Common Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability in children older than 1 yr of age (see Chapter 13 ). Several factors make fractures of the immature skeleton different from those involving the mature skeleton. The anatomy, biomechanics, and physiology of the pediatric skeletal system differ from those of adults, resulting in different fracture patterns (Fig. 703.1 ), diagnostic challenges, and management techniques. Children have a high functional demand and expectations, while carrying concerns regarding remaining skeletal growth and development.

Epiphyseal lines, rarefaction, dense growth lines, congenital fractures, and pseudofractures appear on radiographs, which make it challenging to identify and differentiate an acute fracture. Although most fractures in children heal well, some fractures terminate disastrously if handled with insufficient expertise. The differences in the pediatric skeletal system predispose children to injuries different from those of adults. Important differences are the presence of periosseous cartilage, physes, and a thicker, stronger, more osteogenic periosteum that produces new bone, called callus , more rapidly and in greater amounts. The pediatric bone is less dense and more porous. The low density is from lower mineral content and the increased porosity is the result of an increased number of haversian canals and vascular channels. These differences result in a comparatively lower modulus of elasticity and lower bending strength. The bone in children can fail either in tension or in compression; because the fracture lines do not propagate as in adults, there is less chance of comminuted fractures. Hence, pediatric bone can crush, splinter, and break incompletely (e.g., buckle fracture, greenstick fracture), as opposed to adult bone which generally breaks like glass and may comminute.

A common teaching is that joint injuries, dislocation, and ligament disruptions are infrequent in children. Damage to a contiguous physis is more likely. Although this is generally true, MRI studies show that ligament damage in ankle injuries may not be as unusual as once thought. Interdigitating mammillary bodies and the perichondrial ring enhance the strength of the physes. Biomechanically, the physes are not as strong as the ligaments or metaphyseal bone. The physis is most resistant to traction and least resistant to torsional forces. The periosteum is loosely attached to the shaft of bone and adheres densely to the physeal periphery. The periosteum is usually injured in all fractures, but it is less likely to have complete circumferential rupture, because of its loose attachment to the shaft. This intact hinge or sleeve of periosteum lessens the extent of fracture displacement and assists in reduction and maintenance of fracture reduction. The thick periosteum can also act as an impediment to closed reduction, particularly if the fracture has penetrated the periosteum, or in reduction of a displaced growth plate.

Unique Characteristics of Pediatric Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Fracture Remodeling

Remodeling is the third and final phase in the biology of fracture healing; it is preceded by the inflammatory and reparative phases. This occurs from a combination of appositional bone deposition on the concavity of deformity, resorption on the convexity, and asymmetric physeal growth. Thus reduction accuracy is somewhat less important than it is in adults (exceptions include intra-articular fractures) (Fig. 703.2 ). The three major factors that have a bearing on the potential for angular correction are skeletal age, distance to the physis, and orientation to the joint axis. The rotational deformity and angular deformity not in the axis of the joint motion have less potential for remodeling. Remodeling is best when the fracture occurs close to the physis, the child has more years of growth remaining, has less deformity to remodel, and is adjacent to a rapidly growing physis (e.g., the proximal humerus or distal radius). Remodeling typically occurs over a several months period following the fracture until skeletal maturity. Generally, skeletal maturity is reached in postmenarchal girls between 13 and 15 yr of age, and in boys between 15 and 17 yr of age.

Overgrowth

Physeal stimulation from the hyperemia associated with fracture healing may also cause overgrowth. It is usually more prominent in lower extremity long bones such as the femur. The growth acceleration is usually present for 6 mo to 1 yr following the injury. Femoral fractures in children younger than 10 yr of age may overgrow up to 1-3 cm. If external fixation or casting is employed, bayonet apposition of bone may be preferred for younger children to compensate for the expected overgrowth. This overgrowth phenomenon will result in equal or near equal limb lengths at the conclusion of fracture remodeling if the fracture shortens less than 2 cm. After 10 yr of age, overgrowth does not tend to occur, and anatomic alignment is recommended. In physeal injuries, growth stimulation is associated with use of implants or fixation hardware that can cause stimulus for longitudinal growth.

Progressive Deformity

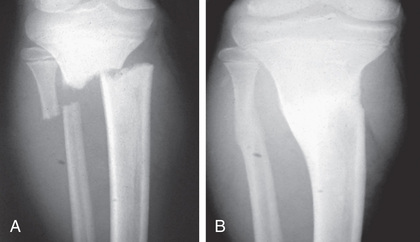

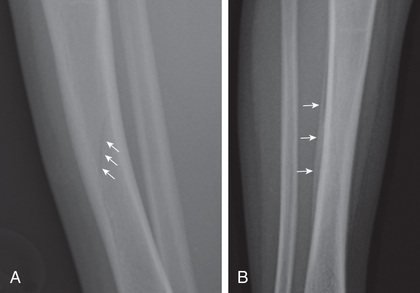

Injuries to the physes can be complicated by permanent or temporary growth arrest, leading to progressive limb deformity. The most common cause is complete or partial closure of the growth plate. This can occur in any long bone but is particularly seen in fractures involving the distal ulna, distal femur, and proximal tibia growth plates. An MRI is helpful for early diagnosis of growth arrest, as well as measurement of percent of physeal closure after such an injury. Harris growth arrest lines may be observed in the setting of asymmetric growth and will point toward the area of growth arrest (Fig. 703.3 ). If these lines are parallel to the physis, this finding indicates that the growth plate is healthy. As a consequence of growth arrest, angular deformity or shortening, or both, can occur. The partial arrest may be peripheral, central, or combined. The magnitude of deformity depends on the specific physis involved, the degree of involvement, and the amount of growth remaining.

