The Leukemias

David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, A. Kim Ritchey, Erika Friehling

The leukemias are the most common malignant neoplasms in childhood, accounting for approximately 31% of all malignancies that occur in children younger than 15 yr. Each year, leukemia is diagnosed in approximately 3,100 children and adolescents <20 yr old in the United States, an annual incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 children. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) accounts for approximately 77% of cases of childhood leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) for approximately 11%, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) for 2–3%, and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) for 1–2%. The remaining cases consist of a variety of acute and chronic leukemias that do not fit classic definitions for ALL, AML, CML, or JMML.

The leukemias may be defined as a group of malignant diseases in which genetic abnormalities in a hematopoietic cell give rise to an unregulated clonal proliferation of cells. The progeny of these cells have a growth advantage over normal cellular elements because of their increased rate of proliferation and a decreased rate of spontaneous apoptosis. The result is a disruption of normal marrow function and, ultimately, marrow failure. The clinical features, laboratory findings, and responses to therapy vary depending on the type of leukemia.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Erika Friehling, A. Kim Ritchey, David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL ) was the first disseminated cancer shown to be curable. It actually is a heterogeneous group of malignancies with a number of distinctive genetic abnormalities that result in varying clinical behaviors and responses to therapy.

Epidemiology

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is diagnosed in approximately 3,100 children and adolescents <20 yr old in the United States each year. ALL has a striking peak incidence at 2-3 yr of age and occurs more in boys than in girls at all ages. This peak age incidence was apparent decades ago in white populations in advanced socioeconomic countries, but it has since been confirmed in the black population of the United States as well. The disease is more common in children with certain chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down syndrome, Bloom syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, and Fanconi anemia. Among identical twins, the risk to the second twin if one twin develops leukemia is greater than that in the general population. The risk is >70% if ALL is diagnosed in the first twin during the 1st yr of life and the twins shared the same (monochorionic) placenta. If the first twin develops ALL by 5-7 yr of age, the risk to the second twin is at least twice that of the general population, regardless of zygosity.

Etiology

In virtually all cases, the etiology of ALL is unknown, although several genetic and environmental factors are associated with childhood leukemia (Table 522.1 ). Most cases of ALL are thought to be caused by postconception somatic mutations in lymphoid cells. However, the identification of the leukemia-specific fusion-gene sequences in archived neonatal blood spots of some children who develop ALL at a later date indicates the importance of in utero events in the initiation of the malignant process in some cases. The long lag period before the onset of the disease in some children, reported to be as long as 14 yr, supports the concept that additional genetic modifications are required for disease expression. Moreover, those same mutations have been found in neonatal blood spots of children who never go on to develop leukemia.

Table 522.1

Factors Predisposing to Childhood Leukemia

|

GENETIC CONDITIONS ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS |

Exposure to medical diagnostic radiation both in utero and in childhood is associated with an increased incidence of ALL. In addition, published descriptions and investigations of geographic clusters of cases have raised concern that environmental factors can increase the incidence of ALL. Thus far, no such factors other than radiation have been identified in the United States. In certain developing countries, there is an association between B-cell ALL (B-ALL ) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infections.

Cellular Classification

The classification of ALL depends on characterizing the malignant cells in the bone marrow to determine the morphology, phenotype as measured by cell membrane markers, and cytogenetic and molecular genetic features. Morphology is usually adequate alone to establish a diagnosis, but the other studies are essential for disease classification, which can have a major influence on the prognosis and the choice of appropriate therapy. The current system used is the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of leukemias. Phenotypically, surface markers show that approximately 85% of cases of ALL are classified as B-lymphoblastic leukemia (previously termed precursor B-ALL or pre–B-ALL), approximately 15% are T-lymphoblastic leukemia, and approximately 1% are derived from mature B cells. The rare leukemia of mature B cells is termed Burkitt leukemia and is one of the most rapidly growing cancers in humans, requiring a different therapeutic approach than other subtypes of ALL. A small percentage of children with leukemia have a disease characterized by surface markers of both lymphoid and myeloid derivation.

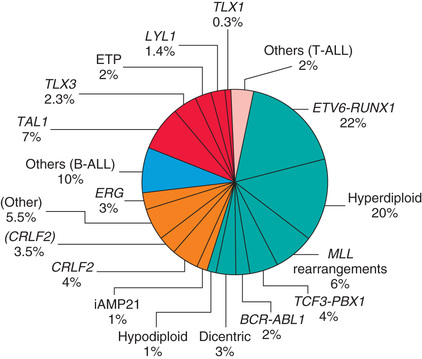

Chromosomal abnormalities are used to subclassify ALL into prognostic groups (Table 522.2 ). Many genetic alterations, including inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes and mutations that activate the NOTCH1 or RAS pathways, have been discovered and in the future might be incorporated into clinical practice (Fig. 522.1 ).

Table 522.2

Common Chromosomal Abnormalities in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia of Childhood

| SUBTYPE | CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITY | GENETIC ALTERATION | PROGNOSIS | INCIDENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-ALL | Trisomies 4, 10, and 17 | — | Favorable | 25% |

| B-ALL | t(12;21) | ETV6-RUNX1 | Favorable | 20–25% |

| B-ALL | t(1;19) | TCF3-PBX1 | None | 5–6% |

| B-ALL | t(4;11) | KMT2A(MLL)-AF4 | Unfavorable | 2% |

| B-ALL | t(9;22) | BCR-ABL | Unfavorable | 3% |

| Mature B-cell leukemia (Burkitt) | t(8;14) | IGH-MYC | None | 1–2% |

| B-ALL | Hyperdiploidy | — | Favorable | 20–25% |

| B-ALL | Hypodiploidy | — | Unfavorable | 1% |

| T-ALL | t(10;14) | TLX1/HOX11 | Favorable | 5–10% |

| Infant | 11q23 | KMT2A(MLL) rearrangements | Unfavorable | 2–10% |

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques offer the ability to pinpoint molecular genetic abnormalities and can be used to detect small numbers of malignant cells at diagnosis as well as during follow-up (minimal residual disease [MRD] , see later) and are of proven clinical utility. The development of DNA microarray makes it possible to analyze the expression of thousands of genes in the leukemic cell. This technique promises to further enhance the understanding of the fundamental biology and to provide clues to the therapeutic approach of ALL.

