Disturbances of Rate and Rhythm of the Heart

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

The term arrhythmia refers to a disturbance in heart rate or rhythm. Such disturbances can lead to heart rates that are abnormally fast, slow, or irregular. They may be transient or incessant, congenital or acquired, or caused by a toxin or by drugs. They may be associated with particular forms of congenital heart disease (CHD), may be a complication of surgical repair of CHD, may be a result of certain genetic causes, or may be caused by fetal inflammation, as in maternal connective tissue disease. Arrhythmias, either slow or fast, may lead to acutely decreased cardiac output, degeneration into a more dangerous arrhythmia such as ventricular fibrillation, or if incessant may lead to cardiomyopathy. Arrhythmias may lead to syncope or to sudden death. When a patient has an arrhythmia, it is important to determine whether the particular rhythm is likely to lead to severe symptoms or to deteriorate into a life-threatening condition. Rhythm abnormalities such as single premature atrial and ventricular beats are common, and in children without heart disease, these usually pose no risk to the patient.

A number of pharmacologic agents are available for treating arrhythmias; many have not been studied extensively in children. Insufficient data are available regarding pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy in the pediatric population, and therefore the selection of an appropriate agent is necessarily empirical. Fortunately, most rhythm disturbances in children can be reliably controlled with a single agent (Table 462.1 ). Transcatheter ablation is acceptable therapy not only for life-threatening or drug-resistant arrhythmias, but also for the cure of arrhythmias. For patients with bradycardia, implantable pacemakers are small enough for use in all ages, and even in premature infants. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators are available for use in high-risk patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias and an increased risk of sudden death.

Table 462.1

Antiarrhythmic Drugs Commonly Used in Pediatric Patients, by Class

| DRUG | INDICATIONS | DOSING | SIDE EFFECTS | DRUG INTERACTIONS | DRUG LEVEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLASS IA: INHIBITS Na+ FAST CHANNEL, PROLONGS REPOLARIZATION | |||||

| Quinidine | SVT, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, VT. In atrial flutter, an AV node–blocking drug (digoxin, verapamil, propranolol) must be given first to prevent 1 : 1 conduction |

Oral: 30-60 mg/kg/24 hr divided q6h (sulfate) or q8h (gluconate) In adults, 10 mg/kg/day divided q6h Max dose: 2.4 g/24 hr |

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, cinchonism, QRS and QT prolongation, AV nodal block, asystole syncope, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, SLE, blurred vision, convulsions, allergic reactions, exacerbation of periodic paralysis | Enhances digoxin, may increase PTT when given with warfarin | 2-6 µg/mL |

| Procainamide | SVT, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, VT |

Oral: 15-50 mg/kg/24 hr divided q4h Max dose: 4 g/24 hr IV: 10-15 mg/kg over 30-45 min load followed by 20-80 µg/kg/min Max dose: 2 g/24 hr |

PR, QRS, QT interval prolongation, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, rash, fever, agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia, SLE, hypotension, exacerbation of periodic paralysis, proarrhythmia | Toxicity increased by amiodarone and cimetidine |

4-8 µg/mL With NAPA <40 µg/mL |

| Disopyramide | SVT, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter |

Oral: <2 yr: 20-30 mg/kg/24 hr divided q6h or q12h (long-acting form); 2-10 yr: 9-24 mg/kg/24 hr divide q6h or q12h (long-acting form); 11 yr: 5-13 mg/kg/24 hr divided q6h or q12h (long-acting) Max dose: 1.2 g/24 hr |

Anticholinergic effects, urinary retention, blurred vision, dry mouth, QT and QRS prolongation, hepatic toxicity, negative inotropic effects, agranulocytosis, psychosis, hypoglycemia, proarrhythmia | 2-5 µg/ml | |

| CLASS IB: INHIBITS Na+ FAST CHANNEL, SHORTENS REPOLARIZATION | |||||

| Lidocaine | VT, VF | IV: 1 mg/kg repeat q 5 min 2 times followed by 20-50 µg/kg/min (max dose: 3 mg/kg) | CNS effects, confusion, convulsions, high-grade AV block, asystole, coma, paresthesias, respiratory failure | Propranolol, cimetidine, increases toxicity | 1-5 µg/mL |

| Mexiletine | VT | Oral: 6-15 mg/kg/24 hr divided q8h | GI upset, skin rash, neurologic | Cimetidine | 0.8-2 µg/mL |

| Phenytoin | Digitalis intoxication |

Oral: 3-6 mg/kg/24 hr divided q12h Max dose: 600 mg IV: 10-15 mg/kg over 1 hr load |

Rash, gingival hyperplasia, ataxia, lethargy, vertigo, tremor, macrocytic anemia, bradycardia with rapid push | Amiodarone, oral anticoagulants, cimetidine, nifedipine, disopyramide, increase toxicity | 10-20 µg/mL |

| CLASS IC: INHIBITS Na+ CHANNEL | |||||

| Flecainide | SVT, atrial tachycardia, VT |

Oral: 6.7-9.5 mg/kg/24 hr divided q8h In older children, 50-200 mg/m2 /day divided q12h |

Blurred vision, nausea, decrease in contractility, proarrhythmia | Amiodarone increases toxicity | 0.2-1 µg/mL |

| Propafenone | SVT, atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, VT | Oral: 150-300 mg/m2 /24 hr divided q6h | Hypotension, decreased contractility, hepatic toxicity, paresthesia, headache, proarrhythmia | Increases digoxin levels | 0.2-1 µg/mL |

| CLASS II: β-BLOCKERS | |||||

| Propranolol | SVT, long QT |

Oral: 1-4 mg/kg/24 hr divided q6h Max dose 60 mg/24 hr IV: 0.1-0.15 mg/kg over 5 min Max IV dose: 10 mg |

Bradycardia, loss of concentration, school performance problems bronchospasm, hypoglycemia, hypotension, heart block, CHF | Co-administration with disopyramide, flecainide, or verapamil may decrease ventricular function. | |

| Atenolol | SVT | Oral: 0.5-1 mg/kg/24 hr once daily or divided q12h | Bradycardia, loss of concentration, school performance problems | Co-administration with disopyramide, flecainide, or verapamil may decrease ventricular function. | |

| Nadolol | SVT, long QT | Oral: 1-2 mg/kg/24 hr given once daily | Bradycardia, loss of concentration, school performance problems bronchospasm, hypoglycemia, hypotension, heart block, CHF | Co-administration with disopyramide, flecainide, or verapamil may decrease ventricular function. | |

| CLASS III: PROLONGS REPOLARIZATION | |||||

| Amiodarone | SVT, JET, VT |

Oral: 10 mg/kg/24 hr in 1-2 divided doses for 4-14 days; reduce to 5 mg/kg/24 hr for several weeks; if no recurrence, reduce to 2.5 mg/kg/24 hr IV: 2.5-5 mg/kg over 30-60 min, may repeat 3 times, then 2-10 mg/kg/24 hr continuous infusion |

Hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, elevated triglycerides, hepatic toxicity, pulmonary fibrosis | Digoxin (increases levels), flecainide, procainamide, quinidine, warfarin, phenytoin | 0.5-2.5 mg/L |

| CLASS IV AND MISCELLANEOUS MEDICATIONS | |||||

| Digoxin | SVT (not WPW), atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation |

Oral/load instructions: Premature: 20 µg/kg Newborn: 30 µg/kg >6 mo: 40 µg/kg |

PAC, PVC, bradycardia, AV block, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, prolongs PR interval |

Quinidine Amiodarone, verapamil, increase digoxin levels |

1-2 mg/mL |

Give  total dose followed by

total dose followed by  q8-12h × 2 doses

q8-12h × 2 doses |

|||||

|

Maintenance: 10 µg/kg/24 hr divide q12h Max dose: 0.5 mg |

|||||

|

IV: Max dose: 0.5 mg |

|||||

| Verapamil | SVT (not WPW) |

Oral: 2-7 mg/kg/24 hr divided q8h Max dose: 480 mg IV: 0.1-0.2 mg/kg q 20 min × 2 doses Max dose: 5-10 mg |

Bradycardia, asystole, high degree AV block, PR prolongation, hypotension, CHF | Use with β-blocker or disopyramide exacerbates CHF, increases digoxin level and toxicity | |

| Adenosine | SVT |

IV: 50-300 µg/kg by need rapid IV push Begin with 50 µg/kg and increase by 50-100 µg/kg/dose Max dose: 18 mg |

Chest pain, flushing, dyspnea, bronchospasm, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, asystole | ||

AV, Atrioventricular; CHF, congestive heart failure; CNS, central nervous systems; GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; JET, junctional ectopic tachycardia; NAPA, N -acetyl procainamide; PAC, premature atrial contraction; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus–like illness; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Principles of Antiarrhythmic Therapy

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

When considering drug therapy in the pediatric population, it is important to recognize that there may be marked differences in pharmacokinetics by age and comparison with adults. Infants may have slower absorption, slow gastric emptying, and differing sizes of drug tissue compartments affecting the volume of distribution. Hepatic metabolism and renal excretion may vary within the pediatric age-group as well as in comparison to adults. Special consideration must also be given to the frequency and diet of an infant when choosing specific antiarrhythmics. When considering antiarrhythmic therapy, it is important to recognize that the likely arrhythmia mechanism may be different for the pediatric than the adult population.

Many antiarrhythmic agents are available for rhythm control. The majority are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in children; their use is therefore considered “off-label.” Pediatric cardiologists have experience with these drugs, with well-recognized standards for dosing.

With the availability of potentially curative ablation procedures, medical therapy has become less important. Clinicians and patients accept fewer drug side effects. Intolerable side effects, as well as the potential for a proarrhythmia induced by an antiarrhythmic drug, can seriously limit medical therapy and will lead the physician and family toward a potentially curative ablation procedure.

Antiarrhythmic drugs are frequently categorized using the Vaughan-Williams classification . This system comprises 4 classes: class I includes agents that primarily block the sodium channel, class II drugs are the β-blockers, class III includes agents that prolong repolarization by blocking potassium channels, and class IV drugs are the calcium channel blockers. Class I is further divided by the strength of the sodium channel blockade (see Table 462.1 ).

Sinus Arrhythmias and Extrasystoles

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

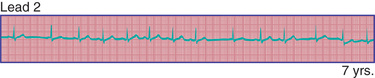

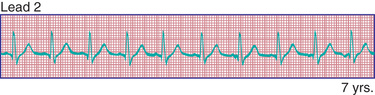

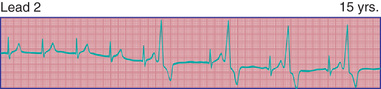

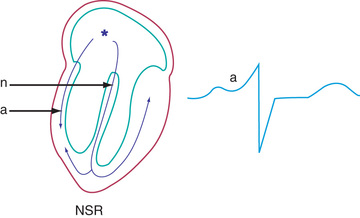

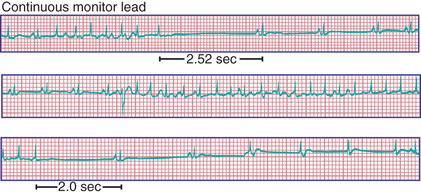

Phasic sinus arrhythmia represents a normal physiologic variation in impulse discharges from the sinus node related to respirations. The heart rate slows during expiration and accelerates during inspiration. Occasionally, if the sinus rate becomes slow enough, an escape beat arises from the atrioventricular (AV) junction region (Fig. 462.1 ). Normal phasic sinus arrhythmia is caused by the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system and can be quite prominent in healthy children. It may mimic frequent premature contractions, but the relationship to the phases of respiration can be appreciated with careful auscultation. Drugs that increase vagal tone, such as digoxin, may exaggerate sinus arrhythmia; it is usually abolished by exercise. Other irregularities in sinus rhythm, especially bradycardia associated with periodic apnea, are common in premature infants.

Sinus bradycardia is a result of slow discharge of impulses from the sinus node, the heart's “natural pacemaker.” A sinus rate <90 beats/min in neonates and <60 beats/min in older children is considered sinus bradycardia. It is typically seen in well-trained athletes; in healthy individuals it generally has no significance. Sinus bradycardia may occur in systemic disease (hypothyroidism, anorexia nervosa), and it resolves when the disorder is under control. It may also be seen in association with conditions in which there is high vagal tone, such as gastrointestinal obstruction or intracranial processes. Low-birthweight infants display great variation in sinus rate. Sinus bradycardia is common in these infants, in conjunction with apnea, and may be associated with junctional escape beats; premature atrial contractions are also frequent. These rhythm changes, especially bradycardia, appear more often during sleep and are not associated with symptoms. Usually, no therapy is necessary.

Wandering atrial pacemaker is defined as an intermittent shift in the pacemaker of the heart from the sinus node to another part of the atrium (Fig. 462.2 ). It is not uncommon in childhood and usually represents a normal variant. It may also be seen in association with sinus bradycardia in which the shift in atrial focus is an escape phenomenon.

Extrasystoles are produced by the premature discharge of an ectopic focus that may be situated in the atrium, the AV junction, or the ventricle. Usually, isolated extrasystoles are of no clinical or prognostic significance. Under certain circumstances, however, premature beats may be caused by organic heart disease (inflammation, ischemia, fibrosis) or drug toxicity.

