Immunodeficiencies Affecting Multiple Cell Types

Jennifer R. Heimall, Jennifer W. Leiding, Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

The manifestations of immune deficiencies that affect multiple cell types range from profound to mild; these conditions can present with severe infection, recurrent infections, unusual infections, or autoimmunity. The most profound disorder is severe combined immunodeficiency. Other combined immunodeficiencies include defects of innate immunity and defects leading to immune dysregulation; the latter category is typically associated with profound autoimmunity. Combined immunodeficiencies are characterized by a predisposition to viral infections, and the innate immunodeficiencies are susceptible to a range of bacteria.

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency

Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID ) is caused by diverse genetic mutations that lead to absence of T- and B-cell function. Patients with this group of disorders have the most severe immunodeficiency.

Pathogenesis

SCID is caused by mutations in genes crucial for lymphoid cell development (Table 152.1 and Fig. 152.1 ). All patients with SCID have very small thymuses that contain no thymocytes and lack corticomedullary distinction or Hassall corpuscles. The thymic epithelium appears histologically normal. Both the follicular and the paracortical areas of the spleen are depleted of lymphocytes. Lymph nodes, tonsils, adenoids, and Peyer patches are absent or extremely underdeveloped.

Table 152.1

Genetic Basis of SCID and SCID Variants

| DISEASE | INHERITANCE | PRESUMED PATHOGENESIS | ADDITIONAL FEATURES | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reticular dysgenesis | AR | Impaired mitochondrial energy metabolism and leukocyte differentiation | Severe neutropenia, deafness. Mutations in adenylate kinase 2 | GCSF, HSCT |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | AR | Accumulation of toxic purine nucleosides | Neurologic, hepatic, renal, lung, and skeletal and bone marrow abnormalities | HSCT, PEG-ADA, gene therapy |

| IL-2Rγ deficiency | X-linked | Abnormal signaling through by IL-2 receptor and other receptors containing γc (IL-4, -7, -9, -15, -21) | None | HSCT |

| Jak3 deficiency | AR | Abnormal signaling downstream of γc | None | HSCT |

| RAG1 and RAG2 deficiency | AR | Defective V(D)J recombination | None | HSCT |

| Artemis deficiency | AR | Defective V(D)J recombination, radiation sensitivity | DCLERE1C gene defects | HSCT |

| DNA-PK deficiency | AR | Defective V(D)J recombination | None | HSCT |

| DNA ligase IV deficiency | AR | Defective V(D)J recombination, radiation sensitivity | Growth delay, microcephaly, bone marrow abnormalities, lymphoid malignancies | HSCT |

| Cernunnos-XLF | AR | Defective V(D)J recombination, radiation sensitivity | Growth delay, microcephaly, birdlike facies, bone defects | HSCT |

| CD3δ deficiency | AR | Arrest of thymocytes differentiation at CD4− CD8− stage | Thymus size may be normal | HSCT |

| CD3ε deficiency | AR | Arrest of thymocytes differentiation at CD4− CD8− stage | γ/δ T cells absent | HSCT |

| CD3ζ deficiency | AR | Abnormal signaling | None | HSCT |

| IL-7Rα deficiency | AR | Abnormal IL-7R signaling | Thymus absent | HSCT |

| CD45 deficiency | AR | None | HSCT | |

| Coronin-1A deficiency | AR | Abnormal T-cell egress from thymus and lymph nodes | Normal thymus size. Attention deficit disorder. | HSCT |

AR, Autosomal recessive; GCSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IL, interleukin; Jak3, Janus kinase 3; PEG-ADA, polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase; RAG1, RAG2, recombinase-activating genes 1 and 2; V(D)J, variable, diversity, joining domains.

(Adapted from Roifman, CM. Grunebaum E: Primary T-cell immunodeficiencies. In Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT, et al, editors: Clinical immunology, ed 4. Philadelphia, 2013, Saunders, pp 440–441).

Clinical Manifestations

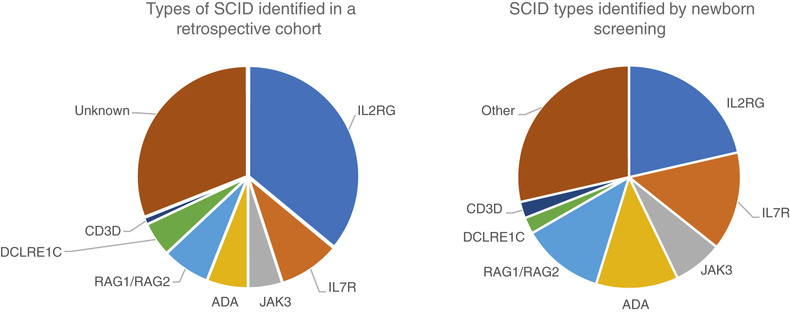

SCID is included in the newborn screening program in many states. Thus, infants are identified prior to symptoms, which has dramatically improved the survival of infants with SCID. A few genetic types of SCID are not detected by newborn screening, and there are a few states where newborn screening for SCID is not yet performed.

When infants with SCID are not detected through newborn screening, they most often present with infection . Diarrhea, pneumonia, otitis media, sepsis, and cutaneous infections are common presentations. Infections with a variety of opportunistic organisms, either through direct exposure or immunization, can lead to death. Potential threats include Candida albicans, Pneumocystis jiroveci , parainfluenza 3 virus, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rotavirus vaccine, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), varicella-zoster virus, measles virus, MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, varicella) vaccine, or bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Affected infants also lack the ability to reject foreign tissue and are therefore at risk for severe or fatal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) from T lymphocytes in nonirradiated blood products or maternal immunocompetent T cells that crossed the placenta while the infant was in utero. This devastating presentation is characterized by expansion of the allogeneic cells, rash, hepatosplenomegaly and diarrhea. A 3rd presentation is often called Omenn syndrome , in which a few cells generated in the infant expand and cause a clinical picture similar to GVHD (Fig. 152.2 ). The difference in this case is that the cells are the infant's own cells.

A key feature of SCID is that almost all patients will have a low lymphocyte count. A combination of opportunistic infections and a persistently low lymphocyte count is an indication to test for SCID. The diagnostic strategy both for symptomatic infants and those detected by newborn screening is to perform flow cytometry to quantitate the T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells in the infant. The CD45RA and CD45RO markers can be helpful to distinguish maternal engraftment and Omenn syndrome. T-cell function is also often assessed by measuring proliferative responses to stimulation.

All genetic types of SCID are associated with profound immunodeficiency. A small number have other associated features or atypical features that are important to recognize. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency can be associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and chondroosseous dysplasia. Adenylate kinase 2 (AK2) deficiency causes a picture referred to as reticular dysgenesis where neutrophils, myeloid cells, and lymphocytes are all low. This condition is also often associated with deafness.

Treatment

SCID is a true pediatric immunologic emergency. Unless immunologic reconstitution is achieved through hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT ) or gene therapy, death usually occurs during the 1st yr of life and almost invariably before 2 yr of age. HSCT in an infant prior to infection is associated with a 95% survival rate. ADA-deficient SCID and X-linked SCID have been treated successfully with gene therapy. Early trials of gene therapy were associated with a risk of malignancy, but this has not been seen in trials with new vectors. ADA-deficient SCID can also be treated with repeated injections of polyethylene glycol–modified bovine ADA (PEG-ADA ), although the immune reconstitution achieved is not as effective as with stem cell or gene therapy.

