Cytogenetics

Carlos A. Bacino, Brendan Lee

Clinical cytogenetics is the study of chromosomes: their structure, function, inheritance, and abnormalities. Chromosome abnormalities are very common and occur in approximately 1–2% of live births, 5% of stillbirths, and 50% of early fetal losses in the 1st trimester of pregnancy (Table 98.1 ). Chromosome abnormalities are more common among individuals with intellectual disability and play a significant role in the development of some neoplasias.

Table 98.1

Incidence of Chromosomal Abnormalities in Newborn Surveys

| TYPE OF ABNORMALITY | NUMBER | APPROXIMATE INCIDENCE |

|---|---|---|

| SEX CHROMOSOME ANEUPLOIDY | ||

| Males (43,612 newborns) | ||

| 47,XXY | 45 | 1/1,000* |

| 47,XYY | 45 | 1/1,000 |

| Other X or Y aneuploidy | 32 | 1/1,350 |

| Total | 122 | 1/360 male births |

| Females (24,547 newborns) | ||

| 45,X | 6 | 1/4,000 |

| 47,XXX | 27 | 1/900 |

| Other X aneuploidy | 9 | 1/2,700 |

| Total | 42 | 1/580 female births |

| AUTOSOMAL ANEUPLOIDY (68,159 NEWBORNS) | ||

| Trisomy 21 | 82 | 1/830 |

| Trisomy 18 | 9 | 1/7,500 |

| Trisomy 13 | 3 | 1/22,700 |

| Other aneuploidy | 2 | 1/34,000 |

| Total | 96 | 1/700 live births |

| STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITIES (68,159 NEWBORNS) | ||

| Balanced Rearrangements | ||

| Robertsonian | 62 | 1/1,100 |

| Other | 77 | 1/885 |

| Unbalanced Rearrangements | ||

| Robertsonian | 5 | 1/13,600 |

| Other | 38 | 1/1,800 |

| Total | 182 | 1/375 live births |

| All chromosome abnormalities | 442 | 1/154 live births |

* Recent studies show the prevalence is currently 1:580.

Data from Hsu LYF: Prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities through amniocentesis. In Milunsky A, editor: Genetic disorders and the fetus , ed 4, Baltimore, 1998, Johns Hopkins University Press, pp 179–248.

Chromosome analyses are indicated in persons presenting with multiple congenital anomalies, dysmorphic features, and/or intellectual disability. The specific indications for studies include advanced maternal age (>35 yr), multiple abnormalities on fetal ultrasound (prenatal testing), multiple congenital anomalies, unexplained growth restriction in the fetus, postnatal problems in growth and development, ambiguous genitalia, unexplained intellectual disability with or without associated anatomic abnormalities, primary amenorrhea or infertility, recurrent miscarriages (≥3) or prior history of stillbirths and neonatal deaths, a first-degree relative with a known or suspected structural chromosome abnormality, clinical findings consistent with a known anomaly, some malignancies, and chromosome breakage syndromes (e.g., Bloom syndrome, Fanconi anemia).

Methods of Chromosome Analysis

Carlos A. Bacino, Brendan Lee

Cytogenetic studies are usually performed on peripheral blood lymphocytes, although cultured fibroblasts obtained from a skin biopsy may also be used. Prenatal (fetal) chromosome studies are performed with cells obtained from the amniotic fluid (amniocytes), chorionic villus tissue, and fetal blood or, in the case of preimplantation diagnosis, by analysis of a blastomere (cleavage stage) biopsy, polar body biopsy, or blastocyst biopsy. Cytogenetic studies of bone marrow have an important role in tumor surveillance, particularly among patients with leukemia. These are useful to determine induction of remission and success of therapy or in some cases the occurrence of relapses.

Chromosome anomalies include abnormalities of number and structure and are the result of errors during cell division. There are 2 types of cell division: mitosis, which occurs in most somatic cells, and meiosis, which is limited to the germ cells. In mitosis, 2 genetically identical daughter cells are produced from a single parent cell. DNA duplication has already occurred during interphase in the S phase of the cell cycle (DNA synthesis). Therefore, at the beginning of mitosis the chromosomes consist of 2 double DNA strands joined together at the centromere, known as sister chromatids. Mitosis can be divided into 4 stages: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Prophase is characterized by condensation of the DNA. Also during prophase, the nuclear membrane and the nucleolus disappear and the mitotic spindle forms. In metaphase the chromosomes are maximally compacted and are clearly visible as distinct structures. The chromosomes align at the center of the cell, and spindle fibers connect to the centromere of each chromosome and extend to centrioles at the 2 poles of the mitotic figure. In anaphase the chromosomes divide along their longitudinal axes to form 2 daughter chromatids, which then migrate to opposite poles of the cell. Telophase is characterized by formation of 2 new nuclear membranes and nucleoli, duplication of the centrioles, and cytoplasmic cleavage to form the 2 daughter cells.

Meiosis begins in the female oocyte during fetal life and is completed years to decades later. In males it begins in a particular spermatogonial cell sometime between adolescence and adult life and is completed in a few days. Meiosis is preceded by DNA replication so that at the outset, each of the 46 chromosomes consists of 2 chromatids. In meiosis, a diploid cell (2n = 46 chromosomes) divides to form 4 haploid cells (n = 23 chromosomes). Meiosis consists of 2 major rounds of cell division. In meiosis I , each of the homologous chromosomes pair precisely so that genetic recombination , involving exchange between 2 DNA strands (crossing over ), can occur. This results in reshuffling of the genetic information for the recombined chromosomes and allows further genetic diversity. Each daughter cell then receives 1 of each of the 23 homologous chromosomes. In oogenesis, one of the daughter cells receives most of the cytoplasm and becomes the egg, whereas the other smaller cell becomes the first polar body. Meiosis II is similar to a mitotic division but without a preceding round of DNA duplication (replication). Each of the 23 chromosomes divides longitudinally, and the homologous chromatids migrate to opposite poles of the cell. This produces 4 spermatogonia in males, or an egg cell and a 2nd polar body in females, each with a haploid (n = 23) set of chromosomes. Consequently, meiosis fulfills 2 crucial roles: It reduces the chromosome number from diploid (46) to haploid (23) so that on fertilization a diploid number is restored, and it allows genetic recombination.

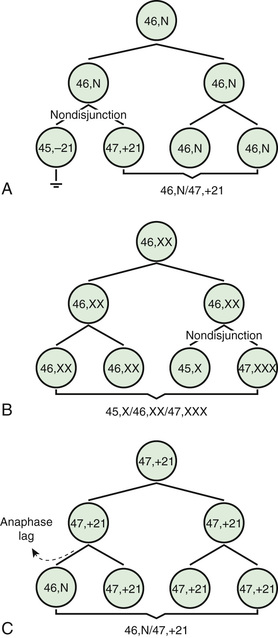

Two common errors of cell division may occur during meiosis or mitosis, and either can result in an abnormal number of chromosomes. The 1st error is nondisjunction , in which 2 chromosomes fail to separate during meiosis and thus migrate together into one of the new cells, producing 1 cell with 2 copies of the chromosome and another with no copy. The 2nd error is anaphase lag , in which a chromatid or chromosome is lost during mitosis because it fails to move quickly enough during anaphase to become incorporated into 1 of the new daughter cells (Fig. 98.1 ).

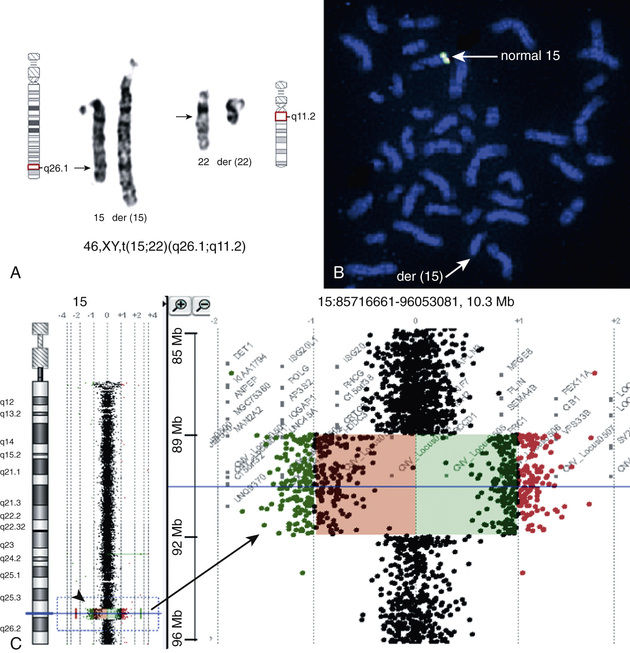

For chromosome analysis, cells are cultured (for varying periods depending on cell type), with or without stimulation, and then artificially arrested in mitosis during metaphase (or prometaphase), later subjected to a hypotonic solution to allow disruption of the nuclear cell membrane and proper dispersion of the chromosomes for analysis, fixed, banded, and finally stained. The most commonly used banding and staining method is the GTG banding (G-bands trypsin Giemsa), also known as G banding , which produces a unique combination of dark (G-positive) and light (G-negative) bands that permits recognition of all individual 23 chromosome pairs for analysis.

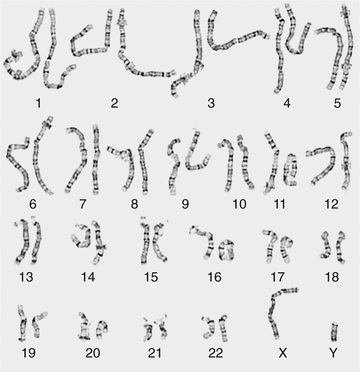

Metaphase chromosome spreads are first evaluated microscopically, and then their images are photographed or captured by a video camera and stored on a computer for later analysis. Humans have 46 chromosomes or 23 pairs, which are classified as autosomes for chromosomes 1-22, and the sex chromosomes , often referred as sex complement : XX for females and XY for males. The homologous chromosomes from a metaphase spread can then be paired and arranged systematically to assemble a karyotype according to well-defined standard conventions such as those established by International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN), with chromosome 1 being the largest and 22 the smallest. According to nomenclature, the description of the karyotype includes the total number of chromosomes followed by the sex chromosome constitution. A normal karyotype is 46,XX for females and 46,XY for males (Fig. 98.2 ). Abnormalities are noted after the sex chromosome complement.

