Histiocytosis Syndromes of Childhood

Stephan Ladisch

The childhood histiocytoses constitute a diverse group of disorders that are frequently severe in their clinical expression. These disorders are individually rare and are grouped together because they have in common a prominent proliferation or accumulation of cells of the monocyte-macrophage system of bone marrow (myeloid) origin. Although these disorders sometimes are difficult to distinguish clinically, accurate diagnosis is essential for facilitating progress in treatment. A systematic classification of the histiocytoses is based on histopathologic findings (Table 534.1 ). A thorough, comprehensive evaluation of a biopsy specimen obtained at diagnosis is critical. This evaluation includes studies such as immunostaining, molecular analysis, and electron microscopy that may require special sample processing.

Table 534.1

Classification of the Childhood Histiocytoses

| DISEASE | CELLULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF LESIONS | TREATMENT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCH | Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Langerhans-like cells (CD1a positive, CD207 positive) with Birbeck granules (LCH cells) | Local therapy for isolated lesions; chemotherapy for disseminated disease |

| HLH | Familial (primary) hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | Morphologically normal reactive macrophages with prominent erythrophagocytosis and CD8+ T cells | Chemotherapy; allogeneic bone marrow transplantation |

| Infection-associated (secondary) hemophagocytic syndrome* | |||

| Associated with albinism syndromes † | |||

| Associated with immunocompromised states | |||

| Associated with autoimmune/autoinflammatory states | |||

| Other | Juvenile xanthogranuloma | Characteristic vacuolated lesional histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm | None or excisional biopsy for localized disease; chemotherapy, radiotherapy for disseminated disease |

| Rosai-Dorfman disease | Hemophagocytic histiocytes | None if localized; surgery for bulk reduction; chemotherapy if organ systems involvement | |

| Malignant histiocytosis | Neoplastic proliferation of cells with characteristics of monocytes-macrophages or their precursors | Antineoplastic chemotherapy, including anthracyclines | |

| Other | Acute monocytic (myelogenous) leukemia ‡ | M5 by FAB classification | Antineoplastic chemotherapy |

| ALK+ histiocytosis | Infiltration of large histiocytes, multinucleated with fine chromation; CD68, CD163, S100 protein, and ALK positive | Rare disorder of infants; treat with steroids and chemotherapy; may spontaneously regress. |

* Also called secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

† Chédiak-Higashi and Hermansky-Pudlak syndromes.

‡ See Chapter 522.2 .

FAB, French-American-British; LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Classification and Pathology

Three classes of childhood histiocytosis are defined, based on histopathologic findings. The best known is Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) , previously called histiocytosis X. LCH includes the clinical entities of bone or skin limited disease, eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and Letterer-Siwe disease. The normal Langerhans cell is an antigen-presenting cell (APC) of the skin. The hallmark of LCH in all forms is the presence of a clonal proliferation of cells of the monocyte–dendritic cell lineage containing the characteristic electron microscopic findings of a Langerhans cell, the Birbeck granule . This tennis racket–shaped bilamellar granule, when seen in the cytoplasm of lesional cells in LCH, is diagnostic of the disease. The Birbeck granule expresses a newly characterized antigen, langerin (CD207), which itself is involved in antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. CD207 expression has been established to be uniformly present in LCH lesions and thus becomes an additional reliable diagnostic marker. It is more likely that the LCH cell is not actually a (differentiated) Langerhans cell but rather an immature cell of myeloid origin, possibly in an arrested state of development. The definitive diagnosis of LCH is established by demonstrating CD1a positivity of lesional cells, which can be done using fixed tissue (Fig. 534.1 ). Lesional cells must be distinguished from normal Langerhans cells of the skin, which are also CD1a positive but are only sparsely distributed and not diagnostic of LCH. The peripheral lesions usually leading to the diagnosis (e.g., skin, lymph node, bone) contain various proportions of Birbeck granule–containing CD1a-positive cells, lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils.

Clonality of individual lesions exists in some cases of LCH. Importantly, an activating somatic mutation of the BRAF gene (V600E ) has been identified in many patients with LCH. Studies in patients negative for BRAFV600E have revealed mutations in other genes of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, including MAP2K1 and ARAF . With the majority of LCH patients having 1 or another of these activating mutations in the MAPK pathway, it has been suggested that LCH is driven by a disorder in MAPK signaling.

