Defects in Metabolism of Carbohydrates

Priya S. Kishnani, Yuan-Tsong Chen

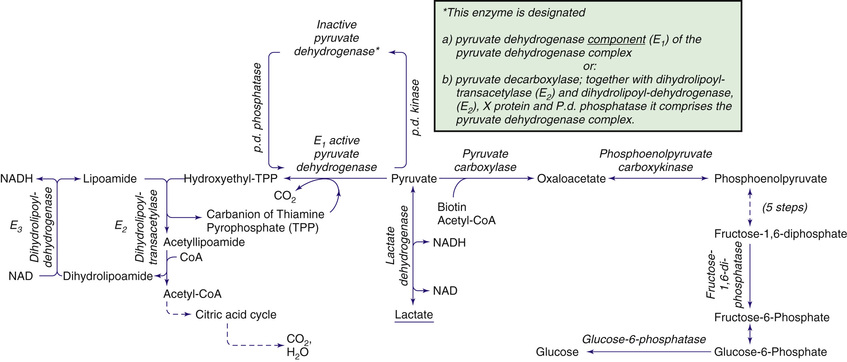

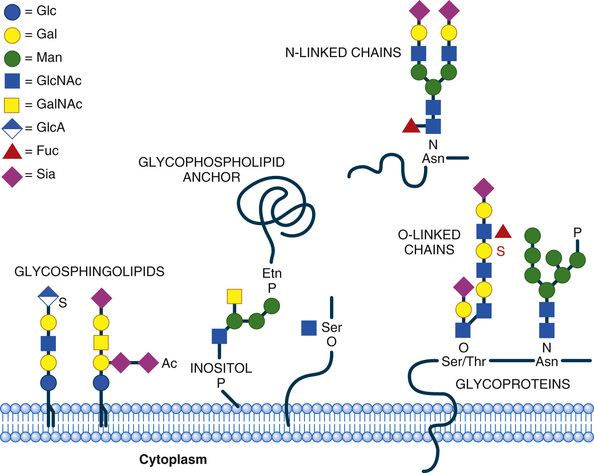

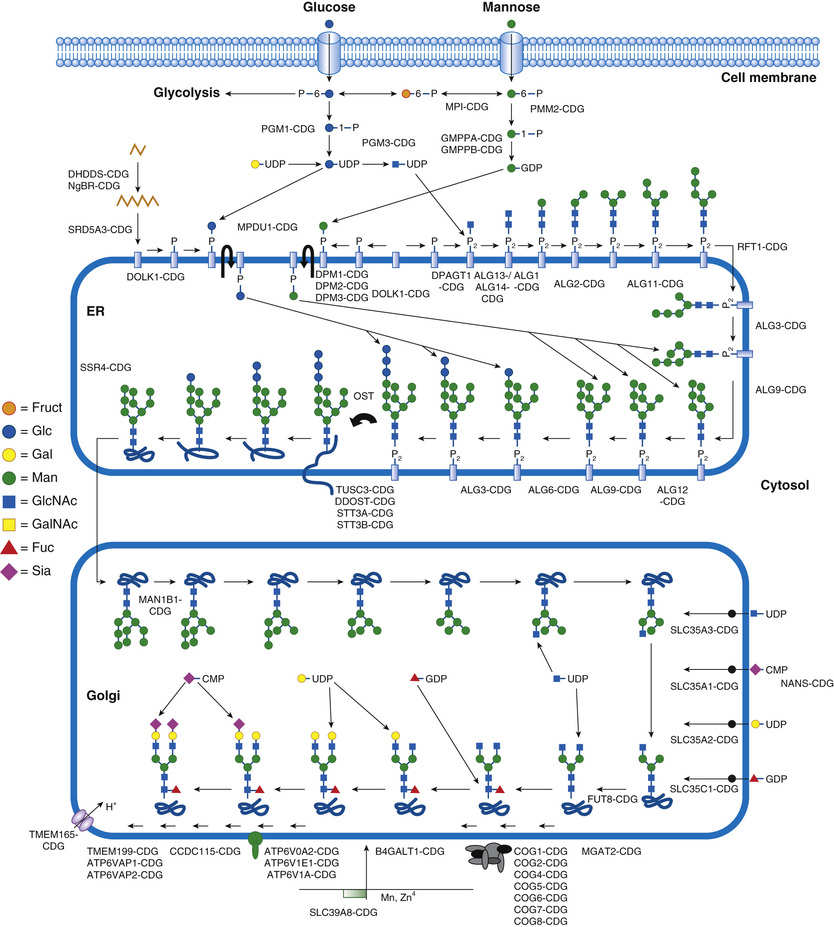

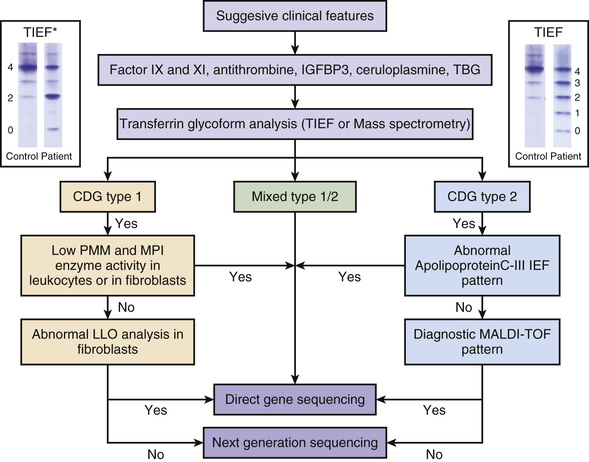

Carbohydrate synthesis and degradation provide the energy required for most metabolic processes. The important carbohydrates include 3 monosaccharides—glucose, galactose, and fructose—and a polysaccharide, glycogen. Fig. 105.1 shows the relevant biochemical pathways of these carbohydrates. Glucose is the principal substrate of energy metabolism, continuously available through dietary intake, gluconeogenesis (glucose made de novo from amino acids, primarily alanine), and glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen). Metabolism of glucose generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via glycolysis (conversion of glucose or glycogen to pyruvate), mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (conversion of pyruvate to carbon dioxide and water), or both. Dietary sources of glucose come from polysaccharides, primarily starch, and the disaccharides lactose, maltose, and sucrose. However, oral intake of glucose is intermittent and unreliable. Gluconeogenesis contributes to maintaining euglycemia (normal levels of glucose in the blood), but this process requires time. Hepatic glycogenolysis provides the rapid release of glucose, and is the most significant factor in maintaining euglycemia. Glycogen is also the primary stored energy source in muscle, providing glucose for muscle activity during exercise. Galactose and fructose are monosaccharides that provide fuel for cellular metabolism, though their role is less significant than that of glucose. Galactose is derived from lactose (galactose + glucose), which is found in milk and milk products. Galactose is an important energy source in infants, but it is first metabolized to glucose. Galactose (exogenous or endogenously synthesized from glucose) is also an important component of certain glycolipids, glycoproteins, and glycosaminoglycans. The dietary sources of fructose are sucrose (fructose + glucose, sorbitol) and fructose itself, which is found in fruits, vegetables, and honey.

Defects in glycogen metabolism typically cause an accumulation of glycogen in the tissues, thus the name glycogen storage disease (Table 105.1 ). Defects in gluconeogenesis or the glycolytic pathway, including galactose and fructose metabolism, do not result in an accumulation of glycogen (Table 105.1 ). The defects in pyruvate metabolism in the pathway of the conversion of pyruvate to carbon dioxide and water via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation are more often associated with lactic acidosis and some tissue glycogen accumulation.

Table 105.1

Features of the Disorders of Carbohydrate Metabolism

| DISORDERS | BASIC DEFECTS | CLINICAL PRESENTATION | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIVER GLYCOGENOSES | |||

| Type/Common Name | |||

| Ia/Von Gierke | Glucose-6-phosphatase | Growth retardation, hepatomegaly, hypoglycemia; elevated blood lactate, cholesterol, triglyceride, and uric acid levels |

Common, severe hypoglycemia Adulthood: hepatic adenomas and carcinoma, osteoporosis, pulmonary hypertension, and renal failure |

| Ib | Glucose-6-phosphate translocase | Same as type Ia, with additional findings of neutropenia, periodontal disease, inflammatory bowel disease | 10% of type Ia |

| IIIa/Cori or Forbes | Liver and muscle debrancher deficiency (amylo-1,6-glucosidase) |

Childhood: hepatomegaly, growth retardation, muscle weakness, hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, elevated transaminase levels Adult form: muscle atrophy and weakness, peripheral neuropathy, liver cirrhosis and failure, risk for hepatocellular carcinoma |

Common, intermediate severity of hypoglycemia Muscle weakness may progress to need for ambulation assistance such as wheelchair. |

| IIIb | Liver debrancher deficiency; normal muscle enzyme activity | Liver symptoms same as in type IIIa; no muscle symptoms | 15% of type III |

| IV/Andersen | Branching enzyme |

Childhood: failure to thrive, hypotonia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, progressive cirrhosis (death usually before 5th yr), elevated transaminase levels; a subset does not have progression of liver disease Adult form: isolated myopathy, central and peripheral nervous system involvement |