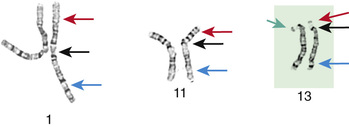

Although the internationally accepted system for human chromosome classification relies largely on the length and banding pattern of each chromosome, the position of the centromere relative to the ends of the chromosome also is a useful distinguishing feature (Fig. 98.3 ). The centromere divides the chromosome in 2, with the short arm designated the p arm and the long arm designated the q arm . A plus or minus sign before the number of a chromosome indicates that there is an extra or missing chromosome, respectively. Table 98.2 lists some of the abbreviations used for the descriptions of chromosomes and their abnormalities. A metaphase chromosome spread usually shows 450-550 bands. Prophase and prometaphase chromosomes are longer, are less condensed, and often show 550-850 bands. High-resolution analysis may detect small chromosome abnormalities although has been mostly replaced by chromosome microarray studies (array CGH or aCGH).

Table 98.2

Some Abbreviations Used for Description of Chromosomes and Their Abnormalities

| ABBREV | MEANING | EXAMPLE | CONDITION |

|---|---|---|---|

| XX | Female | 46,XX | Normal female karyotype |

| XY | Male | 46,XY | Normal male karyotype |

| [##] | Number [#] of cells | 46,XY[12]/47,XXY[10] | Number of cells in each clone, typically inside brackets |

| Mosaicism in Klinefelter syndrome with 12 normal cells and 10 cells with an extra X chromosome | |||

| cen | Centromere | ||

| del | Deletion | 46,XY,del(5p) | Male with deletion of chromosome 5 short arm |

| der | Derivative | 46,XX,der(2),t(2p12;7q13) | Female with a structurally rearranged chromosome 2 that resulted from a translocation between chromosomes 2 (short arm) and 7 (long arm) |

| dup | Duplication | 46,XY,dup(15)(q11-q13) | Male with interstitial duplication in the long arm of chromosome 15 in the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome region |

| ins | Insertion | 46,XY,ins(3)(p13q21q26) | Male with an insertion within chromosome 3 |

| A piece between q21q26 has reinserted on p13 | |||

| inv | Inversion | 46,XY,inv(2)(p21q31) | Male with pericentric inversion of chromosome 2 with breakpoints at bands p21 and q31 |

| ish | Metaphase FISH | 46,XX.ish del(7)(q11.23q11.23) | Female with deletion in the Williams syndrome region detected by in situ hybridization |

| nuc ish | Interphase FISH | nuc ish(DXZ1 × 3) | Interphase in situ hybridization showing 3 signals for the X chromosome centromeric region |

| mar | Marker | 47,XY,+mar | Male with extra, unidentified chromosome material |

| mos | Mosaic | mos 45,X[14]/46,XX[16] | Turner syndrome mosaicism (analysis of 30 cells showed that 14 cells were 45,X and 16 cells were 46,XX) |

| p | Short arm | 46,XY,del(5)(p12) | Male with a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5, band p12 (short nomenclature) |

| q | Long arm | 46,XY,del(5)(q14) | Male with a deletion on the long arm of chromosome 5, band 14 |

| r | Ring chromosome | 46,X,r(X)(p21q27) | Female with 1 normal X chromosome and a ring X chromosome |

| t | Translocation | t(2;8)(q33;q24.1) | Interchange of material between chromosomes 2 and 8 with breakpoints at bands 2q33 and 8q24.1 |

| ter | Terminal | 46,XY,del(5)(p12-pter) | Male with a deletion of chromosome 5 between p12 and the end of the short arm (long nomenclature) |

| / | Slash | 45,X/46,XY |

Separate lines or clones Mosaicism for monosomy X and a male cell line |

| + | Gain of | 47,XX,+21 | Female with trisomy 21 |

| − | Loss of | 45,XY,−21 | Male with monosomy 21 |

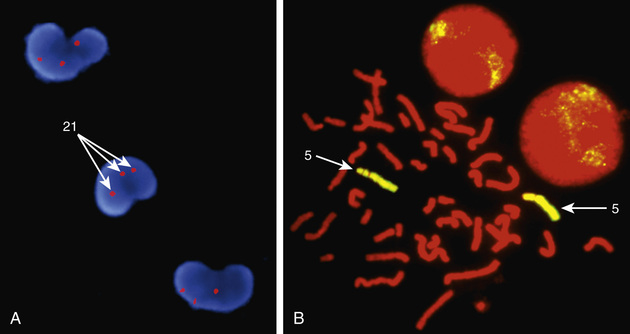

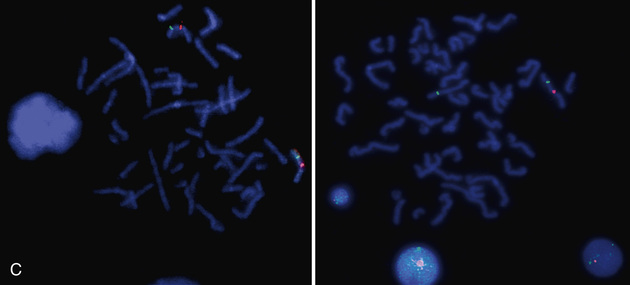

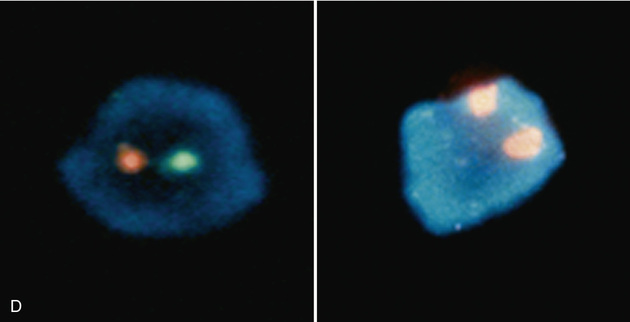

Molecular techniques (e.g., FISH, CMA, aCGH) have filled a significant void for the diagnosing cryptic chromosomal abnormalities. These techniques identify subtle abnormalities that are often below the resolution of standard cytogenetic studies. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is used to identify the presence, absence, or rearrangement of specific DNA segments and is performed with gene- or region-specific DNA probes. Several FISH probes are used in the clinical setting: unique sequence or single-copy probes, repetitive-sequence probes (alpha satellites in the pericentromeric regions), and multiple-copy probes (chromosome specific or painting) (Fig. 98.4A and B ). FISH involves using a unique, known DNA sequence or probe labeled with a fluorescent dye that is complementary to the studied region of disease interest. The labeled probe is exposed to the DNA on a microscope slide, typically metaphase or interphase chromosomal DNA. When the probe pairs with its complementary DNA sequence, it can then be visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 98.5 ). In metaphase chromosome spreads, the exact chromosomal location of each probe copy can be documented, and often the number of copies (deletions, duplications) of the DNA sequence as well. When the interrogated segments (as in genomic duplications) are close together, only interphase cells can accurately determine the presence of 2 or more copies or signals since in metaphase cells, some duplications might falsely appear as a single signal.

Chromosome rearrangements <5 million bp (5 Mbp) cannot be detected by conventional cytogenetic techniques. FISH was initially used to detect deletions as small as 50-200 kb of DNA and facilitated the early clinical characterization of a number of microdeletion syndromes . Some FISH probes hybridize to repetitive sequences located in the pericentromeric regions. Pericentromeric probes are still widely used for the rapid identification of certain trisomies in interphase cells of blood smears, or even in the rapid analysis of prenatal samples from cells obtained through amniocentesis. Such probes are available for chromosomes 13, 18, and 21 and for the sex pair X and Y (see Fig. 98.4C and D ). With regard to the detection of genomic disorders, FISH is no longer the first line of testing, and its role has also mostly changed to the confirmation of microarray findings. In summary, FISH is reserved for (1) confirmation studies of abnormalities detected by CMA, (2) rapid prenatal screening on interphase amniotic fluid cells, and (3) interphase blood smear for sex assignment of newborns who present with ambiguous genitalia.

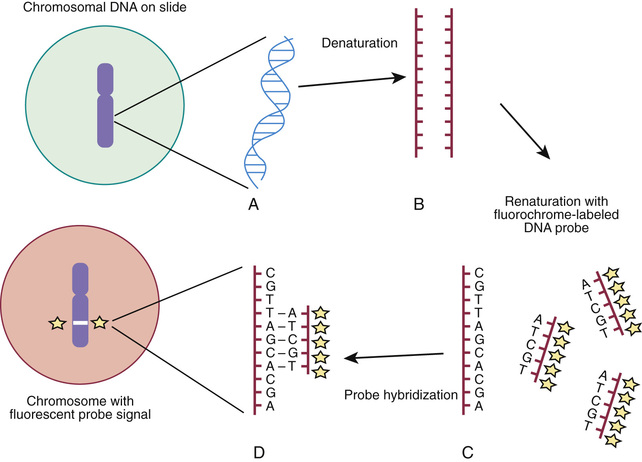

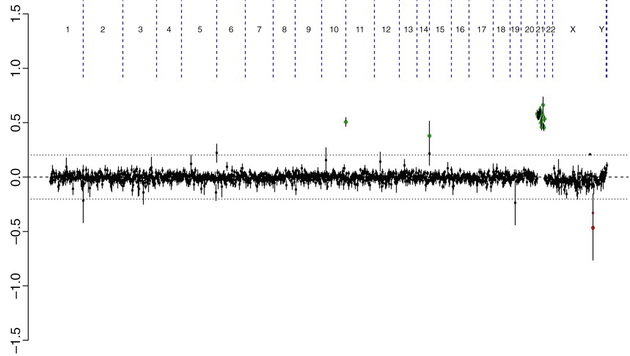

Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and chromosomal microarray (CMA) are molecular-based techniques that involve differentially labeling the patient's DNA with a fluorescent dye (green fluorophore) and a normal reference DNA with a red fluorophore (Fig. 98.6 ). Oligonucleotides (short DNA segments) encompassing the entire genome are spotted onto a slide or microarray grid. Equal amounts of the 2-label DNA samples are mixed, and the green:red fluorescence ratio is measured along each tested area. Regions of amplification of the patient's DNA display an excess of green fluorescence, and regions of loss show excess red fluorescence. If the patient's and the control DNA are equally represented, the green:red ratio is 1 : 1, and the tested regions appear yellow (see Chapter 96 , Fig. 96.5 ). The detection is currently possible at the single-exon resolution level, depending on the arrays used. In the near future, copy number detections may further evolve to be detected by next generation sequencing in the context of whole genome sequencing.

