Dysmorphology

Anne M. Slavotinek

Dysmorphology is the study of differences in human form and the mechanisms that cause them. It has been estimated that 1 in 40 newborns, or 2.5%, have a recognizable birth defect or pattern of malformations at birth; approximately half these newborns have a single, isolated malformation, whereas in the other half, multiple malformations are present. From 20–30% of infant deaths and 30–50% of deaths after the neonatal period are caused by congenital abnormalities (http://www.marchofdimes.com/peristats/ ). In 2001, birth defects accounted for 1 in 5 infant deaths in the United States, with a rate of 137.6 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was higher than other causes of mortality, such as preterm/low birthweight (109.5/100,000), sudden infant death syndrome (55.5/100,000), maternal complications of pregnancy (37.3/100,000), and respiratory distress syndrome (25.3/100,000).

Classification of Birth Defects

Birth defects can be subdivided into isolated (single) defects or multiple congenital anomalies (multiple defects) in one individual. An isolated primary defect can be classified, according to the nature of the presumed cause of the defect, as a malformation, dysplasia, deformation, or disruption (Table 128.1 and Fig. 128.1 ). Most birth defects are malformations. A malformation is a structural defect arising from a localized error in morphogenesis that results in the abnormal formation of a tissue or organ. Dysplasia refers to the abnormal organization of cells into tissues. Malformations and dysplasias can both affect intrinsic structure. In contrast, a deformation is an alteration in shape or structure of a structure or organ that has developed, or differentiated, normally. A disruption is a defect resulting from the destruction of a structure that had formed normally before the insult.

Table 128.1

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy , ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier Saunders.

Most inherited human disorders with altered morphogenesis display multiple malformations rather than isolated birth defects. When several malformations coexist in a single individual, they can be classified as a syndrome, sequence, or an association. A syndrome is defined as a pattern of multiple abnormalities that are related by pathophysiology, resulting from a single, defined etiology. Sequences consist of multiple malformations that are caused by a single event, although the sequence itself can have different etiologies. An association refers to a nonrandom grouping of malformations in which there is an unclear, or unknown, relationship among the malformations, such that they do not fit the criteria for a syndrome or sequence.

Malformations and Dysplasias

Human malformations and dysplasias can be caused by gene mutations, chromosome aberrations and copy number variants, environmental factors, or interactions between genetic and environmental factors (Table 128.2 ). Some malformations are caused by deleterious sequence variants in single genes, whereas other malformations arise because of deleterious sequence variants in multiple genes acting in combination (digenic or oligogenic inheritance). In 1996 it was thought that malformations were caused by monogenic defects in 7.5% of patients; chromosomal anomalies in 6%; multigenic defects in 20%; and known environmental factors, such as maternal diseases, infections, and teratogens, in 6–7% (Table 128.3 ). In the remaining 60–70% of patients, malformations were classified as caused by unknown etiologies. Currently, the percentages have increased for all categories of known causes of malformations, the result of improved cytogenetic and molecular genetic methods for detecting small chromosomal abnormalities and next-generation sequencing studies that can screen multiple genes simultaneously and identify novel genes and deleterious sequence variants.

Table 128.2

Examples of Malformations with Distinct Causes, Clinical Features, and Pathogenesis

| DISORDER | CAUSE/INHERITANCE | SELECTED CLINICAL FEATURES | PATHOGENESIS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spondylocostal dysostosis syndrome | Mendelian; autosomal recessive | Abnormal vertebral and rib segmentation | Deleterious sequence variants in DLL3 and other genes |

| Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome | Autosomal dominant |

Intellectual disability Broad thumbs and halluces; valgus deviation of these digits Hypoplastic maxillae Prominent nose and columella Congenital heart disease |

Deleterious sequence variants in CBP and EP300 |

| X-linked lissencephaly | X-linked |

Male: severe intellectual disability, seizures Female: variable |

Deleterious sequence variants in DCX |

| Aniridia | Autosomal dominant | Absent iris or iris/foveal hypoplasia | Deleterious sequence variants in PAX6 |

| Waardenburg syndrome, type I | Autosomal dominant |

Deafness White forelock Wide-spaced eyes Iris heterochromia and/or pale skin pigmentation |

