Hypothyroidism

Ari J. Wassner, Jessica R. Smith

Hypothyroidism is a state of insufficient circulating thyroid hormone. Hypothyroidism almost always results from deficient production of thyroid hormone caused either by a defect in the thyroid gland itself (primary hypothyroidism) or a by reduced thyrotropin (TSH) stimulation (central or secondary hypothyroidism; Table 581.1 ). Hypothyroidism may be present from birth (congenital) or may be acquired, although some acquired cases are due to congenital defects in which the onset of hypothyroidism is delayed.

Table 581.1

Etiologic Classification of Congenital Hypothyroidism

ACTH , Adrenocorticotropic hormone; FSH , follicle-stimulating hormone; GH , growth hormone; LH , luteinizing hormone; TRH , thyrotropin-releasing hormone.

Congenital Hypothyroidism

Most cases of congenital hypothyroidism are caused by abnormal formation of the thyroid gland (thyroid dysgenesis), and a minority are due to inborn errors of thyroid hormone synthesis (dyshormonogenesis) or other rarer causes. Most infants with congenital hypothyroidism are detected by newborn screening programs in the 1st few wk after birth, before any obvious clinical signs or symptoms develop. In areas with no screening program, severely affected infants usually manifest features within the 1st wk of life, but in infants with milder hypothyroidism, clinical manifestations may not be evident for months.

Epidemiology

The incidence of congenital hypothyroidism based on nationwide programs for neonatal screening was initially reported at 1 in 4,000 infants worldwide. Over the past few decades, the apparent incidence has increased to about 1 in 2,000, primarily because more stringent screening algorithms have resulted in the detection of milder cases of hypothyroidism. Studies from the United States report that the incidence is lower in African Americans and higher in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and Native Americans as compared with white infants.

Etiology

See Table 581.1 .

Primary Hypothyroidism

Thyroid Dysgenesis.

Thyroid dysgenesis is the most common cause of permanent congenital hypothyroidism, accounting for 80–85% of cases. In approximately 33% of cases of dysgenesis, no thyroid tissue is present (agenesis ). In the other 66% of infants, rudiments of thyroid tissue are present, either in the normal position (hypoplasia ) or in an ectopic location anywhere along the embryologic path of descent of the thyroid, from the base of the tongue (lingual thyroid) to the normal position. Thyroid dysgenesis occurs twice as commonly in females as in males.

The cause of thyroid dysgenesis is largely unknown. Thyroid dysgenesis is usually sporadic, but familial cases have been reported. Thyroid developmental anomalies, such as thyroglossal duct cysts and thyroid hemiagenesis, are present in 8–10% of first-degree relatives of infants with thyroid dysgenesis. However, whether this represents a true genetic susceptibility is unclear, particularly given the high degree of discordance for thyroid dysgenesis among monozygotic twins.

About 2–5% of cases of thyroid dysgenesis are caused by genetic defects in 1 of several transcription factors important for thyroid morphogenesis and differentiation, including NKX2.1 (formerly TTF1), FOXE1 (formerly TTF2), and PAX8. NKX2.1 is expressed in the thyroid, lung, and central nervous system, and recessive mutations in NKX2-1 cause thyroid dysgenesis, respiratory distress, and neurologic problems (including chorea and ataxia) despite early thyroid hormone treatment. Recessive mutations in FOXE1 cause thyroid dysgenesis, spiky or curly hair, cleft palate, and sometimes choanal atresia and bifid epiglottis (Bamforth-Lazarus syndrome ). PAX8 is expressed in the thyroid and kidney, and dominant PAX8 mutations are associated with thyroid dysgenesis and kidney and ureteral malformations.

Inactivating mutations in the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) have been described in patients with congenital hypothyroidism, including thyroid agenesis or hypoplasia. TSHR mutations may be homozygous, or they may be heterozygous with or without a concurrent mutation in another congenital hypothyroidism gene (such as DUOX2 or TG ; see later). Infants with a severe TSHR defect have elevated TSH levels and are detected by newborn screening, whereas patients with a mild defect may remain euthyroid without treatment.

Congenital hypothyroidism can also occur in infants with pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a. These patients have somatic inactivating mutations of the G-protein stimulatory α-subunit Gs α (GNAS), leading to impaired signaling of the TSH receptor (see Chapter 590 ).

Defects in Thyroid Hormone Synthesis (Dyshormonogenesis).

A variety of defects in the biosynthesis of thyroid hormone account for 15% of cases of permanent congenital hypothyroidism detected by neonatal screening programs (1 in 30,000-50,000 live births). These defects are usually transmitted in an autosomal recessive manner. Because the thyroid gland responds normally to elevated TSH stimulation, a goiter is almost always present. When the synthetic defect is incomplete, the onset of hypothyroidism may be delayed for years.

Defective Iodide Transport.

Defective iodide uptake is very rare and is caused by mutations in the sodium–iodide symporter (NIS) responsible for concentrating iodide in the thyroid gland. Among the cases reported, it has been found in 9 related infants of the Hutterite sect, and approximately 50% of the cases are from Japan. Consanguinity is a factor in approximately 30% of cases.

In the past, clinical hypothyroidism with or without a goiter often developed in the 1st few mo of life, and the condition has been detected in neonatal screening programs. However, in Japan the onset of goiter and hypothyroidism may be delayed past 10 yr of age, perhaps because of the very high iodine content of the Japanese diet.

In this disorder, the mechanism for concentrating iodide is defective in the thyroid and salivary glands. In contrast to other defects of thyroid hormone synthesis, uptake of radioiodine and pertechnetate is low. A reduced saliva:serum ratio of 123 I will support the diagnosis, which is confirmed by finding a mutation in the NIS gene. This condition responds to treatment with large doses of potassium iodide, but treatment with levothyroxine is preferable.

Pendred syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder composed of sensorineural deafness and goiter. Pendred syndrome is caused by a mutation in the chloride–iodide transport protein pendrin (SLC26A4) that is expressed in the thyroid gland and the cochlea. Pendrin allows transport of iodide across the apical membrane of the follicular cell into the colloid where it undergoes organification and incorporation into the tyrosine residues on thyroglobulin. Patients with a mutation in the pendrin gene have impaired iodide organification and a positive perchlorate discharge test. Mutations in pendrin are a relatively common genetic cause of sensorineural deafness, but some patients diagnosed due to their hearing disorder have no goiter or thyroid dysfunction. This finding has fueled speculation that pendrin is not the sole apical iodine transporter in the thyroid, but to date no other such transporter has been identified.