The many advantages of aCGH include its ability to test all critical disease-causing regions in the genome at once, detect duplications and deletions not currently recognized as recurrent disease-causing regions probed by FISH, and detect single-gene and contiguous gene deletion syndromes. Also, aCGH does not always require cell culture to generate sufficient DNA, which may be important in the context of prenatal testing because of timing. Limitations of aCGH are that it does not detect balanced translocations or inversions and may not detect low levels of chromosomal mosaicism. Among different types of aCGH, some are more targeted than others. Targeted aCGH can be an efficient way to detect clinically known cryptic chromosomal aberrations, which are typically associated with known disease phenotypes. Whole genome arrays target the entire genome and allow better and denser coverage in evenly spaced genomic regions. Its disadvantage is that interpretation of deletions or duplications may be difficult if it involves areas not previously known to be involved in disease.

A frequently used array in the clinical setting is the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) . SNPs are polymorphic variations between 2 nucleotides, and when analyzed in massive parallel fashion, they can provide valuable clinical information. Several million SNPs normally occur in the human genome. SNP arrays can help with the detection of uniparental disomies (i.e., genetic information derived from only 1 parent), as well as consanguinity in the family. Many arrays currently used in clinical practice combine the use of oligonucleotides for the detection of copy number variations in conjunction with SNPs. There are many copy number variations causing deletion or duplication in the human genome. Thus, most detected genetic abnormalities, unless associated with well-known clinical phenotypes, require parental investigations because a detected copy number variation that is inherited could be benign or an incidental polymorphic variant. A de novo abnormality (i.e., one found only in the child and not the parents) is often more significant if it is associated with an abnormal phenotype found only in the child, and if it involves genes with important functions.

aCGH is a very valuable technology alone or when combined with FISH and conventional chromosome studies (Fig. 98.7 ).

Bibliography

Methods of Chromosome Analysis

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol . 2007;109:217–227.

Bejjani BA, Saleki R, Ballif BC, et al. Use of targeted array-based CGH for the clinical diagnosis of chromosomal imbalance: is less more? Am J Med Genet . 2005;134A:259–267.

Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA sequencing. Obstet Gynecol . 2012;119:890–901.

Dugoff L. Application of genomic technology in prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:2249–2251.

Li MM, Andersson HC. Clinical application of microarray-based molecular cytogenetics: an emerging new era of genomic medicine. J Pediatr . 2009;155:311–317.

Papenhausen P, Schwartz S, Risheg H, et al. UPD detection using homozygosity profiling with a SNP genotyping microarray. Am J Med Genet . 2011;155A:757–768.

Petherick A. Cell-free DNA screening for trisomy is rolled out in Israel. Lancet . 2013;382:846.

Saugier-Veber P, Girard-Lemaire F, Rudolf G, et al. Genetic compensation in a human genomic disorder. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:1211–1216.

Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:2175–2184.

Down Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of Chromosome Number

Brendan Lee

Aneuploidy and Polyploidy

Human cells contain a multiple of 23 chromosomes (n = 23). A haploid cell (n) has 23 chromosomes (typically in the ovum or sperm). If a cell's chromosomes are an exact multiple of 23 (46, 69, 92 in humans), those cells are referred to as euploid . Polyploid cells are euploid cells with more than the normal diploid number of 46 (2n) chromosomes: 3n, 4n. Polyploid conceptions are usually not viable, but the presence of mosaicism with a karyotypically normal cell line can allow survival. Mosaicism is an abnormality defined as the presence of 2 or more cell lines in a single individual. Polyploidy is a common abnormality seen in 1st-trimester pregnancy losses. Triploid cells are those with 3 haploid sets of chromosomes (3n) and are only viable in a mosaic form. Triploid infants can be liveborn but do not survive long. Triploidy is often the result of fertilization of an egg by 2 sperm (dispermy). Failure of 1 of the meiotic divisions, resulting in a diploid egg or sperm, can also result in triploidy. The phenotype of a triploid conception depends on the origin of the extra chromosome set. If the extra set is of paternal origin, it results in a partial hydatidiform mole (excessive placental growth) with poor embryonic development, but triploid conceptions that have an extra set of maternal chromosomes results in severe embryonic restriction with a small, fibrotic placenta (insufficient placental development) that is typically spontaneously aborted.

Abnormal cells that do not contain a multiple of haploid number of chromosomes are termed aneuploid cells. Aneuploidy is the most common and clinically significant type of human chromosome abnormality, occurring in at least 3–4% of all clinically recognized pregnancies. Monosomies occur when only 1, instead of the normal 2, of a given chromosome is present in an otherwise diploid cell. In humans, most autosomal monosomies appear to be lethal early in development, and survival is possible in mosaic forms or by means of chromosome rescue (restoration of the normal number by duplication of single monosomic chromosome). An exception to this rule is monosomy for the X chromosome (45,X), seen in Turner syndrome; the majority of 45,X conceptuses are believed to be lost early in pregnancy for as yet unexplained reasons.

The most common cause of aneuploidy is nondisjunction , the failure of chromosomes to disjoin normally during meiosis (see Fig. 98.1 ). Nondisjunction can occur during meiosis I or II or during mitosis, although maternal meiosis I is the most common nondisjunction in aneuploidies (e.g., Down syndrome, trisomy 18). After meiotic nondisjunction, the resulting gamete either lacks a chromosome or has 2 copies instead of 1 normal copy, resulting in a monosomic or trisomic zygote, respectively.

Trisomy is characterized by the presence of 3 chromosomes, instead of the normal 2, of any particular chromosome. Trisomy is the most common form of aneuploidy. Trisomy can occur in all cells or it may be mosaic. Most individuals with a trisomy exhibit a consistent and specific phenotype depending on the chromosome involved.

FISH is a technique that can be used for rapid diagnosis in the prenatal detection of common fetal aneuploidies, including chromosomes 13, 18, and 21, as well as sex chromosomes (see Fig. 98.4C and D ). Direct detection of fetal cell-free DNA from maternal plasma for fetal trisomy is a safe and highly effective screening test for fetal aneuploidy. The most common numerical abnormalities in liveborn children include trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome), and sex chromosomal aneuploidies: Turner syndrome (usually 45,X), Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), 47,XXX, and 47,XYY. By far the most common type of trisomy in liveborn infants is trisomy 21 (47,XX,+21 or 47,XY,+21) (see Table 98.1 ). Trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 are relatively less common and are associated with a characteristic set of congenital anomalies and severe intellectual disability (Table 98.3 ). The occurrence of trisomy 21 and other trisomies increases with advanced maternal age (≥35 yr). Because of this increased risk, women who are ≥35 yr old at delivery should be offered genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis (including serum screening, ultrasonography, and cell-free fetal DNA detection, amniocentesis, or chorionic villus sampling; see Chapter 115 ).

Table 98.3

Chromosomal Trisomies and Their Clinical Findings

| SYNDROME | INCIDENCE | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

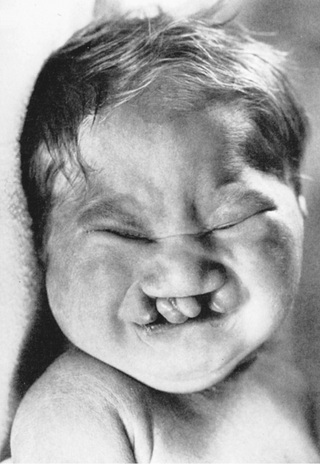

| Trisomy 13, Patau syndrome | 1/10,000 births | Cleft lip often midline; flexed fingers with postaxial polydactyly; ocular hypotelorism, bulbous nose; low-set, malformed ears; microcephaly; cerebral malformation, especially holoprosencephaly; microphthalmia, cardiac malformations; scalp defects; hypoplastic or absent ribs; visceral and genital anomalies |

| Early lethality in most cases, with a median survival of 12 days; ~80% die by 1 year; 10-year survival ~13%. Survivors have significant neurodevelopmental delay. | ||

| Trisomy 18, Edwards syndrome | 1/6,000 births | Low birthweight, closed fists with index finger overlapping the 3rd digit and the 5th digit overlapping the 4th, narrow hips with limited abduction, short sternum, rocker-bottom feet, microcephaly, prominent occiput, micrognathia, cardiac and renal malformations, intellectual disability |

| ~88% of children die in the 1st year; 10-year survival ~10%. Survivors have significant neurodevelopmental delay. | ||

| Trisomy 8, mosaicism | 1/20,000 births | Long face; high, prominent forehead; wide, upturned nose, thick, everted lower lip; microretrognathia; low-set ears; high-arched, sometimes cleft, palate; osteoarticular anomalies common (camptodactyly of 2nd-5th digits, small patella); deep plantar and palmar creases; moderate intellectual disability |