Deleterious sequence variants in PAX3 |

| Holoprosencephaly | Loss of function or heterozygosity for multiple genes | Microcephaly | SHH, multiple other genes |

| Cyclopia | |||

| Single central incisor | |||

| Velocardiofacial syndrome |

Microdeletion 22q11.2 |

Congenital heart disease, including conotruncal defects | TBX1 haploinsufficiency/mutations; haploinsufficiency for other genes in the deleted interval also contributes to the phenotype. |

| Cleft palate | |||

| T-cell defects | |||

| Facial anomalies | |||

| Down syndrome | Additional copy of chromosome 21 (trisomy 21) | Intellectual disability | Increase in dosage of an estimated 250 genes on chromosome 21 |

| Characteristic dysmorphic features | |||

| Congenital heart disease | |||

| Increased risk of leukemia | |||

| Alzheimer disease | |||

| Neural tube defects | Multifactorial | Meningomyelocele | Defects in folate sensitive enzymes or folic acid uptake |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | Teratogenic | Microcephaly | Ethanol toxicity to developing brain |

| Developmental delay | |||

| Facial abnormalities | |||

| Behavioral abnormalities | |||

| Retinoic acid embryopathy | Teratogenic | Microtia | Isotretinoin effects on neural crest and branchial arch development |

| Congenital heart disease |

Table 128.3

Causes of Congenital Malformations

| MONOGENIC |

| CHROMOSOMAL ABERRATIONS and COPY NUMBER VARIANTS |

| MATERNAL INFECTION |

| MATERNAL ILLNESS |

| UTERINE ENVIRONMENT |

| ENVIRONMENTAL AGENTS |

| MEDICATIONS |

| UNKNOWN ETIOLOGIES |

| SPORADIC SEQUENCE COMPLEXES |

| NUTRITIONAL |

From Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, editors: Nelson's essentials of pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, Saunders.

Many developmental abnormalities that are caused by deleterious sequence variants (mutations)in a single gene display characteristic, mendelian patterns of inheritance (autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked inheritance). Genes that cause birth defects or multiple congenital anomaly syndromes are often transcription factors, part of evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathways, or regulatory proteins required for key developmental events (Figs. 128.2 and 128.3 ). Examples include spondylocostal dysostosis syndromes, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, and X-linked lissencephaly (“smooth brain”) syndrome (see Table 128.2 ).

Patients with spondylocostal dysostosis (SCD) display a characteristic pattern of vertebral segmentation defects associated with a number of other malformations, such as neural tube defects. The SCD syndromes are etiologically heterogeneous and are often caused by mutations in the gene coding for delta-like 3 (DLL3 ), a ligand of the Notch receptors. The Notch/delta pathway is conserved throughout evolution and regulates a number of developmental events. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS) results from mutations in the sterol delta-7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7 ) gene, an enzyme critical for normal cholesterol biosynthesis. Patients with SLOS (see Fig. 128.2 ) display syndactyly (fusion of the fingers and toes), in particular affecting the 2nd and 3rd toes; postaxial polydactyly (extra digits); anteverted (upturned) nose; ptosis; cryptorchidism; and holoprosencephaly (failure of separation of the 2 cerebral hemispheres). Many of the features in SLOS are shared with those arising from deleterious sequence variants in the SHH genes, and these mutations link cholesterol biosynthesis pathogenically to the sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathway, because SHH is posttranslationally modified by cholesterol (see Chapter 97 ). Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (see Fig. 128.2 ) typically results from heterozygous, loss-of-function deleterious sequence variants in a gene coding for a broadly acting transcriptional coactivator called CREB-binding protein (CBP) and from deleterious sequence variants in the EP300 gene. The CBP coactivator regulates the transcription of a number of genes, which is why patients with deleterious sequence variants in CBP have a pleiotropic phenotype that includes developmental delays and intellectual disability, broad and angulated thumbs and halluces (1st toes), and congenital heart disease. One of the transcription factors that binds to CBP is GLI3, a member of the SHH pathway (see Fig. 128.2 ). X-linked lissencephaly is a severe neuronal migration defect that causes a smooth brain with reduction or absence of gyri and sulci in males and that gives rise to a variable pattern of intellectual disability and seizures in females. X-linked lissencephaly is caused by deleterious sequence variants in DCX . The DCX protein regulates the activity of dynein motors that contribute to movement of the cell nucleus during neuronal migration.

