The Hip

Wudbhav N. Sankar, Jennifer J. Winell, B. David Horn, Lawrence Wells

Anatomically, the hip joint is a ball-and-socket articulation between the femoral head and acetabulum. The hip joint is a pivotal joint of the lower extremity, and its functional demands require both stability and flexibility.

Growth and Development

The hip joint begins to develop at about the 7th wk of gestation, when a cleft appears in the mesenchyme of the primitive limb bud. These precartilaginous cells differentiate into a fully formed cartilaginous femoral head and acetabulum by the 11th wk of gestation (see Chapter 20 ). At birth, the neonatal acetabulum is completely composed of cartilage, with a thin rim of fibrocartilage called the labrum .

The very cellular hyaline cartilage of the acetabulum is continuous with the triradiate cartilages, which divide and interconnect the three osseous components of the pelvis (the ilium , ischium , and pubis ). The concave shape of the hip joint is determined by the presence of a spherical femoral head.

Several factors determine acetabular depth, including interstitial growth within the acetabular cartilage, appositional growth under the perichondrium, and growth of adjacent bones (the ilium, ischium, and pubis). In the neonate, the entire proximal femur is a cartilaginous structure, which includes the femoral head and the greater and lesser trochanters. The three main growth areas are the physeal plate, the growth plate of the greater trochanter, and the femoral neck isthmus. Between the 4th and 7th mo of life, the proximal femoral ossification center (in the center of the femoral head) appears. This ossification center continues to enlarge, along with its cartilaginous anlage, until adult life, when only a thin layer of articular cartilage remains. During this period of growth, the thickness of the cartilage surrounding this bony nucleus gradually decreases, as does the thickness of the acetabular cartilage. The growth of the proximal femur is affected by muscle pull, the forces transmitted across the hip joint with weight bearing, normal joint nutrition, circulation, and muscle tone. Alterations in these factors can cause profound changes in the development of the proximal femur.

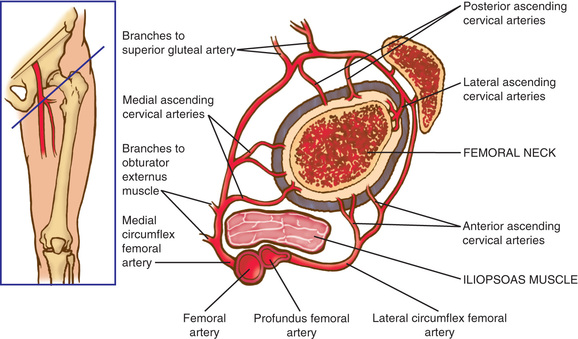

Vascular Supply

The blood supply to the capital femoral epiphysis is complex and changes with growth of the proximal femur. The proximal femur receives its arterial supply from intraosseous (primarily the medial femoral circumflex artery) and extraosseous vessels (Fig. 698.1 ). The retinacular vessels (extraosseous) lie on the surface of the femoral neck but are intracapsular because they enter the epiphysis from the periphery. This makes the blood supply vulnerable to damage from septic arthritis, trauma, thrombosis, and other vascular insults. Interruption of this tenuous blood supply can lead to avascular necrosis of the femoral head and permanent deformity of the hip.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Wudbhav N. Sankar, B. David Horn, Jennifer J. Winell, Lawrence Wells

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) refers to a spectrum of pathology in the development of the immature hip joint. Formerly called congenital dislocation of the hip , DDH more accurately describes the variable presentation of the disorder, encompassing mild dysplasia as well as frank dislocation.

Classification

Acetabular dysplasia refers to abnormal morphology and development of the acetabulum. Hip subluxation is defined as only partial contact between the femoral head and acetabulum. Hip dislocation refers to a hip with no contact between the articulating surfaces of the hip. DDH is classified into two major groups: typical and teratologic . Typical DDH occurs in otherwise normal patients or those without defined syndromes or genetic conditions. Teratologic hip dislocations usually have identifiable causes, such as arthrogryposis or a genetic syndrome, and occur before birth.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Although the etiology remains unknown, the final common pathway in the development of DDH is increased laxity of the joint, which fails to maintain a stable femoroacetabular articulation. This increased laxity is probably the result of a combination of hormonal, mechanical, and genetic factors. A positive family history for DDH is found in 12–33% of affected patients. DDH is more common among female patients (80%), which is thought to be because of the greater susceptibility of female fetuses to maternal hormones, such as relaxin, which increases ligamentous laxity. Although only 2–3% of all babies are born in breech presentation, the incidence of DDH in these patients is 16–25%.

Any condition that leads to a tighter intrauterine space and, consequently, less room for normal fetal motion may be associated with DDH. These conditions include oligohydramnios, large birth weight, and first pregnancy. The high rate of association of DDH with other intrauterine molding abnormalities , such as torticollis and metatarsus adductus, supports the theory that the crowding phenomenon has a role in the pathogenesis. The left hip is the most commonly affected hip. In the most common fetal position, the left hip is usually forced into adduction by the mother's sacrum.

Epidemiology

Although most newborn screening studies suggest that some degree of hip instability can be detected in 1 in 100 to 1 in 250 babies, actual dislocated or dislocatable hips are much less common, being found in 1-1.5 of 1,000 live births.

There is marked geographic and racial variation in the incidence of DDH. The reported incidence based on geography ranges from 1.7 in 1,000 babies in Sweden to 75 in 1,000 in Yugoslavia to 188.5 in 1,000 in a district in Manitoba, Canada. The incidence of DDH is almost 0% in Chinese and African newborns, whereas it is 1% for hip dysplasia and 0.1% for hip dislocation in white newborns. These differences may result from environmental factors, such as child-rearing practices, rather than genetic predisposition. African and Asian caregivers have traditionally carried babies against their bodies in a shawl so that a child's hips are flexed, abducted, and free to move. This keeps the hips in the optimal position for stability and for dynamic molding of the developing acetabulum by the cartilaginous femoral head. Children in Native American and Eastern European cultures, which have a relatively high incidence of DDH, have historically been swaddled in confining clothes that bring their hips into extension. This position increases the tension of the psoas muscle-tendon unit and might predispose the hips to displace and eventually dislocate laterally and superiorly.

