Patterns of Genetic Transmission

Daryl A. Scott, Brendan Lee

Family History and Pedigree Notation

The family history remains the most important screening tool for pediatricians in identifying a patient's risk for developing a wide range of diseases, from multifactorial conditions such as diabetes and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, to single-gene disorders such as sickle cell anemia and cystic fibrosis. Through a detailed family history, the physician can often ascertain the mode of genetic transmission and the risks to family members. Because not all familial clustering of disease is caused by genetic factors, a family history can also identify common environmental and behavioral factors that influence the occurrence of disease. The main goal of the family history is to identify genetic susceptibility, and the cornerstone of the family history is a systematic and standardized pedigree.

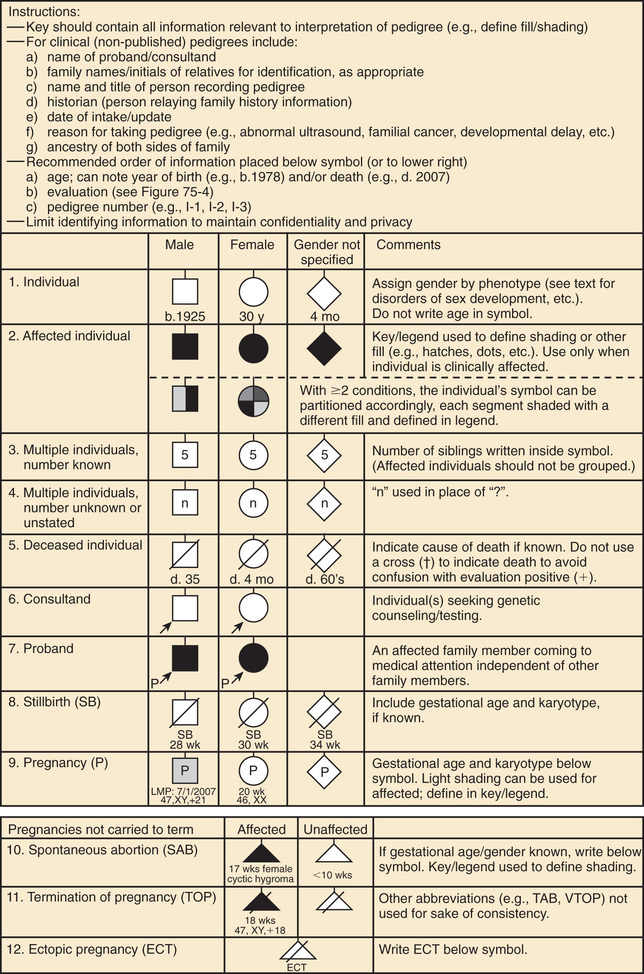

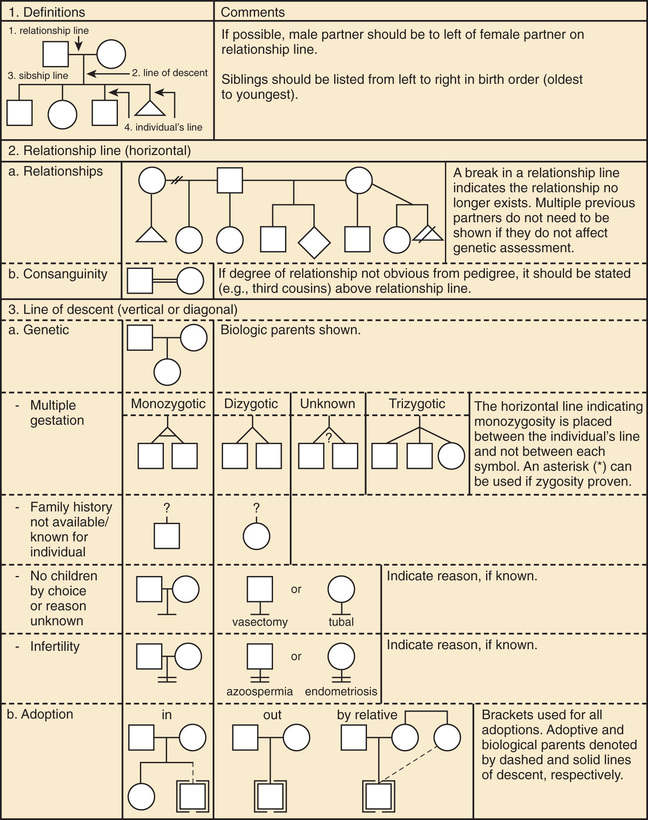

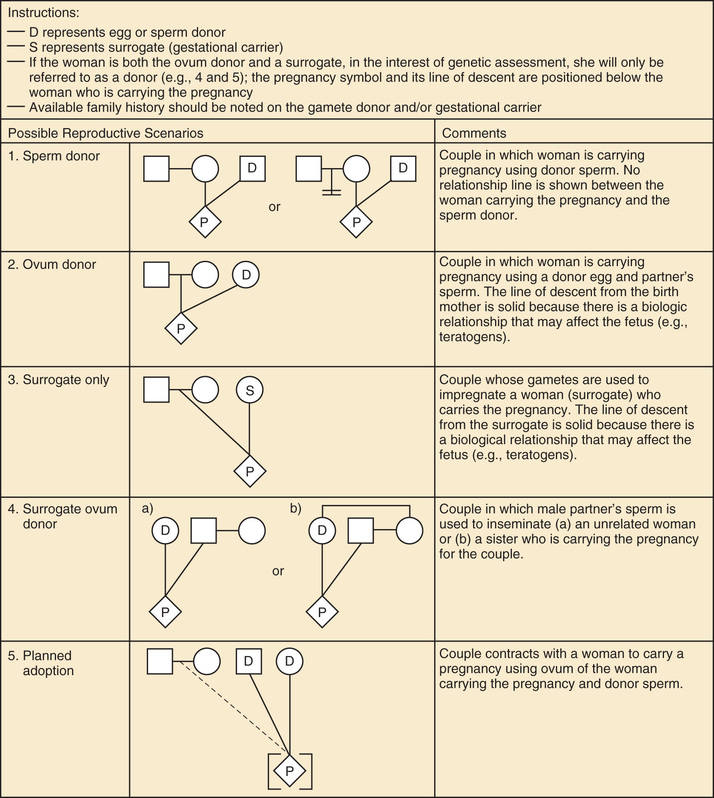

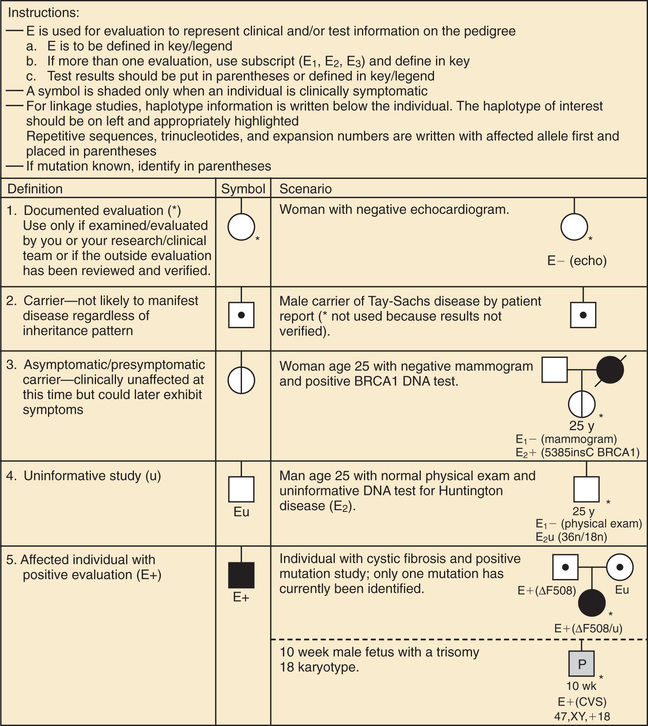

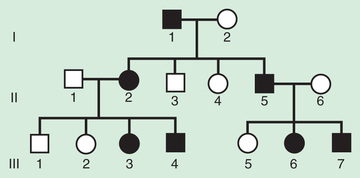

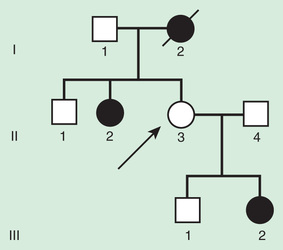

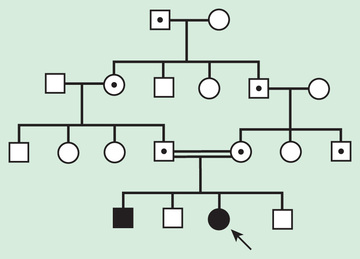

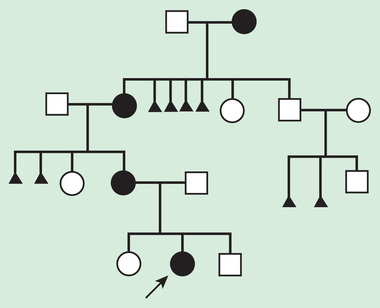

A pedigree provides a graphic depiction of a family's structure and medical history. It is important when taking a pedigree to be systematic and use standard symbols and configurations so that anyone can read and understand the information (Figs. 97.1 to 97.4 ). In the pediatric setting, the proband is typically the child or adolescent who is being evaluated. The proband is designated in the pedigree by an arrow.

A 3 to 4–generation pedigree should be obtained for every new patient as an initial screen for genetic disorders segregating within the family. The pedigree can provide clues to the inheritance pattern of these disorders and can aid the clinician in determining the risk to the proband and other family members. The closer the relationship of the proband to the person in the family with the genetic disorder, the greater is the shared genetic complement. First-degree relatives, such as a parent, full sibling, or