Developmental Delay and Intellectual Disability

Bruce K. Shapiro, Meghan E. O'Neill

Intellectual disability (ID) refers to a group of disorders that have in common deficits of adaptive and intellectual function and an age of onset before maturity is reached.

Definition

Contemporary conceptualizations of ID emphasize functioning and social interaction rather than test scores. The definitions of ID by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), the U.S. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), and the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) all include significant impairment in general intellectual function (reasoning, learning, problem solving), social skills, and adaptive behavior. This focus on conceptual, social, and practical skills enables the development of individual treatment plans designed to enhance functioning. Consistent across these definitions is onset of symptoms before age 18 yr or adulthood.

Significant impairment in general intellectual function refers to performance on an individually administered test of intelligence that is approximately 2 standard deviations (SD) below the mean. Generally these tests provide a standard score that has a mean of 100 and SD of 15, so that intelligence quotient (IQ) scores <70 would meet these criteria. If the standard error of measurement is considered, the upper limits of significantly impaired intellectual function may extend to an IQ of 75. Using a score of 75 to delineate ID might double the number of children with this diagnosis, but the requirement for impairment of adaptive skills limits the false positives. Children with ID often show a variable pattern of strengths and weaknesses. Not all their subtest scores on IQ tests fall into the significantly impaired range.

Significant impairment in adaptive behavior reflects the degree that the cognitive dysfunction impairs daily function. Adaptive behavior refers to the skills required for people to function in their everyday lives. The AAIDD and DSM-5 classifications of adaptive behavior addresses three broad sets of skills: conceptual, social, and practical. Conceptual skills include language, reading, writing, time, number concepts, and self-direction. Social skills include interpersonal skills, personal and social responsibility, self-esteem, gullibility, naiveté, and ability to follow rules, obey laws, and avoid victimization. Representative practical skills are performance of activities of daily living (dressing, feeding, toileting/bathing, mobility), instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., housework, managing money, taking medication, shopping, preparing meals, using phone), occupational skills, and maintenance of a safe environment. For a deficit in adaptive behavior to be present, a significant delay in at least 1 of the 3 skill areas must be present. The rationale for requiring only 1 area is the empirically derived finding that people with ID can have varying patterns of ability and may not have deficits in all 3 areas.

The requirement for adaptive behavior deficits is the most controversial aspect of the diagnostic formulation. The controversy centers on two broad areas: whether impairments in adaptive behavior are necessary for the construct of ID, and what to measure. The adaptive behavior criterion may be irrelevant for many children; adaptive behavior is impaired in virtually all children who have IQ scores <50. The major utility of the adaptive behavior criterion is to confirm ID in children with IQ scores in the 65-75 range. It should be noted that deficits in adaptive behavior are often found in disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD; see Chapter 54 ) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; see Chapter 49 ) in the presence of typical intellectual function.

The issues of measurement are important as well. The independence of the 3 domains of adaptive behavior has not been validated. The relationship between adaptive behavior and IQ performance is insufficiently explored. Most adults with mild ID do not have significant impairments in practical skills. Adaptive behavior deficits also must be distinguished from maladaptive behavior (e.g., aggression, inappropriate sexual contact).

Onset before age 18 yr or adulthood distinguishes dysfunctions that originate during the developmental period. The diagnosis of ID may be made after 18 yr of age, but the cognitive and adaptive dysfunction must have been manifested before age 18.

The term “mental retardation” should not be used because it is stigmatizing, has been used to limit the achievements of the individual, and has not met its initial objective of assisting people with the disorder. The term intellectual disability is increasingly used in its place, but has not been adopted universally. In the United States, Rosa's law (Public Law 111-256) was passed in 2010 and now mandates that the term mental retardation be stripped from federal health, education, and labor policy. As of 2013, at least 9 states persist in using the outdated terminology. In Europe the term learning disability is often used to describe ID.

Global developmental delay (GDD) is a term often used to describe young children whose limitations have not yet resulted in a formal diagnosis of ID. In DSM-5, GDD is a diagnosis given to children <5 yr of age who display significant delay (>2 SD) in acquiring early childhood developmental milestones in 2 or more domains of development. These domains include receptive and expressive language, gross and fine motor function, cognition, social and personal development, and activities of daily living. Typically, it is assumed that delay in 2 domains will be associated with delay across all domains evaluated, but this is not always the case. Furthermore, not all children who meet criteria for a GDD diagnosis at a young age go on to meet criteria for ID after age 5 yr. Reasons for this might include maturational effects, a change in developmental trajectory (possibly from an intervention), reclassification to a different disability category, or imprecise use of the GDD diagnosis initially. Conversely, in patients with more severe delay, the GDD term is often inappropriately used beyond the point when the child clearly has ID, often by 3 yr of age.

It is important to distinguish the medical diagnosis of GDD from the federal disability classification of “developmental delay” that may be used by education agencies under IDEA. This classification requires that a child have delays in only 1 domain of development with subsequent need for special education. Each state determines its own precise definition and terms of eligibility under the broader definition outline by IDEA, and many states use the label for children up to age 9 yr.

Etiology

Numerous identified causes of ID may occur prenatally, during delivery, postnatally, or later in childhood. These include infection, trauma, prematurity, hypoxia-ischemia, toxic exposures, metabolic dysfunction, endocrine abnormalities, malnutrition, and genetic abnormalities. However, more than two thirds of persons with ID will not have a readily identifiable underlying diagnosis that can be linked to their clinical presentation, meriting further medical evaluation. For those who then undergo further genetic and metabolic workup, about two thirds will have an etiology that is subsequently discovered. There does appear to be 2 overlapping populations of children with ID with differing corresponding etiologies. Mild ID (IQ 50-70) is associated more with environmental influences, with the highest risk among children of low socioeconomic status. Severe ID (IQ <50) is more frequently linked to biologic and genetic causes. Accordingly, diagnostic yield is generally higher among persons with more severe disability (>75%) than among those with mild disability (<50%). With continued advancement of technologic standards and expansion of our knowledge base, the number of identified biologic and genetic causes is expected to increase.

