The Human Genome

Daryl A. Scott, Brendan Lee

The human genome has approximately 20,000 genes that encode the wide variety of proteins found in the human body. Reproductive or germline cells contain 1 copy (N) of this genetic complement and are haploid , whereas somatic (nongermline) cells contain 2 complete copies (2N) and are diploid . Genes are organized into long segments of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA ), which, during cell division, are compacted into intricate structures together with proteins to form chromosomes. Each somatic cell has 46 chromosomes: 22 pairs of autosomes , or nonsex chromosomes, and 1 pair of sex chromosomes (XY in a male, XX in a female). Germ cells (ova or sperm) contain 22 autosomes and 1 sex chromosome, for a total of 23. At fertilization, the full diploid chromosome complement of 46 is again realized in the embryo.

Most of the genetic material is contained in the cell's nucleus. The mitochondria (the cell's energy-producing organelles) contain their own unique genome. The mitochondrial chromosome consists of a double-stranded circular piece of DNA, which contains 16,568 base pairs (bp) of DNA and is present in multiple copies per cell. The proteins that occupy the mitochondria are produced either in the mitochondria, using information contained in the mitochondrial genome, or are produced outside of the mitochondria, using information contained in the nuclear genome, and then transported into the organelle. Sperm do not usually contribute mitochondria to the developing embryo, so all mitochondria are maternally derived, and a child's mitochondrial genetic makeup derives exclusively from the child's biological mother (see Chapter 106 ).

Fundamentals of Molecular Genetics

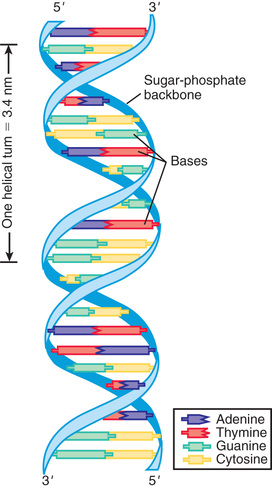

DNA consists of a pair of chains of a sugar-phosphate backbone linked by pyrimidine and purine bases to form a double helix (Fig. 96.1 ). The sugar in DNA is deoxyribose. The pyrimidines are cytosine (C) and thymine (T); the purines are guanine (G) and adenine (A). The bases are linked by hydrogen bonds such that A always pairs with T and G with C. Each strand of the double helix has polarity, with a free phosphate at one end (5′) and an unbonded hydroxyl on the sugar at the other end (3′). The 2 strands are oriented in opposite polarity in the double helix.

The replication of DNA follows the pairing of bases in the parent DNA strand. The original 2 strands unwind by breaking the hydrogen bonds between base pairs. Free nucleotides, consisting of a base attached to a sugar-phosphate chain, form new hydrogen bonds with their complementary bases on the parent strand; new phosphodiester bonds are created by enzymes called DNA polymerases. Replication of chromosomes begins simultaneously at multiple sites, forming replication bubbles that expand bidirectionally until the entire DNA molecule (chromosome) is replicated. Errors in DNA replication, or mutations induced by environmental mutagens such as irradiation or chemicals, are detected and potentially corrected by DNA repair systems.

