Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Ericka V. Hayes

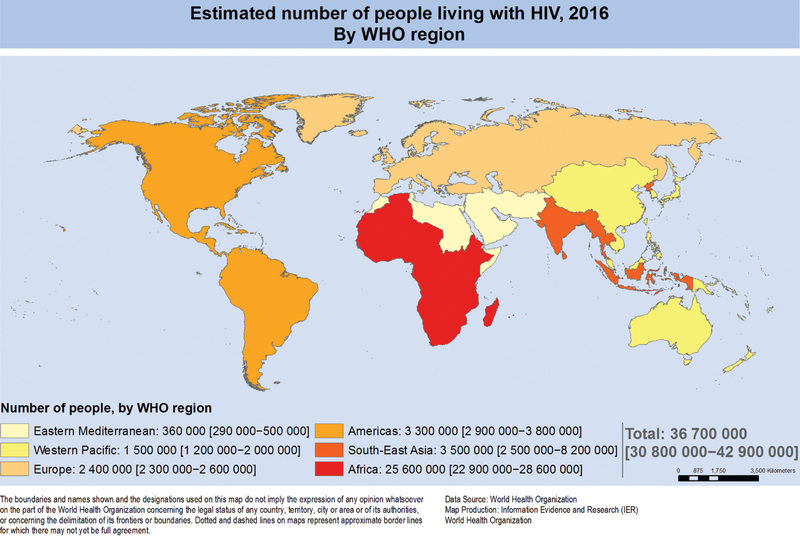

Advances in research and major improvements in the treatment and management of HIV infection have brought about a substantial decrease in the incidence of new HIV infections and AIDS in children. Globally, from 2000 to 2015, there has been an estimated 70% decline in new infections in children aged 0-14 yr, largely the result of antiretroviral treatment (ART) of HIV-infected pregnant women for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Seventy percent of adults and children with HIV infection live in sub-Saharan Africa, where the disease continues to have a devastating impact (Fig. 302.1 ). Children experience more rapid disease progression than adults, with up to half of untreated children dying within the first 2 yr of life. This rapid progression is correlated with a higher viral burden and faster depletion of infected CD4 lymphocytes in infants and children than in adults. Accurate diagnostic tests and the early initiation of potent drugs to inhibit HIV replication have dramatically increased the ability to prevent and control this disease.

Etiology

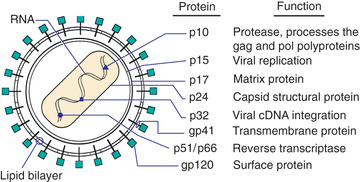

HIV-1 and HIV-2 are members of the Retroviridae family and belong to the Lentivirus genus, which includes cytopathic viruses causing diverse diseases in several animal species. The HIV-1 genome contains two copies of single-stranded RNA that is 9.2 kb in size. At both ends of the genome there are identical regions, called long terminal repeats, which contain the regulation and expression genes of HIV. The remainder of the genome includes three major sections: the GAG region, which encodes the viral core proteins (p24 [capsid protein: CA], p17 [matrix protein: MA], p9, and p6, which are derived from the precursor p55); the POL region, which encodes the viral enzymes (i.e., reverse transcriptase [p51], protease [p10], and integrase [p32]); and the ENV region, which encodes the viral envelope proteins (gp120 and gp41, which are derived from the precursor gp160). Other regulatory proteins, such as transactivator of transcription (tat: p14), regulator of virion (rev: p19), negative regulatory factor (nef: p27), viral protein r (vpr: p15), viral infectivity factor (vif: p23), viral protein u (vpu in HIV-1: P16), and viral protein x (vpx in HIV-2: P15), are involved in transactivation, viral messenger RNA expression, viral replication, induction of cell cycle arrest, promotion of nuclear import of viral reverse transcription complexes, downregulation of the CD4 receptors and class I major histocompatibility complex, proviral DNA synthesis, and virus release and infectivity (Fig. 302.2 ).

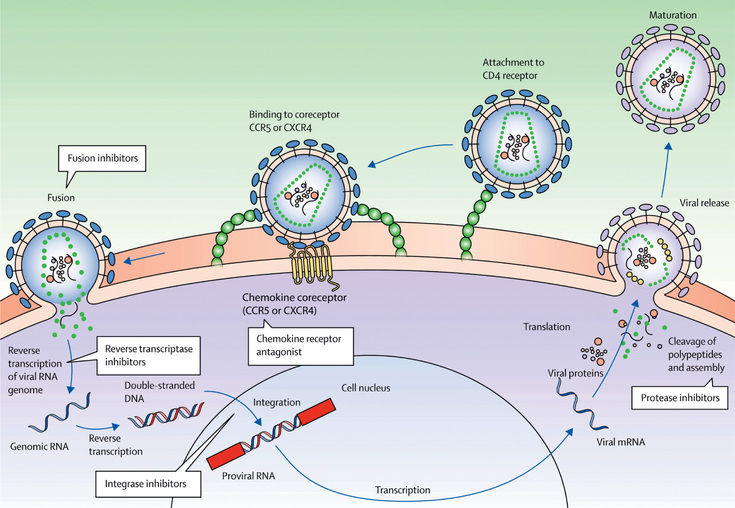

The HIV tropism to the target cell is determined by its envelope glycoprotein (Env). Env consists of two components, namely, the surface, heavily glycosylated subunit, gp120 protein and the associated transmembrane subunit glycoprotein gp41. Both gp120 and gp41 are produced from the precursor protein gp160. The glycoprotein gp41 is very immunogenic and is used to detect HIV-1 antibodies in diagnostic assays; gp120 is a complex molecule that includes the highly variable V3 loop. This region is immunodominant for neutralizing antibodies. The heterogeneity of gp120 presents major obstacles in establishing an effective HIV vaccine. The gp120 glycoprotein also carries the binding site for the CD4 molecule, the most common host cell surface receptor of T lymphocytes. This tropism for CD4+ T cells is beneficial to the virus because of the resulting reduction in the effectiveness of the host immune system. Other CD4-bearing cells include macrophages and microglial cells. The observations that CD4− cells are also infected by HIV and that some CD4+ T cells are resistant to such infections suggests that other cellular attachment sites are needed for the interaction between HIV and human cells. Several chemokines serve as coreceptors for the envelope glycoproteins, permitting membrane fusion and entry into the cell. Most HIV strains have a specific tropism for one of the chemokines, including the fusion-inducing molecule CXCR-4, which acts as a coreceptor for HIV attachment to lymphocytes, and CCR-5, a β chemokine receptor that facilitates HIV entry into macrophages. Several other chemokine receptors (CCR-3) have also been shown in vitro to serve as virus coreceptors. Other mechanisms of attachment of HIV to cells use nonneutralizing antiviral antibodies and complement receptors. The Fab portion of these antibodies attaches to the virus surface, and the Fc portion binds to cells that express Fc receptors (macrophages, fibroblasts), thus facilitating virus transfer into the cell. Other cell-surface receptors, such as the mannose-binding protein on macrophages or the DC-specific, C-type lectin (DC-SIGN) on dendritic cells, also bind to the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein and increase the efficiency of viral infectivity. Cell-to-cell transfer of HIV without formation of fully formed particles is a more rapid mechanism of spreading the infection to new cells than is direct infection by the virus.

Following viral attachment, gp120 and the CD4 molecule undergo conformational changes, and gp41 interacts with the fusion receptor on the cell surface (Fig. 302.3 ). Viral fusion with the cell membrane allows entry of viral RNA into the cell cytoplasm. This process involves accessory viral proteins (nef, vif) and binding of cyclophilin A (a host cellular protein) to the capsid protein (p24). The p24 protein is involved in virus uncoating, recognition by restriction factors, and nuclear importation and integration of the newly created viral DNA. Viral DNA copies are then transcribed from the virion RNA through viral reverse transcriptase enzyme activity, which builds the first DNA strand from the viral RNA and then destroys the viral RNA and builds a second DNA strand to produce double-stranded circular DNA. The HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is error prone and lacks error-correcting mechanisms. Thus, many mutations arise, creating a wide genetic variation in HIV-1 isolates even within an individual patient. Many of the drugs used to fight HIV infection were designed to block the reverse transcriptase action. The circular DNA is transported into the cell nucleus, using viral accessory proteins such as vpr, where it is integrated (with the help of the virus integrase) into the host chromosomal DNA and referred to as the provirus. The provirus has the advantage of latency, because it can remain dormant for extended periods, making it extremely difficult to eradicate. The infected CD4+ T cells that survive long enough to revert to resting memory state become the HIV latent reservoir where the virus persists indefinitely even in patients who respond favorably to potent antiretroviral therapy. The molecular mechanisms of this latency are complex and involve unique biologic properties of the latent provirus (e.g., absence of tat, epigenetic changes inhibiting HIV gene expression) and the nature of the cellular host (e.g., absence of transcription factors such as nuclear factor κB). Integration usually occurs near active genes, which allow a high level of viral production in response to various external factors such as an increase in inflammatory cytokines (by infection with other pathogens) and cellular activation. Anti-HIV drugs that block the integrase enzyme activity have been developed. Depending on the relative expression of the viral regulatory genes (tat, rev, nef), the proviral DNA may encode production of the viral RNA genome, which, in turn, leads to production of viral proteins necessary for viral assembly.