child, share one-half their genetic information on average; first cousins share one-eighth. Sometimes the person providing the family history may mention a distant relative who is affected with a genetic disorder. In such cases a more extensive pedigree may be needed to identify the risk to other family members. For example, a history of a distant maternally related cousin with intellectual disability caused by fragile X syndrome can still place a male proband at an elevated risk for this disorder.

Mendelian Inheritance

There are 3 classic forms of genetic inheritance: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked . These are referred to as mendelian inheritance forms, after Gregor Mendel, the 19th-century monk whose experiments led to the laws of segregation of characteristics, dominance, and independent assortment . These remain the foundation of single-gene inheritance.

Autosomal Dominant Inheritance

Autosomal dominant inheritance is determined by the presence of one abnormal gene on one of the autosomes (chromosomes 1-22). Autosomal genes exist in pairs, with each parent contributing 1 copy. In an autosomal dominant trait, a change in 1 of the paired genes affects the phenotype of an individual, even though the other copy of the gene is functioning correctly. A phenotype can refer to a physical manifestation, a behavioral characteristic, or a difference detectable only through laboratory tests.

The pedigree for autosomal dominant disorders demonstrates certain characteristics. These disorders show a vertical transmission (parent-to-child) pattern and can appear in multiple generations. In Fig. 97.5 , this is illustrated by individual I.1 passing on the changed gene to II.2 and II.5. An affected individual has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of passing on the deleterious gene in each pregnancy and, therefore, of having a child affected by the disorder. This is referred to as the recurrence risk for the disorder. Unaffected individuals (family members who do not manifest the trait and do not harbor a copy of the deleterious gene) do not pass the disorder to their children. Males and females are equally affected.