Malformation syndromes can also be caused by chromosomal aberrations or copy number variants and teratogens (see Tables 128.2 and 128.3 ). Down syndrome typically results from an extra copy of an entire chromosome 21 or, less frequently, an extra copy of the Down syndrome critical region on chromosome 21. Chromosome 21 is a small chromosome that contains an estimated 250 genes, and thus individuals with Down syndrome typically have an increased dosage of the numerous genes encoded by this chromosome that causes their physical differences (see Chapter 98.2 ).

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are an example of a birth defect that displays multifactorial inheritance in most cases. NTDs and a number of other congenital malformations, such as cleft lip and palate, can recur in families, but inheritance for the majority of affected individuals does not occur in a straightforward, mendelian inheritance pattern, and in this situation, multiple genes and environmental factors together likely contribute to the pathogenesis (see Table 128.2 ). Many of the genes involved in NTDs are unknown, so one cannot predict with certainty the mode of inheritance or a precise recurrence risk in the individual case. Empirical recurrence risks can be provided on the basis of population studies and the presence of single or multiple family members with the same malformation. However, one important gene/environment interaction has been identified for NTDs (see Chapter 609.1 ). Folic acid deficiency is associated with NTDs and can result from a combination of dietary factors and increased utilization during pregnancy. A common variant in the gene for an enzyme in the folate recycling pathway, 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR ), that makes this enzyme less stable, may also be important in folic acid status. Several teratogenic causes of birth defects have been described (see Tables 128.2 and 128.3 ). Ethanol causes a recognizable malformation syndrome that is variably called fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), or fetal alcohol effects (FAE) (see Chapter 126.3 ). Children who were exposed to ethanol during the pregnancy can display microcephaly, developmental delays, hyperactivity, and facial dysmorphic features. Ethanol, which is toxic to the developing central nervous system (CNS), causes cell death in developing neurons.

Deformations

Many deformations involve the musculoskeletal system (Fig. 128.4 ). Fetal movement is required for the proper development of the musculoskeletal system, and restriction of fetal movement can cause musculoskeletal deformations such as clubfoot (talipes). Two major intrinsic causes of deformations are primary neuromuscular disorders and oligohydramnios, or decreased amniotic fluid, which can be caused by fetal renal defects. The major extrinsic causes of deformation are those that result in fetal crowding and restriction of fetal movement. Examples of extrinsic causes include oligohydramnios resulting from chronic leakage of amniotic fluid and abnormal shape of the amniotic cavity. When a fetus is in the breech position (Fig. 128.5 ), the incidence of deformations is increased 10-fold. The shape of the amniotic cavity also has a profound effect on the shape of the fetus and is influenced by many factors, including uterine shape, volume of amniotic fluid, and the size and shape of the fetus (Fig. 128.6 ).

It is important to determine whether deformations result from intrinsic or extrinsic causes. Most children with deformations from extrinsic causes are otherwise completely normal, and their prognosis is usually excellent. Correction typically occurs spontaneously. Deformations caused by intrinsic factors, such as multiple joint contractures resulting from CNS or peripheral nervous system defects, have a different prognosis and may be much more significant for the child (Fig. 128.7 ).

Disruptions

Disruptions are caused by destruction of a previously normally formed organ or body part. At least 2 mechanisms are known to produce disruptions. One involves entanglement, followed by tearing apart or amputation, of a normally developed structure, usually a digit or limb, by strands of amnion floating within amniotic fluid (amniotic bands) (Fig. 128.8 ). The other mechanism involves interruption to the blood supply to a developing part, which can lead to infarction, necrosis, and resorption of structures distal to the insult. If interruption to the blood supply occurs early in gestation, the disruptive defect typically involves atresia, or absence of a body part. Genetic factors were previously considered to play a minor role in the pathogenesis of disruptions; most occur as sporadic events in otherwise healthy individuals. The prognosis for a disruptive defect is determined entirely by the extent and location of the tissue loss.