Clinical Manifestations

The initial presentation of ALL usually is nonspecific and relatively brief. Anorexia, fatigue, malaise, irritability, and intermittent low-grade fever are often present. Bone or joint pain, particularly in the lower extremities, may be present. Less often, symptoms may be of several months’ duration, may be localized predominantly to the bones or joints, and may include joint swelling. Bone pain is severe and can wake the patient at night. As the disease progresses, signs and symptoms of bone marrow failure become more obvious with the occurrence of pallor, fatigue, exercise intolerance, bruising, oral mucosal bleeding or epistaxis, as well as fever, which may be caused by infection or the disease. Organ infiltration can cause lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, testicular enlargement, or central nervous system (CNS) involvement (cranial neuropathies, headache, seizures). Respiratory distress may be caused by severe anemia or mediastinal node compression of the airways.

On physical examination, findings of pallor, listlessness, purpuric and petechial skin lesions, or mucous membrane hemorrhage can reflect bone marrow failure (see Chapter 520 ). The proliferative nature of the disease may be manifested as lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or, less often, hepatomegaly. Patients with bone or joint pain may have exquisite tenderness over the bone or objective evidence of joint swelling and effusion. Nonetheless, with marrow involvement, deep bone pain may be present, but tenderness will not be elicited. Rarely, patients show signs of increased intracranial pressure that indicate leukemic involvement of the CNS. These include papilledema (see Fig. 520.3 ), retinal hemorrhages, and cranial nerve palsies. Respiratory distress usually is related to anemia but can occur in patients as the result of a large anterior mediastinal mass (e.g., in the thymus or nodes). This problem is most frequently seen in adolescent boys with T-cell ALL. T-ALL also usually has a higher leukocyte count.

B-lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common immunophenotype, with onset at 1-10 yr of age. The median leukocyte count at presentation is 33,000/µL, although 75% of patients have counts <20,000/µL; thrombocytopenia is seen in 75% of patients and hepatosplenomegaly in 30–40% of patients. In all types of leukemia, CNS symptoms are seen at presentation in 5% of patients (10–15% have blasts in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]). Testicular involvement is rarely evident at diagnosis, but prior studies indicate occult involvement in 25% of boys. There is no indication for testicular biopsy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ALL is strongly suggested by peripheral blood findings that indicate bone marrow failure. Anemia and thrombocytopenia are seen in most patients. Leukemic cells might not be reported in the peripheral blood in routine laboratory examinations. Many patients with ALL present with total leukocyte counts of <10,000/µL. In such cases, the leukemic cells often are reported initially to be “atypical lymphocytes,” and it is only on further evaluation that the cells are found to be part of a malignant clone. When the results of an analysis of peripheral blood suggest the possibility of leukemia, the bone marrow should be examined promptly to establish the diagnosis. It is important that all studies necessary to confirm a diagnosis and adequately classify the type of leukemia be performed, including bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular studies.

ALL is diagnosed by a bone marrow evaluation that demonstrates >25% of the bone marrow cells as a homogeneous population of lymphoblasts. Initial evaluation also includes CSF examination. If lymphoblasts are found and the CSF leukocyte count is elevated, overt CNS or meningeal leukemia is present. This finding reflects a poorer stage and indicates the need for additional CNS and systemic therapies. The staging lumbar puncture (LP) may be performed in conjunction with the first dose of intrathecal chemotherapy, if the diagnosis of leukemia was previously established from bone marrow evaluation. An experienced proceduralist should perform the initial LP, because a traumatic LP is associated with an increased risk of CNS relapse.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of leukemia is readily made in the patient with typical signs and symptoms, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with blasts present on smear. Elevation of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is often a clue to the diagnosis of ALL. When only pancytopenia is present, aplastic anemia (congenital or acquired), myelofibrosis, and familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis should be considered. Failure of a single cell line, as seen in transient erythroblastopenia of childhood, immune thrombocytopenia, and congenital or acquired neutropenia, is rarely the presenting feature of ALL. A high index of suspicion is required to differentiate ALL from infectious mononucleosis in patients with acute onset of fever and lymphadenopathy and from juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients with fever, bone pain but often no tenderness, and joint swelling. These presentations also can require bone marrow examination.

ALL must be differentiated from AML and other malignant diseases that invade the bone marrow and can have clinical and laboratory findings similar to ALL, including neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and retinoblastoma.

Treatment

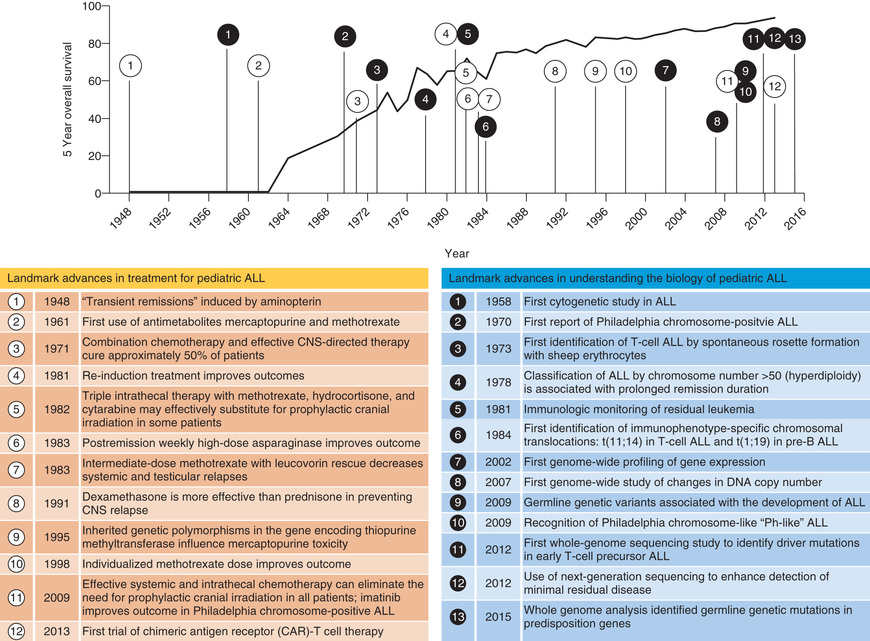

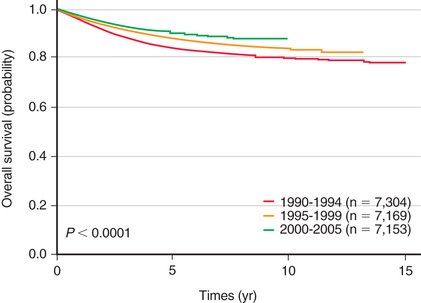

The single most important prognostic factor in ALL is the treatment: without effective therapy, the disease is fatal. Considerable progress has been made in overall survival for children with ALL since the 1970s through use of multiagent chemotherapeutic regimens, intensification of therapy, and selection of treatment based on relapse risk (Fig. 522.2 ). Survival is also related to age (Fig. 522.3 ) and subtype (Fig. 522.4 ).

Risk-directed therapy is the standard of current ALL treatment and accounts for age at diagnosis, initial WBC count, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic characteristics of blast populations, rapidity of early treatment response (i.e., how quickly the leukemic cells can be cleared from the marrow or peripheral blood), and assessment of MRD at the end of induction therapy. Different study groups use various factors to define risk, but age 1-10 yr and a leukocyte count <50,000/µL are used by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to define standard risk. Children who are younger than 1 yr or older than 10 yr or who have an initial leukocyte count of >50,000/µL are considered to be high risk. Additional characteristics that adversely affect outcome include T-cell immunophenotype or a slow response to initial therapy. Chromosomal abnormalities, including hypodiploidy, the Philadelphia chromosome, and KMT2A (MLL) gene rearrangements, portend a poorer outcome. Other mutations, such as in the IKZF1 gene, have been shown to be associated with a poor prognosis and may become important in treatment algorithms in the future. More favorable characteristics include a rapid response to therapy, hyperdiploidy, trisomy of specific chromosomes (4, 10, and 17), and rearrangements of the ETV6-RUNX1 (formerly TEL-AML1 ) genes.

The outcome for patients at higher risk can be improved by administration of more intensive therapy despite the greater toxicity of such therapy. Infants with ALL, along with patients who present with specific chromosomal abnormalities, such as t(4;11), have an even higher risk of relapse despite intensive therapy. However, the poor outcome of Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL with t(9;22) has been dramatically changed by the addition of imatinib to an intensive chemotherapy backbone. Imatinib is an agent specifically designed to inhibit the BCR-ABL kinase resulting from the translocation. With this approach, the event-free survival has improved from 30% to 70%. Clinical trials demonstrate that the prognosis for patients with a slower response to initial therapy may be improved by therapy that is more intensive than the therapy considered necessary for patients who respond more rapidly.

Most children with ALL are treated in clinical trials conducted by national or international cooperative groups. Standard treatment involves chemotherapy for 2-3 yr, and most achieve remission at the end of the induction phase. Patients in clinical remission can have MRD that can only be detected with specific molecular probes to translocations and other DNA markers contained in leukemic cells or specialized flow cytometry. MRD can be quantitative and can provide an estimate of the burden of leukemic cells present in the marrow. Higher levels of MRD present at the end of induction suggest a poorer prognosis and higher risk of subsequent relapse. MRD of >0.01% on the marrow on day 29 of induction is a significant risk factor for shorter event-free survival for all risk categories, compared with patients with negative MRD. Therapy for ALL intensifies treatment in patients with evidence of MRD at the end of induction.

Initial therapy, termed remission induction , is designed to eradicate the leukemic cells from the bone marrow. During this phase, therapy is given for 4 wk and consists of vincristine weekly, a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone or prednisone, and usually a single dose of a long-acting, pegylated asparaginase preparation. Patients at higher risk also receive daunomycin at weekly intervals. With this approach, 98% of patients are in remission, as defined by <5% blasts in the marrow and a return of neutrophil and platelet counts to near-normal levels after 4-5 wk of treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy is always given at the start of treatment and at least once more during induction.

The second phase of treatment, consolidation , focuses on intensive CNS therapy in combination with continued intensive systemic therapy in an effort to prevent later CNS relapses. Intrathecal chemotherapy is given repeatedly by LP. The likelihood of later CNS relapse is thereby reduced to <5%, from historical incidence as high as 60%. A small percentage of patients with features that predict a high risk of CNS relapse may receive irradiation to the brain in later phases of therapy. This includes patients who at diagnosis have lymphoblasts in the CSF and either an elevated CSF leukocyte count or physical signs of CNS leukemia, such as cranial nerve palsy.

Subsequently, many regimens provide 14-28 wk of therapy, with the drugs and schedules used varying depending on the risk group of the patient. This period of treatment is often termed intensification and includes phases of aggressive treatment (delayed intensification ) as well as relatively nontoxic phases of treatment (interim maintenance ). Multiagent chemotherapy, including such medications as cytarabine, methotrexate, asparaginase, and vincristine, is used during these phases to eradicate residual disease.

Finally, patients enter the maintenance phase of therapy, which lasts for 2-3 yr, depending on the protocol used. Patients are given daily mercaptopurine and weekly oral methotrexate, usually with intermittent doses of vincristine and a corticosteroid.

A small number of patients with particularly poor prognostic features, such as those with induction failure or extreme hypodiploidy, may undergo bone marrow transplantation during the first remission.

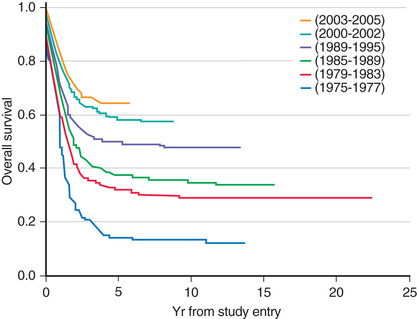

Adolescents and young adults with ALL have an inferior prognosis compared to children <15 yr old. They often have adverse prognostic factors and require more intensive therapy. Patients in this age-group have a superior outcome when treated with pediatric rather than adult treatment protocols (Fig. 522.5 ). Although the explanation for these findings may be multifactorial, it is important that these patients be treated with pediatric treatment protocols, ideally in a pediatric cancer center.

Genetic polymorphisms of enzymes important in drug metabolism may impact both the efficacy and the toxicity of chemotherapeutic medications. Pharmacogenetic testing of the thiopurine S -methyltransferase (TPMT) gene, which encodes one of the metabolizing enzymes of mercaptopurine, can identify patients who are wild type (normal TPMT enzyme activity), heterozygous (slightly decreased TPMT enzyme activity), or homozygous (low or absent enzyme activity). Decreased TPMT enzyme activity results in accumulation of a toxic metabolite of mercaptopurine and severe myelosuppression, requiring dose reductions of the chemotherapy (see Chapter 73 ). In the future, treatment also may be stratified by gene expression profiles of leukemic cells. In particular, gene expression arrays induced by exposure to a chemotherapeutic agent can predict which patients have drug-resistant ALL.

Treatment of Relapse

The major impediment to a successful outcome is relapse of the disease. Outcomes remain poor among those who relapse, with the most important prognostic indicators being time from diagnosis and site of relapsed disease. In addition, other factors, such as immunophenotype (T-ALL worse than B-ALL) and age at initial diagnosis, have prognostic significance.

Relapse occurs in the bone marrow in 15–20% of patients with ALL and carries the most serious implications, especially if it occurs during or shortly after completion of therapy. Intensive chemotherapy with agents not previously used in the patient followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation can result in long-term survival for some patients with bone marrow relapse (see Chapter 161 ). Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell technology will have an increasing role in the treatment of patients who have experienced a relapse of ALL (see Chapter 521 ).

The incidence of CNS relapse has decreased to <5% since introduction of preventive CNS therapy. CNS relapse may be discovered at a routine LP in the asymptomatic patient. Symptomatic patients with relapse in the CNS usually present with signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure and can present with isolated cranial nerve palsies. The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstrating the presence of leukemic cells in the CSF. The treatment includes intrathecal medication and cranial or craniospinal irradiation. Systemic chemotherapy also must be used, because these patients are at high risk for subsequent bone marrow relapse. Most patients with leukemic relapse confined to the CNS do well, especially those in whom the CNS relapse occurs longer than 18 mo after initiation of chemotherapy.

Testicular relapse occurs in <2% of boys with ALL, usually after completion of therapy. Such relapse occurs as painless swelling of 1 or both testes. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy of the affected testis. Treatment includes systemic chemotherapy and possibly local irradiation. A high proportion of boys with a testicular relapse can be successfully retreated, and the survival rate of these patients is good.

The most current information on treatment of childhood ALL is available in the PDQ (Physician Data Query) on the NCI website (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/childALL/healthprofessional/ ).

Supportive Care

Close attention to the medical supportive care needs of the patients is essential in successfully administering aggressive chemotherapeutic programs. Patients with high WBC counts are especially prone to tumor lysis syndrome as therapy is initiated. The kidney failure associated with very high levels of serum uric acid can be prevented or treated with allopurinol or urate oxidase. Chemotherapy often produces severe myelosuppression, which can require erythrocyte and platelet transfusion and always requires a high index of suspicion and aggressive empirical antimicrobial therapy for sepsis in febrile children with neutropenia. Patients must receive prophylactic treatment for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia during chemotherapy and for several months after completing treatment.

The successful therapy of ALL is a direct result of intensive and often toxic treatment. However, such intensive therapy can incur substantial academic, developmental, and psychosocial costs for children with ALL and considerable financial costs and stress for their families. Both long-term and acute toxicity effects can occur. An array of cancer care professionals with training and experience in addressing the myriad of problems that can arise is essential to minimize the complications and achieve an optimal outcome.

Prognosis

Improvements in therapy and risk stratification have resulted in significant increases in survival rates, with current data showing overall 5 yr survival of approximately 90% (Fig. 522.6 ). However, survivors are more likely to experience significant chronic medical conditions compared to siblings, including musculoskeletal, cardiac, and neurologic conditions. Overall, long-term management following ALL should be conducted in a clinic where children and adolescents can be followed by a variety of specialists to address the challenges of these unique patients.

Bibliography

Aoki T, Koh K, Arakawa Y, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome during chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastomic leukemia. J Pediatr . 2017;180:284.

Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med . 2016;374(9):833–842.

Asselin BL, Devidas M, Chen L, et al. Cardioprotection and safety of dexrazoxane in patients treated for newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia or advanced-stage lymphoblastic non-hodgkin lymphoma: a report of the Children's oncology group randomized trial pediatric oncology group 9404. J Clin Oncol . 2015;34(6):854–862.

Bhatia S. Long-term complications of therapeutic exposures in childhood: lessons learned from childhood cancer survivors. Pediatrics . 2012;130:1141–1143.

Bhojwani D, Pui CH. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol . 2013;14:e205–e217.

Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children's oncology group study. Blood . 2008;111:5477–5485.

Brix N, Rosthøj S, Herlin T, Hasle H. Arthritis as presenting manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children. Arch Dis Child . 2015;100:821–825.

Carroll WL, Raetz EA. Clinical and laboratory biology of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr . 2012;160:10–18.

Clarke RT, Van den Bruel A, Bankhead C, et al. Clinical presentation of childhood leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child . 2016;101:894–901.

Claudio J, Rocha C, Cheng C, et al. Pharmacogenetics of outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood . 2005;105:4752–4758.

Diller L. Adult primary care after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2011;365:1417–1424.

Diouf B, Crews KR, Lew G, et al. Association of an inherited genetic variant with vincristine-related peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA . 2015;313(8):815–823.

Greaves M. In utero origins of childhood leukaemia. Early Hum Dev . 2005;81:123–129.

Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2013;368(16):1509–1518.

Guest EM, Stam RW. Updates in the biology and therapy for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:20–26.

Hijiya N, Hudson MM, Lensing S, et al. Cumulative incidence of secondary neoplasms as a first event after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA . 2007;297:1207–1215.

Hochberg J, Khaled S, Forman SJ, et al. Criteria for and outcomes of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant in children, adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first complete remission. Br J Haematol . 2013;161:27–42.

Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the Children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol . 2012;30:1663–1669.

Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med . 2015;373:1541–1552.

Jackson HJ, Rafiq S, Brentjens RJ. Driving CAR T-cells forward. Nature . 2016;13:370–383.

Jacola LM, Edelstein K, Liu W, et al. Cognitive, behaviour, and academic functioning in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Lancet Psychiatry . 2016;3:965–972.

Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamiein versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(8):740–752.

Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet . 2015;385:517–528.

Leung W, Pui CH, Coustan-Smith E, et al. Detectable minimal residual disease before hematopoietic cell transplantation is prognostic but does not preclude cure for children with very-high-risk leukemia. Blood . 2012;120(2):468–472.

Levine RL. Inherited susceptibility to pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet . 2009;41:957–958.

Maude SL. Future directions in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:27–33.

Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N J Med . 2014;371:1507–1517.

Milano F, Gooley T, Wood B, et al. Cord-blood transplantation in patients with minimal residual disease. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(10):944–952.

Mullighan CG. Genomic characterization of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol . 2013;50:314–324.

Mullighan CG, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:470–480.

Patel SR, Ortin M, Cohen BJ, et al. Revaccination of children after completion of standard chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:635–642.

Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:2730–2740.

Pui CH, Carroll WL, Meshinchi S, et al. Biology, risk stratification, and therapy of pediatric acute leukemias: an update. J Clin Oncol . 2011;29:551–565.

Pui CH, Mullighan CG, Evans WE, et al. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: where are we going and how do we get there? Blood . 2012;120:1165–1174.

Pui CH, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: progress through collaboration. J Clin Oncol . 2015;33:2938–2948.

Ram R, Wolach O, Vidal L, et al. Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia have a better outcome when treated with pediatric-inspired regimens: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol . 2012;87:472–478.

Schafer ES, Hunger SP. Optimal therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Clin Oncol . 2011;8:417–424.

Schrappe M, Hunger SP, Pui CH, et al. Outcomes after induction failure in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2012;366:1371–1381.

Schultz KR, Carroll A, Heerema NA. Long-term follow-up of imatinib in pediatric philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Children's oncology group study AALL0031. Leukemia . 2014;28:1467–1471.

Shaw PJ, Kan F, Ahn KW, et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood . 2010;116(19):4007–4015.

Siegel DA, Henley J, Li J, et al. Rates and trends of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia—United States, 2001–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2017;66(36):950–954.

Stanulla M, Schaeffeler E, Flohr T, et al. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) genotype and early treatment response to mercaptopurine in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA . 2005;293:1485–1489.

Stock W, La M, Sanford B, et al. What determines the outcomes for adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on cooperative group protocols? A comparison of Children's cancer group and cancer and leukemia group B studies. Blood . 2008;112:1646–1654.

Temming P, Jenney MEM. The neurodevelopmental sequelae of childhood leukemia and its treatment. Arch Dis Child . 2010;95:936–940.

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

Erika Friehling, David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, A. Kim Ritchey

Epidemiology

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML ) accounts for 11% of the cases of childhood leukemia in the United States; it is diagnosed in approximately 370 children annually. The relative frequency of AML increases in adolescence, representing 36% of cases of leukemia in 15-19 yr olds. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a subtype that is more common in certain regions of the world, but the incidence of the other types is generally uniform. Several chromosomal abnormalities associated with AML have been identified, but no predisposing genetic or environmental factors can be identified in most patients (see Table 522.1 ). Nonetheless, a number of risk factors have been identified, including ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., alkylating agents, epipodophyllotoxin), organic solvents, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and certain syndromes: Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, Kostmann syndrome, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Cellular Classification

The characteristic feature of AML is that >20% of bone marrow cells on bone marrow aspiration or biopsy touch preparations constitute a fairly homogeneous population of blast cells, with features similar to those that characterize early differentiation states of the myeloid-monocyte-megakaryocyte series of blood cells. Current practice requires the use of flow cytometry to identify cell surface antigens and use of chromosomal and molecular genetic techniques for additional diagnostic precision and to aid the choice of therapy. The WHO has proposed a new classification system that incorporates morphology, chromosome abnormalities, and specific gene mutations. This system provides significant biologic and prognostic information (Table 522.3 ).