Although not a characteristic per se, the finding of male-to-male transmission essentially confirms autosomal dominant inheritance. Vertical transmission can also be seen with X-linked traits. However, because a father passes on his Y chromosome to a son, male-to-male transmission cannot be seen with an X-linked trait. Therefore, male-to-male transmission eliminates X-linked inheritance as a possible explanation. Although male-to-male transmission can occur with Y-linked genes as well, there are very few Y-linked disorders, compared with thousands having the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

Although parent-to-child transmission is a characteristic of autosomal dominant inheritance, many patients with an autosomal dominant disorder have no history of an affected family member, for several possible reasons. First, the patient may have the disorder due to a de novo (new) mutation that occurred in the DNA of the egg or sperm that formed that individual. Second, many autosomal dominant conditions demonstrate incomplete penetrance , meaning that not all individuals who carry the mutation have phenotypic manifestations. In a pedigree this can appear as a skipped generation , in which an unaffected individual links 2 affected persons (Fig. 97.6 ). There are many potential reasons that a disorder might exhibit incomplete penetrance, including the effect of modifier genes, environmental factors, gender, and age. Third, individuals with the same autosomal dominant variant can manifest the disorder to different degrees. This is termed variable expression and is a characteristic of many autosomal dominant disorders. Fourth, some spontaneous genetic mutations occur not in the egg or sperm that forms a child, but rather in a cell in the developing embryo. Such events are referred to as somatic mutations , and because not all cells are affected, the change is said to be mosaic . The phenotype caused by a somatic mutation can vary but is usually milder than if all cells were affected by the mutation. In germline mosaicism the mutation occurs in cells that populate the germline that produces eggs or sperm. An individual who is germline mosaic might not have any manifestations of the disorder but may produce multiple eggs or sperm that are affected by the mutation.

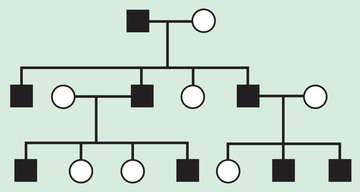

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

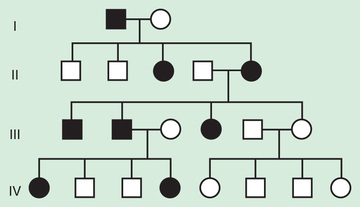

Autosomal recessive inheritance requires deleterious variants in both copies of a gene to cause disease. Examples include cystic fibrosis and sickle cell disease. Autosomal recessive disorders are characterized by horizontal transmission , the observation of multiple affected members of a kindred in the same generation, but no affected family members in other generations (Fig. 97.7 ). They are associated with a recurrence risk of 25% for carrier parents who have had a previous affected child. Male and female offspring are equally likely to be affected, although some traits exhibit differential expression between sexes. The offspring of consanguineous parents are at increased risk for rare, autosomal recessive traits due to the increased chance that that both parents may carry a gene affected by a deleterious mutation that they inherited from a common ancestor. Consanguinity between parents of a child with a suspected genetic disorder implies, but certainly does not prove, autosomal recessive inheritance. Although consanguineous unions are uncommon in Western society, in other parts of the world (southern India, Japan, and the Middle East) as high as 50% of all children may be conceived in consanguineous unions. The risk of a genetic disorder for the offspring of a first-cousin union (6–8%) is about double the risk in the general population (3–4%).

Every individual probably has several rare, deleterious recessive pathogenic sequence variants. Because most pathogenic variants carried in the general population occur at a very low frequency, it does not make economic sense to screen the entire population in order to identify the small number of persons who carry these variants. As a result, these variants typically remain undetected unless an affected child is born to a couple who both carry pathogenic variants affecting the same gene.

However, in some genetic isolates (small populations isolated by geography, religion, culture, or language), certain rare recessive pathogenic variants are much more common than in the general population. Even though there may be no known consanguinity, couples from these genetic isolates have a greater chance of sharing pathogenic alleles inherited from a common ancestor. Screening programs have been developed among some such groups to detect persons who carry common disease-causing variants and therefore are at increased risk for having affected children. A variety of autosomal recessive conditions are more common among Ashkenazi Jews than in the general population. Couples of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry should be offered prenatal or preconception screening for Gaucher disease type 1 (carrier rate 1 : 14), cystic fibrosis (1 : 25), Tay-Sachs disease (1 : 25), familial dysautonomia (1 : 30), Canavan disease (1 : 40), glycogen storage disease type 1A (1 : 71), maple syrup urine disease (1 : 81), Fanconi anemia type C (1 : 89), Niemann-Pick disease type A (1 : 90), Bloom syndrome (1 : 100), mucolipidosis IV (1 : 120), and possibly neonatal familial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia.

The prevalence of carriers of certain autosomal recessive variants in some larger populations is unusually high. In such cases, heterozygote advantage is postulated. The carrier frequencies of sickle cell disease in the African population and of cystic fibrosis in the northern European population are much higher than would be expected from the rate of new mutations. In these populations, heterozygous carriers may have had an advantage in terms of survival and reproduction over noncarriers. In sickle cell disease the carrier state is thought to confer some resistance to malaria; in cystic fibrosis the carrier state has been postulated to confer resistance to cholera or enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infections. Population-based carrier screening for cystic fibrosis is recommended for persons of northern European and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry; population-based screening for sickle cell disease is recommended for persons of African ancestry.

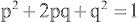

If the frequency of an autosomal recessive disease is known, the frequency of the heterozygote or carrier state can be calculated from the Hardy-Weinberg formula:

p2+2pq+q2=1

where p is the frequency of one of a pair of alleles and q is the frequency of the other. For example, if the frequency of cystic fibrosis among white Americans is 1 in 2,500 (p2 ), then the frequency of the heterozygote (2pq) can be calculated: If p2 = 1/2,500, then p = 1/50 and q = 49/50; 2pq = 2 × (1/50) × (49/50) = 98/2500, or 3.92%.

