Herpes Simplex Virus

Lawrence R. Stanberry

The 2 closely related herpes simplex viruses (HSVs), HSV type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV type 2 (HSV-2), cause a variety of illnesses, depending on the anatomic site where the infection is initiated, the immune state of the host, and whether the symptoms reflect primary or recurrent infection. Common infections involve the skin, eye, oral cavity, and genital tract. Infections tend to be mild and self-limiting, except in the immunocompromised patient and newborn infant, in whom they may be severe and life-threatening.

Primary infection occurs in individuals who have not been infected previously with either HSV-1 or HSV-2. Because these individuals are HSV seronegative and have no preexisting immunity to HSV, primary infections can be severe. Nonprimary first infection occurs in individuals previously infected with 1 type of HSV (e.g., HSV-1) who have become infected for the first time with the other type of HSV (in this case, HSV-2). Because immunity to 1 HSV type provides some cross-protection against disease caused by the other HSV type, nonprimary first infections tend to be less severe than true primary infections. During primary and nonprimary initial infections, HSV establishes latent infection in regional sensory ganglion neurons. Virus is maintained in this latent state for the life of the host but periodically can reactivate and cause recurrent infection. Symptomatic recurrent infections tend to be less severe and of shorter duration than 1st infections. Asymptomatic recurrent infections are extremely common and cause no physical distress, although patients with these infections are contagious and can transmit the virus to susceptible individuals. Reinfection with a new strain of either HSV-1 or HSV-2 at a previously infected anatomic site (e.g., the genital tract) can occur but is relatively uncommon, suggesting that host immunity, perhaps site-specific local immunity, resulting from the initial infection affords protection against exogenous reinfection.

Etiology

HSVs contain a double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 152 kb that encodes at least 84 proteins. The DNA is contained within an icosadeltahedral capsid, which is surrounded by an outer envelope composed of a lipid bilayer containing at least 12 viral glycoproteins. These glycoproteins are the major targets for humoral immunity, whereas other nonstructural proteins are important targets for cellular immunity. Two encoded proteins, viral DNA polymerase and thymidine kinase, are targets for antiviral drugs. HSV-1 and HSV-2 have a similar genetic composition with extensive DNA and protein homology. One important difference in the 2 viruses is their glycoprotein G genes, which have been exploited to develop a new generation of commercially available, accurate, type-specific serologic tests that can be used to discriminate whether a patient has been infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2 or both.

Epidemiology

HSV infections are ubiquitous, and there are no seasonal variations in risk for infection. The only natural host is humans, and the mode of transmission is direct contact between mucocutaneous surfaces. There are no documented incidental transmissions from inanimate objects such as toilet seats.

All infected individuals harbor latent infection and experience recurrent infections, which may be symptomatic or may go unrecognized and thus are periodically contagious. This information helps explain the widespread prevalence of HSV.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are equally capable of causing initial infection at any anatomic site but differ in their capacity to cause recurrent infections. HSV-1 has a greater propensity to cause recurrent oral infections, whereas HSV-2 has a greater proclivity to cause recurrent genital infections. For this reason, HSV-1 infection typically results from contact with contaminated oral secretions, whereas HSV-2 infection most commonly results from anogenital contact.

HSV seroprevalence rates are highest in developing countries and among lower socioeconomic groups, although high rates of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections are found in developed nations and among persons of the highest socioeconomic strata. Incident HSV-1 infections are more common during childhood and adolescence but are also found throughout later life. Data from the U.S. population–based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted between 1999 and 2004 showed a consistent increase of HSV-1 prevalence with age, which rose from 39% in adolescents 14-19 yr of age to 65% among those 40-49 yr of age. HSV-1 seroprevalence was not influenced by gender, but rates were highest in Mexican-Americans (80.8%), intermediate in non-Hispanic blacks (68.3%), and lowest in non-Hispanic whites (50.1%). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study conducted between 2007 and 2010 found an overall HSV-2 prevalence of 15.5%, with a steady increase with age from 1.5% in the 14-19 yr old age group to 25.6% in the 40-49 yr old group. The rate was higher among females than males (20.3% and 10.6%, respectively) and varied by race and ethnic group, with an overall seroprevalence of 41.8% in non-Hispanic blacks, 11.3% in Mexican-Americans, and 11.3% in whites. Modifiable factors that predict HSV-2 seropositivity include less education, poverty, cocaine use, and a greater lifetime number of sexual partners. Studies show that only approximately 10–20% of HSV-2–seropositive subjects report a history of genital herpes, emphasizing the asymptomatic nature of most HSV infections.