HIV-1 transcription is followed by translation. A capsid polyprotein is cleaved to produce the virus-specific protease (p10), among other products. This enzyme is critical for HIV-1 assembly because it cleaves the long polyproteins into the proper functional pieces. Several HIV-1 antiprotease drugs have been developed, targeting the increased sensitivity of the viral protease, which differs from the cellular proteases. The regulatory protein vif is active in virus assembly and Gag processing. The RNA genome is then incorporated into the newly formed viral capsid that requires zinc finger domains (p7) and the matrix protein (MA: p17). The matrix protein forms a coat on the inner surface of the viral membrane, which is essential for the budding of the new virus from the host cell's surface. As new virus is formed, it buds through specialized membrane areas, known as lipid rafts, and is released. The virus release is facilitated by the viroporin vpu, which induces rapid degradation of newly synthesized CD4 molecules that impede viral budding. In addition, vpu counteracts host innate immunity (e.g., hampering natural killer T-cell activity).

Full-length sequencing of the HIV-1 genome demonstrated three different groups (M [main], O [outlier], and N [non-M, non-O]), probably occurring from multiple zoonotic infections from primates in different geographic regions. The same technique identified eight groups of HIV-2 isolates. Group M diversified to nine subtypes (or clades A to D, F to H, J, and K). In each region of the world, certain clades predominate, for example, clade A in Central Africa, clade B in the United States and South America, clade C in South Africa, clade E in Thailand, and clade F in Brazil. Although some subtypes were identified within group O, none was found in any of the HIV-2 groups. Clades are mixed in some patients as a result of HIV recombination, and some crossing between groups (i.e., M and O) has been reported.

HIV-2 has a similar life cycle to HIV-1 and is known to cause infection in several monkey species. Subtypes A and B are the major causes of infection in humans, but rarely cause infection in children. HIV-2 differs from HIV-1 in its accessory genes (e.g., it has no vpu gene but contains the vpx gene, which is not found in HIV-1). It is most prevalent in western Africa, but increasing numbers of cases are reported from Europe and southern Asia. The diagnosis of HIV-2 infection is more difficult because of major differences in the genetic sequences between HIV-1 and HIV-2. Thus, several of the standard confirmatory assays (immunoblot), which are HIV-1 specific, may give indeterminate results with HIV-2 infection. If HIV-2 infection is suspected, a combination screening test that detects antibody to HIV-1 and HIV-2 peptides should be used. In addition, the rapid HIV detection tests have been less reliable in patients suspected to be dually infected with HIV-1 and HIV-2, because of lower antibody concentrations against HIV-2. HIV-2 viral loads also have limited availability. Notably, HIV-2 infection demonstrates a longer asymptomatic stage of infection and slower declines of CD4+ T-cell counts than HIV-1, as well as is less efficiently transmitted from mother to child, likely related to lower levels of viremia with HIV-2.

Epidemiology

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 1.8 million children younger than 15 yr of age worldwide were living with HIV-1 infection; the 150,000 new infections annually in children was a 70% reduction since 2000. Approximately 80% of new infections in this age-group occur in sub-Saharan Africa. These trends reflect the slow but steady expansion of services to prevent perinatal transmission of HIV to infants. Notably, there are still 110,000 deaths worldwide of children < 15 yr of age with HIV. Unfortunately, through 2016, an estimated 16.5 million children have been orphaned by AIDS, defined as having one or both parents die from AIDS.

Globally, the vast majority of HIV infections in childhood are the result of vertical transmission from an HIV-infected mother. In the United States, approximately 11,700 children, adolescents, or young adults were reported to be living with perinatally acquired HIV infection in 2014. The number of U.S. children with AIDS diagnosed each year increased from 1984 to 1992 but then declined by more than 95% to < 100 cases annually by 2003, largely from the success of prenatal screening and perinatal antiretroviral treatment of HIV-infected mothers and infants. From 2009 to 2013, there were 497 infants born with perinatally acquired HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico. Children of racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately overrepresented, particularly non-Hispanic African-Americans and Hispanics. Race and ethnicity are not risk factors for HIV infection but more likely reflect other social factors that may be predictive of an increased risk for HIV infection, such as lack of educational and economic opportunities. As of 2014, New York, Florida, Texas, Georgia, Illinois, and California are the states with the highest numbers of perinatally acquired cases of HIV in the United States.

Adolescents (13-24 yr of age) constitute an important growing population of newly infected individuals; in 2015, 22% of all new HIV infections occurred in this age-group, with 81% of youth cases occurring in young males who have sex with males (MSM); 8% of cases of AIDS also occurred in this age-group. Targeted efforts have decreased new cases by 18% among youth MSM from 2008 to 2014. It is estimated than 50% of HIV-positive youth are unaware of their diagnosis, the highest of any age-group. Considering the long latency period between the time of infection and the development of clinical symptoms, reliance on AIDS case definition surveillance data significantly underrepresents the impact of the disease in adolescents. Based on a median incubation period of 8-12 yr, it is estimated that 15–20% of all AIDS cases were acquired between 13 and 19 yr of age.

Risk factors for HIV infection vary by gender in adolescents. For example, 91–93% of males between the ages of 13 and 24 yr with HIV acquire infection through sex with males. In contrast, 91–93% of adolescent females with HIV are infected through heterosexual contact. Adolescent racial and ethnic minority populations are overrepresented, especially among females.

Transmission

Transmission of HIV-1 occurs via sexual contact, parenteral exposure to blood, or vertical transmission from mother to child via exposure to vaginal secretions during birth or via breast milk. The primary route of infection in the pediatric population (<15 yr) is vertical transmission. Rates of transmission of HIV from mother to child have varied in high- and low-resource countries; the United States and Europe have documented transmission rates in untreated women of between 12% and 30%, whereas transmission rates in Africa and Haiti have been higher (25–52%), likely because of more advanced maternal disease and the presence of coinfections. Perinatal treatment of HIV-infected pregnant women with antiretroviral drugs has dramatically decreased the rate to < 2%.

Vertical transmission of HIV can occur before delivery (intrauterine), during delivery (intrapartum), or after delivery (postpartum through breastfeeding). Although intrauterine transmission has been suggested by identification of HIV by culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in fetal tissue as early as 10 wk, statistical modeling data suggest that the majority of in utero transmissions likely occur in late gestation, when the vascular integrity of the placenta weakens and microtransfusions across the maternal–fetal circulation occur. It is generally accepted that 20–30% of infected newborns are infected in utero, because this percentage of infants has laboratory evidence of infection (positive viral culture or PCR) within the first week of life. Some studies have found that viral detection soon after birth is also correlated with an early onset of symptoms and rapid progression to AIDS, consistent with more long-standing infection during gestation.

A higher percentage of HIV-infected children acquire the virus intrapartum, evidenced by the fact that 70–80% of infected infants do not demonstrate detectable virus until after 1 wk of age. The mechanism of transmission appears to be mucosal exposure to infected blood and cervicovaginal secretions in the birth canal, and intrauterine contractions during active labor/delivery could also increase the risk of late microtransfusions. Breastfeeding is the least-common route of vertical transmission in high resource nations, but is responsible for as much as 40% of perinatal infections in resource-limited countries. Both free and cell-associated viruses have been detected in breast milk from HIV-infected mothers. The risk for transmission through breastfeeding is approximately 9–16% in women with established infection, but is 29–53% in women who acquire HIV postnatally, suggesting that the viremia experienced by the mother during primary infection at least triples the risk for transmission. Where replacement feeding is readily available and safe, it seems reasonable for women to substitute infant formula for breast milk if they are known to be HIV infected or are at risk for ongoing sexual or parenteral exposure to HIV. However, the WHO recommends that in low-resource countries where other diseases (diarrhea, pneumonia, malnutrition) substantially contribute to a high infant mortality rate, the benefit of breastfeeding outweighs the risk for HIV transmission, and HIV-infected women in developing countries should exclusively breastfeed their infants for at least the first 6 mo of life (see Prevention later in this chapter).