Multiple Anomalies: Syndromes and Sequences

The pattern of multiple anomalies that occurs when a single primary defect in early development produces multiple abnormalities because of a cascade of secondary and tertiary developmental anomalies is called a sequence (see Fig. 128.9 ). When evaluating a child with multiple congenital anomalies, the physician must differentiate between multiple anomalies that are caused by a single localized error in morphogenesis (a sequence) from syndromes with multiple malformations. In the former, recurrence risk counseling for the multiple anomalies depends entirely on the risk of recurrence for the single, localized malformation. Pierre-Robin sequence is a pattern of multiple anomalies produced by mandibular hypoplasia. Because the tongue is relatively large for the oral cavity, it drops back (glossoptosis), blocking closure of the posterior palatal shelves and causing a U -shaped cleft palate. There are numerous causes of mandibular hypoplasia, all of which can result in characteristic features of Pierre-Robin sequence.

Molecular Mechanisms of Malformations

Inborn Errors of Development

Genes that cause malformation syndromes (as well as genes whose expression is disrupted by environmental agents or teratogens) can be part of numerous cellular processes, including evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathways, transcription factors, or regulatory proteins required for key developmental events. When malformations are considered as alterations resulting from disturbances to important developmental pathways, this provides a molecular framework for understanding the birth defects.

Sonic Hedgehog Pathway As Model

The SHH pathway is developmentally important during embryogenesis to induce controlled proliferation in a tissue-specific manner; disruption of specific steps in this pathway results in a variety of related developmental disorders and malformations (see Fig. 128.2 ). Activation of this pathway in the adult leads to abnormal proliferation and cancer. The SHH pathway transduces an external signal, in the form of a ligand, into changes in gene transcription by binding of the ligand to specific cellular receptors. SHH is a ligand expressed in the embryo in regions important for development of the brain, face, limbs, and the gut.