Premature atrial contractions or complexes (PACs) are common in childhood, usually in the absence of cardiac disease. Depending on the degree of prematurity of the beat (coupling interval) and the preceding R-R interval (cycle length), PACs may result in a normal, a prolonged (aberrancy), or an absent (blocked PAC) QRS complex. The last occurs when the premature impulse cannot conduct to the ventricle due to refractoriness of the AV node or distal conducting system (Fig. 462.3 ). Atrial extrasystoles must be distinguished from premature ventricular contractions. Careful scrutiny of the electrocardiogram (ECG) for a premature P wave preceding the QRS will show either a premature P wave superimposed on and deforming the preceding T wave or a P wave that is premature and has a different contour from that of the other sinus P waves. PACs usually reset the sinus node pacemaker, leading to an incomplete compensatory pause, but this feature is not regarded as a reliable means of differentiating atrial from ventricular premature complexes in children.

Premature ventricular contractions or complexes (PVCs) may arise in any region of the ventricles. PVCs are characterized by premature, widened, bizarre QRS complexes that are not preceded by a premature P wave (Fig. 462.4 ). When all premature beats have identical contours, they are classified as uniform, suggesting origin from a common site. When PVCs vary in contour, they are designated as multiform, suggesting origin from more than 1 ventricular site. Ventricular extrasystoles are often, but not always, followed by a full compensatory pause. The presence of fusion beats , that is, complexes with morphologic features that are intermediate between those of normal sinus beats and those of PVCs, proves the ventricular origin of the premature beat. Extrasystoles produce a smaller stroke and pulse volume than normal and, if quite premature, may not be audible with a stethoscope or palpable at the radial pulse. When frequent, extrasystoles may assume a definite rhythm, for example, alternating with normal beats (bigeminy ) or occurring after 2 normal beats (trigeminy ). Most patients are unaware of single PVCs, although some may be aware of a “skipped beat” over the precordium. This sensation is caused by the increased stroke volume of the normal beat after a compensatory pause. Anxiety, a febrile illness, or ingestion of various drugs or stimulants may exacerbate PVCs.

It is important to distinguish PVCs that are benign from those that are likely to lead to more severe arrhythmias. The former usually disappear during the tachycardia of exercise. If they persist or become more frequent during exercise, the arrhythmia may have greater significance. The following criteria are indications for further investigation of PVCs that could require suppressive therapy : (1) ≥2 PVCs in a row; (2) multiform PVCs; (3) increased ventricular ectopic activity with exercise; (4) R-on-T phenomenon (premature ventricular depolarization occurs on the T wave of the preceding beat); (5) extreme frequency of beats (e.g., >20% of total beats on Holter monitoring); and (6) most importantly, the presence of underlying heart disease, a history of heart surgery, or both. The best therapy for benign PVCs is reassurance that the arrhythmia is not life threatening, although very symptomatic individuals may benefit from suppressive therapy.

Malignant PVCs are usually secondary to another medical problem (electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, drug toxicity, cardiac injury). Successful treatment includes correction of the underlying abnormality. An intravenous lidocaine bolus and drip is the first line of therapy, with more effective drugs such as amiodarone reserved for refractory cases or for patients with underlying ventricular dysfunction or hemodynamic compromise.

Supraventricular Tachycardia

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT ) is a general term that includes essentially all forms of paroxysmal or incessant tachycardia except ventricular tachycardia. The category of SVT can be divided into 3 major subcategories: reentrant tachycardias using an accessory pathway, reentrant tachycardias without an accessory pathway, and ectopic or automatic tachycardias. Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia (AVRT) involves an accessory pathway and is the most common mechanism of SVT in infants. Atrioventricular node reentry tachycardia (AVNRT) is rare in infancy, but there is an increasing incidence of AVNRT in childhood and into adolescence. Atrial flutter is rarely seen in children with normal hearts (see later), whereas intraatrial reentry tachycardia (also known as atrial flutter) is common in patients following cardiac surgery. Atrial and junctional ectopic tachycardias are more often associated with abnormal hearts (cardiomyopathy) and the immediate postoperative period after surgery for CHD.

Clinical Manifestations

Reentrant SVT is characterized by an abrupt onset and termination; it may occur when the patient is at rest or exercising, and in infants it may be precipitated by an acute infection. Attacks may last only a few seconds or may persist for hours. The heart rate usually exceeds 180 beats/min and may occasionally be as rapid as 300 beats/min. The only complaint may be awareness of the rapid heart rate. Many children tolerate these episodes extremely well, and it is unlikely that short paroxysms are a danger to life. If heart rate is exceptionally rapid or the attack is prolonged, precordial discomfort and heart failure may occur. In children, SVT may be exacerbated by exposure to caffeine, nonprescription decongestants, or bronchodilators.

In young infants the diagnosis may be more obscure because of their inability to communicate their symptoms. The heart rate at this age is normally higher than in older children and increases greatly with crying. Occasionally, infants with SVT initially present with heart failure because the tachycardia may go unrecognized for a long time. The heart rate during episodes is frequently in the range of 240-300 beats/min. If the attack lasts 6-24 hr or more, heart failure may be recognized, and the infant will have an ashen color and will be restless and irritable, with tachypnea, poor pulses, and hepatomegaly. When tachycardia occurs in the fetus, it can cause hydrops fetalis , the in utero manifestation of heart failure.

In neonates, SVT is usually manifested as a narrow QRS complex (<0.08 sec). The P wave is visible on a standard ECG in only 50–60% of neonates with SVT, but it is detectable with a transesophageal lead in most patients. Differentiation from sinus tachycardia may be difficult but is important because sinus tachycardia requires treatment of the underlying problem (e.g., sepsis, hypovolemia) rather than antiarrhythmic medication. If the rate is >230 beats/min with an abnormal P-wave axis (a normal P wave is positive in leads I and aVF), sinus tachycardia is not likely. The heart rate in SVT also tends to be relatively unvarying , whereas in sinus tachycardia the heart rate varies with changes in vagal and sympathetic tone. AVRT uses a bypass tract that may be able to conduct bidirectionally (Wolff-Parkinson-White [WPW ] syndrome ) or may be retrograde only (concealed accessory pathway ). Patients with WPW syndrome have a small but real risk of sudden death. If the accessory pathway rapidly conducts in antegrade fashion, the patient is at risk for atrial fibrillation begetting ventricular fibrillation. Risk stratification, including 24 hr Holter monitoring and exercise study, may help differentiate patients at higher risk for sudden death from WPW. However, it is important to note that intermittent preexcitation may not decrease a patient's risk profile. Syncope is an ominous symptom in WPW, and any patient with syncope and WPW syndrome should have an electrophysiology study (EPS) and likely catheter ablation.

