Sarcoidosis

Eveline Y. Wu

Sarcoidosis is a rare multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The name is derived from a Greek word meaning “flesh-like condition,” in reference to the characteristic skin lesions. There appear to be 2 distinct, age-dependent patterns of disease among children with sarcoidosis. The clinical features in older children are similar to those in adults (pediatric-onset adult sarcoidosis), with frequent systemic features (fever, weight loss, malaise), pulmonary involvement, and lymphadenopathy. In contrast, early-onset sarcoidosis manifesting in children <4 yr of age is characterized by the triad of rash, uveitis, and polyarthritis.

Etiology

The etiology of sarcoidosis remains obscure but likely results from exposure of a genetically susceptible individual to 1 or more unidentified antigens. This exposure initiates an exaggerated immunologic response that ultimately leads to the formation of granulomas. The human major histocompatibility complex is located on chromosome 6, and specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I and class II alleles are associated with disease phenotype. Genetic polymorphisms involving various cytokines and chemokines may also have a role in development of sarcoidosis. Familial clustering supports the contribution of genetic factors to sarcoidosis susceptibility. Environmental and occupational exposures are also associated with disease risk. There are positive associations between sarcoidosis and agricultural employment, occupational exposure to insecticides, and moldy environments typically associated with microbial bioaerosols.

Blau syndrome is an autosomal dominant, familial form of sarcoidosis and is typified by the early onset of granulomatous inflammation involving the skin, eyes, and joints. Missense mutations in the CARD15/NOD2 gene on chromosome 16 have been found in affected family members and appear to be associated with development of sarcoidosis. The 2 most common amino acid substitutions are R334W (arginine to glutamine) and R334Q (arginine to tryptophan). Similar genetic mutations also have been found in individuals with a sporadic early-onset sarcoidosis (EOS) (rash, uveitis, arthritis), suggesting that this nonfamilial form and Blau syndrome are genetically and phenotypically identical (see Chapter 188 ).

Epidemiology

A nationwide patient registry of childhood sarcoidosis in Denmark estimated the annual incidence to be 0.22-0.27 per 100,000 children. The incidence increases with age, and peak onset occurs at 20-39 yr. The most common age of reported childhood cases is 13-15 yr. Annual incidence is about 11 per 100,000 in adult white Americans and is 3 times higher in blacks. There is no clear sex predominance in childhood sarcoidosis. The majority of U.S. childhood sarcoidosis cases are reported in the southeastern and south-central states.

An international registry and Spanish cohort of Blau syndrome and EOS reported the mean age of disease onset as 30 mo and 36 mo, respectively. All but 3 of these young patients presented before 5 yr of age. There does not appear to be a sex predilection in either condition.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Noncaseating, epithelioid granulomatous lesions are a cardinal feature of sarcoidosis. Activated macrophages, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells as well as CD4+ T lymphocytes accumulate and become tightly packed in the center of the granuloma. The causative agent that initiates this inflammatory process is not known. The periphery of the granuloma contains a loose collection of monocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, and fibroblasts. The interaction between the macrophages and CD4+ T lymphocytes is important in the formation and maintenance of the granuloma. The activated macrophages secrete high levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and other proinflammatory mediators. The CD4+ T lymphocytes differentiate into type 1 helper T cells and release interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ, promoting proliferation of lymphocytes. Granulomas may heal or resolve with complete preservation of the parenchyma. In approximately 20% of the lesions, the fibroblasts in the periphery proliferate and produce fibrotic scar tissue, leading to significant and irreversible organ dysfunction.

The sarcoid macrophage is able to produce and secrete 1,25-(OH)2 -vitamin D or calcitriol, an active form of vitamin D typically produced in the kidneys. The hormone's natural functions are to increase intestinal absorption of calcium and bone resorption and decrease renal excretion of calcium and phosphate. An excess of calcitriol may result in hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria in patients with sarcoidosis.