Rapid Healing

Children's fractures heal more quickly than adults as a result of children's growth potential and thicker, more active periosteum. As children approach adolescence and maturity, the rate of healing slows and becomes similar to that of an adult.

Bibliography

Endele D, Jung C, Bauer G, et al. Value of MRI in diagnosing injuries after ankle sprains in children. Foot Ankle Int . 2012;33(12):1063–1068.

Flynn JM, Skagggs DL, Waters PM. Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures. Children, ed . Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2015. 8th . .

Gorter EA, Oostdijk W, Felius A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in pediatric fracture patients: prevalence, risk factors, and vitamin D supplementation. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol . 2016;8(4):445–451.

Larsen MC, Bohm KC, Rizkala AR, Ward CM. Outcomes of nonoperative treatment of Salter-harris II distal radius fractures: a systematic review. Hand . 2016;11(1):29–35.

Olney RC, Mazur JM, Pike LM, et al. Healthy children with frequent fractures: how much evaluation is needed? Pediatrics . 2008;121:890–897.

Poolman RW. Adjunctive non-invasive ways of healing bone fractures. BMJ . 2009;338:611–612.

Wren TAL, Shepherd JA, Kalkwarf HJ, et al. Racial disparity in fracture risk between white and nonwhite children in the United States. J Pediatr . 2012;161:1035–1040.

Pediatric Fracture Patterns

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

The different pediatric fracture patterns are the reflection of a child's characteristic skeletal system. The majority of pediatric fractures can be managed by closed methods and heal well.

Plastic Deformation

Plastic deformation is unique to children. It is most commonly seen in the forearm and occasionally the fibula. The fracture results from a force that produces microscopic failure on the tensile side of bone and does not propagate to the concave side (Fig. 703.4 ). The concave side of bone also shows evidence of microscopic failure in compression. The bone is angulated beyond its elastic limit, but the energy is insufficient to produce a fracture. Thus no fracture line is visible radiographically (Fig. 703.5 ). While the plastic deformation is permanent, it is important to remember that children have great remodeling capability, for example, a 20-degree bend in the ulna of a 4 yr old child is expected to correct completely with growth. These findings inform “acceptability” of fracture alignment.

Buckle or Torus Fracture

This fracture represents a failure in compression of the bone, usually occurring at the junction of the metaphysis and diaphysis. The distal radius is the most common location, but it may occur in other areas as well (Fig. 703.6 ). This injury is referred to as a torus fracture because of its similarity to the raised band around the base of a classic Greek column. They are inherently stable, usually associated with an acceptable amount of angulation, and heal in 3-4 wk with simple immobilization.

Greenstick Fracture

These fractures occur when the bone is bent, and there is failure on the tensile (convex) side of the bone. The fracture line does not propagate to the concave side of the bone (Fig. 703.7 ). The concave side shows evidence of microscopic failure with plastic deformation. If the angulation at the fracture site is unacceptable, it is usually necessary to break the bone on the concave side because the plastic deformation recoils it back to the deformed position. It is important to distinguish this unicortical fracture pattern from buckle fractures, as these fractures are at greater risk of loss of reduction and often need a longer period of immobilization.

Complete Fractures

Fractures that propagate completely through the bone are called complete fractures . These fractures may be classified as spiral, transverse, or oblique, depending on the direction and shape of the fracture lines. A rotational force is responsible for spiral fractures, and most of these fractures are stable and heal quickly due to the large surface area; however, spiral fractures as a result of a high-energy trauma may present with shortening of the bone and loss of alignment. Oblique fractures are defined by a 30-degree angle to the axis of the bone and are often unstable. The transverse fracture pattern occurs following a 3-point bending force and are amenable to successful reduction by using the intact periosteum from the concave side as a hinge.

Epiphyseal Fractures

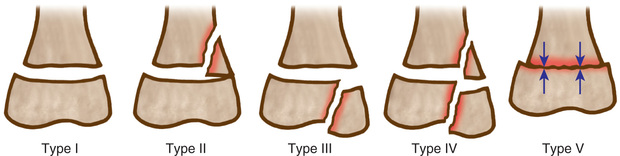

Fractures involving the epiphysis often involve the growth plate; therefore there is a potential for growth disturbance leading to deformity or discrepancy, and hence long-term observation is necessary. The distal radial physis is the most commonly injured physis. Salter and Harris (SH) classified epiphyseal injuries into five groups (Table 703.1 and Fig. 703.8 ). This classification helps to predict the outcome of the injury and offers guidelines in formulating treatment. Most SH type I and II fractures usually can be managed by closed reduction techniques and do not require perfect alignment, because they tend to remodel with growth, as long as there is enough growth remaining. One classic exception is the distal femur, where SH type II fractures are unstable and require anatomic reduction with adequate fixation. The SH type III and IV epiphyseal fractures involve the articular surface and require anatomic alignment (<2 mm displacement) to prevent any step off and realign the growth cells of the physis. SH type V fractures are usually not diagnosed initially. They manifest in the future with growth disturbance. Other injuries to the epiphysis are avulsion injuries of the tibial spine and muscle attachments to the pelvis. Osteochondral fractures are also defined as physeal injuries that do not involve the growth plate.