Pathoanatomy

In DDH, several secondary anatomic changes can prevent reduction. Both the fatty tissue in the depths of the socket, known as the pulvinar, and the ligamentum teres can hypertrophy, blocking reduction of the femoral head. The transverse acetabular ligament usually thickens as well, which effectively narrows the opening of the acetabulum. In addition, the shortened iliopsoas tendon becomes taut across the front of the hip, creating an hourglass shape to the hip capsule, which limits access to the acetabulum. Over time, the dislocated femoral head places pressure on the acetabular rim and labrum, causing the labrum to infold and become thick.

The shape of a normal femoral head and acetabulum depends on a concentric reduction between the two. The more time that a hip spends dislocated, the more likely that the acetabulum will develop abnormally. Without a femoral head to provide a template, the acetabulum will become progressively shallow, with an oblique acetabular roof and a thickened medial wall.

Clinical Findings

The Neonate

DDH in the neonate is asymptomatic and must be screened for by specific maneuvers. Physical examination must be carried out with the infant unclothed and placed supine in a warm, comfortable setting on a flat examination table. A feeding just prior to examination is preferable.

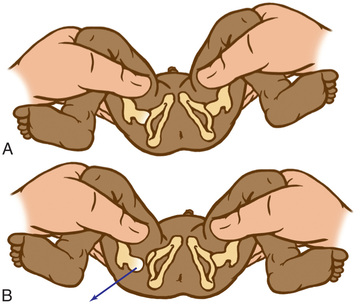

The Barlow provocative maneuver assesses the potential for dislocation of an initially nondisplaced hip. The examiner adducts the flexed hip and gently pushes the thigh posteriorly in an effort to dislocate the femoral head (Fig. 698.2 ). In a positive test, the hip is felt to slide out of the acetabulum. As the examiner relaxes the proximal push, the hip can be felt to slip back into the acetabulum.

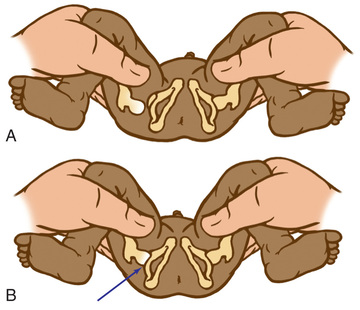

The Ortolani test is the reverse of the Barlow test: The examiner attempts to reduce a hip that is dislocated at rest (Fig. 698.3 ). The examiner grasps the child's thigh between the thumb and index finger and, with the 4th and 5th fingers, lifts the greater trochanter while simultaneously abducting the hip. When the test is positive, the femoral head will slip into the socket with a delicate clunk that is palpable but usually not audible. It should be a gentle, nonforced maneuver.

A hip click is the high-pitched sensation (or sound) felt at the very end of abduction during testing for DDH with Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers. A hip click can be differentiated from a hip clunk , which is felt as the femoral head goes in and out of joint. Hip clicks usually originate in the ligamentum teres or occasionally in the fascia lata or psoas tendon and do not indicate a significant hip abnormality.

The Infant

As the baby enters the 2nd and 3rd mo of life, the soft tissues begin to tighten, and the Ortolani and Barlow tests are no longer reliable. In this age group, the examiner must look for other specific physical findings, including limited hip abduction, apparent shortening of the thigh, proximal location of the greater trochanter, asymmetry of the gluteal or thigh folds (Fig. 698.4 ), and positioning of the hip. Limitation of abduction is the most reliable sign of a dislocated hip in this age group.

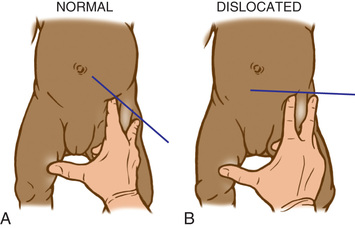

Shortening of the thigh, the Galeazzi sign, is best appreciated by placing both hips in 90 degrees of flexion and comparing the height of the knees, looking for asymmetry (Fig. 698.5 ). Asymmetry of gluteal skin creases may be a sign of hip dysplasia. Another helpful test is the Klisic test, in which the examiner places the 3rd finger over the greater trochanter and the index finger of the same hand on the anterior superior iliac spine. In a normal hip, an imaginary line drawn between the two fingers points to the umbilicus. In the dislocated hip, the trochanter is elevated, and the line projects halfway between the umbilicus and the pubis (Fig. 698.6 ).

The Walking Child

The walking child often presents to the physician after the family has noticed a limp, a waddling gait, or a leg-length discrepancy. The affected side appears shorter than the normal extremity, and the child toe-walks on the affected side. The Trendelenburg sign (see Chapter 693 ) is positive in these children, and an abductor lurch is usually observed when the child walks. As in the younger child, there is limited hip abduction on the affected side and the knees are at different levels when the hips are flexed (the Galeazzi sign). Excessive lordosis, which develops secondary to altered hip mechanics, is common and is often the presenting complaint.

Diagnostic Testing

Ultrasonography

Because it is superior to radiographs for evaluating cartilaginous structures, ultrasonography is the diagnostic modality of choice for DDH before the appearance of the femoral head ossific nucleus (4-6 mo). During the early newborn period (0-4 wk), however, physical examination is preferred over ultrasonography because there is a high incidence of false-positive sonograms in this age group. Therefore, waiting to obtain an ultrasound until the infant is at least 1 mo of age is preferred unless the child has a strongly positive physical exam. In addition to elucidating the static relationship of the femur to the acetabulum, ultrasonography provides dynamic information about the stability of the hip joint. The ultrasound examination can be used to monitor acetabular development, particularly of infants in Pavlik harness treatment; this method can minimize the number of radiographs taken and might allow the clinician to detect treatment failure earlier.

