Congenital Anomalies of the Central Nervous System

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Central nervous system (CNS) malformations are grouped into neural tube defects (NTDs) and associated spinal cord malformations; encephaloceles; disorders of structure specification (gray matter structures, neuronal migration disorders, disorders of connectivity, and commissure and tract formation); disorders of the posterior fossa, brainstem, and cerebellum; disorders of brain growth and size; and disorders of skull growth and shape. Classification of these conditions into syndromic, nonsyndromic, copy number variations, and single-gene etiologies is also important. These disorders can be isolated findings or a consequence of environmental exposures. Elucidation of single-gene and copy number variations (deletions) causes has outpaced our understanding of the epigenetic and environmental mechanisms that cause these malformations.

These disorders are heterogeneous in their presentation. Common presentations and clinical problems include disorders of head size and/or shape; hydrocephalus; fetal ultrasonographic brain abnormalities; neonatal encephalopathy and seizures; developmental delay, cognitive impairment, and intellectual disability; hypotonia, motor impairment, and cerebral palsy; seizures, epilepsy, and drug-resistant epilepsy; cranial nerve dysfunction; and spinal cord dysfunction.

Neural Tube Defects

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Hydrocephalus

Neural tube defects (NTDs) account for the largest proportion of congenital anomalies of the CNS and result from failure of the neural tube to close spontaneously between the 3rd and 4th wk of in utero development. Although the precise cause of NTDs remains unknown, evidence suggests that many factors, including hyperthermia, drugs (valproic acid), malnutrition, low red cell folate levels, chemicals, maternal obesity or diabetes, and genetic determinants (mutations in folate-responsive or folate-dependent enzyme pathways) can adversely affect normal development of the CNS from the time of conception. In some cases, an abnormal maternal nutritional state or exposure to radiation before conception increases the likelihood of a congenital CNS malformation. The major NTDs include spina bifida occulta, meningocele, myelomeningocele, encephalocele, anencephaly, caudal regression syndrome, dermal sinus, tethered cord, syringomyelia, diastematomyelia, and lipoma involving the conus medullaris and/or filum terminale and the rare condition iniencephaly.

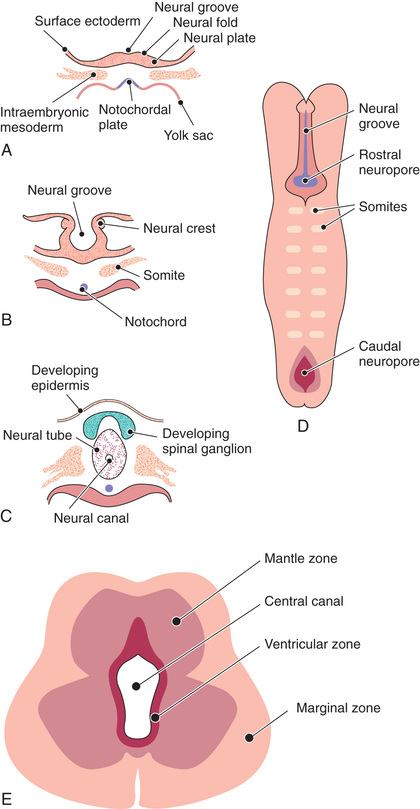

The human nervous system originates from the primitive ectoderm that also develops into the epidermis. The ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm form the three primary germ layers that are developed by the 3rd wk. The endoderm, particularly the notochordal plate and the intraembryonic mesoderm, induces the overlying ectoderm to develop the neural plate in the 3rd wk of development (Fig. 609.1A ). Failure of normal induction is responsible for most NTDs, as well as disorders of prosencephalic development. Rapid growth of cells within the neural plate causes further invagination of the neural groove and differentiation of a conglomerate of cells, the neural crest, which migrate laterally on the surface of the neural tube (see Fig. 609.1B ). The notochordal plate becomes the centrally placed notochord, which acts as a foundation around which the vertebral column ultimately develops. With formation of the vertebral column, the notochord undergoes involution and becomes the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disks. The neural crest cells differentiate to form the peripheral nervous system, including the spinal and autonomic ganglia and the ganglia of cranial nerves V, VII, VIII, IX, and X. In addition, the neural crest forms the leptomeninges, as well as Schwann cells, which are responsible for myelination of the peripheral nervous system. The dura is thought to arise from the paraxial mesoderm. In the region of the embryo destined to become the head, similar patterns exist. In this region, the notochord is replaced by the prechordal mesoderm.

In the 3rd wk of embryonic development, invagination of the neural groove is completed and the neural tube is formed by separation from the overlying surface ectoderm (see Fig. 609.1C ). Initial closure of the neural tube is accomplished in the area corresponding to the future junction of the spinal cord and medulla and moves rapidly both caudally and rostrally. For a brief period, the neural tube is open at both ends, and the neural canal communicates freely with the amniotic cavity (see Fig. 609.1D ). Failure of closure of the neural tube allows excretion of fetal substances (α-fetoprotein [AFP], acetylcholinesterase) into the amniotic fluid, serving as biochemical markers for an NTD. Prenatal screening of maternal serum for AFP in the 16th-18th wk of gestation is an effective method for identifying pregnancies at risk for fetuses with NTDs in utero. Normally, the rostral end of the neural tube closes on the 23rd day and the caudal neuropore closes by a process of secondary neurulation by the 27th day of development, before the time that many women realize they are pregnant.

The embryonic neural tube consists of three zones: ventricular, mantle, and marginal (see Fig. 609.1E ). The ependymal layer consists of pluripotential, pseudostratified, columnar neuroepithelial cells. Specific neuroepithelial cells differentiate into primitive neurons or neuroblasts that form the mantle layer. The marginal zone is formed from cells in the outer layer of the neuroepithelium, which ultimately becomes the white matter. Glioblasts, which act as the primitive supportive cells of the CNS, also arise from the neuroepithelial cells in the ependymal zone. They migrate to the mantle and marginal zones and become future astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. It is likely that microglia originate from mesenchymal cells at a later stage of fetal development when blood vessels begin to penetrate the developing nervous system.

Spina Bifida Occulta (Occult Spinal Dysraphism)

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

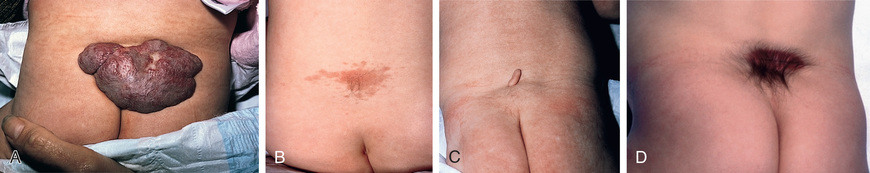

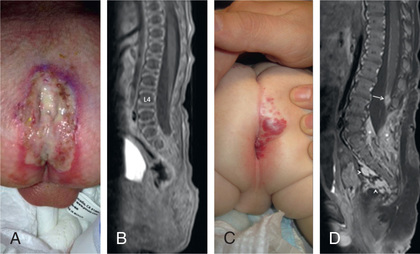

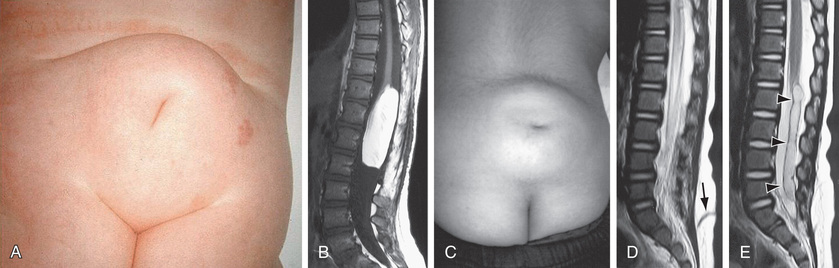

Spina bifida occulta is a common anomaly consisting of a midline defect of the vertebral bodies without protrusion of the spinal cord or meninges. Most patients are asymptomatic and lack neurologic signs, and the condition is usually of no consequence. Some consider the term spina bifida occulta to denote merely a posterior vertebral body fusion defect, as opposed to a true spinal dysraphism. This simple defect does not have an associated spinal cord malformation. Other clinically more significant forms of closed spinal cord malformations are more correctly termed occult spinal dysraphism. In most of these cases, there are cutaneous manifestations such as a hemangioma, discoloration of the skin, pit, lump, dermal sinus, or hairy patch (Figs. 609.2 and 609.3 ). A spine x-ray in simple spina bifida occulta shows a defect in closure of the posterior vertebral arches and laminae, typically involving L5 and S1; there is no abnormality of the meninges, spinal cord, or nerve roots. Occult spinal dysraphism is often associated with more significant developmental abnormalities of the spinal cord, including syringomyelia, diastematomyelia, lipoma, fatty filum, dermal sinus, and/or a tethered cord. A spine x-ray in these cases might show bone defects or may be normal. All cases of occult spinal dysraphism are best investigated with MRI (Fig. 609.4 and see Fig. 609.3 ). Initial screening in the neonate may include ultrasonography, but MRI is more accurate at any age.

A dermoid sinus usually forms a small skin opening, which leads into a narrow duct, sometimes indicated by protruding hairs, a hairy patch, or a vascular nevus. Dermoid sinuses occur in the midline at the sites where meningoceles or encephaloceles can occur: the lumbosacral region or occiput, respectively, and occasionally in the cervical or thoracic area. Dermoid sinus tracts can pass through the dura, acting as a conduit for the spread of infection. Recurrent meningitis of occult origin should prompt careful examination for a small sinus tract in the posterior midline region, including the back of the head. Lumbosacral sinuses are usually above the gluteal fold and are directed cephalad. The tethered spinal cord syndrome may also be an associated problem. Diastematomyelia commonly has bony abnormalities that require surgical intervention along with untethering of the spinal cord.

An approach to imaging of the spine in patients with cutaneous lesions is noted in Table 609.1 .

