Fetal Intervention and Surgery

Paul S. Kingma

Numerous diagnoses have been evaluated for the possibility of fetal intervention (Tables 116.1 and 116.2 ). Some have proved beneficial to the developing infant, some have been abandoned, and some are still under investigation.

Table 116.1

Fetal Diagnoses Evaluated and Treated in Fetal Centers

EXIT, Ex utero intrapartum treatment.

Table 116.2

Indications and Rationales for in Utero Surgery on the Fetus, Placenta, Cord, or Membranes

| FETAL SURGERY | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY | RATIONALE FOR IN UTERO INTERVENTION |

|---|---|---|

| SURGERY ON THE FETUS | ||

| Pulmonary hypoplasia and anatomic substrate for pulmonary hypertension | Reversal of pulmonary hypoplasia and reduced degree of pulmonary hypertension; repair of actual defect delayed until after birth | |

|

Progressive renal damage due to obstructive uropathy Pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios |

Prevention of renal failure and pulmonary hypoplasia by anatomic correction or urinary deviation | |

|

High-output cardiac failure due to AV shunting and/or bleeding Direct anatomic effects of the tumoral mass Polyhydramnios-related preterm labor |

Reduction of functional impact of tumor by ablation of tumor or (part of) its vasculature Reduction of anatomic effects by drainage of cysts or bladder Amnioreduction preventing obstetric complications |

|

|

Pulmonary hypoplasia (space-occupying mass) Hydrops due to impaired venous return (mediastinal compression) |

Creation of space for lung development Reversal of the process of cardiac failure |

|

|

Damage to exposed neural tube Chronic CSF leak, leading to Arnold-Chiari malformation and hydrocephalus |

Prevention of exposure of the spinal cord to amniotic fluid; restoration of CSF pressure correcting Arnold-Chiari malformation | |

| Critical lesions causing irreversible hypoplasia or damage to developing heart | Reversal of process by anatomic correction of restrictive pathology | |

| SURGERY ON THE PLACENTA, CORD, OR MEMBRANES | ||

|

High-output cardiac failure due to AV shunting Effects of polyhydramnios |

Reversal of process of cardiac failure and hydrops fetoplacentalis by ablation or reduction of flow | |

| Progressive constrictions causing irreversible neurologic or vascular damage | Prevention of amniotic band syndrome leading to deformities and function loss | |

|

Intertwin transfusion leading to oligopolyhydramnios sequence, hemodynamic changes; preterm labor, and rupture of membranes; in utero damage to brain, heart, or other organs In utero fetal death may cause damage to co-twin. Cardiac failure of pump twin and consequences of polyhydramnios Serious anomaly raising the question of termination of pregnancy Selective fetocide |

Arrest of intertwin transfusion; prevention/reversal of cardiac failure and/or neurologic damage, including at in utero death; prolongation of gestation Selective fetocide to arrest parasitic relationship, to prevent consequences of in utero fetal death, and to avoid termination of entire pregnancy |

|

AV, Arteriovenous; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

From Deprest J, Hodges R, Gratacos E, Lewi L: Invasive fetal therapy. In Creasy RK, Resnick R, Iams JD, et al, editors: Creasy & Resnik's maternal-fetal medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2014, Elsevier (Table 35-1).

Fetal Therapy Ethics

With the development of advanced fetal ultrasound (US), fetal MRI, and fetal echocardiography, the ability to accurately diagnose fetal disease has improved substantially over the past 3 decades. There have also been advances in maternal anesthesia and tocolysis, reduction in maternal morbidity, development of fetal surgery–specific equipment, improved clinical expertise of the fetal care team, and construction of state–of-the-art fetal treatment centers. Fetal surgery remains controversial, however, and every discussion of fetal surgery must include a careful consideration of the ethical conflicts inherit to these procedures.

