Goiter

Jessica R. Smith, Ari J. Wassner

A goiter is an enlargement of the thyroid gland. A normal thyroid volume is approximately 1 mL at birth and increases with age and body mass index. The rule of thumb can be used to evaluate the size of the thyroid in older children (>5 yr) with each lobe of the child's thyroid gland approximating the size of the distal phalanx of the child's thumb. Children with an enlarged thyroid can have normal function of the gland (euthyroidism), underproduction of thyroid hormone (hypothyroidism), or overproduction of thyroid hormone (hyperthyroidism).

Goiter may be congenital or acquired, endemic or sporadic. A goiter often results from increased pituitary secretion of thyrotropin thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in response to decreased circulating levels of thyroid hormone. The most common causes of pediatric goiter are inflammation (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis) and, in endemic areas, iodine deficiency (endemic goiter). Other causes include inborn errors in thyroid hormone synthesis (dyshormonogenesis), thyrotropin receptor–stimulating antibodies (TRSAb) in Graves disease, maternal ingestion of antithyroid drugs, goitrogens, activating mutations of the TSH receptor, or disorders of inappropriate TSH secretion. Thyroid enlargement can also result from thyroid nodules or other infiltrative processes. Most goiters are discovered incidentally by the patient or a caregiver, or on physical examination. Detection of a goiter should prompt an investigation of its cause and assessment of thyroid function.

Congenital Goiter

Ari J. Wassner, Jessica R. Smith

Congenital goiter is usually sporadic and results from a defect in fetal thyroxine (T4 ) synthesis that leads to neonatal hypothyroidism and goiter. This defect may be intrinsic to the fetal thyroid or may be caused by administration of antithyroid drugs (methimazole or propylthiouracil) or iodides during pregnancy for the treatment of maternal thyrotoxicosis. These drugs cross the placenta and can interfere with fetal synthesis of thyroid hormone. The neonatal consequences are most severe when overtreatment with antithyroid drugs also causes concomitant hypothyroidism in the mother, thereby reducing the supply of maternal thyroid hormone available to the fetus. Fetal effects can occur even with relatively low-dose doses of antithyroid drugs; therefore, all women treated with such drugs in the third trimester should undergo serum thyroid studies at birth, even if they appear clinically euthyroid. Administration of thyroid hormone to affected infants may be indicated for clinical hypothyroidism or to reduce goiter size (particularly if causing airway obstruction). Hypothyroidism due to maternal antithyroid drugs is transient, and thyroid hormone may be safely discontinued after the antithyroid drug has been excreted by the neonate, usually after 1-2 wk. In addition to antithyroid drugs, other medications containing significant amounts of iodine can cause congenital goiter, including amiodarone and some proprietary cough preparations used to treat asthma.

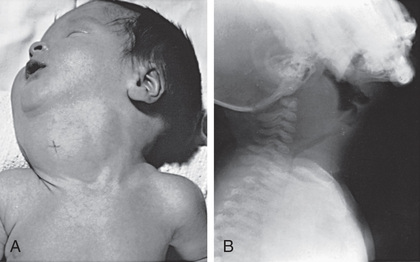

Enlargement of the thyroid at birth may occasionally be sufficient to cause respiratory distress that interferes with nursing and can even cause death. The head may be maintained in extreme hyperextension. In pregnant women who are overtreated with antithyroid drugs, the prenatal diagnosis of even massive fetal goiter can often be corrected by withdrawal or dose reduction of the maternal medication, with or without intra-amniotic thyroid hormone injection. When postnatal respiratory obstruction is severe, partial thyroidectomy rather than tracheostomy is indicated (Fig. 583.1 ).

Goiter is almost always present in the infant with neonatal Graves hyperthyroidism. Thyroid enlargement results from transplacental passage of maternal TSH receptor-stimulating antibodies (see Chapter 584.2 ). These goiters usually are not large, and the infant manifests clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism. The mother often has a history of Graves disease, but occasionally, the diagnosis of maternal Graves disease may be discovered through the evaluation of neonatal hyperthyroidism. Activating mutations of the TSH receptor are also a rare cause of congenital goiter with hyperthyroidism.