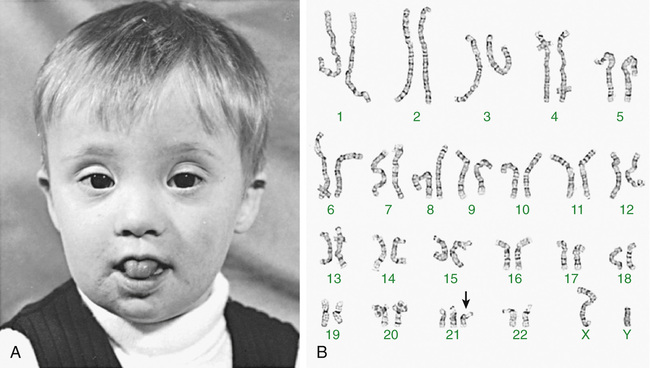

Down Syndrome

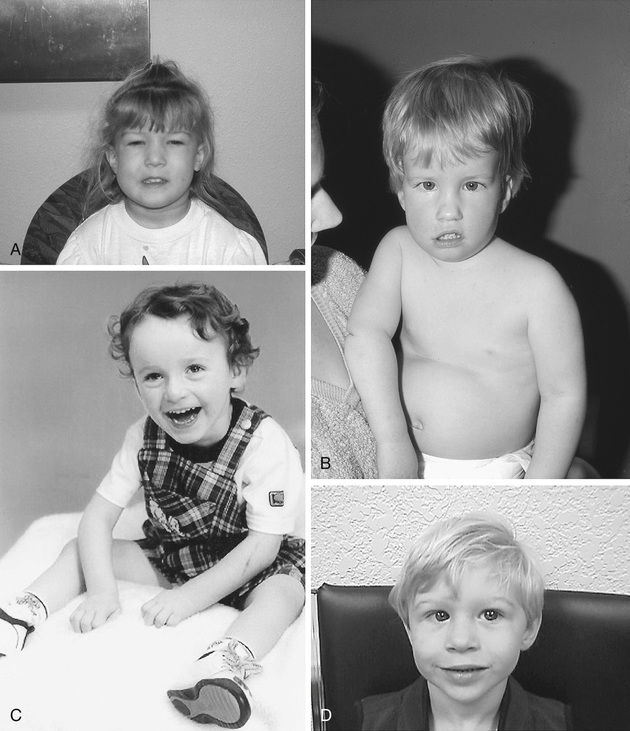

Trisomy 21 is the most common genetic etiology of moderate intellectual disability. The incidence of Down syndrome in live births is approximately 1 in 733; the incidence at conception is more than twice that rate; the difference is accounted for by early pregnancy losses. In addition to cognitive impairment, Down syndrome is associated with congenital anomalies and characteristic dysmorphic features (Figs. 98.8 and 98.9 and Table 98.4 ). Although there is variability in the clinical features, the constellation of phenotypic features is fairly consistent and permits clinical recognition of trisomy 21. Affected individuals are more prone to congenital heart defects (50%) such as atrioventricular septal defects, ventricular septal defects, isolated secundum atrial septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and tetralogy of Fallot. Pulmonary complications include recurrent respiratory infections, sleep-disordered breathing, laryngo- and tracheobronchochomalacia, tracheal bronchus, pulmonary hypertension, and asthma. Congenital and acquired gastrointestinal anomalies (celiac disease) and hypothyroidism are common (Table 98.5 ). Other abnormalities include megakaryoblastic leukemia, immune dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, seizures, alopecia, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and problems with hearing and vision. Alzheimer disease–like dementia is a known complication that occurs as early as the 4th decade and has an incidence 2-3 times higher than sporadic Alzheimer disease. Most males with Down syndrome are sterile, but some females have been able to reproduce, with a 50% chance of having trisomy 21 pregnancies. Two genes (DYRK1A, DSCR1 ) in the putative critical region of chromosome 21 may be targets for therapy.

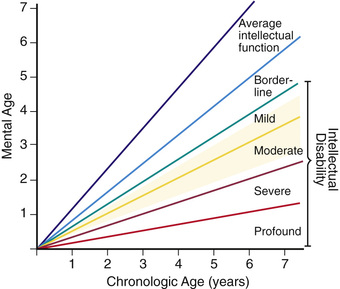

Developmental delay is universal (Tables 98.6 and 98.7 and Fig. 98.10 ). Cognitive impairment does not uniformly affect all areas of development. Social development is often relatively spared, but autism spectrum disorder can occur. Children with Down syndrome have considerable difficulty using expressive language. Understanding the individual developmental strengths and challenges is necessary to maximize the educational process. Persons with Down syndrome often benefit from programs aimed at cognitive training, stimulation, development, and education. Children with Down syndrome also benefit from anticipatory guidance, which establishes the protocol for screening, evaluation, and care for patients with genetic syndromes and chronic disorders (Table 98.8 ). Up to 15% of children with Down syndrome have misalignment of the 1st cervical vertebra (C1), which places them at risk for spinal cord injury with neck hyperextension or extreme flexion. Special Olympics recommends sports participation and training but requires x-ray examination (full extension and flexion views) of the neck before participation in sports that may result in hyperextension or radical flexion or pressure on the neck or upper spine. Such sports include diving starts in swimming, butterfly stroke, diving, pentathlon, high jump, equestrian sports, gymnastics, football, soccer, alpine skinning, and warm-up exercises placing stress on the head and neck. If atlantoaxial instability is diagnosed, Special Olympics will permit participation if the parents or guardians request so and only after obtaining written certification from a physician and acknowledgment of the risks by the parent or guardian.

Table 98.6

| Milestone | CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME | UNAFFECTED CHILDREN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (mo) | Range (mo) | Average (mo) | Range (mo) | |

| Smiling | 2 | 1.5-3 | 1 | 1.5-3 |

| Rolling over | 6 | 2-12 | 5 | 2-10 |

| Sitting | 9 | 6-18 | 7 | 5-9 |

| Crawling | 11 | 7-21 | 8 | 6-11 |

| Creeping | 13 | 8-25 | 10 | 7-13 |

| Standing | 10 | 10-32 | 11 | 8-16 |

| Walking | 20 | 12-45 | 13 | 8-18 |

| Talking, words | 14 | 9-30 | 10 | 6-14 |

| Talking, sentences | 24 | 18-46 | 21 | 14-32 |

From Levine MD, Carey WB, Crocker AC, editors: Developmental-behavioral pediatrics, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1992, Saunders.

Table 98.7

| Skill | DOWN SYNDROME CHILDREN | UNAFFECTED CHILDREN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (mo) | Range (mo) | Average (mo) | Range (mo) | |

| EATING | ||||

| Finger feeding | 12 | 8-28 | 8 | 6-16 |

| Using spoon/fork | 20 | 12-40 | 13 | 8-20 |

| TOILET TRAINING | ||||

| Bladder | 48 | 20-95 | 32 | 18-60 |

| Bowel | 42 | 28-90 | 29 | 16-48 |

| DRESSING | ||||

| Undressing | 40 | 29-72 | 32 | 22-42 |

| Putting clothes on | 58 | 38-98 | 47 | 34-58 |

From Levine MD, Carey WB, Crocker AC, editors: Developmental-behavioral pediatrics, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1992, Saunders.

Table 98.8

Health Supervision for Children With Down Syndrome

| CONDITION | TIME TO SCREEN | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital heart disease | Birth; by pediatric cardiologist | 50% risk of congenital heart disease; increased risk for pulmonary hypertension |

| Young adult for acquired valve disease | ||

| Strabismus, cataracts, nystagmus | Birth or by 6 mo; by pediatric ophthalmologist | Cataracts occur in 15%, refractive errors in 50% |

| Check vision annually | ||

| Hearing impairment or loss | Birth or by 3 mo with auditory brainstem response or otoacoustic emission testing; check hearing q6mo up to 3 yr if tympanic membrane is not visualized; annually thereafter | Risk for congenital hearing loss plus 50–70% risk of serous otitis media |

| Constipation | Birth | Increased risk for Hirschsprung disease |

| Celiac disease | At 2 yr or with symptoms | Screen with IgA and tissue transglutaminase antibodies |

| Hematologic disease | At birth and in adolescence or if symptoms develop | Increased risk for neonatal polycythemia (18%), leukemoid reaction, leukemia (<1%) |

| Hypothyroidism | Birth; repeat at 6-12 mo and annually | Congenital (1%) and acquired (5%) |

| Growth and development | At each visit | Discuss school placement options |

| Use Down syndrome growth curves | Proper diet to avoid obesity | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Start at ~1 yr and at each visit | Monitor for snoring, restless sleep |

| Atlantoaxial subluxation or instability (incidence 10–30%) | At each visit by history and physical exam | Special Olympics recommendations are to screen for high-risk sports, e.g., diving, swimming, contact sports |

| Radiographs at 3-5 yr or when planning to participate in contact sports | ||

| Radiographs indicated wherever neurologic symptoms are present even if transient (neck pain, torticollis, gait disturbances, weakness) | ||

| Many are asymptomatic | ||

| Gynecologic care | Adolescent girls | Menstruation and contraception issues |

| Recurrent infections | When present | Check IgG subclass and IgA levels |

| Psychiatric, behavioral disorders | At each visit | Depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia seem in 10–17% |

| Autism spectrum disorder in 5–10% | ||

| Early-onset Alzheimer disease |

IgA, Immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Data from Committee on Genetics: Health supervision for children with Down syndrome, Pediatrics 107:442–449, 2001; and Baum RA, Spader M, Nash PL, et al: Primary care of children and adolescents with Down syndrome: an update, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 38:235–268, 2008.

Compared with the general population, children with Down syndrome are at increased risk for behavior problems; psychiatric comorbidity is an estimated 18–38% in this population. Common behavioral difficulties that occur in children with Down syndrome include inattentiveness, stubbornness, and a need for routine and sameness. Aggression and self-injurious behavior are less common in this population than other children with similar degrees of intellectual disability from other etiologies. All these behaviors can respond to educational, behavioral, or pharmacologic interventions.

The life expectancy for children with Down syndrome is reduced and is approximately 50-55 yr. Little prospective information about the secondary medical problems of adults with Down syndrome is known. Retrospective studies have shown premature aging and an increased risk of Alzheimer disease in adults with Down syndrome. These studies have also shown unexpected negative (protective) associations between Down syndrome and comorbidities. Persons with Down syndrome have fewer-than-expected deaths caused by solid tumors and ischemic heart disease. This same study reported increased risk of adult deaths from congenital heart disease, seizures, and leukemia. In one large study, leukemias accounted for 60% of all cancers in people with Down syndrome and 97% of all cancers in children with Down syndrome. There was decreased risk of solid tumors in all age-groups with Down syndrome, including neuroblastomas and nephroblastomas in children and epithelial tumors in adults.

Most adults with Down syndrome are able to perform activities of daily living. However, most have difficulty with complex financial, legal, or medical decisions, and a guardian may be appointed.