Rare neuromuscular variants exist |

| VI/Hers | Liver phosphorylase | Hepatomegaly, typically mild hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and ketosis | Often underdiagnosed, severe presentation also known |

| IX/phosphorylase kinase (PhK) deficiency | Common, X-linked, typically less severe than autosomal forms; clinical variability within and between subtypes; severe cases being recognized across different subtypes | ||

| IX (PHKA2 variant) | Liver PhK | Hypoglycemia, hyperketosis hepatomegaly, chronic liver disease, hyperlipidemia, elevated liver enzymes, growth retardation | X-linked |

| IX (PHKB variant) | Liver and muscle PhK | Hepatomegaly, growth retardation | Autosomal recessive |

| IX (PHKG2 variant) | Liver PhK | More severe than IXa; marked hepatomegaly, recurrent hypoglycemia, liver cirrhosis | Autosomal recessive |

| Glycogen synthase deficiency | Glycogen synthase | Early morning drowsiness and fatigue, fasting hypoglycemia, and ketosis, no hepatomegaly | Decreased liver glycogen store |

| XI/Fanconi-Bickel syndrome | Glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2) | Failure to thrive, rickets, hepatorenomegaly, proximal renal tubular dysfunction, impaired glucose and galactose utilization | GLUT-2 expressed in liver, kidney, pancreas, and intestine |

| MUSCLE GLYCOGENOSES | |||

| Type/Common Name | |||

| IX (PHKA1 variant) | Muscle PhK | Exercise intolerance, cramps, myalgia, myoglobinuria; no hepatomegaly | X-linked or autosomal recessive |

| II/Pompe infantile | Acid α-glucosidase (acid maltase) | Cardiomegaly, hypotonia, hepatomegaly; onset: birth to 6 mo | Common, cardiorespiratory failure leading to death by age 1-2 yr; minimal to no residual enzyme activity |

| II/Late-onset Pompe (juvenile and adult) | Acid α-glucosidase (acid maltase) | Myopathy, variable cardiomyopathy, respiratory insufficiency; onset: childhood to adulthood | Residual enzyme activity |

| Danon disease | Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, heart failure | Rare, X-linked |

| PRKAG2 deficiency | Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase γ | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Congenital fetal form is rapidly fatal; myopathy, myalgia, seizures | Autosomal dominant |

| V/McArdle | Myophosphorylase | Exercise intolerance, muscle cramps, myoglobinuria, “second wind” phenomenon | Common, male predominance |

| VII/Tarui | Phosphofructokinase | Exercise intolerance, muscle cramps, compensatory hemolytic anemia, myoglobinuria | Prevalent in Japanese and Ashkenazi Jews |

| Late-onset polyglucosan body myopathy | Glycogenin-1 | Adult-onset proximal muscle weakness, nervous system involvement uncommon | Autosomal recessive, rare |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase deficiency | Phosphoglycerate kinase | As with type V | Rare, X-linked |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase deficiency | M subunit of phosphoglycerate mutase | As with type V | Rare, majority of patients are African American |

| Lactate dehydrogenase deficiency | M subunit of lactate dehydrogenase | As with type V | Rare |

| GALACTOSE DISORDERS | |||

| Galactosemia with transferase deficiency | Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase | Vomiting, hepatomegaly, cataracts, aminoaciduria, failure to thrive | Black patients tend to have milder symptoms |

| Galactokinase deficiency | Galactokinase | Cataracts | Benign |

| Generalized uridine diphosphate galactose-4-epimerase deficiency | Uridine diphosphate galactose-4-epimerase | Similar to transferase deficiency with additional findings of hypotonia and nerve deafness | A benign variant also exists |

| FRUCTOSE DISORDERS | |||

| Essential fructosuria | Fructokinase | Urine reducing substance | Benign |

| Fructose-1-phosphate aldolase | Acute: vomiting, sweating, lethargy | ||

| Hereditary fructose intolerance | Chronic: failure to thrive, hepatic failure | Prognosis good with fructose restriction | |

| DISORDERS OF GLUCONEOGENESIS | |||

| Fructose-1,6-diphosphatase deficiency | Fructose-1,6-diphosphatase | Episodic hypoglycemia, apnea, acidosis | Good prognosis, avoid fasting |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase deficiency | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | Hypoglycemia, hepatomegaly, hypotonia, failure to thrive | Rare |

| DISORDERS OF PYRUVATE METABOLISM | |||

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex defect | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | Severe fatal neonatal to mild late onset, lactic acidosis, psychomotor retardation, failure to thrive | Most commonly caused by E1α subunit, defect X-linked |

| Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency | Pyruvate carboxylase | Same as above | Rare, autosomal recessive |

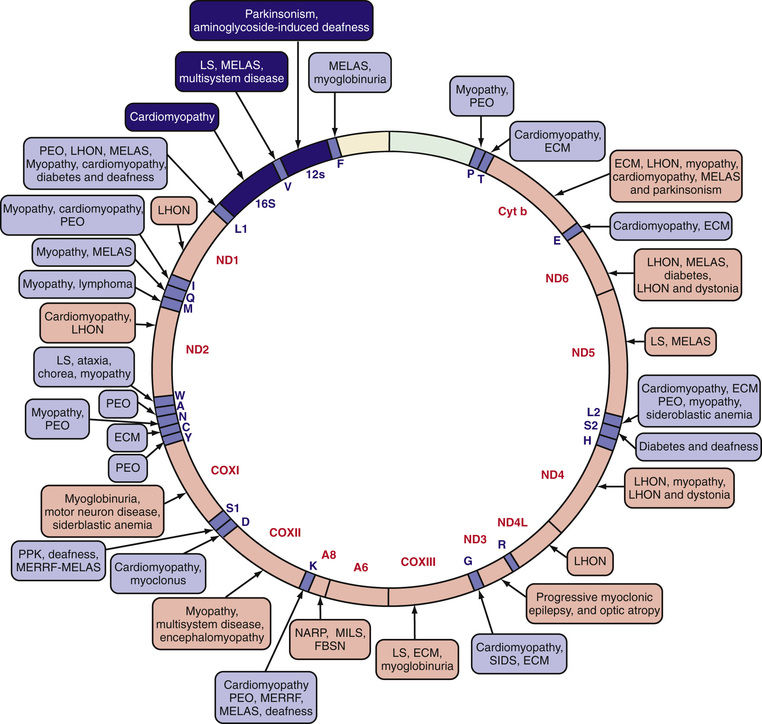

| Respiratory chain defects (oxidative phosphorylation disease) | Complexes I-V, many mitochondrial DNA mutations | Heterogeneous with multisystem involvement | Mitochondrial inheritance |

| DISORDERS IN PENTOSE METABOLISM | |||

| Pentosuria | L -Xylulose reductase | Urine-reducing substance | Benign |

| Transaldolase deficiency | Transaldolase | Liver cirrhosis and failure, cardiomyopathy | Autosomal recessive |

| Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase deficiency | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | Progressive leukoencephalopathy and peripheral neuropathy | |

Glycogen Storage Diseases

Priya S. Kishnani, Yuan-Tsong Chen

The disorders of glycogen metabolism, the glycogen storage diseases (GSDs ), result from deficiencies of various enzymes or transport proteins in the pathways of glycogen metabolism (see Fig. 105.1 ). Glycogen found in these disorders is abnormal in quantity, quality, or both. GSDs are categorized by numerical type in accordance with the chronological order in which these enzymatic defects were identified. This numerical classification is still widely used, at least up to number VII. The GSDs can also be classified by organ involvement into liver and muscle glycogenoses (see Table 105.1 ).

There are more than 12 forms of GSDs. Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency (type I), lysosomal acid α-glucosidase deficiency (type II), debrancher deficiency (type III), and liver phosphorylase kinase deficiency (type IX) are the most common of those that typically present in early childhood; myophosphorylase deficiency (type V, McArdle disease) is the most common in adolescents and adults. The cumulative frequency of all forms of GSD is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births.

Liver Glycogenoses

The GSDs that principally affect the liver include glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency (type I ), debranching enzyme deficiency (type III ), branching enzyme deficiency (type IV ), liver phosphorylase deficiency (type VI ), phosphorylase kinase deficiency (type IX , formerly GSD VIa), glycogen synthase deficiency (type 0 ), and glucose transporter-2 defect. Because hepatic carbohydrate metabolism is responsible for plasma glucose homeostasis, this group of disorders typically causes fasting hypoglycemia and hepatomegaly. Some (types III, IV, IX) can be associated with liver cirrhosis. Other organs can also be involved and may manifest as renal dysfunction in type I, myopathy (skeletal and/or cardiomyopathy) in types III and IV, as well as in some rare forms of phosphorylase kinase deficiency, and neurologic involvement in types III (peripheral nerves) and IV (diffuse central and peripheral nervous system dysfunction).

Type I Glycogen Storage Disease (Glucose-6-Phosphatase or Translocase Deficiency, Von Gierke Disease)

Type I GSD is caused by the absence or deficiency of glucose-6-phosphatase activity in the liver, kidney, and intestinal mucosa. It has 2 subtypes: type Ia , in which the defective enzyme is glucose-6-phosphatase, and type Ib , in which the defective enzyme is a translocase that transports glucose-6-phosphate across the microsomal membrane. Deficiency of the enzymes in both type Ia and type Ib lead to inadequate hepatic conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose through normal glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, resulting in fasting hypoglycemia.

Type I GSD is an autosomal recessive disorder. The gene for glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC) is located on chromosome 17q21; the gene for translocase (SLC37A4) is on chromosome 11q23. Common pathogenic variants have been identified. Carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis are possible with DNA-based methodologies.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with type I GSD may present in the neonatal period with hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis but more often present at 3-4 mo of age with hepatomegaly, hypoglycemic seizures, or both. Affected children often have a doll-like face with fat cheeks, relatively thin extremities, short stature, and a protuberant abdomen that is a consequence of massive hepatomegaly. The kidneys are also enlarged, whereas the spleen and heart are not involved.