Genetics

The 4 most common types of SCID are the X-linked form, caused by mutations in CD132 ; autosomal recessive RAG1 and RAG2 deficiencies; and ADA deficiency. Additional forms are listed in Table 152.1 . For X-linked SCID and ADA deficiency, gene therapy exists, but genetic counseling is the most compelling reason for genetic sequencing to identify the gene defect. Several specific gene defects are associated with increased sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy, and their early identification can lead to a better transplant experience.

Sequencing is often done by requesting a SCID gene panel. There are certain laboratory features that predict specific gene defects. When both T cells and B cells are low, often a gene encoding a protein involved in V(D)J recombination is the cause. Similarly, certain cytokine receptor defects are associated with specific lymphocyte phenotypes.

Hypomorphic mutations in genes most often associated with SCID can lead to varied phenotypes. This condition is often referred to as leaky SCID, referring to the mutation being “leaky” for some lymphocyte development. Leaky phenotypes range from the dramatic Omenn syndrome phenotype to later-onset immunodeficiency, granulomas, and autoimmunity.

Bibliography

Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States. JAMA . 2014;312:729–738.

Pai SY, Logan BR, Griffith LM, et al. Transplantation outcomes for severe combined immunodeficiency, 2000–2009. N Engl J Med . 2014;371:434–446.

Combined Immunodeficiency

Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

Combined immunodeficiency (CID ) is distinguished from SCID by the presence of low but not absent T-cell function. CID is a syndrome of diverse genetic causes. Patients with CID have recurrent or chronic pulmonary infections, failure to thrive, oral or cutaneous candidiasis, chronic diarrhea, recurrent skin infections, gram-negative bacterial sepsis, urinary tract infections, and severe varicella in infancy. Although they usually survive longer than infants with SCID, they fail to thrive and often die before adulthood. Neutropenia and eosinophilia are common. Serum immunoglobulins may be normal or elevated for all classes, but selective IgA deficiency, marked elevation of IgE, and elevated IgD levels occur in some cases. Although antibody-forming capacity is impaired in most patients, it is not absent.

Studies of cellular immune function show lymphopenia, deficiencies of T cells, and extremely low but not absent lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens, antigens, and allogeneic cells in vitro. Peripheral lymphoid tissues demonstrate paracortical lymphocyte depletion. The thymus is usually small, with a paucity of thymocytes and usually no Hassall corpuscles.

Cartilage-Hair Hypoplasia

Cartilage-hair hypoplasia (CHH) is an unusual form of short-limbed dwarfism with frequent and severe infections. It occurs with a high frequency among the Amish and Finnish people.

Genetics and Pathogenesis

CHH is an autosomal recessive condition. Numerous mutations that cosegregate with the CHH phenotype have been identified in the untranslated RNase MRP (RMRP ) gene. The RMRP endoribonuclease consists of an RNA molecule bound to several proteins and has at least 2 functions: cleavage of RNA in mitochondrial DNA synthesis and nucleolar cleaving of pre-RNA. Mutations in RMRP cause CHH by disrupting a function of RMRP RNA that affects multiple organ systems. In vitro studies show decreased numbers of T cells and defective T-cell proliferation because of an intrinsic defect related to the G1 phase, resulting in a longer cell cycle for individual cells. NK cells are increased in number and function.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical features include short, pudgy hands; redundant skin; hyperextensible joints of hands and feet but an inability to extend the elbows completely; and fine, sparse, light hair and eyebrows. Infections range from mild to severe. Associated conditions include deficient erythrogenesis, Hirschsprung disease, and an increased risk of malignancies. The bones radiographically show scalloping and sclerotic or cystic changes in the metaphyses and flaring of the costochondral junctions of the ribs. Some patients have been treated with HSCT.

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome is an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by atopic dermatitis, thrombocytopenic purpura with normal-appearing megakaryocytes but small defective platelets, and susceptibility to infection.

Genetics and Pathogenesis

The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) binds CDC42H2 and Rac, members of the Rho family of guanosine triphosphatases. WASP controls the assembly of actin filaments required for cell migration and cell-cell interactions.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often have prolonged bleeding from the circumcision site or bloody diarrhea during infancy. The thrombocytopenia is not initially caused by antiplatelet antibodies. Atopic dermatitis and recurrent infections usually develop during the 1st yr of life. Streptococcus pneumoniae and other bacteria having polysaccharide capsules cause otitis media, pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis. Later, infections with agents such as P. jiroveci and the herpesviruses become more frequent. Infections, bleeding, and EBV-associated malignancies are major causes of death.

Patients with this defect uniformly have an impaired humoral immune response to polysaccharide antigens, as evidenced by absent or greatly diminished isohemagglutinins, and poor or absent antibody responses after immunization with polysaccharide vaccines. The predominant immunoglobulin pattern is a low serum level of IgM, elevated IgA and IgE, and a normal or slightly low IgG concentration. Because of their profound antibody deficiencies, these patients should be given immunoglobulin replacement regardless of their serum levels of the different immunoglobulin isotypes. Percentages of T cells are moderately reduced, and lymphocyte responses to mitogens are variably depressed.

Treatment

Good supportive care includes appropriate nutrition, immunoglobulin replacement, use of killed vaccines, and aggressive management of eczema and associated cutaneous infections. HSCT is the treatment of choice when a high-quality matched donor is available and is usually curative. Gene-corrected autologous HSCT has resulted in sustained benefits in 6 patients.

Ataxia-Telangiectasia

Ataxia-telangiectasia is a complex syndrome with immunologic, neurologic, endocrinologic, hepatic, and cutaneous abnormalities.

Genetics and Pathogenesis

The ataxia-telangiectasia mutation (ATM ) gene encodes a protein critical for responses to DNA damage. Cells from patients, as well as from heterozygous carriers, have increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation, defective DNA repair, and frequent chromosomal abnormalities.

In vitro tests of lymphocyte function have generally shown moderately depressed proliferative responses to T- and B-cell mitogens. Percentages of CD3 and CD4 T cells are moderately reduced, with normal or increased percentages of CD8 and elevated numbers of γ/δ T cells. The thymus is very hypoplastic, exhibits poor organization, and lacks Hassall corpuscles.

Clinical Manifestations

The most prominent clinical features are progressive cerebellar ataxia, oculocutaneous telangiectasias, chronic sinopulmonary disease , a high incidence of malignancy, and variable humoral and cellular immunodeficiency. Ataxia typically becomes evident soon after these children begin to walk and progresses until they are confined to a wheelchair, usually by age 10-12 yr. The telangiectasias begin to develop at 3-6 yr. The most frequent humoral immunologic abnormality is the selective absence of IgA, which occurs in 50–80% of these patients. IgG2 or total IgG levels may be decreased, and specific antibody titers may be decreased or normal. Recurrent sinopulmonary infections occur in approximately 80% of these patients. Although common viral infections have not usually resulted in untoward sequelae, fatal varicella has occurred. The malignancies associated with ataxia-telangiectasia are usually of the lymphoreticular type, but adenocarcinomas also occur. Unaffected carriers of mutations have an increased incidence of malignancy.