The typical electrocardiographic features of the WPW syndrome are seen when the patient is not having tachycardia. These features include a short P-R interval and slow upstroke of the QRS (delta wave) (Fig. 462.5 ). Although most often presenting in patients with a normal heart, WPW syndrome may also be associated with Ebstein anomaly of the tricuspid valve or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The critical anatomic structure is an accessory pathway consisting of a muscular bridge connecting atrium to ventricle on either the right or the left side of the AV ring (Fig. 462.6 ). During sinus rhythm, the impulse is carried over both the AV node and the accessory pathway; it produces some degree of fusion of the 2 depolarization fronts that results in an abnormal QRS. During AVRT, an impulse is carried in antegrade fashion through the AV node (orthodromic tachycardia ), which results in a normal QRS complex, and in retrograde fashion through the accessory pathway to the atrium, thereby perpetuating the tachycardia. In these cases, only after cessation of the tachycardia is the typical ECG features of WPW syndrome recognized (see Fig. 462.5 ). When rapid antegrade conduction occurs through the accessory pathway during tachycardia, and the retrograde reentry pathway to the atrium is by the AV node (antidromic tachycardia ), the QRS complexes are wide, and the potential for more serious arrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation) is greater, especially if atrial fibrillation occurs.

AVNRT involves the use of 2 functional pathways within the AV node, the slow and fast AV node pathways. This arrhythmia is more often seen in adolescence. It is one of the few forms of SVT that is occasionally associated with syncope. This arrhythmia is often seen in association with exercise.

Treatment

Vagal stimulation by placing of the face in ice water (in older children) or by placing an ice bag over the face (in infants) may abort the attack. To terminate the attack, older children may be taught vagal maneuvers such as the Valsalva maneuver, straining, breath holding, or standing on their head. Ocular pressure must never be performed, and carotid sinus massage is rarely effective. When these measures fail, several pharmacologic alternatives are available (see Table 462.1 ). In stable patients, adenosine by rapid intravenous push is the treatment of choice (0.1 mg/kg, maximum dose 6 mg) because of its rapid onset of action and minimal effects on cardiac contractility. The dose may need to be increased (0.2 mg/kg, maximum 12 mg) if no effect on the tachycardia is seen. Because of the potential for adenosine to initiate atrial fibrillation, it should never be administered without a means for direct current (DC ) cardioversion near at hand. Calcium channel blockers such as verapamil have also been used in the initial treatment of SVT in older children. Verapamil may reduce cardiac output and produce hypotension and cardiac arrest in infants younger than 1 yr and therefore is contraindicated in this age-group. In urgent situations when symptoms of severe heart failure have already occurred, synchronized DC cardioversion (0.5-2 J/kg) is recommended as the initial management (see Chapter 81 ).

Once the patient has been converted to sinus rhythm, a longer-acting agent is selected for maintenance therapy. In patients without an antegrade accessory pathway (non-WPW), the β-adrenergic blockers are the mainstay of drug therapy. Digoxin is also popular and may be effective in infants, but less so in older children. In children with WPW, digoxin or calcium channel blockers may increase the rate of antegrade conduction of impulses through the bypass tract, with the possibility of ventricular fibrillation, and are therefore contraindicated. These patients are usually managed with β-blockers. In patients with resistant tachycardias, flecainide, propafenone, sotalol, and amiodarone have all been used. Most antiarrhythmic agents have the potential of causing new dangerous arrhythmias (proarrhythmia ) and decreasing heart function. Flecainide and propafenone should be limited to use in patients with otherwise normal hearts.

If cardiac failure occurs because of prolonged tachycardia in an infant with a normal heart, cardiac function usually returns to normal after sinus rhythm is reinstituted, although it may take days to weeks. Infants with SVT diagnosed within the 1st 3-4 mo of life have a lower incidence of recurrence than those initially diagnosed at a later age. These patients have up to an 80% chance of resolution by the 1st yr of life, although approximately 30% will have recurrences later in childhood; if medical therapy is required, it can be tapered within 1 yr and the patient watched for signs of recurrence. Parents should be taught to measure the heart rate in their infants, so that prolonged unapparent episodes of SVT may be detected before heart failure occurs.

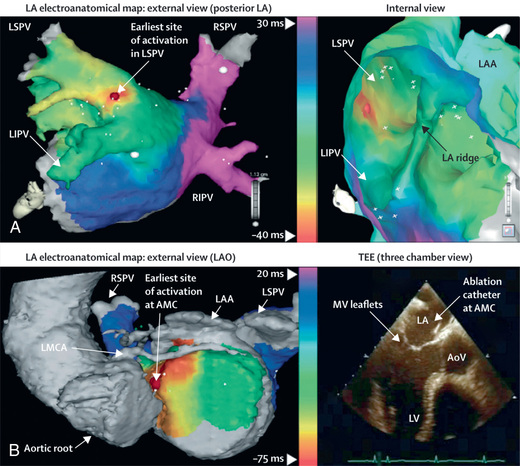

The use of 24 hr electrocardiographic (Holter) monitoring assists in following the course of therapy and detecting brief runs of asymptomatic tachycardia, particularly in younger children and infants. Some centers use transesophageal pacing to evaluate the effects of therapy in infants. More detailed electrophysiology studies performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory are often indicated in patients with refractory SVTs who are candidates for catheter ablation . During an EPS, multiple electrode catheters are placed transvenously in different locations in the heart. Pacing is performed to evaluate the conduction characteristics of the accessory pathway and to initiate the tachyarrhythmia, and mapping is performed to locate the accessory pathway. Catheter ablation of an accessory pathway is frequently used in children and teenagers, as well as in patients who require multiple agents or find drug side effects intolerable or for whom arrhythmia control is poor. Ablation may be performed either by radiofrequency ablation , which creates tissue heating, or cryoablation , in which tissue is frozen (Fig. 462.7 ). The overall initial success rate for catheter ablation ranges from 90–98%, depending on the location of the accessory pathway. Surgical ablation of bypass tracts is rarely done and proposed only in carefully selected patients.

The management of SVT caused by AVNRT is almost identical to that for AVRT. Children with AVNRT are not at increased risk of sudden death because they do not have a manifest accessory pathway. In practice, their episodes are more likely to be brought on by exercise or other forms of stress, and the heart rates can be quite fast, leading to chest pain, dizziness, and occasionally syncope. If chronic antiarrhythmic medication is desired, β-blockers are the drugs of choice; acutely, AVNRT responds to adenosine. Less is known about the natural history, but patients with AVNRT are seen quite frequently in adulthood, so spontaneous resolution seems unlikely. Patients are quite amenable to catheter ablation, either using radiofrequency energy or cryoablation, with high success rates and low complication rates.

