Abused and Neglected Children

Howard Dubowitz, Wendy G. Lane

The abuse and neglect (maltreatment ) of children are pervasive problems worldwide, with short- and long-term physical and mental health and social consequences. Child healthcare professionals have an important role in helping address this problem. In addition to their responsibility to identify maltreated children and help ensure their protection and health, child healthcare professionals can also play vital roles related to prevention, treatment, and advocacy. Rates and policies vary greatly among nations and, often, within nations. Rates of maltreatment and provision of services are affected by the overall policies of the country, province, or state governing recognition and responses to child abuse and neglect. Two broad approaches have been identified: a child and family welfare approach and a child safety approach. Although overlapping, the focus in the former is the family as a whole, and in the latter, on the child perceived to be at risk. The United States has primarily had a child safety approach.

Definitions

Abuse is defined as acts of commission and neglect as acts of omission. The U.S. government defines child abuse as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.” Some states also include other household members. Children may be found in situations in which no actual harm has occurred, and no imminent risk of serious harm is evident, but potential harm may be a concern. Many states include potential harm in their child abuse laws. Consideration of potential harm enables preventive intervention, although predicting potential harm is inherently difficult. Two aspects should be considered: the likelihood of harm and the severity of that harm.

Physical abuse includes beating, shaking, burning, and biting. Corporal punishment , however, is increasingly being prohibited. The Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children reported that 52 countries have prohibited corporal punishment in all settings, including the home. Governments in 55 other countries have expressed a commitment to full prohibition. In the United States, corporal punishment in the home is lawful in all states, but 31 states have banned corporal punishment in public.

The threshold for defining corporal punishment as abuse is unclear. One can consider any injury beyond transient redness as abuse. If parents spank a child, it should be limited to the buttocks, should occur over clothing, and should never involve the head and neck. When parents use objects other than a hand, the potential for serious harm increases. Acts of serious violence (e.g., throwing a hard object, slapping an infant's face) should be seen as abusive even if no injury ensues; significant risk of harm exists. While some child healthcare professionals think that hitting is acceptable under limited conditions, almost all know that more constructive approaches to discipline are preferable. The American Academy of Pediatrics clearly opposed the use of corporal punishment in a recent policy statement. Although many think that hitting a child should never be accepted, and many studies have documented the potential harm, there remains a reluctance in the United States to label hitting as abuse, unless there is an injury. It is clear that the emotional impact of being hit may leave the most worrisome scar, long after the bruises fade and the fracture heals.

Sexual abuse has been defined as “the involvement of dependent, developmentally immature children and adolescents in sexual activities which they do not fully comprehend, to which they are unable to give consent, or that violate the social taboos of family roles.” Sexual abuse includes exposure to sexually explicit materials, oral-genital contact, genital-to-genital contact, genital-to-anal contact, and genital fondling. Any touching of private parts by parents or caregivers in a context other than necessary care is inappropriate.

Neglect refers to omissions in care, resulting in actual or potential harm. Omissions include inadequate healthcare, education, supervision, protection from hazards in the environment, and unmet physical needs (e.g., clothing, food) and emotional support. A preferable alternative to focusing on caregiver omissions is to instead consider the basic needs (or rights) of children (e.g., adequate food, clothing, shelter, healthcare, education, nurturance). Neglect occurs when a need is not adequately met and results in actual or potential harm, whatever the reasons. A child whose health is jeopardized or harmed by not receiving necessary care experiences medical neglect . Not all such situations necessarily require a report to child protective services (CPS); less intrusive initial efforts may be appropriate.

Psychological abuse includes verbal abuse and humiliation and acts that scare or terrorize a child. Although this form of abuse may be extremely harmful to children, resulting in depression, anxiety, poor self-esteem, or lack of empathy, CPS seldom becomes involved because of the difficulty in proving such allegations. Child healthcare professionals should still carefully consider this form of maltreatment, even if the concern fails to reach a legal or agency threshold for reporting. These children and families can benefit from counseling and social support. Many children experience more than one form of maltreatment; CPS are more likely to address psychological abuse in the context of other forms of maltreatment.

Within in the United States and internationally, problems of trafficking in children, for purposes of cheap labor and sexual exploitation, expose children to all the forms of abuse just noted (see Chapter 15 ).

Incidence and Prevalence

Global

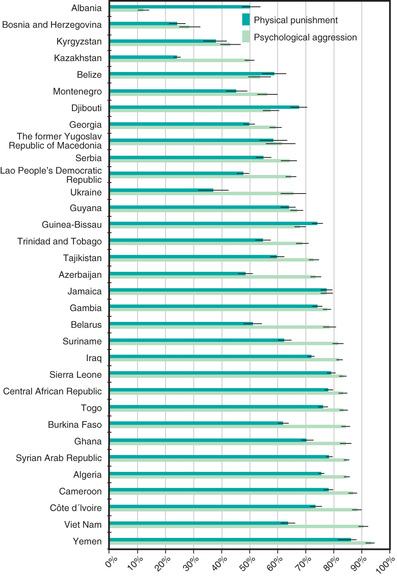

Child abuse and neglect are not rare and occur worldwide. Based on international studies, the World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 18% of girls and 8% of boys experience sexual abuse as children, while 23% of children report being physically abused (Figs. 16.1 and 16.2 ). In addition, many children experience emotional abuse and neglect. Surveys reported by United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) confirm these reports; one survey conducted in the Middle East reported that 30% of children had been beaten or tied up by parents, and in a survey in a Southeast Asian country, 30% of mothers reported having hit their child with an object in the past 6 mo.

United States

Abuse and neglect mostly occur behind closed doors and often are a well-kept secret. Nevertheless, there were 4 million reports to CPS involving 7.2 million children in the United States in 2015. Of the 683,000 children with substantiated reports (9.2 per 1,000 children), 78.3% experienced neglect (including 1.9% medical neglect), 17.2% physical abuse, 8.4% sexual abuse, and 6.2% psychological maltreatment. While there had been a decline in rates beginning in the early 1990s, rates increased in 2014 and 2015 from prior years. Likewise, the rate of hospitalized children with serious physical abuse has not declined in recent years. Medical personnel made 9.1% of all reports.

Other sources independent from the official CPS statistics cited above confirm the prevalence of child maltreatment. In a community survey, 3% of parents reported using very severe violence (e.g., hitting with fist, burning, using gun or knife) against their child in the prior year. Considering a natural disinclination to disclose socially undesirable information, such rates are both conservative and alarming.

Etiology

Child maltreatment seldom has a single cause; rather, multiple and interacting biopsychosocial risk factors at 4 levels usually exist. To illustrate, at the individual level , a child's disability or a parent's depression or substance abuse predispose a child to maltreatment. At the familial level , intimate partner (or domestic) violence presents risks for children. Influential community factors include stressors such as dangerous neighborhoods or a lack of recreational facilities. Professional inaction may contribute to neglect, such as when the treatment plan is not clearly communicated. Broad societal factors , such as poverty and its associated burdens, also contribute to maltreatment. WHO estimates the rate of homicide of children is approximately 2-fold higher in low-income compared to high-income countries (2.58 vs 1.21 per 100,000 population), but clearly homicide occurs in high-income countries too. Children in all social classes can be maltreated, and child healthcare professionals need to guard against biases concerning low-income families.