Table 703.1

Child Abuse

(See also Chapter 16 .)

Fractures are the second most common manifestation of child abuse after skin injury (bruises, burns/abrasions). The orthopedic surgeon sees 30–50% of all nonaccidental traumas. Child abuse should be suspected in nonambulatory children with lower-extremity long-bone fractures. No fracture pattern or types are pathognomonic for child abuse; any type of fracture can result from nonaccidental trauma. Transverse fractures in long bones are the most prevalent, while corner fractures in the metaphysis are the most classic. The fractures that suggest nonaccidental injury include femur fractures in nonambulatory children (younger than age18 mo), distal femoral metaphyseal corner fractures, posterior rib fractures, scapular spinous process fractures, and proximal humeral fractures. Fractures that were unwitnessed or carry a suspicious or changing story or delayed presentation also warrant investigation. A full skeletal survey (as opposed to a “babygram”) is essential in every suspected case of child abuse, because it can demonstrate other fractures in different stages of healing. Radiographically, some systemic diseases mimic signs of child abuse, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis, Caffey disease, and fatigue fractures. Many hospitals have a multidisciplinary team to evaluate and treat patients who are victims of child abuse; these teams are critical to engage early and preferably in the emergency room setting, as difficulty arises managing these emotionally charged issues in a clinic setting. Dedicated teams are most well equipped to identify and manage these issues. It is mandatory to report these cases to social welfare agencies.

Bibliography

Baldwin K, Pandya NK, Wolfgruber H, et al. Femur fractures in the pediatric population: abuse or accidental trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2011;469(3):798–804.

Baldwin KD, Scherl SA. Instr Course Lect . 2013;62:399–403.

Blatz AM, Gillespie CW, Katcher A, et al. Factors associated with nonaccidental trauma evaluation among patients below 36 months old presenting with femur fractures at a Level-1 pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Orthop . 2017.

Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med . 2009;54:553–560.

ed 4. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2009. Green NE, Swiontkowski MF. Skeletal trauma in children . vol 3.

Jadhav SP, Swischuk LE. Commonly missed subtle skeletal injuries in children: a pictorial review. Emerg Radiol . 2008;15(6):391–398.

Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ . 2008;337:a1518.

Leaman LA, Hennrikus WL, Bresnahan JJ. Identifying non-accidental fractures in children aged< 2 years. J Child Orthop . 2016;10(4):335–341.

Olney RC, Mazur JM, Pike LM, et al. Healthy children with frequent fractures: how much evaluation is needed? Pediatrics . 2008;121:890–897.

Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Wolfgruber H, et al. Child abuse and orthopaedic injury patterns: analysis at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Orthop . 2009;29(6):618–625.

Poolman RW. Adjunctive non-invasive ways of healing bone fractures. BMJ . 2009;338:611–612.

Williams KG, Smith G, Luhmann SJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cast versus splint for distal radial buckle fracture: an evaluation of satisfaction, convenience, and preference. Pediatr Emerg Care . 2013;29(5):555–559.

Upper Extremity Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Phalangeal Fractures

Finger fractures are among the most common fracture types in children. The different phalangeal fracture patterns in children include physeal, diaphyseal, and tuft fractures. The mechanism of injury varies from a direct blow to the finger to a finger trapped in a door (see Chapter 701 ). Crush injuries of the distal phalanx manifest with severe comminution of the underlying bone (tuft fracture), disruption of the nail bed, and significant soft tissue injury. These injuries are best managed with irrigation, tetanus prophylaxis, and antibiotic prophylaxis; antibiotics effective against staphylococci (e.g., first-generation cephalosporins) are usually appropriate, although the mechanism of injury may warrant other antibiotic coverage. Radiographs in patients with fingertip crush injuries should be scrutinized for evidence of a Seymour's fracture, an open physeal fracture of the distal phalanx with possible interposition of the nail matrix. These patients are at higher risk of nail plate deformity and infection without surgical treatment. A mallet finger deformity is the inability to extend the distal portion of the digit and is caused by a hyperflexion injury. It represents an avulsion fracture of the physis of the distal phalanx. The treatment is continuous splinting the digit in extension for 6 wk. The physeal injuries of the proximal and middle phalanx are similarly treated with cast immobilization. The most common physeal finger fracture results from an abduction injury to the small finger. These fractures often require a closed reduction prior to immobilization. Diaphyseal fractures may be oblique, spiral, or transverse in fracture geometry. They are assessed for angular and rotational deformity with the finger in flexion. The patient should be asked to make a fist. All fingers should point toward the scaphoid. If they do not, a malrotation is suspected, even in the presence of x-rays which appear minimally displaced. Malrotation or angular deformity may require correction to avoid finger cross-over and to optimize hand function. These deformities are corrected with closed reduction, and if unstable, they need stabilization.

