and other anomalies should be suspected of having Turner syndrome . Lymphedema of the hands or lower extremities can sometimes be the only indication. A karyotype can confirm diagnosis (see Chapter 604.1 ).

Transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (TNDM) is rare and typically presents on day 1 of life (see Chapter 607 ). It usually manifests as polyuria, dehydration, loss of weight, or acidosis in infants who are small for gestational age. The most common cause (70%) is a disruption of the imprinted locus at chromosome 6q24. A select group of patients with TNDM are at risk for recurrence of diabetes later in life.

Infants of Diabetic Mothers

Nicole M. Sheanon, Louis J. Muglia

Diabetes (type 1, type 2, or gestational) in pregnancy increases the risk of complications and adverse outcomes in the mother and the baby. Complications related to diabetes are milder in gestational vs pregestational (preexisting type 1 or type 2) diabetes. Pregnancy outcomes are correlated with onset, duration, and severity of maternal hyperglycemia. Prepregnancy planning and tight glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c ] <6.5%) is crucial in pregestational diabetes in order to achieve the best outcomes for the mother and the baby. The risk of diabetic embryopathy (neural tube defects, cardiac defects, caudal regression syndrome) and spontaneous abortions is highest in those with pregestational diabetes who have poor control (HbA1c >7%) in the first trimester. The risk of congenital malformations in gestational diabetes is only slightly increased compared to the general population, since the duration of diabetes is less and hyperglycemia occurs later in gestation (typically >25 wk).

Mothers with pregestational and gestational diabetes have a high incidence of complications during the pregnancy. Polyhydramnios, preeclampsia, preterm labor (induced and spontaneous), and chronic hypertension occur more frequently in mothers with diabetes. Accelerated fetal growth is also common, and 36–45% of infants of diabetic mothers (IDMs) are born large for gestational age (LGA). Restricted fetal growth is seen in mothers with pregestational diabetes and vascular disease, but it is less common. Fetal mortality rate is greater in both pregestational and gestational diabetic mothers than in nondiabetic mothers, but the rates have dropped precipitously over the years. Fetal loss throughout pregnancy is associated with poorly controlled maternal diabetes, especially diabetic ketoacidosis . The neonatal mortality rate of IDMs is >5 times that of infants of nondiabetic mothers and is higher at all gestational ages and in every birthweight for gestational age category. The rate is higher in women with pregestational diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and poor prenatal care.

Pathophysiology

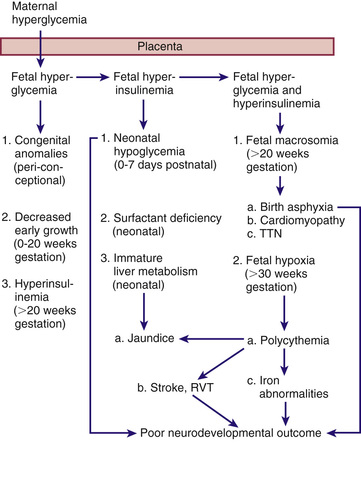

The probable pathogenic sequence is that maternal hyperglycemia causes fetal hyperglycemia , and the fetal pancreatic response leads to fetal hyperinsulinemia , or hyperinsulinism . It is important to recognize that while maternal glucose crosses the placenta, maternal and exogenous insulin dose not. Fetal hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia then cause increased hepatic glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis, accelerated lipogenesis, and augmented protein synthesis (Fig. 127.1 ). Related pathologic findings are hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the pancreatic β cells, increased weight of the placenta and infant organs (except the brain), myocardial hypertrophy, increased amount of cytoplasm in liver cells, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Hyperinsulinism and hyperglycemia produce fetal acidosis, which may result in an increased rate of stillbirth. Separation of the placenta at birth suddenly interrupts glucose infusion into the neonate without a proportional effect on hyperinsulinism, leading to hypoglycemia during the 1st few hr after birth. The risk of rebound hypoglycemia can be diminished by tight blood glucose control during labor and delivery.

Hyperinsulinemia has been documented in infants of mothers with pregestational and gestational diabetes. The infants of mothers with pregestational diabetes have significantly higher fasting plasma insulin levels than normal newborns, despite similar glucose levels, and respond to glucose with an abnormally prompt elevation in plasma insulin. After arginine administration, they also have an enhanced insulin response and increased disappearance rates of glucose compared with normal infants. In contrast, fasting glucose production and utilization rates are diminished in infants of mothers with gestational diabetes. Although hyperinsulinism is probably the main cause of hypoglycemia, the diminished epinephrine and glucagon responses that occur may be contributing factors. Infants of mothers with pregestational and gestational diabetes are at risk for neonatal hypoglycemia in the 1st hours of life, with an increased risk in both large- and small-for-gestational-age infants. Aggressive screening and treatment is recommended as outlined later.

