Encephalopathies

Michael V. Johnston

Encephalopathy is a generalized disorder of cerebral function that may be acute or chronic, progressive, or static. The etiologies of the encephalopathies in children include infectious, toxic (carbon monoxide, drugs, lead), metabolic, genetic, and ischemic causes. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy is discussed in Chapter 120.4 .

Cerebral Palsy

Michael V. Johnston

See also Chapters 53 , 117.2 , and 615.4 .

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a diagnostic term used to describe a group of permanent disorders of movement and posture causing activity limitation that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances in the developing fetal or infant brain. The motor disorders are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication, and behavior as well as by epilepsy and secondary musculoskeletal problems. CP is caused by a broad group of developmental, genetic, metabolic, ischemic, infectious, and other acquired etiologies that produce a common group of neurologic phenotypes. CP has historically been considered a static encephalopathy, but some of the neurologic features of CP, such as movement disorders and orthopedic complications, including scoliosis and hip dislocation, can change or progress over time. Many children and adults with CP function at a high educational and vocational level, without any sign of cognitive dysfunction.

Epidemiology and Etiology

CP is the most common and costly form of chronic motor disability that begins in childhood; data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that the incidence is 3.6 per 1,000 children with a male:female ratio of 1.4 : 1. The Collaborative Perinatal Project, in which approximately 45,000 children were regularly monitored from in utero to the age of 7 yr, found that most children with CP had been born at term with uncomplicated labors and deliveries. In 80% of cases, features were identified pointing to antenatal factors causing abnormal brain development. A substantial number of children with CP had congenital anomalies external to the central nervous system (CNS). Fewer than 10% of children with CP had evidence of intrapartum asphyxia. Intrauterine exposure to maternal infection (chorioamnionitis, inflammation of placental membranes, umbilical cord inflammation, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, maternal sepsis, temperature > 38°C during labor, urinary tract infection) was associated with a significant increase in the risk of CP in normal birthweight infants. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines have been reported in heelstick blood collected at birth from children who later were identified with CP. Genetic factors may contribute to the inflammatory cytokine response, and a functional polymorphism in the interleukin-6 gene is associated with a higher rate of CP in term infants.

The prevalence of CP has increased somewhat as a result of the enhanced survival of very premature infants weighing < 1,000 g, who go on to develop CP at a rate of approximately 15 per 100. However, the gestational age at birth-adjusted prevalence of CP among 2 yr old former premature infants born at 20-27 wk of gestation has decreased over the past decade. The major lesions that contribute to CP in preterm infants are intracerebral hemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL). Although the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage has declined significantly, PVL remains a major problem. PVL reflects the enhanced vulnerability of immature oligodendroglia in premature infants to oxidative stress caused by ischemia or infectious/inflammatory insults. White matter abnormalities (loss of volume of periventricular white matter, extent of cystic changes, ventricular dilation, thinning of the corpus callosum) present on MRI at 40 wk of gestational age in former preterm infants are a predictor of later CP.

In 2006, the European Cerebral Palsy Study examined prenatal and perinatal factors as well as clinical findings and results of MRI in a contemporary cohort of more than 400 children with CP. In agreement with the Collaborative Perinatal Project study, more than half the children with CP in this study were born at term, and less than 20% had clinical or brain imaging indicators of possible intrapartum factors such as asphyxia. The contribution of intrapartum factors to CP is higher in some underdeveloped regions of the world. Also in agreement with earlier data, antenatal infection was strongly associated with CP and 39.5% of mothers of children with CP reported having an infection during the pregnancy, with 19% having evidence of a urinary tract infection and 11.5% reporting taking antibiotics. Multiple pregnancy was also associated with a higher incidence of CP and 12% of the cases in the European CP study resulted from a multiple pregnancy, in contrast to a 1.5% incidence of multiple pregnancy in the study. Other studies have also documented a relationship between multiple births and CP, with a rate in twins that is 5-8 times greater than in singleton pregnancies and a rate in triplets that is 20-47 times greater. Death of a twin in utero carries an even greater risk of CP; it is 8 times that of a pregnancy in which both twins survive and approximately 60 times the risk in a singleton pregnancy. Infertility treatments are also associated with a higher rate of CP, probably because these treatments are often associated with multiple pregnancies. Among children from multiple pregnancies, 24% were from pregnancies after infertility treatment compared with 3.4% of the singleton pregnancies in the study. CP is more common and more severe in boys than girls, and this effect is enhanced at the extremes of body weight. Male infants with intrauterine growth retardation and a birthweight less than the 3rd percentile are 16 times more likely to have CP than males with optimal growth, and infants with weights above the 97th percentile are 4 times more likely to have CP.

Clinical Manifestations

CP is generally divided into several major motor syndromes that differ according to the pattern of neurologic involvement, neuropathology, and etiology (Table 616.1 ). The physiologic classification identifies the major motor abnormality, whereas the topographic taxonomy indicates the involved extremities. CP is also commonly associated with a spectrum of developmental disabilities, including intellectual impairment, epilepsy, and visual, hearing, speech, cognitive, and behavioral abnormalities. The motor handicap may be the least of the child's problems.

Table 616.1

Classification of Cerebral Palsy and Major Causes

| MOTOR SYNDROME (APPROX. % OF CP) | NEUROPATHOLOGY/MRI | MAJOR CAUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Spastic diplegia (35%) |

Periventricular leukomalacia Periventricular cysts or scars in white matter, enlargement of ventricles, squared-off posterior ventricles |

Prematurity |

| Ischemia | ||

| Infection | ||

| Endocrine/metabolic (e.g., thyroid) | ||

| Spastic quadriplegia (20%) | Periventricular leukomalacia | Ischemia, infection |

|

Multicystic encephalomalacia Cortical malformations |

Endocrine/metabolic, genetic/developmental | |

| Hemiplegia (25%) |

Stroke: in utero or neonatal Focal infarct or cortical, subcortical damage Cortical malformations |

Thrombophilic disorders |

| Infection | ||

| Genetic/developmental | ||

| Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction | ||

| Extrapyramidal (athetoid, dyskinetic) (15%) |

Asphyxia: symmetric scars in putamen and thalamus Kernicterus: scars in globus pallidus, hippocampus Mitochondrial: scarring of globus pallidus, caudate, putamen, brainstem No lesions: ? dopa-responsive dystonia |

Asphyxia |

| Kernicterus | ||

| Mitochondrial | ||

| Genetic/metabolic |

Infants with spastic hemiplegia have decreased spontaneous movements on the affected side and show hand preference at a very early age. The arm is often more involved than the leg and difficulty in hand manipulation is obvious by 1 yr of age. Walking is usually delayed until 18-24 mo, and a circumductive gait is apparent. Examination of the extremities may show growth arrest, particularly in the hand and thumbnail, especially if the contralateral parietal lobe is abnormal, because extremity growth is influenced by this area of the brain. Spasticity refers to the quality of increased muscle tone, which increases with the speed of passive muscle stretching and is greatest in antigravity muscles. It is apparent in the affected extremities, particularly at the ankle, causing an equinovarus deformity of the foot. An affected child often walks on tiptoe because of the increased tone in the antigravity gastrocnemius muscles, and the affected upper extremity assumes a flexed posture when the child runs. Ankle clonus and a Babinski sign may be present, the deep tendon reflexes are increased, and weakness of the hand and foot dorsiflexors is evident. Difficulty in selective motor control is also present. About one third of patients with spastic hemiplegia have a seizure disorder that usually develops in the first year or two; approximately 25% have cognitive abnormalities including mental retardation. MRI is far more sensitive than cranial CT scan for most lesions seen with CP, although a CT scan may be useful for detecting calcifications associated with congenital infections. In the European CP study, 34% of children with hemiplegia had injury to the white matter that probably dated to the in utero period and 27% had a focal lesion that may have resulted from a stroke. Other children with hemiplegic CP had malformations from multiple causes including infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus), lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, schizencephaly, or cortical dysplasia. Focal cerebral infarction (stroke) secondary to intrauterine or perinatal thromboembolism related to thrombophilic disorders, such as the presence of anticardiolipin antibodies, is an important cause of hemiplegic CP (see Chapter 619 ). Family histories suggestive of thrombosis and inherited clotting disorders, such as factor V Leiden mutation, may be present and evaluation of the mother may provide information valuable for future pregnancies and other family members.