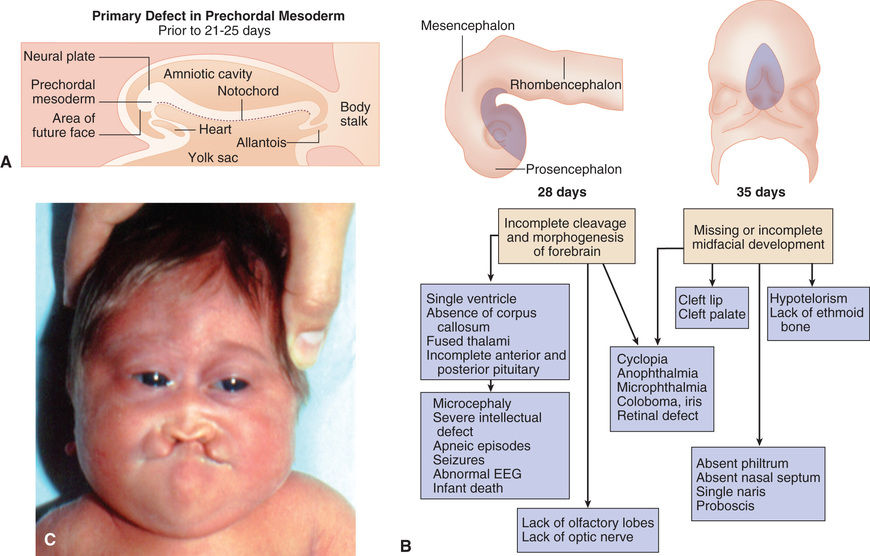

Deleterious sequence variants in SHH can cause holoprosencephaly (see Fig. 128.2 ), a variably severe, midline defect associated with clinical effects ranging from cyclopia to a single maxillary incisor with hypotelorism or close spacing of the ocular orbits. The SHH protein is processed by proteolytic cleavage to an active N-terminal form, which is then further modified by the addition of cholesterol. Defects in cholesterol biosynthesis, in particular the sterol, delta-7-dehydrocholesterol reductase gene, result in SLOS , which is also associated with holoprosencephaly. The modified and active form of SHH binds to its transmembrane receptor Patched (PTCH1). SHH binding to PTCH1 inhibits the activity of the transmembrane protein Smoothened (SMO). SMO act to suppress downstream targets of the SHH pathway, the GLI family of transcription factors, so inhibition of SMO by PTCH1 results in activation of GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3, resulting in alteration of transcription of GLI targets. PTCH1 and its orthologue, PTCH2 , can act as tumor suppressors, and somatic, inactivating sequence variants can be associated with loss of tumor suppressor function, whereas activating mutations in SMO can also be oncogenic, particularly in basal cell carcinomas and medulloblastomas. Germline, inactivating mutations in PTCH1 result in Gorlin syndrome (see Fig. 128.4 ), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by dysmorphic features (broad face, dental anomalies, rib defects, short metacarpals), basal cell nevi that can undergo malignant transformation, and an increased risk of cancers, including medulloblastomas and rhabdomyosarcomas. GLI1 amplification has been found in several human tumors, including glioblastoma, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and B cell lymphomas; mutations or alterations in GLI3 have been found in Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS), Pallister-Hall syndrome ( PHS), postaxial polydactyly type A (and A/B), and preaxial polydactyly type IV (see Fig. 128.2 ). GCPS consists of hypertelorism (wide-spaced eyes), syndactyly, preaxial polydactyly, and broad thumbs and halluces. PHS is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by postaxial polydactyly, syndactyly, hypothalamic hamartomas, imperforate anus, and occasionally holoprosencephaly. GLI3 binds to CBP, the protein that is haploinsufficient in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome .

Disorders that are caused by mutations in genes that function together in a developmental pathway typically have overlapping clinical manifestations. In this case, the overlapping features result from the expression domains of SHH that are important for development of the brain, face, limbs, and gut. Brain defects are found in holoprosencephaly (Fig. 128.9 ), SLOS, and PHS. Facial abnormalities are found in holoprosencephaly, SLOS, Gorlin syndrome, GCPS, and PHS. Limb defects are found in SLOS, Gorlin syndrome, GCPS, PHS, and the polydactyly syndromes. Overexpression, or activating mutations, affecting the SHH pathway results in cancer, including basal cell carcinomas, medulloblastomas, glioblastomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas.

The SHH pathway interaction with the primary cilium is critical to transduce the SHH extracellular signal through to the nuclear machinery. A number of disorders, including Bardet-Biedl syndrome, oral-facial-digital (OFD) syndrome type I, and Joubert syndrome, are caused by mutations in genes that function in the primary cilium. These disorders, called ciliopathies , overlap clinically with some of the phenotypic features described previously, again demonstrating that perturbations of conserved developmental pathways can cause overlapping presentations (Table 128.4 ).

Table 128.4

Childhood Diseases and Syndromes Associated with Motile and Sensory Ciliopathies

| PEDIATRIC CILIOPATHY | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS | SELECTED GENE(S) |

|---|---|---|

| MOTOR | ||

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia | Chronic bronchitis, rhinosinusitis, otitis media, laterality defects, infertility, CHD | DNAI1, DNAH5, DNAH11, DNAI2, KTU, TXNDC3, LRRC50, RSPH9, RSPH4A, CCDC40, CCDC39 |

| SENSORY | ||

| Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease | RFD, CHF | PKHD1 |

| Nephronophthisis | RFD, interstitial nephritis, CHF, RP | NPHP1-8, ALMS1, CEP290 |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | Obesity, polydactyly, ID, RP, renal anomalies, anosmia, CHD | BBS1-12, MKS1, MKS3, CEP290 |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | RFD, polydactyly, ID, CNS anomalies, CHD, cleft lip, cleft palate | MKS1-6, CC2D2A, CEP290, TMEM216 |

| Joubert syndrome | CNS anomalies, ID, ataxia, RP, polydactyly, cleft lip, cleft palate | NPHP1, JBTS1, JBTS3, JBTS4, CORS2, AHI1, CEP290, TMEM216 |

