Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Eveline Y. Wu, C. Egla Rabinovich

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common rheumatic disease in children and one of the more common chronic illnesses of childhood. JIA represents a heterogeneous group of disorders sharing the clinical manifestation of arthritis. The etiology and pathogenesis of JIA are largely unknown, and the genetic component is complex, making clear distinction among various subtypes difficult. As a result, several classification schemes exist, each with its own limitations. The former classification of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) uses the term juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and categorizes the disease into 3 onset types (Table 180.1 ). Attempting to standardize nomenclature, the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) proposed a different classification using the term juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Table 180.2 ), inclusive of all subtypes of chronic juvenile arthritis. We refer to the ILAR classification criteria; see Chapter 181 for enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) and psoriatic JIA (Tables 180.3 and 180.4 ).

Table 180.2

International League of Associations for Rheumatology Classification of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

| CATEGORY | DEFINITION | EXCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic JIA |

Arthritis in ≥1 joint with, or preceded by, fever of at least 2 wk in duration that is documented to be daily (quotidian* ) for at least 3 days and accompanied by ≥1 of the following: 1. Evanescent (nonfixed) erythematous rash 2. Generalized lymph node enlargement 3. Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly or both 4. Serositis † |

a. Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in patient or first-degree relative b. Arthritis in an HLA-B27–positive boy beginning after 6th birthday c. Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, Reiter syndrome, or acute anterior uveitis, or history of 1 of these disorders in first-degree relative d. Presence of IgM RF on at least 2 occasions at least 3 mo apart |

| Oligoarthritis |

Arthritis affecting 1-4 joints during 1st 6 mo of disease; 2 subcategories are recognized: |

|

| Polyarthritis (RF negative) | Arthritis affecting ≥5 joints during 1st 6 mo of disease; a test for RF is negative | a, b, c, d, e |

| Polyarthritis (RF positive) | Arthritis affecting ≥5 joints during 1st 6 mo of disease; ≥2 tests for RF at least 3 mo apart during 1st 6 mo of disease are positive | a, b, c, e |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Arthritis and psoriasis, or arthritis and at least 2 of the following: | b, c, d, e |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | Arthritis and enthesitis, ‖ or arthritis or enthesitis with at least 2 of the following: | a, d, e |

|

1. Presence of or history of sacroiliac joint tenderness or inflammatory lumbosacral pain, or both ¶ 2. Presence of HLA-B27 antigen 3. Onset of arthritis in a male >6 yr old 4. Acute (symptomatic) anterior uveitis 5. History of ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, Reiter syndrome, or acute anterior uveitis in first-degree relative |

||

| Undifferentiated arthritis | Arthritis that fulfills criteria in no category or in ≥2 of the above categories. |

* Quotidian fever is defined as a fever that rises to 39°C (102.2°F) once daily and returns to 37°C (98.6°F) between fever peaks.

† Serositis refers to pericarditis, pleuritis, or peritonitis, or some combination of the 3.

‡ Dactylitis is swelling of ≥1 digit(s), usually in an asymmetric distribution, that extends beyond the joint margin.

§ A minimum of 2 pits on any 1 or more nails at any time.

‖ Enthesitis is defined as tenderness at the insertion of a tendon, ligament, joint capsule, or fascia to bone.

¶ Inflammatory lumbosacral pain refers to lumbosacral pain at rest with morning stiffness that improves on movement.

IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; RF, rheumatoid factor.

From Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, editors: Kelley's textbook of rheumatology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Saunders.

Table 180.3

Characteristics of ACR and ILAR Classifications of Childhood Chronic Arthritis

| PARAMETER | ACR (1977) | ILAR (1997) |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) |

| Minimum duration | ≥6 wk | ≥6 wk |

| Age at onset | <16 yr | <16 yr |

| ≤4 joints in 1st 6 mo after presentation | Pauciarticular |

Oligoarthritis: |

| >4 joints in 1st 6 mo after presentation | Polyarticular |

Polyarthritis, RF negative Polyarthritis, RF positive |

| Fever, rash, arthritis | Systemic onset | Systemic |

| Other categories included | Exclusion of other forms |

Psoriatic arthritis Enthesitis-related arthritis Undifferentiated: |

| Inclusion of psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, ankylosing spondylitis | No (see Chapter 181 ) | Yes |

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ILAR, International League of Associations for Rheumatology; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Table 180.4