Spastic diplegia is bilateral spasticity of the legs that is greater than in the arms. Spastic diplegia is strongly associated with damage to the immature white matter during the vulnerable period of immature oligodendroglia between 20-34 wk of gestation. However, approximately 15% of cases of spastic diplegia result from in utero lesions in infants who go on to delivery at term. The first clinical indication of spastic diplegia is often noted when an affected infant begins to crawl. The child uses the arms in a normal reciprocal fashion but tends to drag the legs behind more as a rudder (commando crawl) rather than using the normal 4-limbed crawling movement. If the spasticity is severe, application of a diaper is difficult because of the excessive adduction of the hips. If there is paraspinal muscle involvement, the child may be unable to sit. Examination of the child reveals spasticity in the legs with brisk reflexes, ankle clonus, and a bilateral Babinski sign. When the child is suspended by the axillae, a scissoring posture of the lower extremities is maintained. Walking is significantly delayed, the feet are held in a position of equinovarus, and the child walks on tiptoe. Severe spastic diplegia is characterized by disuse atrophy and impaired growth of the lower extremities and by disproportionate growth with normal development of the upper torso. The prognosis for normal intellectual development for these patients is good, and the likelihood of seizures is minimal. Such children often have learning disabilities and deficits in other abilities, such as vision, because of disruption of multiple white matter pathways that carry sensory as well as motor information.

The most common neuropathologic finding in children with spastic diplegia is periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), which is visualized on MRI in more than 70% of cases. MRI typically shows scarring and shrinkage in the periventricular white matter with compensatory enlargement of the cerebral ventricles. However, neuropathology has also demonstrated a reduction in oligodendroglia in more widespread subcortical regions beyond the periventricular zones, and these subcortical lesions may contribute to the learning problems these patients can have. MRI with diffusion tensor imaging is being used to map white matter tracks more precisely in patients with spastic diplegia, and this technique has shown that thalamocortical sensory pathways are often injured as severely as motor corticospinal pathways (Fig. 616.1 ). These observations have led to greater interest in the importance of sensory deficits in these patients, which may be important for designing rehabilitative techniques.

Spastic quadriplegia is the most severe form of CP because of marked motor impairment of all extremities and the high association with intellectual disability and seizures. Swallowing difficulties are common as a result of supranuclear bulbar palsies, often leading to aspiration pneumonia and growth failure. The most common lesions seen on pathologic examination or on MRI scanning are severe PVL and multicystic cortical encephalomalacia. Neurologic examination shows increased tone and spasticity in all extremities, decreased spontaneous movements, brisk reflexes, and plantar extensor responses. Flexion contractures of the knees, elbows, and wrists are often present by late childhood. Associated developmental disabilities, including speech and visual abnormalities, are particularly prevalent in this group of children. Children with spastic quadriparesis often have evidence of athetosis and may be classified as having mixed CP.

Athetoid CP, also called choreoathetoid, extrapyramidal, or dyskinetic CP, is less common than spastic CP and makes up approximately 15–20% of patients with CP. Affected infants are characteristically hypotonic with poor head control and marked head lag and develop variably increased tone with rigidity and dystonia over several years. The term dystonia refers to the abnormality in tone in which muscles are rigid throughout their range of motion and involuntary contractions can occur in both flexors and extensors leading to limb positioning in fixed postures. Unlike spastic diplegia, the upper extremities are generally more affected than the lower extremities in extrapyramidal CP. Feeding may be difficult, and tongue thrust and drooling may be prominent. Speech is typically affected because the oropharyngeal muscles are involved. Speech may be absent or sentences are slurred, and voice modulation is impaired. Generally, upper motor neuron signs are not present, seizures are uncommon, and intellect is preserved in many patients. This form of CP is also referred to in Europe as dyskinetic CP and is the type most likely to be associated with birth asphyxia. In the European CP study, 76% of patients with this form of CP had lesions in the basal ganglia and thalamus. Extrapyramidal CP secondary to acute intrapartum near-total asphyxia is associated with bilaterally symmetric lesions in the posterior putamen and ventrolateral thalamus. These lesions appear to be the correlate of the neuropathologic lesion called status marmoratus in the basal ganglia. Athetoid CP can also be caused by kernicterus secondary to high levels of bilirubin, and in this case the MRI scan shows lesions in the globus pallidus bilaterally. Extrapyramidal CP can also be associated with lesions in the basal ganglia and thalamus caused by metabolic genetic disorders such as mitochondrial disorders and glutaric aciduria. MRI scanning and possibly metabolic testing are important in the evaluation of children with extrapyramidal CP to make a correct etiologic diagnosis. In patients with dystonia who have a normal MRI, it is important to have a high level of suspicion for dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-responsive dystonia (Segawa disease), which causes prominent dystonia that can resemble CP. These patients typically have diurnal variation in their signs with worsening dystonia in the legs during the day; however, this may not be prominent. These patients can be tested for a response to small doses of L-dopa and/or cerebrospinal fluid can be sent for neurotransmitter analysis.

Associated comorbidities are common and include pain (in 75%), cognitive disability (50%), hip displacement (30%), seizures (25%), behavioral disorders (25%), sleep disturbances (20%), visual impairment (19%), and hearing impairment (4%).

Diagnosis

A thorough history and physical examination should preclude a progressive disorder of the CNS, including degenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, spinal cord tumor, or muscular dystrophy. The possibility of anomalies at the base of the skull or other disorders affecting the cervical spinal cord needs to be considered in patients with little involvement of the arms or cranial nerves. An MRI scan of the brain is indicated to determine the location and extent of structural lesions or associated congenital malformations; an MRI scan of the spinal cord is indicated if there is any question about spinal cord pathology. Additional studies may include tests of hearing and visual function. Genetic evaluation should be considered in patients with congenital malformations (chromosomes) or evidence of metabolic disorders (e.g., amino acids, organic acids, MR spectroscopy). In addition to the genetic disorders mentioned earlier that can present as CP, the urea cycle disorder arginase deficiency is a rare cause of spastic diplegia and a deficiency of sulfite oxidase or molybdenum cofactor can present as CP caused by perinatal asphyxia. Tests to detect inherited thrombophilic disorders may be indicated in patients in whom an in utero or neonatal stroke is suspected as the cause of CP. Because CP is usually associated with a wide spectrum of developmental disorders, a multidisciplinary approach is most helpful in the assessment and treatment of such children. The differential diagnosis must include disorders that may mimic the various types of CP. These may include the hereditary spastic diplegias (Table 616.2 ), monoamine transmitter disorders (Table 616.3 and Fig. 616.2 ), and many treatable inborn errors of metabolism, including disorders of amino acids, creatine, fatty acid oxidation, lysosomes, mitochondria, organic acids, and vitamin cofactors.

Table 616.2

Clinical and Neuroimaging Findings in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias (HSP) with Pediatric Onset*

| HSP FORM | HSP TYPE | INHERITANCE | GENE | CHILDHOOD ONSET | DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS † | NEUROIMAGING FINDINGS (BRAIN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure | SPG3A | Aut. dom | ATL1 | +++ | None | Normal |

| Pure | SPG4 | Aut. dom | SPAST | ++ | None | Leukoencephalopathy, thin corpus callosum |

| Pure | SPG6 | Aut. dom | NIPA1 | + | None | Normal |

| Pure | SPG10 | Aut. dom | KIF5A | +++ | Neuropathy | Normal |

| Pure | SPG12 | Aut. dom | RTN2 | +++ | None | Normal |

| Pure | SPG31 | Aut. dom | REEP1 | ++ | None | Normal |

| Complicated | SPG1 | X-linked | L1CAM | ++ | Intellectual disability, adducted thumb | Thin corpus callosum |

| Complicated | SPG2 | X-linked | PLP1 | +++ | Intellectual disability, epilepsy | Normal |

| Complicated | SPG7 | Aut. rec. | SPG7 | + | Optic atrophy, neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia | Cerebellar atrophy |

| Complicated | SPG11 | Aut. rec. | KIAA1840 | +++ | Intellectual disability, neuropathy | Leukoencephalopathy, thin corpus callosum |

| Complicated | SPG15 | Aut. rec. | ZFYVE26 | +++ | Intellectual disability, retinopathy, cerebellar ataxia | Leukoencephalopathy, thin corpus callosum |

| Complicated | SPG17 | Aut. rec. | BSCL2 | + | Neuropathy | Normal |

* Onset before 18 yr of age.

† Other than the classic HSP symptoms, including spastic paraparesis, atrophy of the distal lower extremities, and neurogenic bladder dysfunction.

Aut. dom., autosomal dominant; aut. rec., autosomal recessive; +, occasional; ++, common; +++, characteristic.

From Lee RW, Poretti A, Cohen JS, et al: A diagnostic approach for cerebral palsy in the genomic era, Neurol Med 16:821-844, 2014, Table 5, p. 832.

Table 616.3

Clinical Features of the Monoamine Neurotransmitter Disorders

| AGE AT PRESENTATION | MOTOR AND COGNITIVE DELAY | EXTRAPYRAMIDAL HYPERKINETIC FEATURES | EXTRAPYRAMIDAL HYPOKINETIC FEATURES | PYRAMIDAL TRACT FEATURES | EPILEPSY | AUTONOMIC FEATURES | NEUROPSYCHIATRIC FEATURES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD GTPCH-D | Childhood (but can occur at any age) | Not common | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| SR-D | Infancy | In most | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AR GTPCH-D | Infancy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PTPS-D | Infancy to childhood | In most | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| DHPR-D | Infancy to childhood | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PCD-D | Infancy | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| TH-D | Infancy to early childhood | In most | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AADC-D | Mainly infancy (but can occur at any age) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PLP-DE | Infancy to early childhood | In most | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| DTDS | Infancy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes in older children | No | Yes | No |

From Kurian MA, Gissen P, Smith M, et al: The monoamine neurotransmitter disorders: an expanding range of neurological syndromes, Lancet Neurol 10:721-731, 2011, Table, p. 722.