| Alstrom syndrome | Obesity, RP, DM, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, skeletal dysplasia, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary fibrosis | ALMS1 |

| Orofaciodigital syndrome type I | Polydactyly, syndactyly, cleft lip, cleft palate, CNS anomalies, ID, RFD | OFD1 |

| Ellis van Creveld syndrome | Chondrodystrophy, polydactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, CHD | EVC, EVC2 |

| Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy | Narrow thorax, RFD, RP, dwarfism, polydactyly | IFT80 |

| Sensenbrenner syndrome | Dolichocephaly, ectodermal dysplasia, dental dysplasia, narrow thorax, RFD, CHD | IFT122, IFT43, WDR35 |

| Short rib–polydactyly syndromes | Narrow thorax, short limb dwarfism, polydactyly, renal dysplasia | WDR35, DYNC2H1, NEK1 |

CHD, Congenital heart disease; CHF, congenital hepatic fibrosis; CNS, central nervous system; DM, diabetes mellitus; ID, intellectual disabilities; RFD, renal fibrocystic disease; RP, retinitis pigmentosa.

From Ferkol TW, Leigh MW: Ciliopathies: the central role of cilia in a spectrum of pediatric disorders, J Pediatr 160:366–371, 2012.

Cytogenetic Aberrations and Chromosomal Imbalance

Cytogenetic imbalances resulting from an additional copy of a whole human chromosome can result in characteristic and recognizable syndromes. An additional copy of chromosome 21 results in Down syndrome (see Chapter 98.2 ); loss of one of the X chromosomes results in Turner syndrome (see Chapter 98 for discussion of syndromes with whole chromosomal imbalances). With the advent of high-resolution cytogenetic techniques, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH), and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays, it has become possible to identify submicroscopic chromosome deletions and duplications . A number of recurrent deletions and duplications have been identified that cause characteristic and recognizable syndromes, including Williams syndrome (deletion of chromosome 7q11.23), Miller-Dieker syndrome (deletion of chromosome 17p13.3), Smith-Magenis syndrome (deletion of chromosome 17p11.2), and 22q11 deletion syndrome (deletion of chromosome 22q11.2, also known as velocardiofacial/DiGeorge syndrome ). Array CGH and SNP arrays have also made it possible to uncover rarer microdeletions and microduplications associated with birth defects, intellectual disability, and neuropsychiatric disorders. The sensitivity and specificity chromosome microarrays have made this the technique of choice for the initial evaluation of a child with multiple congenital anomalies and/or intellectual disability, although it is important to note that all individuals may carry numerous small microdeletions and microduplications as normal or familial variation. Therefore, it is important to compare copy number variants in these children with birth defects with their parents’ chromosome analyses and with databases of normal variants detected in individuals without such birth defects.

Approach to the Dysmorphic Child

One approach to the dysmorphic child is the pattern recognition approach, which compares the manifestations in the patient against a broad and memorized (or computerized) knowledge of human pleiotropic disorders. Although this approach can be appropriate for a small number of experienced dysmorphologists, a systematic genetic mechanism approach can also be effective for clinicians who are not dysmorphology experts. By gathering and analyzing the clinical data, the general pediatrician can diagnose the patient in a straightforward case or initiate a referral to an appropriate specialist.

Medical History

The history for a patient with birth defects includes a number of elements related to etiologic factors. The pedigree or family history is necessary to assess the inheritance pattern, or lack thereof, for the disorder. For disorders that have a simple mendelian inheritance pattern, its recognition can be critical for narrowing the differential diagnosis, then prioritizing common genes with the appropriate inheritance pattern causing the patient's clinical features. A number of common birth defects have a complex or multifactorial genetic etiology, such as isolated cleft palate and spina bifida. The recognition of a close relative affected with a birth defect that is similar to that in the proband can be useful. Typically, a 3-generation pedigree is sufficient for this purpose (see Chapter 97 ).