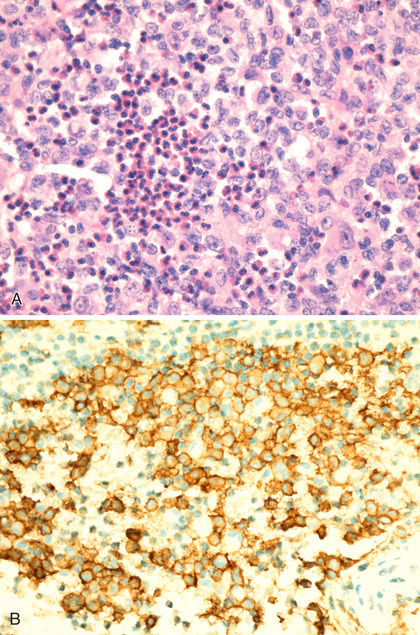

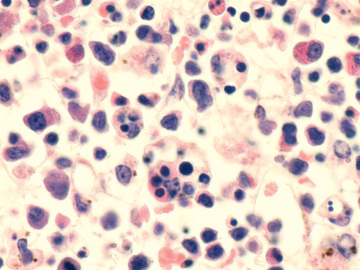

In contrast to the prominence of an APC in LCH, the other common form of histiocytosis is characterized by accumulation of activated APCs (macrophages and lymphocytes) and is known as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) . This diagnosis is the result of uncontrolled hemophagocytosis and uncontrolled activation (upregulation) of inflammatory cytokines with some similarities to the macrophage activation syndrome (see Table 180.6 ). Tissue infiltration by activated CD8 T lymphocytes, activated macrophages, and hypercytokinemia are classic features (Fig. 534.2 ). With the characteristic morphology of normal macrophages by light microscopy, these phagocytic cells (see Fig. 534.1 ) are CD163 positive but negative for the markers that are characteristic of LCH cells (Birbeck granules, CD1a, CD207).