A 3 yr longitudinal study of Midwestern adolescent females 12-15 yr of age found that 44% were seropositive for HSV-1 and 7% for HSV-2 at enrollment. At the end of the study, 49% were seropositive for HSV-1 and 14% for HSV-2. The attack rates, based on the number of cases per 100 person-years, were 3.2 for HSV-1 infection among all females and 4.4 for HSV-2 infection among girls who reported being sexually experienced. Findings of this study indicate that sexually active young women have a high attack rate for genital herpes and suggest that genital herpes should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any young woman who reports recurrent genitourinary complaints. In this study, participants with preexisting HSV-1 antibodies had a significantly lower attack rate for HSV-2 infection, and those who became infected were less likely to have symptomatic disease than females who were HSV seronegative when they entered the study. Prior HSV-1 infection appears to afford adolescent females some protection against becoming infected with HSV-2; in adolescent females infected with HSV-2, the preexisting HSV-1 immunity appears to protect against development of symptomatic genital herpes.

Neonatal herpes is an uncommon but potentially fatal infection of the fetus or more likely the newborn. It is not a reportable disease in most states, and therefore there are no solid epidemiologic data regarding its frequency in the general population. In King County, Washington, the estimated incidence of neonatal herpes was 2.6 cases per 100,000 live births in the late 1960s, 11.9 cases per 100,000 live births from 1978 to 1981, and 31 cases per 100,000 live births from 1982 to 1999. This increase in neonatal herpes cases parallels the increase in cases of genital herpes. The estimated rate of neonatal herpes is 1 per 3,000-5,000 live births, which is higher than reported for the reportable perinatally acquired sexually transmitted infections such as congenital syphilis and gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. More than 90% of the cases are the result of maternal-child transmission. The risk for transmission is greatest during a primary or nonprimary first infection (30–50%) and much lower when the exposure is during a recurrent infection (<2%). HSV viral suppression therapy in mothers does not consistently eliminate the possibility of neonatal infection. Infants born to mothers dually infected with HIV and HSV-2 are also at higher risk for acquiring HIV than infants born to HIV-positive mothers who are not HSV-2 infected. It is estimated that approximately 25% of pregnant women are HSV-2 infected and that approximately 2% of pregnant women acquire HSV-2 infection during pregnancy.

HSV is a leading cause of sporadic, fatal encephalitis in children and adults. In the United States the annual hospitalization rate for HSV encephalitis has been calculated to be 10.3 ± 2.2 cases/million in neonates, 2.4 ± 0.3 cases/million in children, and 6.4 ± 0.4 cases/million in adults.

Pathogenesis

In the immunocompetent host the pathogenesis of HSV infection involves viral replication in skin and mucous membranes followed by replication and spread in neural tissue. Viral infection typically begins at a cutaneous portal of entry such as the oral cavity, genital mucosa, ocular conjunctiva, or breaks in keratinized epithelia. Virus replicates locally, resulting in the death of the cell, and sometimes produces clinically apparent inflammatory responses that facilitate the development of characteristic herpetic vesicles and ulcers. Virus also enters nerve endings and spreads beyond the portal of entry to sensory ganglia by intraneuronal transport. Virus replicates in some sensory neurons, and the progeny virions are sent via intraneuronal transport mechanisms back to the periphery, where they are released from nerve endings and replicate further in skin or mucosal surfaces. It is virus moving through this neural arc that is primarily responsible for the development of characteristic herpetic lesions, although most HSV infections do not reach a threshold necessary to cause clinically recognizable disease. Although many sensory neurons become productively infected during the initial infection, some infected neurons do not initially support viral replication. It is in these neurons that the virus establishes a latent infection, a condition in which the viral genome persists within the neuronal nucleus in a largely metabolically inactive state. Intermittently throughout the life of the host, undefined changes can occur in latently infected neurons that trigger the virus to begin to replicate. This replication occurs despite the host's having established a variety of humoral and cellular immune responses that successfully controlled the initial infection. With reactivation of the latent neuron, progeny virions are produced and transported within nerve fibers back to cutaneous sites somewhere in the vicinity of the initial infection, where further replication occurs and causes recurrent infections. Recurrent infections may be symptomatic (with typical or atypical herpetic lesions) or asymptomatic. In either case, virus is shed at the site where cutaneous replication occurs and can be transmitted to susceptible individuals who come in contact with the site or with contaminated secretions. Latency and reactivation are the mechanisms by which the virus is successfully maintained in the human population.

Viremia, or hematogenous spread of the virus, does not appear to play an important role in HSV infections in the immunocompetent host but can occur in neonates, individuals with eczema, and severely malnourished children. It is also seen in patients with depressed or defective cell-mediated immunity, as occurs with HIV infection or some immunosuppressive therapies. Viremia can result in dissemination of the virus to visceral organs, including the liver and adrenals. Hematogenous dissemination of virus to the central nervous system appears to only occur in neonates.

