Orthopedic Evaluation of the Child

Keith D. Baldwin, Lawrence Wells

A detailed history and thorough physical examination are critical to the evaluation of a child with an orthopedic problem. The child's family and acquaintances are important sources of information, especially in younger children and infants. Appropriate radiographic imaging and, occasionally, laboratory testing may be necessary to support the clinical diagnosis.

History

A comprehensive history should include details about the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods. Prenatal history should include maternal health issues: smoking, prenatal vitamins, illicit use of drugs or narcotics, alcohol consumption, diabetes, immunization status (including receipt of rubella vaccine), and sexually transmitted infections. The child's prenatal and perinatal history should include information about the length of pregnancy, length of labor, type of labor (induced or spontaneous), presentation of fetus, evidence of any fetal distress at delivery, requirement for supplemental oxygen following the delivery, birth length and weight, Apgar score, muscle tone at birth, feeding history, and period of hospitalization. In older infants and young children, evaluation of developmental milestones for posture, locomotion, dexterity, social activities, and speech are important. Specific orthopedic questions should focus on joint, muscular, appendicular, or axial skeleton complaints. Information regarding pain or other symptoms in any of these areas should be elicited (Table 693.1 ). The family history can give clues to heritable disorders. It also can forecast expectations of the child's future development and allow appropriate interventions as necessary.

Physical Examination

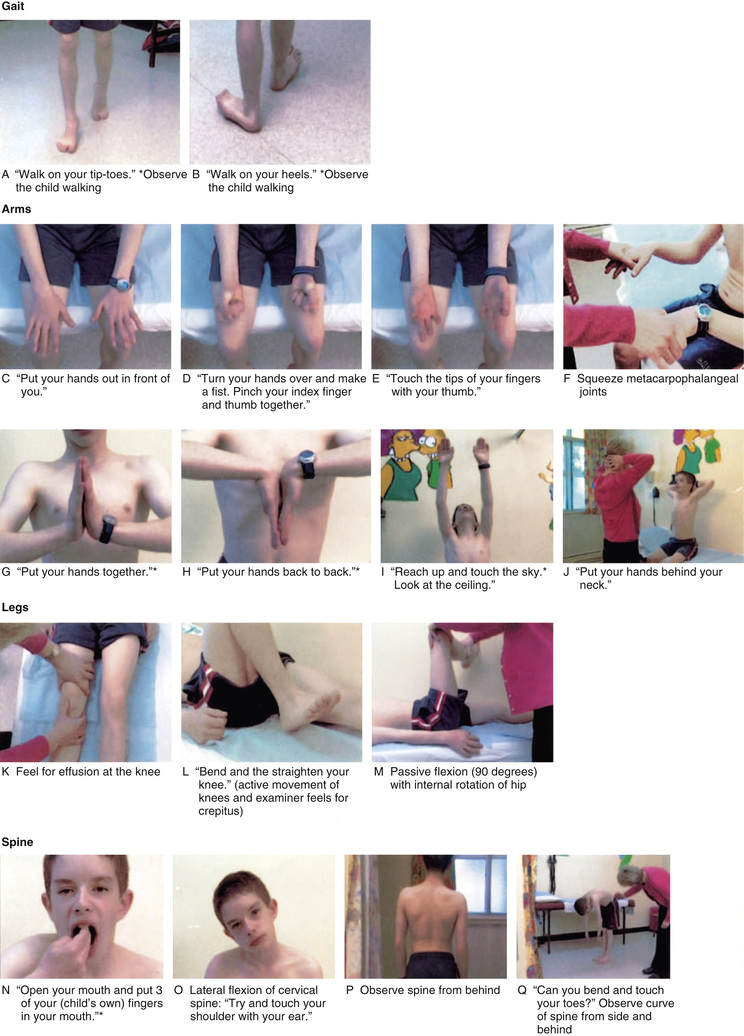

The orthopedic physical examination includes a thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system along with a comprehensive neurologic examination. The musculoskeletal examination includes inspection, palpation, and evaluation of motion, stability, and gait. A basic neurologic examination includes sensory examination, motor function, and reflexes. The orthopedic physical examination requires basic knowledge of anatomy of joint range of motion, alignment, and stability. Many common musculoskeletal disorders can be diagnosed by the history and physical examination alone. One screening tool that has been useful in adults has now been adapted and evaluated for use in children: the pediatric gait, arms, legs, spine (pGALS) test, the components of which are listed in Fig. 693.1 .

Inspection

Initial examination of the child begins with inspection. The clinician should use the guidelines listed in Table 693.2 during inspection.

Palpation

Palpation of the involved region should include assessment of local temperature and tenderness; assessment for a swelling or mass, spasticity or contracture, and bone or joint deformity; and evaluation of anatomic axis of limb and of limb lengths.

Contractures are a loss of mobility of a joint from congenital or acquired causes and are caused by periarticular soft tissue fibrosis or involvement of muscles crossing the joint. Congenital contractures are common in arthrogryposis (see Chapter 702 ). Spasticity is an abnormal increase in tone associated with hyperreflexia and is common in cerebral palsy.