Defects of Iodine Organification.

Defects of iodine organification are the most common type of thyroid hormone synthetic defects. After iodide is taken up by the thyroid, it is rapidly oxidized to reactive iodine, which is then incorporated into tyrosine residues on thyroglobulin. These reactions are catalyzed by the critical enzyme thyroperoxidase (TPO) and requires locally generated H2 O2 and hematin (a cofactor). Defects can occur in any of these components, and there is considerable clinical and biochemical heterogeneity. In the Dutch neonatal screening program, 23 infants were found with a complete organification defect (1 in 60,000 live births), but its prevalence in other areas is unknown. A characteristic finding in patients with this defect is a marked discharge of thyroid radioactivity when perchlorate or thiocyanate is administered 2 hr after administration of a test dose of radioiodine (perchlorate discharge of 40–90% of radioiodine compared with <10% in normal persons). Numerous mutations in the TPO gene have been reported in children with congenital hypothyroidism.

The enzyme dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2) produces the H2 O2 required for iodide organification. DUOX2 mutations can cause permanent or transient congenital hypothyroidism. Previously, it was thought that monoallelic DUOX2 mutations cause transient disease and biallelic mutations cause permanent disease, but the reverse has been observed in some cases, and this relationship remains unclear. DUOX2 mutations have been reported in 15–40% of patients with apparent dyshormonogenesis, with mutation rates as high as 50–60% in studies from China and South Korea. Dual oxidase maturation factor 2 (DUOXA2) is required to express DUOX2 enzymatic activity, and recessive mutations in DUOXA2 are a rare cause of congenital hypothyroidism.

Defects of Thyroglobulin Synthesis.

Defects of thyroglobulin synthesis are characterized by congenital hypothyroidism with goiter and absent or low levels of circulating thyroglobulin. More than 40 different mutations in the thyroglobulin gene (TG) have been described.

Defects in Deiodination.

Monoiodotyrosine and diiodotyrosine are normally released from thyroglobulin along with thyroxine (T4 ) and triiodothyronine (T3 ). The IYD gene (formerly DEHAL1 ) encodes the thyroidal enzyme iodotyrosine deiodinase, which deiodinates these intermediates and allows the liberated iodide to be recycled into thyroid hormone synthesis. Urinary excretion of monoiodotyrosine and diiodotyrosine in patients with rare mutations in IYD rapidly causes them to develop severe iodine deficiency, leading to hypothyroidism and goiter that may present soon after birth or may be delayed for months or years.

Defects in Thyroid Hormone Transport.

Passage of thyroid hormone into the cell is facilitated by specific plasma membrane transporters. Mutations in the transporter MCT8 (SLC16A2), located on the X-chromosome, impair the movement of T4 and T3 into cells. This leads to severe neurologic manifestations including profound developmental delay, reduced muscle mass, dysarthria, athetoid movements, and hypotonia that evolves to spastic paraplegia (Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome ). This syndrome is also characterized by elevated serum T3 levels but low serum T4 levels and normal or mildly elevated serum TSH levels.

Thyrotropin Receptor–Blocking Antibodies.

Maternal TSHR–blocking antibodies (TRBAbs) cause about 2% of cases of congenital hypothyroidism detected by neonatal screening programs (1 in 50,000-100,000 infants). Transplacentally acquired maternal TRBAb inhibits binding of TSH to its receptor in the neonate. This condition should be suspected whenever there is a history of maternal autoimmune thyroid disease, including chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis or Graves disease, maternal hypothyroidism, or transient congenital hypothyroidism in previous siblings. However, TRBAbs can cause congenital hypothyroidism in the absence of any maternal history. When suspected, maternal levels of TRBAb (measured as thyrotropin-binding inhibitory immunoglobulin [TBII]) should be measured during pregnancy. Affected infants and their mothers also can have TSHR–stimulating antibodies and TPO antibodies. Ultrasonography will typically demonstrate a normally positioned but small thyroid gland; however, thyroid tissue will often not be detected by scintigraphy with technetium pertechnetate or 123 I because impaired TSHR function suppresses thyroidal iodine uptake. Serum thyroglobulin levels are also low. Treatment with levothyroxine is required initially, but remission of hypothyroidism occurs in approximately 3-6 mo, once the TRBAb are cleared from the infant circulation. Correct diagnosis of this cause of congenital hypothyroidism prevents unnecessary protracted treatment and alerts the clinician to possible recurrences in future pregnancies. The prognosis is generally favorable, but developmental delay may occur in patients whose mothers had unsuspected (and untreated) hypothyroidism caused by TRBAb during pregnancy.

Radioiodine Administration.

Neonatal hypothyroidism can occur when radioiodine is administered as treatment for Graves disease or thyroid cancer to a mother during (a usually unrecognized) pregnancy. The fetal thyroid is capable of trapping iodide by 70-75 days of gestation. Therefore a pregnancy test must be performed in any woman of childbearing age before 131 I is given, regardless of menstrual history or reported history of contraception. Administration of radioactive iodine to lactating women is also contraindicated because it is excreted in breast milk.

Iodine Exposure.

Congenital hypothyroidism can result from fetal exposure to excessive iodides. Perinatal exposure can occur with the use of iodine antiseptic to prepare the skin for caesarian section or to paint the cervix before delivery. Hypothyroidism has also been reported in exclusively breastfed infants born to mothers who consume large amounts of iodine daily (up to 12 mg) in the form of nutritional supplements or who consume large quantities of iodine-rich seaweed. Iodine-induced hypothyroidism is transient once the exposure is discontinued and must not be mistaken for other forms of congenital hypothyroidism. In the neonate, especially in those of low birthweight (LBW), topical iodine-containing antiseptics used in nurseries and perioperatively can cause transient hypothyroidism, which may be detected by newborn screening tests. In older children, excess iodine may be present proprietary preparations used to treat asthma or in amiodarone, an antiarrhythmic drug with high iodine content. In most of these instances, goiter is present (see Chapter 583 ).