In cases of congenital goiter and hypothyroidism in which no cause is identifiable from the maternal or medication history, an intrinsic defect in synthesis of thyroid hormone (dyshormonogenesis) should be suspected. Neonatal screening programs find congenital hypothyroidism caused by such a defect in about 1 in 30,000 infants. Treatment with thyroid hormone should be initiated immediately. If a specific defect is suspected, genetic testing to identify a mutation may be considered (see Chapter 581 ). Monitoring subsequent pregnancies with ultrasonography can be useful in detecting fetal goiters (see Chapter 115 ).

Pendred syndrome is characterized by familial goiter and neurosensory deafness. The syndrome is caused by a mutation in SLC26A4 , which encodes the pendrin chloride–iodide transporter expressed in the thyroid gland and cochlea. Pendrin defects result in abnormal iodide organification in the thyroid and can cause a goiter at birth, but the more common presentation is sensorineural hearing loss with development of a euthyroid goiter later in life.

Iodine deficiency as a cause of congenital goiter is rare in developed countries but persists in endemic areas (see Chapter 583.3 ). More important is the recognition that severe iodine deficiency early in pregnancy can cause neurologic damage during fetal development, even in the absence of goiter. This is true because iodine deficiency can cause maternal as well as fetal hypothyroidism, reducing the protective transfer of maternal thyroid hormones to the fetus.

When a palpable “goiter” is lobulated, asymmetric, firm, or unusually large, a teratoma in or near the thyroid must be considered in the differential diagnosis (see Chapter 585 ).

Bibliography

Bizhanova A, Kopp P. Minireview: the sodium-iodide symporter NIS and pendrin in iodide homeostasis of the thyroid. Endocrinology . 2009;150(3):1084–1090.

Böttcher Y, Eszlinger M, Tonjes A, Paschke R. The genetics of euthyroid familial goiter. Trends Endocrinol Metab . 2005;16(7):314–319.

Hashimoto H, Hashimoto K, Suehara N. Successful in utero treatment of fetal goitrous hypothyroidism: case report and review of the literature. Fetal Diagn Ther . 2006;21(4):360–365.

Köksal N, Aktürk B, Saglan H, et al. Reference values for neonatal thyroid volumes in a moderately iodine-deficient area. J Endocrinol Invest . 2008;31(7):642–646.

Zimmermann MB, Jooste PL, Pandav CS. Iodine-deficiency disorders. Lancet . 2008;372(9645):1251–1262.

Intratracheal Goiter

Ari J. Wassner, Jessica R. Smith

One of the many potential ectopic locations of thyroid tissue is within the trachea. When present, intraluminal thyroid tissue lies beneath the tracheal mucosa and is often continuous with the normally located extratracheal thyroid gland. Both eutopic and ectopic thyroid tissue are susceptible to goitrous enlargement. Therefore, when airway obstruction is associated with a goiter, it must be ascertained whether the obstruction is extratracheal or intratracheal. If obstructive manifestations are mild, administration of sodium levothyroxine usually decreases the size of the goiter. When symptoms are severe, surgical removal of the intratracheal goiter is indicated.

Endemic Goiter and Cretinism

Ari J. Wassner, Jessica R. Smith

Etiology

Goiter caused by iodine deficiency is termed endemic goiter, while cretinism refers to the clinical manifestations of severe hypothyroidism in early life. The association of dietary iodine deficiency with endemic goiter and cretinism is well established. The thyroid gland can overcome a moderate deficiency of iodine by increasing the efficiency of thyroid hormone synthesis. Iodine liberated in peripheral tissues is returned rapidly to the gland, which increases the rate of thyroid hormone synthesis and produces a higher proportion of triiodothyronine (T3 ) to thyroxine (T4 ). This increased activity is achieved by compensatory thyroid hypertrophy and hyperplasia (goiter). In areas of severe iodine deficiency, these compensatory mechanisms are insufficient, and hypothyroidism can result. Estimates from the World Health Organization indicate that nearly 2 billion individuals currently have insufficient iodine intake, including one third of the world's school-age children. Thus, despite great progress in the global effort to reduce iodine deficiency, it remains the leading cause of preventable intellectual disability worldwide.