Clinical Manifestations

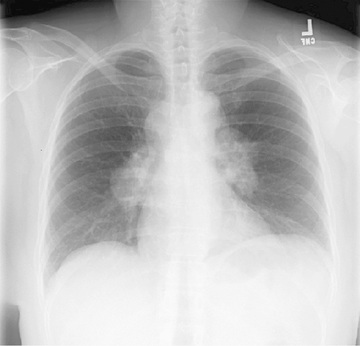

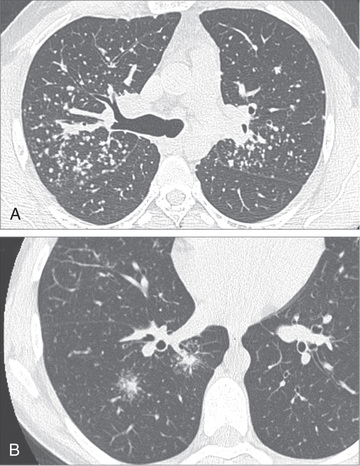

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, and granulomatous lesions may occur in any organ of the body. The clinical manifestations depend on the extent and degree of granulomatous inflammation and are extremely variable. Children may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, and general malaise. In adults and older children, pulmonary involvement is most frequent, with infiltration of the thoracic lymph nodes and lung parenchyma. Isolated bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest radiograph is the most common finding (Fig. 190.1 ), but parenchymal infiltrates and miliary nodules may also be seen (Figs. 190.2 and 190.3 ). Patients with lung involvement are usually found to have restrictive changes on pulmonary function testing. Symptoms of pulmonary disease are seldom severe and generally consist of a dry, persistent cough.

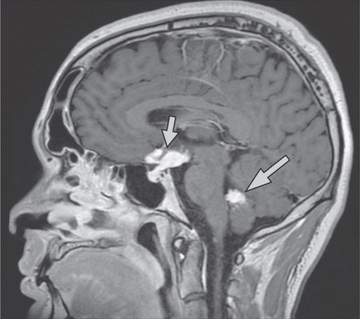

Extrathoracic lymphadenopathy and infiltration of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow also occur often (Table 190.1 ). Infiltration of the liver and spleen typically leads to isolated hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, respectively, but actual organ dysfunction is rare. Cutaneous disease, such as plaques, nodules, erythema nodosum in acute disease, or lupus pernio in chronic sarcoidosis, appears in one quarter of cases and is usually present at onset. Red-brown to purple maculopapular lesions <1 cm on the face, neck, upper back, and extremities are the most common skin finding (Fig. 190.4 ). Ocular involvement is frequent and has variable manifestations, including anterior or posterior uveitis, conjunctival granulomas, eyelid inflammation, and orbital or lacrimal gland infiltration. The arthritis in sarcoidosis can be confused with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is rare in early childhood but may manifest as seizures, cranial nerve involvement, intracranial mass lesions, and hypothalamic dysfunction (Fig. 190.5 ). Kidney disease occurs infrequently in children but typically manifests as renal insufficiency, proteinuria, transient pyuria, or microscopic hematuria caused by early monocellular infiltration or granuloma formation in kidney tissue. Only a small fraction of children have hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria, which is therefore an infrequent cause of kidney disease. Sarcoid granulomas can also infiltrate the heart and lead to cardiac arrhythmias and, rarely, sudden death. Other rare sites of disease involvement include blood vessels of any size, the gastrointestinal tract, parotid gland, muscles, bones, and testes.

Table 190.1

Adapted from Valerye D, Prasse A, Nunes H, et al: Sarcoidosis, Lancet 383:1155–1167, 2014 (Table 1, p 1159).

In contrast to the variable clinical presentation of sarcoidosis in older children, Blau syndrome and EOS (NOD2-associated sarcoidosis) classically manifests as the triad of uveitis, arthritis, and rash. These classic manifestations do not always occur simultaneously. Skin disease usually develops before 1 yr, arthritis at 2-4 yr, and uveitis before 4 yr. Pulmonary disease and lymphadenopathy are less common. The arthritis is polyarticular and symmetric, with large, boggy effusions. Large and small joints are involved. Tenosynovitis is an associated finding. Joints are stiff and moderately tender. The rash may wax and wane and is diffuse (mostly truncal), erythematous or tan, macular-papular, and often desquamates, at times being confused with eczema or ichthyosis vulgaris. Tender subcutaneous nodules resembling erythema nodosum may be seen on the legs. Noncaseating granulomas are demonstrated on biopsy of the skin or joint synovium. Insidious granulomatous iridocyclitis and posterior uveitis are often bilateral and may progress to panuveitis , which has a high risk for vision loss. Iris nodules, photophobia, erythema, cataracts, or glaucoma may be present or develop over time.

Most patients with Blau syndrome and EOS display this more restricted phenotype and develop all or some combination of the rash, arthritis, and uveitis. Many, however, also have an extended phenotype. Additional disease manifestations include fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and lung, kidney, and CNS involvement.

Infantile-onset panniculitis with uveitis and systemic granulomatosis is an uncommon manifestation of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis has also been reported in adults treated with type 1 interferons for hepatitis or multiple sclerosis.