Table 522.3

WHO Classification of Acute Myeloid Neoplasms

AML, Acute myelogenous leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Adapted from Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al: The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia, Blood 127:2391–2405, 2016.

Clinical Manifestations

The production of symptoms and signs of AML is a result of replacement of bone marrow by malignant cells and caused by secondary bone marrow failure. Patients with AML can present with any or all of the findings associated with marrow failure in ALL. In addition, patients with AML present with signs and symptoms that are uncommon in ALL, including subcutaneous nodules or “blueberry muffin” lesions (especially in infants), infiltration of the gingiva (especially in monocytic subtypes), signs and laboratory findings of disseminated intravascular coagulation (especially indicative of APL), and discrete masses, known as chloromas or granulocytic sarcomas . These masses can occur in the absence of apparent bone marrow involvement and typically are associated with a t(8;21) translocation. Chloromas also may be seen in the orbit and epidural space.

Diagnosis

Analysis of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy specimens of patients with AML typically reveals the features of a hypercellular marrow consisting of a monotonous pattern of cells. Flow cytometry and special stains assist in identifying myeloperoxidase-containing cells, thus confirming both the myelogenous origin of the leukemia and the diagnosis. Some chromosomal abnormalities and molecular genetic markers are characteristic of specific subtypes of disease (Table 522.4 ).

Table 522.4

Prognostic Implications of Common Chromosomal Abnormalities in Pediatric Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

| CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITY | GENETIC ALTERATION | USUAL MORPHOLOGY | PROGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|

| t(8;21) | RUNX1-RUNX1T1 | Myeloblasts with differentiation | Favorable |

| inv(16) | CBFB-MYHII | Myeloblasts plus abnormal eosinophils with dysplastic basophilic granules | Favorable |

| t(15;17) | PML-RARA | Promyelocytic | Favorable |

| 11q23 abnormalities | KMT2A(MLL) rearrangements | Monocytic | Unfavorable |

| FLT3 mutation | FLT3 -ITD | Any | Unfavorable |

| del(7q), −7 | Unknown | Myeloblasts without differentiation | Unfavorable |

Adapted from Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, et al, editors: Nathan and Oski's hematology of infancy and childhood , ed 6, Philadelphia, 2003, Saunders, p 1177.

Prognosis and Treatment

Aggressive multiagent chemotherapy is successful in inducing remission in approximately 85–90% of patients. Survival has increased dramatically since the 1970s, when only 15% of newly diagnosed patients survived, compared to a current survival rate of 60–70% with modern therapy (Fig. 522.7 ). Various induction chemotherapy regimens exist, typically including an anthracycline in combination with high-dose cytarabine. Targeting therapy to genetic markers may be beneficial (see Table 522.4 ). Up to 5% of patients die of either infection or bleeding before a remission can be achieved. Postremission therapy is chosen based on a combination of cytogenetic and molecular markers of the leukemia as well as the response to induction chemotherapy (MRD assessment). For selected patients with favorable prognostic features [t(8;21); t(15;17); inv(16)] and improved outcome with chemotherapy alone, stem cell transplantation is recommended only after a relapse. However, patients with unfavorable prognostic features (e.g., monosomies 7 and 5, 5q−, and 11q23 abnormalities) who have inferior outcome with chemotherapy might benefit from stem cell transplant in first remission. With improvements in supportive care, there is no longer a substantial difference in mortality when comparing matched-related stem cell transplants to matched-unrelated stem cell transplants for AML.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia, characterized by a gene rearrangement involving the retinoic acid receptor [t(15;17); PML-RARA], is very responsive to all-trans -retinoic acid (ATRA, tretinoin) combined with anthracyclines and cytarabine. The success of this therapy makes marrow transplantation in first remission unnecessary for patients with this disease. Arsenic trioxide is an effective noncytotoxic therapy for APL. Data from trials in adults show promising results with the use of combined ATRA/arsenic without cytotoxic drugs as initial therapy for APL and would support a new trial of this regimen in children.

Increased supportive care is needed in patients with AML because the intensive therapy they receive produces prolonged bone marrow suppression with a very high incidence of serious infections, especially viridans streptococcal sepsis and fungal infection. These patients may require prolonged hospitalization, filgrastim (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor), and prophylactic antimicrobials.

The most current information on treatment of AML is available in the PDQ (Physician Data Query) on the NCI website (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/childAML/healthprofessional/ ).

Bibliography

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the world health organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood . 2016;127:2391–2405.

De Thé H. Lessons taught by acute promyelocytic leukemia cure. Lancet . 2015;386:247–248.

Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yai X, et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2009;361:1249–1259.

Gamis AS, Alonzo TA, Perentesis JP, et al. On behalf of the COG acute myeloid leukemia committee (2013): Children's oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2013;60:964–971.

Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, et al. Assessment of minimal residual disease in standard-rick AML. N Engl J Med . 2016;374(5):422–432.

Kaspers GJ. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther . 2012;12:405–413.

Lo-Coco F, Avvisati G, Vignetti M. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2013;369:111–121.

Niewerth D, Creutzig U, Bierings MB, et al. A review on allogenic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood . 2010;30:2205–2214.