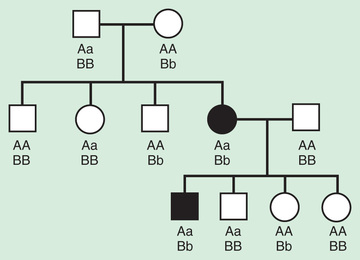

Pseudodominant Inheritance

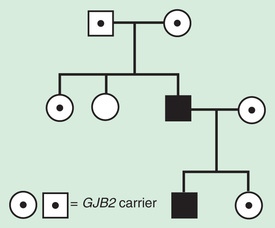

Pseudodominant inheritance refers to the observation of apparent dominant (parent to child) transmission of a known autosomal recessive disorder (Fig. 97.8 ). This occurs when a homozygous affected individual has a partner who is a heterozygous carrier. This is most likely to occur for relatively common recessive traits within a population, such as sickle cell anemia or nonsyndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss caused by deleterious mutations in the GJB2 , the gene that encodes connexin 26.

X-Linked Inheritance

X-linked inheritance describes the inheritance pattern of most disorders caused by deleterious changes in genes located on the X chromosome (Fig. 97.9 ). In X-liked disorders, males are more commonly affected than females. Female carriers of these disorders are generally unaffected, or if affected, they are affected more mildly than males. In each pregnancy, female carriers have a 25% chance of having an affected son, a 25% chance of having a carrier daughter, and a 50% chance of having a child that does not inherit the mutated X-linked gene. Since affected males pass their X chromosome to all their daughters and their Y chromosome to all their sons, they have a 50% chance of having an unaffected son that does not carry the disease gene and a 50% chance of having a daughter who is a carrier. Male-to-male transmission excludes X-linked inheritance but is seen with autosomal dominant and Y-linked inheritance.

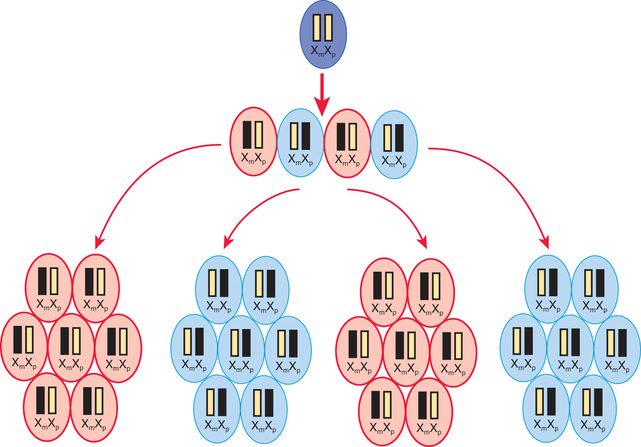

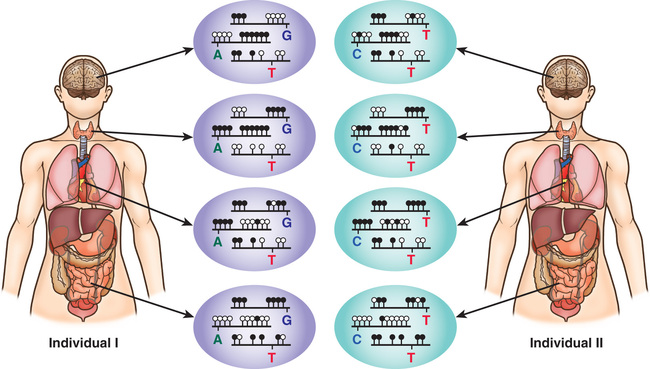

A female occasionally exhibits signs of an X-linked trait similar to a male. This occurs rarely from homozygosity for an X-linked trait or the presence of a sex chromosome abnormality (45,X or 46,XY female) or skewed or nonrandom X-inactivation. X chromosome inactivation occurs early in development and involves the random and irreversible inactivation of most genes on one X chromosome in female cells (Fig. 97.10 ). In some cases, a preponderance of cells inactivates the same X chromosome, resulting in phenotypic expression of an X-linked pathogenic variant if it resides on the active chromosome. This can occur because of chance, selection against cells that have inactivated the X chromosome carrying the normal gene, or an X chromosome abnormality that results in inactivation of the X chromosome carrying the normal gene.

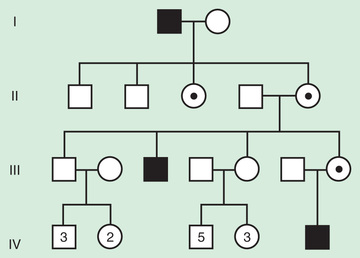

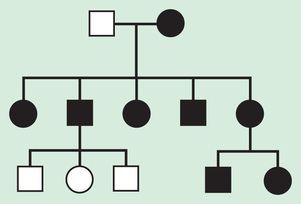

In some X-linked disorders, both hemizygous males and heterozygous females who carry an affected X–linked gene have similar phenotypic manifestations. In these cases, an affected male will have a 50% chance of having an affected daughter and a 50% chance of having an unaffected son in each pregnancy, whereas half the male and female offspring of an affected woman will be affected (Fig. 97.11 ). Some X-linked conditions are lethal in a high percentage of males, such as incontinentia pigmenti (see Chapter 614.7 ). In such cases the pedigree typically shows only affected females and an overall female/male ratio of 2 : 1, with an increased number of miscarriages (Fig. 97.12 ).

Y-Linked Inheritance

There are few Y-linked traits. These demonstrate only male-to-male transmission, and only males are affected (Fig. 97.13 ). Most Y-linked genes are related to male sex determination and reproduction and are associated with infertility. Therefore, it is rare to see familial transmission of a Y-linked disorder. However, advances in assisted reproductive technologies might make it possible to have familial transmission of male infertility.