Several risk factors influence the rate of vertical transmission: maternal viral load at delivery, preterm delivery (<34 wk gestation), and low maternal antenatal CD4 count. The most important variable appears to be the level of maternal viremia; the odds of transmission may be increased more than two-fold for every log10 increase in viral load at delivery. Elective cesarean delivery was shown to decrease transmission by 87% if used in conjunction with zidovudine therapy in the mother and infant. However, because these data predated the advent of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART, also called HAART), the additional benefit of cesarean section appears to be negligible if the mother's viral load is < 1,000 copies/mL. It should be noted that rarely (≤0.1%), transmission may occur with maternal viral loads < 50 copies/mL.

Transfusions of infected blood or blood products have accounted for 3–6% of all pediatric AIDS cases. The period of highest risk was between 1978 and 1985, before the availability of HIV antibody–screened blood products. Whereas the prevalence of HIV infection in individuals with hemophilia treated before 1985 was as high as 70%, heat treatment of factor VIII concentrate and HIV antibody screening of donors has virtually eliminated HIV transmission in this population. Donor screening has dramatically reduced, but not eliminated, the risk for blood transfusion–associated HIV infection: nucleic acid amplification testing of minipools (pools of 16-24 donations) performed on antibody-nonreactive blood donations (to identify donations made during the window period before seroconversion) reduced the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV-1 to approximately 1 in 2 million blood units. However, in many resource-limited countries, screening of blood is not uniform, and the risk for transmitting HIV infection via transfusion remains in these settings.

Although HIV can be isolated rarely from saliva, it is in very low titers (<1 infectious particle/mL) and has not been implicated as a transmission vehicle. Studies of hundreds of household contacts of HIV-infected individuals have found that the risk for household HIV transmission is essentially nonexistent. Only a few cases have been reported in which urine or feces (possibly devoid of visible blood) have been proposed as a possible vehicle of HIV transmission, though these cases have not been fully verified.

In the pediatric population, sexual transmission is infrequent, but a small number of cases resulting from sexual abuse have been reported. Sexual contact is a major route of transmission in the adolescent population, accounting for most of the cases.

Pathogenesis

HIV infection affects most of the immune system and disrupts its homeostasis (see Fig. 302.3 ). In most cases, the initial infection is caused by low amounts of a single virus. Therefore, disease may be prevented by prophylactic drug(s) or vaccine. When the mucosa serves as the portal of entry for HIV, the first cells to be affected are the dendritic cells. These cells collect and process antigens introduced from the periphery and transport them to the lymphoid tissue. HIV does not infect the dendritic cell but binds to its DC-SIGN surface molecule, allowing the virus to survive until it reaches the lymphatic tissue. In the lymphatic tissue (e.g., lamina propria, lymph nodes), the virus selectively binds to cells expressing CD4 molecules on their surface, primarily helper T lymphocytes (CD4+ T cells) and cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. Other cells bearing CD4, such as microglia, astrocytes, oligodendroglia, and placental tissue containing villous Hofbauer cells, may also be infected by HIV. Additional factors (coreceptors) are necessary for HIV fusion and entry into cells. These factors include the chemokines CXCR4 (fusion) and CCR5. Other chemokines (CCR1, CCR3) may be necessary for the fusion of certain HIV strains. Several host genetic determinants affect the susceptibility to HIV infection, the progression of disease, and the response to treatment. These genetic variants vary in different populations. A deletion in the CCR5 gene that is protective against HIV infection (CCR5Δ32) is relatively common in whites but is rare in individuals of African descent. Several other genes that regulate chemokine receptors, ligands, the histocompatibility complex, and cytokines also influence the outcome of HIV infection. Usually, CD4+ lymphocytes migrate to the lymphatic tissue in response to viral antigens and then become activated and proliferate, making them highly susceptible to HIV infection. This antigen-driven migration and accumulation of CD4 cells within the lymphoid tissue may contribute to the generalized lymphadenopathy characteristic of the acute retroviral syndrome in adults and adolescents. HIV preferentially infects the very cells that respond to it (HIV-specific memory CD4 cells), accounting for the progressive loss of these cells and the subsequent loss of control of HIV replication. The continued destruction of memory CD4+ cells in the gastrointestinal tract (in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue or GALT) leads to reduced integrity of the gastrointestinal epithelium followed by leakage of bacterial particles into the blood and increased inflammatory response, which cause further CD4+ cell loss. When HIV replication reaches a threshold (usually within 3-6 wk from the time of infection), a burst of plasma viremia occurs. This intense viremia causes acute HIV infection, formerly known as acute retroviral syndrome which can present similar to the flu or mononucleosis (fever, rash, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, malaise, arthralgia, fatigue, elevated liver enzymes) in 50–70% of infected adults. With establishment of a cellular and humoral immune response within 2-4 mo, the viral load in the blood declines substantially, and patients enter a phase characterized by a lack of symptoms and a return of CD4 cells to only moderately decreased levels. Typically, adult patients who are not treated eventually progress to achieve a virologic set point (steady state), usually ranging from 10,000-100,000 during this clinical latency. This is in contrast to untreated infants with vertically acquired HIV who can achieve viral loads that are much higher, resulting in faster CD4 count declines and earlier onset of significant immunodeficiency. HIV rapidly responds to the immune system pressure by developing a genetically complex population (quasispecies) that successfully evades it. In addition, inappropriate use of antiretroviral treatment increases the ability of the virus to diverge even further by selecting for mutants with fitness or resistance advantages in the presence of subtherapeutic drug levels. Early HIV-1 replication in children has no apparent clinical manifestations. Whether tested by virus isolation or by PCR for viral nucleic acid sequences, fewer than 40% of HIV-1–infected infants demonstrate evidence of the virus at birth. The viral load increases by 1-4 mo, and essentially all perinatally HIV-infected infants have detectable HIV-1 in peripheral blood by 4 mo of age, except for those who may acquire infection via ongoing breast feeding.

In adults, the long period of clinical latency (8-12 yr) is not indicative of viral latency. In fact, there is a very high turnover of virus and CD4 lymphocytes (more than a billion cells per day), gradually causing deterioration of the immune system, marked by depletion of CD4 cells. Several mechanisms for the depletion of CD4 cells in adults and children have been suggested, including HIV-mediated single cell killing, formation of multinucleated giant cells of infected and uninfected CD4 cells (syncytia formation), virus-specific immune responses (natural killer cells, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity), superantigen-mediated activation of T cells (rendering them more susceptible to infection with HIV), autoimmunity, and programmed cell death (apoptosis). The viral burden is greater in the lymphoid organs than in the peripheral blood during the asymptomatic period. As HIV virions and their immune complexes migrate through the lymph nodes, they are trapped in the network of dendritic follicular cells. Because the ability of HIV to replicate in T cells depends on the state of activation of the cells, the immune activation that takes place within the microenvironment of the lymph nodes in HIV disease serves to promote infection of new CD4 cells, as well as subsequent viral replication within these cells. Monocytes and macrophages can be productively infected by HIV yet resist the cytopathic effect of the virus and, with their long lifespan, explain their role as reservoirs of HIV and as effectors of tissue damage in organs such as the brain. In addition, they reside in anatomic viral sanctuaries where current treatment agents are less effective.