Patel JP, Gönen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2012;366(12):1079–1089.

Rizzari C, Cazzaniga G, Coliva T, et al. Predictive factors of relapse and survival in childhood acute myeloid leukemia: role of minimal residual disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther . 2011;11:1391–1401.

Ross ME, Mahfouz R, Onciu M, et al. Gene expression profiling of pediatric acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood . 2004;104:3679–3687.

Schlenk RF, Dohner K, Krauter J, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2008;358:1909–1918.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissue . ed 4. International Agency for Research in Cancer: Lyons; 2008.

Tarlock K, Meshinchi S. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: biology and therapeutic implications of genomic variants. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2015;62:75–93.

Zwaan CM, Kolb EA, Reinhardt D, et al. Collaborative efforts driving progress in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol . 2015;33:2949–2962.

Down Syndrome and Acute Leukemia and Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder

David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, Erika Friehling, A. Kim Ritchey

Acute leukemia occurs about 15-20 times more frequently in children with Down syndrome than in the general population (see Chapters 98.2 and 519 ). The ratio of ALL to AML in patients with Down syndrome is the same as that in the general population. The exception is during the 1st 3 yr of life, when AML is more common. In children with Down syndrome who have ALL, the expected outcome of treatment is slightly inferior to that for other children, a difference that can be partially explained by a lack of good prognostic characteristics, such as ETV6-RUNX1 and trisomies, as well as genetic abnormalities that are associated with an inferior prognosis, such as IKZF1 . Patients with Down syndrome demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to methotrexate and other antimetabolites, resulting in substantial toxicity if standard doses are administered. However, in the case of AML, patients with Down syndrome have much better outcomes than non–Down syndrome children, with a >80% long-term survival rate. After induction therapy, these patients receive therapy that is less intensive to decrease toxicity while maintaining excellent cure rates.

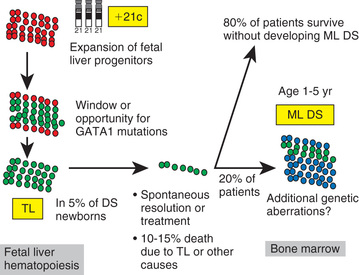

Approximately 10% of neonates with Down syndrome develop a transient leukemia or myeloproliferative disorder characterized by high leukocyte counts, blast cells in the peripheral blood, and associated anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. These features usually resolve within the 1st 3 mo of life. Although these neonates can require temporary transfusion support, they do not require chemotherapy unless there is evidence of life-threatening complications. However, patients who have Down syndrome and who develop this transient myeloproliferative disorder require close follow-up, because 20–30% will develop typical leukemia (often acute megakaryocytic leukemia ) by age 3 yr (mean onset, 16 mo). GATA1 mutations (a transcription factor that controls megakaryopoiesis) are present in blasts from patients with Down syndrome who have transient myeloproliferative disease and also in those with leukemia (Fig. 522.8 ).

Bibliography

Bercovich D, Ganmore I, Scott LM, et al. Mutations of JAK2 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemias associated with Down's syndrome. Lancet . 2008;372:1484–1492.

Cushing T, Clericuzio C, Wilson C, et al. Risk for leukemia in infants without down syndrome who have transient myeloproliferative disorder. J Pediatr . 2006;148:687–689.

Iwashita N, Sadahira C, Yuza Y, et al. Vesiculopustular eruption in neonate with trisomy 21 and transient myeloproliferative disorder. J Pediatr . 2013;162(3):643–644.

Izraeli S. The acute lymphoblastic leukemia of down syndrome: genetics and pathogenesis. Eur J Med Genet . 2016;59:158–161.

Maloney KW, Taub JW, Ravindranath Y, et al. Down syndrome: preleukemia and leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2015;62:121–137.

Sorrell AD, Alonzo TA, Hilden JM, et al. Favorable survival maintained in children who have myeloid leukemia associated with down syndrome using reduced-dose chemotherapy on Children's oncology group trial a2971: a report from the Children's oncology group. Cancer . 2012;118:4806–4814.

Xavier AC, Ge Y, Taub J. Unique clinical and biological features of leukemia in down syndrome children. Expert Rev Hematol . 2010;3:175–186.

Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, Erika Friehling, A. Kim Ritchey

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML ) is a clonal disorder of the hematopoietic tissue that accounts for 2–3% of all cases of childhood leukemia. Approximately 99% of the cases are characterized by a specific translocation, t(9;22)(q34;q11), known as the Philadelphia chromosome , resulting in a BCR-ABL fusion protein.

The presenting symptoms of CML are nonspecific and can include fever, fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia. Splenomegaly also may be present, resulting in pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The diagnosis is suggested by a high WBC count with myeloid cells at all stages of differentiation in the peripheral blood and bone marrow. It is confirmed by cytogenetic and molecular studies that demonstrate the presence of the characteristic Philadelphia chromosome and the BCR-ABL gene rearrangement. This translocation, although characteristic of CML, is also found in a small percentage of patients with ALL.

The disease is characterized by an initial chronic phase in which the malignant clone produces an elevated leukocyte count with a predominance of mature forms but with increased numbers of immature granulocytes. In addition to leukocytosis, blood counts can reveal mild anemia and thrombocytosis. Typically, the chronic phase terminates 3-4 yr after onset, when the CML moves into the accelerated or “blast crisis” phase . At this point, the blood counts rise dramatically, and the clinical picture is indistinguishable from acute leukemia. Additional manifestations can occur, including neurologic symptoms from hyperleukocytosis, which causes increased blood viscosity with decreased CNS perfusion.