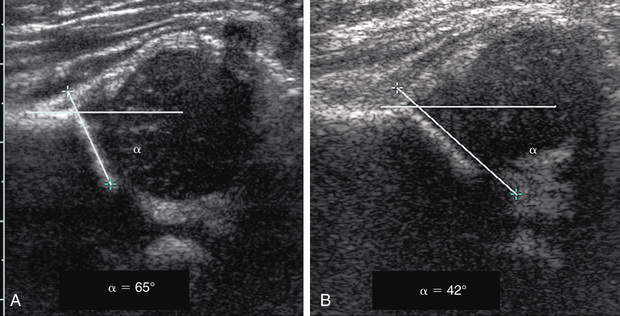

In the Graf technique, the transducer is placed over the greater trochanter, which allows visualization of the ilium, the bony acetabulum, the labrum, and the femoral epiphysis (Fig. 698.7 ). The angle formed by the line of the ilium and a line tangential to the boney roof of the acetabulum is termed the α angle and represents the depth of the acetabulum. Values >60 degrees are considered normal, and those <60 degrees imply acetabular dysplasia. The β angle is formed by a line drawn tangential to the labrum and the line of the ilium; this represents the cartilaginous roof of the acetabulum. A normal β angle is <55 degrees; as the femoral head subluxates, the β angle increases. Another useful test is to evaluate the position of the center of the head compared to the vertical line of the ilium. If the line of the ilium falls lateral to the center of the head, the epiphysis is considered reduced. If the line falls medial to the center of the head, the epiphysis is uncovered and is either subluxated or dislocated.

Screening for DDH with ultrasound remains controversial. Although routinely performed in Europe, meta-analyses indicate that data are insufficient to give clear recommendations. In the United States, the current recommendations are that every newborn undergo a clinical examination for hip instability. Children who have findings suspicious for DDH should be followed up with ultrasound. Most authors agree that infants with risk factors for DDH (breech position, family history, torticollis) should be screened with ultrasound regardless of the clinical findings.

Radiography

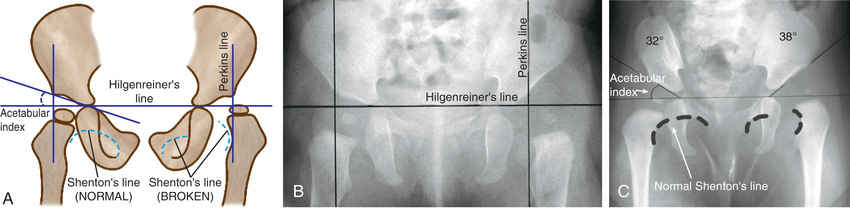

Radiographs are recommended for an infant once the proximal femoral epiphysis ossifies, usually by 4-6 mo. In infants of this age, radiographs have proven to be more effective, less costly, and less operator dependent than an ultrasound examination. An anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis can be interpreted with the aid of several classic lines drawn on it (Fig. 698.8 ).

Hilgenreiner's line is a horizontal line drawn through the top of both triradiate cartilages (the clear area in the depth of the acetabulum). Perkins line is a vertical line through the most lateral ossified margin of the roof of the acetabulum, drawn perpendicular to Hilgenreiner's line. The ossific nucleus of the femoral head should be located in the medial lower quadrant of the intersection of these two lines. Shenton's line is a curved line drawn from the medial aspect of the femoral neck to the lower border of the superior pubic ramus. In a child with normal hips, this line is a continuous contour. In a child with hip subluxation or dislocation, this line consists of two separate arcs and is described as “broken.”

The acetabular index is the angle formed between Hilgenreiner's line and a line drawn from the depth of the acetabular socket to the most lateral ossified margin of the roof of the acetabulum. This angle measures the development of the osseous roof of the acetabulum. In the newborn, the acetabular index can be up to 40 degrees; by 4 mo in the normal infant, it should be no more than 30 degrees. In the older child, the center-edge angle is a useful measure of femoral head coverage. This angle is formed at the juncture of the Perkins line and a line connecting the lateral margin of the acetabulum to the center of the femoral head. In children 6-13 yr old, an angle >19 degrees is normal, whereas in children 14 yr and older, an angle >25 degrees is considered normal.

Treatment

The goals in the management of DDH are to obtain and maintain a concentric reduction of the femoral head within the acetabulum to provide the optimal environment for the normal development of both the femoral head and acetabulum. The later the diagnosis of DDH is made, the more difficult it is to achieve these goals, the less potential there is for acetabular and proximal femoral remodeling, and the more complex the required treatments.

Newborns and Infants Younger Than 6 Months

Newborns hips that are Barlow-positive (reduced but dislocatable) or Ortolani-positive (dislocated but reducible) should generally be treated with a Pavlik harness as soon as the diagnosis is made. The management of newborns with dysplasia who are younger than 4 wk of age is less clear. A significant proportion of these hips normalize within 3-4 wk; consequently, many physicians prefer to reexamine these newborns after a few weeks before making treatment decisions. A study of 128 newborns with mildly dysplastic hips based on the results of an ultrasound (alpha angles between 43 and 50 degrees) who were randomly assigned to receive immediate abduction splinting or active sonographic surveillance from birth with Frejka splinting (if treatment was subsequently needed), revealed no difference in radiologic findings at 6 yr of age.

Triple diapers or abduction diapers have no place in the treatment of DDH in the newborn; they are usually ineffective and give the family a false sense of security. Acetabular dysplasia, subluxation, or dislocation can all be readily managed with the Pavlik harness. Although other braces are available (von Rosen splint, Frejka pillow), the Pavlik harness remains the most commonly used device worldwide (Fig. 698.9 ). By maintaining the Ortolani-positive hip in a Pavlik harness on a full-time basis for 6 wk, hip instability resolves in approximately 75% of cases. After 6 mo of age, the failure rate for the Pavlik harness is >50% because it is difficult to maintain the increasingly active and crawling child in the harness. Frequent examinations and readjustments are necessary to ensure that the harness is correctly fitted. The anterior straps of the harness should be set to maintain the hips in flexion (usually ~90-100 degrees); excessive flexion is discouraged because of the risk of femoral nerve palsy. The posterior straps are designed to encourage abduction. These are generally set to allow adduction just to neutral, as forced abduction by the harness can lead to avascular necrosis of the femoral epiphysis.