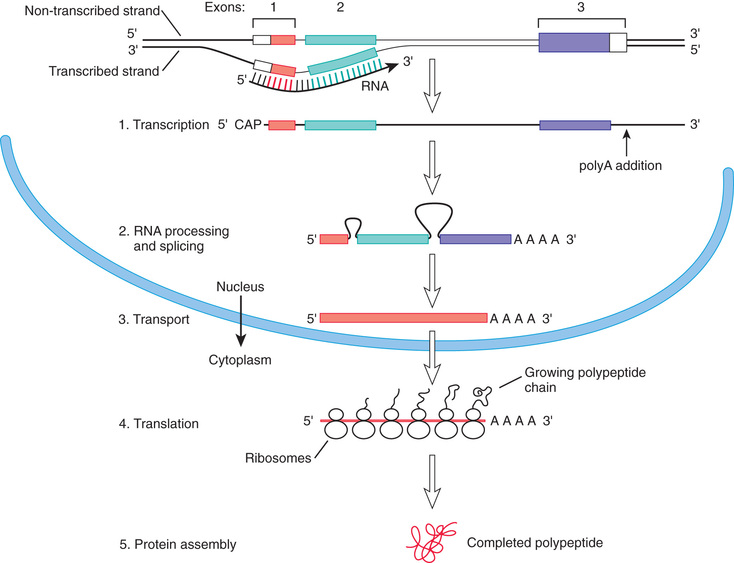

The central tenet of molecular genetics is that information encoded in DNA, predominantly located in the cell nucleus, is transcribed into messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA ), which is then transported to the cytoplasm, where it is translated into protein. A prototypical gene consists of a regulatory region, segments called exons that encode the amino acid sequence of a protein, and intervening segments called introns (Fig. 96.2 ).

Transcription is initiated by attachment of ribonucleic acid (RNA ) polymerase to the promoter site upstream of the beginning of the coding sequence. Specific proteins bind to the region to repress or activate transcription by opening up the chromatin , which is a complex of DNA and histone proteins. It is the action of these regulatory proteins (transcription factors ) that determines, in large part, when a gene is turned on or off. Some genes are also turned on and off by methylation of cytosine bases that are adjacent to guanine bases (cytosine-phosphate-guanine bases, CpGs ). Methylation is an example of an epigenetic change, meaning a change that can affect gene expression, and possibly the characteristics of a cell or organism, but that does not involve a change in the underlying genetic sequence. Gene regulation is flexible and responsive, with genes being turned on or off during development and in response to internal and external environmental conditions and stimuli.

Transcription proceeds through the entire length of the gene in a 5′ to 3′ direction to form an mRNA transcript whose sequence is complementary to that of one of the DNA strands. RNA, like DNA, is a sugar-phosphate chain with pyrimidines and purines. In RNA the sugar is ribose, and uracil replaces the thymine found in DNA. A “cap” consisting of 7-methylguanosine is added to the 5′ end of the RNA in a 5′-5′ bond and, for most transcripts, several hundred adenine bases are enzymatically added to the 3′ end after transcription.

mRNA processing occurs in the nucleus and consists of excision of the introns and splicing together of the exons. Specific sequences at the start and end of introns mark the sites where the splicing machinery will act on the transcript. In some cases, there may be tissue-specific patterns to splicing, so that the same primary transcript can produce multiple distinct proteins.

The processed transcript is next exported to the cytoplasm, where it binds to ribosomes, which are complexes of protein and ribosomal RNA (rRNA ). The genetic code is then read in triplets of bases, each triplet corresponding with a specific amino acid or providing a signal that terminates translation . The triplet codons are recognized by transfer RNAs (tRNAs ) that include complementary anticodons and bind the corresponding amino acid, delivering it to the growing peptide. New amino acids are enzymatically attached to the peptide. Each time an amino acid is added, the ribosome moves 1 triplet codon step along the mRNA. Eventually a stop codon is reached, at which point translation ends and the peptide is released. In some proteins, there are posttranslational modifications , such as attachment of sugars (glycosylation ); the protein is then delivered to its destination within or outside the cell by trafficking mechanisms that recognize portions of the peptide.

Another mechanism of genetic regulation is noncoding RNAs, which are RNAs transcribed from DNA but not translated into proteins. Noncoding RNAs function in mediating splicing, the processing of coding RNAs in the nucleus, and the translation of coding mRNAs in ribosomes. The roles of large noncoding RNAs (>200 bp) and short noncoding RNAs (<200 bp) extend beyond these processes to impact a diverse set of biologic functions, including the regulation of gene expression. For example, micro RNAs (miRNAs ) are a class of small RNAs that control gene expression in the cell by directly targeting specific sets of coding RNAs by direct RNA–RNA binding. This RNA–RNA interaction can lead to degradation of the target-coding RNA or inhibition of translation of the protein specified by that coding RNA. miRNAs, in general, target and regulate several hundred mRNAs.