The risk of having a child with trisomy 21 is highest in women who conceive after age 35 yr. Even though younger women have a lower risk, they represent half of all mothers with babies with Down syndrome because of their higher overall birth rate. All women should be offered screening for Down syndrome in their 2nd trimester by means of 4 maternal serum tests (free β-human chorionic gonadotropin [β-hCG], unconjugated estriol, inhibin, and α-fetoprotein). This is known as the quad screen; it can detect up to 80% of Down syndrome pregnancies vs 70% in the triple screen. Both tests have a 5% false-positive rate. There is a method of screening during the 1st trimester using fetal nuchal translucency (NT) thickness that can be done alone or in conjunction with maternal serum β-hCG and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A). In the 1st trimester, NT alone can detect ≤70% of Down syndrome pregnancies, but with β-hCG and PAPP-A, the detection rate increases to 87%. If both 1st- and 2nd-trimester screens are combined using NT and biochemical profiles (integrated screen), the detection rate increases to 95%. If only 1st-trimester quad screening is done, maternal serum α-fetoprotein (which is decreased in affected pregnancies) is recommended as a 2nd-trimester follow-up.

Detection of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma is also diagnostic and replacing conventional 1st- and 2nd-trimester screens. The noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21 by analyzing cell-free fetal DNA in maternal serum is an important advance in prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. Next-generation DNA sequencing has reduced the cost of this procedure, which has a high degree of accuracy (98% detection rate) and applicability. The prenatal screens are also useful for other trisomies, although the detection rates may be different from those given for Down syndrome. Current tests can detect microdeletions including 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Prader Willi syndrome deletion, cri du chat syndrome, Williams syndrome, and 1p36.3 deletion syndrome. Importantly, especially for microdeletions, cell-free noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) should be considered primarily for screening tests and follow-up invasive testing (e.g., amniocentesis) pursued for definitive diagnosis.

In approximately 95% of the cases of Down syndrome, there are 3 copies of chromosome 21. The origin of the supernumerary chromosome 21 is maternal in 97% of the cases as a result of errors in meiosis. The majority of these occur in maternal meiosis I (90%). Approximately 1% of persons with trisomy 21 are mosaics, with some cells having 46 chromosomes, and another 4% have a translocation that involves chromosome 21. The majority of translocations in Down syndrome are fusions at the centromere between chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22, known as robertsonian translocations. The translocations can be de novo or inherited. Very rarely is Down syndrome diagnosed in a patient with only a part of the long arm of chromosome 21 in triplicate (partial trisomy ). Isochromosomes and ring chromosomes are other rarer causes of trisomy 21. Down syndrome patients without a visible chromosome abnormality are the least common. It is not possible to distinguish the phenotypes of persons with full trisomy 21 and those with a translocation. Representative genes on chromosome 21 and their potential effects on development are noted in Table 98.9 . Patients who are mosaic tend to have a milder phenotype.

Table 98.9

Genes Localized to Chromosome 21 That May Affect Brain Development, Neuronal Loss, and Alzheimer-Type Neuropathology

| SYMBOL | NAME | POSSIBLE EFFECT IN DOWN SYNDROME | FUNCTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIM2 | Single-minded homolog 2 | Brain development | Required for synchronized cell division and establishment of proper cell lineage |

| DYRK1A | Dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1A | Brain development |

Expressed during neuroblast proliferation Believed important homolog in regulating cell-cycle kinetics during cell division |

| GART |

Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase Phosphoribosylglycinamide synthetase Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase |

Brain development | Expressed during prenatal development of the cerebellum |

| PCP4 | Purkinje cell protein 4 | Brain development | Function unknown but found exclusively in the brain and most abundantly in the cerebellum |

| DSCAM | Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule | Brain development and possible candidate gene for congenital heart disease | Expressed in all molecule regions of the brain and believed to have a role in axonal outgrowth during development of the nervous system |

| GRIK1 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic kainite1 | Neuronal loss | Function unknown, found in the cortex in fetal and early postnatal life and in adult primates, most concentrated in pyramidal cells in the cortex |

| APP | Amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (protease nexin-II, Alzheimer disease) | Alzheimer type neuropathy | Seems to be involved in plasticity, neurite outgrowth, and neuroprotection |

| S100B | S100 calcium binding protein β (neural) | Alzheimer type neuropathy | Stimulates glial formation |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, adult) | Accelerated aging? | Scavenges free superoxide molecules in the cell and might accelerate aging by producing hydrogen peroxide and oxygen |

Chromosome analysis is indicated in every person suspected of having Down syndrome. If a translocation is identified, parental chromosome studies must be performed to determine whether one of the parents is a translocation carrier, which carries a high recurrence risk for having another affected child. That parent might also have other family members at risk. Translocation (21;21) carriers have a 100% recurrence risk for a chromosomally abnormal child, and other robertsonian translocations, such as t(14;21), have a 5–7% recurrence risk when transmitted by females. Genomic dosage imbalance contributes through direct and indirect pathways to the Down syndrome phenotype and its phenotypic variation.

Tables 98.10 and 98.11 provide more information on other aneuploidies and partial autosomal aneuploidies (Figs. 98.11 to 98.14 ).

Table 98.10

Other Rare Aneuploidies and Partial Autosomal Aneuploidies

| DISORDER | KARYOTYPE | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 8 | 47,XX/XY,+8 | Growth and mental deficiency are variable. |

| The majority of patients are mosaics. | ||

| Deep palmar and plantar furrows are characteristic. | ||

| Joint contractures | ||

| Trisomy 9 | 47,XX/XY,+9 | The majority of patients are mosaics. |

| Clinical features include craniofacial (high forehead, microphthalmia, low-set malformed ears, bulbous nose) and skeletal (joint contractures) malformations and heart defects (60%). | ||

| Trisomy 16 | 47,XX/XY,+16 | The most commonly observed autosomal aneuploidy in spontaneous abortion; the recurrence risk is negligible. |

| Tetrasomy 12p | 46,XX[12]/46,XX, +i(12p)[8] (mosaicism for an isochromosome 12p) | Known as Pallister-Killian syndrome |

| Sparse anterior scalp hair (more so temporal region), eyebrows, and eyelashes; prominent forehead; chubby cheeks; long philtrum with thin upper lip and cupid-bow configuration; polydactyly; streaks of hyper- and hypopigmentation |

Table 98.11

Findings That May Be Present in Trisomy 13 and Trisomy 18

| TRISOMY 13 | TRISOMY 18 |

|---|---|

| HEAD AND FACE | |

|

Scalp defects (e.g., cutis aplasia) Microphthalmia, corneal abnormalities Cleft lip and palate in 60–80% of cases Microcephaly Microphthalmia Sloping forehead Holoprosencephaly (arrhinencephaly) Capillary hemangiomas Deafness |

Small and premature appearance Tight palpebral fissures Narrow nose and hypoplastic nasal alae Narrow bifrontal diameter Prominent occiput Micrognathia Cleft lip or palate Microcephaly |

| CHEST | |

|

Congenital heart disease (e.g., VSD, PDA, ASD) in 80% of cases Thin posterior ribs (missing ribs) |

Congenital heart disease (e.g., VSD, PDA, ASD) Short sternum, small nipples |

| EXTREMITIES | |

|

Overlapping of fingers and toes (clinodactyly) Polydactyly Hypoplastic nails, hyperconvex nails |

Limited hip abduction Clinodactyly and overlapping fingers; index over 3rd, 5th over 4th; closed fist Rocker-bottom feet Hypoplastic nails |

| GENERAL | |

|

Severe developmental delays and prenatal and postnatal growth restriction Renal abnormalities Survival (see Table 98.3 ) |

Severe developmental delays and prenatal and postnatal growth restriction Premature birth, polyhydramnios Inguinal or abdominal hernias Survival (see Table 98.3 ) |

ASD, Atrial septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

From Behrman RE, Kliegman RM: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, Saunders, p 142.

Bibliography

Down Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of Chromosome Number

Arnell H, Fischler B. Population-based study of incidence and clinical outcome of neonatal cholestasis in patients with Down syndrome. J Pediatr . 2012;161:899–902.

Baum RA, Nash PL, Foster JEA, et al. Primary care of children and adolescents with Down syndrome: an update. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care . 2008;38:235–268.

Bull MJ. Committee on Genetics: Clinical report–health supervision for children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics . 2011;128:393–406.

Carey JC. Perspectives on the care and management of infants with trisomy 18 and trisomy 13: striving for balance. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2012;24:672–678.

Carter M, McCaughey E, Annaz D, et al. Sleep problems in a Down syndrome population. Arch Dis Child . 2009;94:308–310.

Chiu RWK, Akolekar R, Zheng YWL, et al. Non-invasive prenatal assessment of trisomy 21 by multiplexed maternal plasma DNA sequencing: large scale validity study. BMJ . 2011;342:217.

Cicero S, Bindra R, Rembouskos G, et al. Integrated ultrasound and biochemical screening for trisomy 21 using fetal nuchal translucency, absent fetal nasal bone, free β-hCG and PAPP-A at 11 to 14 weeks. Prenat Diagn . 2003;23:306–310.

De la Torre R, de Sola S, Hernandez G, et al. Safety and efficacy of cognitive training plus epigallocatechin-3-gallate in young adults with Down's syndrome (TESDAD): a double-blind, randomizes, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol . 2016;15:801–810.

Dennis J, Archer N, Ellis J, et al. Recognising heart disease in children with Down syndrome. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed . 2010;98–104.

Dykens EM. Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in persons with Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev . 2007;13:272–278.

Ehrich M, Deciu C, Zwiefelhofer T, et al. Noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21 by sequencing of DNA in maternal blood: a study in a clinical setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2011;204:205.e1–205.e11.

Garrison MM, Jeffries H, Christakis DA. Risk of death for children with Down syndrome and sepsis. J Pediatr . 2005;147:748–752.

Gibson PA, Newton RW, Selby K, et al. Longitudinal study of thyroid function in Down's syndrome in the first two decades. Arch Dis Child . 2005;90:574–578.

Hanney M, Prasher V, Williams N, et al. Memantine for dementia in adults older than 40 years with Down's syndrome (MEADOWS): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet . 2012;379:528–536.

Irving C, Basu A, Richmond S, et al. Twenty-year trends in prevalence and survival of Down syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet . 2008;16:1336–1340.

Janvier A, Farlow B, Wilfond BS. The experience of families with children with trisomy 13 and 18 in social networks. Pediatrics . 2012;130:293–298.