The perinatal history is also an essential component of the history. It includes the pregnancy history of the mother (useful for recognition of recurrent miscarriages that may be indicative of a chromosomal disorder), factors that may relate to deformations or disruptions (oligohydramnios), and maternal exposures to teratogenic drugs or chemicals (isotretinoin and ethanol are potential causes of microcephaly).

Another component of the history that is often useful is the natural history of the phenotype . Malformation syndromes caused by chromosomal aberrations and single-gene disorders are frequently static, meaning that, although the patients can experience new complications over time, the phenotype is typically not progressive. In contrast, disorders that cause dysmorphic features because of metabolic perturbations (e.g., Hunter or Sanfilippo syndrome) can be mild or may not be apparent at birth, but they can progress relentlessly, causing deterioration of patient status over time.

Physical Examination

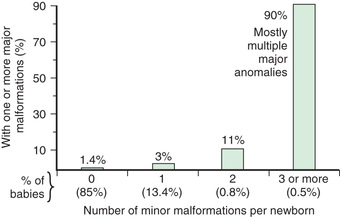

The physical examination is very important for the diagnosis of a dysmorphic syndrome. The essential element of the physical evaluation is an objective assessment of the patient's clinical findings. The clinician needs to perform an organized evaluation of the size and formation of various body structures. Familiarity with the nomenclature of dysmorphic signs is helpful (Table 128.5 ). The size and shape of the head is relevant; for example, many children with Down syndrome have mild microcephaly and brachycephaly (shortened anteroposterior dimension of skull). Eye position and shape are useful signs for many disorders. Reference standards are available with which physical measurements (e.g., interpupillary distance) can also be compared. It is also useful to categorize abnormalities as “major” or “minor” birth defects. Major defects either cause significant dysfunction (e.g., absence of a digit) or require surgical correction (e.g., polydactyly), and minor defects neither cause significant dysfunction nor require surgical correction (e.g, mild clinodactyly) (Table 128.6 and Fig. 128.10 ). By cataloging physical parameters, the clinician may be able to recognize the diagnosis.

Table 128.5

Table 128.6

Minor Anomalies and Phenotype Variants*

| CRANIOFACIAL |

| EYE |

| EAR |

| SKIN |

| HAND |

| FOOT |

| OTHER |

* Approximately 15% of newborns have 1 minor anomaly, 0.8% have 2 minor anomalies, and 0.5% have 3. If 2 minor anomalies are present, the probability of an underlying syndrome or a major anomaly (congenital heart disease, renal, central nervous system, limbic) is 5-fold that in the general population. If 3 minor anomalies are present, there is a 20–30% probability of a major anomaly.

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy , ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier Saunders.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies can be critical in diagnosing an underlying genetic etiology. If short stature or disproportionate stature (e.g., long trunk and short limbs) is noted, a full skeletal survey with radiographs should be performed. The skeletal survey can detect anomalies in bone number or structure that can be used to narrow the differential diagnosis. When there are abnormal neurologic signs or symptoms, such as microcephaly or hypotonia, brain imaging can be indicated. Other studies, such as echocardiography and renal ultrasonography, can also be useful to identify additional major or minor malformations that may serve as diagnostic clues.

Diagnosis

The examining physician should gather data on the patient's pedigree and perinatal and pediatric (for older children) history and should have an appreciation for the natural history of the clinical findings. At this point, the physician has examined the child, identified atypical physical features, and obtained appropriate imaging studies.

The clinician should now attempt to organize the findings to elucidate potential developmental processes. An assessment based on specificity can be helpful for this process. If a child has multiple findings, such as a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), mild growth restriction, mild microcephaly, and holoprosencephaly, micropenis, and ptosis, a selection of the rarer or pathognomonic findings may be prioritized. The PDA, ptosis, mild growth restriction, and mild microcephaly are considered to be largely nonspecific findings (present in many disorders or often present as isolated features that are not part of a syndrome), whereas holoprosencephaly and micropenis are present in fewer syndromes and are not considered part of normal variation. The clinician can therefore search for disorders that include both holoprosencephaly and micropenis. The search can be performed manually using the features index of a textbook such as Smith's Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation or a computerized database such as Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Searching for both holoprosencephaly and micropenis returns a list of diagnostic possibilities, and the physician can then return to the patient to examine for additional features of the leading possible candidate disorders. Appropriate genetic testing can then be undertaken to confirm the clinician's hypothesis and verify the diagnosis.