Therapy in ataxia-telangiectasia is supportive.

Autosomal Dominant Hyper-IgE Syndrome

This syndrome is associated with early-onset atopy and recurrent skin and lung infections.

Genetics and Pathogenesis

The autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome is caused by heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3). These mutations result in a dominant negative effect. The many clinical features are caused by compromised signaling downstream of the interleukin (IL)-6, type I interferon, IL-22, IL-10 and epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors.

Clinical Manifestations

The characteristic clinical features are staphylococcal abscesses, pneumatoceles, osteopenia, and unusual facial features. There is a history from infancy of recurrent staphylococcal abscesses involving the skin, lungs, joints, viscera, and other sites. Persistent pneumatoceles develop as a result of recurrent pneumonia. Patients often have a history of sinusitis and mastoiditis. Candida albicans is the 2nd most common pathogen. Allergic respiratory symptoms are usually absent. The pruritic dermatitis that occurs is not typical atopic eczema and does not always persist. There can be a prominent forehead, deep-set wide-spaced eyes, a broad nasal bridge, a wide fleshy nasal tip, mild prognathism, facial asymmetry, and hemihypertrophy, although these are most evident in adulthood. In older children, delay in shedding primary teeth, recurrent fractures, and scoliosis occur.

These patients demonstrate an exceptionally high serum IgE concentration ; an elevated serum IgD concentration; usually normal concentrations of IgG, IgA, and IgM; pronounced blood and sputum eosinophilia; and poor antibody and cell-mediated responses to neoantigens. Traditionally, IgE levels >2000 IU/mL confirm the diagnosis. However, IgE levels may fluctuate and even decrease in adults. In neonates and infants with the pruritic pustular dermatosis, IgE levels will be elevated for age and are usually in the 100s. In vitro studies show normal percentages of blood T, B, and NK lymphocytes, except for a decreased percentage of T cells with the memory (CD45RO) phenotype and an absence or deficiency of T-helper type 17 (Th17) cells. Most patients have normal T-lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens but very low or absent responses to antigens or allogeneic cells from family members. Blood, sputum, and histologic sections of lymph nodes, spleen, and lung cysts show striking eosinophilia. Hassall corpuscles and thymic architecture are normal. Therapy is generally directed at prevention of infection using antimicrobials and immunoglobulin replacement.

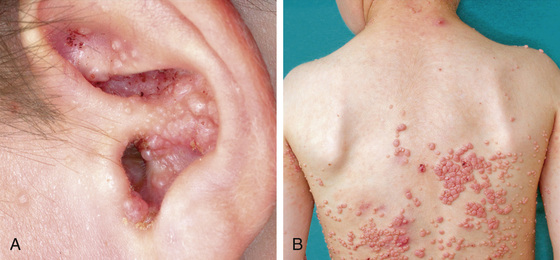

DOCK8 Deficiency

Deficiency of DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) is an autosomal recessive condition that most often presents with impressively severe eczema in infancy and toddlerhood. Cutaneous viral infections and susceptibility to CMV, EBV, and cryptosporidia are common (Fig. 152.3 ). The infectious susceptibility tends to worsen over time, as do the laboratory features of immune dysfunction, most often low T-cell counts and poor proliferative function. Although these patients can survive to adulthood without transplantation, they suffer many complications and their quality of life is often poor. For this reason, most patients are now transplanted early in life to avoid the later complications.

Bibliography

Aiuti A, Biasco L, Scaramuzza S, et al. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science . 2013;341(6148):1233151.

Chang DR, Toh J, de Vos G, Gavrilova T. Early diagnosis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) deficiency. J Pediatr . 2016;179:33–35.

Dobbs K, Dominguez Conde C, Zhang SY, et al. Inherited DOCK2 deficiency in patients with early-onset invasive infections. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(25):2409–2422.

Hacein-Bey Abina S, Gaspar B, Blondeau J, et al. Outcomes following gene therapy in patients with severe Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. JAMA . 2015;313(15):1550–1562.

Hagl B, Heinz V, Schlesinger A, et al. Key findings to expedite the diagnosis of hyper-IgE syndromes in infants and young children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol . 2016;27(2):177–184.

Jouhadi Z, Khadir K, Ailal F, et al. Ten-year follow-up of a DOCK8-deficient child with features of systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatrics . 2014;134:e1458–e1463.

Notarangelo LD. Functional T cell immunodeficiencies (with T cells present). Annu Rev Immunol . 2013;31:195–225.

Notarangelo LD. Multiple intestinal atresia with combined immune deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2014;26:690–696.

Punwani D, Zhang Y, Yu J, et al. Multisystem anomalies in severe combined immunodeficiency with mutant BCL11B . N Engl J Med . 2016;375(22):2165–2176.

Purcell C, Cant A, Irvine AD. DOCK8 primary immunodeficiency syndrome. Lancet . 2015;386:982–983.

Rider NL, Morton DH, Puffenberger E, et al. Immunologic and clinical features of 25 Amish patients with RMRP 70 A→G cartilage hair hypoplasia. Clin Immunol . 2009;131(1):119–128.

Uygungil B, Minka E, Crawford T, Lederman H. Safety of live viral vaccines and retrospective review of immunologic status of 329 patients with ataxia telangiectasia. J Clin Immunol . 2012;32:366.

Yang L, Fliegauf M, Grimbacher B. Hyper-IgE syndromes: reviewing PGM3 deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2014;26:697–703.

Defects of Innate Immunity

Jennifer R. Heimall, Kathleen E. Sullivan

The innate immune system is the earliest responding feature of host defense in vertebrates. Components include the physical barrier function of the skin and mucosal surfaces, complement, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), NK cells, and their associated cytokines. The activation of innate immunity is critically reliant on a group of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that respond to host infections or tissue damage within minutes. These receptors are all germline encoded and are therefore able to be expressed in all cells, where they serve as critical monitors for the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) .

Interferon-γ Receptors 1 and 2, IL-12 Receptor β1 , and IL-12P40 Defects

Among the best-described defects of innate immunity are those associated with susceptibility to nontuberculous mycobacteria. These defects are associated with abnormalities in the interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)–IL-12 signaling axis.

Pathogenesis

Interleukin-12 is a cytokine secreted by macrophages, neutrophils, and DCs in response to infection with mycobacterial and other microbes. IL-12 then binds to receptors on NK cells and T cells to stimulate secretion of IFN-γ. IFN-γ is critical in the activation of phagocyte secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and destruction of the phagocytosed microbe. IFN-γ activates phagocytes via binding of IFN-γ receptor 1 (IFN-γR1) which is found in a homodimerized form associated with Janus-associated kinase-1 (Jak1) that recruits and binds IFN-γ receptor 2 (IFN-γR2) which is associated with Janus-associated kinase-2 (Jak2). Jak1 and Jak2 are then transphosphorylated, which leads to phosphorylation of IFN-γR1 and subsequent docking of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1). Phosphorylated STAT1 then homodimerizes and translocates to the cell nucleus to induce gene transcription. Deficiency of any of these components has a significant impact on phagocyte activation.