The biochemical characteristics of type I GSD are hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hyperuricemia, and hyperlipidemia. Hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis can develop after a short fast. Hyperuricemia is present in young children; it rarely progresses to symptomatic gout before puberty. Despite marked hepatomegaly, the liver transaminase levels are usually normal or only slightly elevated. Intermittent diarrhea may occur in GSD I. In patients with GSD Ib, the loss of mucosal barrier function as a result of inflammation, which is likely related to the disturbed neutrophil function, seems to be the main cause of diarrhea. Easy bruising and epistaxis are common and are associated with a prolonged bleeding time as a result of impaired platelet aggregation and adhesion.

The plasma may be “milky” in appearance due to strikingly elevated triglyceride levels. Cholesterol and phospholipids are also elevated, but less prominently. The lipid abnormality resembles type IV hyperlipidemia and is characterized by increased levels of very-low-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and a unique apolipoprotein profile consisting of increased levels of apolipoproteins B, C, and E, with relatively normal or reduced levels of apolipoproteins A and D. The histologic appearance of the liver is characterized by a universal distention of hepatocytes by glycogen and fat. The lipid vacuoles are particularly large and prominent. There is no associated liver fibrosis.

Although type I GSD affects mainly the liver, multiple organ systems are involved. Delayed puberty is often seen. Females can have ultrasound findings consistent with polycystic ovaries even though other features of polycystic ovary syndrome (acne, hirsutism) are not seen. Nonetheless, fertility appears to be normal, as evidenced in several reports of successful pregnancy in women with GSD I. Increased bleeding during menstrual cycles, including life-threatening menorrhagia, has been reported and could be related to the impaired platelet aggregation. Symptoms of gout usually start around puberty from long-term hyperuricemia. There is an increased risk of pancreatitis, secondary to the lipid abnormalities. The dyslipidemia, together with elevated erythrocyte aggregation, could predispose these patients to atherosclerosis, but premature atherosclerosis has not yet been clearly documented except for rare cases. Impaired platelet aggregation and increased antioxidative defense to prevent lipid peroxidation may function as a protective mechanism to help reduce the risk of atherosclerosis. Frequent fractures and radiographic evidence of osteopenia are common; bone mineral content is reduced, even in prepubertal patients.

By the 2nd or 3rd decade of life, some patients with type I GSD develop hepatic adenomas that can hemorrhage and turn malignant in some cases. Pulmonary hypertension has been seen in some long-term survivors of the disease. Iron-refractory anemia and an increased prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity are also being recognized.

Renal disease is another late complication, and most patients with type I GSD >20 yr of age have proteinuria. Many also have hypertension, renal stones, nephrocalcinosis, and altered creatinine clearance. Glomerular hyperfiltration, increased renal plasma flow, and microalbuminuria are often found in the early stages of renal dysfunction and can occur before the onset of proteinuria. In younger patients, hyperfiltration and hyperperfusion may be the only signs of renal abnormalities. With the advancement of renal disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis become evident. In some patients, renal function has deteriorated and progressed to failure, requiring dialysis and transplantation. Other renal abnormalities include amyloidosis, a Fanconi-like syndrome, hypocitraturia, hypercalciuria, and a distal renal tubular acidification defect.

Patients with GSD Ib can have additional features of recurrent bacterial infections from neutropenia and impaired neutrophil function. Oral involvement including recurrent mucosal ulceration, gingivitis, and rapidly progressive periodontal disease may occur in type Ib. Intestinal mucosa ulceration culminating in GSD enterocolitis is also common. Type 1b is also associated with a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–like picture involving the colon that may be associated with neutropenia and/or neutrophil dysfunction; it may resemble ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation and laboratory findings of hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hyperuricemia, and hyperlipidemia lead to a suspected diagnosis of type I GSD. Neutropenia is noted in GSD Ib patients, typically before 1 yr of age. Neutropenia has also been noted in some patients with GSD Ia, especially those with the p.G188A variant. Administration of glucagon or epinephrine leads to a negligible increase, if any, in blood glucose levels, but the lactate level rises significantly. Before the availability of genetic testing, a definitive diagnosis required a liver biopsy. Gene-based variant analysis by single-gene sequencing or gene panels provides a noninvasive way to diagnose most patients with GSD types Ia and Ib.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on maintaining normal blood glucose levels and is achieved by continuous nasogastric (NG) infusion of glucose or oral administration of uncooked cornstarch. In infancy, overnight NG drip feeding may be needed to maintain normoglycemia. NG feedings can consist of an elemental enteral formula or only glucose or a glucose polymer to provide sufficient glucose to maintain euglycemia. During the day, frequent feedings with high-carbohydrate content are typically sufficient.

Uncooked cornstarch acts as a slow-release form of glucose and can be introduced at a dose of 1.6 g/kg every 4 hr for children <2 yr of age. The response of young children is variable. For older children, the cornstarch regimen can be changed to every 6 hr at a dose of 1.6-2.5 g/kg body weight and can be given orally as a liquid. Newer starch products, such as extended-release waxy maize starch, are thought to be longer acting, better tolerated, and more palatable. Medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) supplementation improves metabolic control, leading to improved growth in children. Since fructose and galactose cannot be converted directly to glucose in GSD type I, these sugars should be restricted in the diet. Sucrose (table sugar, cane sugar, other ingredients), fructose (fruit, juice, high-fructose corn syrup), lactose (dairy foods), and sorbitol should be avoided or limited. As a result of these dietary restrictions, vitamins and minerals such as calcium and vitamin D may be deficient, and supplementation is required to prevent nutritional deficiencies.

Dietary therapy improves hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, and renal function, slowing the development of renal failure. This therapy fails, however, to normalize blood uric acid and lipid levels completely in some individuals, despite good metabolic control, especially after puberty. The control of hyperuricemia can be further augmented by the use of allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor. The hyperlipidemia can be reduced with lipid-lowering drugs such as β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors and fibrate (see Chapter 104 ). Microalbuminuria , an early indicator of renal dysfunction in type I disease, is treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Citrate supplements can be beneficial for patients with hypocitraturia by preventing or ameliorating nephrocalcinosis and development of urinary calculi. Thiazide diuretics increase renal reabsorption of filtered calcium and decrease urinary calcium excretion, thereby preventing hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis. Growth hormone (GH) should be used with extreme caution and limited to only those with a documented GH deficiency. Even in those patients, there should be close monitoring of metabolic parameters and for the presence of adenomas.

In patients with type Ib GSD, granulocyte and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors are successful in correcting the neutropenia, decreasing the number and severity of bacterial infections, and improving the chronic IBD. The minimum effective dose should be used because side effects are noted on these agents, including splenomegaly, hypersplenism, and bone pain. Bone marrow transplantation has been reported to correct the neutropenia of type Ib GSD.

Orthotopic liver transplantation is a potential cure of type I GSD, especially for patients with liver malignancy, multiple liver adenomas, metabolic derangements refractory to medical management, and liver failure. However, this should be considered as a last resort because of the inherent short- and long-term complications. Large adenomas (>2 cm) that are rapidly increasing in size and/or number may necessitate partial hepatic resection. Smaller adenomas (<2 cm) may be treated with percutaneous ethanol injection or transcatheter arterial embolization. Recurrence of liver adenomas is a challenge and may potentiate malignant transformation in these patients, ultimately requiring a liver transplant.

Before any surgical procedure, the bleeding status must be evaluated and good metabolic control established. Prolonged bleeding times can be normalized by the use of intensive intravenous (IV) glucose infusion for 24-48 hr before surgery. DDAVP (1-deamino-8-D -arginine vasopressin) can reduce bleeding complications, but it should be used with caution because of the risk of fluid overload and hyponatremia when administered as an IV infusion. Lactated Ringer solution should be avoided because it contains lactate and no glucose. Glucose levels should be maintained in the normal range throughout surgery with the use of 10% dextrose. Overall, metabolic control is assessed by growth, improvement, and correction of the metabolic abnormalities, such as elevated lactate, glucose, triglyceride, cholesterol, and uric acid levels.

Prognosis

Previously, type I GSD was associated with a high mortality at a young age, and even for those who survived, the prognosis was guarded. Inadequate metabolic control during childhood can lead to long-term complications in adults. Clinical outcomes have improved dramatically with early diagnosis and effective treatment. However, serious complications such as renal disease and formation of hepatic adenomas with potential risk for malignant transformation persist. The ability to identify transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver adenomas remains a challenge: α-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels often remain normal in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Type III Glycogen Storage Disease (Debrancher Deficiency, Limit Dextrinosis)

Type III GSD is caused by deficient activity of the glycogen debranching enzyme . Debranching enzyme, together with phosphorylase, is responsible for complete degradation of glycogen. When debranching enzyme is defective, glycogen breakdown is incomplete, resulting in the accumulation of an abnormal glycogen with short outer-branch chains, which resemble limit dextrin. Symptoms of glycogen debranching enzyme deficiency include hepatomegaly, hypoglycemia, short stature, variable skeletal myopathy, and variable cardiomyopathy. GSD type IIIa usually involves both liver and muscle, whereas in type IIIb , seen in approximately 15% of patients, the disease appears to involve only liver.

Type III GSD is an autosomal recessive disease that has been reported in many different ethnic groups. The frequency is relatively high in Sephardic Jews from North Africa, inhabitants of the Faroe Islands, and in Inuits. The gene for debranching enzyme (AGL) is located on chromosome 1p21. More than 130 different pathogenic variants have been identified; 2 pathogenic variants in exon 3, c.18_19delGA (previously described as c.17_18delAG) and p.Gln6X, are specifically associated with glycogenosis IIIb. Carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis are possible using DNA-based methodologies.