Nongenetic risk factors that are often associated with mild ID include low socioeconomic status, residence in a developing country, low maternal education, malnutrition, and poor access to healthcare. The most common biologic causes of mild ID include genetic or chromosomal syndromes with multiple, major, or minor congenital anomalies (e.g., velocardiofacial, Williams, and Noonan syndromes), intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity, perinatal insults, intrauterine exposure to drugs of abuse (including alcohol), and sex chromosomal abnormalities. Familial clustering is common.

In children with severe ID, a biologic cause (usually prenatal) can be identified in about three fourths of all cases. Causes include chromosomal (e.g., Down, Wolf-Hirschhorn, and deletion 1p36 syndromes) and other genetic and epigenetic disorders (e.g., fragile X, Rett, Angelman, and Prader-Willi syndromes), abnormalities of brain development (e.g., lissencephaly), and inborn errors of metabolism or neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., mucopolysaccharidoses) (Table 53.1 ). Nonsyndromic severe ID may be a result of inherited or de novo gene mutations, as well as microdeletions or microduplications not detected on standard chromosome analysis. Currently, >700 genes are associated with nonsyndromic ID. Inherited genetic abnormalities may be mendelian (autosomal dominant de novo, autosomal recessive, X-linked) or nonmendelian (imprinting, methylation, mitochondrial defects; see Chapter 97 ). De novo mutations may also cause other phenotypic features such as seizures or autism; the presence of these features suggests more pleotropic manifestations of genetic mutations. Consistent with the finding that disorders altering early embryogenesis are the most common and severe, the earlier the problem occurs in development, the more severe its consequences tend to be.

Table 53.1

Adapted from Stromme P, Hayberg G: Aetiology in severe and mild mental retardation: a population based study of Norwegian children, Dev Med Child Neurol 42:76–86, 2000.

Etiologic workup is recommended in all cases of GDD or ID. Although there are only about 80 disorders (all of which are metabolic in nature) for which treatment may ameliorate the core symptoms of ID, several reasons beyond disease modification should prompt providers to seek etiologic answers in patients with ID. These include insight into possible associated medical or behavioral comorbidities; information on prognosis and life expectancy; estimation of recurrence risk for family planning counseling, potential validation, and closure for the family; increased access to services or specific supports; and better understanding of underlying pathology with the hope of new eventual treatment options. When surveyed, families of children with ID with no identified underlying etiology almost universally report that they would want to know of an etiologic diagnosis if given the choice.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of ID depends on the definition, method of ascertainment, and population studied, both in terms of geography and age. According to the statistics of a normal distribution, 2.5% of the population should have ID (based on IQ alone), and 75% of these individuals should fall into the mild to moderate range. Variability in rates across populations likely results from the heavy influence of external environmental factors on the prevalence of mild ID. The prevalence of severe ID is relatively stable. Globally, the prevalence of ID has been estimated to be approximately 16.4 per 1,000 persons in low-income countries, approximately 15.9/1,000 for middle-income countries, and approximately 9.2/1,000 in high-income countries. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies from 1980–2009 yielded an overall prevalence of 10.4/1000. ID occurs more in boys than in girls, at 2 : 1 in mild ID and 1.5 : 1 in severe ID. In part this may be a consequence of the many X-linked disorders associated with ID, the most prominent being fragile X syndrome (see Chapter 98.5 ).

In 2014–2015 in the United States, approximately 12/1000 students 3-5 yr old and 6.2/1000 students 6-21 yr old received services for ID in federally supported school programs. In 2012 the National Survey of Children's Health reported an estimated prevalence of ID among American children (age 2-17 yr) of 1.1%. For several reasons, fewer children than predicted are identified as having mild ID. Because it is more difficult to diagnose mild ID than the more severe forms, professionals might defer the diagnosis and give the benefit of the doubt to the child. Other reasons that contribute to the discrepancy are use of instruments that underidentify young children with mild ID, children diagnosed as having ASD without their ID being addressed, misdiagnosis as a language disorder or specific learning disability, and a disinclination to make the diagnosis in poor or minority students because of previous overdiagnosis. In some cases, behavioral disorders may divert the focus from the cognitive dysfunction.

Beyond potential underdiagnosis of mild ID, the number of children with mild ID may be decreasing as a result of public health and education measures to prevent prematurity and provide early intervention and Head Start programs. However, although the number of schoolchildren who receive services under a federal disability classification of ID has decreased since 1999, when developmental delay is included in analysis of the data, the numbers have not changed appreciably.

The prevalence of severe ID has not changed significantly since the 1940s, accounting for 0.3–0.5% of the population. Many of the causes of severe ID involve genetic or congenital brain malformations that can neither be anticipated nor treated at present. In addition, new populations with severe ID have offset the decreases in the prevalence of severe ID that have resulted from improved healthcare. Although prenatal diagnosis and subsequent pregnancy terminations could lead to a decreasing incidence of Down syndrome (see Chapter 98.2 ), and newborn screening with early treatment has virtually eliminated ID caused by phenylketonuria and congenital hypothyroidism, continued high prevalence of fetal exposure to illicit drugs and improved survival of very-low-birthweight premature infants has counterbalanced this effect.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The limitations in our knowledge of the neuropathology of ID are exemplified by 10–20% of brains of persons with severe ID appearing entirely normal on standard neuropathologic study. Most of these brains show only mild, nonspecific changes that correlate poorly with the degree of ID, including microcephaly, gray matter heterotopias in the subcortical white matter, unusually regular columnar arrangement of the cortex, and neurons that are more tightly packed than usual. Only a minority of the brain shows more specific changes in dendritic and synaptic organization, with dysgenesis of dendritic spines or cortical pyramidal neurons or impaired growth of dendritic trees. The programming of the central nervous system (CNS) involves a process of induction ; CNS maturation is defined in terms of genetic, molecular, autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine influences. Receptors, signaling molecules, and genes are critical to brain development. The maintenance of different neuronal phenotypes in the adult brain involves the same genetic transcripts that play a crucial role in fetal development, with activation of similar intracellular signal transduction mechanisms.