Table 609.1

From Williams H: Spinal sinuses, dimples, pits and patches: what lies beneath? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 91:ep75-ep80, 2006.

Meningocele

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

A meningocele is formed when the meninges herniate through a defect in the posterior vertebral arches or the anterior sacrum. The spinal cord is usually normal and assumes a normal position in the spinal canal, although there may be tethering of the cord, syringomyelia, or diastematomyelia. A fluctuant midline mass that might transilluminate occurs along the vertebral column, usually in the lower back. Most meningoceles are well covered with skin and pose no immediate threat to the patient. Careful neurologic examination is mandatory. Orthopedic and urologic examination should also be considered. In asymptomatic children with normal neurologic findings and full-thickness skin covering the meningocele, surgery may be delayed or sometimes not performed.

Before surgical correction of the defect, the patient must be thoroughly examined with the use of plain x-rays, ultrasonography, and MRI to determine the extent of neural tissue involvement, if any, and associated anomalies, including diastematomyelia, lipoma, and a possible clinically significant tethered spinal cord. Urologic evaluation usually includes cystometrogram to identify children with neurogenic bladder who are at risk for renal deterioration. Patients with leaking cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or a thin skin covering should undergo immediate surgical treatment to prevent meningitis. A cranial CT scan or an MRI of the head is recommended for children with a meningocele because of the association with hydrocephalus in some cases. An anterior meningocele projects into the pelvis through a defect in the sacrum. Symptoms of constipation and bladder dysfunction develop owing to the increasing size of the lesion. Female patients might have associated anomalies of the genital tract, including a rectovaginal fistula and vaginal septa. Plain x-rays demonstrate a defect in the sacrum, and CT scanning or MRI outlines the extent of the meningocele and any associated anomalies.

Myelomeningocele

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Myelomeningocele represents the most severe form of dysraphism, a so-called aperta or open form, involving the vertebral column and spinal cord; it occurs with an incidence of approximately 1 in 4,000 live births.

Etiology

The cause of myelomeningocele is unknown, but as with all neural tube closure defects, including anencephaly, a genetic predisposition exists; the risk of recurrence after one affected child is 3–4% and increases to 10% with two prior affected children. Both epidemiologic evidence and the presence of substantial familial aggregation of anencephaly, myelomeningocele, and craniorachischisis indicate heredity, on a polygenic basis, as a significant contributor to the etiology of NTDs. Nutritional and environmental factors have a role in the etiology of myelomeningocele as well.

Folate is intricately involved in the prevention and etiology of NTDs. Folate functions in single-carbon transfer reactions and exists in many chemical forms. Folic acid (pteroylmonoglutamic acid), which is the most oxidized and stable form of folate, occurs rarely in food but is the form used in vitamin supplements and in fortified food products, particularly flour. Most naturally occurring folates (food folate) are pteroylpolyglutamates, which contain 1-6 additional glutamate molecules joined in a peptide linkage to the γ-carboxyl of glutamate. Folate coenzymes are involved in DNA synthesis, purine synthesis, generation of formate into the formate pool, and amino acid interconversion; the conversion of homocysteine to methionine provides methionine for the synthesis of S -adenosylmethionine (SAMe, an agent important for in vivo methylation). Mutations in the genes encoding the enzymes involved in homocysteine metabolism may play a role in the pathogenesis of meningomyelocele. These enzymes include 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, cystathionine β-synthase, and methionine synthase. An association between a thermolabile variant of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and mothers of children with NTDs might account for up to 15% of preventable NTDs. Maternal periconceptional use of folic acid supplementation reduces the incidence of NTDs in pregnancies at risk by at least 50%. To be effective, folic acid supplementation should be initiated before conception and continued until at least the 12th wk of gestation, when neurulation is complete. The mechanisms by which folic acid prevents NTDs remain poorly understood.

Prevention

See also Chapter 62.6 .

The United States Public Health Service recommends that all women of childbearing age who can become pregnant take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily. If, however, a pregnancy is planned in high-risk women (previously affected child), supplementation should be started with 4 mg of folic acid daily, beginning 1 mo before the time of the planned conception. The modern diet provides about half the daily requirement of folic acid. To increase folic acid intake, fortification of flour, pasta, rice, and cornmeal with 0.15 mg folic acid per 100 g was mandated in the United States and Canada in 1998. The added folic acid is insufficient to maximize the prevention of preventable NTDs. Therefore, informative educational programs and folic acid vitamin supplementation remain essential for women planning a pregnancy and possibly for all women of childbearing age. In addition, women should also strive to consume food folate from a varied diet. Certain drugs, including drugs that antagonize folic acid, such as trimethoprim and the anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and primidone, increase the risk of myelomeningocele. The anticonvulsant valproic acid causes NTDs in approximately 1–2% of pregnancies when administered during pregnancy. Some epilepsy clinicians recommend that all female patients of childbearing potential who take anticonvulsant medications also receive folic acid supplements. There may be a threshold for ideal red blood cell folate levels (900-1,000 nmol/L), which is associated with a markedly reduced risk of NTDs.

Clinical Manifestations

Myelomeningocele produces dysfunction of many organs and structures, including the skeleton, skin, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts, in addition to the peripheral nervous system and the CNS. A myelomeningocele may be located anywhere along the neuraxis, but the lumbosacral region accounts for at least 75% of the cases. The extent and degree of the neurologic deficit depend on the location of the myelomeningocele and the associated lesions. A lesion in the low sacral region causes bowel and bladder incontinence associated with anesthesia in the perineal area but with no impairment of motor function. Newborns with a defect in the midlumbar or high lumbothoracic region typically have either a sac-like cystic structure covered by a thin layer of partially epithelialized tissue (Fig. 609.5 ) or an exposed flat neural placode without overlying tissues. When a cyst or membrane is present, remnants of neural tissue are visible beneath the membrane, which occasionally ruptures and leaks CSF.

Examination of the infant shows a flaccid paralysis of the lower extremities, an absence of deep tendon reflexes, a lack of response to touch and pain, and a high incidence of lower-extremity deformities (clubfeet, ankle and/or knee contractures, and subluxation of the hips). Some children have constant urinary dribbling and a relaxed anal sphincter. Other children do not leak urine and in fact have a high-pressure bladder and sphincter dyssynergy. Myelomeningocele above the midlumbar region tends to produce lower motor neuron signs because of abnormalities and disruption of the conus medullaris and above spinal cord structures.

Infants with myelomeningocele typically have an increased neurologic deficit as the myelomeningocele extends higher into the thoracic region. These infants sometimes have an associated kyphotic gibbus that requires neonatal orthopedic correction. Patients with a myelomeningocele in the upper thoracic or cervical region usually have a very minimal neurologic deficit and, in most cases, do not have hydrocephalus. They can have a neurogenic bladder and bowel.

Hydrocephalus in association with a type II Chiari malformation develops in at least 80% of patients with myelomeningocele who have not undergone fetal surgery. Generally, patients with sacral myelomeningocele have a very low risk of hydrocephalus. The possibility of hydrocephalus developing after the neonatal period should always be considered, no matter what the spinal level. Ventricular enlargement may be indolent and slow growing or may be rapid, causing a bulging anterior fontanel, dilated scalp veins, setting-sun appearance of the eyes, irritability, and vomiting in association with an increased head circumference. Approximately 15% of infants with hydrocephalus and Chiari II malformation develop symptoms of hindbrain (brainstem) dysfunction, including difficulty feeding, choking, stridor, apnea, vocal cord paralysis, pooling of secretions, and spasticity of the upper extremities, which, if untreated, can lead to death. This Chiari crisis is caused by downward herniation of the medulla and cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum, as well as endogenous malformations in the cerebellum and brainstem, causing dysfunction.

Treatment

Management and supervision of a child and family with a myelomeningocele require a multidisciplinary team approach, including surgeons, other physicians, and therapists, with one individual (often a pediatrician) acting as the advocate and coordinator of the treatment program. The news that a newborn child has a devastating condition such as myelomeningocele causes parents to feel considerable grief and anger. They need time to learn about the condition and its associated complications and to reflect on the various procedures and treatment plans. A knowledgeable individual in an unhurried and nonthreatening setting must give the parents the facts, along with general prognostic information and management strategies and timelines. If possible, discussions with other parents of children with NTDs are helpful in resolving important questions and issues.

Surgery is often done within a day or so of birth but can be delayed for several days (except when there is a CSF leak) to allow the parents time to begin to adjust to the shock and to prepare for the multiple procedures and inevitable problems that lie ahead. Evaluation of other congenital anomalies and renal function can also be initiated before surgery. Most pediatric centers aggressively treat the majority of infants with myelomeningocele. After repair of a myelomeningocele, most infants require a shunting procedure for hydrocephalus. If symptoms or signs of hindbrain dysfunction appear, early surgical decompression of the posterior fossa is indicated. Clubfeet can require taping or casting.

Careful evaluation and reassessment of the genitourinary system is an important component of management. Teaching the parents and, ultimately, the patient, to regularly catheterize a neurogenic bladder is a crucial step in maintaining a low residual volume and bladder pressure that prevents urinary tract infections and reflux, which can lead to pyelonephritis, hydronephrosis, and bladder damage. Latex-free catheters and gloves must be used to prevent development of latex allergy. Periodic urine cultures and assessment of renal function, including serum electrolytes and creatinine as well as renal scans, vesiculourethrograms, renal ultrasonograms, and cystometrograms, are obtained according to the risk status and progress of the patient and the results of the physical examination. This approach to urinary tract management has greatly reduced the need for urologic diversionary procedures and has decreased the morbidity and mortality associated with progressive renal disease in these patients. Some children can become continent with bladder augmentation at a later age.

Although incontinence of fecal matter is common and is socially unacceptable during the school years, it does not pose the same organ-damaging risks as urinary dysfunction, but occasionally fecal impaction and/or megacolon develop. Many children can be bowel-trained with a regimen of timed enemas or suppositories that allows evacuation at a predetermined time once or twice a day. Special attention to low anorectal tone and enema administration and retention is often required. Appendicostomy for antegrade enemas may also be helpful (see Chapter 354 ).