Inheritance Associated With Pseudoautosomal Regions

Of special note are the pseudoautosomal regions on the X and Y chromosomes. Since these regions are made up of homologous sequences of nucleotides, genes that are located in these regions are present in equal numbers among both males and females. SHOX is one of the best-characterized disease genes located in these regions. Heterozygous SHOX mutations cause Leri-Weil dyschondrosteosis , a rare skeletal dysplasia that involves bilateral bowing of the forearms with dislocations of the ulna at the wrist and generalized short stature. Homozygous SHOX mutations cause the much more severe Langer mesomelic dwarfism .

Digenic Inheritance

Digenic inheritance explains the occurrence of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in children of parents who each carry a pathogenic variant in a different RP-associated gene (Fig. 97.14 ). Both parents have normal vision, as would be expected, but their offspring who are double heterozygotes —having inherited both mutations—develop RP. Digenic pedigrees can exhibit characteristics of both autosomal dominant (vertical transmission) and autosomal recessive inheritance (1 in 4 recurrence risk). A couple in which the 2 unaffected partners are carriers for mutation in 2 different RP-associated genes that show digenic inheritance have a 1 in 4 risk of having an affected child, similar to what is seen in autosomal recessive inheritance. However, their affected children, and affected children in subsequent generations, have a 1 in 4 risk of transmitting both mutations to their offspring, who would be affected (vertical transmission).

Pseudogenetic Inheritance and Familial Clustering

Sometimes nongenetic reasons for the occurrence of a particular disease in multiple family members can produce a pattern that mimics genetic transmission. These nongenetic factors can include identifiable environmental factors, teratogenic exposures, or as yet undetermined or undefined factors. Examples of identifiable factors might include multiple siblings in a family having asthma because of exposure to cigarette smoke from their parents or having failure to thrive, developmental delay, and unusual facial appearance caused by exposure to alcohol during pregnancy.

In some cases the disease is sufficiently common in the general population that some familial clustering occurs simply by chance. Breast cancer affects 11% of all women, and it is possible that several women in a family will develop breast cancer even in the absence of a genetic predisposition. However, hereditary breast cancer associated with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 should be suspected in any individual who has a personal history of breast cancer with onset before age 50, early-onset breast and ovarian cancer at any age, bilateral or multifocal breast cancer, a family history of breast cancer or breast and ovarian cancer consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance, or a personal or family history of male breast cancer.

Nonetheless, such clustering within families may be caused by as yet undefined genetic factors or unidentified pathogenic sequence variants (nuclear or mitochondrial).

Nontraditional Inheritance

Some genetic disorders are inherited in a manner that does not follow classical mendelian patterns. Nontraditional inheritance is seen in mitochondrial disorders, triplet repeat expansion diseases, and imprinting defects.

Mitochondrial Inheritance

An individual's mitochondrial genome is entirely derived from the mother because sperm contain relatively few mitochondria, and these are degradated after fertilization. It follows that mitochondrial inheritance is essentially maternal inheritance . A woman with a mitochondrial genetic disorder can have affected offspring of either sex, but an affected father cannot pass on the disease to his offspring (Fig. 97.15 ). Mitochondrial DNA mutations are often deletions or point mutations; overall, 1 person in 400 has a maternally inherited pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutation (see Chapter 106 ). In individual families, mitochondrial inheritance may be difficult to distinguish from autosomal dominant or X-linked inheritance, but in many cases, the sex of the transmitting and nontransmitting parents can suggest a mitochondrial basis (Table 97.1 ).

Table 97.1

Representative Examples of Disorders Caused by Mutations in Mitochondrial DNA and Their Inheritance

| DISEASE | PHENOTYPE | MOST FREQUENT MUTATION IN mtDNA MOLECULE | HOMOPLASMY vs HETEROPLASMY | INHERITANCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leber hereditary optic neuropathy | Rapid optic nerve atrophy, leading to blindness in young adult life; sex bias approximately 50% males with visual loss, only 10% females | Substitution p.Arg340His in ND1 gene of complex I of electron transport chain; other complex I missense mutations | Homoplasmic (usually) | Maternal |

| NARP, Leigh disease | N europathy, a taxia, r etinitis p igmentosa, developmental delay, intellectual disability lactic academia | Point mutations in ATPase subunit 6 gene | Heteroplasmic | Maternal |

| MELAS | M itochondrial e ncephalomyopathy, l actic a cidosis, and s trokelike episodes; may manifest only as diabetes mellitus or deafness | Point mutation in tRNALeu | Heteroplasmic | Maternal |

| MERRF | M yoclonic e pilepsy, r agged r ed f ibers in muscle, ataxia, sensorineural deafness | Point mutation in tRNALys | Heteroplasmic | Maternal |

| Deafness | Progressive sensorineural deafness, often induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics | m.1555A>G mutation in 12S rRNA | Homoplasmic | Maternal |

| Nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness | m.7445A>G mutation in 12S rRNA | Homoplasmic | Maternal | |

| Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) | Progressive weakness of extraocular muscles, cardiomyopathy, ptosis, heart block, ataxia, retinal pigmentation, diabetes | The common MELAS point mutation in tRNALys ; large deletions similar to KSS | Heteroplasmic | Maternal if point mutations |

| Pearson syndrome | Pancreatic insufficiency, pancytopenia, lactic acidosis | Large deletions | Heteroplasmic | Sporadic, somatic mutations |

| Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS) | PEO of early onset with heart block, retinal pigmentation | 5-kb large deletion | Heteroplasmic | Sporadic, somatic mutations |

mtDNA, Mitochondrial DNA; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; tRNA, transfer RNA.

From Nussbaum RL, McInnes RR, Willard HF, editors: Thompson & Thompson genetics in medicine, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders, p 246.