Unlike most surgical procedures, fetal surgery must consider 2 patients simultaneously, balancing the potential risks and benefits to the fetus with those to the mother during the current and future pregnancies. The International Fetal Medicine and Surgery Society (IFMSS) established a consensus statement on fetal surgery, as follows:

- 1. A fetal surgery candidate should be a singleton with no other abnormalities observed on level II ultrasound, karyotype (by amniocentesis), α-fetoprotein (AFP) level or viral cultures.

- 2. The disease process must not be so severe that the fetus cannot be saved and also not so mild that the infant will do well with postnatal therapy.

- 3. The family must be fully counseled and understand the risks and benefits of fetal surgery, and they must agree to long-term follow-up to track efficacy of the fetal intervention.

- 4. A multidisciplinary team must concur that the disease process is fatal without intervention, that the family understands the risks and benefits, and that the fetal intervention is appropriate.

Obstructive Uropathy

Obstructive uropathy is most frequently caused by posterior urethral valves (PUV) but can be caused by a variety of other defects, including urethral atresia, persistent cloaca, caudal regression, and megacystis–microcolon–intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (see Chapters 555 and 556 ). Obstructive uropathy usually presents on fetal US with an enlarged bladder, bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, and oligohydramnios. Mild forms of obstructive uropathy may lead to minimal short- or long-term clinical sequelae. However, the lack of fetal urine output and resulting oligohydramnios or anhydramnios in more severe forms can cause significant pulmonary hypoplasia , which is associated with death shortly after delivery in >80% of infants. Pulmonary survivors are still subject to high mortality and chronic morbidity resulting from renal dysplasia, renal failure, and the need for chronic renal replacement therapy.

The primary objective of fetal intervention in fetuses with obstructive uropathy is restoration of amniotic fluid volume to prevent pulmonary hypoplasia. Although prevention of ongoing renal injury is also desired, the efficacy of fetal intervention in achieving this goal is uncertain. Several studies have attempted to use fetal urine evaluation to predict renal outcome in these patients, but the reliability of these markers has been disappointing due to the influence of gestational age on many of these markers. Therefore, fetal intervention for obstructive uropathy is currently limited to fetuses in whom the obstruction is sufficient to cause oligohydramnios or anhydramnios.

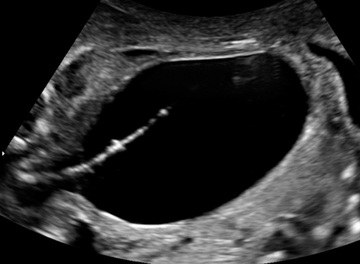

For fetuses who still have adequate renal function and are capable of producing urine, treatment options include vesicoamniotic shunting, valve ablation via cystoscopy, and vesicostomy. Vesicoamniotic shunting is the most common and involves percutaneous, US-guided placement of a double-pigtailed shunt from the fetal bladder to the amniotic space, allowing decompression of the obstructed bladder and restoration of the amniotic fluid volume (Fig. 116.1 ). Although simple in concept, bladder decompression may not always occur, and many catheters will become dislodged as the fetus develops; a fetus typically requires 3 catheter replacements before completion of pregnancy. Vesicoamniotic shunting may improve perinatal survival, but at the expense of poor long-term renal function.

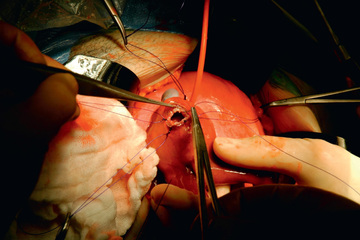

Fetal cystoscopy is more technically challenging than vesicoamniotic shunt placement, more invasive, and requires more sedation, but this option holds some important advantages. Cystoscopy allows for direct visualization of the obstruction and does not require amnioinfusion. Moreover, when the obstruction is visualized and the diagnosis of PUV confirmed, the valves can be treated, restoring urine flow to the amniotic space and eliminating the need for repeated fetal interventions in most patients. Creation of a vesicostomy (direct opening from bladder through fetal abdominal wall) by open fetal surgery has improved perinatal survival (Fig. 116.2 ). However, the current dataset evaluating this approach is still limited, and direct comparisons to shunting suggest no significant difference between these interventions.

