Pneumothorax

Glenna B. Winnie, Suraiya K. Haider, Aarthi P. Vemana, Steven V. Lossef

Pneumothorax is the accumulation of extrapulmonary air within the chest, most commonly from leakage of air from within the lung. Air leaks can be primary or secondary and can be spontaneous, traumatic, iatrogenic, or catamenial (Table 439.1 ). Pneumothorax in the neonatal period is also discussed in Chapter 122.1 .

Table 439.1

Causes of Pneumothorax in Children

| SPONTANEOUS |

|

Primary Idiopathic (no underlying lung disease) Spontaneous rupture of subpleural blebs Secondary (underlying lung disease) Congenital lung disease Conditions associated with increased intrathoracic pressure Infection Lung disease |

| TRAUMATIC |

|

Non-iatrogenic Iatrogenic |

Adapted from Noppen M. Spontaneous pneumothorax:epidemiology, pathophysiology and cause. Eur Respir Rev 19:117, 217–219, 2010 (Table 1, 2, p 218).

Etiology and Epidemiology

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without trauma or underlying lung disease. Spontaneous pneumothorax with or without exertion occurs occasionally in teenagers and young adults, most frequently in males who are tall, thin, and thought to have subpleural blebs. Smoking and asthma are also risk factors for developing pneumothorax. Familial cases of spontaneous pneumothorax occur and have been associated with mutations in the folliculin gene (FCLN) . Over 150 unique FCLN mutations have been associated in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (skin fibrofolliculomas, multiple basal lung cysts, renal malignancies) or in patients with familial or recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraces. Individuals with other inherited disorders such as α1 -antitrypsin (see Chapter 421 ) and homocystinuria are also predisposed to pneumothorax. Patients with collagen synthesis defects such as Ehlers-Danlos disease (see Chapter 678 ) and Marfan syndrome (see Chapter 722 ) are at increased risk for the development of pneumothorax.

A pneumothorax arising as a complication of an underlying lung disorder but without trauma is a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Pneumothorax can occur in pneumonia, usually with empyema; it can also be secondary to pulmonary abscess, gangrene, infarct, rupture of a cyst or an emphysematous bleb (in asthma), or foreign bodies in the lung. In infants with staphylococcal pneumonia, the incidence of pneumothorax is relatively high. It can be found in children hospitalized with asthma exacerbations, and usually resolves without treatment. Pneumothorax is a serious complication in cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 432 ). Pneumothorax also occurs in patients with lymphoma or other malignancies, and in graft-versus-host disease with bronchiolitis obliterans.

External chest or abdominal blunt or penetrating trauma can tear a bronchus or abdominal viscus, with leakage of air into the pleural space. Ecstasy (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), crack cocaine, and marijuana abuse are associated with pneumothorax.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax can complicate transthoracic needle aspiration, tracheotomy, subclavian line placement, thoracentesis, or transbronchial biopsy. It may occur during mechanical or noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula therapy, acupuncture, and other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.

Catamenial pneumothorax, an unusual condition that is related to menses, is associated with diaphragmatic defects and pleural blebs.

Pneumothorax can be associated with a serous effusion (hydropneumothorax), a purulent effusion (pyopneumothorax), or blood (hemopneumothorax). Bilateral pneumothorax is rare after the neonatal period but has been reported after lung transplantation and with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and tuberculosis.

Pathogenesis

The tendency of the lung to collapse, or elastic recoil, is balanced in the normal resting state by the inherent tendency of the chest wall to expand outward, creating negative pressure in the intrapleural space. When air enters the pleural space, the lung collapses. Hypoxemia occurs because of alveolar hypoventilation, ventilation–perfusion mismatch, and intrapulmonary shunt. In simple pneumothorax, intrapleural pressure is atmospheric, and the lung collapses up to 30%. In tension pneumothorax , continuing leak causes increasing positive pressure in the pleural space, with further compression of the lung, shift of mediastinal structures toward the contralateral side, and decreases in venous return and cardiac output causing hemodynamic instability.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of pneumothorax is usually abrupt, and the severity of symptoms depends on the extent of the lung collapse and on the amount of preexisting lung disease. Pneumothorax may cause dyspnea, chest pain, and cyanosis. When it occurs in infancy, symptoms and physical signs may be difficult to recognize. Moderate pneumothorax may cause little displacement of the intrathoracic organs and few or no symptoms. The severity of pain usually does not directly reflect the extent of the collapse.