Functional ambulation is the wish of each child and parent and may be possible, depending on the level of the lesion and on intact function of the iliopsoas muscles. Almost every child with a sacral or lumbosacral lesion obtains functional ambulation; approximately half the children with higher defects ambulate with the use of braces, other orthotic devices, and canes. Ambulation is often more difficult as adolescence approaches and body mass increases. Deterioration of ambulatory function, particularly during earlier years, should prompt referral for evaluation of tethered spinal cord and other neurosurgical issues.

In utero surgical closure of a spinal lesion has been successful (Chapter 115.8). There is a lower incidence of hindbrain abnormalities and hydrocephalus (fewer shunts) as well as improved motor outcomes. This suggests that the defects may be progressive in utero and that prenatal closure might prevent the development of further loss of function. In utero diagnosis is facilitated by maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) screening and by fetal ultrasonography (see Chapter 115.7 ).

Prognosis

For a child who is born with a myelomeningocele and who is treated aggressively, the mortality rate is 10–15%, and most deaths occur before age 4 yr, although life-threatening complications occur at all ages. At least 70% of survivors have normal intelligence, but learning problems and seizure disorders are more common than in the general population. Previous episodes of meningitis or ventriculitis adversely affect intellectual and cognitive function. Because myelomeningocele is a chronic disabling condition, periodic and consistent multidisciplinary follow-up is required for life. Renal dysfunction is one of the most important determinants of mortality.

Bibliography

Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, et al. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med . 2011;364:993–1004.

Arth A, Kancherla V, Pachón H, et al. A 2015 global update on folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol . 2016;106(7):520–529.

Bauer SB. Neurogenic bladder: etiology and assessment. Pediatr Nephrol . 2008;23:541–551.

Belfort MA, Whitehead WE, Shamshirsaz AA, et al. Fetoscopic open neural tube defect repair. Obstet Gynecol . 2017;129(4):734–743.

Bitsko RH, Reefhuis J, Romitti PA, et al. Periconceptional consumption of vitamins containing folic acid and risk for multiple congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet . 2007;143A:2397–2405.

Cameron M, Moran P. Prenatal screening and diagnosis of neural tube defects. Prenat Diagn . 2009;29:402–411.

Clarke R, Bennett D. Folate and prevention of neural tube defects. BMJ . 2014;349:g4810.

Cochrane DD. Cord untethering for lipomyelomeningocele: expectation after surgery. Neurosurg Focus . 2007;23:1–7.

Dicianno BE, Kurowski BG, Yang JM, et al. Rehabilitation and medical management of the adult with spina bifida. Am J Phys Med Rehabil . 2008;87:1027–1050.

Guggisberg D, Hadj-Rabia S, Viney C, et al. Skin markers of occult spinal dysraphism in children. Arch Dermatol . 2004;140:1109–1115.

Heuer GG, Moldenhauer JS, Scott Adzick N. Prenatal surgery for myelomeningocele: review of the literature and future directions. Childs Nerv Syst . 2017;33(7):1149–1155.

Ickowicz V, Ewin D, Maugay-Laulom B, et al. Meckel-gruber syndrome, sonography and pathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol . 2006;27:296–300.

Kahn L, Biro EE, Smith RD, et al. Spina bifida occulta and aperta: a review of current treatment paradigms. J Neurosurg Sci . 2015;59(1):79–90.

Kancherla V, Walani SR, Weakland AP, et al. Scorecard for spina bifida research, prevention, and policy—a development process. Prev Med . 2017;99:13–20.

Madden-Fuentes RJ, McNamara ER, Lloyd JC, et al. Variation in definitions of urinary tract infections in spina bifida patients: a systematic review. Pediatrics . 2013;132:132–139.

Nagaraj UD, Bierbrauer KS, Zhang B, et al. Hindbrain herniation in chiari II malformation on fetal and postnatal MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2017;38(5):1031–1036.

O'Neill BR, Gallegos D, Herron A, et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to detect occult spinal dysraphism in infants. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2017;19(2):217–226.

Peranteau WH, Adzick S. Prenatal surgery for myelomeningocele. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol . 2016;28:111–118.

Scales CD, Wiener JS. Evaluating outcomes of enterocystoplasty in patients with spina bifida: a review of the literature. J Urol . 2008;180:2323–2329.

Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Sepulveda F, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of spina bifida: from intracranial translucency to intrauterine surgery. Childs Nerv Syst . 2017;33(7):1083–1099.

Shin M, Kucik JE, Siffel C, et al. Improved survival among children with spina bifida in the United States. J Pediatr . 2012;161:1132–1137.

Tubbs RS, Bui CJ, Loukas M, et al. The horizontal sacrum as an indicator of the tethered spinal cord in spina bifida aperta and occulta. Neurosurg Focus . 2007;23:1–4.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation statement: folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects. Ann Intern Med . 2009;150:626–631.

Urrutia J, Cuellar J, Zamora T. Spondylolysis and spina bifida occulta in pediatric patients: prevalence study using computed tomography as a screening method. Eur Spine J . 2016;25(2):590–595.

Yu J, Maheshwari M, Foy AB, et al. Neonatal lumbosacral ulceration masking lumbosacral and intraspinal hemangiomas associated with occult spinal dysraphism. J Pediat . 2016;175:211–215.

Ware AL, Kulesz PA, Juranek J, et al. Cognitive control and associated neural correlates in adults with spina bifida myelomeningocele. Neuropsychology . 2017;31(4):411–423.

Williams H. Spinal sinuses, dimples, pits and patches: what lies beneath? Arch Dis Child . 2006;91:ep75–ep80.

Encephalocele

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Two major forms of dysraphism affect the skull, resulting in protrusion of tissue through a bony midline defect, called cranium bifidum. A cranial meningocele consists of a CSF-filled meningeal sac only, and a cranial encephalocele contains the sac plus cerebral cortex, cerebellum, or portions of the brainstem. Microscopic examination of the neural tissue within an encephalocele often reveals abnormalities. The cranial defect occurs most commonly in the occipital region at or below the inion, but in certain parts of the world, frontal or nasofrontal encephaloceles (transethmoidal, sphenoethmoidal, sphenomaxillary, sphenoorbital, transsphenoidal) are more common. Some frontal lesions are associated with a cleft lip and palate. These abnormalities are one tenth as common as neural tube closure defects involving the spine. The etiology is presumed to be similar to that for anencephaly and myelomeningocele; examples of each are reported in the same family.

Infants with a cranial encephalocele are at increased risk for developing hydrocephalus because of aqueductal stenosis, Chiari malformation, or the Dandy-Walker syndrome. Examination might show a small sac with a pedunculated stalk or a large cyst-like structure that can exceed the size of the cranium. The lesion may be completely covered with skin, but areas of denuded lesion can occur and require urgent surgical management. Transillumination of the sac can indicate the presence of neural tissue. A plain x-ray of the skull and cervical spine is indicated to define the anatomy of the cranium and vertebrae. Ultrasonography is most helpful in determining the contents of the sac. MRI or CT further helps define the spectrum of the lesion. Children with a cranial meningocele generally have a good prognosis, whereas patients with an encephalocele are at risk for vision problems, microcephaly, intellectual disability, and seizures. Generally, children with neural tissue within the sac and associated hydrocephalus have the poorest prognosis.

Cranial encephalocele is often part of a syndrome. Meckel-Gruber syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive condition that is characterized by an occipital encephalocele, cleft lip or palate, microcephaly, microphthalmia, abnormal genitalia, polycystic kidneys, and polydactyly. Determination of maternal serum AFP levels and ultrasound measurement of the biparietal diameter, as well as identification of the encephalocele itself, can diagnose encephaloceles in utero. Fetal MRI can help define the extent of associated CNS anomalies and the degree of brain herniated into the encephalocele.

Bibliography

France D, Alonso N, Ruas R, et al. Transsphenoidal meningoencephalocele associated with cleft lip and palate: challenges for diagnosis and surgical treatment. Childs Nerv Syst . 2009;25:1455–1458.

Joó JG, Papp Z, Berkes E, et al. Non-syndromic encephalocele: a 26-year experience. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2008;50:958–960.

Leitch CC, Zaghloul NA, Davis EE, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-biedl syndrome. Nat Genet . 2008;40:443–448.

Ramdurg SR, Sukanya M, Maitra J. Pediatric encephaloceles: a series of 20 cases over a period of 3 years. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2015;10(4):317–320.

Yucetas SC, Uçler N. A retrospective analysis of neonatal encephalocele predisposing factors and outcomes. Pediatr Neurosurg . 2017;52(2):73–76.

Anencephaly

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

An anencephalic infant presents a distinctive appearance with a large defect of the calvarium, meninges, and scalp associated with a rudimentary brain, which results from failure of closure of the rostral neuropore, the opening of the anterior neural tube. The primitive brain consists of portions of connective tissue, vessels, and neuroglia. The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum are usually absent, and only a residue of the brainstem can be identified. The pituitary gland is hypoplastic, and the spinal cord pyramidal tracts are missing due to the absence of the cerebral cortex. Additional anomalies, including folding of the ears, cleft palate, and congenital heart defects, occur in 10–20% of cases. Most anencephalic infants die within several days of birth.

The incidence of anencephaly approximates 1 in 1,000 live births; the greatest incidence is in Ireland, Wales, and Northern China. The recurrence risk is approximately 4% and increases to 10% if a couple has had two previously affected pregnancies. Many factors, in addition to genetics, are implicated as a cause of anencephaly, including low socioeconomic status, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, and a large number of environmental and toxic factors. It is very likely that several noxious stimuli interact on a genetically susceptible host to produce anencephaly. The incidence of anencephaly has been decreasing since the 1990s. Approximately 50% of cases of anencephaly have associated polyhydramnios. Couples who have had an anencephalic infant should have successive pregnancies monitored, including with amniocentesis, determination of AFP levels, and ultrasound examination, between the 14th and 16th wk of gestation. Prenatal folic acid supplementation decreases the risk of this condition.