Clinical Manifestations

Infants of mothers with pregestational diabetes and those of mothers with gestational diabetes often bear a surprising resemblance to each other (Fig. 127.2 ). They tend to be large and plump as a result of increased body fat and enlarged viscera, with puffy, plethoric facies resembling that of patients who have been receiving corticosteroids. These infants may also be of normal birthweight if diabetes is well controlled; or low birthweight if they are delivered before term or if their mothers have associated diabetic vascular disease. Infants that are macrosomic or LGA are at high risk of birth trauma (brachial plexus injury) and birth asphyxia because of not only their large size but also their decreased ability to tolerate stress, especially if they have cardiomyopathy and other effects of fetal hyperinsulinemia (Table 127.1 ).

Table 127.1

Morbidity in Infants of Diabetic Mothers

From Devaskar SU, Garg M: Disorders of carbohydrate metabolism in the neonate. In Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, Walsh MC, editors: Fanaroff & Martin's neonatal-perinatal medicine, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2015, Elsevier (Box 95-3).

Hypoglycemia develops in approximately 25–50% of infants of mothers with pregestational diabetes and 15–25% of infants of mothers with gestational diabetes, but only a small percentage of these infants become symptomatic. The probability that hypoglycemia will develop in such infants increases with higher cord or maternal fasting blood glucose levels. The nadir in an infant's blood glucose concentration is usually reached between 1 and 3 hr of age. Hypoglycemia can persist for 72 hr and in rare cases last up to 7 days. Frequent feedings can be used to treat the hypoglycemia, but some infants require intravenous (IV) dextrose.

The infants tend to be jittery, tremulous, and hyperexcitable during the 1st 3 days after birth, although hypotonia, lethargy, and poor sucking may also occur. Early appearance of these signs is more likely to be related to hypoglycemia but can also be caused by hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, which also occur in the 1st 24-72 hr of life due to delayed response of the parathormone system. Perinatal asphyxia is associated with increased irritability and also increases the risk of hypoglycemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia.

Tachypnea develops in many IDMs during the 1st 2 days after birth and may be a manifestation of hypoglycemia, hypothermia, polycythemia, cardiac failure, transient tachypnea, or cerebral edema from birth trauma or asphyxia. IDMs have a higher incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) than do infants of nondiabetic mothers born at comparable gestational age. The greater incidence is possibly related to an antagonistic effect of insulin on stimulation of surfactant synthesis by cortisol, leading to a delay in lung maturation. Polycythemia often occurs with RDS as they are both a result of fetal hyperinsulinism.

Cardiomegaly is common (30%), and heart failure occurs in 5-10% of IDMs. Interventricular septal hypertrophy may occur and may manifest as transient idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. This is thought to result from chronic hyperglycemia and chronic hyperinsulinism leading to glycogen loading in the heart. Inotropic agents worsen the obstruction and are contraindicated. β-Adrenergic blockers have been shown to relieve the obstruction, but ultimately the condition resolves spontaneously over time.

Acute neurologic abnormalities (lethargy, irritability, poor feeding) can be seen immediately after birth and the cause elucidated by the timing of symptoms, as previously discussed (hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, or birth asphyxia). The symptoms will resolve with treatment of the underlying cause but may persist for weeks if caused by birth asphyxia. Neurologic development and ossification centers tend to be immature and to correlate with brain size (which is not increased) and gestational age rather than total body weight in infants of mothers with gestational and pregestational diabetes. In addition, IDMs have an increased incidence of hyperbilirubinemia, polycythemia, iron deficiency, and renal vein thrombosis. Renal vein thrombosis should be suspected in the infant with a flank mass, hematuria, and thrombocytopenia.

There is a 4-fold increase in congenital anomalies in infants of mothers with pregestational diabetes, and the risk varies with HbA1c during the first trimester when organogenesis occurs. The recommended goal for periconceptual HbA1c is <6.5%. Although the risk of congenital malformations increases with increasing HbA1c levels, there may still be an increased risk in the therapeutic goal range. Congenital anomalies of the central nervous system and cardiovascular system are most common, including failure of neural tube closure (encephalocele, meningomyelocele, and anencephaly), transposition of great vessels, ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), hypoplastic left heart, aortic stenosis, and coarctation of the aorta. Other, less common anomalies include caudal regression syndrome, intestinal atresia, renal agenesis, hydronephrosis, and cystic kidneys. Small left colon syndrome is a rare anomaly that develops in the second and third trimester because of rapid fluctuations in maternal and therefore fetal glucose, leading to impaired intestinal motility and subsequent intestinal growth. Prenatal ultrasound and a thorough newborn physical examination will identify most of these anomalies. High clinical suspicion and a good prenatal history will help identify needed screening for subtle anomalies.

Treatment

Preventive treatment of IDMs should be initiated before birth by means of preconception and frequent prenatal evaluations of all women with preexisting diabetes and pregnant women with gestational diabetes. This involves evaluation of fetal maturity, biophysical profile, Doppler velocimetry, and planning of the delivery of IDMs in hospitals where expert obstetric and pediatric care is continuously available. Preconception glucose control reduces the risk of anomalies and other adverse outcomes in women with pregestational diabetes, and glucose control during labor reduces the incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia. Women with type 1 diabetes who have tight glucose control during pregnancy (average daily glucose levels <95 mg/dL) deliver infants with birthweight and anthropomorphic features similar to those of infants of nondiabetic mothers. Treatment of gestational diabetes (diet, glucose monitoring, metformin, and insulin therapy as needed) decreases the rate of serious perinatal outcomes (death, shoulder dystocia, bone fracture, or nerve palsy). Women with gestational diabetes may also be treated successfully with glyburide , which may not cross the placenta. In these mothers, the incidence of macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia is similar to that in mothers with insulin-treated gestational diabetes. Women with diabetes can begin to express breast milk before the birth of the baby (≥36 wk gestational age); this will provide an immediate supply of milk to prevent hypoglycemia.