Usually, there is respiratory distress, with retractions, markedly decreased breath sounds, and a tympanitic percussion note over the involved hemithorax. The larynx, trachea, and heart may be shifted toward the unaffected side. When fluid is present, there is usually a sharply limited area of tympany above a level of flatness to percussion. The presence of bronchial breath sounds or, when fluid is present in the pleural cavity, of gurgling sounds synchronous with respirations suggests an open fistula connecting with air-containing tissues.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

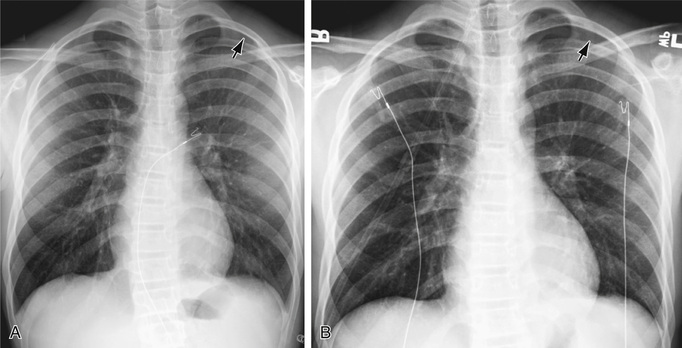

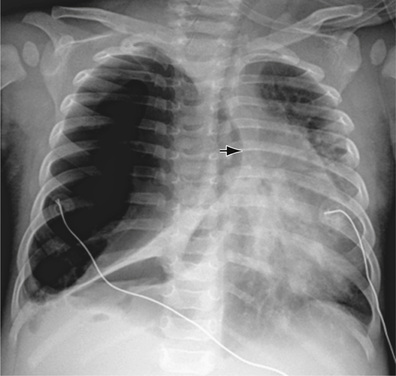

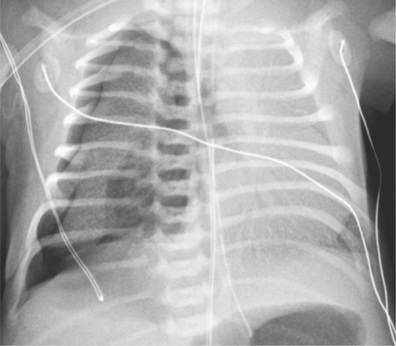

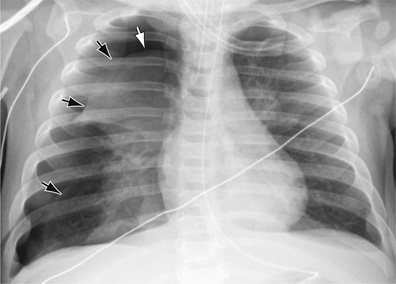

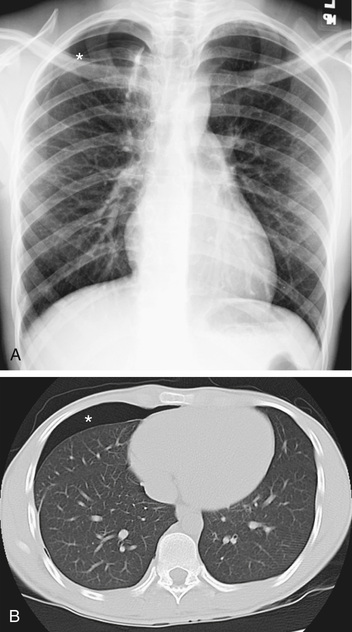

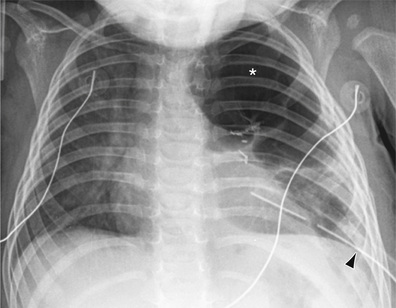

The diagnosis of pneumothorax is usually established by radiographic examination (Figs. 439.1 to 439.6 ). The amount of air outside the lung varies with time. A radiograph that is taken early shows less lung collapse than one taken later if the leak continues. Expiratory views accentuate the contrast between lung markings and the clear area of the pneumothorax (see Fig. 439.1 ). Variations exist in the measurement techniques defining the size of a pneumothorax. A large pneumothorax is measured by The American College of Chest Physicians as ≥3 cm from the lung apex to the thoracic cupola, and by the British Thoracic Society as ≥2 cm from the lung margin to the chest wall at the level of the hilum.

It may be difficult to determine whether a pneumothorax is under tension. Tension pneumothorax is present when there is a shift of mediastinal structures away from the side of the air leak. A shift may be absent in situations in which the other hemithorax resists the shift, such as in the case of bilateral pneumothorax. On occasion, the diagnosis of tension pneumothorax is made only on the basis of evidence of circulatory compromise or on hearing a “hiss” of rapid exit of air under tension with the insertion of the thoracostomy tube. When the lungs are both stiff, such as in cystic fibrosis or respiratory distress syndrome, the unaffected lung may not collapse easily, and shift may not occur (see Fig. 439.3 ).

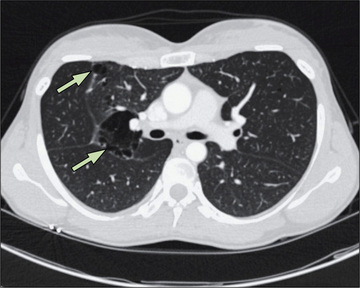

Pneumothorax must be differentiated from localized or generalized emphysema, an extensive emphysematous bleb, large pulmonary cavities or other cystic formations, diaphragmatic hernia, compensatory overexpansion with contralateral atelectasis, and gaseous distention of the stomach. In most cases, chest radiography or CT differentiates among these possibilities. In addition, CT may identify underlying pathology such as blebs (Fig. 439.7 ). Further evaluation to determine if a diaphragmatic hernia is present should include a barium swallow with a small amount of barium to demonstrate that it is not free air but is a portion of the gastrointestinal tract that is in the thoracic cavity (Chapter 122.10 ). Ultrasound can also be used to establish the diagnosis.

Treatment

Therapy varies with the extent of the collapse and the nature and severity of the underlying disease. A small or even moderate-sized pneumothorax in an otherwise normal child may resolve without specific treatment, usually within 1 wk. A small pneumothorax complicating asthma may also resolve spontaneously. Administering 100% oxygen may hasten resolution, but patients with chronic hypoxemia should be monitored closely during administration of supplemental oxygen. Pleural pain deserves analgesic treatment. Needle aspiration into the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line may be required on an emergency basis for tension pneumothorax and is as effective as tube thoracostomy in the emergency room management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. If the pneumothorax is recurrent, secondary, or under tension, or there is more than a small collapse, chest tube drainage may be necessary. Pneumothorax-complicating cystic fibrosis frequently recurs, and definitive treatment may be justified with the first episode. Similarly, if pneumothorax complicating malignancy does not improve rapidly with observation, chemical pleurodesis or surgical thoracotomy is often necessary. In cases with severe air leak or bronchopleural fistula, occlusion with an endobronchial balloon has been successful.

Closed thoracotomy (simple insertion of a chest tube) and drainage of the trapped air through a catheter, the external opening of which is kept in a dependent position under water, is adequate to reexpand the lung in most patients; pigtail catheters are frequently used. In the case of recurrent pneumothorax, a sclerosing procedure may be indicated to induce the formation of strong adhesions between the lung and chest wall with the introduction of talc, doxycycline, or iodopovidone into the pleural space (chemical pleurodesis). Open thoracotomy through a limited incision, with plication of blebs, closure of fistula, stripping of the pleura (usually in the apical lung, where the surgeon has direct vision), and basilar pleural abrasion is also an effective treatment for recurrent pneumothorax. Stripping and abrading the pleura leaves raw, inflamed surfaces that heal with sealing adhesions. Postoperative pain is comparable to that with chemical pleurodesis, but the chest tube can usually be removed in 24-48 hr, compared with the usual 72 hr minimum for closed thoracotomy and pleurodesis. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is a preferred therapy for blebectomy, pleural stripping, pleural brushing, and instillation of sclerosing agents, with less morbidity than occurs with traditional open thoracotomy. There is risk of recurrence after VATS in the pediatric population, although this is often not related to surgical failure, but rather associated with the formation of new bullae.

Pleural adhesions help prevent recurrent pneumothorax, but they also make subsequent thoracic surgery difficult. When lung transplantation may be a future consideration (e.g., in cystic fibrosis), steps should be taken to avoid, if at all possible, chemical or mechanical pleurodesis. It should also be kept in mind that the longer a chest tube is in place, the greater the chance of pulmonary deterioration, particularly in a patient with cystic fibrosis, in whom strong coughing, deep breathing, and postural drainage are important. These are all difficult to accomplish with a chest tube in place.