Because seawater is rich in iodine, the iodine content of fish and shellfish is high. As a result, endemic goiter is rare in coastal populations. Iodine is deficient in the water and native foods in the Pacific West and the Great Lakes regions of the United States. Deficiency of dietary iodine is even greater in certain Alpine valleys, the Himalayas, the Andes, the Congo, and the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Iodized salt provides excellent prophylaxis against iodine deficiency, and in the United States and many other countries that have introduced salt iodization programs, endemic goiter has effectively disappeared. Further iodine intake in the United States is contributed by iodates used in baking, iodine-containing coloring agents, and iodine-containing disinfectants used in the dairy industry. The United States recommended dietary allowance of iodine is as follows:

- ◆ Infants under 6 mo: 110 µg/day

- ◆ Infants 7-12 mo: 130 µg/day

- ◆ Children 1-8 yr: 90 µg/day

- ◆ Children 9-13 yr: 120 µg/day

- ◆ Children 14 yr and older: 150 µg/day

- ◆ Pregnant women: 220 µg/day

- ◆ Lactating women: 290 µg/day

While the overall dietary iodine intake in the United States is considered adequate, the most recent NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) from 2007 to 2010 reports that the median urinary iodine concentration among pregnant U.S. women has dropped to <150 µg/L. This indicates mild iodine deficiency and highlights the risk of iodine deficiency reemergence in industrialized countries as salt intake decreases. These risks can be mitigated by the continued monitoring of iodine status, the adjustment of salt iodization levels, and the targeted supplementation of vulnerable subpopulations (e.g., promotion of iodine-containing prenatal vitamins).

Clinical Manifestations

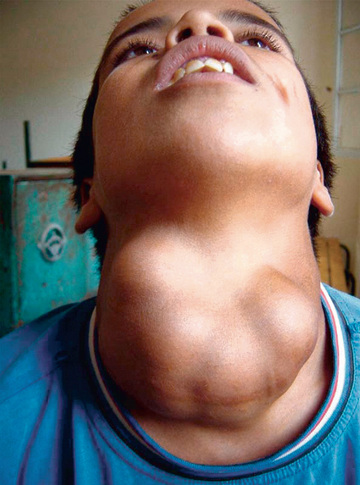

In mild iodine deficiency, thyroid enlargement generally is not noticeable except when demand for thyroid hormone synthesis is increased, such as during rapid growth in adolescence and pregnancy. In regions of moderate iodine deficiency, goiter observed in school children can disappear with maturity and reappear during pregnancy or lactation. Iodine-deficient goiters are more common in girls than in boys. In areas where iodine deficiency is severe, as in the hyperendemic highlands of Papua New Guinea, nearly half the population has large goiters, and endemic cretinism is common (Fig. 583.2 ).

Serum T4 levels are often low in persons with endemic goiter, although clinical hypothyroidism is rare. This is true in Papua New Guinea, the Congo, the Himalayas, and South America. Despite low serum T4 levels, serum TSH concentrations are often normal or only moderately increased due to elevated circulating levels of T3 . In fact, T3 levels are elevated even in patients with normal T4 levels, reflecting the fact that iodine deficiency leads to preferential secretion of T3 by the thyroid and an adaptive increase in peripheral T4 to T3 conversion.