The pathogenesis of HSV infection in newborns is complicated by their relative immunologic immaturity. The source of virus in neonatal infections is typically but not exclusively the mother. Transmission generally occurs during delivery, although it is well documented to occur even with cesarean delivery with intact fetal membranes. The most common portals of entry are the conjunctiva, mucosal epithelium of the nose and mouth, and breaks or abrasions in the skin that occur with scalp electrode use or forceps delivery. With prompt antiviral therapy, virus replication may be restricted to the site of inoculation (the skin, eye, or mouth). However, virus may also extend from the nose to the respiratory tract to cause pneumonia, move via intraneuronal transport to the central nervous system to cause encephalitis, or spread by hematogenous dissemination to visceral organs and the brain. Factors that may influence neonatal HSV infection include the virus type, portal of entry, inoculum of virus to which the infant is exposed, gestational age of the infant, and presence of maternally derived antibodies specific to the virus causing infection. Latent infection is established during neonatal infection, and survivors may experience recurrent cutaneous and neural infections. Persistent central nervous system infection may impact the neurodevelopment of the infant.

Clinical Manifestations

The hallmarks of common HSV infections are skin vesicles and shallow ulcers. Classic infections manifest as small, 2-4 mm vesicles that may be surrounded by an erythematous base. These may persist for a few days before evolving into shallow, minimally erythematous ulcers. The vesicular phase tends to persist longer when keratinized epithelia is involved and is generally brief and sometimes just fleeting when moist mucous membranes are the site of infection. Because HSV infections are common and their natural history is influenced by many factors, including portal of entry, immune status of the host, and whether it is an initial or recurrent infection, the typical manifestations are seldom classic. Most infections are asymptomatic or unrecognized, and nonclassic presentations, such as small skin fissures and small erythematous nonvesicular lesions, are common.

Acute Oropharyngeal Infections

Herpes gingivostomatitis most often affects children 6 mo to 5 yr of age but is seen across the age spectrum. It is an extremely painful condition with sudden onset, pain in the mouth, drooling, refusal to eat or drink, and fever of up to 40.0-40.6°C (104-105.1°F). The gums become markedly swollen, and vesicles may develop throughout the oral cavity, including the gums, lips, tongue, palate, tonsils, pharynx, and perioral skin (Fig. 279.1 ). The vesicles may be more extensively distributed than typically seen with enteroviral herpangina. During the initial phase of the illness there may be tonsillar exudates suggestive of bacterial pharyngitis. The vesicles are generally present only a few days before progressing to form shallow indurated ulcers that may be covered with a yellow-gray membrane. Tender submandibular, submaxillary, and cervical lymphadenopathy is common. The breath may be foul as a result of overgrowth of anaerobic oral bacteria. Untreated, the illness resolves in 7-14 days, although the lymphadenopathy may persist for several weeks.

In older children, adolescents, and college students, the initial HSV oral infection may manifest as pharyngitis and tonsillitis rather than gingivostomatitis. The vesicular phase is often over by the time the patient presents to a healthcare provider, and signs and symptoms may be indistinguishable from those of streptococcal pharyngitis, consisting of fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and white plaques on the tonsils. The course of illness is typically longer than for untreated streptococcal pharyngitis.

Herpes Labialis

Fever blisters (cold sores) are the most common manifestation of recurrent HSV-1 infections. The most common site of herpes labialis is the vermilion border of the lip, although lesions sometimes occur on the nose, chin, cheek, or oral mucosa. Older patients report experiencing burning, tingling, itching, or pain 3-6 hr (rarely as long as 24-48 hr) before the development of the herpes lesion. The lesion generally begins as a small grouping of erythematous papules that over a few hours progress to create a small, thin-walled vesicle. The vesicles may form shallow ulcers or become pustular. The short-lived ulcer dries and develops a crusted scab. Complete healing without scarring occurs with reepithelialization of the ulcerated skin, usually within 6-10 days. Some patients experience local lymphadenopathy but no constitutional symptoms.

Cutaneous Infections

In the healthy child or adolescent, cutaneous HSV infections are generally the result of skin trauma with macro or micro abrasions and exposure to infectious secretions. This situation most often occurs in play or contact sports such as wrestling (herpes gladiatorum ) and rugby (scrum pox ). An initial cutaneous infection establishes a latent infection that can subsequently result in recurrent infections at or near the site of the initial infection. Pain, burning, itching, or tingling often precedes the herpetic eruption by a few hours to a few days. Like herpes labialis, lesions begin as grouped, erythematous papules that progress to vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusts and then heal without scarring in 6-10 days. Although herpes labialis typically results in a single lesion, a cutaneous HSV infection results in multiple discrete lesions and involves a larger surface area. Regional lymphadenopathy may occur but systemic symptoms are uncommon. Recurrences are sometimes associated with local edema and lymphangitis or local neuralgia.