Clinical Manifestations

IFN-γR1 deficiency leads to impaired IFN-γ binding and signaling and inability to form mature granulomas and indicates a risk of susceptibility to Mycobacteria species and Salmonella . There are both autosomal recessive (AR) and autosomal dominant (AD) forms of this defect. In the AR form are both partial and complete defects. In the complete AR form, patients present with early onset of disseminated Mycobacteria, and some have been reported to present with nontyphoid Salmonella or Listeria monocytogenes . Treatment should be directed at the presenting infection, with multiple antimicrobial agents used without interruption. HSCT has been used once mycobacterial disease is controlled but requires conditioning to permit the myeloid engraftment necessary to correct the underlying disease. In the partial AR form, IFN-γR1 deficiency remains associated with disseminated Mycobacteria and Salmonella infections but is managed with symptomatic treatment of infections and consideration of IFN-γ therapy to induce higher serum IFN-γ levels. The AD form is also a partial defect in IFN-γ signaling and most often presents with Mycobacteria osteomyelitis, although Salmonella and Histoplasma infections have also been described. Similar to the partial AR defect, these patients are able to be managed with antimicrobial therapy of infections and supplemental IFN-γ injections. Deficiency of IFN-γR2 is an AR defect that also has partial and complete forms. The complete form is a phenocopy to complete IFN-γR1, presenting with early-onset, severe, and disseminated mycobacterial infections. Treatment involves uninterrupted multidrug therapy for the infections and consideration for HSCT. A partial form of IFN-γR2 also presents with mild but potentially disseminated Mycobacteria or Salmonella infections, which can be controlled with antibiotic therapy that can be stopped once the infection is resolved.

Deficiencies of the IL-12 receptor (IL-12R) components have also been described as inherited in an AR fashion, with defects in both the IL-12p40 chain as well as the shared IL-12/IL-23Rβ1 , causing impaired IFN-γ secretion and resultant susceptibility to Mycobacteria and Salmonella. Both forms of IL-12R defects are characterized by relatively mild disease, with some ability to form granulomatous lesions in response to Mycobacteria infections. These defects can usually be managed with antimicrobials and supplemental IFN-γ. Partial defects in STAT1, inherited in an AD fashion, are associated with Mycobacteria susceptibility, whereas complete AR defects in STAT1 are associated with mycobacterial susceptibility as well as defects in responses to IFN-α and IFN-β, leading to fulminant herpesvirus infections. Other defects associated with poor production of IFN-γ leading to increased Mycobacteria susceptibility include AR inherited defects in ISG-15 , which is associated with Mycobacteria- induced brain calcifications, and RORγC deficiency, which leads to a lack of IL-17–producing T cells, in addition to lack of IFN-γ production. RORγC defects are associated with an increased risk of candidiasis in addition to Mycobacteria infections. Defects in Tyk2 , inherited in an AR fashion, generally present with susceptibility to intracellular bacteria, fungi and viruses. AD mutations in interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8 ) are also associated with impaired IL-12 production by the CD1-DCs, leading to increased risk of recurrent mycobacterial infection, which can be treated with antimicrobial therapy.

IL-1R–Associated Kinase 4 Deficiency and Myeloid Differentiation Factor 88

Toll-like receptors (TLRs ) are the best described of the PRRs in humans, and deficiencies almost uniformly cause infection susceptibility.

Pathogenesis

Among those expressed on the cell surface, TLRs 1, 2, and 6 bind lipoproteins and are important in defense to bacteria and fungi, TLR4 binds lipopolysaccharides and has an important role in defense from gram-negative bacteria as well as the fusion protein of RSV. TLR5 binds flagellin, found in many bacterial organisms. The remaining TLRs (3, 7, 8, and 9) are expressed intracellularly, respond to nucleic acids and are initiators for the host response for viral defense. When bound to their PAMP, TLRs activate an intracellular signaling cascade that in most cases utilizes myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) and IL-1R–associated kinase 4 (IRAK4). TLR4 also signals using the Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-B (TRIF). Both MyD88 and TRIF can lead to activation of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway via the IKK complex to induce proinflammatory cytokine production. The IKK complex is composed of IKKα and IKKβ, and IKKγ (NF-κB essential modulator, or NEMO).

Clinical Manifestations

IRAK4 and MYD88 deficiencies have identical features and are associated with deep infections such as pneumonia, meningitis, or sepsis with encapsulated organisms early in life. The main organisms recovered from patients are Staphylococcus aureus , Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This is one of the few types of immunodeficiency where clostridial infections are also seen with increased frequency. Most patients have an improved infection risk after adolescence. Therapy has generally focused on education of parents and clinicians to the life-threatening nature of the infections with encouragement of timely cultures and empirical antibiotic use. These patients may have a blunted febrile response , and clinical features of infection may be subtle.

Among the first-described defects of TLR signaling were X-linked mutations in NEMO , which causes a broad range of clinical manifestations, with most demonstrating a poor inflammatory response. NEMO is typically considered in the category of combined immunodeficiency because of its impact on both innate and adaptive immune responses. Severely affected patients may present with disseminated Mycobacteria infections, severe infections from encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae or other opportunistic infections. In addition to the infectious phenotype, these patients characteristically have conical or peg-shaped teeth, hypohydrosis, and hypotrichosis from anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (EDA). Patients should be treated with immunoglobulin replacement, antibiotic prophylaxis with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and/or penicillin VK. HSCT is a treatment consideration, but myeloid lineage engraftment is needed to fully correct the underlying immunodeficiency.

Natural Killer Cell Deficiency

NK cells are the major lymphocytes of the innate immune system. NK cells recognize virally infected and malignant cells and mediate their elimination. Individuals with absence or functional deficiencies of NK cells are rare, and they typically have susceptibility to the herpesviruses (including varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV), CMV, and EBV) as well as papillomaviruses. A number of gene defects are associated with these isolated abnormalities in NK cells. Autosomal recessive CD16 gene mutations were described in 3 separate families and altered the first immunoglobulin-like domain of this important NK cell activation receptor. Patients with these mutations have NK cells that are functionally impaired and have clinical susceptibility to herpesviruses . AD deficiency of NK cells occurs in individuals with mutations in the GATA2 transcription factor . These patients also have cytopenias and very low numbers of monocytes. They have extreme susceptibility to human papillomavirus (HPV) as well as mycobacteria, the latter presumably from the monocytic defect. They are at risk for alveolar proteinosis, myelodysplasia, and leukemia. AR mutations in the MCM4 gene have been identified in a cohort of patients who had growth failure and susceptibility to herpesviruses. Therapeutically, patients should be maintained on antiviral prophylaxis, and HSCT has been successful in certain cases.