Juj H, Emery H. The arthropathy of Down syndrome: an undiagnosed and under-recognized condition. J Pediatr . 2009;154:234–238.

Kaneko Y, Kobayashi J, Achiwa I, et al. Cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18. Pediatr Cardiol . 2009;30:729–734.

Kennedy JP Jr. Foundation for the Benefit of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities: Special Olympics coaching guides . www.specialolympics.org ; 2004.

Kumada T, Miyajima T, Fujii T. Whorled eyebrows: a common facial feature of children with trisomy 18. J Pediatr . 2012;161:962–963.

Lantos JD. Trisomy 13 and 18: treatment decisions in a stable gray zone. JAMA . 2016;316:396–398.

Lin HY, Lin SP, Chen YJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival of trisomy 18 in a medical center in Taipei, 1988-2004. Am J Med Genet . 2006;140A:945–951.

Lorenz JM, Hardart GE. Evolving medical and surgical management of infants with trisomy 18. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2014;26:169–176.

Mårild K, Stephansson O, Grahnquist L, et al. Down syndrome is associated with elevated risk of celiac disease: a nationwide case-control study. J Pediatr . 2013;163:237–242.

McCabe LL, Hickey F, McCabe ERB. Down syndrome: addressing the gaps. J Pediatr . 2011;159:525–526.

McDowell KM, Craven DI. Pulmonary complications of Down syndrome during childhood. J Pediatr . 2011;158:319–325.

Merritt TA, Catlin A, Wool C, et al. Trisomy 18 and trisomy 13: treatment and management decisions. Neoreviews . 2012;13:e40–e48.

Nelson KE, Hexem KR, Feudtner C. Inpatient hospital care of children with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 in the United States. Pediatrics . 2012;129:869–876.

Nelson KE, Rosella LC, Mahant S, Gutterman A. Survival and surgical interventions for children with trisomy 12 and 18. JAMA . 2016;316:420–428.

Nicolaides KH, Wright D, Poon C, et al. First-trimester contingent screening for trisomy 21 by biomarkers and maternal blood cell-free DNA testing. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol . 2013;42:41–50.

Norton ME, Jacobsson B, Swamy GK, et al. Cell-free DNA analysis for noninvasive examination of trisomy. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(17):1589–1597.

Papageorgiou EA, Karagrigoriou A, Tsaliki E, et al. Fetal-specific DNA methylation ratio permits noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21. Nat Med . 2011;17:510–514.

Rasmussen SA, Whitehead N, Collier SA, et al. Setting a public health research agenda for Down syndrome: summary of a meeting sponsored by the CDC and the National Down Syndrome Society. Am J Med Genet . 2008;46A:2998–3010.

Roizen NJ, Magyar CI, Kuschner ES, et al. A community cross-sectional survey of medical problems in 440 children with Down syndrome in New York state. J Pediatr . 2014;164:871–876.

Shin M, Besser LM, Kucik JE, et al. Prevalence of Down syndrome among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics . 2009;124:1565–1571.

Shott SR, Amin R, Chini B, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: should all children with Down syndrome be tested? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2006;132:432–436.

Van Gameren-Oosterom HBM, Fekkes M, van Wouwe JP, et al. Problem behavior of individuals with Down syndrome in a nationwide cohort assessed in late adolescence. J Pediatr . 2013;163:1396–1401.

Webb D, Roberts I, Vyas P. Haematology of Down syndrome. Arch Dis Child . 2007;92:F503–F507.

Weijerman ME, Van Furth M, Noordegraaf AV, et al. Prevalence, neonatal characteristics, and first-year mortality of Down syndrome: a national study. J Pediatr . 2008;152:15–19.

Wouters J, Weijerman ME, Van Forth AM, et al. Prospective human leukocyte antigen, endomysium immunoglobulin A antibodies, and transglutaminase antibodies testing for celiac disease in children with Down syndrome. J Pediatr . 2009;154:239–242.

Abnormalities of Chromosome Structure

Carlos A. Bacino, Brendan Lee

Translocations

Translocations, which involve the transfer of material from one chromosome to another, occur with a frequency of 1 in 500 liveborn human infants. They may be inherited from a carrier parent or appear de novo, with no other affected family member. Translocations are usually reciprocal or robertsonian, involving 2 chromosomes (Fig. 98.15 ).

Reciprocal translocations are the result of breaks in nonhomologous chromosomes, with reciprocal exchange of the broken segments. Carriers of a reciprocal translocation are usually phenotypically normal but are at an increased risk for miscarriage caused by transmission of unbalanced reciprocal translocations and for bearing chromosomally abnormal offspring. Unbalanced translocations are the result of abnormalities in the segregation or crossover of the translocation carrier chromosomes in the germ cells.

Robertsonian translocations involve 2 acrocentric chromosomes (chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22) that fuse near the centromeric region with a subsequent loss of the short arms. Because the short arms of all 5 pairs of acrocentric chromosomes have multiple copies of genes encoding for ribosomal RNA, loss of the short arm of 2 acrocentric chromosomes has no deleterious effect. The resulting karyotype has only 45 chromosomes, including the translocated chromosome, which consists of the long arms of the 2 fused chromosomes. Carriers of robertsonian translocations are usually phenotypically normal. However, they are at increased risk for miscarriage and unbalanced translocations in phenotypically abnormal offspring.

In some rare instances, translocations can involve 3 or more chromosomes, as seen in complex rearrangements. Another, less common type is the insertional translocation. Insertional translocations result from a piece of chromosome material that breaks away and later is reinserted inside the same chromosome at a different site or inserted in another chromosome.

Inversions

An inversion requires that a single chromosome break at 2 points; the broken piece is then inverted and joined into the same chromosome. Inversions occur in 1 in 100 live births. There are 2 types of inversions: pericentric and paracentric. In pericentric inversions the breaks are in the 2 opposite arms of the chromosome and include the centromere. They are usually discovered because they change the position of the centromere. The breaks in paracentric inversions occur in only 1 arm. Carriers of inversions are usually phenotypically normal, but they are at increased risk for miscarriages, typically in paracentric inversions, and chromosomally abnormal offspring in pericentric inversions.

Deletions and Duplications

Deletions involve loss of chromosome material and, depending on their location, can be classified as terminal (at the end of chromosomes) or interstitial (within the arms of a chromosome). They may be isolated or may occur along with a duplication of another chromosome segment. The latter typically occurs in unbalanced reciprocal chromosomal translocation secondary to abnormal crossover or segregation in a translocation or inversion carrier.

A carrier of a deletion is monosomic for the genetic information of the missing segment. Deletions are usually associated with intellectual disability and malformations. The most commonly observed deletions in routine chromosome preparations include 1p−, 4p−, 5p−, 9p−, 11p−, 13q−, 18p−, 18q−, and 21q− (Table 98.12 and Fig. 98.16 ), all distal or terminal deletions of the short or the long arms of chromosomes. Deletions may be observed in routine chromosome preparations, and deletions and translocations larger than 5-10 Mbp are usually visible microscopically.

Table 98.12

High-resolution banding techniques, FISH, and molecular studies such as aCGH can reveal deletions that are too small to be seen in ordinary or routine chromosome spreads (see Fig. 98.7 ). Microdeletions involve loss of small chromosome regions, the largest of which are detectable only with prophase chromosome studies and molecular methods. For submicroscopic deletions, the missing piece can only be detected using molecular methodologies such as DNA-based studies (e.g., aCGH, FISH). The presence of extra genetic material from the same chromosome is referred to as duplication . Duplications can also be sporadic or result from abnormal segregation in translocation or inversion carriers.

Microdeletions and microduplications usually involve regions that include several genes, so the affected individuals can have a distinctive phenotype depending on the number of genes involved. When such a deletion involves more than a single gene, the condition is referred to as a contiguous gene deletion syndrome (Table 98.13 ). With the advent of clinically available aCGH, a large number of duplications, most of them microduplications, have been uncovered. Many of those microduplication syndromes are the reciprocal duplications of the known deletions or microdeletion counterparts and have distinctive clinical features (Table 98.14 ).

Table 98.13

Table 98.14

DD, Developmental delay; ID, intellectual disability; FTT, failure to thrive; GH, growth hormone; MR, mental retardation.

Subtelomeric regions are often involved in chromosome rearrangements that cannot be visualized using routine cytogenetics. Telomeres, which are the distal ends of the chromosomes, are gene-rich regions. The distal structure of the telomeres is essentially common to all chromosomes, but proximal to these are unique regions known as subtelomeres, which typically are involved in deletions and other chromosome rearrangements. Small subtelomeric deletions, duplications, or rearrangements (translocations, inversions) may be relatively common in children with nonspecific intellectual disability and minor anomalies. Subtelomeric rearrangements have been found in 3–7% of children with moderate to severe intellectual disability and 0.5% of those with mild intellectual disability and can be detected by aCGH studies.

Telomere mutations and length abnormalities have also been associated with dyskeratosis congenita and other aplastic anemia syndromes, as well as pulmonary or hepatic fibrosis. Both the subtelomeric rearrangements and the microdeletion and microduplication syndromes are typically diagnosed by molecular techniques such as aCGH and multiple ligation-dependent primer amplification studies. Recent studies show that aCGH can detect 14–18% of abnormalities in patients who previously had normal chromosome studies.

Insertions

Insertions occur when a piece of a chromosome broken at 2 points is incorporated into a break in another part of a chromosome. A total of 3 breakpoints are then required, and they can occur between 2 or within 1 chromosome. A form of nonreciprocal translocation, insertions are rare. Insertion carriers are at risk of having offspring with deletions or duplications of the inserted segment.

Isochromosomes

Isochromosomes consist of 2 copies of the same chromosome arm joined through a single centromere and forming mirror images of one another. The most commonly reported autosomal isochromosomes tend to involve chromosomes with small arms. Some of the more common chromosome arms involved in this formation include 5p, 8p, 9p, 12p, 18p, and 18q. There is also a common isochromosome abnormality seen in long arm of the X chromosome and associated with Turner syndrome. Individuals who have 1 isochromosome X within 46 chromosomes are monosomic for genes in the lost short arm and trisomic for the genes present in the long arm of the X chromosome.