Overview of Main Features of Subtypes of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

| ILAR SUBTYPE | PEAK AGE at ONSET (yr) | FEMALE:MALE RATIO | % of ALL JIA CASES | ARTHRITIS PATTERN | EXTRAARTICULAR FEATURES | LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS | NOTES ON THERAPY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic arthritis | 1-5 | 1 : 1 | 5-15 | Polyarticular, often affecting knees, wrists, and ankles; also fingers, neck, and hips | Daily fever; evanescent rash; pericarditis; pleuritis | Anemia; WBC ↑↑; ESR ↑↑; CRP ↑↑; ferritin ↑; platelets ↑↑ (normal or ↓ in MAS) | Less responsive to standard treatment with MTX and anti-TNF agents; consider IL-1 or IL-6 inhibitors in resistant cases or as first-line therapy |

| Oligoarthritis | 2-4 | 3 : 1 | 40-50 (but ethnic variation) | Knees ++; ankles, fingers + | Uveitis in 30% of cases | ANA positive in 60%; other test results usually normal; may have mildly ↑ ESR/CRP | NSAIDs and intraarticular corticosteroids; MTX occasionally required |

| Polyarthritis: | |||||||

| RF negative | 2-4 and 10-14 | 3 : 1 and 10 : 1 | 20-35 | Symmetric or asymmetric; small and large joints; cervical spine; temporomandibular joint | Uveitis in 10% | ANA positive in 40%; RF negative; ESR ↑ or ↑↑; CRP ↑ or normal; mild anemia | Standard therapy with MTX and NSAIDs; then, if nonresponsive, anti-TNF agents or other biologics, including abatacept, indicated as first-line therapy |

| RF positive | 9-12 | 9 : 1 | <10 | Aggressive symmetric polyarthritis | Rheumatoid nodules in 10%; low-grade fever | RF positive; ESR ↑↑; CRP ↑/normal; mild anemia | Long-term remission unlikely; early aggressive therapy is warranted |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2-4 and 9-11 | 2 : 1 | 5-10 | Asymmetric arthritis of small or medium-sized joints | Uveitis in 10%; psoriasis in 50% | ANA positive in 50%; ESR ↑; CRP ↑ or normal; mild anemia | NSAIDs and intraarticular corticosteroids; MTX, anti-TNF agents |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | 9-12 | 1 : 7 | 5-10 | Predominantly lower limb joints affected; sometimes axial skeleton (but less than in adult, ankylosing spondylitis) | Acute anterior uveitis; association with reactive arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease | 80% of patients positive for HLA-B27 | NSAIDs and intraarticular corticosteroids; consider sulfasalazine as alternative to MTX; anti-TNF agents |

ILAR, International League of Associations for Rheumatology; ANA, antinuclear antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; MTX, methotrexate; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; RF, rheumatoid factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; WBC, white blood cell count.

From Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, editors: Kelley's textbook of rheumatology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Saunders.

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence of JIA ranges from 0.8-22.6 per 100,000 children per year, with prevalence ranges from 7-401 per 100,000. These wide-ranging numbers reflect population differences, particularly environmental exposure and immunogenetic susceptibility, along with variations in diagnostic criteria, difficulty in case ascertainment, and lack of population-based data. An estimated 300,000 U.S. children have arthritis, including 100,000 with a form of JIA. Oligoarthritis is the most common subtype (40–50%), followed by polyarthritis (25–30%) and systemic JIA (5–15%) (see Table 180.4 ). There is no sex predominance in systemic JIA (sJIA ), but more girls than boys are affected in both oligoarticular (3 : 1) and polyarticular (5 : 1) JIA. The peak age at onset is 2-4 yr for oligoarticular disease. Age of onset has a bimodal distribution in polyarthritis, with peaks at 2-4 yr and 10-14 yr. sJIA occurs throughout childhood, with a peak at 1-5 yr.

Etiology

The etiology and pathogenesis of JIA are not completely understood, although both immunogenetic susceptibility and an external trigger are considered necessary. Twin and family studies suggest a substantial role for genetic factors. JIA is a complex genetic trait in which multiple genes may affect disease susceptibility. Variants in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II regions have indisputably been associated with different JIA subtypes. Non-HLA candidate loci are also associated with JIA, including polymorphisms in the genes encoding protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor 22 (PTPN22), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, macrophage inhibitory factor, interleukin (IL)-6 and its receptor, and IL-1α. Possible nongenetic triggers include bacterial and viral infections, enhanced immune responses to bacterial or mycobacterial heat shock proteins, abnormal reproductive hormone levels, and joint trauma.