Deformity of the bone or joint is an abnormal fixed shape or position from congenital or acquired causes. It is important to assess the type of deformity, its location, and degree of deformity upon clinical examination. It is also important to assess whether the deformity is fixed or can be passively or actively corrected, and whether there is any associated muscle spasm, local tenderness, or pain on motion. Classification of the deformity depends on the plane of deformity: varus (away from midline) or valgus (apex toward midline), or recurvatum (backward curvature) or flexion deformity (sagittal plane). In the axial skeleton, especially the spine, deformity can be defined as scoliosis, kyphosis, hyperlordosis, and kyphoscoliosis.

Range of Motion

Active and passive joint motion should be assessed, recorded, and compared with the opposite side. Objective evaluation should be done with a goniometer and recorded.

Vocabulary for direction of joint motion is as follows:

- Abduction: Away from the midline

- Adduction: Toward the midline

- Flexion: Movement of bending from the starting position

- Extension: Movement from bending to the starting position

- Supination: Rotating the forearm to face the palm upward

- Pronation: Rotating the forearm to face the palm downward

- Inversion: Turning the hindfoot inward

- Eversion: Turning the hindfoot outward

- Plantar flexion: Pointing the toes away from the body (toward the floor)

- Dorsiflexion: Pointing the toes toward the body (toward the ceiling)

- Internal rotation: Turning inward toward the axis of the body

- External rotation: Turning outward away from the axis of the body

Gait Assessment

Children typically begin walking between 8 and 16 mo of age. Early ambulation is characterized by short stride length, a fast cadence, and slow velocity with a wide-based stance. Gait cycle is a single sequence of functions that starts with heel strike, toe off, swing, and heel strike. The four events describe one gait cycle and include two phases: stance and swing. The stance phase is the period during which the foot is in contact with the ground. The swing phase is the portion of the gait cycle during which a limb is being advanced forward without ground contact. Normal gait is a symmetric and smooth process. Deviation from the norm indicates potential abnormality and should trigger investigation.

Neurologic maturation is necessary for the development of gait and the normal progression of developmental milestones. A child's gait changes with neurologic maturation. Infants normally walk with greater hip and knee flexion, flexed arms, and a wider base of gait than older children. As the neurologic system continues to develop in the cephalocaudal direction, the efficiency and smoothness of gait increase. The gait characteristics of a 7 yr old child are similar to those of an adult. When the neurologic system is abnormal (cerebral palsy), gait can be disturbed, exhibiting pathologic reflexes and abnormal movements.

Deviations from normal gait occur in a variety of orthopedic conditions. Disorders that result in muscle weakness (e.g., spina bifida, muscular dystrophy), spasticity (e.g., cerebral palsy), or contractures (e.g., arthrogryposis) lead to abnormalities in gait. Other causes of gait disturbances include limp, pain, torsional variations (in-toeing and out-toeing), toe walking, joint abnormalities, and leg-length discrepancy (Table 693.3 ).

Limping

A thorough history and clinical examination are the first steps toward early identification of the underlying problem causing a limp. Limping can be considered as either painful (antalgic) or painless, with the differential diagnosis ranging from benign to serious causes (septic hip, tumor). In a painful gait, the stance phase is shortened as the child decreases the time spent on the painful extremity. In a painless gait, which indicates underlying proximal muscle weakness or hip instability, the stance phase is equal between the involved and uninvolved sides, but the child leans or shifts the center of gravity over the involved extremity for balance. A bilateral disorder produces a waddling gait. Trendelenburg gait (i.e., trunk lists to the affected side with each step) is produced by weak abnormal hip abductors. When the patient stands on one foot, a Trendelenburg sign (i.e., sagging rather than rising of the unsupported buttock) can often be elicited when abductors are weak.

Disorders most commonly responsible for an abnormal gait generally vary based on the age of the patient. The differential diagnosis of limping varies based on age group (Table 693.4 ) or mechanism (Table 693.5 ). Neurologic disorders, especially spinal cord, muscle, or peripheral nerve disorders, can also produce limping and difficult walking. Antalgic gait is predominantly a result of trauma, infection, or pathologic fracture. Trendelenburg gait is generally caused by congenital, developmental, or muscular disorders. In some cases, limping also may be caused by nonskeletal causes such as testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, and appendicitis.

Table 693.4

Differential Diagnosis of Limping in Children

| AGE GROUP | DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Early walker: 1-3 yr of age |

Painful limp Painless limp |

| Child: 3-10 yr of age |

Painful limp Painless limp |

| Adolescent: 11 yr of age to maturity |

Painful limp Painless limp |

From Marcdante K, Kliegman R, eds. Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015.

Back Pain

Children frequently have a specific skeletal pathology as the cause of back pain. The most common causes of back pain in children are trauma, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and infection (see Chapter 699.5 ). Tumor and tumor-like lesions that cause back pain in children are likely to be missed unless a thorough clinical assessment and adequate workup are performed when required. Nonorthopedic causes of back pain include urinary tract infections, nephrolithiasis, and pneumonia.