Disorders of Neuronal Migration

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Disorders of neuronal migration can result in minor abnormalities with little or no clinical consequence (small heterotopia of neurons) or devastating abnormalities of CNS structure and/or function (intellectual disability, seizures, lissencephaly, and schizencephaly, particularly the open-lip form) (Fig. 609.6 ). One of the most important mechanisms in the control of neuronal migration is the radial glial fiber system that guides neurons to their proper site. Migrating neurons attach to the radial glial fiber and then disembark at predetermined sites to form, ultimately, the precisely designed 6-layered cerebral cortex. Another important mechanism is the tangential migration of progenitor neurons destined to become cortical interneurons. The severity and the extent of the disorder are related to numerous factors, including the timing of a particular insult and a host of environmental and genetic contributors. Some cortical malformations may be from somatic mutations, as exemplified by kinesin gene mutations in patients with pachygyria.

Lissencephaly

Lissencephaly, or agyria, is a rare disorder that is characterized by the absence of cerebral convolutions and a poorly formed sylvian fissure, giving the appearance of a 3- to 4-mo fetal brain. The condition is probably a result of faulty neuroblast migration during early embryonic life and is usually associated with enlarged lateral ventricles and heterotopias in the white matter. In some forms, there is a 4-layered cortex, rather than the usual 6-layered one, with a thin rim of periventricular white matter and numerous gray heterotopias visible by microscopic examination. Milder forms of lissencephaly also exist.

These infants present with failure to thrive, microcephaly, marked developmental delay, and often a severe seizure disorder. Ocular abnormalities are common, including hypoplasia of the optic nerve and microphthalmia. Lissencephaly can occur as an isolated finding, but it is associated with Miller-Dieker syndrome in approximately 15% of cases. These children have characteristic facies, including a prominent forehead, bitemporal hollowing, anteverted nostrils, a prominent upper lip, and micrognathia. Approximately 70% of children with Miller-Dieker syndrome have visible or submicroscopic chromosomal deletions of 17p13.3.

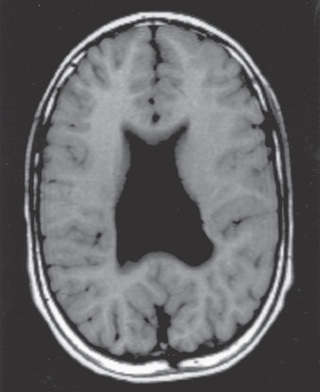

The gene LIS-1 (lissencephaly 1) that maps to chromosome region 17p13.3 is deleted in patients with Miller-Dieker syndrome. CT and MRI scans typically show a smooth brain with an absence of sulci (Fig. 609.7 ). Doublecortin is an X chromosome gene that causes lissencephaly when mutated in males and subcortical band heterotopia when mutated in females. Other important forms of lissencephaly include the Walker-Warburg variant and other cobblestone cortical malformations.

Schizencephaly

Schizencephaly is the presence of unilateral or bilateral clefts within the cerebral hemispheres due to an abnormality of morphogenesis (Fig. 609.8 ). The cleft may be fused or unfused and, if unilateral and large, may be confused with a porencephalic cyst. Not infrequently, the borders of the cleft are surrounded by abnormal brain, particularly microgyria. MRI is the study of choice for elucidating schizencephaly and associated malformations.

When the clefts are bilateral, many patients are severely intellectually challenged, with seizures that are difficult to control, and microcephaly with spastic quadriparesis. Some cases of bilateral schizencephaly are associated with septooptic dysplasia and endocrinologic disorders. Unilateral schizencephaly is a common cause of congenital hemiparesis. It remains controversial whether genetic causes of schizencephaly exist. Some gene mutations are seen in cases of familial schizencephaly.

Neuronal Heterotopias

Subtypes of neuronal heterotopias include periventricular nodular heterotopias, subcortical heterotopia (including band-type), and marginal glioneuronal heterotopias. Intractable seizures are a common feature. Several genes have been identified that are a cause of these conditions.

Polymicrogyrias

Polymicrogyria is characterized by an augmentation of small convolutions separated by shallow enlarged sulci (Fig. 609.9 ). Epilepsy, including drug-resistant forms, is a common feature. Truncation of the KBP gene has been implicated in a family with multiple members with polymicrogyria; other disorders are noted in Table 609.2 .

Table 609.2

Named Syndromes in Which Polymicrogyria Has Been Reported Multiple Times

| SYNDROME | PMG PATTERN | OTHER FEATURES | GENETIC BASIS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aicardi | Variable, multifocal | Agenesis of corpus callosum, retinal lacunae | X-linked: gene unknown |

| Chudley-McCullough | Frontal | Sensorineural hearing loss, hydrocephalus, agenesis of corpus callosum | GPSM2 mutations |

| DiGeorge/velocardiofacial | Perisylvian, unilateral or bilateral | Cardiac defects, parathyroid hypoplasia, facial dysmorphism, thymus hypoplasia | 22q11.2 deletion |

| Ehlers–Danlos | Perisylvian and frontal | Skin fragility, cutaneous extensibility, joint laxity, bruising | Multiple genes |

| Kabuki make-up (Niikawa–Kuroki) | Perisylvian | Facial dysmorphism, digital anomalies, skeletal anomalies, microcephaly | MLL2 and KDM6A mutations |

| Knobloch | Frontal | Eye abnormalities, occipital skull defects | COL18A1 mutations |

| Leigh and other mitochondrial disorders, including PDH deficiency | Variable | Multiple CNS abnormalities, lactic acidosis, neurodegeneration, ocular abnormalities | Mitochondrial, including respiratory chain disorders |

| Meckel–Gruber | Variable | Occipital meningoencephalocele, arrhinencephaly, polycystic kidneys, polydactyly, bile duct abnormalities | Autosomal recessive, multiple genes |

| Megalencephaly-capillary malformation-polymicrogyria (MCAP) | Variable | Macrocephaly, vascular malformations, syndactyly, occasional hyperelasticity or thick skin | PIK3CA mutations |

| Megalencephaly-polymicrogyria-polydactyly-hydrocephalus (MPPH) | Variable | Macrocephaly, polydactyly | PIK3R2 and AKT3 mutations |

| Warburg-Micro | Frontal | Microcephaly, cataracts, microcornea, optic atrophy, hypogenitalism, hypoplasia of corpus callosum | RAB3GAP mutations |

| Oculocerebrocutaneous (Delleman) | Frontal | Orbital anomalies, skin defects, and multiple brain anomalies | Possibly autosomal dominant, gene unknown |

| Pena–Shokeir | Variable | IUGR, camptodactyly, multiple ankyloses, facial dysmorphism, pulmonary hypoplasia | Autosomal recessive, multiple genes |

| Sturge–Weber | Underlying cortical angiomatosis | Facial hemangioma, glaucoma | Somatic mutations in GNAQ |

| Thanatophoric dysplasia | Temporal | Skeletal anomalies, hypoplastic lungs, megalencephaly | Autosomal dominant, multiple genes |

| Zellweger and other peroxisomal disorders | Generalized | White matter dysmyelination, facial dysmorphism, intrahepatic biliary dysgenesis, stippled epiphyses, renal cysts | Peroxisomal (PEX , PXMP, and PXR gene family mutations) |

From Stutterd CA, Leventer RJ: Polymicrogyria: a common and heterogeneous malformation of cortical development. Am J Med Genet (Semin Med Genet) 166C:227-239, 2014, Table 1.

Focal Cortical Dysplasias

Focal cortical dysplasias consist of abnormal cortical lamination in a discrete area of cortex. High-resolution, thin-section MRI can reveal these areas sometimes in the setting of drug-resistant epilepsy.

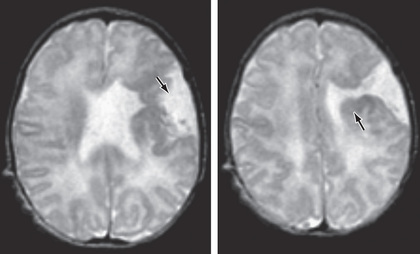

Porencephaly

Porencephaly is the presence of cysts or cavities within the brain that result from developmental defects or acquired lesions, including infarction of tissue. True porencephalic cysts are most commonly located in the region of the sylvian fissure and typically communicate with the subarachnoid space or the ventricular system, or both. They represent developmental abnormalities of cell migration and are often associated with other malformations of the brain, including microcephaly, abnormal patterns of adjacent gyri, and encephalocele. Affected infants tend to have many problems, including intellectual disability, spastic hemiparesis or quadriparesis, optic atrophy, and seizures.

Several risk factors for porencephalic cyst formation have been identified, including hemorrhagic venous infarctions; various thrombophilias such as protein C deficiency and factor V Leiden mutations; perinatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia; von Willebrand disease; maternal warfarin use; maternal cocaine use; congenital infections; trauma such as amniocentesis; and maternal abdominal trauma. Mutations in the COL4A1 and COL4A2 genes have been described in cases of familial porencephaly.

Pseudoporencephalic cysts characteristically develop during the perinatal or postnatal period and result from abnormalities (infarction, hemorrhage) of arterial or venous circulation. These cysts tend to be unilateral, do not communicate with a fluid-filled cavity, and are not associated with abnormalities of cell migration or CNS malformations. Infants with pseudoporencephalic cysts present with hemiparesis and focal seizures in the first year of life and sometimes present with neonatal encephalopathy or as a floppy newborn or infant.

Bibliography

Abdel Razek AAK, Kandell AY, Elsorogy LG, et al. Disorders of cortical formation: MR imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2009;30:4–11.

Almgren M, Schalling M, Lavebratt C. Idiopathic megalencephaly—possible cause and treatment opportunities: from patient to lab. Eur J Paediatr Neurol . 2008;12:438–445.