Defects in Innate Responses to Viral Infection

Defects in both the JAK-STAT signaling pathways and the TLR signaling pathways have been implicated in patients with increased susceptibility to severe viral infections. AR defects in STAT1 cause a complete lack of response to INF-γ and IFN-α/β, affecting the function of T and NK cells as well as monocytes, leading to disseminated mycobacterial infections as well as severe herpesvirus infections, including recurrent HSV encephalitis and EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disease. In these patients, lifelong antibiotic therapy to protect from Mycobacteria and antiviral therapy for herpesviruses is recommended, and HSCT should be considered. Defects in STAT2, inherited in an AR fashion, lead to poor T- and NK-cell responses to IFN-α and IFN-β, leading to increased viral susceptibility, in particular development of disseminated vaccine strain measles with central nervous system (CNS) involvement despite development of normal vaccine titers. The interferon response factor 7 (IRF7) is important in induction of IFN-α/β via the both the MyD88-dependent and independent pathways of TLR signaling. AR defects in IRF7 have been associated with severe respiratory distress with influenza A infection in a patient with otherwise normal vaccine responses and T- and B-cell populations.

HSV-1 encephalitis has been associated with a group of defects in TLR signaling that lead to decreased production of IFN-α/β/λ causing impaired immunity to HSV-1 but not other viral infections. The first described was deficiency of UNC93B1, a protein involved in trafficking of the TLRs 7 and 9 and inherited in an AR fashion. Subsequently, defects in TLR3 and TRIF as well as the other TLR pathway signaling molecules tumor necrosis factor (TNF), receptor–associated factor 3 (TRAF3), and tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) were described to lead to decreased production of IFN-α/β/λ and an associated risk of sporadic HSV-1 encephalitis that can be recurrent. The symptoms were controlled with acyclovir prophylaxis.

Defects in Innate Responses to Fungi

Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) can be seen in association with CID, T-cell disorders, and hyper-IgE syndromes, there are also innate defects known to cause CMC (see Chapter 151 ). The most common include AD gain-of-function mutations in STAT1 , where an increased response to IFN-α/β/γ leads to decreased Th17 differentiation. In addition to CMC, these patients also have increased susceptibility to bacterial, fungal, and HSV viral infections; autoimmunity; and enteropathy. Patients with CMC are managed with antifungal, antibacterial, and acyclovir prophylaxis, and HSCT should be considered as a treatment option. Mutations in the IL-17RA and IL-17F have also been described to increase risk of CMC; IL-17RA and IL-17F deficiencies are also associated with S. aureus folliculitis, likely from impaired skin β-defensin production. Treatment includes fluconazole and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim prophylaxis. TRAF3-interacting protein 2 (TRAF3IP2) interacts with IL-17RA on binding of IL-17; AR mutations in TRAF3IP2 have been described in patients with CMC, blepharitis, folliculitis, and macroglossia. CMC is also seen in 25% of patients with IL-12RB1 and IL12p40 defects. Invasive fungal infections, including invasive dermatophyte infections and Candida brain abscesses, have been seen in addition to CMC in patients with AR inherited defects in CARD9. CARD9 leads to NF-κB–induced cytokine production in response to fungal PAMPS that bind to C-type lectin receptors, including Dectin 1, Dectin 2, and MINCLE. Both granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and G-CSF have been successfully used to control refractory brain lesions, and once identified, these patients should be maintained on fluconazole prophylaxis.

Bibliography

Lanternier F, Cypowyj S, Picard C, et al. Primary immunodeficiencies underlying fungal infections. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2013;25(6):736–747.

Picard C, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency 2015. J Clin Immunol . 2015;35(8):696–726.

Prando C, Samarina A, Bustamante J, et al. Inherited IL-12p40 deficiency: genetic, immunologic, and clinical features of 49 patients from 30 kindreds. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2013;92:109–122.

Wu U, Holland SM. Host susceptibility to non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis . 2015;15(8):968–980.

Treatment of Cellular or Combined Immunodeficiency

Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

Good supportive care, including prevention and treatment of infections, is critical while patients await more definitive therapy (Table 152.2 ). Having knowledge of the pathogens causing disease with specific immune defects is also useful.

Table 152.2

Infection in the Host Compromised by B- and T-Cell Immunodeficiency Syndromes

| IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME | OPPORTUNISTIC ORGANISMS ISOLATED MOST FREQUENTLY | APPROACH TO TREATMENT OF INFECTIONS | PREVENTION OF INFECTIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell immunodeficiencies | Encapsulated bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae , and Neisseria meningitidis ), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Campylobacter spp., enteroviruses, rotaviruses, Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium spp., Pneumocystis jiroveci, Ureaplasma urealyticum , and Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

IVIG, 200-800 mg/kg Vigorous attempt to obtain specimens for culture before antimicrobial therapy Incision and drainage if abscess present Antibiotic selection on the basis of sensitivity data |

Maintenance IVIG for patients with quantitative and qualitative defects in IgG metabolism (400-800 mg/kg every 3-5 wk) In chronic recurrent respiratory disease, vigorous attention to postural drainage In selected cases (recurrent or chronic pulmonary or middle ear), prophylactic administration of ampicillin, penicillin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| T-cell immunodeficiencies | Encapsulated bacteria (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus ), facultative intracellular bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis , other Mycobacterium spp., and Listeria monocytogenes ); Escherichia coli; P. aeruginosa; Enterobacter spp.; Klebsiella spp.; Serratia marcescens; Salmonella spp.; Nocardia spp.; viruses (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, rotaviruses, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, measles virus, vaccinia virus, and parainfluenza viruses); protozoa (Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptosporidium spp.); and fungi (Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum , and P. jiroveci ) |

Vigorous attempt to obtain specimens for culture before antimicrobial therapy Incision and drainage if abscess present Antibiotic selection on the basis of sensitivity data Early antiviral treatment for herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, and varicella-zoster viral infections Topical and nonadsorbable antimicrobial agents frequently are useful |

Prophylactic administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for prevention of P. jiroveci pneumonia Oral nonadsorbable antimicrobial agents to lower concentration of gut flora No live virus vaccines or bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine Careful tuberculosis screening |

IVIG, Intravenous immune globulin.

From Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA: Immunologic disorders in infants and children , ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders.

Transplantation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–compatible sibling or rigorously T-cell–depleted haploidentical (half-matched) parental hematopoietic stem cells is the treatment of choice for patients with fatal T-cell or combined T- and B-cell defects. The major risk to the recipient from transplants of bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells is GVHD from donor T cells. Patients with less severe forms of cellular immunodeficiency, including some forms of CID, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, cytokine deficiency, and MHC antigen deficiency, reject even HLA-identical marrow grafts unless chemoablative treatment is given before transplantation. Several patients with these conditions have been treated successfully with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after conditioning.

More than 90% of patients with primary immunodeficiency transplanted with HLA-identical related marrow will survive with immune reconstitution. T-cell–depleted haploidentical-related marrow transplants in patients with primary immunodeficiency have had their greatest success in patients with SCID, who do not require pretransplant conditioning or GVHD prophylaxis. Of patients with SCID, 92% have survived after T-cell–depleted parental marrow is given soon after birth when the infant is healthy, without pretransplant chemotherapy or posttransplant GVHD prophylaxis. Bone marrow transplantation remains the most important and effective therapy for SCID. In ADA-deficient and X-linked SCID, there has been success in correcting the immune defects with ex vivo gene transfer to autologous hematopoietic stem cells. Gene therapy has also been successful in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Initial protocols of gene therapy for X-linked SCID resulted in insertional mutagenesis with the development of leukemic-like clonal T cells or lymphoma in some patients. Modification of the gene therapy protocol has greatly reduced the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

Immune Dysregulation With Autoimmunity or Lymphoproliferation

Jennifer W. Leiding, Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

Primary immunodeficiency diseases characterized by immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, and autoinflammation are monogenic defects of the immune system. These complex multisystem diseases often have a progressive phenotype with organ-specific autoimmunity, specific infectious susceptibility, and lymphoproliferation.

Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome

Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS ), also known as Canale-Smith syndrome, is a disorder of abnormal lymphocyte apoptosis leading to polyclonal populations of T cells (double-negative T cells), which express CD3 and α/β antigen receptors but do not have CD4 or CD8 co-receptors (CD3+ T-cell receptor α/β+ , CD4− CD8− ). These T cells respond poorly to antigens or mitogens and do not produce growth or survival factors (IL-2). The genetic deficit in most patients is a germline or somatic mutation in the FAS gene, which produces a cell surface receptor of the TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF6), which, when stimulated by its ligand, will produce programmed cell death (Table 152.3 ). Persistent survival of these lymphocytes leads to immune dysregulation and autoimmunity. ALPS is also caused by other genes in the Fas pathway (FASLG and CASP10 ). In addition, ALPS-like disorders are associated with other mutations: RAS-associated autoimmune lymphoproliferative disorder (RALD), caspase-8 deficiency, Fas-associated protein with death domain deficiency (FADD), and protein kinase C delta deficiency (PRKCD). These disorders have varying degrees of immunodeficiency, autoimmunity, and lymphoproliferation.

Table 152-3

Revised Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome*

* A definitive diagnosis is based on the presence of both required criteria plus one primary accessory criterion. A probable diagnosis is based on the presence of both required criteria plus one secondary accessory criterion.

From Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, Wedderburn LR, editors: Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Box 46-2.

Clinical Manifestations

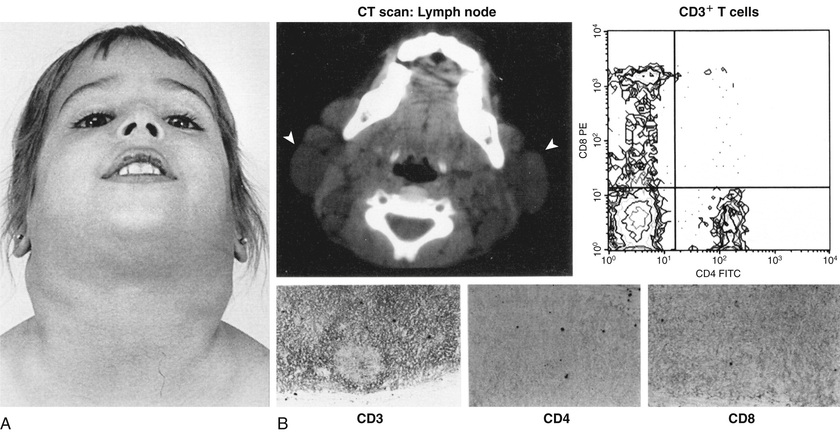

ALPS is characterized by autoimmunity, chronic persistent or recurrent lymphadenopathy , splenomegaly, hepatomegaly (in 50%), and hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG, IgA). Many patients present in the 1st yr of life, and most are symptomatic by age 5 yr. Lymphadenopathy can be striking (Fig. 152.4 ). Splenomegaly may produce hypersplenism. Autoimmunity also produces anemia (Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia) or thrombocytopenia or a mild neutropenia. The lymphoproliferative process (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly) may regress over time, but autoimmunity does not regress and is characterized by frequent exacerbations and recurrences. Other autoimmune features include urticaria, uveitis, glomerulonephritis, hepatitis, vasculitis, panniculitis, arthritis, and CNS involvement (seizures, headaches, encephalopathy).

Malignancies are also more common in patients with ALPS and include Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas and solid-tissue tumors of thyroid, skin, heart, or lung. ALPS is one cause of Evan syndrome (immune thrombocytopenia and immune hemolytic anemia).

Diagnosis

Laboratory abnormalities depend on the lymphoproliferative organ response (hypersplenism) or the degree of autoimmunity (anemia, thrombocytopenia). There may be lymphocytosis or lymphopenia. Table 152.3 lists the criteria for the diagnosis. Flow cytometry helps identify the lymphocyte type (see Fig. 152.4 ). Functional genetic analysis for the TNFRSF6 gene often reveals a heterozygous mutation.

Treatment

Rapamycin (sirolimus) will often control the adenopathy and autoimmune cytopenias. Malignancies can be treated with the usual protocols used in patients unaffected by ALPS. Stem cell transplantation is another possible option in treating the autoimmune manifestations of ALPS.

Immune Dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-Linked Syndrome

This immune dysregulation syndrome is characterized by onset within the 1st few wk or mo of life with watery diarrhea (autoimmune enteropathy), an eczematous rash (erythroderma in neonates), insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism or more often hypothyroidism, severe allergies, and other autoimmune disorders (Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia). Psoriasiform or ichthyosiform rashes and alopecia have also been reported.

Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX ) syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FOXP3 gene, which encodes a forkhead-winged helix transcription factor (scurfin) involved in the function and development of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). The absence of Tregs may predispose to abnormal activation of effector T cells. Dominant gain-of-function mutations in STAT1 and other gene mutations (Table 152.4 ) produce an IPEX-like syndrome, also associated with compromised Tregs.

Table 152.4

Clinical and Laboratory Features of IPEX and IPEX-Like Disorders

| IPEX | CD25 | STAT5B | STAT1 | ITCH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTOIMMUNITY | |||||

| Eczema | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Enteropathy | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Endocrinopathy | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Allergic disease | +++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Cytopenias | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | |

| Lung disease | + | ++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| INFECTIONS | |||||

| Yeast | – | ++ | – | +++ | – |

| Herpes virus | – | +++ (EBV/CMV) | ++ (VZV) | ++ | – |

| Bacterial | +/– | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Associated features | None | None | Growth failure | Vascular anomalies | Dysmorphic growth failure |

| Serum immunoglobulins | Elevated | Elevated or normal | Elevated or normal | Low, normal, or high | Elevated |

| Serum IgE | Elevated | Normal or elevated | Normal or elevated | Normal or mildly elevated | Elevated |

| CD25 expression | Normal | Absent | Normal or low | Normal | Not tested |

| CD4+ CD45RO | Elevated | Elevated | Elevated | Normal or high | Not tested |

| FOXP3 expression | Absent or normal | Normal or low | Normal or low | Normal | Not tested |

| IGF-1, IGFBP-3 | Normal | Normal | Low | Normal | Not tested |

| Prolactin | Normal | Normal | Elevated | Normal | Not tested |

CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, insulin-like growth factor–binding protein 3; IPEX, immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; ITCH, ubiquitin ligase deficiency.

From Verbsky JW, Chatila TA: Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X–linked (IPEX) and IPEX–related disorders: an evolving web of heritable autoimmune diseases, Curr Opin Pediatr 25:709, 2013.