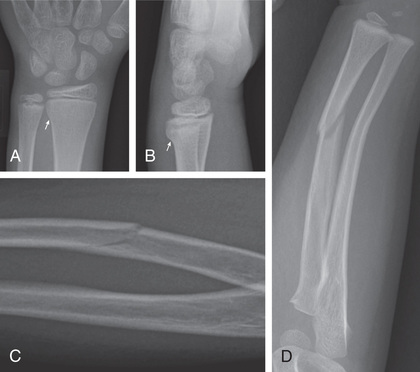

Forearm Fractures

Fractures of the wrist and forearm are very common fractures in children, accounting for nearly half of all fractures seen in the skeletally immature. The most common mechanism of injury is a fall on the outstretched hand. Eighty percent of forearm fractures involve the distal radius and ulna, 15% involve the middle third, and the rest are rare fractures of the proximal third of the radius or ulnar shaft (Fig. 703.9 ). Most forearm fractures in younger children are torus or greenstick fractures. The torus fracture is an impacted fracture, and there is minimal soft tissue swelling or hemorrhage. They are best treated in a short arm (below the elbow) cast and usually heal within 3-4 wk. Wrist buckle fractures have also been successfully treated with a removable splint. Impacted greenstick fractures of the forearm tend to be intrinsically stable (no cortical disruption) and may be managed with a soft bandage rather than casting.

Diaphyseal fractures can be more difficult to treat because the limits of acceptable reduction are much more stringent than for distal radial fractures. A significant malunion of a forearm diaphyseal fracture can lead to a permanent loss of pronation and supination, leading to functional difficulties. This is particularly true with malrotation of the fragments. Diaphyseal fractures are vulnerable to rotational malalignment due to insertion of the pronator muscle groups and the supinator groups. This malalignment is particularly hard to assess because the deformity is in the axial plane and is evaluated with anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs (Fig. 703.10 ). The physical examination focuses on soft tissue injuries and ruling out any neurovascular involvement. The AP and lateral radiographs of the forearm and wrist confirm the diagnosis. Displaced and angulated fractures require manipulative closed reduction under general anesthesia or conscious sedation. They are immobilized in an above-elbow cast for at least 6 wk. Both bone fractures in older children and adolescents (>10 yr of age) must be followed carefully as they often lose reduction. Loss of reduction and unstable fractures require open reduction and internal fixation. Fixation may be with intramedullary nails or plate fixation, which yield similar results.

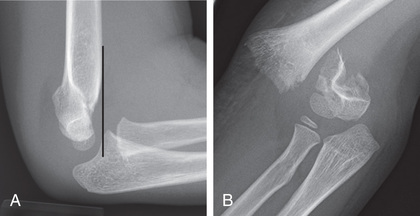

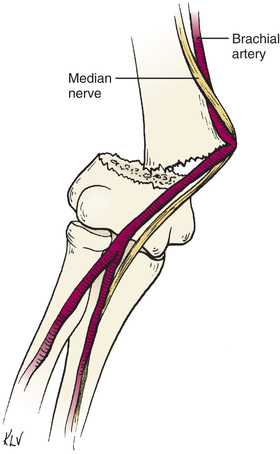

Distal Humeral Fractures

Fractures around the elbow receive more attention because more aggressive management is needed to achieve a good result. Many injuries are intraarticular, involve the physeal cartilage, and can result in malunion or nonunion. As the distal humerus develops from a series of ossification centers, these ossification centers can be mistaken for fractures by inexperienced eyes. Careful radiographic evaluation is an essential part of diagnosing and managing distal humeral injuries. It is important to remember that the distal humerus is only responsible for 20% of the growth of the humerus; therefore there is very low potential for remodeling. Observation of soft tissue swelling and tenderness is critical to pick up subtle injuries. Common fractures include separation of the distal humeral epiphysis (transcondylar fracture), supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus, and epiphyseal fractures of the lateral condyle or medial epicondyle. The mechanism of injury is a fall on an outstretched arm. The physical examination includes noting the location and extent of soft tissue swelling, ruling out any neurovascular injury, specifically anterior interosseous nerve involvement or evidence of compartment syndrome. A transphyseal fracture in a very young child, who does not have the reflex to keep the arm outstretched during to break a fall, should raise suspicion of child abuse. AP and lateral radiographs of the involved extremity are necessary for the diagnosis. If the fracture is not visible, but there is an altered relationship between the humerus and the radius and ulna or the presence of a posterior fat pad sign, a transcondylar fracture or an occult fracture should be suspected (Fig. 703.11 ). Imaging studies such as oblique radiographs, CT, MRI, and ultrasonography may be required for further confirmation. Displaced supracondylar fractures may be associated with concomitant neurovascular injury (Fig. 703.12 ) or, rarely, a compartment syndrome. Ulnar nerve injury is identified by decreased sensation over the cutaneous innervation of the lateral aspects of the hand as well as a motor deficit of abduction and adduction. Neurologic injury may also appear in the postoperative period. Careful neurologic examination of the hand before and after is needed to document and treat nerve injury. Most nerve injuries associated with displaced supracondylar fractures are neuropraxias and will resolve in several months.

In general, distal humeral fractures need restoration of anatomic alignment. This is necessary to prevent deformity and to allow for normal growth and development. Closed reduction alone, or in association with percutaneous fixation, is the preferred method. Open reduction is indicated for fractures that cannot be reduced by closed methods, fractures with vascular compromise following closed reduction, open fractures, or interarticular fractures, particularly in older children. Inadequate reductions can lead to loss of motion, cubitus varus, cubitus valgus, and rare nonunion or elbow instability. Elbow stiffness is not as common as in adult fractures but may occur with fractures which are severe or intraarticular.

