Primary Defects of Cellular Immunity

Kathleen E. Sullivan, Rebecca H. Buckley

Defects in cellular immunity, historically referred to T-cell defects, comprise a large number of distinct immune deficiencies. The manifestations usually include prolonged viral infections, opportunistic fungal or mycobacterial infections, and a predisposition to autoimmunity. To facilitate conceptualization of this large and complex category, this chapter describes immunodeficiencies where the defect primarily affects T cells and those where the defect alters function of many cell types. Chapter 152.1 describes severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). These disorders are further approached clinically by considering whether or not nonhematologic features are present.

Chromosome 22Q11.2 Deletion Syndrome

Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is the most common of the T-cell disorders, occurring in about 1 in 3,000 births in the United States. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion disrupts development of the 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches during early embryogenesis, leading to hypoplasia or aplasia of the thymus and parathyroid glands. Other structures forming at the same age are also frequently affected, resulting in anomalies of the great vessels (right-sided aortic arch), esophageal atresia, bifid uvula, congenital heart disease (conotruncal, atrial, and ventricular septal defects), a short philtrum of the upper lip, hypertelorism, an antimongoloid slant to the eyes, mandibular hypoplasia, and posteriorly rotated ears (see Chapters 98 and 128 ). The diagnosis is often first suggested by hypocalcemic seizures during the neonatal period.

Genetics and Pathogenesis

Chromosome 22q11.2 deletions occur with high frequency because complex repeat sequences that flank the region represent a challenge for DNA polymerase. This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and occurs with comparable frequency in all populations. Within the deleted region, haplosufficiency for the TBX1 transcription factor appears to underlie the majority of the phenotype. The phenotype is highly variable; a subset of patients has a phenotype that has also been called DiGeorge syndrome , velocardiofacial syndrome , or conotruncal anomaly face syndrome .

Variable hypoplasia of the thymus occurs in 75% of the patients with the deletion, which is more frequent than total aplasia; aplasia is present in <1% of patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Slightly less than half of patients with complete thymic aplasia are hemizygous at chromosome 22q11.2. Approximately 15% are born to diabetic mothers. Another 15% of infants have no identified risk factors. Approximately one third of infants with complete DiGeorge syndrome have CHARGE association (c oloboma, h eart defect, choanal a tresia, growth or developmental r etardation, g enital hypoplasia, and e ar anomalies including deafness). Mutations in the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 7 (CHD7) gene on chromosome 8q12.2 are found in approximately 60–65% of individuals with CHARGE syndrome; a minority have mutations in SEMA3E .

Absolute lymphocyte counts are usually only moderately low for age. The CD3 T-cell counts are variably decreased in number, corresponding to the degree of thymic hypoplasia. Lymphocyte responses to mitogen stimulation are absent, reduced, or normal, depending on the degree of thymic deficiency. Immunoglobulin levels are often normal, but there is an increased frequency of IgA deficiency, low IgM levels, and some patients develop progressive hypogammaglobulinemia.

Clinical Manifestations

Children with partial thymic hypoplasia may have little trouble with infections and grow normally. Patients with thymic aplasia resemble patients with SCID in their susceptibility to infections with low-grade or opportunistic pathogens, including fungi, viruses, and Pneumocystis jiroveci , and to graft-versus-host disease from nonirradiated blood transfusions. Patients with complete DiGeorge syndrome can develop an atypical phenotype in which oligoclonal T-cell populations appear in the blood associated with rash and lymphadenopathy. These atypical patients appear phenotypically similar to patients with Omenn syndrome or maternal T-lymphocyte engraftment.

It is critical to ascertain in a timely manner whether an infant has thymic aplasia, because this disease is fatal without treatment. A T-cell count should be obtained on all infants born with primary hypoparathyroidism, CHARGE syndrome, and conotruncal cardiac anomalies with syndromic features. Some infants are being identified by newborn screening for SCID and when 22q11.2 deletion is suspected, a calcium level should be obtained at the time of T-cell evaluation. The 3 manifestations with the highest morbidity in early infancy are profound immunodeficiency, severe cardiac anomaly, and seizures from hypocalcemia. Thus an early focus on these concerns is warranted even before the diagnosis is confirmed. Affected patients may develop autoimmune cytopenias, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, atopy, and malignancies (lymphomas).

Treatment

The immunodeficiency in thymic aplasia is correctable by cultured unrelated thymic tissue transplants . Some infants with thymic aplasia have been given nonirradiated unfractionated bone marrow or peripheral blood transplants from a human leukocyte antigen–identical sibling, with subsequent improved immune function because of adoptively transferred T cells. Infants and children with low T-cell counts but not low enough to consider transplantation should be monitored for evolution of immunoglobulin defects. Infections in these patients are multifactorial. Their anatomy may not favor drainage of secretions; they have a higher rate of atopy, which may complicate infections; and their host defense may allow persistence of infections. Interventions range from hand hygiene, probiotics, prophylactic antibiotics, and risk management to immunoglobulin replacement for those who have demonstrated defective humoral immunity.