Breedveld G, de Coo IF, Lequin MH, et al. Novel mutations in three families confirm a major role of COL4A1 in hereditary porencephaly. J Med Genet . 2006;43:490–495.

Cossu M, Pelliccia V, Gozzo F, et al. Surgical treatment of polymicrogyria-related epilepsy. Epilepsia . 2016;57(12):2001–2010.

Gould DB, Phalan FC, Breedveld GJ, et al. Mutations in col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science . 2005;308:1167–1171.

Guerrini R, Dobyns WB, Barkovich AJ. Abnormal development of the human cerebral cortex: genetics, functional consequences and treatment options. Trends Neurosci . 2008;31:154–162.

Hayashi N, Tsutsumi Y, Barkovich AJ. Polymicrogyria without porencephaly/schizencephaly. MRI analysis of the spectrum and the prevalence of macroscopic findings in the clinical population. Neuroradiology . 2002;44:647–655.

Jamuar SS, Lam ATN, Kircher M, et al. Somatic mutations in cerebral cortical malformations. N Engl J Med . 2014;371:733–742.

Kerjan G, Gleeson JG. Genetic mechanisms underlying abnormal neuronal migration in classical lissencephaly. Trends Genet . 2007;23:623–630.

McGovern M, Flanagan O, Lynch B, et al. Novel COL4A2 variant in a large pedigree: consequences and dilemmas. Clin Genet . 2017;92(4):447–448.

Meuwissen ME, Halley DJ, Smit LS, et al. The expanding phenotype of COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations: clinical data on 13 newly identified families and a review of the literature. Genet Med . 2015;17(11):843–853.

Parrini E, Conti V, Dobyns WB, Guerrini R. Genetic basis of brain malformations. Mol Syndromol. 2016;7(4):220–233.

Ruggieri M, Praticò AD. Mosaic neurocutaneous disorders and their causes. Semin Pediatr Neurol . 2015;22(4):207–233.

Sharif U, Kuban K. Prenatal intracranial hemorrhage and neurologic complications in alloimmune thrombocytopenia. J Child Neurol . 2001;16:838–842.

Spalice A, Parisi P, Nicita F, et al. Neuronal migration disorders: clinical, neuroradiologic and genetics aspects. Acta Paediatr . 2009;98:421–433.

Stutterd CA, Leventer RJ. Polymicrogyria: a common and heterogeneous malformation of cortical development. Am J Med Genet (Semin Med Genet) . 2014;166C:227–239.

van der Knaap MS, Smit LME, Barkhof F, et al. Neonatal porencephaly and adult stroke related to mutations in collagen IV A1. Ann Neurol . 2006;59:504–511.

Wynshaw-Boris A. Lissencephaly and LIS1: insights into the molecular mechanisms of neuronal migration and development. Clin Genet . 2007;72:296–304.

Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

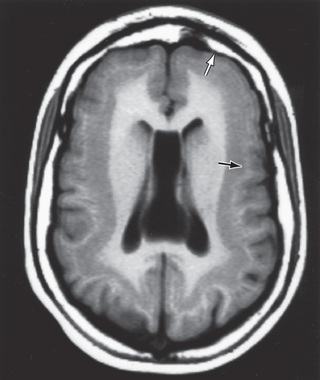

Agenesis of the corpus callosum consists of a heterogeneous group of disorders that vary in expression from severe intellectual and neurologic abnormalities to the asymptomatic and normally intelligent patient (Fig. 609.10 ). The corpus callosum develops from the commissural plate that lies in proximity to the anterior neuropore. Either a direct insult to the commissural plate or disruption of the genetic signaling that specifies and organizes this area during early embryogenesis can cause agenesis of the corpus callosum.

When agenesis of the corpus callosum is an isolated phenomenon, the patient may still be normal. When it is accompanied by brain anomalies from cell migration defects, such as heterotopias, polymicrogyria, and pachygyria (broad, wide gyri), patients often have significant neurologic abnormalities, including intellectual disability, microcephaly, hemiparesis or diplegia, and seizures.

The anatomic features of agenesis of the corpus callosum are best depicted on MRI and include widely separated frontal horns with an abnormally high position of the third ventricle between the lateral ventricles. MRI precisely outlines the extent of the corpus callosum defect. Absence of the corpus callosum may be inherited as an X-linked recessive trait or as an autosomal dominant trait and on occasion as an autosomal recessive trait. The condition may be associated with specific chromosomal disorders, particularly trisomy 8 and trisomy 18. Single-gene mutations have been described in multiple genes causing agenesis of the corpus callosum. So too have copy number variations (deletions) been identified but usually when agenesis is associated with other anomalies. Agenesis of the corpus callosum is also seen in some metabolic disorders (Table 609.3 ).

Table 609.3

Disorders Associated With Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum*

| DISORDER | SALIENT FEATURES |

|---|---|

| WITH IDENTIFIED GENES † | |

| Andermann syndrome (KCC3) | ACC, progressive neuropathy, and dementia |

| Donnai-Barrow syndrome (LRP2) | Diaphragmatic hernia, exomphalos, ACC, deafness |

| Frontonasal dysplasia (ALX1) | ACC, bilateral extreme microphthalmia, bilateral oblique facial cleft |

| XLAG (ARX) | Lissencephaly, ACC, intractable epilepsy |

| Microcephaly (TBR2) | ACC, polymicrogyria |

| Microcephaly with simplified gyral pattern and ACC (WDR62) | |

| Mowat-Wilson syndrome (ZFHX1B) | Hirschsprung disease, ACC |

| Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (ALDH7A1) | ACC, seizures, other brain malformations |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHA1, PDHB, PDHX) | ACC with other brain changes |

| ACC with fatal lactic acidosis (MRPS16) | Complexes I and IV deficiency, ACC, brain malformations |

| HSAS/MASA syndromes (L1CAM) | Hydrocephalus, adducted thumbs, ACC, MR |

| ACC SEEN CONSISTENTLY (NO GENE YET IDENTIFIED) | |

| Acrocallosal syndrome | ACC, polydactyly, craniofacial changes, MR |

| Aicardi syndrome | ACC, chorioretinal lacunae, infantile spasms, MR |

| Chudley-McCullough syndrome | Hearing loss, hydrocephalus, ACC, colpocephaly |

| FG syndrome | MR, ACC, craniofacial changes, macrocephaly |

| Genitopatellar syndrome | Absent patellae, urogenital malformations, ACC |

| Temtamy syndrome | ACC, optic coloboma, craniofacial changes, MR |

| Toriello-Carey syndrome | ACC, craniofacial changes, cardiac defects, MR |

| Vici syndrome | ACC, albinism, recurrent infections, MR |

| ACC SEEN OCCASIONALLY (PARTIAL LIST) ‡ | |

| ACC with spastic paraparesis (SPG11, SPG15) | Progressive spasticity and neuropathy, thin corpus callosum |

| Craniofrontonasal syndrome | Coronal craniosynostosis, facial asymmetry, bifid nose |

| Fryns syndrome | CDH, pulmonary hypoplasia, craniofacial changes |

| Marden-Walker syndrome | Blepharophimosis, micrognathia, contractures, ACC |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | Encephalocele, polydactyly, polycystic kidneys |

| Nonketotic hyperglycinemia (GLDC, GCST, GCSH) | ACC, cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, myoclonus, progressive encephalopathy |

| Microphthalmia with linear skin defects | Microphthalmia, linear skin markings, seizures |

| Opitz G syndrome | Pharyngeal cleft, craniofacial changes, ACC, MR |

| Orofaciodigital syndrome | Tongue hamartoma, microretrognathia, clinodactyly |

| Pyruvate decarboxylase deficiency | Lactic acidosis, seizures, severe MR and spasticity |

| Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome | Broad thumbs and great toes, MR, microcephaly |

| Septooptic dysplasia (de Morsier syndrome) | Hypoplasia of septum pellucidum and optic chiasm |

| Sotos syndrome | Physical overgrowth, MR, craniofacial changes |

| Warburg micro syndrome | Microcephaly, microphthalmia, microgenitalia, MR |

| Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome | Microcephaly, seizures, cardiac defects, 4p− |

* Reliable incidence data are unavailable for these very rare syndromes.

† Gene symbols in parentheses.

‡ Many of these also may consistently have a thin dysplastic corpus callosum, such as Sotos syndrome or agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) with spastic paraparesis (SPG11). The overlap between ACC and these conditions is still under investigation. Other gene symbols are omitted from this section.

4p−, deletion of the terminal region of the short arm of chromosome 4, defines the genotype for Wolf-Hirschhorn patients; ACC, agenesis of the corpus callosum; ARX, Aristaless-related homeobox gene; CDH, congenital diaphragmatic hernia; HSAS/MASA, X-linked hydrocephalus/mental retardation, aphasia, shuffling gait, and adducted thumbs; KCC3, KCl cotransporter 3; L1CAM, L1 cell adhesion molecule; MR, mental retardation; MRPS16, mitochondrial ribosomal protein S16; SPG11, spastic paraplegia 11; XLAG, X-linked lissencephaly with absent corpus callosum and ambiguous genitalia; ZFHX1B, zinc finger homeobox 1b.

From Sherr EH, Hahn JS: Disorders of forebrain development. In Swaiman KF, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM, Schor NF, editors: Swaiman's Pediatric Neurology, 5th ed., Philadelphia, 2012, WB Saunders, Table 23-2.

Aicardi syndrome represents a complex disorder that affects many systems and is typically associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum, distinctive chorioretinal lacunae, and infantile spasms. Patients are almost all female, suggesting a genetic abnormality of the X chromosome (it may be lethal in males during fetal life). Seizures become evident during the first few months and are typically resistant to anticonvulsants. An electroencephalogram shows independent activity recorded from both hemispheres as a result of the absent corpus callosum and often shows hemihypsarrhythmia. All patients have severe intellectual disability and can have abnormal vertebrae that may be fused or only partially developed (hemivertebra). Abnormalities of the retina, including circumscribed pits or lacunae and coloboma of the optic disc, are the most characteristic findings of Aicardi syndrome.