Proximal Humerus Fractures

Fractures of the proximal humerus account for <5% of fractures in children. They usually result from a fall onto an outstretched arm, or direct trauma. The fracture pattern tends to vary with the age group. Physeal and metaphyseal fractures are both common. Among physeal fractures of the proximal humerus, children younger than 5 yr of age have an SH I injury, those 5-10 yr of age have metaphyseal fractures, and children older than 11 yr of age have SH II injury. Examination includes a thorough neurologic evaluation, especially of the axillary nerve. The diagnosis is made on AP radiographs of the shoulder. An axillary view is obtained to rule out any dislocation, and to assess angular deformity in an orthogonal plane. Many children are too uncomfortable to tolerate this view. In this case, a Velpeau axillary can be obtained while the arm remains in a sling. SH I injuries do not require reduction because they have excellent remodeling capacity, and simple immobilization in a sling for 2-3 wk is sufficient. Metaphyseal fractures usually do not need reduction unless the angulation is >50 degrees. In general, sling immobilization is all that is required. SH II fractures with <30 degrees of angulation and <50% displacement are managed in a sling. Displaced fractures are treated with closed reduction and further stabilization if unstable. Occasionally, open reduction is required because of button-holing of the fracture spike through the deltoid or interposition of the tendon of biceps. The majority of longitudinal growth (80%) of the limb comes from the proximal humeral physis. Additionally, the glenohumeral joint is capable of a large amount of motion. As such, this area is extremely tolerant to deformity. Indications for open reduction are rare. However, as adolescents approach adulthood, these fractures will remodel less.

Clavicular Fractures

Neonatal fractures occur as a result of direct trauma during birth, most often through a narrow pelvis or following shoulder dystocia. They can be missed initially and can appear with pseudoparalysis. Childhood fractures are usually the result of a fall on the affected shoulder or direct trauma to the clavicle. The most common site for fracture is the junction of the middle and lateral 3rd clavicle. Tenderness over the clavicle will make the diagnosis. A thorough neurovascular examination is important to diagnose any associated brachial plexus injury. Biceps function is important to assess, as it is a prognostic indicator for future function.

An AP radiograph of the clavicle demonstrates the fracture and can show overlap of the fragments. Physeal injuries occur through the medial or lateral growth plate and are sometimes difficult to differentiate from dislocations of the acromioclavicular or sternoclavicular joint. Further imaging such as a CT scan may be necessary to further define the injury. Posterior medial clavicular physeal injuries are particularly problematic due to their proximity to the great vessels and the trachea. Closed versus open reduction with a cardiac/thoracic team on standby is necessary. This can be delayed if there is no sign of vascular or respiratory compromise.

The treatment of most clavicle fractures consists of an application of a figure-of-eight clavicle strap or a simple sling. A figure-of-eight strap will extend the shoulders and minimize the amount of overlap of the fracture fragments. Evidence exists for adults—that fractures that are shortened or displaced result in strength loss of the shoulder without anatomic reduction and fixation. Many centers are extending that indication to older adolescents, although the data are currently not as strong as for adults. If a fracture is tenting the skin, or open or resulting in neurovascular compromise, surgery is indicated. The physeal fractures are treated with simple sling immobilization without any reduction attempt. Often, anatomic alignment is not achieved, nor is it necessary. The fractures heal rapidly usually in 3-6 wk. A palpable mass of callus is usually visible in thin children. This remodels satisfactorily in 6-12 mo. Complete restoration of shoulder motion and function is uniformly achieved.

Bibliography

Appleboam A, Reuben AD, Benger JR, et al. Elbow extension test to rule out elbow fracture: multicentre, prospective validation and observational study of diagnostic accuracy in adults and children. BMJ . 2009;338:31–34.

Baldwin K, Morrison MJ 3rd, Tomlinson LA, et al. Both bone forearm fractures in children and adolescents, which fixation strategy is superior–plates or nails? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Orthop Trauma . 2014;28(1):e8–e14.

Crawford SN, Lee LS, Izuka BH. Closed treatment of overriding distal radial fractures without reduction in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2012;94(3):246–252.

Edmonds EW. How displaced are “nondisplaced” fractures of the medial humeral epicondyle in children? Results of a three-dimensional computed tomography analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2010;92(17):2785–2791.

ed 4. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2009. Green NE, Swiontkowski MF. Skeletal trauma in children . vol 3.

Koelink E, Schuh S, Howard A, et al. Primary care physician follow-up of distal radius buckle fractures. Pediatrics . 2016;137(1):e21052262.

Kropman RHJ, Bemelman M, Segers MJM, et al. Treatment of compacted greenstick forearm fractures in children using bandage or cast therapy: a prospective randomized trial. J Trauma . 2010;68:425–428.

Ladenhauf HN, Schaffert M, Bauer J. The displaced supracondylar humerus fracture: indications for surgery and surgical options: a 2014 update. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2014;26:64–69.

Pathy R, Dodwell ER. Medial epicondyle fractures in children. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2015;27:58–66.

Plint AC, Perry JJ, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of removable splinting versus casting for wrist buckle fractures in children. Pediatrics . 2006;117(3):691–697.

Rangan A, Handoll H, Brealy S, et al. Surgical vs nonsurgical treatment of adults with displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. JAMA . 2015;313(10):1037–1046.