Herpes whitlow is a term generally applied to HSV infection of fingers or toes, although strictly speaking it refers to HSV infection of the paronychia. Among children, this condition is most commonly seen in infants and toddlers who suck the thumb or fingers and who are experiencing either a symptomatic or a subclinical oral HSV-1 infection (Fig. 279.2 ). An HSV-2 herpes whitlow occasionally develops in an adolescent as a result of exposure to infectious genital secretions. The onset of the infection is heralded by itching, pain, and erythema 2-7 days after exposure. The cuticle becomes erythematous and tender and may appear to contain pus, although if it is incised, little fluid is present. Incising the lesion is discouraged, as this maneuver typically prolongs recovery and increases the risk for secondary bacterial infection. Lesions and associated pain typically persist for about 10 days, followed by rapid improvement and complete recovery in 18-20 days. Regional lymphadenopathy is common, and lymphangitis and neuralgia may occur. Unlike other recurrent herpes infections, recurrent herpetic whitlows are often as painful as the primary infection but are generally shorter in duration.

Cutaneous HSV infections can be severe or life-threatening in patients with disorders of the skin such as eczema (eczema herpeticum), pemphigus, burns, and Darier disease and following laser skin resurfacing. The lesions are frequently ulcerative and nonspecific in appearance, although typical vesicles may be seen in adjacent normal skin (Fig. 279.3 ). If untreated, these lesions can progress to disseminated infection and death. Recurrent infections are common but generally less severe than the initial infection.

Genital Herpes

Genital HSV infection is common in sexually experienced adolescents and young adults, but up to 90% of infected individuals are unaware they are infected. Infection may result from genital-genital transmission (usually HSV-2) or oral-genital transmission (usually HSV-1). Symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals periodically shed virus from anogenital sites and hence can transmit the infection to sexual partners or, in the case of pregnant women, to their newborns. Classic primary genital herpes may be preceded by a short period of local burning and tenderness before vesicles develop on genital mucosal surfaces or keratinized skin and sometimes around the anus or on the buttocks and thighs. Vesicles on mucosal surfaces are short lived and rupture to produce shallow, tender ulcers covered with a yellowish gray exudate and surrounded by an erythematous border. Vesicles on keratinized epithelium persist for a few days before progressing to the pustular stage and then crusting.

Patients may experience urethritis and dysuria severe enough to cause urinary retention and bilateral, tender inguinal and pelvic lymphadenopathy. Women may experience a watery vaginal discharge, and men may have a clear mucoid urethral discharge. Significant local pain and systemic symptoms such as fever, headache, and myalgia are common. Aseptic meningitis develops in an estimated 15% of cases. The course of classic primary genital herpes from onset to complete healing is 2-3 wk.

Most patients with symptomatic primary genital herpes experience at least 1 recurrent infection in the following year. Recurrent genital herpes is usually less severe and of shorter duration than the primary infection. Some patients experience a sensory prodrome with pain, burning, and tingling at the site where vesicles subsequently develop. Asymptomatic recurrent anogenital HSV infections are common, and all HSV-2–seropositive individuals appear to periodically shed virus from anogenital sites. Most sexual transmissions and maternal-neonatal transmissions of virus result from asymptomatic shedding episodes.

Genital infections caused by HSV-1 and HSV-2 are indistinguishable, but HSV-1 causes significantly fewer subsequent episodes of recurrent infection; hence, knowing which virus is causing the infection has important prognostic value. Genital HSV infection increases the risk for acquiring HIV infection.

Rarely, genital HSV infections are identified in young children and preadolescents. Although genital disease in children should raise concerns about possible sexual abuse, there are documented cases of autoinoculation, in which a child has inadvertently transmitted virus from contaminated oral secretions to his or her own genitalia.

Ocular Infections

HSV ocular infections may involve the conjunctiva, cornea, or retina and may be primary or recurrent. Conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis is usually unilateral and is often associated with blepharitis and tender preauricular lymphadenopathy. The conjunctiva appears edematous but there is rarely purulent discharge. Vesicular lesions may be seen on the lid margins and periorbital skin. Patients typically have fever. Untreated infection generally resolves in 2-3 wk. Obvious corneal involvement is rare, but when it occurs it can produce ulcers that are described as appearing dendritic or geographic. Extension to the stroma is uncommon although more likely to occur in patients inadvertently treated with corticosteroids. When it occurs, it may be associated with corneal edema, scarring, and corneal perforation. Recurrent infections tend to involve the underlying stroma and can cause progressive corneal scarring and injury that can lead to blindness.