Pathogenesis

JIA is an autoimmune disease associated with alterations in both humoral and cell-mediated immunity. T lymphocytes have a central role, releasing proinflammatory cytokines favoring a type 1 helper T lymphocyte response. Studies of T-cell receptor expression confirm recruitment of T lymphocytes specific for synovial non–self-antigens. B-cell activation, immune complex formation, and complement activation also promote inflammation. Inheritance of specific cytokine alleles may predispose to upregulation of inflammatory networks, resulting in systemic disease or more severe articular disease.

Systemic JIA is characterized by dysregulation of the innate immune system with a lack of autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies. It therefore may be more accurately classified as an autoinflammatory disorder , more like familial Mediterranean fever, than the other subtypes of JIA. This theory is also supported by work demonstrating similar expression patterns of a phagocytic protein (S100A12) in sJIA and familial Mediterranean fever, as well as the same marked responsiveness to IL-1 inhibitors.

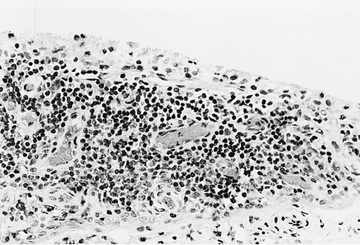

All these immunologic abnormalities cause inflammatory synovitis, characterized pathologically by villous hypertrophy and hyperplasia with hyperemia and edema of the synovial tissue. Vascular endothelial hyperplasia is prominent and is characterized by infiltration of mononuclear and plasma cells with a predominance of T lymphocytes (Fig. 180.1 ). Advanced and uncontrolled disease leads to pannus formation and progressive erosion of articular cartilage and contiguous bone (Figs. 180.2 and 180.3 ).

Clinical Manifestations

Arthritis must be present ≥6 wk to make a diagnosis of any JIA subtype. Arthritis is defined by intraarticular swelling or the presence of ≥2 of the following signs: limitation in range of motion (ROM), tenderness or pain on motion, and warmth. Initial symptoms may be subtle or acute and often include morning stiffness with a limp or gelling after inactivity. Easy fatigability and poor sleep quality may be present. Involved joints are often swollen, warm to touch, and uncomfortable on movement or palpation with reduced ROM, but usually are not erythematous. Arthritis in large joints, especially knees, initially accelerates linear growth and causes the affected limb to be longer, resulting in a discrepancy in limb lengths. Continued inflammation stimulates rapid and premature closure of the growth plate, resulting in shortened bones.

Oligoarthritis is defined as involving ≤4 joints within the 1st 6 mo of disease onset, and often only a single joint is involved (see Table 180.4 ). It predominantly affects the large joints of the lower extremities, such as the knees and ankles (Fig. 180.4 ). Isolated involvement of upper-extremity large joints is less common. Those in whom disease never develops in >4 joints are regarded as having persistent oligoarticular JIA , whereas evolution of disease in >4 joints after 6 mo changes the classification to extended oligoarticular JIA and is associated with a worse prognosis. Isolated involvement of the hip is almost never a presenting sign and suggests ERA (see Chapter 181 ) or a nonrheumatic cause. The presence of a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test confers increased risk for asymptomatic anterior uveitis, requiring periodic slit-lamp examination (Table 180.5 ). ANA positivity may also be correlated with younger age at disease onset, female sex, asymmetric arthritis, and fewer involved joints over time.

Table 180.5

Frequency of Ophthalmologic Examination in Patients With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

| Referral | |

| Initial screening examination | |

| Ongoing screening | |

| Oligoarticular JIA, psoriatic arthritis, and enthesitis-related arthritis irrespective of ANA status, onset under 11 yr | |

| AGE AT ONSET (YR) | LENGTH OF SCREENING (YR) |

| <3 | 8 |

| 3-4 | 6 |

| 5-8 | 3 |

| 9-10 | 1 |

| Polyarticular, ANA-positive JIA, onset <10 yr | |

| AGE AT ONSET (YR) | LENGTH OF SCREENING (YR) |

| <6 | 5 |

| 6-9 | 2 |

From Clarke SLN, Sen ES, Ramanan AV: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol 14:27, 2016. p. 3.