Genetic Variation

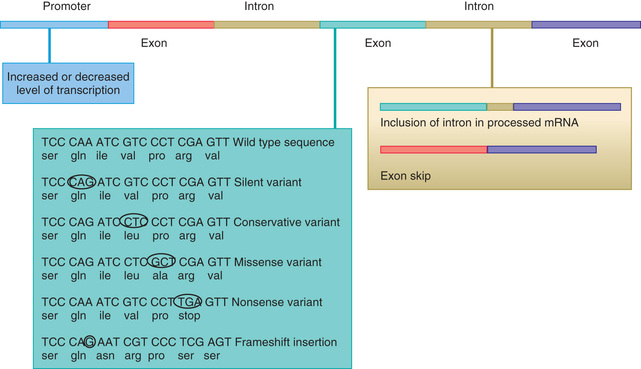

The process of producing protein from a gene is subject to disruption at multiple levels because of alterations in the coding sequence (Fig. 96.3 ). Changes in the regulatory region can lead to altered gene expression, including increased or decreased rates of transcription, failure of gene activation, or activation of the gene at inappropriate times or in inappropriate cells. Changes in the coding sequence can lead to substitution of one amino acid for another (missense variant or nonsynonymous variant ) or creation of a stop codon in the place of an amino acid codon. Overall, missense or nonsense variants are the most common (56% of variants); small deletions or insertions represent approximately 24% of variants (Table 96.1 ). Some single-base changes do not affect the amino acid (silent , wobble , or synonymous variants ), because there may be several triplet codons that correspond to a single amino acid. Amino acid substitutions can have a profound effect on protein function if the chemical properties of the substituted amino acid are markedly different from the usual one. Other substitutions can have a subtle or no effect on protein function, particularly if the substituted amino acid is chemically similar to the original one.

Table 96.1

Main Classes, Groups, and Types of Sequence Variants and Their Effects on Protein Products

| CLASS | GROUP | TYPE | EFFECT ON PROTEIN PRODUCT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution | Synonymous | Silent* | Same amino acid |

| Nonsynonymous | Missense* | Altered amino acid—may affect protein function or stability | |

| Nonsense* | Stop codon—loss of function or expression from degradation of mRNA | ||

| Splice site | Aberrant splicing—exon skipping or intron retention | ||

| Promoter | Altered gene expression | ||

| Deletion | Multiple of 3 (codon) | In-frame deletion of 1 or more amino acid(s)—may affect protein function or stability | |

| Not multiple of 3 | Frameshift | Likely to result in premature termination with loss of function or expression | |

| Large deletion | Partial gene deletion | May result in premature termination with loss of function or expression | |

| Whole gene deletion | Loss of expression | ||

| Insertion | Multiple of 3 (codon) | In-frame insertion of 1 or more amino acid(s)—may affect protein function or stability | |

| Not multiple of 3 | Frameshift | Likely to result in premature termination with loss of function or expression | |

| Large insertion | Partial gene duplication | May result in premature termination with loss of function or expression | |

| Whole gene duplication | May have an effect because of increased gene dosage | ||

| Expansion of trinucleotide repeat | Dynamic mutation | Altered gene expression or altered protein stability or function |

* Some have been shown to cause aberrant splicing.

From Turnpenny P, Ellard S (Editors): Emery's elements of medical genetics, ed 14, Philadelphia, 2012, Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, p 23.

Genetic changes can also include insertions or deletions . Insertions or deletions of a nonintegral multiple of 3 bases into the coding sequence leads to a frameshift, altering the grouping of bases into triplets. This leads to translation of an incorrect amino acid sequence and often a premature stop to translation. Insertion or deletion of an integral multiple of 3 bases into the coding sequence will insert or delete a corresponding number of amino acids from the protein, leading to in-frame alterations that maintain the amino acid sequence outside the deleted or duplicated amino acids. Larger-scale insertions or deletions can disrupt a coding sequence or result in complete deletion of an entire gene or group of genes.