If follow-up examinations and ultrasounds do not demonstrate concentric reduction of the hip after 3-4 wk of Pavlik harness treatment, the harness should be abandoned. Continued use of the harness beyond this period in a persistently dislocated hip can cause Pavlik harness disease or wearing away of the posterior aspect of the acetabulum, which can make the ultimate reduction less stable.

Children 6 Months to 2 Years of Age

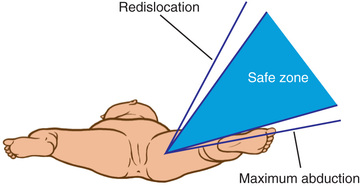

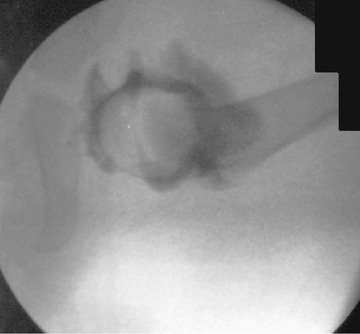

The principal goals in the treatment of late-diagnosed dysplasia are to obtain and maintain reduction of the hip without damaging the femoral head. Closed reductions are performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. The hip is moved to determine the range of motion in which it remains reduced. This is compared to the maximal range of motion to construct a “safe zone” (Fig. 698.10 ). An arthrogram obtained at the time of reduction is very helpful for evaluating the depth and stability of the reduction (Fig. 698.11 ). The reduction is maintained in a well-molded spica cast, with the “human position” of moderate flexion and abduction being the preferred position. After the procedure, single-cut CT or MRI may be used to confirm the reduction. Twelve weeks after closed reduction, the plaster cast is removed; an abduction orthosis is often used at this point to encourage further remodeling of the acetabulum. Failure to obtain a stable hip with a closed reduction indicates the need for an open reduction. In patients younger than 18 mo of age, a concomitant acetabular or femoral procedure is rarely required. The potential for acetabular development after closed or open reduction is excellent and continues for 4-8 yr after the procedure.

Children Older Than 2 Years

Children 2-6 yr of age with a hip dislocation usually require an open reduction. In this age group, a concomitant femoral shortening osteotomy is often performed to reduce the pressure on the proximal femur and minimize the risk of osteonecrosis. Because the potential for acetabular development is markedly diminished in these older children, a pelvic osteotomy is usually performed in conjunction with the open reduction. Postoperatively, patients are immobilized in a spica cast for 6-12 wk.

Complications

The most important complication of DDH is avascular necrosis of the femoral epiphysis. Reduction of the femoral head under pressure or in extreme abduction can result in occlusion of the epiphyseal vessels and produce either partial or total infarction of the epiphysis. Revascularization soon follows, but if the physis is severely damaged, abnormal growth and development can occur. Management, as previously outlined, is designed to minimize this complication. With appropriate treatment, the incidence of avascular necrosis for DDH is reduced to 5–15%. Other complications in DDH include redislocation, residual subluxation, acetabular dysplasia, and postoperative complications, including wound infections.

Bibliography

Bracken J, Tran T, Ditchfield M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: controversies and current concepts. J Paediatr Child Health . 2012;48(11):963–972.

Bruras KR, Aukland SM, Markestad T, et al. Newborns with sonographically dysplastic and potentially unstable hips: 6-year follow-up of an RCT. Pediatrics . 2011;127:e661–e666.

Carroll KL, Schiffern AN, Murray KA, et al. The occurrence of occult acetabular dysplasia in relatives of individuals with developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop . 2016;36(1):96–100.

Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet . 2007;369:1541–1552.

Dogruel H, Atalar H, Yavuz OY, et al. Clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop . 2008;32(3):415–419.

Haynes DJ. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: etiology, pathogenesis and examination and physical findings in the newborn. Instr Course Lect . 2001;50:535–540.

Laborie LB, Engesaeter IO, Lehmann TG, et al. Screening strategies for hip dysplasia: Long-term outcome of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics . 2013;132:492–501.

Lowry CA, Donoghue VB, Murphy JF. Auditing hip ultrasound screening of infants at increased risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child . 2005;90:579–581.

Moseley CF. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: management of the older child. Instr Course Lect . 2001;50:547–553.

Mulpuri K, Song KM, Goldberg MJ, Sevarino K. Detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to 6 months of age. J Am Acad Orthopaedic Surg . 2015;23(3):202–205.

Pacana MJ, Hennrikus WL, Slough J, Curtin W. Ultrasound examination for infants born breech by elective cesarean section with a normal hip exam for instability. J Pediatr Orthop . 2017;37(1):e15–e18.

Pollet V, Percy V, Prior HJ. Relative risk and incidence for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr . 2017;181:202–207.

Roovers EA, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Castelein RM, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2005;90:F25–F30.

Roy DR. Current concepts in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Pediatr Ann . 1999;28:748–752.

Shaw BA, Segal LS. Section on orthopaedics. Evaluation and referral for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants. Pediatrics . 2016;138(6):e20163107.

Shorter D, Hong T, Osborn DA. Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2011;(9) [CD004595].

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics . 2006;117:898–902.

West S, Witt J. Bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hips. BMJ . 2011;342:d2152.

Woolacott NF, Puhan MA, Steurer J, et al. Ultrasonography in screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns: systematic review. BMJ . 2005;330:1413–1415.

Transient Monoarticular Synovitis (Toxic Synovitis)

Wudbhav N. Sankar, Jennifer J. Winell, B. David Horn, Lawrence Wells

Transient synovitis (toxic synovitis) is a reactive arthritis and is one of the most common causes of hip pain in young children.

Etiology

The cause of transient synovitis remains unknown. It has been variously described as a nonspecific inflammatory condition or as a postviral immunologic synovitis because it tends to follow recent viral illnesses.

Clinical Manifestations

Although transient synovitis can occur in all age groups, it is most prevalent in children between 3 and 8 yr of age, with a mean onset at age 6 yr. Approximately 70% of all affected children have had a nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection the 7-14 days before symptom onset. Symptoms often develop acutely and usually consist of pain in the groin, anterior thigh, or knee, which may be referred from the hip. These children are usually able to bear weight on the affected limb and typically walk with an antalgic gait with the foot externally rotated. The hip is not held flexed, abducted, or laterally rotated unless a significant effusion is present. They are often afebrile or have a low-grade fever <38°C (100.4°F).