Clinical Manifestations

Watery diarrhea with intestinal villous atrophy leads to failure to thrive in most patients. Cutaneous lesions (usually eczema) and insulin-dependent diabetes begin in infancy. Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are also present. Serious bacterial infections (meningitis, sepsis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis) may be related to neutropenia, malnutrition, or immune dysregulation. Laboratory features reflect the associated autoimmune diseases, dehydration, and malnutrition. In addition, serum IgE levels are elevated, with normal levels of IgM, IgG, and IgA. The diagnosis is made clinically and by mutational analysis of the FOXP3 gene.

Treatment

Inhibition of T-cell activation by cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or sirolimus with corticosteroids is the treatment of choice, along with the specific care of the endocrinopathy and other manifestations of autoimmunity. These agents are typically used as a bridge to transplant. HSCT is the only possibility for curing IPEX.

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA4) Deficiency

Patients with CTLA4 deficiency have lost the ability to maintain immune tolerance, leading to a disease characterized by autoimmunity and multiorgan lymphocytic infiltration of lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. CTLA4, also known as CD152, is a protein receptor that is expressed on activated T cells. It acts as an immune checkpoint, downregulating immune responses, on T-cell activation. CTLA4 deficiency is inherited in a haploinsufficient manner.

Autoimmune cytopenias, lymphoid infiltration of lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs , granulomatous disease, hypogammaglobulinemia, and recurrent respiratory infections are key features. Nonlymphoid organs most often affected with lymphoid infiltration are the brain and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The immune phenotype of CTLA4-deficient patients includes reduced naïve T cells (CD4+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ ), loss of circulating B cells, and reduced Treg expression. Treatment is symptom specific, although use of abatacept, a CTLA4-Ig fusion protein, has alleviated disease-specific symptoms in several patients. When refractory to therapy, HSCT has led to remission of symptoms and cure of disease.

Lipopolysaccharide (Lps)-Responsive Beige-Like Anchor Protein (LRBA) Deficiency

Homozygous mutations in LRBA cause a syndrome of early-onset hypogammaglobulinemia, autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and inflammatory bowel disease.

LRBA is a member of the pleckstrin homology-beige and Chédiak-Higashi–tryptophan–aspartic acid dipeptide (PH-BEACH-WD40) protein family. Much is unknown about the function of LRBA. However, in normal T cells, LRBA co-localizes with CTLA4 within recycling endosomes, suggesting that LRBA may play a specific role in the regulation of recycling endosomes. Homozygous mutations in LRBA abrogate LRBA protein expression.

Immune dysregulation consisting of enteropathy, autoimmune cytopenias, granulomatous-lymphocytic interstitial lung disease , lymphadenopathy , and hepatomegaly or splenomegaly are the most common manifestations. Other, less common symptoms of immune dysregulation include cerebral granulomas, type 1 diabetes mellitus, alopecia, uveitis, myasthenia gravis, and eczema. Growth failure occurs in many patients, complicated especially by enteropathy. Bacterial, fungal, and viral infections have been reported in about 50% of patients. The immune phenotype is variable but can consist of reduced T-cell quantities (CD3+ ), elevated double-negative T cells (CD3+ CD4− CD8− ), normal T-cell proliferation to mitogens and antigens, reduced Treg numbers (CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ ), reduced NK cells (CD56+ ), and reduced B cells (CD19+ ). Immunoglobulin quantities are also variable, with hypogammaglobulinemia occurring most frequently.

The focus of therapy is treatment of the immunodysregulatory features with immunosuppression. Corticosteroids, immunoglobulin replacement, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, rapamycin, budesonide, cyclosporine, azathioprine, rituximab, infliximab, and hydroxychloroquine have all been used with mixed success. Abatacept has been successful in treating the immunodysregulatory features. HSCT has been successfully performed in LRBA-deficient patients as well.

Activated Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K) δ Syndromes

These syndromes are primary immunodeficiencies that cause a spectrum of immunodeficiency, lymphadenopathy, and senescent T cells. PI3K molecules are composed of a p110 catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, or p110δ) and a regulatory subunit (p85α, p55α, p50α, p85β, or p55γ). PI3Ks convert phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3 ), an important second messenger.

Autosomal dominant gain-of-function mutations in PIK3CD , the gene that encodes for the catalytic unit, p110δ, leads to hyperactivated PI3Kδ signaling. AD mutations in PI3KR, the gene that encodes the regulatory subunit (p85α, p55α, and p50α) of PI3Ks are associated with the same phenotype. Defects in this pathway lead to a syndrome of chronic lymphoproliferation and T-cell senescence.

Early-onset respiratory tract infections, noninfectious lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly are the most common features. A large proportion of patients develop early-onset bronchiectasis as a result of recurrent pneumonia. Persistent, severe, or recurrent herpesvirus infections are also common. Lymphadenopathy often starts in childhood and localizes to sites of infection. However, lymphadenopathy may be diffuse and is usually associated with chronic CMV or EBV viremia. Mucosal lymphoid hyperplasia of the respiratory and GI tracts is also frequent. Histologically, lymph nodes show atypical follicular hyperplasia. Autoimmune cytopenias are the most frequent autoimmune manifestation, but others include glomerulopathies, autoantibody-mediated thyroid disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. Early-onset lymphoma, as early as the 2nd yr of life, have been reported as well and are a major cause of mortality. Growth impairment affecting weight and height and developmental delay with mild cognitive impairment also may occur.

The immunophenotype consists of reduced naïve T cell (CD3+ CD4+ ) and B-cell counts (CD19+ ) and normal NK cell counts (CD56+ ). More specifically, reduced numbers of recent thymic emigrants (CD3+ CD4+ CD45RA+ CD31+ ) with increased effector memory cytotoxic T-cell counts (CD3+ CD8+ CCR7− CD45RA+/− ), increased transitional B cells (CD19+ IgM+ CD38+ ), and reduced nonswitched memory B cells (CD19+ IgD+ CD27+ ) and class-switched memory B cells (CD19+ IgD+ CD27+ ) are hallmark. Immunoglobulin levels are variable, but typically there are increased serum quantities of IgM, reduced or normal IgG, and reduced or normal IgA.

Treatment is symptom specific but can include antimicrobial prophylaxis and immunoglobulin replacement. Various immunosuppressive agents (e.g., rituximab, rapamycin) have been used to treat the lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmune cytopenias that are often present. HSCT has also been successfully performed in those refractory to medical therapy.

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) Pathway Defects

The Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT signal transduction pathway is used for signal transduction by type 1 and type 2 cytokine receptors within most hematopoietic cells. Cytokines bind to their cognate receptor, triggering JAK-STAT pathways, ultimately leading to the upregulation of genes involved in the immune response against many pathogens. There are 4 JAK proteins (Jak1, Jak2, Jak3, Tyk2) and 6 STATs (1-6). Mutations in several JAKs and STATs cause immunodeficiency. Table 152.5 includes diseases affecting STAT proteins characterized by immune dysregulation. Chronic immunosuppression is necessary for control of STAT defects. Ruxolitinib, a JAK-STAT inhibitor, has been used with some success. With the advent of JAK-STAT immunomodulating therapies, more treatment options will be available to patients.