Nonobstructive Renal Disease

Nonobstructive fetal renal disease can result from renal hypoplasia/dysplasia and from genetic disease such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Similar to obstructive uropathy, fetal therapy is focused on restoring amniotic fluid volume in patients with oligohydramnios or anhydramnios. However, restoration of amniotic fluid volume in nonobstructive renal disease requires external sources of amniotic fluid. Current treatment options include serial percutaneous amnioinfusion and infusion of fluid by amnioport. Serial amnioinfusions are less invasive as a single procedure, but most pregnancies will require weekly infusions to maintain adequate amniotic fluid volume. Amnioinfusion through an amnioport involves open surgical placement of a catheter into the amniotic space that is connected to an ex utero subcutaneous port. This allows repeated fluid infusion into the amniotic space. The amnioport is more challenging and invasive as an individual procedure but provides more reliable access to the amniotic space for the duration of the pregnancy. Small studies suggest both these procedures improve pulmonary outcomes and perinatal survival in infants with renal disease, but these infants will require dialysis and then renal transplant when the infant is large enough (2-3 yr of age).

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH ) is a defect in the fetal diaphragm causing herniation of the abdominal contents into the thorax and inhibition of fetal lung growth (see Chapter 122.10 ). CDH occurs in 1 in 3,000 births and can range from mild to severe. In mild cases of CDH, surgical repair of the diaphragm is typically performed in the 1st few days of life. Lungs in these infants are smaller than normal at birth, but as they grow, these patients can lead normal, active lives. In the severe cases of CDH infants experience severe pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in the perinatal period. Mortality is high in severely affected infants, and survivors often have long-term respiratory, feeding, and neurodevelopmental problems.

Early attempts at fetal intervention for CDH used in utero surgical correction of the diaphragm defect in severe CDH infants. Survival rates were poor, with most infants dying during or shortly after the fetal surgery. Since significant complications during this procedure involved reduction of the incarcerated liver, a follow-up study compared postnatal repair to in utero repair that was limited to infants without liver herniation in the chest. The fetal repair group had more premature delivery (32 vs 38 wk gestation) without an improvement in survival (75% fetal repair vs 86% postnatal repair). Therefore, attempts at in utero repair of CDH have been abandoned.

Occlusion of the fetal trachea causes lung growth, and this approach was capable of dramatically improving lung growth in animal models of pulmonary hypoplasia. Several groups explored the use of fetal tracheal occlusion in CDH. The fetal surgical team in Philadelphia evaluated both open fetal tracheal ligation and endoscopic tracheal occlusion with an inflatable balloon. Open fetal tracheal ligation was quickly abandoned, with most patients dying from either complications associated with the procedure or shortly after delivery from respiratory failure caused by the lack of alveolar type II cell maturation and surfactant production in the hyperexpanded lungs. Endoscopic balloon tracheal occlusion was eventually evaluated in a larger trial. Survival was better than open fetal tracheal ligation but still not improved over control patients. Development of fetoscopic balloon tracheal occlusion in CDH led to the multicenter prospective randomized Tracheal Occlusion to Accelerate Lung Growth (TOTAL ) study. In this trial the balloon was inserted at 27-30 wk and removed at 34 wk. This timing is based on the hypothesis that tracheal occlusion will promote lung expansion while removal of the balloon before delivery will promote alveolar type II cell maturation. Initial data suggest that this approach is associated with a high incidence of preterm delivery but a significant increase in survival. The use of fetoscopic tracheal occlusion in CDH therapy is gaining popularity, but this approach in both severe and moderate CDH is still under investigation.

Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM ), previously referred to as congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), is caused by abnormal branching and hamartomatous growth of the terminal respiratory structures that results in cystic and adenomatoid malformations (see Chapter 423 ). Although rare, these remain the most common congenital lung lesion. CPAMs usually arise between 5 and 22 wk of gestation and continue to increase in size until around the 26th wk of pregnancy. If large enough, CPAM can cause significant pulmonary hypoplasia and in severe cases, hydrops fetalis. The size of the CPAM is tracked by CPAM volume ratio (CVR ), an index that compares the volume of the CPAM to the fetal head circumference. Most studies indicate >95% survival in CPAM patients with no hydrops and CVR <1.6, with a much lower survival and greater risk for hydrops in patients with a CVR >1.6. Without intervention, CPAM with hydrops is uniformly fatal.