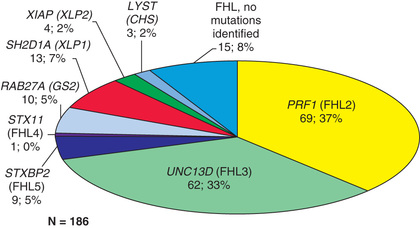

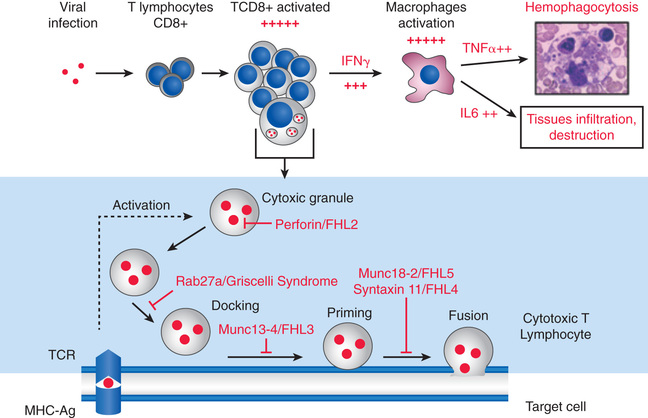

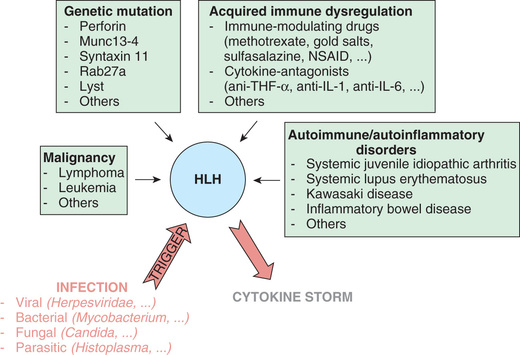

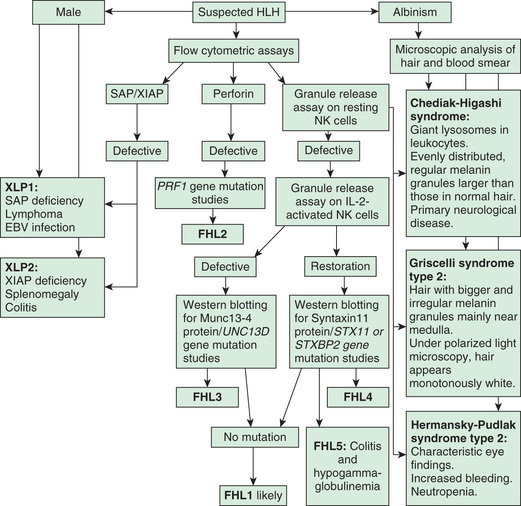

The 2 major forms of HLH have indistinguishable pathologic findings but are important to differentiate because of implications for treatment and prognosis. Primary HLH , originally named familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, is known as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHLH) . This disease is an autosomal recessive disorder and represents approximately 25% of patients with HLH (Table 534.2 ). Genes are known for 4 of the 5 familial HLH syndromes and other hereditary causes of HLH; these mutations affect the ability of T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells to synthesize and release perforin and granzymes, thus reducing cytotoxic granule formation (Fig. 534.3 ). The other form of HLH, originally called infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, is recognized as secondary HLH (Table 534.3 ). Both disease processes affect multiple organs and are characterized by massive infiltrates of hyperactivated lymphocytes and activated phagocytic macrophages in the involved organs, with the lymphocytes serving as the driver of the resulting disease process.

Table 534.2

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

| DISEASE | GENE | PROTEIN | PERCENTAGE OF FHLH | IMMUNE IMPAIRMENT | UNIQUE CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHLH-16 | Unknown 9q21.3–22 | Rare | |||

| FHLH-2 | PRF1 | Perforin | ~20–37, 50delT mainly in African American/African descent | Cytotoxicity; forms pores in APCs | |

| FHLH-3 | UNC13D | Munc13–4 | 20–33 | Cytotoxicity; vesicle priming | Increased incidence of CNS HLH |

| FHLH-4 | STX11 | Syntaxin | <5 | Cytotoxicity; vesicle fusion | Mild recurrent HLH, colitis |

| FHLH-5 | STXBP2 | Syntaxin-binding protein 2 | 5–20 | Cytotoxicity; vesicle fusion | Colitis, hypogammaglobulinemia |

| SYNDROMES WITH PARTIAL OCULOCUTANEOUS ALBINISM | |||||

| Griscelli syndrome | RAB27A | Rab27A | ~5 | Cytotoxicity; vesicle docking | Partial albinism, silver-gray hair |

| Chédiak-Higashi syndrome | LYST | Lyst | ~2 | Cytotoxicity; heterogeneous defects in NK cells | Partial albinism, bleeding tendency, recurrent infections |

| Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type II | AP3B1 | AP-3 complex subunit β1 | Rare | Cytotoxicity; vesicle trafficking | Partial albinism, bleeding tendency |

| EBV-DRIVEN AND RARE CAUSES | |||||

| XLP1 | SH2D1A | SAP | ~7 | Signaling in cytotoxic NK and T cells | Hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphoma |

| XLP2 | BIRC4 | XIAP | ~2 | NK T-cell survival and NF-κB signaling | Mild recurrent HLH, colitis |

| ITK deficiency | ITK | ITK | Rare | IL-2 signaling in T cells | Hypogammaglobulinemia, autoimmunity, Hodgkin lymphoma |

| CD27 deficiency | CD27 | CD27 | Rare | Signal transduction in lymphocytes | Combined immunodeficiency, lymphoma |

| XMEN syndrome | MAGT1 | MAGT1 | Rare | Magnesium transporter, induced by TCR stimulation | Lymphoma, recurrent infections, CD4 T-cell lymphopenia |

APCs, Antigen-presenting cells; CNS, central nervous system; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; FHLH, familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; ITK, interleukin (IL)-2–inducible T-cell kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor–kappa B; NK, natural killer; TCR, T-cell receptor.

Adapted from Erker C, Harker-Murray, Talano JA: Usual and unusual manifestations of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Pediatr Clin North Am 64:91–109, 2017 (Table 1, p 95).

Table 534.3

Infections Associated With Hemophagocytic Syndrome

| VIRAL |

| BACTERIAL |

| FUNGAL |

| MYCOBACTERIAL |

| RICKETTSIAL |

| PARASITIC |

From Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, et al, editors: Nathan and Oski's hematology of infancy and childhood , ed 6, Philadelphia, 2003, Saunders, p 1381.

In primary HLH, genetic mutations in multiple different steps in granule formation and release by cytotoxic T cells have been identified (Fig. 534.4 , bottom ). Mutations in the PRF1 perforin gene or the MUNC13-4 gene are the most common causes of defective function of the cytotoxic lymphocytes whose activity is inhibited in primary HLH. In an analogous way, a trigger can result in secondary HLH (Fig. 534.4, top ). A myriad of both infectious and noninfectious processes can trigger secondary HLH (Tables 534.3 and 534.4 and Fig. 534.5 ). Examples of noninfectious triggers include drugs (e.g., phenytoin, highly active antiretroviral therapy), hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and immunodeficiency states (e.g., DiGeorge syndrome, Bruton agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome, chronic granulomatous disease).

