Isoleucine, Leucine, Valine, and Related Organic Acidemias

Oleg A. Shchelochkov, Irini Manoli, Charles P. Venditti

Keywords

- isoleucine

- leucine

- valine

- branched-chain amino acid dehydrogenase

- BCKDH

- maple syrup urine disease

- MSUD

- leucinosis

- BCKDHA

- BCKDHB

- DBT

- branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase deficiency

- BCKDK

- branched-chain amino acid transporter deficiency

- LAT1

- SLC7A5

- SLC3A2

- isovaleric acidemia

- isovalerylglycine

- IVA

- isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase

- isovalerylcarnitine

- C5

- IVD

- multiple carboxylase deficiencies

- holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency

- HLCS

- biotinidase deficiency

- biotinidase

- BTD

- 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency

- 3-MCC

- MCCC1

- MCCC2

- hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine

- C5-OH

- 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid

- 3-methylglutaconic acidurias

- 3-MGA

- 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency

- AUH

- Barth syndrome

- TAZ

- Costeff syndrome

- OPA3

- MEGDEL syndrome

- SERAC1

- TMEM70 -related disorder

- TMEM70

- DCMA syndrome

- DNAJC19

- β-ketothiolase deficiency

- 3-oxothiolase deficiency

- mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase deficiency

- T2 deficiency

- ACAT1

- cytosolic acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase deficiency

- mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase deficiency

- 3HMG-CoA synthase

- HMGCS2

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric aciduria

- 3-HMG-CoA lyase

- HMGCL

- succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase deficiency

- SCOT deficiency

- OXCT1

- mevalonate kinase deficiency

- MVK

- mevalonic aciduria

- hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome

- propionic acidemia

- propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency

- PCCA

- PCCB

- propionylcarnitine

- C3-carnitine

- methylmalonic acidemia

- methylmalonyl-CoA mutase

- C4DC-carnitine

- C4-DC

- methylmalonic acid

- MUT

- hydroxocobalamin

- methylcobalamin

- adenosylcobalamin

- haptocorrin

- transcobalamin II

- transcobalamin receptor

- TCBLR

- CD320

- LMBRD1

- cbl F

- ABCD4

- cbl J

- MMACHC

- cbl C

- MMADHC

- cbl D

- MMAB

- cbl B

- MMAA

- cbl A

- methionine synthase reductase

- MTRR

- cbl E

- for methionine synthase

- MTR

- cbl G

- HCFC1

- cbl X

- combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria

- CMAMMA

- ACSF3 -related disorder

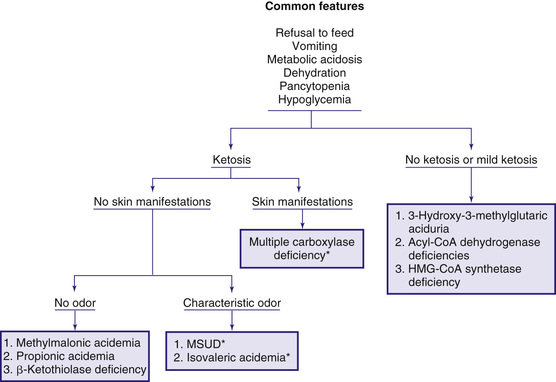

The early steps in the degradation of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—isoleucine, leucine, and valine—are similar (see Fig. 103.4 ). Under catabolic conditions, BCAAs in the muscle tissue undergo a reversible reaction of transamination catalyzed by BCAA transaminase. α-Ketoacids formed by this reaction then undergo an oxidative decarboxylation step mediated by branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH ) complex. The deficiency of BCKDH results in maple syrup urine disease, whereas the deficiency of enzymes mediating more distal steps results in accumulation of enzyme-specific organic acids excreted in the urine, thus giving those inborn errors of metabolism the eponyms organic acidemias and organic acidurias . These disorders typically cause metabolic acidosis, which usually occurs in the 1st few days of life. Although most of the clinical findings are nonspecific, some manifestations may provide important clues to the nature of the enzyme deficiency. Fig. 103.6 presents an approach to infants suspected of having an organic acidemia. The diagnosis is usually established by identifying and measuring specific organic acids in body fluids (blood, urine), identifying pathogenic variants in a respective gene, and enzyme assay.

Organic acidemias are not limited to defects in the catabolic pathways of BCAAs. Disorders causing accumulation of other organic acids include those derived from lysine (see Chapter 103.14 ), disorders of γ-glutamyl cycle (see Chapter 103.11 ), those associated with lactic acid (see Chapter 105 ), and dicarboxylic acidemias associated with defective fatty acid degradation (see Chapter 104.1 ).

Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Decarboxylation of leucine, isoleucine, and valine is accomplished by a complex enzyme system (BCKDH) using thiamine (vitamin B1 ) pyrophosphate as a coenzyme. This mitochondrial enzyme consists of 4 subunits: E1α , E1β , E2 , and E3 . The E3 subunit is shared with 2 other dehydrogenases, pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. Deficiency of any of these subunits causes maple syrup urine disease (MSUD ) (see Fig. 103.4 ), a disorder named after the sweet odor of maple syrup found in body fluids, especially urine. Clinical conditions caused by defects in E1α , E1β , E2 and E3 are designated as MSUD type IA, type IB, type 2, and type 3, respectively. This classification, however, is not very helpful clinically because the severity of clinical manifestations does not correlate with, or correspond specifically to, any single enzyme subunit. An affected infant with type 1A defect can have clinical manifestations ranging from relatively mild to very severe. A more useful classification, based on clinical findings and response to thiamine administration, delineates 5 phenotypes of MSUD.

Classic Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Classic MSUD has the most severe clinical manifestations. The BCKDH complex activity in this group varies between 0% and 2% of controls. Patients with uncontrolled or poorly controlled disease develop signs of acute encephalopathy. The mechanisms underlying this life-threatening complication are complex, but leucine and its derivative, α-ketoisocaproic acid, appear to be the key factors underlying acute encephalopathy. Elevated leucine competitively inhibits the uptake of other amino acids by the large neutral amino acid (LNAA) transporter. Once taken up by the brain tissue, leucine is metabolized by BCAA aminotransferase to α-ketoisocaproic acid, which leads to the disrupted metabolism of neurotransmitters and amino acids (glutamate, GABA, glutamine, alanine, and aspartate). α-Ketoisocaproic acid can reversibly inhibit oxidative phosphorylation and result in cerebral lactic acidosis. Collectively, these processes are detrimental to the normal function of neurons and glia, clinically manifesting as encephalopathy and brain edema and referred to as leucinosis . Affected infants who appear healthy at birth develop poor feeding and vomiting in the 1st days of life. Lethargy and coma may ensue within a few days. Physical examination reveals hypertonicity and muscular rigidity with severe opisthotonos. Periods of hypertonicity may alternate with bouts of flaccidity manifested as repetitive movements of the extremities (“boxing” and “bicycling”). Neurologic findings are often mistakenly thought to be caused by generalized sepsis and meningitis. Cerebral edema may be present; convulsions occur in most infants, and hypoglycemia is common. In contrast to most hypoglycemic states, correction of the blood glucose concentration does not improve the clinical condition. Aside from the blood glucose, routine laboratory findings are usually unremarkable, except for varying degrees of ketoacidosis. If left untreated, death can occur in the 1st few weeks or months of life.

Diagnosis is often suspected because of the peculiar odor of maple syrup in urine, sweat, and cerumen. It is usually confirmed by amino acid analysis showing marked elevations in plasma levels of leucine, isoleucine, valine, and alloisoleucine (a stereoisomer of isoleucine not normally found in blood) and depressed level of alanine. Leucine levels are usually higher than those of the other 3 amino acids. Urine contains high levels of leucine, isoleucine, and valine and their respective ketoacids. These ketoacids may be detected qualitatively by adding a few drops of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine reagent (0.1% in 0.1N HCl) to the urine; a yellow precipitate of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone is formed in a positive test. Neuroimaging during the acute state may show cerebral edema, which is most prominent in the cerebellum, dorsal brainstem, cerebral peduncle, and internal capsule. After recovery from the acute state and with advancing age, hypomyelination and cerebral atrophy may be seen in neuroimaging of the brain.

Treatment of the acute state is aimed at hydration and rapid removal of the BCAAs and their metabolites from the tissues and body fluids. Uptake of leucine by the brain and accumulation of the downstream metabolite, α-ketoisocaproic acid, appear to be the key metabolic events underlying MSUD encephalopathy. Therefore, strategies of MSUD management focus on decreasing plasma leucine to control acute and chronic manifestations of the disease.