Diagnosis

Transient synovitis is a clinical diagnosis, but laboratory and radiographic tests can be useful to rule out other more serious conditions. In transient synovitis, infection labs (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum C-reactive protein, and white blood cell counts) are relatively normal, but on occasion a mild elevation in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate is observed. AP and Lauenstein (frog-leg) lateral radiographs of the pelvis may be acquired and are also usually found to be normal. Ultrasonography of the hip is preferred to x-rays and often demonstrates a small joint effusion.

The most important condition to exclude before confirming a diagnosis of toxic synovitis is septic arthritis. Children with septic arthritis usually appear more systemically ill than those with transient synovitis. The pain associated with septic arthritis is more severe, and children often refuse to walk or move their hip at all. High fever, refusal to walk, and elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum C-reactive protein, and white blood cell count all suggest a diagnosis of septic arthritis. If the clinical scenario is suspicious for septic arthritis, an ultrasound-guided aspiration of the hip joint should be performed to make the definitive diagnosis (see Chapter 705 ). An exception to these criteria is hip septic arthritis due to Kingella kingae , which may have minimal inflammation and low-grade or no fever (see Chapter 705 ). MRI may be needed to detect an associated osteomyelitis.

Treatment

The treatment of transient monoarticular synovitis of the hip is symptomatic. Recommended therapies include activity limitation and relief of weight bearing until the pain subsides. Antiinflammatory agents and analgesics can shorten the duration of pain. Most children recover completely within 3-6 wk.

Bibliography

Caird MS, Flynn JM, Leung YL, et al. Factors distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2006;88:1251–1257.

Cook PC. Transient synovitis, septic hip, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: an approach to the correct diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2014;61(6):1109–1118.

Gough-Palmer A, McHugh K. Investigating hip pain in a well child. BMJ . 2007;334:1216–1220.

Kochar MS, Mandiga R, Zurakowski D, et al. Validation of a clinical prediction rule for the differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2004;86:1629–1635.

Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 1999;81:1662–1670.

Perry DC, Bruce C. Evaluating the child who presents with an acute limp. BMJ . 2010;341:444–449.

Taekema HC, Landham PR, Maconochine I. Distinguishing between transient synovitis and septic arthritis in the limping child: how useful are clinical prediction tools? Arch Dis Child . 2009;94:167–168.

Yagupsky P, Dubnov-Raz G, Gene A, et al. Differentiating Kingella kingae septic arthritis of the hip from transient synovitis in young children. J Pediatr . 2014;165:985–989.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

Wudbhav N. Sankar, Jennifer J. Winell, B. David Horn, Lawrence Wells

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD) is a hip disorder of unknown etiology that results from temporary interruption of the blood supply to the proximal femoral epiphysis, leading to osteonecrosis and femoral head deformity.

Etiology

Although the underlying etiology remains obscure, most authors agree that the final common pathway in the development of LCPD is disruption of the vascular supply to the femoral epiphysis, which results in ischemia and osteonecrosis. Infection, trauma, and transient synovitis have all been proposed as causative factors but are unsubstantiated. Factors leading to thrombophilia, an increased tendency to develop thrombosis and a reduced ability to lyse thrombi have been identified. Factor V Leiden mutation, deficiency of proteins C and S, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, antitrypsin, and plasminogen activator might play a role in the abnormal clotting mechanism. These abnormalities in the clotting cascade are thought to increase blood viscosity and the risk for venous thrombosis. Poor venous outflow leads to increased intraosseous pressure, which, in turn, impedes arterial inflow, causing ischemia and cell death.

Epidemiology

The incidence of LCPD in the United States is 1 in 1,200 children with boys 4-5 times more likely to be affected than girls. The peak incidence of the disease is between the ages of 4 and 8 yr. Bilateral involvement is seen in approximately 10% of the patients, but the hips are usually in different stages of collapse. East Asians have the lowest incidence of the disease and whites the highest.

Pathogenesis

Early pathologic changes in the femoral head are the result of ischemia and necrosis; subsequent changes result from the repair process. The disease course may have 4 stages, although variations have been described. The initial stage of the disease, which often lasts 6 mo, is characterized by synovitis, joint irritability, and early necrosis of the femoral head. Revascularization then leads to osteoclastic-mediated resorption of the necrotic segment. The necrotic bone is replaced by fibrovascular tissue rather than new bone, which compromises the structural integrity of the femoral epiphysis. The second stage is the fragmentation stage, which typically lasts 8 mo. During this stage, the femoral epiphysis begins to collapse, usually laterally, and begins to extrude from the acetabulum. The healing stage, which lasts approximately 4 yr, begins with new bone formation in the subchondral region. Reossification begins centrally and expands in all directions. The degree of femoral head deformity depends on the severity of collapse and the amount of remodeling that occurs. The final stage is the residual stage, which begins after the entire head has reossified. A mild amount of remodeling of the femoral head still occurs until the child reaches skeletal maturity. LCPD often damages the proximal femoral physis leading to a short neck (coxa breva) and trochanteric overgrowth.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common presenting symptom is a limp of varying duration. Pain, if present, is usually activity related and may be localized in the groin or referred to the anteromedial thigh or knee region. Failure to recognize that thigh or knee pain in a child may be secondary to hip pathology can cause further delay in the diagnosis. Less commonly, the onset of the disease may be much more acute and may be associated with a failure to ambulate.

Antalgic gait (a limp characterized by a shortening of gait phase on the injured side to alleviate weight-bearing pain) may be particularly prominent after strenuous activity at the end of the day. Hip motion, primarily internal rotation and abduction, is limited. Early in the course of the disease, the limited abduction is secondary to synovitis and muscle spasm in the adductor group; however, with time and the subsequent deformities that can develop, the limitation of abduction can become permanent. A mild hip flexion contracture of 10-20 degrees may be present. Atrophy of the muscles of the thigh, calf, or buttock from disuse secondary to pain may be evident. An apparent leg-length inequality may be caused by an adduction contracture or true shortening on the involved side from femoral head collapse.