Atrial ectopic tachycardia is an uncommon tachycardia in childhood. It is characterized by a variable rate (seldom >200 beats/min), identifiable P waves with an abnormal axis, and either a sustained or incessant nonsustained tachycardia. This form of atrial tachycardia has a single automatic focus. Identification of this mechanism is aided by monitoring the ECG while initiating vagal or pharmacologic therapy. Reentry tachycardias “break” suddenly, whereas automatic tachycardias gradually slow down and then gradually speed up again. Atrial ectopic tachycardias are usually more difficult to control pharmacologically than the more common reentrant tachycardias. If pharmacologic therapy with a single agent is unsuccessful, catheter ablation is suggested and has a success rate >90%.

Chaotic or multifocal atrial tachycardia is defined as atrial tachycardia with ≥3 ectopic P waves, frequent blocked P waves, and varying P-R intervals of conducted beats. This arrhythmia occurs most often in infants younger than 1 yr, usually without cardiac disease, although some evidence suggests an association with viral myocarditis or pulmonary disease. The goal of drug treatment is slowing of the ventricular rate, because conversion to sinus may not be possible, and multiple agents are often required. When this arrhythmia occurs in infancy, it usually terminates spontaneously by 3 yr of age.

Accelerated junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET) is an automatic (non-reentry) arrhythmia in which the junctional rate exceeds that of the sinus node and AV dissociation results. This arrhythmia is most often recognized in the early postoperative period after cardiac surgery and may be extremely difficult to control. Reduction of the infusion rate of catecholamines and control of fever and pain are important adjuncts to management. Congenital JET may be seen in the absence of surgery. It is incessant and can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Intravenous amiodarone is effective in the treatment of postoperative JET. Patients who require chronic therapy may respond to amiodarone or sotalol. Congenital JET can be cured by catheter ablation, but long-term AV block requiring a pacemaker is a prominent complication.

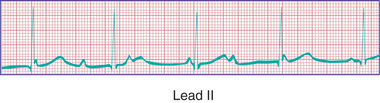

Atrial flutter , also known as intraatrial reentrant tachycardia, is an atrial tachycardia characterized by atrial activity at a rate of 250-300 beats/min in children and adolescents, and 400-600 beats/min in neonates. The mechanism of common atrial flutter consists of a reentrant rhythm originating in the right atrium circling the tricuspid valve annulus. Because the AV node cannot transmit such rapid impulses, some degree of AV block is virtually always present, and the ventricles respond to every 2nd to 4th atrial beat (Fig. 462.8 ). Occasionally, the response is variable, and the rhythm appears irregular.

In older children, atrial flutter usually occurs in the setting of CHD; neonates with atrial flutter frequently have normal hearts. Atrial flutter may occur during acute infectious illnesses but is most often seen in patients with large stretched atria, such as those associated with long-standing mitral or tricuspid insufficiency, tricuspid atresia, Ebstein anomaly, or rheumatic mitral stenosis. Atrial flutter can also occur after palliative or corrective intraatrial surgery. Uncontrolled atrial flutter may precipitate heart failure. Vagal maneuvers or adenosine may produce a temporary slowing of the heart rate as a result of increased AV block, allowing a diagnosis to be made. The diagnosis is confirmed by ECG, which demonstrates the rapid and regular atrial saw-toothed flutter waves. Atrial flutter usually converts immediately to sinus rhythm by synchronized DC cardioversion, which is most often the treatment of choice. Patients with chronic atrial flutter in the setting of CHD may be at increased risk for thromboembolism and stroke and should thus undergo anticoagulation before elective cardioversion. β-Blockers or calcium channel blockers may be used to slow the ventricular response in atrial flutter by prolonging the AV node refractory period. Other agents may be used to maintain sinus rhythm, including class I agents such as procainamide or propafenone or class III agents such as amiodarone and sotalol. Catheter ablation has been used in patients with normal hearts and those with CHD with moderate success. After cardioversion, neonates with normal hearts may be followed off antiarrhythmic therapy or may be treated with digoxin, propranolol, or sotalol for 6-12 mo, after which the medication can usually be discontinued, since neonatal atrial flutter generally does not recur.

Atrial fibrillation is uncommon in children and is rare in infants. The atrial excitation is chaotic and more rapid (400-700 beats/min) and produces an irregularly irregular ventricular response and pulse (Fig. 462.9 ). This rhythm disorder is often associated with atrial enlargement or disease. Atrial fibrillation may be seen in older children with rheumatic mitral valve stenosis. It is also seen rarely as a complication of atrial surgery, in patients with left atrial enlargement secondary to left AV valve insufficiency, and in patients with WPW syndrome. Thyrotoxicosis, pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, or cardiomyopathy may be suspected in a previously normal older child or adolescent with atrial fibrillation. Very rarely, atrial fibrillation may be familial. The best initial treatment is rate control , most effectively with calcium channel blockers, to limit the ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation. Digoxin is not given if WPW syndrome is present. Normal sinus rhythm may be restored with intravenous procainamide, ibutilide, or amiodarone; DC cardioversion is the first choice in hemodynamically unstable patients. Patients with chronic atrial fibrillation are at risk for thromboembolism and stroke and should undergo anticoagulation with warfarin. Patients being treated by elective cardioversion should also undergo anticoagulation.

Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is less common than SVT in pediatric patients. VT is defined as at least 3 PVCs at >120 beats/min (Fig. 462.10 ). It may be paroxysmal or incessant. VT may be associated with myocarditis, anomalous origin of a coronary artery, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, primary cardiac tumors, and dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It is seen with prolonged QT interval of either congenital or acquired (proarrhythmic drugs) causation, WPW syndrome, and drug use (cocaine, amphetamines). It may develop years after intraventricular surgery (especially tetralogy of Fallot and related defects) or occur without obvious organic heart disease. VT must be distinguished from SVT with aberrancy or rapid conduction over an accessory pathway (Table 462.2 ). The presence of clear capture and fusion beats confirms the diagnosis of VT. Although some children tolerate rapid ventricular rates for many hours, this arrhythmia should be promptly treated because hypotension and degeneration into ventricular fibrillation may result. For patients who are hemodynamically stable, intravenous amiodarone, lidocaine, or procainamide is the initial drug of choice. If treatment is to be successful, it is critical to search for and correct any underlying abnormalities, such as electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, or drug toxicity. Amiodarone is the treatment of choice during cardiac arrest (see Chapter 81 ). Hemodynamically unstable patients with VT should be immediately treated with DC cardioversion. Overdrive ventricular pacing, through temporary pacing wires or a permanent pacemaker, may also be effective, although it may cause the arrhythmia to deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation. In the neonatal period, VT may be associated with an anomalous left coronary artery (see Chapter 459.2 ) or a myocardial tumor.