As the ability to identify genetic aberrations that correspond to particular phenotypes expands through the use of next-generation sequencing, more will be elucidated about the pathogenesis of ID at a genetic and molecular level. This expanding pathophysiologic knowledge base may serve as a framework with which to develop targeted therapies to bypass or correct newly identified defects. For example, use of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors has been shown to rescue structural and functional neural deficits in mouse models of Kabuki syndrome, a disorder of histone methylation that leads to variable levels of ID and characteristic facial features (see Chapter 100 ).

Clinical Manifestations

Early diagnosis of ID facilitates earlier intervention, identification of abilities, realistic goal setting, easing of parental anxiety, and greater acceptance of the child in the community. Most children with ID first come to the pediatrician's attention in infancy because of dysmorphisms, associated developmental disabilities, or failure to meet age-appropriate developmental milestones (Tables 53.2 and 53.3 ). There are no specific physical characteristics of ID, but dysmorphisms may be the earliest signs that bring children to the attention of the pediatrician. They might fall within a genetic syndrome such as Down syndrome or might be isolated, as in microcephaly or failure to thrive. Associated developmental disabilities include seizure disorders, cerebral palsy, and ASD.

Table 53.2

Physical Examination of a Child With Suspected Developmental Disabilities

| ITEM | POSSIBLE SIGNIFICANCE |

|---|---|

| General appearance | May indicate significant delay in development or obvious syndrome |

| Stature | |

| Short stature | Malnutrition, many genetic syndromes are associated with short stature (e.g., Turner, Noonan) |

| Obesity | Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Large stature | Sotos syndrome |

| Head | |

| Macrocephaly | Alexander syndrome, Canavan disease, Sotos syndrome, gangliosidosis, hydrocephalus, mucopolysaccharidosis, subdural effusion |

| Microcephaly | Virtually any condition that can restrict brain growth (e.g., malnutrition, Angelman syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, fetal alcohol effects) |

| Face | |

| Coarse, triangular, round, or flat face; hypotelorism or hypertelorism; slanted or short palpebral fissure; unusual nose, maxilla, and mandible | Specific measurements may provide clues to inherited, metabolic, or other diseases such as fetal alcohol syndrome, cri du chat (5p−) syndrome, or Williams syndrome. |

| Eyes | |

| Prominent | Crouzon, Seckel, and fragile X syndromes |

| Cataract | Galactosemia, Lowe syndrome, prenatal rubella, hypothyroidism |

| Cherry-red spot in macula | Gangliosidosis (GM1 ), metachromatic leukodystrophy, mucolipidosis, Tay-Sachs disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Farber lipogranulomatosis, sialidosis type III |

| Chorioretinitis | Congenital infection with cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, Zika virus, or rubella |

| Corneal cloudiness | Mucopolysaccharidosis types I and II, Lowe syndrome, congenital syphilis |

| Ears | |

| Low-set or malformed pinnae | Trisomies such as Down syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, cerebrooculofacioskeletal syndrome, fetal phenytoin effects |

| Hearing | Loss of acuity in mucopolysaccharidosis; hyperacusis in many encephalopathies |

| Heart | |

| Structural anomaly or hypertrophy | CHARGE syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, glycogenosis type II, fetal alcohol effects, mucopolysaccharidosis type I; chromosomal anomalies such as Down syndrome; maternal PKU; chronic cyanosis may impair cognitive development. |

| Liver | |

| Hepatomegaly | Fructose intolerance, galactosemia, glycogenosis types I-IV, mucopolysaccharidosis types I and II, Niemann-Pick disease, Tay-Sachs disease, Zellweger syndrome, Gaucher disease, ceroid lipofuscinosis, gangliosidosis |

| Genitalia | |

| Macroorchidism | Fragile X syndrome |

| Hypogenitalism | Prader-Willi, Klinefelter, and CHARGE syndromes |

| Extremities | |

| Hands, feet; dermatoglyphics, creases | May indicate a specific entity such as Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome or may be associated with chromosomal anomaly |

| Joint contractures | Signs of muscle imbalance around the joints; e.g., with meningomyelocele, cerebral palsy, arthrogryposis, muscular dystrophy; also occurs with cartilaginous problems such as mucopolysaccharidosis |

| Skin | |

| Café au lait spots |

Neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, chromosomal aneuploidy, ataxia-telangiectasia, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b Fanconi anemia, Gaucher disease Syndromes: basal cell nevus, McCune-Albright, Silver-Russell, Bloom, Chediak-Higashi, Hunter, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba, Maffucci |

| Seborrheic or eczematoid rash | PKU, histiocytosis |

| Hemangiomas and telangiectasia | Sturge-Weber syndrome, Bloom syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Hypopigmented macules, streaks, adenoma sebaceum | Tuberous sclerosis, hypomelanosis of Ito |

| Hair | |

| Hirsutism | De Lange syndrome, mucopolysaccharidosis, fetal phenytoin effects, cerebrooculofacioskeletal syndrome, trisomy 18, Wiedemann-Steiner syndrome (hypertrichosis cubiti) |

| Neurologic | |

| Asymmetry of strength and tone | Focal lesion, hemiplegic cerebral palsy |

| Hypotonia | Prader-Willi, Down, and Angelman syndromes; gangliosidosis; early cerebral palsy; muscle disorders (dystrophy or myopathy) |

| Hypertonia | Neurodegenerative conditions involving white matter, cerebral palsy, trisomy 18 |

| Ataxia | Ataxia-telangiectasia, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Angelman syndrome |

CHARGE, Coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, retarded growth, genital anomalies, ear anomalies (deafness); CATCH-22, cardiac defects, abnormal face, thymic hypoplasia, cleft palate, hypocalcemia—defects on chromosome 22; PKU, phenylketonuria.

From Simms M: Intellectual and developmental disability. In Kliegman RM, Lye PS, Bordini BJ, et al, editors: Nelson pediatric symptom-based diagnosis, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier, Table 24.11, p 376.