Runyon RS, Doyle SM. When is it ok to use a splint versus cast and what remodeling can one expect for common pediatric forearm fractures. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:46–54.

Soto F, Fiesseler F, Morales J, et al. Presentation, evaluation, and treatment of clavicle fractures in preschool children presenting to an emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care . 2009;25:744–747.

Lower Extremity Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Hip Fracture

Hip fractures in children account for <1% of all children's fractures. These injuries result from high-energy trauma and can be associated to injury to the chest, head, or abdomen. Treatment of hip fractures in children entails a complication rate of up to 60%, an overall avascular necrosis rate of 50%, and a malunion rate of up to 30%. The unique blood supply to the femoral head accounts for the high rate of avascular necrosis. Fractures are classified by the Delbet classification as transphyseal separations, transcervical fractures, cervicotrochanteric fractures, and intertrochanteric fractures. The management principle includes urgent anatomic reduction (either open or closed), stable internal fixation (avoiding the physis if possible), and spica casting if the child is younger. Urgent management has been associated with a lower rate of avascular necrosis and superior overall outcomes. Capsular decompression also has been advocated as decreasing overall pressure on the epiphyseal vessels and has been demonstrated experimentally. The clinical results have been mixed.

Femoral Shaft Fractures

Fractures of the femur in children are common. All age groups, from early childhood to adolescence, can be affected. The mechanism of injury varies from low-energy twisting type injuries to high-velocity injuries in vehicular accidents. Femur fractures in children younger than age 2 yr should raise the concern for child abuse. A thorough physical examination is necessary to rule out other injuries and assess the neurovascular status. In the case of high-energy trauma, any signs of hemodynamic instability should prompt the examiner to look for other sources of bleeding. AP and lateral radiographs of the femur demonstrate the fracture. An AP radiograph of the pelvis is obtained to rule out any associated pelvic fracture. Treatment of shaft fractures varies with the age group, as described in Table 703.2 .

Table 703.2

Femoral Shaft Fracture: Treatment Options by Age

| TREATMENT OPTIONS | 0-2 YR | 3-5 YR | 6-10 YR | >11 YR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spica cast | x | x | ||

| Traction and spica cast | x | x | x | |

| Intramedullary rod | x | x | x | |

| External fixator | x* | x* | x* | |

| Screw or plate | x | x | x |

* Open fracture.

Modified from Wells L: Trauma related to the lower extremity. In Dormans JP, editor: Pediatric orthopaedics: core knowledge in orthopaedics , Philadelphia, 2005, Mosby, p. 93.

Proximal Tibia Fractures

Proximal tibia fractures can be physeal injuries, metaphyseal injuries, or avulsion injuries of the tibial spine or tubercle. Physeal injuries can be either isolated or as part of tibial tubercle fracture. If the distal segment is displaced posteriorly the trifurcation of the popliteal vessels may be involved. Careful neurovascular examination is warranted both pre- and postreduction. Anatomic reduction and pin fixation is preferred with unstable fractures or displaced SH III or IV fractures.

Proximal tibial metaphyseal fractures, or the so-called cozen fracture, are most common in the 3-6 yr old age group. They may result in a late valgus deformity even if anatomically reduced. This deformity tends to remodel within 1-2 yr but can cause great distress to parents and treating clinicians.

Tibial eminence fractures are fractures of the bony prominence that is the attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament. The mechanism of injury is similar to an anterior cruciate ligament tear in an adult. Displaced fractures require surgical reduction and fixation. This may be done either open or arthroscopically.

Tibial tubercle fractures are common in patients with Osgood-Schlatter syndrome. Care must be taken to observe for compartment syndrome as the injury is associated with injury of the recurrent anterior tibial artery. The injury may be treated nonoperatively if the fracture is displaced <2 mm and the patient has no extensor lag (rare). Open reduction and internal fixation is preferred otherwise.

Tibia and Fibula Shaft Fractures

The tibia is the most commonly fractured bone of the lower limb in children. This fracture generally results from a direct injury. Most tibial fractures are associated with a fibular fracture, and the mean age of presentation is 8 yr. The child has pain, swelling, and deformity of the affected leg and is unable to bear weight. Distal neurovascular examination is important in assessment. The AP and lateral radiographs should include the knee and ankle. Closed reduction and immobilization are the standard method of treatment. Most fractures heal well, and children usually have excellent results. Open fractures need to undergo irrigation and debridement, and antibiotic treatment. The tibia is a subcutaneous bone. Severe soft tissue loss may necessitate plastic surgery consultation. Definitive external fixation versus internal fixation and simultaneous soft tissue coverage are alternate treatment strategies to minimize infection. Tibia fractures are associated with compartment syndrome. Vigilance is necessary to avoid disastrous outcomes in the setting of missed compartment syndrome. Emergent fasciotomy is indicated as soon as compartment syndrome is diagnosed. Several return trips to the operating room are often necessary to close, versus cover, the fasciotomy wounds.

Toddler Fracture

Toddler fractures occur in young ambulatory children. The age range for this fracture is typically from around 1-4 yr (Fig. 703.13 ). The injury often occurs after a seemingly harmless twist or fall and is often unwitnessed. It is a result of a torsional injury. The children in this age group are usually unable to articulate the mechanism of injury clearly or to describe the area of injury well. The radiographs may show no fracture; the diagnosis is made by physical examination. The classic symptom is refusal to bear weight, which can manifest as pulling up the affected extremity or florid display of protest. The other common sign is point tenderness at the fracture site. The AP and lateral views of the tibia-fibula might show a nondisplaced spiral fracture of the distal tibial metaphysis. An oblique view is often helpful because the fracture line may be visible in only one of the three views. Often the fracture line is not visualized until 2-3 wk later, when periosteal reaction and resorption at fracture site allow better visualization. Inflammatory markers may be ordered to rule out infectious processes if the diagnosis is in doubt. Bone scans were employed in the past but impart a large amount of radiation to the child. The fracture can be safely treated with a below-knee cast for approximately 3 wk.

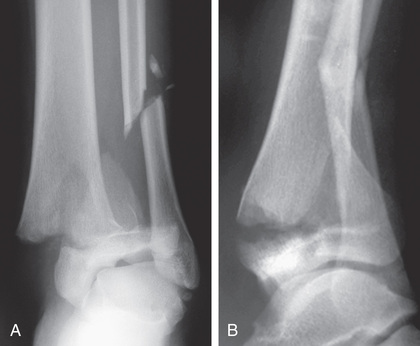

Triplane and Tillaux Fractures

Triplane and Tillaux fracture patterns occur at the end of the growth period and are based on relative strength of the bone–physis junction and asymmetric closure of the tibial physis. The triplane fractures are so named because the injury has coronal, sagittal, and transverse components (Fig. 703.14 ). The Tillaux fracture is an avulsion fracture of the anterolateral aspect of the distal tibial epiphysis. Radiographs and further imaging with CT and 3-dimensional reconstructions are necessary to analyze the fracture geometry. The triplane fracture involves the articular surface and hence anatomic reduction is necessary. The reduction is further stabilized with internal fixation. The Tillaux fracture is treated by closed reduction. Open reduction is recommended if a residual intraarticular step-off persists.

Metatarsal Fractures

Metatarsal fractures are common in children. They usually result from direct trauma to the dorsum of the foot. High-energy trauma or multiple fractures of the metatarsal base are associated with significant swelling. A high index for compartment syndrome of the foot must be maintained and compartment pressures must be measured if indicated. Diagnosis is obtained by AP, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the foot. Most metatarsal fractures can be treated by closed methods in a below-knee cast. Weight bearing is allowed as tolerated. Displaced fractures can require closed or open reduction with internal fixation. Percutaneous, smooth Kirschner wires generally provide sufficient internal fixation for these injuries. If the compartment pressure is increased, complete release of all compartments in the foot is necessary.

Toe Phalangeal Fractures

Fractures of the lesser toes are common and are usually secondary to direct blows. They commonly occur when the child is barefoot. The toes are swollen, ecchymotic, and tender. There may be a mild deformity. Diagnosis is made radiographically. Bleeding suggests the possibility of an open fracture. The lesser toes usually do not require closed reduction unless significantly displaced. If necessary, reduction can usually be accomplished with longitudinal traction on the toe. Casting is not usually necessary. Buddy taping of the fractured toe to an adjacent stable toe usually provides satisfactory alignment and relief of symptoms. Crutches and heel walking may be beneficial for several days until the soft tissue swelling and the discomfort decrease.

Bibliography

Baldwin K, Hsu JE, Wenger DR, et al. Treatment of femur fractures in school-aged children using elastic stable intramedullary nailing: a systematic review. J Pediatr Orthop B . 2011;20(5):303–308.

Bhandari M, Jeray KJ, Petrisor BA, et al. A trial of wound irrigation in the initial management of open fracture wounds. N Engl J Med . 2015;327(27):2629–2640.

Boutis K, Plint A, Stimec J, et al. Radiograph-negative lateral ankle injuries in children: occult growth plate fracture or sprain? JAMA Pediatr . 2016;170(1):e154114.

Brousil J, Hunter JB. Femoral fractures in children. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2013;25:52–56.

Cummings RJ. Paediatric femoral fracture. Lancet . 2005;365:1116–1117.

Flynn JM, Garner MR, Jones KJ, et al. The treatment of low-energy femoral shaft fractures: a prospective study comparing the “walking spica”: with the traditional spica cast. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2011;93(23):2196–2202.

ed 4. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2009. Green NE, Swiontkowski MF. Skeletal trauma in children . vol 3.

Heffernan MJ, Gordon JE, Sabatini CS, et al. Treatment of femur fractures in young children: a multicenter comparison of flexible intramedullary nails to spica casting in young children aged 2 to 6 years. J Pediatr Orthop . 2015;35(2):126–129.

Hoeffe J, Trottier ED, Bailey B, et al. Intranasal fentanyl and inhaled nitrous oxide for fracture reduction: the FAN observational study. Am J Emerg Med . 2017;35(5):710–715.

Loud KJ, Micheli LJ, Bristol S, et al. Family history predicts stress fracture in active female adolescents. Pediatrics . 2007;120:e364–e372.

Malanga GA, Ramirez-Del Toro JA. Common injuries of the foot and ankle in the child and adolescent athlete. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am . 2008;19(2):347–371 [ix].

Patel S, Haddad F. Triplane fractures of the ankle. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) . 2009;70(1):34–40.