Because renal clearance of leucine is poor, hydration alone may not produce a rapid improvement. Hemodialysis is the most effective mode of therapy in critically ill infants and should be instituted promptly; significant decreases in plasma levels of leucine, isoleucine, and valine are usually seen within 24 hr. Sufficient calories and nutrients should be provided intravenously or orally as soon as possible to reverse patient's catabolic state. Cerebral edema, if present, may require treatment with mannitol, diuretics (e.g., furosemide), or hypertonic saline. Counterintuitively, supplementation with isoleucine and valine is also needed to control plasma leucine level in MSUD patients. Judiciously administered isoleucine and valine will compete with leucine for the LNAA transporter at the blood-brain barrier and thus decrease leucine entry into the central nervous system (CNS) and help in the prevention and treatment of leucine encephalopathy.

Treatment after recovery from the acute state requires a diet low in BCAAs. Synthetic formulas devoid of leucine, isoleucine, and valine are available commercially. Because these amino acids cannot be synthesized endogenously, age-appropriate amounts of BCAAs should be provided in the diet in the form of complete protein. To avoid essential amino acid deficiencies, the amount should be titrated carefully by performing frequent analyses of the plasma amino acids, with close attention to plasma isoleucine, leucine, and valine levels. A clinical condition resembling acrodermatitis enteropathica (see Chapter 691 ) occurs in affected infants whose plasma isoleucine or valine become very low ; addition of isoleucine or valine, respectively, to the diet will hasten the recovery of skin rash. Patients with MSUD need to remain on the diet for the rest of their lives. Liver transplantation has been performed in patients with classic MSUD, with promising results.

The long-term prognosis of affected children remains guarded. Severe ketoacidosis, cerebral edema, and death may occur during any stressful situation such as infection or surgery, especially in mid-childhood. Cognitive and other neurologic deficits are common sequelae.

Intermediate (Mild) Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Children with intermediate MSUD develop milder disease after the neonatal period. Clinical manifestations are insidious and limited to the CNS. Patients have mild to moderate intellectual disability with or without seizures. They have the odor of maple syrup and excrete moderate amounts of the BCAAs and their ketoacid derivatives in the urine. Plasma concentrations of leucine, isoleucine, and valine are moderately increased whereas those of lactate and pyruvate tend to be normal. These children are commonly diagnosed during an intercurrent illness, when signs and symptoms of classic MSUD may occur. The dehydrogenase activity is 3–40% of controls. Because patients with thiamine-responsive MSUD usually have manifestations similar to the mild form, a trial of thiamine therapy is recommended. Diet therapy, similar to that of classic MSUD, is needed.

Intermittent Maple Syrup Urine Disease

In intermittent MSUD, seemingly normal children develop vomiting, odor of maple syrup, ataxia, lethargy, and coma during any stress or catabolic state such as infection or surgery. During these attacks, laboratory findings are indistinguishable from those of the classic form, and death may occur. Treatment of the acute attack of intermittent MSUD is similar to that of the classic form. After recovery, although a normal diet can be tolerated, a low-BCAA diet is recommended. The BCKDH activity in patients with the intermittent form is higher than in the classic form and may reach 40% of the control activity.

Thiamine-Responsive Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Some children with mild or intermediate forms of MSUD who are treated with high doses of thiamine have dramatic clinical and biochemical improvement. Although some respond to treatment with thiamine at 10 mg/24 hr, others may require as much as 100 mg/24 hr for at least 3 wk before a favorable response is observed. These patients also require BCAA-restricted diets. The enzymatic activity in these patients can be up to 40% of normal.

Maple Syrup Urine Disease Caused by Deficiency of E3 Subunit (MSUD Type 3)

Although sometimes referred to as “maple syrup urine disease type 3,” this very rare disorder leads to clinical and biochemical abnormalities that encompass a wide range of mitochondrial reactions. E3 subunit, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, is a component of the BCKDH complex, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Pathogenic variants in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase cause lactic acidosis, elevated pyruvate, as well as signs and symptoms similar to intermediate MSUD. Progressive neurologic impairment manifested by hypotonia and developmental delay occurs after 2 mo of age. Abnormal movements progress to ataxia or Leigh syndrome. Death may occur in early childhood.

Laboratory findings include persistent lactic acidosis with high levels of plasma pyruvate and alanine. Plasma BCAA concentrations are moderately increased. Patients excrete large amounts of lactate, pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, and the 3 branched-chain ketoacids in their urine.

No effective treatment is available. BCAA-restricted diets and treatment with high doses of thiamine, biotin, and lipoic acid have been ineffective.

Genetics and Prevalence of Maple Syrup Urine Disease

All forms of MSUD are inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene for each subunit resides on different chromosomes. The gene for E1α (BCKDHA) is on chromosome 19q13.2; that for E1β (BCKDHB) is on chromosome 6q14.1; the gene for E2 (DBT ) is on chromosome 1p21.2; and that for E3 (DLD) is on chromosome 7q31.1. Genotype-phenotype correlations are difficult to establish and are usually imprecise. The exception is thiamine-responsive MSUD, shown to be caused by pathogenic variants in DBT . Most patients are compound heterozygotes inheriting 2 different pathogenic alleles. Pathogenic variants in BCKDHA (45%) and BCKDHB (35%) account for approximately 80% of cases. Pathogenic variants in DBT are responsible for 20% of MSUD cases.

The prevalence is estimated at 1 in 185,000 live births. Classic MSUD is more prevalent in the Old Order Mennonites in the United States, at an estimated 1 in 380 live births. Affected patients in this population are homozygous for a specific pathogenic variant (c.1312T>A) in BCKDHA -encoding E1α subunit.

Early detection of MSUD is feasible by universal newborn screening. In most cases, however, especially those with classic MSUD, the infant may be quite sick by the time screening results become available (see Chapter 102 ). Prenatal diagnosis has been accomplished by enzyme assay of the cultured amniocytes, cultured chorionic villus tissue, or direct assay of samples of the chorionic villi and by identification of the known pathogenic variants in the affected gene.

Several successful pregnancies have occurred in women with different forms of MSUD. The teratogenic potential of leucine during pregnancy is unknown. Tight control of isoleucine, leucine, and valine before and during the pregnancy is important to minimize the risk of metabolic decompensation and to optimize fetal nutrition. Mothers affected by MSUD require close monitoring and meticulous management of nutrition, electrolytes, and fluids in the postpartum period.

Branched-Chain α-Ketoacid Dehydrogenase Kinase Deficiency

A defect in the regulation of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) by BCKDH kinase (BCKDK), the enzyme responsible for the phosphorylation-mediated inactivation of the BCKDH complex, causes the reverse biochemical phenotype of MSUD. Pathogenic variants in BCKDK decrease the negative regulation by the kinase, resulting in uncontrolled degradation and depletion of isoleucine, leucine, and valine in plasma and brain. Patients with BCKDK deficiency present with low plasma concentrations of isoleucine, leucine, and valine associated with autism, intellectual impairment, fine motor coordination problems, and seizures.

Branched-Chain Amino Acid Transporter Deficiency

Isoleucine, leucine, and valine are transported across the BBB mainly by the heterodimeric LNAA transporter LAT1 encoded by SLC7A5 . A defect in LAT1 caused by pathogenic variants in SLC7A5 results in low brain concentrations of isoleucine, leucine, and valine. Patients with this defect may present clinically similar to BCKDK-deficient patients, with autism, microcephaly, gross motor delays, and in some cases, seizures.

Isovaleric Acidemia

Isovaleric acidemia (IVA ) is caused by deficiency of isovaleryl–coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenase (see Fig. 103.4 ). Decreased or lost activity of isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase results in impaired leucine degradation. Accumulating derivatives of isovaleric acid, isovalerylcarnitine, isovalerylglycine, and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid can be detected in body fluids and thus enable the biochemical diagnosis and screening. Clinically, the course of IVA is highly variable, ranging from essentially asymptomatic to severe. Introduction of newborn screening and proactive management of IVA changed its outlook and the clinical course. Older siblings of symptomatic newborn infants have been reported with identical genotype and biochemical abnormalities but without clinical manifestations, suggesting that presymptomatic detection of affected patients on the newborn screen can improve clinical outcomes.

Patients with severe IVA can present with vomiting, severe acidosis, hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, and bone marrow suppression in the infantile period. Lethargy, convulsions, and coma may ensue, and death may occur if proper therapy is not initiated. Vomiting may be severe enough to suggest pyloric stenosis. The characteristic odor of sweaty feet or rancid-cheese may be present. Infants who survive this acute episode are at risk to develop episodes of metabolic decompensation later in life. In the mild form without treatment, typical clinical manifestations of severe IVA (vomiting, lethargy, acidosis or coma) may not appear until the child is a few months or a few years old. Acute episodes of metabolic decompensation may occur during a catabolic state, such as infection, dehydration, surgery, or high-protein intake. Acute episodes may be mistaken for diabetic ketoacidosis. Some patients may experience acute and recurrent episodes of pancreatitis.