Iodine Deficiency (Endemic Goiter).

See Chapter 583.3 .

Iodine deficiency or endemic goiter is the most common cause of congenital hypothyroidism worldwide. The recommended intake of iodine in adults is 150 µg daily, increasing to 220 µg daily during pregnancy to allow for fetal iodine requirements. Despite efforts at universal iodization of salt in many countries, economic, political, and practical obstacles continue to prevent realization of this goal. Although the U.S. population is generally iodine sufficient, approximately 15% of women of reproductive age are iodine deficient. Borderline iodine deficiency is more likely to cause problems in preterm infants who depend on a maternal source of iodine for normal thyroid hormone production and who often receive insufficient dietary iodine from common preterm infant formulas that are low in iodine.

Central (Secondary) Hypothyroidism

Thyrotropin and Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Deficiency.

Deficiency of TSH and central hypothyroidism can occur in any condition associated with developmental defects of the pituitary or hypothalamus (see Chapter 573 ). Central hypothyroidism occurs in 1 in 16,000-30,000 infants, but many cases are not detected by neonatal screening, particularly because many screening programs are designed to detect only primary hypothyroidism. The majority (75%) of affected infants have multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies and may present with hypoglycemia, persistent jaundice, micropenis or cryptorchidism (in males), or midline defects such as midline cleft lip or palate or midface hypoplasia.

Congenital TSH deficiency may be caused by mutations in genes coding for transcription factors essential to pituitary development or thyrotroph cell differentiation. POU1F1 mutations cause deficiency of TSH, growth hormone, and prolactin. Patients with PROP1 mutations also have deficiency of TSH, growth hormone, and prolactin, as well as deficiency of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone and variable deficiency of adrenocorticotropic hormone. HESX1 mutations are associated with TSH, growth hormone, prolactin, and adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiencies and are found in some patients with optic nerve hypoplasia (septo-optic dysplasia syndrome; see Chapter 609 ).

Isolated congenital deficiency of TSH is rare. The most common genetic cause is a mutation in IGSF1 , a gene of unclear function, resulting in a syndrome of X-linked congenital central hypothyroidism and macroorchidism. Prolactin deficiency is usually present, and some patients also have growth hormone deficiency. Patients with mutations in the gene encoding the TSH β-subunit (TSHB) have central hypothyroidism with very low TSH levels, although in some cases TSH levels are normal or even elevated. In some of these cases, levels of the TSH α-subunit are elevated. Mutations in the gene for the TRH receptor (TRHR) is a very rare cause of congenital central hypothyroidism reported in a few families. In this condition, both TSH and prolactin fail to respond to TRH stimulation.

Thyroid Function in Preterm and Low Birthweight Infants

Postnatal thyroid function in preterm and LBW infants is qualitatively similar but quantitatively reduced compared with that of term infants. The cord blood T4 concentration is decreased in proportion to gestational age and birthweight. The postnatal TSH surge is reduced, and very premature or very LBW infants experience a decrease in serum T4 in the 1st wk of life, in contrast to term infants in whom T4 increases during this time. The serum T4 gradually increases to the range observed in term infants by about 6 wk of life. However, serum free T4 concentrations seem less affected than total T4 , and free T4 levels may be normal when measured by the gold standard technique of equilibrium dialysis. Preterm and LBW infants also have a higher incidence of delayed TSH elevation and apparent transient primary hypothyroidism. Mechanisms underlying these changes in thyroid function in preterm and LBW infants may include immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis; loss of the maternal contribution of thyroid hormone normally present in the 3rd trimester; severe illness and complications of prematurity; and exposure to medications that can affect thyroid function (e.g., dopamine and glucocorticoids).

Clinical Manifestations

Before neonatal screening programs, congenital hypothyroidism was rarely recognized in the newborn because most affected infants are asymptomatic at birth, even if there is complete agenesis of the thyroid gland. This is due to transplacental passage of maternal T4 , which provides fetal levels that are approximately 33% of normal at birth. Despite this maternal contribution of T4 , infants with primary hypothyroidism have elevated TSH levels and most have low T4 levels, and so will be identified by newborn screening programs.

Because symptoms are usually not present at birth, the clinician depends on neonatal screening tests for the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism . However, some infants escape newborn screening, and laboratory errors occur, so pediatricians must still be alert for symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism if they develop. Birthweight and length are normal, but head size may be slightly increased because of myxedema of the brain. The anterior and posterior fontanels are open widely, and the presence of this sign at birth may be a clue to early recognition of congenital hypothyroidism (only 3% of normal newborns have a posterior fontanel wider than 0.5 cm). Prolonged jaundice (indirect hyperbilirubinemia) may be present due to delayed maturation of hepatic glucuronide conjugation. Affected infants cry little, sleep much, have poor appetites, and are generally sluggish. Feeding difficulties, especially sluggishness, lack of interest, somnolence, and choking spells during nursing, may be present during the 1st mo of life. Respiratory difficulties, partly caused by macroglossia, include apneic episodes, noisy respirations, and nasal obstruction. There may be constipation that does not usually respond to treatment. The abdomen is large, and an umbilical hernia is often present. The temperature may be subnormal (often <35°C/95°F), and the skin may be cold and mottled, particularly on the extremities. Edema of the genitals and extremities may be present. The pulse is slow, and heart murmurs, cardiomegaly, and asymptomatic pericardial effusion are common. Macrocytic anemia is often present. Because symptoms appear gradually and may be nonspecific, the clinical diagnosis of neonatal hypothyroidism is often delayed.

Approximately 10% of infants with congenital hypothyroidism have associated congenital anomalies. Cardiac anomalies are most common, but anomalies of the nervous system and eye have also been reported. Infants with congenital hypothyroidism may have associated hearing loss. Mutations in certain genes involved in thyroid gland development result in congenital hypothyroidism with other syndromic features (Table 581.2 ). Mutations in NKX2-1 are characterized by congenital hypothyroidism, respiratory distress, and ataxia or choreoathetosis. Mutations in FOXE1 present with congenital hypothyroidism, spiky or curly hair, and cleft palate. Mutations in PAX8 cause congenital hypothyroidism and genitourinary anomalies, including renal agenesis.