Retinal infections are rare and are more likely among infants with neonatal herpes and immunocompromised persons with disseminated HSV infections.

Central Nervous System Infections

HSV encephalitis is the leading cause of sporadic, nonepidemic encephalitis in children and adults in the United States. It is an acute necrotizing infection generally involving the frontal and/or temporal cortex and the limbic system and, beyond the neonatal period, is almost always caused by HSV-1. The infection may manifest as nonspecific findings, including fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, vomiting, generalized seizures, and alteration of consciousness. Injury to the frontal or temporal cortex or limbic system may produce findings more indicative of HSV encephalitis, including anosmia, memory loss, peculiar behavior, expressive aphasia and other changes in speech, hallucinations, and focal seizures. The untreated infection progresses to coma and death in 75% of cases. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) typically shows a moderate number of mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, a mildly elevated protein concentration, a normal or slightly decreased glucose concentration, and often a moderate number of erythrocytes. HSV has also been associated with autoimmune encephalitis (see Chapter 616.4 ).

HSV is also a cause of aseptic meningitis and is the most common cause of recurrent aseptic meningitis (Mollaret meningitis ).

Infections in Immunocompromised Persons

Severe, life-threatening HSV infections can occur in patients with compromised immune functions, including neonates, the severely malnourished, those with primary or secondary immunodeficiency diseases (including AIDS), and those receiving some immunosuppressive regimens, particularly for cancer and organ transplantation. Mucocutaneous infections, including mucositis and esophagitis, are most common, although their presentations may be atypical and can result in lesions that slowly enlarge, ulcerate, become necrotic, and extend to deeper tissues. Other HSV infections include tracheobronchitis, pneumonitis, and anogenital infections. Disseminated infection can result in a sepsis-like presentation, with liver and adrenal involvement, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and shock.

Perinatal Infections

HSV infection may be acquired in utero, during the birth process, or during the neonatal period. Intrauterine and postpartum infections are well described but occur infrequently. Postpartum transmission may be from the mother or another adult with a nongenital (typically HSV-1) infection such as herpes labialis. Most cases of neonatal herpes result from maternal infection and transmission, usually during passage through an infected birth canal of a mother with asymptomatic genital herpes. Transmission is well documented in infants delivered by cesarean section. Fewer than 30% of mothers of an infant with neonatal herpes have a history of genital herpes. The risk for infection is higher in infants born to mothers with primary genital infection (>30%) than with recurrent genital infection (<2%). Use of scalp electrodes may also increase risk. There also have been rare cases of neonatal herpes associated with Jewish ritual circumcisions, but only with ritual oral contact with the circumcision site.

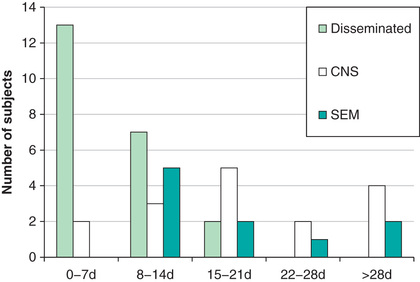

Neonatal HSV infection is thought to never be asymptomatic. Its clinical presentation reflects timing of infection, portal of entry, and extent of spread. Infants with intrauterine infection typically have skin vesicles or scarring, eye findings including chorioretinitis and keratoconjunctivitis, and microcephaly or hydranencephaly that are present at delivery. Few infants survive without therapy, and those who do generally have severe sequelae. Infants infected during delivery or the postpartum period present with 1 of the following 3 patterns of disease: (1) disease localized to the skin, eyes, or mouth; (2) encephalitis with or without skin, eye, and mouth disease; and (3) disseminated infection involving multiple organs, including the brain, lungs, liver, heart, adrenals, and skin (Fig. 279.4 ). Approximately 20% present between 5 and 9 wk of age.

Infants with skin, eye, and mouth disease generally present at 5-11 days of life and typically demonstrate a few small vesicles, particularly on the presenting part or at sites of trauma such as sites of scalp electrode placement. If untreated, skin, eye, and mouth disease in infants may progress to encephalitis or disseminated disease.

Infants with encephalitis typically present at 8-17 days of life with clinical findings suggestive of bacterial meningitis, including irritability, lethargy, poor feeding, poor tone, and seizures. Fever is relatively uncommon, and skin vesicles occur in only approximately 60% of cases (Fig. 279.5 ). If untreated, 50% of infants with HSV encephalitis die and most survivors have severe neurologic sequelae.

Infants with disseminated HSV infections generally become ill at 5-11 days of life. Their clinical picture is similar to that of infants with bacterial sepsis, consisting of hyperthermia or hypothermia, irritability, poor feeding, and vomiting. They may also exhibit respiratory distress, cyanosis, apneic spells, jaundice, purpuric rash, and evidence of central nervous system infection; seizures are common. Skin vesicles are seen in approximately 75% of cases. If untreated, the infection causes shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation; approximately 90% of these infants die, and most survivors have severe neurologic sequelae.