Laboratory findings during the acute attacks include ketoacidosis, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and occasionally pancytopenia. Hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, and moderate to severe hyperammonemia may be present in some patients. Increases in plasma ammonia may suggest a defect in the urea cycle (see Chapter 103.12 ). In urea cycle defects, however, the infant usually shows no significant ketoacidosis (see Fig. 103.6 ).

Diagnosis is established by demonstrating marked elevations of isovaleric acid metabolites (isovalerylglycine, 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid) in body fluids, especially urine. The main compound in plasma is isovalerylcarnitine (C5-carnitine). C5-carnitine can be measured in dried blood spots, thus enabling universal newborn screen using tandem mass spectrometry. The diagnosis can be confirmed by molecular analysis of the IVD gene. In some patients with equivocal results, measurement of the enzyme activity in cultured skin fibroblasts may be necessary.

Treatment of the acute attack is aimed at hydration, reversal of the catabolic state (by providing adequate calories orally or intravenously), correction of metabolic acidosis, and facilitation of the isovaleric acid excretion. L -Carnitine (100 mg/kg/24 hr orally) also increases removal of isovaleric acid by forming isovalerylcarnitine, which is excreted in the urine. Because isovalerylglycine has a high urinary clearance, some centers recommend glycine supplementation (250 mg/kg/24 hr) to enhance the formation of isovalerylglycine. Temporary restriction of protein intake (<24 hr) may be beneficial in some cases. In patients with significant hyperammonemia (blood ammonia >200 µmol/L), measures that reduce blood ammonia should be employed (see Chapter 103.12 ). Renal replacement therapy may be needed if the previously described measures fail to produce significant clinical and biochemical improvement. Long-term management of IVA patients requires restriction of protein according to age-appropriate intake (recommended dietary allowance of protein). Patients benefit from carnitine supplementation with or without glycine. Normal development can be achieved with early and proper treatment.

Prenatal diagnosis can be accomplished by enzyme assay in cultured amniocytes, or if causative mutations are known, by the IVD gene analysis. Successful pregnancies with favorable outcomes have been reported. Universal newborn screening of IVA is used in the United States and other countries (see Chapter 102 ). IVA is caused by autosomal recessive pathogenic variants in IVD . The prevalence of IVA is estimated from 1 in 62,500 (in parts of Germany) to 1 in 250,000 live births (in the United States).

Multiple Carboxylase Deficiencies (Defects of Biotin Cycle)

Biotin is a water-soluble vitamin that is a cofactor for all 4 carboxylase enzymes in humans: pyruvate carboxylase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, propionyl-CoA carboxylase, and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase. The latter 2 are involved in the catabolic pathways of leucine, isoleucine, and valine (see Fig. 103.4 ).

Most of the dietary biotin is bound to proteins. Free biotin is generated in the intestine by the action of digestive enzymes, by intestinal bacteria, and perhaps by biotinidase. Biotinidase , which is found in serum and most tissues, is also essential for the recycling of biotin in the body by releasing it from the apoenzymes (carboxylases; see Fig. 103.4 ). Free biotin must form a covalent bond with the apocarboxylases to produce the activated enzyme (holocarboxylase). This binding is catalyzed by holocarboxylase synthetase. Deficiencies in this enzyme activity or in biotinidase result in malfunction of all the carboxylases and in organic acidemias.

Holocarboxylase Synthetase Deficiency

Infants with this rare autosomal recessive disorder become symptomatic in the 1st few weeks of life. Symptoms may appear as early as a few hours after birth to as late as 8 yr of age. Clinically, shortly after birth, the affected infant develops breathing difficulties (tachypnea and apnea). Feeding problems, vomiting, and hypotonia are also usually present. If the condition remains untreated, generalized erythematous rash with exfoliation and alopecia , failure to thrive, irritability, seizures, lethargy, and even coma may occur. Developmental delay is common. Immune deficiency manifests with susceptibility to infection. Urine may have a peculiar odor, which has been described “tomcat urine.” The rash, when present, helps differentiate this condition from other organic acidemias (see Fig. 103.6 ).

Laboratory findings include metabolic acidosis, ketosis, hyperammonemia, and the presence of a variety of organic acids (lactic acid, 3-methylcrotonic acid, 3-methylcrotonylglycine, tiglylglycine, 3-OH-propionic acid, methylcitric acid, and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid) in body fluids. Diagnosis is confirmed by identification of pathogenic variants in HLCS or by the enzyme assay in lymphocytes or cultured fibroblasts. Most pathogenic variants cause the enzyme to have an increased Km (Michaelis-Menten dissociation constant) for biotin; the enzyme activity in such patients can be restored by the administration of large doses of biotin. Newborn screening can identify holocarboxylase synthetase–deficient infants by detecting elevated C5-OH-carnitine on tandem mass spectrometry. In these infants, biotinidase enzymatic assay would be normal.

Treatment with biotin (10-20 mg/day orally) usually results in an improvement in clinical manifestations and biochemical abnormalities. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent irreversible neurologic damage. In some patients, however, complete resolution may not be achieved even with large doses (up to 60 mg/day) of biotin.

The gene for holocarboxylase synthetase (HLCS) is located on chromosome 21q22.13. Prenatal diagnosis can be accomplished by prenatal molecular analysis of the known pathogenic variants in HLCS or by assaying enzyme activity in cultured amniotic cells. Pregnant mothers who had previous offspring with holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency have been treated with biotin late in pregnancy. Affected infants were normal at birth, but the efficacy of prenatal treatment remains unclear.

Biotinidase Deficiency

Impaired biotinidase activity results in biotin deficiency. Affected infants may develop clinical manifestations similar to those seen in infants with holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency. Unlike the latter, however, symptoms tend to appear later, when the child is several months or years old. The delay in onset of symptoms presumably results from the presence of free biotin derived from the mother or the diet. Clinical manifestations are mostly confined to skin and the nervous system. Atopic or seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, alopecia, ataxia, seizures (usually myoclonic), hypotonia, developmental delay, optic nerve atrophy, sensorineural hearing loss, and immunodeficiency resulting from impaired T-cell function may occur. A small number of children with intractable seborrheic dermatitis and partial (15–30% activity) biotinidase deficiency, in whom the dermatitis resolved with biotin therapy, have been reported; these children were otherwise asymptomatic. Asymptomatic children and adults with this enzyme deficiency have been identified in screening programs. Most of these individuals have been shown to have partial biotinidase deficiency. With universal newborn screening leading to early identification and treatment of the affected patients, the clinical disease is predicted to become extinct.

Laboratory findings and the pattern of organic acids in body fluids resemble those associated with holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency (see above). Diagnosis can be established by measurement of the enzyme activity in the serum or by the identification of the mutant gene. Treatment with free biotin (5-20 mg/day) results in a dramatic clinical and biochemical improvement. Treatment with biotin is also suggested for individuals with partial biotinidase deficiency. The prevalence of this autosomal recessive trait is estimated at 1 in 60,000 live births. The gene for biotinidase (BTD) is located on chromosome 3p25.1. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by identification of the known pathogenic variants in BTD, or less frequently by the measurement of the enzyme activity in the amniotic cells, although in practice, a prenatal approach is rarely used.

Multiple Carboxylase Deficiency Caused by Acquired Biotin Deficiency

Acquired deficiency of biotin may occur in infants receiving total parenteral nutrition without added biotin, in patients with prolonged use of antiepileptic drugs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, carbamazepine), and in children with short bowel syndrome or chronic diarrhea who are receiving formulas low in biotin. Excessive ingestion of raw eggs may also cause biotin deficiency because the protein avidin in egg white binds biotin, decreasing its absorption. Infants with biotin deficiency may develop dermatitis, alopecia, and candidal skin infections. This condition readily responds to treatment with oral biotin.

3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency

This enzyme is 1 of the 4 carboxylases requiring biotin as a cofactor (see Fig. 103.4 ). An isolated deficiency of this enzyme must be differentiated from disorders of biotin metabolism (multiple carboxylase deficiency), which causes diminished activity of all 4 carboxylases (see earlier). 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (3-MCC) is a heteromeric enzyme consisting of α (biotin containing) and β subunits, encoded by genes MCCC1 and MCCC2 , respectively. 3-MCC deficiency can be detected in the newborn period by identifying elevated 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) in dried blood spots. Universal newborn screening using tandem mass spectrometry has identified an unexpectedly high number of infants with 3-MCC deficiency, with prevalence ranging from 1 : 2,400 to 1 : 68,000.