Treatment

Some progress has been made in both prevention of CP before it occurs and treatment of children with the disorder. Preliminary results from controlled trials of magnesium sulfate, given intravenously to mothers in premature labor with birth imminent before 32 wk gestation, showed a significant reduction in the risk of CP at 2 yr of age. Nonetheless, one study that followed preterm infants whose mothers received magnesium sulfate demonstrated no benefit in terms of the incidence of CP and abnormal motor, cognitive, or behavioral function at school age. Furthermore, several large trials have shown that cooling term infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy to 33.3°C for 3 days, starting within 6 hr of birth, reduces the risk of the dyskinetic or spastic quadriplegia form of CP.

For children who have a diagnosis of CP, a team of physicians, including neurodevelopmental pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, and physical medicine and rehabilitation specialists, as well as occupational and physical therapists, speech pathologists, social workers, educators, and developmental psychologists, is important to reduce abnormalities of movement and tone and to optimize normal psychomotor development. Parents should be taught how to work with their child in daily activities such as feeding, carrying, dressing, bathing, and playing in ways that limit the effects of abnormal muscle tone. Families and children also need to be instructed in the supervision of a series of exercises designed to prevent the development of contractures, especially a tight Achilles tendon. Physical and occupational therapies are useful for promoting mobility and the use of the upper extremities for activities of daily living. Speech language pathologists promote acquisition of a functional means of communication and work on swallowing issues. These therapists help children to achieve their potential and often recommend further evaluations and adaptive equipment.

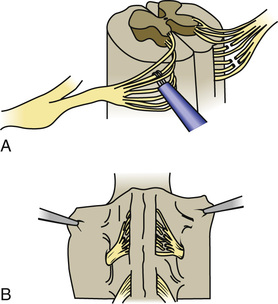

Children with spastic diplegia are treated initially with the assistance of adaptive equipment, such as orthoses, walkers, poles, and standing frames. If a patient has marked spasticity of the lower extremities or evidence of hip dislocation, consideration should be given to performing surgical soft-tissue procedures that reduce muscle spasm around the hip girdle, including an adductor tenotomy or psoas transfer and release. A rhizotomy procedure in which the roots of the spinal nerves are divided produces considerable improvement in selected patients with severe spastic diplegia and little or no basal ganglia involvement (Fig. 616.3 ). A tight heel cord in a child with spastic hemiplegia may be treated surgically by tenotomy of the Achilles tendon or sometimes with serial botulinum toxin injections. Quadriplegia is managed with motorized wheelchairs, special feeding devices, modified typewriters, and customized seating arrangements. The function of the affected extremities in children with hemiplegic CP can often be improved by therapy in which movement of the good side is constrained with casts while the impaired extremities perform exercises that induce improved hand and arm functioning. This constraint-induced movement therapy is effective in patients of all ages.

Several drugs have been used to treat spasticity, including the benzodiazepines and baclofen. These medications have beneficial effects in some patients but can also cause side effects such as sedation for benzodiazepines and lowered seizure threshold for baclofen. Several drugs can be used to treat spasticity, including oral diazepam (0.01-0.3 mg/kg/day, divided bid or qid), baclofen (0.2-2 mg/kg/day, divided bid or tid), or dantrolene (0.5-10 mg/kg/day, bid). Small doses of levodopa (0.5-2 mg/kg/day) can be used to treat dystonia or DOPA-responsive dystonia. Artane (trihexyphenidyl, 0.25 mg/day, divided bid or tid and titrated upward) is sometimes useful for treating dystonia and can increase the use of the upper extremities and vocalizations. Reserpine (0.01-0.02 mg/kg/day, divided bid to a maximum of 0.25 mg daily) or tetrabenazine (12.5-25.0 mg, divided bid or tid) can be useful for hyperkinetic movement disorders, including athetosis or chorea.

Intrathecal baclofen delivered with an implanted pump has been used successfully in many children with severe spasticity, and can be useful because it delivers the drug directly around the spinal cord where it reduces neurotransmission of afferent nerve fibers. Direct delivery to the spinal cord overcomes the problem of CNS side effects caused by the large oral doses needed to penetrate the blood–brain barrier. This therapy requires a team approach and constant follow-up for complications of the infusion pumping mechanism and infection.

Botulinum toxin injected into specific muscle groups for the management of spasticity shows a very positive response in many patients. Botulinum toxin injected into salivary glands may also help reduce the severity of drooling, which is seen in 10–30% of patients with CP and has been traditionally treated with anticholinergic agents. Patients with rigidity, dystonia, and spastic quadriparesis sometimes respond to levodopa, and children with dystonia may benefit from carbamazepine or trihexyphenidyl. Deep brain stimulation has been used in selected refractory patients. Hyperbaric oxygen has not been shown to improve the condition of children with CP.

Communication skills may be enhanced by the use of Bliss symbols, talking typewriters, electronic speech–generating devices, and specially adapted computers, including artificial intelligence computers to augment motor and language function. Significant behavior problems may substantially interfere with the development of a child with CP; their early identification and management are important, and the assistance of a psychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary. Learning and attention deficit disorders and mental retardation are assessed and managed by a psychologist and educator. Strabismus, nystagmus, and optic atrophy are common in children with CP; an ophthalmologist should be included in the initial assessment and ongoing treatment. Lower urinary tract dysfunction should receive prompt assessment and treatment.

Bibliography

Albavera-Hernandez C, Rodriguez JM, Idrovo AJ. Safety of botulinum toxin type a among children with spasticity secondary to cerebral palsy: a systemic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin Rehabil . 2009;23:394–407.

Bax M, Tydeman C, Flodmark O. Clinical and MRI correlates of cerebral palsy. JAMA . 2006;296:1602–1608.

Benfer KA, Weir KA, Bell KL, et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and gross motor skills in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics . 2013;131:e1553–e1562.

Benini R, Dagenais L, Shevell MI, et al. Normal imaging in patients with cerebral palsy: what does it tell us? J Pediatr . 2013;162:369–374.

Brunstrom JE, Bastion AJ, Wong M. Motor benefit from levodopa in spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol . 2000;47:662–665.

Chang CH, Chen YY, Yeh KK, Chen CL. Gross motor function change after multilevel soft tissue release in children with cerebral palsy. Biomed J. 2017;40(3):163–168.

Colver A, Fairhurst C, Pharoah POD. Cerebral palsy. Lancet . 2014;383:1240–1246.

Daunter AK, Kratz AL, Hurvitz EA. Long-term impact of childhood selective dorsal rhizotomy on pain, fatigue, and function: a case-control study. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2017;59(10):1089–1095.

Delgado MR, Hirtz D, Aisen M, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacologic treatment of spasticity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (an evidence-based review). Neurology . 2010;74:336–343.

Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, Haslam R, et al. School-age outcomes of very preterm infants after antenatal treatment with magnesium sulfate vs placebo. JAMA . 2014;321:1105–1112.

Eek MN. Muscle strength training to improve gait function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2008;50:759–764.

Gordon AM, Charles J, Wolf SL. Efficacy of constraint-induced movement therapy on involved upper-extremity use in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy is not age-dependent. Pediatrics . 2006;117:363–373.

Graham EM, Ruis KA, Hartman AL, et al. A systemic review of the role of intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia in the causation of neonatal encephalopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2008;199:587–595.

Himmelmann K, McManus V, Hagberg G, et al. Dyskinetic cerebral palsy in Europe: trends in prevalence and severity. Arch Dis Child . 2009;94:921–926.

Hoon AH Jr, Stashinko EE, Nagae LM, et al. Sensory and motor deficits in children with cerebral palsy born preterm correlate with diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities in thalamocortical pathways. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2009;51:697–704.

Huntsman R, Lemire E, Norton J, et al. The differential diagnosis of spastic diplegia. Arch Dis Child . 2015;100:500–504.

Johnston MV, Faemi A, Wilson MA, et al. Treatment advances in neonatal neuroprotection and neurointensive care. Lancet Neurol . 2011;10:372–382.

Kurian MA, Gissen P, Smith M, et al. The monoamine neurotransmitter disorders: an expanding range of neurological syndromes. Lancet Neurol . 2011;10:721–731.

Leach EL, Shevell M, Bowden K, et al. Treatable inborn errors of metabolism presenting as cerebral palsy mimics: systematic literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2014;9:197.