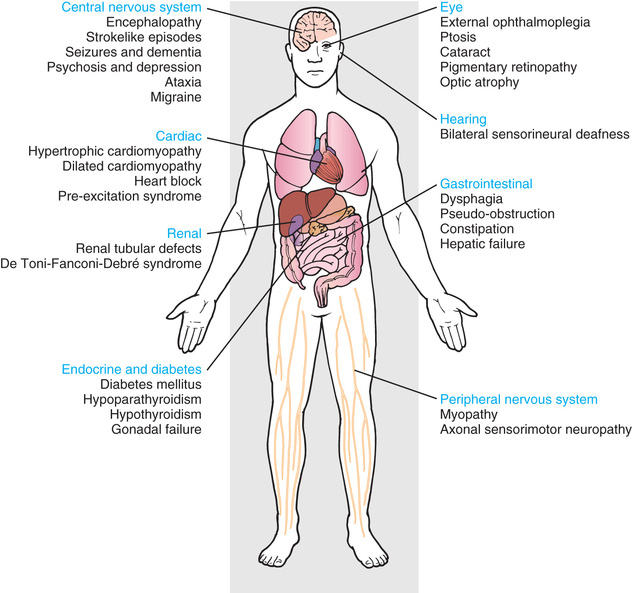

The mitochondria are the cell's suppliers of energy, and it is not surprising that the organs that are most affected by the presence of abnormal mitochondria are those that have the greatest energy requirements, such as the brain, muscle, heart, and liver (see Chapters 105.4 , 388 , 616.2 , and 629.4 ) (Fig. 97.16 ). Common manifestations include developmental delay, seizures, cardiac dysfunction, decreased muscle strength and tone, and hearing and vision problems.

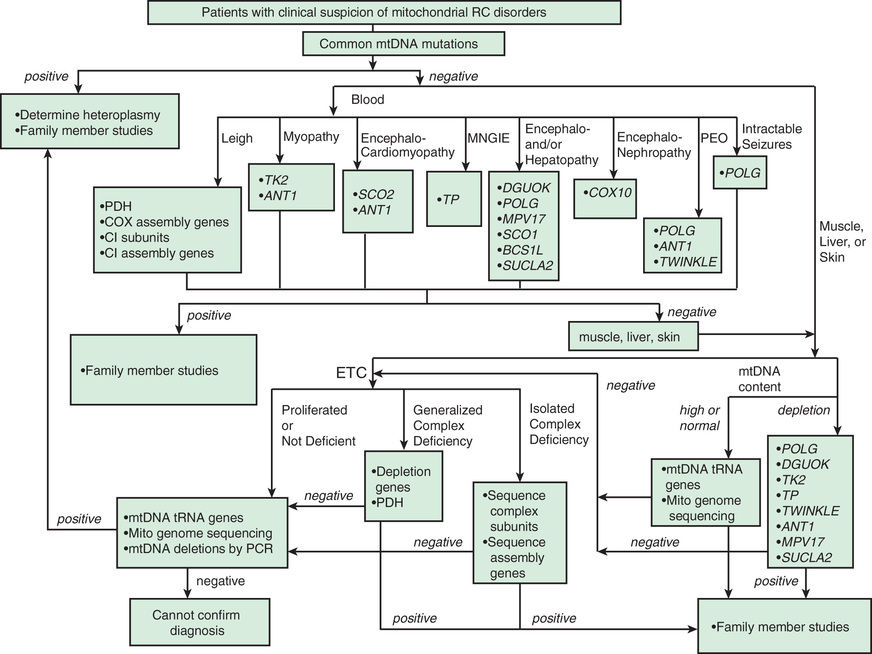

Mitochondrial diseases can be highly variable in clinical manifestation. This is partly because cells can contain multiple mitochondria, each bearing several copies of the mitochondrial genome. Thus a cell can have a mixture of normal and abnormal mitochondrial genomes, which is referred to as heteroplasmy . In contrast, homoplasmy refers a state in which all copies of the mitochondrial genome carry the same sequence variant. Unequal segregation of mitochondria carrying normal and abnormal genomes and replicative advantage can result in varying degrees of heteroplasmy in the cells of an affected individual, including the individual ova of an affected female. Because of this, a mother may be asymptomatic yet have children who are severely affected. The level of heteroplasmy at which disease symptoms typically appear can also vary based on the type of mitochondrial variant. Detection of mitochondrial genome variants can require sampling of the affected tissue for DNA analysis. In some tissues, such as blood, testing for mitochondrial DNA variants may be inadequate because the variant may be found primarily in affected tissues such as muscle (Fig. 97.17 ).

Growth and differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) and blood lactate levels are screening tests for mitochondrial disorders.

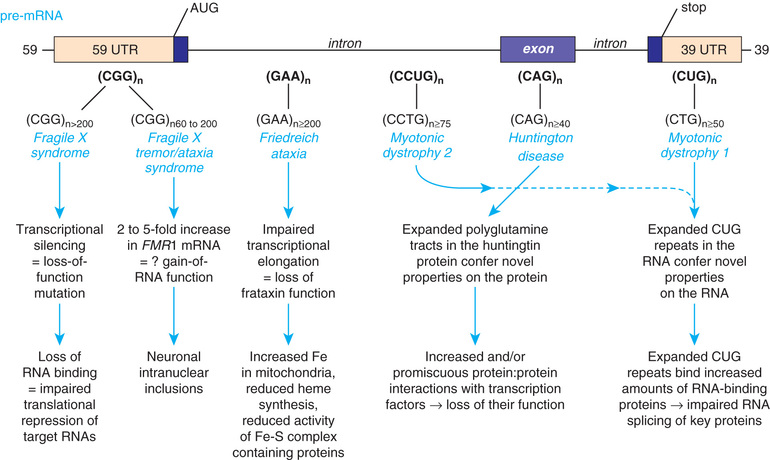

Triplet Repeat Expansion Disorders

Triplet repeat expansion disorders are distinguished by the special dynamic nature of the disease-causing variant. Triplet repeat expansion disorders include fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, Huntington disease, and spinocerebellar ataxias (Table 97.2 and Fig. 97.18 ). These disorders are caused by expansion in the number of 3-bp repeats. The fragile X gene, FMR1, normally has 5-40 CGG triplets. An error in replication can result in expansion of that number to a level in the gray zone between 41 and 58 repeats, or to a level referred to as premutation , which comprises 59-200 repeats. Some premutation carriers, more often males, develop fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) as adults. Female premutation carriers are at risk for fragile X–associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI ). Persons with a premutation are also at risk for having the repeat expand further in subsequent meiosis, thus crossing into the range of a full mutation (>200 repeats) in offspring. With this number of repeats, the FMR1 gene becomes hypermethylated, and protein production is lost.