Regardless of size, IDMs should initially receive close observation and care (Fig. 127.3 ). Infants should initiate feedings within 1 hr after birth. A screening glucose test should be performed within 30 min of the first feed. Transient hypoglycemia is common during the 1st 1-3 hr after birth and may be part of normal adaptation to extrauterine life. The target plasma glucose concentration is ≥40 mg/dL before feeds in the 1st 48 hr of life. Clinicians need to assess the overall metabolic and physiologic status, considering these in the management of hypoglycemia. Treatment is indicated if the plasma glucose is <47 mg/dL. Feeding is the initial treatment for asymptomatic hypoglycemia. Oral or gavage feeding with breast milk or formula can be given. An alternative is prophylactic use of dextrose gel, although early feedings may be equally effective. Recurrent hypoglycemia can be treated with repeat feedings or IV glucose as needed. Infants with persistent (and unresponsive to oral therapy) glucose levels <25 mg/dL during the 1st 4 hr after birth and <35 mg/dL at 4-24 hr after birth should be treated with IV glucose, especially if symptomatic. A small bolus of 200 mg/kg of dextrose (2 mL/kg of 10% dextrose) should be administered to infants with plasma glucose below these limits. The small bolus should be followed by a continuous IV glucose infusion to avoid hypoglycemia. If question arises about an infant's ability to tolerate oral feeding, a continuous peripheral IV infusion at a rate of 4-8 mg/kg/min should be given. Neurologic symptoms of hypoglycemia must be treated with IV glucose. Bolus injections of hypertonic (25%) glucose should be avoided because they may cause further hyperinsulinemia and potentially produce rebound hypoglycemia (see Chapter 111 ). For treatment of hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, see Chapters 119.4 and 119.5 ; for RDS treatment, see Chapter 122.3 ; and for treatment of polycythemia, see Chapter 124.3 .

Prognosis

The subsequent incidence of diabetes mellitus in IDMs is higher than that in the general population because of genetic susceptibility in all types of diabetes. Infants of mothers with either pregestational diabetes or gestational diabetes are at risk for obesity and impaired glucose metabolism in later life as a result of intrauterine exposure to hyperglycemia. Disagreement persists about whether IDMs have a slightly increased risk of impaired intellectual development because of the many confounding factors (e.g., parental education, maternal age, neonatal complications). In general, the outcomes have improved over the last several decades due to increased awareness, screening, and improved prenatal care for pregnant women with diabetes.

Bibliography

Adamkin DH. Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatrics . 2011;127:575–579.

Alsweiler JM, Harding JE, Bloomfield FH. Tight glycemic control with insulin in hyperglycemic preterm babies: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics . 2012;129:639–647.

Bietsy LM, Egan AM, Dunne F, et al. Planned birth at or near term for improving health outcomes for pregnant women with gestational diabetes and their infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2018;(1) [CD012910].

Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Australian carbohydrate intolerance study in pregnant women (ACHOIS) trial group: effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med . 2005;352:2477–2486.

Feig DS, Donovan LE, Corcoy R, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes (CONCEPTT): a multicenter international randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2017;390:2347–2358.

Forster DA, Moorhead AM, Jacobs SE, et al. Advising women with diabetes in pregnancy to express breast milk in late pregnancy (diabetes and antenatal milk expressing [DAME]): a multicenter, unblinded, randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2017;389:2204–2213.

Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr . 2012;161:787–791.

Hegarty JE, Harding JE, Gamble GD, et al. Prophylactic oral dextrose gel for newborn babies at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia: a randomized controlled dose-finding trial (the Pre-hPOD study). PLoS Med . 2016;13(10):e1002155.

Ludvigsson JF, Neovius M, Soderling J, et al. Periconception glycaemic control in women with type 1 diabetes and risk of major birth defects: population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ . 2018;362:k2638.

Mathiesen ER, Ringholm L, Damm P. Stillbirth in diabetic pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol . 2011;25:105–111.

Nold JL, Georgieff MK. Infants of diabetic mothers. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2004;51:619–637.

Rozance PJ, Hay WW Jr. Neonatal hypoglycemia—answers, but more questions. J Pediatr . 2012;161:775–776.

Thornton PS, Stanley CA, et al. Recommendations from the pediatric endocrine society for evaluation and management of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. J Pediatr . 2015;167:238–245.

Tin W, Brunskill G, Kelly T, et al. 15-year follow-up of recurrent “hypoglycemia” in preterm infants. Pediatrics . 2012;130:e1497–e1503.

Weston PJ, Harris DL, Battin M, et al. Oral dextrose gel for the treatment of hypoglycaemia in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;(5) [CD011027].