The innate immune system responds almost immediately following HIV infection by recognizing the viral nucleic acids, once the virus fuses to the infected cell, by the toll-like receptor 7. This engagement leads to activation of proinflammatory cytokines and interferon (IFN-α), which blocks virus replication and spread. The virus uses its Nef protein to downregulate the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and non-MHC ligands to reduce the natural killer (NK) cell–mediated anti-HIV activity. It also modulates NK cell differentiation and maturation, dysregulates cytokine production, and increases apoptosis. Although the mechanism by which the innate system triggers the adaptive immune responses is not yet fully understood, cell-mediated and humoral responses occur early in the infection. CD8 T cells play an important role in containing the infection. These cells produce various ligands (macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β, RANTES), which suppress HIV replication by blocking the binding of the virus to the coreceptors (CCR5). HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) develop against both the structural (ENV, POL, GAG) and regulatory (tat) viral proteins. The CTLs appear at the end of the acute infection, as viral replication is controlled by killing HIV-infected cells before new viruses are produced and by secreting potent antiviral factors that compete with the virus for its receptors (CCR5). Neutralizing antibodies appear later in the infection and seem to help in the continued suppression of viral replication during clinical latency. There are at least two possible mechanisms that control the steady-state viral load level during the chronic clinical latency. One mechanism may be the limited availability of activated CD4 cells, which prevent a further increase in the viral load. The other mechanism is the development of an active immune response, which is influenced by the amount of viral antigen and limits viral replication at a steady state. There is no general consensus about which of these two mechanisms is more important. The CD4 cell limitation mechanism accounts for the effect of antiretroviral therapy, whereas the immune response mechanism emphasizes the importance of immune modulation treatment (cytokines, vaccines) to increase the efficiency of immune-mediated control. A group of cytokines that includes tumor necrosis factor TNF-α, TNF-β, interleukin IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor plays an integral role in upregulating HIV expression from a state of quiescent infection to active viral replication. Other cytokines such as IFN-γ, IFN-β, and IL-13 exert a suppressive effect on HIV replication. Certain cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, transforming growth factor-β) reduce or enhance viral replication depending on the infected cell type. The interactions among these cytokines influence the concentration of viral particles in the tissues. Plasma concentrations of cytokines need not be elevated for them to exert their effect, because they are produced and act locally in the tissues. The activation of virtually all the cellular components of the immune system (i.e., T and B cells, NK cells, and monocytes) plays a significant role in the pathologic aspects of HIV infection. Further understanding of their interactions during the infection will expand our treatment options. Commonly, HIV isolated during the clinical latency period grows slowly in culture and produces low titers of reverse transcriptase. These isolates from earlier in clinical latency use CCR5 as their coreceptor. By the late stages of clinical latency, the isolated virus is phenotypically different. It grows rapidly and to high titers in culture and uses CXCR4 as its coreceptor. The switch from CCR5 receptor to CXCR4 receptor increases the capacity of the virus to replicate, to infect a broader range of target cells (CXCR4 is more widely expressed on resting and activated immune cells), and to kill T cells more rapidly and efficiently. As a result, the clinical latency phase is over and progression toward AIDS is noted. The progression of disease is related temporally to the gradual disruption of lymph node architecture and degeneration of the follicular dendritic cell network with loss of its ability to trap HIV particles. The virus is freed to recirculate, producing high levels of viremia and an increased disappearance of CD4 T cells during the later stages of disease.

The clinical course of HIV infection shows substantial heterogeneity. This variation is determined by both viral and host factors. HIV viruses that use coreceptor CXCR4 in the course of the infection are associated with an accelerated deterioration of the immune system and more rapid progression to AIDS. In addition, several known host genetic determinants (e.g., variants in the human leukocyte antigen region, polymorphisms in the CCR5 region such as CCR5Δ32) were already identified as affecting the disease course. There are likely additional host and viral factors yet to be identified that contribute to the variable course of HIV infection in individuals, as well. Three distinct patterns of disease are described in children. Approximately 15–25% of HIV-infected newborns in developed countries present with a rapid progression course, with onset of AIDS and symptoms during the first few months of life and a median survival time of 6-9 mo if untreated. In resource-limited countries, the majority of HIV-infected newborns will have this rapidly progressing disease course. It has been suggested that if intrauterine infection coincides with the period of rapid expansion of CD4 cells in the fetus, the virus could effectively infect the majority of the body's immunocompetent cells. The normal migration of these cells to the marrow, spleen, and thymus would result in efficient systemic delivery of HIV, unchecked by the immature immune system of the fetus. Thus, infection would be established before the normal ontogenic development of the immune system, causing more-severe impairment of immunity. Most children in this group have detectable virus in the plasma (median level: 11,000 copies/mL) in the first 48 hr of life. This early evidence of viral presence suggests that the newborn was infected in utero. The viral load rapidly increases, peaking by 2-3 mo of age (median: 750,000 copies/mL) and staying high for at least the first 2 yr of life.

Sixty percent to 80% of perinatally infected newborns in high resource countries present with a much slower progression of disease, with a median survival time of 6 yr representing the second pattern of disease. Many patients in this group have a negative PCR in the first week of life and are therefore considered to be infected intrapartum. In a typical patient, the viral load rapidly increases, peaking by 2-3 mo of age (median: 100,000 copies/mL) and then slowly declines over a period of 24 mo. The slow decline in viral load is in sharp contrast to the rapid decline after primary infection seen in adults. This observation can be explained only partially by the immaturity of the immune system in newborns and infants.

The third pattern of disease occurs in < 5% of perinatally infected children, referred to as long-term survivors or long-term nonprogressors, who have minimal or no progression of disease with relatively normal CD4 counts and very low viral loads for longer than 8 yr. Mechanisms for the delay in disease progression include effective humoral immunity and/or CTL responses, host genetic factors (e.g., human leukocyte antigen profile), and infection with an attenuated (defective-gene) virus. A subgroup of the long-term survivors called elite survivors or elite suppressors has no detectable virus in the blood and may reflect different or greater mechanisms of protection from disease progression. Note that both groups warrant long-term close follow-up because later in their course they may begin to progress with their disease.

HIV-infected children have changes in the immune system that are similar to those in HIV-infected adults. Absolute CD4 cell depletion may be less dramatic because infants normally have a relative lymphocytosis. A value of 750 CD4 cells/µL in children younger than 1 yr of age is indicative of severe CD4 depletion and is comparable to < 200 CD4 cells/µL in adults. Lymphopenia is relatively rare in perinatally infected children and is usually only seen in older children or those with end-stage disease. Although cutaneous anergy is common during HIV infection, it is also frequent in healthy children younger than 1 yr of age, and thus its interpretation is difficult in infected infants. The depletion of CD4 cells also decreases the response to soluble antigens such as the in vitro mitogens phytohemagglutinin and concanavalin A.

Polyclonal activation of B cells occurs in most children early in the infection, as evidenced by elevation of immunoglobulins IgA, IgM, IgE, and, particularly, IgG (hypergammaglobulinemia), with high levels of anti–HIV-1 antibody. This response may reflect both dysregulation of the T-cell suppression of B-cell antibody synthesis and active CD4 enhancement of the B-lymphocyte humoral response. As a result, the antibody response to routine childhood vaccinations may be abnormal. The B-cell dysregulation precedes the CD4 depletion in many children and may serve as a surrogate marker of HIV infection in symptomatic children in whom specific diagnostic tests (PCR, culture) are not available or are too expensive. Despite the increased levels of immunoglobulins, some children lack specific antibodies or protective antibodies. Hypogammaglobulinemia is very rare (<1%).

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is more common in pediatric patients than in adults. Macrophages and microglia play an important role in HIV neuropathogenesis, and data suggest that astrocytes may also be involved. Although the specific mechanisms for encephalopathy in children are not yet clear, the developing brain in young infants is affected by at least two mechanisms. The virus itself may directly infect various brain cells or cause indirect damage to the nervous system by the release of cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-2) or reactive oxygen damage from HIV-infected lymphocytes or macrophages.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of HIV infection vary widely among infants, children, and adolescents. In most infants, physical examination at birth is normal. Initial symptoms may be subtle, such as lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, or nonspecific, such as failure to thrive, chronic or recurrent diarrhea, respiratory symptoms, or oral thrush and may be distinguishable only by their persistence. Whereas systemic and pulmonary findings are common in the United States and Europe, chronic diarrhea, pneumonia, wasting, and severe malnutrition predominate in Africa. Clinical manifestations found more commonly in children than adults with HIV infection include recurrent bacterial infections, chronic parotid swelling, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP), and early onset of progressive neurologic deterioration; note that chronic parotid swelling and LIP are associated with a slower progression of disease.

The CDC Surveillance Case Definition for HIV infection is based on the age-specific CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or the CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes (Table 302.1 ), except when a stage 3–defining opportunistic illness (Table 302.2 ) supersedes the CD4 data. Age adjustment of the absolute CD4 count is necessary because counts that are relatively high in normal infants decline steadily until age 6 yr, when they reach adult norms. The CD4 count takes precedence over the CD4 T-lymphocyte percentage, and the percentage is considered only if the count is unavailable.