Laboratory Studies and Genetic Testing

The laboratory evaluation of the dysmorphic child can be critical to reach or confirm the correct diagnosis. Cytogenetic studies with Giemsa-banded (G-banded) chromosome analysis, or karyotyping, was the gold standard previously performed in the evaluation of a dysmorphic patient. Array CGH and SNP arrays enable copy number variant detection and, in the case of SNP arrays, evaluation of loss of heterozygosity. Chromosome deletion syndromes may also be identified with specific and sensitive FISH analysis (Table 128.7 ). These tests are the most sensitive methods for the detection of cytogenetic alterations associated with birth defects and multiple congenital anomalies.

Table 128.7

CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WAGR, Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and mental retardation.

From Kliegman RM, Lye PS, et al, editors: Nelson pediatric symptom-based diagnosis, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier (Table 25-10).

Molecular testing for deleterious sequence variants that cause pleiotropic malformation syndromes is also available for many disorders as clinical or research testing. In most cases, however, such testing should not be performed indiscriminately, but instead should be ordered thoughtfully after the differential diagnosis has been considered. The introduction of next-generation sequencing has led to the identification of innumerable novel genes and revolutionized the testing that is now available for patients and families with intellectual disability, birth defects, or other suspected genetic diseases. A strong suspicion of a genetic diagnosis warrants consideration of testing to confirm the diagnosis, facilitate patient treatment and anticipatory guidance, clarify recurrence risks, and enable carrier testing for relevant inheritance patterns. Single nucleotide variants, exons, or genes are tested by Sanger sequencing targeting single or multiple exons. However, for diagnoses that have substantial genetic heterogeneity (e.g., hearing loss), panel testing, in which multiple relevant genes can be interrogated for single nucleotide variants, gene deletions, and gene duplications, is more expeditious than Sanger sequencing. Panel tests also frequently have the advantage of providing high coverage for the genes on the panel, compared to coverage for the same genes obtained by exome sequencing. However, in situations with diagnostic uncertainty, such as the investigation of a child with intellectual disability and dysmorphic features, for which there is no clinically recognizable pattern, exome sequencing may be most useful as a broad testing approach. Whole exome sequencing (WES) examines approximately 200,000 exons, or the 1–2% of the DNA that comprises the coding regions of the genome. WES is typically performed with a trio approach, in which the patient and both biological parents are tested simultaneously, so that the inheritance pattern, or segregation, of deleterious sequence variants can be determined, thus simplifying analysis. Trio sequencing has resulted in higher diagnostic yields than proband-only sequencing and can approach 30–40% for indications such as intellectual disability. In contrast, whole genome sequencing (WGS) examines all the DNA content, including noncoding regions, and includes analysis for cytogenetic rearrangements in addition to copy number loss or gain. WES and WGS are applicable to a wide range of birth defects and genetic diseases and can discover causative variants in known or novel genes associated with a particular condition.

Management and Counseling

Management of the affected patient and genetic counseling are essential aspects of the approach to the dysmorphic patient. Children with Down syndrome have a high incidence of hypothyroidism, and children with achondroplasia have a high incidence of cervicomedullary junction abnormalities. One of the many benefits of an early and accurate diagnosis is that anticipatory guidance and medical monitoring of patients for syndrome-specific medical risks can prolong and improve their quality of life. When a diagnosis is made, the treating physicians can access published information on the natural history and management of the disorder through published papers, genetics reference texts, and databases.

The 2nd major benefit of an accurate diagnosis is that it provides data for appropriate recurrence risk estimates. Genetic disorders may have direct effects on only 1 member of the family, but the diagnosis of the condition can have implications for the entire family. One or both parents may be carriers; siblings may be carriers or may want to know their genetic status when they reach their reproductive years. Recurrence risk provision is an important component of genetic counseling and should be included in all evaluations for families affected with birth defects or other inherited disorders (see Chapter 94 ).