Colpocephaly refers to an abnormal enlargement of the occipital horns of the ventricular system and can be identified as early as the fetal period. It is often associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum, but it can occur in isolation. It is also associated with microcephaly. It can also be seen in anatomic megalencephaly, such as is associated with Sotos syndrome.

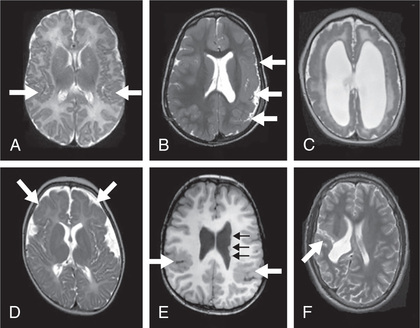

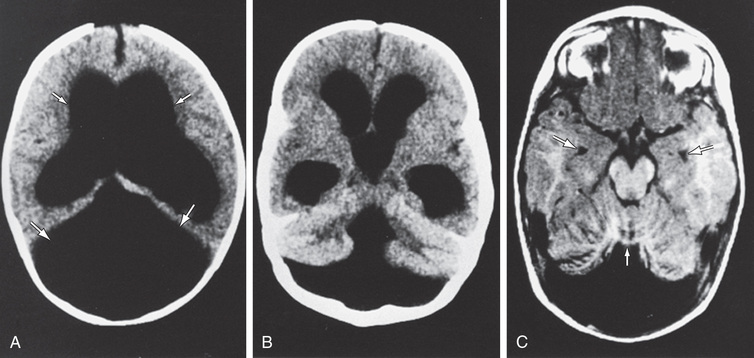

Holoprosencephaly

Holoprosencephaly is a developmental disorder of the brain that results from defective formation of the prosencephalon and inadequate induction of forebrain structures. The abnormality, which represents a spectrum of severity, is classified into three groups: alobar, semilobar, and lobar, depending on the degree of the cleavage abnormality (Fig. 609.11 ). A fourth type, the middle interhemispheric fusion variant or syntelencephaly, involves a segmental area of noncleavage, actually a nonseparation, of the posterior frontal and parietal lobes. Facial abnormalities, including cyclopia, synophthalmia, cebocephaly, single nostril, choanal atresia, solitary central incisor tooth, and premaxillary agenesis are common in severe cases, because the prechordal mesoderm that induces the ventral prosencephalon is also responsible for induction of the median facial structures. Milder facial abnormalities are seen in milder forms. Alobar holoprosencephaly is characterized by a single ventricle, an absent falx, and nonseparated deep cerebral nuclei. Care must be taken not to overdiagnose holoprosencephaly based on ventricular abnormalities alone. Evidence of nonseparated midline deep-brain structures, such as caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, and hypothalamus, is the critical element for diagnosis.

Affected children with the alobar type have high mortality rates, but some live for years. Mortality and morbidity with milder types are more variable, and morbidity is less severe. Care must be taken not to prognosticate severe outcomes in all cases. The incidence of holoprosencephaly ranges from 1 in 5,000-16,000 live births. A prenatal diagnosis can be confirmed by ultrasonography after the 10th wk of gestation for more severe types, but fetal MRI at later gestational ages gives far greater anatomic, and therefore diagnostic, precision.

The cause of holoprosencephaly is often not identified. There appears to be an association with maternal diabetes. Chromosomal abnormalities, including deletions of chromosomes 7q and 3p, 21q, 2p, 18p, and 13q, as well as trisomy 13 and 18, account for upward of 50% of all cases. Mutations in the sonic hedgehog gene at 7q have been shown to cause holoprosencephaly. Gene Reviews lists 14 single-gene causes. Clinically, it is important to look for associated anomalies, because many syndromes are associated with holoprosencephaly.

Bibliography

Bedeschi MF, Bonaglia MC, Grasso R, et al. Agenesis of the corpus callosum: clinical and genetic study in 63 young patients. Pediatr Neurol . 2006;34:186–193.

Bendavid C, Dubourg C, Gicquel I, et al. Molecular evaluation of foetuses with holoprosencephaly shows high incidence of microdeletions in the HPE genes. Hum Genet . 2006;119:1–8.

Dubourg C, Lazaro L, Pasquier L, et al. Molecular screening of SHH, ZIC2, SIX3, and TGIF genes in patients with features of holoprosencephaly spectrum: mutation review and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat . 2004;24:43–51.

Glass HC, Shaw GM, Ma C, et al. Agenesis of the corpus callosum in California 1983–2003: a population-based study. Am J Med Genet . 2008;146A:2495–2500.

Goetzinger KR, Stamilio DM, Dicke JM, et al. Evaluating the incidence and likelihood ratios for chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with common central nervous system malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2008;199(285):e1–e6.

Griffiths PD, Batty R, Connolly DA, et al. Effects of failed commissuration on the septum pellucidum and fornix: implications for fetal imaging. Neuroradiology . 2009;51:347–356.

Heide S, Keren B, Billette de Villemeur T, et al. Copy number variations found in patients with a corpus callosum abnormality and intellectual disability. J Pediatr . 2017;185:160–166.

Herman-Sucharska I, Bekiesinska-Figatowska M, Urbanik A. Fetal central nervous system malformations on MR images. Brain Dev . 2009;31:185–199.

Houtmeyers R, Tchouate Gainkam O, Glanville-Jones HA, et al. Zic2 mutation causes holoprosencephaly via disruption of NODAL signaling. Hum Mol Genet . 2016;25(18):3946–3959.

Kerjan G, Gleeson JG. Genetic mechanisms underlying abnormal neuronal migration in classical lissencephaly. Trends Genet . 2007;23:623–630.

Miller SP, Shevell MI, Patenaude Y, et al. Septo-optic dysplasia plus: a spectrum of malformations of cortical development. Neurology . 2000;54:1701–1703.

Moes P, Schilmoeller K, Schilmoeller G. Physical, motor, sensory and developmental features associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Child Care Health Dev . 2009;35:656–672.

Mouden C, Dubourg C, Carré W, et al. Complex mode of inheritance in holoprosencephaly revealed by whole exome sequencing. Clin Genet . 2016;89(6):659–668.

Passos-Bueno MR, et al. Genetics of craniosynostosis: genes, syndromes, mutations and genotype-phenotype correlations. Front Oral Biol . 2008;12:107–143.

Polizzi A, Pavone P, Iannetti P, et al. Septo-optic dysplasia complex: a heterogeneous malformation syndrome. Pediatr Neurol . 2006;34:66–71.

Romaniello R, Marelli S, Giorda R, et al. Clinical characterization, genetics, and long-term follow-up of a large cohort of patients with agenesis of the corpus callosum. J Child Neurol . 2017;32(1):60–71.

Saba L, Anzidel M, Raz E, et al. MR and CT of Brain's cava. J Neuroimaging . 2013;23:326–335.

Schell-Apacik CC, Wagner K, Bihler M, et al. Agenesis and dysgenesis of the corpus callosum: clinical, genetic and neuroimaging findings in a series of 41 patients. Am J Med Genet . 2008;146A:2501–2511.

Smith T, Tekes A, Boltshauser E, et al. Commissural malformations: beyond the corpus callosum. J Neuroradiol . 2008;35:301–303.

Wegiel J, Flory M, Kaczmarski W, et al. Partial agenesis and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum in idiopathic autism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol . 2017;76(3):225–237.

Agenesis of the Cranial Nerves and Dysgenesis of the Posterior Fossa

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

The classification of disorders of development of the cranial nerve, brainstem, and cerebellum remains anatomic, but future classification systems will likely be based on the molecular biology of brain development based on the genes involved and the roles they play in orchestrating brain architecture.

Congenital Cranial Dysinnervation Disorders

Absence of the cranial nerves or the corresponding central nuclei has been described in several conditions and includes optic nerve defects, congenital ptosis, Marcus Gunn phenomenon (sucking jaw movements causing simultaneous eyelid blinking; this congenital synkinesis results from abnormal innervation of the trigeminal and oculomotor nerves), defects of the trigeminal and auditory nerves, and defects of cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII. Increased understanding of these disorders and their genetic causes has led to the term congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders.

Optic nerve hypoplasia can occur in isolation or as part of the septooptic dysplasia complex (de Morsier syndrome). Septooptic dysplasia can be caused by a mutation in the HESX1 gene. Möbius syndrome is characterized by bilateral facial weakness, which is often associated with paralysis of the abducens nerve. Hypoplasia or agenesis of brainstem nuclei, as well as absent or decreased numbers of muscle fibers, has been reported. Affected infants present in the newborn period with facial weakness, causing feeding difficulties owing to a poor suck. The immobile, dull facies might give the incorrect impression of intellectual impairment; the prognosis for normal development is excellent in most cases. The facial appearance of Möbius syndrome has been improved by facial surgery.

Duane retraction syndrome is characterized by congenital limitation of horizontal globe movement and some globe retraction on attempted adduction and is believed to be the result of abnormal innervation by the oculomotor nerve to the lateral rectus muscle. Abnormalities of cranial nerve development have been demonstrated in this condition.

Less common than Duane retraction syndrome and Möbius syndrome are the group of disorders known as congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles. Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles is characterized by severe restriction of eye movements and ptosis from abnormal oculomotor and trochlear nerve development and/or from abnormalities of extraocular muscle innervation.

Brainstem and Cerebellar Disorders

Disorders of the posterior fossa structures include abnormalities not only of the brainstem and cerebellum, but also of the CSF spaces. Commonly encountered malformations include Chiari malformation, Dandy-Walker malformation, arachnoid cysts, mega cisterna magna, persisting Blake pouch, Joubert syndrome, rhombencephalosynapsis, Lhermitte-Duclos disease, and the pontocerebellar hypoplasias.