Table 534.4

Spectrum of Diseases Characterized by Hemophagocytosis

|

Primary HLH (see Table 534.2 ) HLH with immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory states (see Table 534.2 ) Infection-associated HLH (see Table 534.3 ) Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) associated with autoimmune disease |

HLH, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

In addition to these 2 most common forms of childhood histiocytosis (LCH and HLH), a number of rarer diseases are included under this rubric. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is characterized by vacuolated histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm in lesions that evolve into mixed granulomas also containing eosinophils, lymphocytes, and other cells. Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) predominantly affects adults. Surface markers suggest a link among LCH, JXG, and ECD; all 3 are dendritic cell diseases, with BRAFV600E mutations in the affected cells. Another rare form of histiocytosis is Rosai-Dorfman disease , also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Rosai-Dorfman disease is characterized by packing of sinusoids of the lymph nodes with hemophagocytic histiocytes, although extranodal involvement may also be present. Lastly, there is a group of unequivocal malignancies of cells of monocyte-macrophage lineage. By this definition, acute monocytic leukemia and true malignant histiocytosis are included among the class III histiocytoses (see Chapter 522 ). True neoplasms of Langerhans cells have been reported but are extremely rare.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Stephan Ladisch

Clinical Manifestations

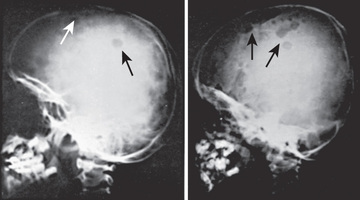

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) has an extremely variable presentation. The skeleton is involved in 80% of patients and may be the only affected site, especially in children >5 yr old. Bone lesions may be single or multiple and are seen most often in the skull (Fig. 534.6 ). Other sites include the pelvis, femur, vertebra, maxilla, and mandible. Lesions may be asymptomatic or associated with pain and local swelling. Involvement of the spine may result in collapse of the vertebral body, which can be seen radiographically and may cause secondary compression of the spinal cord. In flat and long bones, osteolytic lesions with sharp borders occur, and no evidence exists of reactive new bone formation until the lesions begin to heal. Lesions that involve weight-bearing long bones may result in pathologic fractures. Chronically draining, infected ears are usually associated with destruction in the mastoid area. Bone destruction in the mandible and maxilla may result in teeth that appear to be free floating on radiographs. With response to therapy, healing is usually complete.

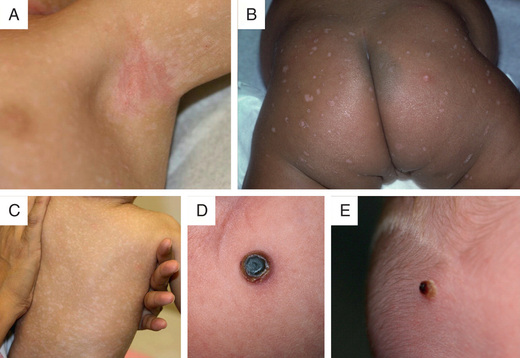

Approximately 50% of patients experience skin involvement (isolated or part of multisystem involvement) at some time during the course of disease, usually as a difficult-to-treat scaly, papular, seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, diaper, axillary, or posterior auricular regions (Figs. 534.7 and 534.8 ). The lesions may spread to involve the back, palms, and soles. The exanthem may be petechial or hemorrhagic, even in the absence of thrombocytopenia. Localized or disseminated lymphadenopathy is present in approximately 33% of patients. Hepatosplenomegaly occurs in approximately 20% of patients. Various degrees of hepatic malfunction may occur, including jaundice and ascites.

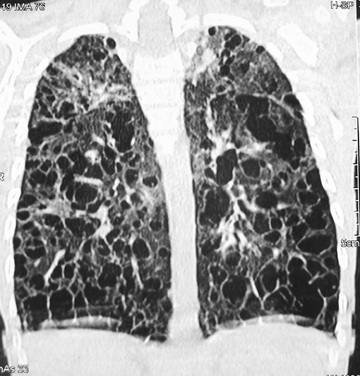

Exophthalmos, when present, often is bilateral and is caused by retroorbital accumulation of granulomatous tissue. Gingival mucous membranes may be involved with infiltrative lesions that appear superficially like candidiasis. Otitis media is present in 30–40% of patients; deafness may follow destructive lesions of the middle ear. In 10–15% of patients, pulmonary infiltrates are found on radiography. The lesions may range from diffuse fibrosis and disseminated nodular infiltrates to diffuse cystic changes (Fig. 534.9 ). Rarely, pneumothorax is a complication. If the lungs are severely involved, tachypnea and progressive respiratory failure may result.