Table 53.3

| AREA | ANOMALY/SYNDROME |

|---|---|

| Head |

Flat occiput: Down syndrome, Zellweger syndrome; prominent occiput: trisomy 18 Delayed closure of sutures: hypothyroidism, hydrocephalus Craniosynostosis: Crouzon syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome Delayed fontanel closure: hypothyroidism, Down syndrome, hydrocephalus, skeletal dysplasias |

| Face |

Midface hypoplasia: fetal alcohol syndrome, Down syndrome Triangular facies: Russell-Silver syndrome, Turner syndrome Coarse facies: mucopolysaccharidoses, Sotos syndrome Prominent nose and chin: fragile X syndrome Flat facies: Apert syndrome, Stickler syndrome Round facies: Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Eyes |

Hypertelorism: fetal hydantoin syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome Hypotelorism: holoprosencephaly sequence, maternal phenylketonuria effect Inner canthal folds/Brushfield spots: Down syndrome; slanted palpebral fissures: trisomies Prominent eyes: Apert syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome Lisch nodules: neurofibromatosis Blue sclera: osteogenesis imperfecta, Turner syndrome, hereditary connective tissue disorders |

| Ears |

Large pinnae/simple helices: fragile X syndrome Malformed pinnae/atretic canal: Treacher Collins syndrome, CHARGE syndrome Low-set ears: Treacher Collins syndrome, trisomies, multiple disorders |

| Nose |

Anteverted nares/synophrys: Cornelia de Lange syndrome; broad nasal bridge: fetal drug effects, fragile X syndrome Low nasal bridge: achondroplasia, Down syndrome Prominent nose: Coffin-Lowry syndrome, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome |

| Mouth |

Long philtrum/thin vermilion border: fetal alcohol effects Cleft lip and palate: isolated or part of a syndrome Micrognathia: Pierre Robin sequence, trisomies, Stickler syndrome Macroglossia: hypothyroidism, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome |

| Teeth |

Anodontia: ectodermal dysplasia Notched incisors: congenital syphilis Late dental eruption: Hunter syndrome, hypothyroidism Talon cusps: Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome Wide-spaced teeth: Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Angelman syndrome |

| Hair |

Hirsutism: Hurler syndrome Low hairline: Klippel-Feil sequence, Turner syndrome Sparse hair: Menkes disease, argininosuccinic acidemia Abnormal hair whorls/posterior whorl: chromosomal aneuploidy (e.g., Down syndrome) Abnormal eyebrow patterning: Cornelia de Lange syndrome |

| Neck | Webbed neck/low posterior hairline: Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome |

| Chest | Shield-shaped chest: Turner syndrome |

| Genitalia |

Macroorchidism: fragile X syndrome Hypogonadism: Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Extremities |

Short limbs: achondroplasia, rhizomelic chondrodysplasia Small hands: Prader-Willi syndrome Clinodactyly: trisomies, including Down syndrome Polydactyly: trisomy 13, ciliopathies Broad thumb: Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome Syndactyly: de Lange syndrome Transverse palmar crease: Down syndrome Joint laxity: Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Phocomelia: Cornelia de Lange syndrome |

| Spine | Sacral dimple/hairy patch: spina bifida |

| Skin |

Hypopigmented macules/adenoma sebaceum: tuberous sclerosis Café au lait spots and neurofibromas: neurofibromatosis Linear depigmented nevi: hypomelanosis of Ito Facial port-wine hemangioma: Sturge-Weber syndrome Nail hypoplasia or dysplasia: fetal alcohol syndrome, trisomies |

* Increased incidence of minor anomalies have been reported in cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, learning disabilities, and autism.

† The presence of 3 or more minor anomalies implies a greater chance that the child has a major anomaly and a diagnosis of a specific syndrome.

CHARGE, Coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, retarded growth, genital anomalies, ear anomalies (deafness).

Modified from Levy SE, Hyman SL. Pediatric assessment of the child with developmental delay, Pediatr Clin North Am 40:465-477, 1993.

Most children with ID do not keep up with their peers' developmental skills. In early infancy, failure to meet age-appropriate expectations can include a lack of visual or auditory responsiveness, unusual muscle tone (hypo- or hypertonia) or posture, and feeding difficulties. Between 6 and 18 mo of age, gross motor delay (lack of sitting, crawling, walking) is the most common complaint. Language delay and behavior problems are common concerns after 18 mo (Table 53.4 ). For some children with mild ID, the diagnosis remains uncertain during the early school years. It is only after the demands of the school setting increase over the years, changing from “learning to read” to “reading to learn,” that the child's limitations are clarified. Adolescents with mild ID are typically up to date on current trends and are conversant as to “who,” “what,” and “where.” It is not until the “why” and “how” questions are asked that their limitations become apparent. If allowed to interact at a superficial level, their mild ID might not be appreciated, even by professionals, who may be their special education teachers or healthcare providers. Because of the stigma associated with ID, adolescents may use euphemisms to avoid being thought of as “stupid” or “retarded” and may refer to themselves as learning disabled, dyslexic, language disordered, or slow learners. Some people with ID emulate their social milieu to be accepted. They may be social chameleons and assume the morals of the group to whom they are attached. Some would rather be thought “bad” than “incompetent.”

Table 53.4

Children with ID have a nonprogressive disorder; loss of developmental milestones or progressive symptoms suggest another disorder (see Chapter 53.1 ).