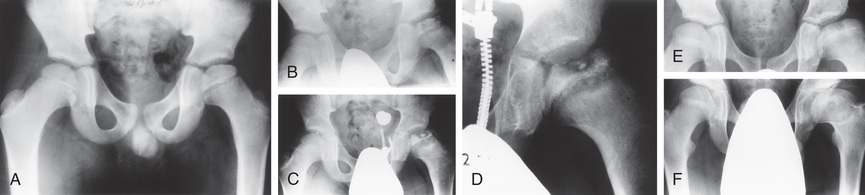

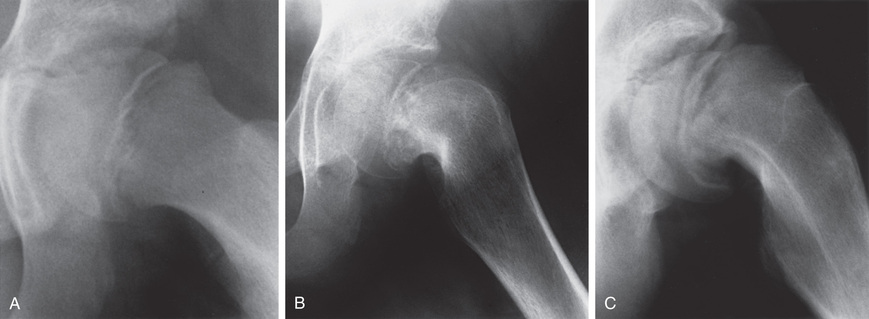

Diagnosis

Routine plain radiographs are the primary diagnostic tool for LCPD. AP and Lauenstein (frog-leg) lateral views are used to diagnose, stage, provide prognosis for, and follow the course of the disease (Fig. 698.12 ). It is important when evaluating disease progression that all radiographs be viewed sequentially and compared with previous radiographs to assess the stage of the disease and to determine the true extent of epiphyseal involvement.

In the initial stage of LCPD, the radiographic changes include a decreased size of the ossification center, lateralization of the femoral head with widening of the medial joint space, a subchondral fracture, and physeal irregularity. In the fragmentation stage, the epiphysis appears fragmented, and there are scattered areas of increased radiolucency and radiodensity. During the reossification stage, the bone density returns to normal via new (woven) bone formation. The residual stage is marked by the reossification of the femoral head, gradual remodeling of head shape until skeletal maturity, and remodeling of the acetabulum.

In addition to these radiographic changes, several classic radiographic signs have been reported that describe a “head at risk” for severe deformity. Lateral extrusion of the epiphysis, a horizontal physis, calcification lateral to the epiphysis, subluxation of the hip, and a radiolucent horizontal V in the lateral aspect of the physis (Gage's sign) are all associated with a poor prognosis.

In the absence of changes on plain radiographs, particularly in the early stages of the disease, MRI is useful to diagnose early infarction and determine the degree of impaired perfusion. It is being used more in early stages to help determine prognosis. During the remodeling or residual stages, MRI is extremely helpful to define the abnormal anatomy and determine the extent of intra-articular injury. Arthrography can be useful to dynamically assess the shape of the femoral head, demonstrate whether a hip can be contained, and diagnose hinge abduction. Table 698.1 outlines the differential diagnosis.

Classification

Catterall proposed a four-group classification based on the amount of femoral epiphysis involvement and a set of radiographic “head at-risk” signs. Group I hips have anterior femoral head involvement of 25%, no sequestrum (an island of dead bone within the epiphysis), and no metaphyseal abnormalities. Group II hips have up to 50% involvement and a clear demarcation between involved and uninvolved segments. Metaphyseal cysts may be present. Group III hips display up to 75% involvement and a large sequestrum. In group IV, the entire femoral head is involved. Use of the Catterall classification system has been limited because of a high degree of interobserver variability.

The Herring lateral pillar classification is the most widely used radiographic classification system for determining treatment and prognosis during the active stage of the disease (Fig. 698.13 ). Unlike the Catterall system, the Herring classification has a high degree of interobserver reliability. Classification is based on several radiographs taken during the early fragmentation stage. The lateral pillar classification system for LCPD evaluates the shape of the femoral head epiphysis on AP radiograph of the hip. The head is divided into three sections or pillars. The lateral pillar occupies the lateral 15–30% of the head width, the central pillar is approximately 50% of the head width, and the medial pillar is 20–35% of the head width. The degree of involvement of the lateral pillar can be subdivided into three groups. In group A, the lateral pillar is radiographically normal. In group B, the lateral pillar has some lucency, but >50% of the lateral pillar height is maintained. In group C, the lateral pillar is more lucent than in group B, and <50% of the pillar height remains. Herring has added a B/C border group to the classification system to describe patients with approximately 50% collapse of the lateral pillar.

Natural History and Prognosis

Children who develop signs and symptoms of LCPD before the age of 6 yr tend to recover with fewer residual problems. Patients older than 9 yr of age at presentation usually have a poor prognosis. The reason for this difference is that the remodeling potential of the femoral head is higher in younger children. Greater extent of femoral head involvement and duration of the disease process are additional factors associated with a poor prognosis. Hips classified as Catterall groups III and IV and lateral pillar group C generally have a poor prognosis.

Treatment

The goal of treatment in LCPD is preservation of a spherical, well-covered femoral head and maintenance of hip range of motion that is close to normal. Although the treatment of LCPD remains controversial, most authors agree that the general approach to these patients should be guided by the principle of containment. This principle is predicated on the fact that while the femoral head is fragmenting, and therefore in a softened condition, it is best to contain it entirely within the acetabulum; by doing so, the acetabulum acts as a mold for the regenerating femoral head. Conversely, failure to contain the head permits it to deform, with resulting extrusion and impingement on the lateral edge of the acetabulum. To be successful, containment must be instituted early while the femoral head is still moldable; once the head has healed, repositioning the femoral epiphysis will not aid remodeling and can, in fact, worsen symptoms.