In contrast, protective factors , such as family supports, or a mother's concern for her child, may buffer risk factors and protect children from maltreatment. Identifying and building on protective factors can be vital to intervening effectively. One can say to a parent, “I can see how much you love [child's name]. What can we do to keep her out of the hospital?” Child maltreatment results from a complex interplay among risk and protective factors. A single mother who has a colicky baby and who recently lost her job is at risk for maltreatment, but a loving grandmother may be protective. A good understanding of factors that contribute to maltreatment, as well as those that are protective, should guide an appropriate response.

Clinical Manifestations

Child abuse and neglect can manifest in many ways. A critical element of physical abuse is the lack of a plausible history other than inflicted trauma. The onus is on the clinician to carefully consider the differential diagnosis and not jump to conclusions.

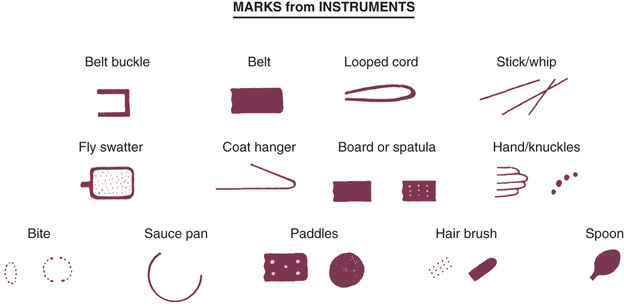

Bruises are the most common manifestation of physical abuse. Features suggestive of inflicted bruises include (1) bruising in a preambulatory infant (occurring in just 2% of infants), (2) bruising of padded and less exposed areas (buttocks, cheeks, ears, genitalia), (3) patterned bruising or burns conforming to shape of an object or ligatures around the wrists, and (4) multiple bruises, especially if clearly of different ages (Fig. 16.3 and Table 16.1 ). Earlier suggestions for estimating the age of bruises have been discredited. It is very difficult to precisely determine the ages of bruises.

Table 16.1

| METHOD OF INJURY/IMPLEMENT | PATTERN OBSERVED |

|---|---|

| Grip/grab | Relatively round marks that correspond to fingertips and/or thumb |

| Closed-fist punch | Series of round bruises that correspond to knuckles of the hand |

| Slap | Parallel, linear bruises (usually petechial) separated by areas of central sparing |

| Belt/electrical cord | Loop marks or parallel lines of petechiae (the width of the belt/cord) with central sparing; may see triangular marks from the end of the belt, small circular lesions caused by the holes in the tongue of the belt, and/or a buckle pattern |

| Rope | Areas of bruising interspersed with areas of abrasion |

| Other objects/household implements | Injury in shape of object/implement (e.g., rods, switches, and wires cause linear bruising) |

| Human bite | Two arches forming a circular or oval shape, may cause bruising and/or abrasion |

| Strangulation | Petechiae of the head and/or neck, including mucous membranes; may see subconjunctival hemorrhages |

| Binding/ligature |

Marks around the wrists, ankles, or neck; sometimes accompanied by petechiae or edema distal to the ligature mark Marks adjacent to the mouth if the child has been gagged |

| Excessive hincar * | Abrasions/burns, especially to knees |

| Hair pulling | Traumatic alopecia; may see petechiae on underlying scalp, or swelling or tenderness of the scalp (from subgaleal hematoma) |

| Tattooing or intentional scarring | Abusive cases have been described, but can also be a cultural phenomenon (e.g., Maori body ornamentation) |

* Punishment by kneeling on salt or other rough substance.

Other conditions such as birthmarks and congenital dermal melanocytosis (e.g., mongolian spots) can be confused with bruises and abuse. These skin markings are not tender and do not rapidly change color or size. An underlying medical explanation for bruises may exist, such as blood dyscrasias (hemophilia) or connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome). The history or examination usually provides clues to these conditions. Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the most common vasculitis in young children, may be confused with abuse. The pattern and location of bruises caused by abuse are usually different from those due to a coagulopathy. Noninflicted bruises are characteristically anterior and over bony prominences, such as shins and forehead. The presence of a medical disorder does not preclude abuse.

Cultural practices can cause bruising. Cao gio, or coining, is a Southeast Asian folkloric therapy. A hard object is vigorously rubbed on the skin, causing petechiae or purpura. Cupping is another approach, popular in the Middle East. A heated glass is applied to the skin, often on the back. As it cools, a vacuum is formed, leading to perfectly circular bruises. The context here is important, and such circumstances should not be considered abusive (see Chapter 11 ).

A careful history of bleeding problems in the patient and first-degree relatives is needed. If a bleeding disorder is suspected, a complete blood count including platelet count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time should be obtained. More extensive testing, such as factors VIII, IX and XIII activity and von Willebrand evaluation, should be considered in consultation with a hematologist.

Bites have a characteristic pattern of 1 or 2 opposing arches with multiple bruises. They can be inflicted by an adult, another child, an animal, or the patient. Forensic odontologists have previously developed guidelines for distinguishing adult from child and human from animal bites. However, several studies have identified problems with the accuracy and consistency of bite mark analysis.

Burns may be inflicted or caused by inadequate supervision. Scalding burns may result from immersion or splash. Immersion burns, when a child is forcibly held in hot water, show clear delineation between the burned and healthy skin and uniform depth. They may have a sock or glove distribution. Splash marks are usually absent, unlike when a child inadvertently encounters hot water. Symmetric burns are especially suggestive of abuse, as are burns of the buttocks and perineum (Fig. 16.4 ). Although most often accidental, splash burns may also result from abuse. Burns from hot objects such as curling irons, radiators, steam irons, metal grids, hot knives, and cigarettes leave patterns representing the object (Fig. 16.5 ). A child is likely to draw back rapidly from a hot object; thus burns that are extensive and deep reflect more than fleeting contact and are suggestive of abuse.

Several conditions mimic abusive burns, such as brushing against a hot radiator, car seat burns, hemangiomas, and folk remedies such as moxibustion. Impetigo may resemble cigarette burns. Cigarette burns are usually 7-10 mm across, whereas impetigo has lesions of varying size. Noninflicted cigarette burns are usually oval and superficial.

Neglect frequently contributes to childhood burns. Children, home alone, may be burned in house fires. A parent taking drugs may cause a fire and may be unable to protect a child. Exploring children may pull hot liquids left unattended onto themselves. Liquids cool as they flow downward so that the burn is most severe and broad proximally. If the child is wearing a diaper or clothing, the fabric may absorb the hot water and cause burns worse than otherwise expected. Some circumstances are difficult to foresee, and a single burn resulting from a momentary lapse in supervision should not automatically be seen as neglectful parenting.

Concluding whether a burn was inflicted depends on the history, burn pattern, and the child's capabilities. A delay in seeking healthcare may result from the burn initially appearing minor, before blistering or becoming infected. This circumstance may represent reasonable behavior and should not be automatically deemed neglectful. A home investigation is often valuable (e.g., testing the water temperature).