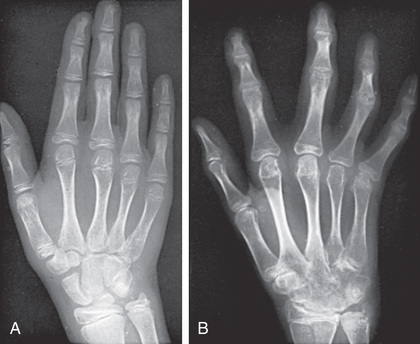

Polyarthritis is characterized by inflammation of ≥5 joints in both upper and lower extremities (Figs. 180.5 and 180.6 ). Rheumatoid factor (RF)–positive polyarthritis resembles the characteristic symmetric presentation of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid nodules on the extensor surfaces of the elbows, spine, and over the Achilles tendons, although unusual, are associated with a more severe course and almost exclusively occur in RF-positive individuals (Fig. 180.7 ). Micrognathia reflects chronic temporomandibular joint disease (Fig. 180.8 ). Cervical spine involvement (Fig. 180.9 ), manifesting as decreased neck extension, occurs with a risk of atlantoaxial subluxation and neurologic sequelae. Hip disease may be subtle, with findings of decreased or painful ROM on examination (Fig. 180.10 ).

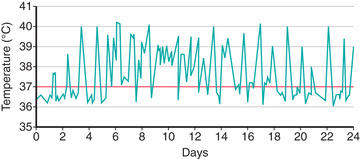

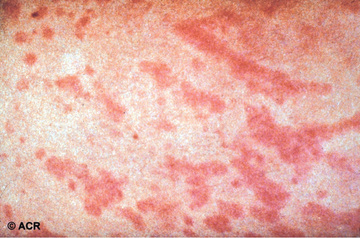

Systemic JIA is characterized by arthritis, fever, rash, and prominent visceral involvement, including hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and serositis (pericarditis). The characteristic fever, defined as spiking temperatures to ≥39°C (102.2°F), occurs on a daily or twice-daily basis for at least 2 wk, with a rapid return to normal or subnormal temperatures (Fig. 180.11 ). The fever is often present in the evening and is frequently accompanied by a characteristic faint, erythematous, macular rash. The evanescent salmon-colored lesions, classic for sJIA, are linear or circular and are usually distributed over the trunk and proximal extremities (Fig. 180.12 ). The classic rash is nonpruritic and migratory with lesions lasting <1 hr. Koebner phenomenon , a cutaneous hypersensitivity in which classic lesions are brought on by superficial trauma, is often present. Heat can also evoke rash. Fever, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy are present in >70% of affected children. Without arthritis, the differential diagnosis includes the episodic fever (autoinflammatory) syndromes (see Chapter 188 ), infection (endocarditis, rheumatic fever, brucellosis), other rheumatic disorders (SLE, vasculitis syndromes, serum sickness, Kawasaki disease, sarcoidosis, Castleman disease), inflammatory bowel disease, hemophagocytic syndromes, and malignancy. Some children initially present with only systemic features and evolve over time, but definitive diagnosis requires presence of arthritis. Arthritis may affect any number of joints, but the course is classically polyarticular, may be very destructive, and can include hip, cervical spine, and temporomandibular joint involvement.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of sJIA that can occur at any time (onset, medication change, active or remission) during the disease course. It is also referred to as secondary hemophagocytic syndrome or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (see Chapter 534.2 ). There is increasing evidence that sJIA/MAS and HLH share similar functional defects in granule-dependent cytotoxic lymphocyte activity. In addition, sJIA-associated MAS and HLH share genetic variants in approximately 35% of patients with sJIA/MAS. MAS classically manifests as acute onset of high-spiking fevers, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and encephalopathy. Laboratory evaluation shows thrombocytopenia and leukopenia with elevated liver enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, and triglycerides. Patients may have purpura and mucosal bleeding, as well as elevated fibrin split product values and prolonged prothrombin and partial prothromboplastin times. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) falls because of hypofibrinogenemia and hepatic dysfunction, a feature useful in distinguishing MAS from a flare of systemic disease (Table 180.6 ). An international consensus panel developed a set of classification criteria for sJIA-associated MAS, including hyperferritinemia (>684 ng/mL) and any 2 of the following: thrombocytopenia (≤181 × 109 /L), elevated liver enzymes (aspartate transaminase >48 U/L), hypertriglyceridemia (>156 mg/dL), and hypofibrinogenemia (≤360 mg/dL) (Table 180.6 ). These criteria apply to a febrile patient suspected of sJIA and in the absence of disorders such as immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, infectious hepatitis, familial hypertriglyceridemia or visceral leishmaniasis. A relative change in laboratory values is likely more relevant in making an early diagnosis than are absolute normal values . A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy may be helpful in diagnosis, but evidence of hemophagocytosis is not always evident. Emergency treatment with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone, cyclosporine, or anakinra may be effective. Severe cases may require therapy similar to that for primary HLH (see Chapter 534.2 ).