Imatinib (Gleevec), an agent designed specifically to inhibit the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, has been used in adults and children and has shown an ability to produce major cytogenetic responses in >70% of patients (see Table 522.1 ). Experience in children suggests it can be used safely with results comparable to those seen in adults. Second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as dasatinib and nilotinib , have improved remission rates in adults and are now included in the first-line therapy in that population. While waiting for a response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, disabling or threatening signs and symptoms of CML can be controlled during the chronic phase with hydroxyurea, which gradually returns the leukocyte count to normal. Treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor is the current standard for pediatric CML. While not considered curative at this time, prolonged responses can be seen and studies in adults have shown that in select cases, treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor can be stopped. The role of potentially curative HLA-matched family donor stem cell transplant in management of pediatric CML is debated.

Bibliography

Champagne MA, Fu CH, Chang M, et al. Higher dose imatinib for children with de novo chronic phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: a report from the Children's oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2011;57:56–62.

Hijiya N, Millot F, Suttorp M. Chronic myeloid leukemia in children: clinical findings, management, and unanswered questions. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2015;62:107–119.

Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL. N Engl J Med . 2006;354:2542–2550.

Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2010;362(24):2260–2270.

Mahon FX, Réa D, Guilhot J, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre stop imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol . 2010;11:1029–1035.

Saglio G, Kim DN, Issaragrisil S, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2010;362(24):2251–2256.

Suttorp M, Eckardt L, Tauer JT, et al. Management of chronic myeloid leukemia in childhood. Curr Hematol Malig Rep . 2012;7:116–124.

Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemias. N Engl J Med . 2006;354:2531–2540.

Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, Erika Friehling, A. Kim Ritchey

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML ), formerly termed juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia, is a clonal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells that typically affects children <2 yr old. JMML is rare, constituting <1% of all cases of childhood leukemia. Patients with this disease do not have the Philadelphia chromosome characteristic of CML. Patients with JMML present with rashes, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hemorrhagic manifestations. Analysis of the peripheral blood often shows an elevated leukocyte count with increased monocytes, thrombocytopenia, and anemia with the presence of erythroblasts. The bone marrow shows a myelodysplastic pattern, with blasts accounting for <20% of cells. Most patients with JMML have been found to have mutations that lead to activation of the RAS oncogene pathway, including NRAS , NF1 , and PTPN11 . Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome have a predilection for this type of leukemia, since they have germline mutations involved in RAS signaling. JMML in the setting of Noonan syndrome is unique, with most patients having a spontaneous resolution. However, for most patients with JMML, stem cell transplantation offers the best opportunity for cure, but outcomes are still poor.

Bibliography

Loh ML. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol . 2011;152:677–687.

Loh ML, Mullighan CG. Advances in the genetics of high-risk childhood B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: implications for therapy. Clin Cancer Res . 2012;18:2754–2767.

Niemeyer CM, Kang MW, Shin DH, et al. Germline CBL mutations cause developmental abnormalities and predispose to juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Nat Genet . 2010;42:794–800.

Woods WG, Barnard DR, Alonzo TA, et al. Prospective study of 90 children requiring treatment for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol . 2002;20:434–440.

Yoshimi A, Kojima S, Hirano N. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management considerations. Paediatr Drugs . 2010;12:11–21.

Infant Leukemia

David G. Tubergen, Archie Bleyer, Erika Friehling, A. Kim Ritchey

Approximately 2% of cases of leukemia during childhood occur before age 1 yr. In contrast to the situation in older children, the ratio of ALL in infants to AML is 2 : 1. Leukemic clones have been noted in cord blood at birth before symptoms appear, and in one case the same clone was noted in maternal cells (maternal-to-fetal transmission). Chromosome translocations can also occur in utero during fetal hematopoiesis, leading to malignant clone formation.

Several unique biologic features and a particularly poor prognosis are characteristic of ALL during infancy. More than 80% of the cases demonstrate rearrangements of the KMT2A (MLL) gene, found at the site of the 11q23 band translocation, the majority of which are the t(4;11). This subset of patients largely accounts for the very high relapse rate. These patients often present with hyperleukocytosis and extensive tissue infiltration producing organomegaly, including CNS disease. Subcutaneous nodules, known as leukemia cutis , and tachypnea caused by diffuse pulmonary infiltration by leukemic cells are observed more often in infants than in older children. The leukemic cell morphology is usually that of large, irregular lymphoblasts, with a phenotype negative for the CD10 (common ALL antigen) marker (pro-B), unlike most older children with B-ALL, who are CD10+ .

Very intensive chemotherapy programs, including stem cell transplantation, are being explored in infants with KMT2A (MLL) gene rearrangements, but none has yet proved satisfactory. Infants with leukemia who lack the 11q23 rearrangements have a prognosis similar to that of older children with ALL.

Infants with AML often present with CNS or skin involvement and have a subtype known as acute myelomonocytic leukemia. The treatment may be the same as that for older children with AML, with similar outcome. Meticulous supportive care is necessary because of the young age and aggressive therapy needed in these patients.

Bibliography

Greaves M. In utero origins of childhood leukaemia. Early Hum Dev . 2005;81:123–129.

Guest EM, Stam RW. Updates in the biology and therapy for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:20–26.

Hunger SP, Loh KM, Baker KS, et al. Controversies of and unique issues in hematopoietic cell transplantation for infant leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant . 2009;15:79–83.

Isoda T, Ford AM, Tomizawa D, et al. Immunologically silent cancer clone transmission from mother to offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2009;106:17882–17885.

Pieters R, Schrappe M, De Lorenzo P, et al. A treatment protocol for infants younger than 1 year with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Interfant-99): an observational study and a multicentre randomized trial. Lancet . 2007;370:240–250.