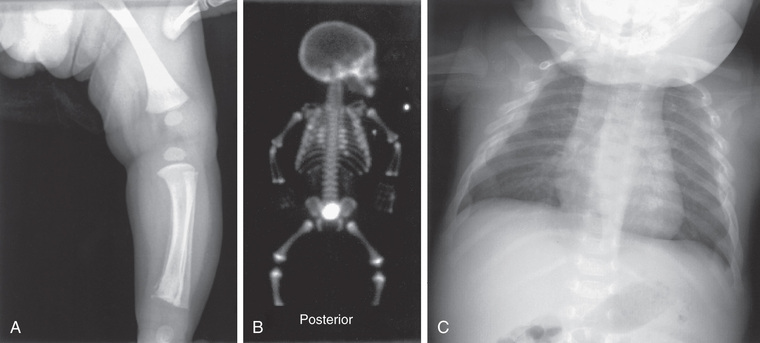

Fractures that strongly suggest abuse include classic metaphyseal lesions, posterior rib fractures, and fractures of the scapula, sternum, and spinous processes, especially in young children (Table 16.2 ). These fractures all require more force than would be expected from a minor fall or routine handling and activities of a child. Rib and sternal fractures rarely result from cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), even when performed by untrained adults. The recommended 2-finger or 2-thumb technique recommended for infants since 2005 may produce anterolateral rib fractures. In abused infants, rib (Fig. 16.6 ), metaphyseal (Fig. 16.7 ), and skull fractures are most common. Femoral and humeral fractures in nonambulatory infants are also very worrisome for abuse. With increasing mobility and running, toddlers can fall with enough rotational force to cause a spiral, femoral fracture. Multiple fractures in various stages of healing are suggestive of abuse; nevertheless, underlying conditions need to be considered. Clavicular, femoral, supracondylar humeral, and distal extremity fractures in children older than 2 yr are most likely noninflicted unless they are multiple or accompanied by other signs of abuse. Few fractures are pathognomonic of abuse; all must be considered in light of the history and the child's developmental level. Fractures may present as an irritable fussy child.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that increase susceptibility to fractures, such as osteopenia and osteogenesis imperfecta, metabolic and nutritional disorders (e.g., scurvy, rickets), renal osteodystrophy, osteomyelitis, congenital syphilis, and neoplasia. Some have pointed to possible rickets and low but subclinical levels of vitamin D as being responsible for fractures thought to be abusive. The evidence to date does not support this supposition. Features of congenital or metabolic conditions associated with nonabusive fractures include family history of recurrent fractures after minor trauma, abnormally shaped cranium, dentinogenesis imperfecta, blue sclera, craniotabes, ligamentous laxity, bowed legs, hernia, and translucent skin. Subperiosteal new bone formation is a nonspecific finding seen in infectious, traumatic, and metabolic disorders. In young infants, new bone formation may be a normal physiologic finding, usually bilateral, symmetric, and <2 mm in depth.

The evaluation of a fracture should include a skeletal radiologic survey in children <2 yr old when abuse seems possible (Table 16.3 ). Multiple radiographs with different views are needed; “babygrams” (1 or 2 films of the entire body) should be avoided. If the survey is normal, but concern for an occult injury remains, a radionucleotide bone scan should be performed to detect a possible acute injury. Follow-up films after 2 wk may also reveal fractures not apparent initially.

In corroborating the history and the injury, the age of a fracture can be crudely estimated (Table 16.4 ). Soft tissue swelling subsides in 2-21 days. Subperiosteal new bone is visible within 6-21 days. Loss of definition of the fracture line occurs in 10-21 days. Soft callus can be visible after 9 days and hard callus at 14-90 days. These ranges are shorter in infancy and longer in children with poor nutritional status or a chronic underlying disease. Fractures of flat bones such as the skull do not form callus and cannot be aged, although soft tissue swelling indicates approximate recency (within the prior week).

Table 16.4

Timetable of Radiologic Changes in Children's Fractures* (in Days)

| CATEGORY | EARLY | PEAK | LATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subperiosteal new bone formation | 4-10 | 10-14 | 14-21 |

| 2. Loss of fracture line definition | 10-14 | 14-21 | |

| 3. Soft callus | 10-14 | 14-21 | |

| 4. Hard callus | 14-21 | 21-42 | 42-90 |

* Repetitive injuries may prolong all categories. The time points tend to increase from early infancy into childhood.

Adapted from Kleinman PK: Diagnostic imaging of child abuse , ed 3, Cambridge, UK, 2015, Cambridge University Press, p 215.

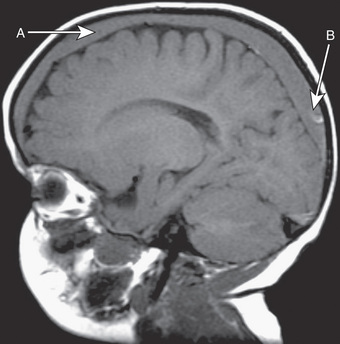

Abusive head trauma (AHT) results in the most significant morbidity and mortality. Abusive injury may be caused by direct impact, asphyxia, or shaking. Subdural hematomas (Fig. 16.8 ), retinal hemorrhages, especially when extensive and involving multiple layers, and diffuse axonal injury strongly suggest AHT, especially when they occur together. The poor neck muscle tone and relatively large heads of infants make them vulnerable to acceleration-deceleration forces associated with shaking, leading to AHT. Children may lack external signs of injury, even with serious intracranial trauma. Signs and symptoms may be nonspecific, ranging from lethargy, vomiting (without diarrhea), changing neurologic status or seizures, and coma. In all preverbal children, an index of suspicion for AHT should exist when children present with these signs and symptoms.

Acute intracranial trauma is best evaluated by initial and follow-up CT. MRI is helpful in differentiating extra axial fluid, determining timing of injuries, assessing parenchymal injury, and identifying vascular anomalies. MRI is best obtained 5-7 days after an acute injury. Glutaric aciduria type 1 can present with intracranial bleeding and should be considered. Other causes of subdural hemorrhage in infants include arteriovenous malformations, coagulopathies, birth trauma, tumor, and infections. When AHT is suspected, injuries elsewhere—skeletal and abdominal—should be ruled out.

Retinal hemorrhages are an important marker of AHT (Fig. 16.9 ). Whenever AHT is being considered, a dilated indirect eye examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist should be performed. Although retinal hemorrhages can be found in other conditions, hemorrhages that are multiple, involve >1 layer of the retina, and extend to the periphery are very suspicious for abuse. The mechanism is likely repeated acceleration-deceleration from shaking. Traumatic retinoschisis points strongly to abuse.

With other causes of retinal hemorrhages, the pattern is usually different than seen in child abuse. After birth, many newborns have them, but they disappear in 2-6 wk. Coagulopathies (particularly leukemia), retinal diseases, carbon monoxide poisoning, or glutaric aciduria may be responsible. Severe, noninflicted, direct crush injury to the head can rarely cause an extensive hemorrhagic retinopathy. CPR rarely, if ever, causes retinal hemorrhage in infants and children; if present, there a few hemorrhages in the posterior pole. Hemoglobinopathies, diabetes mellitus, routine play, minor noninflicted head trauma, and vaccinations do not appear to cause retinal hemorrhage in children. Severe coughing or seizures rarely cause retinal hemorrhages that could be confused with AHT.