Table 462.2

Diagnosis of Tachyarrhythmias: Electrocardiographic Findings

| HEART RATE (BEATS/MIN) | P WAVE | QRS DURATION | REGULARITY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinus tachycardia | <230 | Always present, normal axis | Normal | Rate varies with respiration |

| Atrial tachycardia | 180-320 |

Present Abnormal P wave morphology and axis |

Normal or prolonged (with aberration) | Usually regular but ventricular response may be variable because of Wenckebach conduction |

| Atrial fibrillation | 120-180 | Fibrillatory waves | Normal or prolonged (with aberration) | Irregularly irregular (no 2 R-R intervals alike) |

| Atrial flutter |

Atrial: 250-400 Ventricular response variable: 100-320 |

Saw-tooth flutter waves | Normal or prolonged (with aberration) | Regular ventricular response (e.g., 2 : 1, 3 : 1, 3 : 2, and so on) |

| Junctional tachycardia | 120-280 | Atrioventricular dissociation with no fusion, and normal QRS capture beats | Normal or prolonged (with aberration) | Regular (except with capture beats) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 120-300 | Atrioventricular dissociation with capture beats and fusion beats | Prolonged for age | Regular (except with capture beats) |

Unless a clearly reversible cause is identified, EPS is usually indicated for patients in whom VT has developed, and depending on the findings, catheter ablation and/or ICD implantation may be indicated.

A related arrhythmia, ventricular accelerated rhythm , is occasionally seen in infants. It is defined the same way as VT, but the rate is only slightly faster than the coexisting sinus rate (within 10%). It is generally benign and resolves spontaneously.

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) is a chaotic rhythm that results in death unless an effective ventricular beat is rapidly reestablished (see Fig. 462.10 ). Usually, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and DC defibrillation are necessary. If defibrillation is ineffective or VF recurs, amiodarone or lidocaine may be given intravenously, and defibrillation repeated (see Chapter 81 ). After recovery from VF, a search should be made for the underlying cause. EPS is indicated for patients who have survived VF unless a clearly reversible cause is identified. If WPW syndrome is noted, catheter ablation should be performed. For patients in whom no correctable abnormality can be found, an ICD is almost always indicated because of the high risk of sudden death.

Long QT Syndromes

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

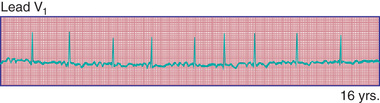

Long QT syndromes are genetic abnormalities of ventricular repolarization, with an estimated incidence of about 1 per 10,000 births (Table 462.3 ; also outlines other genetic arrhythmia syndromes). They present as a long QT interval on the surface ECG and are associated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias (torsades de pointes and VF). They are a cause of syncope and sudden death and may be the cause of some cases of sudden infant death syndrome, drowning, and intrauterine fetal demise (Fig. 462.11 ). In perhaps 80% of cases, there is an identifiable genetic mutation. The old distinction between dominant and recessive forms of the disease (Romano-Ward syndrome vs Jervell-Lange-Nielsen syndrome) is no longer made, because the latter recessive condition is known to result from the homozygous state. Jervell-Lange-Nielsen syndrome is associated with congenital sensorineural deafness. Asymptomatic but at-risk patients carrying the gene mutation may not all have a prolonged QT duration. QT interval prolongation may become apparent with exercise or during catecholamine infusions.

Table 462.3

Updated Summary of Heritable Arrhythmia Syndrome Susceptibility Genes

| GENE | LOCUS | PROTEIN |

|---|---|---|

| LONG QT SYNDROME (LQTS) | ||

| Major LQTS Genes | ||

| KCNQ1 (LQT1) | 11p15.5 | IKs potassium channel alpha subunit (KVLQT1, Kv 7.1) |

| KCNH2 (LQT2) | 7q35-36 | IKr potassium channel alpha subunit (HERG, Kv 11.1) |

| SCN5A (LQT3) | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| Minor LQTS Genes (Listed Alphabetically) | ||

| AKAP9 | 7q21-q22 | Yotiao |

| CACNA1C | 12p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| CALM1 | 14q32.11 | Calmodulin 1 |

| CALM2 | 2p21 | Calmodulin 2 |

| CALM3 | 19q13.2-q13.3 | Calmodulin 3 |

| CAV3 | 3p25 | Caveolin-3 |

| KCNE1 | 21q22.1 | Potassium channel beta subunit (MinK) |

| KCNE2 | 21q22.1 | Potassium channel beta subunit (MiRP1) |

| KCNJ5 | 11q24.3 | Kir3.4 subunit of IKACH channel |

| SCN4B | 11q23.3 | Sodium channel beta4 subunit |

| SNTA1 | 20q11.2 | Syntrophin-alpha1 |

| TRIADIN KNOCKOUT (TKO) SYNDROME | ||

| TRDN | 6q22.31 | Cardiac triadin |

| ANDERSEN-TAWIL SYNDROME (ATS) | ||

| KCNJ2 (ATS1) | 17q23 | IK1 potassium channel (Kir2.1) |

| TIMOTHY SYNDROME (TS) | ||

| CACNA1C | 12p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| Cardiac-Only TS (COTS) | ||

| CACNA1C | 12p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| SHORT QT SYNDROME (SQTS) | ||

| KCNH2 (SQT1) | 7q35-36 | IKr potassium channel alpha subunit (HERG, Kv 11.1) |

| KCNQ1 (SQT2) | 11p15.5 | IKs potassium channel alpha subunit (KVLQT1, Kv 7.1) |

| KCNJ2 (SQT3) | 17q23 | IK1 potassium channel (Kir2.1) |

| CACNA1C (SQT4) | 12p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| CACNB2 (SQT5) | 10p12 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel beta2 subunit |

| CACN2D1 (SQT6) | 7q21-q22 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel 2 delta1 subunit |

| CATECHOLAMINERGIC POLYMORPHIC VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA (CPVT) | ||

| RYR2 (CPVT1) | 1q42.1-q43 | Ryanodine receptor 2 |

| CASQ2 (CPVT2) | 1p13.3 | Calsequestrin 2 |

| KCNJ2 (CPVT3) | 17q23 | IK1 potassium channel (Kir2.1) |

| CALM1 | 14q32.11 | Calmodulin 1 |

| CALM3 | 19q13.2-q13.3 | Calmodulin 3 |

| TRDN | 6q22.31 | Cardiac triadin |

| BRUGADA SYNDROME (BrS) | ||

| SCN5A (BrS1) | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| Minor Brs Genes (Listed Alphabetically) | ||

| ABCC9 | 12p12.1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C member 9 |

| CACNA1C | 2p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| CACNA2D1 | 7q21-q22 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel 2 delta1 subunit |