Clinical manifestations are highly variable, ranging from completely asymptomatic adults (including mothers of affected newborn infants), to children presenting with developmental delay without episodes of metabolic decompensation, to patients with seizures, hyperammonemia, and metabolic acidosis. In severe 3-MCC deficiency the affected infant who has been seemingly normal develops an acute episode of vomiting, hypotonia, lethargy, and convulsions after a minor infection, in some cases progressing to life-threatening complications (e.g., Reye syndrome, coma). In patients prone to developing these symptoms, the onset is usually between 3 wk and 3 yr of age. Among infants identified through newborn screening, 85–90% of children remain apparently asymptomatic. The reason for differences in outcomes is unknown. None of the symptoms reported so far could be clearly attributed to the degree of enzyme deficiency.

Laboratory findings during acute episodes include mild to moderate metabolic acidosis, ketosis, hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia, and elevated serum transaminase levels. Large amounts of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid and 3-methylcrotonylglycine are found in the urine. Urinary excretion of 3-methylcrotonic acid is not usually increased in this condition because the accumulated 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA is converted to 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid. Plasma acylcarnitine profile shows elevated 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH). Severe secondary carnitine deficiency is common. 3-MCC deficiency should be differentiated biochemically from multiple carboxylase deficiency (see earlier), in which, in addition to 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid, lactic acid and metabolites of propionic acid are also present. Diagnosis may be confirmed by molecular analysis or by measurement of the enzyme activity in cultured fibroblasts. Documentation of normal activities of other carboxylases is necessary to rule out multiple carboxylase deficiency.

Treatment of acute episodes is similar to that of isovaleric acidemia (see earlier). Hydration and measures to correct hypoglycemia and severe metabolic acidosis by infusing glucose and sodium bicarbonate should be instituted promptly. Secondary carnitine deficiency, seen in up to 50% of patients, can be corrected with L -carnitine supplementation. For symptomatic patients, some centers recommend keeping protein intake at the recommended dietary allowance in conjunction with the oral administration of L -carnitine and the proactive management of catabolic states. Normal growth and development are expected in most patients.

3-MCC deficiency is an autosomal recessive condition. The gene for α-subunit (MCCC1) is located on chromosome 3q27.1, and that for the β-subunit (MCCC2) is mapped to chromosome 5q13.2. Pathogenic variants in either of these genes result in the enzyme deficiency with overlapping clinical features.

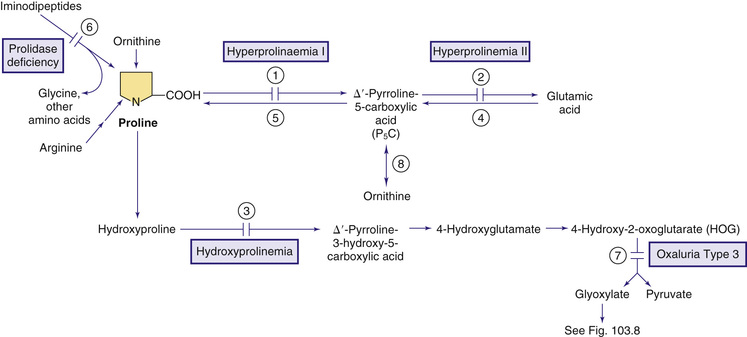

3-Methylglutaconic Acidurias

The 3-methylglutaconic acidurias are a heterogeneous group of metabolic disorders characterized by excessive excretion of 3-methylglutaconic acid in the urine (Table 103.2 ). Other metabolites found in 3-methylglutaconic aciduria patients may include 3-methylglutaric acid and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid. Current classification distinguishes primary and secondary forms. Primary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria is caused by the deficiency of mitochondrial 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase (see Fig. 103.4 ), formerly 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type I . Secondary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria can be further classified based on the underlying mechanism (e.g., defective phospholipid remodeling vs dysfunction of mitochondrial membrane) or the known molecular cause. Known secondary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria includes TAZ -related syndrome (Barth syndrome ), OPA3 -related 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (Costeff syndrome ), SERAC1 -related syndrome (MEGDEL syndrome ), TMEM70 -related syndrome, and DNAJC19 -related syndrome (DCMA syndrome ).

Table 103.2

| GROUP | DISORDER | GENE (CHROMOSOME) | PREVIOUS CLASSIFICATION | DISEASE MECHANISM | CLINICAL DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria | 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency | AUH (9q22.31) | Type I | Enzyme deficiency in the leucine degradation pathway | Depending on age, variable presentation is seen ranging from younger asymptomatic patients to older patients with progressive leukoencephalopathy |

| Secondary 3-methylglutaconic acidurias | Barth syndrome | TAZ (Xq28) | Type II | Defective phospholipid remodeling | X-linked inheritance, cardiomyopathy, endocardial fibroelastosis, proximal myopathy, failure to thrive, neutropenia, dysmorphic findings |

| Costeff syndrome | OPA3 (19q13.32) | Type III | Mitochondrial membrane dysfunction | Progressive optic nerve atrophy, chorea, spastic paraparesis, cognitive impairment | |

| MEGDEL syndrome | SERAC1 (6q25.3) | Type IV | Defective phospholipid remodeling | Progressive deafness, dystonia, spasticity, basal ganglia changes | |

| TMEM70 -related disorder | TMEM70 (8q21.11) | Type IV | Mitochondrial membrane dysfunction | Developmental delay, failure to thrive, metabolic decompensations, microcephaly, cardiomyopathy, dysmorphic findings | |

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria, not otherwise specified | Unknown | Type IV | Unknown | Variable presentation | |

| DCMA syndrome | DNAJC19 (3q26.33) | Type V | Mitochondrial membrane dysfunction | Cardiomyopathy, ataxia, optic nerve atrophy, failure to thrive |

Significant and persistent 3-methylglutaconic aciduria with negative molecular evaluation for known genetic causes represents a heterogeneous group called 3-methylglutaconic aciduria not otherwise specified awaiting further molecular characterization. Primary and secondary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria should be distinguished from mild and transient urinary elevations of 3-methylglutaconic acid seen in patients affected by other metabolic disorders, such as mitochondrial disorders of diverse etiology.

3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA Hydratase Deficiency

Two main clinical forms of 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency have been described (see Fig. 103.4 ). In the childhood form, nonspecific neurodevelopmental findings such as speech delay or regression, choreoathetoid movements, optic nerve atrophy, and mild psychomotor delay may be present. Metabolic acidosis may occur during a catabolic state. In the adulthood form, affected individuals may remain asymptomatic until the 2nd or 3rd decade of life, when a clinical picture of slowly progressing leukoencephalopathy with optic nerve atrophy, dysarthria, ataxia, spasticity, and dementia occurs. Brain MRI typically shows white matter abnormalities, which may precede the appearance of clinical symptoms by years. Asymptomatic pediatric and adult patients have also been reported. Patients excrete large amounts of 3-methylglutaconic acid and moderate amounts of 3-hydroxyisovaleric and 3-methylglutaric acids in urine. Treatment with L -carnitine may help some patients. The effectiveness of a low-leucine diet has not been established. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene for the hydratase enzyme (AUH) is mapped to chromosome 9q22.31.

Barth Syndrome (TAZ -Related Disorder)

This X-linked condition is caused by deficiency of tafazzin , a mitochondrial protein, encoded by TAZ gene. This enzyme is necessary for remodeling of immature cardiolipin into its mature form. Cardiolipin, a mitochondrial phospholipid, is critical for the integrity of inner mitochondrial membrane. Clinical manifestations of Barth syndrome, which usually occur in the 1st yr of life in a male infant, include cardiomyopathy, hypotonia, growth retardation, hypoglycemia, and mild to severe neutropenia. The onset of clinical manifestations may be as late as adulthood, but most affected individuals become symptomatic by adolescence. If patients survive infancy, relative improvement may occur with advancing age. Cognitive development is usually normal, although delayed motor function and learning disabilities are possible.

Laboratory findings include mild to moderate increases in urinary excretion of 3-methylglutaconic, 3-methylglutaric, and 2-ethylhydracrylic acids. Unlike primary 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (type I), urinary excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid is not elevated. The activity of the enzyme 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase is normal. Neutropenia is a common finding . Lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, low serum cholesterol concentration, low prealbumin, and abnormal mitochondrial ultrastructure have been shown in some patients. Total cardiolipin and subclasses of cardiolipin are very low in skin fibroblast cultures from these patients. The monolysocardiolipin/cardiolipin ratio in cultured fibroblast may be useful for establishing the diagnosis in patients with negative or equivocal molecular results. Because of its nonspecific presentation, the condition could be underdiagnosed and underreported.

The condition is inherited as an X-linked recessive trait. The gene (TAZ) has been mapped to chromosome Xq28. The modest 3-methylglutaconic aciduria seen in Barth syndrome is thought to be related to the defect in mitochondrial membrane, causing the leakage of this organic acid. Specific treatment is not available. Patients with an unsatisfactory response to medical management of cardiomyopathy may benefit from cardiac transplantation. Daily aspirin to reduce the risk of strokes has been described.