Marker and Ring Chromosomes

Marker chromosomes are rare and are usually chromosome fragments that are too small to be identified by conventional cytogenetics; they usually occur in addition to the normal 46 chromosomes. Most are sporadic (70%); mosaicism is often (50%) noted because of the mitotic instability of the marker chromosome. The incidence in newborn infants is 1 in 3,300, and the incidence in persons with intellectual disability is 1 in 300. The associated phenotype ranges from normal to severely abnormal, depending on the amount of chromosome material and number of genes included in the fragment.

Ring chromosomes, which are found for all human chromosomes, are rare. A ring chromosome is formed when both ends of a chromosome are deleted and the ends are then joined to form a ring. Depending on the amount of chromosome material that is lacking or in excess (if the ring is in addition to the normal chromosomes), a patient with a ring chromosome can appear normal or nearly normal or can have intellectual disability and multiple congenital anomalies.

Marker and ring chromosomes can be found in the cells of solid tumors of children the cells of whose organs do not contain this additional chromosomal material.

Bibliography

Abnormalities of Chromosome Structure

Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J Pediatr . 2011;159:332–339.

Battaglia A, Hoyme HE, Dallapiccola B, et al. Further delineation of deletion 1p36 syndrome in 60 patients: a recognizable phenotype and common cause of developmental delay and mental retardation. Pediatrics . 2008;121:404–410.

Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med . 2009;361:2353–2365.

Fillion M, Deal C, Van Vliet G. Retrospective study of the potential benefits and adverse events during growth hormone treatment in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediatr . 2009;154:230–233.

Gicquel C, Rossignol S, Cabrol S, et al. Epimutation of the telomeric imprinting center region on chromosome 11p15 in Silver-Russell syndrome. Nat Genet . 2005;37:1003–1007.

Mefford H, Shapr A, Baker C, et al. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N Engl J Med . 2008;359:1685–1698.

Peters J. Prader-Willi and snoRNAs. Nat Genet . 2008;40:688–689.

Rappold GA, Shanske A, Saenger P. All shook up by SHOX deficiency. J Pediatr . 2005;147:422–424.

Robin NH, Shprintzen RJ. Defining the clinical spectrum of deletion 22q11.2. J Pediatr . 2005;147:90–96.

Sahoo T, del Gaudio D, German JR, et al. Prader-Willi phenotype caused by paternal deficiency for the HBII-85 C/D box small nucleolar RNA cluster. Nat Genet . 2008;40:719–721.

Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, et al. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet . 2008;40:322–328.

Stafler P, Wallis C. Prader-Willi syndrome: who can have growth hormone? Arch Dis Child . 2008;93:341–345.

Vissers LELM, van Ravenswaaji CMA, Admiraal R, et al. Mutations in a new member of the chromodomain gene family cause CHARGE syndrome. Nat Genet . 2004;36:955–957.

Walter S, Sandig K, Hinkel GK, et al. Subtelomere FISH in 50 children with mental retardation and minor anomalies, identified by a checklist, selects 10 rearrangements including a de novo balanced translocation of chromosomes 17p13.3 and 20q13.33. Am J Med Genet . 2004;128A:364–373.

Youings S, Ellis K, Ennis S, et al. A study of reciprocal translocations and inversions detected by light microscopy with special reference to origin, segregation, and recurrent abnormalities. Am J Med Genet . 2004;126A:46–60.

Yu S, Graf WD, Shprintzen RJ. Genomic disorders on chromosome 22. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2012;24:665–671.

Sex Chromosome Aneuploidy

Carlos A. Bacino, Brendan Lee

About 1 in 400 males and 1 in 650 females have some form of sex chromosome abnormality. Considered together, sex chromosome abnormalities are the most common chromosome abnormalities seen in liveborn infants, children, and adults. Sex chromosome abnormalities can be either structural or numerical and can be present in all cells or in a mosaic form. Those affected with these abnormalities might have few or no physical or developmental problems (Table 98.15 ).

Table 98.15

| DISORDER | KARYOTYPE | APPROXIMATE INCIDENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Klinefelter syndrome | 47,XXY | 1/580 males |

| 48,XXXY | 1/50,000-1/80,000 male births | |

| Other (48,XXYY; 49,XXXYY; mosaics) | ||

| XYY syndrome | 47,XYY | 1/800-1,000 males |

| Other X or Y chromosome abnormalities | 1/1,500 males | |

| XX males | 46,XX | 1/20,000 males |

| Turner syndrome | 45,X | 1/2,500-1/5,000 females |

| Variants and mosaics | ||

| Trisomy X | 47,XXX | 1/1,000 females |

| 48,XXXX and 49,XXXXX | Rare | |

| Other X chromosome abnormalities | 1/3,000 females | |

| XY females | 46,XY | 1/20,000 females |

Turner Syndrome

Turner syndrome is a condition characterized by complete or partial monosomy of the X chromosome and defined by a combination of phenotypic features (Table 98.16 ). Half the patients with Turner syndrome have a 45,X chromosome complement. The other half exhibit mosaicism and varied structural abnormalities of the X or Y chromosome. Maternal age is not a predisposing factor for children with 45,X. Turner syndrome occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 female live births. In 75% of patients, the lost sex chromosome is of paternal origin (whether an X or a Y). 45,X is one of the chromosome abnormalities most often associated with spontaneous abortion. It has been estimated that 95–99% of 45,X conceptions are miscarried.

Clinical findings in the newborns can include small size for gestational age, webbing of the neck, protruding ears, and lymphedema of the hands and feet, although many newborns are phenotypically normal (Fig. 98.17 ). Older children and adults have short stature and exhibit variable dysmorphic features. Congenital heart defects (40%) and structural renal anomalies (60%) are common. The most common heart defects are bicuspid aortic valves, coarctation of the aorta, aortic stenosis, and mitral valve prolapse. The gonads are generally streaks of fibrous tissue (gonadal dysgenesis ). There is primary amenorrhea and lack of secondary sex characteristics. These children should receive regular endocrinologic testing (see Chapter 604 ). Most patients tend to be of normal intelligence, but intellectual disability is seen in up to 6% of affected children. They are also at increased risk for behavioral problems and deficiencies in spatial and motor perception. Guidelines for health supervision for children with Turner syndrome are published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and include pubertal induction, as well as treatment with growth hormone and oxandrolone.

Patients with 45,X/46,XY mosaicism can have Turner syndrome, although this form of mosaicism can also be associated with male pseudohermaphroditism, male or female genitalia in association with mixed gonadal dysgenesis, or a normal male phenotype. This variant is estimated to represent approximately 6% of patients with mosaic Turner syndrome. Some of the patients with Turner syndrome phenotype and a Y cell line exhibit masculinization. Phenotypic females with 45,X/46,XY mosaicism have a 15–30% risk of developing gonadoblastoma . The risk for the patients with a male phenotype and external testes is not so high, but tumor surveillance is nevertheless recommended. AAP has recommended the use of FISH analysis to look for Y chromosome mosaicism in all 45,X patients. If Y chromosome material is identified, laparoscopic gonadectomy is recommended.

Noonan syndrome shares many clinical features with Turner syndrome and was formerly called pseudo-Turner syndrome , although it is an autosomal dominant disorder resulting from mutations in several genes involved in the RAS-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway. The most common of these is PTPN11 (50%), which encodes a protein-tyrosine phosphatase (SHP-2) on chromosome 12q24.1. Other genes include SOS1 in 10–13%, RAF1 in 3–17%, RITI in 5%, KRAS <5%, BRAF <2%, MAP2K <2%, and NRAS (only few reported families). Overlapping phenotypes are seen in LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, deafness) syndrome, cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome, and Costello syndrome; these are Noonan-related disorders. Features common to Noonan syndrome include short stature, low posterior hairline, shield chest, congenital heart disease, and a short or webbed neck (Table 98.17 ). In contrast to Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome affects both sexes and has a different pattern of congenital heart disease, typically involving right-sided lesions.

Klinefelter Syndrome

Persons with Klinefelter syndrome are phenotypically male; this syndrome is the most common cause of hypogonadism and infertility in males and the most common sex chromosome aneuploidy in humans (see Chapter 601 ). Eighty percent of children with Klinefelter syndrome have a male karyotype with an extra chromosome X-47,XXY. The remaining 20% have multiple sex chromosome aneuploidies (48,XXXY; 48,XXYY; 49,XXXXY), mosaicism (46,XY/47,XXY), or structurally abnormal X chromosomes; the greater the aneuploidy, the more severe the mental impairment and dysmorphism. Early studies showed a birth prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000 males, but more recent studies suggest that the prevalence of 47,XXY appears has increased to approximately 1 in 580 liveborn males; the reasons for this are still unknown but hypothesized to be the result of environmental factors acting in spermatogenesis. Errors in paternal nondisjunction in meiosis I account for half the cases.

Puberty commences at the normal age, but the testes remain small. Patients develop secondary sex characters late, and 50% ultimately develop gynecomastia. They have taller stature. Because many patients with Klinefelter syndrome are phenotypically normal until puberty, the syndrome often goes undiagnosed until they reach adulthood, when their infertility leads to identification. Patients with 46,XY/47,XXY have a better prognosis for testicular function. Their intelligence shows variability and ranges from above to below average. Persons with Klinefelter syndrome can show behavioral problems, learning disabilities, and deficits in language. Problems with self-esteem often occur in adolescents and adults. Substance abuse, depression, and anxiety have been reported in adolescents with Klinefelter syndrome. Those who have higher X chromosome counts show impaired cognition. It has been estimated that each additional X chromosome reduces the IQ by 10-15 points, when comparing these individuals with typical siblings. The main effect is seen in language skills and social domains.

47,XYY

The incidence of 47,XYY is approximately 1 in 800-1,000 males, with many cases remaining undiagnosed, because most affected individuals have a normal appearance and normal fertility. The extra Y is the result of nondisjunction at paternal meiosis II. Those with this abnormality have normal intelligence but are at risk for learning disabilities. Behavioral abnormalities, including hyperactive behavior, pervasive developmental disorder, and aggressive behavior, have been reported. Early reports that assigned stigmata of criminality to this disorder have long been disproved.

Bibliography

Sex Chromosome Aneuploidy

Bardsley MZ, Kowal K, Levy C, et al. 47,XYY syndrome: clinical phenotype and timing of ascertainment. J Pediatr . 2013;163:1085–1094.