Table 302.1

HIV Infection Stage* Based on Age-Specific CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Count or CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Percentage of Total Lymphocytes

| STAGE | AGE ON DATE OF CD4+ T-LYMPHOCYTE TEST | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 Yr | 1-5 Yr | ≥6 Yr | ||||

| CELLS/µL | % | CELLS/µL | % | CELLS/µL | % | |

| 1 | ≥1,500 | ≥34 | ≥1,000 | ≥30 | ≥500 | ≥26 |

| 2 | 750-1,499 | 26-33 | 500-999 | 22-29 | 200-499 | 14-25 |

| 3 | <750 | <26 | <500 | <22 | <200 | <14 |

* Stage is based primarily on the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. The CD4+ T-lymphocyte count takes precedence over the CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage, and the percentage is considered only if the count is missing.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection—United States, 2014, MMWR 63(No RR-3):1-10, 2014.

Table 302.2

Stage 3–Defining Opportunistic Illnesses in HIV Infection

|

Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent* Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs Cervical cancer, invasive † Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 mo duration) Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age > 1 mo Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision) Encephalopathy attributed to HIV ‡ Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 mo duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age > 1 mo) Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 mo duration) Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term) Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term) Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis of any site, pulmonary, † disseminated, or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary Pneumocystis jiroveci (previously known as Pneumocystis carinii ) pneumonia Pneumonia, recurrent † Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Salmonella septicemia, recurrent Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age > 1 mo Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV ‡ |

* Only among children aged < 6 yr.

† Only among adults, adolescents, and children aged ≥ 6 yr.

‡ Suggested diagnostic criteria for these illnesses, which might be particularly important for HIV encephalopathy and HIV wasting syndrome, are described in the following references: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1994 Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age, MMWR 43(No. RR-12), 1994; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults, MMWR 41(No. RR-17), 1992.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection—United States, 2014, MMWR 63(No RR-3):1-10, 2014.

Infections

Approximately 20% of AIDS-defining illnesses in children are recurrent bacterial infections caused primarily by encapsulated organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Salmonella as a result of disturbances in humoral immunity. Other pathogens, including Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae, and other Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms may also be seen. The most common serious infections in HIV-infected children are bacteremia, sepsis, and bacterial pneumonia, accounting for more than 50% of infections in these patients. Meningitis, urinary tract infections, deep-seated abscesses, and bone/joint infections occur less frequently. Milder recurrent infections, such as otitis media, sinusitis, and skin and soft tissue infections, are very common and may be chronic with atypical presentations.

Opportunistic infections are generally seen in children with severe depression of the CD4 count. In adults, these infections often represent reactivation of a latent infection acquired early in life. In contrast, young children generally have primary infection and often have a more fulminant course of disease reflecting the lack of prior immunity. In addition, infants < 1 yr of age have a higher incidence of developing stage 3–defining opportunistic infections and mortality rates compared with older children and adults even at higher CD4 counts, reflecting that the CD4 count may overpredict the immune competence in young infants. This principle is best illustrated by Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii ) pneumonia, the most common opportunistic infection in the pediatric population (see Chapter 271 ). The peak incidence of Pneumocystis pneumonia occurs at age 3-6 mo in the setting of undiagnosed perinatally acquired disease, with the highest mortality rate in children younger than 1 yr of age. Aggressive approaches to treatment have improved the outcome substantially. Although the overall incidence of opportunistic infections has markedly declined since the era of combination antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infections still occur in patients with severe immunodepletion as the result of unchecked viral replication, which often accompanies poor antiretroviral therapy adherence.

The classic clinical presentation of Pneumocystis pneumonia includes an acute onset of fever, tachypnea, dyspnea, and marked hypoxemia; in some children, more indolent development of hypoxemia may precede other clinical or x-ray manifestations. In some cases, fever may be absent or low grade, particularly in more indolent cases. Chest x-ray findings most commonly consist of interstitial infiltrates or diffuse alveolar disease, which rapidly progresses. Chest x-ray in some cases can have very subtle findings and can mimic the radiologic appearance of viral bronchiolitis. Nodular lesions, streaky or lobar infiltrates, or pleural effusions may occasionally be seen. The diagnosis is established by demonstration of P. jiroveci with appropriate staining of induced sputum or bronchoalveolar fluid lavage; rarely, an open lung biopsy is necessary. Bronchoalveolar lavage and open lung biopsy have significantly improved sensitivity (75–95%) for Pneumocystis testing than induced sputum (20–40%), such that if an induced sputum is negative it does not exclude the diagnosis. PCR testing on respiratory specimens is also available and is more sensitive than microscopy but also has less specificity; it is also not widely available.

The first-line therapy for Pneumocystis pneumonia is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (15-20 mg/kg/day of the TMP component divided every 6 hr intravenously) with adjunctive corticosteroids for moderate to severe disease, usually defined as if the PaO 2 is < 70 mm Hg while breathing room air. After improvement, therapy with oral TMP-SMX should continue for a total of 21 days while the corticosteroids are weaned. An alternative therapy for Pneumocystis pneumonia includes intravenous administration of pentamidine (4 mg/kg/day). Other regimens such as TMP plus dapsone, clindamycin plus primaquine, or atovaquone are used as alternatives in adults but have not been widely used in children to date.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC) being most common, may cause disseminated disease in HIV-infected children who are severely immunosuppressed. The incidence of MAC infection in antiretroviral therapy–naïve children >6 yr with < 100 CD4 cells/µL is estimated to be as high as 10%, but effective cART that results in viral suppression makes MAC infections rare. Disseminated MAC infection is characterized by fever, malaise, weight loss, and night sweats; diarrhea, abdominal pain, and, rarely, intestinal perforation or jaundice (a result of biliary tract obstruction by lymphadenopathy) may also be present. Labs may be notable for significant anemia. The diagnosis is made by the isolation of MAC from blood, bone marrow, or tissue; the isolated presence of MAC in the stool does not confirm a diagnosis of disseminated MAC. Treatment can reduce symptoms and prolong life but is at best only capable of suppressing the infection if severe CD4 depletion persists. Therapy should include at least two drugs: clarithromycin or azithromycin and ethambutol. A third drug (rifabutin, rifampin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, or amikacin) is generally added to decrease the emergence of drug-resistant isolates. Careful consideration of possible drug interactions with antiretroviral agents is necessary before initiation of disseminated MAC therapy. Drug susceptibilities should be ascertained, and the treatment regimen should be adjusted accordingly in the event of an inadequate clinical response to therapy. Because of the great potential for toxicity with most of these medications, surveillance for adverse effects should be ongoing. Less commonly, NTM infections can also be focal in these patients, including lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, tenosynovitis, and pulmonary disease.

Oral candidiasis is the most common fungal infection seen in HIV-infected children. Oral nystatin suspension (2-5 mL qid) is often effective. Clotrimazole troches or fluconazole (3-6 mg/kg orally qd) are effective alternatives. Oral thrush progresses to involve the esophagus in as many as 20% of children with severe CD4 depletion, presenting with symptoms such as anorexia, dysphagia, vomiting, and fever. Treatment with oral fluconazole for 7-14 days generally results in rapid improvement in symptoms. Fungemia rarely occurs, usually in the setting of indwelling venous catheters, and up to 50% of cases may be caused by non–albicans species. Disseminated histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis are rare in pediatric patients but may occur in endemic areas.

Parasitic infections such as intestinal cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis and rarely isosporiasis or giardiasis are other opportunistic infections that cause significant morbidity. Although these intestinal infections are usually self-limiting in healthy hosts, they cause severe chronic diarrhea in HIV-infected children with low CD4 counts, often leading to malnutrition. Nitazoxanide therapy is partially effective at improving cryptosporidia diarrhea, but immune reconstitution with cART is the most important factor for clearance of the infection. Albendazole has been reported to be effective against most microsporidia (excluding Enterocytozoon bieneusi ), and TMP-SMX appears to be effective for isosporiasis.