Diagnostic Evaluation

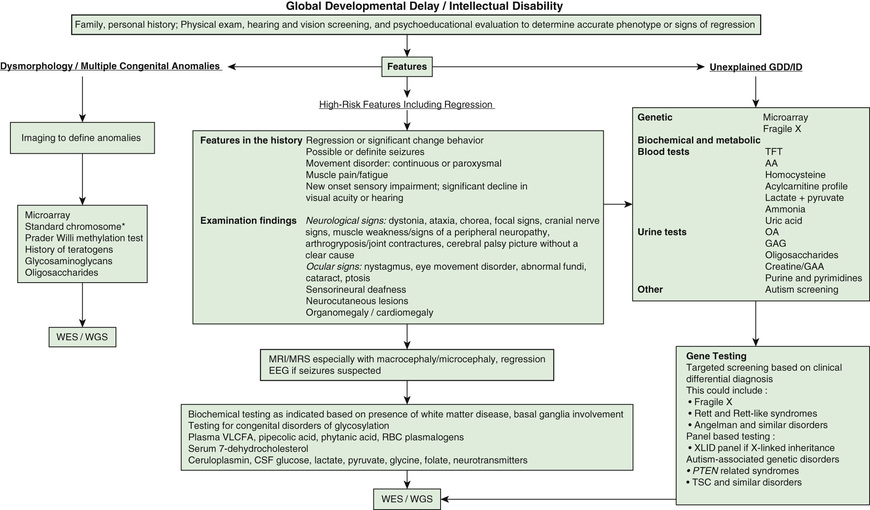

Intellectual disability is one of the most frequent reasons for referral to pediatric genetic providers, with separate but similar diagnostic evaluation guidelines put forth by the American College of Medical Genetics, the American Academy of Neurology, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. ID is a diagnosis of great clinical heterogeneity, with only a subset of syndromic etiologies identifiable through classic dysmorphology. If diagnosis is not made after conducting an appropriate history and physical examination, chromosomal microarray is the recommended first step in the diagnostic evaluation of ID. Next-generation sequencing represents the new diagnostic frontier, with extensive gene panels (exome or whole genome) that increase the diagnostic yield and usefulness of genetic testing in ID. Other commonly used medical diagnostic testing for children with ID includes neuroimaging, metabolic testing, and electroencephalography (Fig. 53.1 ).

Decisions to pursue an etiologic diagnosis should be based on the medical and family history, physical examination, and the family's wishes. Table 53.5 summarizes clinical practice guidelines and the yields of testing to assist in decisions about evaluating the child with GDD or ID. Yield of testing tends increase with worsening severity of delays.

Table 53.5

EEG, Electroencephalogram; CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; MECP2, methyl CpG–binding protein 2; T4 , thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Data from Michelson DJ et al: Evidence report. Genetic and metabolic testing on children with global developmental delay: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of Child Neurology, Neurology 77:1629-35, 2011; Curry CJ et al: Evaluation of mental retardation: recommendations of a Consensus Conference: American College of Medical Genetics, Am J Med Genet 12:72:468-477, 1997; Shapiro BK, Batshaw ML: Mental retardation. In Burg FD et al: Gellis and Kagan's current pediatric therapy , ed 18, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders; and Shevell M et al: Practice parameter: evaluation of the child with global developmental delay, Neurology 60:367–380, 2003.

Microarray analysis has replaced a karyotype as first-tier testing given that it discerns abnormalities that are far below the resolution of a karyotype. Microarray analysis may identify variants of unknown significance or benign variants and therefore should be used in conjunction with a genetic consultation. Karyotyping has a role when concerns for inversions, balanced insertions, and reciprocal translocations are present. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and subtelomeric analysis have been largely replaced by microarray analysis but are occasionally used for specific indications. If microarray analysis is not diagnostic, whole exome sequencing increases the diagnostic yield in many children with nonsyndromic severe ID. Starting with whole exome sequencing may be more cost-effective and may substantially reduce time to diagnosis with higher ultimate yields compared with the traditional diagnostic pathway.

Molecular genetic testing for fragile X syndrome is recommended for all children presenting with GDD. Yields are highest in males with moderate ID, unusual physical features, and/or a family history of ID, or for females with more subtle cognitive deficits associated with severe shyness and a relevant family history, including premature ovarian failure or later-onset ataxia-tremor symptoms. For children with a strong history of X-linked ID, specific testing of genes or the entire chromosome may be revealing. Testing for Rett syndrome (MECP2, methyl CpG–binding protein 2) should be considered in girls with moderate to severe disability.

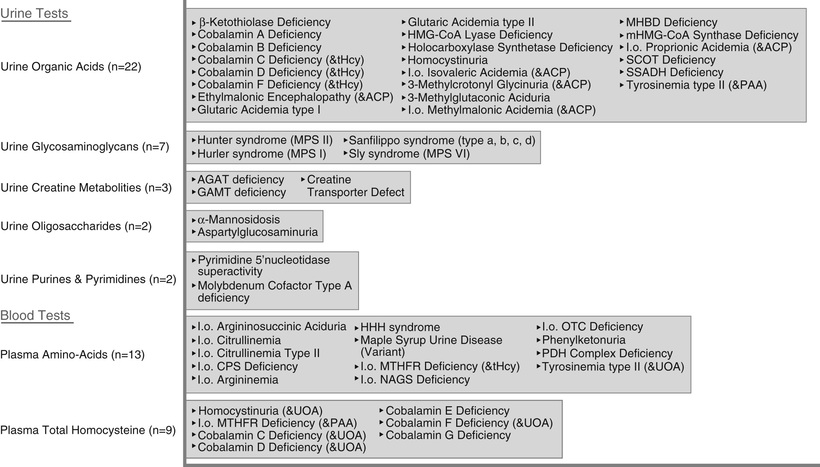

A child with a progressive neurologic disorder, developmental regression, or acute behavioral changes needs metabolic investigation as shown in Figure 53.1 . Some are advocating that metabolic testing should be done more frequently in children with ID because of the possibility of detecting a condition that could be treatable (Fig. 53.2 and Table 53.6 ). A child with seizure-like episodes should have an electroencephalogram (EEG), although this testing is generally not helpful outside the scope of ruling out seizures. MRI of the brain may provide useful information in directing the care of a child with micro- or macrocephaly, change in head growth trajectory, asymmetric head shape, new or focal neurologic findings, or seizure. MRI can detect a significant number of subtle markers of cerebral dysgenesis in children with ID, but these markers do not usually suggest a specific etiologic diagnosis.

Some children with subtle physical or neurologic findings can also have determinable biologic causes of their ID (see Tables 53.2 and 53.3 ). How intensively one investigates the cause of a child's ID is based on the following factors:

- ◆ What is the degree of delay, and what is the age of the child? If milder or less pervasive delays are present, especially in a younger child, etiologic yield is likely to be lower.

- ◆ Is the medical history, family history, or physical exam suggestive of a specific disorder, increasing the likelihood that a diagnosis will be made? Are the parents planning on having additional children, and does the patient have siblings? If so, one may be more likely to intensively seek disorders for which prenatal diagnosis or a specific early treatment option is available.

- ◆ What are the parents' wishes? Some parents have little interest in searching for the cause of the ID, whereas others become so focused on obtaining a diagnosis that they have difficulty following through on interventions until a cause has been found. The entire spectrum of responses must be respected, and supportive guidance should be provided in the context of the parents' education.

Differential Diagnosis

One of the important roles of pediatricians is the early recognition and diagnosis of cognitive deficits. The developmental surveillance approach to early diagnosis of ID should be multifaceted. Parents' concerns and observations about their child's development should be listened to carefully. Medical, genetic, and environmental risk factors should be recognized. Infants at high risk (prematurity, maternal substance abuse, perinatal insult) should be registered in newborn follow-up programs in which they are evaluated periodically for developmental lags in the 1st 2 yr of life; they should be referred to early intervention programs as appropriate. Developmental milestones should be recorded routinely during healthcare maintenance visits. The AAP has formulated a schema for developmental surveillance and screening (see Chapter 28 ).

Before making the diagnosis of ID, other disorders that affect cognitive abilities and adaptive behavior should be considered. These include conditions that mimic ID and others that involve ID as an associated impairment. Sensory deficits (severe hearing and vision loss), communication disorders, refractory seizure disorders, poorly controlled mood disorders, or unmanaged severe attention deficits can mimic ID; certain progressive neurologic disorders can appear as ID before regression is appreciated. Many children with cerebral palsy (see Chapter 616.1 ) or ASD (Chapter 54 ) also have ID. Differentiation of isolated cerebral palsy from ID relies on motor skills being more affected than cognitive skills and on the presence of pathologic reflexes and tone changes. In autism spectrum disorders, language and social adaptive skills are more affected than nonverbal reasoning skills, whereas in ID, there are usually more equivalent deficits in social, fine motor, adaptive, and cognitive skills.

Diagnostic Psychologic Testing

The formal diagnosis of ID requires the administration of individual tests of intelligence and adaptive functioning.

The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III), the most commonly used infant intelligence test, provides an assessment of cognitive, language, motor, behavior, social-emotional, and general adaptive abilities between 1 mo and 42 mo of age. Mental Developmental Index (MDI) and Psychomotor Development Index (PDI, a measure of motor competence) scores are derived from the results. The BSID-III permits the differentiation of infants with severe ID from typically developing infants, but it is less helpful in distinguishing between a typical child and one with mild ID.

The most commonly used psychologic tests for children older than 3 yr are the Wechsler Scales. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV) is used for children with mental ages of 2.5-7.6 yr. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fifth Edition (WISC-V) is used for children who function above a 6 yr mental age. Both scales contain numerous subtests in the areas of verbal and performance skills. Although children with ID usually score below average on all subscale scores, they occasionally score in the average range in one or more performance areas.

Several normed scales are used in practice to evaluate adaptive functioning. For example, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS-3) uses semistructured interviews with parents and caregivers/teachers to assess adaptive behavior in 4 domains: communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills. Other tests of adaptive behavior include the Woodcock-Johnson Scales of Independent Behavior–Revised, the AAIDD Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale (DABS), and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS-3). There is usually (but not always) a good correlation between scores on the intelligence and adaptive scales. However, it is important to recognize that adaptive behavior can by influenced by environmentally based opportunities as well as family or cultural expectations. Basic practical adaptive skills (feeding, dressing, hygiene) are more responsive to remedial efforts than is the IQ score. Adaptive abilities are also more variable over time, which may be related to the underlying condition and environmental expectations.

Complications

Children with ID have higher rates of vision, hearing, neurologic, orthopedic, and behavioral or emotional disorders than typically developing children. These other problems are often detected later in children with ID. If untreated, the associated impairments can adversely affect the individual's outcome more than the ID itself.

The more severe the ID, the greater are the number and severity of associated impairments. Knowing the cause of the ID can help predict which associated impairments are most likely to occur. Fragile X syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome (see Chapter 126.3 ) are associated with a high rate of behavioral disorders; Down syndrome has many medical complications (hypothyroidism, obstructive sleep apnea, congenital heart disease, atlantoaxial subluxation). Associated impairments can require ongoing physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, behavioral therapy, adaptive and mobility equipment, glasses, hearing aids, and medication. Failure to identify and treat these impairments adequately can hinder successful habilitation and result in difficulties in the school, home, and neighborhood environment.

Prevention

Examples of primary programs to prevent ID include the following:

- ◆ Increasing the public's awareness of the adverse effects of alcohol and other drugs of abuse on the fetus (the most common preventable cause of ID in the Western world is fetal alcohol exposure).

- ◆ Encouraging safe sexual practices, preventing teen pregnancy, and promoting early prenatal care with a focus on preventive programs to limit transmission of diseases that may cause congenital infection (syphilis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, HIV).

- ◆ Preventing traumatic injury by encouraging the use of guards, railings, and window locks to prevent falls and other avoidable injuries in the home; using appropriate seat restraints when driving; wearing a safety helmet when biking or skateboarding; limiting exposure to firearms.

- ◆ Preventing poisonings by teaching parents about locking up medications and potential poisons.

- ◆ Implementing immunization programs to reduce the risk of ID caused by encephalitis, meningitis, and congenital infection.