Table 581.2

FOXE-1 , Forkhead box E1; GLIS3 , GLIS family zinc finger 3; PAX-8 , paired box 8; TSHR , thyroid stimulating hormone receptor; TTF-1 , transcription termination factor 1; TTF-2 , transcription termination factor 2.

From Kim G, Nandi-Munshi D, Diblasi CC: Disorders of the thyroid gland. In Gleason CA, Juul SE, editors: Avery's diseases of the newborn , ed 10, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier. Table 98.3, p 1396.

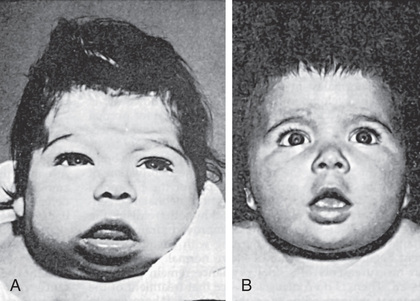

If congenital hypothyroidism goes undetected and untreated, the clinical manifestations progress. Delay of physical and mental development becomes more severe over time, and by 3-6 mo of age the clinical picture is fully developed (Fig. 581.1 ). When there is only partial deficiency of thyroid hormone, the symptoms may be milder and their onset delayed. Although breast milk contains significant amounts of thyroid hormones, particularly T3 , it is inadequate to protect the breastfed infant with congenital hypothyroidism, and it has no effect on neonatal thyroid screening tests.

In the patient with untreated congenital hypothyroidism, growth will be stunted, extremities are short, and head size is normal or increased. The anterior fontanel is large and the posterior fontanel may remain open. The eyes appear far apart, and the bridge of the broad nose is depressed. The palpebral fissures are narrow and the eyelids are swollen. The mouth is kept open, and the thick, broad tongue protrudes. Dentition will be delayed. The neck is short and thick, and there may be deposits of fat above the clavicles and between the neck and shoulders. The hands are broad and the fingers are short. The skin is dry and scaly, and there is little perspiration. Myxedema occurs particularly in the skin of the eyelids, the back of the hands, and the external genitalia. The skin shows general pallor with a sallow complexion. Carotenemia can cause a yellow discoloration of the skin, but the sclerae remain white. The scalp is thickened, and the hair is coarse, brittle, and scanty. The hairline reaches far down on the forehead, which usually appears wrinkled, especially when the infant cries.

Development is usually delayed. Hypothyroid infants appear lethargic and are late in acquiring gross and fine motor skills. The voice is hoarse, and they do not learn to talk. The degree of physical and intellectual delay increases with age. Sexual maturation may be delayed or even absent.

The muscles are usually hypotonic, but in rare instances generalized muscular pseudohypertrophy occurs (Kocher-Debré-Sémélaigne syndrome). Affected older children can have an athletic appearance because of pseudohypertrophy, particularly in the calf muscles. Its pathogenesis is unknown; nonspecific histochemical and ultrastructural changes seen on muscle biopsy return to normal with treatment. Males are more prone to development of the syndrome, which has been observed in siblings born from a consanguineous mating. Affected patients have hypothyroidism of longer duration and severity.

Some infants with mild congenital hypothyroidism have normal thyroid function at birth and are not identified by newborn screening programs. In particular, some children with ectopic thyroid tissue (lingual, sublingual, subhyoid) produce adequate amounts of thyroid hormone for a variable length of time (even years) until the abnormal thyroid tissue fails. Affected children come to clinical attention because of a growing mass at the base of the tongue or in the midline of the neck, usually at the level of the hyoid. Occasionally, thyroid ectopy is associated with thyroglossal duct cysts . Surgical removal of ectopic thyroid tissue from a euthyroid patient usually results in hypothyroidism, because most such patients have no other thyroid tissue.

Laboratory Findings

In countries where newborn screening is performed, this is the most important method for identifying infants with congenital hypothyroidism. Blood obtained by heel-prick between 1 and 5 days of life is placed on a filter paper card and sent to a central screening laboratory. Most screening programs measure the level of TSH, which detects infants with primary hypothyroidism, including some with milder disease in whom TSH but T4 is normal. However, this approach may not detect rarer disorders such as central hypothyroidism or congenital primary hypothyroidism with delayed TSH elevation. Some screening programs begin by measuring levels of T4 , followed by reflex measurement of TSH when the T4 is low. This approach identifies infants with primary hypothyroidism, some infants with central hypothyroidism or delayed TSH elevation, and also infants with thyroxine-binding globulin deficiency (a benign variant). All newborn screening results should be interpreted based on the normal range of values for the age of the patient, particularly in the 1st wk of life (Table 581.3 ). Regardless of the approach used for screening, some infants escape detection because of technical or human errors, and clinicians must remain vigilant for clinical manifestations of hypothyroidism.

Table 581.3

| AGE | U.S. REFERENCE VALUE | CONVERSION FACTOR | SI REFERENCE VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| THYROID THYROGLOBULIN, SERUM | |||

| Cord blood | 14.7-101.1 ng/mL | ×1 | 14.7-101.1 µg/L |

| Birth to 35 mo | 10.6-92.0 ng/mL | ×1 | 10.6-92.0 µg/L |

| 3-11 yr | 5.6-41.9 ng/mL | ×1 | 5.6-41.9 µg/L |

| 12-17 yr | 2.7-21.9 ng/mL | ×1 | 2.7-21.9 µg/L |

| THYROID-STIMULATING HORMONE, SERUM | |||

| Premature Infants (28-36 wk) | |||

| 1st wk of life | 0.7-27.0 mIU/L | ×1 | 0.7-27.0 mIU/L |

| Term Infants | |||

| Birth to 4 days | 1.0-17.6 mIU/L | ×1 | 1.0-17.6 mIU/L |

| 2-20 wk | 0.6-5.6 mIU/L | ×1 | 0.6-5.6 mIU/L |

| 5 mo-20 yr | 0.5-5.5 mIU/L | ×1 | 0.5-5.5 mIU/L |

| THYROXINE-BINDING GLOBULIN, SERUM | |||

| Cord blood | 1.4-9.4 mg/dL | ×10 | 14-94 mg/L |

| 1-4 wk | 1.0-9.0 mg/dL | ×10 | 10-90 mg/L |

| 1-12 mo | 2.0-7.6 mg/dL | ×10 | 20-76 mg/L |

| 1-5 yr | 2.9-5.4 mg/dL | ×10 | 29-54 mg/L |

| 5-10 yr | 2.5-5.0 mg/dL | ×10 | 25-50 mg/L |

| 10-15 yr | 2.1-4.6 mg/dL | ×10 | 21-46 mg/L |

| Adult | 1.5-3.4 mg/dL | ×10 | 15-34 mg/L |

| THYROXINE, TOTAL, SERUM | |||

| Full-Term Infants | |||

| 1-3 days | 8.2-19.9 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 106-256 nmol/L |