Viral infections, especially with the herpesvirus group, pose significant problems for HIV-infected children. HSV causes recurrent gingivostomatitis, which may be complicated by local and distant cutaneous dissemination. Primary varicella-zoster virus infection (chickenpox) may be prolonged and complicated by bacterial superinfections or visceral dissemination, including pneumonitis. Recurrent, atypical, or chronic episodes of herpes zoster are often debilitating and require prolonged therapy with acyclovir; in rare instances, varicella-zoster virus has developed a resistance to acyclovir, requiring the use of foscarnet. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection occurs in the setting of severe CD4 depletion (<50 CD4 cells/µL for >6 yr) and may involve single or multiple organs. Retinitis, pneumonitis, esophagitis, gastritis with pyloric obstruction, hepatitis, colitis, and encephalitis have been reported, but these complications are rarely seen if cART is given. Ganciclovir and foscarnet are the drugs of choice and are often given together in children with sight-threatening cytomegalovirus retinitis. Intraocular injections of foscarnet or intraocular ganciclovir implants plus oral valganciclovir have also been efficacious in adults and older children with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Measles may occur despite immunization and may present without the typical rash. It often disseminates to the lung or brain with a high mortality rate in these patients. HIV-infected children with low CD4 counts can also develop extensive cutaneous molluscum contagiosum infection. Respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus may present with prolonged symptoms and persistent viral shedding. In parallel with the increased prevalence of genital tract human papillomavirus infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and anal intraepithelial neoplasia also occur with increased frequency among HIV-1–infected adult women compared with HIV-seronegative women. The relative risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is 5-10 times higher for HIV-1 seropositive women. Multiple modalities are used to treat human papillomavirus infection (see Chapter 293 ), although none is uniformly effective and the recurrence rate is high among HIV-1–infected persons.

Appropriate therapy with antiretroviral agents may result in immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is characterized by an increased inflammatory response from the recovered immune system to subclinical opportunistic infections (e.g., Mycobacterium infection, HSV infection, toxoplasmosis, CMV infection, Pneumocystis infection, cryptococcal infection). This condition is more commonly observed in patients with progressive disease and severe CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion. Patients with IRIS develop fever and worsening of the clinical manifestations of the opportunistic infection or new manifestations (e.g., enlargement of lymph nodes, pulmonary infiltrates), typically within the first few weeks after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Determining whether the symptoms represent IRIS, worsening of a current infection, a new opportunistic infection, or drug toxicity is often very difficult. If the syndrome does represent IRIS, adding nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents or corticosteroids may alleviate the inflammatory reaction, although the use of corticosteroids is controversial. The inflammation may take weeks or months to subside. In most cases, continuation of cART while treating the opportunistic infection (with or without antiinflammatory agents) is sufficient. If opportunistic infection is suspected prior to the initiation of antiretroviral therapy, appropriate antimicrobial treatment should be started first.

Central Nervous System

The incidence of CNS involvement in perinatally infected children is as high as 50–90% in resource-limited countries but significantly lower in high income countries, with a median onset at 19 mo of age. Manifestations may range from subtle developmental delay to progressive encephalopathy with loss or plateau of developmental milestones, cognitive deterioration, impaired brain growth resulting in acquired microcephaly, and symmetric motor dysfunction. Encephalopathy may be the initial manifestation of the disease or may present much later when severe immune suppression occurs. With progression, marked apathy, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and gait disturbance may occur, as well as loss of language and oral, fine, and/or gross motor skills. The encephalopathy may progress intermittently, with periods of deterioration followed by transiently stable plateaus. Older children may exhibit behavioral problems and learning disabilities. Associated abnormalities identified by neuroimaging techniques include cerebral atrophy in up to 85% of children with neurologic symptoms, increased ventricular size, basal ganglia calcifications, and, less frequently, leukomalacia.

Fortunately, since the advent of cART, the incident rate of encephalopathy has dramatically declined to as low as 0.08% in 2006. However, as HIV-infected children progress through adolescence and young adulthood, other subtle manifestations of CNS disease are evident, such as cognitive deficits, attention problems, and psychiatric disorders. Living with a chronic, often stigmatizing, disease; parental loss; and the requirement for lifelong pristine medication adherence compounds these issues, making it challenging for these youth as they inherit responsibility for managing their disease as adults.

Focal neurologic signs and seizures are unusual and may imply a comorbid pathologic process such as a CNS tumor, opportunistic infection, or stroke. CNS lymphoma may present with new-onset focal neurologic findings, headache, seizures, and mental status changes. Characteristic findings on neuroimaging studies include a hyperdense or isodense mass with variable contrast enhancement or a diffusely infiltrating contrast-enhancing mass. CNS toxoplasmosis is exceedingly rare in young infants but may occur in vertically HIV-infected adolescents and is typically associated with serum antitoxoplasma IgG as a marker of infection. Other opportunistic infections of the CNS are rare and include infection with CMV, JC virus (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), HSV, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Coccidioides immitis. Although the true incidence of cerebrovascular disorders (both hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic strokes) is unclear, 6–10% of children from large clinical series have been affected.

Respiratory Tract

Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections such as otitis media and sinusitis are very common. Although the typical pathogens (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis) are most common, unusual pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, yeast, and anaerobes may be present in chronic infections and result in complications such as invasive sinusitis and mastoiditis.

LIP (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia) is the most common chronic lower respiratory tract abnormality reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for HIV-infected children; historically this occurred in approximately 25% of HIV-infected children, although the incidence has declined in the cART era. LIP is a chronic process with nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium, often leading to progressive alveolar capillary block over months to years. It has a characteristic chronic diffuse reticulonodular pattern on chest radiography rarely accompanied by hilar lymphadenopathy, allowing a presumptive diagnosis to be made radiographically before the onset of symptoms. There is an insidious onset of tachypnea, cough, and mild to moderate hypoxemia with normal auscultatory findings or minimal rales. Progressive disease presents with symptomatic hypoxemia, which usually resolves with oral corticosteroid therapy, accompanied by digital clubbing. Several studies suggest that LIP is a lymphoproliferative response to a primary Epstein-Barr virus infection in the setting of HIV infection. It is also associated with a slower immunologic decline.

Most symptomatic HIV-infected children experience at least one episode of pneumonia during their disease. S. pneumoniae is the most common bacterial pathogen, but P. aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacterial pneumonias may occur in end-stage disease and are often associated with acute respiratory failure and death. Rarely, severe recurrent bacterial pneumonia results in bronchiectasis. Pneumocystis pneumonia is the most common opportunistic infection, but other pathogens, including CMV, Aspergillus, Histoplasma, and Cryptococcus can cause pulmonary disease. Infection with common respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, influenza, and adenovirus, may occur simultaneously and have a protracted course and period of viral shedding from the respiratory tract. Pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB) has been reported with increasing frequency in HIV-infected children in low-resource countries, although it is considerably more common in HIV-infected adults. Because of drug interactions between rifampin and ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy and poor tolerability of the combination of multiple drugs required, treatment of TB/HIV coinfection is particularly challenging in children.

Cardiovascular System

Cardiac dysfunction, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular dilation, reduced left ventricular fractional shortening, and/or heart failure occurred in 18–39% of HIV-infected children in the pre-cART era; among those affected, a lower nadir CD4 percentage and a higher viral load were associated with lower cardiac function. However, a more current evaluation of HIV-infected children taking long-term cART found that echocardiographic findings were closer to normal and none had symptomatic heart disease, suggesting that cART has a cardioprotective effect. What is still unclear is whether an increased rate of premature cardiovascular disease that has been seen in adults will be seen in children who have disease- or treatment-related hyperlipidemia, and prospective studies will be needed to assess this risk. Because of this risk, regular monitoring of cholesterol and lipids, as well as education regarding a heart-healthy lifestyle, is an important part of pediatric HIV care.

Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Tract

Oral manifestations of HIV disease include erythematous or pseudomembranous candidiasis, periodontal disease (e.g., ulcerative gingivitis or periodontitis), salivary gland disease (i.e., swelling, xerostomia), and, rarely, ulcerations or oral hairy leukoplakia. Gastrointestinal tract involvement is common in HIV-infected children. A variety of pathogens can cause gastrointestinal disease, including bacteria (Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, MAC), protozoa (Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Isospora, microsporidia), viruses (CMV, HSV, rotavirus), and fungi (Candida). MAC and the protozoal infections are most severe and protracted in patients with severe CD4 cell depletion. Infections may be localized or disseminated and affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the oropharynx to the rectum. Oral or esophageal ulcerations, either viral in origin or idiopathic, are painful and often interfere with eating. AIDS enteropathy, a syndrome of malabsorption with partial villous atrophy not associated with a specific pathogen, has been postulated to be a result of direct HIV infection of the gut. Disaccharide intolerance is common in HIV-infected children with chronic diarrhea.