Presymptomatic detection of certain disorders can result in treatment that prevents adverse consequences. State newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry (now including >50 rare genetic disorders in most states), newborn hearing screening, and preschool lead poisoning prevention programs are examples. Additionally, screening for comorbid conditions can help to limit the extent of disability and maximize level of functioning in certain populations. Annual thyroid, vision, and hearing screening in a child with Down syndrome is an example of presymptomatic testing in a disorder associated with ID.

Treatment

Although the core symptoms of ID itself are generally not treatable, many associated impairments are amenable to intervention and therefore benefit from early identification. Most children with an ID do not have a behavioral or emotional disorder as an associated impairment, but challenging behaviors (aggression, self-injury, oppositional defiant behavior) and mental illness (mood and anxiety disorders) occur with greater frequency in this population than among children with typical intelligence. These behavioral and emotional disorders are the primary cause for out-of-home placements, increased family stress, reduced employment prospects, and decreased opportunities for social integration. Some behavioral and emotional disorders are difficult to diagnose in children with more severe ID because of the child's limited abilities to understand, communicate, interpret, or generalize. Other disorders are masked by the ID. The detection of ADHD (see Chapter 49 ) in the presence of moderate to severe ID may be difficult, as may be discerning a thought disorder (psychosis) in someone with autism and ID.

Although mental illness is generally of biologic origin and responds to medication, behavioral disorders can result from a mismatch between the child's abilities and the demands of the situation, organic problems, and family difficulties. These behaviors may represent attempts by the child to communicate, gain attention, or avoid frustration. In assessing the challenging behavior, one must also consider whether it is inappropriate for the child's mental age, rather than the chronological age. When intervention is needed, an environmental change, such as a more appropriate classroom setting, may improve certain behavior problems. Behavior management techniques are useful; psychopharmacologic agents may be appropriate in certain situations.

No medication has been found that improves the core symptoms of ID. However, several agents are being tested in specific disorders with known biologic mechanisms (e.g., mGluR5 inhibitors in fragile X syndrome, mTOR inhibitors in tuberous sclerosis), with the hope for future pharmacologic options that could alter the natural course of cognitive impairment seen in patients with these disorders. Currently, medication is most useful in the treatment of associated behavioral and psychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology is generally directed at specific symptom complexes, including ADHD (stimulant medication), self-injurious behavior and aggression (antipsychotics), and anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Even if a medication proves successful, its use should be reevaluated at least yearly to assess the need for continued treatment.

Supportive Care and Management

Each child with ID needs a medical home with a pediatrician who is readily accessible to the family to answer questions, help coordinate care, and discuss concerns. Pediatricians can have effects on patients and their families that are still felt decades later. The role of the pediatrician includes involvement in prevention efforts, early diagnosis, identification of associated deficits, referral for appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic services, interdisciplinary management, provision of primary care, and advocacy for the child and family. The management strategies for children with an ID should be multimodal, with efforts directed at all aspects of the child's life: health, education, social and recreational activities, behavior problems, and associated impairments. Support for parents and siblings should also be provided.

Primary Care

For children with an ID, primary care has the following important components:

- ◆ Provision of the same primary care received by all other children of similar chronological age.

- ◆ Anticipatory guidance relevant to the child's level of function: feeding, toileting, school, accident prevention, sexuality education.

- ◆ Assessment of issues that are relevant to that child's disorder, such as dental examination in children who exhibit bruxism, thyroid function in children with Down syndrome, and cardiac function in Williams syndrome (see Chapter 454.5 ).

The AAP has published a series of guidelines for children with specific genetic disorders associated with ID (Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Williams syndrome). Goals should be considered and programs adjusted as needed during the primary care visit. Decisions should also be made about what additional information is required for future planning or to explain why the child is not meeting expectations. Other evaluations, such as formal psychologic or educational testing, may need to be scheduled.

Interdisciplinary Management

The pediatrician has the responsibility for consulting with other disciplines to make the diagnosis of ID and coordinate treatment services. Consultant services may include psychology, speech-language pathology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, audiology, nutrition, nursing, and social work, as well as medical specialties such as neurodevelopmental disabilities, neurology, genetics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, developmental-behavioral pediatricians, and surgical specialties. Contact with early intervention and school personnel is equally important to help prepare and assess the adequacy of the child's individual family service plan or individual educational plan. The family should be an integral part of the planning and direction of this process. Care should be family centered and culturally sensitive; for older children, their participation in planning and decision-making should be promoted to whatever extent possible.

Periodic Reevaluation

The child's abilities and the family's needs change over time. As the child grows, more information must be provided to the child and family, goals must be reassessed, and programming needs should be adjusted. A periodic review should include information about the child's health status as well as the child's functioning at home, at school, and in other community settings. Other information, such as formal psychologic or educational testing, may be helpful. Reevaluation should be undertaken at routine intervals (every 6-12 mo during early childhood), at any time the child is not meeting expectations, or when the child is moving from one service delivery system to another. This is especially true during the transition to adulthood, beginning at age 16, as mandated by the IDEA Amendments of 2004, and lasting through age 21, when care should be transitioned to adult-based systems and providers.

Federal and Education Services

Education is the single most important discipline involved in the treatment of children with an ID. The educational program must be relevant to the child's needs and address the child's individual strengths and weaknesses. The child's developmental level, requirements for support, and goals for independence provide a basis for establishing an individualized education program (IEP) for school-age children, as mandated by federal legislation.

Beyond education services, families of children with ID are often in great need of federal or state-provided social services. All states offer developmental disabilities programs that provide home and community-based services to eligible children and adults, potentially including in-home supports, care coordination services, residential living arrangements, and additional therapeutic options. A variety of Medicaid waiver programs are also offered for children with disabilities within each state. Children with ID who live in low socioeconomic status households should qualify to receive supplemental security income (SSI). Of note, in 2012, an estimated >40% of children with ID did not receive SSI benefits for which they would have been eligible, indicating an untapped potential resource for many families.