Clinical Manifestations

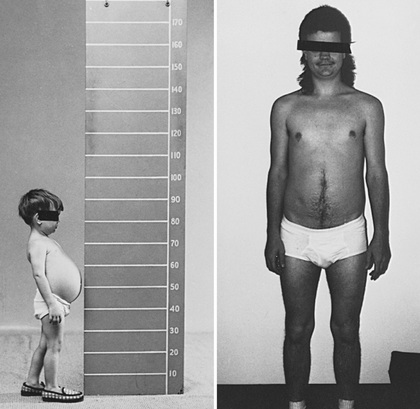

In infancy and childhood, GSD type III may be indistinguishable from type I GSD because of overlapping features such as hepatomegaly, hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and growth retardation (Fig. 105.2 ). Splenomegaly may be present, but the kidneys are typically not affected. Hepatomegaly in most patients with type III GSD improves with age; however, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis progressing to liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are noted in many in late adulthood. Hepatic adenomas occur less often in individuals with GSD III than those with GSD I. The relationship between hepatic adenomas and malignancy in GSD III remains unclear. AFP and CEA levels are not good predictors of the presence of hepatocellular adenomas or malignant transformation. A single case of malignant transformation at the site of adenomas has been noted.

In patients with GSD type IIIa, the muscle weakness is slowly progressive and associated with wasting. The weakness is less remarkable in childhood but can become severe after the 3rd or 4th decade of life. Low bone mineral density in patients with GSD III put them at an increased risk of potential fractures. Myopathy does not follow any particular pattern of involvement; both proximal and distal muscles are involved. Electromyography reveals a widespread myopathy; nerve conduction studies are often abnormal.

Although overt cardiac dysfunction is rare, ventricular hypertrophy is a frequent finding. Cardiac pathology has shown diffuse involvement of various cardiac structures, including vacuolation of myocytes, atrioventricular conduction, and hyperplasia of smooth muscles. Life-threatening arrhythmia and the need for heart transplant have been reported in some GSD III patients. Hepatic symptoms in some patients may be so mild that the diagnosis is not made until adulthood, when the patients show symptoms and signs of neuromuscular disease.

The initial diagnosis has been confused with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (see Chapter 631.1 ). Polycystic ovaries are noted; some patients can develop hirsutism, irregular menstrual cycles, and other features of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Fertility does not appear to be affected; successful pregnancies have been reported.

Hypoglycemia and hyperlipidemia are common. In contrast to type I GSD, elevation of liver transaminase levels and fasting ketosis are prominent, but blood lactate and uric acid concentrations are usually normal. Glucagon administration 2 hr after a carbohydrate meal provokes a normal increase in blood glucose; after an overnight fast, however, glucagon may provoke no change in blood glucose level. Serum creatine kinase levels can be useful to identify patients with muscle involvement, although normal levels do not rule out muscle enzyme deficiency.

Diagnosis

The histologic appearance of the liver is characterized by a universal distention of hepatocytes by glycogen and the presence of fibrous septa. The fibrosis and the paucity of fat distinguish type III glycogenosis from type I. The fibrosis, which ranges from minimal periportal fibrosis to micronodular cirrhosis, appears in most cases to be nonprogressive. Overt cirrhosis has been seen in some patients with GSD III.

Patients with myopathy and liver symptoms have a generalized enzyme defect (type IIIa). The deficient enzyme activity can be demonstrated not only in liver and muscle, but also in other tissues such as heart, erythrocytes, and cultured fibroblasts. Patients with hepatic symptoms without clinical or laboratory evidence of myopathy have debranching enzyme deficiency only in the liver, with enzyme activity retained in the muscle (type IIIb). Before the availability of genetic testing, a definitive diagnosis required enzyme assay in liver, muscle, or both. Gene sequencing now allows for diagnosis and subtype assignment in the majority of patients.

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment of GSD III is dietary management, as in GSD I, although it is less demanding. Patients do not need to restrict dietary intake of fructose and galactose, although simple sugars should be avoided to prevent sudden spikes in blood glucose levels. Hypoglycemia is treated with small, frequent meals high in complex carbohydrates, such as cornstarch supplements or nocturnal gastric drip feedings. Additionally, a high-protein diet during the daytime as well as overnight protein enteral infusion is effective in preventing hypoglycemia. The exogenous protein can be used as a substrate for gluconeogenesis which helps to meet energy needs and prevent endogenous protein breakdown. Protein in the diet also reduces the overall starch requirement. Overtreatment with cornstarch should be avoided as it can result in excessive glycogen buildup, which is detrimental and can lead to excessive weight gain. MCT supplementation is being considered as an alternative source of energy. There is no satisfactory treatment for the progressive myopathy other than recommending a high-protein diet and a submaximal exercise program. Close monitoring with abdominal MRI is needed to detect progression of liver fibrosis to cirrhosis and further to HCC. Liver transplantation has been performed in GSD III patients with progressive cirrhosis and/or HCC. There are reports of cardiac transplant in GSD III patients with end stage cardiac disease.

Type IV Glycogen Storage Disease (Branching Enzyme Deficiency, Amylopectinosis, Polyglucosan Disease, or Andersen Disease)

Type IV GSD is caused by the deficiency of branching enzyme activity, which results in the accumulation of an abnormal glycogen with poor solubility. The disease is also known as amylopectinosis because the abnormal glycogen has fewer branch points, more α 1-4 linked glucose units, and longer outer chains, resulting in a structure resembling amylopectin. Accumulation of polyglucosan, which is positive on periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and partially resistant to diastase digestion, is seen in all tissues of patients, but to different degrees.

Type IV GSD is an autosomal recessive disorder. The glycogen branching enzyme (GBE) gene is located on chromosome 3p21. More than 20 pathogenic variants responsible for type IV GSD have been identified, and their characterization in individual patients can be useful in predicting clinical outcome. The nearly complete absence of GBE activity with null variants has been associated with perinatal death and fatal neonatal hypotonia. Residual GBE enzyme activity >5% and presence of at least 1 missense variant are associated with a nonlethal hepatic cirrhosis phenotype and, in some situations, a lack of progressive liver disease.

Clinical Manifestations

There is a high degree of clinical variability associated with type IV GSD. The most common and classic form is characterized by progressive cirrhosis of the liver and manifests in the 1st 18 mo of life as hepatosplenomegaly and failure to thrive. Cirrhosis may present with portal hypertension, ascites, and esophageal varices and may progress to liver failure, usually leading to death by 5 yr of age. Rare patients survive without progression of liver disease; they have a milder hepatic form and do not require a liver transplant. Extrahepatic involvement in some patients with GSD IV consists of musculoskeletal involvement, particularly cardiac and skeletal muscles, as well as central nervous system (CNS) involvement.

A neuromuscular form of type IV GSD has been reported, with 4 main variants recognized based on age at presentation. The perinatal form is characterized by a fetal akinesia deformation sequence (FADS) and death in the perinatal period. The congenital form presents at birth with severe hypotonia, muscle atrophy, and neuronal involvement, with death in the neonatal period; some patients have cardiomyopathy. The childhood form presents primarily with myopathy or cardiomyopathy. The adult form, adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD), presents as an isolated myopathy or with diffuse CNS and peripheral nervous system dysfunction, accompanied by accumulation of polyglucosan material in the nervous system. Symptoms of neuronal involvement include peripheral neuropathy, neurogenic bladder, and leukodystrophy, as well as mild cognitive decline in some patients. For APBD, a leukocyte or nerve biopsy is needed to establish the diagnosis because branching enzyme deficiency is limited to those tissues.

Diagnosis

Deposition of amylopectin-like materials can be demonstrated in liver, heart, muscle, skin, intestine, brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerve in type IV GSD. Liver histology shows micronodular cirrhosis and faintly stained basophilic inclusions in the hepatocytes. The inclusions are composed of coarsely clumped, stored material that is PAS positive and partially resistant to diastase digestion. Electron microscopy (EM) shows, in addition to the conventional α and β glycogen particles, accumulation of the fibrillar aggregations that are typical of amylopectin. The distinct staining properties of the cytoplasmic inclusions, as well as EM findings, could be diagnostic. However, polysaccharides with histologic features reminiscent of type IV disease, but without enzymatic correlation, have been observed. The definitive diagnosis rests on the demonstration of the deficient branching enzyme activity in liver, muscle, cultured skin fibroblasts, or leukocytes, or on the identification of pathogenic variants in the GBE gene. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by measuring enzyme activity in cultured amniocytes, chorionic villi, or DNA-based methodologies.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for type IV GSD. Nervous system involvement, such as gait problems and bladder involvement, requires supportive, symptomatic management. Unlike patients with the other liver GSDs (I, III, VI, IX), those with GSD IV do not have hypoglycemia, which is only seen when there is overt liver cirrhosis. Liver transplantation has been performed for patients with progressive liver disease, but patients must be carefully selected as this is a multisystem disease, and in some patients, extrahepatic involvement may manifest after transplant. The long-term success of liver transplantation is unknown. Individuals with significant diffuse reticuloendothelial involvement may have greater risk for morbidity and mortality, which may impact the success rate for liver transplant.