Pathogenic variants usually can be classified as causing a loss of function or a gain of function. Loss-of-function variants cause a reduction in the level of protein function as a result of decreased expression or production of a protein that does not work as efficiently. In some cases, loss of protein function from 1 gene is sufficient to cause disease. Haploinsufficiency describes the situation in which maintenance of a normal phenotype requires the proteins produced by both copies of a gene, and a 50% decrease in gene function results in an abnormal phenotype. Thus, haploinsufficient phenotypes are, by definition, dominantly inherited. Loss-of-function variants can also have a dominant negative effect when the abnormal protein product actively interferes with the function of the normal protein product. Both these situations lead to diseases inherited in a dominant fashion. In other cases, loss-of-function variants must be present in both copies of a gene before an abnormal phenotype results. This situation typically results in diseases inherited in a recessive fashion (see Chapter 97 ).

Gain-of-function variants typically cause dominantly inherited diseases. These variants can result in production of a protein molecule with an increased ability to perform a normal function or can confer a novel property on the protein. The gain-of-function variant in achondroplasia , the most common of the disproportionate, short-limbed short stature disorders, exemplifies the enhanced function of a normal protein. Achondroplasia results from a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 3 gene (FGFR3 ), which leads to activation of the receptor, even in the absence of FGF. In sickle cell disease an amino acid is substituted into the hemoglobin molecule and has little effect on the ability of the protein to transport oxygen. However, sickle hemoglobin chains have a novel property. Unlike normal hemoglobin, sickle hemoglobin chains aggregate under conditions of deoxygenation, forming fibers that deform the red cells.

Other gain-of-function mutations result in overexpression or inappropriate expression of a gene product. Many cancer-causing genes (oncogenes ) are normal regulators of cellular proliferation during development. However, expression of these genes in adult life and/or in cells in which they usually are not expressed can result in neoplasia.

In some cases, changes in gene expression are caused by changes in the number of copies of a gene that are present in the genome (Fig. 96.4 ). Although some copy number variations are common and do not appear to cause or predispose to disease, others are clearly disease causing. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A , the most common inherited form of chronic peripheral neuropathy of childhood, is caused by duplications of the gene for peripheral myelin protein 22, resulting in overexpression as a result of the existence of 3 active copies of this gene (see Chapter 631.1 ). Deletions of this same gene leaving only 1 active copy are responsible for a different disorder, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies.

Deletions and duplications can vary in their extent and can involve several genes, even when they are not visible on a traditional chromosome analysis. Such changes are commonly called microdeletions and microduplications . When deletion or duplication of 2 or more genes in the same chromosomal region each play a role in the resulting clinical features, the condition can also be referred to as a contiguous gene disorder .

In some cases the recognition of a specific constellation of features leads the clinician to suspect a specific microdeletion or microduplication syndrome. Examples of such disorders include Smith-Magenis, DiGeorge, and Williams syndromes. In other cases the clinician may be alerted to this possibility by an unusually diverse array of clinical features in one patient or the presence of unusual features in a person with a known condition. Because of the close physical proximity of a series of genes, different deletions involving the short arm of the X chromosome can produce individuals with various combinations of ichthyosis, Kallmann syndrome, ocular albinism, intellectual disability, chondrodysplasia punctata, and short stature.

DNA rearrangements can also take place in somatic cells (cells that do not go on to produce ova or sperm). Rearrangements that occur in lymphoid cells are required for the formation of functional immunoglobulin in B cells and antigen-recognizing receptors on T cells. Large segments of DNA, which code for the variable and the constant regions of either immunoglobulin or the T-cell receptor (TCR), are physically joined at a specific stage in the development of an immunocompetent lymphocyte. These rearrangements take place during development of the lymphoid cell lineage in humans and result in the extensive diversity of immunoglobulin and TCR molecules. Because of this postgermline DNA rearrangement, no 2 individuals, not even identical twins, are really identical, because mature lymphocytes from each will have undergone random DNA rearrangements at these loci.