Leisure and Recreational Activities

The child's social and recreational needs should be addressed. Although young children with ID are generally included in play activities with children who have typical development, adolescents with ID often do not have opportunities for appropriate social interactions. Community participation among adults with ID is much lower than that of the typical population, stressing the importance of promoting involvement in social activities such as dances, trips, dating, extracurricular sports, and other social-recreational events at an early age. Participation in sports should be encouraged (even if the child is not competitive) because it offers many benefits, including weight management, development of physical coordination, maintenance of cardiovascular fitness, and improvement of self-image.

Family Counseling

Many families adapt well to having a child with ID, but some have emotional or social difficulties. The risks of parental depression and child abuse and neglect are higher in this group of children than in the general population. The factors associated with good family coping and parenting skills include stability of the marriage, good parental self-esteem, limited number of siblings, higher socioeconomic status, lower degree of disability or associated impairments (especially behavioral), parents' appropriate expectations and acceptance of the diagnosis, supportive extended family members, and availability of community programs and respite care services. In families in whom the emotional burden of having a child with ID is great, family counseling, parent support groups, respite care, and home health services should be an integral part of the treatment plan.

Transition to Adulthood

Transition to adulthood in adolescents with intellectual disabilities can present a stressful and chaotic time for both the individual and the family, just as it does among young adults of typical intelligence. A successful transition strongly correlates to later improved quality of life but requires significant advanced planning. In moving from child to adult care, families tend to find that policies, systems, and services are more fragmented, less readily available, and more difficult to navigate. Several domains of transition must be addressed, such as education and employment, health and living, finances and independence, and social and community life. Specific issues to manage include transitioning to an adult healthcare provider, determining the need for decision-making assistance (e.g., guardianship, medical power of attorney), securing government benefits after aging out of youth-based programs (e.g., SSI, medical assistance), agreeing on the optimal housing situation, applying for state disability assistance programs, and addressing caretaker estate planning as it applies to the individual with ID (e.g., special needs trusts).

Following graduation from high school, options for continued education or entry into the workforce should be thoroughly considered, with the greater goal of ultimate community-based employment. Although employment is a critical element of life adaptation for persons with ID, only 15% are estimated to have jobs, with significant gaps in pay and compensation compared to workers without disability. Early planning and expansion of opportunities can help to reduce barriers to employment. Post–secondary education possibilities might involve community college or vocational training. Employment selection should be “customized” to the individual's interests and abilities. Options may include participation in competitive employment, supported employment, high school–to–work transition programs, job-coaching programs, and consumer-directed voucher programs.

Prognosis

In children with severe ID, the prognosis is often evident by early childhood. Mild ID might not always be a lifelong disorder. Children might meet criteria for GDD at an early age, but later the disability can evolve into a more specific developmental disorder (communication disorder, autism, specific learning disability, or borderline normal intelligence). Others with a diagnosis of mild ID during their school years may develop sufficient adaptive behavior skills that they no longer fit the diagnosis as adolescents or young adults, or the effects of maturation and plasticity may result in children moving from one diagnostic category to another (from moderate to mild ID). Conversely, some children who have a diagnosis of a specific learning disability or communication disorder might not maintain their rate of cognitive growth and may fall into the range of ID over time.

The apparent higher prevalence of ID in low- and middle-income countries is of concern given the limitations in available resources. Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) is an effort promoted by WHO over the past 4 decades as a means of making use of existing community resources for persons with disabilities in low-income countries with the goal of increasing inclusion and participation within the community. CBR is now being implemented in >90 countries, although the efficacy of such programs has not been established.

The long-term outcome of persons with ID depends on the underlying cause, degree of cognitive and adaptive deficits, presence of associated medical and developmental impairments, capabilities of the families, and school and community supports, services, and training provided to the child and family (Table 53.7 ). As adults, many persons with mild ID are capable of gaining economic and social independence with functional literacy, but they may need periodic supervision (especially when under social or economic stress). Most live successfully in the community, either independently or in supervised settings.

Table 53.7

Data from World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Geneva, 2011, WHO.

For persons with moderate ID, the goals of education are to enhance adaptive abilities and “survival” academic and vocational skills so they are better able to live and function in the adult world (Table 53.7 ). The concept of supported employment has been very beneficial to these individuals; the person is trained by a coach to do a specific job in the setting where the person is to work, bypassing the need for a “sheltered workshop” experience and resulting in successful work adaptation in the community. These persons generally live at home or in a supervised setting in the community.

As adults, people with severe to profound ID usually require extensive to pervasive supports (Table 53.7 ). These individuals may have associated impairments, such as cerebral palsy, behavioral disorders, epilepsy, or sensory impairments, that further limit their adaptive functioning. They can perform simple tasks in supervised settings. Most people with this level of ID can live in the community with appropriate supports.

The life expectancy of people with mild ID is similar to the general population, with a mean age at death in the early 70s. However, persons with severe and profound ID have a decreased life expectancy at all ages, presumably from associated serious neurologic or medical disorders, with a mean age at death in the mid-50s. Given that persons with ID are living longer and have high rates of comorbid health conditions in adulthood (e.g., obesity, hypertension, diabetes), ID is now one of the costliest ICD-10 diagnoses, with an average lifetime cost of 1-2 million dollars per person. Thus the priorities for pediatricians are to improve healthcare delivery systems during childhood, facilitate the transition of care to adult providers, and ensure high-quality, integrated community-based services for all persons with ID.

Intellectual Disability With Regression

Bruce K. Shapiro, Meghan E. O'Neill

The patients discussed in Chapter 53 with intellectual disability (ID) usually have a static and nonprogressive disease course. They may acquire new developmental milestones, although at a slower rate than unaffected children, or they may remain fixed at a particular developmental stage. Regression of milestones in these children may be caused by increasing spasticity or contractures, new-onset seizures or a movement disorder, or the progression of hydrocephalus.

Nonetheless, regression or loss of milestones should suggest a progressive encephalopathy caused by an inborn error of metabolism, including disorders of energy metabolism and storage disorders, or a neurodegenerative disorder, including disorders of the whole brain (diffuse encephalopathies), white matter (leukodystrophies), cerebral cortex, and basal ganglia as well as spinocerebellar disorders (Table 53.8 ) (see Chapters 616 and 617 ).