Laboratory Findings

There is no single standard laboratory test diagnostic of sarcoidosis. Anemia, leukopenia, and eosinophilia may be seen. Other nonspecific findings include hypergammaglobulinemia and elevations in acute-phase reactants, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein value. Hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria occur in only a small proportion of children with sarcoidosis. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is produced by the epithelioid cells of the granuloma, and its serum value may be elevated, but this finding lacks diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. ACE levels are estimated to be elevated in >50% of children with sarcoidosis. In addition, ACE values may be difficult to interpret because reference values for serum ACE are age dependent. Fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 positron emission tomography can help identify nonpulmonary sites for a diagnostic biopsy.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis ultimately requires demonstration of the characteristic noncaseating granulomatous lesions in a biopsy specimen (usually taken from the most readily available affected organ) and exclusion of other known causes of granulomatous inflammation. Skin and transbronchial lung biopsies have higher yield, greater specificity, and fewer associated adverse events than biopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes or liver. Additional diagnostic testing should include chest radiography, pulmonary function testing with measurement of diffusion capacity, hepatic enzyme measurements, and renal function assessment. Ophthalmologic slit-lamp examination is essential because ocular inflammation is frequently present and may be asymptomatic in sarcoidosis, and vision loss is a sequela of untreated disease.

Bronchoalveolar lavage may be used to assess for disease activity, and the fluid typically reveals an excess of lymphocytes with an increased CD4+ /CD8+ ratio of 2-13 : 1. In addition to flexible bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy, endosonographic-guided intrathoracic node aspiration has been valuable in obtaining tissue to assess for noncaseating granulomas.

Differential Diagnosis

Because of its protean manifestations, the differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis is extremely broad and depends largely on the initial clinical manifestations. Granulomatous infections , including tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, pulmonary mycoses (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis), brucellosis, tularemia, and toxoplasmosis, must be excluded. Other causes of granulomatous inflammation are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), hypersensitivity pneumonia, chronic berylliosis, and other occupational exposures to metals. Localized granulomatous lesions of the head and neck may be due to orofacial granulomatosis. Immunodeficiencies that may manifest with granulomatous lesions include common variable immunodeficiency, selective IgA deficiency, chronic granulomatous disease, ataxia telangiectasia, and severe combined immunodeficiency. Granulomas of the lung, skin, or lymph nodes have been reported in patients treated with anti-TNF agents. Lymphoma should be ruled out in cases of hilar or other lymphadenopathy. Sarcoid arthritis may mimic JIA. Evaluation for endocrine disorders is needed in the setting of hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria.

Treatment

Treatment should be based on disease severity as well as the number and type of organs involved. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for most acute and chronic disease manifestations. The optimal dose and duration of corticosteroid therapy in children have not been established. Induction treatment typically begins with oral prednisone or prednisolone (1-2 mg/kg/day up to 40 mg daily) for 8-12 wk until manifestations improve. Corticosteroid dosage is then gradually decreased over 6-12 mo to the minimal effective maintenance dose (e.g., 5-10 mg/day) that controls symptoms, or discontinued if symptoms resolve. Methotrexate or leflunomide may be effective as a corticosteroid-sparing agent. On the basis of the role of TNF-α in the formation of granulomas, there is rationale for use of TNF-α antagonists. Results of small clinical trials showed modest effects with infliximab and adalimumab treatment of selected disease manifestations (CNS, lupus pernio, pulmonary, ocular), whereas etanercept does not appear to be particularly effective. Other therapeutics used for sarcoidosis manifestations include topical corticosteroids (eye), inhaled corticosteroids (lung), azathioprine (CNS), cyclophosphamide (cardiac, CNS), hydroxychloroquine (skin), mycophenolate mofetil (CNS, skin), thalidomide or its analogs (skin), and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (joints).

With regard to treatment of Blau syndrome and EOS, there are few case reports and series on the successful use of corticosteroids, methotrexate, thalidomide, and TNF-α antagonists adalimumab and infliximab. Findings of elevated IL-1 levels and response to human IL-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) have been inconsistent.

Prognosis

The prognosis of childhood sarcoidosis is not well defined. The disease may be self-limited with complete recovery or may persist with a progressive or relapsing course. Outcome is worse in the setting of multiorgan or CNS involvement. Most children requiring treatment experience considerable improvement with corticosteroids, although a significant number have morbid sequelae, mainly involving the lungs and eyes. Children with EOS have a poorer prognosis and generally experience a more chronic, progressive disease course. The greatest morbidity is associated with ocular involvement, including cataract formation, development of synechiae, and loss of visual acuity or blindness. Long-term systemic treatment may be required for the eye disease. Progressive polyarthritis may result in joint destruction. The overall mortality rate in childhood sarcoidosis is low.

Serial pulmonary function tests and chest radiographs are useful in following the course of lung involvement. Monitoring for other organ involvement should also include electrocardiogram with consideration of an echocardiogram, urinalysis, renal function tests, and measurements of hepatic enzymes and serum calcium. Other potential indicators of disease activity include inflammatory markers and serum ACE, although changes in ACE level do not always correlate with other indicators of disease status. Given the frequency of asymptomatic eye disease and the ocular morbidity associated with pediatric sarcoidosis, all patients should have an ophthalmologic examination at presentation with monitoring at regular intervals, perhaps every 3-6 mo, as recommended in children with JIA.