The dilemma frequently posed is whether minor, everyday forces can explain the findings seen in AHT. Simple linear skull fractures in the absence of other suggestive evidence can be explained by a short fall, although even that is rare (1-2%), and underlying brain injury from short falls is exceedingly rare. Timing of brain injuries in cases of abuse is not precise. In fatal cases, however, the trauma most likely occurred very soon before the child became symptomatic.

Other manifestations of AHT may be seen. Raccoon eyes occur in association with subgaleal hematomas after traction on the anterior hair and scalp, or after a blow to the forehead. Neuroblastoma can present similarly and should be considered. Bruises from attempted strangulation may be visible on the neck. Choking or suffocation can cause hypoxic brain injury, often with no external signs.

Abdominal trauma accounts for significant morbidity and mortality in abused children. Young children are especially vulnerable because of their relatively large abdomens and lax abdominal musculature. A forceful blow or kick can cause hematomas of solid organs (liver, spleen, kidney) from compression against the spine, as well as hematoma (duodenal) or rupture (stomach) of hollow organs. Intraabdominal bleeding may result from trauma to an organ or from shearing of a vessel. More than 1 organ may be affected. Children may present with cardiovascular failure or an acute condition of the abdomen, often after a delay in care. Bilious vomiting without fever or peritoneal irritation suggests a duodenal hematoma, often caused by abuse.

The manifestations of abdominal trauma are often subtle, even with severe injuries. Bruising of the abdominal wall is unusual, and symptoms may evolve slowly. Delayed perforation may occur days after the injury; bowel strictures or a pancreatic pseudocyst may occur weeks or months later. Child healthcare professionals should consider screening for occult abdominal trauma when other evidence of physical abuse exists. Screening should include liver and pancreatic enzyme levels, and testing urine for blood. Children with lab results indicating possible injury should have abdominal CT performed. CT or ultrasound should also be performed if there is concern about possible splenic, adrenal, hepatic, or reproductive organ injury.

Oral lesions may present as bruised lips, bleeding, torn frenulum, and dental trauma or caries (neglect).

Neglect

Neglect is the most prevalent form of child maltreatment, with potentially severe and lasting sequelae. It may manifest in many ways, depending on which needs are not adequately met. Nonadherence to medical treatment, for example, may aggravate the condition, as may a delay in seeking care. Inadequate food may manifest as impaired growth; inattention to obesity may compound that problem. Poor hygiene may contribute to infected cuts or lesions. Inadequate supervision contributes to injuries and ingestions. Children's needs for mental healthcare, dental care, and other health-related needs may be unmet, manifesting as neglect in those areas. Educational needs, particularly for children with learning disabilities, are often not met.

The evaluation of possible neglect requires addressing critical questions: “Is this neglect?” and “Have the circumstances harmed the child, or jeopardized the child's health and safety?” For example, suboptimal treatment adherence may lead to few or no clear consequences. Inadequacies in the care that children receive naturally fall along a continuum, requiring a range of responses tailored to the individual situation. Legal considerations or CPS policies may discourage physicians from labeling many circumstances as neglect. Even if neglect does not meet a threshold for reporting to CPS, child healthcare professionals can still help ensure children's needs are adequately met.

General Principles for Assessing Possible Abuse and Neglect

The heterogeneity of circumstances in situations of child maltreatment precludes specific detailing of varied assessments. The following are useful general principles.

- ◆ Given the complexity and possible ramifications of determining child maltreatment, an interdisciplinary assessment is optimal, with input from all involved professionals. Consultation with a physician expert in child maltreatment is recommended.

- ◆ A thorough history should be obtained from the parent(s) optimally via separate interviews.

- ◆ Verbal children should be interviewed separately, in a developmentally appropriate manner. Open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me what happened”) are best. Some children need more directed questioning (e.g., “How did you get that bruise?”); others need multiple-choice questions. Leading questions must be avoided (e.g., “Did your daddy hit you?”).

- ◆ A thorough physical examination is necessary.

- ◆ Careful documentation of the history and physical is essential. Verbatim quotes are valuable, including the question that prompted the response. Photographs are helpful.

- ◆ For abuse : What is the evidence for concluding abuse? Have other diagnoses been ruled out? What is the likely mechanism of the injury? When did the injury likely occur?

- ◆ For neglect : Do the circumstances indicate that the child's needs have not been adequately met? Is there evidence of actual harm? Is there evidence of potential harm and on what basis? What is the nature of the neglect? Is there a pattern of neglect?

- ◆ Are there indications of other forms of maltreatment? Has there been prior CPS involvement?

- ◆ A child's safety is a paramount concern. What is the risk of imminent harm, and of what severity?

- ◆ What is contributing to the maltreatment? Consider the categories described in the section on etiology.

- ◆ What strengths/resources are there? This is as important as identifying problems.

- ◆ What interventions have been tried, with what results? Knowing the nature of these interventions can be useful, including from the parent's perspective.

- ◆ What is the prognosis ? Is the family motivated to improve the circumstances and accept help, or resistant? Are suitable resources, formal and informal, available?

- ◆ Are there other children in the home who should be assessed for maltreatment?

General Principles for Addressing Child Maltreatment

The heterogeneity of circumstances also precludes specific details regarding how to address different types of maltreatment. The following are general principles.

- ◆ Treat any medical problems.

- ◆ Help ensure the child's safety , often in conjunction with CPS; this is a priority.

- ◆ Convey concerns of maltreatment to parents, kindly but forthrightly. Avoid blaming. It is natural to feel anger toward parents of maltreated children, but they need support and deserve respect.

- ◆ Have a means of addressing the difficult emotions child maltreatment can evoke.

- ◆ Be empathic, and state interest in helping or suggest another pediatrician.

- ◆ Know your national and state laws and/or local CPS policies on reporting child maltreatment. In the United States, the legal threshold for reporting is typically “reason to believe” (or similar language such as “reason to suspect”); one does not need to be certain. Physical abuse and moderate to severe neglect warrant a report. In less severe neglect, less intrusive interventions may be an appropriate initial response. For example, if an infant's mild failure to thrive is caused by an error in mixing the formula, parent education and perhaps a visiting nurse should be tried. In contrast, severe failure to thrive may require hospitalization, and if the contributing factors are particularly serious (e.g., psychotic mother), out-of-home placement may be needed. CPS can assess the home environment, providing valuable insights.

- ◆ Reporting child maltreatment is never easy. Parental inadequacy or culpability is at least implicit, and parents may express considerable anger. Child healthcare professionals should supportively inform families directly of the report; it can be explained as an effort to clarify the situation and provide help, as well as a professional (and legal) responsibility. Explaining what the ensuing process is likely to entail (e.g., a visit from a CPS worker and sometimes a police officer) may ease a parent's anxiety. Parents are frequently concerned that they might lose their child. Child healthcare professionals can cautiously reassure parents that CPS is responsible for helping children and families and that, in most instances, children remain with their parents. When CPS does not accept a report or when a report is not substantiated, they may still offer voluntary supportive services such as food, shelter, parenting resources, and childcare. Child healthcare professionals can be a useful liaison between the family and the public agencies and should try to remain involved after reporting to CPS.

- ◆ Help address contributory factors, prioritizing those most important and amenable to being remedied. Concrete needs should not be overlooked; accessing nutrition programs, obtaining health insurance, enrolling children in preschool programs, and help finding safe housing can make a valuable difference. Parents may need their own problems addressed to enable them to provide adequate care for their children.