Lee RW, Poretti A, Cohen JS, et al. A diagnostic approach for cerebral palsy in the genomic era. Neurol Med . 2014;16:821–844.

Mugglestone MA, Eunson P, Murphy MS. Spasticity in children and young people with non-progressive brain disorders: summary of NICE guidelines. BMJ . 2012;345:e4845.

Nagae LM, Hoon AH Jr, Stashinko E, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in children with periventricular leukomalacia: variability of injuries to white matter tracts. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2007;28:1213–1222.

Nelson KB. Causative factors in cerebral palsy. Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2008;51:749–762.

Novak I, Hines M, Goldsmith S, et al. Clinical prognostic messages from a systematic review on cerebral palsy. Pediatrics . 2012;130:e1285–e1312.

Robertson CM, Watt MJ, Yasul Y. Changes in the prevalence of cerebral palsy for children born very prematurely within a population-based program over 30 years. JAMA . 2007;297:2733–2740.

Robinson MN, Peake LJ, Ditchfield MR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in a population-based cohort of children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2009;51:39–45.

Rouse DJ, Hirtz DG, Thom E, et al. Eunice kennedy shriver NICHD Maternal-fetal medicine units network: a randomized, controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med . 2008;359:895–905.

Sakzewski L, Ziciani J, Boyd R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic management of upper-limb dysfunction in children with congenital hemiplegia. Pediatrics . 2009;123:e1111–e1122.

Shevell MI, Dagenais L, Hall N, et al. The relationship of cerebral palsy subtype and functional motor impairment: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2009;51:872–877.

Sterling C, Taub E, Davis D, et al. Structural neuroplastic change after constraint induced movement therapy in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics . 2013;131:e1664–e1669.

Taylor CL, de Groot J, Blair EM, et al. The risk of cerebral palsy in survivors of multiple pregnancies with co-fetal loss or death. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2009;201:41–47.

Wu YW, Croen LA, Torres AR, et al. Interleukin-6 and risk for cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. Ann Neurol . 2009;66:663–670.

Yeargin-Allsopp M, Van Naarden Barun K, Doernberg N, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy in 8-year-old children in three areas of the United States in 2002: a multisite collaboration. Pediatrics . 2008;121:547–554.

Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

Michael V. Johnston

See Chapters 105.4 and 629.4 .

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies are a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes caused by genetic lesions that impair energy production through oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial function. The signs and symptoms of these disorders reflect the vulnerability of the nervous system, muscles, and other organs to energy deficiency. Signs of brain and muscle dysfunction (seizures, weakness, ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, psychomotor regression, hearing loss, movement disorders, and ataxia) in association with lactic acidosis are prominent features of mitochondrial disorders. Cardiomyopathy and diabetes mellitus can also result from mitochondrial disorders.

Children with mitochondrial disorders often have multifocal signs that are intermittent or relapsing–remitting, often in association with intercurrent illness. Many of these disorders were described as clinical syndromes before their genetics were understood. Children with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) present with developmental delay, weakness, and headaches, as well as focal signs that suggest a stroke. Brain imaging indicates that injury does not fit within the usual vascular territories. Children with myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers (MERRF) present with myoclonus and myoclonic seizures as well as intermittent muscle weakness. The ragged red fibers referred to in the name of this disorder are clumps of abnormal mitochondria seen within muscle fibers in sections from a muscle biopsy stained with Gomori trichrome stain. NARP syndrome (neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa), Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS; ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, heart block), Leigh disease (subacute necrotizing encephalomyelopathy), and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) are also defined as relatively homogeneous clinical subgroups, although the age of presentation/diagnosis can vary (Table 616.4 ). It is important to keep in mind that mitochondrial disorders can be difficult to diagnose. They often present with novel combinations of signs and symptoms as a consequence of high mutation rates for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and the severity of disease varies from person to person. Nuclear gene mutations (over 400 possible genes) are more common in the childhood disorders, but mitochondrial gene abnormalities are also seen.

Table 616.4

Clinical Manifestations of Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

| TISSUE | SYMPTOMS/SIGNS | MELAS | MERRF | NARP | KSS | LEIGH | LHON |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | Regression | + | + | + | + | ||

| Seizures | + | + | |||||

| Ataxia | + | + | + | + | |||

| Cortical blindness | + | ||||||

| Deafness | + | + | |||||

| Migraine | + | ||||||

| Hemiparesis | + | ||||||

| Myoclonus | + | + | |||||

| Movement disorder | + | + | |||||

| Nerve | Peripheral neuropathy | + | + | + | + | ||

| Muscle | Ophthalmoplegia | + | |||||

| Weakness | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| RRF on muscle biopsy | + | + | + | ||||

| Ptosis | + | ||||||

| Eye | Pigmentary retinopathy | + | + | ||||

| Optic atrophy | + | + | + | ||||

| Cataracts | |||||||

| Heart | Conduction block | + | + | ||||

| Cardiomyopathy | + | ||||||

| Blood | Anemia | + | |||||

| Lactic acidosis | + | + | + | ||||

| Endocrine | Diabetes mellitus | + | |||||

| Short stature | + | + | + | ||||

| Kidney | Fanconi syndrome | + | + | + |

KSS, Kearns-Sayre syndrome; LHON, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; MELAS, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MERRF, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers; NARP, neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa; RRF, ragged red fibers.

Mitochondrial diseases can be caused by mutations of nuclear DNA (nDNA) or mtDNA (see Chapters 97 , 104 , and 105 ). Oxidative phosphorylation in the respiratory chain is mediated by four intramitochondrial enzyme complexes (complexes I-IV) and two mobile electron carriers (coenzyme Q and cytochrome c) that create an electrochemical proton gradient utilized by complex V (adenosine triphosphate [ATP] synthase) to create the ATP required for normal cellular function. The maintenance of oxidative phosphorylation requires coordinated regulation of nuclear DNA and mtDNA genes. Human mtDNA is a small (16.6 kb), circular, double-stranded molecule that has been completely sequenced and encodes 37 genes including 13 structural proteins, all of which are subunits of the respiratory chain complexes, as well as 2 ribosomal RNAs and 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) needed for translation. The nuclear DNA is responsible for synthesizing approximately 70 subunits, transporting them to the mitochondria via chaperone proteins, ensuring their passage across the inner mitochondrial membrane, and coordinating their correct processing and assembly. Diseases of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation can be divided into three groups: (1) defects of mtDNA, (2) defects of nDNA, and (3) defects of communication between the nuclear and mitochondrial genome. mtDNA is distinct from nDNA for the following five reasons: (1) its genetic code differs from nDNA, (2) it is tightly packed with information because it contains no introns, (3) it is subject to spontaneous mutations at a higher rate than nDNA, (4) it has less efficient repair mechanisms, (5) it is maternally inherited.

Inheritance of mutations present on mtDNA is nonmendelian and can be complex. At fertilization, mtDNA is present in hundreds or thousands of copies per cell and is transmitted by maternal inheritance from her oocyte to all her children, but only her daughters can pass it on to their children. Through the process called heteroplasmy or threshold effect, mtDNA-containing mutations can be distributed unequally between cells in specific tissues. Some cells receive few or no mutant genomes (normal or wild-type homoplasmy), whereas others receive a mixed population of mutant and wild-type mtDNAs (heteroplasmy), and still others receive primarily or exclusively mutant genomes (mutant homoplasmy). The important implications of maternal inheritance and heteroplasmy are as follows: (1) inheritance of the disease is maternal, but both sexes are equally affected; (2) phenotypic expression of an mtDNA mutation depends on the relative proportions of mutant and wild-type genomes, with a minimum critical number of mutant genomes being necessary for disease expression (threshold effect); (3) at cell division, the proportional distribution may shift between daughter cells (mitotic segregation), leading to a corresponding phenotypic change; and (4) subsequent generations are affected at a higher rate than in autosomal dominant diseases. The critical number of mutant mtDNAs required for the threshold effect may vary, depending on the vulnerability of the tissue to impairments of oxidative metabolism as well as on the vulnerability of the same tissue over time that may increase with aging. In contrast to maternally inherited disorders caused by mutations in mtDNA, diseases resulting from defects in nDNA follow mendelian inheritance. Mitochondrial diseases caused by defects in nDNA include defects in substrate transport (plasmalemmal carnitine transporter, carnitine palmitoyltransferases I and II, carnitine acylcarnitine translocase defects), defects in substrate oxidation (pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, pyruvate carboxylase, intramitochondrial fatty acid oxidation defects), defects in the Krebs cycle (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, fumarase, aconitase defects), and defects in the respiratory chain (complexes I-V), including defects of oxidation/phosphorylation coupling (Luft syndrome) and defects in mitochondrial protein transport.