OPA3 -Related 3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria (Costeff Syndrome)

Clinical manifestations in patients with Costeff syndrome include early-onset optic nerve atrophy and later development of choreoathetoid movements, spasticity, ataxia, dysarthria, and cognitive impairment. Patients excrete moderate amounts of 3-methylglutaconic and 3-methylglutaric acids. Activity of the enzyme 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase is normal. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene for this condition (OPA3) is mapped to chromosome 19q13.32. Pathogenic variants in OPA3 are thought to cause electron transport chain dysfunction. Treatment is supportive.

Disorders Formerly Described as 3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria Type IV

3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type IV represents a group of disorders with diverse genetic etiology. Two disorders in this group have been linked to specific molecular etiology, while other conditions are still awaiting the discovery of their underlying molecular defect.

MEGDEL syndrome (3-me thylg lutaconic aciduria with d eafness, e ncephalopathy and L eigh-like) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by deleterious mutations in SERAC1 on chromosome 6q25.3. Affected patients experience progressive deafness, dystonia, spasticity and basal ganglia injury similar to patients with Leigh syndrome. Treatment is symptomatic.

TMEM70 -related disorder is also inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Pathogenic variants in TMEM70 result in the mitochondrial complex V deficiency, although the exact mechanism of disease is unknown. Clinical manifestations include developmental delay, developmental regression, Reye syndrome–like episodes, intellectual disability, failure to thrive, microcephaly, cardiomyopathy, and dysmorphic findings. Patients are prone to metabolic decompensation, characterized by hyperammonemia (up to 900 µmol/L) and lactic acidosis, which are more common in the 1st yr of life. Acute hyperammonemic episodes are treated with intravenous glucose, lipid emulsion, ammonia-scavenging drugs, and occasionally require hemodialysis. Long-term therapy that has been described includes L -carnitine, coenzyme Q10 , and bicarbonate substitution (e.g., citric acid/sodium citrate). Patients require interval echocardiographic and electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring to enable early diagnosis and management of cardiomyopathy.

DCMA Syndrome (DNAJC19 -Related Syndrome, 3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria Type V)

DCMA syndrome (d ilated c ardiom yopathy with a taxia) is a novel autosomal recessive disorder identified in patients of the Canadian Dariusleut Hutterite ancestry living in The Great Plains of North America. As the disorder's abbreviated name suggests, affected individuals present with dilated cardiomyopathy, long QTc interval, and CNS involvement. Neurologic symptoms include intellectual disability, cerebellar involvement, and optic atrophy. Growth is affected in all patients. Intrauterine growth restriction is seen in up to 50% of patients. Cryptorchidism and hypospadias are frequent findings in affected boys. Urine organic acid assay reveals increased 3-methylglutaconic acid and 3-methylglutaric acid. Pathogenic variants in DNAJC19 (3q26.33) are the underlying cause of DCMA syndrome. Treatment is symptomatic. Interval echocardiography and ECG can prospectively identify patients requiring treatment of cardiomyopathy and long QTc interval.

β-Ketothiolase (3-Oxothiolase) Deficiency (Mitochondrial Acetoacetyl-CoA Thiolase [T2 ] Deficiency)

This reversible mitochondrial enzyme is involved in the final steps of isoleucine catabolism and in ketolysis. In the isoleucine catabolic pathway, the enzyme cleaves 2-methylacetoacetyl-CoA into propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA (see Fig. 103.4 ). In the fatty acid oxidation pathway, the enzyme generates 2 moles of acetyl-CoA from 1 mole of acetoacetyl-CoA (Fig. 103.7 ). The same enzyme synthesizes 2-methyacetoacetate-CoA and acetoacetyl-CoA in the reverse direction. The hallmark of this disorder is ketoacidosis , often triggered by infections, prolonged fasting, and large protein load. The mechanism of ketosis in this condition is incompletely understood, because in this enzyme deficiency one expects impaired ketone formation (Fig. 103.7 ). It is postulated that excess acetoacetyl-CoA produced from other sources can be used as a substrate for 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthesis in the liver.

Clinical manifestations are quite variable, ranging from mild cases showing normal development to severe episodes of acidosis starting in the 1st yr of life causing severe cognitive impairment. Unless identified on the newborn screening, affected children present with intermittent episodes of unexplained ketoacidosis. These episodes usually occur after an intercurrent infection and typically respond promptly to intravenous fluids and bicarbonate therapy. Mild to moderate hyperammonemia may also be present during attacks. Both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia have been reported in isolated cases. The child may be completely asymptomatic between episodes and may tolerate a normal protein diet. Cognitive development is normal in most children. The episodes may be misdiagnosed as salicylate poisoning because of the similarity of the clinical findings and the interference of elevated blood levels of acetoacetate with the colorimetric assay for salicylate.

Laboratory findings during the acute attack include ketoacidosis, and hyperammonemia. Findings of ketones in the urine and hyperglycemia may be interpreted as diabetic ketoacidosis, and the high index of suspicion is needed to identify this metabolic disorder. Urine organic acid assay can provide clues leading to correct diagnosis. Urine contains large amounts of 2-methylacetoacetate and its decarboxylated products butanone, 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyrate, and tiglylglycine. Lower concentrations of urinary metabolites can be seen when patients are stable. Mild hyperglycinemia may also be present. Plasma acylcarnitine profile show elevations of C5 : 1 and C5-OH carnitines, although these metabolites can normalize in between catabolic episodes. Minimal elevations of C5 : 1 and C5-OH carnitines can result in false-negative results on the newborn screening of affected infants who were clinically well at the time of blood collection. The clinical and biochemical findings should be differentiated from those seen with propionic and methylmalonic acidemias (see later).

Treatment of acute episodes includes hydration. Recalcitrant metabolic acidosis can be severe enough to require infusion of bicarbonate. A 10% glucose solution with the appropriate electrolytes is used to suppress protein catabolism, lipolysis, and ketogenesis. Restriction of protein intake to age-appropriate physiologic requirements is recommended for long-term therapy. Oral L -carnitine (50-100 mg/kg/24 hr) is also recommended to prevent possible secondary carnitine deficiency. Long-term prognosis for achieving normal quality of life seems very favorable. Successful pregnancy with a normal outcome has been reported.

β-Ketothiolase deficiency is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and may be more prevalent than previously appreciated. The gene (ACAT1) for this enzyme is located on chromosome 11q22.3. Diagnosis may be confirmed by molecular analysis of the ACAT1 gene or using enzyme assay of leukocytes or cultured fibroblasts.

Cytosolic Acetoacetyl-CoA Thiolase Deficiency

This enzyme catalyzes the cytosolic production of acetoacetyl-CoA from two moles of acetyl-CoA (see Fig. 103.7 ). Cytosolic acetoacetyl-CoA is the precursor of hepatic cholesterol synthesis. Cytosolic acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase should be differentiated from the mitochondrial thiolase (see earlier and Fig. 103.4 ). Clinical manifestations in patients with this very rare enzyme deficiency have been incompletely characterized. Patients may present with severe progressive developmental delay, hypotonia, and choreoathetoid movements in the 1st few months of life. Laboratory findings are nonspecific; elevated levels of lactate, pyruvate, acetoacetate, and 3-hydroxybutyrate may be found in blood and urine. One patient had normal levels of acetoacetate and 3-hydroxybutyrate. Diagnosis can be aided by demonstrating a deficiency in cytosolic thiolase activity in liver biopsy or in cultured fibroblasts or by DNA analysis. No effective treatment has been described, although a low-fat diet helped to diminish ketosis in one patient.

Mitochondrial 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase Deficiency

This enzyme catalyzes synthesis of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria. This is a critical step in ketone body synthesis in the liver (see Fig. 103.7 ). A few patients with deficiency of this enzyme have been reported. The principal clinical syndrome is hypoketotic hypoglycemia triggered by physiologic stress, such as infections or fasting. Age at presentation has ranged from infancy to 6 yr. Children tend to be asymptomatic before these episodes and with appropriate management can remain stable after the recovery (except for mild hepatomegaly with fatty infiltration). Future episodes can be prevented by avoiding prolonged fasting during ensuing intercurrent illnesses. Hepatomegaly is a consistent physical finding in these patients. Laboratory findings include hypoglycemia, acidosis with mild or no ketosis, elevated levels in liver function tests, and massive dicarboxylic aciduria. The clinical and laboratory findings may be confused with fatty acid metabolism defects (see Chapter 104.1 ). In contrast to the latter, in patients with HMG-CoA synthase deficiency the blood concentrations of acylcarnitine conjugates are negative for acylcarnitine findings characteristic of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Treatment of the secondary carnitine deficiency with L -carnitine supplementation can result in elevated plasma acetylcarnitine (C2-carnitine), likely reflecting intracellular accumulation of acetyl-CoA. A controlled fasting study can produce the clinical and biochemical abnormalities.