- ◆ Establish specific objectives (e.g., no hitting, diabetes will be adequately controlled), with measurable outcomes (e.g., urine dipsticks, hemoglobin A1c). Similarly, advice should be specific and limited to a few reasonable steps. A written contract can be very helpful.

- ◆ Engage the family in developing the plan, solicit their input and agreement.

- ◆ Build on strengths ; there are always some. These provide a valuable way to engage parents.

- ◆ Encourage informal supports (e.g., family, friends; invite fathers to office visits). This is where most people get their support, not from professionals. Consider support available through a family's religious affiliation.

- ◆ Consider children's specific needs . Too often, maltreated children do not receive direct services.

- ◆ Be knowledgeable about community resources, and facilitate appropriate referrals.

- ◆ Provide support, follow-up, review of progress, and adjust the plan if needed.

- ◆ Recognize that maltreatment often requires long-term intervention with ongoing support and monitoring.

Outcomes of Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment often has significant short- and long-term medical, mental health, and social sequelae. Physically abused children are at risk for many problems, including conduct disorders, aggressive behavior, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and mood disorders, decreased cognitive functioning, and poor academic performance. Neglect is similarly associated with many potential problems. Even if a maltreated child appears to be functioning well, healthcare professionals and parents need to be sensitive to the possibility of later problems. Maltreatment is associated with increased risk in adolescence and adulthood for health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol/drug abuse), mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicide attempt), physical health problems (e.g., heart disease, arthritis), and mental health problems. Maltreated children are at risk for becoming abusive parents. The neurobiologic effects of child abuse and neglect on the developing brain may partly explain some of these sequelae.

Some children appear to be resilient and may not exhibit sequelae of maltreatment, perhaps because of protective factors or interventions. The benefits of intervention have been found in even the most severely neglected children, such as those from Romanian orphanages, who were adopted—the earlier the better.

Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect

An important aspect of prevention is that many of the efforts to strengthen families and support parents should promote children's health, development, and safety, as well as prevent child abuse and neglect. Medical responses to child maltreatment have typically occurred after the fact; preventing the problem is preferable. Child healthcare professionals can help in several ways. An ongoing relationship offers opportunities to develop trust and knowledge of a family's circumstances. Astute observation of parent–child interactions can reveal useful information.

Parent and child education regarding medical conditions helps to ensure implementation of the treatment plan and to prevent neglect. Possible barriers to treatment should be addressed. Practical strategies such as writing down the plan can help. In addition, anticipatory guidance may help with child rearing, diminishing the risk of maltreatment. Hospital-based programs that educate parents about infant crying and the risks of shaking the infant may help prevent abusive head trauma.

Screening for major psychosocial risk factors for maltreatment (depression, substance abuse, intimate partner violence, major stress), and helping address identified problems, often through referrals, may help prevent maltreatment. The primary care focus on prevention offers excellent opportunities to screen briefly for psychosocial problems. The traditional organ system–focused review of systems can be expanded to probe areas such as feelings about the child, the parent's own functioning, possible depression, substance abuse, intimate partner violence, disciplinary approaches, stressors, and supports. The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model offers a promising approach for pediatric primary care to identify and help address prevalent psychosocial problems. This can strengthen families; support parents; promote children's health, development, and safety; and help prevent child maltreatment.

Obtaining information directly from children or youth is also important, especially given that separate interviews with teens have become the norm. Any concerns identified on such screens require at least brief assessment and initial management, which may lead to a referral for further evaluation and treatment. More frequent office visits can be scheduled for support and counseling while monitoring the situation. Other key family members (e.g., fathers) might be invited to participate, thereby encouraging informal support. Practices might arrange parent groups through which problems and solutions are shared.

Child healthcare professionals also need to recognize their limitations and facilitate referrals to other community resources. Finally, the problems underpinning child maltreatment, such as poverty, parental stress, substance abuse, and limited child-rearing resources, require policies and programs that enhance families’ abilities to care for their children adequately. Child healthcare professionals can help advocate for such policies and programs.

Advocacy

Child healthcare professionals can assist in understanding what contributed to the child's maltreatment. When advocating for the best interest of the child and family, addressing risk factors at the individual, family, and community levels is optimal. At the individual level, an example of advocating on behalf of a child is explaining to a parent that an active toddler is behaving normally and not intentionally challenging the parent. Encouraging a mother to seek help dealing with a violent spouse (e.g., saying, “You and your life are very important”), asking about substance abuse, and helping parents obtain health insurance for their children are all forms of advocacy.

Efforts to improve family functioning, such as encouraging fathers’ involvement in child care, are also examples of advocacy. Remaining involved after a report to CPS and helping ensure appropriate services are provided is advocacy as well. In the community, child health professionals can be influential advocates for maximizing resources devoted to children and families. These include parenting programs, services for abused women and children, and recreational facilities. Lastly, child healthcare professionals can play an important role in advocating for policies and programs at the local, state, and national levels to benefit children and families. Child maltreatment is a complex problem that has no easy solutions. Through partnerships with colleagues in child protection, mental health, education, and law enforcement, child health professionals can make a valuable difference in the lives of many children and families.

Sexual Abuse

Wendy G. Lane, Howard Dubowitz

See also Chapter 145 .

Approximately 18% of females and 7% of males in the United States will be sexually abused at some point during their childhood. Whether children and families share this information with their pediatrician will depend largely on the pediatrician's comfort with and openness to discussing possible sexual abuse with families. Pediatricians may play a number of different roles in addressing sexual abuse, including identification, reporting to child protective services (CPS), testing for and treating sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and providing support and reassurance to children and families. Pediatricians may also play a role in the prevention of sexual abuse by advising parents and children about ways to help keep safe from sexual abuse. In many U.S. jurisdictions, general pediatricians will play a triage role, with the definitive medical evaluation conducted by a child abuse specialist.

Definition

Sexual abuse may be defined as any sexual behavior or action toward a child that is unwanted or exploitative. Some legal definitions distinguish sexual abuse from sexual assault : abuse being committed by a caregiver or household member, and assault being committed by someone with a noncustodial relationship or no relationship with the child. For this chapter, the term sexual abuse will encompass both abuse and assault. It is important to note that sexual abuse does not have to involve direct touching or contact by the perpetrator. Showing pornography to a child, filming or photographing a child in sexually explicit poses, and encouraging or forcing one child to perform sex acts on another all constitute sexual abuse.

Presentation of Sexual Abuse

Children who have been sexually abused sometimes provide a clear, spontaneous disclosure to a trusted adult. Often the signs of sexual abuse are subtle. For some children, behavioral changes are the first indication that something is amiss. Nonspecific behavior changes such as social withdrawal, acting out, increased clinginess or fearfulness, distractibility, and learning difficulties may be attributed to a variety of life changes or stressors. Regression in developmental milestones, including new-onset bed-wetting or encopresis, is another behavior that caregivers may overlook as an indicator of sexual abuse. Teenagers may respond by becoming depressed, experimenting with drugs or alcohol, or running away from home. Because nonspecific symptoms are very common among children who have been sexually abused, it should almost always be included in one's differential diagnosis of child behavior changes.