Bone mineral metabolism and skeletal maturation are adversely affected in children with JIA, regardless of subtype. Children with JIA have decreased bone mass (osteopenia), which appears to be associated with increased disease activity. Increased levels of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, both key regulators in bone metabolism, have deleterious effects on bone within the joint as well as systemically in the axial and appendicular bones. Abnormalities of skeletal maturation become most prominent during the pubertal growth spurt.

Diagnosis

JIA is a clinical diagnosis without any diagnostic laboratory tests. The meticulous clinical exclusion of other diseases and many mimics is therefore essential. Laboratory studies, including tests for ANA and RF, are only supportive or prognostic, and their results may be normal in patients with JIA (see Tables 180.1 , 180.3 , and 180.4 ).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for arthritis is broad and a careful, thorough investigation for other underlying etiology is imperative (Table 180.7 ). History, physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiography may help exclude other possible causes. Arthritis can be a presenting manifestation for any of the multisystem rheumatic diseases of childhood, including systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 183 ), juvenile dermatomyositis (see Chapter 184 ), sarcoidosis (see Chapter 190 ), and the vasculitic syndromes (see Chapter 192 ). In scleroderma (see Chapter 185 ), limited ROM caused by sclerotic skin overlying a joint may be confused with sequelae from chronic inflammatory arthritis. Acute rheumatic fever is characterized by exquisite joint pain and tenderness, remittent fever, and migratory polyarthritis. Autoimmune hepatitis can also be associated with an acute arthritis.

Many infections are associated with arthritis, and a recent history of infectious symptoms may help make a distinction. Viruses, including parvovirus B19, rubella, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus, and HIV, can induce a transient arthritis. Arthritis may follow enteric infections (see Chapter 182 ). Lyme disease should be considered in children with oligoarthritis living in or visiting endemic areas (see Chapter 249 ). Although a history of tick exposure, preceding flulike illness, and subsequent rash should be sought, these are not always present. Monoarticular arthritis unresponsive to antiinflammatory treatment may be the result of chronic mycobacterial or other infection, such as Kingella kingae , and the diagnosis is established by synovial fluid analysis (PCR) or biopsy. Acute onset of fever and a painful, erythematous, hot joint suggests septic arthritis (see Chapter 705 ). Isolated hip pain with limited ROM suggests suppurative arthritis, osteomyelitis (see Chapter 704 ), toxic synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and chondrolysis of the hip (see Chapter 698 ).

Lower-extremity arthritis and tenderness over insertion of ligaments and tendons, especially in a boy, suggests ERA (see Chapter 181 ). Psoriatic arthritis can manifest as limited joint involvement in an unusual distribution (e.g., small joints of hand and ankle) years before onset of cutaneous disease. Inflammatory bowel disease may manifest as oligoarthritis, usually affecting joints in the lower extremities, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms, elevations in ESR, and microcytic anemia.

Many conditions present solely with arthralgia (i.e., joint pain). Hypermobility may cause joint pain, especially in the lower extremities. Growing pains should be suspected in a child age 4-12 yr complaining of leg pain in the evening with normal investigative studies and no morning symptoms. Nocturnal pain that awakens the child also alerts to the possibility of a malignancy. An adolescent with missed school days may suggest a diagnosis of fibromyalgia (see Chapter 193 ).

Children with leukemia or neuroblastoma may have joint or bone pain resulting from malignant infiltration of the bone, synovium, or more often the bone marrow, sometimes months before demonstrating lymphoblasts on peripheral blood smear. Physical examination may reveal no tenderness, a deeper pain with palpation of the bone, or pain out of proportion to exam findings. Malignant pain often awakens the child from sleep and may cause cytopenias. Because platelets are an acute-phase reactant, a high ESR with leukopenia and a low normal platelet count may also be a clue to underlying leukemia. In addition, the characteristic quotidian fever of sJIA is absent in malignancy. Bone marrow examination is necessary for diagnosis. Some diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, and the glycogen storage diseases, have associated arthropathies (see Chapter 194 ). Swelling that extends beyond the joint can be a sign of lymphedema or Henoch-Schönlein purpura (see Chapter 192.1 ). A peripheral arthritis indistinguishable from JIA occurs in the humoral immunodeficiencies (see Chapter 150 ), such as common variable immunodeficiency and X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Skeletal dysplasias associated with a degenerative arthropathy are diagnosed from their characteristic radiologic abnormalities.

Systemic onset of JIA often presents as a fever of unknown origin (see Chapter 204 ). Important considerations in the differential diagnosis include infections (endocarditis, brucellosis, cat scratch disease, Q fever, mononucleosis), autoinflammatory disease (see Chapter 188 ) malignancy (leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma) and HLH (see Chapter 534.2 ).