Treatment consists of provision of adequate calories and avoidance of prolonged periods of fasting. No dietary protein restriction was needed.

The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene (HMGCS2) for this enzyme is located on chromosome 1p12. The condition should be considered in any child with fasting hypoketotic hypoglycemia and may be more common than appreciated.

3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Lyase Deficiency (3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaric Aciduria)

3-HMG-CoA lyase (see Fig. 103.4 ) catalyzes the conversion of 3-HMG-CoA to acetoacetate and is a rate-limiting enzyme for ketogenesis (see Fig. 103.7 ). The deficiency of this enzyme is a rare disorder seen with increased frequency in Saudi Arabia, the Iberian Peninsula, and in Brazil in patients of Portuguese ancestry. Clinically, approximately 30% develop symptoms in the 1st few days of life, and >60% of patients become symptomatic between 3 and 11 mo of age. Infrequently, patients may remain asymptomatic until adolescence. With the addition of 3-HMG-CoA lyase deficiency to the newborn screening using C5-OH-carnitine, many infants are identified presymptomatically in the newborn period. Similar to 3-HMG-CoA synthase deficiency, patients affected by 3-HMG-CoA lyase deficiency may present with acute hypoketotic hypoglycemia. Episodes of vomiting, severe hypoglycemia, hypotonia, acidosis with mild or no ketosis, and dehydration may rapidly lead to lethargy, ataxia, and coma. These episodes often occur during a catabolic state such as prolonged fasting or an intercurrent infection. Hepatomegaly is common. These manifestations may be mistaken for Reye syndrome or fatty acid oxidation defects such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Long-term complications can include dilated cardiomyopathy, hepatic steatosis, and pancreatitis. Development can be normal, but intellectual disability and seizures with abnormalities in the white matter seen on MRI have been observed in patients after prolonged episodes of hypoglycemia.

Laboratory findings include hypoglycemia, moderate to severe hyperammonemia, and acidosis. There is mild or no ketosis (see Fig. 103.7 ). Urinary excretion of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid and other proximal intermediate metabolites of leucine catabolism (3-methylglutaric acid, 3-methylglutaconic acid, and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid) is markedly increased, causing the urine to smell like cat urine . Glutaric and dicarboxylic acids may also be increased in urine during acute attacks. Secondary carnitine deficiency is common. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. 3-HMG-CoA lyase is encoded by gene HMGCL . Diagnosis may be confirmed by molecular analysis of HMGCL or by enzyme assay in cultured fibroblasts, leukocytes, or liver specimens. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by molecular DNA analysis if the familial pathogenic variants are known or by enzymatic assay of the cultured amniocytes or a chorionic villi biopsy.

Treatment of acute episodes includes hydration, infusion of glucose to control hypoglycemia, provision of adequate calories, and administration of bicarbonate to correct acidosis. Hyperammonemia should be treated promptly (see Chapter 103.12 ). Renal replacement therapy may be required in patients with severe recalcitrant hyperammonemia. Restriction of protein and fat intake is recommended for long-term management. Oral administration of L -carnitine (50-100 mg/kg/24 hr) prevents secondary carnitine deficiency. Prolonged fasting should be avoided.

Succinyl-CoA:3-Oxoacid-CoA Transferase Deficiency

Succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT ) deficiency and β-ketothiolase deficiency collectively are referred to as ketone utilization disorders. SCOT participates in the conversion of ketone bodies (acetoacetate and 3-hydroxybutyrate) generated in liver mitochondria into acetoacetyl-CoA in the nonhepatic tissues (see Fig. 103.7 ). A deficiency of this enzyme results in the accumulation of ketone bodies, ketoacidosis, increased utilization of glucose, and hypoglycemia. During fasting, patients tend to have a proportional elevation of plasma free fatty acids. More than 30 patients with SCOT deficiency have been reported to date. The condition may not be rare because many cases may be mild and may remain undiagnosed. SCOT deficiency can be distinguished from β-ketothiolase deficiency by the absence of 2-methylacetoacetate, 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyrate, and tiglylglycine, characteristic of the latter disorder. Plasma acylcarnitine profile tends to show no specific abnormalities.

A common clinical presentation is an acute episode of severe ketoacidosis in an infant who had been growing and developing normally. About half the patients become symptomatic in the 1st wk of life, and practically all become symptomatic before 2 yr of age. The acute episode is often precipitated by a catabolic state triggered by an infection or prolonged fasting. Without treatment, the ketoacidotic episode can result in death. A chronic subclinical ketosis may persist between the attacks. Development is usually normal, although severe and recurrent episodes of ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia can predispose patients to neurocognitive impairment.

Laboratory findings during the acute episode are nonspecific and include metabolic acidosis and ketonuria with high levels of acetoacetate and 3-hydroxybutyrate in blood and urine. No other organic acids are found in the blood or in the urine. Blood glucose levels are usually normal, but hypoglycemia has been reported in some affected newborn infants with severe ketoacidosis. Plasma amino acids and plasma acylcarnitine profile are usually normal. Severe SCOT deficiency can be accompanied by ketosis even when patients are clinically stable. This condition should be considered in any infant with unexplained bouts of ketoacidosis. Diagnosis can be established by molecular analysis of OXCT1 or by demonstrating a deficiency of enzyme activity in cultured fibroblasts. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

Treatment of acute episodes consists of rehydration with solutions containing dextrose, correction of acidosis, and the provision of a diet adequate in calories. Long-term treatment should include high-carbohydrate diet and avoidance of prolonged fasting and administration of dextrose before anticipated or during established catabolic states.

Mevalonate Kinase Deficiency

Mevalonic acid, an intermediate metabolite of cholesterol synthesis, is converted to 5-phosphomevalonic acid by the action of the enzyme mevalonate kinase (MVK) (see Fig. 103.7 ). Based on clinical manifestations and degree of enzyme deficiency, 2 conditions have been recognized: mevalonic aciduria and hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome. Both disorders are accompanied by recurrent fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, mucocutaneous manifestations, and lymphadenopathy. Patients with mevalonic aciduria also show growth retardation and nervous system involvement. In practice, the 2 disorders represent the 2 ends of the spectrum.

Mevalonic Aciduria

Clinical manifestations include failure to thrive, growth retardation, intellectual disability, hypotonia, ataxia, myopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, cataracts, and facial dysmorphisms (dolichocephaly, frontal bossing, low-set ears, downward slanting of eyes, long eyelashes). Most patients experience recurrent crises characterized by fever, vomiting, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, edema, and morbilliform rash. These episodes typically last 2-7 days and recur up to 25 times a year. Death may occur during these crises.

Laboratory findings include marked elevation of mevalonic acid in urine; the concentration of urinary mevalonic acid ranges between 500 and 56,000 mmol/mol of creatinine (normal: <0.3 mmol/mol of creatinine). Plasma levels of mevalonic acid are also greatly increased (as high as 540 µmol/L; normal: <0.04 µmol/L). Mevalonic acid levels tend to correlate with the severity of the condition and increase during crises. Serum cholesterol concentration is normal or mildly decreased. Serum concentration of creatine kinase can be greatly increased. Inflammatory markers are elevated during the crises. Brain MRI may reveal progressive atrophy of the cerebellum.

Diagnosis may be confirmed by DNA analysis or by assaying the MVK activity in lymphocytes or cultured fibroblasts. The enzyme activity in this form of the condition is below the detection level. Treatment with high doses of prednisone helps in the acute crises, but due to side effects, it is not routinely used long term. Etanercept (tumor necrosis factor inhibitor) and anakinra (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) have shown to be effective in bringing significant clinical improvement. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by identifying known familiar pathogenic variants in MVK, by measurement of mevalonic acid in the amniotic fluid, or by assaying the enzyme activity in cultured amniocytes or chorionic villi samples. The gene (MVK ) for the enzyme is on chromosome 12q24.11.

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D Syndrome (Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D and Periodic Fever Syndrome)

Some pathogenic variants of mevalonic kinase gene (MVK) cause milder enzyme deficiency and produce the clinical picture of periodic fever with hyperimmunoglobulinemia D. These patients have periodic bouts of fever associated with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, arthralgia, arthritis, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and morbilliform rash (even petechiae and purpura), which usually start before 1 yr of age. The attacks can be triggered by vaccination, minor trauma, or stress and can occur every 1-2 mo, lasting 2-7 days. Patients are free of symptoms between acute attacks. The diagnostic laboratory finding is elevation of serum immunoglobulin D (IgD). IgA is also elevated in 80% of patients. During acute attacks, leukocytosis, increased C-reactive protein, and mild mevalonic aciduria may be present. High concentrations of serum IgD help differentiate this condition from familial Mediterranean fever. See Chapter 188 for treatment recommendations.