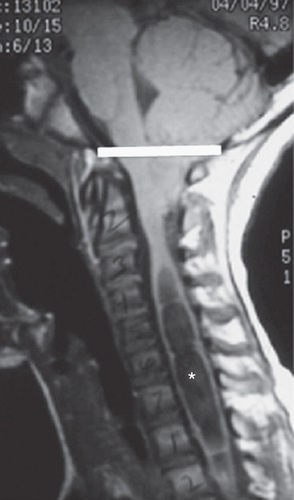

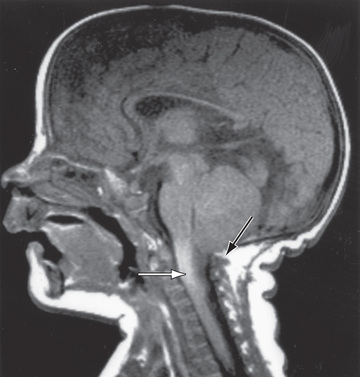

Chiari malformation is the most common malformation of the posterior fossa and hindbrain. It consists of herniation of the cerebellar tonsils though the foramen magnum (see Fig. 609.14 ). Often, there is also an associated developmental abnormality of the bones of the skull base leading to a small posterior fossa. Cases can be either asymptomatic or symptomatic. Chiari malformations may be isolated or seen in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, cystinosis, or other bone of connected tissue disorders. When symptoms develop, they often do not do so until late childhood. Symptoms include headaches that are worse with straining and other maneuvers that increase intracranial pressure. Symptoms of brainstem compression such as diplopia, oropharyngeal dysfunction, spasticity, tinnitus, and vertigo can occur. Obstructive hydrocephalus and/or syringomyelia can also occur (see Fig. 609.14 ).

Dandy-Walker malformation is part of a continuum of posterior fossa anomalies that include cystic dilation of the fourth ventricle, hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, hydrocephalus, and an enlarged posterior fossa with elevation of the lateral venous sinuses and the tentorium. Extracranial anomalies are also seen. Variable degrees of neurologic impairment are usually present. The etiology of Dandy-Walker malformation includes chromosomal abnormalities, single gene disorders, and exposure to teratogens.

Arachnoid cysts of the posterior fossa can be associated with hydrocephalus. Mega cisterna magna is characterized by an enlarged CSF space inferior and dorsal to the cerebellar vermis and when present in isolation may be considered a normal variant. Persisting Blake pouch is a cyst that obstructs the subarachnoid space and is associated with hydrocephalus.

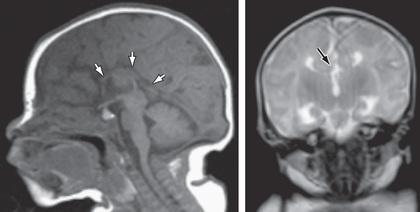

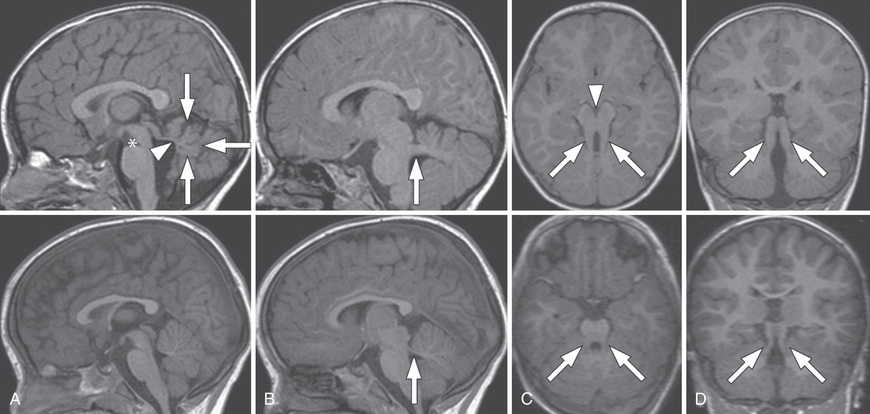

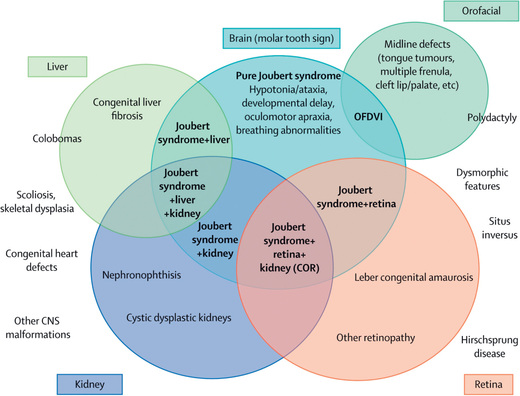

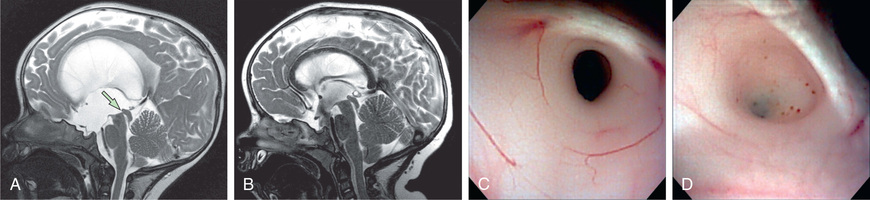

Joubert syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder (ciliopathy) with significant genetic heterogeneity that is associated with cerebellar vermis hypoplasia and the pontomesencephalic molar tooth sign (a deepening of the interpeduncular fossa with thick and straight superior cerebellar peduncles) (Fig. 609.12 ). It is associated with hypotonia, ataxia (as toddler), characteristic breathing abnormalities including episodic apnea and hyperpnea (which improves with age), global developmental delay, nystagmus, strabismus, ptosis, and oculomotor apraxia. There can be many associated systemic features (Joubert syndrome and related disorders), including progressive retinal dysplasia (Leber congenital amaurosis), coloboma, congenital heart disease, microcystic kidney disease, liver fibrosis, polydactyly, tongue protrusion, and soft tissue tumors of the tongue (Fig. 609.13 ).

Rhombencephalosynapsis is an absent or small vermis associated with a nonseparation or fusion of the deep midline cerebellar structures. Ventriculomegaly or hydrocephalus is often seen. There is a variable clinical presentation from normal function to cognitive and language impairments, epilepsy, and spasticity. Lhermitte-Duclos disease is a dysplastic gangliocytoma of the cerebellum leading to focal enlargement of the cerebellum and macrocephaly, cerebellar signs, and seizures.

Pontocerebellar hypoplasias are a group of disorders characterized by impairment of cerebellar and pontine development together with histopathologic features of neuronal death and glial replacement. Clinical features tend to be nonspecific and include hypotonia, feeding difficulties, developmental delay, and breathing difficulties. Classification, associations, and causes include type I (with features of anterior horn cell involvement), type II (with extrapyramidal features, seizures, and acquired microcephaly), Walker-Warburg syndrome, muscle–eye–brain disease, congenital disorders of glycosylation type 1A, mitochondrial cytopathies, teratogen exposure, congenital cytomegalovirus infection, 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, PEHO syndrome (progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy), autosomal recessive cerebellar hypoplasia in the Hutterite population, lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia, and other subtypes of pontocerebellar hypoplasia.

Bibliography

Bolduc M, Limperopoulos C. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with cerebellar malformations: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2009;51:256–267.

Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM. Joubert syndrome and related disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2010;5(20):1–10.

Huang H, Hwang CW, Lai PH, et al. Möbius syndrome as a syndrome of rhombencephalic maldevelopment: a case report. Pediatr Neonatol . 2009;50:36–38.

Hwang JY, Yoon HK, Lee JH, et al. Cranial nerve disorders in children: MR imaging findings. Radiographics . 2016;36(4):1178–1194.

Jaspan T. New concepts on posterior fossa malformations. Pediatr Radiol . 2008;38:S409–S414.

Khalsa SSS, Siu A, DeFreitas TA, et al. Comparison of posterior fossa volumes and clinical outcomes after decompression of chiari malformation type I. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2017;19(5):511–517.

Long A, Moran P, Robson S. Outcome of fetal cerebral posterior fossa anomalies. Prenat Diagn . 2006;26:707–710.

Martinez-Lage JF, Guillen-Navarro E, Lopez-Guerrero A, et al. Chiari type 1 anomaly in pseudohypoparathyroidism type ia: pathogenetic hypothesis. Childs Nerv Syst . 2011;27:2035–2039.

Maso AF, Poca MA, de la Calzada MD, et al. Sleep disturbance: a forgotten syndrome in patients with chiari I malformation. Neurologia . 2014;29(5):294–304.

Milhorat TH, Bolognese PA, Nishikawa M, et al. Syndrome of occipitoatlantoaxial hypermobility, cranial settling, and chiari malformation type I in patients with hereditary disorders of connective tissue. J Neurosurg Spine . 2007;7:601–609.

Poretti A, Ashmawy R, Garzon-Muvdi T, et al. Chiari type 1 deformity in children: pathogenetic, Clinical, Neuroimaging, and management aspects. Neuropediatrics . 2016;47(5):293–307.

Rao KI, Hesselink J, Trauner DA. Chiari I malformation in nephropathic cystinosis. J Pediatr . 2015;167:1126–1129.

Raza-Knight S, Mankad K, Prabhakar P, et al. Headache outcomes in children undergoing foramen magnum decompression for chiari I malformation. Arch Dis Child . 2017;102(3):238–243.

Romani M, Micalizzi A, Valente EM. Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurol . 2013;12:894–905.

Sasaki-Adams D, Elbabaa SK, Jewells V, et al. The Dandy-walker variant: a case series of 24 pediatric patients and evaluation of associated anomalies, incidence of hydrocephalus, and developmental outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2008;2:194–199.

Traboulsi EI. Congenital abnormalities of cranial nerve development: overview, molecular mechanisms, and further evidence of heterogeneity and complexity of syndromes with congenital limitation of eye movements. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc . 2004;102:373–389.