Diseases caused by defects in mtDNA can be divided into those associated with point mutations that are maternally inherited (e.g., LHON, MELAS, MERRF, and NARP/mtLeigh syndromes) and those caused by deletions or duplications of mtDNA that reflect altered communication between the nucleus and the mitochondria (KSS; Pearson syndrome, a rare severe encephalopathy with anemia and pancreatic dysfunction; and progressive external ophthalmoplegia). These disorders can be inherited by sporadic, autosomal dominant or recessive mechanisms, and mutations in multiple genes, including mitochondrial mtDNA polymerase γ catalytic subunit (POLG), have been identified. POLG mutations have also been identified in patients with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome, which causes a refractory seizure disorder and hepatic failure as well as autosomal dominant and recessive progressive external ophthalmoplegia, childhood myocerebrohepatopathy spectrum disorders, myoclonic epilepsy myopathy sensory ataxia syndrome, and POLG -related ataxia neuropathy spectrum disorders. Other genes that regulate the supply of nucleotides for mtDNA synthesis are associated with severe encephalopathy and liver disease, and new disorders are being identified that result from defects in the interactions between mitochondria and their milieu in the cell.

Mitochondrial Myopathy, Encephalopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-Like Episodes

Children with MELAS may be normal for the first several years, but they gradually display delayed motor and cognitive development and short stature. The clinical syndrome is characterized by (1) recurrent stroke-like episodes of hemiparesis or other focal neurologic signs with lesions most commonly seen in the posterior temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes based on cranial CT or MRI evidence of focal brain abnormalities); (2) lactic acidosis or ragged red fibers (RRF), or both; and (3) at least two of the following: focal or generalized seizures, dementia, recurrent migraine headaches, and vomiting. In one series, the onset was before age 15 yr in 62% of patients, and hemianopia or cortical blindness was the most common manifestation. Cerebrospinal fluid protein is often increased. The MELAS 3243 mutation on mtDNA is the most common mutation to produce MELAS and can also be associated with different combinations of exercise intolerance, myopathy, ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiac conduction defects, deafness, endocrinopathy (diabetes mellitus), and proximal renal tubular dysfunction. A number of other mutations have been reported, and two patients have been described with bilateral rolandic lesions and epilepsia partialis continua associated with mtDNA mutations at 10158T>C and 10191T>C. MELAS is a progressive disorder that has been reported in siblings. However, most maternal relatives of MELAS patients are mildly affected or unaffected. MELAS is punctuated with episodes of stroke leading to dementia (see Chapter 629.4 ).

Regional cerebral hypoperfusion can be detected by single-photon emission CT studies and MR spectroscopy can detect focal areas of lactic acidosis in the brain. Neuropathology may show cortical atrophy with infarct-like lesions in both cortical and subcortical structures, basal ganglia calcifications, and ventricular dilation. Muscle biopsy specimens usually show ragged red fibers (RRFs). Mitochondrial accumulations and abnormalities have been shown in smooth muscle cells of intramuscular vessels and of brain arterioles and in the epithelial cells and blood vessels of the choroid plexus, producing a mitochondrial angiopathy. Muscle biochemistry shows complex I deficiency in many cases; however, multiple defects have also been documented involving complexes I, III, and IV. Targeted molecular testing for specific mutations or sequence analysis and mutation scanning are generally used to make a diagnosis of MELAS when clinical evaluation suggests the diagnosis. Because the number of mutant genomes is lower in blood than in muscle, muscle is the preferable tissue for examination. Inheritance is maternal, and there is a highly specific, although not exclusive, point mutation at nt 3243 in the tRNALeu(UUR) gene of mtDNA in approximately 80% of patients. An additional 7.5% have a point mutation at nt 3271 in the tRNALeu(UUR) gene. A third mutation has been identified at nt 3252 in the tRNALeu(UUR) gene. The prognosis in patients with the full syndrome is poor. Therapeutic trials reporting some benefit have included corticosteroids, coenzyme Q10, nicotinamide, carnitine, creatine, riboflavin, and various combinations of these; L -arginine and preclinical studies reported some success with resveratrol and also with a new agent, EPI-743, a coenzyme Q10 analogue compound.

Myoclonic Epilepsy and Ragged Red Fibers

MERRF syndrome is characterized by progressive myoclonic epilepsy, mitochondrial myopathy, and cerebellar ataxia with dysarthria and nystagmus. Onset may be in childhood or in adult life, and the course may be slowly progressive or rapidly downhill. Other features include dementia, sensorineural hearing loss, optic atrophy, peripheral neuropathy, and spasticity. Because some patients have abnormalities of deep sensation and pes cavus, the condition may be confused with Friedreich ataxia. A significant number of patients have a positive family history and short stature. This condition is maternally inherited.

Pathologic findings include elevated serum lactate concentrations, RRF on muscle biopsy, and marked neuronal loss and gliosis affecting, in particular, the dentate nucleus and inferior olivary complex with some dropout of Purkinje cells and neurons of the red nucleus. Pallor of the posterior columns of the spinal cord and degeneration of the gracile and cuneate nuclei occur. Muscle biochemistry has shown variable defects of complex III, complexes II and IV, complexes I and IV, or complex IV alone. More than 80% of cases are caused by a heteroplasmic G to A point mutation at nt 8344 of the tRNALys gene of mtDNA. Additional patients have been reported with a T to C mutation at nt 8356 in the tRNALys gene. Targeted mutation analysis or mutation analysis after sequencing of the mitochondrial genome is used to diagnose MERRF.

There is no specific therapy, although coenzyme Q10 appeared to be beneficial in a mother and daughter with the MERRF mutation. The anticonvulsant levetiracetam is reported to help reduce myoclonus and myoclonic seizures in this disorder.

Neuropathy, Ataxia, and Retinitis Pigmentosa (NARP) Syndrome

This maternally inherited disorder presents with either Leigh syndrome or with neurogenic weakness and NARP syndrome, as well as seizures. It is caused by a point mutation at nt 8993 within the ATPase subunit 6 gene. The severity of the disease presentation appears to have close correlation with the percentage of mutant mtDNA in leukocytes. Two clinical patterns are seen in patients with NARP syndrome: (1) neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa, dementia, and ataxia, and (2) severe infantile encephalopathy resembling Leigh syndrome with lesions in the basal ganglia on MRI.

Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON)

LHON is characterized by onset usually between the ages of 18 and 30 yr of acute or subacute visual loss caused by severe bilateral optic atrophy, although children as young as 5 yr have been reported to have LHON. Three mtDNA mutations account for most cases of LHON and at least 85% of patients are young men. An X-linked factor may modulate the expression of the mtDNA point mutation. The classic ophthalmologic features include circumpapillary telangiectatic microangiopathy and pseudoedema of the optic disc. Variable features may include cerebellar ataxia, hyperreflexia, Babinski sign, psychiatric symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, or cardiac conduction abnormalities (preexcitation syndrome). Some cases are associated with widespread white matter lesions as seen with multiple sclerosis. Lactic acidosis and RRF tend to be conspicuously absent in LHON. More than 11 mtDNA point mutations have been described, including a usually homoplasmic G to A transition at nt 11,778 of the ND4 subunit gene of complex I. The latter mutation leads to replacement of a highly conserved arginine residue by histidine at the 340th amino acid and accounts for 50–70% of cases in Europe and more than 90% of cases in Japan. Certain LHON pedigrees with other point mutations are associated with complex neurologic disorders and may have features in common with MELAS syndrome and with infantile bilateral striatal necrosis. One family has been reported with pediatric onset of progressive generalized dystonia with bilateral striatal necrosis associated with a homoplasmic G14459A mutation in the mtDNA ND6 gene, which is also associated with LHON alone and LHON with dystonia. Idebenone and EPI-743 have been studied for treatment of this disorder.

Kearns-Sayre Syndrome (KSS)

KSS is a characteristic multiorgan disorder involving external ophthalmoplegia, heart block, and retinitis pigmentosa with onset before age 20 yr caused by single deletions in mtDNA. There must also be at least one of the following: heart block, cerebellar syndrome, or cerebrospinal fluid protein > 100 mg/dL. Other nonspecific but common features include dementia, sensorineural hearing loss, and multiple endocrine abnormalities, including short stature, diabetes mellitus, and hypoparathyroidism. The prognosis is guarded, despite placement of a pacemaker, and progressively downhill, with death resulting by the 3rd or 4th decade. Unusual clinical presentations can include renal tubular acidosis and Lowe syndrome. There are also a few overlap cases of children with KSS and stroke-like episodes. Muscle biopsy shows RRF and variable cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-negative fibers. Most patients have mtDNA deletions, and some have duplications. These may be new mutations accounting for the generally sporadic nature of KSS. A few pedigrees have shown autosomal dominant transmission. Patients should be monitored closely for endocrine abnormalities, which can be treated. Coenzyme Q10 is reported anecdotally to have some beneficial effect; a positive effect of folinic acid for low folate levels has been reported. A report of positive effects of a cochlear implant for deafness is also reported.