Type VI Glycogen Storage Disease (Liver Phosphorylase Deficiency, Hers Disease)

Type VI GSD is caused by deficiency of liver glycogen phosphorylase . Relatively few patients are documented, likely because of underreporting of this disease. Patients usually present with hepatomegaly and growth retardation in early childhood. Hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and hyperketosis are of variable severity. Ketotic hypoglycemia may present after overnight or prolonged fasting. Lactic acid and uric acid levels are normal. Type VI GSD presents within a broad spectrum of involvement, some with a more severe clinical presentation. Patients with severe hepatomegaly, recurrent severe hypoglycemia, hyperketosis, and postprandial lactic acidosis have been reported. Focal nodular hyperplasia of liver and hepatocellular adenoma with malignant transformation into carcinoma is reported in some patients. While cardiac muscle was thought to be unaffected, recently mild cardiomyopathy has been reported in a patient with GSD VI.

Treatment is symptomatic and aims to prevent hypoglycemia while ensuring adequate nutrition. A high-carbohydrate, high-protein diet and frequent feeding are effective in preventing hypoglycemia. Blood glucose and ketones should be monitored routinely, especially during periods of increased activity/illness. Long-term follow-up of these patients is needed to expand the understanding of the natural history of this disorder.

GSD VI is an autosomal recessive disease. Diagnosis can be confirmed through molecular testing of the liver phosphorylase gene (PYGL), which is found on chromosome 14q21-22 and has 20 exons. Many pathogenic variants are known in this gene; a splice-site variant in intron 13 has been identified in the Mennonite population. A liver biopsy showing elevated glycogen content and decreased hepatic phosphorylase enzyme activity can also be used to make a diagnosis. However, with the availability of DNA analysis and next-generation sequencing panels, liver biopsies are considered unnecessary.

Type IX Glycogen Storage Disease (Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency)

Type IX GSD represents a heterogeneous group of glycogenoses. It results from deficiency of the enzyme phosphorylase kinase (PhK), which is involved in the rate-limiting step of glycogenolysis. This enzyme has 4 subunits (α, β, γ, δ), each encoded by different genes on different chromosomes and differentially expressed in various tissues. Pathogenic variants in the PHKA1 gene cause muscle PhK deficiency; pathogenic variants in the PHKA2 and PHKG2 genes cause liver PhK deficiency; pathogenic variants in the PHKB gene cause PhK deficiency in liver and muscle. Pathogenic variants in the PHKG1 gene have not been identified. Defects in subunits α, β, and γ are responsible for liver presentation.

Clinical manifestations of liver PhK deficiency are usually recognizable within the 1st 2 yr of life and include short stature and abdominal distention from moderate to marked hepatomegaly. The clinical severity of liver PhK deficiency varies considerably. Hyperketotic hypoglycemia, if present, can be mild but may be severe in some cases. Ketosis may occur even when glucose levels are normal. Some children may have mild delays in gross motor development and hypotonia. It is becoming increasingly clear that GSD IX is not a benign condition. Severe phenotypes are reported, with liver fibrosis progressing to cirrhosis and HCC, particularly in patients with PHKG2 variants. Progressive splenomegaly and portal hypertension are reported secondary to cirrhosis. Mild cardiomyopathy has been reported in a patient with GSD IX (PHKB variant). Cognitive and speech delays have been reported in a few individuals, but it is not clear whether these delays are caused by PhK deficiency or coincidental. Renal tubular acidosis has been reported in rare cases. Unlike in GSD I, lactic acidosis, bleeding tendency, and loose bowel movements are not characteristic. Although growth is retarded during childhood, normal height and complete sexual development are eventually achieved. As with debrancher deficiency, abdominal distention and hepatomegaly usually decrease with age and may disappear by adolescence. Most adults with liver PhK deficiency are asymptomatic, although further long-term studies are needed to fully assess the impact of this disorder in adults.

Phenotypic variability within each subtype is being uncovered with the availability of molecular testing. The incidence of all subtypes of PhK deficiency is approximately 1 : 100,000 live births.

X-Linked Liver Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency (From PHKA2 Variants)

X-linked liver PhK deficiency is one of the most common forms of liver glycogenosis in males. In addition to liver, enzyme activity can also be deficient in erythrocytes, leukocytes, and fibroblasts; it is normal in muscle. Typically, a 1-5 yr old boy presents with growth retardation, an incidental finding of hepatomegaly, and a slight delay in motor development. Cholesterol, triglycerides, and liver enzymes are mildly elevated. Ketosis may occur after fasting. Lactate and uric acid levels are normal. Hypoglycemia is typically mild, if present, but can be severe. The response in blood glucose to glucagon is normal. Hepatomegaly and abnormal blood chemistries gradually improve and can normalize with age. Most adults achieve a normal final height and are usually asymptomatic despite a persistent PhK deficiency. It is increasingly being recognized that this disorder is not benign as previously thought, and there are patients with severe disease and long-term hepatic sequelae. In rare cases, liver fibrosis can occur and progress to cirrhosis.

Liver histology shows glycogen-distended hepatocytes, steatosis, and potentially mild periportal fibrosis. The accumulated glycogen (β particles, rosette form) has a frayed or burst appearance and is less compact than the glycogen seen in type I or III GSD. Fibrous septal formation and low-grade inflammatory changes may be seen.

The gene for the common liver isoform of the PhK α subunit, PHKA2, is located on the X chromosome (αL at Xp22.2). Mutations in the PHKA2 gene account for 75% of all PhK cases. X-linked liver PhK deficiency is further subdivided into 2 biochemical subtypes: XLG1, with measurable deficiency of PhK activity in both blood cells and liver, and XLG2, with normal in vitro PhK activity in blood cells and variable activity in liver. It is suspected that XLG2 may be caused by missense variants that affect enzyme regulation, whereas nonsense variants affecting the amount of protein result in XLG1. Female carriers are unaffected.

Autosomal Liver and Muscle Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency (From PHKB Variants)

PhK deficiency in liver and blood cells with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance has been reported. Similar to the X-linked form, chief symptoms in early childhood include hepatomegaly and growth retardation. Some patients also exhibit muscle hypotonia. In a few cases where enzyme activity has been measured, reduced PhK activity has been demonstrated in muscle. Mutations are found in PHKB (chromosome 16q12-q13), which encodes the β subunit, and result in liver and muscle PhK deficiency. Several nonsense variants, a single-base insertion, a splice-site mutation, and a large intragenic mutation have been identified. In addition, a missense variant was discovered in an atypical patient with normal blood cell PhK activity.

Autosomal Liver Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency (From PHKG2 Variants)

This form of PhK deficiency is caused by pathogenic variants in the testis/liver isoform (TL) of the γ subunit gene (PHKG2). In contrast to X-linked PhK deficiency, patients with variants in PHKG2 typically have more severe phenotypes, with recurrent hypoglycemia, prominent hepatomegaly, significant liver fibrosis, and progressive cirrhosis. Liver involvement may present with cholestasis, bile duct proliferation, esophageal varices, and splenomegaly. Other reported presentations include delayed motor milestones, muscle weakness, and renal tubular damage. The spectrum of involvement continues to evolve as more cases are recognized. PHKG2 maps to chromosome 16p12.1-p11.2; many pathogenic variants are known for this gene.

Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency Limited to Heart

These patients have been reported with cardiomyopathy in infancy and rapidly progress to heart failure and death. Recent studies have shown that this is not a case of cardiac-specific primary PhK deficiency as suspected previously, but rather linked to the γ2 subunit of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase (see later). The γ2 subunit is encoded by the PRKAG2 gene.

Diagnosis

PhK deficiency may be diagnosed by demonstration of the enzymatic defect in affected tissues. PhK can be measured in leukocytes and erythrocytes, but because the enzyme has many isozymes, the diagnosis can be easily missed without studies of liver, muscle, or heart. Individuals with liver PhK deficiency also usually have elevated transaminases, mildly elevated triglycerides and cholesterol, normal uric acid and lactic acid concentrations, and normal glucagon responses. Gene sequencing is used for diagnostic confirmation and subtyping of GSD IX.

The PHKA2 gene encoding the α subunit is most frequently involved, followed by the PHKB gene encoding the β subunit. Variants in the PHKG2 gene underlying γ-subunit deficiency are typically associated with severe liver involvement with recurrent hypoglycemia and liver fibrosis.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment for liver PhK deficiency is symptomatic. It includes a diet high in complex carbohydrates and proteins and small, frequent feedings to prevent hypoglycemia. Cornstarch can be administered with symptom-dependent dosage and timing (0.6-2.5 g/kg every 6 hr). Oral intake of glucose, if tolerated, should be used to treat hypoglycemia. If not, IV glucose should be given.

Prognosis for the X-linked and certain autosomal forms is typically good; however, long term complications are being recognized. Patients with mutations in the γ subunit typically have a more severe clinical course with progressive liver disease. Liver involvement needs to be monitored in all patients with GSD IX by periodic imaging (abdominal ultrasound or MRI every 6-12 mo) and serial hepatic function tests.

Liver Glycogen Synthase Deficiency

Liver glycogen synthase deficiency type 0 (GSD 0 ) is caused by deficiency of hepatic glycogen synthase (GYS2) activity, leading to a marked decrease of glycogen stored in the liver. The gene GYS2 is located at 12p12.2. Several pathogenic variants have been identified in patients with GSD 0. The disease appears to be rare in humans, and in the true sense, this is not a type of GSD because the deficiency of the enzyme leads to decreased glycogen stores. Patients present in infancy with early-morning (prebreakfast) drowsiness, pallor, emesis, and fatigue and sometimes convulsions associated with hypoglycemia and hyperketonemia. Blood lactate and alanine levels are low, and there is no hyperlipidemia or hepatomegaly. Prolonged hyperglycemia , glycosuria, lactic acidosis, and hyperalaninemia, with normal insulin levels after administration of glucose or a meal, suggest a deficiency of glycogen synthase. Definitive diagnosis may be by a liver biopsy to measure the enzyme activity or identification of pathogenic variants in GYS2 .