Open fetal resection of CPAM was considered one of the first clearly beneficial fetal surgeries. A less invasive option in fetal patients with CPAM composed of a large, dominant cyst is the insertion of a thoracoamniotic shunt into the dominant cyst. This decreases CPAM size, allowing lung growth and reducing risk of hydrops. An alternative surgical approach involving resection of the CPAM at delivery while the infant remains on placental support via an ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) procedure has also demonstrated improved survival in a select group of patients.

Patients (in utero) receiving corticosteroids experience improved survival compared with those receiving open fetal resection. Survival rates approach 100% in high-risk CPAM (CVR >1.6) treated with steroids before the onset of hydrops and 50% in patients who have developed hydrops. Therefore the current approach to fetal therapy for CPAM has been away from open fetal resection and toward single or multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids in fetuses with CVR >1.6.

Myelomeningocele

Before the introduction of fetal repair of myelomeningocele (MMC) , fetal surgery was limited to diagnoses considered fatal for the fetus or infant without intervention. However, a growing body of data suggests that the neurologic outcome in MMC is directly related to progressive injury from ongoing damage to the exposed spinal cord during pregnancy (see Chapter 609.3 ). Controversy remained as to whether the maternal and fetal risks of fetal repair should be accepted when the goal was to reduce postnatal morbidity rather than to improve survival.

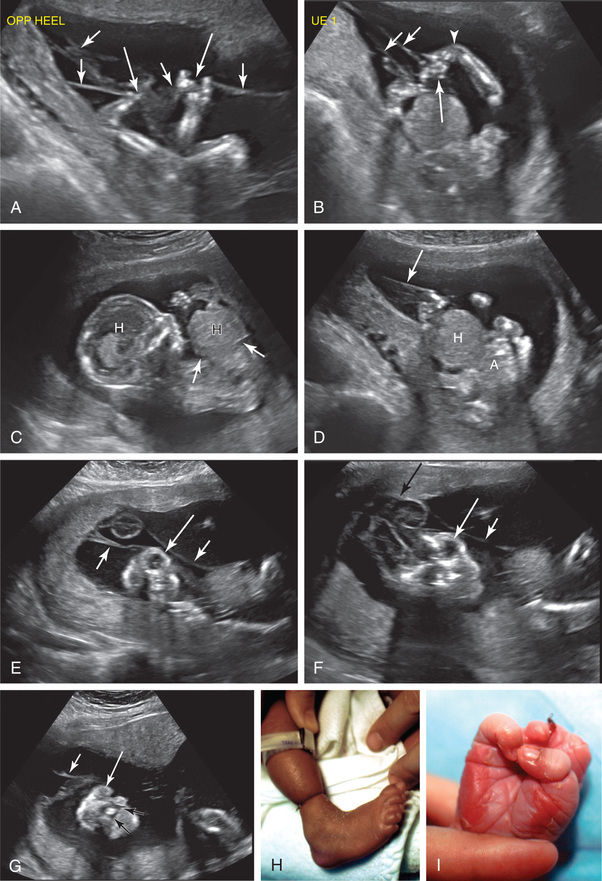

The observation in early studies that patients receiving open fetal MMC repair were less likely to require ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt prompted the prospective randomized trial of prenatal vs postnatal MMC management (MOMS) (Fig. 116.3 ). The study was closed to enrollment in 2010 after 183 patients were randomized and the data safety monitoring board determined a clear advantage for prenatal surgery. The MOMS trial demonstrated a significant reduction in the need for VP shunt in the fetal repair group (40% vs 82% in postnatal repair group). The fetal repair group had an improved composite score for mental development and motor function at 30 mo, but also an increased risk of preterm delivery and uterine dehiscence. The average gestational age at delivery in the fetal repair group was 34 wk, with 10% delivering at <30 wk, compared to 37 wk and no infants <30 wk in the postnatal repair group.