Studies of the human genome sequence reveal that any 2 individuals differ in about 1 base in 1,000. Some of these differences are silent; some result in changes that explain phenotypic differences (hair or eye color, physical appearance); some have medical significance, causing single-gene disorders such as sickle cell anemia or explaining susceptibility to common pediatric disorders such as asthma. Genetic variants in a single gene that occur at a frequency of >1% in a population are often referred to as polymorphisms . These variations may be silent or subtle or may have significant phenotypic effects.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Genetic Disease

The term genotype is used to signify the internally coded, heritable information of an individual and can also be used to refer to which particular alternative version (allele ) of a gene is present at a specific location (locus ) on a chromosome. A phenotype is the observed structural, biochemical, and physiologic characteristics of an individual, determined by the genotype, and can also refer to the observed structural and functional effects of a variant allele at a specific locus. Many sequence variants result in predictable phenotypes. In these cases, physicians can predict clinical outcomes and plan appropriate treatment strategies based on a patient's genotype. Increasingly, there is phenotypic expansion where multiple alleles (variants) within a gene can be associated with often diverse and distinct clinical presentations.

The long QT syndrome exemplifies a disorder with predictable associations between a patient's genotype and his or her phenotype (see Chapter 462.5 ). Long QT syndrome is genetically heterogeneous, meaning that pathogenic variants in several different genes can cause the same disorder. The risk for cardiac events (syncope, aborted cardiac arrest, or sudden death) is higher in patients with long QT syndrome involving the KCNQ1 gene (63%) or KCNH2 (46%) than in those with pathogenic variants in SCN5A (18%). In addition, those with KCNQ1 variants experience most of their episodes during exercise and rarely during rest or sleep. In contrast, individuals with pathogenic variants in KCNH2 and SCN5A are more likely to have episodes during sleep or rest and rarely during exercise. Therefore, variants in specific genes (genotype) are correlated with specific manifestations (phenotype) of long QT syndrome. These types of relationships are commonly referred to as genotype-phenotype correlations.

Pathogenic variants in the fibrillin-1 gene associated with Marfan syndrome represent another example of predictable genotype-phenotype correlations (see Chapter 722 ). Marfan syndrome is characterized by the combination of skeletal, ocular, and aortic manifestations, with the most devastating outcome being aortic root dissection and sudden death. The fibrillin-1 gene consists of 65 exons, and mutations have been found in almost all these. The location of the mutation within the gene (genotype) might play a significant role in determining the severity of the condition (phenotype). Neonatal Marfan syndrome is caused by mutations in exons 24-27 and in exons 31 and 32, whereas milder forms are caused by mutations in exons 59-65 and in exons 37 and 41.

Genotype-phenotype correlations have also been observed in some complications of cystic fibrosis (CF; see Chapter 432 ). Although pulmonary disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality, CF is a multisystem disorder that affects not only the epithelia of the respiratory tract but also the exocrine pancreas, intestine, male genital tract, hepatobiliary system, and exocrine sweat glands. CF is caused by pathologic variants in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR ) gene; >1,600 different pathogenic variants have been identified. The most common is a deletion of 3 nucleotides that removes the amino acid phenylalanine (F) at the 508th position on the protein (ΔF508 variant), which accounts for approximately 70% of all pathogenic CF variants and is associated with severe disease. The best genotype-phenotype correlations in CF are seen in the context of pancreatic function, with most common mutations being classified as either pancreatic sufficient or pancreatic insufficient. Persons with pancreatic sufficiency usually have either 1 or 2 pancreatic-sufficient alleles, indicating that pancreatic-sufficient alleles are dominant. In contrast, the genotype-phenotype correlation in pulmonary disease is much weaker, and persons with identical genotypes have wide variations in the severity of their pulmonary disease. This finding may be accounted for in part by genetic modifiers or environmental factors.