Laboratory Findings

Hematologic abnormalities often reflect the degree of systemic or articular inflammation, with elevated white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts and a microcytic anemia. Inflammation may also cause elevations in ESR and C-reactive protein, although it is not unusual for both to be normal in children with JIA.

Elevated ANA titers are present in 40–85% of children with oligoarticular or polyarticular JIA, but are rare with sJIA. ANA seropositivity is associated with increased risk of chronic uveitis in JIA. Approximately 5–15% of patients with polyarticular JIA are seropositive for RF. Anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, as with RF, is a marker of more aggressive disease. Both ANA and RF seropositivity can occur in association with transient events, such as viral infection.

Children with sJIA usually have striking elevations in inflammatory markers and WBC and platelet counts. Hemoglobin levels are low, typically 7-10 g/dL, with indices consistent with anemia of chronic disease. The ESR is usually high, except in MAS. Although immunoglobulin levels tend to be high, ANA and RF are uncommon. Ferritin values are typically elevated and can be markedly increased in MAS (>10,000 ng/mL). In the setting of MAS, all cell lines have the potential to decline precipitously because of the consumptive process. A low or normal WBC count and/or platelet count in a child with active sJIA should raise concerns for MAS.

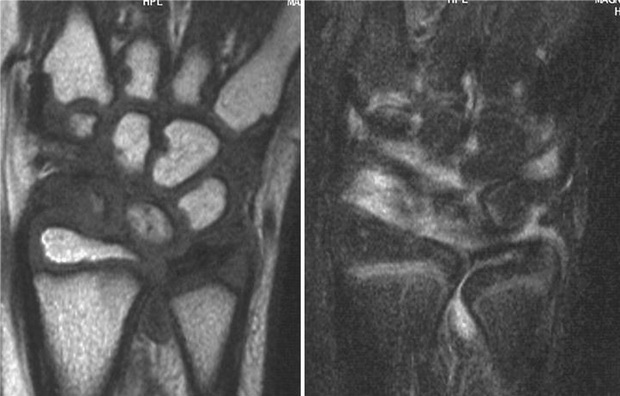

Early radiographic changes of arthritis include soft tissue swelling, periarticular osteopenia, and periosteal new-bone apposition around affected joints (Fig. 180.13 ). Continued active disease may lead to subchondral erosions, loss of cartilage, with varying degrees of bony destruction, and fusion. Characteristic radiographic changes in cervical spine, most frequently in the neural arch joints at C2-C3 (see Fig. 180.9 ), may progress to atlantoaxial subluxation. MRI is more sensitive than radiography to detect early changes (Fig. 180.14 ).

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to achieve disease remission, prevent or halt joint damage, and foster normal growth and development. All children with JIA need individualized treatment plans, and management is tailored according to disease subtype and severity, presence of poor prognostic indicators, and response to medications. Disease management also requires monitoring for potential medication toxicities (see Chapter 179 ).

Children with oligoarthritis often show partial response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with improvement in inflammation and pain (Table 180.8 ). Those who have no or partial response after 4-6 wk of treatment with NSAIDs, or who have functional limitations such as joint contracture or leg-length discrepancy, benefit from injection of intraarticular corticosteroids. Triamcinolone hexacetonide is a long-lasting preparation that provides a prolonged response. A substantial fraction of patients with oligoarthritis show no response to NSAIDs and injections, and therefore require treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including methotrexate, and, if no response, TNF inhibitors.

Table 180.8

Pharmacologic Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

| TYPICAL MEDICATIONS | TYPICAL DOSES | JIA SUBTYPE | SIDE EFFECT(S) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGS | |||

| Naproxen | 15 mg/kg/day PO divided bid (maximum dose 500 mg bid) |

Polyarthritis Systemic Oligoarthritis |

Gastritis, renal and hepatic toxicity, pseudoporphyria |

| Ibuprofen | 40 mg/kg/day PO divided tid (maximum dose 800 mg tid) | Same as above | Same as above |

| Meloxicam | 0.125 mg/kg PO once daily (maximum dose 15 mg daily) | Same as above | Same as above |

| DISEASE-MODIFYING ANTIRHEUMATIC DRUGS | |||

| Methotrexate | 0.5-1 mg/kg PO or SC weekly (maximum dose 25 mg/wk) |

Polyarthritis Systemic Persistent or extended oligoarthritis |

Nausea, vomiting, oral ulcerations, hepatic toxicity, blood count dyscrasias, immunosuppression, teratogenicity |

| Sulfasalazine |

Initial 12.5 mg/kg PO daily; increase by 10 mg/kg/day Maintenance: 40-50 mg/kg divided bid (maximum dose 2 g/day) |