Propionic Acidemia (Propionyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency)

Propionic acid is an intermediate metabolite of isoleucine, valine, threonine, methionine, odd-chain fatty acids, and side chains of cholesterol. Normally, propionic acid in the form of propionyl-CoA undergoes carboxylation to D -methylmalonyl-CoA, catalyzed by the mitochondrial enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase. This enzyme requires biotin as a cofactor; thus the disorders of biotin metabolism, among other findings, can also result in elevation of propionic acid metabolites (see Fig. 103.4 ). Propionyl-CoA carboxylase is a multimeric enzyme composed of 2 nonidentical subunits, α and β, encoded by 2 genes, PCCA and PCCB , respectively. Pathogenic variants in propionyl-CoA carboxylase result in the disorder called propionic acidemia.

Clinical findings of propionic acidemia are not specific to this disorder only. In the severe form, patients develop symptoms in the 1st few days of life. Poor feeding, vomiting, hypotonia, lethargy, dehydration, a sepsis-like picture, and clinical signs of severe ketoacidosis progress rapidly to coma and death. Seizures occur in approximately 30% of affected infants. If an infant survives the first attack, similar episodes of metabolic decompensation may occur during an intercurrent infection, trauma, surgery, prolonged fasting, severe constipation, or after ingestion of a high-protein diet. Moderate to severe intellectual disability and neurologic manifestations reflective of extrapyramidal (dystonia, choreoathetosis, tremor) and pyramidal (paraplegia) dysfunction are common sequelae in the survivors. Neuroimaging shows that these abnormalities, which often occur after an episode of metabolic decompensation, are the result of damage to the basal ganglia, especially to the globus pallidus. This phenomenon has been referred to as metabolic stroke . This is the main cause of neurologic sequelae seen in the surviving affected children. Additional long-term complications include failure to thrive, optic nerve atrophy, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, and osteopenia.

In the milder form, episodes of metabolic decompensation are less frequent, but these children are still at risk to develop intellectual disability, seizures, long QTc interval, and severe cardiomyopathy. Universal newborn screening can identify propionic acidemia by detecting elevated propionylcarnitine (C3) in dried blood spots. However, in patients with the mild form of propionic acidemia, propionylcarnitine could remain below the cutoff value set by the screening laboratory, resulting in a false-negative result. Therefore, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this disorder and follow up with a biochemical evaluation of infants and children presenting with unexplained ketosis or metabolic acidosis.

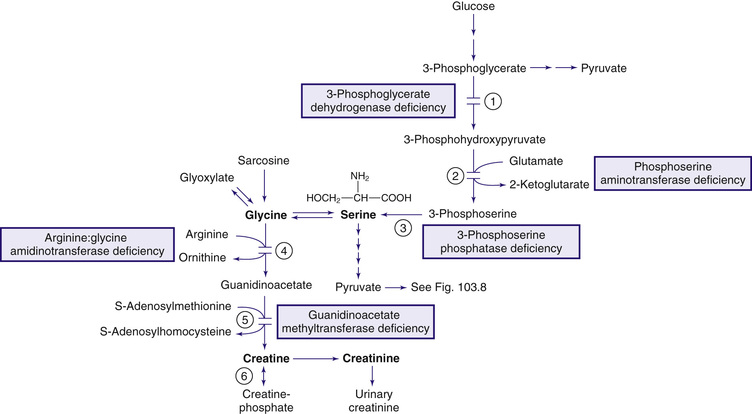

Laboratory findings during the acute attack include various degrees of metabolic acidosis, often with a large anion gap, ketosis, ketonuria, hypoglycemia, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. Moderate to severe hyperammonemia is common; plasma ammonia concentrations usually correlate with the severity of the disease. In contrast to other causes of hyperammonemia, plasma concentration of glutamine tends to be within normal limits or decreased. Presence of severe metabolic acidosis and normal to reduced plasma glutamine help differentiate propionic academia from hyperammonemia caused by urea cycle defects. Measurement of plasma ammonia is especially helpful in planning therapeutic strategy during episodes of exacerbation in a patient whose diagnosis has been established. Mechanisms of hyperammonemia in propionic acidemia are not well understood but are likely related to the perturbed biochemical and pH environment of the mitochondrial matrix, where the proximal part of urea cycle resides. Glycine concentration can be elevated in all body fluids (blood, urine, CSF) and possibly are the result of the inhibited glycine cleavage system in the hepatic mitochondria (Fig. 103.8 ). Glycine elevation has also been observed in patients with methylmalonic acidemia. These disorders were collectively referred to as ketotic hyperglycinemia in the past before the specific enzyme deficiencies were elucidated. Mild to moderate increase in blood lactate and lysine may also be present in these patients. Concentrations of propionylcarnitine, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, and methylcitric acid (presumably formed through condensation of propionyl-CoA with oxaloacetic acid) are greatly elevated in the plasma and urine of infants with propionic acidemia. Propionylglycine and other intermediate metabolites of branched-chain amino acid catabolism, such as tiglylglycine, can also be found in urine. Moderate elevations in blood levels of glycine, and previously mentioned organic acids can persist between the acute attacks. Brain imaging may reveal cerebral atrophy, delayed myelination, and abnormalities in the globus pallidus and other parts of the basal ganglia.

The diagnosis of propionic acidemia should be differentiated from multiple carboxylase deficiencies (see earlier and Fig. 103.6 ). In addition to propionic acid metabolites, infants with the latter condition excrete large amounts of lactic acid, 3-methylcrotonylglycine, and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid. The presence of hyperammonemia may suggest a genetic defect in the urea cycle enzymes. Infants with defects in the urea cycle are usually not acidotic (see Fig. 103.1 ) and have elevated levels of plasma glutamine. The definitive diagnosis of propionic acidemia can be established through molecular analysis of PCCA and PCCB or by measuring the enzyme activity in leukocytes or cultured fibroblasts.

Treatment of acute episodes of metabolic decompensation includes hydration with solutions containing glucose, correction of acidosis, and amelioration of the catabolic state by provision of adequate calories through enteral or parenteral hyperalimentation. A brief restriction of protein intake, no more than 24 hr, is often necessary. Depending on the clinical status, gradual reintroduction of protein is recommended. If enteral feedings cannot be tolerated after 48 hours of protein restriction, parenteral nutrition should be instituted to achieve the age-specific recommended dietary protein intake. Patients unable to tolerate the recommended dietary allowance of protein can receive specialized medical foods free of isoleucine, valine, threonine, and methionine. The composition and the amount of protein vary among patients. The metabolic diet composition can be adjusted by monitoring growth and plasma amino acids drawn 3-4 hr after the typical feeding. Some patients may benefit from the suppression of propionogenic gut microflora. This can be achieved by oral antibiotics such as oral neomycin or metronidazole. Prolonged use of metronidazole should be avoided because it has been associated with reversible peripheral neuropathy and increased QTc interval. The risk of QTc prolongation can be problematic in propionic acidemia patients, who are at risk for cardiomyopathy and long QT interval. Baseline and interval electrocardiograms (ECGs) are recommended before and after initiation of the metronidazole therapy. Patients may benefit from management of constipation.

Patients with propionic acidemia often develop secondary carnitine deficiency, presumably as a result of the urinary loss of propionylcarnitine. Administration of L -carnitine (50-100 mg/kg/24 hr orally or intravenously) helps restore free carnitine in blood. In patients with concomitant hyperammonemia, measures to reduce blood ammonia should be employed (see Chapter 103.12 ). Very ill patients with severe acidosis and hyperammonemia require hemodialysis to remove ammonia and other toxic compounds rapidly and efficiently. N -carbamoylglutamate (carglumic acid) and nitrogen scavengers (sodium benzoate, sodium phenylacetate, sodium phenylbutyrate) can aid in the treatment of acute hyperammonemia. Although no infant with propionic acidemia has been found to be responsive to biotin, this compound should be administered (10 mg/24 hr orally) to all infants during the first attack and until the diagnosis is established and multiple carboxylase deficiency ruled out.

Long-term treatment consists of a low-protein diet meeting age-specific recommended dietary allowance and administration of L -carnitine (50-100 mg/kg/24 hr orally). Some centers manage mild cases of propionic acidemia without medical foods, opting for only restricting the protein intake to recommended dietary allowance. Patients unable to tolerate the recommended dietary intake of protein may require medical foods free of propionate precursors (isoleucine, valine, methionine, and threonine). Excessive use of medical foods while restricting natural-source protein may cause a deficiency of the essential amino acids, especially isoleucine and valine, which may cause a condition resembling acrodermatitis enteropathica (see Chapter 691 ). Overrestriction of methionine, especially in the 1st years of life, may contribute to the reduced brain growth and microcephaly. To avoid this problem, natural proteins should comprise most of the dietary protein. Some patients may require bicarbonate substitution (e.g., citric acid/sodium citrate) to correct chronic acidosis. The concentration of plasma ammonia usually normalizes between attacks, although some patients may experience mild chronic hyperammonemia. Acute attacks triggered by infections, fasting, trauma, stress, constipation, or dietary indiscretions should be treated promptly and aggressively. Close monitoring of plasma ammonia, plasma amino acids obtained 3-4 hr after the last typical meal (especially isoleucine, leucine, valine, threonine, and methionine), and growth parameters is necessary to ensure the diet is appropriate. Orthotopic liver transplantation is used in clinically unstable patients experiencing recurrent hyperammonemia, frequent metabolic decompensations, and poor growth. Liver transplantation does not cure propionic acidemia, and lifelong dietary management and proactive management during periods of significant metabolic stress are recommended.