Table 97.2

Diseases Associated With Polynucleotide Repeat Expansions

| DISEASE | DESCRIPTION | REPEAT SEQUENCE | NORMAL RANGE | ABNORMAL RANGE | PARENT IN WHOM EXPANSION USUALLY OCCURS | LOCATION OF EXPANSION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CATEGORY 1 | ||||||

| Huntington disease | Loss of motor control, dementia, affective disorder | CAG | 6-34 | 36-100 or more | More often through father | Exon |

| Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy | Adult-onset motor-neuron disease associated with androgen insensitivity | CAG | 11-34 | 40-62 | More often through father | Exon |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 | Progressive ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria | CAG | 6-39 | 41-81 | More often through father | Exon |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 | Progressive ataxia, dysarthria | CAG | 15-29 | 35-59 | — | Exon |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado-Joseph disease) | Dystonia, distal muscular atrophy, ataxia, external ophthalmoplegia | CAG | 13-36 | 68-79 | More often through father | Exon |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 | Progressive ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus | CAG | 4-16 | 21-27 | — | Exon |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 | Progressive ataxia, dysarthria, retinal degeneration | CAG | 7-35 | 38-200 | More often through father | — |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 17 | Progressive ataxia, dementia, bradykinesia, dysmetria | CAG | 29-42 | 47-55 | — | Exon |

| Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy/Haw River syndrome | Cerebellar atrophy, ataxia, myoclonic epilepsy, choreoathetosis, dementia | CAG | 7-25 | 49-88 | More often through father | Exon |

| CATEGORY 2 | ||||||

| Pseudoachondroplasia, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia | Short stature, joint laxity, degenerative joint disease | GAC | 5 | 6-7 | — | Exon |

| Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy | Proximal limb weakness, dysphagia, ptosis | GCG | 6 | 7-13 | — | Exon |

| Cleidocranial dysplasia | Short stature, open skull sutures with bulging calvaria, clavicular hypoplasia, shortened fingers, dental anomalies | GCG, GCT, GCA | 17 | 27 (expansion observed in 1 family) | — | Exon |

| Synpolydactyly | Polydactyly and syndactyly | GCG, GCT, GCA | 15 | 22-25 | — | Exon |

| CATEGORY 3 | ||||||

| Myotonic dystrophy (DM1; chromosome 19) | Muscle loss, cardiac arrhythmia, cataracts, frontal balding | CTG | 5-37 | 100 to several thousand | Either parent, but expansion to congenital form through mother | 3′ untranslated region |

| Myotonic dystrophy (DM2; chromosome 3) | Muscle loss, cardiac arrhythmia, cataracts, frontal balding | CCTG | <75 | 75-11,000 | — | 3′ untranslated region |

| Friedreich ataxia | Progressive limb ataxia, dysarthria, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, pyramidal weakness in legs | GAA | 7-2 | 200-900 or more | Autosomal recessive inheritance, so disease alleles are inherited from both parents | Intron |

| Fragile X syndrome (FRAXA) | Intellectual impairment, large ears and jaws, macroorchidism in males | CGG | 6-52 | 200-2,000 or more | Exclusively through mother | 5′ untranslated region |

| Fragile site (FRAXE) | Mild intellectual impairment | GCC | 6-35 | >200 | More often through mother | 5′ untranslated region |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 8 | Adult-onset ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus | CTG | 16-37 | 107-127 | More often through mother | 3′ untranslated region |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 | Ataxia and seizures | ATTCT | 12-16 | 800-4,500 | More often through father | Intron |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 12 | Ataxia, eye movement disorders; variable age at onset | CAG | 7-28 | 66-78 | — | 5′ untranslated region |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1 | Juvenile-onset convulsions, myoclonus, dementia | 12-bp repeat motif | 2-3 | 30-75 | Autosomal recessive inheritance, so transmitted by both parents | 5′ untranslated region |

From Jorde LB, Carey JC, Bamshad MJ, et al: Medical genetics , ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Mosby, p 82.

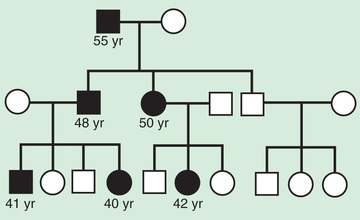

Some triplet expansions associated with other genes can cause disease through a mechanism other than decreased protein production. In Huntington disease the expansion causes the gene product to have a new, toxic effect on the neurons of the basal ganglia. For most triplet repeat disorders, there is a clinical correlation to the size of the expansion, with a greater expansion causing more severe symptoms and having an earlier age of disease onset. The observation of increasing severity of disease and early age at onset in subsequent generations is termed genetic anticipation and is a defining characteristic of many triplet repeat expansion disorders (Fig. 97.19 ).

Genetic Imprinting

The 2 copies of most autosomal genes are functionally equivalent. However, in some cases, only 1 copy of a gene is transcribed and the 2nd copy is silenced. This gene silencing is typically associated with methylation of DNA, which is an epigenetic modification, meaning it does not change the nucleotide sequence of the DNA (Fig. 97.20 ). In imprinting , gene expression depends on the parent of origin of the chromosome (see Chapter 98.8 ). Imprinting disorders result from an imbalance of active copies of a given gene, which can occur for several reasons. Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes, two distinct disorders associated with developmental impairment, are illustrative. Both can be caused by microdeletions of chromosome 15q11-12. The microdeletion in Prader-Willi syndrome is always on the paternally derived chromosome 15, whereas in Angelman syndrome it is on the maternal copy. UBE3A is the gene responsible for Angelman syndrome. The paternal copy of UBE3A is transcriptionally silenced in the brain, and the maternal copy continues to be transcribed. If an individual has a maternal deletion, an insufficient amount of UBE3A protein is produced in the brain, resulting in the neurologic deficits seen in Angelman syndrome.