Initial options to manage symptoms include activity limitation, protected weight bearing, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications. Nonoperative containment can be achieved by using a Petrie cast to restore abduction and to direct the femoral head deeper into the acetabulum. Petrie casts are two long-leg casts that are connected by a bar and can be helpful to keep the hips in abduction and internal rotation (the best position for containment). Casting is generally done in conjunction with an arthrogram to confirm containment and a tenotomy of the adductor tendons. After 6 wk, patients can be transitioned into an abduction orthosis with limited weight bearing. Several older studies did not support the efficacy of casting and long-term bracing as a means of containment, but a subsequent large series reported excellent results with this form of treatment.

Surgical containment may be approached from the femoral side, the acetabular side, or both sides of the hip joint. A varus osteotomy of the proximal femur is the most common procedure. Pelvic osteotomies in LCPD are divided into three categories: acetabular rotational osteotomies, shelf procedures, and medial displacement or Chiari osteotomies. Any of these procedures can be combined with a proximal femoral varus osteotomy when severe deformity of the femoral head cannot be contained by a pelvic osteotomy alone.

After healing of the epiphysis, surgical treatment shifts from containment to management of the residual deformity. Patients with hinge abduction or joint incongruity might benefit from a valgus-producing proximal femoral osteotomy. Coxa breva and overgrowth of the greater trochanter can be managed by performing an advancement of the trochanter. This helps restore the length–tension relationship of the abductor mechanism and can alleviate abductor fatigue. Patients with femoroacetabular impingement from irregularity of the femoral head can often be helped with an osteoplasty or cheilectomy of the offending prominence.

Bibliography

Hailer YD, Montgomery S, Ekborn A, et al. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease and the risk of injuries requiring hospitalization: a register study involving 2579 patients. Acta Orthop . 2012;83(6):572–576.

Hamer AJ. Pain in the hip and knee. BMJ . 2004;328:1067–1069.

Liu YF, Chen WM, Lin YF, et al. Type II collagen gene variants and inherited osteonecrosis of the femoral head. N Engl J Med . 2005;352:2294–2301.

Metcalfe D, Van Dijck S, Parsons N, et al. A twin study of Perthes disease. Pediatrics . 2016;137(3):e20153542.

Perry DC, Green DJ, Bruce CE, et al. Abnormalities of vascular structure and function in children with Perthes disease. Pediatrics . 2012;130:e126–e131.

Perry DC, Machin DM, Pope D, et al. Racial and geographic factors in the incidence of Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease: a systematic review. Am J Epidemiol . 2012;175(3):159–166.

Rich MM, Schoenecker PL. Management of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease using an a-frame orthosis and hip range of motion: a 25-year experience. J Pediatr Orthop . 2013;33:112–119.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Wudbhav N. Sankar, Jennifer J. Winell, B. David Horn, Lawrence Wells

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a hip disorder that affects adolescents, most often between 10 and 16 yr of age, and involves failure of the physis and displacement of the femoral head relative to the neck.

Classification

SCFEs may be classified temporally, according to onset of symptoms (acute, chronic, acute-on-chronic); functionally, according to patient's ability to bear weight (stable or unstable); or morphologically, as the extent of displacement of the femoral epiphysis relative to the neck (mild, moderate, or severe), as estimated by measurement on radiographic or CT images.

An acute SCFE is characterized as one occurring in a patient who has prodromal symptoms for ≤3 wk and should be distinguished from a purely traumatic separation of the epiphysis in a previously normal hip (a true Salter-Harris type I fracture; see Chapter 703 ). The patient with an acute slip usually has some prodromal pain in the groin, thigh, or knee, and usually reports a relatively minor injury (a twist or fall) that is not sufficiently violent to produce an acute fracture of this severity.

Chronic SCFE is the most common form of presentation. Typically, an adolescent presents with a few months’ history of vague groin, thigh, or knee pain and a limp. Radiographs show a variable amount of posterior and inferior migration of the femoral epiphysis and remodeling of the femoral neck in the same direction.

Children with acute-on-chronic SCFE can have features of both acute and chronic conditions. Prodromal symptoms have been present for >3 wk with a sudden exacerbation of pain. Radiographs demonstrate femoral neck remodeling and further displacement of the capital epiphysis beyond the remodeled point of the femoral neck.

The stability classification separates patients based on their ability to ambulate and is more useful in predicting prognosis and establishing a treatment plan. The SCFE is considered stable when the child is able to walk with or without crutches. A child with an unstable SCFE is unable to walk with or without walking aids. Patients with unstable SCFE have a much higher prevalence of osteonecrosis (up to 50%) compared to those with stable SCFE (nearly 0%). This is most likely because of the vascular injury caused at the time of initial displacement.

SCFE may also be categorized by the degree of displacement of the epiphysis on the femoral neck. The head-shaft angle difference is <30 degrees in mild slips, between 30 and 60 degrees in moderate slips, and >60 degrees in severe slips, compared to the normal contralateral side.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

SCFEs are most likely caused by a combination of mechanical and endocrine factors. The plane of cleavage in most SCFEs occurs through the hypertrophic zone of the physis. During normal puberty, the physis becomes more vertically oriented, which converts mechanical forces from compression to shear. In addition, the hypertrophic zone becomes elongated in pubertal adolescents due to high levels of circulating hormones. This widening of the physis decreases the threshold for mechanical failure. Normal ossification depends on a number of different factors, including the thyroid hormone, vitamin D, and calcium. Consequently, it is not surprising that SCFEs occur with increased incidence in children with medical disorders, such as hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, and renal osteodystrophy. Obesity, one of the largest risk factors for SCFE, affects both the mechanical load on the physis and the level of circulating hormones. The combination of mechanical and endocrine factors results in gradual failure of the physis, which allows posterior and inferior displacement of the head in relation to the femoral neck.