Binder G, Grathwol S, von Loeper K, et al. Health and quality of life in adults with Noonan syndrome. J Pediatr . 2012;161:501–505.

Gault EJ, Perry RJ, Cole TJ, et al. Effect of oxandrolone and timing of pubertal induction on final height in Turner's syndrome: randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. BMJ . 2011;342:907.

Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, et al. Klinefelter's syndrome. Lancet . 2004;364:273–283.

Lee BH, Kim JM, Jin HY, et al. Spectrum of mutations in Noonan syndrome and their correlation with phenotypes. J Pediatr . 2011;159:1029–1035.

Lin AE. Focus on the heart and aorta in Turner syndrome. J Pediatr . 2007;150:572–574.

Massa G, Verlinde F, De Schepper J, et al. Trends in age at diagnosis of Turner syndrome. Arch Dis Child . 2005;90:267–268.

Mazzanti L, Cicognani A, Baldazzi L, et al. Gonadoblastoma in Turner syndrome and Y chromosome–derived material. Am J Med Genet . 2005;135A:150–154.

Roberts AE, Allanson JE, Tartaglia M, et al. Noonan syndrome. Lancet . 2013;381:333–340.

Romano AA, Allanson JE, Dahlgren J, et al. Noonan syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics . 2010;126:746–759.

Sybert VP, McCauley E. Turner's syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2004;351:1227–1238.

Zeger MPD, Zinn AR, Lahlou N, et al. Effect of ascertainment and genetic features on the phenotype of Klinefelter syndrome. J Pediatr . 2008;152:716–722.

Fragile Chromosome Sites

Carlos A. Bacino, Brendan Lee

Fragile sites are regions of chromosomes that show a tendency for separation, breakage, or attenuation under particular growth conditions. They visually appear as a gap in the staining in chromosome studies. At least 120 chromosomal loci, many of them heritable, have been identified as fragile sites in the human genome (see Table 97.2 ).

A clinically significant fragile site is on the distal long arm of chromosome Xq27.3 associated with the fragile X syndrome . Fragile X syndrome accounts for 3% of males with intellectual disability. There is another fragile site on the X chromosome (FRAXE on Xq28) that has also been implicated in mild intellectual disability. The FRA11B (11q23.3) breakpoints are associated with Jacobsen syndrome (condition caused by deletion of the distal long arm of chromosome 11). Fragile sites can also play a role in tumorigenesis. In fragile X syndrome the CGG repeat expansion silences the gene producing fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) that regulates the translation of multiple mRNAs to specific proteins, thus affecting synaptic function. FMRP deficiency upregulates the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) 5 pathway. FMRP deficiency also alters the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9.

The main clinical manifestations of fragile X syndrome in affected males are intellectual disability, autistic behavior, postpubertal macroorchidism, hyperextensible finger joints, and characteristic facial features (Table 98.18 ). The facial features, which include a long face, large ears, and a prominent square jaw, become more obvious with age. Females affected with fragile X show varying degrees of intellectual disability and/or learning disabilities. Diagnosis of fragile X syndrome is possible by DNA testing that shows an expansion of a triplet DNA repeat inside the FMR1 gene on the X chromosome >200 repeats. The expansion involves an area of the gene that contains a variable number of trinucleotide (CGG) repeats (typically <50 in unaffected individuals). The larger the triplet repeat expansion, the more significant is the intellectual disability. In cases where the expansion is large, females can also manifest different degrees of intellectual disability. Males with premutation triple repeat expansions (55-200 repeats) have been found to have an adult, late-onset, progressive neurodegenerative disorder known as fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome . Females with premutation triple repeat expansions are at high risk for developing premature ovarian failure (POF).

Table 98.18

Clinical Features of Full and Premutation FMR1 Alleles

| DISORDER | PHENOTYPE | ONSET | PENETRANCE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive or Behavioral | Clinical and Imaging Signs | |||

| FULL MUTATION (>200 repeats) | ||||

| FXS |

Developmental delay: mean IQ = 42 in M; IQ is higher if significant residual FMRP is produced (e.g., females and mosaic males or unmethylated full mutations) Autism 20–30% ADHD 80% Anxiety 70–100% |

Hypothalamic dysfunction: macroorchidism, 40%* Facial features, 60%,* large cupped ears, elongated face, high arched palate Connective tissue abnormalities: mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, joint laxity, flat feet Others: seizures (20%), recurrent otitis media (60%), strabismus (8–30%) |

Neonate | M 100% |

| PREMUTATION (55-200 repeats) | ||||

| Female reproductive symptoms | POF (<40 yr) | Adult/childhood | F 20% † | |

| Early menopause (<45 yr) | F 30% † | |||

| FXTAS | Cognitive decline, dementia, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, depression | Gait ataxia, intention tremor, parkinsonism, neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction | >50 yr |

M 33% ‡ F unknown |

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | ADHD, autism, or developmental delay | Mild features of FXS | Childhood | 8% (1/13)* |

* Frequency of those signs in prepubertal boys; one third of boys with FXS are without classic facial features. Macroorchidism is present in 90% of men.

† Maximum penetrance reported for allele size approximately 80-90 CGG repeats.

‡ Penetrance is correlated with age and repeat size.

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; F, female; FMRP, fragile X mental retardation protein; FXS, fragile X syndrome; FXTAS, fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome; M, male; POF, premature ovarian failure.

From Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, et al: Fragile-X syndrome and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: two faces of FMRI, Lancet Neurol 6:45–55, 2007, Table 1.

Table 98.19 outlines therapy of the diverse neuropsychiatric manifestations associated with fragile X syndrome. Inhibitors of mGluR (overexpressed in fragile X) are undergoing clinical trials. In preliminary trials, minocycline (lowers MMP-9) has resulted in short-term improvements in anxiety, mood, and the clinical Global Impression Scale.

Table 98.19

Therapy for FMR1 -Related Disorders

| DISORDER | SYMPTOM | THERAPY AND INTERVENTIONS | FUTURE POTENTIAL THERAPY |

|---|---|---|---|

| FULL MUTATION | |||

| FXS* | ADHD | Stimulants | mGluR5 antagonists |

| Anxiety, hyperarousal, aggressive outbursts | SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics, occupational therapy, behavioral therapy, counseling | mGluR5 antagonists | |

| Seizures | Carbamazepine, valproic acid | mGluR5 antagonists | |

| Cognitive deficit | Occupational therapy, speech therapy, special education support | mGluR5 antagonists | |

| PREMUTATION | |||

| POF | Premature ovarian failure | Reproductive counseling, egg donation | Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue |

| Hormone replacement therapy | |||

| FXTAS † | Intention tremor | β-Blockers | |

| Parkinsonism | Carbidopa/levodopa | ||

| Cognitive decline, dementia | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | ||

| Anxiety, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, depression | Venlafaxine, SSRIs | ||

| Neuropathic pain | Gabapentin | ||

* These data are based on a survey in 2 large referral centers. Drugs for anxiety were more frequently prescribed than those for neurologic signs.

† There have been no controlled studies to assess drugs for FXTAS. These data were collected through a questionnaire study (n = 56).

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FXS, fragile-X syndrome; FXTAS, fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome; POF, premature ovarian failure; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

From Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, et al: Fragile-X syndrome and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: two faces of FMRI, Lancet Neurol 2006:45–55, 2007, Table 2.

Bibliography

Fragile Chromosome Sites

Abrams L, Cronister A, Brown WT, et al. Newborn, carrier, and early childhood screening recommendations for fragile X. Pediatrics . 2012;130:1126–1135.

Dobkin C, Radu G, Ding XH, et al. Fragile X prenatal analyses show full mutation females at high risk for mosaic Turner syndrome: fragile X leads to chromosome loss. Am J Med Genet . 2009;149A:2152–2157.

Hersh JH, Saul RA. Committee on Genetics: Clinical report—health supervision for children with fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics . 2011;127:994–1006.

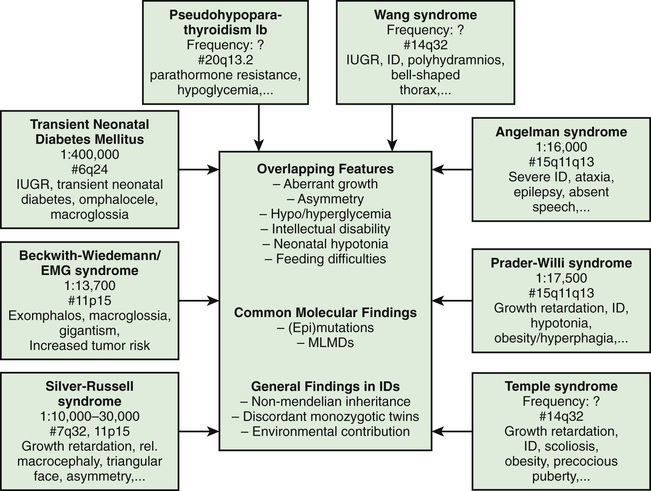

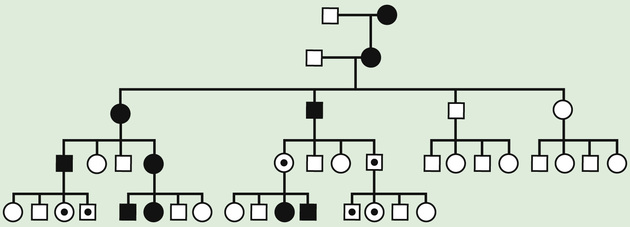

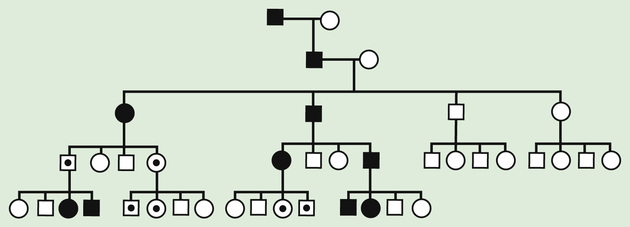

Hess LG, Fitzpatrick SE, Nguyen DV, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose sertraline in young children with fragile X syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2016;37:619–628.