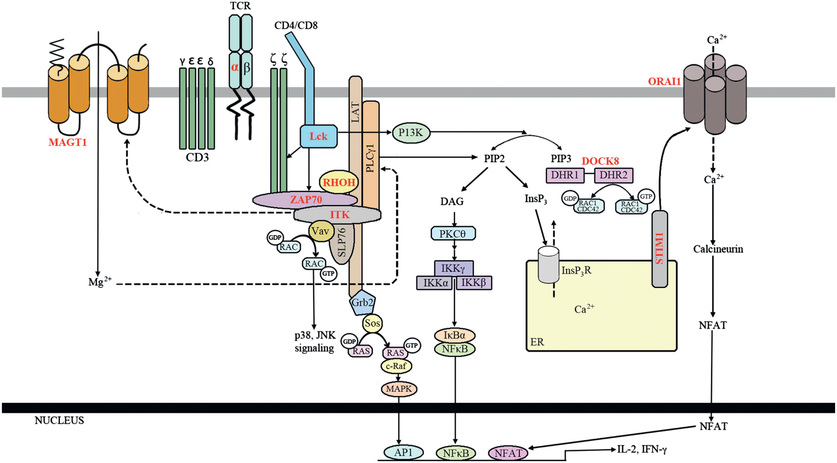

T-Cell Activation Defects

T-cell activation defects are characterized by the presence of normal or elevated numbers of blood T cells that appear phenotypically normal but fail to proliferate or produce cytokines normally in response to stimulation with mitogens, antigens, or other signals delivered to the TCR, owing to defective signal transduction from the TCR to intracellular metabolic pathways (Fig. 151.1 ). These patients have problems similar to those of other T-cell–deficient individuals, and some with severe T-cell activation defects may clinically resemble SCID patients (Table 151.1 ). In some cases, susceptibility to a single pathogen or a limited number of pathogens dominates the clinical phenotype. Susceptibility to Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and papillomavirus is common in this set of T-cell defects. Most individuals with significant T-cell activation defects will require a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Although each infection may be manageable early in life, the long-term prognosis is not favorable in many of these conditions.

Table 151.1

AIRE, Autoimmune regulator; APECED, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis–ectodermal dysplasia; Ig, immunoglobulin; ITK, IL-2–inducible tyrosine kinase deficiency; MST1, macrophage-stimulating factor 1; NKT, natural killer T; RhoH, Ras homology family member H; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; STK4, serine threonine kinase 4; TCR, T-cell receptor; TRAC, T-cell receptor α chain constant region; ZAP-70, zeta-associated protein 70.

Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC ) is a syndrome characterized by impaired immune responsiveness to Candida. Some of the known gene defects with CMC have autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1 (APS1 , or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis–ectodermal dystrophy [APECED ]). One of the other genetic types of CMC is associated with autoimmunity and predisposition to other infections (STAT1 gain-of-function mutations). However, most of the specific genetic types of CMC have isolated susceptibility to Candida . These types of CMC relate to defects in the Th17 cell pathway. Autosomal recessive deficiency in the interleukin-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) chain, and an autosomal dominant deficiency of the cytokine IL-17F are both associated with predisposition to Candida . Other immunodeficiencies in which Candida occurs in the context of other infections also affect the Th17 cells. Another CMC genetic type, caused by mutations in CARD9 , has a strong predisposition to Candida but also to other fungi.

Although the underlying gene defects are varied, the clinical presentation of CMC is usually similar. Symptoms can begin in the 1st mo of life or as late as the 2nd decade. The disorder is characterized by chronic and severe Candida skin and mucous membrane infections. Patients rarely develop systemic Candida disease, except as noted below. Topical antifungal therapy can provide limited improvement early in the course of the disease, but systemic courses of azoles are usually necessary; antifungal resistance often develops later in life. The infection usually responds temporarily to treatment, but it is not eradicated and recurs. Patients with CARD9 gene mutations have a more severe fungal susceptibility than typical CMC patients. Two described patients with CARD9 mutations had fungal sepsis in addition to CMC; deep tissue dermatophyte infections were also present.

Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis–Ectodermal Dysplasia

Patients with this syndrome present with CMC and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, usually developing hypoparathyroidism and Addison disease before adulthood. Additional features include male and female hypogonadism, chronic active hepatitis, alopecia, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, enamel hypoplasia, type 1 diabetes, asplenia, malabsorption, interstitial nephritis, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, and Sjögren syndrome. APECED, or APS1, is caused by a mutation in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene (see Table 151.1 ). The gene product, AIRE, is expressed at high levels in purified human thymic medullary stromal cells and is thought to regulate the cell surface expression of tissue-specific proteins such as insulin and thyroglobulin. Expression of these self proteins allows for the negative selection of autoreactive T cells during their development. Failure of negative selection results in organ-specific autoimmune destruction.