Polyarthritis | GI upset, allergic reaction, pancytopenia, renal and hepatic toxicity, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Leflunomide* | 10-20 mg PO daily | Polyarthritis | GI upset, hepatic toxicity, allergic rash, alopecia (reversible), teratogenicity (needs washout with cholestyramine) |

| BIOLOGIC AGENTS | |||

| Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor-α | |||

| Etanercept | 0.8 mg/kg SC weekly or 0.4 mg/kg SC twice weekly (maximum dose 50 mg/wk) |

Polyarthritis Systemic Persistent or extended oligoarthritis |

Immunosuppressant, concern for malignancy, demyelinating disease, lupus-like reaction, injection site reaction |

| Infliximab* | 3-10 mg/kg IV q4-8 wk | Same as above | Same as above, infusion reaction |

| Adalimumab |

10 to <15 kg: 10 mg SC every other week 15 to <30 kg: 20 mg SC every other week >30 kg: 40 mg SC every other week |

Same as above | Same as above |

| Anticytotoxic T-Lymphocyte–Associated Antigen-4 Immunoglobulin | |||

| Abatacept |

<75 kg: 10 mg/kg/dose IV q4wk 75-100 kg: 750 mg/dose IV q4wk >100 kg: 1,000 mg/dose IV q4wk SC once weekly: 10 to <25 kg: 50 mg ≥25 to <50 kg: 87.5 mg ≥50 kg: 125 mg |

Polyarthritis | Immunosuppressant, concern for malignancy, infusion reaction |

| Anti-CD20 | |||

| Rituximab* | 750 mg/m2 IV 2 wk × 2 (maximum dose 1,000 mg) | Polyarthritis | Immunosuppressant, infusion reaction, progressive multifocal encephalopathy |

| Interleukin-1 Inhibitors | |||

| Anakinra* | 1-2 mg/kg SC daily (maximum dose 100 mg/day) | Systemic | Immunosuppressant, GI upset, injection site reaction |

| Canakinumab |

15-40 kg: 2 mg/kg/dose SC q8wk >40 kg: 150 mg SC q8wk |

Systemic | Immunosuppressant, headache, GI upset, injection site reaction |

| Rilonacept* | 2.2 mg/kg/dose SC weekly (maximum dose 160 mg) | Systemic | Immunosuppressant, allergic reaction, dyslipidemia, injection site reaction |

| Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonist | |||

| Tocilizumab |

IV q2 wk: <30 kg: 12 mg/kg/dose q2wk >30 kg: 8 mg/kg/dose q2wk (maximum dose 800 mg) |

Systemic Polyarthritis |

Immunosuppressant, hepatic toxicity, dyslipidemia, cytopenias, GI upset, infusion reaction |

|

SC: <30 kg: 162 mg/dose q3wk ≥30 kg: 162 mg/dose q2wk |

Polyarthritis | ||

* Not indicated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in JIA as of 2018.

bid, Twice daily; GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; PO, oral; q, every; SC, subcutaneous; tid, 3 times daily.

NSAIDs alone rarely induce remission in children with polyarthritis or sJIA. Methotrexate is the oldest and least toxic of the DMARDs available for adjunctive therapy. It may take 6-12 wk to see the effects of methotrexate. Failure of methotrexate monotherapy warrants the addition of a biologic DMARD. Biologic medications that inhibit proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, demonstrated excellent disease control. TNF-α antagonists (e.g., etanercept, adalimumab ) are used to treat children with an inadequate response to methotrexate, with poor prognostic factors, or with severe disease onset. Early aggressive therapy with a combination of methotrexate and a TNF-α antagonist may result in earlier achievement of clinically inactive disease. Abatacept, a selective inhibitor of T-cell activation, and tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, have demonstrated efficacy in and are approved for treatment of polyarticular JIA (Table 180.8 ).

TNF inhibition is not as effective for the systemic symptoms found in sJIA. When systemic symptoms dominate, systemic corticosteroids are started followed by the initiation of IL-1 or IL-6 antagonist therapy, which often induces a dramatic and rapid response. Patients with severe disease activity may go directly to anakinra. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, and tocilizumab are FDA-approved treatments for sJIA in children older than 2 yr (Table 180.8 ). Standardized consensus treatment plans to guide therapy for sJIA outline 4 treatment plans based on glucocorticoids, methotrexate, anakinra, or tocilizumab, with optional glucocorticoid use in the latter 3 plans as clinically indicated.