Poonai N, Bhullar G, Lin K, et al. Oral administration of morphine versus ibuprophen to manage postfracture pain in children: a randomized trial. CMAJ . 2014;186(18):1358–1363.

Wells L, Millman JE. Trauma related to the lower extremity. Dormans JP. Pediatric orthopaedics: core knowledge in orthopaedics . Mosby: Philadelphia; 2005:85–115.

Wright JG, Wang EEL, Owen JL, et al. Treatments for paediatric femoral fractures: a randomized trial. Lancet . 2005;365:1153–1162.

Yeranosian M, Horneff JG, Baldwin K, et al. Factors affecting the outcome of fractures of the femoral neck in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Bone Joint J . 2013;95-B(1):135–142.

Operative Treatment of Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Surgery is required for 4–5% of pediatric fractures. The common indications for operative treatment in children and adolescents include displaced physeal fractures, displaced intraarticular fractures, unstable fractures, multiple injuries, open fractures, failure to achieve adequate reduction in older children, failure to maintain an adequate reduction, and certain pathologic fractures.

The aim of operative intervention is to obtain anatomic alignment and relative stability. Rigid fixation is not necessary as it is in adults for early mobilization. The relatively stable construct can be supplemented with external immobilization. SH types III and IV injuries require anatomic alignment, and if they are unstable, internal fixation is used (smooth Kirschner wires, preferably avoiding the course across the growth plate). Multiple closed reductions of an epiphyseal fracture are contraindicated because they can cause permanent damage to the germinal cells of the physis.

Surgical Techniques

It is important to take great care with soft tissues and skin. The other indications for open reduction and internal fixation are unstable fractures of the spine, ipsilateral fractures of the femur and tibia, neurovascular injuries requiring repair, and open fractures. Closed reduction and minimally invasive fixation are specifically used for supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus and most phalangeal fractures. Failure to obtain anatomic alignment by closed means is an indication for an open reduction. Percutaneous techniques such as intramedullary fixation and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis are increasingly popular as well.

As children become older and more similar to adults, techniques become more similar to adult techniques. The classic example of this is the femoral shaft fracture. Newborns may be treated with a soft dressing or Pavlik harness; young children may have a spica cast; older children will often be treated with flexible nails. Adolescents will frequently be treated with rigid intramedullary fixation similar to their adult counterparts.

Table 703.3 summarizes the main indications for external fixation. The advantages of external fixation include rigid immobilization of the fractures, access to open wounds for continued management, and easier patient mobilization for treatment of other injuries and transportation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The majority of complications with external fixation are pin tract infections, chronic osteomyelitis, and refractures after pin removal.

Complications of Fractures in Children

Keith D. Baldwin, Apurva S. Shah, Lawrence Wells, Alexandre Arkader

Complications of fractures in children can be categorized as (1) complications of the injury itself, (2) complications of treatment, and (3) late complications resulting from growth disturbance or deformity.

Complications Resulting From Injury

Growth arrest is possible in physeal fractures, particularly widely displaced physeal fractures about the distal femur, proximal tibia, or distal ulna. Fractures about the hip may cause avascular necrosis or premature physeal closure, particularly when the fracture involves the proximal femoral physis. Unacceptable alignment may cause loss of motion or limb malalignment. Fracture malunion may cause cosmetically unappealing bumps or curves in the limb, and at times functional impairment. Compartment syndrome can occur, particularly in diaphyseal tibia fractures or high energy or open both bone forearm fractures. Supracondylar humerus fractures, distal femur fractures, and proximal tibia fractures may result in neurovascular compromise. Nonunions are rare in children, but can be seen with intraarticular fractures, such as distal humerus lateral condyle. Malunions (or missed) of Monteggia fracture dislocations about the elbow can cause permanent stiffness and loss of function if the deformity is not corrected. Displaced intraarticular fractures can result in posttraumatic arthritis and early joint degeneration. Open fractures can result in infection and osteomyelitis if inadequately treated. Older children with severe injuries of the lower extremity can be vulnerable to deep vein thrombosis.

Complications of Treatment

Treatment may complicate fractures. Cast immobilization can result in cast ulcers, either from inadequate padding of bony prominences or from patients placing objects in the cast. Casts that are too tight can cause neurovascular compromise and compartment syndrome. Patients can get cast saw burns from using cast saws that are too dull to remove the cast. Safe operation of a cast saw requires monitoring of blade temperature. The saw blade should be intermittently cooled with a wet towel to avoid overheating and thermal injury to the skin. Improperly placed casts can promote fracture displacement and malunion. Surgical treatment can be complicated by blood loss, neurovascular compromise, iatrogenic physeal damage, and hardware complications such as infection or hardware failure. Symptomatic hardware may require later removal.

Late Complications of Trauma

Late effects of trauma can be from partial or complete closure of the physis, or malunion of the fracture. This can lead to limb angular deformity, shortening, or incongruency. Angular deformities can be treated by hemiepiphysiodesis or osteotomy. Joint incongruency may be a very difficult problem to deal with and may ultimately lead to early degenerative joint disease. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy is another poorly understood late effect of trauma but can be debilitating. Distal radius fractures have been observed to have a higher than average rate of reflex sympathetic dystrophy relative to other injuries. Physical and occupational therapists are very helpful in managing this condition. Some evidence exists that vitamin C may be useful in the acute setting of high-risk injuries to prevent this complication.