Some children may not exhibit behavioral changes or provide any other indication that something is wrong. For these children, sexual abuse may be discovered when another person witnesses the abuse or discovers evidence such as sexually explicit photographs or videos. Pregnancy may be another way that sexual abuse is identified. Other children, some with and some without symptoms, will not be identified at any point during their childhood.

Caregivers may become concerned about the possibility of sexual abuse when children exhibit sexually explicit behavior . This behavior includes that which is outside the norm for a child's age and developmental level. For preschool and school-age children, sexually explicit behavior may include compulsive masturbation, attempting to perform sex acts on adults or other children, or asking adults or children to perform sex acts on them. Teenagers may become sexually promiscuous and even engage in prostitution. Older children and teenagers may respond by sexually abusing younger children. It is important to recognize that this behavior could also result from accidental exposure (e.g., child enters parents’ bedroom at night and sees them having sex), or from neglect (e.g., adults watching pornographic movies where a child can see them).

Role of General Pediatrician in Assessment and Management of Possible Sexual Abuse

Before determining where and how a child with suspected sexual abuse is evaluated, it is important to assess for and rule out any medical problems that can be confused with abuse. A number of genital findings may raise concern about abuse but often have alternative explanations. Genital redness in a prepubertal child is more often caused by nonspecific vulvovaginitis, eczema, or infection with staphylococcus, group A streptococcus, Haemophilus , or yeast. Lichen sclerosis is a less common cause of redness. Vaginal discharge can be caused by STIs, but also by poor hygiene, vaginal foreign body, early in the onset of puberty, or infection with Salmonella , Shigella , or Yersinia . Genital ulcers can be caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) and syphilis, but also by Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, Crohn disease, and Behçet disease. Genital bleeding can be caused by urethral prolapse, vaginal foreign body, accidental trauma, and vaginal tumor.

Although other medical conditions may need to be evaluated, any possible sexual abuse should be investigated (Fig. 16.10 ). Where and how a child with suspected sexual abuse is evaluated should be determined by duration since the last incident of abuse likely occurred, and whether the child is prepubertal or postpubertal. For the prepubertal child , if abuse has occurred in the previous 72 hr, and history suggests direct contact, forensic evidence collection (e.g., external genital, vaginal, anal, and oral swabs, sometimes referred to as a “rape kit”) is indicated, and the child should be referred to a site equipped to collect forensic evidence. Depending on the jurisdiction, this site may be an emergency department (ED), a child advocacy center, or an outpatient clinic. If the last incident of abuse occurred >72 hr prior, the likelihood of recovering forensic evidence is extremely low, making forensic evidence collection unnecessary. For postpubertal females , many experts recommend forensic evidence collection up to 120 hr following the abuse—the same time limit as for adult women. The extended time frame is justified because some studies have demonstrated that semen can remain in the postpubertal vaginal vault for >72 hr.

The site to which a child is referred may be different when the child does not present until after the cutoff for an acute examination. Because EDs may not have a child abuse expert and can be busy, noisy, and lacking in privacy, examination at an alternate location such as a child advocacy center or outpatient clinic is recommended. If the exam is not urgent, waiting until the next morning is recommended because it is easier to interview and examine a child who is not tired and cranky. Referring physicians should be familiar with the triage procedures in their communities, including the referral sites for both acute and chronic exams, and whether there are separate referral sites for prepubertal and postpubertal children.

Children with suspected sexual abuse may present to the pediatrician's office with a clear disclosure of abuse or subtler indicators. A private, brief conversation between pediatrician and child can provide an opportunity for the child to speak in his or her own words without the parent speaking for the child. Doing this may be especially important when the caregiver does not believe the child, or is unwilling or unable to offer emotional support and protection. Telling caregivers that a private conversation is part of the routine assessment for the child's concerns can help comfort a hesitant parent.

When speaking with the child, experts recommend establishing rapport by starting with general and open-ended questions, such as, “Tell me about school,” and “What are your favorite things to do?” Questions about sexual abuse should be nonleading (e.g., “Who touched you there?”). A pediatrician should explain that sometimes children are hurt or bothered by others, and that he or she wonders whether that might have happened to the child. Open-ended questions, such as, “Can you tell me more about that?” allow the child to provide additional information and clarification in his or her own words. It is not necessary to obtain extensive information about what happened because the child will usually have a forensic interview once a report is made to CPS and an investigation begins. Very young children and those with developmental delay may lack the verbal skills to describe what happened. In this situation the caregiver's history may provide enough information to warrant a report to CPS without interviewing the child.

All 50 U.S. states mandate that professionals report suspected maltreatment to CPS. The specific criteria for “reason to suspect” are generally not defined by state law. It is clear that reporting does not require certainty that abuse has occurred. Therefore, it may be appropriate to report a child with sexual behavior concerns when no accidental sexual exposure can be identified, and when the child does not clearly confirm or deny abuse.

Physical Examination of the Child With Suspected Sexual Abuse

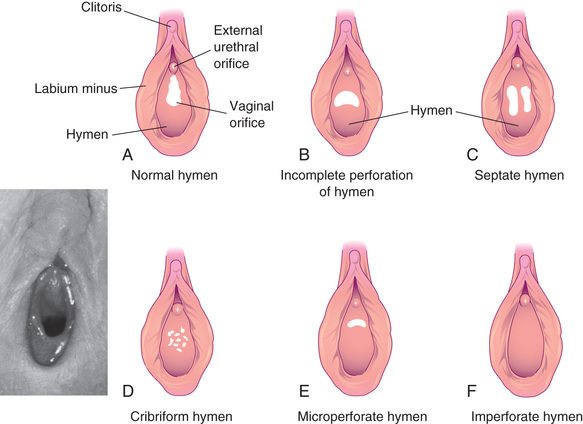

Unfortunately, many physicians are unfamiliar with genital anatomy and examination, particularly in the prepubertal child (Figs. 16.11 and 16.12 ). Because about 95% of children who undergo a medical evaluation following sexual abuse have normal examinations, the role of the primary care provider is often simply to be able to distinguish a normal exam from findings indicative of common medical concerns or trauma. The absence of physical findings can often be explained by the type and timing of sexual contact that has occurred. Abusive acts such as fondling, or even digital penetration, can occur without causing injury. In addition, many children do not disclose abuse until days, weeks, months, or even years after the abuse has occurred. Because genital injuries usually heal rapidly, injuries are often completely healed by the time a child presents for medical evaluation. A normal genital examination does not rule out the possibility of abuse and should not influence the decision to report to CPS.

Even with the high proportion of normal genital exams, there is value in conducting a thorough physical examination. Unsuspected injuries or medical problems, such as labial adhesions, imperforate hymen, or urethral prolapse, may be identified. In addition, reassurance about the child's physical health may allay anxiety for the child and family.

Few findings on the genital examination are diagnostic for sexual abuse. In the acute time frame, lacerations or bruising of the labia, penis, scrotum, perianal tissues, or perineum are indicative of trauma. Likewise, hymenal bruising and lacerations and perianal lacerations extending deep to the external anal sphincter indicate penetrating trauma. In the nonacute time frame, perianal scars and scars of the posterior fourchette or fossa indicate trauma and/or sexual activity. A complete transection of the hymen to the base between the 4 and 8 o'clock in the supine position (i.e., absence of hymenal tissue in the posterior rim) is considered diagnostic for trauma (Fig. 16.12 ). For these findings, the cause of injury must be elucidated through the child and caregiver history. If there is any concern that the finding may be the result of sexual abuse, CPS should be notified and a medical evaluation performed by an experienced child abuse pediatrician.