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of SCFE is 2 per 100,000 in the general population. Incidence has ranged from 0.2 per 100,000 in eastern Japan to 10.08 per 100,000 in the northeastern United States. The African American and Polynesian populations are reported to have an increased incidence of SCFE. Obesity is the most closely associated risk factor in the development of SCFE; approximately 65% of the patients are >90th percentile in weight-for-age profiles. There is a predilection for males to be affected more often than females and for the left hip to be affected more often than the right. Bilateral involvement has been reported in as many as 60% of cases, nearly half of which may be present at the time of initial presentation.

Clinical Manifestations

The classic patient presenting with a SCFE is an obese African American male between the ages of 11 and 16 yr. Females present earlier, usually between 10 and 14 yr of age. Patients with chronic and stable SCFEs tend to present after weeks to months of symptoms. Patients usually limp to some degree and have an externally rotated lower extremity. Physical examination of the affected hip reveals a restriction of internal rotation, abduction, and flexion. Commonly, the examiner notes that as the affected hip is flexed, the thigh tends to rotate progressively into more external rotation with increased flexion (Fig. 698.14 ). Most patients complain of groin symptoms, but isolated thigh or knee pain is a common presentation from referred pain along the course of the obturator nerve. Missed or delayed diagnosis often occurs in children who present with knee pain and do not receive appropriate imaging of the hip. Patients with unstable SCFEs usually present in an urgent fashion. Children typically refuse to allow any range of motion of the hip; much like a hip fracture, the extremity is shortened, abducted, and externally rotated.

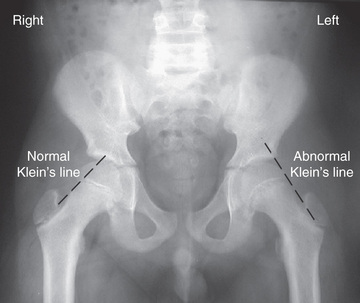

Diagnostic Studies

AP and frog-leg lateral radiographic views of both hips are usually the only imaging studies needed to make the diagnosis. Because approximately 25% of patients have a contralateral slip on initial presentation, it is critical that both hips be carefully evaluated by the treating physician. Radiographic findings include widening and irregularity of the physis, a decrease in epiphyseal height in the center of the acetabulum, a crescent-shaped area of increased density in the proximal portion of the femoral neck, and the “blanch sign of Steel” corresponding to the double density created from the anteriorly displaced femoral neck overlying the femoral head. In an unaffected patient, Klein's line, a straight line drawn along the superior cortex of the femoral neck on the AP radiograph, should intersect some portion of the lateral capital femoral epiphysis. With progressive displacement of the epiphysis, Klein's line no longer intersects the epiphysis (Fig. 698.15 ). Although some of these radiographic findings can be subtle, most diagnoses can be readily made on the frog-leg lateral view, which reveals the characteristic posterior and inferior displacement of the epiphysis in relation to the femoral neck (Fig. 698.16 ).

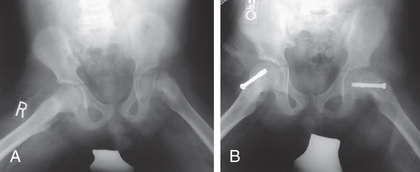

Treatment

Once the diagnosis is made, the patient should be admitted to the hospital immediately and placed on bed rest. Allowing the child to go home without definitive treatment increases the risk that a stable SCFE will become an unstable SCFE and that further displacement will occur. Children with atypical presentations (younger than 10 yr of age, thin body habitus) should have screening labs sent to rule out an underlying endocrinopathy.

The goal of treatment is to prevent further progression of the slip and to stabilize (i.e., close) the physis. Although various forms of treatment have been used in the past, including spica casting, the current gold standard for the treatment of SCFE is in situ pinning with a single large screw (Fig. 698.17 ). The term in situ implies that no attempt is made to reduce the displacement between the epiphysis and femoral neck because doing so increases the risk of osteonecrosis. Screws are typically placed percutaneously under fluoroscopic guidance. Postoperatively, most patients are allowed partial weight bearing with crutches for 4-6 wk, followed by a gradual return to normal activities. Patients should be monitored with serial radiographs to be sure that the physis is closing and that the slip is stable. After healing from the initial stabilization, patients with severe residual deformity may be candidates for proximal femoral osteotomy to correct the deformity, reduce impingement, and improve range of motion.

Because 20–40% of children will develop a contralateral SCFE at some point, many orthopedists advocate prophylactic pin fixation of the contralateral (normal) side in patients with a unilateral SCFE. The benefits of preventing a possible slip must be balanced with the risks of performing a potentially unnecessary surgery. Several recent studies have attempted to analyze decision models for prophylactic pinning, but controversy remains regarding the optimal course of treatment.

Complications

Osteonecrosis and chondrolysis are the 2 most serious complications of SCFE. Osteonecrosis, or avascular necrosis, usually occurs as a result of injury to the retinacular vessels. This can be caused by an initial force of injury, particularly in unstable slips, forced manipulation of an acute or unstable SCFE, compression from intracapsular hematoma, or as a direct injury during surgery. Partial forms of osteonecrosis can also appear following internal fixation; this can be caused by a disruption of the intraepiphyseal blood vessels. Chondrolysis, on the other hand, is an acute dissolution of articular cartilage in the hip. There are no clear causes of this complication, but it is believed to be associated with more severe slips, to occur more commonly among African Americans and girls, and to be associated with pins or screws protruding out of the femoral head.

Bibliography

Azzopardi T, Sharma S, Bennet GC. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in children aged less than 10 years. J Pediatr Orthop B . 2010;19:13–18.

Clement ND, Vats A, Duckworth AD, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: is it worth the risk and cost not to offer prophylactic fixation of the contralateral hip? Bone Joint J . 2015;97-B(10):1428–1434.

Loder RT, Dietz FR. What is the best evidence for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis? J Pediatr Orthop . 2012;32(Suppl 2):S158–S165.

Novais EN, Millis MB. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: prevalence, pathogenesis, and natural history. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2012;470(12):3432–3438.

Roaten J, Spence DD. Complications related to the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthop Clin North Am . 2016;47(2):405–413.

Souder CD, Boman JD, Wenger DR. The role of capital realignment versus in situ stabilization for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop . 2014;34(8):791–798.