| CACNB2 | 10p12 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel beta2 subunit |

| FGF12 | 3q28 | Fibroblast growth factor 12 |

| GPD1L | 3p22.3 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1–like |

| KCND3 | 1p13.2 | Voltage-gated potassium channel (Ito ) subunit Kv 4.3 |

| KCNE3 | 11q13.4 | Potassium channel beta3 subunit (MiRP2) |

| KCNJ8 | 12p12.1 | Inward rectifier K+ channel Kir6.1 |

| HEY2 | 6q | Hes-related family BHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 2 |

| PKP2 | 12p11 | Plakophilin-2 |

| RANGRF | 17p13.1 | RAN guanine nucleotide release factor 1 |

| SCN1B | 19q13 | Sodium channel beta1 |

| SCN2B | 11q23 | Sodium channel beta2 |

| SCN3B | 11q24.1 | Sodium channel beta3 |

| SCN10A | 3p22.2 | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha10 subunit (Nav 1.8) |

| SLMAP | 3p14.3 | Sarcolemma-associated protein |

| EARLY REPOLARIZATION SYNDROME (ERS) | ||

| ABCC9 | 12p12.1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C member 9 |

| CACNA1C | 2p13.3 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (Cav 1.2) |

| CACNA2D1 | 7q21-q22 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel 2 delta1 subunit |

| CACNB2 | 10p12 | Voltage-gated L-type calcium channel beta2 subunit |

| KCNJ8 | 12p12.1 | Inward rectifier K+ channel Kir6.1 |

| SCN5A | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| SCN10A | 3p22.2 | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha10 subunit (Nav 1.8) |

| IDIOPATHIC VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION (IVF) | ||

| ANK2 | 4q25-q27 | Ankyrin B |

| CALM1 | 14q32.11 | Calmodulin 1 |

| DPP6 | 7q36 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase-6 |

| KCNJ8 | 12p12.1 | Inward rectifier K+ channel Kir6.1 |

| RYR2 | 1q42.1-q43 | Ryanodine receptor 2 |

| SCN3B | 11q23 | Sodium channel beta3 subunit |

| SCN5A | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| PROGRESSIVE CARDIAC CONDUCTION DISEASE/DEFECT (PCCD) | ||

| SCN5A | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| TRPM4 | 19q13.33 | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 4 |

| SICK SINUS SYNDROME (SSS) | ||

| ANK2 | 4q25-q27 | Ankyrin B |

| HCN4 | 15q24-q25 | Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide–gated channel 4 |

| MYH6 | 14q11.2 | Myosin, heavy chain 6, cardiac muscle, alpha |

| SCN5A | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

| “ANKYRIN-B SYNDROME” | ||

| ANK2 | 4q25-q27 | Ankyrin B |

| FAMILIAL ATRIAL FIBRILLATION (FAF) | ||

| ANK2 | 4q25-q27 | Ankyrin B |

| GATA4 | 8p23.1-p22 | GATA-binding protein 4 |

| GATA5 | 20q13.33 | GATA-binding protein 5 |

| GJA5 | 1q21 | Connexin 40 |

| KCNA5 | 12p13 | IKur potassium channel (Kv 1.5) |

| KCNE2 | 21q22.1 | Potassium channel beta subunit (MiRP1) |

| KCNH2 | 7q35-36 | IKr potassium channel alpha subunit (HERG, Kv 11.1) |

| KCNJ2 | 17q23 | IK1 potassium channel (Kir2.1) |

| KCNQ1 | 11p15.5 | IKs potassium channel alpha subunit (KVLQT1, Kv 7.1) |

| NPPA | 1p36 | Atrial natriuretic peptide precursor A |

| NUP155 | 5p13 | Nucleoporin 155 kD |

| SCN5A | 3p21-p24 | Cardiac sodium channel alpha subunit (Nav 1.5) |

From Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ: Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias. In Braunwald's heart disease, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 33.1, p 605.)

Genetic studies have identified mutations in cardiac potassium and sodium channels (Table 462.3 ). Additional forms (up to 13 variants) of long QT syndrome (LQTS) have been described, but these are much more uncommon. Genotype may predict clinical manifestations; for example, LQTS type 1 (LQT1 ) events are usually induced by stress or exertion, whereas events in LQT3 often occur at rest, especially during sleep (Fig. 462.11 ). LQT2 events have an intermediate pattern, often occurring in the postpartum period or with auditory triggers. LQT3 has the highest probability for sudden death, followed by LQT2 and then LQT1. Drugs may prolong the QT interval directly but more often do so when drugs such as erythromycin or ketoconazole inhibit their metabolism (Table 462.4 ).

The clinical manifestation of LQTS in children is most often a syncopal episode brought on by exercise, fright, or a sudden startle; some events occur during sleep (LQT3). Patients can initially be seen with seizures, presyncope, or palpitations; approximately 10% are initially in cardiac arrest. The diagnosis is based on electrocardiographic and clinical criteria. Not all patients with long QT intervals have LQTS, and patients with normal QT intervals on a resting ECG may have LQTS. A heart rate–corrected QT interval of >0.47 sec is highly indicative, whereas a QT interval of >0.44 sec is suggestive. Other features include notched T waves in 3 leads, T-wave alternans, a low heart rate for age, a history of syncope (especially with stress), and a familial history of either LQTS or unexplained sudden death. Exercise testing and 24 hr Holter monitoring are adjuncts to the diagnosis. Genotyping is available and can identify the mutation is approximately 80% of patients known to have LQTS by clinical criteria. Genotyping is not useful in ruling out the diagnosis in individuals with suspected disease, but when positive is very useful in identifying asymptomatic affected relatives of the index case.

Short QT syndromes manifest with atrial or ventricular fibrillation and are associated with syncope and sudden death (see Table 462.3 ). They are often caused by a gain-of-function mutation in cardiac potassium channels.

Treatment of LQTS includes the use of β-blocking agents at doses that blunt the heart rate response to exercise. Propranolol and nadolol may be more effective than atenolol and metoprolol. Some patients require a pacemaker because of drug-induced bradycardia. An implantable cardiac-defibrillator (ICD) is indicated in patients with continued syncope despite treatment with β-blockers, and those who have experienced cardiac arrest. Genotype-phenotype correlative studies suggest that β-blockers are not effective in patients with LQT3, and an ICD is usually indicated. Recent studies have shown that the use of mexiletine is helpful in patients with LQT3.

Sinus Node Dysfunction

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

Sinus arrest and sinoatrial block may cause a sudden pause in the heartbeat. Sinus arrest is presumably caused by failure of impulse formation within the sinus node. Sinoatrial block results from a block between the sinus pacemaker complex and the surrounding atrium. These arrhythmias are rare in childhood except in patients who have had extensive atrial surgery.