With the advent of newer DMARDs, the use of systemic corticosteroids can often be avoided or minimized. Systemic corticosteroids are recommended only for management of severe systemic illness, for bridge therapy during the wait for therapeutic response to a DMARD, and for control of uveitis. Steroids impose risks of severe toxicities, including Cushing syndrome, growth retardation, and osteopenia, and they do not prevent joint destruction.

Oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (tofacitinib, ruxolitinib) inhibit JAK signaling pathways involved in immune activation and inflammation. Tofacitinib is FDA approved for adults with rheumatoid arthritis.

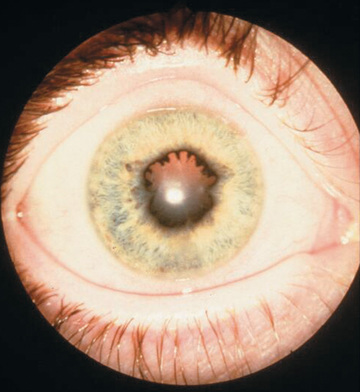

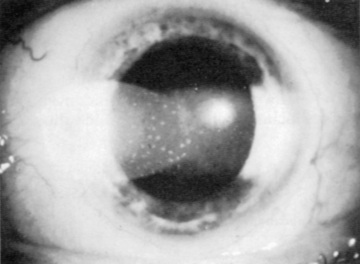

Management of JIA must include periodic slit-lamp ophthalmologic examinations to monitor for asymptomatic uveitis (Figs. 180.15 and 180.16 ; see Table 180.4 ). Optimal treatment of uveitis requires collaboration between the ophthalmologist and rheumatologist; initial management may include mydriatics and corticosteroids used topically, systemically, or through periocular injection. DMARDs allow for a decrease in exposure to steroids, and methotrexate and TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab and infliximab) are effective in treating severe uveitis.

Dietary evaluation and counseling to ensure appropriate calcium, vitamin D, protein, and caloric intake are important for children with JIA. Physical therapy and occupational therapy are invaluable adjuncts to any treatment program. A social worker and nurse clinician can be important resources for families, to recognize stresses imposed by a chronic illness, to identify appropriate community resources, and to aid compliance with the treatment protocol.

Prognosis

Although the course of JIA in an individual child is unpredictable, some prognostic generalizations can be made on the basis of disease type and course. Studies analyzing management of JIA in the pre–TNF-α era indicate that up to 50% of patients with JIA have active disease persisting into early adulthood, often with severe limitations of physical function.

Children with persistent oligoarticular disease fare well, with a majority achieving disease remission. Those with extended oligoarticular disease have a poorer prognosis. Children with oligoarthritis, particularly girls who are ANA positive and with onset of arthritis before 6 yr of age, are at greatest risk for development of chronic uveitis. There is no association between the activity or severity of arthritis and uveitis. Persistent, uncontrolled anterior uveitis (see Fig. 180.15 ) can cause posterior synechiae, cataracts, glaucoma, and band keratopathy, with resultant blindness. Morbidity can be averted with early diagnosis and implementation of systemic therapy.

The child with polyarticular JIA often has a more prolonged course of active joint inflammation and requires early and aggressive therapy. Predictors of severe and persistent disease include young age at onset, RF seropositivity or rheumatoid nodules, presence of anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, and many affected joints. Disease involving the hip and hand/wrist is also associated with a poorer prognosis and may lead to significant functional impairment.

Systemic JIA is often the most difficult to control in terms of both articular inflammation and systemic manifestations. Poorer prognosis is related to polyarticular distribution of arthritis, fever lasting >3 mo, and increased inflammatory markers, such as platelet count and ESR, for >6 mo. IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors have changed the management and improved the outcomes for children with severe and prolonged systemic disease.

Orthopedic complications include leg length discrepancy and flexion contractures, particularly of the knees, hips, and wrists. Discrepancies in leg length can be managed with a shoe lift on the shorter side to prevent secondary scoliosis. Joint contractures require aggressive medical control of arthritis, often in conjunction with intraarticular corticosteroid injections, appropriate splinting, and stretching of the affected tendons. Popliteal cysts may require no treatment if they are small or respond to intraarticular corticosteroids in the anterior knee.

Psychosocial adaptation may be affected by JIA. Studies indicate that, compared with controls, a significant number of children with JIA have problems with lifetime adjustment and employment. Disability not directly associated with arthritis may continue into young adulthood in as many as 20% of patients, together with continuing chronic pain syndromes at a similar frequency. Psychological complications, including problems with school attendance and socialization, may respond to counseling by mental health professionals.