Endemic cretinism is the most serious consequence of iodine deficiency and occurs only in geographic association with endemic goiter. The term endemic cretinism includes 2 different but overlapping syndromes: a neurologic type and a myxedematous type. The incidence of the 2 types varies among different populations. In Papua New Guinea, the neurologic type occurs almost exclusively, whereas in the Congo, the myxedematous type predominates. However, both types are found in all endemic areas, and some persons have intermediate or mixed features.

The neurologic syndrome is characterized by intellectual disability, deaf-mutism, disturbances in standing and gait, and pyramidal signs such as clonus of the foot, the Babinski sign, and patellar hyperreflexia. Affected persons are goitrous, but have little or no impaired thyroid function and have normal pubertal development and adult stature. Persons with the myxedematous syndrome also are intellectually challenged, deaf, and have neurologic symptoms, but in contrast to the neurologic type, they have delayed growth and sexual development, myxedema, and absence of goiter. Serum T4 levels are low and TSH levels are markedly elevated. Delayed skeletal maturation may extend into the 3rd decade or later. Ultrasonographic examination shows thyroid atrophy.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of the neurologic syndrome is attributed to maternal iodine deficiency and hypothyroxinemia during pregnancy, leading to fetal and postnatal hypothyroidism. Although some investigators have attributed brain damage to a direct effect of elemental iodine deficiency in the fetus, most believe the neurologic symptoms are caused by combined fetal and maternal hypothyroxinemia. There is evidence for the presence of thyroid hormone receptors in the fetal brain as early as 7 wk of gestation. Although the normal fetal thyroid gland does not begin to produce significant amounts of thyroid hormone until midgestation, there is measurable T4 in the coelomic fluid as early as 6 wk, almost certainly of maternal origin. These lines of evidence support a role for maternal thyroid hormone in fetal brain development in the first trimester. In addition, there is evidence of transplacental passage of maternal thyroid hormone into the fetus, which normally might ameliorate the effects of fetal hypothyroidism on the developing nervous system in the second half of pregnancy. Thus, iodine deficiency in the mother affects fetal brain development both in the first trimester and throughout pregnancy. Intake of iodine after birth is often sufficient for normal or only minimally impaired thyroid function.

The pathogenesis of the myxedematous syndrome leading to thyroid atrophy is less well understood. Searches for additional environmental factors that might provoke continuing postnatal hypothyroidism have led to incrimination of selenium deficiency, goitrogenic foods, thiocyanates, and Yersinia (Table 583.1 ). Studies from western China suggest that thyroid autoimmunity might play a role. Some have suggested that TSH receptor-blocking immunoglobulins of the type found rarely in infants with sporadic congenital hypothyroidism may play a role in myxedematous cretinism with thyroid atrophy, but not in euthyroid cretinism; however, another study failed to replicate these findings, and the potential role of TSH receptor-blocking immunoglobulins remains unclear.

Table 583.1

Goitrogens and Their Mechanism

| GOITROGEN | MECHANISM |

|---|---|

| FOODS | |

| Cassava, lima beans, linseed, sorghum, sweet potato | Contain cyanogenic glucosides that are metabolized to thiocyanates that compete with iodine for uptake by the thyroid |

| Cruciferous vegetables (cabbage, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips) | Contain glucosinolates; metabolites compete with iodine for uptake by the thyroid |

| Soy, millet | Flavonoids impair thyroid peroxidase activity |

| INDUSTRIAL POLLUTANTS | |

| Perchlorate | Competitive inhibitor of the sodium–iodine symporter, decreasing iodine transport into the thyroid |

| Others (e.g., disulfides from coal processes) | Reduce thyroidal iodine uptake |

| Smoking | Smoking during breastfeeding is associated with reduced iodine concentrations in breast milk; high serum concentration of thiocyanate from smoking might compete with iodine for active transport into the secretory epithelium of the lactating breast |

| NUTRIENTS | |

| Selenium deficiency | Accumulated peroxides can damage the thyroid, and deiodinase deficiency impairs thyroid hormone activation |

| Iron deficiency | Reduces heme-dependent thyroperoxidase activity in the thyroid and may blunt the efficacy of iodine prophylaxis |

| Vitamin A deficiency | Increases TSH stimulation and goiter through decreased vitamin A–mediated suppression of the pituitary TSH-β gene |

TSH , thyroid-stimulating hormone.