| 1 wk | 6.0-15.9 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 77-205 nmol/L |

| 1-12 mo | 6.1-14.9 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 79-192 nmol/L |

| Prepubertal Children | |||

| 1-3 yr | 6.8-13.5 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 88-174 nmol/L |

| 3-10 yr | 5.5-12.8 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 71-165 nmol/L |

| Pubertal Children and Adults | |||

| >10 yr | 4.2-13.0 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 54-167 nmol/L |

| THYROXINE, FREE, SERUM | |||

| Full term (3 days) | 2.0-4.9 ng/dL | ×12.9 | 26-63.1 pmol/L |

| Infants | 0.9-2.6 ng/dL | ×12.9 | 12-33 pmol/L |

| Prepubertal children | 0.8-2.2 ng/dL | ×12.9 | 10-28 pmol/L |

| Pubertal children and adults | 0.8-2.3 ng/dL | ×12.9 | 10-30 pmol/L |

| THYROXINE, TOTAL, WHOLE BLOOD | |||

| Newborn screen (filter paper) | 6.2-22 µg/dL | ×12.9 | 80-283 nmol/L |

| TRIIODOTHYRONINE, FREE, SERUM | |||

| Cord blood | 20-240 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 0.3-0.7 pmol/L |

| 1-3 days | 180-760 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 2.8-11.7 pmol/L |

| 1-5 yr | 185-770 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 2.8-11.8 pmol/L |

| 5-10 yr | 215-700 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 3.3-10.7 pmol/L |

| 10-15 yr | 230-650 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 3.5-10.0 pmol/L |

| >15 yr | 210-440 pg/dL | ×0.01536 | 3.2-6.8 pmol/L |

| TRIIODOTHYRONINE RESIN UPTAKE TEST (RT3 U), SERUM | |||

| Newborn | 26–36% | ×0.01 | 0.26-0.36 fractional uptake |

| Thereafter | 26–35% | ×0.01 | 0.26-0.35 fractional uptake |

| TRIIODOTHYRONINE, TOTAL, SERUM | |||

| Cord blood | 30-70 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 0.46-1.08 nmol/L |

| 1-3 days | 75-260 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 1.16-4.00 nmol/L |

| 1-5 yr | 100-260 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 1.54-4.00 nmol/L |

| 5-10 yr | 90-240 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 1.39-3.70 nmol/L |

| 10-15 yr | 80-210 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 1.23-3.23 nmol/L |

| >15 yr | 115-190 ng/dL | ×0.0154 | 1.77-2.93 nmol/L |

Adapted from Nicholson JF, Pesce MA: Reference ranges for laboratory tests and procedures. In Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors: Nelson textbook of pediatrics , ed 17, Philadelphia, 2004, WB Saunders, pp 2412–2413; TSH from Lem AJ, de Rijke YB, van toor H, et al: Serum thyroid hormone levels in healthy children from birth to adulthood and in short children born small for gestational age, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:3170–3178, 2012; free T3 from Elmlinger MW, Kuhnel W, Lambrecht H-G, et al: Reference intervals from birth to adulthood for serum thyroxine (T4 ), triiodothyronine (T3 ), free T3 , free T4 , thyroxine binding globulin (TBG), and thyrotropin (TSH), Clin Chem Lab Med 39:973–979, 2001.

Several groups of patients deserve vigilance for congenital hypothyroidism. Infants with trisomy 21 or cardiac defects have an increased risk of congenital hypothyroidism. Monozygotic twins are usually discordant for congenital hypothyroidism, but if they are monochorionic, fetal hypothyroidism in the affected twin may be compensated by the normal twin through their shared fetal circulation. In such cases, the affected twin may go undetected on newborn screening in the 1st days of life and present later with untreated hypothyroidism. Preterm and LBW neonates have an increased incidence of congenital hypothyroidism and are more likely to have delayed TSH elevation that may be missed on initial screening. Therefore, in all of these groups of infants, many newborn screening programs perform a routine 2nd test 2-6 wk after birth.

Patients with congenital hypothyroidism have low serum levels of T4 and free T4 . Serum levels of T3 are often normal and are not helpful for diagnosis. If primary hypothyroidism is present, levels of TSH are elevated, often to >100 mU/L. Serum levels of thyroglobulin are usually low in infants with thyroid agenesis, defects of the TSH receptor (including TSHR mutations and TRBAb), or defects in the synthesis or secretion of thyroglobulin itself. In contrast, thyroglobulin levels are usually elevated in patients with thyroid ectopy and other defects of thyroid hormone synthesis, but there is a wide overlap of ranges.

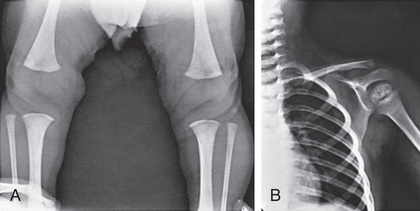

Delay of osseous development can be shown radiographically at birth in approximately 60% of congenitally hypothyroid infants and indicates some deficiency of thyroid hormone during intrauterine life. The distal femoral and proximal tibial epiphyses, normally present at birth, are often absent (Fig. 581.2A ). In untreated patients, the discrepancy between chronologic age and osseous development increases over time. The epiphyses often have multiple foci of ossification (epiphyseal dysgenesis; see Fig. 581.2B ). Deformity (beaking) of the 12th thoracic or 1st or 2nd lumbar vertebra is common. X-rays of the skull show large fontanels and wide sutures, and intersutural (wormian) bones are common. The sella turcica may be enlarged and round, and in rare instances, there may be bony erosion and thinning. Formation and eruption of teeth can be delayed. Cardiac enlargement or pericardial effusion may be present.