Pituitary dysfunction or hypothalamic involvement may result in growth retardation. In addition, patients may have diabetes insipidus; patients suspected of having LCH should demonstrate the ability to concentrate their urine before going to the operating room for a biopsy. Rarely, panhypopituitarism may occur. Primary hypothyroidism as a result of thyroid gland infiltration also may occur.

Patients with multisystem disease who are affected more severely are those who have systemic manifestations, including fever, weight loss, malaise, irritability, and failure to thrive. These systemic manifestations will distinguish patients at high risk of mortality (i.e., risk organ–positive patients) from patients at low risk of mortality (i.e., without systemic manifestations; risk organ–negative patients). The risk organs are liver, spleen, and the hematopoietic (bone marrow) system. The lung is not considered a risk organ. The distinction of risk-organ involvement is important for deciding the intensity of the treatment approach and has been addressed in standard treatment approaches for LCH, as delineated in the Histiocyte Society protocols. Bone marrow involvement may cause anemia and thrombocytopenia. Two uncommon but serious manifestations of LCH are hepatic involvement (leading to fibrosis and cirrhosis) and a peculiar central nervous system (CNS) involvement characterized by ataxia, dysarthria, and other neurologic symptoms. Hepatic involvement is associated with multisystem disease that is often already present at diagnosis. In contrast, the CNS involvement , which is progressive and histopathologically characterized by gliosis and has no known treatment, may be observed only many years after the initial diagnosis of LCH. These manifestations are not associated with LCH cells, Birbeck granules, CD1a positivity, or any other indication of LCH cell infiltration, raising questions about their pathogenesis.

After tissue biopsy, which is diagnostic and is easiest to perform on skin or bone lesions, a thorough clinical and laboratory evaluation should be undertaken. This should include a series of studies in all patients: complete blood cell count, liver function tests, coagulation studies, skeletal survey, chest radiograph, and measurement of urine osmolality. In addition, detailed evaluation of any organ system shown to be involved by physical examination or by these studies should be performed to establish the extent of disease before initiation of treatment.

Treatment and Prognosis

The clinical course of single-system disease (usually bone, lymph node, or skin) generally is benign, with a high chance of spontaneous remission. Therefore, treatment should be minimal and should be directed at arresting the progression of a bone lesion that could result in permanent damage before it resolves spontaneously. Curettage or, less often, corticosteroid injection or low-dose local radiation therapy (5-6 Gy) may accomplish this goal.

In contrast, multisystem disease requires treatment with systemic multiagent chemotherapy. Several different regimens have been proposed, but central elements are the inclusion of vinblastine and corticosteroids, both of which have been found to be very effective in treating LCH. Etoposide has been excluded from standard treatment of multisystem LCH, which is treated with multiple agents, designed to reduce mortality, reactivation of disease, and long-term consequences. The response rate to therapy is quite high, and mortality in severe LCH has been substantially reduced by multiagent chemotherapy, especially if the diagnosis is made accurately and expeditiously. The most recent treatment results associated with lengthened continuation therapy show a greater than 85% survival rate in severe (risk organ–positive) multisystem disease and a reduced rate of reactivation.

Experimental therapies are suggested only for unresponsive disease (often in very young children with multisystem disease and organ dysfunction who have not responded to multiagent initial treatment) and reactivation of risk organ–positive disease in risk organs, but not in reactivation of mild disease (any risk organ–negative reactivations). The approaches include immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporine/antithymocyte globulin and possibly imatinib, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, clofarabine, and stem cell transplantation. With the discovery of the BRAFV600E mutation causing hyperactivation of the MAPK pathway in LCH cells, pharmacologic inhibition of BRAF and pharmacologic inhibition of MEK are being investigated as therapeutic approaches for resistant disease.

Late (fibrotic) complications, whether hepatic or pulmonary, are irreversible and require organ transplantation to be definitively treated. Current treatment approaches and experimental protocols for both LCH and HLH can be obtained at the Histiocyte Society website (http://www.histiocytesociety.org ). An unresolved problem is treatment of the (usually late-onset) severe, progressive, and intractable LCH-associated neurodegenerative syndrome .