The most common symptoms of gastrointestinal disease are chronic or recurrent diarrhea with malabsorption, abdominal pain, dysphagia, and failure to thrive. Prompt recognition of weight loss or poor growth velocity in the absence of diarrhea is critical. Linear growth impairment is often correlated with the level of HIV viremia. Supplemental enteral feedings should be instituted, either by mouth or with nighttime nasogastric tube feedings in cases associated with more severe chronic growth problems; placement of a gastrostomy tube for nutritional supplementation may be necessary in severe cases. The wasting syndrome, defined as a loss of > 10% of body weight, is not as common as failure to thrive in pediatric patients, but the resulting malnutrition is associated with a grave prognosis. Chronic liver inflammation evidenced by fluctuating serum levels of transaminases with or without cholestasis is relatively common, often without identification of an etiologic agent. Cryptosporidial cholecystitis is associated with abdominal pain, jaundice, and elevated γ-glutamyltransferase. In some patients, chronic hepatitis caused by CMV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or MAC may lead to portal hypertension and liver failure. Several of the antiretroviral drugs or other drugs such as didanosine, protease inhibitors, nevirapine, and dapsone may also cause reversible elevation of transaminases.

Pancreatitis with increased pancreatic enzymes with or without abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever may be the result of drug therapy (e.g., with pentamidine, didanosine, or stavudine) or, rarely, opportunistic infections such as MAC or CMV.

Renal Disease

Nephropathy is an unusual presenting symptom of HIV infection, more commonly occurring in older symptomatic children. A direct effect of HIV on renal epithelial cells has been suggested as the cause, but immune complexes, hyperviscosity of the blood (secondary to hyperglobulinemia), and nephrotoxic drugs are other possible factors. A wide range of histologic abnormalities has been reported, including focal glomerulosclerosis, mesangial hyperplasia, segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis, and minimal change disease. Focal glomerulosclerosis generally progresses to renal failure within 6-12 mo, but other histologic abnormalities in children may remain stable without significant renal insufficiency for prolonged periods. Nephrotic syndrome is the most common manifestation of pediatric renal disease, with edema, hypoalbuminemia, proteinuria, and azotemia with normal blood pressure. Cases resistant to steroid therapy may benefit from cyclosporine therapy. Polyuria, oliguria, and hematuria have also been observed in some patients.

Skin Manifestations

Many cutaneous manifestations seen in HIV-infected children are inflammatory or infectious disorders that are not unique to HIV infection. These disorders tend to be more disseminated and respond less consistently to conventional therapy than in the uninfected child. Seborrheic dermatitis or eczema that is severe and unresponsive to treatment may be an early nonspecific sign of HIV infection. Recurrent or chronic episodes of HSV, herpes zoster, molluscum contagiosum, flat warts, anogenital warts, and candidal infections are common and may be difficult to control.

Allergic drug eruptions are also common, in particular related to nonnucleoside reverse transcription inhibitors; they generally respond to withdrawal of the drug but also may resolve spontaneously without drug interruption; rarely, progression to Stevens-Johnson syndrome has been reported. Epidermal hyperkeratosis with dry, scaling skin is frequently observed, and sparse hair or hair loss may be seen in the later stages of the disease.

Hematologic and Malignant Diseases

Anemia occurs in 20–70% of HIV-infected children, more commonly in children with AIDS. The anemia may be a result of chronic infection, poor nutrition, autoimmune factors, virus-associated conditions (hemophagocytic syndrome, parvovirus B19 red cell aplasia), or the adverse effect of drugs (zidovudine).

Leukopenia occurs in almost 30% of untreated HIV-infected children, and neutropenia often occurs. Multiple drugs used for treatment or prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis pneumonia (TMP-SMX), MAC, and CMV (ganciclovir), or antiretroviral drugs (zidovudine) may also cause leukopenia and/or neutropenia. In cases in which therapy cannot be changed, treatment with subcutaneous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor may be necessary.

Thrombocytopenia has been reported in 10–20% of patients. The etiology may be immunologic (i.e., circulating immune complexes or antiplatelet antibodies) or, less commonly, from drug toxicity, or idiopathic. Antiretroviral therapy (cART) may also reverse thrombocytopenia in ART-naïve patients. In the event of sustained severe thrombocytopenia (<10,000 platelets/µL), treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin or anti-D immune globulin offers temporary improvement in most patients already taking cART. If ineffective, a course of steroids may be an alternative, but consultation with a hematologist should be sought. Deficiency of clotting factors (factors II, VII, IX) is not rare in children with advanced HIV disease and is often easy to correct with vitamin K. A novel disease of the thymus has been observed in a few HIV-infected children. These patients were found to have characteristic anterior mediastinal multilocular thymic cysts without clinical symptoms. Histologic examination shows focal cystic changes, follicular hyperplasia, and diffuse plasmacytosis and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment with cART may result in resolution, or spontaneous involution occurs in some cases.

Malignant diseases have been reported infrequently in HIV-infected children, representing only 2% of AIDS-defining illnesses. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including Burkitt lymphoma), primary CNS lymphoma, and leiomyosarcoma are the most commonly reported neoplasms among HIV-infected children. Epstein-Barr virus is associated with most lymphomas and with all leiomyosarcomas (see Chapter 281 ). Kaposi sarcoma, which is caused by human herpesvirus 8, occurs frequently among HIV-infected adults but is exceedingly uncommon among HIV-infected children in resource-rich countries (see Chapter 284 ).

Diagnosis

All infants born to HIV-infected mothers test antibody-positive at birth because of passive transfer of maternal HIV antibody across the placenta during gestation; therefore, antibody should not be used to establish the diagnosis of HIV in an infant. Most uninfected infants without ongoing exposure (i.e., who are not breastfed) lose maternal antibody between 6 and 18 mo of age and are known as seroreverters. Because a small proportion of uninfected infants continue to test HIV antibody-positive for up to 24 mo of age, positive IgG antibody tests, including the rapid tests, cannot be used to make a definitive diagnosis of HIV infection in infants younger than 24 mo. The presence of IgA or IgM anti-HIV in the infant's circulation can indicate HIV infection, because these immunoglobulin classes do not cross the placenta; however, IgA and IgM anti-HIV assays have been both insensitive and nonspecific and therefore are not valuable for clinical use. In any child older than 24 mo of age, demonstration of IgG antibody to HIV by a repeatedly reactive enzyme immunoassay and confirmatory HIV PCR establishes the diagnosis of HIV infection. Breastfed infants should have antibody testing performed 12 wk following cessation of breastfeeding to identify those who became infected at the end of lactation by the HIV-infected mother. Certain diseases (e.g., syphilis, autoimmune diseases) may cause false-positive or indeterminate results. In such cases, specific viral diagnostic tests (see later) have to be done.

Several rapid HIV tests are currently available with sensitivity and specificity better than those of the standard enzyme immunoassay. Many of these tests require only a single step that allows test results to be reported within less than 30 min. Performing rapid HIV testing during delivery or immediately after birth is crucial for the care of HIV-exposed newborns whose mother's HIV status was unknown during pregnancy. A positive rapid test in the mother has to be confirmed by a second different rapid test (testing different HIV-associated antibodies) or by HIV RNA PCR (viral load). Given the earlier detection of fourth-generation HIV ELISA testing (p24 antigen + HIV-1, HIV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies), Western blots are not appropriate to confirm testing, because the fourth generation assays can be positive before the Western blot becomes positive (i.e., in acute infection). In infants who are at risk of exposure to HIV-2 infection (e.g., born to an HIV-infected woman from West Africa or who has an HIV+ partner from West Africa), a rapid test that can detect both HIV-1 and HIV-2 should be used. However, if the HIV testing is negative or the Western blot test reveals an unusual pattern, further diagnostic tests should be considered. In addition, they should be tested with an HIV-2–specific DNA PCR assay; this assay has very limited availability.