Scintigraphy can help to define the underlying cause in infants with congenital hypothyroidism, but treatment should not be delayed to obtain such imaging. 123 I–sodium iodide is superior to 99m Tc–sodium pertechnetate for this purpose. Scintigraphy will demonstrate an ectopic thyroid gland, but the absence of uptake in disorders of the TSH receptor (including TRBAb) or NIS may be mistaken for thyroid agenesis. On the other hand, ultrasonographic examination of the thyroid can document presence or absence of an anatomically normal gland, but it can miss some ectopic glands detectable by scintigraphy. Demonstration of ectopic thyroid tissue is diagnostic of thyroid dysgenesis and establishes the need for lifelong treatment. Failure to demonstrate any thyroid tissue suggests thyroid agenesis. A normally located thyroid gland with normal or increased uptake indicates a defect in thyroid hormone synthesis. In the past, patients with goitrous congenital hypothyroidism (presumably due to dyshormonogenesis) have undergone extensive evaluation including scintigraphy, perchlorate discharge tests, kinetic studies, chromatography, and studies of thyroid tissue, to determine the biochemical nature of the defect. Currently, many can be evaluated by genetic studies looking for a suspected defect in the thyroid hormone biosynthetic pathway; however, attempting to define the precise genetic etiology may be costly, is unsuccessful in at least 40% of cases, and may have little effect on clinical management.

Treatment

Levothyroxine (L -T4 ) given orally is the treatment for congenital hypothyroidism. Although T3 is the biologically active form of thyroid hormone, 80% of circulating T3 is derived from deiodination of circulating T4 , and therefore treatment with L -T4 alone restores normal serum levels of T4 and T3 . The recommended initial dose of L -T4 is 10-15 µg/kg/day (37.5-50 µg/day for most term infants), and within this range the starting dose can be adjusted based on the severity of hypothyroidism. Newborns with more severe hypothyroidism, as judged by a serum T4 <5 µg/dL and/or imaging studies confirming aplasia, should be started at the higher end of the dosage range. Rapid normalization of thyroid function (ideally within 2 wk) is important in achieving optimal neurodevelopmental outcome.

L -T4 should be prescribed only in tablet form in the United States; there is an approved liquid L -T4 preparation in Europe. Tablets should be crushed and mixed with a small volume (1-2 mL) of liquid. L -T4 tablets should not be mixed with soy protein formulas, concentrated iron, or calcium, because these can inhibit L -T4 absorption . Although it is recommended to administer L -T4 on an empty stomach and avoid food for 30-60 min, this is not practical in an infant. As long as the method of administration is consistent, dosing can be adjusted based on serum thyroid test results to achieve the desired treatment goals. One trial has suggested that brand-name L -T4 may be superior to generic formulations in children with severe congenital hypothyroidism.

Levels of serum T4 or free T4 and TSH should be monitored at recommended intervals (every 1-2 mo in the 1st 6 mo of life, and then every 2-4 mo between 6 mo and 3 yr of age). The goals of treatment are to maintain serum TSH in the reference range for age and the serum free T4 or total T4 in the upper half of the reference range for age (see Table 581.3 ). Care should be taken to avoid undertreatment or overtreatment, both of which may be related to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes including decreased intelligence quotient (IQ).

About 35% of infants with congenital hypothyroidism and a normally located thyroid gland have transient disease and do not require lifelong therapy. In patients who might have transient disease, a trial of L -T4 for 4 wk may be undertaken after 3 yr of age for 3-4 wk to assess whether the TSH rises significantly, indicating the presence of permanent hypothyroidism. This is unnecessary in infants with proven thyroid dysgenesis or in those who have previously manifested elevated levels of TSH after 6-12 mo of therapy because of poor medication adherence or an inadequate dose of T4 .

Prognosis

Thyroid hormone is critical for normal neurodevelopment, particularly in the early postnatal months. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of congenital hypothyroidism in the 1st wk of life is essential to prevent irreversible brain damage and results in normal growth and development. In most infants detected by newborn screening, verbal development, psychomotor development, and global IQ scores are similar to those of unaffected siblings or classmate controls. However, the most severely affected infants—those with the lowest T4 levels and most delayed skeletal maturation—may have reduced IQ and other neuropsychologic sequelae such as incoordination, hypotonia or hypertonia, or problems with attention or speech despite early diagnosis and adequate treatment. Psychometric testing can show problems with vocabulary and reading comprehension, arithmetic, and memory. Approximately 10% of children have a neurosensory hearing deficit. Outcome studies in adults who were diagnosed and treated as neonates reveal delayed social development, lower self-esteem, and a lower health-related quality of life. The latter appears to be related to those individuals with lower neurocognitive outcome and associated congenital malformations.

Delay in diagnosis or treatment, failure to correct rapidly the initial hypothyroxinemia, inadequate treatment, or poor adherence to treatment in the first 2-3 yr of life may result in variable degrees of brain damage. Without treatment, severely affected infants have profound intellectual disability and growth retardation. When hypothyroidism develops after 2 yr of age, the outlook for neurodevelopment is much better even if diagnosis and treatment are delayed, which illustrates how critically dependent brain development is on thyroid hormone in the 1st yr of life.

Acquired Hypothyroidism

Epidemiology

Hypothyroidism occurs in approximately 0.3% (1 in 333) of school-age children. Subclinical hypothyroidism (defined as an elevated TSH with normal T4 or free T4 ) is more common, occurring in approximately 2% of adolescents. Autoimmune thyroid disease is the most common cause of acquired hypothyroidism: 6% of children age 12-19 yr have evidence of autoimmune thyroid disease, and females are twice as likely to be affected as males. Although this condition typically arises in adolescence, it may present as early as the 1st yr of life.