Testing for STIs is not indicated for all children but is warranted in certain situations (Table 16.5 ). Culture was once considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of vaginal gonorrhea (see Chapter 219 ) and chlamydia (Chapter 252 ) infections in children. However, several studies demonstrated that nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for gonorrhea and chlamydia by either vaginal swab or urine in prepubertal females is as sensitive, and possibly more sensitive, than culture. Current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) allow for NAAT testing by vaginal swab or urine as an alternative to culture in females. Because obtaining vaginal swabs can be uncomfortable for prepubertal children, urine testing is preferable. Culture remains the preferred method for testing of rectal and pharyngeal specimens in males and females. Few data are available on the use of urine NAAT testing in prepubertal boys. Therefore the CDC continues to recommend urine or urethral culture for boys. Many child abuse experts perform urine NAAT testing on prepubertal boys because urethral swabs are uncomfortable, and good data support urine NAAT testing in females. For all NAAT testing in both genders, the child should not receive presumptive treatment at testing. Instead, a positive NAAT test should be confirmed by culture or an alternate NAAT test before treatment. Because gonorrhea and chlamydia in prepubertal children do not typically cause ascending infection, waiting for a definitive diagnosis before treatment will not increase the risk for pelvic inflammatory disease. Testing for Trichomonas vaginalis is by culture (Diamond media or InPouch; Biomed Diagnostics, White City, OR) or wet mount. Wet mount requires the presence of vaginal secretions, viewing must be immediate for optimal results, and sensitivity is only 44–68%; therefore false-negative tests are common. Experts have determined that insufficient data exist to recommend commercially available Trichomonas NAATs for prepubertal children. However, there is also no reason to suspect that test performance in children would be different from adults.

A number of STIs should raise concern for abuse (Table 16.6 ). In a prepubertal child, gonorrhea or syphilis beyond the neonatal period indicates that the child has had some contact with infected genital secretions, almost always as a result of sexual abuse. There is some evidence to indicate that chlamydia in children up to 3 yr of age may be perinatally acquired. Chlamydia in children >3 yr old is diagnostic of contact with infected genital secretions, almost always a result of sexual abuse. In children <3 yr old, sexual abuse should still be strongly considered beyond the neonatal period. HIV is diagnostic for sexual abuse if other means of transmission have been excluded. Because of the potential for transmission either perinatally or through nonsexual contact, the presence of genital warts has a low specificity for sexual abuse. The possibility of sexual abuse should be considered and addressed with the family, especially in children whose warts first appear beyond 5 yr of age. Type 1 or 2 genital herpes is concerning for sexual abuse, but not diagnostic given other possible routes of transmission. For human papillomavirus (HPV) and HSV, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends reporting to CPS unless perinatal or horizontal transmission is considered likely.

Table 16.6

| ST/SA CONFIRMED | EVIDENCE FOR SEXUAL ABUSE | SUGGESTED ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Gonorrhea* | Diagnostic | Report † |

| Syphilis* | Diagnostic | Report † |

| HIV ‡ | Diagnostic | Report † |

| Chlamydia trachomatis * | Diagnostic | Report † |

| Trichomonas vaginalis * | Highly suspicious | Report † |

| Genital herpes | Highly suspicious (HSV-2 especially) | Report † , § |

| Condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts)* | Suspicious | Consider report † , § , ** |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Inconclusive | Medical follow-up |

* If not likely to be perinatally acquired, and rare vertical transmission is excluded.

† Reports should be made to the agency in the community mandated to receive reports of suspected child abuse or neglect.

‡ If not likely to be acquired perinatally or through transfusion.

§ Unless a clear history of autoinoculation exists.

** Report if evidence exists to suspect abuse, including history, physical examination, or other identified infections.

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; SA, sexually associated; ST, sexually transmitted.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015, MMWR 64(RR3):1-137, 2015 (Table 6).

Additional Management

Because HIV testing identifies antibodies to the virus and not the human immunodeficiency virus itself, and because it may take several months for seroconversion, repeat testing at 6 wk and 3 mo after the last suspected exposure is indicated. Repeat testing for syphilis is also recommended. Hepatitis B and HPV vaccination (for children ≥9 yr) should be given if the child has not been previously vaccinated or vaccination is incomplete.

Sexual Abuse Prevention

Pediatricians can play a role in the prevention of sexual abuse by educating parents and children about sexual safety at well-child visits. During the genital exam the pediatrician can inform the child that only the doctor and select adult caregivers should be permitted to see their private parts, and that a trusted adult should be told if anyone else attempts to do so. Pediatricians can raise parental awareness that older kids or adults may try to engage in sexual behavior with children. The pediatrician can teach parents how to minimize the opportunity for perpetrators to access children, for example, by limiting one-adult/one-child situations and being sensitive to any adult's unusual interest in young children. In addition, pediatricians can help parents talk to children about what to do if confronted with a potentially abusive situation. Some examples include telling children to say “no,” to leave, and to tell a parent and/or another adult. If abuse does occur, the pediatrician can tell parents how to recognize possible signs and symptoms, and how to reassure the child that she or he was not at fault. Lastly, pediatricians can provide parents with suggestions about how to maintain open communication with their children so that these conversations can occur with minimal parent and child discomfort.

Bibliography

Adams JA, Kellogg ND, Farst KJ, et al. Updated guidelines for medical assessment and care of children who may have been sexually abused. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol . 2016;29:81–87.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics . 2005;116:506–512.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of children in the primary care setting when sexual abuse is suspected. Pediatrics . 2013;132:e558–e567.

Bandea CI, Joseph K, Secor EW, et al. Development of PCR testing for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in urine specimens. J Clin Microbiol . 2013;51:1298–1300.

Black CM, Driebe EM, Howard LA, et al. Multicenter study of nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in children being evaluated for sexual abuse. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2009;28:608–612.

DeLago C, Deblinger E, Schroeder C, et al. Girls who disclose sexual abuse: urogenital symptoms and signs after genital contact. Pediatrics . 2008;122:e281–e286.

Garland SM, Subasinghe AK. HPV vaccination for victims of childhood sexual abuse. Lancet . 2015;386:1919–1920.

Giradet RG, Lahoti S, Howard LA, et al. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in suspected child victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics . 2009;124:79–86.

Hammerschlag MR. Sexual assault and abuse of children. Clin Infect Dis . 2011;53(Suppl 3):S103–S109.

Hobbs MM, Seña AC. Modern diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Sex Transm Infect . 2013;89:434–438.

Paras ML, Murad MH, Chen LP, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders. JAMA . 2009;302:550–561.

Seña AC, Hsu KK, Kellogg N, et al. Sexual assault and sexually transmitted infections in adults, adolescents, and children. Clin Infect Dis . 2015;61:SB56–SB64.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep . 2015;64(RR–3):1–137.