Bibliography

Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood . 2015;126(1):26–35.

Allen CE, Li L, Peters TL, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal langerhans cells. J Immunol . 2010;184(8):4557–4567.

Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood . 2010;116(11):1919–1923.

Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol . 2010;146:149–156.

Broadbent V, Gadner H, Komp DM, et al. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. II. Approach to the clinical and laboratory evaluation of children with langerhans cell histiocytosis. Clinical writing group of the histiocyte society. Med Pediatr Oncol . 1989;17(6):492–495.

Chakraborty R, Hampton OA, Shen X, et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent somatic mutations in MAP2K1 and BRAF support a central role for ERK activation in LCH pathogenesis. Blood . 2014;124(19):3007–3015.

Chan JKC, Lamant L, Algar E, et al. ALK+ histiocytosis: a novel type of systemic histiocytic proliferative disorder of early infancy. Blood . 2008;112(7):2965–2967.

Chauhan L, Aggarwal N. Honey-comb langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr . 2016;168:248.

Coury F, Annels N, Rivollier A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis reveals a new IL-17a-dependent pathway of dendritic cell fusion. Nat Med . 2008;14:81–87.

Ehrhardt MJ, Humphrey SR, Kelly ME, et al. The natural history of skin-limited langerhans cell histiocytosis: a single-institution experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol . 2014;36(8):613–616.

Gadner H, Minkov M, Grois N, et al. Therapy prolongation improves outcome in multisystem langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood . 2013;121:5006–5014.

Grois N, Fahrner B, Arceci RJ, et al. Central nervous system disease in langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr . 2010;156(6):873–881.

Lau S, Chu P, Weiss M. Immunohistochemical expression of langerin in langerhans cell histiocytic disorders. Am J Surg Pathol . 2008;32:615–619.

Minkov M, Steiner M, Potschger U, et al. Reactivations in multisystem langerhans cell histiocytosis: data of the international LCH registry. J Pediatr . 2008;153:700–705.

Ronceray L, Pötschger U, Janka G, et al. Pulmonary involvement in pediatric-onset multisystem langerhans cell histiocytosis: effect on course and outcome. J Pediatr . 2012;161(1):129–133 [e1–3].

Schmitt AR, Wetter DA, Camilleri MJ, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a blueberry muffin rash. Lancet . 2017;390:155.

Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr . 2014;165:990–996.

Wnorowski M, Prosch H, Prayer D, et al. Pattern and course of neurodegeneration in langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr . 2008;153:127–132.

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

Stephan Ladisch

See Classification and Pathology at start of chapter .

Clinical Manifestations

Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHLH) and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) have remarkably similar presentations, consisting of a generalized disease process, most often with fever (90–100%), maculopapular and/or petechial rash (10–60%), weight loss, and irritability. The initial clinical presentation can vary but is almost always very severe and, in the case of secondary HLH, may be camouflaged by a primary disease process. Acute presentations include septic shock, acute respiratory distress, seizures, and coma (because of CNS infiltration). Other features that are frequently present result from bone marrow involvement and pancytopenia or hepatic dysfunction.

Children with primary HLH are generally <1-2 yr old, and children with secondary HLH typically present at an older age, but both forms may present at any age. Physical examination often reveals hepatosplenomegaly (70–100%), lymphadenopathy (20–50%), respiratory distress (40–90%), jaundice, and symptoms of CNS involvement (50%) that are not unlike those of aseptic meningitis or acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (see Chapter 618.4 ). MRI may demonstrate systemic T2-weighted/FLAIR hyperintensities in gray and white matter and in supratentorial and infratentorial regions. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis (50–90%) associated with CNS involvement in primary HLH is characterized by cells that are the same phagocytic macrophages found in the peripheral blood or bone marrow. Primary HLH is also generally associated with severe immunodeficiency.

The diagnosis of HLH is arrived at in 2 stages. The 1st stage is based on a set of 8 clinical and laboratory findings, with the presence of 5 of the 8 being diagnostic of HLH. The 8 findings, formulated by the Histiocyte Society, are fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia of 2 cell lines (in 90–100%), hypertriglyceridemia (80–100%) or hypofibrinogenemia (65–85%), hyperferritinemia (≥500 but often >10,000), extremely elevated soluble CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor), reduced or absent NK cell activity, and bone marrow, CSF, or lymph node evidence of hemophagocytosis (Table 534.5 ). The 2nd stage involves genetic analysis for mutations and is undertaken as quickly as possible, but generally requires some time to complete and should not interfere with initiation of treatment (Fig. 534.10 ). The genetic findings and family history will determine whether the diagnosis is (autosomal recessive) primary HLH or secondary HLH.