From Zimmermann MB, Jooste PL, Pandav CS: Iodine-deficiency disorders, Lancet 372:1251–1262, 2008, Table 1.

Treatment

In many developing countries, administration of a single intramuscular injection of iodinated poppy seed oil to women prevents iodine deficiency during future pregnancies for approximately 5 yr. This form of therapy given to children younger than 4 yr of age with myxedematous cretinism results in a euthyroid state in 5 mo. Older children respond poorly and adults not at all to iodized oil injections, indicating an inability of the thyroid gland to synthesize hormone; these patients require treatment with T4 . Through the efforts of the World Health Organization and its program of universal salt iodization, the number of households worldwide with access to adequately iodized salt has increased from <10% in 1990 to 70% in 2012. In the Xinjiang province of China, where the usual methods of iodine supplementation had failed, iodination of irrigation water has increased iodine levels in soil, animals, and human beings. In other countries, iodinated salt in school meal programs gives children the dietary iodine they need. Nevertheless, political, economic, and practical obstacles have limited penetration of iodized food into regular diets around the world.

Bibliography

Benmiloud M, Chaouki ML, Gutekunst R, et al. Oral iodized oil for correcting iodine deficiency: optimal dosing and outcome indicator selection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 1994;79(1):20–24.

Boyages SC, Halpern JP, Maberly GF, et al. A comparative study of neurological and myxedematous endemic cretinism in western China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 1988;67(6):1262–1271.

DeLange F. Iodine deficiency as a cause of brain damage. Postgrad Med J . 2001;77(906):217–220.

Fuse Y, Saito N, Tsuchiya T, et al. Smaller thyroid gland volume with high urinary iodine excretion in Japanese schoolchildren: normative reference values in an iodine-sufficient area and comparison with the WHO/ICCIDD reference. Thyroid . 2007;17(2):145–155.

Pearce EN, Andersson M, Zimmermann MB. Global iodine nutrition: where do we stand in 2013? Thyroid . 2013;23(5):523–528.

World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, and International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Assessment of the iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination . 3rd ed. World Health Organization: Geneva; 2007.

Zimmermann MB. Iodine deficiency. Endocr Rev . 2009;30(4):376–408.

Acquired Goiter

Jessica R. Smith, Ari J. Wassner

Acquired goiter is usually sporadic and may develop from a variety of causes. Patients are typically euthyroid but may be either hypothyroid or hyperthyroid. The most common cause of acquired goiter is chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (see Chapter 582 ). Rarer causes in children include painless sporadic thyroiditis and subacute or painful thyroiditis (de Quervain disease; see Chapter 582 ). Excess iodide ingestion and certain drugs (amiodarone and lithium) can cause goiter, as can congenital defects in thyroid hormonogenesis. The occurrence of the disorder in siblings, onset in early life, and possible association with hypothyroidism (goitrous hypothyroidism) are important clues to the diagnosis of congenital dyshormonogenesis.

Iodide Goiter

Excessive iodine administration can result in a goiter. Iodine is found in expectorants for chronic reactive airways disease or cystic fibrosis. Most children with iodine-induced goiters have underlying chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis or a subclinical inborn error in thyroid hormone synthesis. In a normal thyroid gland, the acute administration of large doses of iodine inhibits the organification of iodine and the synthesis of thyroid hormone (Wolff-Chaikoff effect). This effect is short-lived and does not lead to permanent hypothyroidism. When iodine administration continues, an autoregulatory mechanism limits iodide trapping, permitting the level of iodide in the thyroid to decrease and normal organification to resume. In patients with iodine-induced goiter, this escape does not occur, usually because of an underlying abnormality in thyroid hormone synthesis.