Treatment consists of frequent meals, rich in protein and nighttime supplementation with uncooked cornstarch to prevent hypoglycemia and hyperketonemia. Most children with GSD 0 are cognitively and developmentally normal. Short stature and osteopenia are common features. The prognosis seems good for patients who survive to adulthood, including resolution of hypoglycemia, except during pregnancy.

Hepatic Glycogenosis With Renal Fanconi Syndrome (Fanconi-Bickel Syndrome)

Fanconi-Bickel Syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder is caused by defects in the facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2), which transports glucose in and out of hepatocytes, pancreatic β cells, and the basolateral membranes of intestinal and renal epithelial cells. The disease is characterized by proximal renal tubular dysfunction, impaired glucose and galactose utilization, and accumulation of glycogen in liver and kidney.

The affected child typically presents in the 1st yr of life with failure to thrive, rickets, and a protuberant abdomen from hepatomegaly and nephromegaly. The disease may be confused with GSD I because a Fanconi-like syndrome can also develop in type I patients. Adults typically present with short stature, dwarfism, and excess fat in the abdomen and shoulders. Patients are more susceptible to fractures because of early-onset generalized osteopenia. In addition, intestinal malabsorption and diarrhea may occur.

Laboratory findings include glucosuria, phosphaturia, generalized aminoaciduria, bicarbonate wasting, hypophosphatemia, increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels, and radiologic findings of rickets. Mild fasting hypoglycemia and hyperlipidemia may be present. Liver transaminase, plasma lactate, and uric acid levels are usually normal. Oral galactose or glucose tolerance tests show intolerance, which could be explained by the functional loss of GLUT-2 preventing liver uptake of these sugars. Tissue biopsy results show marked accumulation of glycogen in hepatocytes and proximal renal tubular cells, presumably from the altered glucose transport out of these organs. Diffuse glomerular mesangial expansion along with glomerular hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria similar to nephropathy in GSD Ia and diabetes have been reported.

This condition is rare, and 70% of patients with Fanconi-Bickel syndrome have consanguineous parents. Most patients have homozygous pathogenic variants; some patients are compound heterozygotes. The majority of variants detected thus far predict a premature termination of translation. The resulting loss of the C-terminal end of the GLUT-2 protein predicts a nonfunctioning glucose transporter with an inward-facing substrate-binding site.

There is no specific treatment. Symptom-dependent treatment with phosphate and bicarbonate can result in growth improvement. Growth may also improve with symptomatic replacement of water, electrolytes, and vitamin D; restriction of galactose intake; and a diet similar to that used for diabetes mellitus, with small, frequent meals and adequate caloric intake.

Muscle Glycogenoses

The role of glycogen in muscle is to provide substrates for the generation of ATP for muscle contraction. The muscle GSDs are broadly divided into 2 groups. The first group is characterized by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, progressive skeletal muscle weakness and atrophy, or both, and includes deficiencies of acid α-glucosidase , a lysosomal glycogen-degrading enzyme (type II GSD), lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2 ), and AMP-activated protein kinase γ2 (PRKAG2 ). The 2nd group comprises muscle energy disorders characterized by muscle pain, exercise intolerance, myoglobinuria, and susceptibility to fatigue. This group includes myophosphorylase deficiency (McArdle disease, type V GSD) and deficiencies of phosphofructokinase (type VII ), phosphoglycerate kinase, phosphoglycerate mutase, lactate dehydrogenase, and muscle-specific phosphorylase kinase. Some of these latter enzyme deficiencies can also be associated with compensated hemolysis , suggesting a more generalized defect in glucose metabolism.

Type II Glycogen Storage Disease (Lysosomal Acid α-1,4-Glucosidase Deficiency, Pompe Disease)

Pompe disease, also referred to as GSD type II or acid maltase deficiency , is caused by a deficiency of acid α-1,4-glucosidase (acid maltase), an enzyme responsible for the degradation of glycogen in lysosomes. This enzyme defect results in lysosomal glycogen accumulation in multiple tissues and cell types, predominantly affecting cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. In Pompe disease, glycogen typically accumulates within lysosomes, as opposed to its accumulation in cytoplasm in the other glycogenoses. However, as the disease progresses, lysosomal rupture and leakage lead to the presence of cytoplasmic glycogen as well.

Pompe disease is an autosomal recessive disorder. The incidence was thought to be approximately 1 in 40,000 live births in Caucasians and 1 in 18,000 live births in Han Chinese. Newborn screening for Pompe disease in the United States suggests that the prevalence is much higher than previously thought (between 1 in 9,132 and 1 in 24,188). The gene for acid α-glucosidase (GAA) is on chromosome 17q25.2. More than 500 pathogenic variants have been identified that could be helpful in delineating the phenotypes. A splice-site variant (IVS1-13T→G; c.-32-13T>G) is commonly seen in late-onset Caucasian patients.

Clinical Manifestations

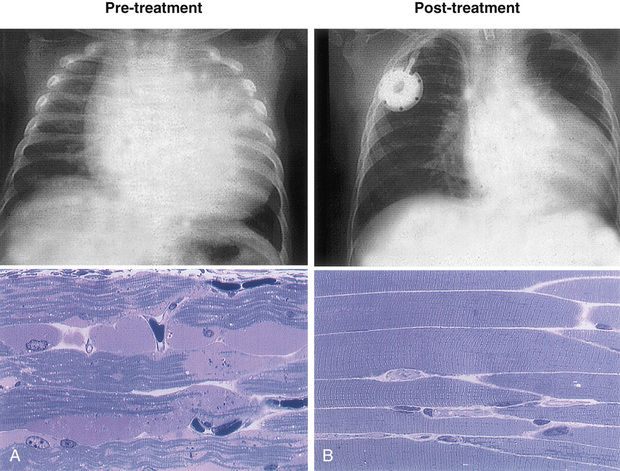

Pompe disease is broadly classified into infantile and late-onset forms. Infantile Pompe disease (IPD) is uniformly lethal without enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with alglucosidase alfa. Affected infants present in the 1st day to weeks of life with hypotonia, generalized muscle weakness with a floppy infant appearance, neuropathic bulbar weakness, feeding difficulties, macroglossia, hepatomegaly, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which if untreated leads to death from cardiorespiratory failure or respiratory infection, usually by 1 yr of age.

Late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD; juvenile-, childhood-, and adult-onset disease) is characterized by proximal limb girdle muscle weakness and early involvement of respiratory muscles, especially the diaphragm. Cardiac involvement ranges from cardiac rhythm disturbances to cardiomyopathy and a less severe, short-term prognosis. Symptoms related to progressive dysfunction of skeletal muscles can start as early as within 1 yr of age to as late as the 6th decade of life. The clinical picture is dominated by slowly progressive proximal muscle weakness with truncal involvement and greater involvement of the lower limbs than the upper limbs. The pelvic girdle, paraspinal muscles, and diaphragm are the muscle groups most seriously affected in patients with LOPD. Other symptoms may include lingual weakness, ptosis, and dilation of blood vessels (e.g., basilar artery, ascending aorta). With disease progression, patients become confined to a wheelchair and require artificial ventilation. The initial symptoms in some patients may be respiratory insufficiency manifested by somnolence, morning headache, orthopnea, and exertional dyspnea, which eventually lead to sleep-disordered breathing and respiratory failure. Respiratory failure is the cause of significant morbidity and mortality in LOPD. Basilar artery aneurysms with rupture also contribute to mortality in some cases. Small-fiber neuropathy presenting as painful paresthesia has been identified in some LOPD patients. Gastrointestinal disturbances such as postprandial bloating, dysphagia, early satiety, diarrhea, chronic constipation, and irritable bowel disease have been reported. Genitourinary tract involvement is not uncommon and may present as bladder and bowel incontinence, weak urine stream or dribbling. If untreated, the age of death varies from early childhood to late adulthood, depending on the rate of disease progression and the extent of respiratory muscle involvement. With the advent of ERT, a new natural history is emerging for both survivors of infantile and LOPD.

Laboratory Findings

These include elevated levels of serum creatine kinase (CK), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Urine glucose tetrasaccharide, a glycogen breakdown metabolite, is a reliable biomarker for disease severity and treatment response. In the infantile form a chest x-ray film showing massive cardiomegaly is frequently the first symptom detected. Electrocardiographic findings include a high-voltage QRS complex, Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, and a shortened PR interval. Echocardiography reveals thickening of both ventricles and/or the intraventricular septum and/or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Muscle biopsy shows the presence of vacuoles that stain positively for glycogen; acid phosphatase is increased, presumably from a compensatory increase of lysosomal enzymes. EM reveals glycogen accumulation within a membranous sac and in the cytoplasm. Electromyography reveals myopathic features with excessive electrical irritability of muscle fibers and pseudomyotonic discharges. Serum CK is not always elevated in adult patients. Depending on the muscle sampled or tested, the muscle histologic appearance and electromyography may not be abnormal.