Sick sinus syndrome is the result of abnormalities in the sinus node or atrial conduction pathways, or both. This syndrome may occur in the absence of CHD and has been reported in siblings, but it is most commonly seen after surgical correction of congenital heart defects, especially the Fontan procedure and the atrial switch (Mustard or Senning) operation for transposition of the great arteries. Clinical manifestations depend on the heart rate. Most patients remain asymptomatic without treatment, but dizziness and syncope can occur during periods of marked sinus slowing with failure of junctional escape. Pacemaker therapy is indicated in patients who experience symptoms such as exercise intolerance or syncope.

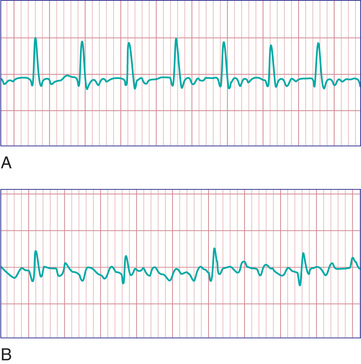

Patients with sinus node dysfunction may also have episodes of SVT (“tachy-brady” syndrome ) with symptoms of palpitations, exercise intolerance, or dizziness (Fig. 462.12 ). Treatment must be individualized. Drug therapy to control tachyarrhythmias (propranolol, sotalol, amiodarone) may suppress sinus and AV node function to such a degree that further symptomatic bradycardia may be produced. Therefore, insertion of a pacemaker in conjunction with drug therapy is usually necessary for such patients, even in the absence of symptoms ascribable to low heart rate.

Atrioventricular Block

Aarti S. Dalal, George F. Van Hare

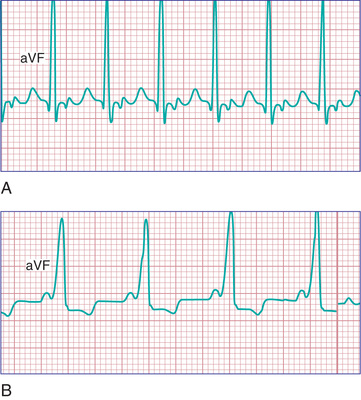

Atrioventricular block may be divided into 3 forms (Fig. 462.13 ). In first-degree AV block , the PR interval is prolonged, but all the atrial impulses are conducted to the ventricle. In second-degree AV block , not every atrial impulse is conducted to the ventricle. In the variant of second-degree block known as the Wenckebach type (also called Mobitz type I ), the PR interval increases progressively until a P wave is not conducted. In the cycle following the dropped beat, the PR interval normalizes. In Mobitz type II there is no progressive conduction delay or subsequent shortening of the PR interval after a blocked beat. This conduction defect is less common but has more potential to cause syncope and may be progressive. A related condition is high-grade second-degree AV block , in which 2 or more P waves in a row fail to conduct. This is even more dangerous. In third-degree AV block (complete heart block) , no impulses from the atria reach the ventricles. An independent escape rhythm is usually present but may not be reliable, leading to symptoms such as syncope.

Congenital complete AV block in children is presumed to be caused by autoimmune injury of the fetal conduction system by maternally derived immunoglobulin G antibodies (anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La) in a mother with overt or, more often, asymptomatic systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren syndrome. Autoimmune disease accounts for 60–70% of all cases of congenital complete AV block and 80% of cases in which the heart is structurally normal (Fig. 462.14 ). A mutation of the homeobox gene NKX2-5 is described in which congenital AV block is seen most often in association with atrial septal defects. Complete AV block is also seen in patients with complex CHD and abnormal embryonic development of the conduction system. It has been associated with myocardial tumors and myocarditis. Complete AV block is a known complication of myocardial abscess secondary to endocarditis. It is also seen in genetic abnormalities, including LQTS and Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Postoperative AV block can be a complication of CHD repair; in particular repairs involving ventricular septal defect closure.

The incidence of congenital complete AV block is 1 per 20,000-25,000 live births; a high fetal loss rate may cause an underestimation of its true incidence. In some infants of mothers with SLE, complete AV block is not present at birth but develops within the 1st 3-6 mo after birth. The arrhythmia is often diagnosed in the fetus (secondary to the dissociation between atrial and ventricular contractions seen on fetal echocardiography) and may produce hydrops fetalis. Maternal treatment with corticosteroids to halt progression or reverse AV block is controversial. Infants with associated CHD and heart failure have a high mortality rate.

In older children with otherwise normal hearts, complete AV block is often asymptomatic, although syncope and sudden death may occur. Infants and toddlers may have night terrors, tiredness with frequent naps, and irritability. The peripheral pulse is prominent because of the compensatory large ventricular stroke volume and peripheral vasodilation; systolic blood pressure is elevated. Jugular venous pulsations occur irregularly and may be large when the atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve (cannon wave). Exercise and atropine may produce an acceleration of 10-20 beats/min or more. Systolic murmurs are frequently audible along the left sternal border, and apical mid-diastolic murmurs are not unusual. The first heart sound is variable because of variable ventricular filing with AV dissociation. AV block results in enlargement of the heart based on increased diastolic ventricular filling.

The diagnosis is confirmed by electrocardiography; the P waves and QRS complexes have no constant relationship (see Fig. 462.14 ). The QRS duration may be prolonged, or it may be normal if the heartbeat is initiated high in the AV node or bundle of His.

The prognosis for congenital complete AV block is usually favorable; patients who have been observed to age 30-40 have lived normal, active lives. Some patients have episodes of exercise intolerance, dizziness, and syncope (Stokes-Adams attacks); syncope requires the implantation of a permanent cardiac pacemaker. Pacemaker implantation should be considered for patients who develop symptoms such as progressive cardiac dilation, prolonged pauses, or daytime average heart rates of ≤50 beats/min. In addition, prophylactic pacemaker implantation in adolescents is reasonable considering the low risk of the implant procedure and the difficulty in predicting who will develop sudden severe symptoms.

Cardiac pacing is recommended in neonates with low ventricular rates (≤55 beats/min), evidence of heart failure, wide complex rhythms, or CHD (with ventricular rates <70 beats/min). Isoproterenol, atropine, or epinephrine may be tried to increase the heart rate temporarily until pacemaker placement can be arranged. Transthoracic epicardial pacemaker implants have traditionally been used in infants; transvenous placement of pacemaker leads is available for young children. Postsurgical complete AV block can occur after any open heart procedure requiring suturing near the AV valves or crest of the ventricular septum. Postoperative heart block is initially managed with temporary pacing wires. The likelihood of a return to sinus rhythm after 10-14 days is low; a permanent pacemaker is recommended after that time.

PO dose

PO dose