Uniparental disomy (UPD) , the rare occurrence of a child inheriting both copies of a chromosome from the same parent, is another genetic mechanism that can cause Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Inheriting both chromosomes 15 from the mother is functionally the same as deletion of the paternal 15q12 and results in Prader-Willi syndrome. Approximately 30% of cases of Prader-Willi syndrome are caused by maternal UPD15, whereas paternal UPD15 accounts for only 3% of Angelman syndrome (see Chapter 98.8 ).

A mutation in an imprinted gene is another cause. Pathologic variants in UBE3A account for almost 11% of patients with Angelman syndrome and also result in familial transmission. The most uncommon cause is a mutation in the imprinting center, which results in an inability to correctly imprint UBE3A . In a woman, inability to reset the imprinting on her paternally inherited chromosome 15 imprint results in a 50% risk of passing on an incorrectly methylated copy of UBE3A to a child, who would then develop Angelman syndrome.

Besides 15q12, other imprinted regions of clinical interest include the short arm of chromosome 11, where the genes for Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and nesidioblastosis map, and the long arm of chromosome 7 with maternal UPD of 7q, which has been associated with some cases of idiopathic short stature and Russell-Silver syndrome.

Imprinting of a gene can occur during gametogenesis or early embryonic development (reprogramming). Genes can become inactive or active by various mechanisms including DNA methylation or demethylation or histone acetylation or deacetylation, with different patterns of (de)methylation noted on paternal or maternal imprintable chromosome regions. Some genes demonstrate tissue-specific imprinting (see Fig. 97.20 ). Several studies suggest a small but significantly increased incidence of imprinting disorders, specifically Beckwith-Wiedemann and Angelman syndrome, associated with assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. However, the overall incidence of these disorders in children conceived using assisted reproductive technologies is likely to be <1%.

Multifactorial and Polygenic Inheritance

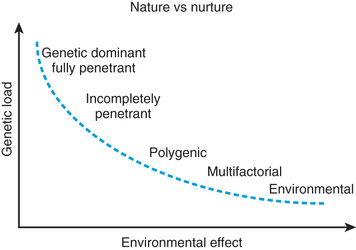

Multifactorial inheritance refers to traits that are caused by a combination of inherited, environmental, and stochastic factors (Fig. 97.21 ). Multifactorial traits differ from polygenic inheritance , which refers to traits that result from the additive effects of multiple genes. Multifactorial traits segregate within families but do not exhibit a consistent or recognizable inheritance pattern. Characteristics include the following:

- ◆ There is a similar rate of recurrence among all first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, offspring of affected child). It is unusual to find a substantial increase in risk for relatives related more distantly than second degree to the index case.

- ◆ The risk of recurrence is related to the incidence of the disease.

- ◆ Some disorders have a sex predilection, as indicated by an unequal male:female incidence. Pyloric stenosis, for example, is more common in males, whereas congenital dislocation of the hips is more common in females. With an altered sex ratio, the risk is higher for the relatives of an index case whose gender is less often affected than relatives of an index case of the more frequently affected gender. For example, the risk to the son of an affected female with infantile pyloric stenosis is 18%, compared with the 5% risk for the son of an affected male. An affected female presumably has a greater genetic susceptibility, which she can then pass on to her offspring.

- ◆ The likelihood that both identical twins will be affected with the same malformation is <100% but much greater than the chance that both members of a nonidentical twin pair will be affected. This contrasts with the pattern seen in mendelian inheritance, in which identical twins almost always share fully penetrant genetic disorders.

- ◆ The risk of recurrence is increased when multiple family members are affected. A simple example is that the risk of recurrence for unilateral cleft lip and palate is 4% for a couple with 1 affected child and increases to 9% with 2 affected children. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a multifactorial and mendelian etiology in families with multiple affected individuals.

- ◆ The risk of recurrence may be greater when the disorder is more severe. For example, an infant who has long-segment Hirschsprung disease has a greater chance of having an affected sibling than the infant who has short-segment Hirschsprung disease.

There are two types of multifactorial traits. One exhibits continuous variation, with “normal” individuals falling within a statistical range—often defined as having a value 2 standard deviations (SDs) above and/or below the mean—and “abnormals” falling outside that range. Examples include such traits as intelligence, blood pressure, height, and head circumference. For many of these traits, offspring values can be estimated based on a modified average of their parental values, with nutritional and environmental factors playing an important role.

With other multifactorial traits, the distinction between normal and abnormal is based on the presence or absence of a particular trait. Examples include pyloric stenosis, neural tube defects, congenital heart defects, and cleft lip and cleft palate. Such traits follow a threshold model (see Fig. 97.15 ). A distribution of liability because of genetic and nongenetic factors is postulated in the population. Individuals who exceed a threshold liability develop the trait, and those below the threshold do not.

The balance between genetic and environmental factors is demonstrated by neural tube defects. Genetic factors are implicated by the increased recurrence risk for parents of an affected child compared with the general population, yet the recurrence risk is about 3%, less than what would be expected if the trait was caused by a single, fully penetrant mutation. The role of nongenetic environmental factors is shown by the recurrence risk decreasing up to 87% if the mother-to-be takes 4 mg of folic acid daily starting 3 mo before conception.

Many adult-onset diseases behave as if caused by multifactorial inheritance. Diabetes, coronary artery disease, and schizophrenia are examples.