Sporadic progressive external ophthalmoplegia with ragged red fibers is a clinically benign condition characterized by adolescent or young adult–onset ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, and proximal limb girdle weakness. It is slowly progressive and compatible with a relatively normal life. The muscle biopsy material demonstrates RRF and COX-negative fibers. Approximately 50% of patients with progressive external ophthalmoplegia have mtDNA deletions, and there is no family history.

Reversible Infantile Cytochrome C Oxidase Deficiency Myopathy

Mutations in mtDNA are also responsible for a reversible form of severe neuromuscular weakness and hypotonia in infants that is the result of a maternally inherited homoplasmic m.14674T>C mt-tRNAGlu mutation associated with a deficiency of COX. Affected children present within the first few weeks of life with hypotonia, severe muscle weakness, and very elevated serum lactate levels, and they often require mechanical ventilation. However, feeding and psychomotor development are not affected. Muscle biopsies taken from these children in the neonatal period show RRF and deficient COX activity, but these findings disappeared within 5-20 mo when the infants recovered spontaneously. It is difficult to distinguish these infants from those with lethal mitochondrial disorders without waiting for them to improve. The mechanism for this recovery is not established, but it may reflect a developmental switch in mitochondrial RNAs later in infancy. This reversible disorder is observed only in COX deficiency associated with the 14674T>C mt-tRNAGlu mutation, so it is suggested that infants with this type of severe weakness in the neonatal period be tested for this mutation to help with prognosis.

Leigh Disease (Subacute Necrotizing Encephalomyopathy)

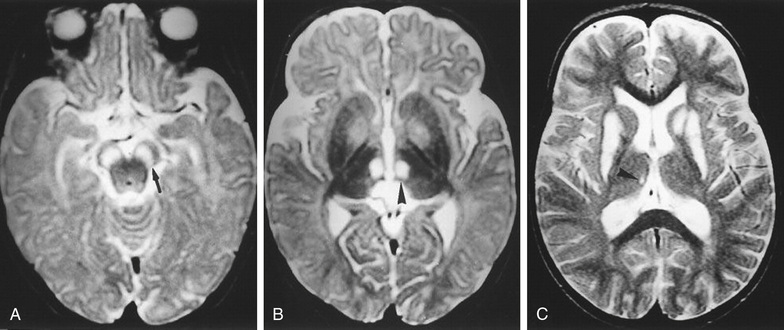

Leigh disease is a progressive degenerative disorder presenting in infancy with feeding and swallowing problems, vomiting, and failure to thrive associated with lactic acidosis and lesions seen in the brainstem and/or basal ganglia on MRI (Table 616.5 ). There are several genetically determined causes of Leigh disease that result from nuclear DNA mutations in genes that code for components of the respiratory chain: pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency, complex I or II deficiency, complex IV (COX) deficiency, complex V (ATPase) deficiency, and deficiency of coenzyme Q10. These defects may occur sporadically or be inherited by autosomal recessive transmission, as in the case of COX deficiency; by X-linked transmission, as in the case of pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 α deficiency; or by maternal transmission, as in complex V (ATPase 6 nt 8993 mutation) deficiency. Approximately 30% of cases are caused by mutations in mtDNA. Delayed motor and language milestones may be evident, and generalized seizures, weakness, hypotonia, ataxia, tremor, pyramidal signs, and nystagmus are prominent findings. Intermittent respirations with associated sighing or sobbing are characteristic and suggest brainstem dysfunction. Some patients have external ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, retinitis pigmentosa, optic atrophy, and decreased visual acuity. Abnormal results on CT or MRI scan consist of bilaterally symmetric areas of low attenuation in the basal ganglia and brainstem as well as elevated lactic acid on MR spectroscopy (Fig. 616.4 ). Pathologic changes consist of focal symmetric areas of necrosis in the thalamus, basal ganglia, tegmental gray matter, periventricular and periaqueductal regions of the brainstem, and posterior columns of the spinal cord. Microscopically, these spongiform lesions show cystic cavitation with neuronal loss, demyelination, and vascular proliferation. Elevations in serum and CSF lactate levels are characteristic, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, hepatic failure, and rental tubular dysfunction can occur. The overall outlook is poor, but a few patients experience prolonged periods of remission. There is no definitive treatment for the underlying disorder, but a range of vitamins, including riboflavin, thiamine, and coenzyme Q10, are often given to try to improve mitochondrial function. Biotin, creatine, succinate, idebenone, and EPI-743, as well as a high-fat diet, have also been used. Phenobarbital and valproic acid should be avoided because of their inhibitory effect on the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

Table 616.5

Clinical Features of Congenital Leigh Syndrome or Leigh-like Syndrome

| NEUROLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS |

| Brainstem |

| Other Cerebral Manifestations |

| Peripheral Nervous System Manifestations |

| NONNEUROLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS |

| Dysmorphic Features |

| Others |

From Finsterer J: Leigh and Leigh-like syndrome in children and adults, Pediatr Neurol 39:223-235, 2008, Table 1.

Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Syndrome

Mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome is a group of autosomal recessive disorders that cause a significant drop in mitochondrial DNA in muscle, the liver, and the brain (Table 616.6 ). The condition is usually fatal in infancy, although some children have survived into the teenage years.

Table 616.6

Manifestations of Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Syndrome

| MUTATED GENE | SYNDROME | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS | mtDNA DEPLETION | MULTIPLE DELETIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLG1 | HC, AHS | Brain, liver | x | x |

| DGUOK | HC | Brain, liver | x | x |

| TK2 | M | Muscle | x | x |

| MPV17 | HC | Cerebrum, liver | x | x |

| TYMP | MNGIE | Nerve, muscle, GI, brain | x | x |

| SUCLA2 | EM | Brain, muscle | x | |

| SUCLG1 | EM | Brain, muscle | x | |

| RRM2B | M | Muscle | x | x |

| PEO1 /twinkle | HC, IOSCA, MIRAS | Brain, liver | x | x |

AHS, Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome; EM, encephalomyopathic form; GI, gastrointestinal; HC, hepatocerebral form; IOSCA, infantile-onset spinocerebellar ataxia; M, myopathic form; MIRAS, mitochondrial recessive ataxia syndrome; MNGIE, mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy.

From Finsterer J, Ahting U: Mitochondrial depletion syndromes in children and adults, Can J Neurol Sci 40:635-644, 2013, Table 2.

Reye Syndrome

This encephalopathy, which has become uncommon, is associated with pathologic features characterized by fatty degeneration of the viscera (microvesicular steatosis) and mitochondrial abnormalities and biochemical features consistent with a disturbance of mitochondrial metabolism (see Chapter 388 ).

Recurrent Reye-like syndrome is encountered in children with genetic defects of fatty acid oxidation, such as deficiencies of the plasmalemmal carnitine transporter, carnitine palmitoyltransferases I and II, carnitine acylcarnitine translocase, medium- and long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, multiple acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, and long-chain L-3 hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase or trifunctional protein. These disorders are manifested by recurrent hypoglycemic and hypoketotic encephalopathy, and they are inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Other potential inborn errors of metabolism presenting with Reye syndrome include urea cycle defects (ornithine transcarbamylase, carbamyl phosphate synthetase) and certain of the organic acidurias (glutaric aciduria type I), respiratory chain defects, and defects of carbohydrate metabolism (fructose intolerance).

Bibliography

Bianchi MC, Sgandurra G, Tosetti M, et al. Brain magnetic resonance in the diagnostic evaluation of mitochondrial encephalopathies. Biosci Rep . 2007;27:69–95.

Chicani CF, Chu ER, Miller G, Comparing EPI. 743 treatment in siblings with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mt14484 mutation. Can J Ophthalmol . 2013;48(5):e130–e133.

Cohen BH, Chinnery PF, Copeland WC. POLG-related disorders. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. GeneReviews [internet], Seattle (WA), 1993-2014 . University of Washington: Seattle; 2010 [March 16; [updated October 11, 2012].

Crest C, Dupont S, Leguern E, et al. Levetiracetam in progressive myoclonic epilepsy: an exploratory study. Neurology . 2004;62:640–643.

DiMauro S, Schon EA, Carelli V, et al. The clinical maze of mitochondrial neurology. Nat Rev Neurol . 2013;9:429–444.

Donato S. Multisystem manifestations of mitochondrial disorders. J Neurol . 2009;256:693–710.

Enns GM, Kinsman SL, Perlman SL, et al. Initial experience in the treatment of inherited mitochondrial disease with EPI-743. Mol Genet Metab . 2012;105(1):91–102.

Eom S, Lee HN, Lee S, et al. Cause of death in children with mitochondrial diseases. Pediatr Neurol . 2017;66:82–88.

Finsterer J, Ahting U. Mitochondrial depletion syndromes in children and adults. Can J Neurol Sci . 2013;40:635–644.

Finsterer J. Leigh and Leigh-like syndrome in children and adults. Pediatr Neurol . 2008;39:223–235.

Finsterer J. Management of mitochondrial stroke-like-episodes. Eur J Neurol . 2009;16:1178–1184.