Neurologic Evaluation

A careful neurologic evaluation is a part of every pediatric musculoskeletal examination (see Chapter 608 ). The assessment should include evaluation of developmental milestones, muscle strength, sensory assessment, muscle tone, and deep tendon reflexes. The neurologic evaluation should also assess the spine and identify any deformity, such as scoliosis and kyphosis, or abnormal spinal mobility. The hips and feet should also be examined specifically, along with torsional abnormalities of the lower extremity, which are vastly more common in the neurologically involved population. Specific peripheral nerve examinations may be necessary.

As the nervous system matures, the developing cerebral cortex normally inhibits rudimentary reflexes that are often present at birth (see Chapter 608 ). Therefore persistence of these reflexes can indicate neurologic abnormality. The most commonly performed deep tendon reflex tests include biceps, triceps, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius and soleus tendons. Upper motor neuron signs should also be noted. The Ashworth scale is often used to grade spasticity (Table 693.6 ). Upper-extremity motor control is often graded, and these grades are useful both diagnostically and prognostically. Passive range of motion should be assessed to determine contractures (Table 693.7 ). Localized or diffuse weakness must be determined and documented. A thorough assessment and grading of muscle strength is mandatory in all cases of neuromuscular disorders.

Table 693.6

Table 693.7

Radiographic Assessment

Plain radiographs are the first step in evaluation of most musculoskeletal disorders. Advanced imaging includes special procedures such as MRI, nuclear bone scans, ultrasonography, CT, and positron emission tomography. Rapid STIR MRI is a valuable screening test if a specific location is not well defined.

Plain Radiographs

Routine radiographs are the first step and consist of anteroposterior and lateral views of the involved area with one joint above and below. Comparison views of the opposite side, if uninvolved, may be helpful in difficult situations but are not always necessary. It is important for the clinician to be aware of normal radiographic variants of the immature skeleton. Several synchondroses may be mistaken for fractures. A patient with “normal” plain radiographic appearance but having persistent pain or symptoms might need to be evaluated further with additional imaging studies.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is useful to evaluate suspected fluid-filled lesions such as popliteal cyst and hip joint effusions. Major indications for ultrasonography are fetal studies of the extremities and spine, including detection of congenital anomalies like spondylocostal dysostosis, fractures suggesting osteogenesis imperfecta, developmental dysplasia of the hip, joint effusions, occult neonatal spinal dysraphism, foreign bodies in soft tissues, and popliteal cysts of the knee.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for defining the exact anatomic extent of most musculoskeletal lesions (particularly if the structure is soft tissue). MRI avoids ionizing radiation, and doing so does not produce any known harmful effects. It produces excellent anatomic images of the musculoskeletal system, including the soft tissue, bone marrow cavity, spinal cord, and brain. It is especially useful for defining the extent of soft tissue lesions, infections, and injuries. Tissue planes are well delineated, allowing more accurate assessment of tumor invasion into adjacent structures. Cartilage structures can be visualized (articular cartilage of the knee can be distinguished from the fibrocartilage of the meniscus). MRI is also helpful in visualizing unossified joints in the pediatric population, including the shoulders, elbows, and hips of young infants.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography has largely replaced routine angiography in the preoperative assessment of vascular lesions and bone tumors. Magnetic resonance angiography provides good visualization of peripheral vascular branches and tumor neovascularity in patients with primary bone tumors.

Computed Tomography

CT has enhanced the evaluation of multiple musculoskeletal disorders. Coronal, sagittal, and axial imaging is possible with CT, including 3-dimensional reconstructions that can be beneficial in evaluating complex lesions of the axial and appendicular skeleton. It allows visualization of the detailed bone anatomy and the relationship of bones to contiguous structures. CT is useful to readily evaluate tarsal coalition, accessory navicular bone, infection, growth plate arrest, osteoid osteoma, pseudoarthrosis, bone and soft tissue tumors, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis. CT is superior to MRI for assessing bone involvement and cortical destruction (even subtle changes), including calcification or ossification and fracture (particularly if displacement of an articular fracture is suspected).

Nuclear Medicine Imaging

A bone scan displays physiologic information rather than pure anatomy and relies on the emission of energy from the nucleotide injected into the patient. Indications include early septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, avascular necrosis, tumors (osteoid osteoma), metastatic lesions, occult and stress fractures, and cases of child abuse.

Total-body radionuclide scan (technetium-99) is useful to identify bony lesions, inflammatory tumors, and stress fractures. Tumor vascularity can also be inferred from the flow phase and the blood pool images. Gallium or indium scans have high sensitivity for local infections. Thallium-201 chloride scintiscans have >90% sensitivity and between 80% and 90% accuracy in detecting malignant bone or soft tissue tumors. MRI has supplanted nuclear medicine imaging in many circumstances.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory tests are occasionally necessary in the evaluation of a child with musculoskeletal disorder. These may include a complete blood cell count; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C-reactive protein assay; Lyme titers; and blood, wound, joint, periosteum, or bone cultures for infectious conditions such as septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and human leukocyte antigen B27 may be necessary for children with suspected rheumatologic disorders. Creatine kinase, aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase, and dystrophin testing are indicated in children with suspected disorders of striated muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy.