Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ronen E. Stein, Robert N. Baldassano

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is used to represent 2 distinctive disorders of idiopathic chronic intestinal inflammation: Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Their respective etiologies are poorly understood, and both disorders are characterized by unpredictable exacerbations and remissions. The most common time of onset of IBD is during the preadolescent/adolescent era and young adulthood. A bimodal distribution has been shown with an early onset at 10-20 yr of age and a second, smaller peak at 50-80 yr of age. Approximately 25% of patients present before 20 yr of age. IBD may begin as early as the 1st yr of life, and an increased incidence among young children has been observed since the turn of the 20th century. Children with early-onset IBD are more likely to have colonic involvement. In developed countries, these disorders are the major causes of chronic intestinal inflammation in children beyond the first few yr of life. A third, less-common category, indeterminate colitis , represents approximately 10% of pediatric patients.

Genetic and environmental influences are involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. The prevalence of Crohn disease in the United States is much lower for Hispanics and Asians than for whites and blacks. The risk of IBD in family members of an affected person has been reported in the range of 7–30%; a child whose parents both have IBD has a >35% chance of acquiring the disorder. Relatives of a patient with ulcerative colitis have a greater risk of acquiring ulcerative colitis than Crohn disease, whereas relatives of a patient with Crohn disease have a greater risk of acquiring this disorder; the 2 diseases can occur in the same family. The risk of occurrence of IBD among relatives of patients with Crohn disease is somewhat greater than for patients with ulcerative colitis.

The importance of genetic factors in the development of IBD is noted by a higher chance that both twins will be affected if they are monozygotic rather than dizygotic. The concordance rate in twins is higher in Crohn disease (36%) than in ulcerative colitis (16%). Genetic disorders that have been associated with IBD include Turner syndrome, the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, glycogen storage disease type Ib, and various immunodeficiency disorders. In 2001, the first IBD gene, NOD2, was identified through association mapping. A few months later, the IBD 5 risk haplotype was identified. These early successes were followed by a long period without notable risk factor discovery. Since 2006, the year of the first published genome-wide array study on IBD, there has been an exponential growth in the set of validated genetic risk factors for IBD (Table 362.1 ).

Table 362.1

Selection of Most Important Genes Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Most Commonly Associated Physiological Functions and Pathways

| GENE NAME | ASSOCIATED DISEASE | GENE FUNCTION AND ASSOCIATED PATHWAYS | PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTION | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOD2 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain- containing protein 2 | Crohn disease | Bacterial recognition and response, NFκB activation and autophagy and apoptosis | Innate mucosal defense |

| IL10 | Interleukin 10 | Crohn disease | Antiinflammatory cytokine, NFκB inhibition, JAK-STAT regulation | Immune tolerance |

| IL10RA | Interleukin 10 receptor A | Crohn disease | Antiinflammatory cytokine receptor, NFκB inhibition, JAK-STAT regulation | Immune tolerance |

| IL10RB | Interleukin 10 receptor B | Crohn disease | Antiinflammatory cytokine receptor, NFκB inhibition, JAK-STAT regulation | Immune tolerance |

| IL23R | Interleukin 23 receptor | Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis | Immune regulation, proinflammatory pathways—JAK-STAT regulation | Interleukin 23/T helper 17 |

| TKY2 | Tyrosine kinase 2 | Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis | Inflammatory pathway signaling (interleukin 10 and 6 etc) through intracellular activity | Interleukin 23/T helper 17 |

| IRGM | Immunity related GTPase M | Crohn disease | Autophagy and apoptosis in cells infected with bacteria | Autophagy |

| ATG16L1 | Autophagy related 16 like 1 | Crohn disease | Autophagy and apoptotic pathways | Autophagy |

| SLC22A4 | Solute carrier family 22 member 4 | Crohn disease | Cellular antioxidant transporter | Solute transporters |

| CCL2 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 | Crohn disease | Cytokine involved in chemotaxis for monocytes | Immune cell recruitment |

| CARD9 | Caspase recruitment domain family member 9 | Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis | Apoptosis regulation and NFκB pathway activation | Oxidative stress |

| IL2 | Interleukin 2 | Ulcerative colitis | Cytokine involved in immune cell activation | T-cell regulation |

| MUC19 | Mucin 19 | Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis | Gel-forming mucin protein | Epithelial barrier |

JAK-STAT, Janus kinase-signal transducers and activators of transcription; NFκB, nuclear factor κ-light chain enhancer of activated B cells.

From Ashton JJ, Ennis S, Beattie RM: Early-onset paediatric inflammatory bowel disease, Lancet 1:147–158, 2017, Table 1, p 148.

A perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody is found in approximately 70% of patients with ulcerative colitis compared with <20% of those with Crohn disease and is believed to represent a marker of genetically controlled immunoregulatory disturbance. Approximately 55% of those with Crohn disease are positive for anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody. Since the importance of these were first described, multiple other serologic and immune markers of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis have been recognized.

IBD is caused by dysregulated or inappropriate immune response to environmental factors in a genetically susceptible host. An abnormality in intestinal mucosal immunoregulation may be of primary importance in the pathogenesis of IBD, involving activation of cytokines, triggering a cascade of reactions that results in bowel inflammation. These cytokines are recognized as known or potential targets for IBD therapies.

Multiple environmental factors are recognized to be involved in the pathogenesis of IBD, none more critical than the gut microbiota. The increasing incidence of IBD over time is likely in part attributable to alterations in the microbiome. Evidence includes association between IBD and residence in or immigration to industrialized nations, a Western diet , increased use of antibiotics at a younger age, high rates of vaccination, and less exposure to microbes at a young age. While gut microbes likely play an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD, the exact mechanism needs to be elucidated further. Some environmental factors are disease specific; for example, cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Crohn disease but paradoxically protects against ulcerative colitis.

It is usually possible to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease by the clinical presentation and radiologic, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings (Table 362.2 ). It is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis in approximately 10% of patients with chronic colitis; this disorder is called indeterminate colitis. Occasionally, a child initially believed to have ulcerative colitis on the basis of clinical findings is subsequently found to have Crohn colitis. This is particularly true for the youngest patients, because Crohn disease in this patient population can more often manifest as exclusively colonic inflammation, mimicking ulcerative colitis. The medical treatments of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis overlap.

Table 362.2

Extraintestinal manifestations occur slightly more commonly with Crohn disease than with ulcerative colitis (Table 362.3 ). Growth retardation is seen in 15–40% of children with Crohn disease at diagnosis. Decrease in height velocity occurs in nearly 90% of patients with Crohn disease diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. Of the extraintestinal manifestations that occur with IBD, joint, skin, eye, mouth, and hepatobiliary involvement tend to be associated with colitis, whether ulcerative or Crohn. The presence of some manifestations, such as peripheral arthritis, erythema nodosum, and anemia, correlates with activity of the bowel disease. Activity of pyoderma gangrenosum correlates less well with activity of the bowel disease, whereas sclerosing cholangitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and sacroiliitis do not correlate with intestinal disease. Arthritis occurs in 3 patterns: migratory peripheral arthritis involving primarily large joints, ankylosing spondylitis, and sacroiliitis. The peripheral arthritis of IBD tends to be nondestructive. Ankylosing spondylitis begins in the 3rd decade and occurs most commonly in patients with ulcerative colitis who have the human leukocyte antigen B27 phenotype. Symptoms include low back pain and morning stiffness; back, hips, shoulders, and sacroiliac joints are typically affected. Isolated sacroiliitis is usually asymptomatic but is common when a careful search is performed. Among the skin manifestations, erythema nodosum is most common. Patients with erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum have a high likelihood of having arthritis as well. Glomerulonephritis, uveitis, and a hypercoagulable state are other rare manifestations that occur in childhood. Cerebral thromboembolic disease has been described in children with IBD.

Table 362.3

Extraintestinal Complications of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Modified from Kugathasan S: Diarrhea. In Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, WB Saunders, p 285.

Chronic Ulcerative Colitis

Ronen E. Stein, Robert N. Baldassano

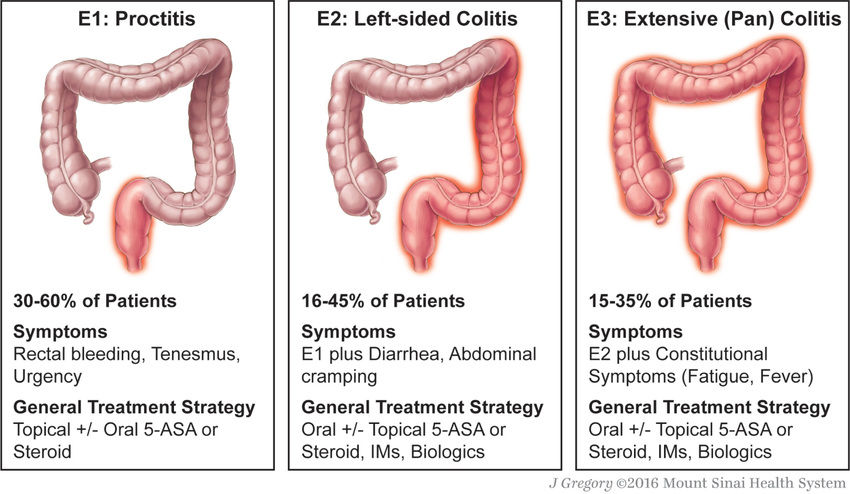

Ulcerative colitis, an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disorder, is localized to the colon and spares the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Disease usually begins in the rectum and extends proximally for a variable distance. When it is localized to the rectum, the disease is ulcerative proctitis, whereas disease involving the entire colon is pancolitis. Approximately 50–80% of pediatric patients have extensive colitis, and adults more commonly have distal disease. Ulcerative proctitis is less likely to be associated with systemic manifestations, although it may be less responsive to treatment than more-diffuse disease. Approximately 30% of children who present with ulcerative proctitis experience proximal spread of the disease. Ulcerative colitis has rarely been noted to present in infancy. Dietary protein intolerance can easily be misdiagnosed as ulcerative colitis in this age group. Dietary protein intolerance (cow's milk protein) is a transient disorder; symptoms are directly associated with the intake of the offending antigen.

The incidence of ulcerative colitis has increased but not to the extent of the increase in Crohn disease; incidence varies with country of origin. The age-specific incidence rates of pediatric ulcerative colitis in North America is 2/100,000 population. The prevalence of ulcerative colitis in northern European countries and the United States varies from 100 to 200/100,000 population. Men are slightly more likely to acquire ulcerative colitis than are women; the reverse is true for Crohn disease.

Clinical Manifestations

Blood, mucus, and pus in the stool as well as diarrhea are the typical presentation of ulcerative colitis. Constipation may be observed in those with proctitis. Symptoms such as tenesmus, urgency, cramping abdominal pain (especially with bowel movements), and nocturnal bowel movements are common. The mode of onset ranges from insidious with gradual progression of symptoms to acute and fulminant (Table 362.4 and Figs. 362.1 and 362.2 ). Fever, severe anemia, hypoalbuminemia, leukocytosis, and more than 5 bloody stools per day for 5 days define fulminant colitis . Chronicity is an important part of the diagnosis; it is difficult to know if a patient has a subacute, transient infectious colitis or ulcerative colitis when a child has had 1-2 wk of symptoms. Symptoms beyond this duration often prove to be secondary to IBD. Anorexia, weight loss, and growth failure may be present, although these complications are more typical of Crohn disease.

Table 362.4

Montreal Classification of Extent and Severity of Ulcerative Colitis

E, extent; S, severity.

From Ordàs I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, et al: Ulcerative colitis, Lancet 380:1606–1616, 2012, Panel 2, p 1610.

Extraintestinal manifestations that tend to occur more commonly with ulcerative colitis than with Crohn disease include pyoderma gangrenosum, sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Iron deficiency can result from chronic blood loss as well as decreased intake. Folate deficiency is unusual but may be accentuated in children treated with sulfasalazine, which interferes with folate absorption. Chronic inflammation and the elaboration of a variety of inflammatory cytokines can interfere with erythropoiesis and result in the anemia of chronic disease. Secondary amenorrhea is common during periods of active disease.

The clinical course of ulcerative colitis is marked by remission and relapse, often without apparent explanation. After treatment of initial symptoms, approximately 5% of children with ulcerative colitis have a prolonged remission (longer than 3 yr). Approximately 25% of children presenting with severe ulcerative colitis require colectomy within 5 yr of diagnosis, compared with only 5% of those presenting with mild disease. It is important to consider the possibility of enteric infection with recurrent symptoms; these infections can mimic a flare-up or actually provoke a recurrence. The use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs is considered by some to predispose to exacerbation.

It is generally believed that the risk of colon cancer begins to increase after 8-10 yr of disease and can then increase by 0.5–1% per yr. The risk is delayed by approximately 10 yr in patients with colitis limited to the descending colon. Proctitis alone is associated with virtually no increase in risk over the general population. Because colon cancer is usually preceded by changes of mucosal dysplasia, it is recommended that patients who have had ulcerative colitis for longer than 8-10 yr be screened with colonoscopy and biopsies every 1-2 yr. Although this is the current standard of practice, it is not clear if morbidity and mortality are changed by this approach. Two competing concerns about this plan of management remain unresolved. The original studies may have overestimated the risk of colon cancer and, therefore, the need for surveillance has been overemphasized; and screening for dysplasia might not be adequate for preventing colon cancer in ulcerative colitis if some cancers are not preceded by dysplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

The major conditions to exclude are infectious colitis, allergic colitis, and Crohn colitis. Every child with a new diagnosis of ulcerative colitis should have stool cultured for enteric pathogens, stool evaluation for Clostridium difficile, ova and parasites, and perhaps serologic studies for amebae (Table 362.5 ). Cytomegalovirus infection can mimic ulcerative colitis or be associated with an exacerbation of existing disease, usually in immunocompromised patients. The most difficult distinction is from Crohn disease because the colitis of Crohn disease can initially appear identical to that of ulcerative colitis, particularly in younger children. The gross appearance of the colitis or development of small bowel disease eventually leads to the correct diagnosis; this can occur years after the initial presentation.

Table 362.5

Infectious Agents Mimicking Inflammatory Bowel Disease

| AGENT | MANIFESTATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| BACTERIAL | |||

| Campylobacter jejuni | Acute diarrhea, fever, fecal blood, and leukocytes | Culture | Common in adolescents, may relapse |

| Yersinia enterocolitica |

Acute → chronic diarrhea, right lower quadrant pain, mesenteric adenitis–pseudoappendicitis, fecal blood, and leukocytes Extraintestinal manifestations, mimics Crohn disease |

Culture | Common in adolescents as fever of unknown origin, weight loss, abdominal pain |

| Clostridium difficile | Postantibiotic onset, watery → bloody diarrhea, pseudomembrane on sigmoidoscopy | Cytotoxin assay |

May be nosocomial Toxic megacolon possible |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Colitis, fecal blood, abdominal pain | Culture and typing | Hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| Salmonella | Watery → bloody diarrhea, foodborne, fecal leukocytes, fever, pain, cramps | Culture | Usually acute |

| Shigella | Watery → bloody diarrhea, fecal leukocytes, fever, pain, cramps | Culture | Dysentery symptoms |

| Edwardsiella tarda | Bloody diarrhea, cramps | Culture | Ulceration on endoscopy |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Cramps, diarrhea, fecal blood | Culture |

May be chronic Contaminated drinking water |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | Diarrhea, cramps | Culture | Shellfish source |

| Tuberculosis |

Rarely bovine, now Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ileocecal area, fistula formation |

Culture, purified protein derivative, biopsy | Can mimic Crohn disease |

| PARASITES | |||

| Entamoeba histolytica | Acute bloody diarrhea and liver abscess, colic | Trophozoite in stool, colonic mucosal flask ulceration, serologic tests | Travel to endemic area |

| Giardia lamblia | Foul-smelling, watery diarrhea, cramps, flatulence, weight loss; no colonic involvement | “Owl”-like trophozoite and cysts in stool; rarely duodenal intubation | May be chronic |

| AIDS-ASSOCIATED ENTEROPATHY | |||

| Cryptosporidium | Chronic diarrhea, weight loss | Stool microscopy | Mucosal findings not like inflammatory bowel disease |

| Isospora belli | As in Cryptosporidium | Tropical location | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Colonic ulceration, pain, bloody diarrhea | Culture, biopsy | More common when on immunosuppressive medications |

At the onset, the colitis of hemolytic uremic syndrome may be identical to that of early ulcerative colitis. Ultimately, signs of microangiopathic hemolysis (the presence of schistocytes on blood smear), thrombocytopenia, and subsequent renal failure should confirm the diagnosis of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Although Henoch-Schönlein purpura can manifest as abdominal pain and bloody stools, it is not usually associated with colitis. Behçet disease can be distinguished by its typical features (see Chapter 186 ). Other considerations are radiation proctitis, viral colitis in immunocompromised patients, and ischemic colitis (Table 362.6 ). In infancy, dietary protein intolerance can be confused with ulcerative colitis, although the former is a transient problem that resolves on removal of the offending protein, and ulcerative colitis is extremely rare in this age group. Hirschsprung disease can produce an enterocolitis before or within months after surgical correction; this is unlikely to be confused with ulcerative colitis.

Table 362.6

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel-Like Intestinal Disorders Including Monogenetic Diseases

| INFECTION (see Table 362.5 ) |

| AIDS-Associated |

| Toxin |

| Immune–Inflammatory |

|

Severe combined immunodeficiency diseases Common variable immunodeficiency diseases Acquired immunodeficiency states Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 IPEX (immune dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked) syndromes Interleukin-10 signaling defects Autoimmune enteropathy* Hyperimmunoglobulin M syndrome Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndromes Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 X-linked lymphoproliferative syndromes types 1, 2 (XIAP gene) |

| VASCULAR–ISCHEMIC DISORDERS |

| OTHER |

* May be the same as IPEX.

Diagnosis

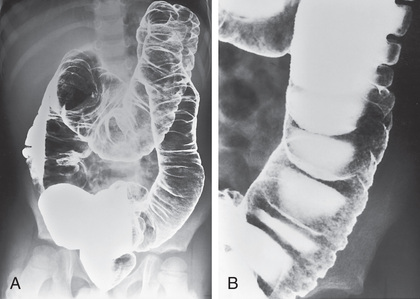

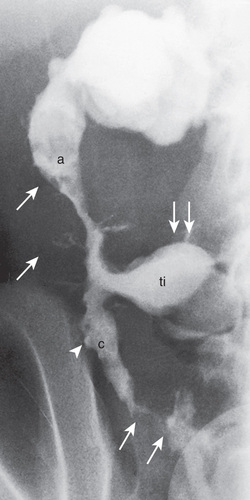

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or ulcerative proctitis requires a typical presentation in the absence of an identifiable specific cause (see Tables 362.5 and 362.6 ) and typical endoscopic and histologic findings (see Tables 362.2 and 362.4 ). One should be hesitant to make a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis in a child who has experienced symptoms for <2-3 wk until infection has been excluded. When the diagnosis is suspected in a child with subacute symptoms, the physician should make a firm diagnosis only when there is evidence of chronicity on colonic biopsy. Laboratory studies can demonstrate evidence of anemia (either iron deficiency or the anemia of chronic disease) or hypoalbuminemia. Although the sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated, they may be normal even with fulminant colitis. An elevated white blood cell count is usually seen only with more-severe colitis. Fecal calprotectin levels are usually elevated and are increasingly recognized to be a more sensitive and specific marker of GI inflammation than typical laboratory parameters. Barium enema is suggestive but not diagnostic of acute (Fig. 362.3 ) or chronic burned-out disease (Fig. 362.4 ).

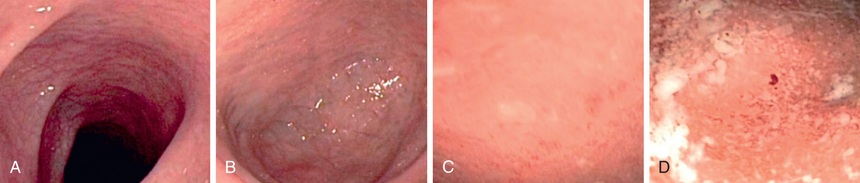

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis must be confirmed by endoscopic and histologic examination of the colon (see Fig. 362.1 ). Classically, disease starts in the rectum with a gross appearance characterized by erythema, edema, loss of vascular pattern, granularity, and friability. There may be a cutoff demarcating the margin between inflammation and normal colon, or the entire colon may be involved. There may be some variability in the intensity of inflammation even in those areas involved. Flexible sigmoidoscopy can confirm the diagnosis; colonoscopy can evaluate the extent of disease and rule out Crohn colitis. A colonoscopy should not be performed when fulminant colitis is suspected because of the risk of provoking toxic megacolon or causing a perforation during the procedure. The degree of colitis can be evaluated by the gross appearance of the mucosa. One does not generally see discrete ulcers, which would be more suggestive of Crohn colitis. The endoscopic findings of ulcerative colitis result from microulcers, which give the appearance of a diffuse abnormality. With very severe chronic colitis, pseudopolyps may be seen. Biopsy of involved bowel demonstrates evidence of acute and chronic mucosal inflammation. Typical histologic findings are cryptitis, crypt abscesses, separation of crypts by inflammatory cells, foci of acute inflammatory cells, edema, mucus depletion, and branching of crypts. The last finding is not seen in infectious colitis. Granulomas, fissures, or full-thickness involvement of the bowel wall (usually on surgical rather than endoscopic biopsy) suggest Crohn disease.

Perianal disease , except for mild local irritation or anal fissures associated with diarrhea, should make the clinician think of Crohn disease. Plain radiographs of the abdomen might demonstrate loss of haustral markings in an air-filled colon or marked dilation with toxic megacolon. With severe colitis, the colon may become dilated; a diameter of >6 cm, determined radiographically, in an adult suggests toxic megacolon. If it is necessary to examine the colon radiologically in a child with severe colitis (to evaluate the extent of involvement or to try to rule out Crohn disease), it is sometimes helpful to perform an upper GI contrast series with small bowel follow-through and then look at delayed films of the colon. A barium enema is contraindicated in the setting of a potential toxic megacolon.

Treatment

Medical

A medical cure for ulcerative colitis is not available; treatment is aimed at controlling symptoms and reducing the risk of recurrence, with a secondary goal of minimizing steroid exposure. The intensity of treatment varies with the severity of the symptoms.

The first drug class to be used with mild or mild-to-moderate colitis is an aminosalicylate. Sulfasalazine is composed of a sulfur moiety linked to the active ingredient 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA). This linkage prevents the premature absorption of the medication in the upper GI tract, allowing it to reach the colon, where the 2 components are separated by bacterial cleavage. The dose of sulfasalazine is 30-100 mg/kg/24 hr (divided into 2-4 doses). Generally, the dose is not more than 2-4 g/24 hr. Hypersensitivity to the sulfa component is the major side effect of sulfasalazine and occurs in 10–20% of patients. Because of poor tolerance, sulfasalazine is used less commonly than other, better tolerated 5-ASA preparations (mesalamine, 50-100 mg/kg/day; balsalazide 2.25-6.75 g/day). Sulfasalazine and the 5-ASA preparations effectively treat active ulcerative colitis and prevent recurrence. It is recommended that the medication be continued even when the disorder is in remission. These medications might also modestly decrease the lifetime risk of colon cancer.

Approximately 5% of patients have an allergic reaction to 5-ASA, manifesting as rash, fever, and bloody diarrhea, which can be difficult to distinguish from symptoms of a flare of ulcerative colitis. 5-ASA can also be given in enema or suppository form and is especially useful for proctitis. Hydrocortisone enemas are used to treat proctitis as well, but they are probably not as effective. A combination of oral and rectal 5-ASA as well as monotherapy with rectal preparation has been shown to be more effective than just oral 5-ASA for distal colitis. Extended release budesonide may also induce remission in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis.

Probiotics are effective in adults for maintenance of remission for ulcerative colitis, although they do not induce remission during an active flare. The most promising role for probiotics has been to prevent pouchitis, a common complication following colectomy and ileal–pouch anal anastomosis surgery.

Children with moderate to severe pancolitis or colitis that is unresponsive to 5-ASA therapy should be treated with corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone. The usual starting dose of prednisone is 1-2 mg/kg/24 hr (40-60 mg maximum dose). This medication can be given once daily. With severe colitis, the dose can be divided twice daily and can be given intravenously. Steroids are considered an effective medication for acute flares, but they are not appropriate maintenance medications because of loss of effect and side effects, including growth retardation, adrenal suppression, cataracts, osteopenia, aseptic necrosis of the head of the femur, glucose intolerance, risk of infection, mood disturbance, and cosmetic effects.

For a hospitalized patient with persistence of symptoms despite intravenous steroid treatment for 3-5 days, escalation of therapy or surgical options should be considered. The validated pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index can be used to help determine current disease severity based on clinical factors and help determine who is more likely to respond to steroids and those who will likely require escalation of therapy (Table 362.7 ).

Table 362.7

Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index

| ITEM | POINTS |

|---|---|

| (1) Abdominal Pain | |

| No pain | 0 |

| Pain can be ignored | 5 |

| Pain cannot be ignored | 10 |

| (2) Rectal Bleeding | |

| None | 0 |

| Small amount only, in <50% of stools | 10 |

| Small amount with most stools | 20 |

| Large amount (>50% of the stool content) | 30 |

| (3) Stool Consistency of Most Stools | |

| Formed | 0 |

| Partially formed | 5 |

| Completely unformed | 10 |

| (4) Number of Stools Per 24 hr | |

| 0-2 | 0 |

| 3-5 | 5 |

| 6-8 | 10 |

| >8 | 15 |

| (5) Nocturnal Stools (Any Episode Causing Wakening) | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 10 |

| (6) Activity Level | |

| No limitation of activity | 0 |

| Occasional limitation of activity | 5 |

| Severe restricted activity | 10 |

| Sum of Index (0-85) | |

With medical management, most children are in remission within 3 mo; however, 5–10% continue to have symptoms unresponsive to treatment beyond 6 mo. Many children with disease requiring frequent corticosteroid therapy are started on immunomodulators such as azathioprine (2.0-2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6-mercaptopurine (1-1.5 mg/kg/day). Uncontrolled data suggest a corticosteroid-sparing effect in many treated patients. This is not an appropriate choice in a steroid nonresponsive patient with acute severe colitis because of longer onset of action. Lymphoproliferative disorders are associated with thiopurine use. Cyclosporine, which is associated with improvement in some children with severe or fulminant colitis, is rarely used owing to its high side-effect profile, its inability to change the natural history of disease, and the increasing use of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which is also effective in cases of fulminant colitis. Infliximab is effective for induction and maintenance therapy in children and adults with moderate to severe disease. TNF blocking agents are associated with an increased risk of infection (particularly tuberculosis) and malignancies (lymphoma, leukemia). Adalimumab is also approved for treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in adults. Vedolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits adhesion and migration of leukocytes into the GI tract, is approved for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in adults. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, is also approved for treatment of moderate to severe adult ulcerative colitis. A specific combination of 3-4 wide-spectrum oral antibiotics given over 2-3 wk may be effective in treating severe pediatric ulcerative colitis refractory to other therapies but is being further studied in children.

Surgical

Colectomy is performed for intractable disease, complications of therapy, and fulminant disease that is unresponsive to medical management. No clear benefit of the use of total parenteral nutrition or a continuous enteral elemental diet in the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis has been noted. Nevertheless, parenteral nutrition is used if oral intake is insufficient so that the patient will be nutritionally ready for surgery if medical management fails. With any medical treatment for ulcerative colitis, the clinician should always weigh the risk of the medication or therapy against the fact that colitis can be successfully treated surgically.

Surgical treatment for intractable or fulminant colitis is total colectomy. The optimal approach is to combine colectomy with an endorectal pull-through, where a segment of distal rectum is retained and the mucosa is stripped from this region. The distal ileum is pulled down and sutured at the internal anus with a J pouch created from ileum immediately above the rectal cuff. This procedure allows the child to maintain continence. Commonly, a temporary ileostomy is created to protect the delicate anastomosis between the sleeve of the pouch and the rectum. The ileostomy is usually closed within several months, restoring bowel continuity. At that time, stool frequency is often increased but may be improved with loperamide. The major complication of this operation is pouchitis, which is a chronic inflammatory reaction in the pouch, leading to bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and, occasionally, low-grade fever. The cause of this complication is unknown, although it is more common when the ileal pouch has been constructed for ulcerative colitis than for other indications (e.g., familial polyposis coli). Pouchitis is seen in 30–40% of patients who had ulcerative colitis. It commonly responds to treatment with oral metronidazole or ciprofloxacin. Probiotics have also been shown to decrease the rate of pouchitis as well as the recurrence of pouchitis following antibiotic therapy.

Support

Psychosocial support is an important part of therapy for this disorder. This may include adequate discussion of the disease manifestations and management between patient and physician, psychologic counseling for the child when necessary, and family support from a social worker or family counselor. Patient support groups have proved helpful for some families. Children with ulcerative colitis should be encouraged to participate fully in age-appropriate activities; however, activity may need to be reduced during periods of disease exacerbation.

Prognosis

The course of ulcerative colitis is marked by remissions and exacerbations. Most children with this disorder respond initially to medical management. Many children with mild manifestations continue to respond well to medical management and may stay in remission on a prophylactic 5-ASA preparation for long periods. An occasional child with mild onset, however, experiences intractable symptoms later. Beyond the 1st decade of disease, the risk of development of colon cancer begins to increase rapidly. The risk of colon cancer may be diminished with surveillance colonoscopies beginning after 8-10 yr of disease. Detection of significant dysplasia on biopsy would prompt colectomy.

Bibliography

AGA Institute Medical Position Panel. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology . 2010;138:738–745.

Agarwal S, Mayer L. Primary immunodeficiency: heeding suspicious gastrointestinal symptoms: diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in patients with primary immunodeficiency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol . 2013;11:1050–1063.

Alfadda AA, Storr MA, Shaffer EA. Eosinophilic colitis: an update on pathophysiology and treatment. Br Med Bull . 2011;100:59–72.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Xavier RJ. How does genotype influence disease phenotype in inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2013;19:2021–2030.

Anderson CA, Boucher G, Lees CW, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet . 2011;43:246–252.

Beaugerie L, Itzkowitz SH. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(15):1441–1452.

Blaydon DC, Biancheri P, Di WL, et al. Inflammatory skin and bowel disease linked to ADAM17 deletion. N Engl J Med . 2013;365:1502–1508.

Cannioto Z, Berti I, Martelossi S, et al. IBD and IBD mimicking enterocolitis in children younger than 2 years of age. Eur J Pediatr . 2009;168:149–155.

Cleynen I, Boucher G, Jostins L, et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study. Lancet . 2016;387:156–167.

DiLauro S, Crum-Cianflone NF. Ileitis: when it is not Crohn's disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep . 2010;12:249–258.

Dykes DMH, Saeed SA. Imaging for inflammatory bowel disease: the new “sounding board. J Pediatr . 2013;163:625–626.

El-Chammas K, Majeskie A, Simpson P, et al. Red flags in children with chronic abdominal pain and Crohn's disease—a single center experience. J Pediatr . 2013;162:783–787.

Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ . 2013;346:29–34.

Gionchetti P, Rizello F, Helwig U, et al. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology . 2003;124:1202–1209.

Huang JS, Noack D, Rae J, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease caused by a deficiency in p47phox mimicking Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol . 2004;2:690–695.

Hyams JS, Lerer T, Mack D. Outcome following thiopurine use in children with ulcerative colitis: a prospective multicenter registry study. Am J Gastroenterol . 2011;106:981–987.

Jose FA, Heyman MB. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr . 2008;46:124–133.

Kelsen JR, Baldassano RN. The role of monogenic disease in children with very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:566–571.

Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut . 2004;53:1617–1623.

Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr . 2003;143:525–531.

Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2012;380:1909–1914.

Laharie D. Towards therapeutic choices in ulcerative colitis. Lancet . 2017;390:98–99.

Lazzerini M, Bramuzzo M, Maschio M, et al. Thromboembolism in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2011;10:2174–2183.

Leggieri N, Marques-Vidal P, Cerwenka H, et al. Migrated foreign body liver abscess. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2010;89(2):85–95.

Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ. Infliximab versus ciclosporin in severe ulcerative colitis. Lancet . 2012;380:1887–1888.

Maggi U, Rossi G, Avesani EC, et al. Thrombotic storm in a teenager with previously undiagnosed ulcerative colitis. Pediatrics . 2013;131:e1288–e1291.

Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, et al. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr . 2010;50(1):27–31.

Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Baldassano RN. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease . ed 2. Springer Science of Business Media; 2013.

Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Cohen LJ, et al. Infliximab in pediatric ulcerative colitis: two-year follow-up. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr . 2004;38:298–301.

Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology . 2015;149:102–109.

Negrón ME, Rezaie A, Barkema HW, et al. Ulcerative colitis patients with clostridium difficile are at increased risk of death, colectomy, and postoperative complications: a population-based inception cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol . 2016;111:691–704.

Ordàs I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet . 2012;380:1606–1616.

Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet . 2017;389:1218–1228.

Quail MA, Russell RK, Van Limbergen JE, et al. Fecal calprotectin complements routine laboratory investigations in diagnosing childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2009;15:756–759.

Quiros AB, Sanz EA, Ordiz DB, et al. From autoimmune enteropathy to the IPEX (immune dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked) syndrome. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) . 2009;27:208–215.

Ricart E. Current status of mesenchymal stem cell therapy and bone marrow transplantation in IBD. Dig Dis . 2012;30:387–391.

Romano C, Famiani A, Gallizzi R, et al. Indeterminate colitis: a distinctive clinical pattern of inflammatory bowel disease in children. Pediatrics . 2008;122:e1278–e1281.

Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med . 2005;353:2462–2476.

Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, in active ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:616–624.

Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Eng J Med . 2017;376(18):1723–1736.

Schwiertz A, Jacobi M, Frick JS, et al. Microbiota in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr . 2010;157:240–244.

The Medical Letter. Budesonide (Uceris) for ulcerative colitis. Med Lett . 2013;55:23.

The Medical Letter. Budesonide rectal foam (Uceris) for ulcerative colitis. Med Lett . 2015;57(1481):154.

The Medical Letter. Drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. Med Lett . 2014;56:59–66.

The Medical Letter. Ustekinumab (stelara) for Crohn's disease. Med Lett . 2017;59(1511):5–6.

Timmer A, Obermeier F. Reduced risk of ulcerative colitis after appendectomy. BMJ . 2009;338:781–782.

Torres J, Mehandru S, Columbel J, Peyrin-Biroulet F. Crohn's disease. Lancet . 2017;389:741–755.

Turner D, Levine A, Kolho KL, et al. Combination of oral antibiotics may be effective in severe pediatric ulcerative colitis: a preliminary report. J Crohns Colitis . 2012;8(11):1464–1470.

Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, et al. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the porto IBD working group of espghan. Am J Gastroenterol . 2011;106:574–588.

Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, et al. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology . 2014;147:990–1007.

Uhlig HH. Monogenic diseases associated with intestinal inflammation: implications for the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut . 2013;62:1795–1805.

Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet . 2017;389:1756–1770.

Van de Vijver E, Schreuder AB, Cnossen WR, et al. Safely ruling out inflammatory bowel disease in children and teenagers without referral from endoscopy. Arch Dis Child . 2012;97:1014–1018.

Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ, Danese S, et al. Anti-MAdCAM antibody (PF-00547659) for ulcerative colitis (TURANDOT): a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet . 2017;390:135–144.

Yang LS, Alex G, Catto-Smith AG. The use of biologic agents in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2012;24:609–614.

Yen EF, Pardi DS. Non-IBD colitides (eosinophilic, microscopic). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol . 2012;26:611–622.

Crohn Disease (Regional Enteritis, Regional Ileitis, Granulomatous Colitis)

Ronen E. Stein, Robert N. Baldassano

Crohn disease, an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the bowel, involves any region of the alimentary tract from the mouth to the anus. Although there are many similarities between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, there are also major differences in the clinical course and distribution of the disease in the GI tract (see Table 362.2 ). The inflammatory process tends to be eccentric and segmental, often with skip areas (normal regions of bowel between inflamed areas). Although inflammation in ulcerative colitis is limited to the mucosa (except in toxic megacolon), GI involvement in Crohn disease is often transmural .

Compared to adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is more likely to have extensive anatomic involvement. At initial presentation, more than 50% of patients have disease that involves ileum and colon (ileocolitis), 20% have exclusively colonic disease, and upper GI involvement (esophagus, stomach, duodenum) is seen in up to 30% of children. Isolated small bowel disease is much less common in the pediatric population compared to adults. Isolated colonic disease is common in children younger than 8 yr of age and may be indistinguishable from ulcerative colitis. Anatomic location of disease tends to extend over time in children.

Crohn disease tends to have a bimodal age distribution, with the first peak beginning in the teenage years. The incidence of Crohn disease has been increasing. In the United States, the reported incidence of pediatric Crohn disease is 4.56/100,000 and the pediatric prevalence is 43/100,000 children.

Clinical Manifestations

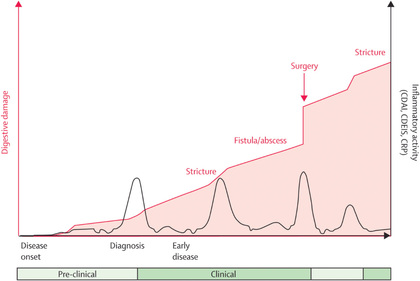

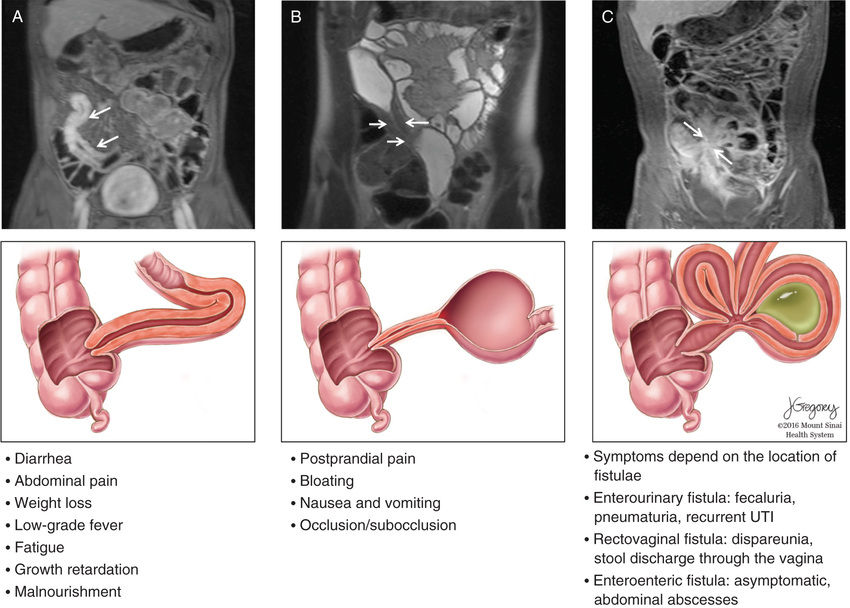

Crohn disease can be characterized as inflammatory, stricturing, or penetrating. Patients with small bowel disease are more likely to have an obstructive pattern (most commonly with right lower quadrant pain) characterized by fibrostenosis, and those with colonic disease are more likely to have symptoms resulting from inflammation (diarrhea, bleeding, cramping). Disease phenotypes often change as duration of disease lengthens (inflammatory becomes structuring and/or penetrating) (Figs. 362.5 and 362.6 ).

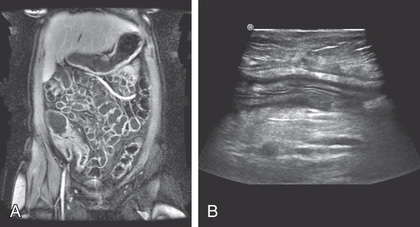

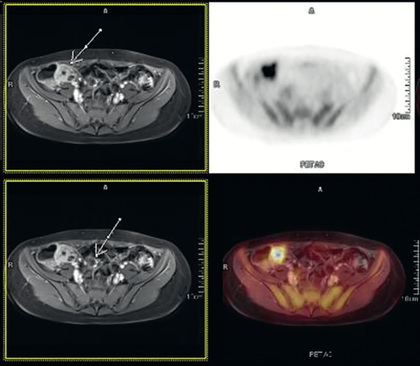

Systemic signs and symptoms are more common in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis. Fever, malaise, and easy fatigability are common. Growth failure with delayed bone maturation and delayed sexual development can precede other symptoms by 1 or 2 yr and is at least twice as likely to occur with Crohn disease as with ulcerative colitis. Children can present with growth failure as the only manifestation of Crohn disease. Decreased height velocity occurs in about 88% of prepubertal patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, and this often precedes GI symptoms. Causes of growth failure include inadequate caloric intake, suboptimal absorption or excessive loss of nutrients, the effects of chronic inflammation on bone metabolism and appetite, and the use of corticosteroids during treatment. Primary or secondary amenorrhea and pubertal delay are common. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, perianal disease is common (tag, fistula, deep fissure, abscess). Gastric or duodenal involvement may be associated with recurrent vomiting and epigastric pain. Partial small bowel obstruction, usually secondary to narrowing of the bowel lumen from inflammation or stricture , can cause symptoms of cramping abdominal pain (especially with meals), borborygmus, and intermittent abdominal distention (Figs. 362.7 and 362.8 ). Stricture should be suspected if the child notes relief of symptoms in association with a sudden sensation of gurgling of intestinal contents through a localized region of the abdomen. Inflammatory obstruction versus fibrotic stricture-induced obstruction may be distinguished by positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (PET/MRI), which will direct specific therapy (Fig. 362.9 ).

Penetrating disease is demonstrated by fistula formation. Enteroenteric or enterocolonic fistulas (between segments of bowel) are often asymptomatic but can contribute to malabsorption if they have high output or result in bacterial overgrowth (Fig. 362.10 ). Enterovesical fistulas (between bowel and urinary bladder) originate from ileum or sigmoid colon and appear as signs of urinary infection, pneumaturia, or fecaluria. Enterovaginal fistulas originate from the rectum, cause feculent vaginal drainage, and are difficult to manage. Enterocutaneous fistulas (between bowel and abdominal skin) often are caused by prior surgical anastomoses with leakage. Intraabdominal abscess may be associated with fever and pain but might have relatively few symptoms. Hepatic or splenic abscess can occur with or without a local fistula. Anorectal abscesses often originate immediately above the anus at the crypts of Morgagni. The patterns of perianal fistulas are complex because of the different tissue planes. Perianal abscess is usually painful, but perianal fistulas tend to produce fewer symptoms than anticipated. Purulent drainage is commonly associated with perianal fistulas. Psoas abscess secondary to intestinal fistula can present as hip pain, decreased hip extension (psoas sign), and fever.

Extraintestinal manifestations occur more commonly with Crohn disease than with ulcerative colitis; those that are especially associated with Crohn disease include oral aphthous ulcers, peripheral arthritis, erythema nodosum, digital clubbing, episcleritis, renal stones (uric acid, oxalate), and gallstones. Any of the extraintestinal disorders described in the section on IBD can occur with Crohn disease (see Table 362.3 ). The peripheral arthritis is nondeforming. The occurrence of extraintestinal manifestations usually correlates with the presence of colitis.

Extensive involvement of small bowel, especially in association with surgical resection, can lead to short bowel syndrome, which is rare in children. Complications of terminal ileal dysfunction or resection include bile acid malabsorption with secondary diarrhea and vitamin B12 malabsorption, with possible resultant deficiency. Chronic steatorrhea can lead to oxaluria with secondary renal stones. Increasing calcium intake can actually decrease the risk of renal stones secondary to ileal inflammation. The risk of cholelithiasis is also increased secondary to bile acid depletion.

A disorder with this diversity of manifestations can have a major impact on an affected child's lifestyle. Fortunately, the majority of children with Crohn disease are able to continue with their normal activities, having to limit activity only during periods of increased symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common diagnoses to be distinguished from Crohn disease are the infectious enteropathies (in the case of Crohn disease: acute terminal ileitis, infectious colitis, enteric parasites, and periappendiceal abscess) (see Tables 362.5 , 362.6 , and 362.8 ). Yersinia can cause many of the radiologic and endoscopic findings in the distal small bowel that are seen in Crohn disease. The symptoms of bacterial dysentery are more likely to be mistaken for ulcerative colitis than for Crohn disease. Celiac disease and Giardia infection have been noted to produce a Crohn-like presentation including diarrhea, weight loss, and protein-losing enteropathy. GI tuberculosis is rare but can mimic Crohn disease. Foreign-body perforation of the bowel (toothpick) can mimic a localized region with Crohn disease. Small bowel lymphoma can mimic Crohn disease but tends to be associated with nodular-filling defects of the bowel without ulceration or narrowing of the lumen. Bowel lymphoma is much less common in children than is Crohn disease. Recurrent functional abdominal pain can mimic the pain of small bowel Crohn disease. Lymphoid nodular hyperplasia of the terminal ileum (a normal finding) may be mistaken for Crohn ileitis. Right lower quadrant pain or mass with fever can be the result of periappendiceal abscess. This entity is occasionally associated with diarrhea as well.

Table 362.8

From Kugathasan S: Diarrhea. In Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy , ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, WB Saunders, p 287.

Growth failure may be the only manifestation of Crohn disease; other disorders such as growth hormone deficiency, gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease), Turner syndrome, or anorexia nervosa must be considered. If arthritis precedes the bowel manifestations, an initial diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis may be made. Refractory anemia may be the presenting feature and may be mistaken for a primary hematologic disorder. Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood can cause inflammatory changes in the bowel as well as perianal disease. Antral narrowing in this disorder may be mistaken for a stricture secondary to Crohn disease. Other immunodeficiencies or autoinflammatory conditions and monogenetic disorders may present with GI symptoms suggestive of IBD, particularly in very early or infant/toddler onset of disease (see Table 362.6 ).

Diagnosis

Crohn disease can manifest as a variety of symptom combinations (see Fig. 362.6 ). At the onset, symptoms may be subtle (growth retardation, abdominal pain alone); this explains why the diagnosis might not be made until 1 or 2 yr after the start of symptoms. The diagnosis of Crohn disease depends on finding typical clinical features of the disorder (history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and endoscopic or radiologic findings), ruling out specific entities that mimic Crohn disease, and demonstrating chronicity. The history can include any combination of abdominal pain (especially right lower quadrant), diarrhea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, growth retardation, and extraintestinal manifestations. Only 25% initially have the triad of diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain. Most do not have diarrhea, and only 25% have GI bleeding.

Children with Crohn disease often appear chronically ill. They commonly have weight loss and growth failure, and they are often malnourished. The earliest sign of growth failure is decreased height velocity, which can be present in up to 88% of prepubertal patients with Crohn disease and typically precedes symptoms. Children with Crohn disease often appear pale, with decreased energy level and poor appetite; the latter finding sometimes results from an association between meals and abdominal pain or diarrhea. There may be abdominal tenderness that is either diffuse or localized to the right lower quadrant. A tender mass or fullness may be palpable in the right lower quadrant. Perianal disease, when present, may be characteristic. Large anal skin tags (1-3 cm diameter) or perianal fistulas with purulent drainage suggest Crohn disease. Digital clubbing, findings of arthritis, and skin manifestations may be present.

A complete blood cell count commonly demonstrates anemia, often with a component of iron deficiency, as well as thrombocytosis. Although the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated, they may be unremarkable. The serum albumin level may be low, indicating small bowel inflammation or protein-losing enteropathy. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are increasingly being used as more sensitive and specific markers of bowel inflammation as compared to serologic parameters, and these are often elevated. Multiple serologic, immune, and genetic markers can also be abnormal, although the best utilization of these remains to be determined.

The small and large bowel and the upper GI tract should be examined by both endoscopic and radiologic studies in the child with suspected Crohn disease. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and ileocolonoscopy should be performed to properly assess the upper GI tract, terminal ileum, and entire colon. Findings on colonoscopy can include patchy, nonspecific inflammatory changes (erythema, friability, loss of vascular pattern), aphthous ulcers, linear ulcers, nodularity, and strictures. Findings on biopsy may be only nonspecific chronic inflammatory changes. Noncaseating granulomas, similar to those of sarcoidosis, are the most characteristic histologic findings, although often they are not present. Transmural inflammation is also characteristic but can be identified only in surgical specimens.

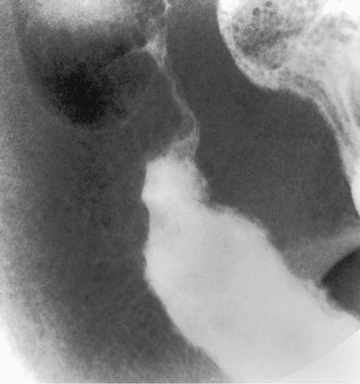

Radiologic studies are necessary to assess the entire small bowel and investigate for evidence of structuring or penetrating disease. A variety of findings may be apparent on radiologic studies. Plain films of the abdomen may be normal or might demonstrate findings of partial small bowel obstruction or thumbprinting of the colon wall. An upper GI contrast study with small bowel follow-through might show aphthous ulceration and thickened, nodular folds as well as narrowing or stricturing of the lumen. Linear ulcers can give a cobblestone appearance to the mucosal surface. Bowel loops are often separated as a result of thickening of bowel wall and mesentery. Other manifestations on radiographic studies that suggest more-severe Crohn disease are fistulas between bowel (enteroenteric or enterocolonic), sinus tracts, and strictures (see Figs. 362.7 , 362.8 , and 362.10 ).

An upper GI contrast examination with small bowel follow-through has typically been the study of choice for imaging of the small bowel, but CT and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography and small bowel ultrasound are increasingly being used. MR and ultrasound have the advantage of not exposing the patient to ionizing radiation. CT and MR enterography can also assess for extraluminal findings such as abscesses and phlegmons. MR of the pelvis is also useful for delineating the extent of perianal involvement. PET/MRI may help define obstructing lesions as either inflammatory or fibrotic (see Fig. 362.9 ).

Video capsule endoscopy is another modality that allows for evaluation of the small bowel. This study can uncover mucosal inflammation or ulceration that might not have been detected by traditional imaging. However, video capsule endoscopy is contraindicated in the presence of stricturing disease, as surgical intervention would be required to remove a video capsule that is unable to pass through the bowel because a stricture. If there is concern for stricturing disease, a patency capsule can be swallowed prior to video capsule endoscopy to assess for passage through the GI tract.

Treatment

Crohn disease cannot be cured by medical or surgical therapy. The aim of treatment is to relieve symptoms and prevent complications of chronic inflammation (anemia, growth failure), prevent relapse, minimize corticosteroid exposure, and, if possible, effect mucosal healing.

Medical

The specific therapeutic modalities used depend on geographic localization of disease, severity of inflammation, age of the patient, and the presence of complications (abscess). Traditionally, a step-up treatment paradigm has been used in the treatment of pediatric Crohn disease, whereby early disease is treated with steroids and less immunosuppressive medications. Escalation of therapy would occur if disease severity increased, the patient was refractory to current medications, or for steroid dependence. A top-down approach has also been espoused, particularly in adults after multiple studies demonstrated superior efficacy. With this approach, patients with moderate to severe Crohn disease are treated initially with stronger, disease-modifying agents, with the goal of achieving mucosal healing, or deep remission, early in the disease course. This is thought to increase the likelihood of long-term remission while decreasing corticosteroid exposure. Improvements in remission and growth have been shown using a top-down approach in pediatrics and this treatment approach is being increasingly used among children. However, the precise role for this approach in pediatrics is still being determined.

5-Aminosalicylates

For mild terminal ileal disease or mild Crohn disease of the colon, an initial trial of mesalamine (50-100 mg/kg/day, maximum 3-4 g) may be attempted. Specific pharmaceutical preparations have been formulated to release the active 5-ASA compound throughout the small bowel, in the ileum and colon, or exclusively in the colon. Rectal preparations are used for distal colonic inflammation.

Antibiotics/Probiotics

Antibiotics such as metronidazole (10-22.5 mg/kg/day) are used for infectious complications and are first-line therapy for perianal disease (although perianal disease usually recurs when antibiotic is discontinued). Additionally, at low doses antibiotics may be effective for treatment of mild to moderate Crohn disease. To date, probiotics have not been shown to be effective in induction or maintenance of remission for pediatric Crohn disease.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are used for acute exacerbations of pediatric Crohn disease because they effectively suppress acute inflammation, rapidly relieving symptoms (prednisone, 1-2 mg/kg/day, maximum 40-60 mg). The goal is to taper dosing as soon as the disease becomes quiescent. Clinicians vary in their tapering schedules, and the disease can flare during this process. There is no role for continuing corticosteroids as maintenance therapy because, in addition to their side effects, tolerance develops, and steroids do not change disease course or promote healing of mucosa. A special controlled ileal-release formulation of budesonide, a corticosteroid with local antiinflammatory activity on the bowel mucosa and high hepatic first-pass metabolism, is also used for mild to moderate ileal or ileocecal disease (adult dose: 9 mg daily). Ileal-release budesonide appears to be more effective than mesalamine in the treatment of active ileocolonic disease but is less effective than prednisone. Although less effective than traditional corticosteroids, budesonide does cause fewer steroid-related side effects.

Immunomodulators

Approximately 70% of patients require escalation of medical therapy within the 1st yr of pediatric Crohn disease diagnosis. Immunomodulators such as azathioprine (2.0-2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6-mercaptopurine (1.0-1.5 mg/kg/day) may be effective in some children who have a poor response to prednisone or who are steroid dependent. Because a beneficial effect of these drugs can be delayed for 3-4 mo after starting therapy, they are not helpful acutely. The early use of these agents can decrease cumulative prednisone dosages over the first 1-2 yr of therapy. Genetic variations in an enzyme system responsible for metabolism of these agents (thiopurine S -methyltransferase) can affect response rates and potential toxicity. Lymphoproliferative disorders have developed from thiopurine use in patients with IBD. Other common toxicities include hepatitis, pancreatitis, increased risk of skin cancer, increased risk of infection, and slightly increased risk of lymphoma.

Methotrexate is another immunomodulator that is effective in the treatment of active Crohn disease and has been shown to improve height velocity in the 1st yr of administration. The advantages of this medication include once-weekly dosing by either subcutaneous or oral route (15 mg/m2 , adult dose 25 mg weekly) and a more-rapid onset of action (6-8 wk) than azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Folic acid is usually administered concomitantly to decrease medication side effects. Administration of ondansetron prior to methotrexate has been shown to diminish the risk of the most common side effect of nausea. The most common toxicity is hepatitis. The immunomodulators are effective for the treatment of perianal fistulas.

Biologic Therapy

Therapy with antibodies directed against mediators of inflammation is used for patients with Crohn disease. Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, is effective for the induction and maintenance of remission and mucosal healing in chronically active moderate to severe Crohn disease, healing of perianal fistulas, steroid sparing, and preventing postoperative recurrence. Pediatric data additionally support improved growth with the administration of this medication. The onset of action of infliximab is quite rapid and it is initially given as 3 infusions over a 6 wk period (0, 2, and 6 wk), followed by maintenance dosing beginning every 8 wk. The durability of response to infliximab is variable and dose escalation (higher dose and/or decreased interval) is often necessary. Measurement of serum trough infliximab level prior to an infusion can help guide dosing decisions. Side effects include infusion reactions, increased incidence of infections (especially reactivation of latent tuberculosis), increased risk of lymphoma, and the development of autoantibodies. The development of antibodies to infliximab is associated with an increased incidence of infusion reactions and decreased durability of response. Regularly scheduled dosing of infliximab, as opposed to episodic dosing on an as-needed basis, is associated with decreased levels of antibodies to infliximab. A purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis should be done before starting infliximab.

Adalimumab, a subcutaneously administered, fully humanized monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, is effective for the treatment of chronically active moderate to severe Crohn disease in adults and children. After a loading dose, this is typically administered once every 2 wk, although dose escalation is sometimes required with this medication. Vedolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits adhesion and migration of leukocytes into the GI tract, is approved for the treatment of Crohn disease in adults. Like infliximab, vedolizumab is initially given as 3 infusions over a 6 wk period followed by maintenance dosing beginning every 8 wk. However, the onset of action for vedolizumab is slower compared to infliximab and adalimumab. Therefore, concomitant therapies may be needed until response is demonstrated. Dose escalation to every 4 wk may be necessary in some patients with loss-of-response but is being further studied. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody against interleukins 12 and 23, was recently approved for treatment of chronically active moderate to severe Crohn disease in adults. A loading dose is given intravenously followed by maintenance dosing administered subcutaneously every 8 wk. New antiselective adhesion molecules and small molecule treatments, such as an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide that targets TGF-β signaling, are currently being tested.

Enteral Nutritional Therapy

Exclusive enteral nutritional therapy, whereby all of a patient's calories are delivered via formula, is an effective primary as well as adjunctive treatment. The enteral nutritional approach is as rapid in onset of response and as effective as the other treatments. Pediatric studies have suggested similar efficacy to prednisone for improvement in clinical symptoms, but enteral nutritional therapy is superior to steroids for actual healing of mucosa. Because affected patients have poor appetite and these formulas are relatively unpalatable, they are often administered via a nasogastric or gastrostomy infusion, usually overnight. The advantages are that it is relatively free of side effects, avoids the problems associated with corticosteroid therapy, and simultaneously addresses the nutritional rehabilitation. Children can participate in normal daytime activities. A major disadvantage of this approach is that patients are not able to eat a regular diet because they are receiving all of their calories from formula. A novel approach where 80–90% of caloric needs are provided by formula, allowing children to have some food intake, has been successful. For children with growth failure, this approach may be ideal, however.

High-calorie oral supplements, although effective, are often not tolerated because of early satiety or exacerbation of symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea). Nonetheless, they should be offered to children whose weight gain is suboptimal even if they are not candidates for exclusive enteral nutritional therapy. The continuous administration of nocturnal nasogastric feedings for chronic malnutrition and growth failure has been effective with a much lower risk of complications than parenteral hyperalimentation.

Surgery

Surgical therapy should be reserved for very specific indications. Recurrence rate after bowel resection is high (>50% by 5 yr); the risk of requiring additional surgery increases with each operation. Potential complications of surgery include development of fistula or stricture, anastomotic leak, postoperative partial small bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions, and short bowel syndrome. Surgery is the treatment of choice for localized disease of small bowel or colon that is unresponsive to medical treatment, bowel perforation, fibrosed stricture with symptomatic partial small bowel obstruction, and intractable bleeding. Intraabdominal or liver abscess sometimes is successfully treated by ultrasonographic or CT-guided catheter drainage and concomitant intravenous antibiotic treatment. Open surgical drainage is necessary if this approach is not successful. Growth retardation was once considered an indication for resection; without other indications, trial of medical and/or nutritional therapy is currently preferred.

Perianal abscess often requires drainage unless it drains spontaneously. In general, perianal fistulas should be managed by a combined medical and surgical approach. Often, the surgeon places a seton through the fistula to keep the tract open and actively draining while medical therapy is administered, to help prevent the formation of a perianal abscess. A severely symptomatic perianal fistula can require fistulotomy, but this procedure should be considered only if the location allows the sphincter to remain undamaged.

The surgical approach for Crohn disease is to remove as limited a length of bowel as possible. There is no evidence that removing bowel up to margins that are free of histologic disease has a better outcome than removing only grossly involved areas. The latter approach reduces the risk of short bowel syndrome. Laparoscopic approach is increasingly being used, with decreased postoperative recovery time. One approach to symptomatic small bowel stricture has been to perform a strictureplasty rather than resection. The surgeon makes a longitudinal incision across the stricture but then closes the incision with sutures in a transverse fashion. This is ideal for short strictures without active disease. The reoperation rate is no higher with this approach than with resection, whereas bowel length is preserved. Postoperative medical therapy with agents such as mesalamine, metronidazole, azathioprine, and, more recently, infliximab, is often given to decrease the likelihood of postoperative recurrence.

Severe perianal disease can be incapacitating and difficult to treat if unresponsive to medical management. Diversion of fecal stream can allow the area to be less active, but on reconnection of the colon, disease activity usually recurs.

Support

Psychosocial issues for the child with Crohn disease include a sense of being different, concerns about body image, difficulty in not participating fully in age-appropriate activities, and family conflict brought on by the added stress of this disease. Social support is an important component of the management of Crohn disease. Parents are often interested in learning about other children with similar problems, but children may be hesitant to participate. Social support and individual psychologic counseling are important in the adjustment to a difficult problem at an age that by itself often has difficult adjustment issues. Patients who are socially “connected” fare better. Ongoing education about the disease is an important aspect of management because children generally fare better if they understand and anticipate problems. The Crohn and Colitis Foundation of America has local chapters throughout the United States and supports several regional 1-wk camps for children with Crohn disease.

Prognosis

Crohn disease is a chronic disorder that is associated with high morbidity but low mortality. Symptoms tend to recur despite treatment and often without apparent explanation. Weight loss and growth failure can usually be improved with treatment and attention to nutritional needs. Up to 15% of patients with early growth retardation secondary to Crohn disease have a permanent decrease in linear growth. Osteopenia is particularly common in those with chronic poor nutrition and frequent exposure to high doses of corticosteroids. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry can help identify patients at risk for developing osteopenia. Steroid-sparing agents, weight bearing exercise, and improved nutrition, including supplementation with vitamin D and calcium, can improve bone mineralization. Some of the extraintestinal manifestations can, in themselves, be major causes of morbidity, including sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and ankylosing spondylitis.

The region of bowel-involved and complications of the inflammatory process tend to increase with time and include bowel strictures, fistulas, perianal disease, and intraabdominal or retroperitoneal abscess. Most patients with Crohn disease eventually require surgery for one of its many complications; the rate of reoperation is high. Surgery is unlikely to be curative and should be avoided except for the specific indications noted previously. An earlier, most aggressive medical treatment approach, with the goal of exacting mucosal healing may improve long-term prognosis, and this is an active area of investigation. The risk of colon cancer in patients with long-standing Crohn colitis approaches that associated with ulcerative colitis, and screening colonoscopy after 8-10 yr of colonic disease is indicated.

Despite these complications, most children with Crohn disease lead active, full lives with intermittent flare-up in symptoms.

Bibliography

Absah I, Stephens M. Adjunctive treatment to antitumor necrosis factor in pediatric patients with refractory Crohn's disease. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2013;25:624–628.

Ananthakrishnan AN. Filgotinib for Crohn's disease—expanding treatment options. Lancet . 2017;389:228–229.

Ardizzone S, Maconi G, Sampietro GM, et al. Azathioprine and mesalamine for prevention of relapse after conservative surgery for crohn disease. Gastroenterology . 2004;127:730–740.

Ashton JJ, Ennis S, Beattie RM. Early-onset paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet . 2017;1:147–158.

Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DI, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat Genet . 2008;40:955–962.

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease. Lancet . 2012;380:1590–1602.

Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet . 2009;374:1617–1624.

Biancheri P, Di Sabatino A, Rovedatti L, et al. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade on mucosal addressin cell-adhesion molecule-1 in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2013;19(2):259–264.

Borelli O, Cordischi L, Cirulli M, et al. Polymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol . 2006;4:744–753.

Catalano OA, Gee MS, Nicolai E, et al. Evaluation of quantitative PET/MR enterography biomarkers for discrimination of inflammatory strictures from fibrotic strictures in crohn disease. Radiology . 2016;278(3):792–800.

Cheifetz AS. Management of active crohn disease. JAMA . 2013;309:2150–2158.

Ciccocioppo R, Corazza GR. Mesenchymal stem cells for fistulizing Crohn's disease. Lancet . 2016;388:1251–1252.

Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn's disease (CALM): a multicenter, randomized, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet . 2017;390:27792788.

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2010;362(15):1383–1394.

D'Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomized trial. Lancet . 2008;371:660–667.

De Felice KM, Katzka DA, Raffals LE. Crohn's disease of the esophagus: clinical features and treatment outcomes in the biologic era. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2005;21(9):2106–2113 [2–15].

DeBoer MD, Denson LA. Delays in puberty, growth, and accrual of bone mineral density in pediatric Crohn's disease: despite temporal changes in disease severity, the need for monitoring remains. J Pediatr . 2013;163:17–22.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23-inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet . 2017;389:1699–1708.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(20):1946–1960.

Gentile NM, Murray JA, Pardi DS. Autoimmune enteropathy: a review and update of clinical management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep . 2012;14:380–385.

Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet . 2010;375:657–662.

Gupta K, Noble A, Kachelries KE, et al. A novel enteral nutrition protocol for the treatment of pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2013;19:1374–1378.

Hanauer SB. Targeting interleukin 23 for Crohn's disease: finding the right drug for the right patient. Lancet . 2017;389:1671–1672.

Hyams J, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab for moderate to severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology . 2012;143:365–374.

Kabi A, Nickerson KP, Homer CR, et al. Digesting the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease: insights from studies of autophagy risk genes. Inflamm Bowel Dis . 2012;18:782–792.

Kanneganti TD. Inflammatory bowel disease and the NLRP3 inflammasome. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(7):694–696.

Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence of geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol . 2007;5:1424–1429.

Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn's disease (REACT): a cluster randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2015;386:1825–1834.

Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Walters TW, et al. Prediction of complicated disease course for children newly diagnosed with Crohn's disease: a multicenter inception cohort study. Lancet . 2017;389:1710–1718.

Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr . 2003;143:525–531.

Laakso S, Valta H, Verkasalo M, et al. Impaired bone health in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study in 80 pediatric patients. Calcif Tissue Int . 2012;91(2):121–130.

Lazzerini M, Martelossi S, Magazzu G, et al. Effect of thalidomide on clinical remission in children and adolescents with refractory crohn disease—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2013;310(20):2164–2173.

Monteleone G, Neurath MF, Ardizzone S, et al. Mongersen, an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide, and Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(12):1104–1113.

Oliva-Hemker M, Huftless S, Al Kazzi ES, et al. Clinical presentation and five-year therapeutic management of very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease in a large north American cohort. J Pediatr . 2015;167:527–532.

Pellino G, Nicolai E, Catalano OA, et al. PET/MR versus PET/CT imaging: impact on the clinical management of small-bowel Crohn's disease. J Crohn Colitis . 2017;10(3):277–285.

Qiu Y, Li MY, Feng T, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy for Crohn's disease. Sten Cell Res Ther . 2017;8:136.

Riguero M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, et al. Infliximab prevents Crohn's disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology . 2009;136:441–450.

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2013;369(8):711–721.

Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Gao LL, et al. Ustekinumab induction and maintenance therapy in refractory Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:1519–1528.

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med . 2004;350:876–885.