In many disorders the effects of variants on phenotype can be modified by changes in the other allele of the same gene, by changes in specific modifier genes , and/or by variations in a number of unspecified genes (genetic background ). When sickle cell anemia is co-inherited with the gene for hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin, the sickle cell phenotypic expression is less severe. Modifier genes in CF can influence the development of congenital meconium ileus, or colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Modifier genes can also affect the manifestations of Hirschsprung disease, neurofibromatosis type 2, craniosynostosis, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The combination of genetic variants producing glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and longer versions of the TATAA element in the uridine diphosphate–glucuronosyltransferase gene promoter exacerbates neonatal physiologic hyperbilirubinemia.

Human Genome Project

A rudimentary genetic map can be made using genetic linkage, which is based on the principle that alleles at 2 genetic loci that are located near each other segregate together in a family unless they are separated by genetic recombination . The frequency of recombination between the loci can be used to estimate the physical distance between points. Some of the first maps of the human genome were linkage maps based on a set of polymorphic genetic loci located along the entire human genome. Linkage analysis is still used to map the location of genetic changes responsible for phenotypic traits and genetic disorders that are inherited in a mendelian fashion.

In contrast to linkage maps, which are based on recombination frequencies, physical maps rely on overlapping DNA fragments to determine the location of loci with respect to one another. Several strategies can be used to create physical maps of a chromosomal region. In one strategy, segments of the region of interest with lengths from hundreds or thousands to a few million base pairs are isolated and placed in microorganisms such as bacteria or yeast. Common regions contained in different organisms can then be identified and this information used to piece together a map composed of overlapping DNA pieces, each contained in a different microorganism. The pieces contained in each organism can then be sequenced to obtain the DNA sequence of the entire region. An alternative strategy involves breaking the entire genome into random fragments, sequencing the fragments, and then using a computer to order the fragments based on overlapping segments. This whole genome approach in combination with new next-generation sequencing technologies has resulted in a dramatic reduction in the cost of sequencing an individual's entire genome.

Analysis of the human genome has produced some surprising results. The number of genes appears to be about 20,000. This is fewer than had been expected and is in the same range as many simpler organisms. The number of protein products encoded by the genome is greater than the number of genes. This is a result of the presence of alternative promoter regions, alternative splicing, and posttranslational modifications, which can allow a single gene to encode a number of protein products.

It is also apparent that most of the human genome does not encode protein, with <5% being transcribed and translated, although a much larger percentage may be transcribed without translation. Many transcribed sequences are not translated but represent genes that encode RNAs that serve a regulatory role. A large fraction of the genome consists of repeated sequences that are interspersed among the genes. Some of these are transposable genetic elements that can move from place to place in the genome. Others are static elements that were expanded and dispersed in the past during human evolution. Other repeated sequences might play a structural role. There are also regions of genomic duplications. Such duplications are substrate for evolution, allowing genetic motifs to be copied and modified to serve new roles in the cell. Duplications can also play a role in chromosomal rearrangement, permitting nonhomologous chromosome segments to pair during meiosis and exchange material. This is another source of evolutionary change and a potential source of chromosomal instability leading to congenital anomalies or cancer. Low copy repeats also play an important role in causing genomic disorders. When low copy repeats flank unique genomic segments, these regions can be duplicated or deleted through a process known as nonallelic homologous recombination.

Availability of the entire human genomic sequence permits the study of large groups of genes, looking for patterns of gene expression or genome alteration. Microarrays permit the expression of thousands of genes to be analyzed on a small glass chip. Increasingly, studies of gene expression are being performed using next generation sequencing techniques to obtain information about all of the RNA transcripts in a tissue sample. In some cases the patterns of gene expression provide signatures for particular disease states, such as cancer, or change in response to therapy (Fig. 96.5 ).