Viral diagnostic assays, such as HIV DNA or RNA PCR, are considerably more useful in young infants, allowing a definitive diagnosis in most infected infants by 1-4 mo of age (Table 302.3 ). By 4 mo of age, HIV PCR testing identifies all infected nonbreastfed infants. Historically, HIV DNA PCR testing was the preferred virologic assay over HIV RNA PCR testing in developed countries for young infants due to what was thought to be a modest advantage in detecting intrapartum acquired infection for DNA PCR in the first month of life. The perinatal use of ART prophylaxis (either single drug or combination) to prevent vertical transmission has not affected the predictive value of viral diagnostic testing. The FDA-approved HIV DNA PCR test is no longer commercially available in the United States, but other assays exist; however, the sensitivity and specificity of noncommercial HIV-1 DNA tests (using individual laboratory reagents) may differ from the sensitivity and specificity of the FDA-approved commercial test. HIV RNA PCR also has increased sensitivity for non-subtype B HIV (rare in the United States). Almost 40% of infected newborns have positive test results in the first 2 days of life, with > 90% testing positive by 2 wk of age. Plasma HIV RNA PCR assays, which detect viral replication, are as sensitive as the DNA PCR for early diagnosis. Either the DNA or RNA PCR is considered acceptable for infant testing. The commercially available HIV-1 assays are not designed for quantification of HIV-2 RNA and thus should not be used to monitor patients with this infection.

Table 302.3

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee of Pediatric AIDS: Diagnosis of HIV-1 infection in children younger than 18 months in the United States, Pediatrics 120:e1547-e1562, 2007.

Viral diagnostic testing should be performed within the first 12-24 hr of life, particularly for high-risk infants (i.e., those of mothers without sustained virologic suppression, a late cART start, or a diagnosis with acute HIV during the pregnancy); the tests can identify almost 40% of HIV-infected children. It seems that many of these children have a more rapid progression of their disease and deserve more aggressive therapy. Data suggest that if cART treatment starts at this point, the outcome will be much better. In exposed children with negative virologic testing at 1-2 days of life, additional testing should be done at 2-3 wk of age, 4-8 wk of age, and 4-6 mo of age. For higher-risk infants, additional virologic diagnostic testing should be considered at 2 to 4 wk after cessation of ARV prophylaxis (i.e., at 8-10 wk of life) (Fig. 302.4 ). A positive virologic assay (i.e., detection of HIV by PCR) suggests HIV infection and should be confirmed by a repeat test on a second specimen as soon as possible because false-positive tests can occur. A confirmed diagnosis of HIV infection can be made with two positive virologic test results obtained from different blood samples. HIV infection can be presumptively excluded in nonbreastfed infants with two or more negative virologic tests (one at age ≥ 14 days and one at age ≥ 4 wk) or one negative virologic test (i.e., negative NAT [RNA or DNA]) at age ≥ 8 wk or one negative HIV antibody test at age ≥ 6 mo. Definitive exclusion of HIV infection in nonbreastfed infants is based on two or more negative virologic tests, with one obtained at age ≥ 1 mo and one at age ≥ 4 mo, or two negative HIV antibody tests from separate specimens obtained at age ≥ 6 mo. Some experts recommend documentation of seroreversion by testing for antibody at 12-18 mo of age; in low-risk infants with subtype B virus, this is likely not necessary, but antibody testing should be strongly considered in high-risk infants or infants infected with non–subtype B viruses.

Treatment

The currently available therapies do not eradicate the virus and cure the patient; instead they suppress the virus for extended periods of time and changes the course of the disease to a chronic process. Decisions about ART for pediatric HIV-infected patients are based on the magnitude of viral replication (viral load), CD4 lymphocyte count or percentage, and clinical condition. Because cART therapy changes as new drugs become available, decisions regarding therapy should be made in consultation with an expert in pediatric HIV infection. Plasma viral load monitoring and measurement of CD4 values have made it possible to implement rational treatment strategies for viral suppression, as well as to assess the efficacy of a particular drug combination. The following principles form the basis for cART:

- 1. Uninterrupted HIV replication causes destruction of the immune system and progression to AIDS.

- 2. The magnitude of the viral load predicts the rate of disease progression, and the CD4 cell count reflects the risk of opportunistic infections and HIV infection complications.

- 3. cART, which includes at least three drugs with at least two different mechanisms of action, should be the initial treatment. Potent combination therapy that suppresses HIV replication to an undetectable level restricts the selection of ART-resistant mutants; drug-resistant strains are the major factor limiting successful viral suppression and delay of disease progression.

- 4. The goal of sustainable suppression of HIV replication is best achieved by the simultaneous initiation of combinations of ART to which the patient has not been exposed previously and that are not cross resistant to drugs with which the patient has been treated previously.

- 5. Drug-related interactions and toxicities should be minimal.

- 6. Adherence to the complex drug regimens is crucial for a successful outcome.

Increasing data have shown a benefit in adult studies to starting treatment earlier, which has led to recommendations to treat earlier in children, as well. There are strong data to support the treatment of all infants < 12 mo of age, regardless of the clinical symptoms, viral load, or CD4 count from the Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral (CHER) study. Urgent treatment is recommended for older children with stage 3 opportunistic infections or immunologic suppression. Treatment is recommended for all other children, as well. Rarely, treatment may need to be deferred on a case-by-case basis based on clinical or psychosocial factors that may affect adherence with the caregivers and child.

Combination Therapy

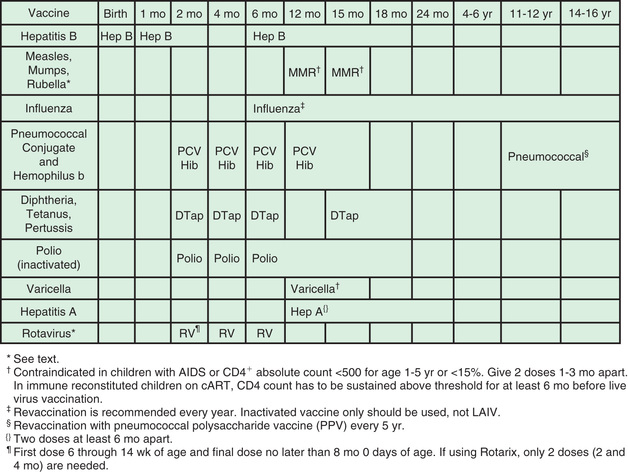

As of January 2019, 20 individual ART drugs, with 21 coformulated combination tablets as well as two pharmacokinetic boosters, were approved by the FDA for use in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Of these, 19 were approved for at least some portion of the pediatric population (0-12 yr of age), with many but not all of them available as a liquid, powder, or small tablet/capsule (Table 302.4 ). ART drugs are categorized by their mechanism of action, such as preventing viral entrance into CD4+ T cells, inhibiting the HIV reverse transcriptase or protease enzymes, or inhibiting integration of the virus into the human DNA. Within the reverse transcriptase inhibitors, a further subdivision can be made: nucleoside (or nucleotide) reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (see Fig. 302.3 ). The NRTIs have a structure similar to that of the building blocks of DNA (e.g., thymidine, cytosine). When incorporated into DNA, they act like chain terminators and block further incorporation of nucleosides, preventing viral DNA synthesis. Among the NRTIs, thymidine analogs (e.g., stavudine, zidovudine) are found in higher concentrations in activated or dividing cells, producing > 99% of the HIV virion population, and nonthymidine analogs (e.g., didanosine, lamivudine) have more activity in resting cells, which account for < 1% of the HIV virions but may serve as a reservoir for HIV. Suppression of replication in both populations is thought to be an important component of long-term viral control. NNRTIs (i.e., nevirapine, efavirenz, etravirine, rilpivirine) act differently than the NRTIs. They attach to the reverse transcriptase and cause a conformational change, reducing the activity of the enzyme. The protease inhibitors (PIs) are potent agents that act farther along the viral replicative cycle. They bind to the site where the viral long polypeptides are cut into individual, mature, and functional core proteins that produce the infectious virions before they leave the cell. The virus entry into the cell is a complex process that involves several cellular receptors and fusion. Several drugs have been developed to prevent this process. The fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide (T-20), which binds to viral gp41, causes conformational changes that prevent fusion of the virus with the CD4+ cell and entry into the cell. Maraviroc is an example of a selective CCR5 coreceptor antagonist that blocks the attachment of the virus to this chemokine (an essential process in the viral binding and fusion to the CD4+ cells). Integrase inhibitors (INSTIs) (i.e., raltegravir, dolutegravir, elvitegravir, bictegravir) block the enzyme that catalyzes the incorporation of the viral genome into the host's DNA.

Table 302.4

Summary of Antiretroviral Therapies Available in 2019

| DRUG (TRADE NAMES, FORMULATIONS) | DOSING | SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| NUCLEOSIDE/NUCLEOTIDE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE INHIBITORS | Class adverse effects: Lactic acidosis with hepatic steatosis, particularly for older members of the class | ||

|