Long-term prognosis is guarded. Death may occur during an acute attack. Normal psychomotor development is possible in the mild form identified through newborn screening. Children identified clinically may manifest some degree of permanent neurodevelopmental deficit, such as tremor, dystonia, chorea, and spasticity despite adequate therapy. These neurologic findings may be the sequelae of a metabolic stroke occurring during an acute decompensation. Long QTc interval as well as cardiomyopathy with potential progression to heart failure, fatal arrhythmias, and death may develop in older affected children despite adequate metabolic control. Acute pancreatitis is a common and severe complication in propionic acidemia. Osteoporosis can predispose to fractures, which can occur even after minimal mechanical stress.

Prenatal diagnosis can be achieved by identification of the known familial pathogenic variants in PCCA or PCCB or by measuring the enzyme activity in cultured amniotic cells or in samples of uncultured chorionic villi.

Propionic acidemia is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and has a worldwide prevalence of 1 : 105,000 to 1 : 250,000 live births. It is more prevalent in Greenlandic Inuits (1 : 1,000) and in some Saudi Arabian tribes (1 : 2,000 to 1 : 5,000 live births). The gene for the α-subunit (PCCA) is located on chromosome 13q32.3 and that of the β-subunit (PCCB) is mapped to chromosome 3q22.3. Pathogenic variants in either gene result in similar clinical and biochemical manifestations. Although pregnancies with normal outcomes have been reported, the perinatal period poses special risks to females with propionic acidemia because of hyperemesis gravidarum, worsening cardiomyopathy, changing protein requirements, and risk of metabolic decompensation.

Isolated Methylmalonic Acidemias

Methylmalonic acidemias are a group of metabolic disorders of diverse etiology characterized by impaired conversion of methylmalonyl-CoA into succinyl-CoA. Propionyl-CoA derived from catabolism of isoleucine, valine, threonine, methionine, side chain of cholesterol, and odd-chain fatty acids is catalyzed by propionyl-CoA carboxylase to form D -methylmalonyl-CoA. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase then converts D -methylmalonyl-CoA to its enantiomer L -methylmalonyl-CoA. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency is a rare disorder associated with persistent elevations of propionate-related metabolites and methylmalonic acid. It may present with metabolic acidosis, ketosis, but known patients appear more clinically stable than those with severe forms of methylmalonic acidemia.

In the next biochemical step, L -methylmalonyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (see Fig. 103.4 ). The latter enzyme requires adenosylcobalamin, a metabolite of vitamin B12 , as a coenzyme. Deficiency of either the mutase or its coenzyme results in the accumulation of methylmalonic acid and its precursors in body fluids. Two biochemical forms of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiencies have been identified. These are designated mut 0 , referring to no detectable enzyme activity, and mut− , indicating residual, although insufficient, mutase activity. Patients with methylmalonic acidemia due to deficiency of the mutase apoenzyme (mut 0 ) are not responsive to hydroxocobalamin therapy.

In the remaining methylmalonic acidemia patients, the defect resides in the formation of adenosylcobalamin from dietary vitamin B12 . The absorption of dietary vitamin B12 in the terminal ileum requires intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by the gastric parietal cells. It is transported in the blood by haptocorrin and transcobalamin II. The transcobalamin II–cobalamin complex (TCII-Cbl) is recognized by a specific receptor on the cell membrane (transcobalamin receptor encoded by CD320 ) and enters the cell by endocytosis. In the lysosome, TCII-Cbl is hydrolyzed, and, with the participation of LMBRD1 (cbl F) and ABCD4 (cbl J), free cobalamin is released into the cytosol (see Fig. 103.4 ). Pathogenic variants in either LMBRD1 or ABCD4 genes result in impaired release of cobalamin from lysosomes. In the cytoplasm, cobalamin binds to the MMACHC protein (see cbl C later), which removes a moiety attached to cobalt in the cobalamin molecule and reduces the cobalt from oxidation state +3 (cob[III]alamin) to +2 (cob[II]alamin). It then enters the mitochondria, where it is catalyzed by MMAB (cbl B) and MMAA (cbl A) to form adenosylcobalamin, a coenzyme for methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. The other arm of the pathway directs cytosolic cobalamin toward methionine synthase reductase (cbl E), which forms methylcobalamin, acting as a coenzyme for methionine synthase (cbl G, see Fig. 103.3 ). The MMADHC protein (see cbl D) appears to play a role in determining whether cobalamin enters the mitochondria or remains in the cytoplasm.

The uptake of TCII-Cbl by cells is impaired in individuals with pathogenic variants affecting transcobalamin receptor (CD320), which is located on the cell surface. Individuals homozygous for pathogenic variants in the CD320 gene encoding the transcobalamin receptor may have mild elevations of methylmalonic acid in blood and urine. These patients can be identified by the newborn screen based on the elevated propionylcarnitine (C3). In transcobalamin receptor deficiency , methylmalonic acid levels and plasma propionylcarnitine tend to normalize in the 1st yr of life. It is not clear whether there is a long-term clinical phenotype associated with this defect.

Nine different defects in the intracellular metabolism of cobalamin have been identified. These are designated cbl A through cbl G, cbl J, and cbl X, where cbl stands for a defect in any step of cobalamin metabolism. The cbl A, cbl B, and cbl D variant 2 defects cause methylmalonic acidemia alone . In patients with cbl C, classic cbl D, cbl F, cbl J, and cbl X defects, synthesis of both adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin is impaired, resulting in combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria. The cbl D variant 1, cbl E, and the cbl G defects affect only the synthesis of methylcobalamin, resulting in homocystinuria without methylmalonic aciduria (see Chapter 103.3 ).

Biochemical manifestations of patients with isolated methylmalonic acidemia caused by mut 0 , mut − , cbl A, cbl B, and cblD variant 2 overlap. The wide variations in severity of clinical course range from very sick newborn infants to apparently asymptomatic adults. In severe forms, lethargy, feeding problems, vomiting, a sepsis-like picture, tachypnea (from metabolic ketoacidosis), and hypotonia may develop in the 1st few days of life and may progress to hyperammonemic encephalopathy, coma, and death if left untreated. Infants who survive the first attack may go on to develop similar acute metabolic episodes during a catabolic state such as infection or prolonged fasting or after ingestion of a high-protein diet. In certain situations, such acute events can cause a sudden injury of the basal ganglia (movement centers in CNS), a metabolic stroke, resulting in a debilitating movement disorder. Between the acute attacks, the patient usually continues to exhibit hypotonia and feeding problems with failure to thrive, while other complications of the disease occur with age, including recurrent episodes of pancreatitis, bone marrow suppression, osteopenia, and optic nerve atrophy. Chronic renal failure and tubulointerstitial nephritis necessitating renal transplant have been reported in older patients. Renal complications are more severe in patients with the mut 0 and severe cbl B forms of methylmalonic acidemia. In milder forms, patients may present later in life with hypotonia, failure to thrive, and developmental delay. Neurocognitive development of patients with mild methylmalonic acidemia may remain within the normal range.

The episodic nature of the condition and its biochemical abnormalities in some patients may be confused with those of ethylene glycol (antifreeze) ingestion. The peak of propionate in a blood sample from an infant with methylmalonic acidemia has been mistaken for ethylene glycol when the sample was assayed by gas chromatography without mass spectrometry.

Laboratory findings include ketosis, metabolic acidosis, hyperglycinemia, hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and the presence of large quantities of methylmalonic acid in body fluids (see Fig. 103.6 ). Metabolites of propionic acid (3-hydroxypropionate and methylcitrate) are also found in the urine. Plasma acylcarnitine profile reveals elevated propionylcarnitine (C3) and methylmalonylcarnitine (C4DC). Hyperammonemia in methylmalonic acidemia may be confused with a urea cycle disorder. However, patients with defects in urea cycle enzymes are typically not acidotic and tend to have high plasma glutamine (see Fig. 103.12 ). The reason for hyperammonemia is not well understood, but it is likely related to the inhibition of proximal urea cycle in the mitochondrial matrix.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by identifying pathogenic variants in the causal gene, by measuring propionate incorporation with complementation analysis in cultured fibroblasts, and by measuring the specific activity of the mutase enzyme in biopsies or cell extracts.