Iodine-Deficiency Goiter

Iodine deficiency is the most common cause of endemic goiter worldwide, but supplementation with iodized salt has nearly eradicated this entity in the United States. A severely iodine-restricted diet can result in a goiter and hypothyroidism in children and adolescents, or in neonates born to mothers with severe iodine deficiency (urine iodine concentration <50 mcg/L). Children with moderate or severe iodine deficiency and goiter have subclinical or mild hypothyroidism, but their serum T3 concentrations may be normal or high because of preferential thyroidal T3 secretion. They can be treated with either iodine or levothyroxine supplementation.

Goitrogens

Certain foods contain goitrogenic substances (see Table 583.1 ). These substances are unlikely to cause goiter when consumed alone but can contribute to goiter formation when iodine intake is marginal.

Lithium carbonate can cause a goiter and hypothyroidism in children. Lithium decreases T4 and T3 synthesis and release; the mechanism producing the goiter or hypothyroidism is similar to that described for iodide goiter . Lithium and iodide act synergistically to produce goiter, so their combined use should be avoided.

Amiodarone, a drug used to treat cardiac arrhythmias, can cause thyroid dysfunction with goiter because it is rich in iodine. It is also an inhibitor of type 1 deiodinase, preventing conversion of T4 to T3 . Amiodarone can cause hypothyroidism, particularly in patients with underlying autoimmune thyroid disease. In other patients, it can cause thyrotoxicosis through either transient thyroiditis or the Jod-Basedow effect (iodine-induced hyperthyroidism).

Simple Goiter (Colloid Goiter)

Some children with euthyroid goiters have simple goiters, a condition of unknown cause not associated with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism and not caused by inflammation or neoplasia. Simple goiter is more common in girls, may be familial, and has its peak incidence during adolescence. Histologic examination of the thyroid either is normal or reveals variable follicular size, dense colloid, and flattened epithelium. The size of the goiter is variable. It can occasionally be firm, asymmetric, or nodular. Levels of TSH are normal or low, thyroid scintigraphy is normal, and thyroid antibodies are absent. Differentiation from lymphocytic thyroiditis might not be possible without a biopsy, but biopsy is usually not indicated. Simple goiters usually decrease in size gradually over several years, without treatment. Patients should be reevaluated periodically because some have antibody-negative chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and therefore are at risk for changes in thyroid function (see Chapter 582 ).

Multinodular Goiter

Multinodular goiter is usually encountered as a firm goiter with a lobulated surface and one or more palpable nodules. Areas of cystic change, hemorrhage, and fibrosis may be present. The incidence of this condition has decreased markedly with the use of iodine-enriched salt. Ultrasonographic examination can reveal multiple nodules that are nonfunctioning on thyroid scintigraphy. Thyroid studies are usually normal. Some children with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis develop multinodular goiter, and in such cases TSH may be elevated and thyroid antibodies may be present. Children can develop toxic multinodular goiter, characterized by a suppressed TSH and hyperthyroidism. The condition can occur in children with McCune-Albright syndrome or with TSH receptor–activating mutations. If hypofunctioning nodules within a multinodular goiter grow to significant size (≥1 cm), then fine-needle aspiration should be considered to rule out malignancy (see Chapter 585 ).

Toxic Goiter (Hyperthyroidism)

See Chapter 584 .

Bibliography

Akcurin S, Turkkahraman D, Tysoe C, et al. A family with a novel TSH receptor activating germline mutation (p. Ala485val). Eur J Pediatr . 2008;167:1231–1237.

Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Hegedus L. Major role of genes in the etiology of simple goiter in females: a population-based twin study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 1999;84:3071–3075.

De Vries L, Bulvik S, Phillip M. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis in children and adolescents: at presentation and during long-term follow-up. Arch Dis Child . 2009;94:33–37.

Gopalakrishnan S, Chugh PK, Chhillar M, et al. Goitrous autoimmune thyroiditis in a pediatric population: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics . 2008;122:e670–e674.