Open fetal repair of MMC has been an important advance but the risk of prematurity significantly decreases the benefit of this procedure. In theory, the less invasive fetoscopic MMC repair approach, which is being developed at a limited number of centers, should reduce maternal morbidity and prematurity rates associated with open fetal MMC repair (

Video 116.1).

Video 116.1).

Other Indications

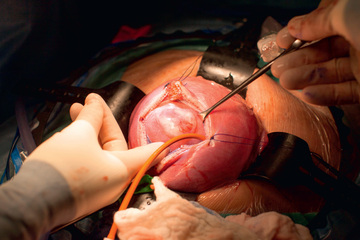

Antenatal intervention for cardiac defects, such as aortic stenosis, pulmonic stenosis, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), have been used to dilate, with balloon valvuloplasty, stenotic valves (aortic stenosis) to prevent further development of HLHS (creating biventricular physiology) (Fig. 116.4 ) (see Chapter 458.10 ).

Laser therapy has been used to treat twin-twin transfusions syndrome (Chapter 117.1 ) and amniotic bands (Fig. 116.5 ).

Fetal Centers

The value of fetal centers extends beyond fetal surgery. Often, families will present to a fetal center with a newly discovered diagnosis and little understanding of what the diagnosis means for their baby. Prenatal counseling by the fetal team can provide comfort to the family by helping them understand the diagnosis and treatment options and by developing a management plan that may include fetal surgery. Some plans may call for enhanced monitoring of the fetus and mother, followed by complex deliveries involving multidisciplinary delivery teams and specialized equipment, as required for EXIT to ECMO, EXIT to airway, EXIT to tumor resection, delivery to cardiac catheterization, and procedures on placental support. Other plans may focus on postnatal therapy.

Not all severely affected fetuses have available therapies in utero or after birth. In these lethal situations, fetal care planning will provide support for the family and a plan for delivery room or nursery palliative care (Table 116.3 ) (see Chapter 7 ).

Table 116.3

Selection of Patients for Fetal Repair

| LEVEL OF CERTAINTY | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| DIAGNOSTIC CERTAINTY/PROGNOSTIC CERTAINTY | |

| Genetic problems | Trisomy 13, 15, or 18 |

| Triploidy | |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | Anencephaly/acrania |

| Holoprosencephaly | |

| Large encephaloceles | |

| Heart problems | Acardia |

| Inoperable heart anomalies | |

| Kidney problems | Potter syndrome/renal agenesis |

| Multicystic/dysplastic kidneys | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | |

| DIAGNOSTIC UNCERTAINTY/PROGNOSTIC CERTAINTY | |

| Genetic problems | Thanatophoric dwarfism or lethal forms of osteogenesis imperfecta |

| Early oligo/anhydramnios and pulmonary hypoplasia | Potter syndrome with unknown etiology |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | Hydranencephaly |

| Congenital severe hydrocephalus with absent or minimal brain growth | |

| Prematurity | <23 wk gestation |

| PROGNOSTIC UNCERTAINTY/BEST INTEREST | |

| Genetic problems | Errors of metabolism that are expected to be lethal even with available therapy |

| Mid oligo/anhydramnios | Renal failure requiring dialysis |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | Complex or severe cases of meningomyelocele |

| Neurodegenerative diseases, such as spinal muscular atrophy | |

| Heart problems | Some cases of hypoplastic left heart syndrome |

| Pentalogy of Cantrell (ectopia cordis) | |

| Other structural anomalies | Some cases of giant omphalocele |

| Severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia with hypoplastic lungs | |

| Idiopathic nonimmune hydrops | |

| Inoperable conjoined twins | |

| Multiple severe anomalies | |

| Prematurity | 23-24 wk gestation |

From Leuthner SR: Fetal palliative care, Clin Perinatol 31:649–665, 2004 (Table 1, p 652).