Table 534.5

Diagnostic Guidelines for Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)

Adapted from VerbskyJW, Grossman WJ: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology, treatment, and future perspectives, Ann Med 38:20–31, 2006 (Table 1, p 21).

Hemophagocytosis is not specific for HLH and should be considered in the context of the diagnostic criteria. No absolute clinical or laboratory distinction can be made between primary HLH and secondary HLH. In some subgroups of HLH, perforin assays may be normal. Similarly, some patients with primary FHLH have no known identifiable gene mutation.

In the absence of either (1) a documented genetic defect coupled with defective NK cell cytotoxicity or (2) frank hemophagocytosis, care should be taken in making the diagnosis of secondary HLH, given the implication to use cytotoxic chemotherapy. The nonspecific criteria (indicative of inflammation) used to diagnose HLH can also be seen in diseases that are not always associated with hemophagocytosis (e.g., overwhelming acute viral infection with appropriate T-cell activation), in which the cytotoxic and immunosuppressive therapy used in treating HLH might be contraindicated.

Macrophage activation syndrome , particularly in the context of systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) or infection, has many similarities to HLH (see Chapter 180 ). Indeed, whole exome sequencing of patients with systemic-onset JIA or those with fatal influenza has revealed a higher-than-expected incidence of HLH genes. Other disorders in the differential diagnosis of HLH include sepsis, Wolman disease, osteopetrosis, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, neonatal hemochromatosis, Gaucher disease, combined immunodeficiency disease, and common variable immunodeficiency disease.

Treatment and Prognosis

Therapy for primary HLH (autosomal recessive genetic disease or familial occurrence) consists of a combination of etoposide, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and intrathecal methotrexate, as described in the current Histiocyte Society HLH-1994 and HLH-2004 protocols. It should be stressed that pancytopenia and the presence of an infection are not contraindications to cytotoxic therapy. Some recommend antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for maintenance therapy. The goal is to reach the point of initiating stem cell transplantation . To date, this is the only known potentially curative treatment for primary HLH and is effective in achieving cure in >60% of patients. Chemotherapy is inadequate for sustained cure of primary HLH, which is ultimately fatal without transplantation.

In secondary HLH , it is critical that the underlying disease (e.g., infection, malignancy) be identified and successfully treated. The diagnostic distinction between primary HLH and secondary HLH sometimes can be based on the acute onset of secondary HLH in the presence of a documented infection. In this case, treatment of the underlying infection is coupled with supportive care. If the diagnosis is made in the setting of iatrogenic immunodeficiency, immunosuppressive treatment should be withdrawn and supportive care instituted along with specific therapy for the underlying infection. In many patients the prognosis is excellent without additional specific treatment other than treating the triggering infection. However, when a treatable infection or other cause cannot be documented, and when the clinical presentation is severe, the prognosis for secondary HLH is as poor as for primary HLH. These patients should receive the identical initial 8 wk chemotherapeutic approach, including etoposide, even in the face of cytopenias. In both primary and secondary HLH, the cytotoxic effect of etoposide on macrophages interrupts cytokine production, the hemophagocytic process, and the accumulation of macrophages, all of which may contribute to the pathogenesis of infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome . A broad spectrum of infectious agents, including viruses (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6), fungi, protozoa, and bacteria, may trigger secondary HLH, often in the setting of immunodeficiency (see Table 534.3 ). A thorough evaluation for infection should be undertaken in immunodeficient patients with hemophagocytosis. The same syndrome may be identified in conjunction with a rheumatologic disorder (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease) or a neoplasm (e.g., leukemia). In these patients, effective treatment of the underlying disease (e.g., infection, cancer) is critical and may itself lead to ultimate resolution of the hemophagocytosis.

Bibliography

Bode SFN, Bogdan C, Beutel K, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in imported pediatric visceral leishmaniasis in a nonendemic area. J Pediatr . 2014;165:147–153.

Brisse E, Wouters CH, Matthys P. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): a heterogeneous spectrum of cytokine-driven immune disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev . 2015;26:263–280.

Canna SW, Behrens EM. Making sense of the cytokine storm: a conceptual framework for understanding, diagnosing, and treating hemophagocytic syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2012;59:329–344.