Etiology

The most common cause of acquired hypothyroidism (Table 581.4 ) is chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (also called Hashimoto or autoimmune thyroiditis; see Chapter 582 ). Children with trisomy 21, Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, celiac disease, or type 1 diabetes mellitus are at higher risk for associated autoimmune thyroid disease (see Chapter 582 ), as are those with autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APSs ; see Chapter 586 ). APS type 1 (APS-1) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the AIRE gene. It is classically characterized by the triad of mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, and primary adrenal insufficiency. Autoimmune thyroiditis is a less common feature (~10%), as are type 1 diabetes mellitus, primary hypogonadism, pernicious anemia, vitiligo, alopecia, nephritis, hepatitis, and gastrointestinal dysfunction. APS type 2 (APS-2) is far more common than APS-1, and its pathogenesis remains an obscure combination of genetic and environmental factors. APS-2 may consist of any combination of autoimmune thyroiditis (~70%), type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, or less-common manifestations such as primary adrenal insufficiency, primary hypogonadism, pernicious anemia, and vitiligo. Patients with any of these other autoimmune conditions are at increased risk of developing hypothyroidism. For example, about 20% of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus develop thyroid autoantibodies, and about 5% become hypothyroid.

Table 581.4

Etiologic Classification of Acquired Hypothyroidism

IPEX, Immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy X-linked.

In children with trisomy 21 , thyroid autoantibodies develop in approximately 30% and subclinical or overt hypothyroidism occurs in approximately 15–20%. In girls with Turner syndrome , thyroid autoantibodies develop in approximately 40% and subclinical or overt hypothyroidism occurs in approximately 15–30%, rising with increasing age. Additional autoimmune conditions with an increased risk of hypothyroidism include immune dysregulation–polyendocrinopathy–enteropathy–X-linked syndrome (IPEX) and IPEX-like disorders, immunoglobulin G4 –related diseases, Sjögren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis. Williams syndrome is associated with subclinical hypothyroidism, but this does not appear to be autoimmune and thyroid autoantibodies are absent.

Medications can cause acquired hypothyroidism. Some medications containing iodides (e.g., expectorants or nutritional supplements) may cause hypothyroidism through the Wolff-Chaikoff effect (see Chapter 583 ). Amiodarone, a drug used for cardiac arrhythmias and consisting of 37% iodine by weight, causes hypothyroidism in approximately 20% of treated children. Children treated with amiodarone should have serial monitoring of thyroid function.

Anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and valproate, may cause thyroid dysfunction, usually in the form of subclinical hypothyroidism. In some cases, this is due to their effect of stimulating hepatic cytochrome P450 metabolism and excretion of T4 . The anticonvulsant oxcarbazepine can cause central (secondary) hypothyroidism. Children with Graves disease treated with antithyroid drugs (methimazole or propylthiouracil) can develop hypothyroidism. Additional drugs that can produce hypothyroidism include lithium, rifampin, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, interferon-α, stavudine, thalidomide, and aminoglutethimide.

Children who receive therapeutic irradiation , such as for Hodgkin disease or other head and neck malignancies or prior to bone marrow transplantation, are at risk for thyroid damage and hypothyroidism. Approximately 30% of such children acquire elevated TSH levels within a year after therapy, and another 15–20% progress to hypothyroidism within 5-7 yr. Central hypothyroidism may develop in up to 10% of children receiving craniospinal irradiation. Radioactive iodine ablative treatment or thyroidectomy for Graves disease or thyroid cancer results in hypothyroidism, as can removal of ectopic thyroid tissue. Thyroid tissue in a thyroglossal duct cyst may constitute the only source of thyroid hormone, and in this case excision of the cyst results in hypothyroidism. Ultrasonographic examination or a radionuclide scan before surgery is indicated in these patients.

Children with nephropathic cystinosis, a disorder characterized by intralysosomal storage of cystine in body tissues, acquire impaired thyroid function. Hypothyroidism is usually subclinical but may be overt, periodic assessment of TSH levels is indicated. By 13 yr of age, two thirds of these patients require L -T4 replacement.

Histiocytic infiltration of the thyroid in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (see Chapter 534.1 ) can result in hypothyroidism. Children with chronic hepatitis C infection are at risk for subclinical hypothyroidism that does not appear to be autoimmune.

Consumptive hypothyroidism can occur in children with large hemangiomas of the liver. These tumors may express massive amounts of the enzyme type 3 deiodinase, which converts T4 and T3 , respectively, to the inactive metabolites reverse T3 and diiodothyronine (T2 ). Hypothyroidism occurs when the increased secretion of thyroid hormones is insufficient to compensate for their rapid inactivation.

Some patients with mild forms of congenital hypothyroidism (thyroid dysgenesis or genetic defects in thyroid hormone synthesis) do not develop clinical manifestations until childhood. Although these conditions are often detected by newborn screening, very mild defects can escape detection and present later with apparent acquired hypothyroidism.

Any hypothalamic or pituitary disease can cause acquired central hypothyroidism (see Chapter 573 ). TSH deficiency may be the result of a hypothalamic-pituitary tumor (craniopharyngioma is most common in children) or of treatment for a tumor. Other causes include cranial irradiation, head trauma, or infiltrative diseases affecting the pituitary gland such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