Table 152.5

Defects of STAT Proteins Associated With Immunodysregulation

| PROTEIN | LOF/GOF | AUTOIMMUNE OR INFLAMMATORY COMPLICATIONS | OTHER CHARACTERISTICS | IMMUNOPHENOTYPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | GOF | IPEX-like enteropathy, enteropathy, endocrinopathy, dermatitis, cytopenias |

Infections CMC Viral infections NTM Dimorphic mold Respiratory bacterial |

Variable lymphopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, abnormal T-cell function, reduced Th17 expression |

| STAT3 | GOF | Early onset enteropathy, severe growth failure, lymphoproliferation, autoimmune cytopenias, inflammatory lung disease, type 1 diabetes, dermatitis, arthritis |

Respiratory tract infections Herpes viral infections T-cell LGL leukemia NTM |

Increased DNT (CD3+ CD4− CD8− ) Hypogammaglobulinemia T-cell lymphopenia B-cell lymphopenia |

| STAT5B | LOF | Severe growth hormone resistant growth failure, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, atopic dermatitis |

Respiratory tract infections Viral infections |

Lymphopenia Reduced Treg cells Reduced γδ T cells Reduced NK cells |

STAT, Signal transducer and activator of transcription; GOF, gain of function; LOF, loss of function; IPEX, immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked; CMC, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; NTM, nontuberculous mycobacteria; DNT, double-negative T cell.

Nuclear Factor-κB Pathway Defects

The NF-κB pathways consists of canonical (NF-κB1) and noncanonical (NF-κB2) pathways. On cellular activation, both pathways lead to activation and translocation of NF-κB proteins into the nucleus, where they initiate downstream inflammatory responses. Defects in many proteins in both pathways have been described. Table 152.6 describes immune defects of the NF-κB pathways that cause symptoms of immune dysregulation or autoimmunity. Treatment of NF-κB defects includes prevention of infections and replacement of immunoglobulin and has included HSCT.

Table 152.6

Defects of Nuclear Factor-κB Pathways Associated With Immune Dysregulation

| PROTEIN | INHERITANCE | AUTOIMMUNE OR INFLAMMATORY COMPLICATIONS | OTHER MANIFESTATIONS | IMMUNOLOGIC PHENOTYPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKBKG (NEMO) | XL | Colitis |

Ectodermal dysplasia Osteopetrosis Lymphedema Bacterial infections Opportunistic infections DNA viral infections |

Hypogammaglobulinemia Hyper IgM Hyper IgA Hyper IgD Poor antibody responses Decreased NK cell function Decreased TLR responses |

| NF-κB1 | AD |

Pyoderma gangrenosum Lymphoproliferation Cytopenia Hypothyroidism Alopecia areata Enteritis LIP NRH |

Atrophic gastritis Squamous cell carcinoma Respiratory tract infections Superficial skin infections Lung adenocarcinoma Respiratory insufficiency Aortic stenosis Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Hypogammaglobulinemia IgA deficiency |

| NF-κB2 | AD |

Alopecia totalis Trachyonychia Vitiligo Autoantibodies: thyroid peroxidase, glutamate decarboxylase, thyroglobulin Central adrenal insufficiency |

Viral respiratory infections Pneumonias Sinusitis Otitis media Recurrent herpes Asthma Type 1 Chiari malformation Interstitial lung disease |

Early-onset hypogammaglobulinemia Low vaccine responses Variable B-cell counts Low switched memory B cells (CD19+ CD27+ IgD− ) Low marginal zone B cells (CD19+ CD27+ IgD+ ) |

XL, X-linked; AD, autosomal dominant; LIP, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis; NRH, nonregenerative hyperplasia.

Tetratricopeptide Repeat Domain 7A (TTC7A) Deficiency

Combined immunodeficiency with T-cell and B-cell defects had long accompanied hereditary multiple intestinal atresia . Mutations in TTC7A are causative of the combined intestinal and immunologic defects. TTC7A is involved in cell cycle control, cytoskeletal organization, cell shape and polarity, and cell adhesion. Deficiency of TTC7A is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Multiple intestinal atresia with disruption of intestinal architecture is a universal feature. Often, early-onset severe enterocolitis occurs concurrently. Immunodeficiency with severe T-cell lymphopenia has been described; B- and NK-cell defects are variable. T-cell proliferative responses are also abnormal. Severe hypogammaglobulinemia is common. Treatment includes removal of atretic areas of the intestine and antimicrobial prophylaxis in immunodeficient patients. Bowel transplant has also been performed with some success.

Deficiency of Adenosine Deaminase 2 (DADA2)

Deficiency in ADA2 is a cause of early vasculopathy, stroke , and immunodeficiency. DADA2 is secondary to autosomal recessive mutations in cat-eye syndrome chromosome region 1 (CECR1 ), mapped to chromosome 22q11.1. ADA2 is important in purine metabolism converting adenosine to inosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine to 2′-deoxyinosine. The pathogenesis is not exactly known, but ADA2 is mostly secreted by myeloid cells, and deficiency leads to upregulation of proinflammatory genes and increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. DADA2 is characterized by chronic or recurrent inflammation with elevated acute-phase reactants and fever. Skin manifestations include livedo reticularis, maculopapular rash, nodules, purpura, erythema nodosum, Raynaud phenomenon, ulcerative lesions, and digital necrosis. CNS involvement is variable but can include transient ischemic attacks and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Peripheral neuropathy is also common. GI manifestations include hepatosplenomegaly, gastritis, bowel perforation, and portal hypertension. Nephrogenic hypertension is common and can be associated with glomerulosclerosis or amyloidosis. Immunodeficiency consists of hypogammaglobulinemia and variable decreases in IgM.

Treatment with chronic long-term corticosteroids and anti-TNF-α agents have shown modest control of disease manifestations. HSCT has been successful in 2 patients as well.

Bibliography

Barzaghi F, Passerini L, Bacchetta R. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome: a paradigm of immunodeficiency with autoimmunity. Front Immunol . 2012;3:1–25.

Chandesris MO, Melki I, Natividad A, et al. Autosomal dominant STAT3 deficiency and hyper-IgE syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2012;91:e1–e19.

Coulter TI, Chandra A, Bacon CM, et al. Clinical spectrum and features of activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta syndrome: a large patient cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2017;139(2):597–606.e4.

Felgentreff K, Perez-Becker R, Speckmann C, et al. clinical and immunological manifestations of patients with atypical severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol . 2011;141:73–82.

Gamez-Diaz L, August D, Stepensky P, et al. The extended phenotype of LPS-responsive beige-like anchor protein (LRBA) deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2016;137(1):223–230.

Haverkamp MH, van de Vosse E, van Dissel JT. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in children with inborn errors of the immune system. J Infect . 2014;68:S134–S150.

Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W, et al. Autoimmune disease: patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science . 2015;349(6246):436–440.

Nieves DS, Phipps RP, Pollock SJ, et al. Dermatologic and immunologic findings in the immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. Arch Dermatol . 2004;140:466–472.

Oliveria JB. The expanding spectrum of the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2013;25:722–729.