Some patients with infantile Pompe disease who had peripheral nerve biopsies demonstrated glycogen accumulation in the neurons and Schwann cells.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Pompe disease can be made by enzyme assay in dried blood spots, leukocytes, blood mononuclear cells, muscle, or cultured skin fibroblasts demonstrating deficient acid α-glucosidase activity. Gene sequencing showing 2 pathogenic variants in the GAA gene is confirmatory. The enzyme assay should be done in a laboratory with experience using maltose, glycogen, or 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D -glucopyranoside (4MUG) as a substrate. The infantile form has a more severe enzyme deficiency than the late-onset forms. Detection of percent residual enzyme activity is captured in skin fibroblasts and muscle. Blood-based assays, especially dried blood spots, have the advantage of a rapid turnaround time and are being increasingly used as the first-line tissue to make a diagnosis. A muscle biopsy is often done with suspected muscle disease and a broad differential; it yields faster results and provides additional information about glycogen content and site of glycogen storage within and outside the lysosomes of muscle cells. However, a normal muscle biopsy does not exclude a diagnosis of Pompe disease. Late-onset patients show variability in glycogen accumulation in different muscles and within muscle fibers; muscle histology and glycogen content can vary depending on the site of muscle biopsy. There is also a high risk from anesthesia in infantile patients. An electrocardiogram can be helpful in making the diagnosis in suspected cases of the infantile form and should be done for patients suspected of having Pompe disease before any procedure requiring anesthesia, including muscle biopsy, is performed. Urinary glucose tetrasaccharides can be elevated in the urine of affected patients, and levels are extremely high in infantile patients. Availability of next-generation sequencing panels and whole exome sequencing allows for identification of additional patients with Pompe disease, especially when the diagnosis is ambiguous. Prenatal diagnosis using amniocytes or chorionic villi is available.

Treatment

Enzyme replacement therapy with recombinant human acid α-glucosidase (alglucosidase alfa) is available for treatment of Pompe disease. Recombinant acid α-glucosidase is capable of preventing deterioration or reversing abnormal cardiac and skeletal muscle functions (Fig. 105.3 ). ERT should be initiated as soon as possible across the disease spectrum, especially for babies with the infantile form, because the disease is rapidly progressive. Infants who are negative for cross-reacting immunologic material (CRIM) develop a high-titer antibody against the infused enzyme and respond to the ERT less favorably. Treatment using immunomodulating agents such as methotrexate, rituximab, and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have demonstrated efficacy in preventing the development of an immune response to ERT and immune tolerance. Nocturnal ventilatory support, when indicated, should be used; it has been shown to improve the quality of life and is particularly beneficial during a period of respiratory decompensation.

In addition to ERT, other adjunctive therapies have demonstrated benefit in Pompe patients. For patients with the late-onset disease, a high-protein diet may be beneficial. Respiratory muscle strength training has demonstrated improvements in respiratory parameters when combined with ERT. Submaximal exercise regimens are of assistance to improve muscle strength, pain, and fatigue. Other approaches are under clinical development to improve the safety and efficacy of enzyme delivery to affected tissues. These include use of chaperone molecules to enhance rhGAA delivery, and neoGAA, which is a second-generation ERT with a high number of mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) tags that enhances M6P receptor targeting and enzyme uptake. Gene therapy studies to correct the endogenous enzyme production pathways have shown promise.

Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary for optimal outcomes. Newborn screening using blood-based assays in Taiwan has resulted in early identification of Pompe cases and thus improved disease outcomes through the early initiation of ERT.

Glycogen Storage Diseases Mimicking Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (Danon Disease)

Danon disease is caused by pathogenic variants in the LAMP2 gene, which leads to a deficiency of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2). This leads to accumulation of glycogen in the heart and skeletal muscle, which presents primarily with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and skeletal muscle weakness. Danon disease can be distinguished from the usual causes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (defects in sarcomere-protein genes) by their electrophysiologic abnormalities, particularly ventricular preexcitation and conduction defects. Patients present with cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, palpitations, syncope, and cardiac arrest, usually between ages 8 and 15 yr. Other clinical manifestations in Danon disease include peripheral pigmentary retinopathy, lens changes, and abnormal electroretinograms. This disorder is inherited in an X-linked dominant pattern. Diagnosis can be done by genetic testing for the LAMP2 gene. The prognosis for LAMP2 deficiency is poor, with progressive end-stage heart failure early in adulthood. Treatment is directed toward management of symptoms in affected individuals, including management of cardiomyopathy, correction of arrhythmias, and physical therapy for muscle weakness. Cardiac transplantation has been tried successfully in some patients.

Adenosine Monophosphate–Activated Protein Kinase γ2 Deficiency (PRKAG2 Deficiency)

AMP-activated protein kinase γ2 (PRKAG2) deficiency is caused by pathogenic variants in the PRKAG2 gene mapped to chromosome 7q36. PRKAG2 is required for the synthesis of the enzyme AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which regulates cellular pathways involved in ATP metabolism. Common presentations include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and electrophysiologic abnormalities such as WPW syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and progressive atrioventricular block. Cardiac involvement is variable and includes supraventricular tachycardia, sinus bradycardia, left ventricular dysfunction, and even sudden cardiac death in some cases. In addition to cardiac involvement, there is a broad spectrum of phenotypic presentations including myalgia, myopathy, and seizures. Cardiomyopathy caused by PRKAG2 variants usually allows for long-term survival, although a rare congenital form presenting in early infancy is associated with a rapidly fatal course. Cardiomyopathy in PRKAG2 syndrome often mimics that in other conditions, especially Pompe disease, and should be considered as a differential diagnosis in infants presenting with severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Treatment is primarily symptomatic, including management of cardiac failure and correction of conduction defects.

Muscle Glycogen Synthase Deficiency

This GSD results from muscle glycogen synthase (glycogen synthase I , GYS1) deficiency. The gene GYS1 has been localized to chromosome 19q13.3. In the true sense, this is not a type of GSD because the deficiency of the enzyme leads to decreased glycogen stores. The disease is extremely rare and has been reported in 3 children of consanguineous parents of Syrian origin. Muscle biopsies showed lack of glycogen, predominantly oxidative fibers, and mitochondrial proliferation. Glucose tolerance was normal. Molecular study revealed a homozygous stop mutation (R462→ter) in the muscle glycogen synthase gene. The phenotype was variable in the 3 siblings and ranged from sudden cardiac arrest, muscle fatigability, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, an abnormal heart rate, and hypotension while exercising, to mildly impaired cardiac function at rest.

Late-Onset Polyglucosan Body Myopathy (From GYG1 Variants)

Late-onset polyglucosan body myopathy is an autosomal recessive, slowly progressive skeletal myopathy caused by pathogenic variants in the GYG1 gene blocking glycogenin-1 biosynthesis. There is a reduced or complete absence of glyogenin-1, which is a precursor necessary for glycogen formation. Polyglucosan accumulation in skeletal muscles causes adult-onset proximal muscle weakness, prominently affecting hip and shoulder girdles. Cardiac involvement is not seen. Compared with GSD IV–APBD, nervous system involvement is uncommon, although polyglucosan deposition is seen in both disorders. GYG1 is mapped to chromosome 3q24. Muscle biopsies show PAS-positive storage material in 30–40% of muscle fibers. EM reveals the typical polyglucosan structure, consisting of ovoid form composed of partly filamentous material.

Type V Glycogen Storage Disease (Muscle Phosphorylase Deficiency, McArdle Disease)

GSD type V is caused by deficiency of myophosphorylase activity. Lack of this enzyme limits muscle ATP generation by glycogenolysis, resulting in muscle glycogen accumulation, and is the prototype of muscle energy disorders. A deficiency of myophosphorylase impairs the cleavage of glucosyl molecules from the straight chain of glycogen.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms usually first develop in late childhood or in the 2nd decade of life. Clinical heterogeneity is uncommon, but cases suggesting otherwise have been documented. Studies have shown that McArdle disease can manifest in individuals as old as 74, as well as in infancy in a fatal, early-onset form characterized by hypotonia, generalized muscle weakness, and respiratory complication. Symptoms are generally characterized by exercise intolerance with muscle cramps and pain. Symptoms are precipitated by 2 types of activity: brief, high-intensity exercise, such as sprinting or carrying heavy loads, and less intense but sustained activity, such as climbing stairs or walking uphill. Most patients can perform moderate exercise, such as walking on level ground, for long periods. Many patients experience a characteristic “second wind” phenomenon, with relief of muscle pain and fatigue after a brief period of rest. As a result of the underlying myopathy, these patients may be at risk for statin-induced myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. While patients typically experience episodic muscle pain and cramping from exercise, 35% of patients with McArdle disease report permanent pain that has a serious impact on sleep and other activities. Studies also suggest that there may also be a link between GSD V and variable cognitive impairment.

Approximately 50% of patients report burgundy-colored urine after exercise as a result of exercise-induced myoglobinuria secondary to rhabdomyolysis . Excessive myoglobinuria after intense exercise may precipitate acute renal failure.

Lab findings show elevated levels of serum CK at rest, which further increases after exercise. Exercise also elevates the levels of blood ammonia, inosine, hypoxanthine, and uric acid, which may be attributed to accelerated recycling of muscle purine nucleotides caused by insufficient ATP production. Type V GSD is an autosomal recessive disorder. The gene for muscle phosphorylase (PYGM) has been mapped to chromosome 11q13.

Diagnosis

The standard diagnosis for GSD V includes a muscle biopsy to measure glycogen content as well as enzyme and sequencing of PYGM . An ischemic exercise test offers a rapid diagnostic screening for patients with a metabolic myopathy. Lack of an increase in blood lactate levels and exaggerated blood ammonia elevations indicate muscle glycogenosis and suggest a defect in the conversion of muscle glycogen or glucose to lactate. The abnormal ischemic exercise response is not limited to type V GSD. Other muscle defects in glycogenolysis or glycolysis produce similar results (deficiencies of muscle phosphofructokinase, phosphoglycerate kinase, phosphoglycerate mutase, or LDH). An ischemic exercise test was once used to be a rapid diagnostic screening for suspected patients but was associated with severe complications and false-positive results. A nonischemic forearm exercise test with high sensitivity that is easy to perform and cost-effective has been determined to be indicative of muscle glycogenosis. However, as with the ischemic test, it cannot differentiate between abnormal exercise responses due to type V disease versus other defects in glycogenolysis or glycolysis or debranching enzyme (noted when the test is done after fasting).