Medical Child Abuse (Factitious Disorder by Proxy, Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy)

Howard Dubowitz, Wendy G. Lane

The term Munchausen syndrome is used to describe situations in which adults falsify their own symptoms. In Munchausen syndrome by proxy , a parent, typically a mother, simulates or causes disease in her child. Several terms have been suggested to describe this phenomenon: factitious disorder by proxy, pediatric condition falsification, and currently, medical child abuse (MCA) . In some instances, such as partial suffocation, child abuse may be most appropriate.

The core dynamic of MCA is that a parent falsely presents a child for medical attention. This may occur by fabricating a history, such as reporting seizures that never occurred. A parent may directly cause a child's illness, by exposing a child to a toxin, medication, or infectious agent (e.g., injecting stool into an intravenous line). Signs or symptoms may also be manufactured, such as when a parent smothers a child, or alters laboratory samples or temperature measurements. Each of these actions may lead to unnecessary medical care, sometimes including intrusive tests and surgeries. The “problems” often recur repeatedly over several years. In addition to the physical concomitants of testing and treatment, there are potentially serious and lasting social and psychological sequelae.

Child healthcare professionals are typically misled into thinking that the child really has a medical problem. Parents, sometimes working in a medical field, may be adept at constructing somewhat plausible presentations. A convincing seizure history may be offered, and a normal electroencephalogram (EEG) cannot fully rule out the possibility of a seizure disorder. Even after extensive testing fails to lead to a diagnosis or treatment proves ineffective, health professionals may think they are confronting a new or rare disease. Unwittingly, this can lead to continued testing (leaving no stone unturned) and interventions, thus perpetuating the MCA. Pediatricians generally rely on and trust parents to provide an accurate history. As with other forms of child maltreatment, an accurate diagnosis of MCA requires that the pediatrician maintain a healthy skepticism under certain circumstances.

Clinical Manifestations

The presentation of MCA may vary in nature and severity. Consideration of MCA should be triggered when the reported symptoms are repeatedly noted by only 1 parent, appropriate testing fails to confirm a diagnosis, and seemingly appropriate treatment is ineffective. At times, the child's symptoms, their course, or the response to treatment may be incompatible with any recognized disease. Preverbal children are usually involved, although older children may be convinced by parents that they have a particular problem and become dependent on the increased attention; this may lead to feigning symptoms.

Symptoms in young children are mostly associated with proximity of the offending caregiver to the child. The mother may present as a devoted or even model parent who forms close relationships with members of the healthcare team. While appearing very interested in her child's condition, she may be relatively distant emotionally. She may have a history of Munchausen syndrome, although not necessarily diagnosed as such.

Bleeding is a particularly common presentation. This may be caused by adding dyes to samples, adding blood (e.g., from the mother) to the child's sample, or giving the child an anticoagulant (e.g., warfarin).

Seizures are another common manifestation, with a history easy to fabricate, and the difficulty of excluding the problem based on testing. A parent may report that another physician diagnosed seizures, and the myth may be continued if there is no effort to confirm the basis for the “diagnosis.” Alternatively, seizures may be induced by toxins, medications (e.g., insulin), water, or salts. Physicians need to be familiar with the substances available to families and the possible consequences of exposure.

Apnea is also a common presentation. The observation may be falsified or created by partial suffocation. A history of a sibling with the same problem, perhaps dying from it, should be cause for concern. Parents of children hospitalized for brief resolved unexplained events (or apparent life-threatening events) have been videotaped attempting to suffocate their child while in the hospital.

Gastrointestinal signs or symptoms are another common manifestation. Forced ingestion of medications such as ipecac may cause chronic vomiting, or laxatives may cause diarrhea.

The skin , easily accessible, may be burned, dyed, tattooed, lacerated, or punctured to simulate acute or chronic skin conditions. Recurrent sepsis may be caused by infectious agents being administered; intravenous lines during hospitalization may provide a convenient portal. Urine and blood samples may be contaminated with foreign blood or stool.

Diagnosis

In assessing possible MCA, several explanations should be considered in addition to a true medical problem. Some parents may be extremely anxious and genuinely concerned about possible problems. This anxiety may result from a personality trait, the death of neighbor's child, or something read on the internet. Alternatively, parents may believe something told to them by a trusted physician despite subsequent evidence to the contrary and efforts to correct the earlier misdiagnosis. Physicians may unwittingly contribute to a parent's belief that a real problem exists by, perhaps reasonably, persistently pursuing a medical diagnosis. There is a need to discern commonly used hyperbole (e.g., exaggerating height of fever) in order to evoke concern and perhaps justify an ED visit. In the end, a diagnosis of MCA rests on clear evidence of a child repeatedly being subjected to unnecessary medical tests and treatment, primarily stemming from a parent's actions. Determining the parent's underlying psychopathology is the responsibility of mental health professionals.

Once MCA is suspected, gathering and reviewing all the child's medical records from all sources is an onerous but critical first step. It is often important to confer with other treating physicians about what specifically was conveyed to the family. A mother may report that the child's physician insisted that a certain test be done, when instead it was the mother who demanded the test. It is also necessary to confirm the basis for a given diagnosis, rather than simply accepting a parent's account.

Pediatricians may face the dilemma of when to accept that all plausible diagnoses have been reasonably ruled out, the circumstances fit MCA, and further testing and treatment should cease. The likelihood of MCA must be balanced with concerns about possibly missing an important diagnosis. Consultation with a pediatrician expert in child abuse is recommended. In evaluating possible MCA, specimens should be carefully collected, with no opportunity for tampering with them. Similarly, temperature measurements should be closely observed.

Depending on the severity and complexity, hospitalization may be needed for careful observation to help make the diagnosis. In some instances, such as repeated apparent life-threatening events, covert video surveillance accompanied by close monitoring (to rapidly intervene in case a parent attempts to suffocate a child) can be valuable. Close coordination among hospital staff is essential, especially since some may side with the mother and resent even the possibility of MCA being raised. Parents should not be informed of the evaluation for MCA until the diagnosis is made. Doing so could naturally influence their behavior and jeopardize establishing the diagnosis. All steps in making the diagnosis and all pertinent information should be very carefully documented, perhaps using a “shadow chart” to which the parent does not have access.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis is established, the medical team and CPS should determine the treatment plan, which may require out-of-home placement and should include mental healthcare for the offending parent as well as for other affected children. Further medical care should be carefully organized and coordinated by one primary care provider. CPS should be encouraged to meet with the family only after the medical team has informed the offending parent of the diagnosis; their earlier involvement may hamper the evaluation. Parents often respond with resistance, denial, and threats. It may be prudent to have hospital security in the vicinity.

Bibliography

Petska HW, Gordon JB, Jablonski D, Sheets LK. The intersection of medical child abuse and medical complexity. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2017;64(1):253–264.

Rabbone I, Galderisi A, Tinti D, et al. Case report: when an induced illness looks like a rare disease. Pediatrics . 2015;136(5):e1361.

Roesler TA, Jenny C. Medical child abuse: beyond munchausen syndrome by proxy . American Academy of Pediatrics: Elk Grove Village, IL; 2009.

Stirling J Jr, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Beyond munchausen syndrome by proxy: identification and treatment of child abuse in a medical setting. Pediatrics . 2007;119(5):1026–1030.