Infants with neonatal herpes whose mothers received antiherpes antiviral drugs in the weeks prior to delivery may present later than their untreated counterparts; whether the natural history of the infection in these infants is different is an unanswered question.

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of HSV infections, particularly life-threatening infections and genital herpes, should be confirmed by laboratory test, preferably isolation of virus or detection of viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Histologic findings or imaging studies may support the diagnosis but should not substitute for virus-specific tests. HSV immunoglobulin M tests are notoriously unreliable, and the demonstration of a 4-fold or greater rise in HSV-specific immunoglobulin G titers between acute and convalescent serum samples is useful only in retrospect.

The highest yield for virus cultures comes from rupturing a suspected herpetic vesicle and vigorously rubbing the base of the lesion to collect fluid and cells. Culturing dried, crusted lesions is generally of low yield. Although not as sensitive as viral culture, direct detection of HSV antigens in clinical specimens can be done rapidly and has very good specificity. The use of DNA amplification methods such as PCR for detection of HSV DNA is highly sensitive and specific and in some instances can be performed rapidly. It is the test of choice in examining CSF in cases of suspected HSV encephalitis.

Evaluation of the neonate with suspected HSV infection should include cultures of suspicious lesions as well as eye and mouth swabs and PCR of both CSF and blood. In neonates testing for elevation of liver enzymes may provide indirect evidence of HSV dissemination to visceral organs. Culture or antigen detection should be used in evaluating lesions associated with suspected acute genital herpes. HSV-2 type-specific antibody tests are useful for evaluating sexually experienced adolescents or young adults who have a history of unexplained recurrent nonspecific urogenital signs and symptoms, but these tests are less useful for general screening in populations in which HSV-2 infections are of low prevalence.

Because most HSV diagnostic tests take at least a few days to complete, treatment should not be withheld but rather initiated promptly so as to ensure the maximum therapeutic benefit.

Laboratory Findings

Most self-limited HSV infections cause few changes in routine laboratory parameters. Mucocutaneous infections may cause a moderate polymorphonuclear leukocytosis. In HSV meningoencephalitis there can be an increase in mononuclear cells and protein in CSF, the glucose content may be normal or reduced, and red blood cells may be present. The electroencephalogram and MRI of the brain may show temporal lobe abnormalities in HSV encephalitis beyond the neonatal period. Encephalitis in the neonatal period tends to be more global and not limited to the temporal lobe (Fig. 279.6 ). Disseminated infection may cause elevated liver enzymes, thrombocytopenia, and abnormal coagulation.

Treatment

See Chapter 272 for more information about principles of antiviral therapy.

Three antiviral drugs are available in the United States for the management of HSV infections, namely acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. All 3 are available in oral form, but only acyclovir is available in a suspension form. Acyclovir has the poorest bioavailability and hence requires more frequent dosing. Valacyclovir, a prodrug of acyclovir, and famciclovir, a prodrug of penciclovir, both have very good oral bioavailability and are dosed once or twice daily. Acyclovir and penciclovir are also available in a topical form, but these preparations provide limited or no benefit to patients with recurrent mucocutaneous HSV infections. Only acyclovir has an intravenous formulation. Early initiation of therapy results in the maximal therapeutic benefit. All 3 drugs have exceptional safety profiles and are safe to use in pediatric patients. Doses should be modified in patients with renal impairment.

Resistance to acyclovir and penciclovir is rare in immunocompetent persons but does occur in immunocompromised persons. Virus isolates from immunocompromised persons whose HSV infection is not responding or is worsening with acyclovir therapy should be tested for drug sensitivities. Foscarnet and cidofovir have been used in the treatment of HSV infections caused by acyclovir-resistant mutants.

Topical trifluridine and topical ganciclovir are used in the treatment of herpes keratitis.

Patients with genital herpes also require counseling to address psychosocial issues, including possible stigma, and to help them understand the natural history and management of this chronic infection.

Acute Mucocutaneous Infections

For gingivostomatitis, oral acyclovir (15 mg/kg/dose 5 times a day PO for 7 days; maximum: 1 g/day) started within 72 hr of onset reduces the severity and duration of the illness. Pain associated with swallowing may limit oral intake of infants and children, putting them at risk for dehydration. Intake should be encouraged through the use of cold beverages, ice cream, and yogurt.