The diagnosis is confirmed by molecular genetic testing of PYGM. A common nonsense variant, p.R49X in exon 1, is found in 90% of Caucasian patients, and a deletion of a single codon in exon 17 is found in 61% of Japanese patients. The p.R49X variant represents 55% of alleles in Spanish patients, whereas the p.W797R variant represents 14% and the p.G204S 9% of pathogenic alleles in the Spanish population. There seems to be an association between clinical severity of GSD V and presence of the D allele of the ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism. This may help explain the spectrum of phenotypic variability manifested in this disorder.

Treatment

Avoidance of strenuous exercise prevents the symptoms; regular and moderate exercise is recommended to improve exercise capacity. Glucose or sucrose given before exercise or injection of glucagon can greatly improve tolerance in these patients. A high-protein diet may increase muscle endurance, and low-dose creatine supplement has been shown to improve muscle function in some patients. The clinical response to creatine is dose dependent; muscle pain may increase on high doses of creatine supplementation. Vitamin B6 supplementation reduces exercise intolerance and muscle cramps. Longevity is not generally affected.

Type VII Glycogen Storage Disease (Muscle Phosphofructokinase Deficiency, Tarui Disease)

Type VII GSD is caused by pathogenic variants in the PFKM gene, located on chromosome 12q13.1, which results in a deficiency of muscle phosphofructokinase enzyme. This enzyme is a key regulatory enzyme of glycolysis and is necessary for the ATP-dependent conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-diphosphate. Phosphofructokinase is composed of 3 isoenzyme subunits according to the tissue type and are encoded by different genes: (PFKM [M: muscle], PFKL [L: liver], and PFKP [P: platelet]). Skeletal muscle has only the M subunit, whereas red blood cells (RBCs) express a hybrid of L and M forms. In type VII GSD the M isoenzyme is defective, resulting in complete deficiency of enzyme activity in muscle and a partial deficiency in RBCs.

Type VII GSD is an autosomal recessive disorder with increased prevalence in individuals of Japanese ancestry and Ashkenazi Jews. A splicing defect and a nucleotide deletion in PFKM account for 95% of pathogenic variants in Ashkenazi Jews. Diagnosis based on molecular testing for the common variants is thus possible in this population.

Clinical Manifestations

Although the clinical picture is similar to that of type V GSD, the following features of type VII GSD are distinctive:

- 1. Exercise intolerance, which usually commences in childhood, is more severe than in type V disease and may be associated with nausea, vomiting, and severe muscle pain; vigorous exercise causes severe muscle cramps and myoglobinuria.

- 2. Compensatory hemolysis occurs, as indicated by an increased level of serum bilirubin and an elevated reticulocyte count.

- 3. Hyperuricemia is common and exaggerated by muscle exercise to a greater degree than that observed in type V or III GSD.

- 4. An abnormal polysaccharide is present in muscle fibers; it is PAS positive but resistant to diastase digestion.

- 5. Exercise intolerance is especially worse after carbohydrate-rich meals because the ingested glucose prevents lipolysis, thereby depriving muscle of fatty acid and ketone substrates. This is in contrast to patients with type V disease, who can metabolize blood borne glucose derived from either endogenous liver glycogenolysis or exogenous glucose; indeed, glucose infusion improves exercise tolerance in type V patients.

- 6. The “second wind” phenomenon is absent because of the inability to break down blood glucose.

Several rare type VII variants occur. One variant presents in infancy with hypotonia and limb weakness and proceeds to a rapidly progressive myopathy that leads to death by 4 yr of age. A 2nd variant occurs in infancy and results in congenital myopathy and arthrogryposis with a fatal outcome. A 3rd variant presents in infancy with hypotonia, mild developmental delay, and seizures. An additional presentation is hereditary nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia . Although these patients do not experience muscle symptoms, it remains unclear whether these symptoms will develop later in life. One variant presents in adults and is characterized by a slowly progressive, fixed muscle weakness rather than cramps and myoglobinuria. It may also cause mitral valve thickening from glycogen buildup.

Diagnosis

To establish a diagnosis, a biochemical or histochemical demonstration of the enzymatic defect in the muscle is required. The absence of the M isoenzyme of phosphofructokinase can also be demonstrated in muscle, blood cells, and fibroblasts. Gene sequencing can identify pathogenic variants for the phosphofructokinase gene.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment. Strenuous exercise should be avoided to prevent acute episodes of muscle cramps and myoglobinuria. Consuming simple carbohydrates before strenuous exercise may benefit by improving exercise tolerance. A ketogenic diet has been reported to show clinical improvement in a patient with infantile GSD VII. Drugs such as statins should be avoided. Precautionary measures should be taken to avoid hyperthermia while undergoing anesthesia. Carbohydrate meals and glucose infusions have demonstrated worsening symptoms because of the body's inability to utilize glucose. The administered glucose tends to lower the levels of fatty acids in the blood, a primary source of muscle fuel.

Muscle-Specific Phosphorylase Kinase Deficiency (From PHKA1 Variants)

A few cases of PhK deficiency restricted to muscle are known. Patients, both male and female, present either with muscle cramps and myoglobinuria with exercise or with progressive muscle weakness and atrophy. PhK activity is decreased in muscle but normal in liver and blood cells. There is no hepatomegaly or cardiomegaly. This is inherited in an X-linked or autosomal recessive manner. The gene for the muscle-specific form α subunit (αM) is located at Xq12. Pathogenic variants of the gene have been found in some male patients with this disorder. The gene for muscle γ subunit (γM, PHKG1 ) is on chromosome 7p12. No pathogenic variants in this gene have been reported so far.

Other Muscle Glycogenoses With Muscle Energy Impairment

Six additional defects in enzymes—phosphoglycerate kinase, phosphoglycerate mutase, lactate dehydrogenase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase A, muscle pyruvate kinase, and β-enolase in the pathway of the terminal glycolysis—cause symptoms and signs of muscle energy impairment similar to those of types V and VII GSD. The failure of blood lactate to increase in response to exercise is a useful diagnostic test and can be used to differentiate muscle glycogenoses from disorders of lipid metabolism, such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency and very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, which also cause muscle cramps and myoglobinuria. Muscle glycogen levels can be normal in the disorders affecting terminal glycolysis, and assaying the muscle enzyme activity is needed to make a definitive diagnosis. There is no specific treatment (see preceding Treatment section).

Bibliography

Akman HO, Aykit Y, Amuk OC, et al. Late-onset polyglucosan body myopathy in five patients with a homozygous mutation in GYG1 . Neuromuscul Disord . 2016;26(1):16–20.

Byrne BJ, Falk DJ, Pacel CA, et al. Pompe disease gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet . 2011;20:R61–R68.

Case LE, Beckemeyer AA, Kishnani PS. Infantile Pompe disease on ERT—update on clinical presentation, musculoskeletal management, and exercise considerations. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet . 2012;160C:69–79.

Chiang SC, Hwu WL, Lee NC, et al. Algorithm for Pompe disease newborn screening: results from the Taiwan screening program. Mol Genet Metab . 2012;106(3):281–286.

Chien YH, Lee NC, Huang HJ, et al. Later-onset Pompe disease: early detection and early treatment initiation enabled by newborn screening. J Pediatr . 2011;158:1023–1027.

D'Souza R, Levandowski C, Slavov D, et al. Danon disease: clinical features, evaluation, and management. Circ Heart Fail . 2014;7(5):843–849.

DiMauro S, Spiegel R. Progress and problems in muscle glycogenoses. Acta Myol . 2011;30(2):96–102.

Elder ME, Nayak S, Collins SW, et al. B-cell depletion and immunomodulation before initiation of enzyme replacement therapy blocks the immune response to acid alpha-glucosidase in infantile-onset Pompe disease. J Pediatr . 2013;163:847–854.

Hopkins PV, Campbell C1, Klug T, et al. Lysosomal storage disorder screening implementation: findings from the first six months of full population pilot testing in Missouri. J Pediatr . 2015;166(1):172–177.

Kishnani PS, Austin SL, Abdenur JE, et al. Diagnosis and management of glycogen storage disease type I: a practice guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med . 2014;16(11):e1.

Kishnani PS, Austin SL, Arn P, et al. Glycogen storage disease type III diagnosis and management guidelines. Genet Med . 2010;12(7):446–463.

Kronn DF, Day-Salvatore D, Hwu WL, et al. Management of confirmed newborn-screened patients with Pompe disease across the disease spectrum. Pediatrics . 2016;140(1):e20160280.

Maga JA, Zhou J, Kambampati R, et al. Glycosylation-independent lysosomal targeting of acid α-glucosidase enhances muscle glycogen clearance in Pompe mice. J Biol Chem . 2013;288(3):1428–1438.

Miteff F, Potter HC, Allen J, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of patients with myophosphorylase deficiency (McArdle disease). J Clin Neurosci . 2011;18(8):1055–1058.

Poelman E, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Kross-de Haan MA, et al. High sustained antibody titers in patients with classic infantile Pompe disease following immunomodulation at start of enzyme replacement therapy. J Pediatr . 2018;195:236–243.

Porto A, Brun F, Severini G, et al. Clinical spectrum of PRKAG2 syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol . 2016;9(1):e003121.

Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, et al. Emery and Rimoin's principles and practice of medical genetics . Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: New York; 2011.