Fryer RH, Bain J, De Vivo D. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes: a case report and critical reappraisal of treatment options. Pediatr Neurol . 2016;56:59–61.

Horvath R, Kemp JP, Tuppen HAL, et al. Molecular basis of infantile reversible cytochrome c oxidase deficiency myopathy. Brain . 2009;132:3165–3174.

Kitamura M, Yatsuga S, Abe T, et al. L-arginine intervention at hyper-acute phase protects the prolonged MRI abnormality in MELAS. J Neurol . 2016;263(8):1666–1668.

Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, et al. L-arginine improves the symptoms of stroke-like episodes in MELAS. Neurology . 2005;64:710–712.

Martinelli D, Catteruccia M, Piemonte F, et al. EPI-743 reverses the progression of the pediatric mitochondrial disease–genetically defined leigh syndrome. Mol Genet Metab . 2012;107(3):383–388.

Oldfors A, Tulinius M. Mitochondrial encephalopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol . 2003;62:217–227.

Pfeffer G, Majamaa K, Turnbull DM, et al. Treatment for mitochondrial disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2012;(4) [CD004426].

Scarpelli M, Todeschini A, Volonghi I, et al. Mitochondrial diseases: advances and issues. Appl Clin Genet . 2017;10:21–26.

Taanman JW, Bodnar AG, Cooper JM, et al. Molecular mechanisms in mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet . 1997;6(6):935–942.

Tein I. Impact of fatty acid oxidation disorders in child neurology: from reye syndrome to Pandora's box. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2015;57(4):304–306.

Wani AA, Ahanger SH, Bapat SA, et al. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences in childhood encephalomyopathies reveals new disease-associated variants. PLoS ONE . 2007;2:e942.

Werner KG, Morel CF, Benseler SM, et al. Rolandic mitochondrial encephalomyelopathy and MT-ND3 mutations. Pediatr Neurol . 2009;41:27–33.

Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Nishioka J, et al. MELAS: a nationwide prospective cohort study of 96 patients in Japan. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2012;1820:619–624.

Other Encephalopathies

Michael V. Johnston

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Encephalopathy

Encephalopathy is an unfortunate and common manifestation in infants and children with HIV infection (see Chapter 302 ).

Lead Encephalopathy

See Chapter 739 .

Burn Encephalopathy

An encephalopathy develops in approximately 5% of children with significant burns in the first several weeks of hospitalization (see Chapter 92 ). There is no single cause of burn encephalopathy, but rather it is caused by a combination of factors that include anoxia (smoke inhalation, carbon monoxide poisoning, laryngospasm), electrolyte abnormalities, bacteremia and sepsis, cortical vein thrombosis, a concomitant head injury, cerebral edema, drug reactions, and emotional distress. Seizures are the most common clinical manifestation of burn encephalopathy, but altered states of consciousness, hallucinations, and coma may also occur. Management of burn encephalopathy is directed to a search for the underlying cause and treatment of hypoxemia, seizures, specific electrolyte abnormalities, or cerebral edema. The prognosis for complete neurologic recovery is generally excellent, particularly if seizures are the primary abnormality.

Hypertensive Encephalopathy

Hypertensive encephalopathy is most commonly associated with renal disease in children; including acute glomerulonephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, and end-stage renal disease (see Chapters 472 and 550 ). In some cases, hypertensive encephalopathy is the initial manifestation of underlying renal disease. Marked systemic hypertension produces vasoconstriction of the cerebral vessels, which leads to vascular permeability, causing areas of focal cerebral edema and hemorrhage. The onset may be acute, with seizures and coma, or more indolent, with headache, drowsiness and lethargy, nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, transient cortical blindness, and hemiparesis. Examination of the eyegrounds may be nondiagnostic in children, but papilledema and retinal hemorrhages may occur. MRI often shows increased signal intensity in the occipital lobes on T2-weighted images, which is known as posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES) and may be confused with cerebral infarctions. These high-signal areas may appear in other regions of the brain as well. PRES may also be seen in children without hypertension. In all circumstances, PRES manifests with generalized motor seizures, headache, mental status changes, and visual disturbances. CT may be normal in PRES; MRI is the study of choice. Treatment is directed at restoration of a normotensive state and control of seizures with appropriate anticonvulsants.

Radiation Encephalopathy

Acute radiation encephalopathy is most likely to develop in young patients who have received large daily doses of radiation. Excessive radiation injures vessel endothelium, resulting in enhanced vascular permeability, cerebral edema, and numerous hemorrhages. The child may suddenly become irritable and lethargic, complain of headache, or present with focal neurologic signs and seizures. Patients occasionally develop hemiparesis as the result of an infarct secondary to vascular occlusion of the cerebral vessels. Steroids are often beneficial in reducing the cerebral edema and reversing the neurologic signs. Late-radiation encephalopathy is characterized by headaches and slowly progressive focal neurologic signs, including hemiparesis and seizures. Exposure of the brain to radiation for treatment of childhood cancer increases the risk of later cerebrovascular disease, including stroke, moyamoya disease, aneurysm, vascular malformations, mineralizing microangiopathy, and stroke-like migraines. Some children with acute lymphocytic leukemia treated with a combination of intrathecal methotrexate and cranial irradiation develop neurologic signs months or years later; signs consist of increasing lethargy, loss of cognitive abilities, dementia, and focal neurologic signs and seizures (see Chapter 521 ). The CT scan shows calcifications in the white matter, and the postmortem examination demonstrates a necrotizing encephalopathy. This devastating complication of the treatment of leukemia has prompted reevaluation and reduction in the use of cranial radiation in the treatment of these children.

Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy

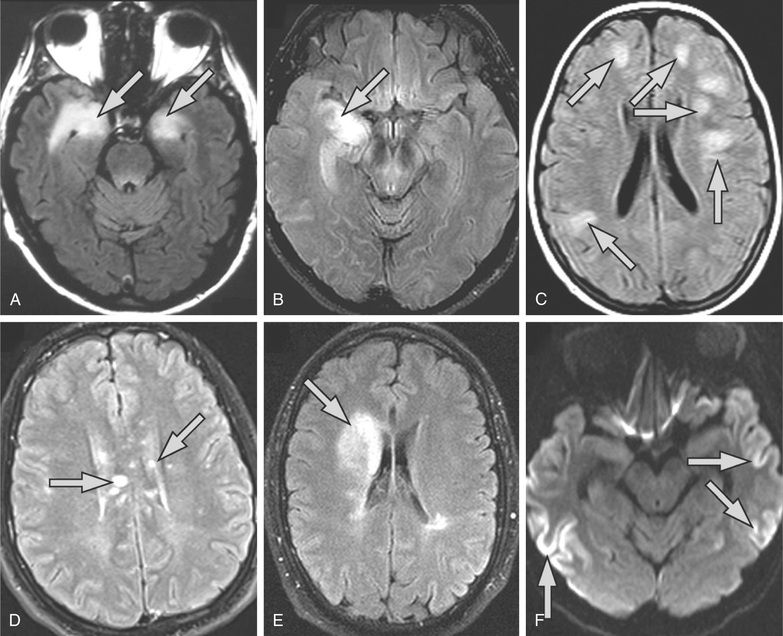

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE) is a rare, severe encephalopathy seen more commonly in Asian countries. It is thought to be triggered by a viral infection (influenza, HHV-6) in a genetically susceptible host. Table 616.7 lists the diagnostic criteria. The elevation of hepatic enzymes without hyperammonemia is a unique feature. A familial or recurrent form is associated with mutations in the RANBP2 gene and is designated ANE1. MRI findings are characterized by symmetric lesions that must be present in the thalami (Fig. 616.5 ). The prognosis is usually poor; however, some patients have responded to steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Table 616.7

Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy of Childhood

Modified from Hoshino A, Saitoh M, Oka, et al: Epidemiology of acute encephalopathy in Japan, with emphasis on the association of viruses and syndromes, Brain Dev 34:337-343, 2012, Table 1.

Cystic Leukoencephalopathy

An autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations of RNASET2 proteins produces a brain MRI study that closely resembles congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Cystic leukoencephalopathy is manifest as a static encephalopathy without megalencephaly.

Bibliography

Agarwal A, Kapur G, Altinok D. Childhood posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: magnetic resonance imaging findings with emphasis on increased leptomeningeal FLAIR signal. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28(6):638–643.

Bergamino L, Capra V, Biancheri R, et al. Immunomodulatory therapy in recurrent acute necrotizing encephalopathy ANE1: is it useful? Brain Dev . 2012;34:384–391.

Britton PN, Dale RC, Blyth CC, et al. ACE study investigators and PAEDS network: Influenza-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy identified by the Australian childhood encephalitis study 2013-2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2017;36(11):1021–1026.

Donmez FY, Guleryuz P, Agildere M. MRI findings in childhood PRES: what is different than the adults? Clin Neuroradiol . 2016;26(2):209–213.