Vandertop WP. Syringomyelia. Neuropediatrics . 2013;45:3–9.

Microcephaly

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Microcephaly is defined as a head circumference that measures more than 3 SD below the mean for age and sex. This condition is relatively common, particularly among developmentally delayed children. Although there are many causes of microcephaly, abnormalities in neuronal migration during fetal development, including heterotopias of neuronal cells and cytoarchitectural derangements, are often found. Microcephaly may be subdivided into two main groups: primary (genetic) microcephaly and secondary (nongenetic) microcephaly. A precise diagnosis is important for genetic counseling and for prediction of future pregnancies.

Etiology

Primary microcephaly refers to a group of conditions that usually have no associated malformations and that follow a mendelian pattern of inheritance or are associated with a specific genetic syndrome. Affected infants are usually identified at birth because of a small head circumference. The more common types include familial and autosomal dominant microcephaly and a series of chromosomal syndromes that are summarized in Table 609.4 . Primary microcephaly is also associated with seven gene loci, and at least seven single etiologic genes have been identified; the condition has autosomal recessive inheritance. Many X-linked causes of microcephaly are caused by gene mutations that lead to severe structural brain malformations, such as lissencephaly, holoprosencephaly, polymicrogyria, cobblestone dysplasia, neuronal heterotopia, and pontocerebellar hypoplasia; these findings should be sought on MRI. Secondary microcephaly results from a large number of noxious agents that can affect a fetus in utero or an infant during periods of rapid brain growth, particularly the first 2 yr of life, pregnancy-associated Zika virus infection being the most recent example.

Table 609.4

| CAUSES | CHARACTERISTIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| PRIMARY (GENETIC) | |

| Familial (autosomal recessive) |

Incidence 1 in 40,000 live births Typical appearance with slanted forehead, prominent nose and ears; severe mental retardation and prominent seizures; surface convolutional markings of the brain; poorly differentiated and disorganized cytoarchitecture |

| Autosomal dominant |

Nondistinctive facies, upslanting palpebral fissures, mild forehead slanting, and prominent ears Normal linear growth, seizures readily controlled, and mild or borderline mental retardation |

| Syndromes | |

| Down (trisomy 21) |

Incidence 1 in 800 live births Abnormal rounding of occipital and frontal lobes and a small cerebellum; narrow superior temporal gyrus, propensity for Alzheimer neurofibrillary alterations, ultrastructure abnormalities of cerebral cortex |

| Edward (trisomy 18) |

Incidence 1 in 6,500 live births Low birthweight, microstomia, micrognathia, low-set malformed ears, prominent occiput, rocker-bottom feet, flexion deformities of fingers, congenital heart disease, increased gyri, heterotopias of neurons |

| Cri-du-chat (5 p-) |

Incidence 1 in 50,000 live births Round facies, prominent epicanthic folds, low-set ears, hypertelorism, characteristic cry No specific neuropathology |

| Cornelia de Lange |

Prenatal and postnatal growth delay; synophrys; thin, downturning upper lip Proximally placed thumb |

| Rubinstein-Taybi | Beaked nose, downward slanting of palpebral fissures, epicanthic folds, short stature, broad thumbs and toes |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz |

Ptosis, scaphocephaly, inner epicanthic folds, anteverted nostrils Low birthweight, marked feeding problems |

| SECONDARY (NONGENETIC) | |

| Congenital Infections | |

| Zika virus | Small for dates, ocular anomalies |

| Cytomegalovirus |

Small for dates, petechial rash, hepatosplenomegaly, chorioretinitis, deafness, mental retardation, seizures CNS calcification and microgyria |

| Rubella |

Growth retardation, purpura, thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, congenital heart disease, chorioretinitis, cataracts, deafness Perivascular necrotic areas, polymicrogyria, heterotopias, subependymal cavitations |

| Toxoplasmosis | Purpura, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, convulsions, hydrocephalus, chorioretinitis, cerebral calcification |

| Drugs | |

| Fetal alcohol | Growth retardation, ptosis, absent philtrum and hypoplastic upper lip, congenital heart disease, feeding problems, neuroglial heterotopia, disorganization of neurons |

| Fetal hydantoin | Growth delay, hypoplasia of distal phalanges, inner epicanthic folds, broad nasal ridge, anteverted nostrils |

| Other Causes | |

| Radiation | Microcephaly and mental retardation most severe with exposure before 15th wk of gestation |

| Meningitis/encephalitis | Cerebral infarcts, cystic cavitation, diffuse loss of neurons |

| Malnutrition | Controversial cause of microcephaly |

| Metabolic | Maternal diabetes mellitus and maternal hyperphenylalaninemia |

| Hyperthermia |

Significant fever during first 4-6 wk has been reported to cause microcephaly, seizures, and facial anomalies Pathologic studies show neuronal heterotopias Further studies show no abnormalities with maternal fever |

| Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy | Initially diffuse cerebral edema; late stages characterized by cerebral atrophy and abnormal signals on MRI |

Acquired microcephaly can be seen in conditions such as Rett, Seckel, and Angelman syndromes and in encephalopathy syndromes associated with severe seizure disorders.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

A thorough family history should be taken, seeking additional cases of microcephaly or disorders affecting the nervous system. It is important to measure a patient's head circumference at birth to diagnose microcephaly as early as possible. A very small head circumference implies a process that began early in embryonic or fetal development. An insult to the brain that occurs later in life, particularly beyond the age of 2 yr, is less likely to produce severe microcephaly. Serial head circumference measurements are more meaningful than a single determination, particularly when the abnormality is minimal or the microcephaly is acquired. The head circumference of each parent and sibling should be recorded.

Laboratory investigation of a microcephalic child is determined by the history and physical examination. If the cause of the microcephaly is unknown, the mother's serum phenylalanine level should be determined. High phenylalanine serum levels in an asymptomatic mother can produce marked brain damage in an otherwise normal nonphenylketonuric infant. Newborn screening in the United States will detect most of these cases. A karyotype and/or array comparative genomic hybridization (chromosome microarray) study is obtained if a chromosomal syndrome is suspected or if the child has abnormal facies, short stature, and additional congenital anomalies. MRI is useful in identifying structural abnormalities of the brain, such as lissencephaly, pachygyria, and polymicrogyria, and CT scanning is useful to detect intracerebral calcification. Additional studies include a fasting plasma and urine amino acid and organic acid analysis; serum ammonia determination; to xoplasmosis, r ubella, c ytomegalovirus, and h erpes simplex (TORCH) titers as well as HIV testing of the mother and child; and a urine sample for the culture of cytomegalovirus. Zika virus–specific testing is also indicated when the infant is born in a high-risk environment or a parent has a history of travel to endemic areas. Single-gene mutations as a cause of both primary microcephaly and syndromic microcephaly are being increasingly identified.

Treatment

Once the cause of microcephaly has been established, the physician must provide accurate and supportive genetic and family counseling. Because many children with microcephaly are also intellectually challenged, the physician must assist with placement in an appropriate program that will provide for maximal development of the child (see Chapter 53 ).

Bibliography

Abuelo D. Microcephaly syndromes. Semin Pediatr Neurol . 2007;14:118–127.

Auger N, Quach C, Healy-Profitos J, et al. Congenital microencephaly in Quebec: baseline prevalence, risk factors and outcomes in a large cohort of neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2017;103(3):F167–F172.

Barkovich AJ, Kuzniecky RI, Jackson MD, et al. Classification system for malformations of cortical development. Neurology . 2001;57:2168–2178.

Clark GD. The classification of cortical dysplasias through molecular genetics. Brain Dev . 2004;26:351–362.

Denis D, Chateil JF, Brun M, et al. Schizencephaly: clinical and imaging features in 30 infantile cases. Brain Dev . 2000;22:475–483.

D'Orsi G, Tinuper P, Bisulli F, et al. Clinical features and long term outcome of epilepsy in periventricular nodular heterotopia. Simple compared with plus forms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . 2004;75:873–878.

Hayashi N, Tsutsumi Y, Barkovich AJ. Morphological features and associated anomalies of schizencephaly in the clinical population: detailed analysis of MR images. Neuroradiology . 2002;44:418–427.

Kinsman SL, Plawner LL, Hahn JS. Holoprosencephaly: recent advances and insights. Curr Opin Neurol . 2000;13:127–132.

Parrish ML, Roessmann U, Levinsohn MW. Agenesis of the corpus callosum: a study of the frequency of associated malformations. Ann Neurol . 1979;6:349–354.

Richards LJ, Plachez C, Ren T. Mechanisms regulating the development of the corpus callosum and its agenesis in mouse and human. Clin Genet . 2004;66:276–289.

Silva AA, Barbieri MA, Alves MT, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for microcephaly at birth in Brazil in. Pediatrics . 2010;141(2):e20170589–e20172018.

Woods CG, Bond J, Enard W. Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH): a review of clinical, molecular, and evolutionary findings. Am J Hum Genet . 2005;76:717–728.

Hydrocephalus

Stephen L. Kinsman, Michael V. Johnston

Hydrocephalus is not a specific disease; it represents a diverse group of conditions that result from impaired circulation and/or absorption of CSF or, in rare circumstances, from increased production of CSF by a choroid plexus papilloma (Tables 609.5 and 609.6 ). Because megalencephaly is often discovered as part of an evaluation for hydrocephalus in children with macrocephaly, it is included in this section.

Table 609.5

Causes of Pediatric Hydrocephalus

| CAUSE | PROPOSED MECHANISM | |

|---|---|---|

| ACQUIRED HYDROCEPHALUS | ||

| Inflammatory | ||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage or infection | Arachnoid scar | Dysfunctional subarachnoid space |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage or infection | Ependymal scar | Ventricular obstruction |

| Neoplasm | ||

| Parenchymal brain tumor | Mass effect | Ventricular obstruction |

| Spinal cord tumor | Altered CSF composition | Dysfunctional subarachnoid space |