For herpes labialis, oral treatment is superior to topical antiviral therapy. For treatment of a recurrence in adolescents, oral valacyclovir (2,000 mg bid PO for 1 day), acyclovir (200-400 mg 5 times daily PO for 5 days), or famciclovir (1,500 mg once daily PO for 1 day) shortens the duration of the episode. Long-term daily use of oral acyclovir (400 mg bid PO) or valacyclovir (500 mg once daily PO) has been used to prevent recurrences in individuals with frequent or severe recurrences.

Anecdotal reports suggest that treatment of adolescents with herpes gladiatorum with oral acyclovir (200 mg 5 times daily PO for 7-10 days) or valacyclovir (500 mg bid PO for 7-10 days) at the first signs of the outbreak can shorten the course of the recurrence. For patients with a history of recurrent herpes gladiatorum, chronic daily prophylaxis with valacyclovir (500-1,000 mg daily) has been reported to prevent recurrences.

There are no clinical trials assessing the benefit of antiviral treatment for herpetic whitlow. High-dose oral acyclovir (1,600-2,000 mg/day divided in 2-3 doses PO for 10 days) started at the first signs of illness has been reported to abort some recurrences and reduce the duration of others in adults.

A clinical trial in adults has established the effectiveness of oral acyclovir (200 mg 5 times a day PO for 5 days) in the treatment of eczema herpeticum; however, serious infections should be treated with intravenous acyclovir. Oral-facial HSV infections can reactivate after cosmetic facial laser resurfacing, causing extensive disease and scarring. Treatment of adults beginning the day before the procedure with either valacyclovir (500 mg twice daily PO for 10-14 days) or famciclovir (250-500 mg bid PO for 10 days) has been reported to be effective in preventing the infections. HSV infections in burn patients can be severe or life-threatening and have been treated with intravenous acyclovir (10-20 mg/kg/day divided every 8 hr IV).

Antiviral drugs are not effective in the treatment of HSV-associated erythema multiforme, but their daily use as for herpes labialis prophylaxis prevents reoccurrences of erythema multiforme.

Genital Herpes

Pediatric patients, usually adolescents or young adults, with suspected first-episode genital herpes should be treated with antiviral therapy. Treatment of the initial infection reduces the severity and duration of the illness but has no effect on the frequency of subsequent recurrent infections. Treatment options for adolescents include acyclovir (400 mg tid PO for 7-10 days), famciclovir (250 mg tid PO for 7-10 days), or valacyclovir (1,000 mg bid PO for 7-10 days). The twice-daily valacyclovir option avoids treatment during school hours. For smaller children, acyclovir suspension can be used at a dose of 10-20 mg/kg/dose 4 times daily not to exceed the adult dose. The 1st episode of genital herpes can be extremely painful, and use of analgesics is generally indicated. All patients with genital herpes should be offered counseling to help them deal with psychosocial issues and understand the chronic nature of the illness.

There are 3 strategic options regarding the management of recurrent infections. The choice should be guided by several factors, including the frequency and severity of the recurrent infections, the psychologic impact of the illness on the patient, and concerns regarding transmission to a susceptible sexual partner. Option 1 is no therapy; option 2 is episodic therapy; and option 3 is long-term suppressive therapy. For episodic therapy, treatment should be initiated at the first signs of an outbreak. Recommended choices for episodic therapy in adolescents include famciclovir (1,000 mg bid PO for 1 day), acyclovir (800 mg tid PO for 2 days), or valacyclovir (500 mg bid PO for 3 days or 1,000 mg once daily for 5 days). Long-term suppressive therapy offers the advantage that it prevents most outbreaks, improves patient quality of life in terms of the psychosocial impact of genital herpes, and, with daily valacyclovir therapy, also reduces (but does not eliminate) the risk for sexual transmission to a susceptible sexual partner. Options for long-term suppressive therapy are acyclovir (400 mg bid PO), famciclovir (250 mg bid PO), and valacyclovir (500 or 1,000 mg qd PO).

Ocular Infections

HSV ocular infections can result in blindness. Management should involve consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Central Nervous System Infections

Patients older than neonates who have herpes encephalitis should be promptly treated with intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hr given as a 1 hr infusion for 14-21 days). Treatment for increased intracranial pressure, management of seizures, and respiratory compromise may be required.

Infections in Immunocompromised Persons

Severe mucocutaneous and disseminated HSV infections in immunocompromised patients should be treated with intravenous acyclovir (30 mg/kg per day, in 3 divided doses for 7-14 days) until there is evidence of resolution of the infection. Oral antiviral therapy with acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir has been used for treatment of less-severe HSV infections and for suppression of recurrences during periods of significant immunosuppression. Drug resistance does occur occasionally in immunocompromised patients, and in individuals whose HSV infection does not respond to antiviral drug therapy, viral isolates should be tested to determine sensitivity. Acyclovir-resistant viruses are often also resistant to famciclovir but may be sensitive to foscarnet or cidofovir.