Gaynon PS, Angiolillo AL, Carroll WL, et al. Long-term results of the children's cancer group studies for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia 1983–2002: a children's oncology group report. Leukemia . 2010;24:285–297.

Henneke M, Dickmann S, Ohlenbusch A, et al. RNASET2-deficient cystic leukoencephalopathy resembles congenital cytomegalovirus brain infection. Nat Genet . 2009;41:773–775.

Hoshino A, Saitoh M, Oka A, et al. Epidemiology of acute encephalopathy in Japan, with emphasis on the association of viruses and syndromes. Brain Dev . 2012;34:337–343.

Kastrup O, Gerwig M, Frings M, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): electroencephalographic findings and seizure patterns. J Neurol . 2012;259:1383–1389.

Lee VH, Wijidicks EFM, Manno EM, et al. Clinical spectrum of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. Arch Neurol . 2008;65:205–210.

Loh NR, Appleton DB. Untreated recurrent acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with RANBP2 mutation, and normal outcome in a caucasian boy. Eur J Pediatr . 2010;169:1299–1302.

Morris B, Partap S, Yeom K, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in childhood cancer survivors: a Children's oncology group report. Neurology . 2009;73:1906–1913.

Morris EB, Laninigham FH, Sandlund JT, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2007;48:152–159.

Neilson DE. The interplay of infection and genetics in acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2010;22:751–757.

Nielson DE, Adams MD, Orr C, et al. Infection-triggered familial or recurrent cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy caused by mutation in a component of the nuclear pore, RANBP2. Am J Hum Genet . 2009;84:44–51.

Onder AM, Lopez R, Teomete U, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in the pediatric renal population. Pediatr Nephrol . 2007;22:1921–1929.

Prasad N, Gulati S, Gupta RK, et al. Spectrum of radiological changes in hypertensive children with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy. Br J Radiol . 2007;80:422–429.

Wong AM, Simon EM, Zimmerman RA, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: correlation of MR findings and clinical outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2006;27:1919–1923.

Yamamoto H, Natsume J, Kidokoro H, et al. Clinical and neuroimaging findings in children with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol . 2015;19(6):672–678.

Autoimmune Encephalitis

Thaís Armangué, Josep O. Dalmau

Keywords

- autoimmune

- antibodies

- encephalitis

- NMDA receptor

- GABAAR receptor

- glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65)

- VGKC-complex

- anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis

- limbic encephalitis

- acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD)

- aquaporin 4

- myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)

- Hashimoto encephalopathy

- opsoclonus–myoclonus

- Bickerstaff encephalitis

- chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS)

- Rasmussen encephalitis

- fever-induced refractory epileptic encephalopathy syndrome (FIRES)

- rapid-onset obesity with hypothalamic dysfunction, hypoventilation, and autonomic dysregulation (ROHHAD)

- basal ganglia encephalitis

- pseudomigraine syndrome with CSF pleocytosis

- headache with neurologic deficits and CSF lymphocytosis (HaNDL)

- ophthalmoplegic migraine

- recurrent cranial neuralgia

- progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM)

Autoimmune encephalitis comprises an expanding group of clinical syndromes that can occur at all ages (<1 yr to adult) but preferentially affect younger adults and children (Table 616.8 ). Some of these disorders are associated with antibodies against neuronal cell surface proteins and synaptic receptors involved in synaptic transmission, plasticity, or neuronal excitability. The syndromes vary according to the associated antibody, with phenotypes that resemble those in which the function of the target antigen is pharmacologically or genetically modified.

Table 616.8

Autoimmune Encephalitis in Children

| DISEASE | ANTIBODIES AND/OR MECHANISMS | SYNDROME | ANCILLARY TEST | TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-NMDAR encephalitis | Antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDAR. In children, most cases are idiopathic. In a subgroup of patients, the disease is triggered by the presence of a tumor. In another subgroup, the disease is triggered by HSV encephalitis. | Psychiatric symptoms, decreased verbal output, sleep disorder (mainly insomnia), seizures, dyskinesias (orofacial, limbs), dystonia, rigidity and other abnormal movements, autonomic dysfunction, hypoventilation |

EEG: almost always abnormal (epileptic and/or slow activity). In some patients it shows the pattern of extreme delta brush. Brain MRI: nonspecific abnormal findings in ~ 35% CSF: pleocytosis and/or increased proteins in ~ 80% |

80% substantial or complete recovery after immunotherapy and tumor removal (if appropriate). About 50% of patients need second-line immunotherapies.* Relapses in ~ 15% of patients. Worse outcome when post-HSE |

| Encephalitis associated with GABAA R antibodies |

Antibodies against α1, β3, or γ2 subunits of the GABAA R. ~40% of adults have an underlying tumor (thymoma). Children usually do not have tumor association. |

Refractory seizures, epilepsia partialis continua. Patients may develop limb or orofacial dyskinesias. |

EEG: almost always abnormal; frequent epileptic activity MRI: multifocal corticosubcortical FLAIR/T2 hyperintensities in 77% of patients CSF: pleocytosis and/or increased proteins |

80% show moderate or good recovery after immunotherapy. |

| Encephalitis with mGluR5 antibodies (Ophelia syndrome) |

Antibodies against mGluR5 Frequent association with Hodgkin lymphoma |

Abnormal behavior, seizures, memory deficits |

EEG: frequently abnormal with nonspecific findings MRI: normal or nonspecific findings CSF: frequent pleocytosis and/or increased proteins |

Good recovery after tumor treatment and immunotherapy |

| Other autoimmune encephalitis (very infrequent in children) |

Antibodies against neuronal cell surface (GABAB R, DPPX, GlyR) or intraneuronal antigens (Hu, Ma2, GAD65 amphiphysin) All these antibodies rarely associate with tumors in children. |

The syndrome varies depending on the autoantibody, and the phenotypes are often different from those reported in adults. GABAB R: encephalitis, seizures, cerebellar ataxia DPPX: CNS hyperexcitability, PERM GlyR: PERM or stiff person syndrome Hu: brainstem or limbic encephalitis Ma2: encephalitis, diencephalic encephalitis (only in adults) GAD65: limbic encephalitis, epilepsy |

MRI: variable changes depending on the syndrome CSF: frequent pleocytosis and/or increased proteins |

Disorders with antibodies against cell surface antigens are substantially more responsive to immunotherapy than those with antibodies against intracellular antigens. |

| ADEM | 50–60% of patients with ADEM harbor MOG antibodies. | Seizures, motor deficits, ataxia, or visual dysfunction accompanied by encephalopathy |

MRI with T2/FLAIR large, hazy abnormalities, with or without involvement of the deep gray matter CSF: frequent pleocytosis and/or increased proteins |

In ~ 90% of patients, the disease is monophasic and shows good response to steroids. Some patients develop relapsing disease (with prolonged detection of MOG antibodies). |

| NMOSD | Patients can have AQP4 or MOG antibodies; some patients are seronegative. |

Typical involvement of optic nerves and spinal cord Encephalopathy in the context of diencephalic or area postrema syndromes |

Characteristic involvement of brain areas rich in AQP4 (periaqueductal gray matter, hypothalamus, optic nerve and central involvement of the spinal cord) | High risk of relapses and long-term disability. Requires chronic immunotherapy. Patients with MOG antibodies have better long-term outcome than those with AQP4 antibodies or seronegative cases. |

| Opsoclonus–myoclonus and other cerebellar–brainstem encephalitis | Most patients do not have detectable autoantibodies (a few patients have Hu antibodies). Neuroblastoma occurs in 50% of children < 2 yr old; teratoma in teenagers and young adults. | Opsoclonus often accompanied by irritability, ataxia, falling, myoclonus, tremor, and drooling |

MRI: usually normal; it may show cerebellar atrophy over time. EEG: Normal CSF: may be normal or show abnormalities suggesting B-cell activation |

Neuroblastoma treatment (if it applies) Partial neurologic response to immunotherapy in many young children regardless of presence or absence of neuroblastoma. (Better outcomes if aggressive immunotherapy is used.) Good response to treatment in teenagers with teratoma-associated opsoclonus |

| Bickerstaff encephalitis |

GQ1b antibodies (~65%, nonspecific for this disorder) |

Ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and decreased level of consciousness. Frequent hyperreflexia. Patients may develop hyporeflexia and overlap with Miller-Fisher syndrome. |

MRI: abnormal in ~30% (T2-signal abnormalities in the brainstem, thalamus, and cerebellum) Nerve conduction studies: abnormal in ~ 45% (predominant axonal degeneration, and less often demyelination) |

Good response to steroids, IVIG, or plasma exchange |

| Hashimoto encephalitis |

TPO antibodies † (nonspecific for this disorder) |

Stroke-like symptoms, tremor, myoclonus, aphasia, seizures, ataxia, sleep and behavioral problems |

48% hypothyroidism, MRI often normal EEG: slow activity CSF: elevated protein |

Steroid-responsive. Partial responses are frequent. |