Cetica V, Sieni E, Pende D, et al. Genetic predisposition to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: report on 500 patients from the Italian registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2016;137:188–196.

Chandrakasan S, Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Pediatr . 2013;163(5):1253–1259.

Cheng A, Williams F, Fortenberry J, et al. Use of extracorporeal support in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to ehrlichiosis. Pediatrics . 2016;138(4):e20154176.

Deiva K, Mahlaoui N, Beaudonnet F, et al. CNS involvement at the onset of primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Neurology . 2012;78:1150–1156.

Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J. Diverse and targetable kinase alterations drive histiocytic neoplasms. Cancer Discov . 2016;6(2):154–165.

Guandalini M, Butler A, Mandelstam S. Spectrum of imaging appearances in Australian children with central nervous system hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Neurosci . 2014;21:305–310.

Hara S, Kawada J, Kawano Y, et al. Hyperferritinemia in neonatal and infantile human parechovirus-3 infection in comparison with other infectious diseases. J Infect Chemother . 2014;20:15–19.

Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2007;48(2):124–131.

Horne AC, Trottestam H, Arico M, et al. Frequency and spectrum of central nervous system involvement in 193 children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol . 2007;140:327–335.

Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Med . 2012;63:233–246.

Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes: an update. Blood Rev . 2014;28:135–142.

Kaufman KM, Linghu B, Szustakowski JD, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals overlap between macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arth Rheum . 2014;66(12):3486–3495.

Lehmberg K, Ehl S. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol . 2013;160:275–287.

Lehmberg K, Pink I, Eulenburg C, et al. Differentiating macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other forms of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr . 2013;162(6):1245–1251.

Mahlaoui N, Iuachee-Chardin M, de Saint Basile G, et al. Immunotherapy of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with antithymocyte globulins: a single-center retrospective report of 38 patients. Pediatrics . 2007;120:e622–e628.

Mischler M, Fleming GM, Shanley TP, et al. Epstein-barr virus–induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and X-linked lymphoproliferative disease: a mimicker of sepsis in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics . 2007;119:e1212–e1218.

Ouachee-Chardin M, Elie C, de Saint Basile G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a single-center report of 48 patients. Pediatrics . 2006;117:e743–e750.

Rajasekaran S, Kruse K, Kovey K, et al. Therapeutic role of anakinra, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in the management of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction/macrophage activating syndrome in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med . 2014;15:401–408.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet . 2014;383:1503–1514.

Risma K, Jordan MB. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: updates and evolving concepts. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2012;24(1):9–15.

Rudman Spergel A, Walkovich K, Price S, et al. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome misdiagnosed as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatrics . 2013;132(5):e1440–e1444.

Schulert GS, Zhang M, Husami NF, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals mutations in genes linked to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and macrophage activation syndrome in fatal cases of h1n1 influenza. J Infect Dis . 2016;213:1180–1188.

Sen ES, Steward CG, Ramanan AV. Diagnosing haemophagocytic syndrome. Arch Dis Child . 2017;102:279–284.

Sharp TM, Gaul L, Muehlenbachs A, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). Fatal hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with locally acquired dengue virus infection—new Mexico and texas, 2012. MMWR . 2014;63(3):49–54.

Trottestam H, Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Blood . 2011;118(17):4577–4584.

Valentine G, Thomas TA, Nguyen T, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease presenting as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a case report. Pediatrics . 2014;134:e1727–e1730.

Weitzman S. Approach to hemophagocytic syndromes. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program . 2011;2011:178–183.

Other Histiocytoses

Stephan Ladisch

Other rare histiocytoses have been named for their clinical presentation. Examples include xanthogranuloma in juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) and striking lymphadenopathy in Rosai-Dorfman disease (sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy). JXG may require systemic treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy or potentially MAPK pathway inhibitors, reflecting the presence of a BRAF mutation. Rosai-Dorfman disease usually is not treated, although the massive lymphadenopathy may require intervention because of its tendency to cause physical obstruction. Acute monocytic leukemia and true malignant histiocytosis are included because they are unequivocal malignancies of the monocyte-macrophage lineage (see Chapter 522 ).

Bibliography

Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life: a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol . 2005;29(1):579–593.

Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Histiocyte society: revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage–dendritic cell lineages. Blood . 2016;127:2672–2681.

Pulsoni A, Anghel G, Falcucci P, et al. Treatment of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (rosai-dorfman disease): report of a case and literature review. Am J Hematol . 2002;69(1):67–71.

Weitzman S, Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non–langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2005;45(3):256–264.