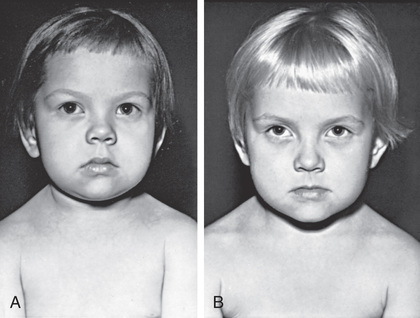

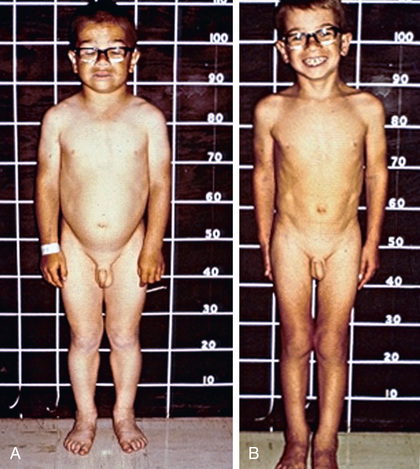

Clinical Manifestations

Slowing of growth is usually the first clinical manifestation of acquired hypothyroidism, but this sign often goes unrecognized (Figs. 581.3 and 581.4 ). Goiter is a common presenting feature. In chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, the thyroid is typically nontender and firm, with a rubbery consistency and pebbly (bosselated) surface. Weight gain is mostly caused by fluid retention (myxedema), not true obesity. Myxedematous changes of the skin, constipation, cold intolerance, decreased energy, and an increased need for sleep develop insidiously. School performance usually does not suffer, even in severely hypothyroid children. Additional features may include bradycardia, muscle weakness or cramps, nerve entrapment, and ataxia. Skeletal maturation is delayed, often strikingly, and the degree of delay reflects the duration of the hypothyroidism. Adolescents typically have delayed puberty. Older adolescent females may have menometrorrhagia, and some may develop galactorrhea because of increased TRH stimulating prolactin secretion. In fact, long-standing primary hypothyroidism can result in enlargement of the pituitary gland, sometimes leading to headaches and vision problems. This is believed to be the result of thyrotroph hyperplasia but may be mistaken for a pituitary tumor, particularly a prolactinoma if prolactin is elevated (see Chapter 573 ). Rarely, young children with profound hypothyroidism may develop secondary sex characteristics (pseudoprecocious puberty), including breast development or vaginal bleeding in girls and testicular enlargement in males. It is hypothesized that this phenomenon results from abnormally high concentrations of TSH binding and stimulating the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor.

Laboratory abnormalities in hypothyroidism may include hyponatremia, macrocytic anemia, hypercholesterolemia, and elevated creatine phosphokinase. Table 581.5 lists the complications of severe hypothyroidism, all of which normalize with adequate replacement of T4.

Table 581.5

| PRESENTATION | SIGNS AND IMPLICATIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| General metabolism | Weight gain, cold intolerance, fatigue | Increase in body mass index, low metabolic rate, myxedema,* hypothermia* |

| Cardiovascular | Fatigue on exertion, shortness of breath | Dyslipidemia, bradycardia, hypertension, endothelial dysfunction or increased intima–media thickness,* diastolic dysfunction,* pericardial effusion,* hyperhomocysteinemia,* electrocardiogram changes* |

| Neurosensory | Hoarseness of voice, decreased taste, vision, or hearing | Neuropathy, cochlear dysfunction, decreased olfactory and gustatory sensitivity |

| Neurologic and psychiatric | Impaired memory, paresthesia, mood impairment | Impaired cognitive function, delayed relaxation of tendon reflexes, depression,* dementia,* ataxia,* carpal tunnel syndrome and other nerve entrapment syndromes,* myxedema coma* |

| Gastrointestinal | Constipation | Reduced esophageal motility, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,* ascites (very rare) |

| Endocrinologic | Infertility and subfertility, menstrual disturbance, galactorrhea | Goiter, glucose metabolism dysregulation, infertility, sexual dysfunction, increased prolactin, pituitary hyperplasia* |

| Musculoskeletal | Muscle weakness, muscle cramps, arthralgia | Creatine phosphokinase elevation, Hoffman syndrome,* osteoporotic fracture* (most probably caused by overtreatment) |

| Hemostasis and hematologic | Bleeding, fatigue | Mild anemia, acquired von Willebrand disease,* decreased protein C and S,* increased red cell distribution width,* increased mean platelet volume* |

| Skin and hair | Dry skin, hair loss | Coarse skin, loss of lateral eyebrows,* yellow palms of the hand,* alopecia areata* |

| Electrolytes and kidney function | Deterioration of kidney function | Decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate, hyponatremia* |

* Uncommon presentation.

From Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, et al: Hypothyroidism, Lancet 390:1550–1560, 2017, Table 1.

Diagnostic Studies

Children with suspected hypothyroidism should undergo measurement of serum TSH and free T4 . Because the normal range for thyroid tests varies by age and is different in children than in adults, it is important to compare results to age-specific reference ranges (see Table 581.3 ). Detection of thyroglobulin or TPO antibodies is diagnostic of chronic lymphocytic (autoimmune) thyroiditis as the etiology. In cases of goiter resulting from autoimmune thyroiditis, ultrasonography typically shows diffuse enlargement and heterogeneous echotexture; however, ultrasonography generally is not indicated unless the physical exam raises suspicion for a thyroid nodule. A bone age x-ray at diagnosis may suggest the duration and severity of hypothyroidism based on the degree of bone age delay.

Treatment and Prognosis

L -T4 is the treatment for children with hypothyroidism. The dose on a weight basis gradually decreases with age. For children age 1-3 yr, the average daily L -T4 dose is 4-6 µg/kg; for age 3-10 yr, 3-5 µg/kg; and for age 10-16 yr, 2-4 µg/kg. Treatment should be monitored by measuring serum TSH every 4-6 mo, as well as 4-6 wk after any change in dosage, and TSH should be maintained in the age-specific reference range. In young children (under age 3 yr), serum free T4 should also be measured and ideally maintained in the upper half of the age-specific reference range. In older children with primary hypothyroidism, serum free T4 need not be measured routinely but may be helpful in certain situations, such as to assess for poor adherence to medication. In children with central hypothyroidism, in which TSH levels by definition do not reflect systemic thyroid status, serum free T4 alone should be monitored and maintained in the upper half of the age-specific reference range.

During the 1st yr of treatment, deterioration of schoolwork, poor sleeping habits, restlessness, short attention span, and behavioral problems may develop, but these issues are transient and more easily managed if families are forewarned about them. Some practitioners feel that these symptoms may be partially ameliorated by starting at a lower dose of L -T4 and advancing slowly. The development of persistent headaches or vision changes should prompt an evaluation for pseudotumor cerebri, a rare complication following initiation of L -T4 treatment in older children (age 8-13 yr).

In older children, after catch-up growth is complete, the growth rate provides a good index of the adequacy of therapy. In children with long-standing hypothyroidism, catch-up growth may be incomplete and final adult height may be irremediably compromised (see Fig. 581.4 ).