Perinatal Infections

All infants with proven or suspected neonatal HSV infection should be treated immediately with high-dose intravenous acyclovir (60 mg/kg/day divided every 8 hr IV). Treatment may be discontinued in infants shown by laboratory testing not to be infected. Infants with HSV disease limited to skin, eyes, and mouth should be treated for 14 days, whereas those with disseminated or central nervous system disease should receive 21 days of therapy. Patients receiving high-dose therapy should be monitored for neutropenia.

Suppressive oral acyclovir therapy for 6 mo after completion of the intravenous therapy has been shown to improve the neurodevelopment of infants with central nervous system infection and to prevent cutaneous recurrences in infants regardless of disease pattern. Infants should receive 300 mg/m2 per dose 3 times daily for 6 mo. The absolute neutrophil count should be measured at weeks 2 and 4 after initiation of treatment and then monthly.

Prognosis

Most HSV infections are self-limiting, last from a few days (for recurrent infections) to 2-3 wk (for primary infections), and heal without scarring. Recurrent oral-facial herpes in a patient who has undergone dermabrasion or laser resurfacing can be severe and lead to scarring. Because genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection, it can be stigmatizing, and its psychologic consequences may be much greater than its physiologic effects. Some HSV infections can be severe and may have grave consequences without prompt antiviral therapy. Life-threatening conditions include neonatal herpes, herpes encephalitis, and HSV infections in immunocompromised patients, burn patients, and severely malnourished infants and children. Recurrent ocular herpes can lead to corneal scarring and blindness.

Prevention

Transmission of infection occurs through exposure to virus either as the result of skin-to-skin contact or from contact with contaminated secretions. Good handwashing and, when appropriate, the use of gloves provide healthcare workers with excellent protection against HSV infection in the workplace. Healthcare workers with active oral-facial herpes or herpetic whitlow should take precautions, particularly when caring for high-risk patients such as newborns, immunocompromised individuals, and patients with chronic skin conditions. Patients and parents should be advised about good hygienic practices, including handwashing and avoiding contact with lesions and secretions, during active herpes outbreaks. Schools and daycare centers should clean shared toys and athletic equipment such as wrestling mats at least daily after use. Athletes with active herpes infections who participate in contact sports such as wrestling and rugby should be excluded from practice or games until the lesions are completely healed. Genital herpes can be prevented by avoiding genital-genital and oral-genital contact. The risk for acquiring genital herpes can be reduced but not eliminated through the correct and consistent use of condoms. Male circumcision is associated with a reduced risk of acquiring genital HSV infection. The risk for transmitting genital HSV-2 infection to a susceptible sexual partner can be reduced but not eliminated by the daily use of oral valacyclovir by the infected partner.

For pregnant women with active genital herpes at the time of delivery, the risk for mother-to-child transmission can be reduced but not eliminated by delivering the baby via a cesarean section. The risk for recurrent genital herpes, and therefore the need for cesarean delivery, can be reduced but not eliminated in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes by the daily use of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir during the last 4 wk of gestation, which is recommended by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. There are documented cases of neonatal herpes occurring in infants delivered by cesarean section, as well as in infants born to mothers who have been appropriately treated with antiherpes antiviral drugs for the last month of gestation. Hence a history of cesarean delivery or antiviral treatment at term does not rule out consideration of neonatal herpes.

Infants delivered vaginally to women with first-episode genital herpes are at very high risk for acquiring HSV infection. The nasopharynx, mouth, conjunctivae, rectum, and umbilicus should be cultured (some add PCR surface testing) at delivery and 12 to 24 hr after birth. Some also recommend HSV-PCR on blood. Some authorities recommend that these infants receive anticipatory acyclovir therapy for at least 2 wk, and others treat such infants if signs develop or if surface cultures beyond 12-24 hr of life are positive. Infants delivered to women with a history of recurrent genital herpes are at low risk for development of neonatal herpes. In this setting, parents should be educated about the signs and symptoms of neonatal HSV infection and should be instructed to seek care without delay at the first suggestion of infection. When the situation is in doubt, infants should be evaluated and tested with surface culture (and PCR) for neonatal herpes as well as with PCR on blood and CSF; intravenous acyclovir is begun until culture and PCR results are negative or until another explanation can be found for the signs and symptoms.

Recurrent genital HSV infections can be prevented by the daily use of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir, and these drugs have been used to prevent recurrences of oral-facial (labialis) and cutaneous (gladiatorum) herpes. Oral and intravenous acyclovir has also been used to prevent recurrent HSV infections in immunocompromised patients. Use of sun blockers is reported to be effective in preventing recurrent oral-facial herpes in patients with a history of sun-induced recurrent disease.